Abstract

Voltage sensing domains (VSD) play diverse roles in biology. As integral components, they can detect changes in the membrane potential of a cell and couple these changes to activity of ion channels and enzymes. As independent proteins, homologues of the VSD can function as voltage-dependent proton channels. To sense voltage changes, the positively charged fourth transmembrane segment, S4, must move across the energetically unfavourable hydrophobic core of the bilayer, that presents a barrier to movement of both charged species and protons. In order to reduce the barrier to S4 movement, it has been suggested that aqueous crevices may penetrate the protein, reducing the extent of total movement. To investigate this hypothesis in a system containing fully-functional channels in a native environment with an intact membrane potential, we have determined the contour of the membrane–aqueous border of the VSD of KvAP in E. coli by examining the chemical accessibility of introduced cysteines. The results revealed the contour of the membrane-aqueous border of the VSD in its activated conformation. The water-inaccessible regions of S1 and S2 correspond to the standard width of the membrane bilayer (∼28Å), but those of S3 and S4 are considerably shorter (≥40%), consistent with aqueous crevices pervading both the extracellular and intracellular ends. One face of S3b and the entire S3a were water-accessible, reducing the water-inaccessible region of S3 to just 10 residues, significantly shorter than for S4. The results suggest a key role for S3 in reducing the distance S4 needs to move to elicit gating.

Voltage sensing domains (VSD) are integral components of voltage-gated ion channels. In response to changes in transmembrane potential, they undergo conformational changes that lead to the opening or closing of the pore of voltage-gated ion (Na, K, Ca) channels (1-4). This ability to confer voltage dependent gating properties on ion channels enables them to play critical roles in a wide range of physiological processes, including the excitability of neuronal, cardiac and muscle cells, and secretion of hormones and neurotransmitters (5). A recent study showed that the role of VSD is not restricted to ion channels, but extends to other proteins. In Ciona intestinalis, an ascidian, the VSD has been found to be coupled to a phosphatase enzyme (CiVSP), where it regulates the activity of the enzyme in a voltage-dependent manner (6). Remarkably, it seems that VSDs are not merely integral regulatory components of channels and enzymes, but can function independently. For example, Hv1, a homologue of the VSD found in the human genome, is able to conduct protons by itself and this function has a physiological role in non-excitable tissues, such as testis, intestine and blood cells (7;8).

VSDs comprise four transmembrane domains, S1-S4. In voltage-gated ion channels, four VSDs are covalently linked to a central pore domain, made from the tetrameric assembly of S5-S6 helices (2-4). The S4 helix has 6-7 conserved positively charged residues (arginine/lysine), of which the first four appear to contribute to the voltage sensing function (3;4). The crystal structure of an isolated VSD from the bacterial voltage-gated potassium (Kv) channel, KvAP, has been solved (9). Although it bears a remarkable resemblance to the VSD in the more-recently solved rat Kv1.2 structure (10), its structure differs significantly from the VSD in the full-length KvAP (9;11). Interestingly, mutation of some S4 arginines to less bulky amino acids confers proton conducting function on the VSD (12-14). In voltage-gated Na channels such mutations lead to proton leak and underlie hypokalaemic periodic paralysis (15). Despite these breakthrough studies, the molecular basis of how the VSD senses changes in membrane potential, and can conduct protons, remains unclear.

It is, however, generally accepted that in response to changes in membrane potential, the top four S4 arginines (spanning a distance of ∼13.5 Å) move across the hydrophobic core of the bilayer (2-4;16). However, the mechanism by which this is accomplished remains highly controversial (3;4;17;18). Two main divergent models have emerged: a ‘paddle model’ and a ‘focussed-field model’. According to the paddle model, S4 and the C-terminal end of S3, S3b, forms a helix-turn-helix structure (termed paddle) which moves as a rigid body across the membrane by 15-20 Å during gating (16;19). Such large motions seem to be consistent with the large charge translocation reported in eukaryotic channels. However, the paddle model is based exclusively on avidin capture studies of KvAP, and contradicts the focussed-field model, which was developed from several lines of evidence on eukaryotic channels, all indicating a much smaller (<5 Å) S4 translation (3;12;20-22). To account for the large charge (∼13e) translocation with only a small S4 translation, it was proposed that the hydrophobic core of the bilayer is thin in the vicinity of S4, with large aqueous crevices penetrating the bilayer from both the extracellular and cytosolic phases (3;4;12;17). However, such aqueous crevices are not discernible in the crystal structures of KvAP (9;11). Given the significant homology between KvAP and eukaryotic channels (9), it is difficult to envisage how the structure of KvAP could differ from that of eukaryotic channels. Indeed, modelling studies suggest that KvAP is structurally similar to rat Kv1.2 (10).

