Abstract

The aspartic protease cathepsin D (cath-D) is a key mediator of induced-apoptosis and its proteolytic activity has been generally involved in this event. During apoptosis, cath-D is translocated to the cytosol. Since cath-D is one of the lysosomal enzymes which requires a more acidic pH to be proteolytically-active relative to the cysteine lysosomal enzymes such as cath-B and -L, it is therefore open to question whether cytosolic cath-D might be able to cleave substrate(s) implicated in the apoptotic cascade. Here we have investigated the role of wild-type cath-D and its proteolytically-inactive counterpart over-expressed by 3Y1-Ad12 cancer cells during chemotherapeutic-induced cytotoxicity and apoptosis, as well as the relevance of cath-D catalytic function. We demonstrate that wild-type or mutated catalytically-inactive cath-D strongly enhances chemo-sensitivity and apoptotic response to etoposide. Both wild-type and mutated inactive cath-D are translocated to the cytosol, increasing the release of cytochrome c, the activation of caspases-9 and -3 and the induction of a caspase-dependent apoptosis. In addition, pre-treatment of cells with the aspartic protease inhibitor, pepstatin A, does not prevent apoptosis. Interestingly therefore, the stimulatory effect of cath-D on cell death is independent of its catalytic activity. Overall, our results imply that cytosolic cath-D stimulates apoptotic pathways by interacting with a member of the apoptotic machinery rather than by cleaving specific substrate(s).

Keywords: Antineoplastic Agents; pharmacology; Apoptosis; Caspase 3; Caspase 9; Caspases; metabolism; Cathepsin D; biosynthesis; Cytosol; chemistry; Drug Resistance, Neoplasm; Enzyme Activation; Humans; Tumor Cells, Cultured

Keywords: protease, cathepsin D, chemo-cytotoxicity, apoptosis, etoposide, catalytic activity

INTRODUCTION, RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Cathepsin D (cath-D) (EC 3.4.23.5) is a ubiquitous lysosomal aspartic protease extensively reported as being an active player in breast cancer (Rochefort, 1996; Garcia et al., 1990; Liaudet et al., 1994; Glondu et al., 2001; Glondu et al., 2002; Berchem et al., 2002; Laurent-Matha et al., 2005). More recently, cath-D has also been discovered as a key mediator of apoptosis induced by many apoptotic agents such as IFN-gamma, Fas/APO, TNF-alpha (Deiss et al., 1996), oxidative stress (Roberg and Öllinger, 1998; Öllinger, 2000; Roberg, 2001; Kagedal et al., 2001; Takuma et al., 2003), adriamycin and etoposide (Wu et al., 1998; Emert-Sedlak et al., 2005), as well as staurosporine (Johansson et al., 2003). The role of cath-D in apoptosis has been linked to the lysosomal release of mature 34 kDa cath-D into the cytosol leading in turn to the mitochondrial release of cytochrome c (cyt c) into the cytosol (Roberg and Öllinger, 1998; Öllinger, 2000; Kagedal et al., 2001; Roberg, 2001; Roberg et al., 2002; Johansson et al., 2003), activation of pro-caspases (Öllinger, 2000; Roberg et al., 2002; Johansson et al., 2003; Heinrich et al., 2004), in vitro cleavage of Bid at pH 6.2 (Heinrich et al., 2004), or Bax activation independently of Bid cleavage (Bidère et al., 2003).

Numerous studies have shown that pepstatin A, an aspartic protease inhibitor, could partially delay apoptosis induced by IFN-gamma and Fas/APO (Deiss et al., 1996), staurosporine (Terman et al., 2002; Bidère et al., 2003; Johansson et al., 2003), TNF-alpha (Deiss et al., 1996; Demoz et al., 2002; Heinrich et al., 2004), serum deprivation (Shibata et al., 1998), oxidative stress (Öllinger, 2000; Roberg, 2001; Kagedal et al., 2001; Takuma et al., 2003) or even when cath-D was micro-injected (Roberg et al., 2002). These authors have thus concluded that cath-D plays a key role in apoptosis mediated via its catalytic activity.

