Abstract

The effect of glycosylation on AFP foldability was investigated by parallel quantitative and qualitative analyses of the refolding of glycosylated and nonglycosylated AFP variants. Both variants were successfully refolded by dialysis from the denatured-reduced state, attaining comparable “refolded peak” profiles and refolding yields as determined by reversed-phase HPLC analysis. Both refolded variants also showed comparable spectroscopic fingerprints to each other and to their native counterparts, as determined by circular dichroism spectroscopy. Inclusion body-derived AFP was also readily refolded via dilution under the same redox conditions as dialysis refolding, showing comparable circular dichroism fingerprints as native nonglycosylated AFP. Quantitative analyses of inclusion body-derived AFP showed sensitivity of AFP aggregation to proteinaceous and nonproteinaceous inclusion body contaminants, where refolding yields increased with increasing AFP purity. All of the refolded AFP variants showed positive responses in ELISA that corresponded with the attainment of a bioactive conformation. Contrary to previous reports that the denaturation of cord serum AFP is an irreversible process, these results clearly show the reversibility of AFP denaturation when refolded under a redox-controlled environment, which promotes correct oxidative disulfide shuffling. The successful refolding of inclusion body-derived AFP suggests that fatty acid binding may not be required for the attainment of a rigid AFP tertiary structure, contrary to earlier studies. The overall results from this work demonstrate that foldability of the AFP molecule from its denatured-reduced state is independent of its starting source, the presence or absence of glycosylation and fatty acids, and the refolding method used (dialysis or dilution).

Keywords: α-fetoprotein, protein, refolding, renaturation, oxidative, glycosylation

α-Fetoprotein (AFP) is a promising biopharmaceutical drug, and a recombinant version of human AFP (rhAFP) is being evaluated in human clinical studies for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. This potential clinical utility is producing a demand for efficient processes for the manufacture of biologically active AFP. Escherichia coli, which is an FDA-approved host, is an attractive choice for the high-yield production of therapeutics due to its well-established genetic characteristics and high recombinant expression levels (Schuler and Kargi 1992).

Inclusion body-derived proteins are unglycosylated due to the inability of E. coli to glycosylate proteins. For eukaryotic proteins, glycosylation has been documented to be involved in biorecognition, stabilization, and control of protein conformation (Elbein 1991), as well as to function as a folding aid (West 1986; Kwon and Yu 1997). The reported role of glycosylation has been variable for E. coli–derived proteins; glycosylation was reported not to be essential for the in vitro refolding and activity for several E. coli–derived proteins, but it increased the active protein yields of others (Levine et al. 1998; Pattanaik et al. 1998). In the case of AFP, glycosylation has been linked to catabolism (Janzen and Tamaoki 1983) and the regulation of fatty acid movement and conformational structure (Gillespie and Uversky 2000), although these hypotheses are yet to be experimentally validated. In another study, the absence of glycosylation was reported to not have any effect on the serum half-life pharmacokinetics and cell-binding activity of the AFP molecule (Parker et al. 2004).

Previous studies also discussed the dependence of the AFP molecule on fatty acid binding for the attainment of a rigid tertiary structure (Uversky et al. 1997; Gillespie and Uversky 2000). Human fetal-derived AFP has three fatty acid–binding sites, with high affinity particularly for arachidonic and docosahexaenoic acid (Parmelee et al. 1978; Berde et al. 1979; Carlsson et al. 1980; Hsia et al. 1980). The function of fatty acid binding by AFP is still not fully understood and remains an active field of research, although it has been suggested that it could have a role in mediating fatty acid uptake by human T lymphocytes (Torres et al. 1992). Studies by Uversky et al. (1997) and Gillespie and Uversky (2000) suggested that denaturation of cord serum–derived AFP was accompanied by an irreversible transformation of the protein molecule to the fatty acid–free form. The unfolded molecules, stripped of fatty acids, showed characteristics of a molten globule state, which lacks a unique tertiary structure, as determined by fluorescence and near-UV CD spectroscopy and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) measurements. The irreversibility of AFP denaturation (by decrease in pH, increase in temperature, with urea or guanidine HCl), was inferred by the failure of the AFP molecule to return to its original tertiary conformation, when denaturation conditions were reversed to enable refolding. Refolding of denatured AFP, as reported by these studies, was conducted only by reversal of denaturation conditions; the use of refolding additives or redox couples was not reported. Interestingly, resaturation of the denatured, ligand-free AFP with fatty acid to allow fatty acid rebinding also reportedly failed to revert the molecule back to its native tertiary structure, leading to the conclusion that denatured AFP molecule could not rebind fatty acids to allow refolding of the molecule to its native state (Uversky et al. 1997). The investigators further hypothesized the possibility of a coupling effect between glycosylation and the irreversibility of ligand release during AFP denaturation, where the glycosylation chain was suggested to have a role in screening the ligand-binding pocket of the AFP molecule during folding—this has not been experimentally verified to date. This assertion on the irreversibility of AFP denaturation conflicts with the results of a separate study that reported the successful refolding of E. coli–derived AFP that showed the same immunosuppressive properties as human fetus-derived AFP (Semeniuk et al. 1995; Boismenu et al. 1997), suggesting that neither glycosylation nor bound ligands are required for this biological activity.

These conflicting reports suggest that AFP refolding is still poorly understood at a molecular level and highlight the need for a separate and parallel study to independently verify the roles of glycosylation and ligand binding on AFP conformational structure and foldability. Therefore, one of the aims of this study is to compare, in parallel, the effect of glycosylation on AFP foldability and the reattainment of native structure. Since the reattainment of a native structure from the denatured state depends on correct refolding, studying AFP foldability with respect to glycosylation would provide a good indication of whether glycosylation is truly essential for the formation of native AFP. In this study, cord serum-derived human AFP and a recombinant version of human AFP derived from the milk of transgenic goats (Parker et al. 2004) will be used to represent glycosylated and nonglycosylated AFP variants, respectively. E. coli–derived AFP, expressed as inclusion bodies, will be used to represent the AFP variant without bound ligands. Although direct confirmation of ligand binding was not determined in this study, this assumption is reasonable considering that E. coli will have a very different fatty acid spectrum to mammalian cells (Cronan and Rock 1987; Magnuson et al. 1993) and that inclusion body proteins are inherently denatured and thus unable to bind ligands.

