Abstract

Ionotropic glutamate (Glu) receptors in the central nervous system of animals are tetrameric ion channels that conduct cations across neuronal membranes upon binding Glu or another agonist. Plants possess homologous molecules encoded by GLR genes. Previous studies of Arabidopsis thaliana root cells showed that the amino acids alanine (Ala), asparagine (Asn), cysteine (Cys), Glu, glycine (Gly), and serine trigger transient Ca2+ influx and membrane depolarization by a mechanism that depends on the GLR3.3 gene. This study of hypocotyl cells demonstrates that these six effective amino acids are not equivalent agonists. Instead, they grouped into hierarchical classes based on their ability to desensitize the response mechanism. Sequential treatment with two different amino acids separated by a washout phase demonstrated that Glu desensitized the depolarization mechanism to Gly, but Gly did not desensitize the mechanism to Glu. All 36 possible pairs of agonists were tested to characterize the desensitization hierarchy. The results could be explained by a model in which one class of channels contained a subunit that was activated and therefore desensitized only by Glu, while a second class could be activated and desensitized by Ala, Cys, Glu, or Gly. A third class could be activated and desensitized by any of the six effective amino acids. Analysis of knockout mutants indicated that GLR3.3 was a required component of all three classes of channels, while the related GLR3.4 molecule specifically affected only two of the classes. The resulting model is an important step toward understanding the biological roles of these enigmatic ion channels.

One surprise to emerge from the first comprehensive inventory of a plant genome (Arabidopsis Genome Initiative, 2000) was the identification of a family of 20 genes unequivocally homologous to mammalian ionotropic Glu receptors (Lam et al., 1998; Lacombe et al., 2001). Such receptors function as ligand-gated ion channels in the mechanism that transmits signals between cells in the central nervous system (Madden, 2002; Mayer, 2005). At the junction between two neurons, or synapse, the presynaptic cell releases the neurotransmitter Glu, which binds to ionotropic Glu receptors located at the plasma membrane of the postsynaptic cell. Ionotropic Glu receptors are tetrameric ion channels. They respond to the binding of Glu by adopting a conformation that permits mixed cation flow into the postsynaptic cell, resulting in membrane depolarization (Madden, 2002). The channels quickly shift to a nonconducting (desensitized) conformation, which can be exited after unbinding of the agonist (Sun et al., 2002). Removal of Glu from the extracellular space promotes agonist unbinding and therefore recovery of sensitivity.

Depending on the types of subunits constituting a particular Glu receptor channel, Ca2+ may accompany Na+ and K+ ions flowing into the postsynaptic cell (Dingledine et al., 1999). In these cases, a rise in intracellular Ca2+ accompanies the membrane depolarization. The rise in Ca2+ plays a role in regulating synaptic transmission efficiency, which underpins learning and other central nervous system processes (Ghosh and Greenberg, 1995). Misregulation of synaptic activities mediated by Glu receptors is associated with neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and Huntington's diseases (Olney et al., 1998; Schiffer, 2002; Barnes and Slevin, 2003).

Because the ionotropic Glu receptors are studied mostly in the context of central nervous system signaling, it was a surprise to find genes having all the hallmarks of common ancestry, and even common function, in the genomes of plants (Davenport, 2002). Using hindsight, evidence of their existence can be seen in early plant electrophysiological studies. Etherton and colleagues demonstrated that large, transient membrane depolarizations were triggered by some amino acids and that the response displayed desensitization (Etherton and Rubinstein, 1978; Novacky et al., 1978). Models based on electrogenic amino acid transport were constructed to explain the results (Kinraide and Etherton, 1980, 1982), but the possibility that plants possess amino acid-gated ion channels was not yet raised. After the GLR genes were discovered, the phenomenon of amino acid-triggered ionic events in plants cells was investigated with a different model in mind. A study of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) roots showed that membrane depolarization in response to Glu was accompanied by a large spike in intracellular Ca2+ (Dennison and Spalding, 2000). A subsequent reverse-genetic study linked GLR3.3, one of the 20 Arabidopsis GLR genes, to the membrane depolarization and the Glu-induced Ca2+ rise (Qi et al., 2006). Mutation of GLR3.3 severely impaired both the membrane depolarization and the Ca2+ rise triggered by Glu in the micromolar to millimolar concentration range (Qi et al., 2006). These results leave little room for doubt that the plant GLR molecules are components of ligand-gated ion channels that transiently conduct cations, including Ca2+, into plant cells.

Other work on the GLR gene family has indicated a variety of roles for members of the gene family in plant physiology. These roles include regulation of hypocotyl elongation (Lam et al., 1998; Dubos et al., 2003), sensing of mineral nutrient status (Kim et al., 2001), regulating carbon/nitrogen balance (Kang and Turano, 2003), resisting aluminum toxicity (Sivaguru et al., 2003) and cold (Meyerhoff et al., 2005), root meristem function (Li et al., 2006; Walch-Liu et al., 2006), as well as jasmonate-mediated defense mechanisms (Kang et al., 2006).

While some evidence indicates that plant Glu receptors function much like their animal homologs, other results point to important differences. Sequence similarity between the Arabidopsis GLRs and animal iGluRs is high in the transmembrane domains (Chiu et al., 1999, 2002), but the N termini of the Arabidopsis GLRs may have come from ancestral amino acid-binding G-protein-coupled receptors (Turano et al., 2001). Structure modeling indicates that the plant molecules may have an additional amino acid binding site not present in animal iGluRs (Acher and Bertrand, 2005). Perhaps related to these potentially atypical binding sites, Qi et al. (2006) found that six very different amino acids were capable of triggering membrane depolarization and a Ca2+ rise. The effective amino acids were Ala, Asn, Cys, Glu, Gly, and Ser. Even glutathione (a tripeptide consisting of Glu-Gly-Cys) triggered a full response. Responses to all six effective amino acids and glutathione were equally impaired by glr3.3 mutations (Qi et al., 2006). These results provided genetic evidence that a GLR molecule was mechanistically related to the ionic events triggered by an amino acid. More specifically, these results indicated that that GLR3.3 is a necessary subunit of channels that respond to all six amino acids and the tripeptide. A question raised by the surprisingly broad agonist profile is whether or not all six effective amino acids are equivalent and whether or not other GLR family members contribute to the breadth of the profile. For example, do heteromeric channels differing in subunit composition have different agonist profiles? This study takes advantage of the desensitization phenomenon and mutations in the GLR3.3 and GLR3.4 genes to address these questions.

