Abstract

Two independent binding sites on simian virus 40 (SV40) T antigen for topoisomerase I (topo I) were identified. One was mapped to the N-terminal domain (residues 83 to 160) by a combination of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) and glutathione S-transferase (GST) pull-down assays performed with various T antigen deletion mutants. The second was mapped to the C-terminal domain (residues 602 to 708). The region in human topo I that binds to both sites in T antigen was identified by ELISAs, GST pull-down assays, and double-hexamer binding assays with topo I deletion mutants. This region corresponds to a distinct domain on topo I known as the cap region that maps from residues 175 to 433. By combining these data with information about the structure of T-antigen double hexamers associated with origin DNA, we propose that the cap region of topo I associates specifically with both ends of the double hexamer bound to the SV40 origin to initiate DNA replication.

The replication of simian virus 40 (SV40) DNA is becoming fairly well understood. Advances in this field have become possible because one can carry out DNA replication assays, in addition to the biochemistry, in a cell-free system with purified components (12, 13, 20, 24, 45, 49, 52). All of the proteins required for this in vitro reaction have been isolated. Initiation of replication begins when a double hexamer of T antigen assembles over the origin. The formation of the double hexamer then triggers a structural rearrangement of the DNA whereby the EP region is partially melted and the AT track is untwisted (1-4, 7, 30). Synthesis of RNA primers takes place after topo I, replication protein A, and DNA polymerase α/primase (pol/prim) assemble over the origin (11, 27, 51). The RNA primers are extended by polymerase α. Elongation of DNA chains is catalyzed by DNA polymerase δ in association with PCNA and RF-C (10, 11, 28).

There is considerable interest concerning the mechanism by which the initiation complex assembles. Older evidence indicated that double hexamers of T antigen assemble over the replication origin from individual monomers (6, 19), but more recent data demonstrate that preformed hexamers can also bind and unwind duplex DNA (46). In either case, it is clear that a complete double hexamer is the active form of the helicase (39). The three cellular initiation factors (topo I, replication protein A [RPA], and pol/prim) are then recruited, but the order in which they bind has not been determined. Our laboratory has generated a large amount of data supporting the idea that topo I is an integral component of the initiation complex and that it must be present from the beginning of DNA replication to function (14, 44). The recruitment of topo I is dependent on the presence of double hexamers in association with DNA (14). The presence of a nucleotide is required, but ATP hydrolysis is not needed (14). topo I can bind to T antigen directly in the absence of DNA (35, 36), as well as to DNA (26, 40). Likewise, the recruitment of RPA and pol/prim appears to depend on multiple protein-protein and protein-DNA interactions (see reference 33 for a review).

In order to elucidate the structure and composition of the initiation complex, it is necessary to map all protein-protein interaction sites. Previous data from our lab have demonstrated the existence of two independent topo I binding regions in T antigen (35): one in the N-terminal region (residues 1 to 246) and the other after residue 246. The functional significance of each of these two binding sites is not known. Previous mapping studies implicated the N-terminal region of topo I in binding to T antigen (16), but data from our lab has shown that topo 70, which is missing the first 174 amino acids of the enzyme (42), can stimulate T-antigen-dependent DNA replication to the same extent as full-length topo I (P. Trowbridge and D. Simmons, unpublished data), indicating that this binding site is not physiologically significant. In an effort to gain insight into their function, each topo I binding region on T antigen was mapped. Likewise, the region in topo I responsible for binding to each of these sites in T antigen was identified. The results, combined with recent structure data of T antigen double hexamers (47, 48), strongly suggest that the cap region of topo I interacts specifically with sequences near the tips of the double hexamer in the presence of origin DNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Purification of T antigen and T-antigen fragments.

Wild-type (WT) T antigen was purified from baculovirus-infected insect cells by immunoaffinity purification as previously described (35) by using PAb101 antibody (15). Baculovirus transfer vectors expressing various T antigen constructs were generated by ligating a PCR-derived DNA fragment into pVL1393 or pAcG1 for glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged proteins (Pharmingen) as previously described (35). After DNA sequencing to confirm the correct sequence, the transfer vector was cotransfected with BaculoGold (Pharmingen) into Sf9 cells to generate recombinant baculoviruses according to the recommendations of the manufacturer. Untagged T-antigen fragments were purified by immunoaffinity with the appropriate monoclonal antibody (PAb101 or PAb419 [15] or PAb416 [17]). PAb101 was used for all C-terminus containing polypeptides, PAb419 was used for the N-terminal constructs except for 83-246, in which case PAb416 was used. GST-tagged T-antigen fragments were purified by binding to GST-Sepharose beads as described previously (53). Proteins were either left attached to beads and the beads were used directly in binding assays, or they were first eluted from beads with free glutathione. The concentration of each protein was estimated by Coomassie blue staining of sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels with phosphorylase b as a marker.

