Abstract

The bacterial mechanosensitive channel MscS protects the bacteria from rupture on hypoosmotic shock. MscS is composed of a transmembrane domain with an ion permeation pore and a large cytoplasmic vestibule that undergoes significant conformational changes on gating. In this study, we investigated whether specific residues in the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains of MscS influence each other during gating. When Asp-62, a negatively charged residue located in the loop that connects the first and second transmembrane helices, was replaced with either a neutral (Cys or Asn) or basic (Arg) amino acid, increases in both the gating threshold and inactivation rate were observed. Similar effects were observed after neutralization or reversal of the charge of either Arg-128 or Arg-131, which are both located near Asp-62 on the upper surface of the cytoplasmic domain. Interestingly, the effects of replacing Asp-62 with arginine were complemented by reversing the charge of Arg-131. Complementation was not observed after simultaneous neutralization of the charge of these residues. These findings suggest that the cytoplasmic domain of MscS affects both the mechanosensitive gating and the channel inactivation rate through the electrostatic interaction between Asp-62 and Arg-131.

Introduction

Various types of mechanosensitive (MS) channels are present in sensory cells that detect sound, touch, gravity, and acceleration (1–4). Nonsensory cells also make use of MS channels to monitor their own deformations caused by stretch and osmotic stress. One of the best studied examples is the bacterial MS channel, which opens on hypoosmotic shock to prevent cell lysis (5–10).

Two types of bacterial MS channels, MscS (mechanosensitive channel of small conductance) and MscL (mechanosensitive channel of large conductance), are activated in response to hypoosmotic shock and release small osmolytes from the cell. MscS and MscL are both likely to perceive membrane tensions directly from the lipid bilayer without the need for any accessory proteins (11–13). Additionally, lipid-protein interactions proximal to the surface of the lipid bilayer are important for sensing membrane tensions (14,15). However, the conductance of Escherichia coli MscS is ∼1 nS (11,12), whereas the conductance of MscL is ∼2.5 nS, and MscL opens at membrane tensions almost twice as large as that required to open MscS.

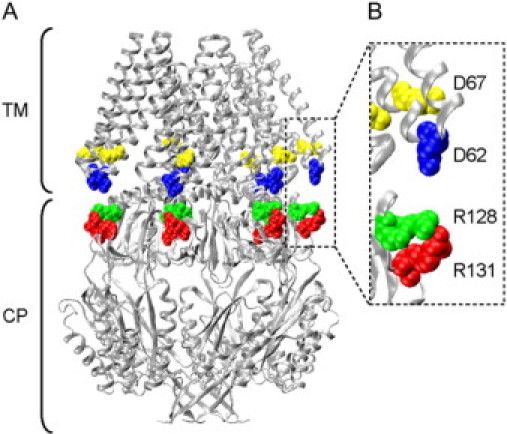

An x-ray crystal structure of MscS, resolved at 3.9 Å, revealed that MscS is a homoheptamer containing three transmembrane helices per subunit (TM1, residues 29–57; TM2, 68–91; and TM3, 96–127) (16,17) (Fig. 1). Each subunit has a molecular mass of ∼30 kDa and consists of 286 amino acids (7). The channel pore is formed by TM3 and has a diameter of 8–11 Å (17). MscS has a weak permeability preference for anions (11,12,18) and shows a pronounced rate of inactivation when the cytoplasmic membrane potential is positive (19).

Figure 1.

The crystal structure of MscS (17). Asp-62, Asp-67, Arg-128, and Arg-131 are colored in blue, yellow, green, and red, respectively, and depicted in a space-filling model. TM and CP represent the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains, respectively. B is expanded view of a part of A. The structure is based on the data set of 2OAU in the Protein Data Bank.

One of the major structural differences between MscS and MscL is that MscS has a large (∼17 kDa) carboxyl-terminal cytoplasmic domain (17). It has been postulated that the carboxyl-terminal domain acts as a molecular prefilter for ion permeation and undergoes a significant conformational change during the transition from the closed to the open state (16,20,21). It is also possible that the carboxyl-terminal domain forms a cytoplasmic gate for the MscS channel (21). However, the mechanism by which the carboxyl-terminal and transmembrane domains affect each other is unknown.

The interaction between the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains is of general interest because many ion channels are regulated by their cytoplasmic domains. Cyclic nucleotide-gated channels bind intracellular cAMP or cGMP at the cytoplasmic domain (22–24). There are potassium and chloride channels whose activity is controlled by the binding of calcium ions to the cytoplasmic regulatory domain (25–27). The activation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator requires phosphorylation of the cytoplasmic regulatory domain and the binding of ATP to the nucleotide-binding domain (28,29). The availability of structural information about MscS makes it an excellent candidate for study. In fact, a molecular dynamic simulation study by Sotomayor and Schulten (30) suggested that Asp-62, which is located in the loop that connects TM1 and TM2, forms a salt bridge with Arg-128, a residue in the upper surface of the cytoplasmic vestibule (Fig. 1 B).

