Abstract

The major human tRNALys isoacceptors,  and

and  , are selectively packaged into human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) during assembly, where

, are selectively packaged into human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) during assembly, where  acts as a primer for reverse transcription. Lysyl-tRNA synthetase (LysRS) is also incorporated into HIV-1, independently of tRNALys, via its interaction with Gag, and is a strong candidate for being the signal that specifically targets tRNALys for viral incorporation. We have transfected 293T cells with HIV-1 proviral DNA and short interfering RNA (siRNA) specific for LysRS to study the effect of diminished cellular LysRS upon tRNALys packaging,

acts as a primer for reverse transcription. Lysyl-tRNA synthetase (LysRS) is also incorporated into HIV-1, independently of tRNALys, via its interaction with Gag, and is a strong candidate for being the signal that specifically targets tRNALys for viral incorporation. We have transfected 293T cells with HIV-1 proviral DNA and short interfering RNA (siRNA) specific for LysRS to study the effect of diminished cellular LysRS upon tRNALys packaging,  annealing to viral genomic RNA, and viral production and infectivity. At early time points after siRNA transfection, an 80% inhibition of LysRS incorporation into viruses reflects an 80% reduction of newly synthesized LysRS, rather than a more limited 20 to 25% decrease in the concentration of total cell LysRS, indicating that newly synthesized LysRS in the cell may be the main source of viral LysRS. Viruses produced from cells transfected with siRNA show reduced tRNALys packaging, reduced

annealing to viral genomic RNA, and viral production and infectivity. At early time points after siRNA transfection, an 80% inhibition of LysRS incorporation into viruses reflects an 80% reduction of newly synthesized LysRS, rather than a more limited 20 to 25% decrease in the concentration of total cell LysRS, indicating that newly synthesized LysRS in the cell may be the main source of viral LysRS. Viruses produced from cells transfected with siRNA show reduced tRNALys packaging, reduced  annealing to viral RNA, and reduced viral infectivity.

annealing to viral RNA, and reduced viral infectivity.

In human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1),  serves as the primer tRNA for the reverse transcriptase-catalyzed synthesis of minus-strand strong-stop cDNA (18). During HIV-1 assembly, the major tRNALys isoacceptors,

serves as the primer tRNA for the reverse transcriptase-catalyzed synthesis of minus-strand strong-stop cDNA (18). During HIV-1 assembly, the major tRNALys isoacceptors,  and

and  , are selectively packaged into the virion (14). While the viral precursor proteins Gag and Gag-Pol are known to be involved in tRNALys incorporation (15, 20, 22), the identity of viral or host cell factors that target the tRNALys isoacceptors for interaction with these proteins is less clear. Recently, we have reported that a major tRNALys binding protein, human lysyl tRNA synthetase (LysRS) is also selectively packaged into the virion (4). This observation makes LysRS a prime candidate for facilitating viral packaging of tRNALys, possibly through its own interaction with viral proteins. The incorporation of LysRS is specific. Published work (3, 4) indicates that HIV-1 does not contain isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase (IleRS), prolyl-tRNA synthetase (ProRS), or tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase (TrpRS). Unpublished work from our laboratory also indicates the additional absence in HIV-1 of arginyl-tRNA synthetase (ArgRS), glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase (GlnRS), methionyl-tRNA-synthetase (MetRS), and tyrosinyl-tRNA synthetase (TyrRS). HIV-1 contains, on average, approximately 20 to 25 molecules of LysRS/virion (3), similar to the average number of tRNALys molecules per virion (11).

, are selectively packaged into the virion (14). While the viral precursor proteins Gag and Gag-Pol are known to be involved in tRNALys incorporation (15, 20, 22), the identity of viral or host cell factors that target the tRNALys isoacceptors for interaction with these proteins is less clear. Recently, we have reported that a major tRNALys binding protein, human lysyl tRNA synthetase (LysRS) is also selectively packaged into the virion (4). This observation makes LysRS a prime candidate for facilitating viral packaging of tRNALys, possibly through its own interaction with viral proteins. The incorporation of LysRS is specific. Published work (3, 4) indicates that HIV-1 does not contain isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase (IleRS), prolyl-tRNA synthetase (ProRS), or tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase (TrpRS). Unpublished work from our laboratory also indicates the additional absence in HIV-1 of arginyl-tRNA synthetase (ArgRS), glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase (GlnRS), methionyl-tRNA-synthetase (MetRS), and tyrosinyl-tRNA synthetase (TyrRS). HIV-1 contains, on average, approximately 20 to 25 molecules of LysRS/virion (3), similar to the average number of tRNALys molecules per virion (11).

Several additional pieces of evidence support a role for LysRS in targeting tRNALys for viral incorporation. First, the incorporation of LysRS into viruses occurs independently of tRNALys incorporation. Thus, LysRS is packaged into Gag virus-like particles (VLPs) composed only of Gag (4), which do not selectively package tRNALys due to the absence of Gag-Pol (20). Second, the incorporation of wild-type and mutant  variants depends upon the ability of the tRNA to bind to LysRS (13). Third, the overexpression of wild-type LysRS in cells cotransfected with plasmids coding for both LysRS and HIV-1 proviral DNA results in an increase in the incorporation of both total LysRS (endogenous and exogenous) and tRNALys into the viruses (10).

variants depends upon the ability of the tRNA to bind to LysRS (13). Third, the overexpression of wild-type LysRS in cells cotransfected with plasmids coding for both LysRS and HIV-1 proviral DNA results in an increase in the incorporation of both total LysRS (endogenous and exogenous) and tRNALys into the viruses (10).

