Abstract

Objective

Approximately 25% of all general dentists practicing in the United States use a computer in the dental operatory. Only 1.8% maintain completely electronic records. Anecdotal evidence suggests that dental computer-based patient records (CPR) do not represent clinical information with the same degree of completeness and fidelity as paper records. The objective of this study was to develop a basic content model for clinical information in paper-based records and examine its degree of coverage by CPRs.

Design

We compiled a baseline dental record (BDR) from a purposive sample of 10 paper record formats (two from dental schools and four each from dental practices and commercial sources). We extracted all clinical data fields, removed duplicates, and organized the resulting collection in categories/subcategories. We then mapped the fields in four market-leading dental CPRs to the BDR.

Measurements

We calculated frequency counts of BDR categories and data fields for all paper-based and computer-based record formats, and cross-mapped information coverage at both the category and the data field level.

Results

The BDR had 20 categories and 363 data fields. On average, paper records and CPRs contained 14 categories, and 210 and 174 fields, respectively. Only 72, or 20%, of the BDR fields occurred in five or more paper records. Categories related to diagnosis were missing from most paper-based and computer-based record formats. The CPRs rarely used the category names and groupings of data fields common in paper formats.

Conclusion

Existing paper records exhibit limited agreement on what information dental records should contain. The CPRs only cover this information partially, and may thus impede the adoption of electronic patient records.

Introduction

Although most dentists in the United States use computers for administration and billing, far fewer do so for clinical purposes. As of 2000, 85.1% of all dentists in the United States were using a computer in their office. 1 One of our recent studies 2 showed that 25% of all general dentists in the United States use a computer in the clinical environment (i.e., in the dental operatory). Nevertheless, only 1.8% maintain completely computer-based patient records (CPRs). To some degree, this situation mirrors the situation in medicine. Burt and Hing 3 found that although 73% of physician offices used computers for billing, only 17% used them for maintaining medical records and 8% for ordering prescriptions. The proportion of U.S. physicians who have adopted electronic health records is estimated to be between 20% and 25%. 4,5

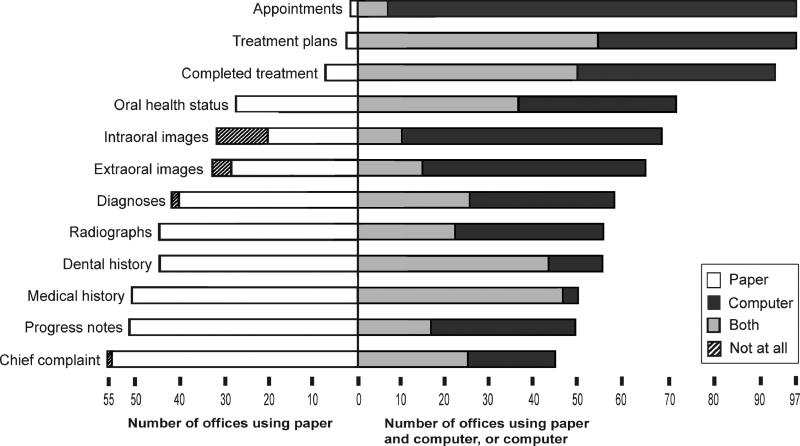

Similar to physicians, 6 dentists are struggling with implementing clinical systems. The “persistence of paper” is a common problem in computerized physician order entry system implementations 6 ; there is evidence that the situation is similar with respect to dentists’ efforts to implement CPRs. As our study showed, 2 only 1.8% of all general dental practices are paperless; all others stored patient information both on paper and electronically, often with significant overlap. As ▶ illustrates, clinical information associated with administration and billing, such as appointments and treatment plans, was stored predominantly on the computer, whereas other information, such as the medical history and progress notes, primarily resided on paper. As Mikkelsen 7 and Stausberg 8 found, the parallel use of electronic and paper-based patient records can cause inconsistencies in clinical documentation. This circumstance, in turn, can lead to a lack of relevant clinical information that can affect patient care decisions and may negatively impact care outcomes. 9,10

Figure 1.

Storage of major clinical information categories on paper/computer, sorted by utilization of computer-based storage in descending order. Paper = information stored only on paper; computer = information stored only on the computer; both = information on paper duplicated on the computer; not at all = information not recorded at all. Reprinted with permission. 2

There are several reasons why paper persists even in dental practices that have implemented CPRs. An important one is that commercial software often cannot accommodate all types of patient information that the dentist wants to record. 2 This certainly is the case with new information, such as the output of novel diagnostic devices, which did not exist before system design. Nevertheless, it also applies to information that has been part of the dental record for a long time. Evidence for such weaknesses in representation and content were also found by Atkinson et al., 11 who evaluated six commercial CPRs for use in a dental school clinic setting. The primary features of the systems centered on treatment planning, documentation of completed procedures, financial transactions, and scheduling, i.e., functions that closely relate to administration. At the same time, the systems were found to be deficient in, among other aspects, the medical and dental history, examination results, radiographic interpretation, quality assurance, and a coding system for dental diagnoses, i.e., concerns that closely relate to clinical care. Similar variations in the ability of CPRs to document specific types of information also have been found in medicine. For instance, a CPR for pediatrics studied by Roukema et al. 12 was more suitable for documenting physical examination findings than the patient history.