However, cath-D is one of the lysosomal enzymes which requires a more acidic pH to be proteolytically active, relative to the cysteine lysosomal enzymes such as cath-B and -L. Acidification of the cytosol down to pH values of about 6.7–7 is a well-documented phenomenon in apoptosis (Gottlieb et al., 1996; Matsuyama et al., 2000). In vitro cath-D can cleave its substrates up to a pH of 6.2, but not above (Capony et al., 1987). Hence, it is predictable that the proteolytic activity of cytosolic cath-D would be drastically impaired under adverse pH conditions unfavourable for its catalytic function. It is therefore open to question whether cath-D might be able to cleave cytosolic substrate(s) implicated in the apoptotic cascade. In accordance with this proposal, it was recently described that pepstatin A did not prevent the death of cells treated by etoposide, doxorubicin, anti-CD95 or TNF-alpha (Demoz et al., 2002; Tardy et al., 2003; Emert-Sedlak et al., 2005). Furthermore, pepstatin A did not suppress Bid cleavage or pro-caspases-9 and -3 activation by photodynamic therapy in murine hepatoma cells (Reiners et al., 2002). Finally, deficiency in cath-D activity did not alter cell death induction in CONCL fibroblasts (Tardy et al., 2003). In this latter study, Tardy and colleagues discussed the possibility that catalytically-inactive cath-D might well be implicated in apoptosis (Tardy et al., 2003).

In the present paper, we have investigated the role of wild-type cath-D and its proteolytically-inactive counterpart over-expressed by cancer cells in chemotherapeutic-induced cytotoxicity and apoptosis, and more precisely the relevance of cath-D catalytic function. We used the 3Y1-Ad12 cancer cell line - stably transfected with either wild-type cath-D or catalytically-inactive D231Ncath-D or an empty vector - as a tumor model of cath-D over-expression (Glondu et al., 2001). Cath-D, D231Ncath-D and mock-transfected (control) 3Y1-Ad12 transfected cell lines were first treated with increasing concentrations of the topoisomerase ll-inhibitor etoposide for two doubling time (e.g. 4 days) (Figure 1). Cell viability curves revealed that cath-D significantly enhanced (5-fold) the chemo-sensitivity of cancer cells exposed to etoposide concentrations ranging from 100 nM to 1 μM, compared to control cells. Interestingly, D231Ncath-D provided the same decrease in viability as cath-D (Figure 1). Similar data were obtained with the DNA intercalator doxorubicin and the anti-metabolite 5-fluorouracil (data not shown). We therefore conclude that cath-D over-expressed by cancer cells increases their cytotoxic responses to chemotherapeutic agents independently of its catalytic activity. Since many reported clinical studies have associated cath-D over-expression with an increased risk of clinical metastasis and shorter survival in breast cancer patients (Rochefort, 1996; Ferrandina et al., 1997; Foekens et al., 1999; Westley and May, 1996), our results appear strongly to support the hypothesis that patients with breast cancer over-expressing cath-D might be more receptive to chemotherapeutic treatment.

Figure 1. The over-expression of both catalytically-active and -inactive cath-D by 3Y1-Ad12 cancer cells enhances etoposide-induced cytotoxicity.

Control, cath-D and D231Ncath-D transfected 3Y1-Ad12 cancer cells were either left untreated or were treated with increasing concentrations of etoposide (Sigma) for 4 days after which cell survival was evaluated by the mitochondrial deshydrogenase enzymatic assay, using 3(4,5-dimethyl-thiazol-2-yl)2,5-diphenol tetrazolium bromide (MTT, Sigma) and determination of OD540nm. Mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate. *, p<0.0005 versus control cells (Student’s t-test).

