Abstract

The discriminant validity of the interpersonal–affective and social deviance traits of psychopathy has been well documented. However, few studies have explored whether these traits follow distinct or comparable developmental paths. The present study used the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (A. Tellegen, in press) to examine the development of the psychopathic traits of Fearless Dominance (i.e., interpersonal–affective) and Impulsive Antisociality (i.e., social deviance) from late adolescence to early adulthood in a longitudinal–epidemiological sample of male and female twins. Results from mean- and individual-level analyses revealed stability in Fearless Dominance from late adolescence to early adulthood, whereas Impulsive Antisociality declined over this developmental period. In addition, biometric findings indicated greater genetic contributions to stability in these traits and greater nonshared environmental contributions to their change over time. Collectively, these findings suggest distinct developmental trends for psychopathic traits from late adolescence to early adulthood.

Keywords: psychopathy, personality traits, development, behavior genetics

Delineating the developmental trajectory of psychopathic personality traits represents a relatively neglected, yet important, domain of research. For example, such investigations may help identify periods of normative change in these traits that could yield theoretical insights into the etiology of the construct as well as practical insights in terms of identifying the developmental stages most amenable to intervention. In recent years, empirical studies of psychopathy have begun to adopt such a developmental focus by extending the construct downward into adolescence and childhood (e.g., Edens, Skeem, Cruise, & Cauffman, 2001; Forth, Hare, & Hart, 1990; Forth, Kosson, & Hare, 2003; Frick, Bodin, & Barry, 2000; Frick, O’Brien, Wootton, & McBurnett, 1994; Gretton, Hare, & Catchpole, 2004; Lynam, 1996, 1998; Lynam & Gudonis, 2005; Salekin, Neumann, Leistico, DiCicco, & Duros, 2004; Taylor, Loney, Bobadilla, Iacono, & McGue, 2003; Viding, Blair, Moffitt, & Plomin, 2004). For example, in their review of the development of psychopathy, Lynam and Gudonis (2005) noted that juvenile psychopathy appears stable from childhood to adolescence and resembles adult psychopathy in terms of its relations to external criteria. Despite this emerging interest in psychopathy across the life span, few studies have directly examined the developmental course of psychopathic traits over time.

In the present study, we examined the development of psychopathic personality traits, as measured by the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (MPQ; Tellegen, in press), from late adolescence to early adulthood using a longitudinal–epidemiological sample of male and female twins. In particular, we sought to investigate whether the interpersonal–affective and social deviance traits of psychopathy, as measured via normal-range personality, exhibit distinct or comparable developmental trends. In addition, our genetically informative sample allowed us to investigate the degree to which genetic and environmental influences contribute to both continuity and change in psychopathic traits from late adolescence to early adulthood.

Clinical Conceptualizations of Psychopathy: Personality-Based Approaches

Clinical conceptualizations of psychopathy (Cleckley, 1941/1976; Karpman, 1941; McCord & McCord, 1964) are often described as personality-based conceptualizations (see Lilienfeld, 1994, 1998) in that the syndrome is viewed as a constellation of maladaptive personality traits. This conceptual approach emphasizes such traits as superficial charm, egocentricity, guiltlessness, callousness, dishonesty, failure to form close emotional bonds, absence of nervousness or anticipatory anxiety, and propensity to externalize blame. Moreover, these clinical conceptions can be distinguished from behavior-based approaches to psychopathy (e.g., Spitzer, Endicott, & Robins, 1975), which tend to emphasize the commission of specific antisocial or criminal acts. For example, although Cleckley (1941/1976) included evidence of behavioral deviance in his criteria (e.g., irresponsibility, poorly motivated antisocial behavior), he suggested that the manipulative interpersonal style and affective deficits of the psychopath represent the core personality features that distinguish the syndrome from common criminality.

In contrast to these clinical perspectives, most empirical investigations of psychopathy have employed either a behavior-based conceptualization or have investigated the construct within forensic settings with the Psychopathy Checklist—Revised (PCL-R; Hare, 1991, 2003), a semistructured interview that entails both criminal behaviors and clinician ratings of psychopathic traits. An alternative approach has been to draw from the clinical conceptions of the disorder and use a personality-based approach to construct self-report measures to assess psychopathy as it occurs within the general population (Lilienfeld, 1994). One such measure, the Psychopathic Personality Inventory (PPI; Lilienfeld & Andrews, 1996), is a self-report measure designed to capture a range of personality constructs relevant to clinical conceptions of psychopathy rather than antisocial behaviors per se. Validation studies have found PPI total scores to correlate positively with observer ratings of Cleckley psychopathy and self-report indices of narcissism, and inversely with self-reported fear, anxiety, and empathy (Lilienfeld & Andrews, 1996; Sandoval, Hancock, Poythress, Edens, & Lilienfeld, 2000). This suggests that the PPI indexes the classic clinical features of the syndrome. However, PPI total scores have also been shown to relate to measures of aggression, antisocial behavior, and substance abuse and dependence (Edens, Poythress, & Watkins, 2001; Lilienfeld & Andrews, 1996; Sandoval et al., 2000), indicating that this instrument also captures features related to an unstable and socially deviant lifestyle.

Based on this pattern of external correlates, as well as evidence linking the PPI to both the interpersonal–affective and social deviance facets of psychopathy (Poythress, Edens, & Lilienfeld, 1998), Benning, Patrick, Hicks, Blonigen, and Krueger (2003) factor analyzed PPI subscale scores from a community sample of male twins. Analyses yielded two dominant, uncorrelated factors. The first factor (Fearless Dominance [FD]; Benning, Patrick, Blonigen, Hicks, & Iacono, 2005) is marked by social dominance, narcissism, stress immunity, and fearlessness; core features of the interpersonal–affective facet of psychopathy. The second factor (Impulsive Antisociality [IA]; Benning et al., 2005) is marked by impulsivity, aggression, and alienation and is associated with substance abuse and dependence and antisocial deviance. Subsequent validation studies have shown that both FD and IA demonstrate convergent and discriminant validity for the interpersonal–affective and social deviance facets of the syndrome (Benning et al., 2003, 2005; Lilienfeld & Skeem, 2004).

FD and IA: Relations With Normal Personality

In addition to their factor analytic findings, Benning et al. (2003) noted that FD and IA can be measured effectively within the structural framework of normal personality. Multiple regression analyses revealed that the MPQ, a broadband measure of personality, can explain a substantial proportion of variance in FD and IA (Rs = .89 and .84, respectively, after correcting for attenuation).1 Moreover, recent criterion-validation studies have provided empirical support for the use of the MPQ to measure these constructs in both men and women and across incarcerated and nonincarcerated samples (Benning et al., 2005; Blonigen, Hicks, Krueger, Patrick, & Iacono, 2005; Ward, Benning, & Patrick, 2004). For example, MPQ-FD has been shown to be inversely related to self-report indices of fear and anxiety and symptoms of social phobia and depression, and positively related to sociability, adventure seeking, narcissism, and the interpersonal factor of the PCL-R (Benning et al., 2005; Blonigen et al., 2005; Ward et al., 2004). In contrast, MPQ-IA has been found to be positively related to self-report measures of anxiety, disinhibition, boredom susceptibility, symptoms of substance abuse and antisocial behavior, and the behavioral factor of the PCL-R (Benning et al., 2005; Blonigen et al., 2005; Ward et al., 2004). It is noteworthy that these patterns of relations with external criteria are highly similar to that of the PCL-R factors, suggesting that the MPQ constructs of FD and IA capture the nomological net of psychopathy within the domain of normal personality.

Developmental Investigations of Psychopathy

In examining the external correlates of FD and IA, it is clear that these traits exhibit distinct relations with diagnostic, demographic, and personality measures (Benning et al., 2003, 2005; Patrick, Edens, Poythress, & Lilienfeld, 2005; Ward et al., 2004) as well as divergent relations with broad domains of psychopathology on both a phenotypic and genotypic level (Blonigen et al., 2005). Such a pattern of discriminant validity has also been observed across the interpersonal–affective and social deviance facets of the PCL-R (Hare, 1991; Harpur, Hare, & Hakstian, 1989; Hart & Hare, 1989; Hemphill, Hart, & Hare, 1994; Patrick, 1994; Patrick, Zempolich, & Levenston, 1997; Reardon, Lang, & Patrick, 2002; Smith & Newman, 1990; Verona, Patrick, & Joiner, 2001).