In this study, we examined the role of the electrostatic interaction between the upper surface of the cytoplasmic vestibule and the loop that connects the transmembrane helices. The channel functions of various mutants were assessed through electrophysiology and hypoosmotic shock experiments. In addition to the predicted salt bridge between Asp-62 and Arg-128, the involvement of the neighboring residues (Arg-59, Lys-60, Asp-67, and Arg-131) in the bridge formation was examined. The results indicate the presence of an electrostatic interaction between Asp-62 and Arg-131 that controls the gating sensitivity and the inactivation rate of MscS.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains

E. coli strains PB111 (ΔyggB, ΔrecA) and MJF455 (ΔmscL, ΔyggB::Cm) were used to host MscS expression vectors in patch-clamp and hypoosmotic shock experiments, respectively (7,10). E. coli strain DH5α was used for site-directed mutagenesis.

DNA manipulations

Polyhistidine-tagged MscS was cloned into pB10b as described previously (16). Site-directed mutagenesis was performed by the Mega-primer method. Successful mutagenesis was verified by DNA sequencing on both strands using the CEQ 2000XL DNA Analysis System (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). Constructs were transformed into PB111 or MJF455 by electroporation.

Spheroplast preparation

Patch-clamp experiments were performed on E. coli giant spheroplasts as described previously (31). PB111 cells were grown for 1.5 h in the presence of cephalexin (final concentration 0.06 mg/ml), and MscS expression was subsequently induced for 10 min by the addition of 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside). The cells were harvested and digested by lysozyme (0.2 mg/ml). Spheroplasts were collected by centrifugation.

Electrophysiological recording and data analysis

The channel activity of MscS was examined by the inside-out patch-clamp method as described previously (32). Pipette solutions contained 200 mM KCl, 90 mM MgCl2, 10 mM CaCl2, and 5 mM HEPES (pH 6.0), whereas the bath solution additionally contained 0.3 M sucrose to stabilize the spheroplasts. Currents were amplified using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) and filtered at 2 kHz. Current recordings were digitized at 5 kHz using a Digidata 1322A interface with pCLAMP 9 software (Axon). Negative pressure was applied by syringe-generated suction through the patch-clamp pipette and measured with a pressure gauge (PM 015R, World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL). For the assessment of the inactivation process, pressure was controlled using a High-Speed Pressure Clamp-1 apparatus (HSPC-1; ALA Scientific Instruments, Westbury, NY) (33) following the method of Akitake et al. (19). The pressure was held constant at the lowest pressure at which full activation occurred.

The gating threshold of MscS was determined by fitting a Boltzmann function to the activation curve. The Boltzmann function gives the midpoint of pressure at which half of the MscS are open. The gating threshold of MscL is the pressure at which the first channel opening was observed. The midpoint pressure of MscS activation was normalized by the threshold of MscL and presented as the ‘threshold’ of MscS.

Viability assays

Survival rates after hypoosmotic shock were examined by a method described previously (7,14,15). Expression was induced by the addition of IPTG (1 mM) to MJF455 cells grown to OD600 = 0.15 in minimal medium supplemented with 500 mM NaCl and 50 μg/ml ampicillin. The minimal medium has an osmolarity of 220 mOsm and contains 8.58 g Na2HPO4, 0.87 g K2HPO4, 1.34 g citric acid, 1.0 g (NH4)2SO4, 1 mg thiamine, 48 mg MgSO4, and 2 mg Fe(NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O per liter. After a 1-h incubation, the cells were diluted 1/20 in prewarmed minimal medium with or without 500 mM NaCl. After a 5-min shock, each sample was spread on a plate and cultured at 37°C overnight. The ratio of the number of colony-forming units of cells that experienced osmotic shock (Ndown) to those that did not (Ncontrol) was used to calculate the survival rate (Ndown/Ncontrol). The osmotic shock experiment was carried out three times per mutant.

Biochemical analysis

The level of protein expression was examined by Western blot as described previously (15). Protein expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG for 2 h. The proteins were separated by 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. An antibody against polyhistidine was used to detect the His6-tag at the carboxyl terminus of MscS. In the analysis of the multimer formation of D62C/R128C and D62C/R131C, I2 (1 mM final concentration) was added to all solutions used for sample preparation and hypoosmotic shock; DTT was omitted when I2 was added.

