Abstract

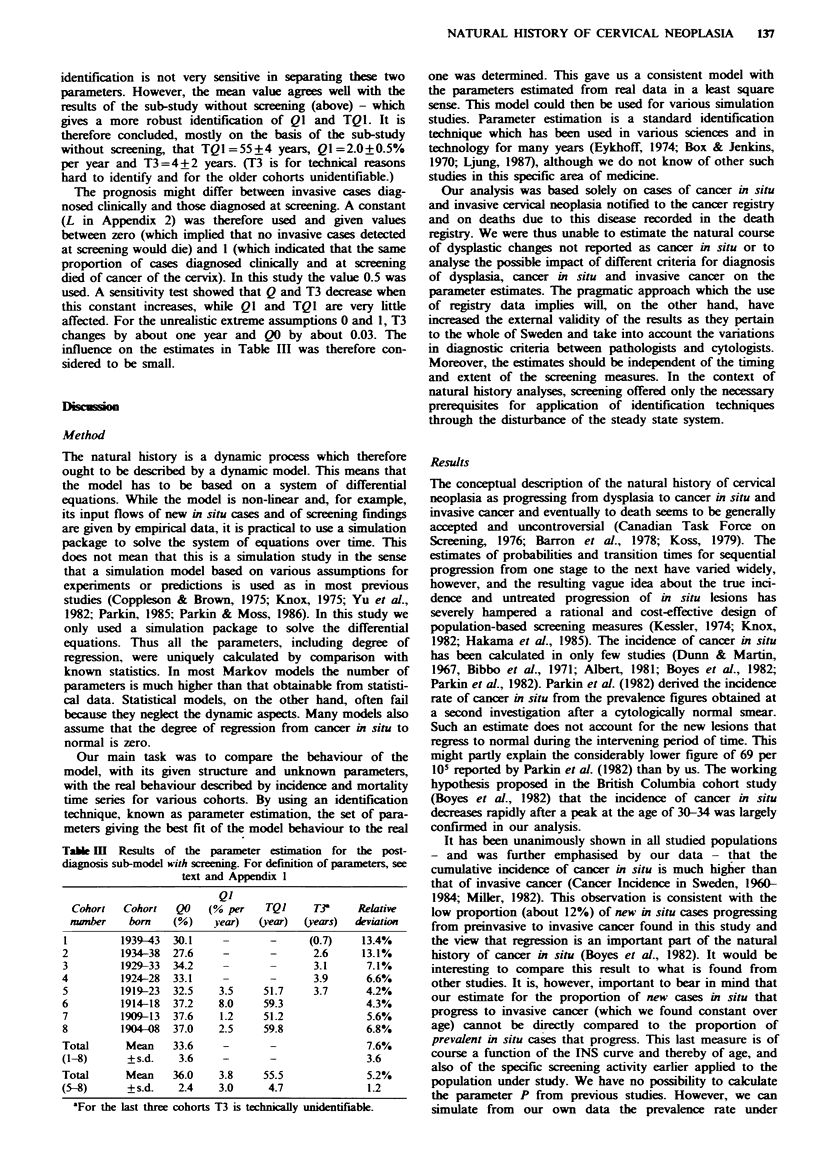

Swedish population-based incidence and mortality rates for cancer of the uterine cervix, both in situ and invasive, during the period 1958 to 1981 were determined by means of a dynamic model. This new approach describes without any preconceptions the development of the disease as a sequential process over the stages cancer in situ, invasive cancer before and after diagnosis, and death. The strong disturbance of the steady-state situation that occurred after the introduction of cytological mass screening in the early 1960s permitted the use of a computerized identification technique. The whole natural history of cervical cancer could thus be identified and described consistently, with the mutual compatibility between statistical data, structure, parameters, and the states and flows between the states. The estimated age-specific incidence of cancer in situ increased rapidly to a maximum of 650 per 10(5) woman-years at the age of 30 years, after which it declined, and that of invasive cancer to a maximum of 55 per 10(5) at the age of 43. The natural history of cervical neoplasia did not differ appreciably between eight successive 5-year birth cohorts. The proportion of cases of new cancer in situ that progressed to invasive cancer was 12.2%, with a mean duration of the in situ stage in these cases of 13.3 years. The preclinical phase of the invasive stage (without screening) lasted on average about 4 years.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ashley D. J. Evidence for the existence of two forms of cervical carcinoma. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw. 1966 Jun;73(3):382–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1966.tb05178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAILAR J. C., 3rd Uterine cancer in Connecticut: late deaths among 5-year survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1961 Aug;27:239–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOYES D. A., FIDLER H. K., LOCK D. R. Significance of in situ carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Br Med J. 1962 Jan 27;1(5273):203–205. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5273.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barron B. A., Cahill M. C., Richart R. M. A statistical model of the natural history of cervical neoplastic disease: the duration of carcinoma in situ. Gynecol Oncol. 1978 Apr;6(2):196–205. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(78)90022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne R. G., Grove W. D. Invasive carcinoma of the cervix in Queensland. Change in incidence and mortality, 1959-1980. Med J Aust. 1983 Feb 19;1(4):156–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain J. Failures of the cervical cytology screening programme. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984 Oct 6;289(6449):853–854. doi: 10.1136/bmj.289.6449.853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook G. A., Draper G. J. Trends in cervical cancer and carcinoma in situ in Great Britain. Br J Cancer. 1984 Sep;50(3):367–375. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1984.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppleson L. W., Brown B. Estimation of the screening error rate from the observed detection rates in repeated cercival cytology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1974 Aug 1;119(7):953–958. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(74)90013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppleson L. W., Brown B. Observations on a model of the biology of carcinoma of the cervix: a poor fit between observation and theory. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1975 May 1;122(1):127–136. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(75)90627-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUNN J. E., Jr The relationship between carcinoma in situ and invasive cervical carcinoma; a consideration of the contributions to the problem to be made from general population data. Cancer. 1953 Sep;6(5):873–886. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195309)6:5<873::aid-cncr2820060506>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper G. J., Cook G. A. Changing patterns of cervical cancer rates. