Abstract

Accumulated evidence suggests that the heteromeric assembly of Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 α subunits underlies the fast transient Kv current (Ito,f) in rodent ventricles. Recent studies, however, demonstrated that the targeted deletion of Kv4.2 results in the complete elimination of Ito,f in adult mouse ventricles, revealing an essential role for the Kv4.2 α subunit in the generation of mouse ventricular Ito,f channels. The present study was undertaken to investigate directly the functional role of Kv4.3 by examining the effects of the targeted disruption of the KCND3 (Kv4.3) locus. Mice lacking Kv4.3 (Kv4.3−/−) appear indistinguishable from wild type control animals, and no structural or functional abnormalities were evident in Kv4.3−/− hearts. Voltage-clamp recordings revealed that functional Ito,f channels are expressed in Kv4.3−/− ventricular myocytes, and that mean Ito,f densities are similar to those recorded from wild type cells. In addition, Ito,f properties (inactivation rates, voltage-dependences of inactivation and rates of recovery from inactivation) in Kv4.3−/− and wild type mouse ventricular myocytes were indistinguishable. Quantitative RT-PCR and Western blot analyses did not reveal any measurable changes in the expression of Kv4.2 or the Kv channel interacting protein (KChIP2) in Kv4.3−/−ventricles. Taken together, the results presented here suggest that, in contrast with Kv4.2, Kv4.3 is not required for the generation of functional mouse ventricular Ito,f channels.

Keywords: KCND3, Kv α-subunits, Kv channels, heteromeric Kv channels

1. Introduction

Voltage-gated K+ (Kv) channels control the heights and durations of action potentials in the myocardium and are primary determinants of action potential repolarization [1,2]. In most species, the fast transient Kv current (Ito,f) plays a pivotal role in the early phase of action potential repolarization [1–3]. The high density of Ito,f in rodent ventricles and atria dominates even the later phase of repolarization and underlies the characteristic short triangular shape of cardiac action potentials in these animals [1]. In addition, Ito,f density varies in different regions of the ventricle [4–6]. In adult mouse ventricles, for example, Ito,f expression is higher in the right ventricle (RV) than in the left ventricle (LV); within the LV, Ito,f density is higher in the apex than in the base, and across the LV wall, is higher in the epicardium than in the endocardium [6]. The variations in Ito,f density contribute to regional Kv current gradients and to the normal dispersion of repolarization in the ventricles [4–6].

Functional Kv channels reflect the assembly of four Kv pore-forming (α) subunits, and two α subunits of Kv4 subfamily, Kv4.2 and Kv4.3, have been identified as the primary determinants of cardiac Ito,f channels [1–3]. In addition, accumulated data suggest that the heteromeric assembly of Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 underlies functional Ito,f channels in rodent ventricles. Both Kv4.2 and Kv4.3, for example, are expressed at the message [7–9] and protein [6,10,11] levels in rodent ventricles. In addition, Kv4.2 expression varies in different regions of the ventricles in rodents, and these differences (in Kv4.2 expression) are correlated with regional differences in Ito,f densities [6,7,10,11]. Heterologous co-expression studies with wild type (WT) and mutant (dominant negative) Kv4 α subunits [12,13] demonstrated directly that Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 can associate to form heteromeric channels. Expression of these dominant negative mutants in vivo [13] or in isolated rodent ventricular myocytes in vitro [12] reduced or eliminated Ito,f, demonstrating directly that members of Kv4 subfamily underlie Ito,f channels. In addition, selective gene suppression using antisense oligodeoxynucleotides (AsODN) against Kv4.2 or Kv4.3 suggests that both Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 contribute to the generation of functional Ito,f channels in rodent ventricles [11,14]. It has also been reported that co-expression of Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 produces heteromeric Kv channels with properties that more closely resemble native rodent Ito,f channels than the homomeric channels produced on expression of Kv4.2 or Kv4.3 alone [11], suggesting that Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 preferentially form heteromeric Ito,f channels. In addition, immunoprecipitation experiments suggest that most of the Kv4.2 protein in adult mouse ventricles in vivo is associated with Kv4.3 [11].

Recently, however, it was shown that the targeted deletion of KCND2 (Kv4.2) in vivo in (Kv4.2−/−) mice results in the elimination of ventricular Ito,f [15], revealing a critical role for Kv4.2 in the generation of mouse ventricular Ito,f channels. These observations give rise to an intriguing next question, i.e., whether Kv4.3 is also necessary for the generation of functional (mouse ventricular) Ito,f channels. The experiments here were designed to address this question directly by examining the effects of the targeted disruption of the KCND3 locus (Kv4.3−/−) on mouse ventricular Ito,f densities and properties. Electrophysiological studies revealed that functional Ito,f channels are expressed in Kv4.3−/− mouse ventricular myocytes, and that mean Ito,f densities and properties in Kv4.3−/− and wild type myocytes are similar. These results suggest that, in contrast with Kv4.2, Kv4.3 is not required for the generation of functional Ito,f channels in adult mouse ventricles.

2. Materials and methods

Adult (7–16 week) C57BL6 mice were used in the experiments here. All animals were used in accord with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and all experimental protocols were approved by the Washington University Animal Studies Committee.

2.1. Kv4.3 targeted deletion

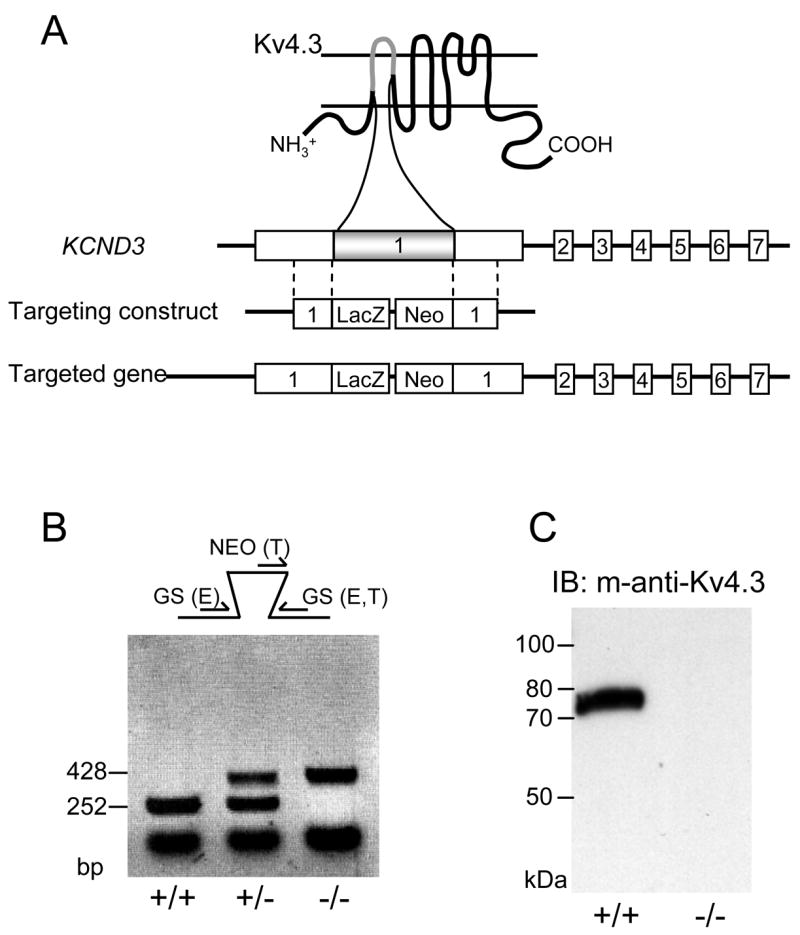

The KCND3 targeting construct was generated by replacement of a 147 bp fragment in exon 1 of the KCND3 locus with a cassette containing a lacZ reporter and a neomycin resistance gene (Figure 1A). This construct was designed to delete the Kv4.3 protein from the middle of the first transmembrane spanning domain (S1) to the middle of the second transmembrane spanning domain (S2), such that no full-length Kv4.3 protein is produced. PCR primers, designed to distinguish the endogenous and targeted alleles, confirmed the targeted disruption of the KCND3 locus (Figure 1B). In addition, the absence of the Kv4.3 protein in Kv4.3−/− animals was confirmed by Western blot analyses (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Targeted disruption of the KCND3 (Kv4.3) locus.

