Abstract

The inability to determine the structure of the buffer-insoluble Nogo extracellular domain retarded further design of Nogo receptor (NgR) antagonists to treat CNS axonal injuries. Very surprisingly, we recently discovered that Nogo-60 was soluble and structured in salt-free water, thus allowing the determination of the first Nogo structure by heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy. Nogo-60 adopts an unusual helical structure with the N- and C-terminal helices connected by a long middle helix. While the N-helix has no contact with the rest of the molecule, the C-helix flips back to pack against the 20-residue middle helix. This packing appears to trigger the formation of the stable Nogo-60 structure because Nogo-40 with the last helix truncated is unstructured. The Nogo-60 structure offered us rationales for further design of the structured and buffer-soluble Nogo-54, which may be used as a novel NgR antagonist. Furthermore, our discovery may imply a general solution to solubilizing a category of buffer-insoluble proteins for urgent structural investigations.

Keywords: CNS injury, Nogo, Nogo-66 receptor, NMR spectroscopy, water, solution structure, protein solubility, protein folding

Patients with central nervous system (CNS) injuries such as spinal cord injury, traumatic brain injury, and stroke often suffer from permanent disability because of the inability of CNS neurons to regenerate axons after injury. Previously, it was thought that the lack of CNS regeneration was due to the absence of growth-promoting factors in CNS neurons. However, recent discoveries indicate that the failure of CNS regeneration largely results from the presence of inhibitory molecules of axon outgrowth in adult CNS myelin (Lee et al. 2003; He and Koprivica 2004; Schwab 2004). So far three inhibitory proteins have been identified—namely, Nogo, myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG), and oligodendrocyte myelin glycoprotein (OMgp). All three molecules appear to initiate their inhibitory action via binding to the Nogo receptor (NgR). Of the three myelin-associated molecules, the CNS-enriched Nogo belonging to the reticulon protein family is composed of three splicing variants, namely, the 1192-residue Nogo-A, 373-residue Nogo-B, and 199-residue Nogo-C. Despite their size difference, all three Nogo variants contain a conserved extracellular domain with ∼66 residues that is capable of inhibiting neurite growth and inducing growth cone collapse. This Nogo inhibitory domain has been shown to be anchored on the oligodendrocyte surface and to bind NgR with a very high affinity (Lee et al. 2003; McGee and Strittmatter 2003; He and Koprivica 2004; Schwab 2004). Therefore, intervention in the Nogo–NgR binding provides an unprecedented opportunity for developing therapeutic agents to prompt adult CNS axonal regeneration (Brittis and Flanagan 2001; Lee et al. 2003; McGee and Strittmatter 2003; He and Koprivica 2004; Schwab 2004; Domeniconi and Filbin 2005). Such agents could also be used more broadly to repair damaged CNS axons resulting from neurodegenerative diseases such as multiple sclerosis. Indeed, a truncated form Nogo-40, which is a competitive NgR inhibitor, has been demonstrated to be able to attenuate the inhibitory effects of myelin on neurite outgrowth and promote functional recovery and long-range axonal regeneration in an animal model of spinal cord injury (GrandPre et al. 2002).

Knowledge of the three-dimensional structures of Nogo and NgR is essential for understanding their interaction as well as rational designs of molecules to mediate NgR binding. The crystal structure of the NgR ectodomain has been previously determined by two groups (Barton et al. 2003; He et al. 2003), but unfortunately the structure of Nogo in aqueous solution still remains completely unknown despite intense efforts. The insurmountable barrier for structurally studying Nogo is its insolubility in aqueous buffer. In this regard, previously we were only able to characterize the conformation of the truncated Nogo-40, which had no stable secondary structure in aqueous buffer without stabilization by 50% trifluoroethanol (TFE) (Li et al. 2004).

Very surprisingly, we have now found that a series of buffer-insoluble protein domains including Nogo can be easily solubilized in salt-free water to a high concentration. This discovery therefore allowed our first determination of the structure and backbone dynamics of Nogo-60 in aqueous solution. The results obtained further led to the successful design of the structured and buffer-soluble Nogo-54 by removing the last six unstructured residues. Nogo-54 may be used as a novel NgR antagonist to enhance CNS neuronal regeneration in the future. Moreover, our discovery also implies a general solution to solubilizing a category of buffer-insoluble proteins for urgent structural studies.

