The First International Meeting on Quadruplex DNA took place between 21 and 24 April 2007, in Louisville, Kentucky, USA. The meeting followed two regional workshops (pan-Pacific and European) in Hawai (2005) and Slovenia (2006), and was organized by J. Chaires and L. Hurley.

Introduction

The conference literally started with a bang! The meeting brought together around 110 scientists from all over the world to present their most recent data on quadruplex DNA, and the opening reception coincided with Thunder Over Louisville, a massive fireworks display marking the start of the Kentucky Derby Festival. The focus of the conference was the family of nucleic acid secondary structures known as guanine (G)-quadruplexes. These can be formed by certain guanine-rich sequences in the presence of monovalent cations and are stabilized by G-quartets (Fig 1). Interest in this area has intensified in recent years because G-quadruplex structures have roles in crucial biological processes and can be targeted for therapeutic intervention (Maizels, 2006; Neidle & Balasubramanian, 2006; Riou, 2004). G-quadruplexes might also have applications in areas ranging from supramolecular chemistry and nanotechnology to medicinal chemistry (Alberti et al, 2006; Davis, 2004; Petraccone et al, 2005). The aim of this meeting was to assess the current status of this unusual DNA structure, which was discovered more than 40 years ago by our plenary lecturer, D. Davies (Bethesda, MD, USA), and his colleagues (Gellert et al, 1962). The meeting also coincided with the tenth anniversary of a seminal paper that catalysed much interest in the field and laid the foundations for therapeutic possibilities (Sun et al, 1997). Here, we summarize a few of the highlights from the broad range of topics discussed.

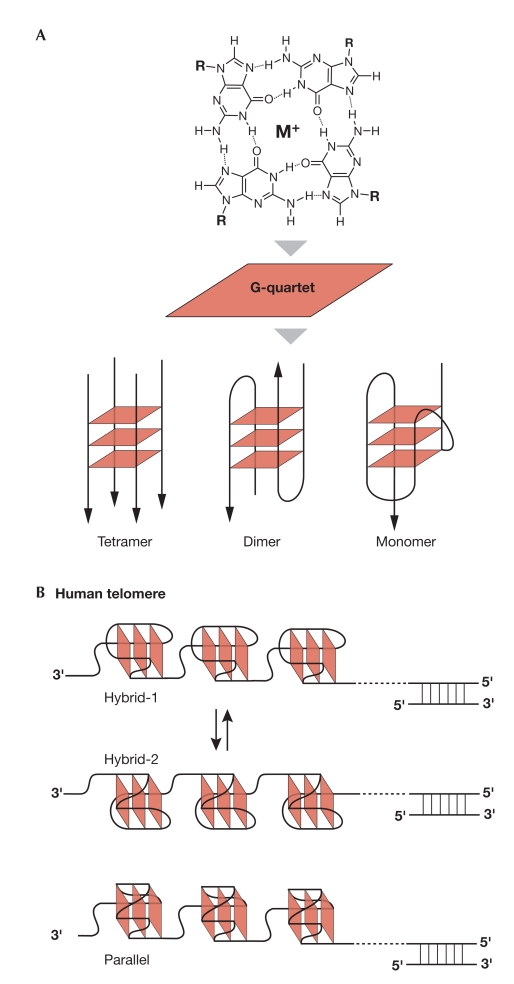

Figure 1.

The quadruplex. (A) A tetrameric, dimeric and monomeric G-quadruplex composed of three G-quartets (top). (B) A schematic model of DNA secondary structure composed of compact-stacking multimers of the hybrid-type quadruplex structures (top and middle) in human telomeres. The model of the compact-stacking multimers of the parallel-stranded structures is also shown (bottom).

Structural diversity of quadruplexes

Quadruplexes can be formed with one, two or four G-rich strands (Fig 1). Tetramolecular quadruplexes generally adopt a well-defined structure, in which all guanines are in the anti-glycosidic conformation and all strands are parallel, and might be useful for biotechnology applications. J.-L. Mergny (Paris, France) described the stability and kinetics of tetramolecular quadruplexes. He reported that tetramolecular quadruplexes with stacked G-quartets are extremely stable and that quadruplex ligands can act as molecular chaperones to increase the normally slow rate of tetramolecular quadruplex association, so that they form in minutes rather than days (De Cian & Mergny, 2007).