To determine what information dental records, both paper-based and computer-based, should contain, examining the structure and content of current paper records may be warranted. Previous studies have shown that both the format as well as the content of paper records used in dental practice differ significantly. 13,14 In a study of a random sample of general dentists in Florida, 13 forms that were considered part of complete dental records were used by between 20% and 96% of all respondents. A comparison of dental schools and practitioner health history forms showed that, in general, dental school forms were longer and more complete. 14

As of this writing, no detailed standard for the format and content of patient records in dentistry, such as the ASTM E1384 Practice for Content and Structure of the Electronic Health Record standard in medicine, 15 exists. Several resources 16,17 offer general guidance on what a dental record for general practice should contain. For instance, the Faculty of General Dental Practitioners in the United Kingdom requires the patient’s demographic information, the medical and dental history, an examination of the dentofacial area, an initial dental examination, a treatment plan, and progress notes to be part of the patient record. 16

The absence of a comprehensive reference about what information general dental patient records should contain required us to pursue two goals in the study we report in this article. The first goal was to develop a basic but representative model of information in paper-based records. The second goal was to answer the question to what degree the four market-leading dental CPRs represented that content. The answer to this question is significant because incomplete clinical content coverage may act as a barrier to CPR adoption, as the studies presented above suggest. A better understanding of the current strengths and weaknesses of clinical content coverage in dental CPRs can help information technology (IT) vendors improve their products and dental practitioners evaluate and select CPRs.

Methods

To develop a basic, representative model of information in paper-based records, we first constructed a “consensus” record that represented the usual and customary content of patient records in general dental practice. For the purposes of this article, we have termed this consensus record the baseline dental record (BDR). In the second phase, we mapped the information contained in each of the four market-leading dental CPRs in the United States to the information in the BDR. It is important to note that we focused only on clinical data fields in this study. Although the boundary between administrative and clinical information is somewhat fluid (patient age, for instance, could be considered to be both), we addressed the problem by only using clinical data forms (such as the health history form and intraoral chart) to construct the BDR. We examined information coverage by CPRs both at the level of single data fields (e.g., blood pressure) as well as categories of data fields (e.g., vital signs). In our opinion, this approach presents a meaningful way of comparing record formats because records can be contrasted at multiple levels of granularity. We first describe how we developed the BDR.

Development of the BDR

Based on our literature review, we expected significant variation in the content of dental records used by individual practitioners in various settings. Therefore, we assembled a purposive sample of 10 paper record formats: four from practicing dentists (one from Pittsburgh, one from Orlando and two from San Juan, Puerto Rico), two from dental schools (University of Pittsburgh School of Dental Medicine and University of Puerto Rico School of Dentistry), and four from commercial vendors (Colwell Systems, Shoreview, MN; Rapidforms, Inc., Thorofare, NJ; SmartHealth, Inc., Phoenix, AZ; The Dental Record, Wisconsin Dental Association, Milwaukee, WI) to develop the BDR. To help compensate for any local or institutional idiosyncrasies in the content of the paper records, we also consulted three textbooks 18–20 that covered various content areas of dental records.

To develop the BDR, we extracted and categorized all data fields from the source records. We defined a data field as the combination of a descriptive label, such as “Chief complaint,” with a space or area in which the clinician could record a textual, numeric, or symbolic value. For findings and planned procedures in the intraoral chart, we used the numbers, text, annotations, and symbols described by the textbooks as possible values. We excluded data fields that only applied to a specific care context (e.g., “Faculty” and “Student” fields in the progress note forms from dental schools) or that served primarily administrative and financial functions (such as “Patient name” and “Fees”). In addition, we eliminated fields that essentially duplicated the format, content, or intent of other fields.

We followed up the organization of patient information in the paper records and textbooks as much as possible in organizing the data fields. Most of the resulting categories, such as “Chief complaint,” “Medical history,” “Dental history,” “Hard tissue and periodontal chart,” “Radiographic findings,” “Treatment plan,” and “Progress notes,” will be familiar to any clinician. Where appropriate, we specified subcategories; for instance, the BDR category “Medical history” contains the subcategories “Past and present illnesses,” “Health history (problems),” “Allergies,” “Women only,” and “Vital signs.” The categories and subcategories of the BDR resemble those used in earlier empirical studies analyzing the use of dental records. 13,21,22

To provide some validity to our categorization of data fields, we mapped the top-level BDR categories to the American National Standards Institute/American Dental Association Specification No. 1000: Standard Clinical Data Architecture for the Structure and Content of an Electronic Health Record (ANSI/ADA 1000 Specification). 23 The ANSI/ADA 1000 Specification, published by the ADA Standards Committee for Dental Informatics (SCDI), contains a logical data model for the content of electronic health records. The specification includes a hierarchical decomposition of the health care process, which is augmented by a content model of the data fields associated with that process. The section “Provide clinical services” of the process model covers the delivery of clinical care and is divided into four parts: (1) obtain clinical data, (2) determine health status, (3) determine service plan, and (4) deliver patient care. By mapping the BDR categories to the ANSI/ADA 1000 Specification, we wanted to ensure that we did not inadvertently create categories that were not part of this widely accepted standard.

We illustrate this process using fields describing conditions of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). We extracted the following fields related to the TMJ from the BDR source records: “TMJ evaluation,” “Jaw sounds/pain,” “Deviation on closing,” “Tenderness to palpation,” “Maximum opening,” “Previous TMJ therapy,” “Requires further TMJ evaluation,” “Difficulty opening/closing,” “Difficulty chewing,” and “Muscles.” We grouped those fields in the subcategory “Temporomandibular joint (TMJ).” The TMJ examination is part of the diagnostic workup, and we thus assigned it to the part “Obtain clinical data” of the ANSI/ADA 1000 Specification.

The only category for which this process was not feasible was the “Hard tissue and periodontal chart.” The corresponding paper forms consist, mainly, of tooth diagrams that clinicians annotate using symbols, numbers, and text. 24 Although some general conventions for charting exist, such as using the color red to indicate a problem, there is no standardized set of what information to chart. Thus, we could not extract data fields from those forms as we did for others. We therefore used two textbooks on clinical charting 19,25 as reference guides to determine which findings, such as “caries,” “fractured tooth,” and “existing restoration,” to include in the BDR. We selected 26 common hard tissue and 28 common periodontal findings from the textbooks. We used the ADA’s Current Dental Terminology (CDT) 26 as the source for representative procedures. The CDT is the set of codes used by virtually all dentists for third-party billing. We selected 20 commonly used procedures/groups of procedures, such as “amalgam restoration,” “implant,” and “crown,” from the CDT to represent procedures in the BDR. Because we had to treat findings and procedures differently from other data fields, they are not included in the totals of the BDR.