Despite these findings, relatively little empirical research has investigated whether distinct developmental trends also emerge in these traits over time. Harpur and Hare (1994) reported a cross-sectional analysis of male criminal offenders (ages 16–69) in which they investigated whether psychopathy scores, operationally defined with the PCL-R, varied as a function of age. Results indicated that mean PCL-R Factor 1 scores (interpersonal–affective traits) remained stable across the life span, whereas mean PCL-R Factor 2 scores (social deviance traits) declined with age. Although, these findings suggest that the interpersonal–affective and social deviance facets follow distinct developmental trajectories, the authors acknowledged several limitations to their findings. First, because of the cross-sectional design, age effects could not be separated from any cohort effects, and an index of the rank-order stability of these traits could not be ascertained. Second, these results were limited to a male incarcerated sample and, therefore, may not reflect the development of psychopathic traits in either females or the general population. Third, although PCL-R Factor 2 has been linked to several personality traits (e.g., impulsivity, aggression), the scoring of Factor 2 items is heavily influenced by the occurrence of specific deviant behaviors. Thus, it is possible that the mean-level decline in the social deviance facet simply reflects an age-related decrease in deviant acts rather than a fundamental change in the underlying personality structure of this dimension. Given these shortcomings, a longitudinal–epidemiological design employing a measure of the personality traits underlying both dimensions of psychopathy may help to determine whether there are distinct developmental patterns to these dimensions.

Present Research Objectives

In the present investigation, we sought to examine the development of MPQ-estimated psychopathic personality traits of FD and IA from late adolescence to early adulthood using a longitudinal–epidemiological sample of male and female twins. Our primary objective was to investigate whether the developmental course of these traits is distinct or comparable across this critical period of psychological adjustment. Given the consistent finding of distinct relations between these constructs and external criteria, we hypothesized that these traits would also exhibit distinct developmental trends consistent with the cross-sectional findings based on the PCL-R (Harpur & Hare, 1994). As our second objective, we sought to utilize the genetically informative nature of our sample to investigate the degree to which genetic and environmental influences contribute to the development of psychopathic traits, as measured via normal personality, from late adolescence to early adulthood. On the basis of previous longitudinal–biometric investigations of personality in young adulthood (McGue, Bacon, & Lykken, 1993), we surmised that the stable portion of variance in these traits may owe more to genetic contributions, whereas change may be more environmentally mediated.

Method

Participants

Participants were male and female twins from the Minnesota Twin Family Study (MTFS), an ongoing epidemiological–longitudinal study of reared-together, same-sex twins and their parents. The primary focus of the MTFS is to identify the genetic and environmental bases of substance abuse and related psychopathology. The design of the MTFS has been thoroughly described by Iacono, Carlson, Taylor, Elkins, and McGue (1999) and Iacono and McGue (2002). Briefly, a population-based ascertainment method was used to identify, by means of public birth records, all the twin births in the state of Minnesota. For the present investigation, male twin pairs born between the years of 1972 and 1978 and female twin pairs born between the years of 1975 and 1979 were identified and recruited for participation the year the twins turned 17 years old. Over 90% of all twin pairs born during these target years were located. Seventeen percent of all eligible families declined participation. Although there were slightly, albeit significantly, more years of education among parents of participating families, no significant differences were observed between parents of participating and nonparticipating families with respect to self-reported rates of psychopathology (Iacono et al., 1999). Ninety-eight percent of participating twins were Caucasian, which is consistent with the demographics of Minnesota the year the twins were born. Families were excluded from participation if (a) they lived further than a 1-day drive from the Minneapolis laboratories or (b) either twin had a serious physical or cognitive disability that would hinder his or her completion of the day-long, in-person assessment.

Following completion of the age-17 intake assessment (Time 1), the sample size consisted of 626 complete pairs of monozygotic (MZ) and dizygotic (DZ) twins (men: nmz = 188, ndz = 101; women: nmz = 223, ndz = 114). This ratio of MZ to DZ twin pairs owes to both an overrepresentation of MZ twins relative to DZ twins in the population from which this sample was drawn (Hur, McGue, & Iacono, 1995) as well as a slightly greater likelihood of agreement to participate in MZ twins. To determine zygosity, separate reports from parents and MTFS staff regarding the physical resemblance between the twins were obtained and compared with an algorithm assessing the similarity between twins on ponderal and cephalic indices and fingerprint ridge counts. In cases in which the three estimates did not agree, a serological analysis was performed.

Measures

Scores on psychopathic traits of FD and IA were assessed with a 198-item version of the MPQ (Tellegen, in press). FD is uniquely predicted by MPQ primary scales of Social Potency (+), Stress Reaction (−), and Harm Avoidance (−), whereas IA is uniquely predicted by Social Closeness (−), Alienation (+), Aggression (+), Control (−), and Traditionalism (−) (see Benning et al., 2003). In the present study, we used items from the MPQ, rather than applying regression weights to MPQ primary scale scores, to estimate scores on FD and IA. Although two previous investigations (Benning et al., 2005; Blonigen et al., 2005) estimated these traits using regression weights reported by Benning et al. (2003), such an approach yields standardized scores and would therefore preclude us from examining mean and individual-level change in FD and IA over time. However, it should be noted that findings from these previous investigations, in which regression weights were used to estimate FD and IA from the MPQ (Benning et al., 2005; Blonigen et al., 2005), were essentially the same when using these MPQ items to estimate scores on FD and IA.2

MPQ-198 items were selected for inclusion on FD or IA according to the following criteria. Items for each factor were required to correlate at least |.20| with the target factor and to correlate with the other factor less than half as strongly as with the target factor. For example, if a target item correlated |.25| with the FD factor score, that item would have to correlate less than |.13| with the IA factor score. In addition, to ensure that these items would be available in all extant versions of the MPQ, we selected candidate items that appear in both the MPQ-198 and the MPQ-155 (Patrick, Curtin, & Tellegen, 2002). The final MPQ-estimated FD scale was comprised of 24 items—17 from the three MPQ scales identified by Benning et al. (2003) as being unique predictors of FD (i.e., Social Potency, Stress Reaction, and Harm Avoidance). The final MPQ-estimated IA scale comprised 34 items, including 32 from four of the five MPQ scales identified by Benning et al. (2003) as being unique predictors of IA (i.e., Alienation, Aggression, Control, and Traditionalism).3

Prior to both their initial visit at Time 1, when participants were age 17 on average, and their follow-up visit at Time 2, when they were age 24 on average, participants were mailed the MPQ and asked to bring their completed copies to their in-person visits. Participants who did not complete the MPQ either upon arrival for their visit or by the end of the day-long assessment were asked to complete the questionnaire at home and to return it by mail. FD and IA scores at both Time 1 and Time 2 were estimated and prorated in cases where a participant answered at least 70% of the items on both scales (Time 1: N = 1,131, nmen = 503, nwomen = 628; Time 2: N = 990, nmen = 433, nwomen = 557). Scores on FD and IA at both time points were available for 920 participants.4

To test for any bias due to attrition, we compared participants and nonparticipants at Time 2 on MPQ scores at Time 1. Effect sizes comparing participants and nonparticipants at Time 2 were minimal for all 11 primary scales from the MPQ with the mean Cohen’s d = .06 (range = .01 – .17). Thus, in terms of personality, twins who participated in the follow-up assessment appear to be representative of the original sample.

Data Analysis

We used three separate levels of analysis to examine the development of MPQ-estimated psychopathic traits from late adolescence to early adulthood: rank-order continuity, mean-level change, and individual-level change. Rank-order, or differential, continuity refers to consistency in the relative ordering of individuals in a population over time (see Roberts & DelVecchio, 2000). Although an examination of rank-order continuity cannot address, in absolute terms, the degree of growth or change in a particular trait over time, it can attest to the extent to which individuals maintain their relative placement within a group across time. For example, an individual who engages in fights once a month in late adolescence and once a year in early adulthood has decreased in absolute terms on his or her level of aggression. However, he or she may still rank first among peers on aggression and thus would be consistent in relative terms. Test–retest correlations were used in the present analyses to examine the rank-order continuity of FD and IA, with significance levels adjusted using a mixed model in SAS to account for the dependent nature of the twin observations.

