Abstract

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a progressive degenerative disease affecting upper and lower motor neurons. Symptom onset may occur in the muscles of the limbs (spinal onset) or those of the head and neck (bulbar onset). Bulbar involvement is particularly important in ALS as it is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. The purpose of this study was to characterize bulbar motor deficits in the SOD1-G93A mouse model of familial ALS. We measured orolingual motor function by placing thirsty mice in a customized operant chamber that allows for measurement of tongue force and lick rhythm as animals lick water from an isometric disc. Testing spanned the pre-symptomatic, symptomatic, and end-stage segments of the disease. Rotarod performance, fore- and hindlimb grip strength, and locomotor activity were also monitored regularly during this period. We found that spinal involvement was apparent first, with both fore- and hindlimb grip strength being affected in SOD1-G93A mice from the onset of testing (64 days of age). Rotarod performance was affected by 71 days of age. Locomotor activity was not affected, even near end-stage. Bulbar involvement appeared much later, with tongue motility being affected by 100 days of age. Tongue force was affected by 115 days of age. To our knowledge, these findings are the first to describe the onset of bulbar v. spinal motor signs and characterize orolingual motor deficits in this preclinical model of ALS.

Keywords: familial ALS, G1H, bulbar, tongue, operant behavioral task, grip strength

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a progressive degenerative motor neuron disease with an invariably fatal outcome. Both lower and upper motor neurons are affected, resulting in a variety of manifestations including marked muscle weakness and atrophy, fasciculations, and reflex abnormalities (Rowland and Shneider, 2001). Symptom onset may occur in the muscles of the limbs (spinal onset) or in those of the head and neck (bulbar onset). While death results from the weakening of respiratory muscles, a spinal manifestation, bulbar involvement is particularly important in ALS as it is associated with increased morbidity and mortality (Rosen, 1978). The progressive weakening and atrophy of the masticatory muscles and tongue underlie the deficits in speech, chewing, and swallowing that give rise to social isolation and difficulties with feeding and aspiration (DePaul et al., 1988).

Up to 35% of new ALS patients seek medical attention for dysarthria, suggesting that tongue motility is the prevalent orolingual motor deficit in ALS and an early sign of the disease (Mitsumoto et al., 1998). However, clinical studies evaluating tongue force and motility have found that tongue weakness precedes dysarthria in bulbar onset ALS (DePaul et al., 1988; Langmore and Lehman, 1994). Tongue weakness is also present in spinal onset patients not exhibiting dysarthria. The maximal temporal rate of normal speech places great demands on tongue motility but does not require maximal tongue force, allowing tongue weakness to go undetected in many cases (Langmore and Lehman, 1994).

Approximately 90% of ALS cases are sporadic in nature; in the remaining cases, the disease is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner (familial ALS, fALS) (Deng et al., 1993; Rosen, 1993). Although the etiology of sporadic ALS is unknown, mutations in the Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase-1 (SOD1) gene are associated with approximately 20% of fALS cases (Deng et al., 1993; Rosen, 1993). Several transgenic rodent models of fALS have been developed, with the SOD1-G93A mouse model being the most widely studied. In this model the SOD1 gene contains a glycine to alanine substitution at position 93, resulting in a toxic gain of SOD1 function (Gurney et al., 1994; Yim et al., 1996). For reasons still unknown, these animals develop an ALS-like phenotype and pathology, including adult-onset muscle weakness and atrophy and motor neuron degeneration. Spinal involvement has been the focus of most preclinical studies to date and the onset and time-course of spinal manifestations have been characterized behaviorally and anatomically (Dal Canto and Gurney, 1994; Gurney et al., 1994; Kong and Xu, 1998; Weydt et al., 2003). Although bulbar involvement has been documented anatomically (Hottinger et al., 1997; Nimchinsky et al., 2000; Millecamps et al., 2001; Haenggeli and Kato, 2002), to our knowledge, bulbar motor signs have not been documented in animal models of ALS.

In the clinic, bulbar motor signs are assessed by measuring tongue motility and strength. In rodents, ingestive fluid licking is a highly stereotyped behavior involving repetitive movements of the tongue and jaw (Travers et al., 1997). Through evaluation of such behavior, the onset and severity of orolingual motor deficits arising from brainstem motor neuron degeneration can be modeled preclinically. The purpose of this study was to determine the relative onset of bulbar v. spinal signs in SOD1-G93A mice, as well as to characterize bulbar motor deficits. Specifically, we aimed to evaluate relevant aspects of orolingual motor function—tongue motility and force. To our knowledge, these findings are the first to characterize bulbar motor deficits in a preclinical model of ALS.

Experimental procedures

Twenty-four female B6SJL-Tg(SOD1-G93A)1Gur/J (SOD1-G93A; n=12) and B6SJL-Tg(SOD1)2Gur/J (control; n=12) mice (Jackson Laboratory) served as subjects in this experiment. These SOD1-G93A mice carry a high copy number of the mutated allele of the human SOD1 gene and control mice carry a high copy number of the normal allele of the human SOD1 gene. In contrast to low-expressing SOD1-G93A mice (often referred to as G1L), which exhibit delayed disease onset and mortality, the high-expressing SOD1-G93A mice (often referred to as G1H) used here typically survive only approximately 130–160 days. Mice were housed individually in an AAALAC-approved animal care facility with free access to food. Mice were placed on a gradual water restriction schedule that ultimately allowed access to water for approximately 30–45 minutes/day. Mice were maintained on a 12/12 hour light/dark cycle and all behavioral testing was performed during the light portion of this cycle. Body weight was monitored daily. The estrus cycles of these mice were not monitored. All procedures were approved by the University of Kansas Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were carried out in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Behavioral assessment and analysis