Results

Preliminary structural characterization

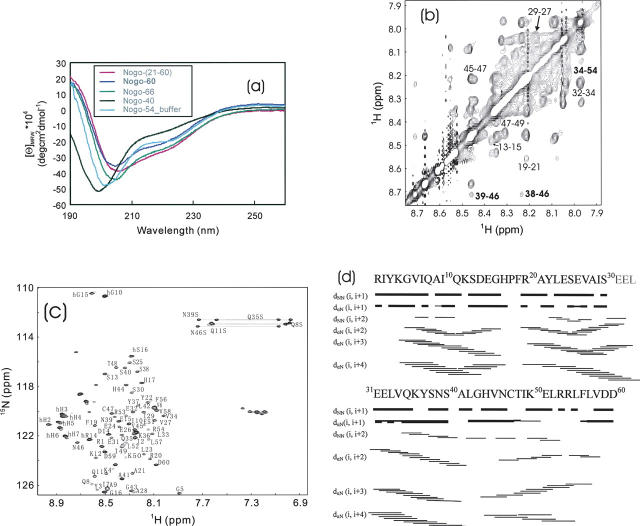

In the present study, five Nogo peptides were characterized by CD (Fig. 1a), including Nogo-54, which was later designed after the availability of the Nogo-60 structure. Out of them, Nogo-40 and Nogo-54 were soluble in both buffer and salt-free water while Nogo-(21–60), Nogo-60, and Nogo-66 were only soluble in water (pH 4.0). CD results indicated that Nogo-40 owned no stable secondary structure in water, similar to that in the buffer (Li et al. 2004). In contrast, Nogo-54 had very similar CD spectra characteristic of a helical conformation in both water and 10 mM phosphate buffer. Furthermore, HSQC spectra of Nogo-54 in the buffer and in water were almost superimposable (spectra not shown), indicating that the salt had no significant effect on its conformation. On the other hand, Nogo-(20–60), Nogo-60, and Nogo-66 were only soluble in water and showed far-UV CD spectra for a helical conformation. Most importantly, Nogo-(20–60) and Nogo-60 also had well-separated HSQC spectra (spectra not shown), recommending their suitability for further NMR structure determination. Strikingly, although Nogo-66 had concentration-independent CD spectra, the majority of its HSQC peaks were invisible even at a low peptide concentration of 50 μM (spectra not shown). This observation implied that the last six residues might be unstructured, and their inclusion would dramatically provoke conformational exchanges of Nogo-66 on micro- to millisecond timescales, thus leading to a significant NMR line-broadening. This phenomenon is analogous to our previous discovery that a slight perturbation on a small protein CHABII resulted in an extensive disappearance of NMR resonance peaks, although the secondary structure and tertiary topology remained highly native-like (Song et al. 1999; Wei and Song 2005).

Figure 1.

CD and NMR characterization of Nogo peptides. (a) Far-UV CD spectra of Nogo-(21–60) (pink), Nogo-60 (blue), Nogo-66 (green), and Nogo-40 (black) were collected in the salt-free water (pH 4.0) at 293 K on a Jasco J-810 spectropolarimeter. The far-UV CD spectrum of Nogo-54 (cyan) was acquired in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 5.4). (b) The NH-NH region of a two-dimensional 1H NMR spectrum of Nogo-60 in the salt-free water (pH 4.0) at 278 K on an 800-MHz Bruker Avance spectrometer. Some dNN(i, i + 2) NOEs are indicated, and labels of some long-range dNN NOEs are boldface. (c) The 1H–15N heteronuclear HSQC spectrum of the 15N-labeled Nogo-60 in the salt-free water (pH 4.0) at 278 K, with sequential assignments labeled. (d) The NOE patterns critical for defining the secondary structure of Nogo-60 in the salt-free water (pH 4.0) at 278 K.