Mean-level, or absolute, change refers to change in the quantity or amount of some trait in a population over time and is typically examined at the group level (see Roberts, Walton, & Viechtbauer, 2006). To the extent that traits change developmentally in the same direction for the majority of individuals in a group, this level of analysis reflects normative changes in traits over time. In the present study, mean-level change in FD and IA was assessed with a two-factor repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA; a within-group factor of Time and a between-groups factor of Gender). For both psychopathic traits, we report effects sizes for the main effects of time and gender, as well as the Time × Gender interaction, with partial eta-squared (η2; percent variance accounted for), which can be interpreted like r2 (Cohen, 1988). The main effect of time is also presented with Cohen’s d statistic (Cohen, 1988), which illustrates, in standard deviation units, both the direction and magnitude of change in these traits over time. Given the correlated nature of the twin observations, significance levels were also tested with a mixed model in SAS.

The third level of analysis focused on individual-level change in FD and IA over time. Individual-level change simply refers to change exhibited by each individual over time on a particular trait. Although individual and mean levels of analysis are intertwined, continuity at the group level can in some cases mask mutually canceling differences at the individual level. For example, within a population, a substantial proportion of individuals may be increasing significantly on a given trait, whereas an equally large proportion of individuals may also be decreasing on this trait over time. In effect, these groups would cancel each other out, yielding no significant mean-level change, yet there would still be substantial change at the individual level.

The Reliable Change Index (RCI; Christensen & Mendoza, 1986; Jacobson & Truax, 1991; Roberts, Caspi, & Moffitt, 2001; Robins, Fraley, Roberts, & Trzesniewski, 2001) was used to operationalize individual-level change in the present study. It is computed by dividing an individual’s change score from Time 1 to Time 2 (X2 – X1) by the standard error of the difference between the two scores (Sdiff). The Sdiff was computed using the standard error of measurement (SEM) for each trait at Times 1 and 2 (Sdiff = √[(SEMT1)2 + (SEMT2)2]). The RCI is intended to gauge whether an individual exhibits change on a particular trait that is greater than what would be expected by chance. Essentially, the Sdiff represents the distribution of change scores if change were due solely to measurement error. Therefore, assuming normality, RCI scores greater or less than ± 1.96 should only occur 5% of the time if change were due to chance alone (2.5% less than −1.96, 2.5% greater than + 1.96). Any percentage greater than this likely reflects true, reliable change in these traits over time.

Biometric Analyses

We used twin methodology and structural equation modeling to examine the genetic and environmental contributions to the development of FD and IA over time. Our objectives were threefold: (a) to determine whether the heritability of these traits remained consistent from Time 1 to Time 2, (b) to investigate the degree to which genetic and environmental variance in these traits at Time 2 is contributed from Time 1, and (c) to examine the extent to which genetic and environmental variance is unique to these traits at Time 2.

Twin methodology capitalizes on the difference in genetic relatedness between MZ and DZ twin pairs to estimate the relative genetic and environmental contributions to a phenotype. The phenotypic variance in FD and IA at Times 1 and 2 was decomposed into additive genetic, shared environmental, and nonshared environmental effects. Additive genetic effects (a2) involve the summation of genes across loci, whereas shared (c2) and nonshared (e2) environmental effects represent influences that are common and unique to each member of a twin pair, respectively.

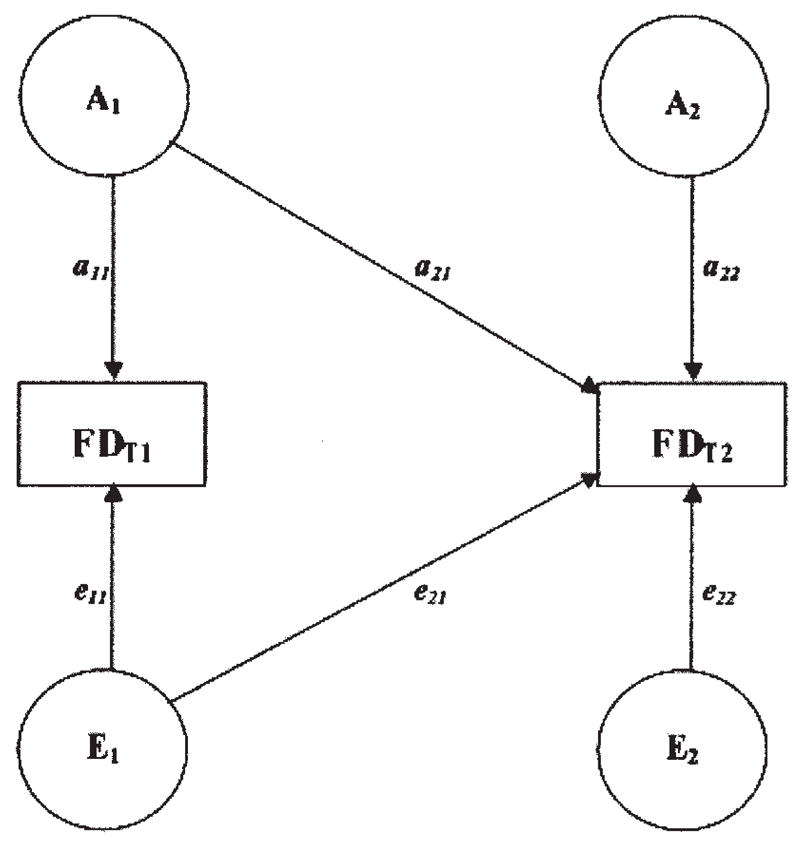

Biometric analyses involved a Cholesky decomposition (see Figure 1), which allows for an estimation of both the individual variance of each phenotype and the covariance among phenotypes that is due to genetic and environmental influences. This model was chosen for two purposes. First, it allowed for the partitioning of the shared variance between the MPQ-estimated psychopathic traits at Time 1 and Time 2 into their genetic and environmental components, thereby addressing the extent to which genetic and environmental variance at Time 2 is contributed from Time 1. This is represented in Figure 1 by the a21 and e21 paths from the Time 1 additive genetic (A1) and nonshared environmental (E1) factors to the Time 2 FD phenotype (FDT2). Second, this model allowed us to parse the residual variance at Time 2 into genetic and environmental factors, thereby providing an estimation of the degree to which genetic and environmental influences are unique or innovative at Time 2. This is represented in Figure 1 by the a22 and e22 paths from the Time 2 additive genetic (A2) and nonshared environmental (E2) factors to the Time 2 FD phenotype (FDT2).

Figure 1.

Path diagram of an AE Cholesky model for Fearless Dominance (FD) at Time 1 (T1) and Time 2 (T2). In this model, the variance at each time point is decomposed into additive genetic (A1, A2) and non-shared environmental effects (E1, E2). For ease of interpretation, shared environmental effects (c2) were omitted from this diagram. a11 and e11 = paths representing additive genetic and nonshared environmental contributions to the Time 1 phenotype, respectively; a21 and e21 = paths representing additive genetic and nonshared environmental contributions from Time 1 to the Time 2 phenotype, respectively; a22 and e22= paths representing additive genetic and nonshared environmental contributions unique to the Time 2 phenotype, respectively. These paths are squared to estimate the proportion of variance accounted for by additive genetic and nonshared environmental influences.

Prior to obtaining parameter estimates, model-fitting analyses were performed with Mx, a structural equation modeling program (Neale, Boker, Xie, & Maes, 2002). Models were fit to the raw data using a Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) technique that corrects for potential statistical biases resulting from missing data. Consistent with the biometric findings reported for these participants at age 17 (Blonigen et al., 2005), the best-fitting Cholesky model for both FD and IA contained an additive genetic (A) and nonshared environmental (E) parameter. The inclusion of a shared environmental (C) parameter failed to provide a better fit than the AE model. Moreover, when C was included in the model, all such parameter estimates were virtually zero.

All parameter estimates from the biometric analyses are presented separately for men and women based on models allowing these estimates to differ by gender. However, all estimates could be constrained across men and women without a significant decrease in the fit of the model. Therefore, parameter estimates for the total sample are also reported.