Several studies have examined the topology of KvAP VSD in a bilayer. Molecular dynamics simulation studies suggest that the bilayer is compressed in the vicinity of S4 and that this compression is brought about by a network of interactions between S4 arginines, lipid phosphates and water molecules (23;24). In an EPR study, Perozo's group have examined the accessibility of spin labels attached to different sites of VSD to O2 and Ni-EDDA to determine the lipid- and water-exposed positions respectively; they reported both water and lipid accessible regions of VSD (25). MacKinnon's group introduced biotin at different positions of KvAP and examined their accessibility to avidin (16;19). In all these studies, synthetic lipids were used to reconstitute the channels into bilayers or vesicles, and therefore do not endorse the conformation of the channel in its native environment. This is because lipids in a native membrane are highly heterogeneous, and their effect on membrane deformation in the vicinity of S4, and hence the configuration of aqueous crevices, is likely to be quite different from that of synthetic lipids. Indeed studies by MacKinnon's group showed that the conformation (11) and voltage-dependence properties (26) of KvAP vary with the nature of the lipid into which they are reconstituted. Moreover, unlike most other protein domains, VSDs are highly flexible and their conformation is highly dependent on the membrane potential. Thus it is unclear how much of native conformation is preserved during the crystallisation and reconstitution experiments.

We therefore set out to determine the topology of KvAP in live E. coli, where the channel is in its native environment. For this, we have developed a highly sensitive site-directed cysteine accessibility method. The method relies on in vivo radiolabelling of cysteine mutants, reaction of water-exposed cysteines with a thiol-modification reagent and detection of modified proteins by a biochemical method. Our results show that the accessibility of S3 is greater than S4, with the entire S3a segment and one face of S3b being water accessible, leaving a stretch of only ∼10 residues inaccessible. The results support the presence of large aqueous crevices and suggest an important role for S3 in reducing the distance over which S4 needs to move to effect gating.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Molecular Biology

KvAP (GI: 14601099) was sub-cloned into the pET28a inducible bacterial expression vector (Novagen). The native cysteine at position 247 was substituted with a serine to generate the cysteine-less (C-less) KvAP. Cysteine mutations were introduced by the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis method (Stratagene).

Selective radiolabelling of KvAP

KvAP was selectively radiolabelled using a method described previously (27). Briefly, E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells harbouring pET28a-KvAP were grown in 5 ml of 2YT medium at 37 °C (150 rpm) to an OD600 of 0.4. Cells were pelleted, resuspended in 5 ml of M9 minimal medium supplemented with all amino acids except methionine and cysteine (27) and grown at 37 °C for 30 min. To 1 ml of cells, isopropyl-β-thiogalactoside (IPTG) was added to 1 mM and incubated at 37 °C for 15 min. During this incubation, IPTG would induce the expression of sufficient amount of T7 RNA polymerase from the chromosome of BL21 (DE3) cells; the T7 RNA polymerase initiates transcription of the KvAP cDNA from the T7 promoter of pET28a. Rifampicin (20 mg/ml in methanol) was then added to 200 μg/ml and incubation continued for a further 45 min. Since rifampicin is an inhibitor of the E. coli RNA polymerase, expression of all chromosomal genes would be suppressed. Transcription of KvAP from the rifampicin-insensitive T7 RNA polymerase, however, is unaffected. Cells were next treated with 10 μCi of [35S]-methionine (MP Biomedicals) at room temperature for 5 min to allow selective radiolabelling of KvAP.