The BDR should not be understood as a gold standard for record-keeping in dental practice. It is simply an empirical collection of data fields compiled from 10 paper-based record formats, verified by a review of three textbooks, without a judgment of the value or relevance of these fields to clinical practice.

Comparison of Paper and Electronic Record Formats with the BDR

After developing the BDR, we selected four dental CPRs for the comparison. The programs were Dentrix V. 10.0.36.0 (Dentrix Dental Systems, American Fork, UT), EagleSoft V. 10.08 (Patterson Dental, St. Paul, MN), and SoftDent V. 10.0.2.94 and PracticeWorks V. 5.0.2.034 (both Kodak Corp., Rochester, NY). The four programs are dental CPRs, and, taken together, have 80% of the market among general dentists who are using computers at chairside. 2 We installed working demonstration versions of the applications according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Although all of the systems can be customized to some degree to suit the preferences of the user (for instance, in terms of what information is displayed in the clinical chart), we evaluated them in the default mode because it can reasonably be expected that this is how most dentists will first use them. One of the investigators (P.H.) learned the features and functions of each CPR with the help of the printed program documentation and online help, and entered simulated patient information into each system to explore all clinical data fields.

We then compared the information content of the four CPRs to the BDR. For each data field in the BDR, we first checked whether a corresponding field with an identical label could be found in the system under comparison. If that was not the case, we looked for a label that either was a synonym of the BDR label (e.g., “heart rate” and “pulse”) or clearly communicated the same intent (e.g., “chief complaint” and “reason for your visit”). If one of those conditions was met, we marked the BDR element as “present” in the respective system; otherwise as “absent.” In mapping the BDR to the CPR, we only measured the presence or absence of each field, and not whether data type or possible values were the same. (For instance, we only noted the presence of the data field “pain” in the assessment of the temporomandibular joint, but not whether the possible values were “yes/no” or “slight/moderate/severe.”) If at least one data field in a category was present in the program, we marked the category as present.

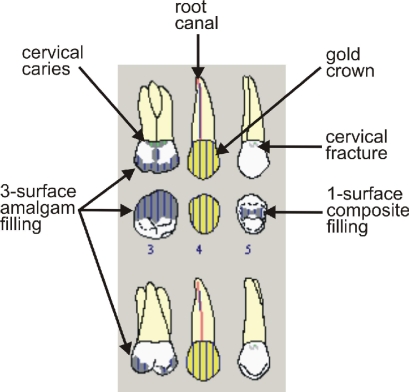

To determine how well the CPRs represented findings and procedures, we attempted to record each selected finding/procedure on the appropriate chart (either “hard tissue” or “periodontal”). We regarded each information item as “chartable” if the graphical chart displayed a symbol, text string, or other notation in response to the entry. (See ▶ for a sample section of a hard tissue chart.) Some programs display information that cannot be charted graphically in a table below the chart; however, this capability did not meet our criteria for representation.

Figure 2.

Sample section of a dental hard tissue chart illustrating findings (such as “cervical caries”) and procedures (such as “root canal”).

Once all programs had been analyzed, we prepared summary figures and tables showing the characteristics of the BDR and the mapping to CPRs. We verified those results with the CPR vendors to ensure that we had not overlooked any system capabilities for storing clinical information. In our results, we also included how each paper source format mapped to the BDR to provide information about the relative agreement of paper records. A Web appendix (available at www.jamia.org) provides the raw data for the record format comparisons. In the Web appendix, we also list fields that were found only in the CPRs. We omit a description of those fields in this article because of space reasons.

Results

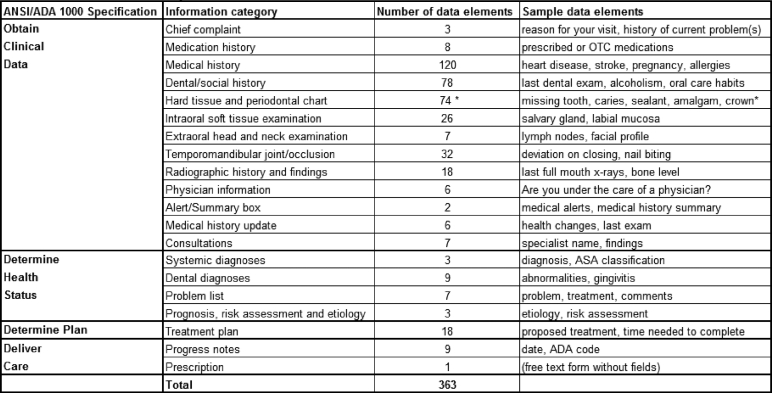

▶ provides a summary of the BDR, listing the information categories, the number of data fields in each (including representative examples where appropriate), and how the information categories were mapped to the sections of the ANSI/ADA 1000 Specification. The BDR has 20 main categories, most of which fall under the “Obtain clinical data” section of the ANSI/ADA 1000 Specification, and 363 data fields (excluding findings and procedures on the hard tissue and periodontal chart). Within the data fields, we observed several data types, such as free text (sample data fields: “Chief oral complaint” and “List any prescribed (or over-the-counter) drugs”), yes/no answers (sample data fields: “Angina,” “Skin rash,” and “Ulcers or colitis”), check boxes (sample data fields: “Pulse rhythm: □ regular □ irregular”), numbers (sample data field: “Pulse rate”) and date (sample data field: “Date of last dental visit”). In some categories, such as the “Medication history,” some record formats provide free-text fields (e.g., “List any prescribed (or over-the-counter) drugs”), whereas others list answer categories (e.g., “Anticoagulants”) or items (e.g., “Aspirin”). We retained these variations in documenting patient information to provide an accurate reflection of the source records. In the BDR, particularly large numbers of data fields appear in the categories “Medical history,” “Dental/social history,” “Temporomandibular joint/occlusion,” “Intraoral soft tissue examination,” and “Radiographic history and findings.”