RESULTS

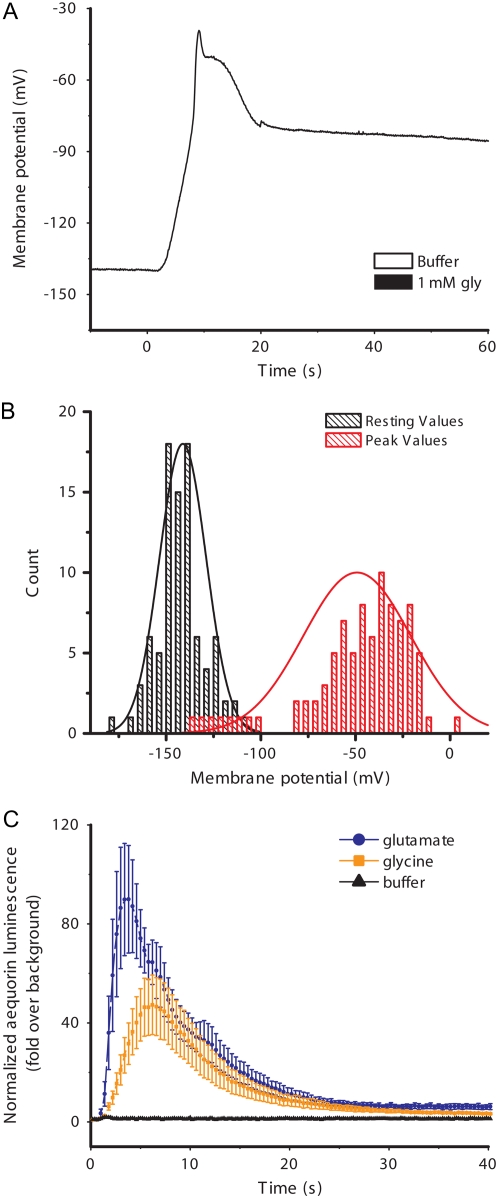

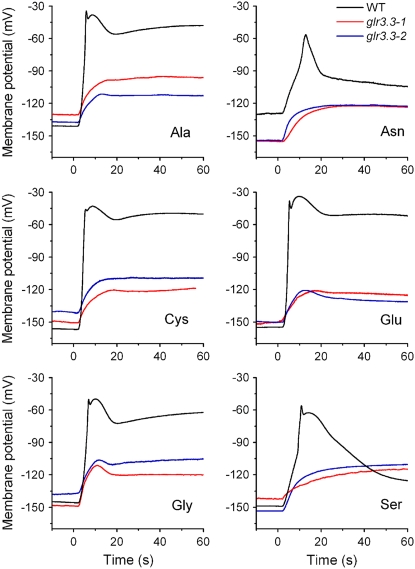

The first report of plant GLR genes presented pharmacological evidence that GLR channels may play a role in light signal transduction during de-etiolation (Lam et al., 1998). A second study provided more evidence of a connection between GLR function and light-controlled hypocotyl growth (Brenner et al., 2000). It had been previously established that light-induced membrane depolarizations in hypocotyls (Spalding and Cosgrove, 1989, 1992; Cho and Spalding, 1996; Parks et al., 1998) resembled amino acid-induced depolarizations in root cells (Dennison and Spalding, 2000; Qi et al., 2006). Taken together, these facts could be interpreted as evidence that GLRs mediate light-induced ionic events related to light signaling in hypocotyls. Therefore, hypocotyls were examined in this study to determine if previous findings in root cells were typical and to form a basis for understanding the role of GLRs in light signaling. An assumption at the outset was that different members of the 20-gene GLR family would be found to function in the hypocotyl and root if both organs were studied with similar techniques. Figure 1A shows that application of Gly to light-grown hypocotyls caused a large, transient membrane depolarization, similar to previously reported measurements in roots (Qi et al., 2006) and reminiscent of recordings made in mesophyll cells (Meyerhoff et al., 2005). Figure 1B summarizes 88 similar measurements of Gly-triggered transient depolarizations. The average initial resting potential was −141 mV and the response to Gly peaked at a value of −49 mV. The difference of 92 mV would be slightly greater if the eight individuals that did not respond beyond −100 mV for unknown reasons were disregarded. Rather than report the difference between initial and peak potential as a measure of the response, the less variable peak potential was used in subsequent quantifications of response magnitude. The Ca2+ rise triggered by Gly in isolated hypocotyl segments (Fig. 1C) was also similar to the Ca2+ response measured in whole seedlings (Dennison and Spalding, 2000; Dubos et al., 2003) and roots (Qi et al., 2006). Hypocotyl cells depolarized similarly to the same six amino acids as roots, namely, Ala, Asn, Cys, Glu, Gly, and Ser, and, as in roots, the response depended strongly on the GLR3.3 Glu receptor (Fig. 2). Therefore, the basic ionic response to amino acids in the light-grown hypocotyl is similar to that in the root.

Figure 1.

