Abstract

Keratin intermediate filaments (KIFs) form cytoskeletal KIF networks that are essential for the structural integrity of epithelial cells. However, the mechanical properties of the in situ network have not been defined. Particle-tracking microrheology (PTM) was used to obtain the micromechanical properties of the KIF network in alveolar epithelial cells (AECs), independent of other cytoskeletal components, such as microtubules and microfilaments. The storage modulus (G′) at 1 Hz of the KIF network decreases from the perinuclear region (335 dyn/cm2) to the cell periphery (95 dyn/cm2), yielding a mean value of 210 dyn/cm2. These changes in G′ are inversely proportional to the mesh size of the network, which increases ≈10-fold from the perinuclear region (0.02 μm2) to the cell periphery (0.3 μm2). Shear stress (15 dyn/cm2 for 4 h) applied across the surface of AECs induces a more uniform distribution of KIF, with the mesh size of the network ranging from 0.02 μm2 near the nucleus to only 0.04 μm2 at the cell periphery. This amounts to a 40% increase in the mean G′. The storage modulus of the KIF network in the perinuclear region accurately predicts the shear-induced deflection of the cell nucleus to be 0.87 ± 0.03 μm. The high storage modulus of the KIF network, coupled with its solid-like rheological behavior, supports the role of KIF as an intracellular structural scaffold that helps epithelial cells to withstand external mechanical forces.

Keywords: intermediate filaments, lung alveolar epithelial cells, microrheology, shear stress

Epithelial cells form an indispensable physical barrier to withstand mechanical forces in the surrounding environment. They express cell-type-specific keratin intermediate filament (KIF) proteins, which assemble into complex networks of 10-nm-diameter fibers made up of heterodimers of acidic type I and neutral–basic type II isoforms (1). The primary rat alveolar epithelial cells (AECs) used in this study contain polymers of keratin 8 and 18 (K8/K18) (2). In general, intermediate filaments maintain the mechanical integrity of cells (3–5). For example, K8 knockout mutation is embryonic lethal in the mouse because of hemorrhaging in the liver (6), and mutations in epidermal keratins cause skin-blistering diseases (7).

The eukaryotic cytoskeleton comprises intermediate filaments (IFs), microfilaments (MFs), and microtubules (MTs). All are dynamic structures, undergoing continuous assembly and disassembly in the intracellular environment (8–10). However, KIF assembly differs significantly from MT and MF (8, 9), in that it is nucleotide-independent and that the critical concentration of subunits required for assembly is lower than required for MT and MF. Intermediate filaments resist conditions such as detergent treatment with or without high-salt extraction (11), which disassemble and solubilize the constituent proteins of MT and MF. KIF can be efficiently disassembled only by employing high concentrations of denaturants such as urea (4). We took advantage of the robust nature of the KIF network to measure its mechanical properties, without perturbation by MTs and MFs, in AECs by using particle-tracking microrheology (PTM) (12–14).

We show that there is a correlation between the architecture of the KIF network and the local mechanical properties in AECs, and that shear stress applied across the cell surface causes a structural remodeling of KIF and a substantial increase in the elastic modulus of the network.

Results and Discussion

Shear Stress Alters the Mesh Size of KIF Networks.

To understand the specific structural role of the KIF network, we quantified its mechanical properties in the absence of MT and MF. The intact network can be prepared in AECs by detergent treatment and high-salt extraction (4, 10), conditions that remove membranes, soluble cytoplasmic components, and MT and MF (15). To ensure that the extraction procedure did not alter cell shape and size or significantly affect the three-dimensional organization of the KIF network, AECs were transiently transfected with a construct expressing GFP-K18 (10). Cells were imaged pre- and postextraction by confocal microscopy; neither cell height (total depth of the Z-stack) nor the organization of the KIF was altered [supporting information (SI) Fig. 5].