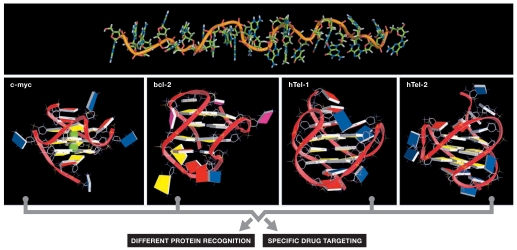

Intramolecular G-quadruplexes formed by a single DNA strand have attracted much interest because they might form in telomeres, oncogene promoter sequences and other biologically relevant regions of the genome. In contrast to tetramolecular quadruplexes, intramolecular structures form quickly and are more complex, showing great conformational diversity, such as folding topologies, loop conformations and capping structures (Fig 2). Different sequences adopt distinct topologies, but a given sequence can also fold into various different conformations, which can coexist. One of the best illustrations of this complexity are human telomere sequences, in which variants of the minimal four G-tract core sequence of the human telomere, 5′-(GGGTTA)3GGG, have been synthesized and studied by high-resolution nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) or crystallography. Although the structure in Na+ solution was reported more than a decade ago (Wang & Patel, 1993), the ‘potassium structure' has been the subject of intense investigation, largely because the high intracellular concentration of K+ ions suggests that it should be the more biologically relevant form. The crystal structure of the human telomeric G-quadruplex in the presence of K+ was reported five years ago (Parkinson et al, 2002) and is a parallel-stranded monomer, which is different from the Na+ solution structure that contains antiparallel strands. Recently, several groups—including those of H. Sugiyama (Kyoto, Japan), D. Yang (Tucson, AZ, USA) and D. Patel (New York, NY, USA)—reported the folding patterns and molecular structures of intramolecular telomeric G-quadruplexes in K+ solution (Ambrus et al, 2006; Luu et al, 2006; Xu et al, 2006). A. Phan (Nanyang, Singapore) reported an NMR structural study of two distinct intramolecular quadruplexes formed by natural human telomere sequences in K+ solution. He discovered a new folding topology, called Hybrid-2 (Phan et al, 2006), which differs from the previously reported Hybrid-1 folding.

Figure 2.

Quadruplex polymorphism. Examples of intramolecular G-quadruplexes with different folding and capping structures. Intramolecular G-quadruplex structures are all derived from a single-stranded DNA (top). The conformational diversity suggests that these G-quadruplex structures might be specifically recognized by various proteins and small molecule ligands. c-myc reprinted with permission from Ambrus et al (2005), copyright 2005 American Chemical Society; bcl-2 reprinted with permission from Dai et al (2006b); hTel-1 reprinted with permission from Dai et al (2007b); hTel-2 reprinted with permission from Dai et al (2007a).

At this meeting, Yang presented the determination of the Hybrid-2 three-dimensional structure using a 26-nucleotide wild-type telomeric sequence—5′-(TTAGGG)3TT—the first reported for the native biological sequence in K+ solution (Dai et al, 2007a). This structure has mixed parallel/antiparallel strand orientations. She reported that the two distinct conformations—Hybrid-1 and Hybrid-2—have a low energy barrier between them and appear to coexist in solution. Her results emphasized the importance of capping structures on selective quadruplex conformation. Yang also mentioned the possibility that hybrid-type structures could participate in forming higher order structures consisting of compact stacking G-quadruplexes (Fig 1), as first suggested for the parallel-stranded form (Parkinson et al, 2002).

Potential quadruplex-forming sequences are also widespread throughout the genome, especially in gene promoters (Fig 3). These structures are expected to be different from telomeric quadruplexes—not least because they will be in the context of double-stranded DNA—although by no means less complicated. In contrast to the uniform repeating G-rich sequence in telomeres, the G-rich sequences of gene promoters are often composed of more than four G-tracts with each G-tract containing unequal numbers of guanines and separated by various numbers of bases. Therefore, each sequence is able to form many possible quadruplex structures by using different combinations of G-tracts or guanines within a tract. An interesting feature of the promoter quadruplexes is the occurrence of stable structures with single-nucleotide double-chain-reversal loops (Dai et al, 2006a). Such single-nucleotide double-chain-reversal loops have previously been found in the c-myc promoter G-quadruplexes (Phan et al, 2004; Seenisamy et al, 2004). Phan reported a new quadruplex fold formed in a wild-type sequence of the c-kit promoter. This scaffold is extremely unusual in that an isolated guanine is involved in G-tetrad core formation, despite the presence of four guanine tracts (Phan et al, 2007). Notably, this structure also contains single-nucleotide-sized loops. S. Balasubramanian (Cambridge, UK) reported on a different region of the c-kit promoter that also forms a stable intramolecular quadruplex, which shows little dynamic interaction. Importantly, this second c-kit quadruplex could be detected within a naturally extended DNA duplex by using single-molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer (Shirude et al, 2007).

Figure 3.