A, Wild-type hypocotyl response to Gly. Typical membrane depolarization induced by switching from buffer to 1 mm Gly. B, Distribution of resting potentials and peak potentials from Gly-treated hypocotyl cells. Resting potential values (black) are normally distributed with a mean and median of −141 mV. The peak membrane potentials reached following application of 1 mm Gly (red) are right-hand skewed (mean = −49 mV, median = −42 mV). C, Hypocotyl segments show similar Ca2+ transients as those of whole seedlings. Transgenic aequorin-expressing hypocotyl segments were used to monitor responses to addition of Glu (blue) or Gly (orange). Final concentration of each agonist was 1 mm. Each curve represents the mean of three trials of 10 hypocotyl segments each (with se) with the exception of the buffer control, which was performed only once. Raw luminescence data was divided by the average pretreatment luminescence value to normalize each trace, taking into account tissue variability and differences in coelenterazine uptake.

Figure 2.

Wild-type and glr3.3 depolarizations in response to the six potent amino acids. Two independent alleles of glr3.3 (glr3.3-1, red; glr3.3-2, blue) displayed significantly smaller depolarizations than wild type in response to all six potent amino acids tested. Shown here are typical recordings collected on the same days. Mean peak values are shown in Figure 6B.

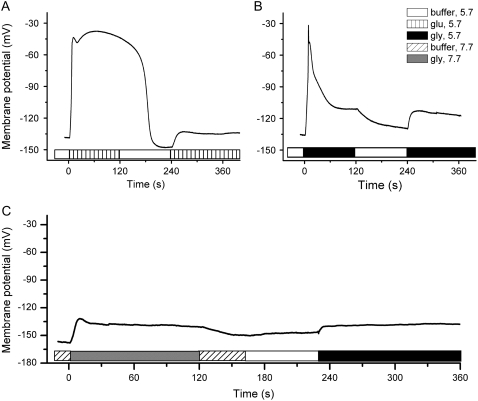

Depolarization-Independent Desensitization

Hypocotyl cells also underwent desensitization, a phenomenon much like in root cells. Figure 3A demonstrates that exposure to Glu desensitized a hypocotyl cell to a second application, even though the ligand had been removed by a 2-min washout period and the membrane had fully repolarized. Gly also desensitized the cell to a subsequent treatment of Gly (Fig. 3B). Unlike in root cells, an effective amino acid did not depolarize the cell much when the experiment was performed at pH 7.7 instead of pH 5.7 (Fig. 3C). In root cells, depolarizations recorded in pH 5.5 and pH 7.7 media were similar (Qi et al., 2006), but the higher pH blocked depolarizations in hypocotyl cells. Perhaps deprotonation of a residue near the mouth of the channel-types that predominate in hypocotyls affects ionic conductance of the open state. Whatever the mechanism by which external pH exerts this effect, it enabled tests of the role of the ionic responses in the desensitization mechanism. Gly presented at the nonpermissive pH 7.7 desensitized the cell to a second application of Gly presented at the permissive pH 5.7 (Fig. 3C). The pH change by itself did not cause desensitization (data not shown). Thus, desensitization occurred even in the absence of a large membrane depolarization.

Figure 3.

Desensitization of cells by prior agonist application. Exposure to 1 mm Glu (A) followed by a 2-min wash with buffer resulted in a substantially smaller depolarization by a second Glu treatment. B, Gly also renders the cell insensitive to a second Gly treatment. C, Gly elicited a substantially reduced depolarization when the pH of the extracellular medium was increased from 5.7 to 7.7, but the cell was still desensitized to a subsequent treatment with Gly at the permissive pH of 5.7.

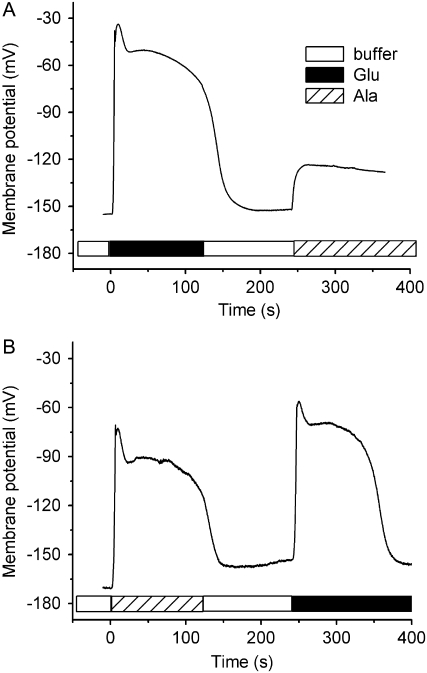

Asymmetric Desensitization

Experiments in which two different amino acid treatments were separated by a 2-min washout period produced evidence that not all effective amino acids are equivalent with respect to desensitization. Figure 4 shows an example of double agonist treatments (x→y). When Ala preceded Glu (Ala→Glu), two full depolarizations were observed. But when Glu preceded Ala (Glu→Ala), Ala was ineffective; the cell displayed a desensitized state. Thus, Glu desensitized the mechanism to Ala, but Ala did not desensitize the mechanism to Glu. Each of the 36 possible permutations of amino acid pairs was tested in at least three independent trials. Table I shows the average peak potential for each treatment. Values in the vicinity of −40 mV (a high peak potential) indicate that the second treatment produced a large response despite the first treatment. Values in the vicinity of −100 mV (a low peak potential) indicate that the first treatment desensitized the mechanism to the second treatment. Recordings typical of each unique treatment pair are shown in Supplemental Figure S1. The results were essentially binary; inspection of the shape of the response time course and the average peak potential showed that the mechanism was unambiguously either responsive or desensitized following the first treatment. Treating the data qualitatively permitted assignment of each amino acid to a rank in a hierarchical scheme. Glu desensitized the mechanism to each of the five other amino acids. Ala, Cys, and Gly formed the next level of desensitizers. Ser and Asn formed the lowest tier in the desensitization hierarchy.

Figure 4.

Serial amino acid treatments revealed asymmetric relationships between different agonists. A, Ala was ineffective following Glu application, but Glu was fully effective following Ala (B). Shown here are typical recordings of the Glu→Ala and Ala→Glu treatments. Mean peak values of second depolarizations are listed in Table I.