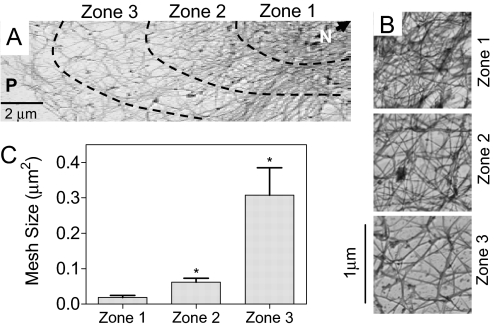

The ultrastructure of the KIF network, now devoid of MT and MF (SI Fig. 6), was examined by electron microscopy (11, 15). Cell images were divided into three zones that did not vary significantly across the cell population (SI Fig. 7A). As shown in Fig. 1A, the mesh size within the KIF network, defined as the mean area of the mesh elements (μm2) (SI Fig. 7 B–D), increased from zone 1 in the perinuclear region (N) to zone 3 near the cell periphery (P). Mesh sizes in zones 1, 2, and 3 (Fig. 1B) were 0.02 μm2, 0.06 μm2, and 0.3 μm2, respectively (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Mesh size distribution of the KIF network in control primary rat AECs. (A) Representative transmission electron micrograph of primary rat AECs, showing in situ KIF network distribution from the nucleus (N) to the periphery (P). Images were obtained by using the platinum replica technique. (B) High-magnification images of the KIF network in each of the three zones depicted in A. (C) Mesh sizes in zones 1, 2, and 3 (see Materials and Methods for details). Mesh size decreases from perinuclear region to the cell periphery (mean ± SD, n = 6 cells).

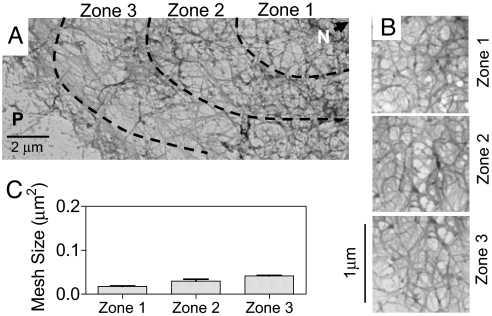

We then analyzed the effect of external mechanical stress on the architecture of KIF. Live AECs were exposed to a fluid shear stress of 15 dyn/cm2 for 4 h. This treatment did not change cell size, shape or areas of the three zones (Figs. 1A and 2A). However, the mesh sizes, especially in zones 2 and 3 (Fig. 2B), were altered significantly [0.02 μm2, 0.03 μm2, and 0.04 μm2 in zones 1, 2, and 3, respectively (Fig. 2C)]. These results demonstrate that even a brief period of exposure to shear stress induces a remarkably homogenous distribution of mesh size across the cell.

Fig. 2.

Mesh size distribution of the KIF network in primary rat AECs subjected to shear stress. (A) Representative transmission electron micrograph of primary rat AECs after shear stress (15 dyn/cm2 for 4 h), showing in situ KIF network distribution from the nucleus (N) to the periphery (P). Images were obtained by using the platinum replica technique. (B) High-magnification images of the KIF network in each of the three zones depicted in A. (C) Mesh sizes within zones 1, 2, and 3. Mesh size is more homogeneous across the cell compared with static control (mean ± SD, n = 6 cells).

Mechanical Properties of the KIF Network.

The mechanical properties of the KIF network were measured by PTM (12), after the microinjection of fluorescent microspheres into AECs. The microsphere diameter must be greater than the mesh size of the KIF network so that they are physically constrained when embedded in it (16). Based on the measured meshwork sizes (see Fig. 1), 0.2-μm and 0.5-μm PEG-coated microspheres were used to prevent nonspecific adherence of the microspheres (SI Fig. 8). Confocal microscopy was used (24 h postinjection) to demonstrate that the microspheres were located within the KIF network (SI Fig. 9). Because other cytoplasmic components were removed during the preparation of the KIF network, the movement of the embedded microspheres were driven solely by Brownian motion. Meeting this condition was essential for calculating the mechanical properties of the network (14).

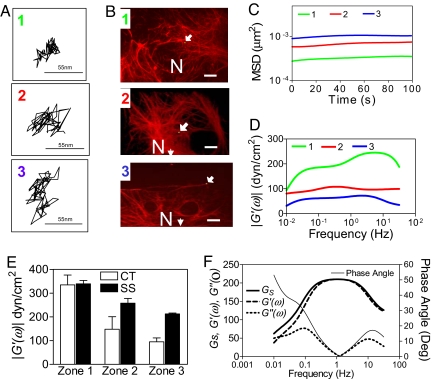

Tracking the displacements of microspheres was the first step in determining the mechanical properties of the KIF network (Fig. 3 A and B). The mean squared displacements (MSDs) of the microspheres were then transformed mathematically into viscoelastic moduli (12, 13). Our results show that the MSDs (Fig. 3C) increase whereas the storage moduli (G′) (Fig. 3D) decrease from zone 1 to zone 3. Specifically, at a frequency of 1 Hz, the mean storage moduli in zones 1, 2, and 3, were 335 ± 41 dyn/cm2 (n = 12), 148 ± 53 dyn/cm2 (n = 11), and 95 ± 16 dyn/cm2 (n = 14) (Fig. 3E). It is interesting to note that the G′ values in zones 2 and 3 exhibit much frequency dependence, whereas zone 1 shows an increase with frequency. Although a specific explanation of this observation is beyond the scope of this study, we speculate that a greater compliance within zone 1 at low frequencies suggests a shear-thinning response in this region. It is notable that G′ values are related inversely to the mesh size of the KIF network (R2 = 0.96 for G′α 1/ξ) (Figs. 1 and 3). These findings demonstrate that there is a relationship between G′ and the in situ KIF network mesh size.