Results

Modification of the charge at residue 62 and the residues nearby

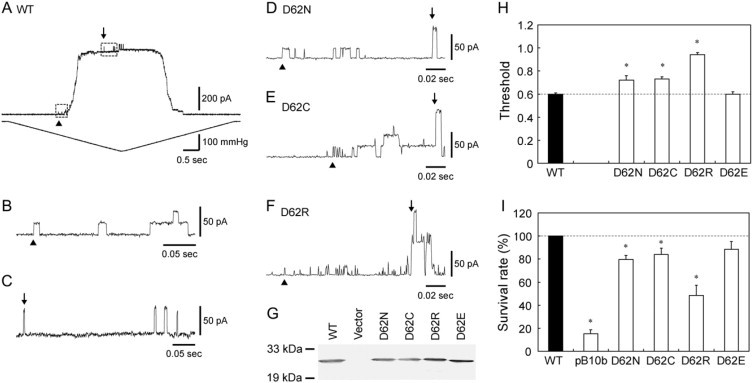

The channel activities of wild-type and mutant MscS were examined by the application of negative pressure through a patch pipette to the inside-out membrane patch of giant spheroplasts expressing MscS. When wild-type MscS was expressed, a channel current with an amplitude of ∼20 pA opened on increasing the negative pressure applied to the patch membrane (arrowhead in Fig. 2, A and B; at −20 mV cytoplasmic potential). From the size of its conductance (∼1 nS), the channel was judged to be MscS. Further increases in the negative pressure opened MscL, which has a conductance of ∼2.5 nS (arrow in Fig. 2, A and C). MscS remained open as long as the pressure was above the threshold. The threshold of MscS is represented by the pressure at which half of the MscS channels in the patch membrane are activated. The midpoint of MscS activation is normalized using the threshold of MscL to compensate for variation resulting from the geometry of the membrane (15). The threshold of wild-type MscS was ∼0.6 (Fig. 2 H).

Figure 2.

Characterization of wild-type MscS (WT) and D62X MscS expressed in ΔmscS cells. (A) The membrane current (top) and the negative pressure applied to the inside-out patch through the patch pipette (bottom). The first opening of the expressed wild-type MscS and endogenous MscL on continuously increasing suction is indicated by arrowheads and arrows, respectively. Cytoplasmic potential was −20 mV. (B and C) Expanded view of the opening of MscS (B) and MscL (C) boxed in panel A. (D–F) Records from the spheroplasts expressing D62N (D), D62C (E), and D62R (F) MscS. (G) Expression of MscS in the membrane. The Western blot against the His-tag at the carboxyl terminus of MscS is shown. (H) Threshold for MscS gating as determined by patch clamp (mean ± SE, n = 5). (I) Effect of hypoosmotic shock on cells expressing MscS or harboring an empty vector (pB10b) (mean ± SE, n = 9). The survival rate was normalized to that of the cells expressing wild-type MscS. The asterisks hereafter indicate that the value is significantly different from that of wild-type MscS (p < 0.05 by t-test).

When the negative charge of Asp-62, which is located in the loop that connects the transmembrane helices, was neutralized by substitution with either asparagine or cysteine, the threshold increased to ∼0.7 (D62N and D62C; Fig. 2, D, E, and H). The D62N and D62C mutant channels closed while the pressure was still above the gating threshold. The introduction of a positive charge by substitution with arginine increased the threshold to 0.94, close to the threshold of MscL (D62R; Fig. 2, F and H). D62R MscS was inactivated even faster and showed only a small number of channel events. On the other hand, when Asp-62 was replaced with a negatively charged amino acid (D62E), the threshold was nearly the same as that of wild-type MscS (Fig. 2 H), and the channel was not inactivated by continuous pressure.

To ensure that the threshold change also occurs in vivo, E. coli cells expressing wild-type and mutant MscS were exposed to hypoosmotic shock. A previous study showed that an increase in the threshold correlates with a decrease in viability (15). Most of the ΔmscLΔmscS cells (MJF455) that harbored an empty vector (pB10b) did not survive on hypoosmotic shock from 500 to 0 mM NaCl, but cells expressing wild-type MscS showed greater viability (Fig. 2 I). The survival rate of cells expressing MscS with a neutral amino acid at position 62 (D62N and D62C) decreased by ∼20%, whereas that of cells expressing MscS with a positive amino acid (D62R) showed a larger decrease. Cells expressing D62E MscS had a survival rate that was not statistically different from that of wild-type MscS. Western blot analysis did not reveal a decrease in protein expression in the mutant forms of MscS (Fig. 2 G). Therefore, it is unlikely that the low survival rate of cells expressing neutral or positive amino acids results from a low level of protein expression.