To dissect out the mechanism involved, we first determined whether chemo-sensitivity induced by over-expressed cath-D might be the consequence of an enhancement of apoptosis. Control, cath-D and D231Ncath-D cancer cells were first treated with 10 μM etoposide and their nuclei were stained with DAPI (Figure 2A). Cancer cells over-expressing wild-type cath-D or D231Ncath-D exhibited characteristic apoptotic morphological features, such as cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation, and the formation of apoptotic bodies, whereas control cancer cells presented only few apoptotic nuclei (Figure 2A). Control, cath-D and D231Ncath-D cancer cells were then treated with increasing low (Figure 2B, left panel) or higher (Figure 2B, right panel) concentrations of etoposide for 24 h and apoptotic status was analysed by an ELISA that detects histories associated with fragmented DNA. Both wild-type cath-D and D231Ncath-D enhanced apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2B). A 3-fold increase in apoptosis was observed with 1 μM etoposide in cath-D and D231Ncath-D cells, compared to control cells (Figure 2B, left panel). Similar results were obtained over a wide range of etoposide concentrations, indicating that cath-D increased apoptosis for a large scale of etoposide treatment, e.g. from 75 nM to 50 μM (Figure 2B). We finally examined the DMA fragmentation by TUNEL staining in cell cultures treated with 10 μM etoposide and found that the nuclei of the cath-D and D231Ncath-D transfected cells were positively stained by TUNEL, whereas almost no TUNEL-positive cells were seen in control cells (Figure 2C, top panel). Quantification of the TUNEL assay, performed with cells treated with either 1 or 10 μM etoposide, then revealed a significant (10–30 fold) increase of apoptosis in both cath-D and D231Ncath-D cells, compared to control cells (Figure 2C, bottom panel). Moreover, pre-treatment of wild-type cath-D cells with 100 μM pepstatin A did not inhibit the increase of apoptosis induced by cath-D (Figure 2D, left panel). Furthermore, pepstatin A had no effect on apoptosis enhanced by catalytically-inactive D231Ncath-D (Figure 2D, left panel). Time-course experiments of cath-D cells pre-treated with pepstatin A confirmed the inefficiency of this aspartic protease inhibitor to reverse cath-D-induced apoptosis (Figure 2D, right panel). We verified that cath-D catalytic activity was inhibited by 100 μM pepstatin A in cath-D cell extracts from untreated or etoposide-treated cells (Figure 2E). Overall, our results demonstrate that cath-D over-expressed by cancer cells enhances etoposide-induced apoptosis independently of its catalytic activity.

Figure 2. Catalytically-active and -inactive cath-D amplify etoposide-induced apoptosis.

(A) Staining of nuclei. Cells were treated with 10 μM etoposide for 24 h and nuclei were stained with 0.5 μg/ml DAPI (Sigma). Arrows indicate condensed chromatin and apoptotic bodies. Insets show DMA condensation and apoptotic bodies at a higher magnification. Bars, 23 μm.

(B) ELISA apoptosis. Cells were either left untreated or were treated with increasing concentrations of etoposide for 24 h at either low doses (left panel) or higher doses (right panel). Apoptosis induction was quantified on pooled floating and adherent cells using a cell death ELISA (Cell Death Detection ELISA, Roche Diagnostics).

(C) TUNEL assay. Representative immuno-cytochemistry of apoptotic cells obtained after exposure to 10 μM etoposide for 24 h (top panel). Apoptosis was analysed on adherent cells and floating cells cytospun on glass slides using the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated FITC-dUTP nick-end labelling (TUNEL) method (In situ Cell Death Detection Kit, Fluorescein; Roche Diagnostics). Inset shows apoptotic bodies. For quantification of apoptotic cells (bottom panel), three fields for each experimental condition were chosen by random sampling and the total number of cells and the number of TUNEL positive nuclei were counted from adherent and cytospun floating cells. The results are expressed as a % of the estimated total number of cells present in the field. *, p<0.01, **, p<0.025 and ***, p<0.0025 versus control cells (t-test). Bars, 69 μm.

(D) Effect of pepstatin A on cath-D-induced apoptosis. Cath-D or D231Ncath-D cells were either left untreated or were pre-treated for 16 h with 100 μM pepstatin A (Sigma) and then were either untreated or treated with 10 μM etoposide for 24 h (left panel). Apoptotic status was quantified as described in panel C. NS (non significant), p<0.1 and 0.15 versus etoposide for cath-D and D231Ncath-D cells, respectively (t-test). Time-course analysis of apoptosis in the presence or absence of 100 μM pepstatin A was performed with cath-D cells as described in the left panel (right panel). NS (non significant), p<0.25 versus etoposide (t-test).

(E) Effect of pepstatin A on cath-D catalytic activity. Cath-D proteolytic activity was analysed in cath-D cell extracts untreated or treated with 10 μM etoposide for 24 h using a fluorogenic cath-D substrate (Calbiochem, #219360) in the presence or absence of 100 μM pepstatin A.