Fig. 3.

Micromechanical properties of the KIF network in AECs. (A) Trajectories of the centroids of the fluorescent PEG-coated microspheres located in zones 1, 2, and 3 of an in situ KIF network in three different AECs (arrows show location of green microsphere) subsequently immunostained (B) with anti-K8/K18 antibodies (red) (scale bars, 10 μm). Frequency-dependent MSD (C) and storage moduli |G′(ω)| (D) of microspheres within zone 1 (n = 11), zone 2 (n = 12), and zone 3 (n = 14). (E) Mean storage moduli at frequency of 1 Hz computed from all microspheres (n = 37) in zones 1, 2, and 3 of rat primary AECs under static control (CT) and shear stress (SS) conditions. (F) Viscoelastic spectrum (Gs), frequency-dependent storage moduli |G′(ω)|, loss moduli |G″(ω)|, and phase angles [δ(ω) = Tan−1(G″(ω)/G′(ω))] of the in situ KIF network. All quantities are computed from ensemble average MSD for all microspheres within all zones of primary rat AECs.

Although the storage modulus in zone 1 remains unaltered after shear stress (335 ± 14 dyn/cm2), significant increases to 240 ± 20 dyn/cm2 and 209 ± 4 dyn/cm2 were observed in zones 2 and 3 of the KIF network (Fig. 3E). When compared with static controls, this translates into a 40% increase in the mean G′ in the shear-stressed AECs.

The average MSDs of all microspheres in all zones of cells were used for computing the viscoelastic spectrum (GS), storage (G′), and loss (G″) moduli of KIF networks (Fig. 3F). The latter two show strong frequency dependence (Fig. 3F). The storage modulus (G′) describes the propensity of the KIF network to store energy when deformed by mechanical stresses, whereas the phase angle [δ = Tan−1(G″/G′)] is a measure of the viscous damping of the KIF network. At a frequency of 1 Hz, G′ = 210 dyn/cm2, G″ = 5dyn/cm2 and δ = 1.5°. The low-phase angles suggest that the KIF network is highly elastic over a range of frequencies. It is important to note that a frequency of ≈1 Hz is biologically relevant for alveolar epithelial cells. The average respiratory rate is ≈15 breaths per minute or 0.25 Hz. Patients with acute lung injury are often placed on a mechanical ventilator that subjects the lung to repetitive opening and closing of the fluid-filled alveoli that generates significant shear stress forces (17); based on the ventilator settings, the average rate is ≈0.5 Hz.

The PTM method for determining the storage modulus, G′, of the KIF network was validated by measuring the deflection of the nucleus before and after shear stress. Theoretically, the deflection of the nucleus is a function of G′ (18) and can be computed as:

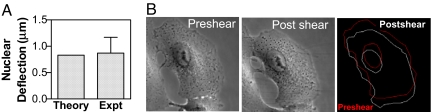

The height of AECs in vivo, ≈7.5 μm (19), is similar to the GFP-K18 expressing AECs in culture, as measured from confocal Z-stacks (SI Fig. 5). Using the value of G′ (334 dyn/cm2) in the perinuclear KIF network (Fig. 1, zone 1), we computed the instantaneous deflection of the nucleus for an imposed shear stress of 30 dyn/cm2 to be 0.83 μm (Fig. 4A). Deflection of the nucleus was then determined experimentally. AECs were subjected to a shear stress of 30 dyn/cm2 for 2 min and deflection of the nucleus relative to the centroid of the cell was determined before and after shearing (Fig. 4B). The experimentally induced nuclear deflection was 0.87 ± 0.3 μm (mean ± SD, n = 6), essentially that of the theoretically calculated value (0.83 μm; above). These results seem to validate the G′ of 335 dyn/cm2 for the KIF network, measured by the PTM method.

Fig. 4.

