Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is increasingly recognized as a systemic disease that is associated with increased serum levels of markers of systemic inflammation. The triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 1 (TREM-1) is a recently identified activating receptor on neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophage subsets. TREM-1 expression is upregulated by microbial products such as the toll-like receptor ligand lipoteichoic acid of Gram-positive or lipopolysaccharides of Gram-negative bacteria. In the present study, sera from 12 COPD patients (GOLD stages I–IV, 51 6%) and 10 healthy individuals were retrospectively analyzed for soluble TREM-1 (sTREM-1) using a newly developed ELISA. In healthy subjects, sTREM-1 levels were low (median 0.25 ng/mL, range 0–5.9 ng/mL). In contrast, levels of sTREM-1 in sera of COPD patients were significantly increased (median 11.68 ng/mL, range 6.2–41.9 ng/mL, ). Furthermore, serum levels of sTREM-1 showed a significant negative correlation with lung function impairment. In summary, serum concentrations of sTREM-1 are increased in patients with COPD. Prospective studies are warranted to evaluate the relevance of sTREM-1 as a potential marker of the disease in patients with COPD.

1. INTRODUCTION

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is characterized by progressive development for the most part irreversible airflow obstruction that involves an abnormal airway inflammatory response [1]. The clinical course of COPD is typically dominated by intermittent exacerbations, responsible for the majority of the disease-associated morbidity and mortality [2, 3].

In recent years COPD has more and more been characterized as a systemic inflammatory disease. Several mediators have been found increased in blood of COPD patients indicating persistent systemic inflammation [4]. The origin of this inflammatory response is unknown but several different mechanisms including smoking itself, a cytokine “spill over” from the lungs, tissue hypoxia, and genetic factors [5] or persistent bacterial colonization of the airways [6–10] have been suggested.

The triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells (TREM-1) is a recently identified activating receptor on neutrophil granulocytes (PMN), monocytes, and macrophage subsets [11, 12]. The expression of TREM-1 is upregulated by microbial products, that is, by toll-like receptor ligands such as lipoteichoic acid (LTA) of Gram-positive or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of Gram-negative bacteria. Ligation of TREM-1 is synergistic with TLR agonists on the activation of receptor bearing cells for the release of inflammatory mediators like TNF- and IL-8 and the initiation of neutrophil respiratory burst [11, 13]. We recently reported that a natural ligand for TREM-1 is present on platelets, although it still needs to be identified [14]. The biological significance of TREM-1 in acute inflammatory responses is documented in mouse models for septic shock, where competition of TREM-1 with a recombinant soluble TREM-1 fusion protein or an putative receptor blocking peptide derived from a conserved region of TREM-1 saved mice from lethal LPS challenge or bacterial sepsis [15–17].

TREM-1 is also produced in a soluble form [18] and released in humans after endotoxin exposition [19] or in patients suffering from severe pneumonia [20] or sepsis [21]. In these critically ill patients, elevated levels of soluble TREM-1 (sTREM-1) are detectable in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid or in plasma, respectively, and have a high accuracy and sensitivity in detecting microbial infections as underlying disease [20, 22, 23]. In addition, the time course of sTREM-1 levels might be a useful parameter in predicting the outcome in sepsis patients [24, 25]. However, a limitation of these studies is certainly that only critically ill patients were examined. A recent study by Richeldi et al. demonstrates that an increase in sTREM-1 is also detectable in patients suffering from community acquired pneumonia caused by extracellular bacteria, but not in patients with interstitial lung disease or tuberculosis [26]. Furthermore, sTREM-1 has been associated with major abdominal surgery and peptic ulcer disease [27, 28].

In the present study, we developed a sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) that is able to detect pg/mL amounts of sTREM-1 in serum of patients. Using this new TREM-1 specific assay, we assessed the amount of sTREM-1 released in 12 patients suffering from COPD and 10 healthy individuals for sTREM-1 and indeed found elevated levels of sTREM-1 in patients COPD, which correlated with disease severity.

2. PATIENTS, MATERIALS, AND METHODS

2.1. Patients

Twelve patients with COPD, all current smokers or exsmokers, were recruited on the basis of their clinical diagnosis and lung function impairment. None of the patients had lung diseases other than COPD and all were in a stable clinical condition for at least 3 month. The control group comprised 10 healthy nonsmoking individuals without the sign of airway obstruction and other significant illness. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee.