A, As illustrated, the KCND3 cording region contains 7 exons. The dark box shown in exon 1 represents a 147 bp region (amino acid residues 187 to 236) which was replaced with a lacZ-neomycin cassette. The replaced region corresponds to a part of the S1-S2 transmembrane domain. Homology regions are delineated with dashed lines. B, PCR analyses of KCND3 targeted mice. The schematic illustrates the PCR primer strategy to detect the endogenous (252 bp) or targeted (428 bp) KCND3 alleles. All three primers, 5′ gene-specific (GS), 5′ targeted (NEO) and 3′ GS, were used to allow simultaneous detection of the endogenous (E) and the targeted (T) alleles. Results from analyses of KCND3 wild type (WT) (+/+), heterozygous (+/−) and homozygous null (−/−) (Kv4.3−/−) mice are illustrated. C, Western blot analyses of Kv4.3 expression. For each lane, 1μg of brain protein lysate prepared from WT and Kv4.3−/− animals was loaded, and blots were probed with a mouse anti-Kv4.3 monoclonal antibody (Antibodies Inc.). A single band at ~75 kDa was detected in the WT mouse brain, while no band was detected in the Kv4.3−/− sample, consistent with the elimination of the Kv4.3 protein.

2.2. Electrocardiographic recordings

Surface electrocardiograms (ECG) were recorded from anesthetized (Avertin; 0.4 mg/g body weight) adult (8–14 week) WT and Kv4.3−/− animals. Needle electrodes (32G) were placed subcutaneously in the standard lead II equivalent position, and ECG signals were collected for 3 min using a Differential AC Amplifier Model 1700 (A-M systems) at 2.5 kHz sampling rate.

2.3. Electrophysiological recordings

In most experiments, myocytes were isolated from the apex of the LV of adult (8–14 week) WT and Kv4.3−/− (C57BL6) mice using previously described methods [6,16]. Some experiments were completed on myocytes isolated from the RV of WT and Kv4.3−/− animals. Briefly, each animal was anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of Avertin (0.4 mg/g body weight). After confirmation of deep anesthesia, the heart was excised, and perfused retrogradely through the aorta with collagenase (Worthington, type II) containing solution. Following digestion, the LV apex (and/or RV) was separated and dispersed by gentle trituration. Cell suspensions were filtered to remove large undissociated tissue fragments, resuspended in serum-free medium-199 (M-199; Sigma), plated on laminin-coated coverslips and maintained in a 95%air-5%CO2 incubator at 37°C until electrophysiological experiments were performed.

Whole-cell recordings were obtained at room temperature (22–24°C) within 24 hours of cell isolation using an Axopatch-1D amplifier (Axon Instruments) interfaced to a Digidata 1322A A/D converter (Axon Instruments). Voltage- and current-clamp paradigms were controlled by pClamp 9 software (Axon Instruments). Data were acquired at 10 or 100 kHz, and current signals were filtered on-line at 5 kHz prior to digitization and storage. Recording pipettes contained (in mM): KCl 135, EGTA 10, HEPES 10 and Glucose 5 (pH 7.2; 295–310 mOsm). Pipette resistances were 1.8–2.8 MΩ when filled with the recording solution. For voltage-clamp recordings, the bath solution contained (in mM): NaCl 136, KCl 4, MgCl2 2, CaCl2 1, CoCl2 5, Tetrodotoxin 0.02, HEPES 10 and Glucose 10 (pH 7.4; 295–300 mOsm). For current-clamp recordings, the Tetrodotoxin and CoCl2 were omitted from the bath solution.

After establishing the whole-cell configuration, ±10 mV steps from a holding potential (HP) of −70 mV were applied to allow measurements of whole-cell membrane capacitances and input resistances. Whole-cell membrane capacitances and series resistances were routinely compensated (≥85%) electronically. Only data obtained from cells with input resistances ≥250 MΩ were analyzed. Leak currents were always <100 pA, and were not corrected. Kv currents were evoked by 4.5 s depolarizing voltage steps to potentials between −40 and +40 mV from a HP of −70 mV; voltage steps were presented in 10 mV increments at 15 s intervals. Inwardlyrectifying K+ currents (IK1) were evoked in response to 4.5 s hyperpolarizing voltage steps to −120 mV from a HP of −70 mV. To determine the voltage dependence of steady-state inactivation of the Kv currents, a two pulse protocol was used. From a HP of −70 mV, 4 s conditioning prepulses to various potentials between −90 to 0 mV (in 10 mV increments) were presented, each followed by a 4 s test pulse to +30 mV. To determine the time course of recovery (from steady-state inactivation) of the Kv currents, a three pulse protocol was used. From a HP of −70 mV, cells were first depolarized to +30 mV for 4 s (conditioning pulse), subsequently hyperpolarized to −70 mV for various recovery times ranging from 10 ms to 10 s, and finally depolarized to +30 mV (test pulse) to assess the extent of recovery. Action potentials were evoked by brief (1 ms) suprathreshold (2×threshold) current injections at a frequency of 1 Hz.

2.4. RNA preparation

Adult (7–9 week) WT (n = 6) and Kv4.3−/− (n = 6) animals were sacrificed by cervical dislocation after halothane anesthesia, and the hearts were rapidly removed. LV were dissected and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for subsequent RNA isolation. After homogenization, total RNA was isolated using the TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen), and DNase treated with the RNeasy Fibrous Tissue Mini Kit (Qiagen). The concentration of total RNA in each sample was measured spectrophotometrically using a NanoDrop ND-1000 (NanoDrop Technologies). The quality of total RNA was assessed using gel electrophoresis. In addition, genomic DNA contamination was assessed by PCR amplification of total RNA samples without prior cDNA synthesis; no genomic DNA was detected.

2.5. Quantitative Real Time RT-PCR Analysis

First strand cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg of total RNA using the High-Capacity cDNA Archive Kit (Applied Biosystems). The expression levels of genes encoding Kv4.2, KChIP2, Kvβ1 and Kv1.5 were determined by quantitative real time RT-PCR using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). PCR reactions were performed on 10 ng of cDNA using sequence specific primer pairs (Table 1) and the ABI PRISM 7900HT Sequence Detection System. The cycling conditions included a hot start at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. All primer pairs were tested using mouse cDNA as the template, and templates giving 90–100% efficiency were chosen. In all cases, a single amplicon of the appropriate melting temperature or size was detected using the dissociation curve or gel electrophoresis. Data were collected with instrument spectral compensations using the Applied Biosystems SDS 2.2.2 software and analyzed using the comparative threshold cycle (CT) relative quantification method [17]. The Hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferese gene (HPRT) was used as an endogenous control to normalize the data [18]. Individual sample measurements (n = 6) were averaged and 2−ΔCT values for each gene, corresponding to the relative expression level of that gene compared with HPRT [9], were calculated and are reported here. CT values were <32. Negative control experiments using RNA samples incubated without reverse transcriptase during cDNA synthesis showed no amplification.