Predicting shear-induced deflection of the AECs cell nucleus from PTM measurements. Comparison of the nuclear deflection values for AECs exposed to shear stress (30 dyn/cm2) determined from PTM measurement of storage modulus (theory) (A) and from experimental measurement of nuclear deflection (expt) (B) from phase-contrast images of AEC pre- and postshear stress. Experimental nuclear deflection is measured from the deflection of AEC nuclear centroid relative to cellular centroid (see Materials and Methods for details). Cell and nuclear outline used to compute the respective centroids are also shown (far right). Measured value of 0.87 ± 0.3 μm (mean ± SD; n = 6 cells) closely matches the computed nuclear deflection of 0.83 μm derived from PTM measurements.

The storage modulus of the KIF networks in zone 1 in AECs is 335 dyn/cm2 (Fig. 1), which is ≈70 times higher than that measured for in vitro reconstituted KIF suspensions (Table 1) (20). A possible explanation for this discrepancy may be that cross-linking proteins might influence the storage moduli of the biopolymer network (21, 22), but other posttranslational modifications of keratin cannot be excluded. As shown in Table 1, the storage modulus of biotinylated F-actin solutions increases 100-fold when avidin is added. Similar effects may take place in the K5/K14 IF networks in the cornified envelope of skin, where keratin cross-linkers filaggrin and trichohyalin are expressed (23). Another possibility is that transglutaminase (TG), colocalized with keratin (24), might play a role either as a scaffold to support the keratin filaments by noncovalent associations (25–27) or by covalent cross-linking of the structure, similar to reactions occurring during the formation of cornified envelope (28). Cross-linking of KIF in epithelial cells of the skin through Nε-(γ-glutamyl)lysine bridges has been shown to increase their stability (29). In a recent review article by Panorchan et al. (30) the authors compare the PTM-measured mechanical properties of intact cells on depolymerization of the MT and/or MF networks. The authors suggest that MT and MF networks contribute 90 dyn/cm2 and 80 dyn/cm2, respectively, to a bulk storage modulus of 140 dyn/cm2 of mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF). This study and another PTM study by Valentine et al. (16) suggest that MT and MF networks have an order-of-magnitude contribution to the bulk elasticity of the cell similar to those measured for KIF in our study. It must be noted that interpretation of PTM measurements in intact live cells is complicated by the interdependence of cytoskeletal networks through cross-links and the contribution of ATP hydrolysis by enzymes and molecular motors to the movement of microspheres within live cells. However, measurements of intact microfilament and microtubule networks is limited to in vitro reconstituted meshworks that do not preserve the cellular architecture of the MT and MF.

Table 1.

Comparison of mechanical properties of biopolymer networks

Although specific cross-linking elements associated with the K8/K8 IF in AECs have yet to be identified (31), it is of interest to consider their potential impact on the storage modulus of the KIF by estimating the theoretical G′ ∼ κB2/kBTξ2lc3 for cross-linked polymer networks (see SI Methods for details) (21). The values for κB (bending rigidity) and lc (distance between cross-links) can be derived from the literature (32) and ξ (mesh size) is derived from Fig. 1, zone 1. For a 100% cross-linked KIF network the G′ is calculated to be 320,000 dyn/cm2, whereas a 10% cross-linked network is predicted to have a G′ of 320 dyn/cm2. Therefore, G′ values for KIF networks could strongly depend on the extent of cross-linking (measured by “lc”), which in turn depends on the mesh size (ξ). Hence, differences between the PTM-measured values for G′ in the in situ KIF networks (see Fig. 3) and the G′ values for in vitro reconstituted KIF networks are likely to be attributable to a combination of differences in mesh size and degrees of cross-linking.

The heterogeneity of the KIF network mesh size and corresponding G′ values reflect different microenvironments within AECs. Because the measured G′ of the KIF cytoskeleton around the nucleus accurately predicts the shear-stress-induced deflection of the nucleus (Fig. 4), the perinuclear KIF network must contribute significantly to the elasticity of live cells. The decrease in G′ values from the nucleus to the cell periphery (Fig. 2, from zone 1 to zone 3) would augment cellular plasticity at the periphery and facilitate cell motility. The cell periphery is a highly dynamic region that undergoes continuous reorganization during wound healing, cell division, and cortical flow (9). In contrast, the protuberant nucleus of AECs (33, 34) may need to be protected against mechanical forces. Finally, the architecture of the KIF network is dramatically altered by shear stress (Fig. 2) into a structure of homogeneous mesh size from the nucleus to the cell periphery. The mean G′ of the KIF cytoskeleton in shear-stressed cells is 40% higher than that under static control conditions, suggesting an important protective response that would enable the cells to withstand mechanical forces with minimal deformation. The structural support role of KIF networks becomes evident in disease conditions, such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), wherein the loss of the mechanical integrity of the lung epithelium results in flooding of lung airspaces with plasma, impaired gas exchange, and consequent patient mortality (35). Mechanical ventilation of patients with ARDS improves gas exchange but results in harmful shear and stretch forces within the lung that must be borne by the lung epithelial cells (36, 37). Shear stress on lung airways during pathological conditions range from 5 dyn/cm2 to 50 dyn/cm2 (17). Hence in this study we used a shear stress of 15–30 dyn/cm2 to examine the structural changes in the KIF network to approximate the in vivo pathophysiologic conditions. However, these shear stresses are far greater than physiological levels [no shear stress for normal AEC and 5–7 dyn/cm2 on endothelial cells (38)]. The thickness of the human AEC nucleus is ≈7.5 μm, whereas the average thickness of the entire cell is ≈0.36 μm (19). The AEC nucleus protrudes into the alveolus and is vulnerable to damage from external mechanical forces. For a shear stress of 50 dyn/cm2, the KIF cytoskeleton around the nucleus with a G′ ≈334 dyn/cm2 (measured in this study), would restrain nuclear deflection to ≈1 μm [or 1.5% the length of human AEC (19)], thereby minimizing cell injury.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and Culture of Alveolar Epithelial Cells.