All patients with COPD were under treatment with inhaled -adrenoceptor agonists and/or anticholinergics, 3 patients were treated additionally with inhaled steroids, 3 with systemic steroids, and 2 with additional theophyllin, whereas the healthy control subjects did not have medication. Regarding baseline characteristics, there were no other significant differences between groups, except for lung function (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics ( ND not done).

| Control | COPD | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (f/m) | 4/6 | 5/7 |

| Age (y) | ||

| Height (cm) | ||

| BMI () | ||

| Pack years of smoking | 0 | |

| FEV1 (L) | ||

| FEV1 (%predicted) | ||

| FEV1/FVC (%) | ||

| FEV1 Salbutamol (%) | N.D. | |

| RV (%predicted) | ||

| ITGV (L) | ||

| DLCO (%predicted) | ||

| sTREM-1 (ng/mL) | 0.25 (0–5.9) | 11.68 (6.2–41.9 |

* For abbreviations, see text. Mean values SD are given. For sTREM-1 median and range are given regarding the comparison between groups.

2.2. Assessment of lung function

Lung function measurements including the determination of forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), residual volume (RV), intrathoracic gas volume (ITGV), and single breath diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) were performed following established guidelines [29–31] using standard equipment (Masterlab, Jaeger, Höchberg, Germany). Bronchodilator responses were quantified as absolute and percent increase of FEV1 measured 15 minutes after inhalation of 200 salbutamol.

2.3. Transfectants

Full-length cDNA encoding TREM-1 cloned in the eukaryontic expression vector pcDNA3 (Invitrogen) were stably transfected in HEK293 cells with Fugene 6 (Roche) according to standard protocols. The TREM-1cDNAs have been described previously [11]. Transfectants were obtained after G418 selection.

The production recombinant TREM-1::IgG1 fusion protein has been described previously [14].

2.4. Monoclonal antibodies

TREM-1 specific monoclonal antibodies (clone 6B1) were raised by repeated immunization of BALB/c mice with a recombinant TREM-1::IgG1 fusion protein according to standard procedures. Hybridoma supernatants were first screened by ELISA against TREM-1::IgG1 and human IgG (Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen), respectively. Supernatants reacting against TREM-1::IgG1, but not IgG, were subcloned twice and further screened by flow cytometry using TREM-1-transfected 293 cells. Antibodies (Abs) were purified by affinity chromatography on a protein G-Sepharose column. The mAb clones 1C5 and 6B1 were of isotype IgG1.

2.5. Detection of soluble TREM-1 by ELISA

For the detection of soluble TREM-1 (sTREM-1), anti-TREM-1 (6B1) mAb was coated at 0.5 g/mL in PBS, then blocked by addition of 100 of 15% BSA for 2 hours at and washed. Afterward the standard (recombinant TREM-1::IgG1 in 7.5% BSA-PBS) and the samples were added and the plates were incubated for 2 hours at . For analysis of patient samples, sera were diluted in 5% BSA prior to addition to the plates. After incubation, plates were washed and the biotinylated detection polyclonal Ab anti-TREM-1 (R&D Systems) at 5 g/mL in 7.5% BSA-PBS was added for 2 hours at . Plates were then washed and streptavidine-HRP ( in 7.5% BSA-PBS) was added for 1 hour at . Plates were then washed again and developed using the Tetramethylbenzidine Peroxidase Substrate System (KPL, Gaithersburg, Md). The absorbance was measured at 450 nm. Results are shown as means with SD of triplicates. The lower detection limit was defined by 2x SD of the blank values (5 pg/mL). The recovery rate was . Intraassay variation was , interassay variation was .

2.6. Statistical procedures

Mean values, medians, and standard deviation (SD) were computed. sTREM-1 levels were compared between groups using Mann-Whitney-U test. Lung function and other values were compared between groups using unpaired -test. Correlation analysis was performed by Spearman’s rank correlation. Statistical significance was assumed for .

3. RESULTS

3.1. Detection of sTREM-1 in serum by ELISA

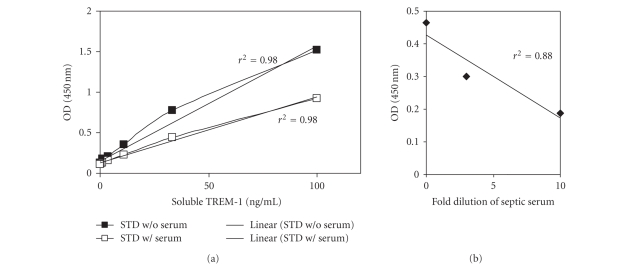

To evaluate the newly developed assay TREM-1-IgG recombinant human TREM-1::IgG1 and serum form a patient with sepsis were analyzed in serial dilutions since high levels of sTREM-1 have been described in sepsis previously [22]. As depicted in Figure 1, the assay allowed the detection of sTREM-1 down to 5 pg/mL sTREM-1 concluding that this new ELISA protocol is a suitable tool to investigate the significance of sTREM-1 in patients.

