Abstract

An active site containing a CXXC motif is always found in the thiol-disulphide oxidoreductase superfamily. A survey of crystal structures revealed that the CXXC motif had a very high local propensity (26.3 ± 6.2) for the N termini of α-helices. A helical peptide with the sequence CAAC at the N terminus was synthesized to examine the helix-stabilizing capacity of the CXXC motif. Circular dichroism was used to confirm the helical nature of the peptide and study behavior under titration with various species. With DTT, a redox potential of Eo = −230 mV was measured, indicating that the isolated peptide is reducing in nature and similar to native human thioredoxin. The pKa values of the individual Cys residues could not be separated in the titration of the reduced state, giving a single transition with an apparent pKa of 6.74 (±0.06). In the oxidized state, the N-terminal pKa is 5.96 (±0.05). Analysis of results with the modified helix-coil theory indicated that the disulfide bond stabilized the α-helical structure by 0.5 kcal/mol. Reducing the disulfide destabilizes the helix by 0.9 kcal/mol.

Keywords: α-helix, N-cap, N3, circular dichroism, protein folding, protein stability, CXXC, helix-coil theory

An active site containing a CXXC motif is always found in the thiol-disulphide oxidoreductase superfamily. This superfamily includes thioltransferase, thioredoxin, glutaredoxin, and protein disulphide isomerase. In all of these proteins characterized thus far, the first and the second Cys in the motif are always at the N-cap and N3 positions of an α-helix. Residues in these positions are in close proximity and can potentially interact with each other. There have been a few studies on the CXXC motif in an isolated peptide (Ookura et al. 1995; Nguyen et al. 2003) and no study on its effect on helical structure and stability. Disulphides have been shown to stabilize helical peptides based on apamin, though with a different spacing and location in the helix (Pease et al. 1990). Here we synthesized a helical peptide containing the CXXC motif to understand its behavior, independent of the tertiary structure and neighboring amino acids. Its energetic properties were analyzed using the helix-coil theory.

Results and Discussion

Design of the CAAC peptide

An intrinsically helical poly-Ala peptide with a sequence of NH2-CAACAAAAKAAAAKGY-NH2 was used to study the CXXC motif in an isolated α-helix. The nomenclature for a helical sequence is as follows: …-N″-N′-N-cap-[N1-N2-N3-........-C3-C2-C1]-C-cap -C′-C″-.... The N-cap residue is the last residue with nonhelical ψ/ϕ angles prior to the start of the helix, and the C-cap residue is the first such residue after the end of the helix.

The first Cys in the above sequence will often act as the N-cap, as Cys is a strong N-cap (Doig et al. 1994), while Ala is a poor N-cap but relatively good at both the N1 and N2 positions (Cochran and Doig 2001; Cochran et al. 2001). Cys, however, is not commonly found at either N1 or N2. The α-helix should therefore initiate with the first Cys as as the N-cap, making the second Cys an N3 residue, even though it is not heavily preferred in this position in isolation (Iqbalsyah and Doig 2004). Helices that initiate with either of the first two Ala residues as an N-cap, and hence the second Cys at N1 or N2, will be unfavorable and have low populations in the sample. The two Cys residues are in close spatial proximity in this peptide, allowing them to easily interact with each other. The positively charged Lys residues, included for solubility, are spaced i, i + 5 to each other and to the second Cys residue so that no interactions between them can take place. The Tyr residue is present to give the peptide a UV absorption for concentration determination. The penultimate Gly ensures that the α-helix almost always terminates at or before this position so that the Tyr does not affect the CD signal (Chakrabartty et al. 1993).

Circular dichroism measurements

The peptide gave typical helical CD spectra, with minima at 208 and 222 nm (data not shown). It had a concentration-independent CD signal at 222 nm, showing no indication of aggregation between 5 and 200 μM. Oxygen-free buffers were always used in the experiments to control the formation of disulphide bonds. Data from oxidation tests suggest that the disulphide bond from the two Cys residues is readily formed after dissolution of the pure, solid peptide (data not shown). Further oxidation by adding H2O2 to the peptide solution, as well as purging with O2, followed by prolonged incubation at room temperature, does not increase the helix content. This implies that the maximum level of disulphide bond formation is attained rapidly after solvation.