Orolingual motor function

Tongue motility and force were evaluated daily (58 measurements taken) using an operant procedure described in depth by Fowler and Wang (1998). Briefly, animals were placed individually into a customized Gerbrands rodent operant chamber with a front panel containing a 6 cm2 hole at floor level. Affixed to the square hole is a 6 cm3 transparent enclosure that, on its lower horizontal surface, contains a 12 mm-diameter hole through which the mouse can extend its tongue downward to reach the operandum. The operandum is an 18 mm-diameter aluminum disc rigidly attached to the shaft of a Model 31 load cell (0–250 g range, Sensotec, Columbus, OH). The disc is centered 2 mm beneath the hole in the plastic enclosure. A computer-controlled peristaltic pump, (Series E at 14 rpm; Manostat Corp., New York, NY), fitted with a solid-state relay (Digikey, Thief River Falls, MN) and controlled by a LabMaster computer interface (LabMaster, Solon, OH), delivers water to the center of the lick disc through a 0.5 mm-diameter hole. This apparatus, with the current dimensions, has been used to study both rats and mice (Fowler and Wang, 1998; Wang and Fowler, 1999).

The force transducer is capable of resolving force measurements to 0.2 g equivalent weights. A PC records the transducer’s force-time output at a rate of 100 samples/second. This force sensitivity and sampling rate make it possible to resolve the force-time waveforms of each individual lick. The force requirement was 1 g to register a response, as well as to advance the count towards water delivery. Twelve licks of the appropriate force were required to produce 0.015 ml of water (i.e., a fixed-ratio-12 schedule). Animals were placed in the apparatus for 6 minute sessions for which the entire force-time record was stored and then subjected to the Fourier-based rhythm analysis described below.

Computation of the power spectra was performed by MatLab’s Signal Processing Toolbox (The Math Works, Inc, Natick, MA). For this analysis, each 6 minute session was divided into 35 series of 1024 samples from the lick-force transducer. With the Hanning data window selected, MatLab produced 35 corresponding power spectra. The power spectra were truncated to 25 Hz (based on prior work indicating little of behavioral interest beyond 25 Hz) and averaged together to yield a single power spectrum. A peak-finding program written in Free Pascal was used to identify the peak in the averaged power spectrum, and the frequency at this peak was taken as the lick rhythm for a particular session. This method resolves lick rhythm to the nearest 0.1 Hz.

Grip force

Fore- and hindlimb grip force was evaluated 3 times/week (24 measurements taken) using an animal grip strength system (San Diego Instruments). Mice were passed over a metal mesh grid connected to a force transducer. Mice gripped the grid with either their fore- or hindlimbs and then were tugged gently away until the grip was released. The peak force in grams was recorded by the transducer. Three fore- and 3 hindlimb trials were performed during each test session. The highest of the 3 values for each was recorded for analysis.

Rotarod

Performance on a rotating rod was evaluated 3 times/week (24 measurements taken). Mice were placed on a rotarod (MedAssociates) rotating at 2.0 rpm. The rotations gradually increased in speed from 2.0 to 20 rpm over the course of 5 minutes. Each test session lasted 7 minutes. Mice able to stay on the rod for the entire test session received a score of 1. Mice that fell off at any time during the test session received a score of 0. Mice unable to keep up with the rotations but able to cling to it also received a score of 0. Results are presented as the percentage of each group that successfully completed a test session.

Actometer

Locomotor activity was evaluated weekly (9 measurements taken), on days free of grip strength and rotorod testing, using a force-plate actometer, described in depth in Fowler et al. (2001). Briefly, the actometer consists of a lightweight rectangular plate resting on four isometric force transducers, one placed underneath each corner of the plate. Plexi-glass housing fits over the surface to contain the test subject. The transducers are connected to a PC that samples the subject’s center of force (based on Cartesian coordinates) every 0.02 seconds with a spatial resolution of less than 1 mm. Distance traveled (in mm) is calculated as the line integral of movement of the subject’s center of force. Animals were placed on the force-plate for 30 minute test sessions and the distances traveled over that time period were recorded for analysis.

Statistical analysis

Control mice arrived from the vendor approximately 1 month after we received and began testing in the SOD1-G93A mice. Consequently, graphs depict some time points at which data were available only for SOD1-G93A mice. Statistical analyses, however, were performed only on time points at which data were collected for both groups (tongue motility and force=40 time points, grip strength and rotarod=16 time points, locomotor activity=6 time points). Furthermore, the control group was comprised of different ages of mice. At the onset of testing, control mice ranged in age from 49–81 days with a mean of 66 days. All control mice were young adults at the onset of testing, therefore, we do not consider this to be a significant issue. Graphs indicate the days of age of the SOD1-G93A mice at each respective time point.

With the exception of rotarod data, statistical analyses for all behavioral data consisted of 2-way repeated measures analyses of variance with group (SOD1-G93A and control) as the between factors variable and time (age) as the within factors variable. Differences between groups were identified via post-hoc comparisons. When a significant difference was observed for 3 consecutive test days, the third day was taken as the age at which a consistent significant difference is first observed. In cases where a mouse had to be killed before the end of the study (n=3 SOD1-G93A mice), the values of the last measurements taken were filled in for the remaining test dates to prevent missing data from resulting in exclusion from the analyses. In cases where data points were missing (n=8 control mice, from low motivation to perform the orolingual task due to water bottles mistakenly left in place overnight), those points were filled in with the mean of the preceding and following test dates. All analyses were performed using Systat (SYSTAT Software, Inc., Richmond, CA), and for all analyses α=0.05.