Table 1.

Primer pairs used for SYBR Green quantitative real time PCR

| Target gene | Primer sequence |

|---|---|

| KCND2 (Kv4.2) | 5′-GCCGCAGCACCTAGTCGTT

5′-CACCACGTCGATGATACTCATGA |

| KCNIP2 (KChIP2) | 5′-GGCTGTATCACGAAGGAGGAA

5′-CCGTCCTTGTTTCTGTCCATC |

| KCNAB1 (Kvβ1) | 5′-AAATACCCAGAAAGGCAAGTGT

5′-ATCTAGCATGTGCCGAGGAA |

| KCNA5 (Kv1.5) | 5′-CCTGCGAAGGTCTCTGTATGC

5′-TGCCTCGATCTCTCTTTACAAATCT |

| HPRT | 5′-TGAATCACGTTTGTGTCATTAGTGA

5′-TTCAACTTGCGCTCATCTTAGG |

2.6. Western blot analysis

Using previously described methods [6,11], Western blots were performed on total protein lysates prepared from the LV and RV of adult (8–16 week) WT (n = 4) and Kv4.3−/− (n = 4) mice. Equal amounts of protein (30 μg) were resolved by electrophoresis on 7.5% (Kv4.2) or 12% (KChIP2) SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to PVDF membranes. After blocking with 5% nonfat milk, the membranes were probed with a rabbit anti-Kv4.2 polyclonal (Chemicon) or mouse anti-KChIP2 monoclonal (Antibodies Inc.) antibody. These antibodies have been tested previously for specificity and cross-reactivity [6,11], and demonstrated to be (Kv4.2/KChIP2) subunit specific. To compare protein expression levels and to ensure equal loading of protein samples from different animals, Western blots were also completed to examine expression of an endogenous control, the Transferrin receptor [18], using a monoclonal mouse anti-Transferrin receptor antibody (Zymed). Following washing, the membranes were incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibody (PIERCE). After incubated with enhanced chemiluminescence (Super Signal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate, PIERCE), membranes were exposed to x-ray film (Kodak). Films were scanned using a GS-710 Imaging Densitometer (BIO-RAD), and densitometric analyses of specific protein bands were performed with the Quantity One software (BIO-RAD).

2.7. Data analysis

Electrophysiological data were compiled and analyzed using Clampfit 9 (Axon Instruments) and Excel (Microsoft). Whole-cell membrane capacitances were calculated by integrating the area under the capacitive transients. Peak currents were defined as the difference between the maximal Kv current amplitudes and the zero current level. The amplitudes of Ito,f, IK,slow and the steady-state K+ current (Iss), and the time constants of decay (τdecay) of Ito,f and IK,slow in individual ventricular myocytes, were determined from double exponential fits to the decay phases of the total Kv currents, as described previously [6,15,16]. IK1 amplitudes at −120 mV were measured at the peak of the inward currents. For each cell, current amplitudes werenormalized to the whole-cell membrane capacitance, and current densities (pA/pF) are reported. For analysis of the voltage-dependence of steady-state inactivation of Ito,f, current amplitudes (I) evoked during the +30 mV test depolarization following each conditioning prepulse were determined, and these amplitudes were then normalized to the maximal current amplitude (Imax) determined in the same cell. Normalized amplitudes (I/Imax) were plotted as a function of the conditioning prepulse potential, and fitted to the following Boltzman equation:

where V is the conditioning prepulse potential, V½ is the voltage of half maximal inactivation and k is the slope factor. For analysis of the time course of recovery (from steady-state inactivation) of Ito,f, current amplitudes evoked during each test depolarization were measured and normalized to the maximal current amplitude determined during the conditioning depolarization in the same cell. Normalized recovery data were then plotted against the recovery time and fitted with exponential functions.

For analysis of ECG recordings, the PR interval was determined from the onset of the P wave to the onset of the QRS complex. The QRS duration was determined from the onset of the QRS complex (the Q wave or the R wave) to the inflection in the upstroke of the S wave. The QT interval was measured from the onset of the ORS complex to the end of the T wave (defined as the intersection with the isoelectric point). The heart rate corrected QT interval, QTc, was calculated using the formula QTc = QT/(RR/100)1/2, as previously described [19].

All data are presented as means ± SEM. Statistical differences between groups of cells (animals) were examined using the Student’s t test. Two tailed probability (p) values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Phenotypic consequences of the targeted disruption of KCND3 (Kv4.3)

Kv4.3−/− mice are viable and fertile and, on gross examination, are indistinguishable from WT mice. Body and heart weights, measured in adult (8–16 week) WT and Kv4.3−/− mice prior to cell isolations, for example, were similar. Mean ± SEM body weights in WT and Kv4.3−/−animals were 23.6 ± 1.1 g (n = 16) and 21.5 ± 0.9 g (n = 12), respectively; mean ± SEM heart weights in WT and Kv4.3−/− animals were 224 ± 9 mg (n = 16) and 199 ± 14 mg (n = 12), respectively. There was also no significant difference in heart to body weight ratios in WT (9.7 ± 0.4 mg/g; n = 16) and Kv4.3−/− (9.3 ± 0.4 mg/g; n = 12) mice. Left ventricular myocyte size, calculated from analyses of whole cell membrane capacitances, were also similar in WT and Kv4.3−/− cells with mean ± SEM values of 146 ± 3 (n = 81) and 155 ± 5 (n = 60), respectively.