The outcome of this work conclusively demonstrates that glycosylation is not required for AFP refolding and for the attainment of a conformational structure comparable to the native protein. Reversibility of AFP denaturation was observed in all three AFP variants investigated including inclusion body-derived AFP. AFP refolding yields decreased with decreasing AFP purity, where both proteinaceous and nonproteinaceous contaminants remaining from inclusion body preparations were found to negatively impact AFP-refolding yields.

Results and Discussion

Effects of glycosylation on AFP foldability and structure

Two AFP variants, glycosylated cord blood–derived AFP (gAFP) and nonglycosylated recombinant AFP purified from transgenic goat milk (M-AFP), were studied in parallel to investigate the role of glycosylation on AFP foldability and conformational structure. Bioanalyzer analyses comparing gAFP and M-AFP showed that the molecular size of gAFP was larger by 4 kDa compared with M-AFP (Fig. 1), presumably due to the presence of a glycosylation site in the former. Human AFP has a single glycosylation site, which contributes to ∼3 kDa of its molecular mass (Morinaga et al. 1983).

Figure 1.

Comparison of molecular sizes between gAFP and M-AFP. (Lane 1) Molecular weight marker, (lane 2) denatured gAFP, (lane 3) denatured M-AFP.

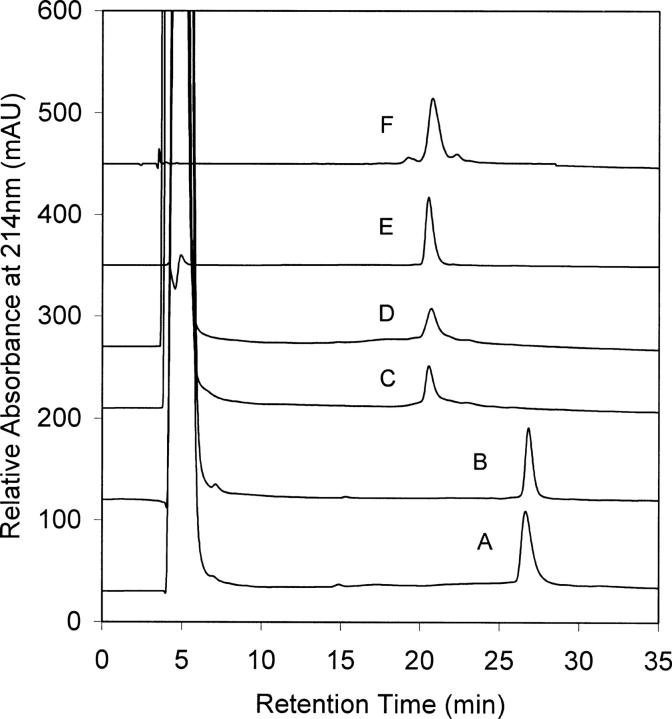

gAFP and M-AFP were denatured-reduced and refolded in parallel by dialysis (see “Preparation of denatured-reduced gAFP and M-AFP” and “Dialysis refolding of gAFP and M-AFP”). RP-HPLC analyses of the 24-h refolded AFP variants showed that both refolded materials eluted from the RP column at the same retention time (i.e., 21 ± 0.5 min) (Fig. 2). This result indicates that both AFP variants had refolded to give comparable disulfide-bonding patterns and hydrophobic characteristics. The sensitivity of RP-HPLC retention time to glycosylation has been variable; some glycosylated polypeptides showed a decrease in RP retention time (Otvos et al. 1992), while others maintained similar retention time to their nonglycosylated counterparts (Nacka et al. 1998; Kim et al. 2005). The effect of glycosylation on RP retention time is likely to vary with the length of the glycosylation chain, which presumably alters protein hydrophobicity and conformational orientation to different extents. Figure 2 shows that there was no significant shift in RP retention time between gAFP and M-AFP (in both native and refolded conformations) under an RP-HPLC gradient of 0.9% (v/v) acetonitrile/min (see “Analytical methods”). This could be because the single glycosylation site in human AFP, which constitutes only ∼4% of the molecular weight of the polypeptide (Morinaga et al. 1983), may not have a significant impact on the hydrophobicity or disulfide conformation of the molecule. Refolding yields of both materials after 24 h were also comparable (i.e., 25% and 29% ± 2% for gAFP and M-AFP, respectively).

Figure 2.

RP-HPLC profiles showing the refolding of gAFP and M-AFP from their denatured-reduced state. (A) Denatured-reduced M-AFP, (B) denatured-reduced gAFP, (C) refolded A after 24-h dialysis refolding, (D) refolded B after 24-h dialysis refolding, (E) native M-AFP (as received), (F) native gAFP (as received).

The far- and near-UV CD spectra of refolded AFP variants were compared against their native and denatured counterparts (Figs. 3 and 4 for gAFP and M-AFP, respectively). It is clear that both glycosylated and nonglycosylated variants showed comparable spectra to their native counterparts. Importantly, both refolded gAFP and M-AFP showed far and near UV CD fingerprint bands that were similar to each other (Fig. 5), and comparable to those shown by Parker et al. (2004). This suggests that glycosylation is not required for AFP refolding and for the attainment of a tertiary structure comparable to native AFP. This result complements the conclusions of an earlier study that native M-AFP showed identical pharmacokinetics and cell-binding activity to human cord blood-derived AFP (Parker et al. 2004).

Figure 3.

Spectroscopic analysis of denatured, refolded, and native gAFP. (A) Far-UV CD spectra of denatured, refolded, and native gAFP. (B) Near-UV CD spectra of denatured, refolded, and native gAFP.

Figure 5.

Comparison of far and near UV spectra of refolded gAFP and M-AFP. (A) Far UV CD spectra of refolded gAFP and M-AFP. (B) Near UV spectra of refolded gAFP and M-AFP; (i) ligand-free cord serum AFP, (ii) cord serum AFP having bound ligands. Both i and ii were replotted from Figure 2B of Gillespie and Uversky (2000), with permission of Elsevier.