Statistical analyses of nominal level rotarod data consisted of multiple Fisher Exact Probability tests. Again, when a significant difference was observed for 3 consecutive test days, the third day was taken as the age at which a consistent significant difference is first observed. All probabilities were calculated in Excel (Microsoft Office) and for all analyses α=0.05.

Results

Body weight

A 2-way repeated measures analysis of variance (RM ANOVA) was used to evaluate the effects of group and time on mean body weight (Figure 1). This analysis yielded significant effects of group and time (F=4.7624, df=1, p=0.0401 and F=7.3266, df=39, p<0.0001, respectively), as well as a significant interaction effect (F=13.5318, df=39, p<0.0001). Post-hoc contrasts revealed that control and SOD1-G93A mice were similar in body weight from the onset of testing until a consistent significant difference was observed, beginning at approximately 108 days of age. From this point, an increase in body weight was observed in control mice. In contrast, body weight was largely stable in SOD1-G93A mice.

Figure 1.

Mean body weight in grams (± S.E.M.) for control and SOD1-G93A mice over time. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed significant effects of group and time, and a significant interaction effect. Post-hoc comparisons demonstrated consistent significant differences between control and SOD1-G93A mice from ~108 days of age.

Orolingual motor function

Tongue motility

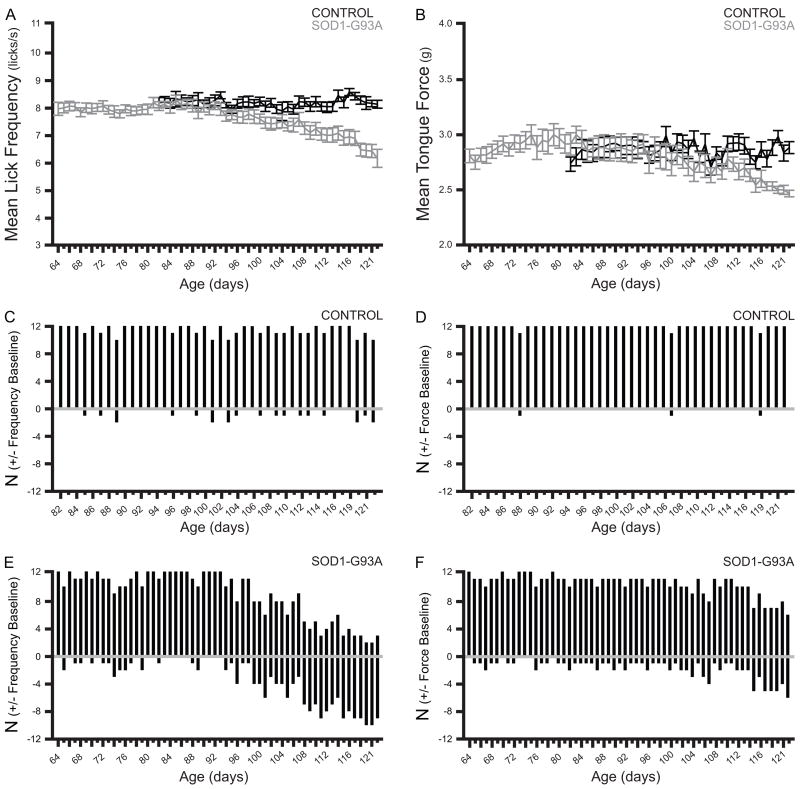

A 2-way RM ANOVA was used to evaluate the effects of group and time on mean lick frequency (Figure 2, panel A). This analysis yielded significant effects of group and time (F=11.5626, df=1, p=0.0026 and F=11.2205, df=39, p<0.0001, respectively), as well as a significant interaction effect (F=10.5587, df=39, p<0.0001). Post-hoc contrasts revealed that control and SOD1-G93A mice were similar in lick rhythm from the onset of testing until a consistent significant difference was observed, beginning at approximately 102 days of age. From this point, lick rhythm remained stable in control mice. In contrast, a progressive decrease in lick rhythm over time was observed in SOD1-G93A mice, suggesting the presence of a tongue motility deficit.

Figure 2.

Panel A: Mean lick frequency (licks/second) (± S.E.M.) for control and SOD1-G93A mice over time. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed significant effects of group and time, and a significant interaction effect. Post-hoc comparisons demonstrated consistent significant differences between control and SOD1-G93A mice from ~102 days of age. Panel B: Mean tongue force in grams (± S.E.M.) for control and SOD1-G93A mice over time. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant effect of time and a significant interaction effect. Post-hoc comparisons demonstrated consistent significant differences between control and SOD1-G93A mice from ~113 days of age. Panel C: Number of control mice performing above and below 90% of the frequency baseline over time. Gray line represents 90% of baseline. Lick rhythm was maintained above 90% of baseline in control mice. Panel D: Number of control mice performing above and below 90% of the tongue force baseline over time. Gray line represents 90% of baseline. Tongue force was maintained above 90% of baseline in control mice. Panel E: Number of SOD1-G93A mice performing above and below 90% of the frequency baseline over time. Gray line represents 90% of baseline. Lick rhythm was variable in SOD1-G93A mice, with an increasing number of mice performing below 90% of the baseline over time. Panel F: Number of SOD1-G93A mice performing above and below 90% of the tongue force baseline over time. Gray line represents 90% of baseline. Tongue force was variable in SOD1-G93A mice, with an increasing number of mice performing below 90% of the baseline over time.