Quadruplex in a gene promoter. Alternative forms of the NHE III1 of the c-myc promoter associated with transcriptional activation or silencing. CNBP, cellular nucleic acid binding protein; hnRNP, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein; NHE III, nuclease hypersensitive element III; TBP, TATA binding protein.

Several speakers described systematic investigations to characterize further the relationship between sequence and structure, in terms of quadruplex features such as glycosidic bond angles, strand orientations, loop positions and groove widths. M. Webba da Silva (Coleraine, UK) reported on his group's effort to establish rules to predict the folding patterns of intramolecular G-quadruplexes based on nucleotide sequences. He suggested that there could be other folding topologies in addition to those identified so far. Phan discussed the known G-quadruplex structures and performed a systematic analysis of their folding and structures. Other groups have approached this from a different angle, attempting to manipulate folding topology by various substitutions. R. Shafer (San Francisco, CA, USA) reported that the conformation could be controlled by selective substitution of riboguanosine (rG) for deoxyriboguanosine (dG), because rG strongly prefers the anti-glycosidic conformation. Conversely, 8-bromoguanine prefers syn-glycosidic conformation and can also affect the G-quadruplex folding topology, as described by Sugiyama. J. Sponer (Brno, Czech Republic) provided a critical assessment of using molecular dynamics simulations to study quadruplex DNA, pointing out both the potential usefulness and present limitations—which are mainly related to inadequate force fields—of this approach.

Quadruplexes in telomeres or quadruplexes everywhere?

For many years, the question facing biologists in the quadruplex field was whether quadruplex structures really exist in vivo. There is now overwhelming evidence that they do (Maizels, 2006) and the field has moved forward to focus on understanding the biological functions of various quadruplexes.

D. Rhodes (Cambridge, UK) and H. Lipps (Witten, Germany) provided an overview of their work studying telomere regulation in the ciliate Stylonychia, in which quadruplex formation in telomeres can be directly observed in vivo using specific antibodies. By staining with the antibody throughout the cell cycle, they showed that telomeric quadruplex structures are resolved during replication. Their recent research also indicates that this quadruplex unfolding is mediated by telomerase, which is recruited to telomeres by phosphorylated telomere end binding protein β (TEBP-β). It will be interesting to see what these elegant studies can teach us about the biology of mammalian telomeres. N. Maizels (Seattle, WA, USA) described non-telomeric sequences that have a high potential for quadruplex formation, with particular emphasis on immunoglobulin heavy-chain switch regions. She made the important point that, for quadruplex formation to occur within the context of double-stranded DNA, duplex unwinding must occur. Therefore, quadruplex formation is most likely to be seen during processes such as transcription, replication or recombination, when the DNA duplex is actively denatured. Maizels discussed several proteins that bind to quadruplex-containing structures, including nucleolin, MutS-α, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs) and RecQ family helicases, such as BLM (Bloom syndrome) helicase. Quadruplex-binding proteins were also a theme in the talk from M. Fry (Haifa, Israel). He examined an RNA, rather than a DNA, quadruplex target. He described the effects of (CGG)n repeat expansion on the translation of the Fragile X syndrome-associated Fragile X mental retardation 1 (FMR1) mRNA. In carriers of the Fragile X‘pre-mutation' (n = 56–200), the efficiency of FMR1 translation is reduced by 5–10-fold compared with unaffected individuals (n < 55), and it is hypothesized that this is due to quadruplex formation in the mRNA. Expression of proteins such as CArG box binding protein-A (CBF-A) or hnRNP A2, which destabilize the (CGG)n quadruplex in vitro, were found to increase the translational efficiency of reporter mRNAs containing pre-mutation size (CGG)n tracts. As the Fragile X pre-mutation is associated with ovarian failure in women and ataxia in men, quadruplex-disrupting agents could prove to be therapeutic for this condition.