Table 1.

Table 1 Summary of Information in the Baseline Dental Record (BDR)

|

The table lists the 20 general information categories typically contained in dental records, the number of corresponding data fields and sample data fields. The table also specifies which section of the ANSI/ADA 1000 specification each information category belongs to. *: selected possible values for “Findings” and “Planned Procedures.”

Representation of the BDR in Paper-based Records

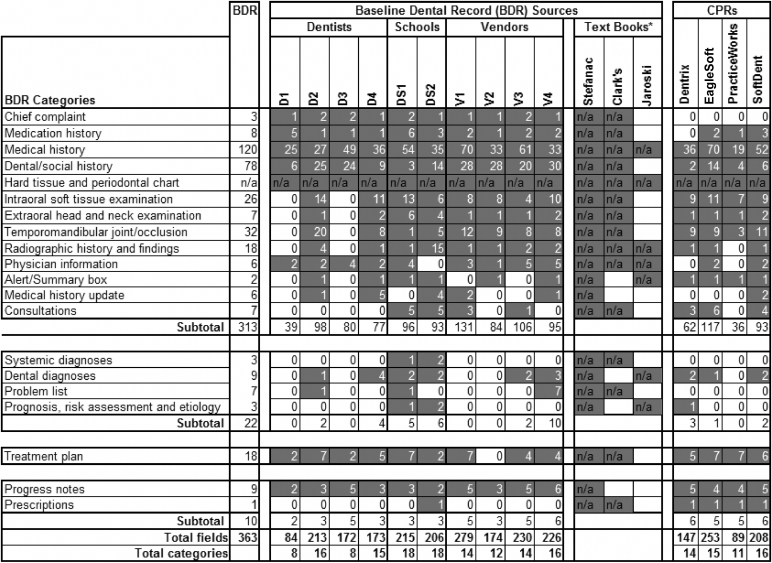

▶ shows a summary of how each paper-based and computer-based patient record format covers the information contained in the BDR. We first discuss the representation of information in the BDR among paper-based record formats. As the columns titled “Baseline dental record (BDR) sources” show, paper-based formats are not uniform in their coverage of clinical information. The BDR categories “Chief complaint,” “Medication history,” “Medical history,” “Dental/social history,” “Physician information,” “Treatment plan,” and “Progress notes” are represented in virtually all paper records. Other categories, such as “Intraoral soft tissue examination,” “Alert/summary box,” “Medical history update,” and “Dental diagnoses” are found in most paper records. The categories contained in the fewest paper records include “Systemic diagnoses,” the “Problem list,” “Prognosis, risk assessment, and etiology,” and “Prescriptions.” (The category “Prescriptions” is an outlier because it is common practice for dentists to document prescriptions in the progress notes and/or by retaining a copy of the prescription[s]. The absence of a separate form for prescriptions was therefore expected.) In total, the paper-based record formats contained between eight and 18 of the BDR categories, with a mean of 13.9. Dental school records contained more categories 18 than either dentists’ 12 and vendors’ 14 records, and also had more comprehensive health history forms (average number of fields in medical history: dentists, 34; dental schools, 45; vendors, 49).

Table 2.

Table 2 Mapping of Data Fields in Paper- and Computer-based Patient Records to BDR Categories

|

Each cell lists the number of data fields contained in each record format. Cells containing values greater than zero are shaded for better readability. Data fields are not reported for textbooks, since typically they do not provide patient record forms, and for the category “Hard Tissue and Periodontal Chart,” since paper forms combine a limited number of fields with free-form entries.

A comprehensive, standard textbook on treatment planning in dentistry 20 covered all information categories of the BDR, whereas a more general work on clinical dentistry 18 covered most of them. A book on clinical charting 19 focused only on a few categories of findings and diagnoses.

The paper records contain between 172 and 279 fields, with an average of 210 fields (omitting an outlier paper format [D1] that covered fewer than half the data fields of any other record). Records from dentists (excluding D1) average 186 fields, dental schools 211 fields, and vendors 227 fields. The number of fields in paper-based formats varies within each category. For instance, the “Alert/summary box” consists of only 1 free-text field in all records. The “Chief complaint” includes 1 or more of 3 fields in the BDR (the “Chief oral complaint,” “Do you have any discomfort/problems?” and “History of chief complaint”). At the other end of the spectrum, paper-based formats contain between 25 and 70 of a total of 120 fields in the BDR’s “Medical history.”

A quantitative comparison of data fields is made difficult by the fact that the granularity of the data fields is not equivalent. For instance, the “Medication history” in all paper records includes a free-text field “List any prescribed (or over-the-counter) drugs”; some formats offer additional discrete choices, such as drug categories (e.g., “Tranquilizers”) and single drugs (e.g., “Cortisone” and “Fen-Phen/Redux”). Another example for different levels of granularity is the “Temporomandibular joint/occlusion” category, which includes a general data field for “TMJ evaluation” in seven records. Several of those offer the capability to record additional detail, such as “Jaw sounds/pain,” “Deviation on closing,” and “Difficulty chewing.”

Based on the frequency with which specific fields are observed in our sample, the relative importance of data fields varies. For instance, almost all paper records contain at least one data field describing the patient’s chief complaint, medication history, and allergies. Nevertheless, other findings relevant to general and dental health (number of occurrences in brackets, maximum = 10), such as “Blood pressure” [6], “Alcohol” [3], and “Chemotherapy/Radiotherapy” [7], are not found in all paper records. The category “Past and present illnesses” illustrates this point very well. The BDR contains a total of 89 fields for this category, of which only 31 appear in five or more of the paper-based records; 47 appear in only one or two paper-based formats (examples: “Prosthetic valves or joints,” “Syphilis,” and “Tobacco habit”).