Tongue force

A 2-way RM ANOVA was used to evaluate the effects of group and time on mean tongue force (Figure 2, panel B). This analysis yielded a significant effect of time (F=6.0260, df=39, p<0.0001) and a significant interaction effect (F=5.3818, df=39, p<0.0001). Post-hoc contrasts revealed that control and SOD1-G93A mice were similar in tongue force from the onset of testing until a consistent significant difference was observed, beginning at approximately 113 days of age. From this point, tongue force remained stable in control mice. In contrast, a progressive decrease in tongue force was observed in SOD1-G93A mice, suggesting weakness of the tongue musculature.

Orolingual phenotypes

When lick rhythm as a percentage of baseline performance was plotted individually (not shown) it became apparent that control mice exhibit stable lick rhythm, generally maintained above 90% of baseline. Therefore, the 90th percentile was chosen as the cut-off for normal performance. The few deviations that occurred ranged from 90-84%. However, these plots revealed that great variability existed in the SOD1-G93A group, with lick rhythm decreasing below 90% of baseline earlier, and to a greater degree, for some mice than for others. Deviations ranged from 90-45% of baseline performance. Interestingly, some mice maintained lick rhythm above 90% of baseline throughout the study, suggesting that they did not undergo a decrease in tongue motility. The numbers of control and SOD1-G93A mice performing above and below 90% of baseline are shown in Figure 2 (panels C and E). Similar findings were obtained when tongue force as a percentage of baseline performance was plotted individually (not shown). Again, the 90th percentile was chosen as the cut-off for normal performance based on the finding that control mice generally maintained tongue forces above 90% of baseline. The few deviations that occurred ranged from 90-86% of baseline performance. Great variability existed in the SOD1-G93A mice, with tongue force decreasing below 90% of baseline performance earlier, and to a greater degree, for some mice than for others. Deviations ranged from 90-77% of baseline performance. Interestingly, most SOD1-G93A mice maintained performance above 90% of baseline for the duration of the study, suggesting that they did not undergo a decrease in tongue force. The numbers of control and SOD1-G93A mice performing above and below 90% of baseline are shown in Figure 2 (panels D and F).

Next, the rhythm and force tracings of each mouse were examined to determine individual onset of rhythm and force deficits, if present. When a decrease below 90% of baseline was observed for 3 consecutive test days, the third day was taken as the age at which the consistent decrease is first observed. Results are presented in Table 1. Nine of 12 mice exhibited a motility deficit. Of these 9 mice, only 2 subsequently developed a force deficit. One of 12 mice developed a force deficit in the absence of a motility deficit. Two mice developed neither a motility nor force deficit during the course of this experiment. These results suggest that perhaps a variety of orolingual motor deficit phenotypes may exist in these animals.

Table 1. Onset of motility & force deficits in SOD1-G93A mice.

SOD1-G93A mice categorized into motility-only, force-only, or combined deficit groups. Age (in days) of deficit onset is shown in the motility and force columns.

| ID | Motility | Force | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motility-only deficit | 32 | 96 | |

| 34 | 119 | ||

| 45 | 107 | ||

| 51 | 117 | ||

| 54 | 117 | ||

| 64 | 120 | ||

| 74 | 110 | ||

|

| |||

| Force-only deficit | 40 | 82 | |

|

| |||

| Combined deficit | 31 | 110 | 120 |

| 37 | 110 | 116 | |

Grip force

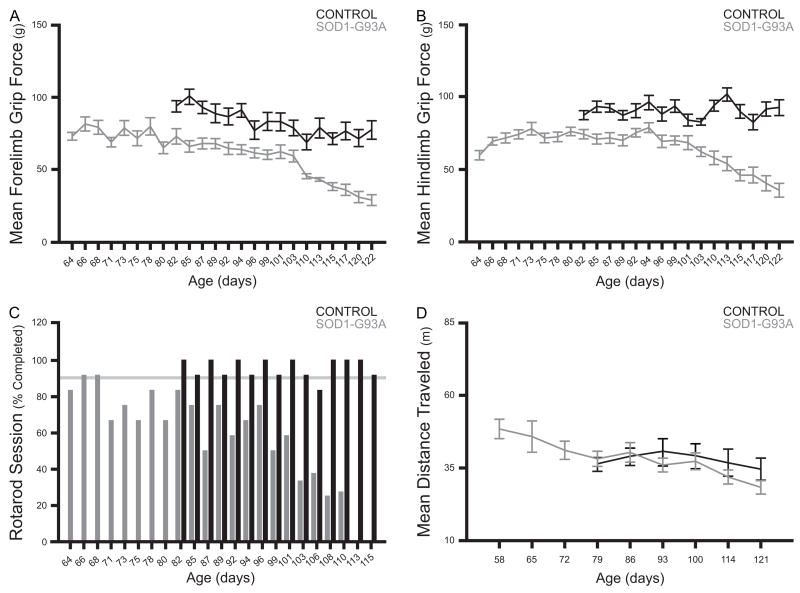

Forelimb grip force

A 2-way RM ANOVA was used to evaluate the effects of group and time on mean forelimb grip force (Figure 3, panel A). This analysis yielded significant effects of group and time (F=43.0234, df=1, p<0.0001 and F=20.6606, df=15, p<0.0001, respectively), as well as a significant interaction effect (F=3.6575, df=15, p<0.0001). Control and SOD1-G93A mice differed in forelimb grip strength from the onset of testing. Forelimb grip force remained stable in control mice. In SOD1-G93A mice, forelimb grip force was reduced significantly compared to control mice from the onset of testing, suggesting the presence of chronic forelimb muscle weakness. Additionally, a progressive decrease in forelimb grip force was observed, suggesting further weakening of the forelimb musculature.

Figure 3.