In this report, we further test the premise that LysRS is required for selective packaging of tRNALys into HIV-1 through the selective degradation of LysRS mRNA using short interfering RNA (siRNA). Studies of the silencing of genes in both plants and animals have revealed a wide-spread mechanism for the posttranscriptional suppression of gene expression by double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) through a process termed RNA interference (RNAi) (for recent reviews, see references 23, 28, 31, and 32). The RNAi mechanism has only partially been elucidated. The dsRNA is processed to 21- to 25-nucleotide (nt) siRNA with 2-nt 3′-overhangs by the RNase III-like protein Dicer in the initiating step of RNAi (1). These cleavage products are subsequently utilized by the RNA-induced silencing complex for the recognition and cleavage of the corresponding mRNA. The protein composition of RNA-induced silencing complex is only now being elucidated, and both a helicase (possibly to unwind the siRNA) and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase have been identified. Transfection of siRNAs into plants, Caenorhabditis elegans, and Drosophila melanogaster has been used successfully to silence many specific genes. However, in mammals, long dsRNAs result in nonspecific suppression of gene expression at the translational level, in part through activation of dsRNA-dependent protein kinase, whose activation results in the phosphorylation and inactivation of an important translation initiation factor, eIF2a, thereby stopping protein synthesis (30). Nevertheless, it has been discovered that siRNAs shorter than 30 nt do not activate this pathway, nor other dsRNA-induced nonspecific suppression pathways (7), and as a result, siRNAs have been used successfully to specifically silence a number of mammalian genes.

Several studies have used siRNA to inhibit HIV-1 replication in cell culture. These studies used siRNA to target diverse viral genes such as those coding for vif, nef, tat, rev, and p24 (6, 12, 17, 24), and the cellular chemokine coreceptor CCR5 (26). In this report, we have cotransfected 293T cells with HIV-1 proviral DNA and siRNA specific for LysRS mRNA. We find that the depletion of newly synthesized LysRS results in the depletion of viral LysRS and tRNALys, which is accompanied by an inhibition of  annealing to viral RNA and decreased viral infectivity.

annealing to viral RNA and decreased viral infectivity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids, cell culture, and viral isolation.

SVC21.BH10 is a simian virus 40-based vector, which contains full-length HIV-1 proviral DNA, and was a gift from E. Cohen, University of Montreal. HEK-293T cells were grown in complete Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) plus 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 U of penicillin, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml. The HeLa-CD4-LTR-β-gal (MAGI) cell line was cultured in complete DMEM plus 10% FCS, penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), neomycin (200 μg/ml), and hygromycin (100 μg/ml). The MT-2 cell line was maintained in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FCS, 100 U of penicillin, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml.

For the production of viruses, HEK-293T cells were transfected with SVC21.BH10 using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Culture supernatant was collected at the different time points referred to in the text. Viruses were purified as previously described (10).

RNA isolation and analysis.

Total cellular or viral RNA was extracted from cell or viral pellets by the guanidinium isothiocyanate procedure (5), and dissolved in 5 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.5. Hybridization to dot blots of cellular or viral RNA was carried out with DNA probes complementary to  and

and  (14), genomic RNA (2), and β-actin mRNA (DNA probe from Ambion, Austin, Tex.).

(14), genomic RNA (2), and β-actin mRNA (DNA probe from Ambion, Austin, Tex.).

To measure the amount of  annealed to genomic RNA,

annealed to genomic RNA,  -primed initiation of reverse transcription was measured using total viral RNA as the source of primer tRNA/template in an in vitro HIV-1 reverse transcription reaction, as previously described (11). The sequence of the first six deoxynucleoside triphosphates incorporated is CTGCTA, and in the presence of dCTP, dGTP, dTTP, and ddATP,

-primed initiation of reverse transcription was measured using total viral RNA as the source of primer tRNA/template in an in vitro HIV-1 reverse transcription reaction, as previously described (11). The sequence of the first six deoxynucleoside triphosphates incorporated is CTGCTA, and in the presence of dCTP, dGTP, dTTP, and ddATP,  is extended by 6 bases, and this product can be resolved by one-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (1D PAGE) and quantitated by phosphorimaging.

is extended by 6 bases, and this product can be resolved by one-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (1D PAGE) and quantitated by phosphorimaging.

Preparation of siRNA.

siRNA to LysRS mRNA with the following sense and antisense sequences were used: LysRS T1 (122-142), 5′-GAGCTCAGTGAGAAACAGCTT-3′(sense), 5′-GCUGUUUCUCACUGAGCUCUU-3′(antisense); LysRS T2 (574-594), 5′-GAAGGGUGAGCUGAGCAUCUU-3′ (sense), 5′-GAUGCUCAGCUCACCCUUCUU-3′ (antisense); LysRS T3 (1219-1239), 5′-GCUGCCAGAAACGAACCUCUU-3′ (sense), 5′-GAGGUUCGUUUCUGGCAGCUU-3′ (antisense); LysRS T4 (1235-1255), 5′-GGAGAAUGUAGCAACCACUUU-3′ (sense), 5′-AGUGGUUGCUACAUUCUCCUU-3′ (antisense). siRNA to the control luciferase mRNA (8) with the following sense and antisense sequence were used: cont., 5′-CUUACGCUGAGUACUUCGAUU-3′ (sense), 5′-UCGAAGUACUCAGCGUAAGUU-3′ (antisense). All siRNAs were constructed by the Silence siRNA construction kit from Ambion, using the protocol according to the manufacturer's instructions. The constructed duplex siRNAs were stored at −80°C until they were prepared for transfection.

HIV-1 proviral DNA and siRNA transfection.