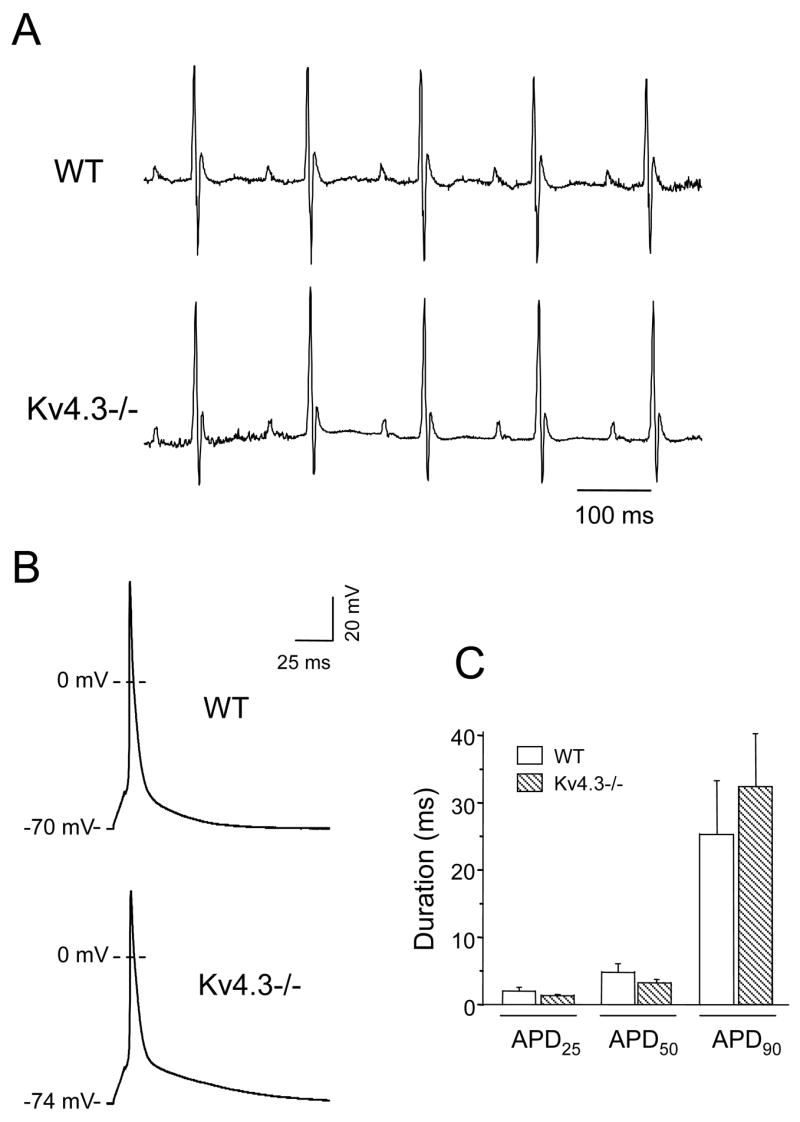

Analyses of ECG recordings from anesthetized mice did not reveal any morphological differences in P waves or QRS complexes in WT and Kv4.3−/− animals (Figure 2A). In addition, there were no significant differences in PR, QRS or QT intervals in WT and Kv4.3−/− mice. Mean ± SEM RR intervals were also similar in WT (135 ± 5 ms; n = 12) and Kv4.3−/− (143 ± 6 ms; n = 10) animals, although RR intervals in both groups were longer than those measured in conscious animals [15]. Consistent with the similarities in QT and RR intervals, heart rate corrected QT, QTc, intervals in WT and Kv4.3−/− mice, were not significantly different with mean ± SEM values of 49 ± 1 ms (n = 12) and 48 ± 1 ms (n = 10), respectively.

Figure 2. Electrophysiological characterization of KCND3−/− mice.

Representative surface ECG recordings (A) obtained from WT, and Kv4.3−/− mice and action potential waveforms (B) recorded from left ventricular (LV) apex myocytes isolated from WT and Kv4.3−/− mice are shown. Action potentials were evoked by a brief (1 ms) suprathreshold (2×threshold) current injections at a frequency of 1 Hz. C, Mean ± SEM action potential durations (APD) measured at 25% (APD25), 50% (APD50) or 90% (APD90) repolarization in WT and Kv4.3−/− LV apex myocytes, are displayed.

To determine the cellular consequence of the elimination of Kv4.3, action potential recordings were obtained from Kv4.3−/− cells isolated from the apex of the LV [6,15,16]. As shown in Figure 2B, action potential waveforms in WT and Kv4.3−/− LV apex cells were indistinguishable. There were no significant differences in action potential amplitudes or in action potential durations measured at 25%, 50% or 90% repolarization in Kv4.3−/− (n = 10) and WT (n = 7) LV apex myocytes (Figure 2C).

3.2.1. Functional Ito,f channels are expressed in Kv4.3−/− mouse ventricular myocytes

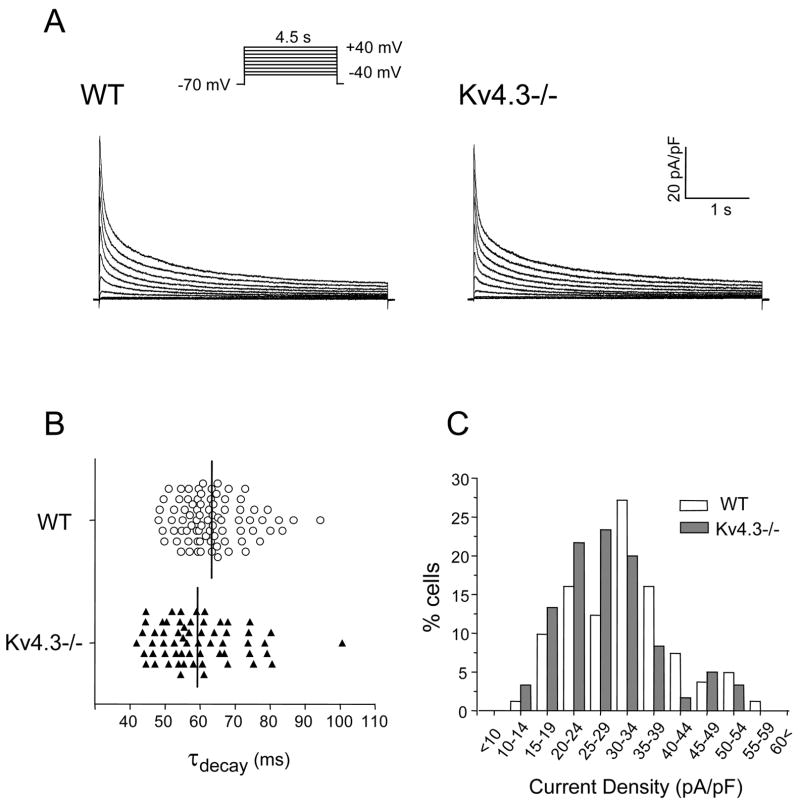

To examine the effects of the targeted gene deletion of Kv4.3 on Ito,f channel expression and properties, whole-cell patch clamp recordings were obtained from isolated adult WT and Kv4.3−/− mouse LV apex myocytes. As illustrated in Figure 3A, the waveforms of the Kv currents in Kv4.3−/− LV apex myocytes were indistinguishable from those in WT LV apex cells (Figure 3A). In addition, the mean ± SEM peak Kv current densities (at +40 mV) in Kv4.3−/−(56.5 ± 1.8 pA/pF; n = 60) and WT (58.4 ± 1.5 pA/pF; n = 81) LV apex myocytes were not significantly different (Table 2).

Figure 3. Kv current waveforms in Kv4.3−/− and WT LV myocytes.

A, Representative whole-cell voltage-gated outward K+ (Kv) currents recorded from WT and Kv4.3−/− LV apex myocytes. Currents were evoked during 4.5 s depolarizing voltage steps to potentials between −40 and +40 mV (10 mV increments) from a holding potential of −70 mV. The protocol is illustrated above the current records. B, Distribution of decay time constants (τdecay) of Ito,f in WT (n= 81) and Kv4.3−/− (n = 60) LV apex myocytes; black bars represent the mean values. C, Frequency histogram of Ito,f densities in WT (n = 81) and Kv4.3−/− (n = 60) ventricular myocytes.

Table 2.

Analyses of Kv currents in WT and Kv4.3−/− LV apex myocytes1

| Ipeak |

Ito,f |

IK,slow |

Iss |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Density (pA/pF) | Density (pA/pF) | τdecay (ms) | Density (pA/pF) | τdecay (ms) | Density (pA/pF) | |

| WT | 81 | 58.4 ± 1.5 | 31.7 ± 1.1 | 63 ± 1 | 21.0 ± 0.7 | 1162 ± 13 | 5.5 ± 0.1 |

| Kv4.3−/− | 60 | 56.5 ± 1.8 | 28.3 ± 1.2 | 59 ± 2 | 21.9 ± 0.8 | 1197 ± 21 | 5.8 ± 0.2 |

Current densities and decay time constants (τdecay) were determined from analyses of records obtained on depolarizations to +40 mV evoked from a holding potential of −70 mV. All values are means ± SEM; n = number of cells.

