Abstract

The folding of naturally occurring, single-domain proteins is usually well described as a simple, single-exponential process lacking significant trapped states. Here we further explore the hypothesis that the smooth energy landscape this implies, and the rapid kinetics it engenders, arises due to the extraordinary thermodynamic cooperativity of protein folding. Studying Miyazawa-Jernigan lattice polymers, we find that, even under conditions where the folding energy landscape is relatively optimized (designed sequences folding at their temperature of maximum folding rate), the folding of protein-like heteropolymers is accelerated when their thermodynamic cooperativity is enhanced by enhancing the nonadditivity of their energy potentials. At lower temperatures, where kinetic traps presumably play a more significant role in defining folding rates, we observe still greater cooperativity-induced acceleration. Consistent with these observations, we find that the folding kinetics of our computational models more closely approximates single-exponential behavior as their cooperativity approaches optimal levels. These observations suggest that the rapid folding of naturally occurring proteins is, in part, a consequence of their remarkably cooperative folding.

Keywords: Monte Carlo simulation, optimal folding temperature, native topology, contact order, misfolded states, two-state

Diffusive processes, such as protein folding, progress more rapidly across a smooth energy landscape than on rough landscapes dominated by myriads of energetic barriers (Bryngelson and Wolynes 1989; Bryngelson et al. 1995). Exhaustive lattice and off-lattice heteropolymer simulations support this simple argument; rapid folding is observed only among those relatively rare sequences that lack well-populated, trapped intermediates (Mirny et al. 1996; Chan and Dill 1997, 1998; Cieplak et al. 1998). Similarly supporting this argument, the rapid folding of naturally occurring, single-domain proteins is almost always associated with energy landscapes that are smooth relative to kBT, as indicated by the observation of simple, single-exponential kinetics even at the lowest temperatures that can be investigated experimentally (Gillespie and Plaxco 2000, 2004).

While the relationship between smooth energy landscapes and rapid folding is well established (Bryngelson et al. 1995; Mirny et al. 1996; Chan and Dill 1997, 1998; Cieplak et al. 1998), the perhaps more subtle question of the molecular origins of this smoothness has seen relatively less attention. One of the few attempts to address this issue directly is the work of Shakhnovich and coworkers, who have noted that the landscapes of the vast majority of lattice polymer sequences are very rough and that smooth lattice polymer landscapes are comparatively uncommon (Shakhnovich et al. 1991; Sali et al. 1994; Govindarajan and Goldstein 1995; Buchler and Goldstein 2000; Miller et al. 2002). Based on this observation, they speculated that polypeptides exhibiting smooth landscapes are similarly uncommon and that the rapid folding of naturally occurring proteins arises as a consequence of evolutionary selections aimed at ensuring that this critical property is achieved (e.g., Abkevich et al. 1996; Gutin et al. 1998a; Mirny et al. 1998). Unfortunately, however, experimental studies have not supported this proposal; the folding of de novo designed proteins—proteins produced without any regard to the roughness of their energy landscapes—is generally rapid (Gillespie et al. 2003; Zhu et al. 2003; Kuhlman and Baker 2004; Scalley-Kim and Baker 2004), suggesting that smooth landscapes are a relatively common property of thermodynamically foldable polypeptides (Gillespie et al. 2003; Gillespie and Plaxco 2004). Thus the ultimate origin of the smooth folding energy landscapes observed for naturally occurring proteins remains unclear.

It has been speculated that the discrepancy between the rapid, trap-free folding observed for most small proteins and the generally slow, trap-dominated folding of lattice and off-lattice models (Jewett et al. 2003) may arise because, in contrast to the folding of most computational models, protein folding is thermodynamically cooperative (Kaya and Chan 2003a,b; Chan et al. 2004; Kaya et al. 2005). Thermodynamic cooperativity, usually identified by the calorimetric criterion of Privalov (see, e.g., Makhatadze and Privalov 1995), is defined as a bimodal conformational population peaked around the native and unfolded state enthalpies and practically zero at intermediate enthalpies. The word “cooperativity” is used to describe this effect because it is widely thought to arise from nonadditive (i.e., cooperative) interactions akin to those first proposed as an explanation of the cooperative oxygen binding of hemoglobin (Wyman and Allen 1951). The speculation that a similar cooperativity (arising from similarly nonadditive interactions) might account for the smooth landscapes almost universally observed for the folding of small proteins is based on the hypothesis that such cooperativity will accelerate folding more by destabilizing misfolded, trapped states than it decelerates folding by destabilizing productive intermediates (Eastwood and Wolynes 2001; Jewett et al. 2003).

It is not yet possible to modulate the thermodynamic cooperativity of proteins in the laboratory, and thus it is not yet possible to explore the relationship between cooperativity and folding rates in vitro. It is possible, however, to modulate the cooperativity of computational protein models, and thus simulation experiments provide a useful means of testing the hypothesized link. Despite extensive simulation-based studies of the role of thermodynamic cooperativity in generating linear chevron behavior, topology-dependent rates, and other signatures of two-state folding kinetics, however, the extent to which cooperativity acts to accelerate or decelerate folding has not been explicitly investigated in the prior literature (Fan et al. 2001; Shimizu and Chan 2002; Jewett et al. 2003; Kaya and Chan 2003a,b,c; Cieplack 2004). Here we explore this question via simulations of protein-like Miyazawa-Jernigan lattice polymers to which increasing degrees of cooperativity have been introduced.

Results

Test systems

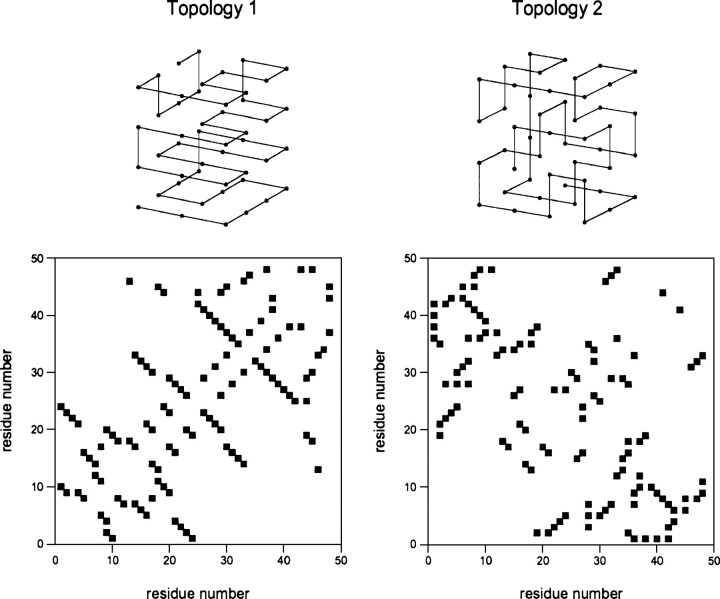

We have explored the folding behavior of 48-residue lattice polymer sequences encoding two topologically distinct native structures. The two structures, named topologies “1” and “2,” exhibit relative contact orders (Plaxco et al. 1998a) of 13% and 26%, respectively, placing them among the least and most “complex” topologies that a maximally compact, 48-monomer structure can adopt (Fig. ▶; Table ▶). Using the design algorithm of Shakhnovich and Gutin (1993), we obtained three rapidly folding sequences encoding each of these distinct topologies. The sequences were designed to adopt the target topologies using the Miyazawa-Jernigan (MJ) energy parameterization