The reversibility in AFP denaturation as demonstrated in this work contradicts the results reported by Uversky et al. (1997) and Gillespie and Uversky (2000) that the denaturation of human cord serum–derived AFP molecule is irreversible. Glycosylation was assumed to be partly responsible for the observed irreversibility in those studies. In contrast, we have shown that both completely denatured-reduced gAFP and M-AFP could be readily refolded to regain a native AFP structure under a redox-controlled refolding environment. Reasons for the discrepancy in findings between this study and those reported by Uversky et al. (1997) and Gillespie and Uversky (2000) are unclear, although it must be noted that the way in which refolding was conducted in both studies was different. In our present study, denatured-reduced AFP was dialyzed against refolding buffer containing redox agents to facilitate oxidative disulfide shuffling of the protein (see “Dialysis refolding”) and analyzed for foldability after 24 h (see “Analytical methods”). In the work reported by Uversky et al. (1997), refolding was conducted by reversing the denaturation conditions (either by cooling the heat-denatured protein or by diluting the 9.5-M urea-denatured protein into a non-redox-containing refolding buffer to urea concentrations between 0.1 and 0.2 M). A question that remains is whether reversing the denaturation conditions is sufficient to promote correct refolding of the AFP molecule. Redox optimization is clearly important to facilitate optimal disulfide shuffling, as evident in many oxidative protein-refolding studies. For example, a distinct optimum concentration of GSH and GSSG has been required to support the optimal oxidative refolding rates of various disulfide-bonded proteins such as lysozyme (Saxena and Wetlaufer 1970) and Ribonuclease A (Lyles and Gilbert 1991). An overly reducing redox environment can inhibit disulfide-bond formation in the refolding intermediates, while a high GSSG concentration can promote the formation of nonproductive mixed disulfides (Konishi et al. 1982). Nevertheless, what is evident from this study is that completely denatured-reduced AFP can be readily refolded into its native structure, irrespective of glycosylation, when refolding occurs in a redox-controlled environment that allows the correct disulfide pattern to be attained.

The loss of a unique tertiary structure upon “refolding” as reported in previous work (Uversky et al. 1997; Gillespie and Uversky 2000) was reportedly due to the irreversible loss of fatty acid, a natural ligand of AFP, during denaturation. Coincubation of denatured AFP with fatty acids to allow rebinding of the fatty acids also failed to promote correct re-formation of the rigid native tertiary conformation (Uversky et al. 1997). Although fatty acid release was not directly measured during the denaturation of both gAFP and M-AFP in this study, we expect that the denaturation condition used in this work (see “Preparation of denatured-reduced pure protein”) was sufficient for the complete unfolding of the AFP molecule (as determined by RP-HPLC analyses) and thus release of any hydrophobic ligands. In fact, both the far- and near-UV CD spectra of denatured AFP obtained in this study (Figs. 3, 4), were comparable to those reported by Uversky et al. (1997), where fatty acid release was confirmed by gas chromatography in their work. It must be noted, however, that the near-UV CD spectra of denatured-reduced AFP obtained in this work Figs. (3B, 4B) showed slightly less spectral intensity, compared with those shown by Uversky et al. (1997) and Gillespie and Uversky (2000) for unfolded AFP. We attribute the simplification in spectra of denatured-reduced AFP in our study to the addition of DTT, which reduced disulfide bonds during protein denaturation. Addition of reducing agents, however, was not reported during the protein-unfolding step by Uversky et al. (1997) and Gillespie and Uversky (2000). Thus, it is likely that the slightly more pronounced overall tertiary structure shown in the work of Uversky et al. (1997) and Gillespie and Uversky (2000) were contributed by the remaining disulfide bonds of the denatured AFP molecule. This is not unexpected considering CD spectra in the near-UV region (250–300 nm) originate from aromatic amino acid residues and disulfide bonds to provide a unique fingerprint of the tertiary conformation of the protein (Strickland 1974; Woody 1994).

Figure 4.

Spectroscopic analysis of denatured, refolded, and native M-AFP. (A) Far-UV CD spectra of denatured, refolded, and native M-AFP. (B) Near-UV CD spectra of denatured, refolded, and native M-AFP.

From the near-UV CD spectra comparing refolded gAFP and M-AFP (Fig. 5B), it is also clear that both refolded AFP variants did not show any characteristics of a molten globule state lacking a rigid tertiary structure as observed by Gillespie and Uversky (2000) for cord serum–derived AFP without bound ligands. Importantly, refolded gAFP and M-AFP gave positive responses in a sandwich ELISA test, comparable with their native counterparts, while heat-denatured M-AFP controls (with and without addition of 20 mM DTT to reduce disulfide bonds) yielded negative responses (data not shown).

Dialysis vs. dilution refolding

Low AFP-refolding yields during dialysis have been found to be due to significant loss of correctly folded protein to aggregation and nonspecific adsorption on the dialysis membrane (Leong and Middelberg 2006). Also, although dialysis refolding allows good control of the chemical environment for refolding, it is a slow and highly buffer-consuming process, thus uneconomical for production of therapeutic candidates such as AFP. Having determined a redox environment that promoted renaturation of AFP by dialysis, we next investigated the use of dilution refolding for AFP refolding to minimize aggregation. Dilution refolding was considered an appropriate choice because it is simple and easily automated, thus minimizing manufacturing complexity, and is reasonably economic (Clark 1998; Middelberg 2002). When denatured-reduced M-AFP was refolded in parallel using dilution and dialysis (i.e., under identical redox conditions, at an AFP refolding concentration of 25 μg/mL), a higher M-AFP-refolding yield of 64% was achieved in dilution refolding compared with 29% during dialysis, after 24 h refolding. The increased yield in dilution refolding was attributed to the removal of the protein-adsorbing dialysis membrane during dilution refolding. Compared with dialysis, dilution refolding is also expected to impose a more rapid change in chemical environment from denaturing to native-favoring, thus reducing protein exposure time to suboptimal refolding environments that could increase potential for aggregation.