Table I.

Desensitization of wild-type hypocotyl cells by paired treatments

Shown in the table are peak membrane potential values reached in response to a second amino acid treatment (mV ± se). Initial treatments are indicated under “First Treatment” and second treatments are indicated under “Second Treatment.” Bold type indicates diminished responses to the second treatment, or desensitization.

| Second Treatment | First Treatment

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Ala | Asn | Cys | Glu | Gly | Ser | |

| Ala | −48 ± 3 | −117 ± 16 | −43 ± 6 | −69 ± 9 | −117 ± 15 | −98 ± 3 | −93 ± 8 |

| n = 45 | n = 3 | n = 3 | n = 5 | n = 3 | n = 3 | n = 12 | |

| Asn | −76 ± 4 | −108 ± 2 | −110 ± 4 | −99 ± 11 | −89 ± 16 | −101 ± 11 | −76 ± 11 |

| n = 36 | n = 2 | n = 3 | n = 2 | n = 3 | n = 3 | n = 5 | |

| Cys | −46 ± 4 | −78 ± 22 | −62 ± 19 | −96 ± 11 | −113 ± 4 | −95 ± 9 | −47 ± 5 |

| n = 35 | n = 3 | n = 4 | n = 3 | n = 3 | n = 3 | n = 3 | |

| Glu | −37 ± 3 | −47 ± 6 | −34 ± 3 | −52 ± 3 | −135 ± 5 | −42 ± 8 | −36 ± 4 |

| n = 50 | n = 3 | n = 3 | n = 3 | n = 3 | n = 11 | n = 3 | |

| Gly | −49 ± 3 | −87 ± 6 | −52 ± 12 | −102 ± 12 | −123 ± 5 | −108 ± 11 | −48 ± 2 |

| n = 88 | n = 4 | n = 3 | n = 3 | n = 4 | n = 6 | n = 3 | |

| Ser | −57 ± 3 | −125 ± 6 | −85 ± 6 | −101 ± 7 | −106 ± 15 | −79 ± 14 | −97 ± 3 |

| n = 49 | n = 3 | n = 3 | n = 3 | n = 3 | n = 3 | n = 3 | |

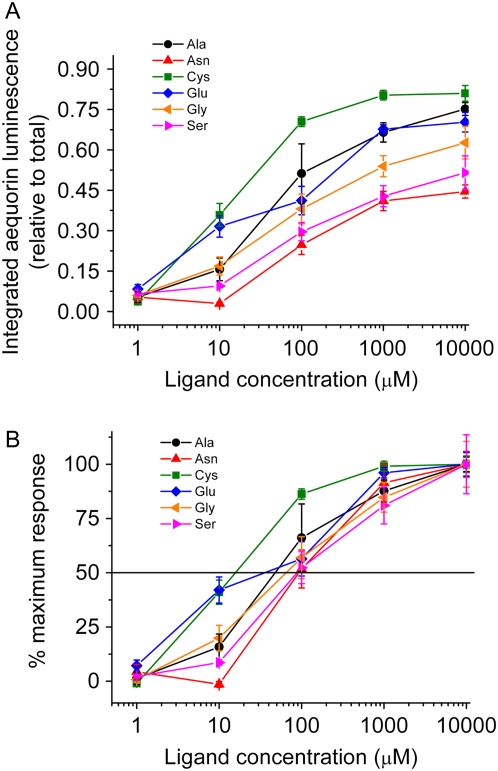

One possible explanation for the hierarchical behavior of the six different effective amino acids is that the top tier ligand, Glu, was more potent than the lower tier ligands. A dose-response analysis was performed to address the question of relative potency among the effective amino acids. The aequorin-reported Ca2+ response was chosen for this purpose because of its sensitivity, because the integral of the Ca2+ rise increased sigmoidally over three orders of magnitude of agonist concentration as expected for a simple ligand-/receptor-mediated process, and because in every respect it was shown to match depolarization measurements made with intracellular microelectrodes (Qi et al., 2006). The results, expressed in two different forms in Figure 5, showed that all six agonists were variously effective over the 10 to 1,000 μm range. The most potent of the six agonists was Cys and the least potent was either Ser or Asn. These data indicate that the desensitization hierarchy is probably not due to differences in agonist potency because Glu occupies the highest position in the desensitization hierarchy but is not significantly more potent than the others.

Figure 5.

Concentration dependence of amino acid-induced Ca2+ increases. Transgenic aequorin-expressing seedlings were used to compare the Ca2+ transients caused by the six potent amino acids. A, Integration of 25-s recordings following injection of agonists at specified concentrations. Each recording was first normalized by the total luminescence following discharge with 2 m CaCl2, 10% ethanol, then integrated. Ser and Asn gave the weakest increases in cytosolic calcium, while Cys triggered the largest increases. Treatment with 1 μm of any of the potent amino acids failed to elicit a detectable response above that of buffer injection. B, Data from A shown as a percentage of the maximal response by dividing each integration by the average response to 10,000 μm agonist and offset by subtracting the responses to buffer control injection. Approximate half-maximal concentration of the different agonists occurs around 100 μm, possibly lower for Cys.