It has been demonstrated previously that the decay phases of the total Kv currents in mouse LV myocytes are best described by the sum of two inactivating components and a steady-state component [6,15,16]. The fast inactivating current, Ito,f, and the slow inactivating current, IK,slow, are characterized by decay time constants (τdecay) that differ by more than ten fold, and the steady-state current, Iss, does not appear to inactivate [6,15,16]. In initial experiments aimed at quantifying Ito,f (IK,slow and Iss) expression in Kv4.3−/− LV apex cells, therefore, the decay phases of the Kv currents were fitted with the sum of two exponentials and the amplitudes and τdecay values of the individual Kv components were determined. These analyses revealed that the Kv currents in Kv4.3−/− cells were also well described by the sum of two exponential components. As expected from the similarities in the Kv current waveforms, these analyses revealed the presence of a fast inactivating component in Kv4.3−/− LV apex myocytes similar to Ito,f in WT LV apex cells. As shown in Figure 3B, τdecay values for the fast inactivating component in Kv4.3−/− LV apex myocytes were distributed over a range similar to those of WT Ito,f. The mean ± SEM τdecay (at +40 mV) of the fast inactivating component in Kv4.3−/− LV apex myocytes was 59 ± 2 ms (n = 60), a value that is nearly identical to the mean ± SEM τdecay of 63 ± 1 ms (n = 81) in WT LV apex cells. These observations are quite different from previously published findings on Kv4.2−/− LV apex cells, in which Ito,f was eliminated [15]. In addition, the slow inactivating transient Kv current, Ito,s, was shown to be upregulated in Kv4.2−/− LV apex cells [15]. Although undetectable in WT LV cells [6,16], Ito,s was readily distinguished from Ito,f by markedly slower inactivation kinetics (τdecay ≈200 ms) [6,16]. The analyses here revealed two LV apex myocytes (one Kv4.3−/− and one WT) with τdecay values>90 ms. The measure values (~90 ms and ~100 ms), however, are considerably faster than the τdecay for Ito,s [6,16], indicating that the fast inactivating current in Kv4.3−/− LV apex myocytes is Ito,f, and that there is no evidence for Ito,s upregulation in these cells. As illustrated in Figure 3B, Ito,f was detected in all Kv4.3−/− LV apex myocytes, and mean ± SEM Ito,f densities (at +40 mV) in Kv4.3−/− (28.3 ± 1.2 pA/pF; n = 60) and WT (31.7 ± 1.1 pA/pF; n = 81) LV apex cells were similar (Table 2). In addition, the frequency histogram of Ito,f densities (Figure 3C) does not reveal any obvious differences in the distributions of Ito,f densities in Kv4.3−/− and WT LV apex myocytes. Similar results were obtained in experiments completed on cells isolated from the RV of WT and Kv4.3−/− animals (data not shown).

Analyses of the other Kv currents, IK,slow and Iss, did not reveal any significant differences in current densities or properties in Kv4.3−/− and WT LV apex myocytes (Table 2). IK1 densities in Kv4.3−/− (−8.6 ± 0.3 pA/pF; n = 60) and WT (−9.4 ± 0.3 pA/pF; n = 81) LV apex cells were also similar.

3.2.2. The properties of Ito,f channels in Kv4.3−/− myocytes are similar to WT Ito,f

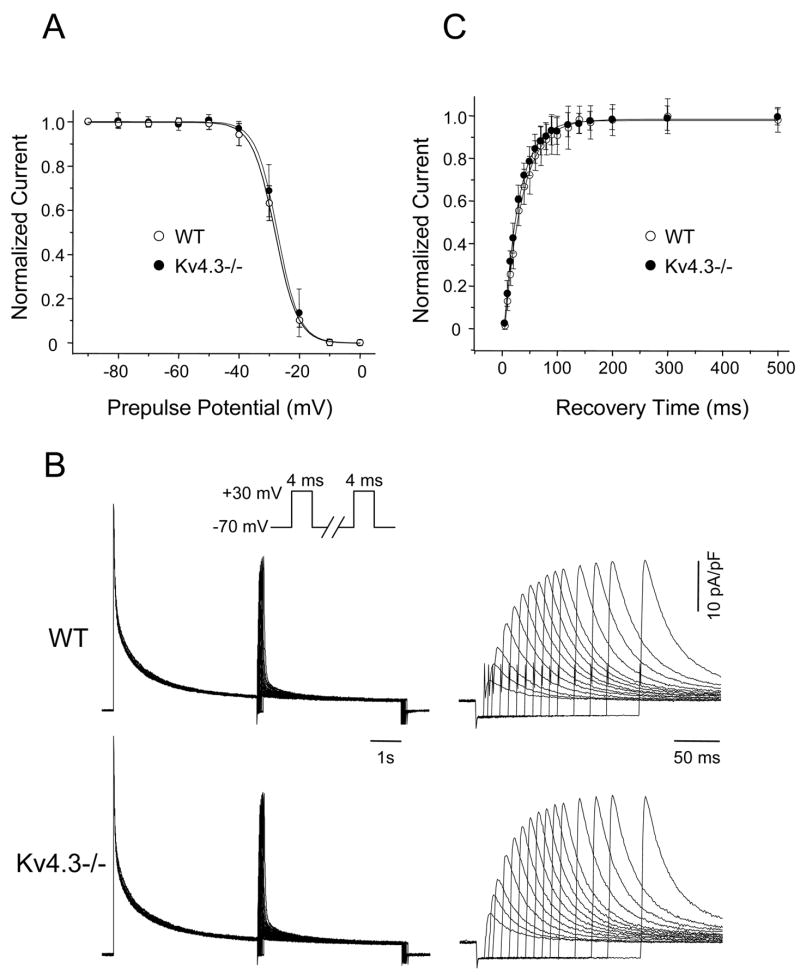

Previous studies suggest that functional Ito,f channels in rodent ventricular myocytes are heteromeric, composed of Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 α subunits [2]. In addition, it has been reported that the properties of the Kv currents produced on (over) expression of Kv4.2 in mouse neonatal ventricular myocytes are distinct from those of the currents produced on co-expression of Kv4.2 and Kv4.3. The voltage dependence of steady-state inactivation, for example, is shifted and the rate of recovery from steady-state inactivation is slower for homomeric Kv4.2 channels than for heteromeric Kv4.2+Kv4.3 channels [11]. Subsequent experiments here, therefore, were focused on determining if Ito,f channel properties in Kv4.3−/− ventricular myocytes are altered, as would be expected for homomeric Kv4.2 channels.

The voltage dependences of steady-state inactivation of the Kv currents in Kv4.3−/− and WT LV apex myocytes were examined using a double pulse protocol (see Materials and Methods), and Ito,f amplitudes were obtained from double exponential fits to the decay phases of the currents evoked during each test depolarization. As illustrated in Figure 4A, the normalized mean steady-state inactivation curves for Ito,f in Kv4.3−/− (n = 12) and WT (n = 9) LV apex myocytes are indistinguishable. Fits to the steady-state inactivation data for each cell to a Boltzmann equation revealed that mean ± SEM V1/2 values for Ito,f in Kv4.3−/− (−27.1 ± 0.7 mV; n = 12) and WT (−27.9 ± 0.4 mV; n = 9) LV apex cells were not significantly different; mean ± SEM k values obtained from these fits were also similar in Kv4.3−/− (3.5 ± 0.1; n = 12) and WT (3.9 ± 0.3; n = 9) LV apex cells.

Figure 4. Properties of Ito,f in Kv4.3−/− and WT ventricular myocytes are indistinguishable.

A,Voltage dependence of steady-state inactivation of Ito,f in Kv4.3−/− (n = 12) and WT (n = 9) LV apex myocytes. Data were obtained using a two-pulse protocol and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. Mean ± SEM normalized current amplitudes are plotted as a function of prepulse potential; Solid lines represent the best single Boltzmann fits to the mean data. B, Representative records illustrating recovery from steady-state inactivation of the Kv currents in WT and Kv4.3−/− LV apex myocytes; the same currents recorded during the first 500 ms are displayed on an expanded time scale on the right. Data were obtained using the three pulse protocol illustrated above the current records and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. C, Mean ± SEM normalized recovery data for Ito,f in Kv4.3−/− (n = 14) and WT (n = 15) LV apex cells are plotted as a function of the recovery period; solid lines represent best (single exponential) fits to the mean data.