At 24 h before transfection, HEK-293T cells were trypsinized and plated in six-well plates at 105 cells per well in 2 ml of DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS. The cells were incubated at 37°C in a CO2 incubator until 60 to 80% confluent. Transfection of HEK-293T cells with HIV-1 proviral DNA used the Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen), following the protocol set by the manufacturer. For transfection of HEK-293T cells with siRNA, cationic lipid complexes were prepared by incubating 50 pmol of indicated siRNA with 5 μl of DMRIE-C reagent (Invitrogen) in 200 μl of DMEM for 20 min and were then added to the wells in a final volume of 0.75 ml with serum-free DMEM. Four hours later, 0.75 ml of DMEM containing 20% FCS was added to the cells. Cells were then cultured and assayed for the appropriate activity at the time-points post transfection indicated in the text. For cells transfected with HIV-1 proviral DNA and siRNA, cells were transfected with HIV-1 proviral DNA in DMEM plus 10% FCS 24 h prior to siRNA transfection, which was done after replacing DMEM plus 10% FCS with serum-free DMEM.

Metabolic labeling and radioimmunoprecipitation analysis.

HEK-293T cells transfected with siRNA were labeled with [35S]Met-[35S]Cys at specific time points post-siRNA transfection, as described in the text. At each time point, cells were washed twice with 37°C prewarmed serum-free DMEM missing amino acids methionine and cysteine and were then incubated for 20 min at 37°C in this medium. Cells were then cultured at 37°C for 60 min in this medium containing [35S]methionine (50 μCi/ml) and [35S]cysteine (50 μCi/ml). For cells labeled at the time of siRNA transfection, labeling was done in the serum-free medium used for siRNA transfection, which eliminated the washing required to remove DMEM plus 10% FCS required for cells cultured for longer time periods post-siRNA transfection. The radiolabeled medium was then removed, and the cells were washed twice with DMEM, and cultured for 1 h in DMEM. Cells were washed twice with cold PBS and lysed with RIPA buffer. LysRS was then immunoprecipitated from equal amounts of postnuclear cell lysate by incubating with anti-LysRS antisera at 4°C at for 1 h. Protein A-Sepharose CL-4B (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) beads were then added to the antibody-containing cell lysate, and incubated for a further 1 h at 4°C to allow the beads to bind to the antigen-antibody complexes. The beads were washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline buffer containing 1% Triton X-100, and the bound proteins were heated in gel loading buffer and resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-PAGE analysis and autoradiography.

Western blot analysis.

Cells or viruses were lysed in RIPA buffer (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 1 mM EDTA), and equal amounts of cell or viral lysates were separated by SDS-10% PAGE, followed by blotting onto nitrocellulose membranes (Gelman Science). Western blots were probed with either rabbit LysRS antiserum (1:15,000 dilution), a monoclonal mouse antibody against β-actin (1:5,000 dilution σ), or a monoclonal mouse antibody against viral capsid (1:5,000 dilution [NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program]). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies used were either anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (1:5,000 dilution) or anti-mouse immunoglobulin (1:5,000 dilution) [Amersham Biosciences]. Protein bands were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences, Inc., Boston, Mass.), and quantitated using UN-SCAN-IT gel automated digitizing system.

HIV-1 infectivity and MAGI assay.

Viruses produced from HEK-293T cells transfected with siRNA and HIV-1 proviral DNA were harvested as previously described (10). Measurement of single-round infectivity used the MAGI assay (10, 16). In the MAGI assay, CD4-positive HeLa cells containing the β-galactosidase gene fused to the HIV-1 long terminal repeat (LTR) are infected with equal amounts of HIV-1 (equal amounts of p24). Infected cells will have the β-galactosidase gene expressed, and such cells can be detected using an appropriate substrate for the enzyme, such as X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside), whose metabolism will turn the cells blue. The number of blue cells is a measure of viral infectivity. Viral replication in MAGI cells or in MT-2 cells was determined by measuring the release of capsid protein into media over time by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (19).

RESULTS

Reduction of newly synthesized and total cellular LysRS by siRNA.

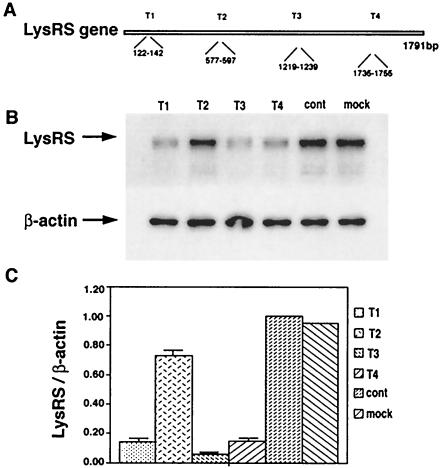

siRNAs were designed to be complementary to different nucleotide sequences found in human LysRS mRNA. The different siRNAs, labeled T1-T4, and their target sequences, are shown in Fig. 1A. Each siRNA was transfected into 293T cells as described in Materials and Methods, and 48 h later, Western blots of cell lysates were probed with either anti-LysRS or anti-β-actin. These results are shown in Fig. 1B and represented graphically in Fig. 1C, where the LysRS/β-actin ratio for control cells (cells transfected with luciferase siRNA) is given a value of 1.00. Mock cells were not transfected with any siRNA. It can be seen that 48 h posttransfection, maximum reduction of cytoplasmic LysRS to 10 to 20% control values is obtained for T1, T3, and T4.

FIG. 1.

Reduction of total cellular LysRS in 293T cells by siRNA. siRNAs were designed to be complementary to different nucleotide sequences found in human LysRS mRNA. (A) The different siRNAs, labeled T1-T4, and their target nucleotide sequences in LysRS mRNA, are shown. (B) Each RNA was transfected into 293T cells as described in Materials and Methods, and 48 h later, cell lysates were analyzed by Western blots probed with either anti-LysRS or anti-β-actin. (C) Bands were quantitated, and the LysRS/β-actin ratio is shown graphically, normalized to the ratio found for control cells (transfected with luciferase siRNA). Mock cells were not transfected with any siRNA. The bar graphs represent the means of experiments performed three times or more, and the error bars represent standard deviations.