Representation of the BDR in Computer-based Records

Viewed from the aspect of categories, the CPRs’ coverage of the BDR information was similar to that of paper records (▶). The four CPRs contained between 11 and 16 of the categories, with a mean of 14. The average number of fields for all CPRs was 174. The three categories that were completely absent in CPRs were “Chief complaint,” “Systemic diagnoses,” and “Problem list.” All other categories, with the exception of “Medication history,” “Radiographic history and findings,” “Physician information,” “Medical history update,” “Consultations,” “Dental diagnoses,” and “Prognosis, risk assessment, and etiology” were represented in all CPRs.

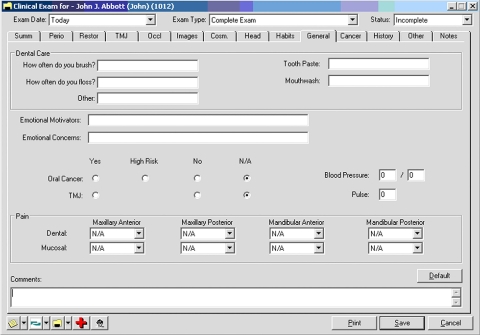

During the review, we noted that CPRs often do not use the same labels for categories common in paper records. For instance, the label “Medical history” was only found in EagleSoft and SoftDent, whereas Dentrix and PracticeWorks provided only a “Medical alert” field. “Progress notes” was contained only in Dentrix, and “Extraoral head and neck exam” and “Dental history” in none of the CPRs. Not only did CPRs rarely use the category labels common in paper records, but also data fields typically grouped in a category on paper were often spread out over multiple dialog boxes and tabs in the programs. This design necessitated a screen-by-screen, field-by-field review of each CPR to match the information content to the BDR. One example is the clinical exam in EagleSoft (▶), in which the tabs “Habits,” “General,” and “History” contain items typically associated with the category “Dental and social history.”

Figure 3.

Clinical examination dialog box in EagleSoft. The tabs “Habits,” “General,” and “History” contain items typically contained in a section called “Dental and social history” on paper forms.

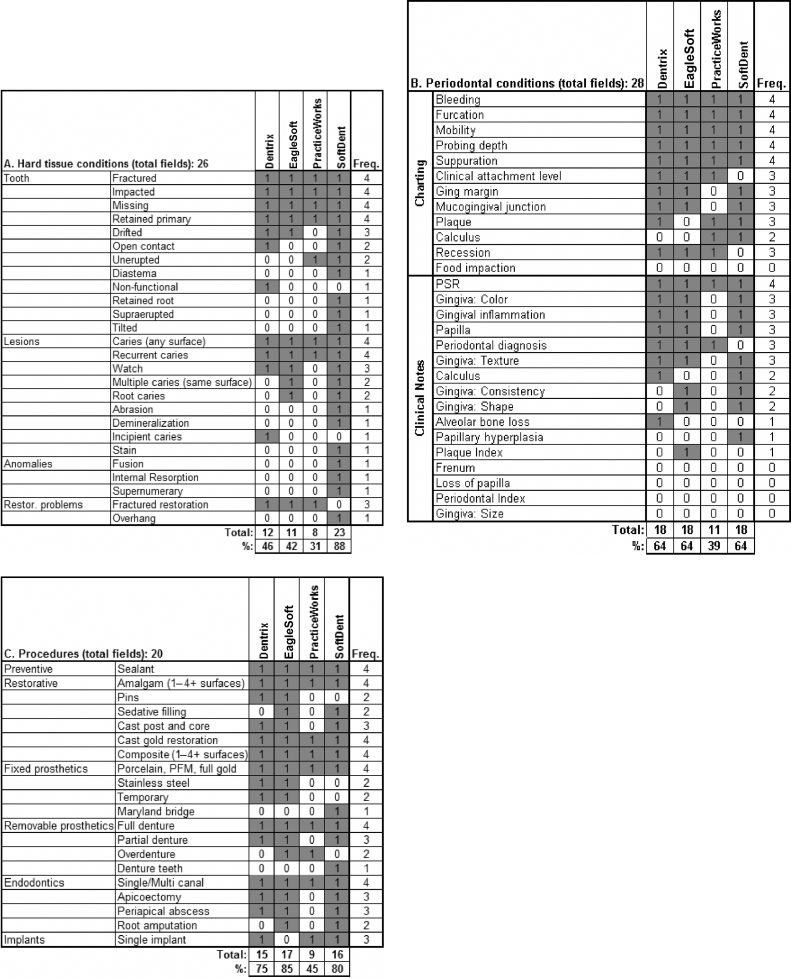

As noted in the Methods section, we could not follow up the process of mapping data fields between paper-based and computer-based records for the category “Hard tissue and periodontal chart.” ▶ shows which CPRs displayed a symbol, text string, or other notation on the respective chart in response to the entry of a finding or procedure. Of the hard tissue findings, six common conditions, such as “Missing tooth” and “Caries,” could be charted in all 4 CPRs. Most other conditions could only be charted in SoftDent because SoftDent was the only application that implemented textual annotations for each single tooth. The other CPRs used predominantly symbols to chart conditions. Because the universe of potentially usable symbols is much more constrained than free text, they could chart fewer conditions than SoftDent. The proportion of chartable hard tissue conditions ranged from 31% to 88%. The review of the periodontal portion resulted in similar findings. Six of the 28 conditions could be charted in all systems, whereas 5 could not be charted at all. The range of chartable periodontal conditions was 39% to 64%. The coverage of procedures in the CPRs was, in general, better. Seven of the 20 procedures could be charted in all CPRs. The range of chartable procedures was between 45% and 85%.

Table 3.