Rat alveolar epithelial type II cells (AECs) were isolated from pathogen-free male Sprague–Dawley rats (200–225 g), as described in ref. 2. In brief, the lungs were perfused by the pulmonary artery and lavaged and digested with elastase (30 units/ml, Worthington Biochemical). AECs were purified by differential adherence to IgG-pretreated dishes, and cell viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion (>95%). Cells were suspended in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% FBS with 2 mM l-glutamine, 40 μg/ml gentamicin, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin and placed in culture for 2 days before the start of all experimental conditions. Cells were incubated in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air at 37°C.

Shear Stress.

AECs were grown either on coverslips or glass slides and exposed to shear stress (15 dyn/cm2 for 4 h) in the temperature-controlled Bioptechs Focht Chamber System (FCF2, Bioptechs) or FlexCell Streamer Device (FlexCell International), respectively.

Mesh Size Distribution of the KIF Network.

AECs were grown on glass slides and exposed to either static conditions or to continuous laminar shear stress (15 dyn/cm2 for 4 h) by using a FlexCell Streamer Device (FlexCell International). Ultrastructural observations of cytoskeletal preparations were performed as described in ref. 39. For preservation of IFs, cells on coverslips were extracted with PEM buffer (100 mM Pipes, pH 6.9, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA) containing 1% Triton X-100, 0.4 M NaCl, 4% PEG, 1 mg/ml DNase 1 (Sigma–Aldrich) for 10 min (room temperature). To remove any residual actin, all preparations were treated with recombinant gelsolin NH2-terminal domain. Cells were then fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde, stained with 0.2% uranyl acetate, and processed by critical point drying followed by rotary shadowing with platinum and carbon (39). Replicas were removed from the coverslips and transferred to copper grids as described in ref. 39 for observation by transmission electron microscopy.

Image analysis was carried out by using a Matlab program (Mathworks). In brief, images were contrast enhanced, thresholded, and segmented to identify the individual mesh elements (see SI Fig. 7 B–D). The cell was divided into three zones (1, 2, and 3) of equal length in the radial directions (cell nucleus to periphery) (SI Fig. 7A). The mesh size was computed as average area of the individual mesh elements in each zone. The Matlab program identified ≈100 mesh elements per image; images were acquired from each zone for six individual AECs. Mesh size was computed in three distinct regimes, namely zones 1, 2, and 3. The length of the individual zones was measured by using Metamorph software.

Microsphere Surface Chemistry.

Yellow-green carboxylate-modified polystyrene microspheres (0.2 μm and 0.5 μm) from Molecular Probes were coated with PEG to render them inert (16). The microspheres were immersed in a 1 mg/ml solution of PEG (2 kDa) conjugated poly-l-lysine (Surface Solutions) for 4 h, at 22°C, washed three times with PBS, filtered, and stored at 4°C. PEG-coated microspheres were used within 48 h. Efficiency of coating was confirmed by using the method outlined in ref. 16 (see SI Methods).

Preparation of KIF Networks with Embedded Microspheres.