Purification of topo I and fragments.

Untagged WT topoisomerase I, topo 70, and topo 58 were purified by standard chromatography from extracts of baculovirus-infected Sf9 cells as previously described (42). Protein concentrations were estimated by reactivity with Bio-Rad protein reagent. GST-tagged proteins were either expressed in bacteria or in insect cells. The bacterially expressed polypeptides (see Fig. 1) were purified as described by Yang and Champoux (53) from Escherichia coli TOP10F′ (Invitrogen) cells transformed with pGEX-derived plasmids. Some GST-tagged proteins were expressed in insect cells. These were made by first introducing a PCR-derived DNA fragment into pAcG1, followed by cotransfection in Sf9 cells to make the recombinant virus. Purification of GST-tagged topo I constructs was carried out as described above for the GST-tagged T-antigen fragments.

FIG. 1.

(Top) Map of topoisomerase I deletion mutants used in this study. Various fragments of human topo I were expressed either in bacteria (t) or in baculovirus-infected insect cells (v). The topo I polypeptides correspond to known topo I domains (40-42).

ELISAs.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were performed essentially as described previously (35). In brief, WT or truncated topo I was allowed to bind to a microtiter plate. The wells were blocked with phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% gelatin, and various amounts of WT T antigen or T-antigen fragments were added. After binding and washing steps, an antibody specific for the T-antigen peptide was added, followed by the addition of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG). A peroxidase substrate (ortho-phenylenediamine) was added and, after a few minutes, H2SO4 was used to stop the reaction and the absorbance was read at 490 nm by using a Dynex plate reader.

GST-protein binding assays.

GST-protein binding assays were performed essentially as described previously (18) with some modifications. GST-tagged proteins bound to glutathione-Sepharose or -agarose beads were washed twice with 30 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.8)-10 mM KCl-7 mM MgCl2 and incubated for 3 h at room temperature with either T antigen or topo I intact molecules or fragments in 250 μl of the same buffer containing 2% nonfat dry milk. The beads were recovered by centrifugation and washed three times with 1 ml of 30 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.8)-25 mM KCl-7 mM MgCl2-0.25% inositol-0.25 mM EDTA-0.1% Nonidet P-40. This washing procedure was not sufficiently stringent for the binding assays with GST-bound C-terminal fragments of T antigen (see Fig. 9), and so for these experiments beads were washed with 0.05 M Tris (pH 8.0)-0.5 M NaCl-0.001 M EDTA-10% glycerol-1% Nonidet P-40. The bound proteins were eluted by boiling in 1 volume of 4× sample buffer, separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and detected by Western blot analysis.

FIG. 9.

GST-binding assay between WT topo I and various C-terminal T antigen constructs. A total of 30 μl of Sepharose beads containing 8 μg of bound GST 110-708 or the molar equivalent of various C-terminal constructs or control GST beads was incubated with 1.8 μg of purified WT topo I. After the beads were washed, bound topo I was eluted with electrophoresis sample buffer and applied to an 8% gel. Detection was with 8G6 monoclonal antibody and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG.

Origin DNA-dependent binding assays.

The preparation and purification of a small circular DNA containing the origin of replication was as previously described (14). Binding assays contained 5 ng of circular DNA, 400 ng of immunoaffinity-purified T antigen, and 100 ng of GST-topo 70 or equivalent molar amounts of other truncated products. After 1 h at 37°C, glutaraldehyde was added to 0.1%, and incubation was continued for an additional 10 min. The reactions were loaded onto a composite polyacrylamide-agarose gel as described previously (14). Protein-DNA complexes were transferred to nitrocellulose, and the proteins on the membrane were detected by a Western reaction with an anti-GST antibody.

RESULTS

Mapping of T-antigen binding site on topo I.

A number of topo I deletion mutants were generated (Fig. 1) and expressed either in bacteria (“t” in Fig. 1) or in baculovirus-infected insect cells (“v” in Fig. 1). The untagged proteins were purified by standard chromatographic procedures as described by Stewart et al. (42). GST-tagged topo I constructs from bacteria were purified on glutathione-agarose beads, and those from insect cells were purified by binding to glutathione-Sepharose beads. The binding of purified untagged topo I deletion mutants to immunoaffinity-purified WT T antigen was monitored by ELISAs as shown in Fig. 2. Both topo I deletion mutants tested (topo 70 and topo 58) bound to T antigen, indicating that the T-antigen binding site was located between residues 175 and 659. topo 70 routinely bound better in this assay than full-length topo I, but the reason for this is not known.