Structure and 15N backbone dynamics of Nogo-60

Nogo-60 has been further assessed by NMR structure determination. As seen in Figure 1b, an extensive existence of sequential, in particular (i, i + 2) NH–NH NOEs strongly revealed that Nogo-60 assumed a well-formed helical structure in water (Wagner and Wuthrich 1982). Due to severe resonance overlaps in proton NMR spectra, Nogo-60 was subsequently studied by heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy. Figure 1c presents an assigned HSQC spectrum, and Figure 1d summarizes NOE connectivities critical for defining secondary structures. Based on characteristic NOEs including dNN(i, i + 2), dαN(i, i + 3), and dαN(i, i + 4), as well as αH conformational shifts (data not shown), it was very clear that Nogo-60 had a well-formed helical structure constituted by three helical segments.

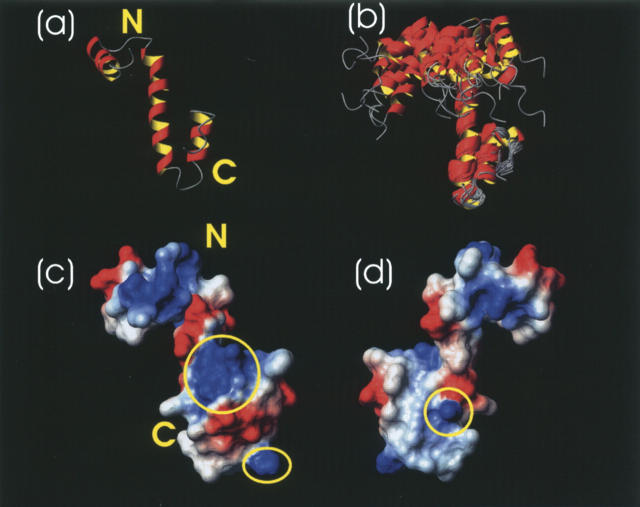

To further model the three-dimensional structure of Nogo-60, CYANA was used (Guntert 2004) with an input of 86 dihedral angles and 594 upper distance limits. Twenty accepted structures were selected for further analysis, and their structural statistics are included in Table 1. Interestingly, Nogo-60 adopted a very unusual helical structure composed of three well-formed α-helices spanning over residues 6–15, 21–40, and 45–53, followed by the unstructured residues 55–60, with the N- and C-terminal helices joined together by a very long middle helix (Fig. 2a,b). Due to the lack of any long-range NOE between the first helix and the rest of the molecule, the first helix had differential orientations in different structures. Nevertheless, as shown in Table 1, if superimposed separately, the first helix itself as well as the rest of the molecule was well defined. Very interestingly, the last helix had long-range packing with the C-half of the middle helix, as clearly evident from experimental long-range NOEs (Fig. 1b). This packing appeared to be a prerequisite for the whole Nogo-60 molecule to form the helical structure because Nogo-40 with the last helix truncated had no stable secondary structure again in water. It appears that in Nogo-60, the packing shielded the middle helix from being highly exposed to the bulk water, thus stabilizing the intrinsic helix-forming propensity of the whole molecule. In contrast, the absence of the packing in Nogo-40 might result in a severe solvation of the middle helix, thus destabilizing the helix formation. Strikingly, if the structure of Nogo-40 in 50% TFE (Li et al. 2004) was compared with the corresponding region of the Nogo-60 structure, they were similar. This implied that one mechanism for TFE to stabilize the helical structure might be to protect the helix-forming residues from a severe solvation.

