Abstract

Background

Two promising recombinant meningococcal protein vaccines are in development. One contains factor H–binding protein (fHBP) variants (v.) 1 and 2, whereas the other contains v.1 and 4 other antigens discovered by genome mining (5 component [5C]). Antibodies against fHBP are bactericidal against strains within a variant group. There are limited data on the prevalence of strains expressing different fHBP variants in the United States.

Methods

A total of 143 group B isolates from patients hospitalized in the United States were tested for fHBP variant by quantitative polymerase chain reaction, for reactivity with 6 anti-fHBP monoclonal antibodies (MAb) by dot immunoblotting, and for susceptibility to bactericidal activity of mouse antisera.

Results

fHBP v.1 isolates predominated in California (83%), whereas isolates expressing v.1 (53%) or v.2 (42%) were common in 9 other states. Isolates representative of 5 anti-fHBP MAb–binding phenotypes (70% of isolates) were highly susceptible to anti–fHBP v.1 or v.2 bactericidal activity, whereas 3 phenotypes were ~50% susceptible. Collectively, antibodies against the fHBP v.1 and v.2 vaccine and the 5C vaccine killed 76% and 83% of isolates, respectively.

Conclusions

Susceptibility to bactericidal activity can be predicted, in part, on the basis of fHBP phenotypes. Both vaccines have the potential to prevent most group B disease in the United States.

Neisseria meningitidis is an important cause of bacterial sepsis and meningitis worldwide. Polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccines have been developed to protect against disease caused by strains with capsular groups A, C, W-135, or Y [1–4]. However, group B isolates, for which there is currently no broadly protective vaccine, accounted for 36%–49% of meningococcal isolates in the Active Bacterial Core Surveillance Reports of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from 2002 to 2005 (available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dbmd/abcs/survreports.htm) and an even higher proportion of disease-producing isolates in Europe [5]. The group B polysaccharide is a self-antigen [6–8]. Therefore, most recent investigations of group B vaccine candidates have focused on noncapsular antigens [9–11], because there are safety issues for a capsular-based vaccine that could elicit autoantibodies.

A number of recombinant protein antigens have been investigated. These include proteins that are abundant in the outer membrane [12] (e.g., PorA [13, 14] and PorB [13]) or that are highly conserved, such as NspA [15]. Also, proteins that are not necessarily abundant but that have been identified by genomic studies and are predicted to be surface accessible and conserved in Neisseria species are being investigated [16, 17]. Some of these appear to be promising vaccine candidates in light of their ability to elicit serum bactericidal antibody against genetically diverse strains in mice [18–20]. These studies led to the development of an experimental, 5-component (5C), recombinant protein vaccine [21] that is currently being evaluated in humans [22].

The 5C vaccine contains 2 recombinant fusion proteins (genome-derived neisserial antigen [GNA] 2132-1030 and GNA 2091-1870) and 1 individual recombinant protein, NadA. The most potent immunogen in the 5C vaccine appears to be GNA 1870, which is also known as “lipoprotein 2086” [23]. This protein recently has been renamed “factor H–binding protein” (fHBP) [24], to reflect the discovery that one of its functions is to bind factor H (fH), an important complement down-regulatory protein (see below) [25–27]. A second recombinant-protein vaccine that contains both the fHBP variant (v.) 1 and 2 proteins also is under development.

In a previous study, mouse antiserum raised against the 5C recombinant-protein vaccine was bactericidal against 78%–98% of a panel of 85 strains, depending on the adjuvant used in the vaccine formulation [21]. However, rabbit complement was used for measurement of bactericidal activity, which is known to greatly augment the susceptibility of N. meningitidis to bacteriolysis [28, 29]. Also, N. meningitidis recently has been shown to bind fH [24, 30], which provides a novel mechanism by which the organism can inactivate specific complement components and evade complement-mediated killing. Binding is specific for human fH [31]. Lack of binding of rabbit fH may explain why N. meningitidis is more susceptible to killing by rabbit complement than by human complement. Therefore, serum bactericidal susceptibility data generated with rabbit complement may not be reliable for predicting the potential efficacy of a group B vaccine, particularly one that contains fHBP as one of its principal antigens.

In the present study, we analyzed the prevalence of fHBP variants in 3 collections of disease-producing group B meningococcal isolates from different regions of the United States. We also tested the susceptibility of the isolates to human complement–mediated killing by mouse antisera prepared against each of the individual fHBP variants and the 5C vaccine. The data permit estimates of the maximum potential strain coverage in different regions of the United States by the 5C vaccine containing fHBP v.1 as one of its antigens and by a 2-component vaccine containing fHBP v.1 and v.2.

METHODS

Meningococcal isolate collections

Group B meningococci (n = 144) were obtained from 3 collections. The California collection consisted of consecutive isolates referred to the California Department of Health in 2003 and 2004. These isolates were from 48 patients of a variety of ages hospitalized in 22 counties. The Maryland collection was from cases of meningococcal disease in residents of Maryland of a variety of ages who were hospitalized between 1995 and 2005 (n = 50). These isolates were collected as part of the Maryland Active Bacterial Core Surveillance project [32]. The third collection was from a prospective, multicenter surveillance study of meningococcal disease in children (age 0–16 years) who were admitted to 10 pediatric hospitals in 9 US states between 2001 and 2005 (n = 46) [33].

The multicenter collection included 8 isolates from 2 hospitals in California. To avoid potential overlap between these isolates and those in the California collection, we obtained information on the dates of isolation and compared respective sequence types (STs), quantitative polymerase chain reaction (QPCR) results, and fHBP monoclonal antibody (MAb) reactivity. We identified 1 duplicated isolate, which was omitted from the data analysis, leaving 143 isolates. In addition, for purposes of data analysis, the 7 isolates from the multicenter collection that originated in California were grouped with the California collection.