Table 3 Ability of Four CPRs to Record Selected Findings and Procedures in the Category “Hard Tissue and Periodontal Chart.” A. 26 Hard Tissue Conditions (Conditions Associated with Teeth). B. 28 Periodontal Conditions. C. 20 Treatment Procedures.

|

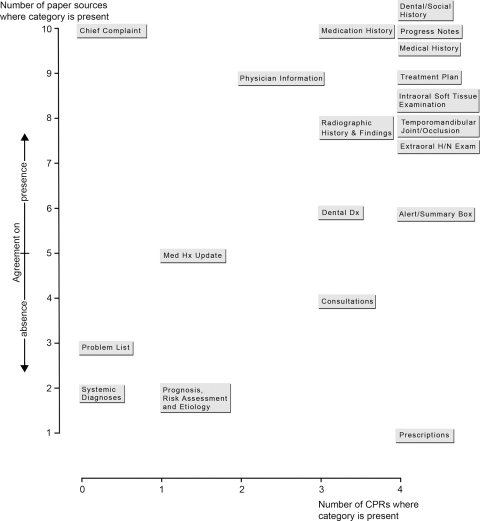

Comparison of Paper-based and Computer-based Record Formats

▶ compares the representation of the BDR categories in paper records to that in computer-based records. The 12 categories in the top right quadrant are observed frequently in both record formats, and include key items such as the “Medical history,” the “Treatment plan,” and “Progress notes.” “Consultations” are found commonly in computer-based records, but not on paper. (“Prescriptions” as an outlier in this category have already been discussed above.) The “Chief complaint” is the only category that is found in all paper records, but not in computer-based records. The lower left quadrant shows categories that appear rarely in both paper-based and computer-based formats, which include “Medical history update,” “Problem list,” “Systemic diagnoses,” and “Prognosis, risk assessment, and etiology.”

Figure 4.

Frequency of baseline dental record categories among 10 paper record formats and four computer-based patient record formats.

The high degree of agreement apparent in categories is not reflected to the same extent when comparing the data fields within those categories. Note that a category was marked as present if at least one corresponding data field was contained in the specific record format—an admittedly low threshold. As ▶ shows, the number of data fields within each category varies significantly among individual record formats. For instance, sample ranges for the number of data fields are: “Medication history,” 1–6 (paper), 0–3 (computer); “Medical history,” 25–70 (paper), 19–70 (computer); “Extraoral head and neck exam,” 0–6 (paper), 1–2 (computer); and “Progress notes,” 2–6 (paper) and 4–5 (computer).

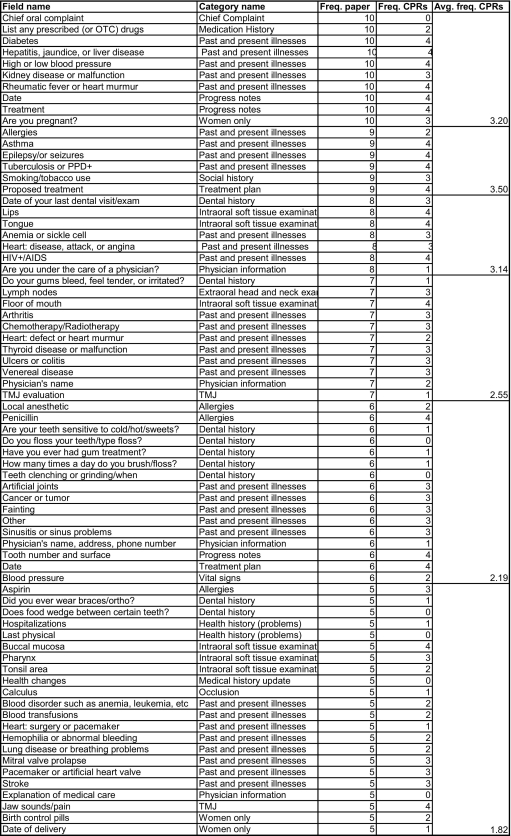

In total, 72 of the 363 BDR fields occur in five or more paper records (▶). The 10 most common fields include items such as “Chief oral complaint,” “List any prescribed (or over-the-counter) drugs,” several relevant medical conditions, and “Date” and “Treatment” in the progress notes. The 13 fields that occur either eight or nine times in paper records include several medical conditions, “Smoking/tobacco use,” “Proposed treatment,” the date of the last dental visit, soft tissue findings for the lips and tongue, and whether the patient is under the care of a physician. The remaining 49 data fields, which occur fewer than eight times, are mainly contained in the categories “Medical history” and updates to it, “Dental history,” “Temporomandibular joint/occlusion,” “Intraoral soft tissue examination,” and “Physician information.” ▶ shows an almost linear relationship between the frequency of data fields in paper records and their frequency in computer-based records; fields that occur less frequently in paper records also occur less frequently in computer-based records. Nevertheless, there are clear disagreements between the paper and the computer world. Fields found in the majority of paper records are sometimes found rarely or not at all in paper records, and vice versa.

Table 4.

Table 4 The 72 Data Fields That Were Contained in Five or More Paper Records, Their Category/Subcategory, the Frequency of Occurrence in Paper/Computer Records, and the Average Frequency of Occurrence in Computer Records.

|

Data are sorted by their frequency in paper records, the category/subcategory, and data field name.

Feedback from Vendors on Study Results

All three vendors reviewed and commented on the results of this study. The only change to the results was that the periodontal finding “Recession” was changed to “Chartable” in Dentrix and EagleSoft. In addition, the vendors made the following comments.

One vendor argued that any of the clinical information we found missing could be entered as text in progress notes. Because all four CPRs offer free-text progress note fields, this assertion is true for all systems. Dental practitioners use free text fields, whether on paper or computer, to record a variety of data. Nevertheless, there are two main problems with the vendor’s suggestion. First, the progress notes are not the appropriate place for all types of data that cannot otherwise be accommodated by the system. For example, although the numerical reading of a caries test for a single tooth can be recorded in the progress notes, a much better place would be the hard tissue chart, where it can be directly associated with the tooth and related data. Second, as the study of structured versus unstructured data in medical informatics has shown, embedding structured data in free-text progress notes reduces the efficiency and effectiveness with which those data can be queried and retrieved.