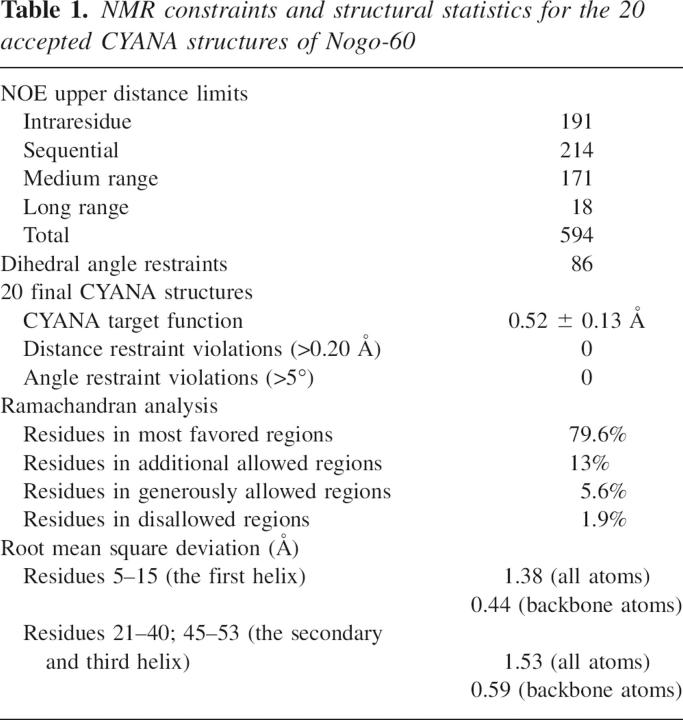

Table 1.

NMR constraints and structural statistics for the 20 accepted CYANA structures of Nogo-60

Figure 2.

Solution structure of Nogo-60. (a) The solution structure of Nogo-60 in the ribbon mode. (b) All 20 accepted Nogo-60 structures superimposed over residues 21–40 and 45–53. The electrostatic potential surface of Nogo-60 with a molecular orientation the same as Figure 3a (c) and with a 180° rotation of Figure 3c around the Z-axis (d). Positively charged patches unique for Nogo-60 and not presented in Nogo-40 were cycled.

The electrostatic potential surface plays a critical role in controlling the affinity and specificity of protein–protein interactions. Recently, several negatively charged cavities on the NgR surface were identified to be critical for binding to positively charged patches on the Nogo extracellular domain (Barton et al. 2003; He et al. 2003; Schimmele and Pluckthun 2005). However, due to the lack of the structure of the Nogo extracellular domain, the possible positively charged Nogo patches for NgR-binding remained previously unassigned. Now if we examined the potential surface of Nogo-60, two interesting observations were emerging. Firstly, in addition to the positively charged patches previously spotted in Nogo-40 (Li et al. 2004), three additional ones were identified uniquely for Nogo-60 (Fig. 2c,d). These spots could be the candidates for binding to NgR. Secondly, the C-terminal six residues, namely, Leu55–Phe56–Leu57–Val58–Asp59–Asp60, adopted no regular secondary structure but constituted an exposed hydrophobic patch in Nogo-60. We thus reasoned that this patch might contribute to the high insolubility of Nogo-60, which precipitated even with an addition of 0.2 mM sodium chloride. Therefore, we designed Nogo-54 by removing the six residues, and suddenly Nogo-54 became both buffer-soluble and helically structured as characterized by CD (Fig. 1a) and NMR (data not shown). Because Nogo-54 was helically structured and carried additional positively charged candidate spots for NgR-binding, we thus proposed that Nogo-54 might be used as a novel NgR antagonist as well as serve as a promising starting point for further design of therapeutics to enhance CNS neuronal regeneration.