Accessibility studies of KvAP cysteine mutants

Each cysteine mutant of KvAP was radiolabelled as above. Cells (1 ml) containing the radiolabelled mutant protein were pelleted, washed and resuspended in 200 μl PBSg (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10.0 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, 5 mM glucose, pH 7.4). For accessibility assay, cells were split into four equal aliquots: Aliquot (i) was treated 5 mM 4-acetamido-4′-maleimidylstilbene-2,2′- disulfonic acid (AMS; Molecular Probes, prepared in N,N-dimethylformamide) to modify extracellular cysteines. Aliquot (ii) was treated with 5 mM AMS plus 2 % CHCl3 with immediate vortexing for 1 min to allow modification of intracellular cysteines. Aliquots (iii) (negative control) and (iv) (positive control) were left untreated. All four aliquots were incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Cells were pelleted, washed twice in PBSg, and solubilised in 30 μl of lysis buffer (2 % w/v SDS, 6 M urea, 15 mM Tris, pH 7.4). Aliquots (i), (ii) and (iv) were incubated with 5 mM mPEG-maleimide (mal-PEG; MW 5000, NEKTAR Therapeutics and Laysan Bio, Inc.) at 60 °C for 30 min. All aliquots were treated with an equal volume of 2× SDS loading buffer (4 % w/v SDS, 20 % v/v glycerol, 6 M urea, 125 mM Tris, pH 8.6) at 100 °C for 10 min subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by autoradiography.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Assay of cysteine accessibility of KvAP in live E. coli

Mackinnon's group reported overexpression of cloned KvAP in E.coli (28). Under the conditions of the experiment (rich culture medium), the expressed protein was detrimental to the growth of E.coli. Inclusion of Ba2+, a blocker of open potassium channels, in the culture medium reduced the toxicity, suggesting that the presence of excessive amounts of active KvAP could be toxic to the cell. In the present study, we have expressed KvAP in a minimal defined medium for a short period. Under these conditions, there appear to be no appreciable toxicity, as judged by the fact that KvAP expression could be readily detected by pulse labeling (see below and Fig. 1); the apparent lack of toxicity may be attributed to low level expression of KvAP. This was fortuitous, because this has allowed us to examine the topology of the channel in live E.coli.

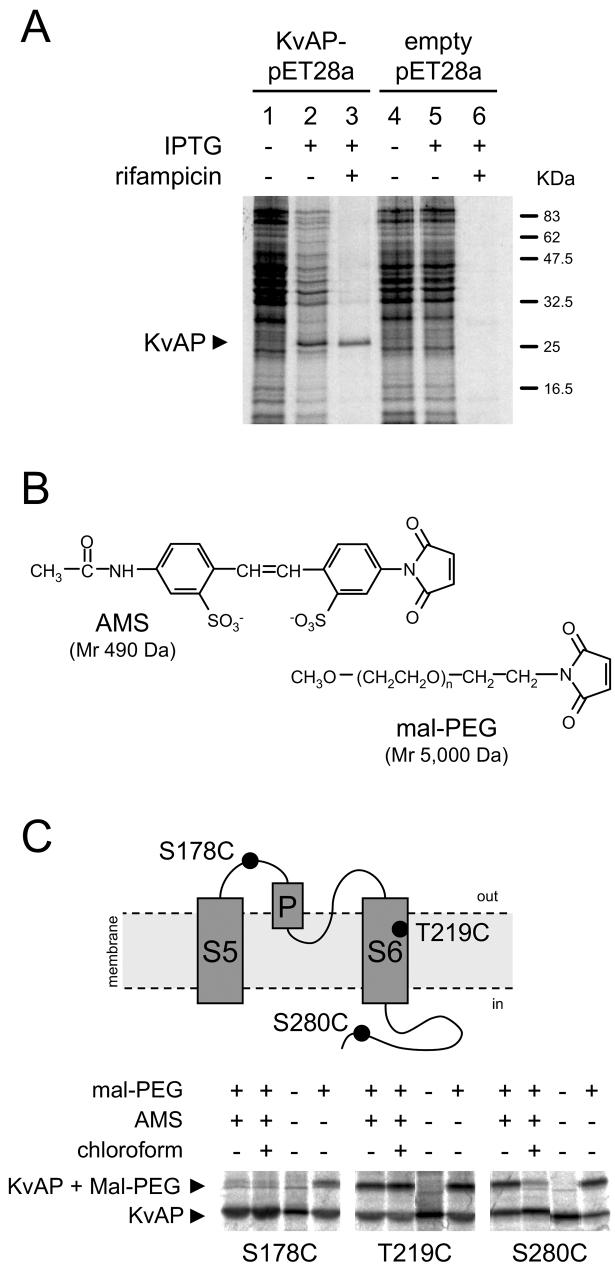

FIGURE 1. A biochemical assay to determine the extra- and intracellular residues of KvAP expressed in live E. coli.