Several vendors commented on the capabilities of their product to chart hard tissue and periodontal conditions, as well as procedures, in places other than the actual chart itself. In reviewing the hard tissue and periodontal charts, we focused only on each CPR’s ability to record information as either text, numbers, or a symbol in each chart. Several applications were able to chart any of the information items using diagnoses or procedure codes; however, those records were displayed in tables below the clinical chart, and thus did not meet our condition that they had to be visible in the chart itself. One vendor emphasized the fact that the program provided custom draw types for charting, which allowed the user to create any type of symbol. Because we used all programs in their default mode after installation, this capability did not influence the result of our study.

Some comparison of the BDR and CPRs evidenced representational mismatches. For instance, on several paper forms the “Medical history update” is separate from the “Medical history” and typically comprises a dedicated set of fields to allow the practitioner to record changes in the patient’s health. Several CPRs lacked the “Medical history update” category, but were able to store multiple copies of the “Medical history.” Thus, updating the medical history was possible in CPRs, but in a manner different from paper records.

Discussion

This qualitative study resulted in several important findings with implications both for the content of paper-based dental records as well as the representation of that content in dental CPRs. The 10 paper records in this study contained a total of 363 clinical data fields. Nevertheless, the BDR source records as a group, as well as the CPRs, contained on average only about 60% of those fields. Only 20% of all BDR fields were contained in five or more paper records. Our first conclusion is that although dental records contain a relatively large number of fields, there is little agreement on what those fields should be.

The BDR should not be construed as a gold standard for dental record keeping; thus, a discussion of which record formats perform better or worse in representing their content should be interpreted cautiously. Both paper-based and computer-based formats contain about 14 of the 20 BDR information categories, with dental schools’ records covering slightly more categories 18 than dentists’ 12 and vendors’ records. 14 Dental schools also use more comprehensive medical history forms, which echoes Minden’s findings. 21

There was a relatively high level of agreement on categories among paper-based and computer-based record formats, with some notable differences (such as for “Chief complaint,” “Medical history update,” “Problem list,” “Systemic diagnoses,” and “Prognosis, risk assessment, and etiology”). Nevertheless, that level of agreement did not extend to data fields, as only 57% of the data fields occurring in five or more paper records were contained in more than two CPRs. Limitations in information representation in CPRs also were evident in charting hard tissue and periodontal findings, and procedures. The CPRs could only chart between 38% and 77% of the representative set of information items. It is thus evident that CPRs can place potentially significant constraints on a practitioner’s ability to store clinical information, despite vendors’ claims that free-text fields can accommodate any data clinicians want to record and that users can custom-configure a program to enhance its capability to represent data. It is currently unknown to what degree end users actually take advantage of these capabilities.

The paucity of records containing information categories and data fields typically associated with developing problem lists or making diagnoses adds another piece of evidence to the view that dentists typically do not record diagnoses. 27–30 The absence of dedicated fields reduces the likelihood that dentists routinely record this information. This situation, if verified through empirical studies, may present important structural and behavioral hurdles to more widespread recording of diagnoses in dentistry. 27,29

The comparatively more limited information coverage of clinical information by CPRs, combined with the disassociation of data fields that typically are grouped together in paper records, has important implications for the clinical usefulness and ease-of-use of dental CPRs. The evidence from our study suggests that dental CPRs require more intensive navigation and short-term memorization of patient information than paper records, a phenomenon also observed in medical CPRs. 31,32 Given other emerging evidence for significant design and usability problems in dental CPRs, 33 new approaches to user interface design for dental CPRs seem sorely needed.

This study has several important limitations. First, we drew on a purposive convenience sample of paper records, which may have biased and constrained the content of our BDR to some extent. Although additional record formats would have been easily obtainable, we were primarily constrained by the availability of personnel to conduct the record reviews. We attempted to balance this limitation by verifying the categories and data fields in the paper records through textbooks. Second, one may consider the 20 BDR categories as somewhat arbitrary, which is certainly true. Nevertheless, the categories were based on the way information was organized in most paper records, and thus will be intelligible to most dental clinicians. A last limitation was the subjective judgments we had to make in selecting the BDR data fields and mapping them to both paper-based and computer-based records. A related constraint was that not all data fields in the BDR had the same level of granularity. Nevertheless, data fields that encompassed other information within a category were relatively rare, and thus did not significantly affect our calculations.

This study motivates future work on a number of issues. The first one is to answer the question of what clinical information dental records must or should contain. As a result of this study, the ADA’s SCDI has approved the work item “NWI 1053: General dental electronic health record information model,” which will extend the existing ANSI/ADA 1000 Specification. Once developed, this specification can serve as a basis for the design of physical databases as well as presentation layers for future dental CPRs. A second question is how the storage medium affects the quality of clinical documentation. In one study, 34 physicians who used a CPR produced more complete documentation and documented more appropriate clinical decisions than those who used paper. We currently have few data on the documentation habits of dentists using paper records. 13,21,22 Portions of the BDR could serve as a framework for assessing the current information content of dental records, and the outcomes of such studies could inform multiple efforts, such as quality assurance, outcomes assessment, epidemiological studies, and practice-based research.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the assistance of the dentists, dental schools, and vendors who provided us with paper- and computer-based patient record formats. The authors thank the CPR vendors who reviewed this manuscript and provided us with feedback, specifically Danette Johnson (Dentrix), Bonnie Pugh (Kodak), and Dianna Borries (Patterson). The authors also thank Bambang Parmanto, Jeannie Yuhaniak, Thankam Thyvalikakath, and Miguel Humberto Torres-Urquidy for their input on this project and comments on the manuscript, as well as Michael Dziabiak for his assistance in preparing the final manuscript. Part of this manuscript was based on Dr. Hernandez’s masters thesis titled “Paper- and Computer-Based Representation of Clinical Documentation in Dentistry.”