The prevalence and relevance of G-quadruplexes in non-telomeric genomic DNA was one of the most debated subjects at the meeting. Recent whole-genome analyses by several groups have revealed that potential quadruplex-forming sequences are surprisingly common. For example, it is estimated that there might be more than 370,000 potential quadruplex-forming sequences in the human genome (Huppert & Balasubramanian, 2005; Todd et al, 2005). However, one should emphasize that these sequences remain putative, and that many sequences found in the human genome might well never adopt a quadruplex structure for several reasons. Certainly, with the possible exception of the c-myc promoter (Fig 3; Siddiqui-Jain et al, 2002), the biological functions of these putative quadruplexes are uncertain at present. However, much circumstantial evidence to support the biological relevance of these suspected quadruplexes was presented at the meeting. F. Johnson (Philadelphia, PA, USA) described his work in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, in which he found a 14-fold enrichment of potential quadruplex-forming sequences in gene promoters relative to the genome as a whole. Interestingly, many of the genes altered in S. cerevisiae treated with a specific quadruplex ligand had a high potential for forming G-quadruplexes in their promoters. Furthermore, a mutant lacking the quadruplex-specific helicase Sgs1 had a general decrease in the expression of genes in which open reading frames have a high potential to form quadruplexes. He also pointed out several genetic links suggesting quadruplex-based coordination between telomere shortening and transcriptional regulation, possibly mediated by repressor/activator protein 1 (RAP1). Maizels reported that, within the human genome, the potential for quadruplex formation was high within oncogenes but low for tumour suppressor genes. She suggested a link between quadruplex-forming potential and genomic instability. Tumour suppressors might have evolved a low level of quadruplex-forming potential to avoid instability. The high quadruplex-forming potential within proto-oncogenes might reflect some form of shared regulation at the level of transcription, RNA processing or translation, but makes these genes susceptible to translocations. Balasubramanian presented data analysing upstream elements within the human genome that revealed a strong correlation between nuclease-hypersensitive elements, which are indicative of unusual DNA structures, and quadruplex-forming potential.

A direct comparison of these genome-wide analyses was difficult, as each group used a different algorithm to map potential quadruplex-forming sequences—some using a rather restrictive definition, whereas others used a much larger window. The relative advantages and disadvantages of each algorithm are so far unknown, but the conclusions reached are likely to depend on which one is chosen. By the end of the meeting, there seemed to be a consensus that these widespread potential quadruplex-forming sequences probably do have an important role in transcriptional regulation. Their most likely functions seem to be related to coordinating gene expression in response to certain stimuli, but the identity of the stimuli and the molecules that regulate the process have not yet been reported.

Quadruplex ligands

The intramolecular telomeric G-quadruplex has been considered to be an attractive target for anticancer drug design ever since quadruplex ligands were found to inhibit telomerase, an enzyme that is activated in most cancer cells but not in most non-cancerous cells (Sun et al, 1997). In addition to the slow erosion of telomeres caused by blocking telomerase, it has recently become apparent that quadruplex ligands can induce rapid apoptosis owing to displacement of telomere-binding proteins. Many quadruplex-specific ligands have been identified and the crystal structures that are available, together with NMR data, provide a consistent view of how many ligands bind. Terminal stacking at the end of the quadruplex is the most frequently encountered method, whereas groove binding is indicated for a few molecules. E. Lewis (Flagstaff, AZ, USA) found two methods of interaction for a cationic porphyrin, one of them suggestive of an intercalation between two G-quartets. D. Wilson (Atlanta, GA, USA) indicated that some quadruplex ligands might also recognize the grooves of a quadruplex, and used surface plasmon resonance to study the affinity and specificity of such molecules. For some ligands—for example, TMPyP4 (5,10,15,20-tetra(N-methyl-4-pyridyl)porphine chloride)—the preference for quadruplexes over duplexes was found to be quite low. All attendees agreed that structural information on ligand binding is an area that requires further investigation.