Refolding of E. coli–derived AFP and the effects of inclusion body contaminants

This part of the study investigates the refolding of E. coli–derived AFP (rhAFP), which has an identical amino acid sequence to M-AFP (see “Cloning and expression of AFP in E. coli”). Following extraction of the rhAFP inclusion bodies and their purification using Q-Sepharose chromatography (see “Extraction, purification, and solubilization of rhAFP”), the partially purified rhAFP fractions eluted from the first Q-Sepharose purification step were pooled, yielding 40% rhAFP purity as determined by Bioanalyzer analysis, and used for subsequent refolding studies.

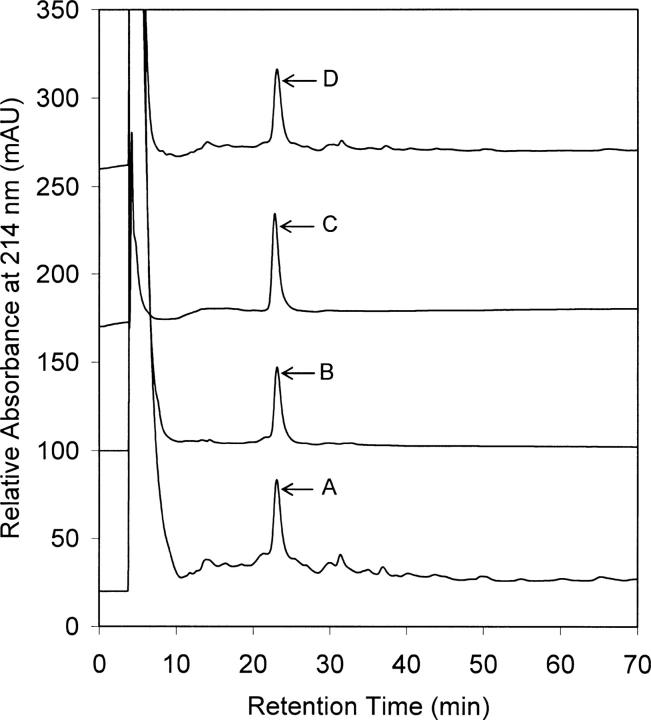

Q-Sepharose-purified rhAFP at 40% purity and M-AFP were dilution-refolded in parallel at different AFP concentrations. Both the refolded AFP variants yielded similar RP-HPLC profiles (Fig. 6) and comparable secondary and tertiary conformations to native M-AFP (Fig. 7). This result shows that reversibility of AFP denaturation leading to successful refolding could also be readily extended to inclusion body-derived rhAFP, which is unlikely to have bound fatty acids. Binding of host-derived fatty acids to the AFP molecule upon refolding is unlikely, considering that the buffer exchange step used to remove DTT prior to refolding (see “Dilution refolding”) would also have allowed separation of fatty acids, having the molecular mass of the same order of magnitude as DTT, from rhAFP. The outcome of this work conclusively shows that AFP denaturation is reversible regardless of the refolding method, AFP starting source, and purity.

Figure 6.

RP-HPLC profiles comparing refolded rhAFP and M-AFP. (A) Dilution refolded rhAFP; (B) dilution refolded M-AFP (2X diluted for HPLC analysis); (C) native M-AFP, 20-μL injected; (D) simultaneous injections of A and C at 50:50 (v/v).

Figure 7.

Spectroscopic analysis of refolded and purified rhAFP and native M-AFP. (A) Far-UV CD spectra of refolded-purified rhAFP and native M-AFP. (B) Near-UV CD spectra of refolded-purified rhAFP and native M-AFP.

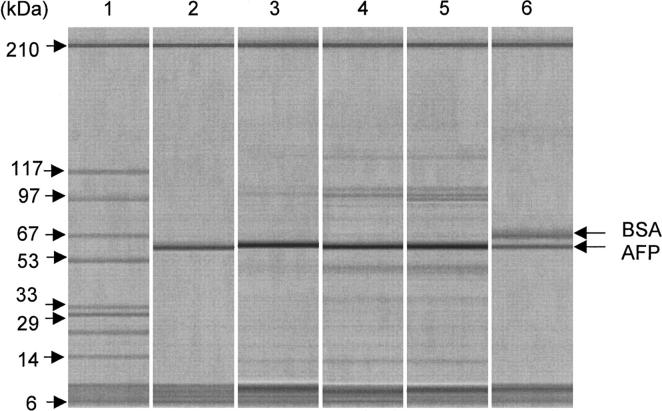

Q-Sepharose-purified rhAFP at 40% purity, however, showed a lower refolding yield than M-AFP at all AFP-refolding concentrations investigated (Fig. 8). Inclusion body contaminants have been reported to negatively impact refolding yields for some proteins by increasing aggregation during refolding (Shire et al. 1984; Maachupalli-Reddy et al. 1997). To test whether the discrepancy in refolding yields between Q-Sepharose-purified rhAFP of 40% purity and M-AFP was related to the aggregative effects caused by contaminants, AFP solutions of different purities were prepared (Fig. 9; see “Contaminant spike test”) and refolded in parallel at a fixed AFP concentration of 25 ± 2 μg/mL. AFP-refolding yields were found to decrease with decreasing AFP purity (Table 1), confirming that increased inclusion body contaminants increased protein aggregation during rhAFP refolding. A similar sensitivity of lysozyme refolding to contaminants was observed by Maachupalli-Reddy et al. (1997), where a reduction in refolding yield was observed upon addition of inclusion body impurities.

Figure 8.

Refolding yields of rhAFP and M-AFP at different rhAFP refolding concentrations.

Figure 9.

Different AFP purities for the study of contaminant effects on AFP refolding yields. (Lane 1) Molecular weight marker, (lane 2) denatured M-AFP (purity >99.9%), (lane 3) denatured AFP at 86% purity, (lane 4) denatured AFP at 58% purity, (lane 5) denatured rhAFP at 40% purity, (lane 6) denatured M-AFP spiked with denatured BSA to give 40% M-AFP purity.

Table 1.

Actual AFP purities and concentrations as determined by Bioanalyzer and RP-HPLC analyses, respectively, for the investigation of contaminant effects on AFP-refolding yields.