Figure 1.

ELISA for sTREM-1. (a) Titration of recombinant human TREM-1::IgG1 either in the absence (filled symbols) or presence of normal human serum (open symbols). (b) Serial dilution of serum from a septic patient. The values are the correlation coefficients of the depicted data.

3.2. Serum levels of sTREM-1 are elevated in patients with COPD

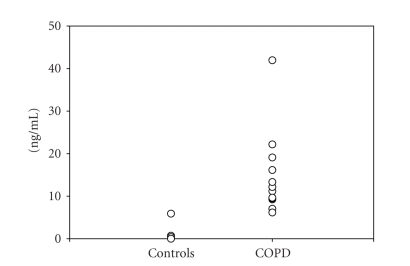

None of the control patients showed airway obstruction (Table 1), whereas COPD patients showed a significantly decreased FEV1 and FEV1% predicted (Table 1). According to GOLD criteria 2, patients were categorized as stage I (mild), 3 patients as stage II (moderate), 6 patients as stage III (severe) and 1 patients as stage IV (very severe) [32]. COPD patients also showed a significant increase in RV () as well as ITGV () and a significant decrease in DLCO () compared to the control subjects (Table 1). None of the COPD patients showed a positive response to salbutamol, defined as an increase in FEV1 of at least 15% and 200 mL. Serum levels of sTREM-1 were significantly () increased in patients with COPD compared to controls. In contrast, in healthy subjects sTREM-1 was detectable in serum samples of only 6 subjects (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Concentration of sTREM-1 in serum of healthy controls (controls) and patients with COPD.

3.3. Relationship between serum levels of sTREM-1 and clinical parameters

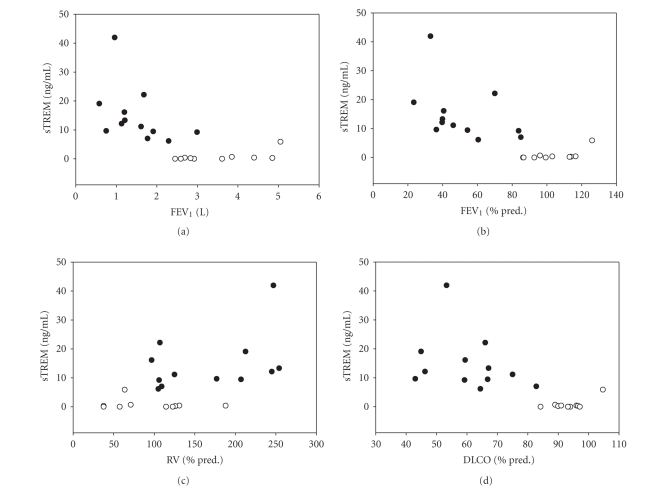

Levels of sTREM-1 in serum were correlated with absolute FEV1 (, ), FEV1% predicted (, ) (Figure 3) and FEV1% VC (, ). Also significant correlations were detected to RV (, ), DLCO (, ) and VC % predicted (, ). No relationship was found between sTREM-1 and BMI (, ), age of the patient (, ), height (, ), or weight (, ).

Figure 3.

Relationship between sTREM-1 serum levels and absolute FEV1(panel A), FEV1% predicted (panel B), residual volume (RV) % predicted (panel C), and diffusion capacity (DLCO) % predicted (panel D). Control subjects are represented by open circles, patients with COPD by closed circles.

Due to the limited number of patients in our study, it was not possible to analyze correlations between lung function parameter and sTREM-1 levels.

4. DISCUSSION

In the present study, we show that sTREM-1 levels in serum are elevated in patients with COPD compared to healthy, nonsmoking controls. Furthermore, we demonstrate that serum levels of sTREM-1 are correlated with disease severity.