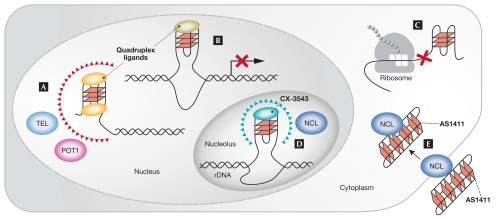

The presentations at the meeting provided many reasons to be optimistic about the therapeutic potential of telomere-targeting agents—several agents have now shown anticancer activity in animals and clear evidence of a telomere-based mechanism. S. Neidle (London, UK) provided an update on BRACO19 (3,6,9-trisubstituted acridine 9-[4-(N,N-dimethylamino)phenylamino]-3,6-bis(3-pyrrolodinopropionamido) acridine), a tri-substituted acridine that shows cancer-selective toxicity in cultured cells and reduces tumour growth in mice. Its biological effects depend on the dose and include a reduction in telomere length, induction of senescence and the production of end-to-end chromosomal fusions—all of which are consistent with a telomere-based mechanism. In vivo, BRACO19 also produces molecular changes that are consistent with its proposed mechanism of telomere uncapping—for example, human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) relocalization and DNA damage response. However, extensive pre-clinical studies concluded that the therapeutic window for BRACO19 is small and improved analogues are now being developed. J.-F. Riou (Reims, France) described mechanistic studies on telomestatin, a potent and selective quadruplex-binding agent first reported by Shin-ya et al (2001). Telomestatin could displace protection of telomeres 1 (POT1) from telomeres, whereas overexpression of POT1 protected cells against telomestatin. Interestingly, telomestatin also displaced telomeric repeat binding factor 2 (TRF2) in cancer cells but not in a non-malignant line. Riou also described DNA damage responses induced by telomestatin and a triazine derivative. In cells treated with low doses of telomestatin, γ-H2AX only partly co-localized with POT1, suggesting that some damage response is occurring at other sites, as well as at the telomeres. He reported ATR-like (ATR for ataxia telangiectasia related) responses at low doses of triazine, whereas protein phosphatase 1D magnesium-dependent, delta isoform (PPM1D) responses were predominant at higher doses. Riou suggested that these quadruplex ligands work by blocking the activity of a quadruplex resolvase and mentioned topoisomerase III as a possible candidate. Sugiyama and his group took a novel approach to developing new agents and targeted the cavity between two individual quadruplexes within the proposed higher order telomere structure (Fig 1). They synthesized a series of cyclic helicenes with various ‘wedge' angles and tested for specific binding to the natural telomere ‘dimer'. Some of the helicenes displayed enantioselective binding, were active in a modified telomere repeat amplification protocol (TRAP) assay and had modest selectivity for quadruplex compared with duplex DNA.

Although time constraints allowed only a handful of talks on quadruplex ligands, this is clearly a very active area of research as there were at least 14 posters describing new ligands. These new molecules covered a range of chemical entities, including analogues of existing agents, new small molecules, natural products and peptide nucleic acids.

Quadruplexes in the clinical arena

One of the most exciting aspects of this meeting was the presentation of data from two quadruplex-related agents that have already made it into the clinic. J. Whitten (San Diego, CA, USA) described the development and mechanism of CX-3543 (quarfloxin; Cylene Pharmaceuticals, San Diego, CA, USA), a small molecule that is now in phase II clinical trials. CX-3543 was originally designed to target the c-MYC promoter quadruplex, and was observed to have potent and tumour-selective activity in a wide range of cultured cancer cells and in vivo models. However, CX-3543 showed no direct inhibitory effect on c-MYC expression, suggesting that an alternative mechanism was operative. CX-3543, which autofluoresces, localizes to cancer cell nucleoli that contain many copies of the genes encoding rRNAs. These genes—known as rDNA—contain a very high density of potential quadruplex-forming sequences, some of which have been shown to bind to nucleolin protein (Maizels, 2006). CX-3543 disrupts the formation of the complex formed between rDNA quadruplexes and nucleolin, and leads to a protein–DNA complex that is amplified in cancer cells. Consequently, CX-3543 induces nucleolin redistribution, the inhibition of ribosome biogenesis and the induction of apoptosis in cancer cells. Interestingly, CX-3543 was not found to accumulate in the nucleoli of non-cancerous cells, which presumably contributes to its cancer-specific activity. It is not yet clear whether the mechanism of CX-3543 reflects its preference for rDNA quadruplexes over other quadruplex forms or just the high density of quadruplexes present in rDNA.

Another molecule—a 26-nucleotide quadruplex-forming oligonucleotide named AS1411 (Antisoma, London, UK)—has completed phase I clinical trials. P. Bates (Louisville, KY, USA) described how she discovered AS1411 in collaboration with D. Miller and J. Trent (Louisville, KY, USA) after noticing that certain G-rich DNA sequences could specifically inhibit cancer cell proliferation. Mechanistic studies indicate that quadruplex formation is essential for the activity and nuclease-resistance of AS1411. Furthermore, the activity of AS1411 is strictly dependent on its binding to nucleolin protein but, in contrast to CX-3543, AS1411 does not inhibit ribosomal biogenesis. Instead, AS1411 seems to bind to cell-surface nucleolin inducing internalization of the oligonucleotide into the cell where it affects several other nucleolin functions (Fig 4). Bates suggested that the cancer-selectivity of AS1411 is due to preferential uptake in cancer cells, which is related to high levels of nucleolin on their surface. Miller presented data from the phase I clinical trial of AS1411. He reported that 30 patients with various types of advanced cancer received continuous infusions of AS1411 at doses up to 40 mg kg−1day−1 for 7 days and no serious side effects were observed. Miller also highlighted encouraging signs of clinical activity in patients receiving AS1411, particularly those with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. He reported that of the 12 renal cell carcinoma patients in the trial, one had a complete response, one had a marked partial response, seven had disease stabilization and three had disease progression. Several of the patients had responses or stabilization lasting 12 months or more. Miller noted that the timing of the observed responses was unusual, with some patients having initial disease stabilization followed by a gradual tumour reduction over many months after just one treatment with AS1411. Phase II clinical trials of AS1411 have recently begun.