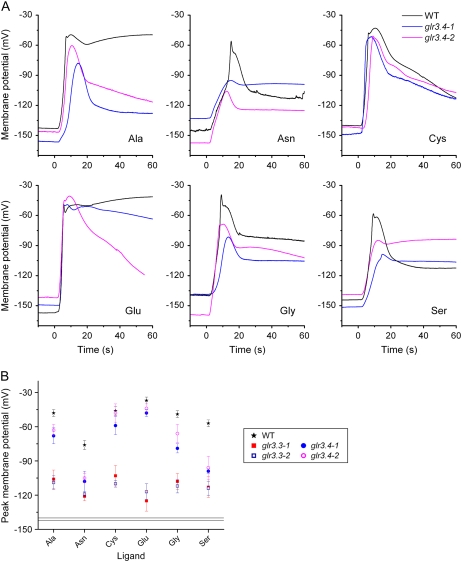

Different Contributions of GLR3.3 and GLR3.4

A systematic electrophysiological screen of many glr T-DNA insertion mutants identified GLR3.4 as a component of the amino acid response mechanism in hypocotyl cells. Two independent glr3.4 alleles were subjected to the same agonist profile screen that demonstrated a key role for GLR3.3 in the response to all six effective amino acids (Fig. 2). Typical traces of membrane potential changes recorded from wild type, glr3.4-1, and glr3.4-2 are shown in Figure 6A. Figure 6B shows the average peak potentials reached in each treatment for the two glr3.4 alleles, the wild type, and the two alleles of glr3.3. The data show that glr3.4 mutations impaired responses to Asn and Ser almost as severely as the glr3.3 mutations. However, glr3.4 depolarizations by Glu and Cys were very similar to those in the wild type. Statistical tests indicated that the glr3.4 response to Cys was significantly different from the wild type. The minor difference in the glr3.4 response to Glu was statistically significant in only one of the two alleles. Responses to Gly and Ala were impaired by glr3.4 mutations though not to the same extent as by glr3.3 mutations. Glu administered after a weak depolarization by Gly in glr3.4 triggered a normal, robust response (data not shown). Thus, GLR3.4 participates in responses to a subset of the six effective amino acids in the hypocotyl.

Figure 6.

A, Wild-type and glr3.4 depolarizations in response to the six potent amino acids. Two independent alleles of glr3.4 (glr3.4-1, blue; glr3.4-2, magenta) displayed significantly smaller depolarizations than wild type in response to some of the six potent amino acids tested. The greatest differences between wild type and mutants are seen in responses to Asn and Ser; smaller differences can be seen in Gly and Ala. Shown here are typical recordings collected on the same days. B, Peak membrane potential values for wild-type, glr3.3, and glr3.4 hypocotyls in response to the six potent amino acids (values in Supplemental Table S1). The mean resting potential ± se is indicated by a double line.

To determine whether or not the role of GLR3.4 was equivalent in other tissues, responses of glr3.4 root cells to Ser or Gly were also measured with intracellular microelectrodes. The Ser and Gly depolarizations in glr3.4 root cells were in all respects similar to those of the wild type (Supplemental Fig. S2). This is consistent with the expression of GLR3.4 being higher in the shoot than the root (Meyerhoff et al., 2005).

DISCUSSION

An important question raised by the previous work of Qi et al. (2006) was how six unrelated amino acids could each be an agonist of GLR3.3-dependent ion channels. Possible explanations included different GLR3.3-containing channel types, each specifically activated by a different amino acid, or, at the other extreme, one or more GLR3.3-containing channel types each activated by any of the six effective amino acids. The cross-desensitization data shown in Figure 4 and in Table I provide some critical information germane to the question. If each effective amino acid activated a specific channel type, then one ligand should not affect the sensitivity of the membrane to another. A Gly→Glu treatment should produce the same result as a Glu→Gly treatment. However, a Gly→Glu treatment elicited two full depolarizations, while a Glu→Gly treatment produced one full depolarization and a second response suppressed by desensitization. The first example is consistent with desensitization being due to a specific agonist-channel pair undergoing activity-based or homologous desensitization (Gainetdinov et al., 2004), but the second example is inconsistent with each agonist independently activating and desensitizing a specific channel.

The other scenario, in which all six effective amino acids are equivalent agonists of a channel, predicts that the first treatment should always desensitize the mechanism to the second treatment regardless of which amino acid was delivered first. The observed asymmetry in the cross-desensitization relationships appears to rule out this scenario. A caveat requiring investigation was the possibility that multiple agonists of a common channel differed by degree of potency in a manner that created a desensitization hierarchy. The dose response curves in Figure 5 weaken this possibility, as there was no clear correlation between potency and position in the hierarchy. Another related possibility is that during the 2-min washout period, agonists with a faster off-rate would unbind and leave the receptor sensitized, while agonists with a slower off-rate would remain bound to the receptor, leaving it desensitized. However, if a Ser→Glu treatment produced two full depolarizations because Ser unbinds during a 2-min wash, then Ser→Ser should also produce two full depolarizations. But, without exception, x→x treatments produced one full depolarization and a second desensitized response. Lastly, the observation that Glu was fully effective even in the continuous presence of Gly or Asn, i.e. Gly→Glu + Gly or Asn→Glu + Asn treatments (data not shown), argues against the six effective amino acids interchangeably activating the same channels. The above observations also argue against a form of desensitization in which activation induces a conformation that has a new high affinity for the agonist and is nonconducting. If “high affinity” desensitization (Giniatullin et al., 2005) was a major contributor to the hypocotyl cell behavior, then no second treatment should be effective. Collectively, the experimental observations do not support a model in which each of the six effective amino acids activates and desensitizes the same pool of receptor channels. The six effective amino acids do not function as equivalent agonists.