To investigate the contribution of proteinaceous contaminants to AFP aggregation, denatured M-AFP was spiked with denatured BSA, a proteinaceous contaminant that aggregates upon folding (Maachupalli-Reddy et al. 1997; Li et al. 2001), to a final M-AFP purity of 42%, and the mixture refolded at M-AFP concentration of 26 μg/mL. An M-AFP refolding yield of 50% was obtained, which lies between the refolding yields of 41% and 70% obtained in the refolding of Q-Sepharose-purified rhAFP (40% purity) and M-AFP, respectively (Table 1). This result indicates that both proteinaceous and nonproteinaceous contaminants contribute toward protein aggregation during the refolding of rhAFP. This is not unexpected, considering that the AFP molecule binds easily to hydrophobic contaminants, particularly in its native state (Parmelee et al. 1978; Hsia et al. 1980). The reason for this behavior has not been clearly established, although it is plausible that the fatty acid–binding domain of the AFP molecule is responsible. The outcome of this work points toward the importance of attaining sufficiently pure protein prior to refolding to maximize rhAFP refolding yields.

Determination of rhAFP refolding yields by RP-HPLC and ELISA

Figure 10 compares the refolding yields of different refolded AFP variants using RP-HPLC and ELISA. This discrepancy in refolding yields between RP-HPLC and ELISA is not unexpected, due to the relatively larger errors normally incurred by biological quantitative methods such as ELISA. Importantly, all refolded AFP variants gave a positive response in the sandwich ELISA test, with controls consisting of heat-denatured rhAFP, with and without addition of 20 mM DTT to reduce disulfide bonds, yielding negative responses (data not shown). This result confirms that all refolded AFP variants maintained a molecular conformation comparable to human AFP standards provided by the ELISA kit (see “Analytical methods”).

Figure 10.

Refolding yields of different refolded AFP variants, as quantified by RP-HPLC and ELISA. (A) Dialysis-refolded gAFP, (B) dialysis-refolded M-AFP, (C) dilution-refolded M-AFP, (D) dilution-refolded rhAFP (40% purity).

Conclusions

Quantitative and qualitative parallel comparisons between foldability of gAFP and M-AFP clearly showed that glycosylation was not required for the in vitro refolding of this important therapeutic protein. Contrary to previous studies that discuss the irreversibility of AFP denaturation, the results from this work demonstrate the reversibility of AFP denaturation to refold into a rigid conformation comparable to its native counterpart in a redox-controlled refolding environment. The formation of this rigid, native-like structure was readily achievable irrespective of the refolding method (i.e., dilution or dialysis). Refolding success was also confirmed by ELISA, where all refolded variants demonstrated the presentation of epitopes found in native human AFP. The successful renaturation of inclusion body-derived rhAFP reported in this work raises the controversial question of whether ligand binding is truly essential for the attainment of a rigid tertiary conformation for the AFP molecule. Increased aggregation with decreasing rhAFP purity was attributed to both proteinaceous and nonproteinaceous inclusion body contaminants, thus emphasizing the importance of sufficient purification prior to refolding. The results from this work open the way for optimized rhAFP manufacture using E. coli, where it is shown that (1) glycosylation is not required for rhAFP refolding and (2) process yields can be maximixed by controlling contaminant carryover prior to refolding.

Materials and methods

In this study, three different AFP variants were investigated: (1) AFP derived from human cord fetal serum (gAFP), (2) a recombinant version of human AFP derived from transgenic goats (M-AFP), and (3) a recombinant human AFP derived from E. coli (rhAFP).

gAFP was purchased in a lyophilized form (purity >98%) from HyTest Ltd. gAFP is glycosylated and contains bound fatty acids (catalog no. 8F8, HyTest). The protein was reconstituted in distilled H2O to a final protein concentration of 2.5 mg/mL, giving a buffer composition of 20 mM phosphate, 150 mM NaCl (pH 7.3).

M-AFP is a nonglycosylated recombinant version of human AFP, which was purified from the milk of transgenic goats (Parker et al. 2004). This material was kindly provided by Merrimack Pharmaceuticals in a purified form (purity >99.9%), solubilized in 10 mM sodium phosphate, 150 mM NaCl (pH 7.2) at a stock protein concentration of 10.6 mg/mL.

rhAFP was expressed recombinantly in E. coli. Plasmid EP334-001 pET24D 3.1A expressing AFP was kindly provided by Merrimack Pharmaceuticals. This plasmid directs the synthesis of AFP having an amino acid sequence that lacks an N-terminal arginine residue but is otherwise identical to that of M-AFP. The AFP sequence contained in this plasmid starts with an N-terminal threonine (Thr) and thus contains one amino acid less than M-AFP, which starts with an N-terminal arginine, followed by threonine as its second amino acid residue. For direct comparison studies between M-AFP and E. coli–derived AFP, the N-terminal arginine residue was restored to the sequence contained in plasmid EP334-001 pET24D 3.1A.

Upstream primer 5′−TCTAGAATAATTTTGTTTAACTTTAAGAAGGAGATATACCATGAGAACACTGCATAGAAATG-3′, having an XbaI site, and downstream primer 5′−CTCGAGTTAAACTCCCAAAGCAGC-3′, having an XhoI site, were used to introduce an additional arginine residue to the N terminus of AFP during PCR amplification from the as-received plasmid. The cloned Thr-AFP in the as-received plasmid was excised using XbaI and XhoI and then religated with XbaI- and XhoI-treated PCR-amplified product before transformation into E. coli JM109 for selection. Transformed cells were plated on an LB agar plate containing 50 μg/mL kanamycin and incubated overnight at 37°C. A single colony of the transformed cells was picked and used to inoculate a 5-mL LB (Luria broth) medium, supplemented with 50 μg/mL kanamycin and incubated overnight at 37°C. The success of plasmid transformation was confirmed by restriction endonuclease digestion and verified by DNA sequencing conducted by the Institute of Molecular Bioscience, University of Queensland. DNA alignment of the newly transformed plasmid was performed and compared against those of as-received plasmid EP334-001 pET24D 3.1A and M-AFP. DNA extraction was conducted using PureLink Quick Miniprep kit (Invitrogen) following the procedure provided by the manufacturer. The plasmid DNA of the positive clone that had been sequenced to confirm the addition of an arginine residue to the Merrimack AFP sequence was then transformed into E. coli BL21 DE3 RIL (Stratagene) for expression. This newly E. coli–derived AFP variant will be referred to as “rhAFP” in this study.