COPD is a multicomponent disease which includes inflammatory changes in the lung. Inflammatory cells in lungs of patients with COPD are mainly neutrophil granulocytes and inflammation in the lung is more pronounced with worse lung function [33]. Also, numbers of neutrophils in sputum correlate with disease progression [34]. In many patients, COPD has also significant systemic consequences. This includes loss of lean bodymass, cardiovascular effects, osteoporosis, muscle wasting but also a systemic inflammatory response. Indeed, in patients with COPD, even during stable disease, there is an increased number of leukocytes in peripheral blood [35, 36] Peripheral neutrophils from patients with COPD show enhanced chemotaxis and extracellular proteolysis [37], produce more reactive oxygen species [38], and enhanced expression of several surface adhesion molecules [39]. Also increased levels of TNF-, IL-6, IL-8, C-reactive protein, and fibrinogen in serum can be detected in serum of patients with stable COPD and some of these systemic inflammatory changes seem to be related to disease severity [4] and correlate with severity of systemic consequences like muscle wasting [40].

In the present study, we describe a new ELISA for the detection of sTREM-1 in serum. In contrast, most previous studies have used an immunodot blot technique for the detection of sTREM-1 [22, 25, 41]. This technique allows the sensitive detection of sTREM-1 in body fluids. However, for assessment of sTREM-1 in a clinical routine setting detection by sandwich ELISA has the advantage that greater sample numbers may be processed simultaneously with increased specificity. Therefore, we developed a new sensitive ELISA using a monoclonal antibody to capture sTREM-1 in sera of patients and a polyclonal anti-TREM-1 for detection. Using our new sandwich-ELISA protocol, we established a standard laboratory method for the sensitive and specific detection of sTREM-1 in body fluids avoiding the pitfalls and potential disadvantages associated with the immunodot blot technique used so far. When analyzing serum samples from patients with stable COPD, we were able to detect sTREM-1 in all samples. In contrast, in samples from healthy control subjects sTREM-1 was only detectable in 6 of the patients and only in very low amounts. In line with previous data obtained from patients suffering from severe inflammatory disorders like pneumonia or sepsis [22–24], our data indicate that sTREM-1 might be a result of neutrophil activation also in COPD patients. The current view in terms of the pathophysiology suggests that sTREM-1 is an anti-inflammatory mediator of sepsis [42], released as a counter regulator of TREM-1 mediated activation. Our recent results demonstrating that sTREM-1 interferes with the TREM-1/ligand interaction of neutrophil and platelets support this view [14].

Previous studies have described increased levels of sTREM-1 in patients with sepsis [22], pneumonia [20] but also exacerbated asthma and COPD. By using an immunoblot technique, Phua et al. found increased levels of sTREM-1 especially in patients with COPD during an Anthonisen-type 1 exacerbation [41].

The authors speculated that the patients with type 1 exacerbation shad higher airway bacterial loads, which triggered systemic inflammation and increased sTREM-1 levels [43, 44]. In the present study, increased levels of sTREM-1, measured by ELISA, were detected even in patients with stable disease. This could be due to an increased sensitivity of the newly introduced ELISA.

Potential explanations for the increased levels of sTREM-1 observed in this group of stable patients with COPD could be persistent bacterial colonization of the airways, which has been demonstrated by several groups [6–9]. These colonizations can be associated with elevated levels of inflammatory mediators like IL-8, LTB4, and TNF- in the lungs of patients with clinically stable disease [10]. In addition, increased plasma fibrinogen and IL-6 levels are detectable in these bacterially colonized patients suggesting that colonization contributes to systemic inflammation [44]. In patients with more advanced disease, higher levels of serum CRP have been described, suggesting increased systemic inflammatory reaction [45–47]. As sTREM-1 can be induced by increased systemic inflammation [20, 23, 24] the increased sensitivity of our ELISA assay could be the reason for increased levels of sTREM-1 detected in the present study population.

Additionally, we found a correlation of sTREM-1 levels in serum with disease severity, described by impaired lung function, in the COPD group. This was the case when absolute and relative values of FEV1 as markers for airway obstruction, RV for hyperinflation, and also diffusion capacity as a marker for emphysema were analyzed. No correlations were found for age, height, weight, or BMI. Also levels of sTREM-1 in serum were independent for medication used by patients. Some of the patients with more severe disease (GOLD stadium III–IV) treated with systemic steroid still showed increased levels of sTREM-1 in serum. Although this analysis is somewhat limited by low numbers of patients and control sTREM-1 may yet be another systemic marker correlated with disease severity.