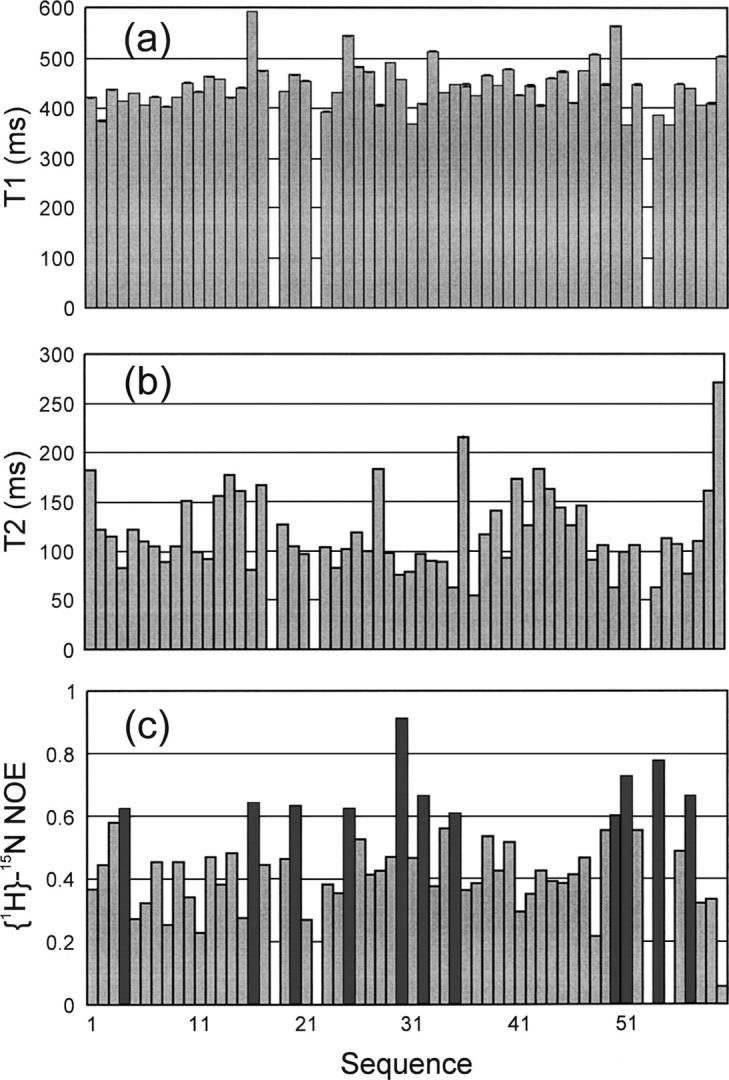

15N NMR backbone relaxation data provide valuable information for the dynamics of the local environment of a protein on the pico- to nanosecond timescale (16–18). In particular, {1H}–15N heteronuclear steady-state NOE (hNOE) provides a measure to the backbone flexibility. As seen in Figure 3c, many Nogo-60 residues had hNOE values >0.6, indicating that the regions around these residues have significantly reduced backbone motions (Kay et al. 1989; Clore et al. 1990; Farrow et al. 1994). Moreover, as shown in Figure 3b, a large portion of the Nogo-60 residues had T2 values >100 msec, implying that no significant aggregation was present at this peptide concentration in salt-free water.

Figure 3.

15N NMR backbone dynamics. The 15N NMR backbone relaxation data of Nogo-60 in the salt-free water (pH 4.0) at 278 K on an 800-MHz Bruker Avance NMR spectrometer. (a) 15N T1 (longitudinal) relaxation times, (b) 15N T2 (transverse) relaxation times, and (c) {1H}–15N steady-state NOE intensities. The bars representing residues with hNOE values >0.6 are in black.

Discussion

Nogo-40, a competitive NgR inhibitor, has been demonstrated to be able to enhance CNS axonal regeneration in vivo (GrandPre et al. 2002). This success has opened up a promising avenue to design more potent therapeutics to treat CNS axonal injuries by improving the NgR-binding affinity of the Nogo-derived molecules. However, previously—due to the lack of the structure of the Nogo extracellular domain—it was not well understood why Nogo-40 owned a relatively weak NgR-binding affinity, and as such, the rationale for further optimization was elusive. In the present study, the first successful determination of the Nogo-60 structure in aqueous solution provides important insight into this issue and implies that the weak affinity of Nogo-40 might largely result from the absence of the stable helical structure and/or some binding-important patches. The availability of the Nogo-60 structure also offered us rationales for successful design of the structured and buffer-soluble Nogo-54, which may hold promising potential to be used as a novel NgR antagonist as well as a template for further design of therapeutics to enhance CNS axonal regeneration.