AECs grown on 22 mm × 22 mm coverslips for 2 days were placed in microinjection medium (DMEM containing 20% FBS with 2 mM l-glutamine, 40 μg/ml gentamicin, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 23 mM Hepes, and 5 μg/ml of insulin-transferrin-sodium-selenite) for 30 min at 37°C. PEG-coated microspheres were diluted to a final concentration 6 × 107 microspheres per ml in PBS; either 0.2-μm and 0.5-μm microspheres were injected into AECs by using a FemtoJet microinjector (Eppendorf) mounted on a Leica fluorescence microscope (Leica). Needles for microinjection were pulled by using a Flaming/Brown Micropipette Puller (Sutter Instruments). Microspheres were injected into ≈100 cells per coverslip. AECs were allowed to recover in microinjection medium for 24 h postinjection. KIF networks were prepared by treating AECs with PEM buffer (100 mM Pipes, pH 6.9, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA) containing 1% Triton X-100, 0.4 M NaCl, 4% PEG, 1 mg/ml DNase 1 (Sigma–Aldrich) for 10 min (room temperature) (15). F-actin was disassembled by treatment with gelsolin (0.2 mg/ml) in buffer G (50 mM Mes-KOH, pH 6.3, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgCl2, and 0.5 mM DTT), followed by three washes with PBS. Cells were then incubated with a mixture of K8 and K18 monoclonal antibodies (1:100, Research Diagnostics) for 45 min at 37°C, washed with PBS, and incubated with GAM-Alexa 568 secondary antibody (1:200) for 30 min. Immediately after the preparation of IF networks the coverslips were mounted on glass slides in 20 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.4) with protease inhibitors (phenyl methyl sulfonate, 100 μg/ml; leupeptin, 2 μg/ml; TPCK, 100 μg/ml), a ≈1-mm spacer was placed between coverslip and slide, sealed with Valap, and allowed to equilibrate at 37°C for 60 min before being mounting on the microscope stage where they were allowed to equilibrate for an additional 30 min.

Image Acquisition.

Images of the yellow-green fluorescent microspheres and the red fluorescent KIF networks were acquired by using a Yokogawa Spinning Disk (Perkin–Elmer) fitted on a Nikon TE2000-U inverted fluorescence microscope equipped with a Hamamatsu Camera. The entire microscope was enclosed in a Plexiglas incubator, which is maintained at 37°C with minimum vibration (Cube1, Redbox Direct). The microscope was equipped with a piezo-electric stage controller to allow precise control of microscope focus during imaging. The locations of microspheres within KIF networks were confirmed by acquiring Z stacks of red (keratin) and green (microsphere) fluorescence. Three-dimensional reconstruction of Z-stacks was carried out by using Volocity software (Improvision) to establish the presence of keratin filaments around the microsphere. The piezo-electric stage controller provides accurate submicrometer readout of the stage location and was used to quantify the distance between the microsphere and the coverslip. Only microspheres that were at least 10 microsphere diameters from the coverslip and that appeared to be encapsulated within KIF were used for image analysis. Images of the microsphere were acquired by using Metamorph Software in stream acquisition mode at the rate of 30 ms per frame for 200 s (6,000 successive images).

Statistical Analysis.

Comparison of the data was carried out by using the unpaired Student's t test. One-way ANOVA with Tukey's test was used to analyze the data. P < 0.05 values were considered significant.

Particle-Tracking Microrheology (PTM): Technique and Analysis.

The local mechanical properties of the KIF network were measured by using the PTM technique (12). PTM is used to measure the local micromechanical properties of a biopolymer network by tracking the movement of fluorescent microspheres embedded within the network; the motion of microspheres, whose diameter is greater than the mesh size of the polymer network, are physically constrained by the surrounding polymer. Thus, the distance traveled by the microsphere over a given time interval (measured by MSD; see below) is a measure of the viscoelasticity of the surrounding polymer. The movement of microspheres is tracked by using a fluorescence microscope with high temporal (≈10 ms) and spatial (≈10 nm) resolution. The MSD of the microsphere over various time scales is used to obtain the viscoelastic properties of the surrounding polymer meshwork as elaborated below (12, 13).

Description of Rheological Variables.

The mean squared displacement (MSD) of the microsphere (measured in μm2), is the square of the ensemble average distance moved by the microsphere in time lag “τ.” The storage modulus |G′(ω)| (measured in dyn/cm2) is a measure of the stiffness (stress per unit strain) of the KIF network. The loss modulus |G″(ω)| (measured in dyn/cm2) is a measure of viscosity of the KIF network. The phase angle is a measure of the rheological behavior of the viscoelastic network, it compares the loss modulus with the storage modulus and is quantified as δ(ω) = Tan−1(G″(ω)/G′(ω)). For G″(ω) ≫ G′(ω) the network exhibits mostly viscous behavior. For a viscous liquid G″(ω)/G′(ω) → ∞ and δ(ω) = 90°. For G″(ω) ≪ G′(ω), the network exhibits mostly elastic behavior. For an elastic solid, G″(ω)/G′(ω) → 0 and δ(ω) = 0°. For a viscoelastic network such as the KIF network, the storage modulus (G′(ω)), loss modulus (G″(ω)), and phase angle all depend on the frequency (measured in Hz units). Frequency is defined as the inverse of time lag τ. The viscoelastic spectrum (Gs) is a mathematical entity that does not have a direct physical analog. Simply stated, the viscoelastic spectrum can be thought of as the effective viscosity of the volume surrounding the bead (which includes the biological buffer and KIF) over a range of frequencies (for detailed description, see SI Methods).