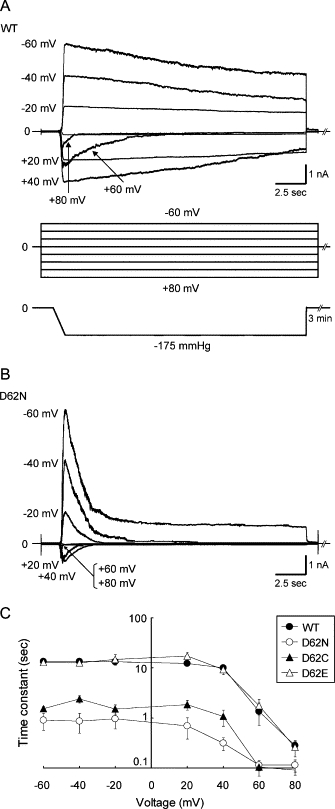

Wild-type MscS exhibits a strong rate of voltage-dependent inactivation under depolarizing conditions (19,34). At cytoplasmic potentials larger than 40 mV, a rapid decrease in current was observed in wild-type MscS (Fig. 3, A and C), consistent with the results from a previous study (19). We examined whether this voltage-dependent inactivation rate was altered in Asp-62 mutants. D62N MscS showed a fast inactivation rate even at negative potentials (Fig. 3, B and C). The inactivation rate at positive potentials was also accelerated. D62C MscS showed a similar rapid inactivation rate (Fig. 3 C). D62R had a threshold close to that of MscL (Fig. 2, F and H) but was inactivated much faster. A quantitative evaluation of the time constant was not possible because of the small number of active channels and the high pressure required to open D62R MscS. On the other hand, the inactivation rate of D62E MscS was approximately the same as wild-type MscS (Fig. 3 C). Inactivation was not caused by an irreversible loss of channel activity, as the number of functional channels did not decrease after each experiment. These observations indicate that modification of the negative charge at position 62 alters both the threshold and inactivation rate of MscS.

Figure 3.

Inactivation of wild-type and D62X MscS expressed in ΔmscSΔmscL cells. (A) Current (top) evoked by suction (bottom) at a cytoplasmic potential ranging from −60 to +80 mV (middle). A rapid decrease in current was observed only in the voltage range from +40 to +80 mV in wild-type MscS. (B) Response of D62N MscS to the same protocol as in A. Rapid inactivation occurred at all voltages examined. (C) The relation between the voltage and the time constant of the inactivation rate obtained by fitting a single exponential function to the current recordings.

To examine whether the observed effect is specific to residue 62, we modified the charge of the nearby residues. Neutralizing (K60N, K60Q) or reversing (K60E) the positive charge of Lys-60 did not change the gating threshold (Fig. 4 A), the inactivation rate (Fig. 4 C), or the survival rate (Fig. 4 B; except for K60E). Neutralizing the positive charge of Arg-59 (R59N) decreased the gating threshold, whereas reversing the charge (R59D) increased it. Neither the survival rate nor the inactivation rate showed a significant change (Fig. 4). Charge neutralization of Asp-67 (D67N) did not alter the channel characteristics. In contrast, reversal of the negative charge (D67R) increased the gating threshold, decreased the survival rate, and enhanced inactivation (Fig. 4). Shifting the position of the negative charge from residue 62 to residue 60 with the K60D/D62K mutation resulted in a phenotype similar to D62R MscS (Fig. 4, A and B), suggesting that a negative charge at residue 62 cannot be replaced by a negative charge at residue 60.

Figure 4.

Effect of mutations at Arg-59, Lys-60, and Asp-67 on the gating threshold (A), the survival rate on hypoosmotic shock (B), and the inactivation rate (C). The experimental conditions are the same as the ones shown in Figs. 2 and 3.

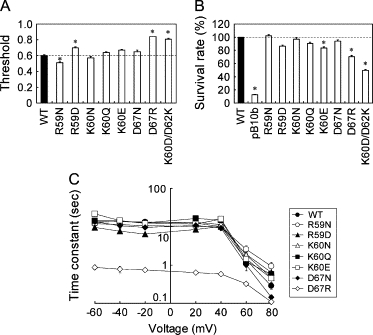

Modification of the positive charges at residues 128 and 131

In the simulation study by Sotomayor and Schulten (30), Asp-62 was found to form an electrostatic interaction with Arg-128 of the neighboring subunit, which is located in the upper surface of the cytoplasmic vestibule. It is also possible that Arg-131, which is located a single helix turn away, interacts with Asp-62 (Fig. 1 B). If the defects in channel function of the Asp-62 mutants are caused by the loss of interaction with Arg-128 or Arg-131, changes in the charge of Arg-128 or Arg-131 would be expected to affect the channel in a similar way.