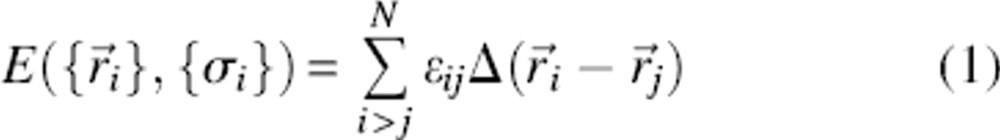

|

where  is the set of bead coordinates that define a conformation, {σ} represents an amino acid sequence, and σi stands for the chemical identity of bead i. The contact function

is the set of bead coordinates that define a conformation, {σ} represents an amino acid sequence, and σi stands for the chemical identity of bead i. The contact function  is 1 if beads i and j form a contact (that is not a covalent linkage) and is otherwise 0. The energy parameters ɛij are taken from the 20 × 20 MJ matrix, derived from the distribution of contacts of native proteins (Miyazawa and Jernigan 1985). In order to minimize the possibility of energy-related kinetic effects, sequences were selected that exhibit similar native state energies, Enat (Table ▶).

is 1 if beads i and j form a contact (that is not a covalent linkage) and is otherwise 0. The energy parameters ɛij are taken from the 20 × 20 MJ matrix, derived from the distribution of contacts of native proteins (Miyazawa and Jernigan 1985). In order to minimize the possibility of energy-related kinetic effects, sequences were selected that exhibit similar native state energies, Enat (Table ▶).

Figure 1.

In this study we have used sequences folding into two topologies (top, numbered “1” and “2”), which are among the least and most complex topologies attainable for a maximally compact 48-residue lattice polymer. (Bottom) The bands perpendicular to the main diagonal in the contact maps (Saitoh et al. 1993), indicating contacts between one amino acid and its four successors, represent the structural equivalent of α-helices. β-sheets are represented as thick bands parallel or antiparallel to the diagonal.

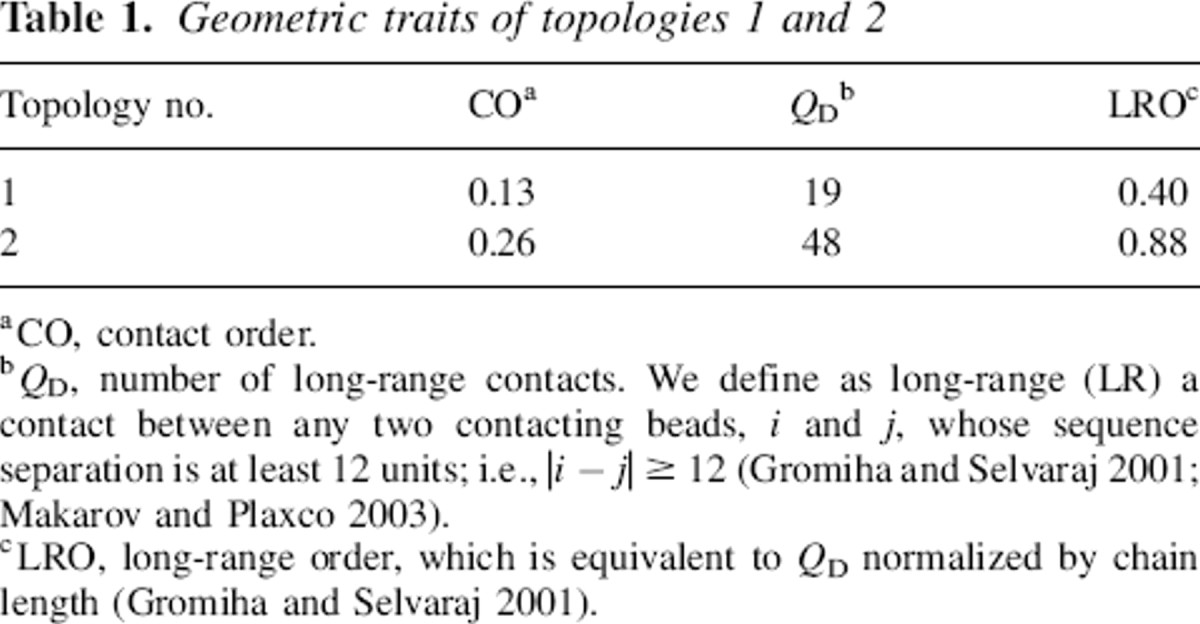

Table 1.

Geometric traits of topologies 1 and 2

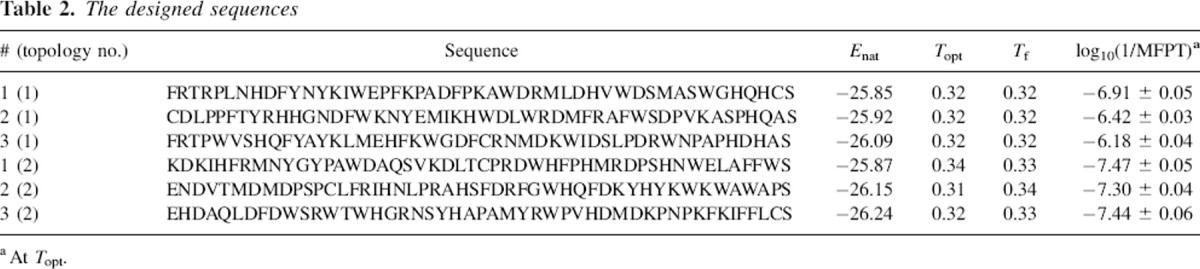

Table 2.