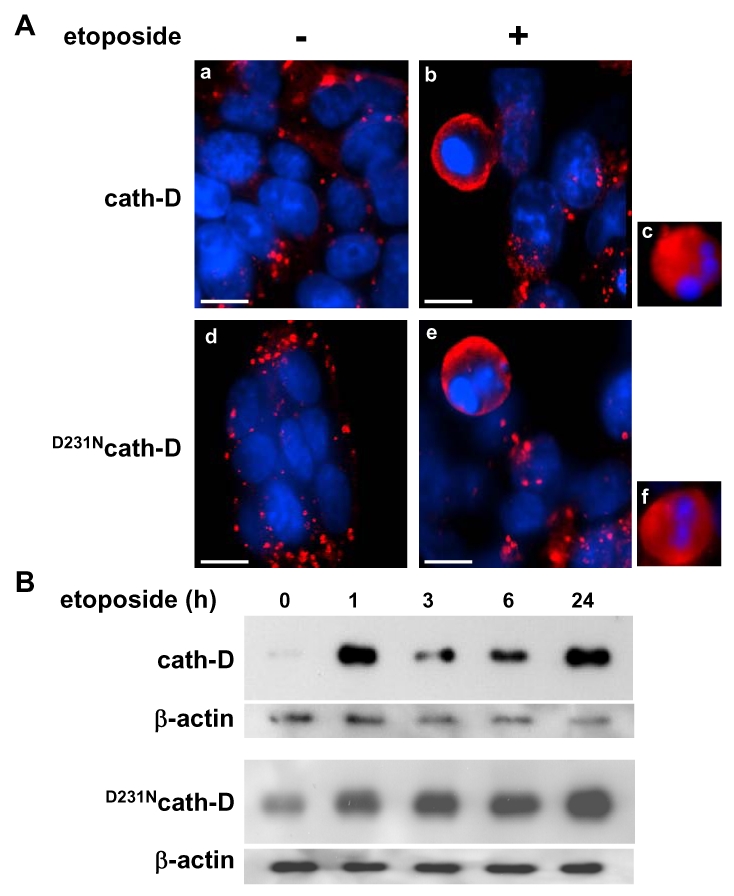

Cath-D has been described as being readily translocated to the cytosol in response to various apoptotic stimuli (Kagedal et al., 2001; Roberg, 2001; Johansson et al., 2003; Bidère et al., 2003; Heinrich et al., 2004; Emert-Sedlak et al., 2005). We therefore investigated the subcellular distribution of wild-type and D231Ncath-D by immunostaining (Figure 3A) and by cell fractionation (Figure 3B). In untreated cath-D or D231Ncath-D cells, immunostaining of cath-D displayed a punctuate distribution using immunofluorescence microscopy, consistent with a lysosomal location (Figure 3A). By contrast, in etoposide-treated cath-D or D231Ncath-D cells, cath-D displayed a mixed punctuate/diffuse distribution, suggesting that a portion of it was released from lysosomes into the cytosol (Figure 3A). Western blot analysis confirmed that the mature (34 kDa) form of cath-D was indeed present in the cytosolic fractions obtained from wild-type cath-D or D231Ncath-D cells treated for 1 h with etoposide, following permeabilization of the plasma membranes with digitonin (Figure 3B). The cytosol-lysosome pH gradient seemed to be preserved in etoposide-treated cells because LysoTracker-Red, an acidic organelle-specific probe, still accumulated in granular cellular structures (data not shown).

Figure 3. Catalytically-active and -inactive cath-D are released early in etoposide-induced apoptosis.

(A) Immunofluorescence of cath-D. Cath-D or D231Ncath-D cells were either exposed to 10 μM etoposide for 24 h (b, c, e, f) or left untreated (a, d). Note the granular staining in the untreated cells (a, d) and the diffuse staining in cells exposed to etoposide (b, c, e, f). Cells were incubated first with anti-human cath-D M1G8 mouse monoclonal antibody at 2.5 μg/ml (Cis Bio International, Gif-sur-Yvette, France) followed by a RITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (dilution 1/50; Immunotech), as previously described (Liaudet et al., 1994). Bars, 7.4 μm.

