Abstract

The psychological and neurobiological processes underlying moral judgement have been the focus of many recent empirical studies1–11. Of central interest is whether emotions play a causal role in moral judgement, and, in parallel, how emotion-related areas of the brain contribute to moral judgement. Here we show that six patients with focal bilateral damage to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPC), a brain region necessary for the normal generation of emotions and, in particular, social emotions12–14, produce an abnormally ‘utilitarian’ pattern of judgements on moral dilemmas that pit compelling considerations of aggregate welfare against highly emotionally aversive behaviours (for example, having to sacrifice one person’s life to save a number of other lives)7,8. In contrast, the VMPC patients’ judgements were normal in other classes of moral dilemmas. These findings indicate that, for a selective set of moral dilemmas, the VMPC is critical for normal judgements of right and wrong. The findings support a necessary role for emotion in the generation of those judgements.

The basis of our moral judgements has been a long-standing focus of philosophical inquiry and, more recently, active empirical investigation. In a departure from traditional rationalist approaches to moral cognition that emphasize the role of conscious reasoning from explicit principles15, modern accounts have proposed that emotional processes, conscious or unconscious, may also play an important role16,17. Emotion-based accounts draw support from multiple lines of empirical work: studies of clinical populations reveal an association between impaired emotional processing and disturbances in moral behaviour1–4; neuroimaging studies consistently show that tasks involving moral judgement activate brain areas known to process emotions5–9; and behavioural studies demonstrate that manipulation of affective state can alter moral judgements10,11. However, neuroimaging studies do not settle whether putatively ‘emotional’ activations are a cause or consequence of moral judgement; behavioural studies in healthy individuals do not address the neural basis of moral judgement; and no clinical studies have specifically examined the moral judgements (as opposed to moral reasoning or moral behaviour) of patients with focal brain lesions. In brief, none of the existing studies establishes that brain areas integral to emotional processes are necessary for the generation of normal moral judgements. As a result, there remains a critical gap in the evidence relating moral judgement, emotion and the brain.