The N termini of naturally occurring helices in proteins are very often solvent-exposed (Doig et al. 1997). The CXXC motif in thiol-disulphide oxidoreductases is also partially exposed to solvent, so the CAAC peptide may be a good model for the study of a CXXC motif that is relative in isolation from neighboring interactions.

pH titration of the CAAC peptides

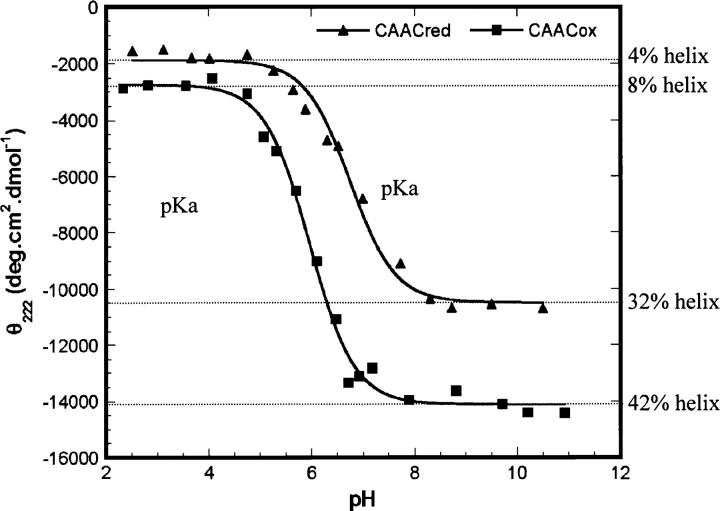

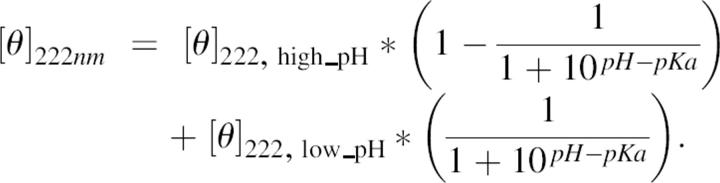

The helicities of CAACox and CAACred peptides were followed as a function of pH using far UV CD. Values of pKa for the ionizable side-chain groups were evaluated between approximately pH 2–11 by curve-fitting the CD data to the Henderson-Hasselbach equation (Fig. 1). The upper range of accessible pH is given by Lys deprotonation, which leads to peptide aggregation. The terms CAACox and CAACred refer to the CAAC peptide with and without the disulphide bond, respectively.

Figure 1.

pH titration of CAACred and CAACox measured by CD spectra at 222 nm in 5 mM phosphate buffer containing 10 mM NaCl at 0°C.

Titrations of CAACred demonstrate that protonated Cys is less stabilizing to the helix than negatively charged Cys. As the pH rises above the pKa, helix content increases maximally by 34% and 28% for CAACox and CAACred, respectively. The helicity of CAACox increases by ∼10% in comparison to CAACred at high pH, suggesting that the disulphide bond formation stabilizes the α-helix.

The apparent pKa values of CAACox and CAACred are 5.96 (±0.05) and 6.74 (±0.06), respectively (Fig. 1). The pKa of the CAACox is due to the N-terminal amine and its N-cap interaction, whereas the pKa for CAACred is an apparent one with contributions from the N-terminal amine and each of the free Cysteine residues. The reported pKa values for the individual Cys at N-cap and N3 in isolated α-helical peptides are 6.18 (±0.19) (Doig et al. 1994) and 7.73 (±0.12) (Iqbalsyah and Doig 2004), respectively. These values differ significantly from the pKa of Cys in a coil peptide (8.69 [±0.07]) (Kortemme and Creighton 1995). This is not unusual in thioredoxins, where more N-terminal active-site cysteine is generally a strong nucleophile with an abnormally low pKa value. In contrast, the more C-terminal cysteine is substantially buried in the native proteins, and little is known about its effective pKa during catalysis of disulfide exchange reactions (Mössner et al. 2000).