(B) Release of cytosolic cath-D. Western blotting of wild-type cath-D (top panel) and D231Ncath-D (bottom panel) in cytosols extracted from cells either exposed to 10 μM etoposide for indicated periods of time or left untreated. Cytosol was extracted using 20 μg/ml and 45 μg/ml digitonin (Fluka) for cath-D and D231Ncath-D cells, respectively, for 10 min as previously described (Johansson et al., 2003). Cath-D immunoblotting was performed using an anti-human cath-D monoclonal mouse antibody (1 μg/ml; #610800, BD PharMingen) followed by an anti-mouse peroxidase-conjugated antibody (dilution 1/4000; Amersham Biosciences). An anti-beta-actin (Sigma) was used as a control for protein loading.

Cyt c has been shown to be released from mitochondria to the cytosol during etoposide-induced apoptosis (Sawada et al., 2000). A typical mitochondrial pattern was observed by immunofluorescence analysis of cyt c in untreated control, cath-D or D231Ncath-D cells, as well as in control cells treated with 10 μM etoposide (Figure 4A). By contrast, in cath-D or D231Ncath-D cells exposed to 10 μM etoposide, translocation of cyt c from the mitochondria into the cytosol was observed (Figure 4A). These results indicate that cath-D over-expressed by cancer cells contributes to mitochondrial cyt c release in etoposide-treated cells independently of its catalytic function.

Figure 4. Catalytically-active and -inactive cath-D induce mitochondrial release of cyt c and activation of caspases-9 and -3.

(A) Cyt c release. Cells were exposed to 10 μM etoposide for 24 h and cyt c was analyzed by immunofluorescence using an anti-rat cyt c mouse monoclonal antibody (dilution 1/50; #556432, BD PharMingen) followed by a RITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (dilution 1/50; Immunotech) as previously described (Johansson et al.,2003). Bars, 16 μm.

(B) Activation of caspases-9 and -3. Cells were exposed to 10 μM etoposide for 24 h and activation of caspase-9 and -3 was analyzed by immunofluorescence using respectively an anti-rat cleaved caspase-9 rabbit polyclonal antibody (dilution 1/50; #9507, Cell Signaling) or an anti-rat cleaved caspase-3 rabbit polyclonal antibody (dilution 1/50; #9661, Cell Signaling) followed by a TexasRed-conjugated or FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (dilution 1/100; Jackson Immunoresearch). Bars, 43 μm.

We then investigated whether cath-D plays a role in the activation of caspases-9 and -3 since these caspases have been shown to play a pivotal role in etoposide-induced apoptosis (Sawada et al., 2000). As illustrated in Figure 4B, caspases-9 and -3 were both activated in cath-D and D231Ncath-D cells treated with 10 μM etoposide whereas almost no signal could be detected in control cells in similar conditions. To confirm that cath-D participates in the activation of caspases during etoposide-induced apoptosis, cath-D or D231Ncath-D were either left untreated or pre-treated first with the general caspase inhibitor, Z-VAD-FMK, and then with 10 & mu;M etoposide (Figure 5A). TUNEL assays revealed that wild-type or D231Ncath-D enhanced a caspase-dependent apoptosis since etoposide-induced apoptosis was significantly inhibited by Z-VAD-FMK treatment (Figure 5A). In parallel experiments, we verified that Z-VAD-FMK efficiently inhibited caspase-3 activation in our cells (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Catalytically-active and -inactive cath-D increase caspase-dependent apoptosis.

(A) Effect of Z-VAD-FMK on apoptosis. Cath-D (top panel) and D231Ncath-D (bottom panel) cells were first either pre-treated for 1 h with 100 μM Z-VAD-FMK (Calbiochem) or left untreated and were then either left untreated again or were treated with 10 μM etoposide for 24 h. Apoptotic status was analysed and quantified as described in Figure 2C. Bars, 69 μm. *, p<0.05 and **, p<0.025 versus etoposide for cath-D and D231Ncath-D cells, respectively (t-test).