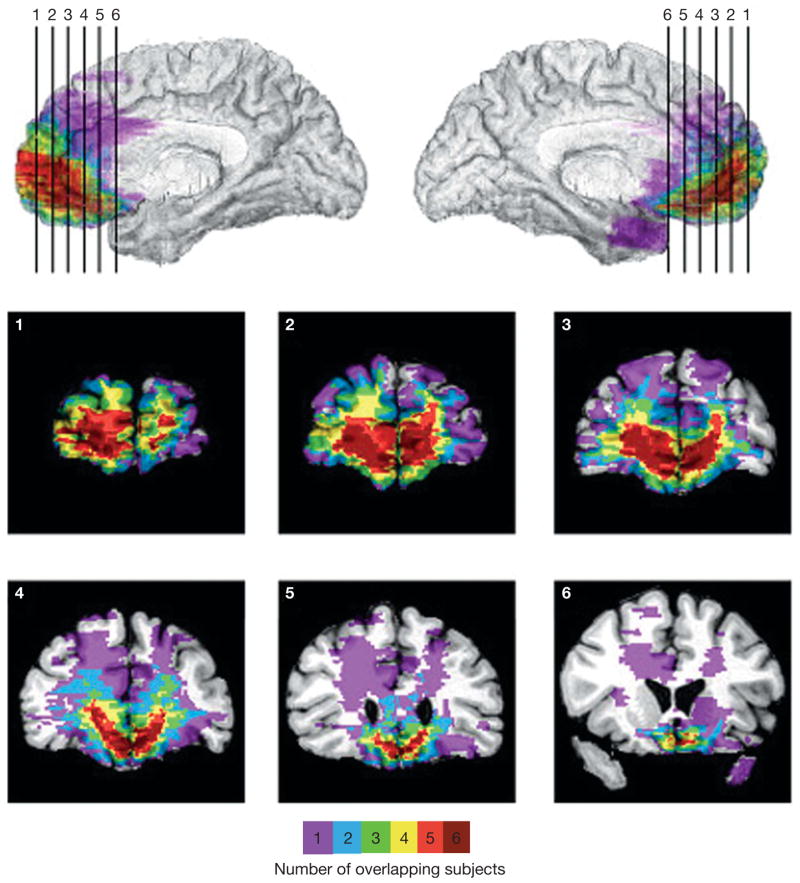

Investigating moral judgements in individuals with focal damage to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPC) provides a key test. The VMPC projects to basal forebrain and brainstem regions that execute bodily components of emotional responses18, and neurons within the VMPC encode the emotional value of sensory stimuli19. Patients with VMPC lesions exhibit generally diminished emotional responsivity and markedly reduced social emotions (for example, compassion, shame and guilt) that are closely associated with moral values1,2,12–14,16, and also exhibit poorly regulated anger and frustration tolerance in certain circumstances20,21. Despite these patent defects both in emotional response and emotion regulation, the capacities for general intelligence, logical reasoning, and declarative knowledge of social and moral norms are preserved20–23. We selected a sample of six patients with adult-onset, focal bilateral VMPC lesions (Fig. 1) as well as both neurologically normal (NC) and brain-damaged comparison (BDC) subjects. Importantly, each of the VMPC patients had striking defects in social emotion but generally intact intellect and normal baseline mood (Tables 1 and 2, see also Supplementary Table 1). In particular, all six VMPC patients had impaired autonomic activity in response to emotionally charged pictures (Table 2), as well as severely diminished empathy, embarrassment and guilt (Table 2). All comparison subjects (NC and BDC) had intact emotional processing.

Figure 1. Lesion overlap of VMPC patients.

Lesions of the six VMPC patients displayed in mesial views and coronal slices. The colour bar indicates the number of overlapping lesions at each voxel.

Table 1.

VMPC patient neuropsychological data

| WAIS-III | WMS-III | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | VIQ | PIQ | FSIQ | GMI | WMI | TT | WCST | Stroop | BDI |

| 1 | 142 | 134 | 143 | 109 | 124 | 44 | 6 | 70 | 0 |

| 2 | 89 | 97 | 91 | 59 | 102 | 44 | 6 | 49 | 3 |

| 3 | 111 | 96 | 104 | 74 | 105 | 44 | 6 | 67 | 10 |

| 4 | 108 | 102 | 106 | 109 | 124 | 44 | 6 | 57 | 1 |

| 5 | 110 | 107 | 109 | 105 | 102 | 44 | 6 | 54 | 8 |

| 6 | 89 | 80 | 84 | 96 | 88 | 44 | 0 | 77 | 7 |

WAIS-III, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III scores (VIQ, verbal IQ; PIQ, performance IQ; FSIQ, full-scale IQ). WMS-III, Wechsler Memory Scale-III scores (GMI, general memory index; WMI, working memory index). TT, Token Test (from the Multilingual Aphasia Examination), a measure of basic verbal comprehension. WCST, Wisconsin Card Sort Test categories, a measure of executive function. Stroop, T-score on the Interference trial of the Stroop Colour-Word Test, a measure of response inhibition. BDI, Beck Depression Inventory, a measure of baseline mood. All patients were within normal ranges except for subjects 2 and 3 on GMI and subject 6 on WCST and Stroop.

Table 2.

VMPC patient social emotion data

| Subject | SCRs | Empathy | Embarrassment | Guilt |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Impaired | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 2 | Impaired | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 3 | Impaired | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 4 | Impaired | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 5 | Impaired | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 6 | Impaired | 3 | 3 | 3 |

SCRs, skin conductance responses to emotionally charged socially significant stimuli (for example, pictures of social disasters, mutilations, nudes), using methods previously described12. The same SCR experiment was performed in ten of twelve BDC patients, and all ten demonstrated normal SCRs to emotionally charged pictures. A clinical neuropsychologist blind to the hypotheses of the current study rated each VMPC patient’s demonstrated capacity for empathy, embarrassment and guilt in his or her personal life. The rating used a four-point scale denoting severity of impairment, where 0 = normal, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate and 3 = severe. Ratings were based on data derived from spouse or family member reports in the Iowa Rating Scales of Personality Change29 and from data from clinical interviews. Both of these sources provide direct observations about the patient’s basic and social emotions, and include questions about whether the patient experiences and manifests emotions such as sadness, anxiety, empathy, embarrassment and guilt.