The designed sequences

Enhancing cooperativity

While it is clear that a remarkable feature like thermodynamic cooperativity demands highly unusual energetics, the nature of the interactions underlying the thermodynamic cooperativity of protein folding has not yet been determined (Takada et al. 1999; Kaya and Chan 2000; Fernandez et al. 2002; Shimizu and Chan 2002; Kaya et al. 2005). It is thought, however, that the thermodynamic cooperativity of protein folding arises due to multibody effects leading to nonadditive interactions (i.e., in which the formation of one “bond” makes the formation of subsequent “bonds” more favorable) (Wyman and Allen 1951), a hypothesis that is supported by extensive simulation studies (Eastwood and Wolynes 2001; Fernandez et al. 2002; Kaya and Chan 2003c; Ejtehadi et al. 2004). In order to capture the nonadditivity that presumably underlies thermodynamic cooperativity, we have used a modified version of the MJ potential that entails many-body, non-pairwise interactions in the form of a nonlinear relationship between the energy of a conformation, E′, and the fraction of native contacts, Q, it forms:

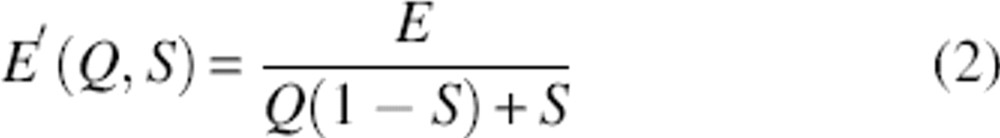

|

where S is a parameter measuring the magnitude of the induced cooperativity and E is given by Equation 1. Of note, Q is the fraction of native contacts; when we use a similar function that counts the total number of contacts, we find that MJ polymers are not thermodynamically stable if S rises even trivially above unity (data not shown). Note too that when S = 1, we recover Equation 1 and the traditional, noncooperative MJ potential. As S increases, however, Equation 2 promotes a steeper decrease of the protein's energy with an increasing number of native contacts when folding nears completion. It does so by penalizing the energy of conformations in which only a small fraction of the total set of native contacts is formed (Q < ∼0.7) (data not shown) and by “repaying” that penalty after that threshold is crossed.

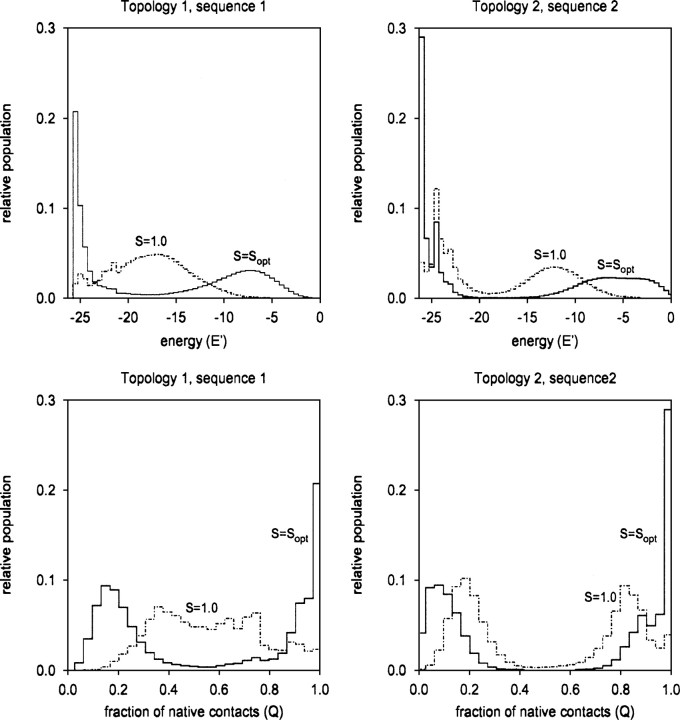

As expected, when S is increased as per Equation 2, the thermodynamic cooperativity of our model systems is significantly enhanced; both the enthalpy distribution and conformational distribution of our model polymers become strongly biomodal (see, e.g., Makhatadze and Privalov 1995) as S is increased from to Sopt (Fig. ▶).

Figure 2.

Enhancing the nonadditivity (i.e., cooperativity; see Wyman and Allen 1951) of the MJ energy potential enhances the thermodynamic cooperativity (Makhatadze and Privalov 1995) of MJ lattice polymer folding. As illustrated here using two representative sequences at their folding transition temperatures, Tf, the energy distributions (top row) and conformational distributions (bottom row) of our model polymers become more strongly biomodal (i.e., more thermodynamically cooperative; see, e.g., Makhatadze and Privalov 1995) as S is increased from 1 to Sopt. In particular, the population of fully native molecules (bottom row, Q = 1.0) is enhanced significantly at higher values of S.

The kinetic consequences of cooperativity at the optimal folding temperature

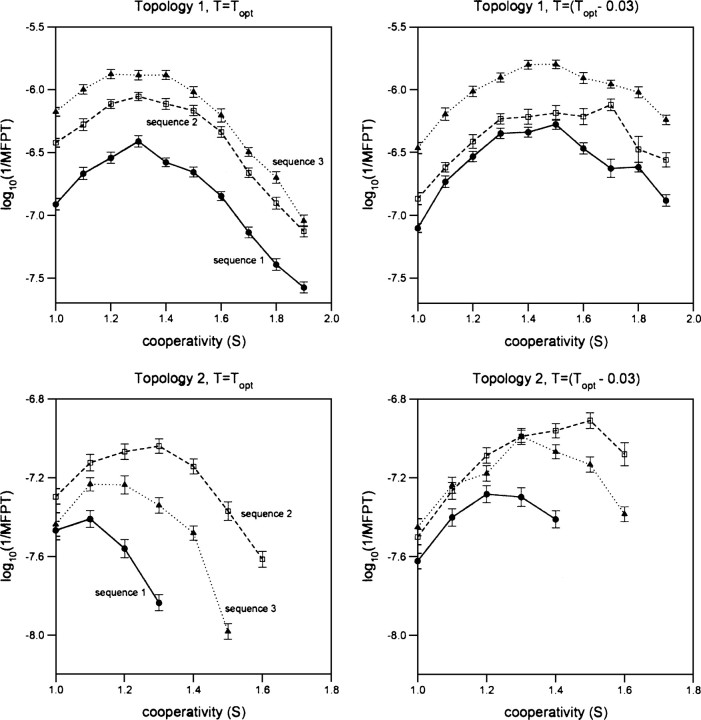

In order to address the extent to which enhanced cooperativity enhances folding rates, we initially performed simulations at Topt, the temperature at which the folding rate of each sequence reaches its maximum value in the absence of added cooperativity. Under these conditions, we find that folding invariably accelerates as cooperativity, S, increases toward its optimal level, Sopt: At their Sopt levels, the folding rates of all six of the sequences we have characterized increase by 1.14- to 3.2-fold relative to the rates observed at S = 1 (Fig. ▶, left). Above Sopt, folding rates decrease, presumably because further increases in cooperativity significantly destabilize the folding transition state.