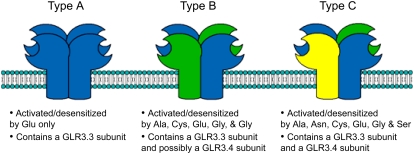

It is possible to accommodate almost all of the data obtained in this study with a model based on three types of qualitatively different, heteromeric GLR channel subtypes that undergo homologous desensitization. As shown in Figure 7, type A channels are activated and desensitized only by Glu. Type A channels contain at least one GLR3.3 subunit, without which the channel cannot function. This is based on the severe impairment of all responses by glr3.3 mutations. Type B channels are activated and desensitized by Ala, Cys, Gly, and Glu. Given the partial reduction in response to Ala, Cys, and Gly in glr3.4 mutants, type B channels are proposed to contain at least one GLR3.4 subunit in addition to at least one GLR3.3 subunit. Type C channels are proposed to be activated by all six effective ligands and necessarily to consist of GLR3.4 and GLR3.3 subunits. This proposal explains both the position of Asn and Ser at the bottom of the agonist hierarchy and the severe effects of glr3.4 mutations on the responses to these same two amino acids. Thus, an operationally defined channel type in the model is also genetically defined. According to this model, Glu desensitizes the hypocotyl cell to all other amino acids because all channel types are activated and desensitized by Glu, perhaps because the ubiquitous GLR3.3 is a Glu-sensitive subunit. Cys triggers a depolarization when delivered after Asn because type B channels would still be operable, etc. This model accounts for the desensitization patterns observed in the 36 unique double-agonist treatments with only one exception: Ser desensitized the mechanism to Ala, while the model predicts the opposite result. This result may be due to tight but nonactivating binding of Ser to the Ala site in type B and C channels. An observation that also appears to support the uniqueness of Asn and Ser action is that depolarizations induced by these two were narrower in shape, i.e. shorter duration, on average, than responses to the other amino acids even though the peak potentials attained were similar. This difference was quantified by recording the membrane potential 60 s after application of the agonist. As shown in Supplemental Figure S3, the more negative values for Asn and Ser indicated that the membrane had repolarized back toward its initial condition more so than for the other four amino acids, which on average showed a more prolonged depolarization.

Figure 7.

Proposed model of GLR channel subtypes in Arabidopsis hypocotyls based on wild-type and mutant data. Three types of multimeric ligand gated ion channels span the plasma membrane of light-grown hypocotyls: types A, B, and C. These channel subtypes are composed of functionally different subunits that confer amino acid-binding specificity. Loss of an essential subunit present in all three subtypes, GLR3.3, completely abolishes any channel function; likewise, activation by Glu results in activation and desensitization of all channels. Mutations in a nonessential subunit, GLR3.4, or treatment with a lesser agonist (Asn or Ser) results in a significant reduction of some channel activities (type C) with little effect on the remaining channels (types B and A).

A derivative of this model, equally consistent with the data, has each GLR subunit possessing two binding sites: an LAOBP domain (traditional Glu binding site) and an N-terminal LIVBP-binding domain for other amino acids (Felder et al., 1999; Bouché et al., 2003; Acher and Bertrand, 2005). In this case, all subunits would be able to bind Glu as well as another agonist, and type A channels would be an unnecessary feature of the model.

The desensitization phenomenon was exploited here to distinguish subtypes of receptor channels and to discern differences between the actions of the different effective amino acids. But the results also give some insight into the desensitization mechanism per se. Presentation of the agonist, not the subsequent ionic effects, is apparently the key event because desensitization occurred at a pH in which ion conduction was greatly suppressed. Thus, the desensitization phenomena reflect processes at or close to the receptor channel, such as ligand binding and conformational changes, rather than downstream consequences of the large ionic changes. Heterologous desensitization, in which activation of one receptor leads to desensitization of another type of receptor often by a signal transduction chain (Steele et al., 2002; Gainetdinov et al., 2004), therefore seems less probable. If heterologous desensitization contributes to the phenomena studied here, the mechanism coupling the different receptors appears not to depend on ion conduction. Instead, the simplest interpretation may be that binding of an effective amino acid by a GLR subunit causes the channel to pass from a closed state through a conducting state and into a desensitized state (Giniatullin et al., 2005). Recovery from the desensitized state may follow from agonist unbinding or from synthesis of new receptor channels as suggested by Meyerhoff et al. (2005).

The model presented here will guide the construction of higher order mutants that may produce informative phenotypes. The model may also guide heterologous expression studies and indicate which agonist(s) should be used to activate the expressed channels. For example, Meyerhoff et al. (2005) reported observing Glu-independent cation currents in GLR3.4-expressing Xenopus oocytes. Perhaps Glu was ineffective because it is not a good agonist of GLR3.4. Experiments using NMDA receptors serve as precedent for such a possibility. The NR3A or NR3B subunit, when coexpressed with the NR1 subunit, produced Gly-gated, Glu-insensitive cation channels (Chatterton et al., 2002). This example illustrates why elucidating the basic properties of agonist behavior and desensitization, and attributing them to particular genes, is an important objective in the overall effort to learn the biological function of this intriguing family of receptor channels.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Growth

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) seeds (Columbia ecotype) were surface sterilized with 75% ethanol and sown on 0.6% agar petri plates (3.5-cm diameter) containing 1 mm KCl, 1 mm CaCl2, 5 mm MES, pH 5.7, adjusted with Bis-Tris propane. The plates were maintained at 4°C in darkness for 48 to 72 h before transfer to a growth chamber with a 16-h-light/8-h-dark photoperiod and grown vertically for 4 d.

Membrane Potential Measurement

Measurements of membrane potential were made as previously described (Dennison and Spalding, 2000). Data acquisition was performed with a PCI-MIO-16XE-10 analog-to-digital converter (National Instruments) controlled by custom software written in the Labview computer language (National Instruments). The sample rate was 20 Hz. Perfusion of the recording chamber (7 mL min−1) was driven by a peristaltic pump (Dynamax RP-1, Rainin). The initial (control) perfusion solution was the same as the growth medium (minus the agar) and could be switched to one supplemented with an amino acid by electronic valves via the data acquisition software. The inflow tube was positioned as close as possible to the site of impalement to produce an abrupt (within approximately 2 s) exchange of solutions, which aided reproducibility of the resulting ionic responses. Experiments proceeded only if a stable membrane potential more negative than −120 mV was obtained in the control condition.