Subjects evaluated moral dilemmas designed to pit two competing considerations against one another. A paradigmatic dilemma of this type presents subjects with the choice of whether or not to sacrifice one person’s life to save the lives of others. One consideration is a utilitarian calculation of how to maximize aggregate welfare, whereas the other is a strong emotional aversion to the proposed action. One model holds that endorsement of the proposed action (the utilitarian response) requires the subject to overcome an emotional response against inflicting direct harm to another person (a ‘personal’ harm7,8). If emotional responses mediated by VMPC are indeed a critical influence on moral judgement, individuals with VMPC lesions should exhibit an abnormally high rate of utilitarian judgements on the emotionally salient, or ‘personal’, moral scenarios (for example, pushing one person off a bridge to stop a runaway boxcar from hitting five people), but a normal pattern of judgements on the less emotional, or ‘impersonal’, moral scenarios (for example, turning a runaway boxcar away from five people but towards one person). If, alternatively, emotion does not play a causal role in the generation of moral judgements but instead follows from the judgements24,25, then individuals with emotion defects due to VMPC lesions should show a normal pattern of judgements on all scenarios.

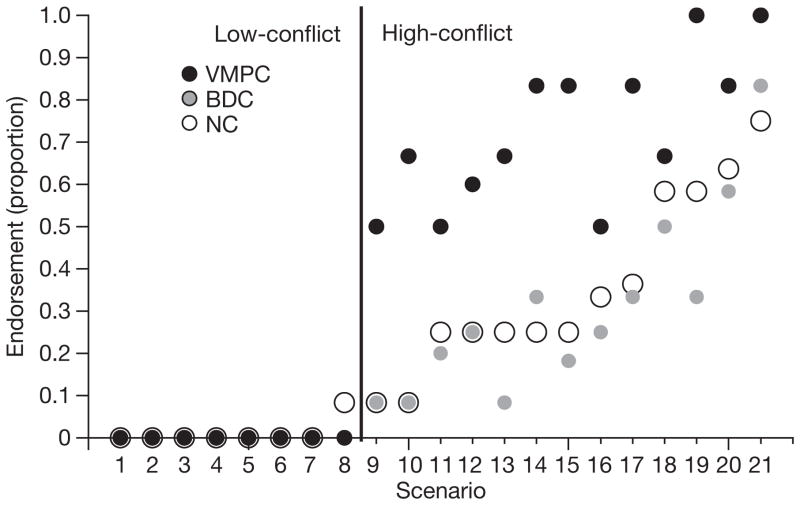

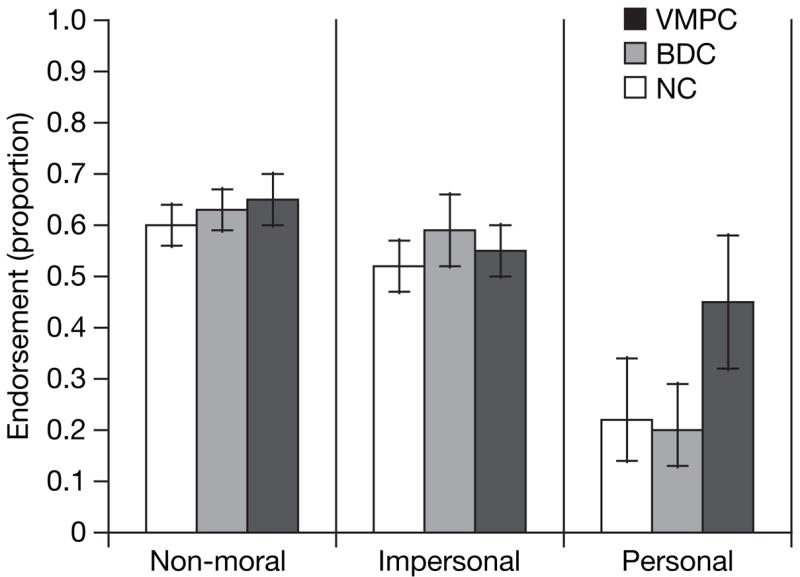

To test for between-group differences in the probability of utilitarian responses given for each scenario type (non-moral, impersonal moral, personal moral), we used a logistic regression fitted with the generalized estimating equations method (Fig. 2). There were no significant differences between groups on the non-moral or impersonal moral scenarios (all P values >0.29, corrected for multiple comparisons). In contrast, for personal moral scenarios, the VMPC group was more likely to endorse the proposed action than either the NC group (odds ratio = 2.81; P = 0.04, corrected) or BDC group (odds ratio = 3.30; P = 0.006, corrected). There was no difference between the NC and BDC groups (odds ratio = 0.85; P = 0.68, uncorrected). These data indicate that the VMPC group’s responses differed only for personal moral scenarios, suggesting that VMPC-mediated processes affect only those moral judgements involving emotionally salient actions.