A, selective radiolabelling of KvAP. Autoradiogram of [35S]radiolabelled proteins extracted from cells harbouring KvAP-pET28a (lanes 1-3) or the empty vector (lanes 4-6), before (lanes 1 and 4) and after (lanes 2 and 5) induction with IPTG; lanes 3 and 6 contain proteins from rifampicin-treated cells. Position of the KvAP band is shown with an arrowhead. B, structures of reagents used in the accessibility assay. C, gel-shift assay validated with representative cysteine positions, depicted in the schematic. Cells expressing the indicated radiolabelled KvAP mutants were pre-treated with 5 mM AMS plus or minus 2 % chloroform, followed by mal-PEG reaction, as indicated above each gel (for details see Experimental Procedures). Each set of gel images represents samples from the same experiment and gel, edited together for clarity. Positions of unmodified (∼25 KDa) and mal-PEG modified KvAP (∼33 kDa) are indicated with arrowheads.

To determine the membrane-aqueous boundaries of the VSD of KvAP, we have developed a simple and sensitive method that combined the in vivo selective radiolabelling of KvAP with site-directed cysteine modification. Fig. 1A shows how KvAP can be selectively radiolabelled in E. coli: in uninduced cells (lane 1) all cellular proteins were radiolabelled; IPTG-induced cells (lane 2) show an additional band corresponding to KvAP; in the IPTG plus rifampicin treated cells (lane 3), where native protein synthesis is suppressed, only the KvAP band was detectable. Corresponding KvAP bands were absent in cells harbouring the empty vector (lanes 5 and 6). Selective radiolabelling allowed easy detection of KvAP.

We expressed KvAP containing single cysteines as radiolabelled species and used the sulphydryl-specific maleimide reagent, 4-acetamido-4'-maleimidylstilbene-2,2'-disulfonic acid (AMS; see Fig. 1B) (29;30) to probe the position of introduced cysteines relative to the bilayer. AMS is a highly charged membrane impermeable sulphydryl reagent that reacts with the ionized thiolate (S−) group via its maleimide group. It can readily pass through the pores of the outer membrane of the cell and enter the periplasmic (extracellular) phase, but cannot permeate the inner membrane. As such, when applied to intact E.coli, AMS would react with cysteines exposed to the periplasm only. In the presence of 2% chloroform, however, AMS could cross the plasma membrane and also react with cysteines exposed to the cytoplasm. Although whilst crossing, AMS could access cysteines present in the membrane phase, significant modification is not expected to occur because cysteines cannot ionise in the hydrophobic environment of the bilayer, and for maleimides to react, cysteines must be in an ionised state. Modification of KvAP with AMS would increase the size of the protein by ∼500 Da, but this size increase is too small to be detected by SDS-PAGE. For this reason, we have adopted the indirect gel-shift assay described by Deutsch and colleagues (31). In this method, following modification with AMS, cells are solubilised in SDS and then treated with a high molecular weight (∼ 5000 Da) maleimide reagent, mal-PEG (Fig. 1B), to modify cysteines that have failed to react with AMS. This will result in a discernable gel-shift on SDS-PAGE.

To validate the method, we have examined the accessibility of three positions in the pore domain of KvAP (the structure of this region is uncontroversial), representing each of the environments: S178 (extracellular), T219 (membrane) and S280 (intracellular) (Fig. 1C). With all mutants, reaction with mal-PEG produced a higher molecular weight band (∼33 KDa) representing PEGylated KvAP (Fig. 1C; last lane in each panel). However, in AMS pre-treated cells, gel-shift was dependent upon the location of the cysteine: S178C failed to show any gel-shift indicating that C at 178 was accessible to AMS; S280C showed gel shift only in the absence of chloroform, consistent with the intracellular location of S280. T219C showed gel-shift under both conditions, consistent with the location of T219 in the membrane phase.

It may be pointed out that we did not observe complete PEGylation for any of the cysteine mutants even when the reaction was performed under strong denaturing conditions (SDS/urea buffer). The reason for this is unclear, but this should not affect the interpretation of the results because we always compared the protective effects of AMS against a positive control run in parallel under identical conditions. The method is simple, robust, highly sensitive, and unlike other methods (16;25), does not require over-expression and prior purification of the protein, and can be adopted to determine the topology of any membrane protein that can be expressed in E. coli, even at low levels.