Panel A: Mean forelimb grip force in grams (± S.E.M.) for control and SOD1-G93A mice over time. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed significant effects of group and time, and a significant interaction effect. Post-hoc comparisons demonstrated consistent significant differences between control and SOD1-G93A mice from ~82 days of age. Panel B: Mean hindlimb grip force in grams (± S.E.M.) for control and SOD1-G93A mice over time. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed significant effects of group and time, and a significant interaction effect. Post-hoc comparisons demonstrated consistent significant differences between control and SOD1-G93A mice from ~82 days of age. Panel C: Percentage of control and SOD1-G93A mice that completed rotarod test sessions over time. Fisher’s exact probability tests revealed consistent significant differences between control and SOD1-G93A mice from ~113 days of age. Panel D: Mean distance traveled in meters (± S.E.M.) for control and SOD1-G93A mice over time. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant effect of time. No significant differences existed between control and SOD1-G93A mice at any time point.

Hindlimb grip force

A 2-way RM ANOVA was used to evaluate the effects of group and time on mean hindlimb grip force (Figure 3, panel B). This analysis yielded significant effects of group and time (F=60.3383, df=1, p<0.0001 and F=10.5696, df=15, p<0.0001, respectively), as well as a significant interaction effect (F=10.7215, df=15, p<0.0001). Control and SOD1-G93A mice differed in hindlimb grip strength from the onset of testing. Hindlimb grip force was stable in control mice. In SOD1-G93A mice, hindlimb grip force was reduced significantly compared to control mice from the onset of testing, suggesting the presence of chronic hindlimb muscle weakness. Additionally, a progressive decrease in hindlimb grip strength was observed, suggesting further weakening of the hindlimb musculature.

Rotarod

Fisher exact probability tests were used to make between-group comparisons at each time-point. The percentages of SOD1-G93A and control mice that successfully completed each rotarod test session are shown in Figure 3 (panel C). In control mice the performance rate was stable and generally maintained between 90–100%. In SOD1-G93A mice the performance rate was quite variable, but was consistently below 90% from 71 days of age. However, a consistent significant difference was not observed until 113 days of age, at which time none of the SOD1-G93A mice were able to successfully complete a test session.

Locomotor activity

A 2-way RM ANOVA was used to evaluate the effects of group and time on mean distance traveled (Figure 3, panel D). This analysis yielded only a significant effect of time (F=5.8374, df=5, p=0.0001). Control and SOD1-G93A mice were similar in the distance traveled in a 30 minute period over multiple test sessions. In general, the mean distance traveled decreased with successive test sessions, an effect attributed to habituation to the test environment. The lack of a significant interaction between group and time suggests that habituation rates were similar for SOD1-G93A and control mice.

Discussion

Body weight

In ALS patients, early stage weight loss is largely due to the loss of lean body mass, which is attributed to motor neuron loss (Nau et al., 1995). As the disease progresses, the loss of upper limb and oropharyngeal dexterity and strength renders solid and liquid foods difficult to manipulate and control, resulting in malnutrition, dehydration, and further weight loss (Silani et al., 1998). Additionally, the respiratory failure that occurs with disease progression increases resting energy expenditure, increasing weight loss as end stage approaches (Kasarkis et al., 1996).

Studies of SOD1-G93A mice confirm that changes in body weight occur over the course of the disease. However, the age at which these changes occur differs substantially among published studies. One study reported that both male and female SOD1-G93A mice consistently weighed significantly less than control mice from 14 days of age (Miana-Mena et al., 2005). Growth rates for SOD1-G93A and control mice were similar until a decline began in the affected mice at approximately 95 days of age. Other studies reported differences in body weight between SOD1-G93A and control mice emerging much later, from approximately 98 days to approximately 126 days (Weydt et al., 2003; Tankersley et al., 2007). Here, we observed a consistent significant difference in weight beginning at 108 days of age. However, unlike other studies, this difference arises from weight gain in the control mice. We did not observe weight loss in SOD1-G93A mice until end-stage. Our results are similar to those of Azari et al. (2003), who report stable body weight in SOD1-G93A mice from 60–114 days of age. It is possible that our water restriction regimen contributed to the differences in body weight reported in our study and previous studies.

The failure of SOD1-G93A mice to gain weight over time is likely due to muscle wasting. Indeed, limb muscle weight is significantly decreased by 90 days of age in SOD1-G93A mice (Sharp et al., 2005). To our knowledge, nutritional status has not been evaluated in these animals. However, because orolingual motor deficits are known to affect feeding, it is possible that changes in orolingual motor function are responsible, at least in part, for the lack of weight gain and subsequent weight loss in these mice. This hypothesis is consistent with disease progression in ALS patients.

Orolingual motor deficits

Corticobulbar and bulbar motor neurons of the facial, trigeminal, and hypoglossal nuclei are affected in ALS patients, resulting in weakness and atrophy of the corresponding musculature. Typically, muscles of the lips or jaw are less affected than those of the tongue (DePaul et al., 1988). Orolingual motor deficits can manifest as a variety of symptoms, including slurred speech and difficulties with chewing and swallowing. To our knowledge, no preclinical studies of orolingual motor function in ALS have been performed to date.

Hypoglossal motor neuron pathology and loss have been evaluated in SOD1-G93A mice using a variety of techniques. An early study found no significant changes in hypoglossal motor neuron number at end-stage (121–125 days of age) (Chiu et al., 1995). However, more recent studies reported significant hypoglossal motor neuron degeneration and loss at 90 days of age (Haenggeli and Kato, 2002; Angenstein et al., 2004). Most recently, quantitative T2 mapping was used to document changes in the hypoglossal nucleus as early as 70 days of age (Niessen et al., 2006). Additionally, trigeminal and facial motor neuron degeneration and loss have been documented at 90–112 days of age in SOD1-G93A mice (Haenggeli and Kato, 2002; Angenstein et al., 2004; Niessen et al., 2006). Changes in all three of these nuclei could affect orolingual motor output, however, none of these studies included behavioral assessment of orolingual motor function.