The pKa values of the two Cys residues and the N terminus in CAACred cannot be separated completely in this study. Figure 1 shows only one observable transition across the pH range studied, implying that the pH transition and hence pKa values of these groups are similar. There is a discrepancy between our peptides and thioredoxin systems, for which the pKa value of Cys at N-cap is substantially lower than that at N3 (Chivers et al. 1997b; Mössner et al. 2000). This could be due to (1) interaction of proximal residues to both Cys; (2) the N3 (Cys) is buried; (3) N-cap (Cys) is more easily made anionic at increased pH making deprotonation of N3 (Cys) difficult; (4) differences in peptide dipole interactions with N-cap (Cys) and N3 (Cys). In contrast, the two Cys residues in CAAC peptides are both solvent-exposed and in isolation from other interactions. The titration behavior is thus less complex. The reasons for the perturbation of the pKa values of Cys residues include (1) interaction between thiolate and peptide dipoles at the helix N terminus, (2) hydrogen bonding between thiolate anion with one of the unsatisfied amide groups at the N terminus, and (3) a reciprocal hydrogen bond between the two Cys residues.

Redox properties of the CAAC peptide

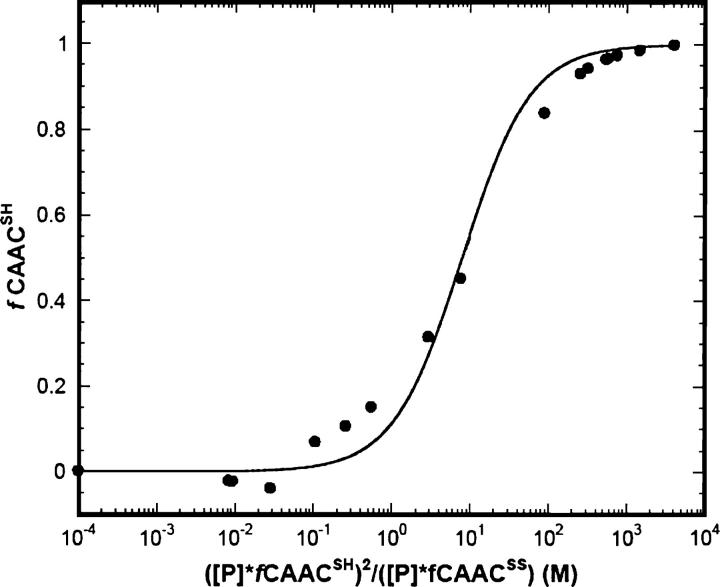

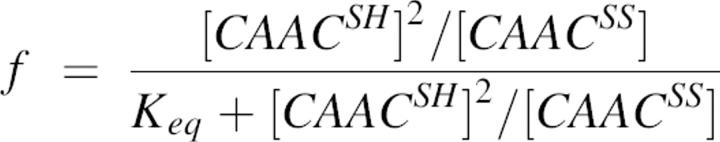

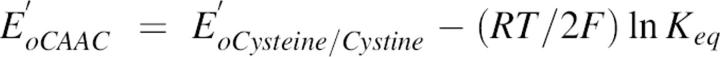

The redox potential of the CXXC motif was determined in the CAACox peptide by quantifying the steady-state ratios of its reduced and oxidized forms in the presence of DTT. The redox potential of DTT is low and capable of maintaining monothiols completely in the reduced state and of reducing disulphides quantitatively (Cleland 1964). Nonlinear least-squares analysis of data shown in Figure 2 gives an equilibrium constant for the redox couple of 7.9 ± 1.0 M. The standard-state redox potential Eo′ of the CAAC peptide can be calculated from the equilibrium constant of the redox reaction involving the redox potential of DTT at the experimental pH of 8.1 using the Nernst equation (see Materials and Methods). This gives a value of Eo′ = −230 mV. The reported Eo′ value of protein disulphide isomerase-like thioredoxin is −235 mV (Lundstrom and Holmgreen 1993) and that for human thioredoxin is −230 mV (Watson et al. 2003), suggesting that the CXXC motif in the CAAC peptide is reducing.