The present results also contribute to our fundamental understanding of factors affecting protein folding and solubility. Our result with the packing-triggered structure formation of Nogo-60 indicates that in the present case, the local packing between the last two helices has a global effect in switching a fluctuating helical conformation observed in Nogo-40 (Li et al. 2004) to a stable one in Nogo-60. On the other hand, with regard to protein research and application, one commonly encountered but almost unconquerable problem is the insolubility of many proteins in the buffer solution (Chi et al. 2003). Although the mechanism still remains poorly understood, it is thought that in most cases the protein aggregation is dominated by the intermolecular hydrophobic clustering, and salt has significant effects on this process (Burgering et al. 1994; Baldwin 1996; Neagu et al. 2001; Ramos and Baldwin 2002; Chi et al. 2003; Zhou 2005). In general, it is believed that salt at a low concentration can increase protein solubility, while at a high concentration it will screen repulsive electrostatic interactions, thus leading to protein aggregation. At least two known mechanisms are involved in protein insolubility, namely, hydrophobic aggregation and the “salting-out” effect (Baldwin 1996). It appears that for insolubility of Nogo-60, hydrophobic aggregation may be a dominant mechanism. For such a protein, salt even at a very low concentration is already sufficient to screen repulsive electrostatic interactions and leads to hydrophobic aggregation. In this regard, here we speculate that for a category of proteins, in particular fragments/domains dissected either from cytosolic or transmembrane proteins, their specific ability to hold individual molecules apart is very weak and consequently even a very tiny amount of salt will be able to remove repulsive electrostatic interactions, thus favoring hydrophobic aggregation. Therefore, to prevent their precipitation, these protein fragments/domains should be solubilized in the aqueous solution with a minimal amount of salt. Indeed, all 10 buffer-insoluble protein fragments/domains we have investigated so far with a significant diversity of functions, locations, as well as molecular weights (from 4 to 50 kDa) were soluble in the salt-free water (M. Li, J. Liu, X. Ran, M. Fang, J. Shi, H. Qin, J. Goh, and J. Song, unpubl.). Our tested cases included fragments and entire domains isolated from either cytosolic or transmembrane proteins.

In summary, the surprising discovery that Nogo-60 was soluble and structured in the salt-free water allowed our determination of the first structure of the Nogo extracellular domain in aqueous solution. The availability of the structure offered rationales to successfully design the structured and buffer-soluble Nogo-54, which may be used as a novel NgR antagonist to enhance CNS neuronal regeneration.

Materials and methods

Cloning, expression, and purification of Nogo peptides

The human Nogo-A cDNA (designated KIAA 0886) was obtained from the Kazusa DNA Research Institute (Kazusa-Kamatari, Kisarazu, Chiba, Japan). PCR reactions with the primers listed in Supplemental Table S1 were used to generate DNA fragments encoding the human Nogo-40, Nogo-54, Nogo-(21–60), Nogo-60, and Nogo-66 peptides corresponding to Nogo-A residues 1055–1094, 1055–1108, 1075–1114, 1055–1114, and 1055–1120, respectively. The PCR fragment for Nogo-40 was subsequently cloned into GST-fusion expression vector pGEX-4T-1 (Amersham Biosciences), while the DNA fragments for Nogo-(21–60), Nogo-54, Nogo-60, and Nogo-66 were cloned into the His-tag vector pET32a (Novagen). All DNA sequences were confirmed by automated DNA sequencing, and the recombinant Nogo peptides were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 cells and subsequently purified by affinity column and HPLC as previously described (Li et al. 2004). For NMR isotope labeling, recombinant proteins were prepared by growing the cells in the M9 medium with additions of (15NH4)2SO4 for 15N labeling and (15NH4)2SO4, 13C-glucose for 15N/13C labeling, respectively (Ran and Song 2005). The identities of all Nogo peptides described above were verified by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry.

Sample preparation and circular dichroism spectroscopy

All NMR samples were prepared by dissolving the lyophilized Nogo peptides in 450 μL of Milli-Q water with an addition of 50 μL of D2O for NMR spin-lock. The sample pH was adjusted to 4.0 by adding 1–2 μL of NaOH (100 μM). The Nogo-54 samples in buffer were prepared by dissolving it in 10 mM phosphate buffer at different pH. CD experiments were performed on a Jasco J-810 spectropolarimeter equipped with a thermal controller (Li et al. 2004). The far-UV CD spectra of Nogo peptides were collected in a wide range of peptide concentrations using 1-mm path-length cuvettes with a 0.1-nm spectral resolution. Data from five independent scans were added and averaged.