FIG.2.

(Bottom) ELISA between WT T antigen and various topo I fragments. A total of 100 ng of purified WT topo I, topo 70, or topo 58 was bound to ELISA plates, followed by incubation with various amounts of WT T antigen as shown. The plates were washed and incubated with PAb101, followed by the addition of horseradish peroxidase-labeled anti-mouse IgG and peroxidase substrate. After the reactions were stopped with sulfuric acid, the absorbance at 490 nm was measured by using a plate reader. Control reactions were also performed without topo I but in the presence of all other components. The absorbance values from these wells were subtracted from the corresponding ones obtained in the presence of WT or mutant topo I.

GST-tagged topo I deletion mutants were tested for their ability to bind to WT T antigen, which we have previously shown to contain two separate binding sites for topo I (35) (Fig. 3A). Since topo I and T antigen both bind DNA, we performed these binding reactions in the presence of ethidium bromide, which disrupts DNA-protein interactions (23), to eliminate the possibility that binding is mediated through small amounts of contaminating DNA. WT T antigen bound best to topo 70 and topo 31 (see Fig. 1), although there was some background binding with the other constructs. We also examined the binding to deletion mutants 246-708 and 1-246 of T antigen (Fig. 3B and C), each of which contains one binding site for topo I (35). GST-tagged topo 70 and topo 31 bound to both T antigen mutants well, whereas GST-tagged topo 10 and topo 17 bound poorly, if at all. These data indicate that both the N-terminal and C-terminal binding sites in T antigen interact with topo I within the region specified by topo 31 (amino acids 175 to 433).

FIG. 3.

GST-binding assay between WT T antigen and various topo I fragments. A total of 10 μl of glutathione-Sepharose or -agarose beads containing 18 μg of GST-tagged topo 70 or the molar equivalent of topo 31, topo 17, topo 10, or GST alone was incubated with 500 ng of WT T antigen (A) or the molar equivalent of 246-708 (B) or 1-246 (C) in the presence of 1 mM ethidium bromide. The beads were then washed and resuspended in electrophoresis sample buffer. Samples were loaded onto 10% acrylamide gels. The proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose, and the T-antigen polypeptides were detected with PAb101 (A and B) or PAb419 (C) in a Western blot assay. A small amount of WT T antigen and 246-708 was also added directly to the gels to serve as markers (last lanes).

We have previously demonstrated that the binding between T antigen and topo I under physiological conditions is highly specific (14). topo I bound to T antigen only when the viral protein was associated with SV40 origin DNA in the form of double hexamers. No binding was detected with smaller oligomeric forms of T antigen such as single hexamers. These observations imply that the binding observed between these proteins under the in vitro conditions used here (e.g., ELISAs and GST-binding assays) is not physiological. Therefore, we sought to determine whether the binding site identified above is a true binding site that would function under DNA replication conditions. To investigate this question, we incubated WT T antigen, origin DNA, and various GST-topo I mutants under replication conditions as described by Gai et al. (14). The origin DNA used was a 388-bp fragment of SV40 DNA encompassing the origin and circularized by hybridizing a double-stranded oligonucleotide linker as described previously (14). The protein-DNA complexes that formed were cross-linked with glutaraldehyde and applied to a composite polyacrylamide agarose gel. After electrophoresis, the complexes were transferred to nitrocellulose, and the topo I detected by reactivity with an anti-GST antibody. When topo 17, B7, A2, or D26 was used, there was no difference between the protein bands that formed in the presence or absence of T antigen (Fig. 4). However, a band corresponding to the position of double hexamers was detected with topo 70 and topo 31 in the presence of T antigen but not in its absence (the faint band in the topo 31 −T lane is further up on the gel and must represent a background topo 31-DNA complex). Therefore, only topo 70 and topo 31 bound to double hexamers. These data support the conclusion that the T-antigen-binding site is located within topo 31. The failure of topo 17, B7, and D26 to bind to WT T antigen under these conditions indicates that binding is dependent on an intact topo 31 domain structure.

FIG. 4.

Origin DNA-binding assay with various topo I fragments. A total of 100 ng of GST-tagged topo 70 or the molar equivalent of various topo deletion mutants was incubated with 5 ng of circular origin DNA in the presence or absence of 400 ng of WT T antigen under replication conditions. After cross-linking, the samples were subjected to electrophoresis in a composite acrylamide agarose gel, and the protein complexes were transferred to nitrocellulose. topo I polypeptides were detected by reactivity with an anti-GST antibody in a Western blot assay. The positions of double hexamers (DH) are indicated and were determined by probing the same blots with an anti-T antibody (not shown).