Figure 2.

Redox equilibrium between CAACox peptide and DTT measured by CD spectra at 222 nm in 5 mM phosphate buffer containing 10 mM NaCl at 0°C.

Computer modeling

Using a model peptide (sequence CAACAAAAKAAAAKGY) with techniques as previously published (Moutevelis and Warwicker 2004; Warwicker 2004), we investigated the pKa and redox potential of our peptide in comparison with human thioredoxin. The C-terminal carbonyl group was omitted from the calculations so that there is no net C-terminal charge. The model peptide was generated in QUANTA with subsequent torsion about the α-carbon-to-carboxyl-carbon bond to swap the side chain and N-terminal amino group locations, i.e., placing the Cys side chain into position to interact favorably with the helix terminal NH groups rather than the unfavorably interacting N-terminal group.

We obtain calculated pKa values of 4.5, 6.5, and 8.2 for the N-terminal, N-cap Cys, and N3 Cys, respectively. The N terminus and N-cap Cys pKa values are tightly coupled, consistent with the pH range of helix structure titration observed experimentally for the reduced peptide (Fig. 1). A predicted N3 Cys pKa of 8.2 is very close to an unshifted Cys pKa (8.3), implying that the difference between protonated and deprotonated N3 Cys for the peptide of around pH 8 is small. This is consistent with no significant influence of ionization on helix percentage above pH 8 (Fig. 1). An intermediate in our modeling process (before swapping of the N terminus and N-cap Cys side-chain locations) gives calculated pKa values of 2.6, 8.2, and 7.9 for the N-terminal amino, N-cap Cys, and N3 Cys, respectively. This is inconsistent with the pH 4–8 ionization range obtained experimentally and supports our use of the modeled peptide with the side chain of N-cap Cys located in the N-cap position.

The N-terminal pKa for the oxidized model peptide is calculated to be 4.4. This is a lot lower than the 5.96 from experiment. However, both values are significantly reduced in comparison to the model compound value of ∼7.5. The major factor reducing the pKa in the calculations is the interaction with the peptide dipoles at the helix terminus. Such an unfavorable interaction would be likely to cause some disruption to mitigate this effect, e.g., some splaying of the dipoles out of line and strained hydrogen bonds to the second helical turn. This discrepancy is therefore not unexpected for calculations on a rigid model helix.

The redox potential difference between the modeled peptide and human thioredoxin is calculated as +10 mV at pH 7.0. Given that human thioredoxin has a measured redox potential of −230 mV (Watson et al. 2003) for the active site C-C, we estimate the redox potential of the CAAC peptide at −220 mV. This compares with the experimental result of −231 mV, which is a reasonable agreement given the range of values covering both small molecules and the thioredoxin superfamily.