Kv4 encoded Ito,f channels are characterized by fast recovery from steady-state inactivation as well as fast inactivation [3]. Although Kv1 channels such as Kv1.4 also inactivate fast [20] and some Kv1 encoded delayed rectifiers can be converted to fast inactivating transient currents by association with Kvβ1 or Kvβ3 accessory subunits [21,22], these currents typically recover slowly from inactivation (time constant 1–2 s) [20,21]. It has also been reported that the time course of recovery from steady-state inactivation for homomeric Kv4.2 channels expressed in neonatal mouse myocytes is slower than that of heteromeric Kv4.2+Kv4.3 channels [11]. Further experiments were completed here, therefore, to compare the time course of Ito,f recovery in Kv4.3−/− and WT LV apex myocytes (see Materials and Methods). Representative current traces are presented in Figure 4B; the currents recorded during the first 500 ms are shown on expanded time scale on the right side of Figure 4B. At short times, Ito,f is the main component of recovery and, as is evident, the currents in Kv4.3−/− myocytes recovered as rapidly as the WT currents. In addition, the mean normalized recovery data for Ito,f in Kv4.3−/− and WT LV apex myocytes were well fitted by single exponential functions (Figure 4C). Analyses of the recovery data for Ito,f in each cell revealed no significant difference in the mean ± SEM time constants of Ito,f recovery in Kv4.3−/− (27.5 ± 1.3 ms; n = 14) and WT (33.5 ± 1.8 ms; n = 15) LV apex cells. Similar results were obtained in experiments on RV myocytes (data not shown).

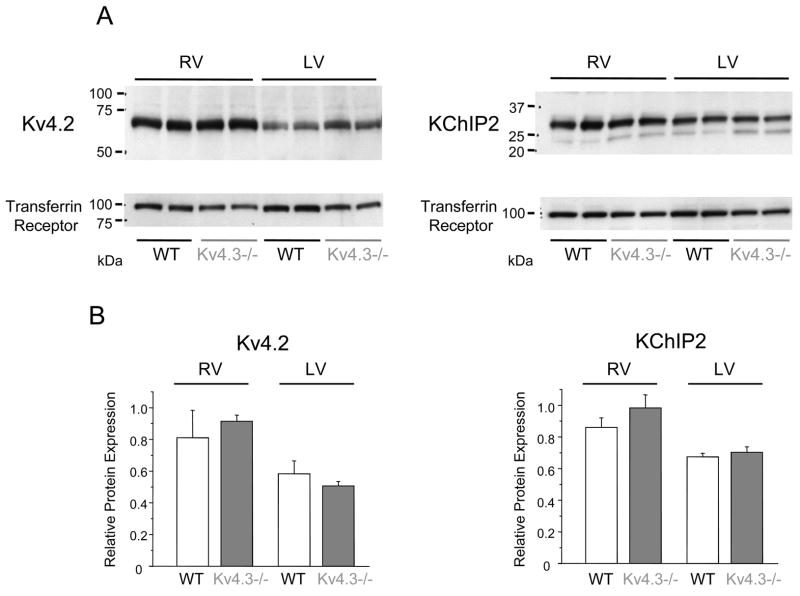

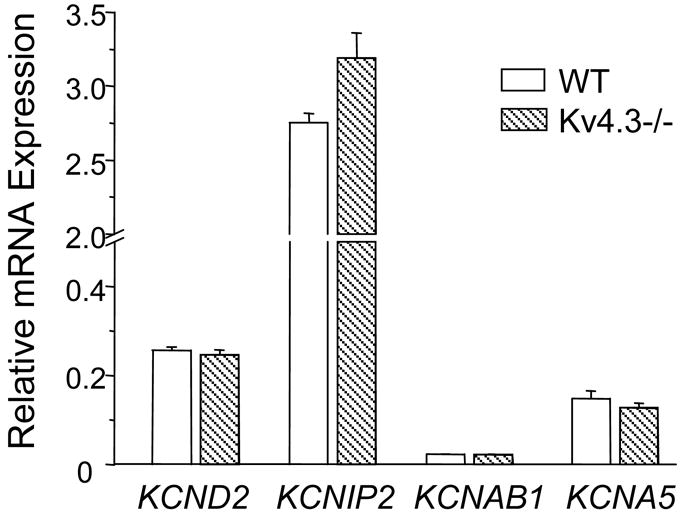

3.3. Expression of other Ito,f channel subunits is unaffected in Kv4.3−/− ventricles

The finding that mouse ventricular Ito,f expression is not strikingly affected by the elimination of Kv4.3 prompted us to speculate that the expression of the other Kv4 α-subunit, Kv4.2, might be upregulated in Kv4.3−/− ventricles to compensate for the loss of Kv4.3. To test this hypothesis, quantitative RT-PCR experiments using SYBR Green primers specific for Kv4.2 (see Table 1) were completed. These analyses revealed that the expression level of the KCND2 (Kv4.2) transcript in Kv4.3−/− LV was not significantly different from WT LV (Figure 5). In addition, quantitative RT-PCR analyses also revealed no significant differences in mRNA expression levels of genes (KCNIP2 and KCNAB1) encoding the Ito,f channel accessory subunits KChIP2 and Kvβ1 [23,24] in Kv4.3−/− and WT LV.

Figure 5. Kv subunit mRNA expression levels are unaffected in Kv4.3−/− LV.

Expression levels of the KCND2 (Kv4.2) KCNIP2 (KChIP2), KCNAB1 (Kvβ1) and KCNA5 (Kv1.5) transcripts were analyzed quantitatively using SYBR Green primers (see Table 1). Data were normalized to the expression level of the HPRT gene, as described in Materials and Methods.

Further experiments were completed to test the possibility that there were posttranscriptional alterations in the expression levels of Ito,f channel subunits in Kv4.3−/−ventricles. As illustrated in Figure 6A, Western blot analyses revealed that Kv4.2 protein expression levels in Kv4.3−/− and WT ventricles were indistinguishable. In addition, the expression of KChIP2 protein, which has previously been shown to be markedly reduced in Kv4.2−/− mouse ventricles [15], was unaffected in Kv4.3−/− ventricles (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Ito,f channel protein expression levels in Kv4.3−/− ventricles.

A, Representative Western blots of adult WT (n = 2) and Kv4.3−/− (n = 2) mouse RV and LV proteins (total lysates) probed with a polyclonal anti-Kv4.2 or a monoclonal anti-KChIP2 antibody (upper panels). To compare protein expression levels in samples from different animals and to ensure equal loading, the blots were also probed with a monoclonal anti-Transferrin receptor antibody (lower panels). B, Summary of the expression levels of Kv4.2 (left) and KChIP2 (right) proteins in WT (n = 4) and Kv4.3−/− (n = 4) mouse ventricles. Films from individual experiments were scanned, and the densities of bands were measured. These data were then normalized to the expression levels of the Transferrin receptor in the same sample, and mean ± SEM normalized densities are plotted.