Mapping of the N-terminal binding site on T antigen.

Our previous data indicated that the N-terminal binding site on T antigen is located between residues 1 and 246 (35). To map this site more closely, we generated a series of N-terminal T-antigen constructs (Fig. 5) and purified the deletion mutants by immunoaffinity chromatography by using an appropriate monoclonal antibody. ELISAs measuring the binding between full-length topo I and these T antigen mutants are shown in Fig. 6. All T-antigen constructs bound to topo I with the apparent exception of 1-131. The apparent weaker binding of 83-246 to topo I is probably due to lower stability of this fragment since only small amounts were purified. Since mutants 83-246 and 1-160 bound topo I, the N-terminal binding site for topo I appears to be located between residues 83 and 160.

FIG. 5.

(Top) Map of T antigen polypeptides used in this study. All of these proteins were expressed in baculovirus-infected insect cells. Nontagged polypeptides were purified by immunoaffinity chromatography, and GST-tagged proteins were purified by binding to glutathione-Sepharose beads.

FIG.6.

(Bottom) ELISA between topo 70 and various N-terminal T antigen constructs. A total of 100 ng of topo 70 was first bound to microtiter plates. After a blocking step, various amounts of WT T antigen, as shown, or the molar equivalent of various N-terminal constructs of T antigen were added. After the wells were washed, PAb416 (which reacts with all T constructs used here) was added, followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. The absorbance at 490 nm was measured as described in Fig. 2. Controls without topo 70 were also performed for each T antigen construct, and these numbers were subtracted from the corresponding experimental numbers.

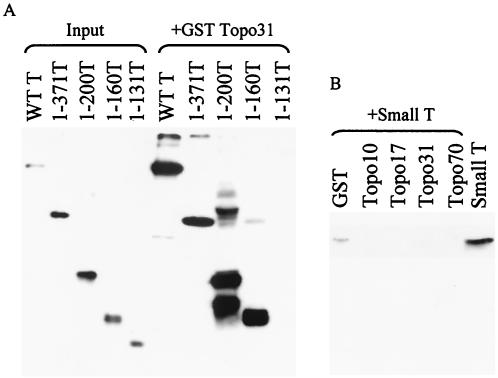

GST-binding assays were then performed to corroborate these findings (Fig. 7). Again, all N-terminal constructs except for 1-131 bound to GST-tagged topo 31 (Fig. 7A). Small T antigen (a gift of Kathy Rundell), which shares the first 82 amino acids with large T antigen, also did not bind (Fig. 7B). Therefore, the results of the ELISAs and GST-binding assays indicate that the N-terminal binding site on T antigen is located between residues 83 and 160 and that this site binds within topo 31 (residues 175 to 433).

FIG. 7.

GST-binding assay between topo 31 and N-terminal T-antigen polypeptides and between small T antigen and topo I constructs. (A) A 10-μl portion of beads containing 2.5 μg of topo 31 was incubated with 500 ng of WT T antigen or the molar equivalent of various N-terminal T antigen constructs. The beads were washed and resuspended in electrophoresis sample buffer, and the samples were applied to a 13% acrylamide gel. Detection of the T-antigen polypeptides was performed with PAb419, which binds to the N-terminal region of T antigen. Samples of all polypeptides were loaded onto the gel to serve as markers of the input material (lanes on left). (B) Portions (10 μl) of beads containing 18 μg of GST-tagged topo 70 or the molar equivalent of topo 31, topo 17, topo 10, or GST alone were incubated with 150 ng of small T antigen (a gift of Kathy Rundell). Bound proteins were applied to a 13% acrylamide gel, and small T antigen on the membrane was detected with PAb419. A sample of small T antigen was loaded directly in the last lane.

Mapping of the C-terminal binding site on T antigen.

The C-terminal binding site in T antigen exists between residues 246 and 708 (35). In an initial attempt to map this region more closely, we generated a series of internal deletion mutants of T antigen similar to those described by Kierstead and Tevethia with deletions extending up to residue 550 (21). These deletion mutants were made in a background of the C-terminal construct 246-708, which contains only one binding site. All of the internal deletion mutants tested bound in ELISAs and GST-binding assays (data not shown), indicating that this second binding site is located after residue 550. To probe this further, we made a series of untagged T-antigen proteins from the C-terminal region (Fig. 5), and these were tested for binding to GST-tagged topo 31 (Fig. 8). A peptide containing residues 423 to 708 bound well, a finding consistent with our initial findings that the topo I binding site is located between residues 550 and 708. Smaller untagged deletion mutants from the C-terminal region could not be made in stable form, and we therefore could not initially refine this map.