Figure 4.

Quadruplexes in biology and as therapeutic agents or targets. Cartoon illustrating some possible roles of quadruplex formation in vivo and therapeutic strategies based on quadruplex formation. Antiparallel quadruplexes are shown for simplicity, but actual structures might vary. (A) Quadruplex formation in the single-stranded regions of telomeres. Ligands that stabilize the quadruplex might lead to cellular senescence by preventing telomere extension mediated by telomerase (TEL), and might also induce rapid apoptosis by displacing telomere-binding proteins, for example, protection of telomeres 1 (POT1). (B) Quadruplex formation in the context of duplex DNA is now suspected for many gene promoter regions, especially oncogene promoters. The quadruplex structure is a transcriptional repressor for some oncogenes, for example, c-MYC, and quadruplex-stabilizing ligands might act to block transcription. (C) Quadruplexes can also form in RNA and might hinder translation. (D) Ribosomal genes (rDNA), which are located in the nucleolus of the cell, contain a high concentration of potential quadruplex-forming sequences. These rDNA quadruplexes seem to be the target of CX-3543, a quadruplex-binding small molecule that is now in clinical trials as an anticancer agent. CX-3543 localizes to nucleoli and prevents nucleolin protein (NCL) from binding to rDNA quadruplexes, leading to inhibition of ribosome biogenesis. (E) AS1411 is a quadruplex-forming oligonucleotide that is now being tested in human clinical trials. This molecule also targets nucleolin protein and seems to bind to the cell surface form of the protein, which is present at high levels in cancer cells, leading to internalization of the complex. AS1411 can affect the molecular interactions and transport of nucleolin, thereby inhibiting many cancer cell survival pathways.

Applications of quadruplexes: bio- and nano-technologies

Not all applications of quadruplexes are directed towards therapeutics. J. Davis (College Park, MD, USA) analysed the self-assembly of lipophilic G-quadruplexes, with the ultimate aim of building an artificial ion channel. N. Sugimoto (Kobe, Japan) described why DNA is an attractive entity for designing nanostructures and nanodevices, and could even be useful for computing. He showed how DNA logic gates could be built by using quadruplexes and how long G-wires constructed with G-rich oligonucleotides containing a bipyridine loop can switch conformations in the presence of Ni2+ ions. Mergny talked about intramolecular quadruplexes with very long loops—up to 21 nucleotides—which might have an application as molecular beacon biosensors to detect specific DNA or RNA sequences.

The non-therapeutic applications of quadruplexes were perhaps covered too briefly with only a few talks, but several posters on relevant topics were also presented. Topics included ion exchange within a quadruplex, the use of quadruplexes for detection of metal cations by NMR, self-assembly of guanosine derivatives into large columns, quadruplex-containing aptamers and DNAzymes, and an energy-converting machine containing i-motif DNA.

Perspectives, unresolved issues and future directions

Of course, and fortunately for researchers, there remain many unanswered questions about quadruplexes. For example, most participants would agree that a quadruplex is a very stiff structure, but its persistence length is at present unknown and its electrical conductivity has yet to be shown. Another under-explored issue concerns the kinetics of quadruplex folding. Although we understand the kinetics of some simple quadruplexes, little is known about rates of duplex–quadruplex transitions and quadruplex interconversion events. Considerable effort should now be made to understand the kinetics of these systems, which would help to define the intermediate states, especially the rate-limiting state.

It should also be noted that—belying the title of the meeting—several groups have shown that quadruplex formation is not limited to the DNA backbone. G-quadruplexes have also been suggested to form in RNAs, most recently in (CGG)n trinucleotide repeats (see above) or in the 5′-UTR of the NRAS proto-oncogene (Kumari et al, 2007). The formation of quadruplexes in various RNAs will probably become the subject of several future studies as other polymers are also compatible with quadruplex formation, especially peptide nucleic acid (PNA). Another interesting issue is the structure of complementary C-rich oligonucleotides, which might adopt a completely distinct quadruplex structure called the i-motif under acidic conditions. Although the biological relevance of this motif is still controversial because its stability is generally limited at pH 7, data presented at the meeting suggest that the C-rich sequence in the myc promoter can form an i-motif structure at near physiological pH.