Growth and preparation of meningococcal strains

N. meningitidis strains were cultured, and heat-killed cells were prepared for QPCR and for dot immunoblotting as described elsewhere [34].

Identification of alleles by QPCR

Grouping of fHBP variants was performed by QPCR as described elsewhere [34]. We used QPCR to determine whether the nadA gene was present by use of the specific primers NadA IF (5′-AACCTTACAACGTGGGTCGGTTCA-3′) and NadA IR (5′-ACTCGTAATTGACGCCGACATGGT-3′) under reaction conditions that have been described elsewhere [34]. A positive signal was indicated by a cycle threshold (CT) value between 16.6 and 26.9, and a negative signal was indicated by a CT value between 28.3 and 40.0. Amplification of the 16S rRNA gene [34] was performed to account for differences in the levels of template DNA. The difference between the 16S result and a positive fHBP or nadA signal was <5.8 CT; for a negative signal, it was >10.9 CT.

Preparation of Mabs

MAbs against recombinant fHBP v.1 (from strain MC58)—JAR 1, 3, and 5—have been described elsewhere [35]. MAbs against recombinant fHBP v.2 (from strain 2996)—JAR 10, 11, and 13—were made using a similar procedure. As described below, JAR 10 cross-reacts with a subset of strains that express fHBP v.1, and JAR 13 cross-reacts with some v.3 strains.

Detection of proteins by dot immunoblotting

Heat-killed cell suspensions (~1 × 108 cells in 100 μL) were applied to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad) under vacuum. The primary antibody was either a MAb (1–10 μg/mL) or an appropriate dilution (1:5000 to 1:10,000) of mouse polyclonal antiserum to fHBP v.1, v.2, and v.3 or to NadA. The secondary antibody was a 1:10,000 dilution of rabbit anti–mouse IgG/IgA/IgM–horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Invitrogen). The membranes were developed with Western Lightning chemiluminescent substrate (Perkin-Elmer) and exposed to X-OMAT film (Eastman Kodak).

Bactericidal assays

Bactericidal assays were performed as described elsewhere using mid-log-phase bacteria grown in Mueller-Hinton broth to an OD620 of ~ 0.6 [36, 37]. The complement source was human serum that was characterized as described elsewhere [37]. The buffer was Dulbecco’s PBS with Ca2+ and Mg2+ (Mediatech) containing 1% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich). The antisera against the fHBP v.1, 2, or 3 protein [19]; GNA 2132 [16, 20]; NadA [18]; or the 5C vaccine [21] were prepared in mice by use of complete and incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (Sigma-Aldrich). Assays of selected NadA-positive isolates were repeated using late-log-phase bacteria grown to an OD620 of 0.8–0.9 [18].

RESULTS

STs, fHBP gene variants, and nadA presence

Table 1 summarizes the distribution of STs among the isolates. Thirty-one percent of the isolates from patients in California had identical respective ST, porA, porB, and fetA genotypes, which were consistent with a specific clonal group. Isolates with this genotype were less prevalent in the other 2 collections (≤6%). With the exception of isolates from 3 patients hospitalized during a 2-week period in 1 county, the remaining California isolates with this genotype came from patients hospitalized at different times of the year and/or in different counties. Therefore, as a group the isolates were not part of a specific outbreak.

Table 1.

Distribution of sequence types (STs) among group B meningococcal isolates.

| Isolates, % | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ST complex (lineage) | California(n p 55) | Maryland(n p 50) | Multicentera(n p 38) |

| ST-32, clonalb (ET-5) | 31 | 6 | 3 |

| ST-32, otherc (ET-5) | 33 | 26 | 29 |

| ST-41/44 (lineage III) | 13 | 26 | 34 |

| ST-162 | 6 | 14 | 5 |

| ST-269 | 0 | 10 | 3 |

| Otherd | 17 | 18 | 26 |

Seven isolates from the multicenter collection originated in California and are grouped with the California isolates (see Methods).

Defined as ST-32; porA VR1 and VR2 of 7,16–20; and porB of 3–24 and fetA of 3-3.

ST-32 isolates with combinations of porA, porB, and fetA genotypes different from that of the clonal group.

No single ST complex comprised >5% of isolates in this category.

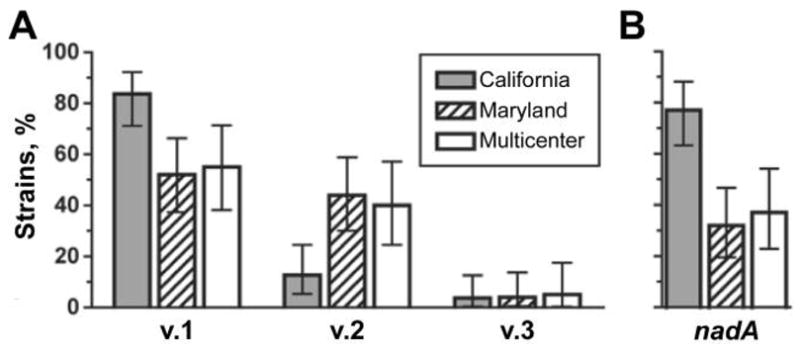

QPCR results showed that the fHBP gene was present in all 143 isolates. Collectively, 65% were fHBP v.1, 31% were v.2, and 4% were v.3. As shown in figure 1A, the fHBP v.1 gene predominated in isolates from California (83% v.1, 13% v.2, and 4% v.3), whereas the Maryland collection had 52%, 44%, and 4% and the multicenter collection had 57%, 37% and 4%, respectively. The respective percentages in the latter 2 collections were similar to each other and were collectively different from those in the California collection (P <.01, χ2 test). In all, 71 isolates (50%) were nadA positive; 77% of the California isolates were positive for the nadA gene, compared with 32% and 37%, respectively, in the Maryland and multicenter collections (P <.001) (figure 1B). All of the ST-32 isolates with identical respective porA, porB, and fetA genotypes (table 1) were positive for the fHBP v.1 and nadA genes. If these isolates are removed from the analysis of the frequencies of fHBP variants and nadA, the respective proportions in the 3 collections are still significantly different (P <.02).