FIG. 8.

GST-binding assay between topo 31 and C-terminal T antigen constructs. A total of 10 μl of agarose beads containing 2.5 μg of GST-topo 31 was incubated with 500 ng of WT T antigen (A) or the molar equivalent of either 371-708 or 423-708 T-antigen polypeptides (B). Bound T-antigen proteins were detected by reactivity with PAb101, which binds to the C-terminal end of T antigen. Samples of the input proteins are shown as indicated.

To map the C-terminal site more closely, we turned to making GST-tagged T-antigen deletion mutants. Fortunately, these constructs were stably expressed in infected insect cells. GST pull-down assays (Fig. 9) showed that mutant 602-708 bound to WT topo I but that 636-708 did not bind any better than the GST control. Fragment 564-708 appeared to bind better to T antigen than fragment 602-708 in this experiment, but in others the binding was only slightly elevated. These data therefore indicate that the C-terminal binding site is present primarily within residues 602 to 708.

DISCUSSION

topo I binds to two sites on T antigen.

In an effort to more fully understand the molecular interactions that take place during the early phases of SV40 DNA replication, we mapped the sites in T antigen and topo I that bind to one another. The binding of these proteins to one another is an early event in DNA replication, and it is very likely that both proteins are components of the initiation complex (14, 44). We report here that there are two independent topo I binding sites on T antigen and that both sites interact with a region of topo I specified by topo 31 (residues 175 to 433). The two binding sites are near the N-terminal (residues 83 to 160) and C-terminal (residues 602 to 708) ends of T antigen. The N-terminal binding site contains a number of known features, including the nuclear localization signal and the retinoblastoma binding pocket, as well as the beginning of the origin binding domain (33). This region also contains a number of sites that, when phosphorylated, activate or inactivate DNA replication (33). We have previously reported that topo I binding does not interfere with the activity of the origin binding domain (36), but its effect on other activities is not known. The C-terminal binding site in T antigen also contains sites of phosphorylation (33), as well as a region whose C-terminal end is at residue 626 or 627 and that is required for structural integrity and stability of T antigen (H.-J. Lin and D. T. Simmons, unpublished results). Therefore, the C-terminal binding site is likely to extend to at least residue 626 but probably does not extend further than residue 670 since deletions from the C terminus to this point do not impair DNA replication (31).

Since physiologically relevant binding occurs only with double hexamers of T antigen, it is important to determine where these sites are located in the double hexamers. VanLoock et al. (48) have examined T-antigen double hexamers by electron microscopy, followed by three-dimensional reconstruction, and they report that the N-terminal and C-terminal ends of T antigen are localized to each end of individual hexamers. Hexamers are oriented relative to one another with either N-terminal or C-terminal domains facing each other, although it is not known if both are functional. Therefore, regardless of the orientation of the hexamers relative to each other, there would be a topo I binding site on each end of a double hexamer and potentially two binding sites in the middle. However, stoichiometry analyses (D. Gai and D. T. Simmons, unpublished results) shows that only two molecules of topo I are present in the complex per double hexamer. To ensure that there is a molecule of topo I in close proximity to each replication fork during DNA unwinding, we propose that topo I is positioned on the outside of the double hexamer (Fig. 10A). Accordingly, one molecule of topo I would be associated close to each end of double hexamers during the process of unwinding the DNA, notwithstanding the hexamer-hexamer orientation (Fig. 10A).

FIG. 10.

(A) Model of topo I associated with a T-antigen double hexamer. This model is based on the data presented by VanLoock et al. (48) and Valle et al. (47). Each hexamer of T antigen consists of three domains: an N-terminal DNA-binding domain, a central helicase domain, and a C-terminal domain. The hexamers are oriented either with their C-terminal domains facing each other (model on left) or with the N-terminal domains facing one another (model on right). topo I is shown binding to the N-terminal domains on left or to the C-terminal domains on right. (B) topo 31 is a distinct domain of topo I. This illustration is based on the topo 70 crystal structure by Rebindo et al. (32) and Stewart et al. (43) (pdb entry 1a36). The topo 31 domain (the cap region) is shown below the DNA.

topo I domain that interacts with T antigen.

Topo 31 is a distinct domain in the three-dimensional structure of topo I (32, 43) (Fig. 10B). Since the regions of T antigen with which it interacts are completely different in sequence and presumably in structure, it is likely that different portions of topo 31, also known as the cap region (53), are involved. The binding of T antigen to this region should not interfere with the catalytic domain that is located in the section of the protein shown above the DNA in Fig. 10B. However, the cap region is required for nicking DNA (but not for the religation step) during catalysis (53) and, therefore, T antigen must not be blocking the cap region's ability to participate in the nicking reaction needed to relax supercoiled DNA.