Results

Continuity and Change in Psychopathic Traits From Age 17 to Age 24

Internal consistency reliability estimates (based on Cronbach’s alpha) at ages 17 and 24, along with the 7-year test–retest correlations (Pearson correlations) for FD and IA, are presented in Table 1. Both FD and IA demonstrated strong internal consistency in late adolescence and early adulthood, with alphas ranging from .79 to .88 for these constructs across time. In terms of the test–retest correlations, both FD and IA also exhibited moderate to large rank-order consistency from ages 17 to 24, with stability coefficients ranging from .47 to .60 across men and women. Moreover, all correlations were highly significant (all ps < .001). Using the internal consistency reliability estimates for FD and IA, we also corrected the test–retest correlations for their attenuation due to this unreliability. The stability coefficients increased for both traits, with FD increasing from .60 to .75 and IA increasing from .53 to .61. Thus, relative to one another, individuals remained fairly consistent on both psychopathic trait dimensions from late adolescence to early adulthood.

Table 1.

Internal Consistency and Rank-Order Continuity (Test–Retest Correlations) of MPQ-Estimated Psychopathic Traits From Age 17 to Age 24

| Internal consistency reliability

|

Test–retest correlations

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trait | Age 17 | Age 24 | Men | Women | Total | Corrected for attenuation |

| Fearless Dominance | .79 | .82 | .60 | .59 | .60 | .75 |

| Impulsive Antisociality | .86 | .88 | .47 | .54 | .53 | .61 |

Note. NTotal = 920, nMen = 391, nWomen = 529. Significance levels were adjusted using a mixed model in SAS to account for the correlated nature of the twin observations. MPQ = Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire. All ps < .001.

Table 2 provides the results of the repeated measures ANOVA, which we used to evaluate the degree of mean-level change in these traits from ages 17 to 24. The means, standard deviations, and estimates of effect size (d statistics) are presented for the total sample as well as separately for men and women. For FD, the main effect of time was not significant, F(1, 918) = 1.68, ns, indicating continuity in this trait dimension at the mean level. The main effect of gender for FD traits, however, was significant, F(1, 918) = 43.59, p < .001. Follow-up t tests revealed that men scored significantly higher than women on FD at both Time 1, t(1, 1129) = 4.09, p < .001, and Time 2, t(1, 988) = 8.40, p < .001. Of note, the Time × Gender interaction for FD, F(1, 918) = 25.0, p < .001, was also significant. An inspection of the means and d statistics for men and women reveals that this interaction was due to both a slight increase in FD traits for men from late adolescence to early adulthood (d = .12) as well as a slight decrease in these traits for women across this period (d = −.18).

Table 2.

Mean-Level Change in MPQ-Estimated Psychopathic Traits From Age 17 to Age 24 (Repeated Measures Analyses of Variance)

| Age 17

|

Age 24

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trait | M | SD | M | SD | d (time) | η2 (time) | η2 (gender) | η2 (Time × Gender) |

| Fearless Dominance | ||||||||

| Total | 64.2 | 8.3 | 63.7 | 8.7 | −.06 | .00 | .05** | .03** |

| Men | 65.4 | 7.5 | 66.3 | 8.2 | .12 | .02* | — | — |

| Women | 63.3 | 8.8 | 61.8 | 8.5 | −.18 | .04** | — | — |

| Impulsive Antisociality | ||||||||

| Total | 76.0 | 12.4 | 64.7 | 11.8 | −.93 | .48** | .07** | .00 |

| Men | 79.1 | 11.4 | 68.3 | 12.1 | −.92 | .45** | — | — |

| Women | 73.8 | 12.7 | 62.1 | 10.8 | −.99 | .51** | — | — |

Note. NTotal = 920, nMen = 391, nWomen = 529. Significance levels of effects were adjusted in a mixed model in SAS to account for the dependent nature of the twin observations. d (time) and η2 (time) = Cohen’s d statistic and partial eta-squared effect sizes, respectively, for the main effect of time; η2 (gender) = percentage variance accounted for by the main effect of gender; η2 (Time × Gender) = percentage variance accounted for by the interaction between time and gender.

p < .01.

p < .001.

For IA, the main effect of time was highly significant, F(1, 918) = 828.92, p < .001, with nearly a full standard deviation decrease in these traits for the total sample (d = −.93) and for both men (d = −.92) and women (d = −.99). Thus, in contrast to FD, IA traits decreased markedly at the mean level from age 17 to age 24. The main effect of gender was also significant for IA, F(1, 918) = 69.95, p < .001. Again, follow-up t tests revealed that men scored significantly higher than women on IA at both Time 1, t(1, 1129) = 8.02, p < .001, and Time 2, t(1, 988) = 8.89, p < .001. The Time × Gender interaction for IA was not significant, F(1, 918) = 1.26, ns.5

As noted earlier, the apparent continuity in FD traits at the mean level may be masking mutually canceling differences at the individual level. Table 3 presents results from the individual-level analyses based on the RCI including the percentage of individuals that decreased or increased reliably on these traits and the percentage that stayed the same. Chi-square tests comparing the observed distribution of changers and nonchangers to the expected distribution (i.e., the number of participants expected to have extreme RCI scores simply due to chance) were highly significant for both FD and IA, indicating reliable change in these traits. Consistent with the mean-level analyses, however, a substantially greater number of participants exhibited reliable change on IA than on FD. In particular, a greater proportion of individuals decreased on IA than on FD, though for both traits the number of participants that decreased was greater than what would be expected by chance alone. In conjunction with the mean-level findings, these results suggest distinct developmental trends for the trait dimensions of FD and IA, with FD remaining relatively stable from late adolescence to early adulthood and IA declining over this period.

Table 3.

Individual-Level Change in MPQ-Estimated Psychopathic Traits From Age 17 to Age 24 (Reliable Change Index)

| Trait | Decreased (%) | Same (%) | Increased (%) | χ2 (2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fearless Dominance | ||||

| Total | 10.2 | 85.0 | 4.8 | 248.0** |

| Men | 6.1 | 87.5 | 6.4 | 44.4** |

| Women | 13.2 | 83.2 | 3.6 | 260.6** |

| Impulsive Antisociality | ||||

| Total | 46.3 | 51.6 | 2.1 | 7,244.1** |

| Men | 42.2 | 55.8 | 2.0 | 2,465.9** |

| Women | 49.3 | 49.4 | 1.3 | 4,850.3** |

Note. NTotal = 920, nMen = 391, nWomen = 529. Decreased (%), Same (%), and Increased (%) refer to the percentage of individuals who decreased, remained the same, or increased on the psychopathic traits, respectively, on the basis of the Reliable Change Index. Chi-square tests compare the observed distribution of changers and nonchangers to the expected distribution if changes were due to chance alone (i.e., 2.5% each decrease and increase, 95% stay the same).

p < .001.

Biometric Contributions to Psychopathic Traits From Age 17 to Age 24

Parameter estimates from the best-fitting Cholesky models are provided in Table 4. As noted previously, the best-fitting model for both FD and IA was a model containing an additive genetic (A) and nonshared environmental (E) parameter. Parameter estimates are presented separately by gender as well as for the total (combined) sample. However, all estimates could be constrained across men and women without a significant decrement in the fit of the model.

Table 4.