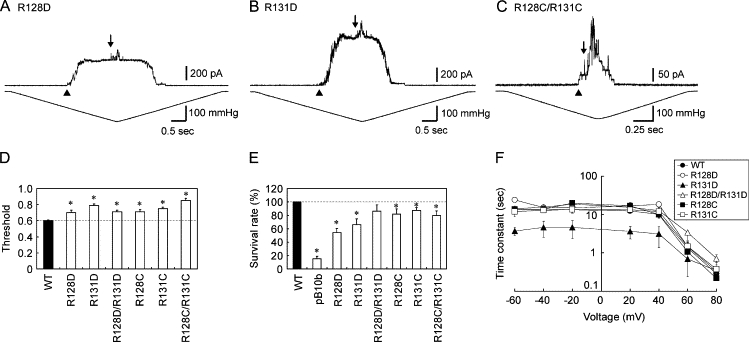

When the positive charge of Arg-128 and/or Arg-131 was replaced with a negative charge (R128D, R131D, or R128D/R131D), the threshold increased to 0.7–0.8 (Fig. 5, A, B, and D). The mutants with a neutral charge at these sites (R128C, R131C, and R128C/R131C) also had elevated thresholds (Fig. 5 D). Of note, R128C/R131C MscS had a threshold as high as that of MscL as in the D62R mutant (Fig. 5, C and D). Consistent with the high threshold, the survival rate on hypoosmotic shock was lower than that of wild-type MscS (Fig. 5 E). However, the inactivation rate was accelerated only in R131D MscS (Fig. 5 F).

Figure 5.

Characterization of MscS with mutations at Arg-128 and Arg-131. (A–C) Current recorded from an inside-out membrane patch from ΔmscS cells expressing R128D (A), R131D (B), or R128C/R131C MscS (C). The arrowheads and arrows indicate the beginning of the opening of MscS and MscL, respectively. (D) Relative threshold of the single and double mutants (mean ± SE). (E) Survival rates of cells expressing MscS or harboring an empty vector (pB10b) when cells were challenged by osmotic shock (mean ± SE). (F) Time constant of the inactivation rate of the Arg-128 and Arg-131 mutants.

Complementation of the mutation at residue 62 and residues 128/131

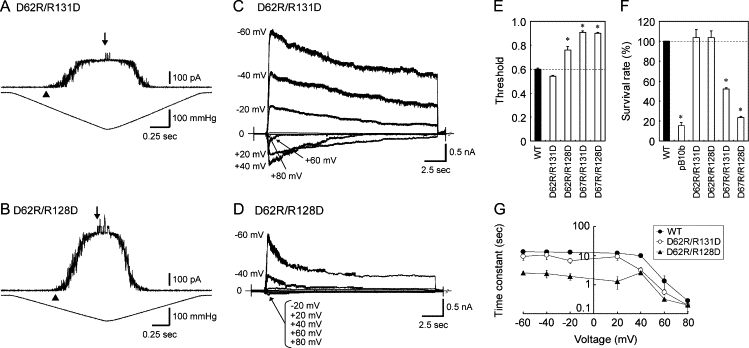

If the defects caused by the Asp-62, Arg-128, and Arg-131 mutations are caused by the loss of the electrostatic interactions between the positive and negative charges, the double mutations, D62R/R128D and D62R/R131D, in which the charges are interchanged, should complement such a deficiency. Indeed, the gating threshold, the survival rate, and the inactivation rate resumed wild-type values in D62R/R131D MscS (Fig. 6, A, C, E, F, and G). D62R/R128D exhibited a survival rate similar to that of wild-type MscS (Fig. 6 F), but the threshold and the inactivation rate were larger than for wild-type MscS (Fig. 6, B, D, E, and G). Mutant D67R MscS also had an increased threshold and inactivation rate. However, these effects were not negated by the addition of R128D or R131D substitutions (Fig. 6, E and F). Thus, complementation seems to occur completely between residues 62 and 131, partially between residues 62 and 128, and not at all between residues 67 and 131 or 128.

Figure 6.

Effects of combining the D62R mutation with a mutation at residue 131 or 128. (A and B) Channel activity of D62R/R131D (A) and D62R/R128D MscS (B) in response to negative pressure. MscS was expressed in ΔmscS cells. Cytoplasmic potential was −20 mV. (C and D) Macroscopic currents of D62R/R131D (C) and D62R/R128D MscS (D) obtained at cytoplasmic voltages ranging from −60 to +80 mV under constant pressure. The protocol is identical to that in Fig. 3 A. (E) The gating threshold, (F) the survival rates after hypoosmotic shock, and (G) the inactivation rates of wild-type, D62R/R131D, and D62R/R128D MscS. The gating threshold and the survival rate of D67R/R131D and D67R/R128D are also shown in E and F.