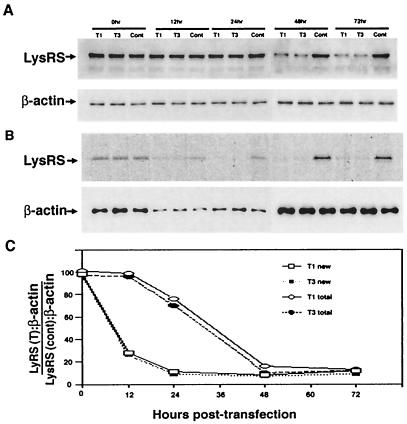

Since siRNA probably targets LysRS mRNA for degradation, we next compared the decay rate of total cellular LysRS with the inhibition of production of newly synthesized LysRS, in cells transfected with siRNA. 293T cells were transfected with either T1, T3, or luciferase siRNA. Aliquots of cells were removed at different times, and lysed in RIPA buffer. Figure 2A shows Western blots of cell lysates probed with either anti-LysRS or anti-β-actin. The bands in Fig. 2A were quantitated, and the LysRS:β-actin ratio at each time point, relative to that found for control cells at the same time point, was plotted for the cells exposed to the T1 and T3 siRNAs (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

Decay of total cellular LysRS compared with the inhibition of new synthesis of LysRS, in 293T cells transfected with T1 or T3 siRNA. (A) Decay of total cellular LysRS. Aliquots of cells were removed at different times, and Western blots of lysates of cells transfected with T1 siRNA, T3 siRNA, or luciferase siRNA (cont.) were probed with either anti-LysRS or anti-β-actin. (B) Production of newly synthesized LysRS. Cells transfected with siRNA were labeled at various times for 1 h with [35S]Cys-[35S]Met. LysRS was immunoprecipitated from the labeled cell lysate with anti-LysRS, and the immunoprecipitate was electrophoresed using SDS-10% PAGE. The bands were detected by autoradioagraphy. Total β-actin in each lysate was determined by probing Western blots of cell lysates with anti-β-actin. (C) The electrophoretic bands shown in panels A and B were quantitated, and the total or newly synthesized LysRS (T):β-actin/LysRS (cont.):β-actin ratio at each time point was graphed for cells transfected with the T1 and T3 siRNAs. T = T1 or T3.

To study the production of newly synthesized LysRS at various times after transfection with siRNA, a plate of cells was washed in serum-free DMEM missing amino acids methionine and cysteine and then was labeled in this medium for 1 h with [35S]Cys-[35S]Met. The labeled cells were then washed with nonlabeled medium, and lysed in RIPA buffer. For cells labeled at the time of siRNA transfection, both siRNA transfection and labeling were done at the same time in the same serum-free DMEM missing amino-acids methionine and cysteine. Cells labeled at zero time are thus missing the extra washes at later time points to remove culture medium, which accounts for the fact that the radioactive signals per plate of cells is lower at early time points than the zero time point due to loss of cells from the plate (Fig. 2B), but increase at later time points. This is reflected in the Western blots of β-actin shown in Fig. 2B, which reflects cell number per plate. To obtain the same ratios for newly synthesized LysRS, LysRS was immunoprecipitated from the labeled cell lysate with anti-LysRS, and the immunoprecipitate was resolved by 1D PAGE, blotted, and the audioradiographic bands (Fig. 2B) quantitated. By use of phosphorimaging, the newly synthesized LysRS: total β-actin ratio, relative to the similar ratio of the control cells at each time point, was plotted for cells transfected with the T1 and T3 siRNAs (Fig. 2C).

The results graphed in Fig. 2C indicate a much more rapid decrease in the new synthesis of LysRS than in the decay of total cellular LysRS. These reductions are both incomplete, leveling off at 10 to 20% of controls. This is probably due to the fact that the siRNA cannot completely degrade all LysRS mRNA and some new LysRS will be synthesized. The decay rate of total LysRS, estimated from the linear region of decay shown in Fig. 2C, indicates a half-life of 20 h. This value is approximate due to the probable incomplete removal of all the LysRS mRNA.

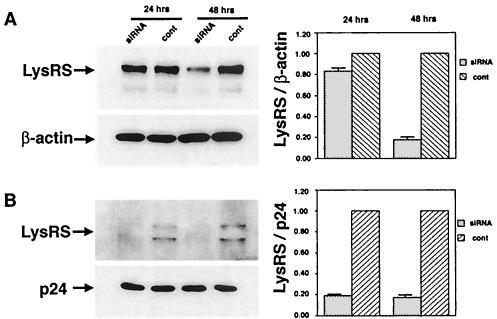

The decrease in viral LysRS reflects the decrease in production of newly synthesized cellular LysRS.

We next examined the effect of the decay of cellular LysRS concentrations upon the incorporation of LysRS into HIV-1 produced from these cells. 293T cells were transfected with HIV-1 proviral DNA 24 h prior to transfection of cells with either T3 or luciferase siRNA or control. Cells and viruses were harvested 24 and 48 h after transfection with siRNA. At 12 h prior to harvesting, medium was removed, fresh media added, and only viruses produced in the next 12 h were collected. Figure 3A shows Western blots of the cell lysates probed with anti-LysRS or anti-β-actin and Fig. 3B shows Western blots of the viral lysates probed with either anti-LysRS or anti-p24. The electrophoretic bands were quantitated, and the cellular LysRS/β-actin, or the viral LysRS:p24 ratios are shown graphically in the right part of the panels, normalized to the ratios obtained for control cells and the viruses produced from them. As was previously shown in Fig. 2, there is a small 20% decrease in total cellular LysRS 24 h after exposure to T3 siRNA, and an 80% decrease in cellular LysRS 48 h after exposure to T3 siRNA. On the other hand, the concentration of viral LysRS decreases 80% after 24 h exposure to T3 siRNA. These results suggest that the source of viral LysRS in the cell is newly synthesized LysRS, which, as shown in Fig. 2, also drops 80 to 90% 24 h after exposure of cells to T3 siRNA.