Image Processing.

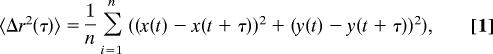

The intensity-weighted centroid of the fluorescent microsphere was located to subpixel resolution by using a custom Matlab program. The centroid locations were used to compute the MSD of the microsphere centroid

|

where x(t) and y(t) are the x and y locations of the centroid at time t.

Local Mechanical Properties of the KIF Network.

MSDs were used to compute the local mechanical properties of the KIF network by using the methods outlined in Mason et al. (12). In brief, assuming that the KIF network around the fluorescent microsphere can be treated as an isotropic, incompressible continuum, the viscoelastic spectrum G(s) can be calculated from the unilateral Laplace transform of the MSD by using the generalized Stokes–Einstein equation (13)

where s is frequency, kB is the Boltzmann's constant, a is the radius of the fluorescent microsphere, and T is the temperature (37°C). The Laplace transform is computed numerically as outlined in Mason et al. (12). From G(s), Gr(t) is computed by using the canonical method of relaxation spectra (40). Finally, G′(ω) and G″(ω), which are the storage and loss moduli, are computed as the unilateral cosine and sine transforms of Gr(t) (12).

Determination of Nuclear Deflection Before and After Shear Stress.

AECs were cultured on 40-mm coverslips for 3 days. Cells were exposed to shear stress (30 dyn/cm2 for 2 min) in the temperature-controlled Focht Chamber System (FCF2, Bioptechs) mounted on a LSM 510 microscope (Zeiss). Phase-contrast images of AECs were acquired before and after shear stress. Outlines of the entire cell and nucleus were sketched within Metamorph software (Molecular Devices) and the centroid of the nucleus and the entire cell was determined by Metamorph software. Nuclear deflection after shear stress was computed as the vector subtraction of the change in nuclear centroid relative to the cellular centroid (18).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants NHLBI P01-HL71643, NHLBI HL07910, and NIGMS GM36806.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest statement.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0710728105/DC1.