Lifson-Roig helix coil theory to calculate ΔG of interactions in CAAC peptide

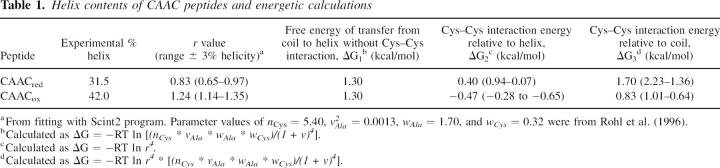

The use of the helix-coil theory is essential to quantitatively interpret the helix/coil equilibrium. When an interaction occurs involving the two Cys residues, the existing helix-coil theory that includes side-chain interactions (Stapley et al. 1995) needs additional considerations, although the basic algorithm remains unchanged. The most significant change in the calculation is that the CAAC sequence is treated as a block. This approach has been utilized previously to calculate side-chain interactions of residues in h conformations (Kise and Bowler 2002). This interaction involves interacting and intervening residues that are not all in h states, so using q for this i,i + 3 interaction is not appropriate. The i,i + 3 interaction between N-cap (Cys) and N3 (Cys) in the block is assigned statistical weight r4, as r perturbs the weights of four consecutive residues. For example, N-cap (Cys), N1 (Ala), and N2 (Ala) and N3 (Cys) will have conformational weights r.ncys, r.vala, r.wala, and r.wcys, respectively. This differs from the original theory that assigned only the residue in the middle of a quartet a statistical weight q. The r-values were varied using the Scint2 program until the calculation agrees with the experimentally determined helix content. The interaction energies in the CAAC block can be calculated simply as ΔG = −RT ln Keq. The energy is arbitrarily relative to the reduced form of the helical CAAC (Table 1).

Table 1.

Helix contents of CAAC peptides and energetic calculations

Using r = 1 in this calculation (i.e., there are no side-chain interactions), the predicted helicity is 35.6%. A value of r of 0.83 gives the experimental helicity of 31.5% for CAACred. Calculating r for CAACox results in a value of 1.24. To test the maximum helicity that can be achieved, we set r equal to infinity. This gave a predicted helicity of 76.7%. If there was no Cys–Cys interaction (i.e., r = 1), transferring the CAAC block from totally random coil to helix conformation would cost 1.30 kcal/mol. This is altered to 0.83 kcal/mol when the Cys–Cys disulphide bond is present and to 1.70 kcal/mol when the Cys side chains are reduced. The disulphide bond in CAACox stabilizes the helix by −0.47 kcal/mol (ΔG = −0.28 to −0.65 kcal/mol), while the reduced CAAC motif destabilizes the helix by 0.4 kcal/mol (ΔG = 0.9–0.1 kcal/mol. The stabilizing effect of the covalent link on the helix is similar to that given by an i,i + 4 lactam bridge (Taylor 2002), though it is substantially weaker than a His-Ru(III)-His cross-link (Kise and Bowler 2002).

The capping box and CXXC motif

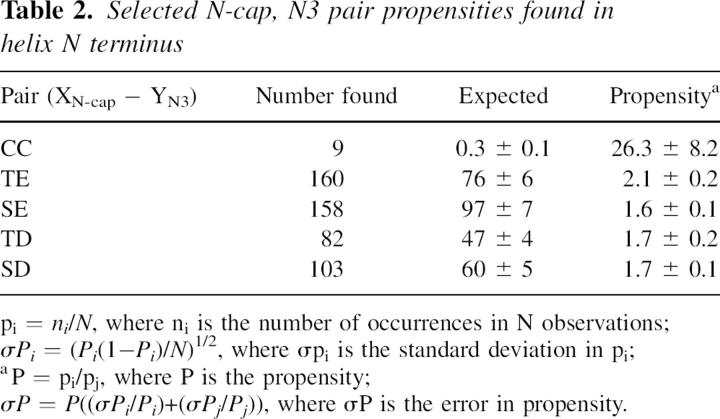

The capping box is a well-known stabilizing motif at a helix N terminus involving a reciprocal hydrogen bond from the N-cap position (mostly Ser and Thr) with polar residues at the N3 position (mostly Asp and Glu) (Harper and Rose 1993; Wan and Milner-White 1999). We explored the possibility that CXXC is a new variant of capping box through a survey of protein crystal structures, not distinguishing between reduced and oxidized Cys (Table 2).

Table 2.