Figure 3.

The folding of MJ lattice polymers is accelerated when the cooperativity of the MJ energy potential is enhanced. This effect holds for all six sequences we have investigated (adopting both low [top row] and high [bottom row] contact order structures). And while this acceleration is readily apparent even at the temperature of optimal folding (Topt [left column]), it is significantly more pronounced at lower temperatures (T = Topt − 0.03 [right column]), where kinetic traps might be expected to play a more significant role in defining kinetics. Above some optimal level of cooperativity (Sopt), however, folding decelerates with increasing cooperativity. This presumably occurs because further increases in S destabilize native elements in the folding transition state, slowing folding more than the destabilization of trapped states accelerates it.

While the folding time of every test system we have investigated exhibits a similar functional dependence on S, we observe quantitatively different behavior among differing structures and sequences. For example, under these conditions Sopt ranges from 1.2 to 1.3 for the three sequences that fold into topology 1 and the associated rate increases (over the noncooperative, S = 1 benchmark) range from 2.0- to 3.2-fold. In contrast, over a similar range of Sopt, we observe only 1.14- to 1.8-fold accelerations for sequences folding into the more complex topology 2.

The kinetic consequences of cooperativity at lower temperatures

If cooperativity accelerates folding by smoothing the energy landscape, it might be expected to have a larger effect at temperatures below Topt, where landscape roughness plays an increasingly important role in defining folding kinetics (Gutin et al. 1996, 1998a) (under these conditions, there is a higher probability for the chain to get trapped in metastable states). This is perhaps all the more true for sequences that, like those we have used, were designed using an algorithm that ensures that their energy landscapes are relatively smooth (Shakhnovich and Gutin 1993). Consistent with this expectation, we find that the effects of induced cooperativity are indeed much more striking at temperatures below Topt: At T = (Topt − 0.03), we observe up to sixfold increases in the folding rate (Fig. ▶, right). The cooperativity-induced increase in folding rates is, in fact, so great at T = (Topt − 0.03) that under these conditions (at S = Sopt) all six sequences fold more rapidly than they do at Topt (for any S). This presumably occurs because Topt represents a compromise between the driving force behind folding (native state stability), which increases as T decreases, and the kinetic consequences of trapped states, which tend to slow folding when T is reduced. Because of this, lowering the temperature below Topt and raising S to Sopt may accelerate folding by increasing the driving force (Shakhnovich 1994; Gutin et al. 1996, 1998b) without concomitantly stabilizing trapped states that would otherwise slow the process. Perhaps consistent with this argument, it has previously been noted that rapidly folding lattice polymers tend to be those associated with a large gap between the energy of the native state and that of all other maximally compact states (Sali et al. 1994), an effect that might also arise due to a relationship between folding kinetics and thermodynamic cooperativity (Chan et al. 2004). To date, however, it has not yet been shown whether such an energy gap leads to thermodynamic cooperativity.

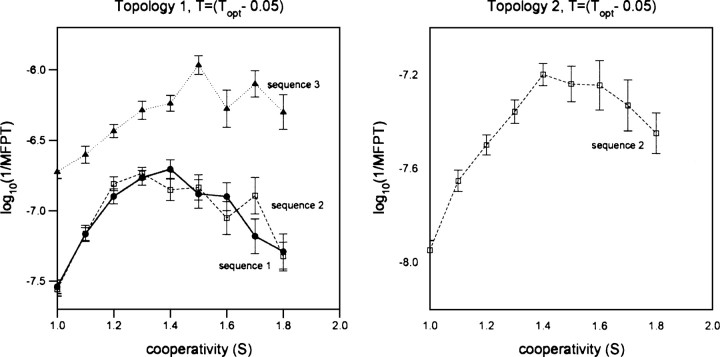

At the still lower temperature of 0.05 energy units below Topt (which corresponds to an ∼16°C temperature drop for a protein with a Topt of ∼40°C) (see, e.g., Plaxco et al. 1998b), folding is significantly slowed, and thus the exhaustive simulation of all six of our test sequences becomes difficult (particularly for sequences folding to the more complex topology 2). Nevertheless, we have investigated all three topology 1 sequences and a representative topology 2 sequence (sequence 2) under these conditions and find that the cooperativity-induced acceleration continues to increase as the temperature is reduced. For example, at this much lower temperature, the three sequences encoding topology 1 fold 5.7–6.9 times more rapidly at Sopt than at S = 1 (Fig. ▶, left). These accelerations are more than twice those observed at Topt and 40%–200% greater than those observed at T = (Topt − 0.03). Similarly, the folding of the sequence adopting the more complex topology 2 increases 4.4-fold at this temperature (Fig. ▶, right), which is 1.8 times the acceleration observed at Topt and 28% greater than that observed at T = (Topt − 0.03). These accelerations are so significant that, even at this very low temperature (which, if for no other reason, should slow folding due to the increase in the barrier height relative to kBT), the folding of the cooperativity-optimized heteropolymers is significantly faster than that observed at Topt in the absence of added cooperativity. We note, however, that although it is typical of this class of lattice models (see, e.g., Faísca and Ball 2002b; Faísca et al. 2005), the dispersion of folding times we observe is smaller than that observed for single-domain proteins (which span a range of 6 orders of magnitude). The chains we have investigated, however, are homogeneous in both length and stability, which perhaps accounts for the relatively limited dispersion in their folding rates.

Figure 4.

At the still lower temperature of T = Topt − 0.05 (corresponding to an ∼16°C temperature drop for a protein with a Topt of ∼40°C—e.g., the similarly sized fynSH3 domain [Plaxco et al. 1998b]), the accelerating effects of enhanced cooperativity are even more pronounced. Under these conditions, the folding rate of one of the sequences encoding topology 1 (left) increases by 5.7- to 6.9-fold as S increases from unity to Sopt. This is more than twice the maximum enhancement observed at Topt and 2%–40% greater than the enhancement observed at T = (Topt − 0.03). For a single sequence adopting the more complex topology 2 (right), we observe a 4.4-fold acceleration at this lower temperature, which is 80% greater than that observed at Topt and 28% greater than that observed at T = (Topt − 0.03).