Parameter Estimates From Cholesky Models for MPQ-Estimated Psychopathic Traits (Age 17 to Age 24)

| Age 17

|

Age 24

|

Variance partition (T2)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trait | a2 | e2 | a2 | e2 | a2 (from T1) | e2 (from T1) | a2 (unique) | e2 (unique) |

| Fearless Dominance | ||||||||

| Combined | .48 (.40, .56) | .52 (.44, .60) | .42 (.33, .51) | .58 (.49, .67) | .25 (.17, .34) | .12 (.08, .18) | .17 (.10, .25) | .45 (.39, .53) |

| Men | .54 (.41, .64) | .46 (.36, .59) | .48 (.34, .59) | .52 (.41, .56) | .29 (.16, .42) | .10 (.04, .19) | .19 (.08, .30) | .42 (.33, .53) |

| Women | .46 (.35, .55) | .54 (.45, .65) | .39 (.26, .50) | .61 (.50, .74) | .23 (.13, .35) | .14 (.07, .23) | .16 (.06, .25) | .47 (.38, .58) |

| Impulsive Antisociality | ||||||||

| Combined | .46 (.37, .53) | .54 (.47, .63) | .49 (.40, .57) | .51 (.43, .60) | .23 (.14, .32) | .07 (.03, .11) | .26 (.18, .34) | .44 (.38, .52) |

| Men | .43 (.30, .54) | .57 (.46, .70) | .49 (.35, .60) | .51 (.40, .65) | .21 (.09, .35) | .06 (.02, .13) | .28 (.14, .41) | .45 (.35, .58) |

| Women | .47 (.36, .56) | .53 (.44, .64) | .49 (.37, .59) | .51 (.41, .63) | .24 (.14, .36) | .08 (.03, .15) | .24 (.14, .34) | .43 (.35, .53) |

Note. N = 1,252 individuals from 626 twin pairs, some with missing data. “Combined” refers to a model in which the parameter estimates were constrained across men and women. None of the parameter estimates were significantly different between men and women. a2 = additive genetic variance; e2 = nonshared environmental variance; Variance partition (T2) = partitioning of the total variance at Time 2 into the genetic and environmental effects that are contributed from Time 1 (from T1), and genetic and environmental effects that are unique to Time 2 (unique). 95% confidence intervals are listed in parentheses.

At ages 17 and 24, roughly half the variance of both FD and IA was due to additive genetic effects, with the other half due to nonshared environmental effects. Moreover, models in which the magnitudes of the heritability estimates for these traits were constrained to be the same across time were not significantly different from models in which they were allowed to vary: χ2(1) = 1.47, ns, for FD; χ2(1) = 0.42, ns, for IA. Thus, the heritability of both traits remained consistent across time.

In the present investigation, however, we were primarily interested in examining the extent to which the genetic and environmental variance in these traits at Time 2 is contributed from Time 1 or is unique or specific to these traits at Time 2. Table 4 provides a breakdown of these effects for FD and IA. In partitioning the variance in these traits at Time 2, a comparison of the genetic and environmental contributions from Time 1 (a2 from T1 and e2 from T1, respectively) reveals that a larger proportion of the variance from Time 1 was due to additive genetic contributions. In contrast, a comparison of the genetic and environmental contributions unique to Time 2 (a2 unique and e2 unique, respectively) reveals that a larger proportion of the residual or unique variance at Time 2 was due to nonshared environmental effects. Further, an inspection of the genetic covariance for FD and IA (i.e., the proportion of the phenotypic covariance in these traits across time that is due to additive genetic contributions) revealed that 58% of the stable variance in FD and 62% of the stable variance in IA was due to additive genetic effects. As a whole, these findings suggest that the stable portion of variance in these traits from late adolescence to early adulthood is due primarily to genes, whereas the portion of variance that is unique or changing at Time 2 may be more environmentally mediated. In addition, for both FD and IA, there were significant genetic contributions unique to Time 2, which (in the case of IA traits) were as large, or larger, than the additive genetic contributions from Time 1. This indicates that normative change in the variance of these traits may owe in part to the emergence of innovative genetic contributions in early adulthood.

Discussion

In the present study, we used a longitudinal sample of male and female twins to investigate whether there are distinct or comparable developmental trends to psychopathic traits, as measured via normal-range personality, from late adolescence to early adulthood. Test–retest correlations demonstrated that both FD and IA, personality constructs related to the interpersonal–affective and social deviance facets of psychopathy, respectively, exhibited moderate to large rank-order stability from ages 17 to 24. In contrast, mean- and individual-level analyses revealed stability in FD from late adolescence to early adulthood, whereas IA declined over this period, indicating distinct developmental patterns for these traits. In addition, we examined genetic and environmental contributions to both stability and change in the variance of these traits. Approximately half of the variance in both traits was due to genetic contributions, with heritability estimates remaining consistent over time. Moreover, a partitioning of the Time 2 variance into the genetic and environmental effects contributed from Time 1 and unique to Time 2 suggested larger genetic contributions to stability in these traits and greater nonshared environmental contributions to their change over time.

Development of Psychopathic Traits: An Emphasis on Personality

Empirical investigations explicitly examining the development of psychopathic traits across the life span have been relatively absent in the literature. An exception to this is an investigation by Harpur and Hare (1994), in which the authors found mean scores on the interpersonal–affective facet of the PCL-R (Factor 1) to be unrelated to age of assessment, whereas mean scores on the social deviance facet (Factor 2) declined with age. However, as Harpur and Hare (1994) pointed out, because the scoring of Factor 2 relies heavily on behavioral indicators that are age biased, the decrease in these scores cannot address whether there are similar developmental changes in the underlying personality traits of this dimension. Therefore, the underlying personality structure of Factor 2 may either be as stable as the personality constructs underlying Factor 1 or may in fact be directly contributing to a decline in these scores over time.

The present study sought to resolve these issues by examining personality-based constructs originally derived from the PPI and designed to reflect clinical conceptions of psychopathy (Lilienfeld & Andrews, 1996). Collectively, the findings were consistent with the cross-sectional analysis of the PCL-R (Harpur & Hare, 1994) and suggest that from late adolescence to early adulthood there are distinct developmental trends to the underlying personality traits of psychopathy. In addition to our personality-based approach, the present study extends the findings of Harpur and Hare (1994) in other important ways. For example, the use of a longitudinal design allowed us to examine the rank-order stability of these traits over time. Test–retest correlations, which represent broad-based indicators of trait continuity, revealed comparable rank-order stability for FD and IA from late adolescence to early adulthood. Thus, relative to one another, individuals remained fairly consistent on both traits across this period. Moreover, the magnitude of these correlations is similar to previous findings on the rank-order stability of personality from late adolescence to early adulthood (cf. Roberts et al., 2001; Roberts & DelVecchio, 2000; Robins et al., 2001; Stein, Newcomb, & Bentler, 1986).

Another important aspect of the present design is the nature of the sample. Specifically, we used a community–epidemiological sample of both men and women to establish the generalizability of the findings. Given that most empirical investigations of psychopathy have been conducted in incarcerated settings, the use of a nonincarcerated sample extends our understanding of the development of psychopathic traits to the general population, which may in turn yield insights into subclinical manifestations of the disorder. Nonetheless, it may be important for future studies to replicate the present findings in individuals with extreme elevations on these traits (i.e., forensic samples). However, it is also important to note that, in the present cohort, rates of DSM diagnoses related to psychopathy are comparable to rates observed in other epidemiological studies (e.g., Kessler et al., 1994, 2005), suggesting that some individuals in the present sample do possess clinically and socially meaningful levels of psychopathology (see Krueger et al., 2002, for prevalence rates in the MTFS).

The inclusion of both men and women was another advantage in that it permitted us to examine sex differences in the developmental course of these traits. Although men exhibited higher mean levels on both FD and IA in late adolescence and early adulthood, patterns of continuity and change in these traits across all levels of analysis were largely the same for men and women. An exception to this pattern was the Time × Gender interaction for FD, in which men increased, and women decreased slightly, on these traits over time. However, the effect sizes based on these changes were relatively small (d = .12 and −.18 for men and women, respectively) and are still consistent with a general pattern of continuity in FD over time. Notably, in a previous longitudinal investigation of normal personality using the MPQ (Roberts et al., 2001), a similar gender difference was observed on the Harm Avoidance subscale, a normal range personality correlate of FD.

Biometric Contributions to the Development of Psychopathic Traits

In the present investigation, we also utilized our genetically informative sample to infer the degree to which genetic and environmental factors contribute to both continuity and change in MPQ-estimated psychopathic traits over time. In parsing the variance in these traits at Time 2, it was revealed that a larger proportion of the variance contributed from Time 1 was due to genetic influences, whereas a larger proportion of the residual variance at Time 2 was due to nonshared environmental contributions. This pattern is generally consistent with previous longitudinal twin studies of personality in early adulthood (e.g., McGue et al., 1993) and indicates that stability in these traits may owe more to genetic factors, whereas change over time may be more environmentally mediated. However, despite the predominance of environmental contributions to change over time, there remained significant and unique genetic contributions to the residual variance in these traits at Time 2. This pattern, which has been observed in prior longitudinal twin studies of personality (cf. Dworkin, Burke, Maher, & Gottesman, 1976; McGue et al., 1993), suggests that innovative genetic factors emerging in early adulthood may contribute to normative change in psychopathic traits.