Measurement of Intracellular Ca2+ with Aequorin

Seeds of Arabidopsis plants expressing aequorin, described previously (Lewis et al., 1997), were sown and grown on agar as described above for 4 d before transfer to a darkroom in which the luminometer equipped with solution injectors (TD-20/20, Turner Designs) was located. For each trial, five seedlings were loaded into a luminometer cuvette containing 200 μL of the growth medium (minus agar) plus 5 μm coelenterazine (Molecular Probes) and allowed to soak overnight. Programmable, rapid delivery of agonist solutions into the cuvette was performed by the onboard injectors of the luminometer. A computer collected aequorin luminescence readings from the luminometer at 5 Hz. Following each trial, 200 μL of 2 m CaCl2 containing 10% (v/v) ethanol was injected to discharge the remaining aequorin. Integrating this large, luminescence transient produced a value that was used to normalize the experimental response, taking into account any variability in tissue content and coelenterazine uptake among trials. The first 25 s of each normalized recording, which included the entire response to agonist, were integrated, and the integrals for each trial were averaged (Fig. 5A). To express these same data relative to the maximum possible response for each agonist (Fig. 5B), each result was divided by the mean response to a saturating (10 mm) agonist treatment and then multiplied by 100. The small Ca2+ response to buffer-only treatment was also subtracted from each trial value.

Data shown in Figure 1C was obtained in a slightly different manner. Hypocotyls were excised from seedlings with a scalpel and then incubated in 10 μm coelenterazine overnight. Luminometer cuvettes were loaded with 10 hypocotyls per cuvette and then subjected to agonist treatment while recording luminescence as described above. Each resulting trace was divided by the average pretreatment luminescence to give a fold-increase in signal. Individual trial traces were averaged.

Mutant Genotyping

Seeds of plant lines containing a T-DNA insertion in the gene of interest were obtained from the Salk Institute (http://signal.salk.edu/cgi-bin/tdnaexpress). The lines used here were Salk_040458 (glr3.3-1, second exon insertion), Salk_066009 (glr3.3-2, first intron insertion), Salk_079842 (glr3.4-1, third exon insertion), and Salk_016904 (glr3.4-2, sixth exon insertion). To isolate homozygous mutant individuals, DNA was isolated from leaf samples using a 96-well-plate-based tissue grinder (GenoGrinder 2000; Spex CertiPrep). A left-border T-DNA primer (5′-TGGTTCACGTAGTGGGCCATCG-3′) was used in combination with gene-specific primers to test for the presence or absence of the T-DNA insertion alleles in segregating populations using PCR and agarose gel electrophoresis. The following are gene-specific primers used to confirm the genotype of the glr3.3 and glr3.4 mutant lines: SALK_040458, forward 5′-GAA ACC AAA AGT TGT GAA AAT CGG T-3′, reverse 5′-GAC ACA TTG TCT CTT AGG TGG GCC T-3′; SALK_066009, forward 5′-GAA ACC AAA AGT TGT GAA AAT CGG T-3′, reverse 5′-GAC ACA TTG TCT CTT AGG TGG GCC T-3′; SALK_079842, forward 5′-GTC CAT CCA GAG ACC TTG TAC TCT A-3′, reverse 5′-GCC ATG TTG TGA TTG TGA AGT CCC A-3′; SALK_016904, forward 5′-GTC CAT CCA GAG ACC TTG TAC TCT A-3′, reverse 5′-GCC ATG TTG TGA TTG TGA AGT CCC A-3′.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Example traces of each of the 36 possible paired ligand treatments.

Supplemental Figure S2. Depolarizations in root cells induced by Gly or Ser were not affected by glr3.4 mutations.

Supplemental Figure S3. Membrane potential achieved 60 s after the application of ligand is a measure of repolarization rate. The more negative the value of Vm60, the more quickly the membrane repolarized. Depolarizations induced by Asn and Ser were the briefest.

Supplemental Table S1. Values of peak membrane potential reached in response to the six effective amino acids in wild type, glr3.3, and glr3.4 mutants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the plant materials supplied by the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center; to Nathan D. Miller, Departments of Botany and Biomedical Engineering, University of Wisconsin, for constructing the data acquisition software and perfusion control apparatus; and to Cécile Ané, Departments of Statistics and Botany, for advice on statistical methods.

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (grant no. 04ER15527 to E.P.S.).

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantphysiol.org) is: Edgar P. Spalding (spalding@wisc.edu).

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

Open Access articles can be viewed online without a subscription.