Figure 1.

Percentage of fHBP variant (v.) 1, 2, or 3 genes (A) and nadA genes (B), as determined by quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Shaded bars, California isolates; hatched bars, Maryland isolates; white bars, multicenter isolates.

Reactivity with anti-fHBP and anti-NadA antibodies

Ninety-seven percent of isolates expressed fHBP, as detected by dot immunoblotting using polyclonal antiserum prepared against fHBP v.1, v.2, and v.3. Of those with detectable expression of fHBP, there was moderate (up to 10-fold) variation in the quantity expressed by the different isolates. Of 71 isolates with the nadA gene, as detected by QPCR, 99% expressed the NadA protein, as detected by dot immunoblotting with polyclonal anti-NadA antiserum. NadA expression in cultures grown to the same optical density (0.8–0.9) was estimated to differ by as much as 100-fold. All of the isolates that were negative for the nadA gene by QPCR also were negative by dot immunoblotting.

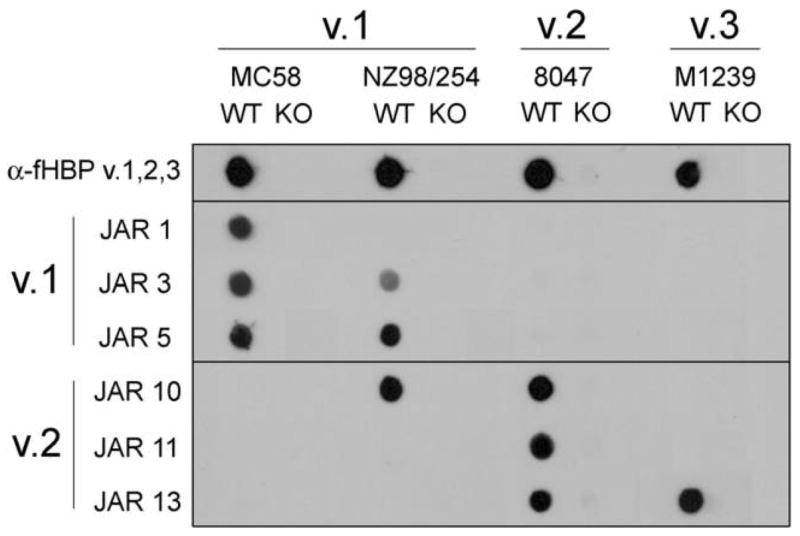

The 6 MAbs made against fHBP v.1 or v.2 differed in their reactivity on whole-cell dot immunoblots with a panel of control strains and, therefore, appear to recognize unique epitopes. The MC58 wild-type (WT) strain (fHBP v.1) was positive by dot immunoblotting for reactivity with MAbs JAR 1, 3, and 5 (figure 2), which were prepared against recombinant fHBP v.1 expressed from the gene from MC58 [35]. In contrast, the MC58 WT strain did not react with MAbs JAR 10, 11, or 13, which were prepared against the recombinant fHBP v.2 expressed from the gene from strain 2996 (figure 2). None of the 6 MAbs bound to the MC58 fHBP knockout (KO) strain. Group B strain NZ98/254, which expresses a v.1 fHBP that is 91.3% identical to that of MC58 [35], was recognized by 2 of the anti–fHBP v.1 MAbs, JAR 3 and 5, as well as by the anti-v.2 MAb JAR 10. The 8047 WT strain, which expresses a v.2 fHBP, was recognized by all 3 of the anti-v.2 MAbs but by none of the anti-v.1 MAbs (figure 2). The M1239 WT strain, which expresses a v.3 fHBP, was recognized only by the anti-v.2 MAb JAR 13. The respective patterns of MAb reactivity can be used to describe different fHBP phenotypes. We established a binary system of nomenclature to indicate the pattern of reactivity of the fHBP MAbs in the order JAR 1, 3, and 5 (anti-v.1) followed by JAR 10, 11, and 13 (anti-v.2), with 1 indicating positive reactivity and 0 indicating no reactivity. Thus, the fHBP phenotype of the v.1 strain MC58 is 111-000, and that of the v.2 strain 8047 is 000–111.

Figure 2.

Anti–factor H–binding protein (fHBP) monoclonal antibody (MAb) reactivity with representative Neisseria meningitidis group B strains. Heat-killed, whole meningococci were applied to a membrane, which was probed with polyclonal antibody or MAb. Wild-type (WT) and fHBP knockout (KO) mutant strains from each variant group were tested. α-fHBP variant (v.) 1,2,3, mouse antisera raised against the individual fHBP v.1, v.2, and v.3 proteins and pooled; JAR 1, 3, and 5, MAbs raised against recombinant fHBP v.1; JAR 10, 11, 13, MAbs raised against recombinant fHBP v.2.

Next, we examined the fHBP MAb reactivity of the 143 isolates in the 3 collections. As summarized in table 2, among the 93 isolates expressing fHBP v.1, phenotype 111-000 was the most common (70% of v.1 isolates). Isolates with this fHBP phenotype were predominantly electrophoretic type (ET)–5 (89%), ST–32 (71%), and nadA positive (83%). Two other phenotypes, 011-000 and 011–100, constituted 9% and 10% of the v.1 isolates, respectively. These groups had heterogeneous STs, and only 11% and 38%, respectively, were nadA positive (P <.0001, compared with the proportion of nadA-positive 111-000 isolates). Other fHBP phenotypes (111-100, 001–100, and 000-000) collectively accounted for the remaining 11% of the v.1 isolates.

Table 2.