References

- 1.Schweizer J, et al. New consensus nomenclature for mammalian keratins. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:169–174. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200603161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ridge KM, et al. Keratin 8 phosphorylation by protein kinase C δ regulates shear stress-mediated disassembly of keratin intermediate filaments in alveolar epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30400–30405. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504239200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuchs E, Cleveland DW. A structural scaffolding of intermediate filaments in health and disease. Science. 1998;279:574–579. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herrmann H, Aebi U. Intermediate filaments: Molecular structure, assembly mechanism, and integration into functionally distinct intracellular Scaffolds. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:749–789. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldman RD, Khuon S, Chou Y, Opal P, Steinert P. The function of intermediate filaments in cell shape and cytoskeletal integrity. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:971–983. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.4.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baribault H, Price J, Miyai K, Oshima RG. Mid-gestational lethality in mice lacking keratin 8. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1191–1202. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.7a.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan Y, et al. A human keratin 14 “knockout”: The absence of K14 leads to severe epidermolysis bullosa simplex and a function for an intermediate filament protein. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2574–2587. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.21.2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waterman-Storer C, Salmon E. Microtubule dynamics: Treadmilling comes around again. Curr Biol. 1997;7:R369–R372. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00177-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pollard T, Borisy G. Cellular motility driven by assembly and disassembly of actin filaments. Cell. 2003;112:453–465. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoon KH, et al. Insights into the dynamic properties of keratin intermediate filaments in living epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:503–516. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.3.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helfand B, Loomis P, Yoon M, Goldman RD. Rapid transport of neural intermediate filament protein. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:2345–2359. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mason T, Ganesan K, van Zanten J, Wirtz D, Kuo S. Particle tracking microrheology of complex fluids. Phys Rev Lett. 1997;29:3282–3285. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mason T, Weitz D. Optical measurements of frequency-dependent linear viscoelastic moduli of complex fluids. Phys Rev Lett. 1995;74:1250–1253. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.74.1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tseng Y, Kole T, Wirtz D. Micromechanical mapping of live cells by multiple-particle-tracking microrheology. Biophys J. 2002;83:3162–3176. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75319-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Svitkina T, Verkhovsky A, Borisy G. Improved procedures for electron microscopic visualization of the cytoskeleton of cultured cells. J Struct Biol. 1995;115:290–303. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1995.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valentine M, et al. Colloid surface chemistry critically affects multiple particle tracking measurements of biomaterials. Biophys J. 2004;86:4004–4014. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.037812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bilek AM, Dee KC, Gaver DP. Mechanism of surface-tension-induced epithelial cell damage in a model of pulmonary airway reopening. J Appl Physiol. 2003;94:770–783. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00764.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boal D. Mechanics of the Cell. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crapo J, Barry B, Gehr P, Bachofen M, Weibel E. Cell number and cell characteristics of the normal human lung. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1982;126:332–337. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1982.126.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamada S, Wirtz D, Coulombe P. The mechanical properties of simple epithelial keratins 8 and 18: Discriminating between interfacial and bulk elasticities. J Struct Biol. 2003;143:45–55. doi: 10.1016/s1047-8477(03)00101-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gardel M, et al. Elastic behavior of cross-linked and bundled actin networks. Science. 2004;304:1301–1305. doi: 10.1126/science.1095087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wachsstock D, Schwarz W, Pollard T. Cross-linker dynamics determine the mechanical properties of actin gels. Biophys J. 1994;66:801–809. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(94)80856-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Candi E, Schmidt R, Melino G. The cornified envelope: A model of cell death in the skin. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:328–340. doi: 10.1038/nrm1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clement S, et al. A transglutaminase-related antigen associates with keratin filaments in some mouse epidermal cells. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;109:778–782. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12340949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lorand L, Dailey JE, Turner PM. Fibronectin as a carrier for the transglutaminase from human erythrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:1057–1059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.4.1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radek JT, Jeong J, Murthy SNP, Ingham KC, Lorand L. Affinity of human erythrocyte transglutaminase for a 42-kDa gelatin-binding fragment of human plasma fibronectin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3152–3156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hang J, Zemskov EA, Lorand L, Belkin AM. Identification of a novel recognition sequence for fibronectin within the NH2-terminal β-sandwich domain of tissue transglutaminase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:23675–23683. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503323200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Candi E, et al. A highly conserved lysine residue on the head domain of type II keratins is essential for the attachment of keratin intermediate filaments to the cornified cell envelope through isopeptide crosslinking by transglutaminases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2067–2072. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steinert PM, Idler WW. Postsynthetic modifications of mammalian epidermal alpha-keratin. Biochemistry. 1979;18:5664–5669. doi: 10.1021/bi00592a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Panorchan P, et al. Probing cellular mechanical responses to stimuli using ballistic intracellular nanorheology. Methods Cell Biol. 2007;83:115–140. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(07)83006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green K, Bohringer M, Gocken T, Jones J. Intermediate filament associated proteins. Adv Protein Chem. 2005;70:143–202. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(05)70006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guzman C, et al. Exploring the mechanical properties of single vimentin intermediate filaments by atomic force microscopy. J Mol Biol. 2006;360:623–630. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams MC. Alveolar type I cells: Molecular phenotype and development. Ann Rev Physiol. 2003;65:669–695. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.West JB, Mathieu-Costello O. Structure, strength, failure and remodeling of the pulmonary blood-gas barrier. Annu Rev Physiol. 1999;61:543–572. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1334–1349. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sznajder JI, Ridge KM, Saumon G, Dreyfuss D. In: Lung Injury Induced by Mechanical Ventilation in Pulmonary Edema. Matthay M, Ingbar D, editors. New York: Dekker; 1988. pp. 413–430. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hubmayr RD. Perspective on lung injury and recruitment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:1647–1653. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2001080-01CP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davies PF. Flow-mediated endothelial mechanotransduction. Physiol Rev. 1995;75:519–560. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.3.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Helfand BT, Mikami A, Vallee RB, Goldman RD. A requirement for cytoplasmic dynein and dynactin in intermediate filament network assembly and organization. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:795–806. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200202027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bird R, Armstrong R, Hassager O. Dynamics of Polymeric Liquids. New York: Wiley; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tseng Y, Kole T, Wirtz D. Micromechanical mapping of live cells by multiple-particle-tracking microrheology. Biophys J. 2002;83:3162–3176. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75319-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamada S, Wirtz D, Coulombe P. The mechanical properties of simple epithelial keratins 8 and 18: Discriminating between interfacial and bulk elasticities. J Struct Biol. 2003;143:45–55. doi: 10.1016/s1047-8477(03)00101-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.