Selected N-cap, N3 pair propensities found in helix N terminus

Propensities are used to normalize frequency so that a tendency of a particular amino acid to be at certain positions can be observed. The propensities shown here are “local,” that is, the ratio between the amino acid frequency found in a defined position, i.e., N-cap and N3, and the amino acid frequency found only in helices. If the frequency of an amino acid found in a certain position is different from that expected from a random distribution, the amino acid is then either preferred (propensity >1) or not preferred (propensity <1) in that position.

Among the other 399 combinations (data not shown), CC at N-cap and N3 has a propensity of 26.3 (±8.2), which is exceptionally high. Cys is one of the rarest residues found in proteins including in helices (see also Penel et al. 1999). This lessens the chance of finding the CC pair in helices, making uncertainties in propensity calculations large. Interactions between Thr/Ser and Asp/Glu are also preferred, although the propensities are not high and the errors are lower due to the increased frequencies of these residues.

Conclusions

The CAAC motif stabilizes the α-helical structure of the peptide and has similar values of redox potential to those found in natural thioredoxins. Modeling studies also show that this motif, in its reduced form, may be a variation on the capping-box theme. The side chains of the N-cap Cys residues are able to form a hydrogen bond with the amide nitrogen of the N3 residue (also Cys in this case). The α-helix is stabilized by the Cys (N-cap) to Cys (N3) disulphide bond by −0.5 kcal/mol. When the Cys side chains are both reduced, the Cys (N-cap)-to-Cys (N3) repulsion destabilizes the helix by 0.4 kcal/mol.

Materials and methods

Peptide synthesis

The peptide, dubbed CAAC peptide, was synthesized by the solid-phase method using a standard 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (Fmoc) strategy on an Applied Biosystem 433A peptide synthesizer. C-terminal amides were made using Rink Amide resin (CN Biosciences). Peptides were cleaved from the resin using 95% trifluoroacetic acid, 2.5% triisopropylsilane, and 2.5% water. Peptides were then purified by C18 reverse-phase HPLC and its molecular weight was checked by MALDI mass spectrometry. Final purity was assessed checked using analytical C18 HPLC. Peptide concentration was determined by measuring tyrosine UV absorbance of aliquots of stock solution dissolved in water using ɛ275 = 1390 M−1·cm−1 (Brandts and Kaplan 1973).

Circular dichroism measurements

Equilibrium CD measurements were made at 222 nm with a Jasco J810 spectropolarimeter at 273 K, 0°C. Ellipticity was measured in 5 mM sodium phosphate containing 10 mM NaCl in a 3-mL quartz cell with a 1.0-cm path length, unless stated otherwise. CD data in mdeg were converted to mean residue ellipticity using [θ]222(observed) = θ/(molar concentration × 16 residues × 10), in deg.cm2.dmol−1. Helix content was calculated as [θ]222(observed)/[θ]222(max). [θ]222(max) is given by −40,000 * (1 − 2.5/n), where n is the number of amino acids in the peptide (Chen et al. 1974).

pH titration

Titrations were performed in the presence or the absence of reducing agent (DTT). In the presence of DTT, the DTT:peptide ratio used was 20:1. The buffer used for pH titrations contained 10 mM NaCl, 1 mM sodium phosphate, 1 mM sodium borate, and 1 mM sodium citrate. The pH meter was calibrated for measurements at 273 K. The pH was adjusted during the titrations with aliquots of HCl or NaOH. Only data in the pH range where the equilibrium is reversible were used. The ellipticity data from the titrations were fitted to a Henderson-Hasselbach equation for one apparent pKa.

|

[θ]222 high_pH and [θ]222 low_pH are the molar ellipticities measured at the titration end points at high and low pH.

DTT titration

The redox potential of the CAAC peptide was determined by titrating a 20-μM peptide solution with DTT of known concentrations. The final concentration of DTT in the solution was calculated after correcting for the volume of the solution. Peptide was dissolved in CD buffer containing 5 mM sodium phosphate and 10 mM NaCl (pH 8.1). Prior to use, the buffer was thoroughly degassed and flushed with nitrogen. Peptide solution with added DTT was allowed to equilibrate for 15 min at room temperature before taking CD measurement.