With respect to quadruplex ligands, an unresolved controversy is whether a ‘true' intercalation mode exists. Although no high-resolution structure has shown this possibility, some biophysical results support it. Other groups argue that intercalation suggests unstacking of two adjacent quartets, which would be energetically unfavourable and therefore unlikely. A more general observation is the increasing demand for commercially available quadruplex ligands, which could be used as reference molecules for biophysical, biochemical and biological studies. It was noted that the available molecules, such as TMPyP4, NMM (N-methylmesoporphyrin IX) or diaminoanthraquinones, have only limited specificity or affinity. Questions about the mechanism and clinical potential of quadruplex ligands also remain, especially in the light of the frequency of potential quadruplexes in the human genome. For example: what are the primary mechanisms of existing quadruplex-binding agents? Do these agents have a high enough selectivity for quadruplex DNA compared with duplex DNA? Is it possible, or necessary, to develop agents that can distinguish between quadruplex types—for example, telomere versus promoter, or parallel versus antiparallel? Another important point that came up at the meeting was the limitation of the TRAP assay, which is routinely used for measuring telomerase inhibition by quadruplex ligands. Mergny reported that ligands can interfere with the PCR of a G-quadruplex sequence while leaving the internal control sequence unaffected. Consequently, the inhibitory effect of many quadruplex ligands might be overestimated. The use of a direct assay to measure telomerase inhibition or removal of the ligand after the elongation step of the TRAP assay is therefore recommended.

For biological studies, it seems there is a need for better analytical tools. Perhaps the most useful would be antibodies against various human quadruplexes. Antibodies allowed the first visualization of quadruplex formation in vivo, in the macronuclei of a ciliate, but those antibodies do not crossreact with mammalian sequences. Alternative probes that might be helpful for cell-based and in vivo studies, such as quadruplex ligands linked to a nuclease or covalently binding platinum derivatives, were also suggested.

Finally, this meeting allowed us to identify several ways to improve the accessibility and visibility of quadruplex research. Many of the speakers with interests in structure emphasized the need for a standardized nomenclature, especially relating to folding topologies and loop conformations, as many different terms are now used to indicate the same thing. Although everyone seemed to agree to use quartet/quadruplex rather than tetrad/tetraplex, no consensus was reached on loop descriptions; for example, whether it should be ‘propeller' or ‘chain reversal', ‘edgewise' or ‘lateral'. The description of genome-wide searches for potential quadruplexes is another area that might benefit from standardization, both in terms of defining what constitutes a quadruplex-forming sequence and the adoption of standard abbreviations, such as PQS (potential quadruplex sequence) and G4P (quadruplex potential). The creation of a website dedicated to the quadruplex community was unanimously agreed to be desirable. In addition to the genomic servers that are already available to search for quadruplex-forming sequences, a site providing an introduction to this area and the various researchers in the field would be welcome. A database of quadruplex structures and folds would also be invaluable, and J. Huppert (Cambridge, UK) is happily enrolled in that task.

Final thoughts

Many participants agreed that this was one of the best meetings they had ever attended. The size and organization of the event allowed many discussions between scientists from different disciplines. Thanks to the generous support of sponsors, especially the James Graham Brown Cancer Center, registration fees were very reasonable and many junior researchers were able to attend. The posters—more than 80 of them—were discussed during lunch and during two dedicated sessions; so many were interesting that it was impossible to discuss all of them here. By the close of the meeting, a consensus was reached to repeat such a symposium every two years; therefore, the ‘Second International Quadruplex Meeting' will be held in 2009, probably in Europe.

Jean-Louis Mergny, Paula Bates & Danzhou Yang

Acknowledgments

We thank all participants for their outstanding presentations, and J. Chaires and L. Hurley for their excellent organization. We apologize to those whose work could not be included owing to space limitations.

Footnotes

Paula Bates is a consultant and shareholder for Antisoma PLC (London, UK).