Here, we found that orolingual motor deficits are indeed present in these mice. Early on, control and SOD1-G93A mice exhibited lick frequency and tongue force values well within the range of published values (Horowitz et al., 1977; Murakami, 1977; Wang and Fowler, 1999). As the disease progressed, SOD1-G93A mice exhibited a tongue motility deficit by 100 days of age, followed by a tongue force deficit that became apparent by 115 days of age. When tongue motility and force were evaluated as a function of individual baseline performance, we found that the majority of these mice exhibited a tongue motility-only deficit. This differs from disease progression in ALS patients, in which tongue force deficits occur earlier and are more prevalent than motility deficits (DePaul et al., 1988; Mitsumoto et al., 1998; Langmore and Lehman, 1994). This difference may be explained by the lack of a tongue force challenge in this experiment. In the clinic, patients are required to exert maximal tongue force during tests of muscle integrity. Here, we observed that these mice naturally exert between 2.5–3.5 g equivalent forces, while the requirement was 1 g equivalent force. Perhaps demanding that the mice exert greater force to elicit the water reward would have revealed force deficits earlier and in more animals.

Fore- and hindlimb motor deficits

Corticospinal and spinal motor neurons are affected in ALS patients, resulting in a variety of symptoms including weakness, atrophy, fasciculations, and abnormal reflex responses in the muscles of the arms and legs (Rowland and Shneider, 2001). Thus far, most preclinical ALS studies have focused on degeneration of spinal motor neurons and related behavioral changes.

Motor neuron pathology and loss have been evaluated in depth in numerous studies. An early study reported a significant loss of lumbar and cervical spinal motor neurons at 90 days of age in SOD1-G93A mice (Chiu et al., 1995). More recent studies have shown, similarly, that significant degeneration and loss of spinal motor neurons occurs by 90–110 days of age in these mice (Guo et al., 2003; Kaspar et al., 2003; Sharp et al., 2005; Niessen et al., 2006). One study of SOD1-G93A cortical and brainstem motor neurons found a significant reduction in hindlimb region corticospinal, and bulbospinal and rubrospinal, neurons at 60 days of age, suggesting that degeneration may occur in a top-down fashion (Zang and Cheema, 2002).

Studies of muscle physiology lend support to studies demonstrating the degeneration and loss of spinal motor neurons by 90 days of age. Motor unit number was significantly decreased at 90 days of age in SOD1-G93A mice (Sharp et al., 2005). Maximal force exerted by two hindlimb muscles, measured via tetanic contraction, was significantly reduced at 90 days of age in SOD1-G93A mice when compared to control mice (Sharp et al., 2005). Physiological indications of muscle denervation (positive sharp waves and spontaneous fibrillation potentials), were detected in SOD1-G93A mice at 84 days of age (Miana-Mena et al., 2005).

Studies of muscle anatomy reveal changes occurring even earlier on. Extensive local denervation had occurred by 50 days of age in SOD1-G93A triceps surae, gluteus, and gracilus muscles (Frey et al., 2000). By 80 days of age, extensive atrophy and degeneration of muscle fibers was observed. This study and others also determined that loss of neuromuscular synapses occurred in a functional fiber type-specific manner (Pun et al., 2006; Hegedus et al., 2007). Synapses on type IIb fibers (fast fatigable) were the most susceptible, followed by those on type IIa fibers (fast, fatigue-resistant). Synapses on type I fibers (slow) were resistant until end-stage.

Many behavioral techniques, including the hanging wire, grip strength, and rotarod, have been used to evaluate disease onset and progression in SOD1-G93A mice. Several studies using a modified hanging wire test found that SOD1-G93A and control mice perform similarly from 56 days of age until time-to-fall latencies of SOD1-G93A mice decrease significantly at 98 days of age (Weydt et al; 2003; Miana-Mena et al., 2005). In contrast, other studies revealed long-standing deficits apparent at earlier time-points. Using a grip strength meter, Canton et al. (1998) demonstrated reduced combined limb grip strength in SOD1-G93A mice compared to controls from approximately 35 days of age. Another study by Canton et al. (2001) demonstrated significantly reduced combined limb grip strength in SOD1-G93A mice compared to controls from 55 days of age. One study testing rotarod performance demonstrated that SOD1-G93A mice consistently perform worse than control mice from 56 days of age (Weydt et al., 2003). However, SOD1-G93A mice were not significantly different from control mice until approximately 119 days of age when their relatively stable performance began to decline further. Together, these findings indicate the presence of long-standing chronic limb muscle weakness in SOD1-G93A mice.

To avoid masking any differences in relative onset and severity of fore- v. hindlimb involvement, we measured fore- and hindlimb grip strength, separately, from 64–122 days of age using a grip force meter. We found that both fore- and hindlimb grip strength were significantly reduced from the onset of testing. We also evaluated rotarod performance during the same time period and found that the performance rate was reduced from ~71 days of age, although it was not consistently significantly different until 113 days of age (due in part to the use of non-parametric tests and our conservative definition of a consistent significant difference). Our findings are in agreement with those of Canton et al. (1998; 2001) and Weydt et al. (2003), which also demonstrated the presence of chronic limb muscle weakness. Interestingly, we found that SOD1-G93A and control mice exhibited similar levels of locomotor activity, even at end-stage, despite early deficits in grip strength and rotarod performance. Perhaps these seemingly conflicting findings may be explained by the early loss of type II (fast) muscle fibers, which produce the greatest force, and the disease-resistance of type I (slow) muscle fibers, which produce the least force (Frey et al., 2000; Pun et al., 2006; Hegedus et al., 2007). The early loss of type II fibers may result in early deficits in strength-challenging tasks, such as grip force and rotarod, while the maintenance of slow fibers through end-stage may result in relatively normal performance on non-challenging tasks such as locomotor activity. These findings differ somewhat from the human condition, in which muscle biopsies occasionally have demonstrated a type I or type II fiber dominance (Krivickas et al., 2002; Baloh et al., 2007).