4. Discussion

The results presented here demonstrate that the targeted disruption of the KCND3 locus has no striking effects on functional Ito,f expression in adult mouse ventricles. Mean Ito,f densities are similar and the time- and voltage-dependent properties of Ito,f in Kv4.3−/− LV apex (and RV) myocytes are indistinguishable from those measured in WT cells. In addition, the molecular/biochemical studies detailed here suggest that the maintenance of Ito,f expression in Kv4.3−/− ventricles does not reflect the upregulation of the other Kv4 α subunit, Kv4.2, which was previously demonstrated to contribute to Ito,f in these cells [15]. In addition, the expression of the Ito,f channel accessory subunit, KChIP2, is not measurably affected in Kv4.3−/− ventricles.

4.1. Effects of the targeted deletion of Kv4.3 and Kv4.2 are distinct

Considerable evidence suggests that Ito,f channels in rodent ventricles reflect the heteromeric assembly of the Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 α subunits [2]. Recent studies [15] and the results presented here, however, demonstrate that the effects of the disruption of Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 on Ito,f channel expression in mouse ventricles are distinct. In marked contrast to the lack of effect of the loss of Kv4.3 demonstrated here, the targeted deletion of Kv4.2 results in the complete elimination of mouse ventricular Ito,f [15]. Interestingly, Kv4.3 message/protein expression is not affected in Kv4.2−/− ventricles, suggesting that Kv4.3 cannot form functional Ito,f channels in mouse ventricular myocytes in the absence of Kv4.2 [15]. Taken together, these results demonstrate distinct roles for the Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 α subunits in the generation of functional mouse ventricular Ito,f channels, with Kv4.2 playing the essential role.

Interestingly, marked differences in the expression patterns of the Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 subunits in rodent ventricles have been documented; Kv4.2 expression levels vary in different regions of the ventricles, whereas Kv4.3 expression levels are similar throughout the ventricles [8,10,11]. The differences in Kv4.2 expression correlate with observed regional variations in Ito,f densities [6,7,10,11], an observation interpreted as suggesting that Kv4.2 plays an important role in producing the regional gradation in Ito,f expression in rodent ventricles.

Another striking and previously recognized difference between Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 is that these subunits play distinct roles in the generation of Ito,f channels in rodents and large mammals [2]. In human and canine ventricles, for example, Ito,f channels appear to reflect the homomeric assembly of Kv4.3, because the Kv4.2 transcript is barely detectable [8]. As noted above, however, Kv4.3 subunits do not generate functional Ito,f channels in mouse ventricles in the absence of Kv4.2 [15]. Based on the fact that the Kv4.3 sequence is highly conserved among mammalian species (only a six-amino acid difference between humans and mice) [25], these combined observations suggest that there are species-specific differences in the regulation of Kv4.3-Kv4.3 subunit assembly or trafficking and/or in the expression or functioning of accessory or modulatory proteins necessary for the generation of functional Ito,f channels.

4.2. Relationship to previous studies

The lack of any significant effect of the in vivo elimination of Kv4.3 described here appears to be in conflict with the results of previous studies in which Kv4.3 expression was manipulated in isolated cells in vitro. Experiments using AsODN targeted against Kv4.3, for example, demonstrated marked attenuation of Ito,f density (by 50–60%) in isolated neonatal rodent ventricular myocytes [11,14]. Similar effects were seen with AsODN targeting Kv4.2 [11,14]. It was also demonstrated that the properties of the channels produced on heterologous co-expression of Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 in HEK-293 cells or neonatal mouse ventricular myocytes inactivate faster and recover from inactivation faster than homomeric Kv4.2 or Kv4.3 channels [11]. Taken together with biochemical data demonstrating co-immunoprecipitation of Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 from adult mouse ventricles, these observation were interpreted as suggesting that functional mouse ventricular Ito,f channels reflect the heteromeric assembly of Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 [11]. The result presented here, however, demonstrate that the time- and voltage-dependent properties of Ito,f in Kv4.3−/− ventricular myocytes (which must reflect homomeric Kv4.2 channels) are indistinguishable from those of native (putatively heteromeric Kv4.2+Kv4.3) Ito,f channels. Clearly, these results might be interpreted as suggesting that functional adult mouse ventricular Ito,f channel actually reflect the homomeric assembly of Kv4.2. Alternatively, these seemingly contradictory results might reflect the fact that different cells and/or experimental conditions were employed in the present, compared with the previous, studies. The AsODN and overexpression studies were acute experiments performed on WT neonatal mouse ventricular myocytes in vitro, whereas the present study utilized adult myocytes from animals lacking KCND3. The factors regulating the functional cell surface expression and the properties of Ito,f channels in these different cells/experiments could be distinct.

In this context, it is also of interest to note that the properties of homomeric Kv4.3 encoded Ito,f channels in canine ventricular myocytes are similar to those of (heteromeric) Ito,f channels in rodent ventricular myocytes [2,26]. Indeed, canine ventricular Ito,f channels inactivate even faster (τdecay<30 ms) than rodent ventricular Ito,f channels [26] These observations suggest species- and/or cell type-specific differences in the molecular regulation of Ito,f channels, perhaps owing to differences in the expression of accessory and/or regulatory proteins, and/or to differences in the posttranslational processing of (pore-forming or accessory) channel subunits.

KChIP2 is a potential candidate accessory subunit to regulate the expression/properties of ventricular Ito,f channels. Co-expression of KChIP2, for example, facilitates the membrane expression and modifies the properties of Kv4 channels in heterologous expression systems [27]. Biochemical studies revealed that most of the KChIP2 protein in adult ventricular myocytes is associated with Kv4 α subunits in vivo [11]. In addition, targeted disruption of the KCNIP2 (KChIP2) locus abolishes Ito,f [23], suggesting that KChIP2 is required for the generation of mouse ventricular Ito,f channels. Interestingly, Ito,f elimination in Kv4.2−/− ventricles is accompanied by the marked reduction in KChIP2 protein expression [15]. The results here, however, demonstrate that KChIP2 expression is not affected by the deletion of Kv4.3.

The Kvβ accessory subunits also affect the expression and/or the properties of Kv4 channels. In heterologous cells, for example, Kvβ1 increases surface membrane expression of Kv4.3 channels [28], and modulates the properties of Kv4.2 currents [29]. Kvβ1 subunits also co-immunoprecipitate from adult mouse ventricles, and most of the Kvβ1.1 protein was shown to be associated with Kv4.2, Kv4.3 and KChIP2 [24]. Interestingly, the targeted deletion of Kvβ1 attenuates Ito,f density in mouse [24]. Although these observations suggest the interesting possibility that increased expression of Kvβ1 subunits might play a role in the maintenance of Ito,f in the Kv4.3−/− ventricles, the results here demonstrate that Kvβ1 transcript expression is not altered in Kv4.3−/− ventricles. Although the present study does not suggest roles for KChIP2 or Kvβ1, it is certainly possible that there are different (yet to be identified) accessory/regulatory proteins involved in the generation of myocardial Ito,f channels. Interestingly, a novel Kv4 accessory subunit, DPP6, a member of the diaminopeptidyl transferase (DPP) family of proteins was identified in brain, and shown to regulate the expression and the properties of Kv4 channels [30,31]. Although at least one additional member (DPP10) of this family has been identified as a Kv4 channel regulatory subunit [32], neither DPP6 nor DPP10 has been shown to be expressed in the myocardium. Nevertheless, there may be other cardiac specific regulators of Kv4 encoded Ito,f channels.