References

- Alberti P, Bourdoncle A, Saccà B, Lacroix L, Mergny JL (2006) DNA nanomachines and nanostructures involving quadruplexes. Org Biomol Chem 4: 3383–3391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrus A, Chen D, Dai J, Jones RA, Yang D (2005) Solution structure of the biologically relevant G-quadruplex element in the human c-MYC promoter. implications for G-quadruplex stabilization. Biochem 44: 2048–2048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrus A, Chen D, Dai J, Bialis T, Jones RA, Yang D (2006) Human telomeric sequence forms a hybrid-type intramolecular G-quadruplex structure with mixed parallel/antiparallel strands in potassium solution. Nucleic Acids Res 34: 2723–2735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai JX, Dexheimer TS, Chen D, Carver M, Ambrus A, Jones RA, Yang DZ (2006a) An intramolecular G-quadruplex structure with mixed parallel/antiparallel G-strands formed in the human BCL-2 promoter region in solution. J Am Chem Soc 128: 1096–1098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai J, Chen D, Jones RA, Hurley LH, Yang D (2006b) NMR solution structure of the major G-quadruplex structure formed in the human BCL2 promoter region. Nuc Acid Res 34: 5133–5144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai J, Carver M, Punchihewa C, Jones RA, Yang D (2007a) Structure of the Hybrid-2 type intramolecular human telomeric G-quadruplex in K+ solution: insights into structure polymorphism of the human telomeric sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 35: 4927–4940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai J, Punchihewa C, Ambrus A, Chen D, Jones RA, Yang D (2007b) Structure of the intramolecular human telomeric G-quadruplex in potassium solution: A novel adenine triple formation. Nuc Acid Res 35: 2440–2450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JT (2004) G-quartets 40 years later: from 5′-GMP to molecular biology and supramolecular chemistry. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 43: 668–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Cian A, Mergny JL (2007) Quadruplex ligands may act as molecular chaperones for tetramolecular quadruplex formation. Nucleic Acids Res 35: 2483–2493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellert M, Lipsett MN, Davies DR (1962) Helix formation by guanylic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 48: 2013–2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppert JL, Balasubramanian S (2005) Prevalence of quadruplexes in the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res 33: 2908–2916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari S, Bugaut A, Huppert JL, Balasubramanian S (2007) An RNA G-quadruplex in the 5′ UTR of the NRAS proto-oncogene modulates translation. Nat Chem Biol 3: 218–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luu KN, Phan AT, Kuryavyi V, Lacroix L, Patel DJ (2006) Structure of the human telomere in K+ solution: an intramolecular (3 + 1) G-quadruplex scaffold. J Am Chem Soc 128: 9963–9970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maizels N (2006) Dynamic roles for G4 DNA in the biology of eukaryotic cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol 13: 1055–1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neidle S, Balasubramanian S (2006) Quadruplex Nucleic Acids. Cambridge, UK: RSC Biomolecular Sciences [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson GN, Lee MPH, Neidle S (2002) Crystal structure of parallel quadruplexes from human telomeric DNA. Nature 417: 876–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petraccone L, Barone G, Giancola C (2005) Quadruplex-forming oligonucleotides as tools in anticancer therapy and aptamers design: energetic aspects. Curr Med Chem Anticancer Agents 5: 463–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan AT, Modi YS, Patel DJ (2004) Propeller-type parallel-stranded G-quadruplexes in the human c-myc promoter. J Am Chem Soc 126: 8710–8716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan AT, Luu KN, Patel DJ (2006) Different loop arrangements of intramolecular human telomeric (3+1) G-quadruplexes in K+ solution. Nucleic Acids Res 34: 5715–5719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan AT, Kuryavyi V, Burge S, Neidle S, Patel DJ (2007) Structure of an unprecedented G-quadruplex scaffold in the human c-kit promoter. J Am Chem Soc 129: 4386–4392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riou JF (2004) G-quadruplex interacting agents targeting the telomeric G-overhang are more than simple telomerase inhibitors. Curr Med Chem Anticancer Agents 4: 439–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seenisamy J, Rezler EM, Powell TJ, Tye D, Gokhale V, Joshi CS, Siddiqui-Jain A, Hurley LH (2004) The dynamic character of the G-quadruplex element in the c-MYC promoter and modification by TMPyP4. J Am Chem Soc 126: 8702–8709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin-ya K, Wierzba K, Matsuo K, Ohtani T, Yamada Y, Furihata K, Hayakawa Y, Seto H (2001) Telomestatin, a novel telomerase inhibitor from Streptomyces anulatus. J Am Chem Soc 123: 1262–1263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirude PS, Okumus B, Ying L, Ha T, Balasubramanian S (2007) Single-molecule conformational analysis of G-quadruplex formation in the promoter DNA duplex of the proto-oncogene c-kit. J Am Chem Soc 129: 7484–7485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui-Jain A, Grand CL, Bearss DJ, Hurley LH (2002) Direct evidence for a G-quadruplex in a promoter region and its targeting with a small molecule to repress c-MYC transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 11593–11598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D, Thompson B, Cathers BE, Salazar M, Kerwin SM, Trent JO, Jenkins TC, Neidle S, Hurley LH (1997) Inhibition of human telomerase by a G-quadruplex-interactive compound. J Med Chem 40: 2113–2116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd AK, Johnston M, Neidle S (2005) Highly prevalent putative quadruplex sequence motifs in human DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 33: 2901–2907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Patel DJ (1993) Solution structure of the human telomeric repeat d[AG3(T2AG3)3] G-tetraplex. Structure 1: 263–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Noguchi Y, Sugiyama H (2006) The new models of the human telomere d[AGGG(TTAGGG)3] in K+ solution. Bioorg Med Chem 14: 5584–5591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]