Theoretical Implications

The present findings have interesting theoretical implications for the construct of psychopathy. Since the inception of the PCL-R, psychopathy has been traditionally conceptualized as a single higher-order construct subsumed by two or more correlated factors (Cooke & Michie, 2001; Hare, 2003; Harpur et al., 1989). However, findings of heterogeneity among PCL–R-defined psychopaths (e.g., Hicks, Markon, Patrick, Krueger, & Newman, 2004; Skeem, Poythress, Edens, Lilienfeld, & Cale, 2003; Patrick, Bradley, & Lang, 1993) as well as consistent findings of discriminant validity between the interpersonal–affective and social deviance facets (e.g., Hare, 1991; Harpur et al., 1989; Hart & Hare, 1989; Hemphill et al., 1994; Patrick, 1994; Patrick et al., 1997; Reardon et al., 2002; Smith & Newman, 1990; Verona et al., 2001) have called into question the notion of psychopathy as a unitary construct. The findings of Harpur and Hare (1994) are similar in this respect in that they demonstrate heterogeneity in the development of psychopathy. However, as we have noted, their results may not address the development of the underlying personality structure of the disorder.

In response to this issue, several scholars have suggested that an examination of psychopathy within a structural model of personality can clarify the heterogeneous nature of the construct and help to resolve differential findings for the interpersonal–affective and social deviance facets (Brinkley, Newman, Widiger, & Lynam, 2004; Hicks et al., 2004; Lilienfeld, 1994, 1998; Lykken, 1995; Lynam, 2002; Miller, Lynam, Widiger, & Leukefeld, 2001; Widiger & Lynam, 1998). The present study used this approach and illustrates one example of how such an approach may help inform broader issues in the psychopathy literature. Specifically, if one were to consider the personality-based clinical descriptions of the syndrome (e.g., Cleckley, 1941/1976; Karpman, 1941; McCord & McCord, 1964) as being reflected in the structure of normal personality, the present findings of distinct developmental paths to these traits suggest that the interpersonal–affective and social deviance facets may reflect separable trait dimensions of personality with distinct etiologic processes (Blonigen et al., 2005; Patrick, in press).

Limitations and Future Directions

We conclude this discussion by reviewing some limitations to the present findings and avenues for future research. First, although our longitudinal design had numerous advantages, this investigation was limited to only two time points, thereby restricting our conclusions to a relatively small developmental window. However, the period from late adolescence to early adulthood represents a turbulent period of psychological adjustment and is typically characterized by a host of life-course transitions (Hall, 1904; Hathaway & Monachesi, 1953; Siegel, 1982). This is most clearly exemplified in the fact that epidemiological studies have found this age range to show enhanced prevalence of mental disorder, with lower prevalences for older individuals (e.g., Kessler et al., 1994, 2005). Moreover, Caspi and Moffitt (1993), as well as others (e.g., Roberts et al., 2001), have noted that individual differences are accentuated during the transition from late adolescence to early adulthood and reveal distinct patterns of continuity and change. Altogether, the period from late adolescence to early adulthood represents a critical period of development that requires further explication with respect to both personality and psychopathy.

Second, with respect to the biometric results, it should be clearly noted that these findings can only address the genetic and environmental contributions to continuity and change in the variance of these traits and cannot attest to the etiologic contributions to the aforementioned mean- or individual-level changes. To examine the biometric contributions to such changes would require the use of latent growth-curve or latent trajectory models (see Neale & McArdle, 2000), structural modeling techniques that require more than two time points in a longitudinal design. Nevertheless, the present biometric analyses can address the genetic and environmental contributions to the rank-order findings, given that these results essentially reflect continuity and change in the covariance structure of these traits over time rather than changes at the individual or group level.

In addition, we used a structural model of personality, rather than the PCL-R (the measure most commonly used in the assessment of psychopathy), to index psychopathic traits in the present study. However, as noted earlier, the PCL-R is limited both in its ability to investigate psychopathy within nonincarcerated populations and in terms of its utility in investigating the underlying personality structure of the syndrome. Nevertheless, it may be premature to use the MPQ constructs of FD and IA as proxy measures of PCL-R psychopathy for several reasons.

First, although FD and IA demonstrate convergent and discriminant relations with the interpersonal and behavioral factors of the PCL-R, their correlations are fairly modest (see Benning et al., 2005).6 Although this is undoubtedly due in part to method variance (i.e., MPQ assessed with self-report, PCL-R assessed with interview- and file ratings), these measures cannot be considered to be isomorphic and thus appear to be tapping only partly overlapping constructs. Second, FD, though linked to the interpersonal facet of psychopathy, did not correlate significantly with the affective facet of the PCL-R in the study by Benning et al. (2005). However, IA did exhibit a significant zero-order correlation with the affective facet (r = .20). In any case, the affective facet, long viewed as central in traditional conceptions of psychopathy, appears to be represented to only a limited extent in these MPQ constructs. Third, whereas the PCL-R factors are moderately correlated, the constructs of FD and IA are orthogonal (Benning et al., 2003, 2005; Blonigen et al., 2005). Although an orthogonal factor structure is consistent with the assertion by some theorists that separate etiologic processes may underlie the interpersonal–affective and social deviance facets of psychopathy (Patrick, 2001, in press), these MPQ constructs may be modeling only the unique variance associated with the PCL-R factors rather than their shared variance. If this shared variance is predictive of external criteria above and beyond the unique variance associated with each factor, this would represent a limitation to the use of the MPQ as a proxy measure of PCL-R psychopathy. On the other hand, there is evidence to suggest the presence of cooperative suppressor effects (see McHoskey, Worzel, & Szyarto, 1998) in that this shared variance may be obscuring relations between these factors and external criteria that are in fact more robust and consistent with theoretical predictions when the unique variance of each factor is isolated (see also Patrick, 1994; Verona, Hicks, & Patrick, 2006; Verona et al., 2001). Ultimately, future research should endeavor to clarify this issue, given the implications for the validity of these MPQ constructs as indices of psychopathy.

As a whole, these divergences between the PCL-R and the FD and IA constructs suggest caution in using the MPQ as a measure of psychopathy. These issues notwithstanding, the findings of Benning et al. (2005) do demonstrate across two community samples as well as a sample of incarcerated male offenders that the pattern of relations with external criteria for FD and IA parallels the external correlates of PCL-R Factors 1 and 2, respectively. These results provide support for the construct validity of these MPQ factors, given that they capture the same (or very similar) nomological net as do the PCL-R factors, at least in terms of the criterion measures available in this study. Moreover, this assertion is further strengthened by the present results in that the developmental trends appear largely parallel for the MPQ and PCL-R factors. Despite this evidence, it still may be premature to use the MPQ as a proxy measure of PCL-R psychopathy until further psychometric testing and replication is conducted that can specifically address the aforementioned concerns. For example, it would be valuable to examine relations between MPQ and PCL-R factors when assessed within the same measurement domain (i.e., interview- and file-based ratings) to see whether associations are higher than when assessed in different measurement domains. Nonetheless, the personality constructs underlying FD and IA may offer a complementary conceptualization to the PCL-R—one that relates closely to the seminal clinical literature on psychopathy (Cleckley, 1941/1976) and could potentially contribute to a greater integrative understanding of the construct.

The present findings raise some interesting questions and possible avenues for future research. First, in observing the decline in IA, it is noteworthy that this decline coincides with the normative maturation and development of the prefrontal cortex (PFC). Evidence from magnetic resonance imaging (Giedd et al., 1999; Sowell, Thompson, Holmes, Jernigan, & Toga, 1999), electrophysiological (Hudspeth & Pribram, 1992; Segalowitz & Davies, 2004), neuropsychological (Levin, Culbane, Hartmann, Evankovich, & Mattson, 1991), and biochemical investigations (e.g., Webster, Weickert, Herman, & Kleinman, 2002) has demonstrated that the associated divisions of the PFC (e.g., orbital, ventromedial, dorsolateral) do not reach structural maturity until early adulthood. Moreover, various regions of the PFC have been posited by some theorists as possible neural substrates underlying the expression of disinhibitory (externalizing) psychopathology (Blair, 2004; Patrick, 2001, in press). Given that IA and its normal-range personality correlates have been linked empirically to a range of externalizing disorders (Benning et al., 2003, 2005; Krueger et al., 2002), it is conceivable that the decline in IA may reflect the normative maturation of the PFC from late adolescence to early adulthood. Although no studies to our knowledge have directly compared these developmental findings within the same design, further investigation of personality change in relation to neuropsychological development represents a promising area of future research.