Preliminary data from our lab (data not shown) indicate that DNA length is a factor in the recruitment of topo I in the context of the double hexamer. This suggests to us that some of the topo I may be recruited by first binding to the DNA before locking into position on T antigen. Therefore, depending on the orientation of the hexamers, topo I would attach to the N-terminal or C-terminal domain of T antigen. It would make sense if topo I itself faces T antigen differently in each case so that different surfaces of the cap region make contact with T antigen. Interestingly, since partially assembled double hexamers do not stably bind topo I (14), fully formed double hexamers must undergo a structural rearrangement at both ends in order to accommodate topo I.

Protein-protein interactions during DNA replication.

Our data have further implications for protein-protein interactions during SV40 DNA replication. In the VanLoock structure, the regions of the DNA-binding domain that make direct contacts with the DNA are located on the inside of the channel formed by each hexamer. These regions correspond to residues 151 to 160 and residues 210 to 215 (34, 37, 38). In order for topo I to bind to the N-terminal site on T antigen, it would most likely have to bind to regions exposed on the outside of the hexamer, probably corresponding to residues 83 to 140, based on the nuclear magnetic resonance structure of the DNA-binding domain (25) and on the structure of residues 7 to 117 (22). In the double-hexamer reconstructions (48), this region lies close to but not right at the end. Information is available about the binding sites of the other two cellular proteins (RPA and pol/prim) needed for initiation of DNA replication. The RPA binding site has been mapped to residues 164 to 249 on T antigen (50). This turns out to be immediately adjacent to the topo I binding site and also within the N-terminal domain in the T-antigen hexamer. These two cellular proteins may therefore be in close proximity on the surface of the hexamer and may well interact with one another. The binding site for DNA polymerase appears to be between residues 195 and 313 (8), a region that would overlap with the N-terminal and central helicase domains of each hexamer (see Fig. 10A) (48). Since DNA polymerase and RPA are known to interact with one another (5, 9, 29), the binding of these two cellular proteins to T antigen might place them at the correct distance from each other so they could interact with one another and also permit the association of topo I with the N-terminal binding region. On the other hand, binding of topo I to the C-terminal domain of T antigen would place it at some distance from the other cellular proteins. However, it is this interaction that is likely to be the more functionally significant one because the arrangement of the two hexamers with the N-terminal domains facing one another is the more probable orientation given the structural architecture of the SV40 origin. If this is true, it remains to be determined whether the N-terminal binding site has any function in this particular hexamer-hexamer orientation. One possibility is that it is used to facilitate the recruitment of topo I to generate initiation complexes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant CA36118 to D.T.S. from the National Cancer Institute and grant GM60330 to J.J.C. from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Borowiec, J. A. 1992. Inhibition of structural changes in the simian virus 40 core origin of replication by mutation of essential origin sequences. J. Virol. 66:5248-5255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borowiec, J. A., F. B. Dean, P. A. Bullock, and J. Hurwitz. 1990. Binding and unwinding: how T antigen engages the SV40 origin of DNA replication. Cell 60:181-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borowiec, J. A., F. B. Dean, and J. Hurwitz. 1991. Differential induction of structural changes in the simian virus 40 origin of replication by T antigen. J. Virol. 65:1228-1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borowiec, J. A., and J. Hurwitz. 1988. Localized melting and structural changes in the SV40 origin of replication induced by T-antigen. EMBO J. 7:3149-3158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braun, K. A., Y. Lao, Z. He, C. J. Ingles, and M. S. Wold. 1997. Role of protein-protein interactions in the function of replication protein A (RPA): RPA modulates the activity of DNA polymerase alpha by multiple mechanisms. Biochemistry 36:8443-8454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dean, F. B., J. A. Borowiec, T. Eki, and J. Hurwitz. 1992. The simian virus 40 T antigen double hexamer assembles around the DNA at the replication origin. J. Biol. Chem. 267:14129-14137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dean, F. B., and J. Hurwitz. 1991. Simian virus 40 large T antigen untwists DNA at the origin of DNA replication. J. Biol. Chem. 266:5062-5071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dornreiter, I., W. C. Copeland, and T. S. Wang. 1993. Initiation of simian virus 40 DNA replication requires the interaction of a specific domain of human DNA polymerase alpha with large T antigen. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:809-820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dornreiter, I., L. F. Erdile, I. U. Gilbert, D. von Winkler, T. J. Kelly, and E. Fanning. 