In summary we show increased serum levels of sTREM-1 in patients with clinical stable COPD, and a correlation between serum levels and disease severity. sTREM-1 might be a useful marker for systemic inflammation in patients with COPD. Further prospective studies are needed to evaluate the true diagnostic value of sTREM-1 in this patient population.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Andrea Drescher and Annekatrin Meinl for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (RA988/2-1/2 and RA988/3-1 to H. Schild and M. P. Radsak and SFB 548, A11 to C. Taube). M. P. Radsak and C. Taube contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Murphy TF. The role of bacteria in airway inflammation in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 2006;19(3):225–230. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000224815.89363.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mallia P, Johnston SL. Mechanisms and experimental models of chronic obstructive pulmonary exacerbations. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2005;2(4):361–366. doi: 10.1513/pats.200504-025SR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sethi S. Pathogenesis and treatment of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2005;26(2):192–203. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-869538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gan WQ, Man SFP, Senthilselvan A, Sin DD. Association between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and systemic inflammation: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Thorax. 2004;59(7):574–580. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.019588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agustí AGN. Systemic effects of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2005;2(4):367–370. doi: 10.1513/pats.200504-026SR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hill AT, Campbell EJ, Hill SL, Bayley DL, Stockley RA. Association between airway bacterial load and markers of airway inflammation in patients with stable chronic bronchitis. The American Journal of Medicine. 2000;109(4):288–295. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00507-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stockley RA, Hill AT, Hill SL, Campbell EJ. Bronchial inflammation: its relationship to colonizing microbial load and -antitrypsin deficiency. Chest. 2000;117(5, supplment 1):291S–293S. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.5_suppl_1.291s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soler N, Ewig S, Torres A, Filella X, Gonzalez J, Zaubet A. Airway inflammation and bronchial microbial patterns in patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. European Respiratory Journal. 1999;14(5):1015–1022. doi: 10.1183/09031936.99.14510159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sethi S, Muscarella K, Evans N, Klingman KL, Grant BJB, Murphy TF. Airway inflammation and etiology of acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis. Chest. 2000;118(6):1557–1565. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.6.1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banerjee D, Khair OA, Honeybourne D. Impact of sputum bacteria on airway inflammation and health status in clinical stable COPD. European Respiratory Journal. 2004;23(5):685–691. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00056804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bouchon A, Dietrich J, Colonna M. Cutting edge: inflammatory responses can be triggered by TREM-1, a novel receptor expressed on neutrophils and monocytes. Journal of Immunology. 2000;164(10):4991–4995. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.10.4991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schenk M, Bouchon A, Birrer S, Colonna M, Mueller C. Macrophages expressing triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 are underrepresented in the human intestine. Journal of Immunology. 2005;174(1):517–524. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Radsak MP, Salih HR, Rammensee H-G, Schild H. Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 in neutrophil inflammatory responses: differential regulation of activation and survival. Journal of Immunology. 2004;172(8):4956–4963. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.8.4956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haselmayer P, Grosse-Hovest L, von Landenberg P, Schild H, Radsak MP. TREM-1 ligand expression on platelets enhances neutrophil activation. Blood. 2007;110(3):1029–1035. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-069195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bouchon A, Facchetti F, Weigand MA, Colonna M. TREM-1 amplifies inflammation and is a crucial mediator of septic shock. Nature. 2001;410(6832):1103–1107. doi: 10.1038/35074114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibot S, Kolopp-Sarda M-N, Béné M-C, et al. A soluble form of the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 modulates the inflammatory response in murine sepsis. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2004;200(11):1419–1426. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibot S, Buonsanti C, Massin F, et al. Modulation of the triggering receptor expressed on the myeloid cell type 1 pathway in murine septic shock. Infection and Immunity. 2006;74(5):2823–2830. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.5.2823-2830.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gingras M-C, Lapillonne H, Margolin JF. TREM-1, MDL-1, and DAP12 expression is associated with a mature stage of myeloid development. Molecular Immunology. 2002;38(11):817–824. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(02)00004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knapp S, Gibot S, de Vos A, Versteeg HH, Colonna M, van der Poll T. Cutting edge: expression patterns of surface and soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 in human endotoxemia. Journal of Immunology. 2004;173(12):7131–7134. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gibot S, Cravoisy A, Levy B, Bene M-C, Faure G, Bollaert P-E. Soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells and the diagnosis of pneumonia. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;350(5):451–458. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gibot S. Clinical review: role of triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 during sepsis. Critical Care. 2005;9(5):485–489. doi: 10.1186/cc3732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gibot S, Kolopp-Sarda M-N, Béné MC, et al. Plasma level of a triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1: its diagnostic accuracy in patients with suspected sepsis. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2004;141(1):9–15. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-1-200407060-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibot S. Soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells and the diagnosis of pneumonia and severe sepsis. Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2006;27(1):29–33. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-933671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Determann RM, Millo JL, Gibot S, et al. Serial changes in soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells in the lung during development of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Intensive Care Medicine. 2005;31(11):1495–1500. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2818-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gibot S, Cravoisy A, Kolopp-Sarda M-N, et al. Time-course of sTREM (soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells)-1, procalcitonin, and C-reactive protein plasma concentrations during sepsis. Critical Care Medicine. 2005;33(4):792–796. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000159089.16462.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richeldi L, Mariani M, Losi M, et al. Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells: role in the diagnosis of lung infections. European Respiratory Journal. 2004;24(2):247–250. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00014204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koussoulas V, Vassiliou S, Demonakou M, et al. Soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells (sTREM-1): a new mediator involved in the pathogenesis of peptic ulcer disease. European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2006;18(4):375–379. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200604000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahdy AM, Lowes DA, Galley HF, Bruce JE, Webster NR. Production of soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells by lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human neutrophils involves de novo protein synthesis. Clinical and Vaccine Immunology. 2006;13(4):492–495. doi: 10.1128/CVI.13.4.492-495.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacIntyre N, Crapo RO, Viegi G, et al. Standardisation of the single-breath determination of carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. European Respiratory Journal. 2005;26(4):720–735. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. European Respiratory Journal. 2005;26(2):319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wanger J, Clausen JL, Coates A, et al. Standardisation of the measurement of lung volumes. European Respiratory Journal. 2005;26(3):511–522. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00035005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pauwels RA, Buist AS, Calverley PMA, Jenkins CR, Hurd SS. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: NHLBI/WHO Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) workshop summary. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2001;163(5):1256–1276. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.5.2101039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hogg JC, Chu F, Utokaparch S, et al. The nature of small-airway obstruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;350(26):2645–2653. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parr DG, White AJ, Bayley DL, Guest PJ, Stockley RA. Inflammation in sputum relates to progression of disease in subjects with COPD: a prospective descriptive study. Respiratory Research. 2006;7:136. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sauleda J, García-Palmer FJ, González G, Palou A, Agustí AGN. The activity of cytochrome oxidase is increased in circulating lymphocytes of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, and chronic arthritis. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2000;161(1):32–35. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.1.9807079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lewis SA, Pavord ID, Stringer JR, Knox AJ, Weiss ST, Britton JR. The relation between peripheral blood leukocyte counts and respiratory symptoms, atopy, lung function, and airway responsiveness in adults. Chest. 2001;119(1):105–114. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burnett D, Hill SL, Chamba A, Stockley RA. Neutrophils from subjects with chronic obstructive lung disease show enhanced chemotaxis and extracellular proteolysis. The Lancet. 1987;330(8567):1043–1046. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91476-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Noguera A, Batle S, Miralles C, et al. Enhanced neutrophil response in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2001;56(6):432–437. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.6.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Noguera A, Busquets X, Sauleda J, Villaverde JM, MacNee W, Agustí AGN. Expression of adhesion molecules and G proteins in circulating neutrophils in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1998;158(5, part 1):1664–1668. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.5.9712092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'byrne PM, Postma DS. The many faces of airway inflammation. Asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Asthma Research Group. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1999;159(5, part 2):S41–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Phua J, Koay ESC, Zhang D, et al. Soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 in acute respiratory infections. European Respiratory Journal. 2006;28(4):695–702. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00005606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gibot S, Massin F. Soluble form of the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 1: an anti-inflammatory mediator? Intensive Care Medicine. 2006;32(2):185–187. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-0018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anthonisen NR, Manfreda J, Warren CP, Hershfield ES, Harding GK, Nelson NA. Antibiotic therapy in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1987;106(2):196–204. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-106-2-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hurst JR, Perera WR, Wilkinson TMA, Donaldson GC, Wedzicha JA. Systemic and upper and lower airway inflammation at exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2006;173(1):71–78. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200505-704OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sin DD, Paul Man SF. Why are patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at increased risk of cardiovascular diseases? The potential role of systemic inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Circulation. 2003;107(11):1514–1519. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000056767.69054.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mannino DM, Ford ES, Redd SC. Obstructive and restrictive lung disease and markers of inflammation: data from the third national health and nutrition examination. The American Journal of Medicine. 2003;114(9):758–762. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00185-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Broekhuizen R, Wouters EFM, Creutzberg EC, Schols AMWJ. Raised CRP levels mark metabolic and functional impairment in advanced COPD. Thorax. 2006;61(1):17–22. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.041996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]