Prevalence of factor H–binding protein (fHBP) isolates, by fHBP phenotype.

| fHBP phenotypea | fHBP variant | Isolates, %b | Prototype strain | Predominant STc (ET) complex |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 111-000 | 1 | 70 | MC58 | ST-32 (ET-5) |

| 011-000 | 1 | 9 | 4243 | Heterogeneous |

| 011-100 | 1 | 10 | NZ98/254 | Heterogeneous |

| Other v.1 | 1 | 11 | None | None |

|

| ||||

| 000-111 | 2 or 3 | 20 | 2996 | ST-35 complex |

| 000-110 | 2 | 24 | MD01158 | ST-41/44 (lineage III) |

| 000-001 | 2 or 3 | 12 | M1239 | ST-162 complex |

| 000-000 | 2 | 44 | RM1090 | Heterogeneous |

Pattern of fHBP monoclonal antibody (MAb) reactivity in the order JAR 1, 3, 5 (anti–variant [v.] 1 MAbs) and JAR 10, 11, 13 (anti-v.2 MAbs); 1 indicates reactivity, and 0 indicates no reactivity.

Among v.1 or among v.2 and v.3 isolates, respectively.

Multilocus sequence type (ST), per the Multi Locus Sequence Typing database (available at: http://www.mlst.net) [38]. “Predominant” implies that ≥50% of isolates had the specified ST.

fHBPs in the v.2 group have, on average, 85% aa identity with the v.3 group, whereas both of these groups have lower homology with fHBPs in the v.1 group (74 and 63%, respectively) [19]. There also is considerable cross-reactivity between v.2 and v.3 proteins but not between either of these and v.1 proteins (see below). Therefore, for the purpose of analysis of the fHBP phenotypes, the data from strains expressing v.2 or v.3 proteins were combined. Among the 50 fHBP v.2 or v.3 (v.2/v.3) isolates, phenotype 000–111 occurred in 20%; this group contained both v.2 and v.3 isolates, and these were predominantly in the ST-35 complex. Phenotype 000–110 occurred in 24% of the v.2/v.3 isolates, and these isolates were all v.2 and were predominantly lineage III. Phenotype 000–001, which is typified by the fHBP v.3 strain M1239, occurred in 12% of the v.2/v.3 isolates; this group contained both v.2 and v.3 isolates, and these were primarily in the ST-162 complex. Isolates with the phenotype 000-000, which do not react with any of the MAbs, comprised 44% of the v.2/v.3 isolates. All of these isolates expressed v.2 proteins. They had diverse STs and likely represent a genetically heterogeneous collection.

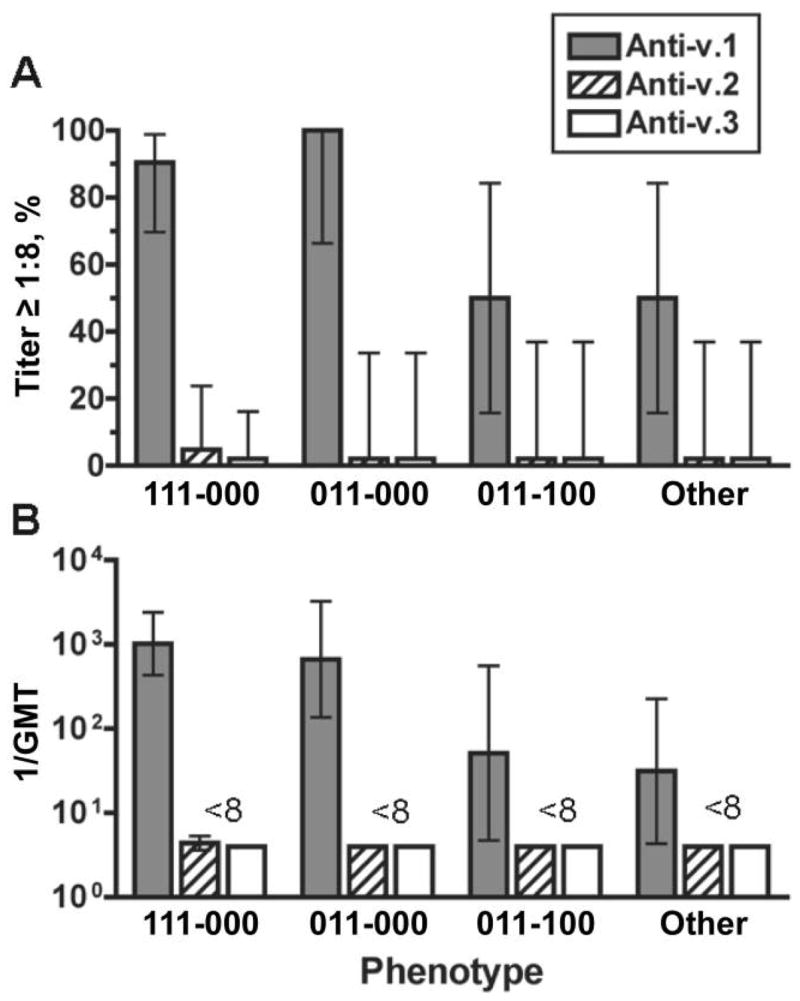

Bactericidal activity of anti-fHBP antisera

We measured the bactericidal activity of anti-fHBP v.1, v.2, and v.3 antisera on 84 of the isolates (48 v.1; 36 v.2; and 3 v.3). The anti-v.1 antiserum was bactericidal (titer ≥1:8, with human complement) against 77% of the v.1 isolates, whereas the anti-v.2 and anti-v.3. antisera killed only 2% and 0%, respectively, of the v.1 isolates. v.1 isolates representative of phenotypes 111-000 and 011-000 were particularly susceptible to the bactericidal activity of the anti-v.1 antiserum (91% and 100% of isolates, respectively), whereas only 50% of isolates with phenotype 011–100 or with other v.1 phenotypes were susceptible to killing by this serum (figure 3A). Together, these latter groups comprised 21% of v.1 isolates (table 2). The respective geometric mean titers (GMTs) exhibited similar patterns. The GMTs against v.1 isolates with either the 111-000 or 011-000 phenotype were ≥1: 600, whereas those against isolates with the remaining phenotypes were between 1:30 and 1:50 (figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Bactericidal activity of anti–factor H–binding protein (fHBP) antisera against fHBP variant (v.) 1 isolates, by fHBP phenotype (n =8–21 isolates/group). A, Percentage of strains giving a titer ≥1:8; B, Reciprocal geometric mean titers (GMTs). Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Shaded bars, anti–fHBP v.1 antiserum; hatched bars, anti–fHBP v.2; white bars, anti–fHBP v.3.