FIG. 3.

Inhibition of the incorporation of LysRS into viruses produced from cells transfected with T3 siRNA. 293T cells were transfected with HIV-1 proviral DNA 24 h prior to transfection of cells with either T3 siRNA or luciferase siRNA (cont.). Cells and viruses were harvested 24 and 48 h after transfection with siRNA. Twelve hours prior to harvesting, media were removed, fresh media added, and only viruses produced in the next 12 h were collected. (A) Western blots of the cell lysates probed with anti-LysRS or anti-β-actin. (B) Western blots of the viral lysates probed with either anti-LysRS or anti-p24. The electrophoretic bands in panels A and B were quantitated, and the cellular LysRS/β-actin, or the viral LysRS:p24 ratios, from T3 siRNA-transfected cells, normalized to control cells or virus produced from them, are shown graphically in the right part of the panels A or B, respectively. The bar graphs represent the means of experiments performed three times or more, and the error bars represent standard deviations.

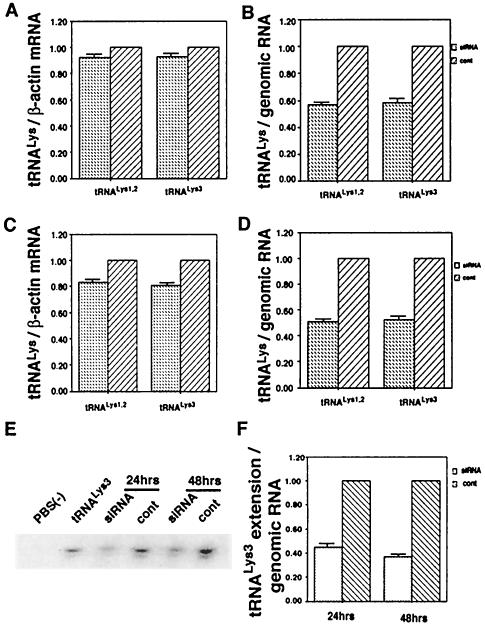

Effect of T3 siRNA on tRNALys packaging,  annealing to viral RNA, and viral infectivity.

annealing to viral RNA, and viral infectivity.

Following the protocol described in the preceding section for studying cell and viral LysRS, 293T cells were transfected with HIV-1 proviral DNA and siRNA, and cells and virus were collected. Cellular and viral RNA were isolated. Figure 4 shows the effect of these transfections upon tRNALys concentrations in the cytoplasm (Fig. 4A and C) and in the virions (Fig. 4B and D) produced from these cells. Dot blot hybridizations of cellular RNA used probes specific for β-actin mRNA, and  or

or  (10), to determine the

(10), to determine the  or

or  :β-actin mRNA ratios in cellular RNA at 24 (Fig. 4A) and 48 h (Fig. 4C), respectively, post-siRNA transfection. Dot blot hybridizations of viral RNA used probes specific for viral genomic RNA, and

:β-actin mRNA ratios in cellular RNA at 24 (Fig. 4A) and 48 h (Fig. 4C), respectively, post-siRNA transfection. Dot blot hybridizations of viral RNA used probes specific for viral genomic RNA, and  or

or  , to determine the

, to determine the  or

or  viral genomic RNA ratios in viral RNA at 24 h (Fig. 4B) and 48 h (Fig. 4D), respectively. Ratios for cells transfected with T3 siRNA were normalized to values found for the control cells transfected with luciferase siRNA. At 24 h after transfection by T3 siRNA, there is a 10% reduction in the cytoplasmic concentrations of tRNALys isoacceptors, while in the virions tRNALys isoacceptor concentrations are reduced approximately 45%. At 48 h posttransfection with T3 siRNA, cytoplasmic concentration of tRNALys isoacceptors have decreased 20%, while the concentration of their viral counterparts have decreased approximately 50%.

viral genomic RNA ratios in viral RNA at 24 h (Fig. 4B) and 48 h (Fig. 4D), respectively. Ratios for cells transfected with T3 siRNA were normalized to values found for the control cells transfected with luciferase siRNA. At 24 h after transfection by T3 siRNA, there is a 10% reduction in the cytoplasmic concentrations of tRNALys isoacceptors, while in the virions tRNALys isoacceptor concentrations are reduced approximately 45%. At 48 h posttransfection with T3 siRNA, cytoplasmic concentration of tRNALys isoacceptors have decreased 20%, while the concentration of their viral counterparts have decreased approximately 50%.

FIG. 4.

Effect of T3 siRNA upon tRNALys incorporation into HIV-1 and  annealing to viral RNA. Following the protocol described in the legend to Fig. 2, 293T cells were transfected with HIV-1 proviral DNA and siRNA, and cells and virus were collected. Cellular and viral RNA were isolated. Dot blots of cellular RNA were hybridized with probes specific for β-actin mRNA and for

annealing to viral RNA. Following the protocol described in the legend to Fig. 2, 293T cells were transfected with HIV-1 proviral DNA and siRNA, and cells and virus were collected. Cellular and viral RNA were isolated. Dot blots of cellular RNA were hybridized with probes specific for β-actin mRNA and for  or

or  . Dot blots of viral RNA were hybridized with probes specific for viral genomic RNA and for

. Dot blots of viral RNA were hybridized with probes specific for viral genomic RNA and for  or

or  . Blots were quantitated by phosphorimaging. (A and C) Cellular tRNALys:β-actin mRNA ratio at 24 h (A) and 48 h (C) post-siRNA transfection. (B and D) Viral tRNALys:viral genomic RNA ratio at 24 h (B) and 48 h (D) post-siRNA transfection. Ratios for cells transfected with T3 siRNA and for the viruses produced from these cells were normalized to values found for the control cells and for the viruses produced from them. (E and F) The annealing of viral