(B) Effect of Z-VAD-FMK on caspase-3 activation. Cath-D cells were either left untreated or were pre-treated for 1 h with 100 μM Z-VAD-FMK (Calbiochem) and were then either left untreated again or were treated with 10 μM etoposide for 24 h. Caspase-3 activation was analysed and quantified as described in Figures 4B and 2C, respectively. Bars, 69 μm. *, p<0.0025 versus etoposide treatment (t-test).

Overall, our study has demonstrated that the over-expression of both wild-type and D231cath-D by cancer cells can enhance the cytotoxicity of chemotherapeutic agents and their apoptotic response to etoposide treatment. Both active and inactive cath-D are rapidly released into the cytosol after etoposide treatment and this phenomenon is closely associated with cyt c release and caspase-dependent apoptotic events.

The function of cath-D in apoptosis is not yet fully understood and needs further investigation. Cath-D can either prevent apoptosis as described under physiological conditions with cath-D knock-out mice experiments (Saftig et al., 1995; Koike et al., 2000; Nakanishi et al., 2001; Koike et al., 2003), or can promote apoptosis induced by cytotoxic agents (Deiss et al., 1996; Wu et al., 1998; Roberg and Öllinger, 1998; Öllinger, 2000; Roberg, 2001; Kagedal et al., 2001; Takuma et al., 2003; Johansson et al., 2003; Emert-Sedlak et al., 2005). This duality in the role of cath-D in apoptosis is also highlighted by our apparently conflicting results obtained with transfected 3Y1-Ad12 cell lines. Indeed, we previously published that over-expressed cath-D was preventing tumor apoptosis in a manner dependent on its catalytic function in cath-D transfected 3Y1-Ad12 xenografts (Berchem et al., 2002). Intriguingly, the present study performed with the same cell lines, but treated this time with chemotherapeutic agents, indicates a stimulation of apoptosis independently of cath-D catalytic activity. It seems, therefore, that depending on the environmental conditions, cath-D may either inhibit or promote apoptosis via different mechanisms. This raises the possibility that this enzyme is involved in more than one apoptotic pathway.

However, since pro-apoptotic caspases are unlikely to be directly activated by lysosomal proteases (Cirman et al., 2004), a critical point in understanding the molecular mechanism of lysosomal-triggered apoptosis is identification of the cellular substrate(s) of cathepsins that could facilitate caspases activation. Our work implicates a role for cath-D independent of its catalytic function both in chemotherapeutic-induced cytotoxicity and in etoposide-induced apoptosis, and we suggest that an adequate strategy to identify cytosolic cath-D interacting protein(s) might be the two-yeast hybrid approach.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Karin Öllinger (Linköping University, Sweden) for her kind help and valuable discussions concerning the digitonin method, Jean-Yves Cance for the photographs, Nicole Lautredou-Audouy (Centre de Ressources en Imagerie Cellulaire) for confocal microscopy and Nadia Kerdjadj for her secretarial assistance. This work was supported by Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, University of Montpellier I, Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (grant 3344, E Liaudet-Coopman and grant 3118, S Baghdiguian), Ligue Nationale centre le Cancer who provided a fellowship for Mélanie Beaujouin, and Ministere de la Culture, de I’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche du Luxembourg who provided a fellowship for Dr Murielle Glondu-Lassis.