For rhAFP expression, an aliquot of the glycerol stock containing the E. coli cells was plated on an LB agar plate containing 50 μg/mL kanamycin and incubated overnight at 37°C. A single colony was picked and used to inoculate a 5-mL 2YT medium containing 50 μg/mL kanamycin (11815-032, GIBCO). This 5-mL culture was mixed by agitation for 18–20 h using a horizontal shaker set at 180 rpm and 37°C, and subsequently used to inoculate a 2-L baffled Erlenmeyer flask containing 500 mL 2YT medium supplemented with fresh kanamycin to 50 μg/mL. This 500-mL culture was incubated in a horizontal shaker at 180 rpm and 37°C. When the OD, measured at 600 nm (OD600) using a spectrophotometer (UV-2450 UV-Visible Spectrophotometer, Shimadzu), reached 1.0 ± 0.1, the 500-mL culture was induced with IPTG (AST0487-1, Astral) to a final concentration of 0.4 mM. Expression was terminated after 1 h of induction when OD600 was 1.8–2. The culture was centrifuged (2000g, 4°C, 20 min). Cell pellets were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (2 mM KCl, 137 mM NaCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4 at pH 7.2) and centrifuged as above. The washed cell pellet was stored at −20°C and thawed on ice before use.

Extraction, purification, and solubilization of rhAFP

Protein extraction was conducted using the B-PER Bacterial Protein Extraction Reagent (78,243, Pierce). Following addition of 20 mL of B-PER to a thawed 500-mL cell pellet (OD600 = 1.8), the suspension was mixed by pipetting and incubated for 5 min. The soluble and insoluble protein fractions were separated by centrifugation at 10,000g for 15 min. The pellet was resuspended again with 20 mL of B-PER reagent, and lysozyme was added to a final concentration of 0.2 mg/mL to further digest cell debris and release the inclusion bodies. This suspension was centrifuged at 10,000g for 30 min, followed by another cycle of resuspension in the B-PER reagent and centrifugation for further inclusion body purification. The pellet was subsequently washed (200 mL of 20 mM Tris, 3 mM EDTA, 10 mM DTT at pH 8.5), and then centrifuged (10000g, 30 min). This chemical-wash centrifugation cycle was conducted twice. The final washed pellet was solubilized and denatured in 50 mL of denaturation buffer (8 M urea, 20 mM Tris, 3 mM EDTA, 20 mM DTT at pH 8.5) for 2 h by pipetting and gentle shaking at room temperature. Polyethyleneimine (PEI) (P-3143, Sigma) was added to a final concentration of 0.10% (w/v) to selectively precipitate DNA contaminants. The mixture was incubated for 30 min and centrifuged (10,000g, 4°C, 10 min).

Supernatant pH was adjusted to 6.5 using 0.1 M HCl and directly loaded onto a 5-mL HiTrap Q-Sepharose column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in Buffer A (8 M urea, 20 mM Tris, 3 mM EDTA, 10 mM DTT at pH 6.5). Elution was achieved by a step increase to 4.5% (v/v) Buffer B (8 M urea, 20 mM Tris, 3 mM EDTA, 10 mM DTT, 0.6 M NaCl at pH 6.5, 3CV) and then 100% (v/v) B (3 CV each). Flowrate was 0.5 mL/min throughout. Eluted rhAFP fractions from the 4.5% (v/v) Buffer B elution step were pooled and used for subsequent refolding studies.

Prior to circular dichroism analysis (see “Analytical methods”), the refolded rhAFP mixture (see “Dilution refolding”) was purified on a 1-mL HiTrap Q-Sepharose column (GE Healthcare), equilibrated in Buffer C (20 mM Tris, 3 mM EDTA at pH 8.5). Elution was conducted with Buffer D (20 mM Tris, 3 mM EDTA, 0.6 M NaCl at pH 8.5) using three-step changes (20% [v/v], 80% [v/v], and 100% [v/v] D, 5 CV each). Flow rate was 0.6 mL/min throughout. Eluted purified rhAFP fractions were dialyzed against buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate at pH 7.4) for circular dichroism analysis.

All process chromatography experiments were performed on an ÄKTAexplorer workstation (GE Healthcare) at room temperature, 23 ± 2°C.

Preparation of denatured-reduced gAFP and M-AFP

For preparation of denatured-reduced gAFP or M-AFP for dialysis refolding, the native protein was diluted in denaturation buffer to a final protein concentration of 25 μg/mL. For denaturation of M-AFP for dilution refolding, the native protein at 10.6 mg/mL was diluted in buffer (8.6 M urea, 20 mM Tris, 3 mM EDTA, 20 mM DTT at pH 8.5) to obtain a final protein concentration of 0.75 mg/mL prior to a buffer-exchange step to remove DTT (see “Dilution refolding”). A higher urea concentration than that used in denaturation buffer was required in order to maintain the urea concentration at 8 M after dilution. Protein was incubated under denaturing-reducing conditions for 2 h at room temperature and subsequently RP-HPLC analyzed to confirm its concentration and homogeneity and to ensure a homogeneous denatured-reduced starting material.

Dialysis refolding of gAFP and M-AFP

Denatured-reduced gAFP or M-AFP (3 mL at 25 μg/mL) was loaded into a 0.5- to 3-mL dialysis cassette (66,425, Pierce) having a membrane molecular weight cutoff of 10 kDa, and then dialyzed against 500 mL refolding buffer (20 mM Tris, 3 mM EDTA, 0.5 M L-Arginine, 0.8 M urea, 1.33 mM GSH, and 1.33 mM GSSG at pH 8.5) under stirring conditions at 4°C. DTT was not preremoved in the dialysis refolding step, as DTT would be diluted to negligible levels by the bulk-refolding solution. The 100-μL aliquots of refolded gAFP or M-AFP mixture from the dialysis cassette were RP-HPLC analyzed after 24 h (see “Analytical methods”).