. Blots were quantitated by phosphorimaging. (A and C) Cellular tRNALys:β-actin mRNA ratio at 24 h (A) and 48 h (C) post-siRNA transfection. (B and D) Viral tRNALys:viral genomic RNA ratio at 24 h (B) and 48 h (D) post-siRNA transfection. Ratios for cells transfected with T3 siRNA and for the viruses produced from these cells were normalized to values found for the control cells and for the viruses produced from them. (E and F) The annealing of viral  to the viral RNA genome. Total viral RNA was used as the source of primer

to the viral RNA genome. Total viral RNA was used as the source of primer  /viral RNA template in an in vitro reverse transcription reaction, as described in Materials and Methods. (E) Six-base-extended

/viral RNA template in an in vitro reverse transcription reaction, as described in Materials and Methods. (E) Six-base-extended  , resolved by 1D PAGE and detected by autoradiography or phosphorimaging. Each reaction used an equal amount of viral genomic RNA, as determined by hybridization with a genomic RNA-specific probe. (F) RT-extendable

, resolved by 1D PAGE and detected by autoradiography or phosphorimaging. Each reaction used an equal amount of viral genomic RNA, as determined by hybridization with a genomic RNA-specific probe. (F) RT-extendable  :genomic RNA ratios, normalized to virus produced from control cells, determined at 24 and 48 h post-siRNA transfection. The bar graphs represent the means of experiments performed three times or more, and the error bars represent standard deviations.

:genomic RNA ratios, normalized to virus produced from control cells, determined at 24 and 48 h post-siRNA transfection. The bar graphs represent the means of experiments performed three times or more, and the error bars represent standard deviations.

The further effect of the reduction in viral  upon viral

upon viral  annealing to viral genomic RNA is seen in Fig. 4E. To measure the amount of

annealing to viral genomic RNA is seen in Fig. 4E. To measure the amount of  placed onto the primer binding site in vivo, total viral RNA is used as the source of primer or template in an in vitro reverse transcription reaction using exogenous HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (RT). Priming of reverse transcription will result in a

placed onto the primer binding site in vivo, total viral RNA is used as the source of primer or template in an in vitro reverse transcription reaction using exogenous HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (RT). Priming of reverse transcription will result in a  primer extended by 6 bases, which can be detected by 1D PAGE. The electrophoretic results are shown in Fig. 4E and presented graphically in Fig. 4F. At 24 h after T3 siRNA transfection, the virions show approximately 55% reductions in

primer extended by 6 bases, which can be detected by 1D PAGE. The electrophoretic results are shown in Fig. 4E and presented graphically in Fig. 4F. At 24 h after T3 siRNA transfection, the virions show approximately 55% reductions in  annealing and, 24 h later, approximately 65% reduction in annealing, compared to the control cells transfected with luciferase siRNA.

annealing and, 24 h later, approximately 65% reduction in annealing, compared to the control cells transfected with luciferase siRNA.

Effect of T3 siRNA upon viral infectivity and viral production.

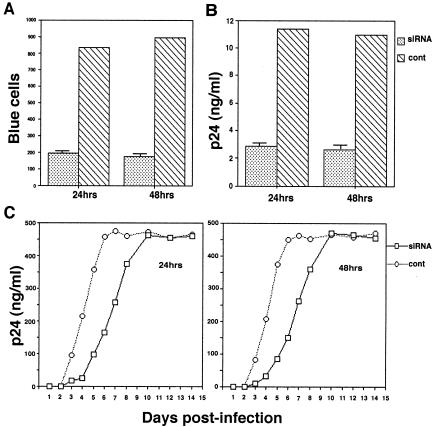

The MAGI assay (16) was used to compare single-round infectivity of the viral preparations produced from 293T cells transfected with either T3 siRNA or luciferase siRNA (control cells). The infectivity of the different viral populations is graphed in Fig. 5A. Figure 5A shows the number of infected (blue) cells counted in 10 high-power microscope fields and indicates that infectivity of viruses produced from cells transfected with T3 siRNA is 20 to 25% of virions produced from the control cells, when measured using viruses at 24 or 48 h post-siRNA transfection. Figure 5B also shows the amount of extracellular viruses produced (measured as p24 released into the cell culture supernatant), and these results reflect viral infectivity data in Fig. 5A.

FIG. 5.

Effect of T3 siRNA upon viral infectivity and viral particle production. Viruses produced from siRNA-transfected 293T cells, as described in the Fig. 4 legend, were used to infect cells to measure single-round infectivity and particle production, as well as rates of more long-term viral production. (A and B) Single-round infectivity and virus production. Equal amounts of virions produced from 293T cells at 24 or 48 h posttransfection with T3 siRNA or luciferase siRNA (cont.) were used to infect CD4-positive HeLa cells containing the β-galactosidase gene fused to the HIV-1 LTR. Virions produced were assayed for viral infectivity by the MAGI assay (A), which measures the number of blue cells per 10 high-power microscope fields, or for extracellular particle production by measuring p24 released into the cell culture medium (B). (C) The ability of the same viruses to initiate infection in MT2 cells not transfected with siRNA was determined by measuring p24 released into the cell culture medium over time. The bar graphs represent the means of experiments performed three times or more, and the error bars represent standard deviations.