Second, the decline in IA from late adolescence to early adulthood parallels the age–crime curve, a phenomenon in which the prevalence and incidence of criminal offending tends to peak in late adolescence but declines in early adulthood (Blumstein, Cohen, & Farrington, 1988). Although this relationship between age and crime has been repeatedly observed across gender, types of crimes, and in numerous Western nations (Moffitt, 1993), the precise mechanism underlying this relationship is not well understood (Sampson & Laub, 1995). From a psychological perspective, the present findings raise the possibility that the age–crime curve may be due in part to changes in personality such that normative maturation in IA traits during this period of development may contribute to desistance in criminal and delinquent behavior for most individuals in the population. Although alternative sociological explanations may be tenable as well (see Sampson & Laub, 1997), further inquiry into the manner in which personality change may contribute to this process represents another intriguing area for research (Roberts et al., 2001).

In summary, we used a longitudinal and genetically informative sample to investigate the developmental course of psychopathic traits as conceptualized within a structural model of personality. The observed pattern of both continuity and change in FD and IA illustrates that the development of psychopathic traits is a complex and dynamic process that can be investigated and operationalized on several levels. Accordingly, similar longitudinal investigations of psychopathy across other important developmental periods (e.g., childhood to adolescence—see Lynam & Gudonis, 2005) are encouraged in order to gain a more comprehensive assessment of the development of psychopathic personality traits across the life span.

Acknowledgments

The Minnesota Twin Family Study was supported in part by U.S. Public Health Service Grants AA00175, AA09367, DA05147, and MH65137. Daniel M. Blonigen was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health Training Grant MH17069.

Footnotes

Given that the PPI and MPQ were administered 4–6 years apart, previous multiple Rs reported by Benning et al. (2003) were likely attenuated as a result of the unreliability inherent in administering personality tests over such an extended period of time (Benning et al., 2005).

All analyses in the present investigation that were testable using a regression-weighted approach to estimate the psychopathic traits (i.e., not the mean and individual-level analyses) were also essentially identical to the results using MPQ items.

Because of copyright restrictions, we are unable to provide any illustrative items. However, the complete set of items is available from the owner of the copyright (i.e., University of Minnesota Press). Further, the reader may contact Daniel M. Blonigen for the specific item numbers selected for the present investigation.

This listwise approach did not appear to bias the results, as the test–retest correlations using a raw data or FIML technique, which corrects for potential statistical biases resulting from missing data, were essentially identical to the correlations using a listwise approach.

In a repeated measures ANOVA comparing differences between MZ and DZ twins on FD and IA over time, neither the main effect of zygosity for FD, F(1, 918) = 0.21, ns, and IA, F(1, 918) = 0.25, ns, nor the zygosity by time interaction for FD, F(1, 918) = 0.04, ns, or IA, F(1, 918) = 0.41, ns, was significant.

In the study by Benning et al. (2005), FD and the interpersonal factor of the PCL-R correlated .30 and .32, based on zero-order and partial correlations, respectively. Conversely, IA and the behavioral factor of the PCL-R correlated .41 and .37, based on zero-order and partial correlations, respectively.

References

- Benning SD, Patrick CJ, Blonigen DM, Hicks BM, Iacono WG. Estimating facets of psychopathy from normal personality traits: A step toward community-epidemiological investigations. Assessment. 2005;12:3–18. doi: 10.1177/1073191104271223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benning SD, Patrick CJ, Hicks BM, Blonigen DM, Krueger RF. Factor structure of the Psychopathic Personality Inventory: Validity and implications for clinical assessment. Psychological Assessment. 2003;15:340–350. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.15.3.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair RJR. The roles of orbital frontal cortex in the modulation of antisocial behavior. Brain and Cognition. 2004;55:198–208. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2626(03)00276-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blonigen DM, Hicks BM, Krueger RF, Patrick CJ, Iacono WG. Psychopathic personality traits: Heritability and genetic overlap with internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35:637–648. doi: 10.1017/S0033291704004180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumstein A, Cohen J, Farrington DP. Criminal career research: Its value for criminology. Criminology. 1988;26:1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkley CA, Newman JP, Widiger TA, Lynam DR. Two approaches to parsing the heterogeneity of psychopathy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2004;11(1):69–94. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE. When do individual differences matter? A paradoxical theory of personality coherence. Psychological Inquiry. 1993;4:247–271. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen L, Mendoza JL. A method of assessing change in a single subject: An alteration of the RC index. Behavior Therapy. 1986;17:305–308. [Google Scholar]

- Cleckley HM. The mask of sanity. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 19411976. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke DJ, Michie C. Refining the construct of psychopathy: Towards a hierarchical model. Psychological Assessment. 2001;13:171–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin RH, Burke BW, Maher BA, Gottesman II. A longitudinal study of the genetics of personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1976;34:510–518. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.34.3.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edens JF, Poythress NG, Watkins M. Further validation of the Psychopathic Personality Inventory among offenders: Personality and behavioral correlates. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2001;15:403–415. doi: 10.1521/pedi.15.5.403.19202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edens JF, Skeem J, Cruise KR, Cauffman E. Assessment of “juvenile psychopathy” and its association with violence: A critical review. Behavioral Sciences and the Law. 2001;19:53–80. doi: 10.1002/bsl.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forth AE, Hare RD, Hart SD. Assessment of psychopathy in male young offenders. Psychological Assessment. 1990;2:342–344. [Google Scholar]

- Forth AE, Kosson DS, Hare RD. The Psychopathy Checklist: Youth Version. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Multi-Health Systems; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Bodin D, Barry C. Psychopathic traits and conduct problems in community and clinic-referred samples of children: Further development of the Psychopathy Screening Device. Psychological Assessment. 2000;12:382–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, O’Brien BS, Wootton JM, McBurnett K. Psychopathy and conduct problems in children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:700–707. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.4.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giedd JN, Blumenthal J, Jeffries NO, Castellanos FX, Liu H, Zijdenbos A, et al. Brain development during childhood and adolescence: A longitudinal MRI study. Nature Neuroscience. 1999;2:861–863. doi: 10.1038/13158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gretton HM, Hare RD, Catchpole REH. Psychopathy and offending from adolescence to adulthood: A 10-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:636–645. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall GS. Adolescence: Its psychology and its relations to physiology, anthropology, sociology, sex, crime, religion, and education. 1–2. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1904. [Google Scholar]

- Hare RD. The Hare Psychopathy Checklist–Revised. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Multi-Health Systems; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hare RD. The Hare Psychopathy Checklist–Revised. 2. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Multi-Health Systems; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Harpur TJ, Hare RD. Assessment of psychopathy as a function of age. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:604–609. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.4.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harpur TJ, Hare RD, Hakstian AR. Two-factor conceptualization of psychopathy: Construct validity and assessment implications. Psychological Assessment. 1989;1:6–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hart SD, Hare RD. Discriminant validity of the Psychopathy Checklist in a forensic psychiatric population. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;53:211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Hathaway SR, Monachesi ED. Analyzing and predicting juvenile delinquency with the MMPI. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Hemphill JF, Hart SD, Hare RD. Psychopathy and substance use. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1994;8:169–190. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks BM, Markon KE, Patrick CJ, Krueger RF, Newman JP. Identifying psychopathy subtypes on the basis of personality structure. Psychological Assessment. 2004;16:276–288. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.3.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudspeth WJ, Pribram KH. Psychophysiological indices of cerebral maturation. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 1992;12:19–29. doi: 10.1016/0167-8760(92)90039-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hur YM, McGue M, Iacono WG. Unequal rate of monozygotic and like-sex dizygotic twin birth. Evidence from the Minnesota Twin Family Study. Behavior Genetics. 1995;25:337–340. doi: 10.1007/BF02197282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Carlson SR, Taylor J, Elkins IJ, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of substance use disorders: Findings from the Minnesota Twin Family Study. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:869–900. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, McGue M. Minnesota Twin Family Study. Twin Research. 2002;5:482–487. doi: 10.1375/136905202320906327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:12–19. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpman B. On the need for separating psychopathy into two distinct clinical types: Symptomatic and idiopathic. Journal of Criminology and Psychopathology. 1941;3:112–137. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM–IVdisorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM–III–Rpsychiatric disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Hicks BM, Patrick CJ, Carlson SR, Iacono WG, McGue M. Etiologic connections among substance dependence, antisocial behavior, and personality: Modeling the externalizing spectrum. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:411–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin HS, Culbane KA, Hartmann J, Evankovich K, Mattson AJ. Developmental changes in performance on tests of purported frontal lobe functioning. Developmental Neuropsychology. 1991;7:377–395. [Google Scholar]