4.3. Conclusions

Although considerable evidence suggests that Ito,f channels in rodent ventricles are heteromeric complexes reflecting the assembly of the pore-forming Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 α subunits, together with the accessory KChIP2 and Kvβ1 subunits, the results presented here clearly demonstrate that Kv4.3 is not required for the generation of these channels. The studies here also revealed that the properties of Ito,f in Kv4.3−/− and WT ventricular myocytes are indistinguishable, and that the expression levels of the other subunits, Kv4.2, KChIP2 and Kvβ1, known to contribute to the generation of Ito,f are unaffected in Kv4.3−/− ventricles. The results here also demonstrate that there are many gaps in our understanding of the mechanisms controlling the biophysical properties and the functional cell surface expression of cardiac Ito,f (and other ion) channels. Further studies aimed at defining the expression and functioning of Ito,f channel accessory and regulatory proteins and the functional role (s) of posttranslational modifications of these subunits will be required to elucidate these mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Mr. Jefferson Gomes and Ms. Amy Coleman for assistance with myocyte isolations, and Mr. Rick Wilson for screening and maintaining the Kv4.3−/− mouse colony. The authors also thank the National Institutes of Health (HL-034161 and HL-066388 to JMN) and the Heartland Affiliate of the American Heart Association (Postdoctoral Fellowship to CM) for the financial support provided.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Oudit GY, Kassiri Z, Sah R, Ramirez RJ, Zobel C, Backx PH. The molecular physiology of the cardiac transient outward potassium current (Ito) in normal and diseased myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:851–72. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nerbonne JM, Kass RS. Molecular physiology of cardiac repolarization. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:1205–53. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00002.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel SP, Campbell DL. Transient outward potassium current, ‘Ito’, phenotypes in the mammalian left ventricle: underlying molecular, cellular and biophysical mechanisms. J Physiol. 2005;569:7–39. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.086223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark RB, Bouchard RA, Salinas-Stefanon E, Sanchez-Chapula J, Giles WR. Heterogeneity of action potential waveforms and potassium currents in rat ventricle. Cardiovasc Res. 1993;27:1795–9. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.10.1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Litovsky SH, Antzelevitch C. Transient outward current prominent in canine ventricular epicardium but not endocardium. Circ Res. 1988;62:116–26. doi: 10.1161/01.res.62.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunet S, Aimond F, Li H, Guo W, Eldstorm J, Fedida D, et al. Heterogeneous expression of repolarizing, voltage-gated K+ currents in adult mouse ventricles. J Physiol. 2004;559:103–20. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.063347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dixon JE, McKinnon D. Quantitative analysis of potassium channel mRNA expression in atrial and ventricular muscle of rats. Circ Res. 1994;75:252–60. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.2.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dixon JE, Shi W, Wang HS, McDonald C, Yu H, Wymore RS, et al. Role of the Kv4.3 K+ channel in ventricular muscle: A molecular correlate for the transient outward current. Circ Res. 1996;79:659–668. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.4.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marionneau C, Couette B, Liu J, Li H, Mangoni ME, Nargeot J, et al. Specific pattern of ionic channel gene expression associated with pacemaker activity in the mouse heart. J Physiol. 2005;562:223–34. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.074047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wickenden AD, Jegla TJ, Kaprielian R, Backx PH. Regional contributions of Kv1.4, Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 to transient outward K+ current in rat ventricle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1999;276:H1599–607. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.5.H1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo W, Li H, Aimond F, Johns DC, Rhodes KJ, Trimmer JS, et al. Role of heteromultimers in the generation of myocardial transient outward K+ currents. Circ Res. 2002;90:586–93. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000012664.05949.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johns DC, Nuss HB, Marbán E. Suppression of neuronal and cardiac transient outward currents by viral gene transfer of dominant-negative Kv4.2 constructs. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31598–603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barry DM, Xu H, Schuessler RB, Nerbonne JM. Functional knockout of the transient outward current, Long-QT syndrome, and cardiac remodeling in mice expressing a dominant-negative Kv4 α subunit. Circ Res. 1998;83:560–567. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.5.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fiset C, Clark RB, Shimoni Y, Giles WR. Shal-type channels contribute to the Ca2+-independent transient outward K+ current in rat ventricle. J Physiol. 1997;500:51–64. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo W, Jung WE, Marionneau C, Aimond F, Xu H, Yamada KA, et al. Targeted deletion of Kv4.2 eliminates Ito,f and results in electrical and molecular remodeling, with no evidence of ventricular hypertrophy or myocardial dysfunction. Circ Res. 2005;97:1342–50. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000196559.63223.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu H, Guo W, Nerbonne JM. Four kinetically distinct depolarization-activated K+ currents in adult mouse ventricular myocytes. J Gen Physiol. 1999;113:661–77. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.5.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔDelta;CT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Kok JB, Roelofs RW, Giesendorf BA, Pennings JL, Wass ET, Feuth T, et al. Normalization of gene expression measurements in tumor tissues: comparison of 13 endogenous control genes. Lab Invest. 2005;85:154–9. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitchell GF, Jeron A, Koren G. Measurement of heart rate and Q-T interval in the conscious mouse. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1998;274:H747–51. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.3.H747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo W, Xu H, London B, Nerbonne JM. Molecular basis of transient outward K+current diversity in mouse ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 1999;521:587–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00587.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rettig J, Heineman SH, Wunder F, Lorra C, Parcej DN, Dolly JO, et al. Inactivation properties of voltage-gated K+ channels altered by presence of β-subunit. Nature. 1994;369:289–94. doi: 10.1038/369289a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leicher T, Bähring R, Isbrandt D, Pong O. Coexpression of the KCNA3B gene product with Kv1.5 leads to a novel A-type potassium channel. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:35095–101. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.52.35095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuo HC, Chang CF, Clark RB, Lin JJC, Lin JLC, Hoshijima M, et al. A defect in the Kv channel-interacting protein 2 (KChIP2) gene leads to a complete loss of Ito,f and confers susceptibility to ventricular tachycardia. Cell. 2001;107:801–13. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00588-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aimond F, Kwak SP, Rhodes KJ, Nerbonne JM. Accessory Kvβ1 subunits differentially modulate the functional expression of voltage-gated K+ channels in mouse ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 2005;96:451–8. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000156890.25876.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van der Heyden MAG, Wijnhoven TJM, Opthof T. Molecular aspect of adrenergic modulation of the transient outward current. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;71:430–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tseng GN, Hoffman BF. Two components of transient outward current in canine ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 1989;64:633–47. doi: 10.1161/01.res.64.4.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.An WF, Bowlby MR, Betty M, Cao J, Li HP, Mendoza G, et al. Modulation of A-type potassium channels by a family of calcium sensors. Nature. 2000;403:553–6. doi: 10.1038/35000592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang EK, Alvira MR, Levitan ES, Takimoto K. Kvβ subunits increase expression of Kv4.3 channels by interacting with their C termini. J Biol Chemi. 2001;276:4839–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004768200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pérez-García MT, López-López JR, González C, Kvβ1 2 subunit coexpression in HEK293 cells confers O2 sensitivity to Kv4.2 but not shaker channels. J Gen Physiol. 1999;113:897–907. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.6.897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nadal MS, Ozaita A, Amarillo Y, Vega-Saenz de Miera E, Ma Y, Mo W, et al. The CD26-related dipeptidyl aminopeptidase-like protein DPPX is a critical component of neuronal A-type K+ channels. Neuron. 2003;37:449–61. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01185-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Radicke S, Cotella D, Graf EM, Ravens U, Wettwer E. Expression and function of dipeptidyl-aminopeptidase-like protein 6 as a putative β-subunit of human cardiac transient outward current encoded by Kv4.3. J Physiol. 2005;565:751–6. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.087312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jerng HH, Kunjilwar K, Pfaffinger PJ. Multiprotein assembly of Kv4.2, KChIP3 and DPP10 produces ternary channel complexes with ISA-like properties. J Physiol. 2005;568:767–88. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.087858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]