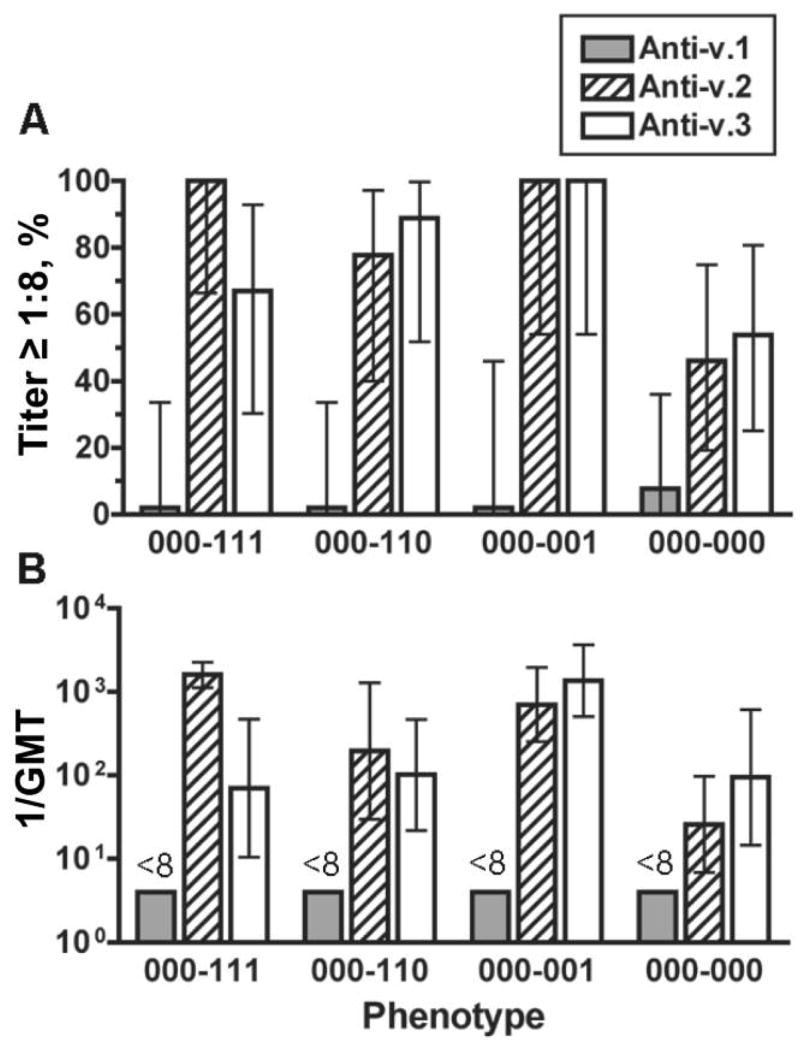

The majority (74%) of the v.2/v.3 isolates were susceptible to the bactericidal activity of the anti-v.2 antiserum. Of the isolates with a 000–111, 000–110, or 000–001 phenotype, 78%–100% were susceptible, whereas only 46% of the isolates with the 000-000 phenotype were susceptible (figure 4A). The GMTs of the anti-v.2 antiserum against isolates with 1 of the first 3 phenotypes were between 1:200 and 1:1500 and was 1:25 for the phenotype 000-000 (figure 4B). Most of the v.2/v.3 phenotypes showed similar results with the anti-v.3 antiserum. One exception was the 000–111 phenotype; of the isolates with this phenotype, 67% were susceptible to anti-v.3 antiserum (GMT, 1:70), versus 100% being susceptible to the anti-v.2 antiserum (GMT, 1:1500).

Figure 4.

Bactericidal activity of anti–factor H–binding protein (fHBP) antiserum against isolates expressing fHBP variant (v.) 2 or 3. Each fHBP phenotype had 6–13 isolates. A, Percentage of strains giving a titer ≥1:8; B, Reciprocal geometric mean titers (GMTs). Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Shaded bars, anti–fHBP v.1 antiserum; hatched bars, anti–fHBP v.2; white bars, anti–fHBP v.3.