Cooperativity may enhance folding rates by smoothing the energy landscape

If thermodynamic cooperativity accelerates folding by reducing the stability of trapped states (i.e., smoothing the energy landscape), it might be expected to push kinetics from heterogeneous, nonexponential behavior toward simpler, single-exponential behavior (Bryngelson and Wolynes 1987; Onuchic et al. 1997; Nymeyer et al. 1998; Socci et al. 1998). Consistent with this, Chan and Kaya (Kaya and Chan 2003b) have shown that significant thermodynamic cooperativity must be built into Gō-type lattice polymers in order to recover the linear chevron behavior observed for real proteins. Using two sequences (adopting topologies 1 and 2, respectively), we have investigated this question in more detail (Fig. ▶). We find that, while the folding of these sequences is generally rather well approximated as single exponential (because they were designed to exhibit smooth energy landscapes), without exception the kinetics of our models nevertheless move closer to single-exponential behavior as S increases to its optimal value. For example, in the absence of added cooperativity, we observe correlation coefficients (for the proportional relationship between log(fraction unfolded) and the number of MC steps) ranging from R2 = 0.950–0.976. At Sopt, in contrast, these correlation coefficients invariably increase, ranging from 0.988 to 0.998. Thus, modest levels of added cooperativity appear to invariably improve the single-exponential behavior of even well-designed sequences, suggesting that the added cooperativity is accelerating folding by smoothing the folding energy landscape.

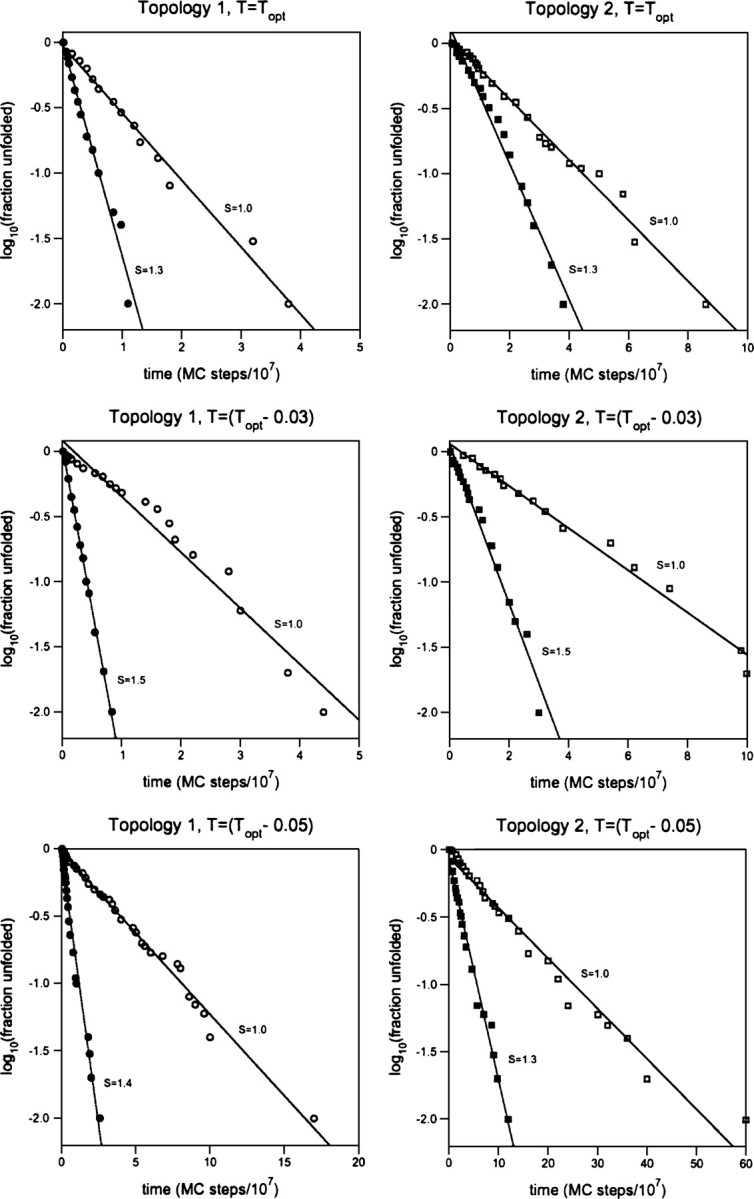

Figure 5.

As the cooperativity increases to its optimal value (Sopt), the folding of MJ lattice polymers more closely approximates a single-exponential relaxation. Shown are the results for two representative sequences (sequence 1 of topology 1 and sequence 2 of topology 2) over a range of temperatures. While the folding of these sequences is generally well approximated as single exponential (because they were designed to fold efficiently), a distinct improvement in the single-exponential behavior of folding kinetics is nevertheless observed (from R2 = 0.950–0.976 to R2 > 0.988) when S reaches Sopt.

Cooperativity may enhance the topology dependence of folding rates

We (Jewett et al. 2003) and others (e.g., Kaya and Chan 2003b; Ejtehadi et al. 2004) have previously noted that modification of the Gō potential to enhance its cooperativity enhances the extent to which Gō polymer folding rates correlate with measures of native state topology. Given that we have investigated only two topologies in this study (albeit they are among the most and least topologically complex of the maximally compact 48-mers), we cannot similarly establish whether increasing cooperativity also enhances the topology dependence of MJ polymer folding rates. Nevertheless, our results are consistent with this speculation: Whereas, at Topt, the three sequences that adopt the more complex (higher CO) topology 2 structure fold, on average, 6.2 times more slowly than those adopting to topology 1, this discrepancy almost doubles to 11.9-fold when S rises to Sopt (Fig. ▶). Whether this effect truly reflects a cooperativity-induced enhancement of the already significant topology-dependence of MJ polymer folding rates (Faísca and Ball 2002b), however, will require the simulation of significantly more topologies than were sampled here.

Discussion

It is known that the folding of Gō polymers, which are characterized by a native-centric energy potential and thus exhibit very smooth energy landscapes, slows as their cooperativity is increased (Jewett et al. 2003; Kaya and Chan 2003b). Such increase in the folding time results from the fact that an increase in cooperativity leads, in such modified Gō-type models, to a destabilization of the transition state relative to the original Gō model, which, by considering only native interactions, is explicitly energetically biased toward the native state. Here we have shown that, in contrast, the folding rates of energetically more complex—and thus perhaps more realistic—MJ models, where native as well as non-native interactions contribute to protein energetics, are increased when their thermodynamic cooperativity is increased and that this effect is enhanced as the temperature drops and landscape roughness plays a larger role in defining kinetics. The observed acceleration presumably arises because modest cooperativity increases folding rates more by destabilizing misfolded, trapped states than it decelerates the process by destabilizing the folding transition state (Eastwood and Wolynes 2001). In support of this claim, the folding kinetics of all six of the sequences we have investigated approach single-exponential behavior more closely as their cooperativity is increased and, as Chan and coworkers have noted (Kaya and Chan 2003b), increases in thermodynamic cooperativity tend to enhance linear chevron behavior.