Conclusion

When considering any findings in the context of the published literature, it is important to bear in mind that they may or may not extend to other fALS models currently available for study. As mentioned above, there are 2 transgenic lines of SOD1-G93A mice that differ in disease onset and progression. Within-line sex-based differences in disease onset and progression have been identified in at least two studies (Miana-Mena et al., 2005; Veldink et al., 2003). Additionally, another SOD1 mutant model carrying the G86R mutation is available for study. This mutation results in dramatically different effects on brainstem motor nuclei when compared with the G93A mutation (Nimchinsky et al., 2000). These differences within and between ALS models may account for discrepancies in the literature and prove important in future studies.

Here, we found that female SOD1-G93A mice exhibited chronic fore- and hindlimb muscle weakness apparent by 64 days of age. This early deficit likely contributed to the decreased rotarod performance rate apparent by 71 days of age. Interestingly, limb muscle weakness did not result in decreased locomotor activity, even near end-stage. Orolingual deficits appeared much later in these animals, with a tongue motility deficit apparent by 100 days of age followed by a tongue force deficit apparent by 115 days of age. The later emergence of the tongue force deficit suggests that the chronic muscle weakness observed in the limbs did not extend to the tongue musculature. However, this hypothesis awaits a direct test using a tongue force challenge.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants AG023549, AG026491 to J.A.S., and by the Kansas Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center (HD02528). The authors wish to thank Dr. Stephen Fowler for his assistance with MATLAB programming.

List of abbreviations (alphabetical order)