1992. Interaction of DNA polymerase alpha-primase with cellular replication protein A and SV40 T antigen. EMBO J. 11:769-776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eki, T., and J. Hurwitz. 1991. Influence of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase on the enzymatic synthesis of SV40 DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 266:3087-3100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eki, T., T. Matsumoto, Y. Murakami, and J. Hurwitz. 1992. The replication of DNA containing the simian virus 40 origin by the monopolymerase and dipolymerase systems. J. Biol. Chem. 267:7284-7294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fairman, M. P., G. Prelich, and B. Stillman. 1987. Identification of multiple cellular factors required for SV40 replication in vitro. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 317:495-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fairman, M. P., and B. Stillman. 1988. Cellular factors required for multiple stages of SV40 DNA replication in vitro. EMBO J. 7:1211-1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gai, D., R. Roy, C. Wu, and D. T. Simmons. 2000. Topoisomerase I associates specifically with simian virus 40 large-T-antigen double hexamer-origin complexes. J. Virol. 74:5224-5232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gurney, E. G., R. O. Harrison, and J. Fenno. 1980. Monoclonal antibodies against simian virus 40 T antigens: evidence for distinct subclasses of large T antigen and for similarities among nonviral T antigens. J. Virol. 34:752-763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haluska, P., Jr., A. Saleem, T. K. Edwards, and E. H. Rubin. 1998. Interaction between the N terminus of human topoisomerase I and SV40 large T antigen. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:1841-1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harlow, E., L. V. Crawford, D. C. Pim, and N. M. Williamson. 1981. Monoclonal antibodies specific for simian virus 40 tumor antigen. J. Virol. 39:861-869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herbig, U., K. Weisshart, P. Taneja, and E. Fanning. 1999. Interaction of the transcription factor TFIID with simian virus 40 (SV40) large T antigen interferes with replication of SV40 DNA in vitro. J. Virol. 73:1099-1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang, S. G., K. Weisshart, I. Gilbert, and E. Fanning. 1998. Stoichiometry and mechanism of assembly of SV40 T antigen complexes with the viral origin of DNA replication and DNA polymerase alpha-primase. Biochemistry 37:15345-15352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishimi, Y., A. Claude, P. Bullock, and J. Hurwitz. 1988. Complete enzymatic synthesis of DNA containing the SV40 origin of replication. J. Biol. Chem. 263:19723-19733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kierstead, T. D., and M. J. Tevethia. 1993. Association of p53 binding and immortalization of primary C57BL/6 mouse embryo fibroblasts by using simian virus 40 T-antigen mutants bearing internal overlapping deletion mutations. J. Virol. 67:1817-1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim, H. Y., B. Y. Ahn, and Y. Cho. 2001. Structural basis for the inactivation of retinoblastoma tumor suppressor by SV40 large T antigen. EMBO J. 20:295-304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lai, J.-S., and W. Herr. 1992. Ethidium bromide provides a simple tool for dentifying genuine DNA-independent protein associations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:6958-6962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee, S. H., Y. Ishimi, M. K. Kenny, P. Bullock, F. B. Dean, and J. Hurwitz. 1988. An inhibitor of the in vitro elongation reaction of simian virus 40 DNA replication is overcome by proliferating-cell nuclear antigen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:9469-9473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luo, X., D. G. Sanford, P. A. Bullock, and W. W. Bachovchin. 1996. Solution structure of the origin DNA-binding domain of SV40 T-antigen. Nat. Struct. Biol. 3:1034-1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madden, K. R., L. Stewart, and J. J. Champoux. 1995. Preferential binding of human topoisomerase I to superhelical DNA. EMBO J. 14:5399-5409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsumoto, T., T. Eki, and J. Hurwitz. 1990. Studies on the initiation and elongation reactions in the simian virus 40 DNA replication system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:9712-9716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melendy, T., and B. Stillman. 1991. Purification of DNA polymerase delta as an essential simian virus 40 DNA replication factor. J. Biol. Chem. 266:1942-1949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nasheuer, H. P., D. von Winkler, C. Schneider, I. Dornreiter, I. Gilbert, and E. Fanning. 1992. Purification and functional characterization of bovine RP-A in an in vitro SV40 DNA replication system. Chromosoma 102:S52-S59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parsons, R., M. E. Anderson, and P. Tegtmeyer. 1990. Three domains in the simian virus 40 core origin orchestrate the binding, melting, and DNA helicase activities of T antigen. J. Virol. 64:509-518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pipas, J. M. 1985. Mutations near the carboxyl terminus of the simian virus 40 large tumor antigen alter viral host range. J. Virol. 