While our rescaling of the energy leads to a smoother energy landscape, we should note that this does not necessarily imply that the potential we have used becomes more Gō-like as S is increased. Gō and Gō-like models exhibit smooth energy landscapes because they are native-centric; i.e., they neglect the effect of non-native interactions and only consider the contribution of native interactions to the protein's energy. The cooperativity term we have introduced, in contrast, enhances the stability of native-like conformations only when folding is near completion (i.e., for Q > 0.7). Moreover, this effect is mild at the modest levels of cooperativity used here (S < 1.5). For smaller values of Q, our rescaling procedure destabilizes the energy of any conformation with a certain fraction Q of native contacts irrespective of whether that conformation is en route to folding or not. This means that the stability of kinetic traps is not necessarily and selectively reduced relative to that of native-like conformations. Indeed, would this be the case, and contrary to finding an optimal value for S, one would expect to observe a monatonic increase in folding rate with increasing S. The lack of such a relationship implies that the mechanism by which landscape smoothness is achieved in our model differs from the mechanisms underlying the smoothness of Gō models and that, in turn, the observed accelerations are not a trivial outcome of the manner in which cooperativity has been encoded.

The extent to which cooperativity accelerates folding appears to depend on both sequence-specific and topological effects. Indeed, it appears that increasing cooperativity may increase the spread in folding rates between simple and more complex topologies (Jewett et al. 2003; Kaya and Chan 2003b; Ejtehadi et al. 2004; Kaya et al. 2005) in a manner reminiscent of the topology dependence of protein folding rates (Plaxco et al. 1998a). This topology dependence presumably arises because, while the added cooperativity destabilizes energetically trapped, misfolded states (i.e., reduces so-called “energetic frustration”), it does not affect the entropic barriers that arise from the polymer properties of the chain, such as connectivity (Makarov and Plaxco 2003) and excluded volume effects, and quirks of the native topology, such as lack of symmetry (Nelson et al. 1997) (together sometimes termed “topological frustration;” e.g., Shea et al. 1999). Such a linkage between folding rates, topology, and cooperativity is consistent with the topomer search model (Makarov and Plaxco 2003), which postulates that two-state folding kinetics are defined by the diffusive search for unfolded conformations sharing the native topology (i.e., are in the “native topomer”). If folding is thermodynamically cooperative, only the native topomer can form sufficient native-like interactions to ensure productive folding, and thus the entropic cost of finding the native topomer will dominate relative folding rates. Similarly, while lattice polymers cannot fold via a strictly topomer-search process (a coarse lattice polymer cannot be in the native topology without actually being in the native state), the simulations described here illustrate the more general observation that, as cooperativity is increased, global properties such as native-state topology will play an increasingly important role in defining the folding barrier (Plotkin et al. 1997; Eastwood and Wolynes 2001; Jewett et al. 2003).

Irrespective of the origins of the effect, previous studies have demonstrated that increasing thermodynamic cooperativity significantly enhances the topology dependence of lattice polymer folding rates (Jewett et al. 2003; Kaya and Chan 2003b; Ejtehadi et al. 2004). Here we have shown that the addition of cooperativity also accelerates the folding of energetically complex lattice polymers and enhances the single-exponential nature of their kinetics. Taken together, these observations suggest that the observed topological dependence of two-state protein folding rates may be a consequence of the cooperativity necessary to ensure the smooth energy landscapes upon which rapid, single-exponential kinetics can occur.

Materials and methods

The lattice polymer model

We consider a simple three-dimensional lattice model of a protein molecule with chain length L = 48. Individual amino acids are represented in this model by beads of uniform size occupying lattice vertices. These monomer units are connected into a polypeptide chain using bonds of uniform (unitary) length corresponding to the lattice spacing.

In order to mimic folding to the native state, we use a standard Monte Carlo (MC) algorithm together with the kink-jump move set (see, e.g., Landau and Binder 2000) and with the energy defined as in Equation 2. Accordingly, random local displacements of one or two beads are repeatedly accepted or rejected in accordance with the standard Metropolis rule (Metropolis et al. 1953). All MC simulations were started from randomly generated unfolded conformations, and their folding dynamics were traced by following the evolution of the fraction of native contacts, Q = n/N, where N is the total number of native contacts and n is the number of native contacts formed at a given MC step. Each simulation was run until the polymer reached the native fold, i.e., when Q = 1. The number of MC steps required to fold to the native state was defined as the first passage time, and the folding time was computed as the mean first passage time (MFPT) of 100 simulations.

Structure selection and sequence design

We selected two model topologies from a pool of ∼500 maximally compact conformations (MCC) found using simulations of homopolymer relaxation. The latter are MC simulations where a polymeric chain composed by beads of the same chemical species is launched, at temperature T = 0.7, from a randomly generated conformation and relaxes to the minimum energy conformation. For self-attractive homopolymers of length L = 48 on a three-dimensional cubic lattice, the most stable conformation is a MCC cuboid with 57 contacts. We have computed a histogram of the contact order frequencies of a large sample of these MCCs (data not shown) and identified the two extremes at CO values of 13% and 26%. These topologies, numbered here “1” and “2,” respectively, were selected for our studies (Fig. ▶; Table ▶).

Ensembles sequences were designed to fold into topologies 1 and 2 (Table ▶). The goal of the design process was to identify sequences that fold rapidly and efficiently into a preselected conformation named target structure. We followed Shakhnovich and Gutin (1993) and Shakhnovich (1994) in attempting this by seeking the sequence with the lowest possible energy in the target state, as given by Equation 1. To this end, the target's coordinates were quenched and the energy of Equation 1 was annealed with respect to the sequence variables σ. This amounts to a simulated annealing in sequence space: Starting from some randomly generated sequence, transitions between different sequences (which are generated by randomly permuting pairs of beads) are successively attempted along with a suitable annealing schedule.