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- fALS

familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- RM ANOVA

repeated measures analysis of variance

- SOD1

superoxide-dismutase 1

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Literature Cited

- Angenstein F, Niessen HG, Goldschmidt J, Vielhaber S, Ludolph AC, Scheich H. Age-dependent changes in MRI of motor brain stem nuclei in a mouse model of ALS. Neuroreport. 2004;15:2271–2274. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200410050-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azari MF, Lopes EC, Stubna C, Turner BJ, Zang D, Nicola NA, Kurek JB, Cheema SS. Behavioral and anatomical effects of systemically administered leukemia inhibitory factor in the SOD1G93A G1H mouse model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain Res. 2003;982:92–97. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02989-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baloh RH, Rakowicz W, Gardner R, Pestronk A. Frequent atrophic groups with mixed-type myofibers is distinctive to motor neuron syndromes. Muscle Nerve. 2007;36:107–110. doi: 10.1002/mus.20755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canton T, Bohme GA, Boireau A, Bordier F, Mignani S, Jimonet P, Jahn G, Alavijeh M, Stygall J, Roberts S, Brealey C, Vuilhorgne M, Debono M-W, Le Guern S, Laville M, Briet D, Roux M, Stutzmann J-M, Pratt J. RPR 119990, a novel alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazoleproprionic acid antagonist: synthesis, pharmacological properties, and activity in an animal model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. JPET. 2001;299:314–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canton T, Pratt J, Stutzmann J-M, Imperato A, Boireau A. Glutamate uptake is decreased tardively in the spinal cord of FALS mice. Neuroreport. 1998;9:775–778. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199803300-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu AY, Zhai P, Dal Canto MC, Peters TM, Kwon YW, Prattis SM, Gurney ME. Age-dependent penetrance of disease in a transgenic mouse model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1995;6:349–362. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1995.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Canto MC, Gurney ME. Development of central nervous system pathology in a murine transgenic model of human amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:1271–1279. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng HX, Hentati A, Tainer JA, Iqbal Z, Cayabyab A, Hung WY. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and structural defects in Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase. Science. 1993;261:1047–1051. doi: 10.1126/science.8351519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePaul R, Abbs JH, Caligiuri M, Gracco VL, Brooks BR. Hypoglossal, trigeminal, and facial motoneuron involvement in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 1988;38:281–283. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.2.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler SC, Birkestrand BR, Chen R, Moss SJ, Vorontsova E, Wang G, Zarcone TJ. A force-plate actomter for quantitating rodent behaviors: illustrative data on locomotion, rotation, spatial patterning, stereotypies, and tremor. J Neurosci Methods. 2001;107:107–124. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(01)00359-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler SC, Wang G. Chronic haloperidol produces a time- and dose-related slowing of lick rhythm in rats: implications for rodent models of tardive dyskinesia and neuroleptic-induced parkinsonism. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998;137:50–60. doi: 10.1007/s002130050592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey D, Schneider C, Xu L, Borg J, Spooren W, Caroni P. Early and selective loss of neuromuscular synapse subtypes with low sprouting competence in motoneuron diseases. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2534–2542. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-07-02534.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H, Lai L, Butchbach MER, Stockinger MP, Shan X, Bishop GA, Lin C-LG. Increased expression of the glial glutamate transport EAAT2 modulates excitotoxicity and delays the onset but not the outcome of ALS in mice. Human Molecular Genetics. 2003;12:2519–2532. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurney ME, Pu H, Chiu AY, Dal Canto MC, Polchow CY, Alexander DD, Caliendo J, Hentati A, Kwon YW, Deng HX, et al. Motor neuron degeneration in mice that express a human Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase mutation. Science. 1994;264:1772–1775. doi: 10.1126/science.8209258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haenggeli C, Kato AC. Differential vulnerability of cranial motoneurons in mouse models with motor neuron degeneration. Neurosci Lett. 2002;335:39–43. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)01140-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegedus J, Putman CT, Gordon T. Time course of preferential motor unit loss in the SOD1(G93A) mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol Dis. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.07.003. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz GP, Stephan FK, Smith JC, Whitney G. Genetic and environmental variability in lick rates of mice. Physiol Behav. 1977;19:493–496. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(77)90224-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hottinger AF, Fine EG, Gurney ME, Zurn AD, Aebischer P. The copper chelator d-penicillamine delays onset of disease and extends survival in a transgenic mouse model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur J Neurosci. 1997;9:1548–1551. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasarkis EJ, Berryman S, Vanderleest JG, Schneider AR, McClain CJ. Nutritional status of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: relation to the proximity of death. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;63:130–137. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/63.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaspar BK, Llado J, Sherkat N, Rothstein JD, Gage FH. Retrograde viral delivery of IGF-1 prolongs survival in a mouse ALS model. Science. 2003;301:839–842. doi: 10.1126/science.1086137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong J, Xu Z. Massive mitochondrial degeneration in motor neurons triggers the onset of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in mice expressing a mutant SOD1. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3241–3250. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-09-03241.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krivickas LS, Yang J-I, Kim S-K, Frontera WR. Skeletal muscle fiber function and rate of disease progression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve. 2002;26:636–643. doi: 10.1002/mus.10257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmore SE, Lehman ME. Physiologic deficits in the orofacial system underlying dysarthria in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Speech Hear Res. 1994;37:28–37. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3701.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miana-Mena FJ, Munoz MJ, Yague G, Mendez M, Moreno M, Ciriza J, Zaragoza P, Osta R. Optimal methods to characterize the G93A mouse model of ALS. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. 2005;6:55–62. doi: 10.1080/14660820510026162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millecamps S, Nicolle D, Ceballos-Picot I, Mallet J, Barkats M. Synaptic sprouting increases the uptake capacities of motoneurons in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mice. PNAS. 2001;98:7582–7587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131031098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsumoto H, Chad DA, Pioro EP. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. F.A. Davis Company; Philadelphia, PA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Murakami H. Rhythmometry on licking rate of the mouse. Physiol Behav. 1977;19:735–738. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(77)90307-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nau KL, Bromberg MB, Forshew DA, Katch VL. Individuals with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis are in caloric balance despite losses in mass. J Neurol Sci. 1995;129:47–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(95)00061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niessen HG, Angenstein F, Sander K, Kunz WS, Teuchert M, Ludolph AC, Heinze H-J, Scheich H, Vielhaber S. In vivo quantification of spinal and bulbar motor neuron degeneration in the G93A-SOD1 transgenic mouse model of ALS by T2 relaxation time and apparent diffusion coefficient. Exp Neurol. 2006;201:293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimchinsky EA, Young WG, Yeung G, Shah RA, Gordon JW, Bloom FE, Morrison JH, Hof PR. Differential vulnerability of oculomotor, facial, and hypoglossal nuclei in G86R superoxide dismutase transgenic mice. J Comp Neurol. 2000;416:112–125. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000103)416:1<112::aid-cne9>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pun S, Santos AF, Saxena S, Xu L, Caroni P. Selective vulnerability and pruning of phasic motoneuron axons in motoneuron disease alleviated by CNTF. Nature Neuoscience. 2006;9:408–419. doi: 10.1038/nn1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen AD. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: clinical features and prognosis. Arch Neurol. 1978;35:638–642. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1978.00500340014003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen DR. Mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature. 1993;364:362. doi: 10.1038/364362c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland LP, Shneider NA. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;344:1688–1701. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105313442207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp PS, Dick JRT, Greensmith L. The effect of peripheral nerve injury on disease progression in the SOD1(G93A) mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuroscience. 2005;130:897–910. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silani V, Kasarskis EJ, Yanagisawa N. Nutritional management in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a world-wide perspective. J Neurol. 1998;245:S13–19. doi: 10.1007/pl00014805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tankersley CG, Haenggeli C, Rothstein JD. Respiratory impairment in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102:926–932. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00193.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travers JB, Dinardo LA, Karimnamazi H. Motor and premotor mechanisms of licking. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1997;21:631–647. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(96)00045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldink JH, Bar PR, Joosten EA, Otten M, Wokke JH, van den Berg LH. Sexual differences in onset of disease and response to exercise in a transgenic model of ALS. Neuromuscul Disord. 2003;13:737–743. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(03)00104-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Fowler SC. Effects of haloperidol and clozapine on tongue dynamics during licking in CD-1, BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice. Psychopharmacology. 1999;147:38–45. doi: 10.1007/s002130051140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weydt P, Hong SY, Kliot M, Moller T. Assessing disease onset and progression in the SOD1 mouse model of ALS. Neuroreport. 2003;14:1051–1054. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000073685.00308.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim MB, Kang J-H, Yim H-S, Kwak H-S, Chock PB, Stadtman ER. A gain-of-function of an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-associated Cu, Zn-superoxide dismutase mutant: an enhancement of free radical formation due to a decrease in Km for hydrogen peroxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:5709–5714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zang DW, Cheema SS. Degeneration of corticospinal and bulbospinal systems in the superoxide dismutase 1G93A G1H transgenic mouse model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurosci Lett. 2002;332:99–102. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00944-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]