54:569-575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Redinbo, M. R., L. Stewart, P. Kuhn, J. J. Champoux, and W. G. Hol. 1998. Crystal structures of human topoisomerase I in covalent and noncovalent complexes with DNA. Science 279:1504-1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simmons, D. T. 2000. SV40 large T antigen: functions in DNA replication and transformation. Adv. Virus Res. 55:75-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simmons, D. T., G. Loeber, and P. Tegtmeyer. 1990. Four major sequence elements of simian virus 40 large T antigen coordinate its specific and nonspecific DNA binding. J. Virol. 64:1973-1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simmons, D. T., T. Melendy, D. Usher, and B. Stillman. 1996. Simian virus 40 large T antigen binds to topoisomerase I. Virology 222:365-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simmons, D. T., P. W. Trowbridge, and R. Roy. 1998. Topoisomerase I stimulates SV40 T antigen-mediated DNA replication and inhibits T antigen's ability to unwind DNA at nonorigin sites. Virology 242:435-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simmons, D. T., R. Upson, K. Wun-Kim, and W. Young. 1993. Biochemical analysis of mutants with changes in the origin-binding domain of simian virus 40 tumor antigen. J. Virol. 67:4227-4236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simmons, D. T., K. Wun-Kim, and W. Young. 1990. Identification of simian virus 40 T antigen residues important for specific and nonspecific binding to DNA and for helicase activity. J. Virol. 64:4858-4865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smelkova, N. V., and J. A. Borowiec. 1997. Dimerization of simian virus 40 T-antigen hexamers activates T-antigen DNA helicase activity. J. Virol. 71:8766-8773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stewart, L., G. C. Ireton, and J. J. Champoux. 1996. The domain organization of human topoisomerase I. J. Biol. Chem. 271:7602-7608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stewart, L., G. C. Ireton, and J. J. Champoux. 1997. Reconstitution of human topoisomerase I by fragment complementation. J. Mol. Biol. 269:355-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stewart, L., G. C. Ireton, L. H. Parker, K. R. Madden, and J. J. Champoux. 1996. Biochemical and biophysical analyses of recombinant forms of human topoisomerase I. J. Biol. Chem. 271:7593-7601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stewart, L., M. R. Redinbo, X. Qiu, W. G. Hol, and J. J. Champoux. 1998. A model for the mechanism of human topoisomerase I. Science 279:1534-1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trowbridge, P. W., R. Roy, and D. T. Simmons. 1999. Human topoisomerase I promotes initiation of simian virus 40 DNA replication in vitro. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:1686-1694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsurimoto, T., and B. Stillman. 1990. Functions of replication factor C and proliferating-cell nuclear antigen: functional similarity of DNA polymerase accessory proteins from human cells and bacteriophage T4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:1023-1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uhlmann-Schiffler, H., S. Seinsoth, and H. Stahl. 2002. Preformed hexamers of SV40 T antigen are active in RNA and origin-DNA unwinding. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:3192-3201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Valle, M., C. Gruss, L. Halmer, J. M. Carazo, and L. E. Donate. 2000. Large T-antigen double hexamers imaged at the simian virus 40 origin of replication. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:34-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.VanLoock, M. S., A. Alexandrov, X. Yu, N. R. Cozzarelli, and E. H. Egelman. 2002. SV40 large T antigen hexamer structure: domain organization and DNA-induced conformational changes. Curr. Biol. 12:472-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weinberg, D. H., K. L. Collins, P. Simancek, A. Russo, M. S. Wold, D. M. Virshup, and T. J. Kelly. 1990. Reconstitution of simian virus 40 DNA replication with purified proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:8692-8696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weisshart, K., P. Taneja, and E. Fanning. 1998. The replication protein A binding site in simian virus 40 (SV40) T antigen and its role in the initial steps of SV40 DNA replication. J. Virol. 72:9771-9781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wobbe, C. R., L. Weissbach, J. A. Borowiec, F. B. Dean, Y. Murakami, P. Bullock, and J. Hurwitz. 1987. Replication of simian virus 40 origin-containing DNA in vitro with purified proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:1834-1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wold, M. S., D. H. Weinberg, D. M. Virshup, J. J. Li, and T. J. Kelly. 1989. Identification of cellular proteins required for simian virus 40 DNA replication. J. Biol. Chem. 264:2801-2809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang, Z., and J. J. Champoux. 2002. Reconstitution of enzymatic activity by the association of the cap and catalytic domains of human topoisomerase I. J. Biol. Chem. 277:30815-30823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]