Footnotes

Supported by National Library of Medicine award 5T15LM07059-17.

References

- 1.American Dental Association Survey Center 2000 Survey of current issues in dentistry: Dentists’ computer use. Chicago, IL: American Dental Association; 2001.

- 2.Schleyer TK, Thyvalikakath TP, Spallek H, Torres-Urquidy MH, Hernandez P, Yuhaniak J. Clinical computing in general dentistry J Am Med Inform Assoc 2006;13:344-352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burt CW, Hing E. Use of computerized clinical support systems in medical settings: United States, 2001–03 Adv Data 2005;353:1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brailer DJ, Terasawa EL. Use and adoption of computer-based patient records. Oakland, CA: California HealthCare Foundation; 2003.

- 5.Jha AK, Ferris TG, Donelan K, et al. How common are electronic health records in the united states?A summary of the evidence. Health Aff (Millwood) 2006. Oct 11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Campbell EM, Sittig DF, Ash JS, Guappone KP, Dykstra RH. Types of unintended consequences related to computerized provider order entry J Am Med Inform Assoc 2006;13:547-556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mikkelsen G, Aasly J. Concordance of information in parallel electronic and paper based patient records Int J Med Inform 2001;63:123-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stausberg J, Koch D, Ingenerf J, Betzler M. Comparing paper-based with electronic patient records: Lessons learned during a study on diagnosis and procedure codes J Am Med Inform Assoc 2003;10:470-477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Archbold RA, Laji K, Suliman A, Ranjadayalan K, Hemingway H, Timmis AD. Evaluation of a computer-generated discharge summary for patients with acute coronary syndromes Br J Gen Pract 1998;48:1163-1164. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spatz H, Engel J, Holzel D, Jauch KW. The surgical discharge summary: A lack of substantial clinical information may affect the postop treatment of rectal cancer patients Langenbecks Arch Surg 2001;386:350-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atkinson JC, Zeller GG, Shah C. Electronic patient records for dental school clinics: More than paperless systems J Dent Educ 2002;66:634-642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roukema J, Los RK, Bleeker SE, van Ginneken AM, van der Lei J, Moll HA. Paper versus computer: Feasibility of an electronic medical record in general pediatrics Pediatrics 2006;117:15-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minden NJ, Fast TB. Selection and use of dental records among general practitioners Gen Dent 1993;41:410-414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minden NJ, Fast TB. The patient’s health history form: How healthy is it? J Am Dent Assoc 1993;124:95-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ASTM Committee E31 E1384-02a Standard practice for content and structure of the electronic health record (EHR). West Conshohocken, PA: ASTM International; 2006.

- 16.Eaton KA. Standards in Dentistry. London, UK: Faculty of General Dental Practice (UK); 2006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.American Dental Association The Dental Patient Record: Structure and Function Guidelines. Chicago, IL: American Dental Association; 1987.

- 18.Hardin JF. Clark’s Clinical Dentistry. 4th ed.. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1998.

- 19.Jaroski-Graf J. Dental Charting: A Standard Approach. Albany, NY: Delmar; 2000.

- 20.Stefanac S, Nesbit S. Treatment Planning in Dentistry. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2001.

- 21.Morgan RG. Quality evaluation of clinical records of a group of general dental practitioners entering a quality assurance programme Br Dent J 2001;191:436-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osborn JB, Stoltenberg JL, Newell KJ, Osborn SC. Adequacy of dental records in clinical practice: A survey of dentists J Dent Hyg 2000;74:297-306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.ADA Standards Committee on Dental Informatics ANSI/ADA Specification No. 1000 for Standard Clinical Data Architecture for the Structure and Content of an Electronic Health Record. Chicago, IL: American Dental Association; 2001.

- 24.Young D, Budenz A. Hard tissue examinationIn: Daniel SJ, Harfst SA, editors. Mosby’s Dental Hygiene: Concepts, Cases, and Competencies. 2nd ed.. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2004. pp. 309-332.

- 25.Dietz ER. Dental Office Management. Albany, NY: Delmar; 1999.

- 26.American Dental Association CDT 4: Current Dental Terminology: Code on Dental Procedures and Nomenclature, Glossary of Dental Terms, ADA Dental Claim Form. 4th ed.. Chicago, IL: American Dental Association; 2002.

- 27.Phantumvanit P, Monteil RA, Walsh TF, et al. 4.2 Clinical records and global diagnostic codes Eur J Dent Educ 2002;6(Suppl 3):138-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leake JL, Main PA, Sabbah W. A system of diagnostic codes for dental health care J Public Health Dent 1999;59:162-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bader JD, Shugars DA. A case for diagnoses J Am Coll Dent 1997;64:44-46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Button PS, Doyle K, Karitis JW, Selhorst C. Automating clinical documentation in dentistry: case study of a clinical integration model J Healthc Inf Manag 1999;13:31-40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nygren E. From paper to computer screen: human information processing and interfaces to patient data AMIA WG6 Conference on Natural Language and Medical Concepts Representation. 1997. pp. 1-11Jacksonville, FL, January 1997.

- 32.Ash J, Berg M, Coiera E. Some unintended consequences of information technology in heath care: The nature of patient care information system-related errors J Am Med Inform Assoc 2004;11:104-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thyvalikakath TP, Schleyer TK, Monaco V. Heuristic evaluation of clinical functions in four practice management systems J Am Dent Assoc 2006;138:209-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang P, LaRosa M, Gorden S. Use of computer-based records, completeness of documentation, and appropriateness of documented clinical decisions J Am Med Inform Assoc 1999;6:245-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]