Dilution refolding

DTT was first removed from the protein mixture using a 5-mL HiTrap desalting column that utilizes a Sephadex G-25 superfine matrix (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in denaturing buffer lacking DTT. This step caused an approximate threefold dilution of the protein mixture when a 500-μL sample load was used and a 1-mL elution fraction collected. Actual protein concentration following buffer exchange was determined by RP-HPLC (see “Analytical methods”). The buffer-exchanged denatured protein mixture was rapidly diluted 10-fold into refolding buffer (20 mM Tris, 3 mM EDTA, 0.5 M L-Arginine, 1.33 mM GSH, and 1.33 mM GSSG at pH 8.5) in a single step. The final refolding buffer composition was 20 mM Tris, 3 mM EDTA, 0.5 M L-Arginine, 0.8 M urea, 1.33 mM GSH, and 1.33 mM GSSG (pH 8.5). The protein was incubated in the refolding buffer at 4°C for 24 h. The 100-μL aliquots of samples were subsequently RP-HPLC analyzed to determine the yield of correctly folded protein.

Contaminant spike test

To determine the effects of inclusion body contaminants on rhAFP refolding yields, Q-Sepharose-purified rhAFP (see “Extraction, purification, and solubilization of rhAFP”) was added to denatured M-AFP solutions at different volume ratios to yield final AFP purities of 40%, 55%, 85%, and 100% prior to DTT removal and refolding. Actual AFP purities were directly determined by Bioanalyzer (Agilent) analysis (Table 1). To investigate the effect of proteinaceous contaminants on AFP refolding, denatured BSA (purity >99%) (775,827, Roche) was added to denatured M-AFP to achieve a nominal M-AFP purity of 42%. All refolding tests were conducted at a final AFP concentration of 25 ± 2 μg/mL.

Analytical methods

The concentrations of native, denatured, and refolded AFP variants were analyzed using a C5 Jupiter reversed-phase (RP) column (5 μm, 300 Å, 150 × 4.6 mm; Phenomenex) on a Shimadzu LC-10AVP high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system. All HPLC buffers contained 0.05% (v/v) TFA counterion. Solvent delivery and gradient formation were achieved using a Shimadzu LC-10AVP solvent delivery module. The RP-column was first subjected to an isocratic 40% (v/v) acetonitrile-water gradient for 9.5 min, followed by a 36%–61% (v/v) acetonitrile-water gradient over 28 min. For analysis of rhAFP, a shallower acetonitrile gradient of 0.2% (v/v) acetonitrile-water /min (i.e., 48%–60% [v/v] acetonitrile-water gradient over 60 min) was used to allow better peak resolution where more protein contaminants were present. The same latter gradient was used for parallel analysis of M-AFP for direct comparison with rhAFP. Total solvent flow rate of 0.5 mL/min was used for all RP-HPLC analyses. Absorbance was measured at 214 nm using a UV detector (Shimadzu SPD-10AVP). Samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 8000g prior to analysis. A 100-μL sample was injected per RP-HPLC analysis, except where noted otherwise. Data acquisition and processing were conducted using the Class-VP 7.2.1 software (Shimadzu).

AFP-refolding yield was quantified as the mass ratio of final refolded AFP to initial denatured AFP. Mass of protein eluted from the RP column was quantitatively determined by peak integration based on a standard curve obtained by calibration using native and denatured M-AFP of known concentration. To accurately determine the amount of correctly refolded protein, any peak tailings appearing in the UV traces that were not present in RP-HPLC traces of native M-AFP were excluded from peak integration.

Total protein concentration and AFP purity were determined using a chip-based separation technique, performed on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent) in combination with the Protein 200 Plus LabChip kit. Absolute AFP quantitation was enabled by the generation of a calibration curve using M-AFP. Chips were prepared according to the protocol provided with the Protein 200 Plus LabChip kit. A 4-μL sample was injected per well for analysis.

Far- and near-UV CD spectra of denatured, native, and refolded AFP variants were obtained using a Jasco-810 spectrapolarimeter (Jasco Corp.). Cell pathlengths were 1 and 10 mm for far- and near-UV CD measurements, respectively. Protein concentrations were 0.1–0.2 and 0.5–0.8 mg/mL for far- and near-UV spectra measurements, respectively, as quantified by RP-HPLC. Protein samples (250 and 350 μL, respectively) were used for far- and near-UV measurements. Spectra were corrected by subtracting the buffer baseline, and were averaged over 10 scans for all measurements, using 1-nm intervals, a response time of 2 sec, and a 1-nm bandwidth. Native and refolded protein samples were solubilized in 10 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.4). Denatured AFP variants for CD measurements were prepared by denaturing and reducing the protein in 8 M urea, 0.1 M DTT for 2 h at room temperature. DTT was subsequently removed using a 5-mL HiTrap Desalting column, as DTT absorbs in the region of the spectrum used. All measurements were at room temperature, 23 ± 2°C.

The correct presentation of epitopes of refolded AFP variants was demonstrated by the AFP ELISA diagnostic kit (T176, Leinco Technologies), which uses goat polyclonal and mouse monoclonal antibodies directed against distinct antigenic determinants on the recombinant human AFP molecule. Then, 20 μL of refolded AFP diluted with bovine serum to concentrations ranging from 10 to 350 ng/mL were added to the wells, precoated with murine monoclonal anti-AFP, and incubated for 5 min. Goat polyclonal anti-AFP horseradish peroxidase conjugate (200 μL) was then added to each well and incubated for 60 min, and the wells were subsequently washed to remove unbound labeled antibody. A total of 100 μL of enzyme substrate-chromogen (hydrogen peroxide, H2O2, and tetramethylbenzidine, TMB) was added to each well and incubated for 30 min at room temperature; 1.0 N H2SO4 was then added to stop the reaction and product concentration was read at 450 nm using a microplate spectrophotometer (PowerWave XS, Bio-Tek Instruments). Refolded AFP concentrations were determined from a calibration curve ranging from 0 to 350 ng/mL native human AFP calibrators (provided with the kit).

Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Linda Lua (SRC Protein Expression Facility, Institute of Molecular Bioscience, University of Queensland) for conducting the rhAFP cloning work reported in this study.

Footnotes

Reprint requests to: Susanna S.J. Leong, Department of Chemical Engineering, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK; e-mail: ssjl2@cam.ac.uk; fax: +61-7-33468783.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.062262406.