Figure 2. Moral judgements for each scenario type.

Proportions of ‘yes’ judgements are shown for each subject group. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. We used three classes of stimuli: non-moral scenarios (n = 18), impersonal moral scenarios (n = 11), and personal moral scenarios (n = 21). On personal moral scenarios, the frequency of endorsing ‘yes’ responses was significantly greater in the VMPC group than in either comparison group (P values < 0.05, corrected).

In a more fine-grained analysis, we examined response patterns within the personal moral scenarios. For seven out of the 21 personal moral scenarios, both comparison groups were at 100% agreement in their judgements. An additional eighth scenario elicited 100% agreement from the BDC group, and near-perfect agreement from the NC group (with only one participant deviating from the shared response). These eight scenarios were therefore classified as ‘low-conflict’ (for example, abandoning one’s baby to avoid the burden of caring for it). The remaining 13 scenarios (none of which elicited 100% agreement from either comparison group) were classified as ‘high-conflict’ (for example, smothering one’s baby to save a number of people). Reaction-time data support this distinction: response latencies in the NC group on high-conflict scenarios were significantly longer than on low-conflict scenarios (t-test with 19 degrees of freedom, t(19) = −3.63; P = 0.002).

Like the patients in the comparison groups, the VMPC patients uniformly rejected the proposed action in every one of the low-conflict scenarios (Fig. 3). In contrast, significant differences emerged for the high-conflict scenarios: the VMPC group was more likely to endorse the proposed action than either the NC (odds ratio = 4.70; P = 0.05, corrected) or BDC group (odds ratio = 5.38; P = 0.02, corrected), with no difference between the NC and BDC participants (odds ratio = 0.87; P = 0.77, uncorrected). Every high-conflict personal scenario elicited the same pattern: a greater proportion of the VMPC group endorsed the action than either comparison group.

Figure 3. Moral judgements on individual personal moral scenarios.

Proportions of ‘yes’ judgements given by each subject group for each of the 21 personal moral scenarios. Individual scenarios (numbered 1–21 on the x axis) are ordered by increasing proportion of ‘yes’ responses given by the normal comparison group. Responses did not differ between subject groups for the low-conflict scenarios (left of the vertical line). The VMPC group made a greater proportion of ‘yes’ judgements than either comparison group for every one of the high-conflict scenarios (right of the vertical line).

To recapitulate, VMPC patients’ judgements differed from comparison subjects’ only for the high-conflict personal moral dilemmas, all of which featured competing considerations of aggregate welfare on the one hand, and, on the other hand, harm to others that would normally evoke a strong social emotion. Low-conflict personal moral scenarios lacked this degree of competition. This difference probably accounts for the greater consensus and faster reaction times on low-conflict personal dilemmas in the comparison groups, and it can also account for the VMPC patients’ pattern of judgements. Evidence suggests that knowledge of explicit social and moral norms is intact in individuals with VMPC damage21,22. In the absence of an emotional reaction to harm of others in personal moral dilemmas, VMPC patients may rely on explicit norms endorsing the maximization of aggregate welfare and prohibiting the harming of others. This strategy would lead VMPC patients to a normal pattern of judgements on low-conflict personal dilemmas but an abnormal pattern of judgements on high-conflict personal dilemmas, precisely as was observed. The specificity of this result argues against a general deficit in the capacity for moral judgement following VMPC damage. Rather, VMPC seems to be critical only for moral dilemmas in which social emotions play a pivotal role in resolving moral conflict4,8,16,17.

It is important to note that the effects of VMPC damage on emotion processing depend on context. In this study, the VMPC patients’ abnormally high rate of utilitarian judgements is attributed to diminished social emotion, whereas in a recent study of the Ultimatum Game, theVMPC patients’ abnormally high rate of rejection of unfair monetary offers was attributed to poorly controlled frustration, manifested as exaggerated anger20. These seemingly contradictory findings highlight two distinct aspects of emotion impairment that are due to VMPC damage. In most circumstances, VMPC patients exhibit generally blunted affect and a specific defect of social emotions, but in response to direct personal frustration or provocation, VMPC patients may exhibit short-temper, irritability, and anger. In the moral judgement task we report here, participants respond to hypothetical actions and outcomes that elicit social emotions related to concern for others. In the Ultimatum Game, in contrast, participants respond to unfair take-it-or-leave-it offers that trigger frustration. In brief, the tasks in the two studies are different in that the Ultimatum Game involves self-interest in a real behavioural setting, whereas the task in the present study focuses on the interest of others described in a hypothetical scenario.