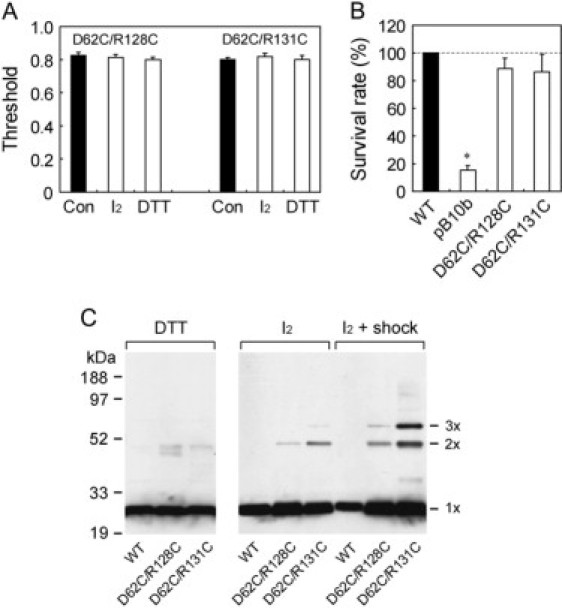

To ascertain whether the complementation between the mutations at residues 62 and 128/131 occurs through an electrostatic interaction, we tested whether double substitutions with a neutral amino acid would complement each other. D62C, R128C, and R131C have high thresholds and low survival rates, and neither D62C/R128C nor D62C/R131C resumed a wild-type threshold or survival rate (Fig. 7, A and B). There was no difference in the gating threshold measured under ambient, oxidizing, or reducing conditions. Thus, a simple combination of the defects at residues 62 and 128/131 is not sufficient for complementation.

Figure 7.

Examination of the formation of the disulfide bond in D62C/R128C and D62C/R131C MscS. (A) Gating threshold under ambient (Con), oxidizing (I2), and reducing conditions (DTT). (B) Survival rate on hypoosmotic shock. (C) MscS of the cells subjected to isosmotic or hypoosmotic dilution, under reducing (DTT) or oxidizing (I2) conditions. MscS was detected by Western blot using an anti-His antibody.

Although the patch-clamp experiment did not detect the formation of a disulfide bond between Cys-62 and Cys-128/131, it is possible that distance or steric hindrance prevented the efficient formation of a bond. Therefore, we used electrophoresis to analyze disulfide bond formation under oxidizing conditions. A faint band for the dimer was detected in the absence of hypoosmotic shock (Fig. 7 C). The amount of the dimer increased, and the band for the trimer appeared, when the cells were subjected to hypoosmotic shock. Under both conditions, D62C/R131C is cross-linked more effectively than D62C/R128C. Only the monomer was present in wild-type MscS or under reducing conditions.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the gating mechanism of MscS channels, concentrating on the interaction between the cytoplasmic vestibule and the loop that connects the TM1 and TM2 transmembrane helices. We examined the channel properties of various mutants using electrophysiological and cell biological experiments.

Neutralization of the negative charge of Asp-62 increased the gating threshold and the inactivation rate of the channel. Substitution with a positive charge resulted in an even larger increase. The replacement of Asp-62 by a negatively charged amino acid did not change either the threshold or the inactivation rate. Therefore, it seems that a negative charge at residue 62 is required for complete mechanosensitivity and a normal rate of inactivation.

The elevated threshold and the shortened duration of channel activity probably account for the decrease in survival rate of neutral and positively charged mutants after hypoosmotic shock (15). Even under conditions of overexpression, a relatively small increase in the gating threshold seems to directly influence cell survival. Several factors may give reasons for this. MscS gating requires high membrane tension (close to lytic tension) and may be particularly susceptible to the increased threshold. Also, the changes in channel kinetics are measured at room temperature (25°C) and −60 to +80 mV holding potential, whereas hypoosmotic shock is carried out at 37°C and less than −150 mV resting potential, which may lead to a greater effect on cell physiology.

The reversal or neutralization of the positive charge of Arg-128 and/or Arg-131 also increased the gating threshold and decreased the survival rate after hypoosmotic shock. The increase in inactivation rate was evident only in R131D MscS. Although both R131D and D62R MscS displayed fast inactivation rates, low survival rates, and high thresholds, the double mutant D62R/R131D MscS, in which the charge was exchanged, displayed characteristics similar to those of wild-type MscS. This finding is consistent with the hypothesis that an electrostatic interaction is present between residues 62 and 131 and is important for both normal inactivation rate and threshold. This hypothesis is further supported by the observation that cysteine mutations of residues 62 and 131 did not suppress these defects. Although dimers and trimers were formed in response to hypoosmotic shock, indicating that residues 62 and 131 approach each other during gating transitions, the failure to detect their influence in the patch clamp experiment suggests that the distance or steric relation between Cys-62 and Cys-131 is not optimal for disulfide bond formation. We suspect that the bulkier Arg-131 is able to be involved in an electrostatic interaction.

In contrast to the interaction between residues 62 and 131, the interaction between residues 62 and 128 appears to be more restricted. The introduction of the R128D mutation into D62R MscS yielded a wild-type survival rate but did not mitigate the high threshold or the fast inactivation rate. Both R128D and R128C MscS displayed a normal rate of inactivation, suggesting that an interaction between residues 62 and 128 is not necessary for inactivation. In addition, the dimer and trimer were produced less efficiently in D62C/R128C MscS than in D62C/R131C, supporting the idea that the interaction between residues 62 and 128 is less significant.