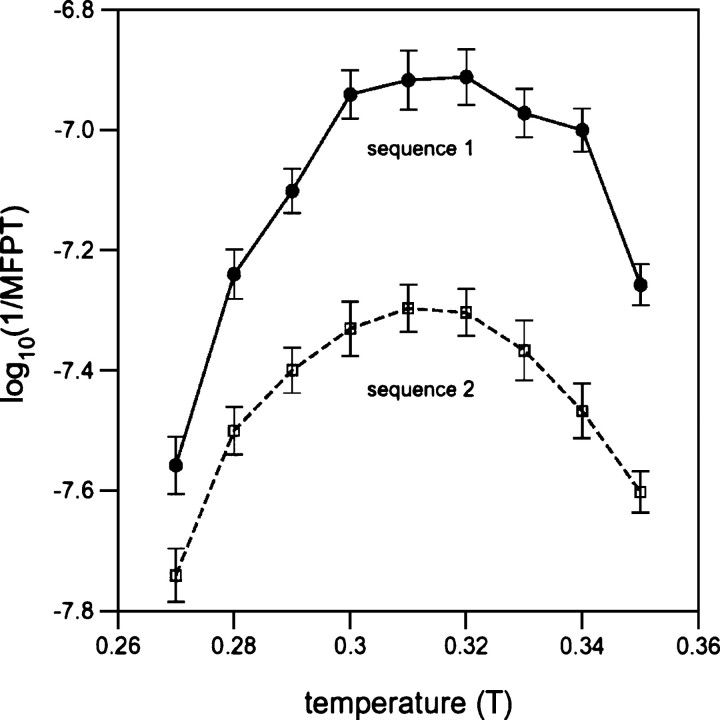

Optimal folding temperatures and folding transition temperatures

The existence of an optimal folding temperature (Topt), corresponding to the temperature at which the folding rate is maximized, has been extensively reported in lattice studies of protein folding (Shakhnovich 1994; Gutin et al. 1996, 1998b; Cieplak et al. 1999; Faísca and Ball 2002a,b; Faísca et al. 2005). In order to determine Topt, we have computed the folding times (in the absence of added cooperativity) over a broad temperature range for all six of the sequences we have investigated. Figure ▶ illustrates the dependence of the logarithmic folding rates, log10(1/MFPT), on the simulation temperature for sequences 1 and 2 folding to topologies 1 and 2, respectively. These sequences exhibit Topt of 0.32 and 0.31, respectively. Below and above these optimal temperatures, their folding slows significantly, with the stronger temperature dependence being observed at lower temperatures.

Figure 6.

The folding kinetics of MJ lattice polymers is strongly temperature-dependent. Shown is the dependence of the logarithmic folding rate, log10(1/MFPT), on the simulation temperature, T, for sequence 1 of topology 1 and sequence 2 of topology 2, under conditions of no induced cooperativity (S = 1). The optimal folding temperature is the temperature at which folding is most rapid.

For comparison with prior lattice polymer folding studies, we have determined the folding transition temperatures, Tf, of the six sequences we have used. Tf, typically denoted as the melting temperature or Tm in the experimental literature, is the temperature at which denatured states and the native state are equally populated at equilibrium. In the context of a lattice model, it can be defined as the temperature at which the average value <Q> of the fraction of native contacts is equal to 0.5 (Abkevich et al. 1995). In order to determine Tf, we averaged Q, after collapse to the native state, over MC simulations lasting at least 20 times longer than the average folding time computed at Topt. Similarly, in order to compute population histograms at Tf as a measure of thermodynamic cooperativity (Fig. ▶), data were averaged after collapse to the native state over MC simulations at least 20 times longer than the average folding time at Topt.

Acknowledgments

P.F.N.F. thanks Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia for financial support through grants SFRH/BPD/21492/2005 and POCI/QUI/58482/2004. This work was also supported by NIH grant R01GM62868-01A2 (to K.W.P.). We thank Andrew Jewett, Vijay Pande, and Joan-Emma Shea for providing critical commentary and Hue Sun Chan for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Reprint requests to: Kevin W. Plaxco, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA 93106, USA; e-mail: kwp@chem.ucsb.edu; fax: (805) 893-4120.

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.062180806.

Abbreviations: CO, contact order; MCC, maximally compact conformation; MC, Monte Carlo; MFPT, mean first passage time; MJ, Miyazawa-Jernigan.

References

- Abkevich V.I., Gutin A.M., Shakhnovich E.I. 1995. Impact of local and non-local interactions on thermodynamics and kinetics of protein folding. J. Mol. Biol. 252 460–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abkevich V.I., Gutin A.M., Shakhnovich E.I. 1996. Improved design of stable and fast-folding model proteins. Fold. Des. 1 221–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryngelson J.D. and Wolynes P.G. 1987. Spin glasses and the statistical mechanics of protein folding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 84 7524–7528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryngelson J.D. and Wolynes P.G. 1989. Intermediates and barrier crossing in a random energy model (with applications to protein folding). J. Phys. Chem. 93 6902–6915. [Google Scholar]

- Bryngelson J.D., Onuchic J.N., Socci N.D., Wolynes P. 1995. Funnels, pathways and the energy landscape of protein folding: A synthesis. Proteins 21 167–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchler N.E.G. and Goldstein R.A. 2000. Surveying determinants of protein structure designability across different energy models and amino-acid alphabets: A consensus. J. Chem. Phys. 112 2533–2547. [Google Scholar]

- Chan H.S. and Dill K.A. 1997. From Levinthal to pathways to funnels. Nat. Struct. Biol. 4 10–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan H.S. and Dill K.A. 1998. Protein folding in the landscape perspective: Chevron plots and non-Arrhenius kinetics. Proteins 30 2–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan H.S., Shimizu S., Kaya H. 2004. Cooperativity principles in protein folding. Methods Enzymol. 380 350–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cieplack M. 2004. Cooperativity and contact order in protein folding. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 69 031907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cieplak M., Henkel M., Karbowski J., Banavar J.R. 1998. Master equation approach to protein folding and kinetic traps. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80 3654–3657. [Google Scholar]

- Cieplack M., Hoang T.X., Li M.S. 1999. Scaling of folding properties in simple models of proteins. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83 1684–1687. [Google Scholar]

- Eastwood M.P. and Wolynes P.G. 2001. Role of explicitly cooperative interactions in protein folding funnels: A simulation study. J. Chem. Phys. 114 4702–4716. [Google Scholar]

- Ejtehadi M.R., Avall S.P., Plotkin S.S. 2004. Three-body interactions improve the prediction of rate and mechanism in protein folding models. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 101 15088–15093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faísca P.F.N. and Ball R.C. 2002a. Thermodynamic control and dynamical regimes in protein folding. J. Chem. Phys. 116 7231–7238. [Google Scholar]

- Faísca P.F.N. and Ball R.C. 2002b. Topological complexity, contact order, and protein folding rates. J. Chem. Phys. 117 8587–8591. [Google Scholar]