References

- Berde C.B., Nagai M., Deutsch H.F. 1979. Human α-fetoprotein: Fluorescence studies on binding and proximity relationships for fatty acids and bilirubin. J. Biol. Chem. 254: 12609–12614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boismenu R., Semeniuk D., Murgita R.A. 1997. Purification and characterization of human and mouse recombinant α-fetoproteins expressed in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr. Purif. 10: 10–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson R.N.K., Estes T., Degroot J., Holden J.T., Ruoslahti E. 1980. High affinity of α-fetoprotein for arachidonate and other fatty acids. Biochem. J. 190: 301–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark E.D.B. 1998. Refolding of recombinant proteins. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 9: 157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronan Jr. J.E. and Rock C.O. 1987. Biosynthesis of membrane lipids. In Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: Cellular and molecular biology (eds. Neidhardt F.C. et al.) . pp. 474–497. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC 1:. [Google Scholar]

- Elbein A.D. 1991. The role of N-linked oligosaccharides in glycoprotein function. Trends Biotechnol. 9: 346–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie J.R. and Uversky V.N. 2000. Structure and function of α-fetoprotein: A biophysical overview. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1480: 41–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia J.C., Er J.S., Tan C.T., Ester T., Ruoslahti E. 1980. α-Fetoprotein binding specificity for arachidonate, bilirubin, docosahexaenoate, and palmitate: A spin label study. J. Biol. Chem. 255: 4224–4227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janzen R. and Tamaoki T. 1983. Secretion and glycosylation of α-foetoprotein by the mouse yolk sac. Biochem. J. 212: 313–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.J., Park S., Oh Y.K., Kang W., Kim H.S., Lee E.Y. 2005. Purification and characterization of human caseinomacropeptide produced by a recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Protein Expr. Purif. 41: 441–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi Y., Ooi T., Scheraga H.A. 1982. Regeneration of ribonuclease A from the reduced protein: Rate limiting steps. Biochemistry 21: 4734–4740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon K.S. and Yu M.H. 1997. Effect of glycosylation on the stability of α1-antitrypsin toward urea denaturation and thermal deactivation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1335: 265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong S.S.J. and Middelberg A.P.J. 2006. Dilution versus dialysis: A quantitative study of the oxidative refolding of recombinant human alpha-fetoprotein. Trans IChemE, Part C, Food Bioprod. Process. 84: 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Levine A.D., Rangwala S.H., Horn N.A., Peel M.A., Matthews B.K., Leimgruber R.M., Manning J.A., Bishop B.F., Olins P.O. 1998. High level expression and refolding of mouse interleukin 4 synthesized in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 270: 7445–7452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Zhang S., Wang C.C. 2001. Only the reduced conformer of α-lactalbumin is inducible to aggregation by protein aggregates. J. Biochem. 129: 821–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyles M.L. and Gilbert H.F. 1991. Catalysis of the oxidative folding of ribonuclease A by protein disulfide isomerase: Dependence of the rate on the composition of the redox buffer. Biochemistry 30: 613–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maachupalli-Reddy J., Kelly B.D., Clark E.D.B. 1997. Effect of inclusion body contaminants on the oxidative renaturation of hen egg white lysozyme. Biotechnol. Prog. 13: 144–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnuson K., Jackowski S., Rock C.O., Cronan Jr. J.E. 1993. Regulation of fatty acid biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Rev. 57: 522–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middelberg A.P.J. 2002. Preparative protein refolding. Trends Biotechnol. 20: 437–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morinaga T., Sakai M., Wegmann T.G., Tamaoki T. 1983. Primary structures of human α-fetoprotein and its mRNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 80: 4604–4608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nacka F., Chobert J.M., Burova T., Leonil J., Haertle T. 1998. Induction of new physicochemical and functional properties by the glycosylation of whey proteins. J. Protein Chem. 17: 495–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otvos L., Urge L., Thurin J. 1992. Influence of different N-linked and O-linked carbohydrates on the retention times of synthetic peptides in reversed-phase high-performance liquid-chromatography. J. Chromatogr. 599: 43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker M.H., Birck-Wilson E., Allard G., Masiello N., Day M., Murphy K.P., Paragas V., Silver S., Moody M.D. 2004. Purification and characterisation of a recombinant version of human α-fetoprotein expressed in the milk of transgenic goats. Protein Expr. Purif. 38: 177–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmelee D.C., Evenson M.A., Deutsch H.F. 1978. The presence of fatty acids in human α-fetoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 253: 2114–2119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattanaik P., Adiga P.R., Visweswariah S.S. 1998. Refolding of native and recombinant chicken riboflavin carrier (or binding) protein: Evidence for the formation of non-native intermediates during the generation of active protein. Eur. J. Biochem. 258: 411–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena V.P. and Wetlaufer D.B. 1970. Formation of three-dimensional structure in proteins: I. Rapid nonenzymic reactivation of reduced lysozyme. Biochemistry 25: 5015–5023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler M.L. and Kargi F. 1992. Utilizing genetically engineered organisms. In Bioprocess engineering: Basic concepts pp. 395–430. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

- Semeniuk D.J., Boismenu R., Tam J., Weissenhofer W., Murgita R.A. 1995. Evidence that immunosuppression is an intrinsic property of the α-fetoprotein molecule. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 383: 255–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shire S.J., Bock L., Ogez J., Builder S., Kleid D., Moore D.M. 1984. Purification and immunogenicity of fusion VP1 protein of food and mouth disease virus. Biochemistry 23: 6474–6480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland E.H. 1974. Aromatic contributions to circular dichroism spectra of proteins. CRC Crit. Rev. Biochem. 2: 113–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres J.M., Anel A., Uriel J. 1992. α-Fetoprotein-mediated uptake of fatty acids by human T lymphocytes. J. Cell. Physiol. 150: 456–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uversky V.N., Narizhnevam N.V., Ivanova T.V., Tomashevski A.Y. 1997. Rigidity of human α-fetoprotein tertiary structure is under ligand control. Biochemistry 36: 13638–13645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West C.M. 1986. Current ideas on the significance of protein glycosylation. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 72: 3–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woody R.W. 1994. Circular dichroism of peptide and proteins. In Circular dichroism: Principles and applications (eds. Nakanishi K. et al.) . pp. 473–496. , VCH, NY.