The lower infectivity of virions produced from 293T cells containing T3 siRNA is also evident when MT2 cells not transfected with siRNA are infected with these viruses. In Fig. 5C, the ability of these viruses to initiate infection in MT2 cells containing no siRNA was determined by measuring p24 released into the cell culture medium over time. The early lag in replication seen for virions produced from T3 siRNA-transfected 293T cells reflects the initial lower infectivity of these viruses, but the later replication rate in MT2 cells becomes similar to that of virions produced from the control luciferase siRNA-transfected 293T cells. This is expected since after the first round of infection, virions produced from MT2 cells should be identical and provides further support that the infecting virions utilize for reverse transcription the  and LysRS obtained in the cell in which they assembled.

and LysRS obtained in the cell in which they assembled.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have indicated the following about tRNALys and LysRS packaging into virions: (i) the viral Gag precursor protein is sufficient to package LysRS into Gag viral-like particles (4), and (ii) the viral precursor protein Gag-Pol is required to package tRNALys into virions (15, 21). Since Gag and Gag-Pol interact during viral assembly (25, 29), a likely model for tRNALys packaging would include a Gag/Gag-Pol complex interacting with a tRNALys/LysRS complex, with Gag interacting with LysRS and Gag-Pol interacting with tRNALys. LysRS may therefore serve as the signal for targeting tRNALys for incorporation into the virion by the Gag/Gag-Pol complex.

While overexpression of either  or

or  in the cell will result in an increase in that specific tRNALys isoacceptor in the virion, the total tRNALys/virion remains the same, i.e., an increase in one tRNALys isoacceptor results in a decrease in the other (10). The molecule that initially limits the tRNALys/virion appears to be LysRS, since we have previously shown that overexpression of LysRS results in a maximum twofold increase in all major tRNALys isoacceptors (10). Further increases in viral tRNALys may be limited by the amount of Gag-Pol incorporated, which is not altered during the increase in viral tRNALys (10). Cellular LysRS and tRNALys are likely to be present in great excess over the amount packaged into virions, since infection of cells with HIV-1 does not noticeably reduce cell replication. It seems likely, therefore, that if LysRS represents an initially limiting factor for tRNALys incorporation into HIV-1, the tRNALys/LysRS complex that interacts with viral proteins may be a small pool separate from the bulk cytoplasmic pool.

in the cell will result in an increase in that specific tRNALys isoacceptor in the virion, the total tRNALys/virion remains the same, i.e., an increase in one tRNALys isoacceptor results in a decrease in the other (10). The molecule that initially limits the tRNALys/virion appears to be LysRS, since we have previously shown that overexpression of LysRS results in a maximum twofold increase in all major tRNALys isoacceptors (10). Further increases in viral tRNALys may be limited by the amount of Gag-Pol incorporated, which is not altered during the increase in viral tRNALys (10). Cellular LysRS and tRNALys are likely to be present in great excess over the amount packaged into virions, since infection of cells with HIV-1 does not noticeably reduce cell replication. It seems likely, therefore, that if LysRS represents an initially limiting factor for tRNALys incorporation into HIV-1, the tRNALys/LysRS complex that interacts with viral proteins may be a small pool separate from the bulk cytoplasmic pool.

In this work, we have provided evidence that the cellular pool that serves as the source of viral LysRS may be newly synthesized LysRS. The incorporation of LysRS into viruses is very sensitive to the decrease in newly synthesized LysRS induced by siRNA. An 80% decrease in newly synthesized LysRS is accompanied by a similar decrease in viral LysRS at a point in which the total cellular LysRS has been reduced by only 20 to 25%. In fact, it is not known what fraction of cellular LysRS is found as part of a tRNALys/LysRS complex. In higher eukaryotes, LysRS is primarily found as the tightest binding component in a cytoplasmic high molecular weight complex (HMW aaRS complex) that also contains eight other aaRSs and three non-tRNA synthetase proteins, p18, p38, and p43 (27). We have reported that two of the aaRS found in this complex (isoleucine-tRNA synthetase and prolyl-tRNA synthetase) are not found in HIV-1 (4). Other HMW aaRS complex proteins that we have found to be absent in HIV-1 now include ArgRS, GlnRS, MetRS, p18, p38, and p43 (unpublished). The function of this cytoplasmic HMW aaRS complex is not known, and it is possible that the tRNALys/LysRS complex represents a transitory state, with aminoacylated tRNAs moving rapidly into complexes with EF1 alpha, the protein which carries tRNAs to the ribosome.

Although siRNA decreases viral LysRS by 80%, the reduction in viral tRNALys isoacceptors is less, i.e., approximately 40 to 50%. In wild-type virions, the number of LysRS and tRNALys molecules/virion are similar, i.e., approximately 20 to 30 molecules/virion (3, 11), indicating a tRNALys/LysRS ratio close to 1. However, LysRS is a class IIb synthetase, and in vitro band shift experiments have indicated that another member of this class, AsnRS, can bind one or two molecules of cognate tRNAAsn (9). It is therefore possible that a decreased availability of LysRS for viral incorporation can be compensated for by the remaining incorporated LysRS species binding more than one tRNALys molecule. The  annealing reported here reflect the amount of tRNALys incorporated, as we have previously reported (10).