- Faísca P.F.N., da Gama M.M., Nunes A. 2005. The Gō model revisited: Native structure and the geometric coupling between local and long-range contacts. Proteins 60 712–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan K., Wang J., Wang W. 2001. Modeling two-state cooperativity in protein folding. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 64 041907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez A., Colubri A., Berry R.S. 2002. Three-body correlations in protein folding: The origin of cooperativity. Physica A (Amsterdam) 307 235–259. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie B. and Plaxco K.W. 2000. Non-glassy kinetics in the folding of a simple, single domain protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97 12014–12019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie B. and Plaxco K.W. 2004. Using protein folding rates to test protein folding theories. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73 837–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie B., Vu D., Shah P.S., Marshall S., Dyer R.B., Mayo S.L., Plaxco K.W. 2003. NMR and Temperature-jump measurements of de novo designed proteins demonstrate rapid folding in the absence of explicit selection for kinetics. J. Mol. Biol. 330 813–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindarajan S. and Goldstein R.A. 1995. Searching for foldable protein structures using optimized energy functions. Biopolymers 36 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Gromiha M.M. and Selvaraj S. 2001. Comparison between long-range interactions and contact order in determining the folding rate of two-state folders: Application of long-range order to folding rate prediction. J. Mol. Biol. 310 27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutin A.M., Abkevich V.I., Shakhnovich E.I. 1996. Chain length scaling of protein folding. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77 5433–5436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutin A.M., Abkevich V.I., Shakhnovich E.I. 1998a. A protein engineering analysis of the transition state for protein folding: Simulation in the lattice model. Fold. Des. 3 183–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutin A., Sali A., Abkevich V., Karplus M., Shakhnovich E.I. 1998b. Temperature dependence of the folding rate in a simple protein model: Search for a “glass” transition. J. Chem. Phys. 108 6466–6483. [Google Scholar]

- Jewett A., Pande V.S., Plaxco K.W. 2003. Cooperativity, smooth energy landscapes and the origins of topology-dependent protein folding rates. J. Mol. Biol. 326 247–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaya H. and Chan H.S. 2000. Energetic components of cooperative protein folding. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85 4823–4826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaya H. and Chan H.S. 2003a. Simple two-state protein folding kinetics requires near-Levinthal thermodynamic cooperativity. Proteins 52 510–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaya H. and Chan H.S. 2003b. Contact order dependent protein folding rates: Kinetic consequences of a cooperative interplay between favorable nonlocal interactions and local conformational preferences. Proteins 52 524–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaya H. and Chan H.S. 2003c. Solvation effects and driving forces for protein thermodynamic and kinetics cooperativity: How adequate is native-centric topological modeling? J. Mol. Biol. 326 911–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaya H., Liu Z., Chan H.S. 2005. Chevron behaviour and isostable enthalpic barriers in protein folding: Successes and limitations of simple Go-like modeling. Biophys. J. 89 520–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlman B. and Baker D. 2004. Exploring folding free energy landscapes using computational protein design. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 14 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau D.P. and Binder K.A. 2000. Importance sampling Monte Carlo methods. In A guide to Monte Carlo simulations in statistical physics pp. 122–123. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Makarov D.E. and Plaxco K.W. 2003. The topomer search model: A quantitative, first-principles description of two-state protein folding kinetics. Protein Sci. 12 17–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makhatadze G.I. and Privalov P.L. 1995. Energetics of protein structure. Adv. Protein Chem. 47 307–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metropolis N., Rosenbluth A.W., Rosenbluth M.N., Teller A.H., Teller E. 1953. Equation of state calculations by fast computing machines. J. Chem. Phys. 21 1087–1092. [Google Scholar]

- Miller J., Zeng C., Wingreen N.S., Tang C. 2002. Emergence of highly designable protein-backbone conformations in an off-lattice model. Proteins 47 506–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirny L.A., Abkevich V., Shakhnovich E.I. 1996. Universality and diversity of the protein folding scenarios: A comprehensive analysis with the aid of a lattice model. Fold. Des. 1 103–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirny L.A., Abkevich V.I., Shakhnovich E.I. 1998. How evolution makes proteins fold quickly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95 4976–4981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazawa S. and Jernigan R.L. 1985. Estimation of effective inter-residue contact energies from protein crystal-structures-quasi-chemical approximation. Macromolecules 18 534–552. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson E.D., Teneyck L.F., Onuchic J.N. 1997. Symmetry and kinetic optimization of proteinlike heteropolymers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79 3534–3537. [Google Scholar]

- Nymeyer H., Garca A.E., Onuchic J.N. 1998. Folding funnels and frustration in off-lattice minimalist protein landscapes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95 5921–5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onuchic J.N., Luthey-Schulten Z., Wolynes P.G. 1997. Theory of protein folding: The energy landscape perspective. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 48 545–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaxco K.W., Simmons K.T., Baker D. 1998a. Contact order, transition state placement and the refolding rates of single domain proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 277 985–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaxco K.W., Guijarro J.I., Morton C.J., Pitkeathly M., Campbell I.D., Dobson C.M. 1998b. The folding kinetics and thermodynamics of the FynSH3 domain. Biochemistry 37 2529–2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotkin S.S., Wang J., Wolynes P.G. 1997. Statistical mechanics of a correlated energy landscape model for protein folding funnels. J. Chem. Phys. 106 2932–2948. [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh S., Nakai T., Nishikawa K. 1993. A geometrical constraint approach for reproducing the native backbone conformation of a protein. Proteins 15 191–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sali A., Shakhnovich E.I., Karplus M. 1994. How does a protein fold? Nature 369 248–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalley-Kim M. and Baker D. 2004. Characterization of the folding energy landscapes of computer generated proteins suggests high folding free energy barriers and cooperativity may be consequences of natural selection. J. Mol. Biol. 338 573–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakhnovich E.I. 1994. Proteins with selected sequences fold into unique native conformation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 72 3907–3910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakhnovich E.I. and Gutin A.M. 1993. Engineering of stable and fast-folding sequences of model proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 90 7195–7199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakhnovich E., Farztdinov G., Gutin A.M., Karplus M. 1991. Protein folding bottlenecks: A lattice Monte Carlo simulation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 67 1665–1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea J.E., Onuchic J.N., Brooks C.L. 1999. Exploring the origins of topological frustration: Design of a minimally frustrated model of fragment B of protein A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96 12512–12517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu S. and Chan H.S. 2002. Anti-cooperativity and cooperativity in hydrophobic interactions: Three-body free energy landscapes and comparison with implicit-solvent potential functions for proteins. Proteins 48 15–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socci N.D., Onuchic J.N., Wolynes P.G. 1998. Protein folding mechanisms and the multidimensional folding funnel. Proteins 32 136–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada S., Luthey-Schulten Z.A., Wolynes P.G. 1999. Folding dynamics with nonadditive forces: A simulation study of a designed helical protein and a random heteropolymer. J. Chem. Phys. 110 11616–11629. [Google Scholar]

- Wyman J. and Allen D.W. 1951. The problem of the heme interactions in hemoglobin and the basis of the Bohr effect. J. Polym. Sci. 7 499–518. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y., Alonso D.O.V., Maki K., Huang C.Y., Lahr S.J., Daggett V., Roder H., DeGrado W.F., Gai F. 2003. Ultrafast folding of α(3): A de novo designed three-helix bundle protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100 15486–15491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]