- Lilienfeld SO. Conceptual problems in the assessment of psychopathy. Clinical Psychology Review. 1994;14:17–38. [Google Scholar]

- Lilienfeld SO. Methodological advances and developments in the assessment of psychopathy. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1998;36:99–125. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)10021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilienfeld SO, Andrews BP. Development and preliminary validation of a self-report measure of psychopathic personality traits in noncriminal populations. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1996;66:488–524. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6603_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilienfeld SO, Skeem JL. Psychometric properties of self-report psychopathy measures; Paper presented at the 2004 American Psychology-Law Society Annual Conference; Scottsdale, AZ. 2004. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- Lykken DT. The antisocial personalities. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR. Early identification of chronic offenders: Who is the fledgling psychopath? Psychological Bulletin. 1996;120:209–234. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.120.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR. Early identification of the fledgling psychopath: Locating the psychopathic child within the current nomenclature. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:566–575. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.4.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR. Psychopathy from the perspective of the five-factor model of personality. In: Costa PT, Widiger TA, editors. Personality disorders and the five-factor model of personality. 2. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 325–348. [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, Gudonis L. The development of psychopathy. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:381–407. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord W, McCord J. The psychopath: An essay on the criminal mind. Princeton, NJ: Van Nostrand; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Bacon S, Lykken DT. Personality stability and change in early adulthood: A behavioral genetic analysis. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:96–109. [Google Scholar]

- McHoskey JW, Worzel W, Szyarto C. Machiavellianism and psychopathy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:192–210. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.1.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JD, Lynam DR, Widiger TA, Leukefeld C. Personality disorders as extreme variants of common personality dimensions: Can the five-factor model adequately represent psychopathy? Journal of Personality. 2001;69:253–276. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review. 1993;100:674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC, Boker SM, Xie G, Maes HH. Mx: Statistical modeling [Computer software] Richmond: Virginia Commonwealth University, Department of Psychiatry; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC, McArdle JJ. Structured latent growth curves for twin data. Twin Research. 2000;3:165–177. doi: 10.1375/136905200320565454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick CJ. Emotion and psychopathy: Startling new insights. Psychophysiology. 1994;31:319–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1994.tb02440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick CJ. Emotional processes in psychopathy. In: Raine A, Sanmartin J, editors. Violence and psychopathy. New York: Kluwer Academic; 2001. pp. 57–77. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick CJ. Getting to the heart of psychopathy. In: Yuille JC, Herves H, Howell T, editors. Psychopathy in the third millennium: Research and practice. New York: Academic Press; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick CJ, Bradley MM, Lang PJ. Emotion in the criminal psychopath: Startle reflex modulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:82–92. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick CJ, Curtin JJ, Tellegen A. Development and validation of a brief form of the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment. 2002;14:150–163. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.14.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick CJ, Edens JF, Poythress NG, Lilienfeld SO. Manuscript submitted for publication. 2005. Further evidence for two distinct facets of psychopathy in the domain of self-report. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick CJ, Zempolich KA, Levenston GK. Emotionality and violence in psychopaths: A biosocial analysis. In: Raine A, Farrington D, Brennan P, Mednick SA, editors. The biosocial bases of violence. New York: Plenum Press; 1997. pp. 145–161. [Google Scholar]

- Poythress NG, Edens JF, Lilienfeld SO. Criterion-related validity of the Psychopathic Personality Inventory in a prison sample. Psychological Assessment. 1998;10:426–430. [Google Scholar]

- Reardon ML, Lang AR, Patrick CJ. Antisociality and alcohol problems: An evaluation of subtypes, drinking motives, and family history in incarcerated men. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2002;26:1188–1197. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000023988.43694.FE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. The kids are alright: Growth and stability in personality development from adolescence to adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81:670–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, DelVecchio WF. The rank-order consistency of personality from childhood to old age: A quantitative review of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:3–25. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Walton KE, Viechtbauer W. Patterns of mean-level change in personality traits across the life course: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:1–25. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins RW, Fraley RC, Roberts BW, Trzesniewski KH. A longitudinal study of personality change in young adulthood. Journal of Personality. 2001;69:617–640. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.694157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salekin RT, Neumann CS, Leistico AR, DiCicco TM, Duros RL. Psychopathy and comorbidity in a young offender sample: Taking a closer look at psychopathy’s potential importance over disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:416–427. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.3.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Laub JH. Understanding variability in lives through time: Contributions of life-course criminology. Studies on Crime and Crime Prevention. 1995;4:143–158. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Laub JH. A life-course theory of cumulative disadvantage and the stability of delinquency. In: Thornberry TP, editor. Developmental theories of crime and delinquency: Advances in criminological theory. Vol. 7. New Brunswick: Transactions Publishers; 1997. pp. 133–161. [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval AR, Hancock D, Poythress NG, Edens JF, Lilienfeld SO. Construct validity of the Psychopathic Personality Inventory in a correctional sample. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2000;74:262–281. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA7402_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segalowitz SJ, Davies PL. Charting the maturation of the frontal lobe: An electrophysiological strategy. Brain and Cognition. 2004;55:116–133. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2626(03)00283-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel O. Personality development in adolescence. In: Wolman BB, Stricker G, Ellman SJ, Keith-Spiegel P, Palermo DS, editors. Handbook of developmental psychology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1982. pp. 537–548. [Google Scholar]

- Skeem JL, Poythress N, Edens JF, Lilienfeld SO, Cale EM. Psychopathic personality or personalities? Exploring potential variants of psychopathy and their implications for risk assessment. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2003;8:513–546. [Google Scholar]

- Smith SS, Newman JP. Alcohol and drug abuse-dependence disorders in psychopathic and nonpsychopathic criminal offenders. Journal of Abnormal Personality. 1990;99:430–439. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.99.4.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell ER, Thompson PM, Holmes CJ, Jernigan TL, Toga AW. In vivo evidence for post-adolescent brain maturation in frontal and striatal regions. Nature Neuroscience. 1999;2:859–861. doi: 10.1038/13154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E. Clinical criteria for psychiatric diagnosis and DSM–III. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1975;131:1187–1197. doi: 10.1176/ajp.132.11.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Bentler PM. Stability and change in personality: A longitudinal study from early adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Research on Personality. 1986;20:276–291. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J, Loney BR, Bobadilla L, Iacono WG, McGue M. Genetic and environmental influences on psychopathy trait dimensions in a community sample of male twins. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:633–645. doi: 10.1023/a:1026262207449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tellegen A. Manual for the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Verona E, Hicks BM, Patrick CJ. Psychopathy and suicidality in female offenders: Mediating influences of personality and abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;73:1065–1073. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verona E, Patrick CJ, Joiner TE. Psychopathy, antisocial personality, and suicide risk. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:462–470. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.3.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viding E, Blair JR, Moffitt TE, Plomin R. Evidence for substantial genetic risk for psychopathy in 7-year-olds. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward MR, Benning SD, Patrick CJ. Estimating psychopathy facets from normal personality in female offenders: Criterion-related validity; Poster presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychology and Law Society; Scottsdale, AZ. 2004. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- Webster MJ, Weickert CS, Herman MH, Kleinman JE. BDNF mRNA expression during postnatal development, maturation, and aging of the human prefrontal cortex. Developmental Brain Research. 2002;139:139–150. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00540-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widiger TA, Lynam DR. Psychopathy as a variant of common personality traits: Implications for diagnosis, etiology, and pathology. In: Millon T, editor. Psychopathy: Antisocial, criminal, and violent behavior. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. pp. 171–187. [Google Scholar]