NMR experiments

All NMR experiments were acquired on an 800 MHz Bruker Avance spectrometer equipped with pulse field gradient units at 278 K as described previously (Sattler et al. 1999; Ran and Song 2005). The NMR spectra acquired for both backbone and side-chain assignments included 15N-edited HSQC-TOCSY, HSQC-NOESY, as well as triple-resonance experiments HNCACB, CBCA(CO)NH, HNCO, (H)CC(CO)NH, H(CCO)NH, and HCCH-TOCSY. NOE restraints for structure calculation were mainly derived from 3D 15N and 2D 1H NOESY spectra in H2O and D2O. NMR data were processed with NMRPipe (Delaglio et al. 1995) and analyzed with NMRView (Johnson and Blevins 1994). 15N T1 and T2 relaxation times and {1H}–15N steady-state NOEs were determined on the 800-MHz spectrometer at 278 K as described previously (Kay et al. 1989; Clore et al. 1990; Farrow et al. 1994). 15N T1 values were measured from HSQC spectra recorded with relaxation delays of 10, 50, 75, 100, 125, 150, 200, 250, and 500 msec. 15N T2 values were determined with relaxation delays of 10, 60, 100, 150, 180, 210, 240, and 300 msec. {1H}–15N steady-state NOEs were obtained by recording spectra with and without 1H presaturation of duration 3 sec plus a relaxation delay of 5 sec at 800 MHz.

NMR structure determination

For structure calculation, a set of manually assigned unambiguous NOE restraints together with dihedral angle restraints predicted by the TALOS program based on chemical shift values was used to calculate initial structures of Nogo-60 by the CYANA program (Guntert 2004). With the availability of the initial structure, more NOE cross-peaks in the two NOESY spectra were automatically assigned by the CYANA program followed by a manual confirmation. After many rounds of refinement, a final set of unambiguous NOE and dihedral angle restraints was used for structure calculations by CYANA. The 20 structures accepted by CYANA were checked by PROCHECK (Laskowski et al. 1996) and subsequently analyzed by use of the graphic software MolMol (Koradi et al. 1996).

Protein Data Bank accession code

The structure coordinate of Nogo-60 was deposited at the Protein Data Bank with PDB code 2G31.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professors Robert L. Baldwin at Stanford School of Medicine and Walter Englander at University of Pennsylvania for their kind and critical comments on salt effects on protein stability and solubility; and Professor R. Kaptein for communicating precious observations on Mnt repressor. We thank Dr. Jingsong Fan for collecting three-dimensional NMR spectra on the 800-MHz NMR spectrometer. This study is supported by the Biomedical Research Council of Singapore (BMRC) grant R-183-000-097-305, BMRC Young Investigator Award R-154-000-217-305 (to J.S.).

Footnotes

Supplemental material: see www.proteinscience.org

Reprint requests to: Jianxing Song, Department of Biochemistry, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, 10 Kent Ridge Crescent, Singapore 119260, Singapore; e-mail: bchsj@nus.edu.sg; fax: +(65) 6779-2486.

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.062306906.