References

- Berchem G, Glondu M, Gleizes M, Brouillet JP, Vignon F, Garcia M, Liaudet-Coopman E. Oncogene. 2002;21:5951–5955. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidère N, Lorenzo HK, Carmona S, Laforge M, Harper F, Dumont C, Senik A. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31401–31411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301911200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capony F, Morisset M, Barrett AJ, Capony JP, Broquet P, Vignon F, Chambon M, Louisot P, Rochefort H. J Cell Biol. 1987;104:253–262. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.2.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirman T, Oresic K, Mazovec GD, Turk V, Reed JC, Myers RM, Salvesen GS, Turk B. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:3578–3587. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308347200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deiss LP, Galinka H, Berissi H, Cohen O, Kimchi A. EMBO J. 1996;15:3861–3870. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demoz M, Castino R, Cesaro P, Baccino FM, Bonelli G, Isidore C. Biol Chem. 2002;383:1237–1248. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emert-Sedlak L, Shangary S, Rabinovitz A, Miranda MB, Delach SM, Johnson DE. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:733–742. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-04-0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrandina G, Scambia G, Bardelli F, Benedetti Panici P, Mancuso S, Messori A. British J Cancer. 1997;76:661–666. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foekens JA, Look MP, Bolt-de Vries J, Meijer-van Gelder ME, van Putten WL, Klijn JG. British J Cancer. 1999;79:300–307. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6990048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia M, Derocq D, Pujol P, Rochefort H. Oncogene. 1990;5:1809–1814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glondu M, Coopman P, Laurent-Matha V, Garcia M, Rochefort H, Liaudet-Coopman E. Oncogene. 2001;20:6920–6929. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glondu M, Liaudet-Coopman E, Derocq D, Platet N, Rochefort H, Garcia M. Oncogene. 2002;21:5127–5134. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb RA, Nordberg J, Skowronski E, Babior BM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:654–658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich M, Neumeyer J, Jakob M, Hallas C, Tchikov V, Winoto-Morbach S, Wickel M, Schneider-Brachert W, Trauzold A, Hethke A, Schütze S. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:550–563. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson AC, Steen H, Öllinger K, Roberg K. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:1253–1259. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagedal K, Johansson U, Öllinger K. FASEBJ. 2001;15:1592–1594. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0708fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike M, Nakanishi H, Saftig P, Ezaki J, Isahara K, Ohsawa Y, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Watanabe T, Waguri S, Kametaka S, Shibata M, Yamamoto K, Kominami E, Peters C, von Figura K, Uchiyama Y. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6898–6906. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-06898.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike M, Shibata M, Ohsawa Y, Nakanishi H, Koga T, Kametaka S, Waguri S, Momoi T, Kominami E, Peters C, Figura K, Saftig P, Uchiyama Y. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;22:146–161. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(03)00035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent-Matha V, Maruani-Herrmann S, Prebois C, Beaujouin M, Glondu M, Noel A, Alvarez-Gonzalez ML, Blacher S, Coopman P, Baghdiguian S, Gilles C, Loncarek J, Freiss G, Vignon F, Liaudet-Coopman E. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:489–499. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200403078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaudet E, Garcia M, Rochefort H. Oncogene. 1994;9:1145–1154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama S, Llopis J, Deveraux QL, Tsien RY, Reed JC. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:318–325. doi: 10.1038/35014006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi H, Zhang J, Koike M, Nishioku T, Okamoto Y, Kominami E, von Figura K, Peters C, Yamamoto K, Saftig P, Uchiyama Y. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7526–7533. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-19-07526.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollinger K. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;373:346–351. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiners JJ, Jr, Caruso JA, Mathieu P, Chelladurai B, Yin XM, Kessel D. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:934–944. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberg K, Kagedal K, Öllinger K. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:89–96. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64160-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberg K, Öllinger K. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:1151–1156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberg K. Lab Invest. 2001;81:149–158. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochefort H. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:7–8. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00637-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saftig P, Hetman M, Schmahl W, Weber K, Heine L, Mossmann H, Koster A, Hess B, Evers M, Von Figura K, Peters C. EMBO J. 1995;14:3599–3608. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00029.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada M, Nakashima S, Banno Y, Yamakawa H, Hayashi K, Takenaka K, Nishimura Y, Sakai N, Nozawa Y. Cell Death Differ. 2000;7:761–772. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata M, Kanamori S, Isahara K, Ohsawa Y, Konishi A, Kametaka S, Watanabe T, Ebisu S, Ishido K, Kominami E, Uchiyama Y. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;251:199–203. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takuma K, Kiriu M, Mori K, Lee E, Enomoto R, Baba A, Matsuda T. Neurochem Int. 2003;42:153–159. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(02)00077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardy C, Tyynela J, Hasilik A, Levade T, Andrieu-Abadie N. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:1090–1100. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terman A, Neuzil J, Kagedal K, Öllinger K, Brunk UT. Exp Cell Res. 2002;274:9–15. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werneburg NW, Guicciardi ME, Bronk SF, Gores GJ. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;283:G947–956. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00151.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westley BR, May FE. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:15–24. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00530-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu GS, Saftig P, Peters C, EI-Deiry WS. Oncogene. 1998;16:2177–2183. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]