The crystal structure of MscS shows that Asp-62 is located closer to Arg-128 than to Arg-131. Therefore, the interaction between Asp-62 and Arg-131 is likely to be formed in a state that is unresolved by the crystal structure. What state the crystal structure represents is still not established; there are simulation studies that indicate that the crystal structure represents a closed or intermediate state (19,35), a closed conducting state (36), or a not fully open state (30). Because the loss of the interaction between residues 62 and 131 increased the gating threshold and the inactivation rate, it is likely that the interaction stabilizes the open state. Thus, we suspect that Asp-62 approaches Arg-131 during gating by the expansion of the transmembrane domain (17).

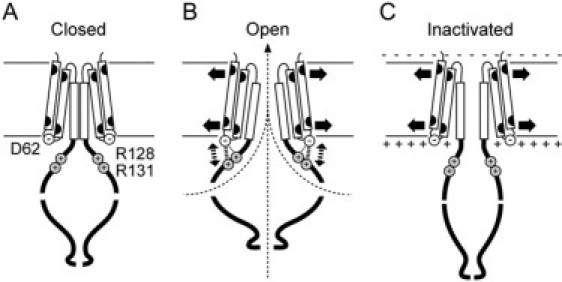

Based on our results, we constructed a model for the interaction between the transmembrane domain and the cytoplasmic vestibule (Fig. 8). During the transition from the closed state to the open state, Asp-62 interacts with Arg-128 as suggested in the simulation study (30). In the open state, Asp-62 interacts with Arg-131, and the electrostatic interaction stabilizes the open state (Fig. 8 B). This exchange of the partner of Asp-62 may be brought about by the expansion of the transmembrane domain and the cytoplasmic vestibule (17,37). The interaction between Asp-62 and Arg-131 is lost when MscS becomes inactivated and the cytoplasmic vestibule shrinks (37) (Fig. 8 C). The disruption of the interaction on channel inactivation is enhanced when the negative charge is canceled by the positive intracellular membrane potential (19).

Figure 8.

A model for the gating mechanism of MscS. Only two subunits, each consisting of TM1, TM2, TM3 (boxes), and cytoplasmic domain, are shown for simplicity. Asp-62 is located in the loop that connects TM1 and TM2. Arg-128 and Arg-131 are located in the upper surface of the cytoplasmic vestibule (A). When the channel opens, Asp-62 forms an electrostatic interaction with Arg-128 and Arg-131 (B). When the cytoplasmic potential is positive compared with the periplasmic potential, the electrostatic interaction is dissociated by the positive surface potential (C). The resulting shrinkage of the cytoplasmic vestibule brings about channel inactivation.

The data suggest that the interaction between the surface of the transmembrane domain and the cytoplasmic vestibule changes dynamically on gating. This idea is consistent with previous reports in which the transmembrane domain and the cytoplasmic vestibule showed significant conformational changes on gating (17,19,21,30,34,35,37,38). Further detailed studies on this interaction will reveal the function of the cytoplasmic vestibule, a distinctive and prominent structure of MscS.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan (to M.S. and K.Y.), a grant from the Japan Space Forum (to M.S.), and a grant from the Japan Science and Technology Agency (to K.Y.).

Footnotes

Editor: Eduardo Perozo.