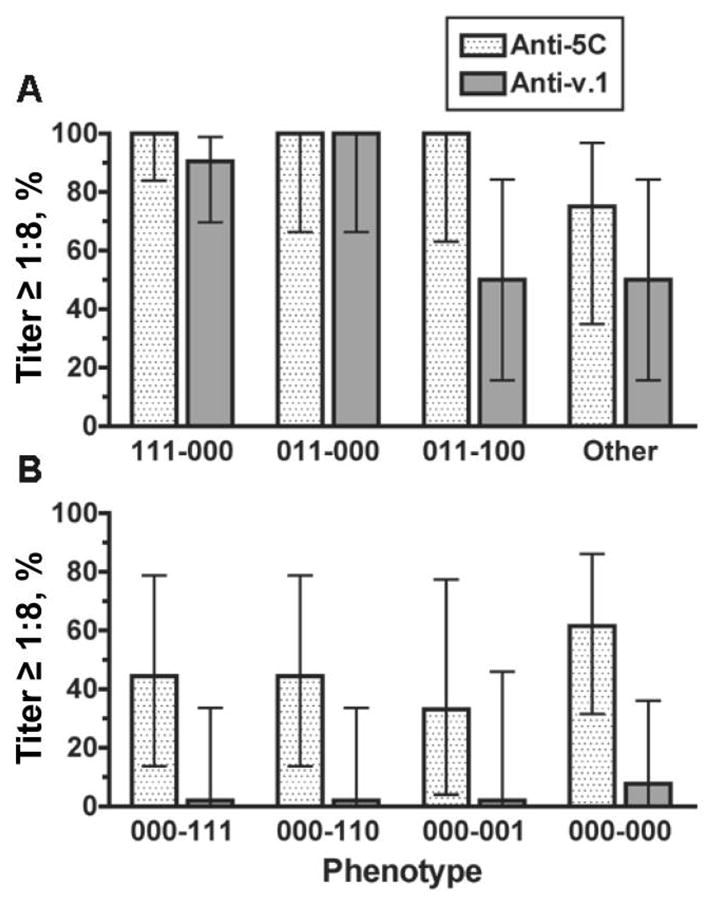

Bactericidal activity of anti-5C antiserum

Ninety-five percent of the 48 fHBP v.1 isolates tested were killed (titer ≥1: 8) by the polyclonal antiserum from mice immunized with the 5C vaccine (figure 5A), which contains fHBP v.1, compared with 56% of the v.2/v.3 isolates (figure 5B) (P <.001). Only 2 v.1 isolates were not killed by the anti-5C antiserum, and both were in the other-phenotype category. The GMTs of the anti-5C antiserum against v.1 isolates with different fHBP phenotypes ranged from 1:150 to 1:1500. The susceptibility of the v.2/v.3 isolates with different phenotypes ranged from 33% to62% (figure 5B), and no v.2/v.3 phenotype correlated strongly with susceptibility to antibodies elicited by the 5C vaccine. The respective GMTs of the v.2/v.3 isolates also were significantly lower (1:10–1:30) than those of the v.1 isolates, which may reflect the lack of bactericidal activity of anti-v.1 antibodies against v.2/v.3 isolates and the lower bactericidal activity of antibodies elicited by the other 4 antigens in the 5C vaccine.

Figure 5.

Percentage of isolates giving a titer ≥1:8 to anti–5-component (5C) vaccine antiserum. Also shown are data for the respective percentages susceptible to the anti–factor H–binding protein (fHBP) variant (v.) 1 antiserum tested alone. A, fHBP v.1 isolates; B, fHBP v.2 or v.3 isolates. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Stippled bars, anti-5C antiserum; shaded bars, anti-fHBP v.1.

Contribution of GNA 2132 and NadA antigens in the 5C vaccine

To assess the contributions of antigens other than fHBP v.1 in eliciting protective antibodies, we selected strains that were killed by the anti-5C antiserum but not by the anti-v.1 antiserum and tested their susceptibility to antisera prepared against 2 of the other antigens in the 5C vaccine, GNA 2132 [16, 20] and NadA [18]. Only 1 of 7 fHBP v.1 isolates tested was killed (titer ≥1:8) by the anti–GNA 2132 antiserum, compared with 8 of 10 fHBP v.2/v.3 isolates (P <.02, Fisher’s exact test). Five of the 10 isolates expressing fHBP v.2/v.3 had the nadA gene, and 1 of these was killed by the anti-NadA antiserum. Of the 7 v.1 isolates tested, the nadA gene was present in 3, and none were killed by the anti-NadA antiserum.

DISCUSSION

Among the 3 collections, 94% of isolates could be categorized into 7 patterns of anti-fHBP MAb reactivity, which we refer to as “fHBP phenotypes,” and some of the phenotypes predicted the susceptibility of an isolate to vaccine-induced serum bactericidal activity. For example, >90% of isolates with the 111-000 or 011-000 phenotype were highly susceptible to anti-v.1 antiserum, whereas only 50% of v.1 isolates with other phenotypes were susceptible (figure 3A). Similarly, 100% of v.2/v.3 isolates with the 000–111 or 000–001 phenotypes were susceptible to the bactericidal activity of the anti-v.2 antiserum, compared with 46% of v.2/v.3 isolates with the null phenotype (000-000). The most likely reasons for resistance of some of these isolates are genetic variability of the antigen and/or low expression of the protein [19].

Anti-5C complement–mediated killing of isolates expressing v.2 or v.3 fHBP appears to result from bactericidal anti-GNA 2132 antibodies and, to a lesser extent, anti-NadA antibodies. The anti-5C antibodies responsible for the killing of isolates expressing v.1 proteins that were not killed by anti-v.1 antiserum were not identified. Conceivably, these isolates might have been killed by antibodies against GNA 1030 or GNA 2091 or by a combination of antibodies elicited by the vaccine. However, the one combination that we tested (anti–fHBP v.1, anti-NadA, and anti–GNA 2132) had no bactericidal activity against these strains (data not shown).

NadA is known to play a role in the adhesion of N. meningitidis and invasion of human epithelial cells [18, 39]. Although nadA is present in the majority of the v.1 strains, the absence of nadA in some strains indicates that the presence of this molecule is not essential for pathogenesis. NadA can elicit serum bactericidal antibodies in mice against some NadA-positive strains [18], but its role in eliciting bactericidal antibodies by the 5C vaccine is difficult to define. First, the presence of the nadA gene segregates with the fHBP phenotype 111-000, which is the most common phenotype among v.1 isolates (70%; table 2), and the anti-v.1 antiserum alone had high bactericidal titers (>1:2000) against 90% of these isolates (figure 3). The main group of isolates for which anti-NadA antibodies might be important are the v.2/v.3 isolates that are nadA positive, but these constitute a small proportion of all isolates (6%). Nevertheless, antibodies against NadA can be bactericidal and may decrease colonization by strains expressing this protein. If true, the presence of NadA in the 5C vaccine could decrease the selection and emergence of mutant N. meningitidis strains that are resistant to the bactericidal activity of anti-v.1 antibodies.