The equilibrium constant, Keq, of thiol-disulphide pair in the equilibrium system was calculated according to the following equation (Inaba and Ito 2002):

|

where f is the fraction of the reduced CAAC peptide at equilibrium, which is equal to the fractional change of θ222 measured at every point after DTT addition. CAACSH and CAACSS are peptide in reduced and oxidized forms, respectively. The standard redox potential was calculated from the Nernst equation, using a value of −0.366 V for the DTT at pH 8.1 at room temperature (Cleland 1964).

|

where F and R are the Faraday and the gas constants, respectively.

Analysis using the helix-coil theory

We determined r-values using a statistical mechanical algorithm implemented in the program Scint2 (http://www.bi.umist.ac.uk/users/mjfajdg/scint.htm). Scint2, an actual SGI executable program, implements the modified Lifson-Roig helix-coil theory to include N- and C-capping (Doig et al. 1994) and side-chain interactions (Stapley et al. 1995) to calculate the helix content for peptide of a given sequence. All c-values were set to 1; other parameters were taken from Rohl et al. (1996).

Database search

A survey was conducted on a data set obtained from a cull of crystal structures in the ASTRAL database (SCOP 1.63 Sequence Resources) (Brenner et al. 2000). The data set contained 1135 chains with a total of 195,875 amino acid residues, and there was <20% sequence identity. These were processed to give secondary structure information using DSSP algorithm as implemented in the program SSTRUC (D.K. Smith and J.M. Thornton, University College London).

Firstly, the data set was probed for helices of at least seven helical residues, of which there were 4778. The frequencies of all 400 possible amino acid pairs at different positions in the N-terminal region of these helices were then examined, along with the frequencies of each amino acid at each position (N-cap, N1, N2, and N3).

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by The Wellcome Trust (award reference 065106). The Michael Barber Mass Spectrometry Facility at UMIST is thanked for verifying peptide identity. T.M.I. thanks the TPSD Project of the Ministry of National Education of The Republic of Indonesia for the scholarship.

Footnotes

Reprint requests to: Andrew J. Doig, Manchester Interdisciplinary Biocentre, The University of Manchester, 131 Princess Street, Manchester M1 7ND, UK; e-mail: andrew.doig@manchester.ac.uk; fax: +44-161-236-0409.

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.062271506.