References

- Baldwin R.L. 1996. How Hofmeister ion interactions affect protein stability. Biophys. J. 71: 2056–2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton W.A., Liu B.P., Tzvetkova D., Jeffrey P.D., Fournier A.E., Sah D., Cate R., Strittmatter S.M., Nikolov D.B. 2003. Structure and axon outgrowth inhibitor binding of the Nogo-66 receptor and related proteins. EMBO J. 22: 3291–3302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittis P.A. and Flanagan J.G. 2001. Nogo domains and a Nogo receptor: Implications for axon regeneration. Neuron 30: 11–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgering M.J., Boelens R., Gilbert D.E., Breg J.N., Knight K.L., Sauer R.T., Kaptein R. 1994. Solution structure of dimeric Mnt repressor (1-76). Biochemistry 33: 15036–15045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi E.Y., Krishnan S., Randolph T.W., Carpenter J.F. 2003. Physical stability of proteins in aqueous solution: Mechanism and driving forces in nonnative protein aggregation. Pharm. Res. 20: 1325–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clore G.M., Driscoll P.C., Wingfield P.T., Gronenborn A.M. 1990. Analysis of the backbone dynamics of interleukin-1 β using two-dimensional inverse detected heteronuclear 15N–1H NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry 29: 7387–7401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G.W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., Bax A. 1995. NMRPipe: A multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6: 277–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domeniconi M. and Filbin M.T. 2005. Overcoming inhibitors in myelin to promote axonal regeneration. J. Neurol. Sci. 233: 43–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrow N.A., Muhandiram R., Singer A.U., Pascal S.M., Kay C.M., Gish G., Shoelson S.E., Pawson T., Forman-Kay J.D., Kay L.E. 1994. Backbone dynamics of a free and phosphopeptide-complexed Src homology 2 domain studied by 15N NMR relaxation. Biochemistry 33: 5984–6003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GrandPre T., Li S., Strittmatter S.M. 2002. Nogo-66 receptor antagonist peptide promotes axonal regeneration. Nature 417: 547–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guntert P. 2004. Automated NMR structure calculation with CYANA. Methods Mol. Biol. 278: 353–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z. and Koprivica V. 2004. The Nogo signaling pathway for regeneration block. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 27: 341–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X.L., Bazan J.F., McDermott G., Park J.B., Wang K., Tessier-Lavigne M., He Z., Garcia K.C. 2003. Structure of the Nogo receptor ectodomain: A recognition module implicated in myelin inhibition. Neuron 38: 177–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B.A. and Blevins R.A. 1994. NMRView: A computer program for the visualization and analysis of NMR data. J. Biomol. NMR 4: 603–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay L.E., Torchia D.A., Bax A. 1989. Backbone dynamics of proteins as studied by 15N inverse detected heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy: Application to staphylococcal nuclease. Biochemistry 28: 8972–8979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koradi R., Billeter M., Wüthrich K. 1996. MOLMOL: A program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Graph. 14: 51–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski R.A., Rullmann J.A., MacArthur M.W., Kaptein R., Thornton J.M. 1996. AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: Programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J. Biomol. NMR 8: 477–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D.H., Strittmatter S.M., Sah D.W. 2003. Targeting the Nogo receptor to treat central nervous system injuries. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2: 872–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Shi J., Wei Z., Teng F.Y., Tang B.L., Song J. 2004. Structural characterization of the human Nogo-A functional domains. Solution structure of Nogo-40, a Nogo-66 receptor antagonist enhancing injured spinal cord regeneration. Eur. J. Biochem. 271: 3512–3522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee A.W. and Strittmatter S.M. 2003. The Nogo-66 receptor: Focusing myelin inhibition of axon regeneration. Trends Neurosci. 26: 193–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neagu A., Neagu M., Der A. 2001. Fluctuations and the Hofmeister effect. Biophys. J. 81: 1285–1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos C.H. and Baldwin R.L. 2002. Sulfate anion stabilization of native ribonuclease A both by anion binding and by the Hofmeister effect. Protein Sci. 11: 1771–1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran X. and Song J. 2005. Structural insight into the binding diversity between the Tyr phosphorylated human ephrinBs and Nck2 SH2 domain. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 19205–19212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler M., Schleucher J., Griesinger C. 1999. Heteronuclear multidimensional NMR experiments for the structure determination of proteins in solution employing pulsed field gradients. Prog. NMR Spectroscopy. 34: 93–158. [Google Scholar]

- Schimmele B. and Pluckthun A. 2005. Identification of a functional epitope of the Nogo receptor by a combinatorial approach using ribosome display. J. Mol. Biol. 352: 229–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab M.E. 2004. Nogo and axon regeneration. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 14: 118–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J., Jamin N., Gilquin B., Vita C., Menez A. 1999. A gradual disruption of tight side-chain packing: 2D 1H-NMR characterization of acid-induced unfolding of CHABII. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6: 129–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner G. and Wuthrich K. 1982. Sequential resonance assignments in protein 1H nuclear magnetic resonance spectra. Basic pancreatic trypsin inhibitor. J. Mol. Biol. 155: 347–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Z. and Song J. 2005. Molecular mechanism underlying the thermal stability and pH induced unfolding of CHABII. J. Mol. Biol. 348: 205–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H.X. 2005. Interactions of macromolecules with salt ions: An electrostatic theory for the Hofmeister effect. Proteins 61: 69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]