To conclude, the present findings are consistent with a model in which a combination of intuitive/affective and conscious/rational mechanisms operate to produce moral judgements8,22,24–27. Though the precise characterization of these potential systems awaits further work, the current results suggest that the VMPC is a critical neural substrate for the intuitive/affective but not for the conscious/rational system.

METHODS

Subjects

Six patients with bilateral, adult-onset damage to the VMPC and twelve brain-damaged comparison patients who had lesions that excluded structures thought to be important for emotions (VMPC, amygdala, insula, right somatosensory cortices) were recruited from the Patient Registry of the Division of Cognitive Neuroscience at the University of Iowa. Twelve healthy comparison subjects with no brain damage were recruited from the Iowa community. Groups were age-, gender- and ethnicity-matched. All participants gave written informed consent.

Neuroanatomical analysis

The neuroanatomical analysis of VMPC patients (Fig. 1) was based on magnetic resonance data for two subjects (those with lesions due to the surgical resection of orbital meningiomas) and on computerized tomography data for the other four subjects (with lesions due to rupture of an anterior communicating artery aneurysm). All neuroimaging data were obtained in the chronic epoch. Each patient’s lesion was reconstructed in three dimensions using Brainvox28. Using the MAP-3 technique, the lesion contour for each patient was manually warped into a normal template brain. The overlap of lesions in this volume, calculated by the sum of n lesions overlapping on any single voxel, is colour-coded in Fig. 1.

Stimuli and task

Participants made judgements on a series of 50 hypothetical scenarios, which were adapted from a previously published set8. See the Supplementary Information for the full text of the actual scenarios used. Each scenario was presented as text through a series of three screens. The first two described the scenario and the third posed a question about a hypothetical action related to the scenario (“Would you … in order to …?”). Participants read and responded at their own pace, pressing an ‘up’ arrow key to advance from one screen to the next, and a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ button to indicate an answer to the question. ‘Yes’ responses always indicated commission of the proposed action. There was no time limit for reading the scenario description (screens 1 and 2). Participants had a maximum of 25 s to read the final question screen and respond.

We used three classes of stimuli: non-moral scenarios (n = 18), and two classes of moral scenarios subdivided according to the emotional reaction elicited by the proposed action: ‘personal’ (n = 21) or ‘impersonal’ (n = 11), as described previously7,8. To validate this subdivision, an independent group of ten neurologically normal subjects rated the emotional salience of the actions proposed in the moral scenarios. The actions described in personal scenarios were rated as significantly more emotionally salient than the actions described in impersonal scenarios (means were 5.9 and 3.0 on a scale from 1 to 7, respectively; t(31) = −8.90, P<0.0001). Within either class of moral scenarios (personal or impersonal), it was not valid to separately analyse judgements based on the emotional salience of the proposed action (that is ‘high-emotion’ versus ‘low-emotion’ scenarios) because emotionality ratings were remarkably similar for scenarios within each class: 9 of the 11 impersonal scenarios received a mean emotion rating between 1.1 and 3.0, while 20 of the 21 personal scenarios received a mean emotion rating between 5.3 and 6.7.

We further subdivided the personal moral scenarios into ‘low-conflict’ and ‘high-conflict’ on the basis of the reaction times and consensus produced on them by normal subjects. Reaction times on high-conflict scenarios were significantly longer than on low-conflict scenarios (t(19) = −3.63, P = 0.002). Importantly, low-conflict and high-conflict scenarios did not differ in their rated emotional salience (t(19) = −0.85, P = 0.41).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Damasio for making available neuroanatomical analyses of lesion patients and for preparing Fig. 1. We thank all participants for their participation in the experiments and R. Saxe for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and the Guggenheim Foundation.

