Abstract

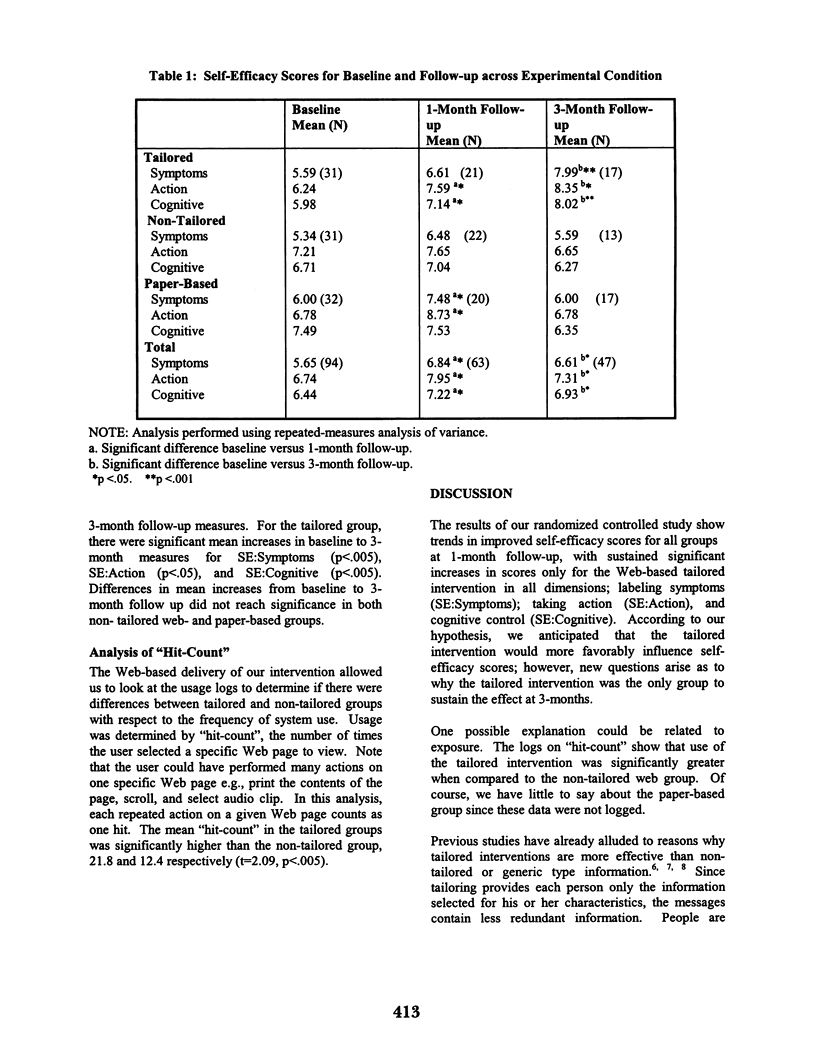

This paper reports the effects of a tailored Web-based delivery system on self-efficacy as it relates to a patients' response to acute myocardial information (AMI) symptoms. The data reported are from MI-HEART, a randomized trial examining ways in which a clinical information system can favorably influence the appropriateness and rapidity of decision-making in patients suffering from symptoms of acute myocardial infarction. Participants were randomized into one of three groups: tailored Web-based, non-tailored Web-based and non-tailored paper based. A theoretically based behavioral-cognitive model was used to identify key variables upon which to tailor education material. A key variable in the model is self-efficacy, operationalized with a three-dimensional scaling. Results show trends in improved self-efficacy scores for all groups at 1-month follow up, with sustained significant increases in baseline to 3-month scores only in the tailored Web-based group. One possible explanation could be related to "hit-count", which was significantly higher in the tailored group. This study is a first step in quantifying the contribution of Web-based tailoring over non-tailoring in changing key determinants of patient delay to AMI symptoms.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bandura A., Reese L., Adams N. E. Microanalysis of action and fear arousal as a function of differential levels of perceived self-efficacy. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1982 Jul;43(1):5–21. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.43.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull F. C., Kreuter M. W., Scharff D. P. Effects of tailored, personalized and general health messages on physical activity. Patient Educ Couns. 1999 Feb;36(2):181–192. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M. K., DeVellis B. M., Strecher V. J., Ammerman A. S., DeVellis R. F., Sandler R. S. Improving dietary behavior: the effectiveness of tailored messages in primary care settings. Am J Public Health. 1994 May;84(5):783–787. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.5.783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dracup K., Moser D. K., Eisenberg M., Meischke H., Alonzo A. A., Braslow A. Causes of delay in seeking treatment for heart attack symptoms. Soc Sci Med. 1995 Feb;40(3):379–392. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00278-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukafka R., Lussier Y. A., Patel V. L., Cimino J. J. Modeling patient response to acute myocardial infarction: implications for a tailored technology-based program to reduce patient delay. Proc AMIA Symp. 1999:570–574. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozer E. M., Bandura A. Mechanisms governing empowerment effects: a self-efficacy analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990 Mar;58(3):472–486. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner C. S., Campbell M. K., Rimer B. K., Curry S., Prochaska J. O. How effective is tailored print communication? Ann Behav Med. 1999 Fall;21(4):290–298. doi: 10.1007/BF02895960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]