For the assay to be reliable, however, it is important that the protein is inserted into the inner membrane of the cell. Unlike the eukaryotic cells, E.coli lacks elaborate trafficking machinery, and expressed polytopic membrane proteins are directly incorporated into the inner membrane (32). However, if the expressed protein is misfolded, it would form inclusion bodies in the cytoplasm. Studies by MacKinnon's group showed that overexpressed KvAP could be extracted in milligram quantities with dodecylmaltoside and functionally reconstituted (28). Since inclusion bodies are insoluble in mild detergents such as dodecylmaltoside, this finding suggests that the majority of KvAP was inserted into the E.coli membrane. Under our experimental conditions, expression levels are even lower. Since low level expression is known to reduce inclusion body formation and to promote membrane insertion (33), we expect that the vast majority, if not all, of expressed KvAP (and its mutants) was inserted into the inner membrane. We cannot completely rule out poor membrane insertion of some mutants, but the fraction of such mutants in our large screen is likely to be very low. Moreover, any anomalous accessibility result from such mutants could be identified because they would be expected to impact the scan pattern, for example by indicating an accessible residue in the middle of a perfect water-inaccessible transmembrane segment.

Membrane-aqueous boundaries of S1 and S2

Having validated the method, we first examined the accessibility of residues starting from the N-terminal end of S1 to C-terminal end of S2 using AMS alone (21 to 85) and AMS with chloroform (21 to 41; 65 to 85) (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1). The data show that cysteines introduced at positions 30 to 47 in S1 and 57 to 74 in S2 (Fig. 2A & B, summarised in 2C, far left) are inaccessible to AMS. Cysteines at positions 49 (S1) and 76-77 (S2) were inaccessible to AMS despite the accessibility of deeper residues, which could be due to uneven membrane-aqueous border at these positions. These data highlight a stretch of 18 consecutive inaccessible residues in both S1 and S2, long enough to cross the plasma membrane. We do not know precisely how deep AMS could penetrate into the lipid, but given the small size of the maleimide group (∼2 Å) and its close proximity to the negatively charged sulphonate moiety (Fig. 1B), we do not expect this reagent to penetrate deep into the bilayer. Moreover, the phosphate lipid head groups may even restrict deeper entry of AMS into the bilayer through electrostatic repulsion with its sulphonate group.

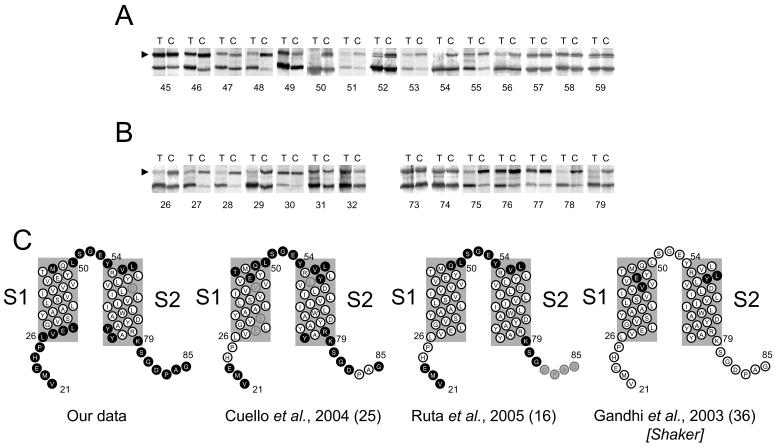

FIGURE 2. Extra- and intra-cellular accessibility of cysteines at the membrane-aqueous borders of S1 and S2.

A and B, gel-shift assay was performed on the indicated cysteine mutants as described in Fig. 1C using AMS alone (A) or AMS plus chloroform (B); lanes T and C of each panel represent data from test (pre-treated with AMS or AMS/chloroform) and control (no pre-treatment) experiments; representative data from the same experiment and gel, edited together for clarity. The top band (indicated by arrowhead) on each gel corresponds to PEGylated KvAP. C, cartoon topology of KvAP residues 21 to 85 (helices based on the crystal structure of the isolated VSD (1ORS), summarising our accessibility data (see Supplementary Figure 6 for a full scan), compared with previous studies; filled circles, accessible; open circles, inaccessible; grey circles, untested. For Shaker accessibility data KvAP equivalents are shown.