The potential strain coverage for antibodies elicited by a vaccine containing single fHBP variants, multiple variants, or multiple antigens can be assessed by combining the prevalence of each phenotype with the proportion of isolates with each of the phenotypes susceptible to bactericidal activity. The combination of fHBP v.1 and v.2, or the 5C vaccine containing the v.1 fHBP, is projected to elicit bactericidal activity against 76% and 83% of strains, respectively. These are maximum projections of strain coverage based on serum bactericidal titers of 1: 8 or higher in mouse antisera assayed with human complement.

Recently, the 5C vaccine was investigated in a phase 1 trial conducted in adults [22]. After a third injection, >90% of the immunized subjects developed serum bactericidal titers of ≥1: 4 against at least 1 group B strain representative of different hypervirulent lineages (for example, ST-32 [ET-5], ST-41/44 [lineage III], or ST-8 [cluster A4]). The presence of different vaccine-antigen variants and/or their expression does not always correlate with ST, and the percentages of immunized subjects with serum bactericidal activity against other test strains, some with STs identical to those of susceptible isolates, were lower. Nonetheless, this multicomponent vaccine is the first recombinant-protein vaccine to elicit serum bactericidal antibodies in humans against genetically diverse group B strains and, thus, appears to be promising. The data also demonstrate the power of the “reverse vaccinology” approach [40, 41] for the discovery of promising antigens.

Acknowledgments

We thank Will Probert (Chief of Enterics and Special Pathogens Section, California Department of Health Services, Richmond), for providing the group B isolates from patients hospitalized in California; Rino Rappuoli and Mariagrazia Pizza (Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics, Siena, Italy), for providing the recombinant proteins used for immunization; Edward Mason (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas), for providing the isolates from the multicenter isolates; Mary O’Leary and Melina Lenser (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), for multilocus sequencing typing and outer membrane protein genotyping; and Gregory Moe (Children’s Hospital Oakland Research Institute, Oakland, California), for critical reading of the manuscript. Maggie Ching, Ray Chen, Carlos Grenier, Amy Huang, Monica Kaitz, and Laila Williams provided expert technical assistance.

Financial support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (NIH; grants R01 AI46464, R01 AI58122, and R21 AI61533 to D.M.G. and Research Career Award K24 AI52788 to L.H.H.); Sanofi Pasteur (grant to S.L.K. to support the multicenter surveillance study). The investigation was conducted in a facility constructed with support from the National Center for Research Resources, NIH (Research Facilities Improvement Program grant CO6 RR16226).

Footnotes

Presented in part: 15th International Pathogenic Neisseria Conference (abstract S09.3), Cairns, Australia, 10–15 September 2006.