References

- 1.Hamill O.P., Martinac B. Molecular basis of mechanotransduction in living cells. Physiol. Rev. 2001;81:685–740. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anishkin A., Kung C. Microbial mechanosensation. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2005;15:397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kung C. A possible unifying principle for mechanosensation. Nature. 2005;436:647–654. doi: 10.1038/nature03896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perozo E. Gating prokaryotic mechanosensitive channels. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:109–119. doi: 10.1038/nrm1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blount P., Schroeder M.J., Kung C. Mutations in a bacterial mechanosensitive channel change the cellular response to osmotic stress. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:32150–32157. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ajouz B., Berrier C., Garrigues A., Besnard M., Ghazi A. Release of thioredoxin via the mechanosensitive channel MscL during osmotic downshock of Escherichia coli cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:26670–26674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levina N., Tötemeyer S., Stokes N.R., Louis P., Jones M.A., Booth I.R. Protection of Escherichia coli cells against extreme turgor by activation of MscS and MscL mechanosensitive channels: identification of genes required for MscS activity. EMBO J. 1999;18:1730–1737. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.7.1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berrier C., Garrigues A., Richarme G., Ghazi A. Elongation factor Tu and DnaK are transferred from the cytoplasm to the periplasm of Escherichia coli during osmotic downshock presumably via the mechanosensitive channel MscL. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:248–251. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.1.248-251.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Batiza A.F., Kuo M.M.-C., Yoshimura K., Kung C. Gating the bacterial mechanosensitive channel MscL in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:5643–5648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082092599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okada K., Moe P.C., Blount P. Functional design of bacterial mechanosensitive channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:27682–27688. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202497200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martinac B., Buechner M., Delcour A.H., Adler J., Kung C. Pressure-sensitive ion channel in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1987;84:2297–2301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.8.2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sukharev S. Purification of the small mechanosensitive channel of Escherichia coli (MscS): the subunit structure, conduction, and gating characteristics in liposomes. Biophys. J. 2002;83:290–298. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75169-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sukharev S.I., Martinac B., Arshavsky V.Y., Kung C. Two types of mechanosensitive channels in the Escherichia coli cell envelope: solubilization and functional reconstitution. Biophys. J. 1993;65:177–183. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81044-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshimura K., Nomura T., Sokabe M. Loss-of-function mutations at the rim of the funnel of mechanosensitive channel MscL. Biophys. J. 2004;86:2113–2120. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74270-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nomura T., Sokabe M., Yoshimura K. Lipid-protein interaction of the MscS mechanosensitive channel examined by scanning mutagenesis. Biophys. J. 2006;91:2874–2881. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.084541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller S., Bartlett W., Chandrasekaran S., Simpson S., Edwards M., Booth I.R. Domain organization of the MscS mechanosensitive channel of Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 2003;22:36–46. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bass R.B., Strop P., Barclay M., Rees D.C. Crystal structure of Escherichia coli MscS, a voltage-modulated and mechanosensitive channel. Science. 2002;298:1582–1587. doi: 10.1126/science.1077945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sotomayor M., Van der Straaten T.A., Ravaioli U., Schulten K. Electrostatic properties of the mechanosensitive channel of small conductance MscS. Biophys. J. 2006;90:3496–3510. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.080069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akitake B., Anishkin A., Sukharev S. The “Dashpot” mechanism of stretch-dependent gating in MscS. J. Gen. Physiol. 2005;125:143–154. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller S., Edwards M.D., Ozdemir C., Booth I.R. The closed structure of the MscS mechanosensitive channel. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:32246–32250. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303188200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koprowski P., Kubalski A. C termini of the Escherichia coli mechanosensitive ion channel (MscS) move apart upon the channel opening. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:11237–11245. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212073200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakamura T., Gold G.H. A cyclic nucleotide-gated conductance in olfactory receptor cilia. Nature. 1987;325:442–444. doi: 10.1038/325442a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu M., Chen T.-Y., Ahamed B., Li J., Yau K.-W. Calcium-calmodulin modulation of the olfactory cyclic nucleotide-gated cation channel. Science. 1994;266:1348–1354. doi: 10.1126/science.266.5189.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Varnum M.D., Zagotta W.N. Interdomain interactions underlying activation of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Science. 1997;278:110–113. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sah P. Ca2+-activated K+ currents in neurons: types, physiological roles and modulation. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:150–154. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)80026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vergara C., Latorre R., Marrion N.V., Adelman J.P. Calcium-activated potassium channels. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1998;8:321–329. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(98)80056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greenwood I.A., Leblanc N. Overlapping pharmacology of Ca2+-activated Cl− and K+ channels. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2006;28:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hwang T.-C., Nagel G., Nairn A.C., Gadsby D.C. Regulation of the gating of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl channels by phosphorylation and ATP hydrolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:4698–4702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gadsby D.C., Nairn A. Control of CFTR channel gating by phosphorylation and nucleotide hydrolysis. Physiol. Rev. 1999;79:S77–S107. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.S77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sotomayor M., Schulten K. Molecular dynamics study of gating in the mechanosensitive channel of small conductance MscS. Biophys. J. 2004;87:3050–3065. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.046045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blount P., Sukharev S.I., Moe P.C., Martinac B., Kung C. Mechanosensitive channels of bacteria. Methods Enzymol. 1999;294:458–482. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)94027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoshimura K., Batiza A., Schroeder M., Blount P., Kung C. Hydrophilicity of a single residue within MscL correlates with increased channel mechanosensitivity. Biophys. J. 1999;77:1960–1972. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77037-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Besch S.R., Suchyna T., Sachs F. High-speed pressure clamp. Pflugers Arch. 2002;445:161–166. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0903-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sotomayor M., Vásquez V., Perozo E., Schulten K. Ion conduction through MscS as determined by electrophysiology and simulation. Biophys. J. 2007;92:886–902. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.095232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anishkin A., Sukharev S. Water dynamics and dewetting transitions in the small mechanosensitive channel MscS. Biophys. J. 2004;86:2883–2895. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74340-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spronk S.A., Elmore D.E., Dougherty D.A. Voltage-dependent hydration and conduction properties of the hydrophobic pore of the mechanosensitive channel of small conductance. Biophys. J. 2006;90:3555–3569. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.080432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grajkowski W., Kubalski A., Koprowski P. Surface changes of the mechanosensitive channel MscS upon its activation, inactivation, and closing. Biophys. J. 2005;88:3050–3059. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.053546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Edwards M.D., Li Y., Kim S., Miller S., Bartlett W., Black S., Dennison S., Iscla I., Blount P., Bowie J.U., Booth I.R. Pivotal role of the glycine-rich TM3 helix in gating the MscS mechanosensitive channel. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:113–119. doi: 10.1038/nsmb895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]