Fig. 2C compares our results with the previous data. At the extracellular end, the membrane-aqueous boundaries of S1 and S2 deduced from our data compares well with other studies (16;25). In the Shaker channel, however, MTSET showed deeper accessibility, which may be attributed to the chemical nature of the reagent: MTSET has a positive charge that might be stabilised by the negative charges of phospholipid head groups, thereby enabling access of the reagent to deeper positions. However, at the cytosolic side of the membrane we observed a consistently deeper accessibility (also true for S3 and S4; see later and Figs. 3 and 4). To test whether this is due to chloroform application, we tested its effects on the AMS accessibility of extracellular ends of S1 and S4, which are thought to represent the immobile and mobile segments of the VSD respectively. Chloroform, however, does not alter the AMS accessibility by more than one residue into the membrane (Supplemental Fig. 2). Thus the increased accessibility at the intracellular side of the membrane could be attributed to the differences between the native and reconstituted systems. It is known that the distribution of lipids in the native membrane bilayer, unlike the reconstituted systems, is asymmetrical and that the outer leaflet of the membrane represents a greater barrier to water movement than the inner leaflet (34). This may explain the greater accessibility of residues at the intracellular end to smaller water soluble reagents.

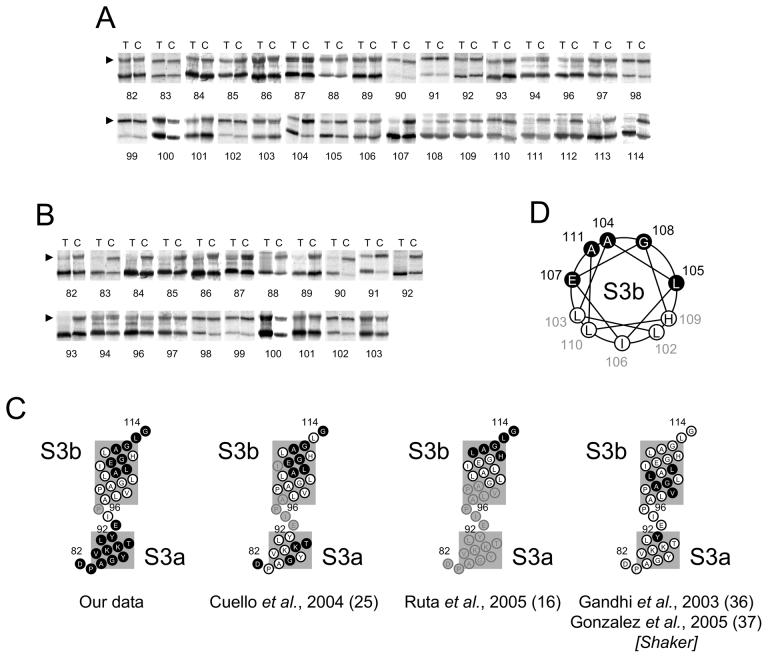

FIGURE 3. Extra- and intra-cellular accessibility of cysteines engineered into the S3 segment and its flanking regions.

A and B, gel-shift assay showing extra- and intra-cellular accessibilities (details are as described for Fig. 2A & B). (C) Summary of accessibility data, compared with other works, presented as in Fig. 2C. D, helical wheel diagram of the S3b helix showing the accessible residues (filled circles) on one face of the helix.

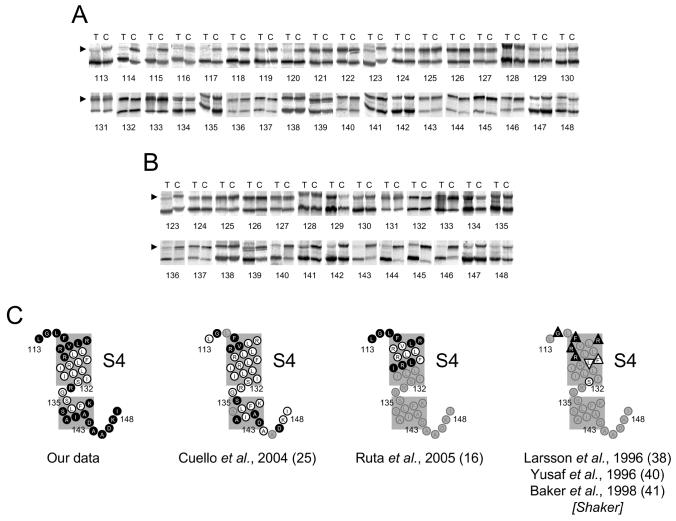

FIGURE 4. Extra- and intra-cellular accessibility of cysteines engineered into the S4 segment and its flanking regions.