Potential conflicts of interest: D.M.G.’s laboratory at Children’s Hospital Oakland Research Institute has research grants from Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics and from Sanofi Pasteur. D.M.G. also holds a paid consultancy from Novartis. L.H.H. receives research grant support from Sanofi Pasteur and serves as a paid consultant to Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, and Novartis; he also receives speaking honoraria from Sanofi Pasteur. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Campbell JD, Edelman R, King JC, Jr, Papa T, Ryall R, Rennels MB. Safety, reactogenicity, and immunogenicity of a tetravalent meningococcal polysaccharide–diphtheria toxoid conjugate vaccine given to healthy adults. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:1848–51. doi: 10.1086/345763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keyserling H, Papa T, Koranyi K, et al. Safety, immunogenicity, and immune memory of a novel meningococcal (groups A, C, Y, and W-135) polysaccharide diphtheria toxoid conjugate vaccine (MCV-4) in healthy adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:907–13. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.10.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pichichero M, Casey J, Blatter M, et al. Comparative trial of the safety and immunogenicity of quadrivalent (A, C, Y, W-135) meningococcal polysaccharide-diphtheria conjugate vaccine versus quadrivalent polysaccharide vaccine in two- to ten-year-old children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:57–62. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000148928.10057.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bilukha OO, Rosenstein N. Prevention and control of meningococcal disease: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54:1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cartwright K, Noah N, Peltola H. Meningococcal disease in Europe: epidemiology, mortality, and prevention with conjugate vaccines. Vaccine; Report of a European advisory board meeting Vienna; Austria. 6–8 October, 2000; 2001. pp. 4347–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finne J, Bitter-Suermann D, Goridis C, Finne U. An IgG monoclonal antibody to group B meningococci cross-reacts with developmentally regulated polysialic acid units of glycoproteins in neural and extra-neural tissues. J Immunol. 1987;138:4402–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devi SJ, Robbins JB, Schneerson R. Antibodies to poly[(2→8)-alpha-N-acetylneuraminic acid] and poly[(2→9)-alpha-N-acetylneuraminic acid] are elicited by immunization of mice with Escherichia coli K92 conjugates: potential vaccines for groups B and C meningococci and E. coli K1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7175–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azmi FH, Lucas AH, Spiegelberg HL, Granoff DM. Human immunoglobulin M paraproteins cross-reactive with Neisseria meningitidis group B polysaccharide and fetal brain. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1906–13. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1906-1913.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenqvist E, Hoiby EA, Wedege E, et al. Human antibody responses to meningococcal outer membrane antigens after three doses of the Norwegian group B meningococcal vaccine. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4642–52. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.12.4642-4652.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tappero JW, Lagos R, Ballesteros AM, et al. Immunogenicity of 2 serogroup B outer-membrane protein meningococcal vaccines: a randomized controlled trial in Chile. JAMA. 1999;281:1520–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.16.1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morley SL, Cole MJ, Ison CA, et al. Immunogenicity of a serogroup B meningococcal vaccine against multiple Neisseria meningitidis strains in infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001;20:1054–61. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200111000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsai CM, Frasch CE, Mocca LF. Five structural classes of major outer membrane proteins in Neisseria meningitidis. J Bacteriol. 1981;146:69–78. doi: 10.1128/jb.146.1.69-78.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tommassen J, Vermeij P, Struyve M, Benz R, Poolman JT. Isolation of Neisseria meningitidis mutants deficient in class 1 (porA) and class 3 (porB) outer membrane proteins. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1355–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.5.1355-1359.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Ley P, van der Biezen J, Poolman JT. Construction of Neisseria meningitidis strains carrying multiple chromosomal copies of the porA gene for use in the production of a multivalent outer membrane vesicle vaccine. Vaccine. 1995;13:401–7. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)98264-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin D, Cadieux N, Hamel J, Brodeur BR. Highly conserved Neisseria meningitidis surface protein confers protection against experimental infection. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1173–83. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.7.1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pizza M, Scarlato V, Masignani V, et al. Identification of vaccine candidates against serogroup B meningococcus by whole-genome sequencing. Science. 2000;287:1816–20. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grifantini R, Bartolini E, Muzzi A, et al. Previously unrecognized vaccine candidates against group B meningococcus identified by DNA microarrays. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:914–21. doi: 10.1038/nbt728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Comanducci M, Bambini S, Brunelli B, et al. NadA, a novel vaccine candidate of Neisseria meningitidis. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1445–54. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masignani V, Comanducci M, Giuliani MM, et al. Vaccination against Neisseria meningitidis using three variants of the lipoprotein GNA1870. J Exp Med. 2003;197:789–99. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Welsch JA, Moe GR, Rossi R, Adu-Bobie J, Rappuoli R, Granoff DM. Antibody to genome-derived neisserial antigen 2132, a Neisseria meningitidis candidate vaccine, confers protection against bacteremia in the absence of complement-mediated bactericidal activity. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:1730–40. doi: 10.1086/379375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giuliani MM, Adu-Bobie J, Comanducci M, et al. A universal vaccine for serogroup B meningococcus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:10834–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603940103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rappuoli R. A universal vaccine for serogroup B meningococcus [abstract S10.2]. Program and abstracts of the International Pathogenic Neisseria Conference; Cairns, Australia. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fletcher LD, Bernfield L, Barniak V, et al. Vaccine potential of the Neisseria meningitidis 2086 lipoprotein. Infect Immun. 2004;72:2088–100. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.4.2088-2100.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Madico G, Welsch JA, Lewis LA, et al. The meningococcal vaccine candidate GNA1870 binds the complement regulatory protein factor H and enhances serum resistance. J Immunol. 2006;177:501–10. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whaley K, Ruddy S. Modulation of the alternative complement pathways by beta 1 H globulin. J Exp Med. 1976;144:1147–63. doi: 10.1084/jem.144.5.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pangburn MK, Schreiber RD, Muller-Eberhard HJ. Human complement C3b inactivator: isolation, characterization, and demonstration of an absolute requirement for the serum protein beta1H for cleavage of C3b and C4b in solution. J Exp Med. 1977;146:257–70. doi: 10.1084/jem.146.1.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weiler JM, Daha MR, Austen KF, Fearon DT. Control of the amplification convertase of complement by the plasma protein beta1H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:3268–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.9.3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zollinger WD, Mandrell RE. Importance of complement source in bactericidal activity of human antibody and murine monoclonal antibody to meningococcal group B polysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1983;40:257–64. doi: 10.1128/iai.40.1.257-264.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santos GF, Deck RR, Donnelly J, Blackwelder W, Granoff DM. Importance of complement source in measuring meningococcal bactericidal titers. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2001;8:616–23. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.8.3.616-623.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneider MC, Exley RM, Chan H, et al. Functional significance of factor H binding to Neisseria meningitidis. J Immunol. 2006;176:7566–75. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ngampasutadol J, Welsch JA, Lewis LA, et al. A novel interaction between factor H SCR 6 and the meningococcal vaccine candidate GNA1870: implications for meningococcal pathogenesis and vaccine development [abstract 6.2.05]. Program and abstracts of the International Pathogenic Neisseria Conference; Cairns, Australia. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harrison LH, Jolley KA, Shutt KA, et al. Antigenic shift and increased incidence of meningococcal disease. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:1266–74. doi: 10.1086/501371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaplan SL, Schutze GE, Leake JA, et al. Multicenter surveillance of invasive meningococcal infections in children. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e979–84. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beernink PT, Leipus A, Granoff DM. Rapid genetic grouping of factor H-binding protein (genome-derived neisserial antigen 1870), a promising group B meningococcal vaccine candidate. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2006;13:758–63. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00097-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Welsch JA, Rossi R, Comanducci M, Granoff DM. Protective activity of monoclonal antibodies to genome-derived neisserial antigen 1870, a Neisseria meningitidis candidate vaccine. J Immunol. 2004;172:5606–15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mandrell RE, Azmi FH, Granoff DM. Complement-mediated bactericidal activity of human antibodies to poly α2→8 N-acetylneuraminic acid, the capsular polysaccharide of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:1279–89. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.5.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moe GR, Tan S, Granoff DM. Differences in surface expression of NspA among Neisseria meningitidis group B strains. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5664–75. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.5664-5675.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maiden MC, Bygraves JA, Feil E, et al. Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3140–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Capecchi B, Adu-Bobie J, Di Marcello F, et al. Neisseria meningitidis NadA is a new invasin which promotes bacterial adhesion to and penetration into human epithelial cells. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:687–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rappuoli R. Reverse vaccinology. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2000;3:445–50. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(00)00119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rappuoli R, Covacci A. Reverse vaccinology and genomics. Science. 2003;302:602. doi: 10.1126/science.1092329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]