References

- Acher FC, Bertrand HO (2005) Amino acid recognition by Venus flytrap domains is encoded in an 8-residue motif. Biopolymers 80 357–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arabidopsis Genome Initiative (2000) Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 408 796–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes GN, Slevin JT (2003) Ionotropic glutamate receptor biology: effect on synaptic connectivity and function in neurological disease. Curr Med Chem 10 2059–2072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouché N, Lacombe B, Fromm H (2003) GABA signaling: a conserved and ubiquitous mechanism. Trends Cell Biol 13 607–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner ED, Martinez-Barboza N, Clark AP, Liang QS, Stevenson DW, Coruzzi GM (2000) Arabidopsis mutants resistant to S(+)-β-methyl-α,β-diaminopropionic acid, a cycad-derived glutamate receptor agonist. Plant Physiol 124 1615–1624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterton JE, Awobuluyl M, Premkumar LS, Takahashi H, Talantova M, Shin Y, Cul J, Tu S, Sevarino KA, Nakanishi N, et al (2002) Excitatory glycine receptors containing the NR3 family of NMDA receptor subunits. Nature 415 793–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu J, DeSalle R, Lam HM, Meisel L, Coruzzi G (1999) Molecular evolution of glutamate receptors: a primitive signaling mechanism that existed before plants and animals diverged. Mol Biol Evol 16 826–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu JC, Brenner ED, DeSalle R, Nitabach MN, Holmes TC, Coruzzi GM (2002) Phylogenetic and expression analysis of the glutamate-receptor-like gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Biol Evol 19 1066–1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho MH, Spalding EP (1996) An Arabidopsis anion channel activated by blue light. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93 8134–8138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport R (2002) Glutamate receptors in plants. Ann Bot (Lond) 90 549–557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennison KL, Spalding EP (2000) Glutamate-gated calcium fluxes in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 124 1511–1514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingledine R, Borges K, Bowie D, Traynelis SF (1999) The glutamate receptor ion channels. Pharmacol Rev 51 7–61 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubos C, Huggins D, Grant GH, Knight MR, Campbell MM (2003) A role for glycine in the gating of plant NMDA-like receptors. Plant J 35 800–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etherton B, Rubinstein B (1978) Evidence for amino acid-H+ co-transport in oat coleoptiles. Plant Physiol 61 933–937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felder CB, Graul RC, Lee AY, Merkle HP, Sadee W (1999) The Venus flytrap of periplasmic binding proteins: an ancient protein module present in multiple drug receptors. AAPS PharmSci 1 E2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gainetdinov RR, Premont RT, Bohn LM, Lefkowitz RJ, Caron MG (2004) Desensitization of G protein-coupled receptors and neuronal functions. Annu Rev Neurosci 27 107–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A, Greenberg ME (1995) Calcium signaling in neurons: molecular mechanisms and cellular consequences. Science 268 239–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giniatullin R, Nistri A, Yakel JL (2005) Desensitization of nicotinic ACh receptors: shaping cholinergic signaling. Trends Neurosci 28 371–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J, Turano FJ (2003) The putative glutamate receptor 1.1 (AtGLR1.1) functions as a regulator of carbon and nitrogen metabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100 6872–6877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S, Kim HB, Lee H, Choi JY, Heu S, Oh CJ, Kwon SI, An CS (2006) Overexpression in Arabidopsis of a plasma membrane-targeting glutamate receptor from small radish increases glutamate-mediated Ca2+ influx and delays fungal infection. Mol Cells 21 418–427 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SA, Kwak JM, Jae SK, Wang MH, Nam HG (2001) Overexpression of the AtGluR2 gene encoding an Arabidopsis homolog of mammalian glutamate receptors impairs calcium utilization and sensitivity to ionic stress in transgenic plants. Plant Cell Physiol 42 74–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinraide TB, Etherton B (1980) Electrical evidence for different mechanisms of uptake for basic, neutral, and acidic amino acids in oat coleoptiles. Plant Physiol 65 1085–1089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinraide TB, Etherton B (1982) Energy coupling in H+-amino acid cotransport: ATP dependence of the spontaneous electrical repolarization of the cell membranes in oat coleoptiles. Plant Physiol 69 648–652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacombe B, Becker D, Hedrich R, DeSalle R, Hollman M, Kwak JM, Schroeder JI, Novère NL, Nam HG, Spalding EP, et al (2001) The identity of plant glutamate receptors. Science 292 1486–1487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam HM, Chiu J, Hsieh MH, Meisel L, Oliveira IC, Shin M, Coruzzi G (1998) Glutamate-receptor genes in plants. Nature 396 125–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis BD, Karlin-Neumann G, Davis RW, Spalding EP (1997) Ca2+-activated anion channels and membrane depolarizations induced by blue light and cold in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant Physiol 114 1327–1334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Zhu S, Song X, Shen Y, Chen H, Yu J, Yi K, Liu Y, Karplus VJ, Wu P, et al (2006) A rice glutamate receptor-like gene is critical for the division and survival of individual cells in the root apical meristem. Plant Cell 18 340–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden DR (2002) The structure and function of glutamate receptor ion channels. Nat Rev Neurosci 3 91–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer M (2005) Glutamate receptor ion channels. Curr Opin Neurobiol 15 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerhoff O, Müller K, Roelfsema MRG, Latz A, Lacombe B, Hedrich R, Dietrich P, Becker D (2005) AtGLR3.4, a glutamate receptor channel-like gene is sensitive to touch and cold. Planta 222 418–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novacky A, Fischer E, Ullricheberius CI, Lüttge U, Ullrich WR (1978) Membrane potential changes during transport of glycine as a neutral amino acid and nitrate in Lemna gibba G1. FEBS Lett 88 264–267 [Google Scholar]

- Olney JW, Wozniak DF, Farber NB (1998) Glutamate receptor dysfunction and Alzheimer's disease. Restor Neurol Neurosci 13 75–83 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks BM, Cho MH, Spalding EP (1998) Two genetically separable phases of growth inhibition induced by blue light in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant Physiol 118 609–615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Z, Stephens NR, Spalding EP (2006) Calcium entry mediated by GLR3.3, an Arabidopsis glutamate receptor with a broad agonist profile. Plant Physiol 142 963–971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffer HH (2002) Glutamate receptor genes: susceptibility factors in schizophrenia and depressive disorders? Mol Neurobiol 25 191–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivaguru M, Pike S, Gassmann W, Baskin TI (2003) Aluminum rapidly depolymerizes cortical microtubules and depolarizes plasma membrane: evidence that these responses are mediated by a glutamate receptor. Plant Cell Physiol 44 667–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spalding EP, Cosgrove DJ (1989) Large plasma-membrane depolarization precedes rapid blue-light-induced growth inhibition in cucumber. Planta 178 407–410 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spalding EP, Cosgrove DJ (1992) Mechanism of blue-light-induced plasma-membrane depolarization in etiolated cucumber hypocotyls. Planta 188 199–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele AD, Szabo I, Bednar P, Rogers TJ (2002) Interactions between opioid and chemokine receptors: heterologous desensitization. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 13 209–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Olson R, Horning M, Armstrong N, Mayer M, Gouaux E (2002) Mechanism of glutamate receptor desensitization. Nature 417 245–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turano FJ, Panta GR, Allard MW, van Berkum P (2001) The putative glutamate receptors from plants are related to two superfamilies of animal neurotransmitter receptors via distinct evolutionary mechanisms. Mol Biol Evol 18 1417–1420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walch-Liu P, Liu LH, Remans T, Tester M, Forde BG (2006) Evidence that L-glutamate can act as an exogenous signal to modulate root growth and branching in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol 47 1045–1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.