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1983 Aug 20;287(6391):510–512. doi: 10.1136/bmj.287.6391.510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duguid H. L., Duncan I. D., Currie J. Screening for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in Dundee and Angus 1962-81 and its relation with invasive cervical cancer. Lancet. 1985 Nov 9;2(8463):1053–1056. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)90917-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J. E., Jr, Martin P. L. Morphogenesis of cervical cancer. Findings from San Diego County Cytology Registry. Cancer. 1967 Nov;20(11):1899–1906. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196711)20:11<1899::aid-cncr2820201116>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidler H. K., Boyes D. A., Worth A. J. Cervical cancer detection in British Columbia. A progress report. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw. 1968 Apr;75(4):392–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1968.tb00136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakama M., Chamberlain J., Day N. E., Miller A. B., Prorok P. C. Evaluation of screening programmes for gynaecological cancer. Br J Cancer. 1985 Oct;52(4):669–673. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1985.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakama M., Penttinen J. Epidemiological evidence for two components of cervical cancer. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1981 Mar;88(3):209–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1981.tb00970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper T. A., Smith E. S., Cooper P., Clayton J., Todd D. An analysis of the prevalence and incidence of gynecologic cancer cytologically detected in a population of 175,767 women. Acta Cytol. 1970 May;14(5):261–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler I. I. Perspectives on the epidemiology of cervical cancer with special reference to the herpesvirus hypothesis. Cancer Res. 1974 May;34(5):1091–1110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lără E., Day N. E., Hakama M. Trends in mortality from cervical cancer in the Nordic countries: association with organised screening programmes. Lancet. 1987 May 30;1(8544):1247–1249. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)92695-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattsson B., Wallgren A. Completeness of the Swedish Cancer Register. Non-notified cancer cases recorded on death certificates in 1978. Acta Radiol Oncol. 1984;23(5):305–313. doi: 10.3109/02841868409136026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PETERSEN O. Spontaneous course of cervical precancerous conditions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1956 Nov;72(5):1063–1071. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(56)90072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkin D. M. A computer simulation model for the practical planning of cervical cancer screening programmes. Br J Cancer. 1985 Apr;51(4):551–568. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1985.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkin D. M., Hodgson P., Clayden A. D. Incidence and prevalence of preclinical carcinoma of cervix in a British population. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1982 Jul;89(7):564–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1982.tb03661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkin D. M., Moss S. M. An evaluation of screening policies for cervical cancer in England and Wales using a computer simulation model. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1986 Jun;40(2):143–153. doi: 10.1136/jech.40.2.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersson F., Björkholm E., Näslund I. Evaluation of screening for cervical cancer in Sweden: trends in incidence and mortality 1958-1980. Int J Epidemiol. 1985 Dec;14(4):521–527. doi: 10.1093/ije/14.4.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorn J. B., Russell E. M., Macgregor J. E., Swanson K. Costs of detecting and treating cancer of the uterine cervix in North-East Scotland in 1971. Lancet. 1975 Mar 22;1(7908):674–676. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)91771-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]