annealing reported here reflect the amount of tRNALys incorporated, as we have previously reported (10).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research and the Canadian Foundation for AIDS Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bernstein, E., A. A. Caudy, S. M. Hammond, and G. J. Hannon. 2001. Role for a bidentate ribonuclease in the initiation step of RNA interference. Nature 409:363-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cen, S., Y. Huang, A. Khorchid, J. L. Darlix, M. A. Wainberg, and L. Kleiman. 1999. The role of Pr55gag in the annealing of tRNA3Lys to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomic RNA. J. Virol. 73:4485-4488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cen, S., H. Javanbakht, S. Kim, K. Shiba, R. Craven, A. Rein, K. Ewalt, P. Schimmel, K. Musier-Forsyth, and L. Kleiman. 2002. Retrovirus-specific packaging of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases with cognate primer tRNAs. J. Virol. 76:13111-13115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cen, S., A. Khorchid, H. Javanbakht, J. Gabor, T. Stello, K. Shiba, K. Musier-Forsyth, and L. Kleiman. 2001. Incorporation of lysyl-tRNA synthetase into human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 75:5043-5048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chomczynski, P., and N. Sacchi. 1987. RNA isolation from cultured cells. Anal. Biochem. 162:156-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coburn, G. A., and B. R. Cullen. 2002. Potent and specific inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication by RNA interference. J. Virol. 76:9225-9231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elbashir, S. M., J. Harborth, W. Lendeckel, A. Yalcin, K. Weber, and T. Tuschl. 2001. Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in cultured mammalian cells. Nature 411:494-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elbashir, S. M., J. Harborth, K. Weber, and T. Tuschl. 2002. Analysis of gene function in somatic mammalian cells using small interfering RNAs. Methods 26:199-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frugier, M., L. Moulinier, and R. Giege. 2000. A domain in the N-terminal extension of class IIB eukaryotic aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases is important for tRNA binding. EMBO J. 19:2371-2380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gabor, J., S. Cen, H. Javanbakht, M. Niu, and L. Kleiman. 2002. Effect of altering the tRNA3Lys concentration in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 upon its annealing to viral RNA, GagPol incorporation, and viral infectivity. J. Virol. 76:9096-9102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang, Y., J. Mak, Q. Cao, Z. Li, M. A. Wainberg, and L. Kleiman. 1994. Incorporation of excess wild-type and mutant tRNA3Lys into human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 68:7676-7683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacque, J. M., K. Triques, and M. Stevenson. 2002. Modulation of HIV-1 replication by RNA interference. Nature 418:435-438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Javanbakht, H., S. Cen, K. Musier-Forsyth, and L. Kleiman. 2002. Correlation between tRNALys3 aminoacylation and incorporation into HIV-1. J. Biol. Chem. 277:17389-17396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang, M., J. Mak, A. Ladha, E. Cohen, M. Klein, B. Rovinski, and L. Kleiman. 1993. Identification of tRNAs incorporated into wild-type and mutant human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 67:3246-3253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khorchid, A., H. Javanbakht, M. A. Parniak, M. A. Wainberg, and L. Kleiman. 2000. Sequences within Pr160gag-pol affecting the selective packaging of tRNALys into HIV-1. J. Mol. Biol. 299:17-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kimpton, J., and M. Emerman. 1992. Detection of replication-competent and pseudotyped human immunodeficiency virus with a sensitive cell line on the basis of activation of an integrated β-galactosidase gene. J. Virol. 66:2232-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee, N. S., T. Dohjima, G. Bauer, H. Li, M. J. Li, A. Ehsani, P. Salvaterra, and J. Rossi. 2002. Expression of small interfering RNAs targeted against HIV-1 rev transcripts in human cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 20:500-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leis, J., A. Aiyar, and D. Cobrinik. 1993. Regulation of initiation of reverse transcription of retroviruses, p. 33-47. In A. M. Skalka and S. P. Goff (ed.), Reverse transcriptase, vol. 1. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 19.Liang, C., L. Rong, R. S. Russell, and M. A. Wainberg. 2000. Deletion mutagenesis downstream of the 5′ long terminal repeat of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is compensated for by point mutations in both the U5 region and gag gene. J. Virol. 74:6251-6261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mak, J., M. Jiang, M. A. Wainberg, M.-L. Hammarskjold, D. Rekosh, and L. Kleiman. 1994. Role of Pr160gag-pol in mediating the selective incorporation of tRNALys into human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particles. J. Virol. 68:2065-2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mak, J., A. Khorchid, Q. Cao, Y. Huang, I. Lowy, M. A. Parniak, V. R. Prasad, M. A. Wainberg, and L. Kleiman. 1997. Effects of mutations in Pr160gag-pol upon tRNALys3 and Pr160gag-pol incorporation into HIV-1. J. Mol. Biol. 265:419-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mak, J., and L. Kleiman. 1997. Primer tRNAs for reverse transcription. J. Virol. 71:8087-8095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishikura, K. 2001. A short primer on RNAi: RNA-directed RNA polymerase acts as a key catalyst. Cell 107:415-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Novina, C. D., M. F. Murray, D. M. Dykxhoorn, P. J. Beresford, J. Riess, S. K. Lee, R. G. Collman, J. Lieberman, P. Shankar, and P. A. Sharp. 2002. siRNA-directed inhibition of HIV-1 infection. Nat. Med. 8:681-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park, J., and C. D. Morrow. 1992. The nonmyristylated Pr160gag-pol polyprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 interacts with Pr55gag and is incorporated into virus-like particles. J. Virol. 66:6304-6313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qin, X.-F., D. S. An, I. S. Y. Chen, and D. Baltimore. 2003. Inhibiting HIV-1 infection in human T cells by lentiviral-mediated delivery of small interfering RNA against CCR5. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:183-188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robinson, J.-C., P. Kerjan, and M. Mirande. 2000. Macromolecular assemblage of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases: quantitative analysis of protein-protein interactions and mechanism of complex assembly. J. Mol. Biol. 304:983-994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharp, P. A. 2001. RNA interference-2001. Genes Dev. 15:485-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith, A. J., N. Srinivasakumar, M.-L. Hammarskjöld, and D. Rekosh. 1993. Requirements for incorporation of Pr160gag-pol from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 into virus-like particles. J. Virol. 67:2266-2275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stark, G. R., I. M. Kerr, B. R. Williams, R. H. Silverman, and R. D. Schreiber. 1998. How cells respond to interferons. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67:227-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tuschl, T. 2001. RNA interference and small interfering RNAs. ChemBioChem. 2:239-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zamore, P. D. 2001. RNA interference: listening to the sound of silence. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8:746-750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]