References

- 1.Eslinger PJ, Grattan LM, Damasio AR. Developmental consequences of childhood frontal lobe damage. Arch Neurol. 1992;49:764–769. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1992.00530310112021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson SW, Bechara A, Damasio H, Tranel D, Damasio AR. Impairment of social and moral behavior related to early damage in human prefrontal cortex. Nature Neurosci. 1999;2:1032–1037. doi: 10.1038/14833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blair RJR. A cognitive developmental approach to morality: investigating the psychopath. Cognition. 1995;57:1–29. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(95)00676-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mendez MF, Anderson E, Shapira JS. An investigation of moral judgment in frontotemporal dementia. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2005;18:193–197. doi: 10.1097/01.wnn.0000191292.17964.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Oliveira-Souza R, Bramati I, de Oliveira-Souza R, Bramati IE, Grafman J. Functional networks in emotional moral and nonmoral social judgments. Neuroimage. 2002;16:696–703. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heekeren HR, Wartenburger I, Schmidt H, Schwintowski HP, Villringer A. An fMRI study of simple ethical decision-making. Neuroreport. 2003;14:1215–1219. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200307010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greene JD, Sommerville RB, Nystrom LE, Darley JM, Cohen JD. An fMRI investigation of emotional engagement in moral judgment. Science. 2001;293:2105–2108. doi: 10.1126/science.1062872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greene JD, Nystrom LE, Engell AD, Darley JM, Cohen JD. The neural bases of cognitive conflict and control in moral judgment. Neuron. 2004;44:389–400. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luo Q, et al. The neural basis of implicit moral attitude–An IAT study using event-related fMRI. Neuroimage. 2006;30:1449–1457. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wheatley T, Haidt J. Hypnotic disgust makes moral judgments more severe. Psychol Sci. 2005;16:780–784. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valdesolo P, DeSteno D. Manipulations of emotional context shape moral judgment. Psychol Sci. 2006;17:476–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Damasio AR, Tranel D, Damasio H. Individuals with sociopathic behavior caused by frontal damage fail to respond autonomically to social stimuli. Behav Brain Res. 1990;41:81–94. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(90)90144-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Damasio AR. Looking for Spinoza: Joy, Sorrow, and the Feeling Brain. Harcourt; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beer JS, Heerey EH, Keltner D, Scabini D, Knight RT. The regulatory function of self-conscious emotion: Insights from patients with orbitofrontal damage. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85:594–604. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.4.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kohlberg L. The Philosophy of Moral Development. Vol. 1. Harper Row; New York: 1981. Essays on Moral Development. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Damasio AR. Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. Penguin; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haidt J. The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychol Rev. 2001;108:814–834. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.4.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ongur D, Price JL. The organization of networks within the orbital and medial prefrontal cortex of rats, monkeys and humans. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:206–219. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.3.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rolls E. The orbitofrontal cortex and reward. Cereb Cortex. 2000;3:284–294. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.3.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koenigs M, Tranel D. Irrational economic decision-making after ventromedial prefrontal damage: evidence from the ultimatum game. J Neurosci. 2007;27:951–956. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4606-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson SW, Barrash J, Bechara A, Tranel D. Impairments of emotion and real-world complex behavior following childhood- or adult-onset damage to ventromedial prefrontal cortex. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2006;12:224–235. doi: 10.1017/S1355617706060346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saver JL, Damasio AR. Preserved access and processing of social knowledge in a patient with acquired sociopathy due to ventromedial frontal damage. Neuropsychologia. 1991;29:1241–1249. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(91)90037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burgess PW, et al. The case for the development and use of ‘‘ecologically valid’’ measures of executive functions in experimental and clinical neuropsychology. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2006;12:194–209. doi: 10.1017/S1355617706060310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hauser MD. Moral Minds: How Nature Designed our Universal Sense of Right and Wrong. Ecco/Harper Collins; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mikhail J. PhD thesis. Cornell Univ; 2000. Rawls’ Linguistic Analogy. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cushman FA, Young LL, Hauser MD. The role of conscious reasoning and intuition in moral judgments: Testing three principles of permissible harm. Psychol Sci. 2006;17:1082–1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hauser MD, Cushman FA, Young LL, Jin KX, Mikhail J. A dissociation between moral judgments and justifications. Mind Language. 2006;22:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frank RJ, Damasio H, Grabowski TJ. Brainvox: an interactive, multimodal visualization and analysis system for neuroanatomical imaging. Neuroimage. 1997;5:13–30. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1996.0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barrash J, Anderson SW. The Iowa Rating Scales of Personality Change. Department of Neurology, Univ; Iowa, Iowa: 1993. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.