References

- Brandts J.R. and Kaplan K.J. 1973. Derivative spectroscopy applied to tyrosyl chromophores. Studies on ribonuclease, lima bean inhibitor, and pancreatic trypsin inhibitor. Biochemistry 10: 470–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S.E., Koehl P., Levitt M. 2000. The ASTRAL compendium for sequence and structure analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 28: 254–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabartty A., Kortemme T., Padmanabhan S., Baldwin R.L. 1993. Aromatic side-chain contribution to far-ultraviolet circular dichroism of helical peptides and its effect on measurement of helix propensities. Biochemistry 32: 5560–5565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.-H., Yang J.T., Chau K.H. 1974. Determination of the helix and β form of proteins in aqueous solution by circular dichroism. Biochemistry 13: 3350–3359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chivers P.T., Prehoda K.E., Volkman B.F., Kim B.-M., Markley J.L., Raines R.T. 1997b. Microscopic pKa values of Escherichia coli thioredoxin. Biochemistry 36: 14985–14991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland W.W. 1964. Dithiothreitol, a new protective reagent for SH groups. Biochemistry 3: 480–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran D.A.E. and Doig A.J. 2001. Effects of the N2 residue on the stability of the α-helix for all 20 amino acids. Protein Sci. 10: 1305–1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran D.A.E., Penel S., Doig A.J. 2001. Contribution of the N1 amino acid residue to the stability of the α-helix. Protein Sci. 10: 463–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doig A.J., Chakrabartty A., Klingler T.M., Baldwin R.L. 1994. Determination of free energies of N-capping in α-helices by modification of the Lifson-Roig helix-coil theory to include N- and C-capping. Biochemistry 33: 3396–3403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doig A.J., MacArthur M.W., Stapley B.J., Thornton J.M. 1997. Structures of N-termini of helices in proteins. Protein Sci. 6: 147–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper E.T. and Rose G.D. 1993. Helix stop signals in proteins and peptides: The capping box. Biochemistry 32: 7605–7609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaba K. and Ito K. 2002. Paradoxical redox properties of DsbB and DsbA in the protein disulfide-introducing reaction cascade. EMBO J. 21: 2646–2654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbalsyah T.M. and Doig A.J. 2004. Effect of the N3 residue on the stability of the α-helix. Protein Sci. 13: 32–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kise K.J. and Bowler B.E. 2002. Induction of helical structure in a heptapeptide with a metal cross-link: Modification of the Lifson-Roig Helix-coil theory to account for covalent cross-links. Biochemistry 41: 15826–15837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kortemme T. and Creighton T.E. 1995. Ionisation of cysteine residues at the termini of model α-helical peptides. Relevance to unusual thiol pKa values in proteins of the thioredoxin family. J. Mol. Biol. 253: 799–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundstrom J. and Holmgren A. 1993. Determination of reduction-oxidation potential of the thioredoxin-like domains of protein disulfide-isomerase from the equilibrium with gluthathione and thioreoxin. Biochemistry 32: 6649–6655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mössner E., Iwai H., Glockshuber R. 2000. Influence of the pKkavalue of the buried, active-site cysteine on the redo properties of thioredoxin-like oxidoreductases. FEBS Lett. 477: 21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moutevelis E. and Warwicker J. 2004. Prediction of pKa and redox properties in the thioredoxin superfamily. Protein Sci. 13: 2744–2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen M.T., Beck J., Lue H., Finfzig H., Kleemann R., Koolwijk P., Kapurniotu A., Bernhagen J. 2003. A 16-residue peptide fragment of macrophage migration inhibitory factor, MIF-(50-65), exhibits redox activity and has MIF-like biological functions. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 33654–33671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ookura T., Kainuma K., Kim H.J., Otaka A., Fujii N., Kawamura Y. 1995. Active site peptides with CXXC motif on MAP-resin can mimic protein disulfide isomerase activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 213: 746–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pease J.H.B., Storrs R.W., Wemmer D.E. 1990. Folding and activity of hybrid sequence, disulfide stabilized peptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 87: 5643–5647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penel S., Hughes E., Doig A.J. 1999. Side-chain structures in the first turn of the α-helix. J. Mol. Biol. 287: 127–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohl C.A., Chakrabartty A., Baldwin R.L. 1996. Helix propagation and N-cap propensities of the amino acids measured in alanine-based peptides in 40 volume percent trifluoroethanol. Protein Sci. 5: 2623–2637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapley B.J., Rohl C.A., Doig A.J. 1995. Addition of side chain interactions to modified Lifson-Roig helix-coil theory: Application to energetics of phenylalanine-methionine interactions. Protein Sci. 4: 2383–2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J.W. 2002. The synthesis and study of side-chain lactam-bridged peptides. Biopolymers 66: 49–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan W.Y. and Milner-White E.J. 1999. A natural grouping of motifs with an aspartate or asparagine residue forming two hydrogen bonds to residues ahead in sequence: Their occurrence at α-helical N termini and in other situations. J. Mol. Biol. 286: 1633–1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warwicker J. 2004. Improved pKa calculations through flexibility based sampling of a water-dominated interaction scheme. Protein Sci. 13: 2793–2805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson W.H., Pohl J., Montfort W.R., Stuchlik O., Reed M.S., Powis G., Jones D.P. 2003. Redox potential of human thioredoxin 1 and identification of a second dithiol/disulfide motif. J. Biochem. 278: 33408–33415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]