A and B, gel-shift assay showing extra and intra-cellular accessibilities (details are as described for Fig. 2A & B). C, summary of accessibility data, compared with other works, presented as in Fig. 2C. For Shaker accessibility data (last cartoon) KvAP equivalents are shown; triangles represent accessible (▲, extracellular) and inaccessible (△, extracellular; ▽, intracellular; ○, both sides) residues where tested.

Membrane-aqueous boundaries of S3

When we examined the accessibility of the S3 segment, we found a total of 12 or 13 inaccessible residues, with the status of P95 undetermined due to non-expression of P95C (Fig. 3A & B). Not only is the size of the inaccessible region small, but the pattern is markedly different to that of S1 and S2: we see a stretch of 10 inaccessible residues (94 to 103) followed at the extracellular end by both accessible (104, 105, 107, 108 and 111; 104 and 105 are partially accessible) and inaccessible (102, 103, 106, 109 and 110) residues. The small inaccessible region would be consistent with the crystal structures of KvAP, where S3 is divided into two short helices and the separating non-helical linker region extends a longer distance in the membrane compared with an α-helix (see Fig. 5B). Interestingly, the entire S3a helix was found to be accessible from inside, indicating the presence of large water-filled cavity, rather than a narrow crevice at the intracellular aspect of the VSD. This conclusion is consistent with the estimates from studies of low ionic strength on charge movement (35).

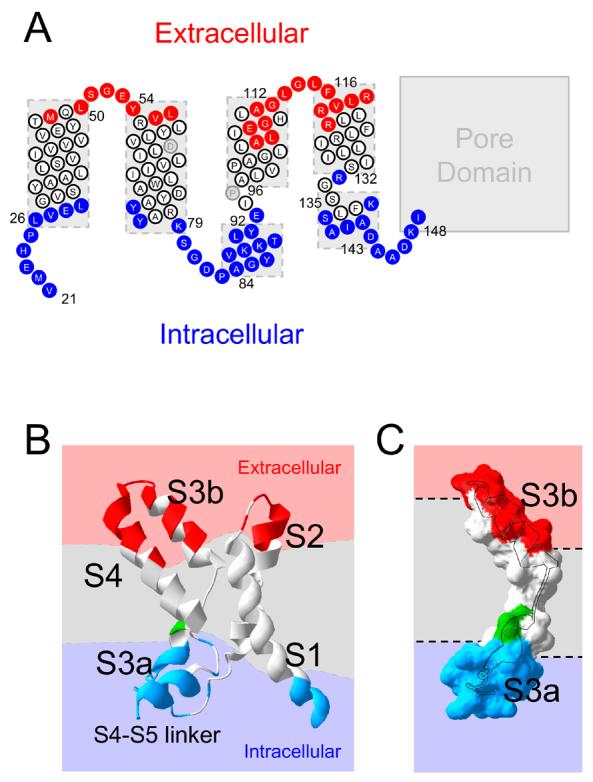

FIGURE 5. Summary of aqueous accessibility study on the KvAP voltage-sensing domain.

A, cartoon topology of KvAP residues 21 to 148 based on the crystal structure of the isolated KvAP voltage-sensor (1ORS), depicting the water accessible residues (data from Figs. 2 to 4); red circles, extracellular; blue circles, cytosolic; white circles, inaccessible; grey circles, untested. B, structure of the VSD, showing the water inaccessible membrane region (grey) separating the extracellular (red) and intracellular (blue) solutions; the dashed lines represent the approximate boundaries. Accessible regions of the protein are colour coded: red, extracellular; blue, intracellular. C, surface representation of S3 showing highly accessible regions of S3a and S3b, with the helices superimposed; colour code and orientation is as for B.

S3b showed variable extracellular accessibility, but no intracellular accessibility. When mapped on to an α-helix, all accessible residues of S3b fall on one face of the helix (Fig. 3D). This suggests that S3b might be tilted with the accessible face towards the extracellular solution. It should, however, be noted that while in all crystal structures of KvAP (11), S3 is broken into S3a and S3b, in Kv1.2 it appears to be a single helix (10). If S3 were a single helix, and therefore compact, then S3 would be expected to span even shorter distance in the membrane, leaving much deeper water crevices at either end of S3. The accessibility of S3b is consistent with the EPR data on KvAP (25). With the Shaker channel, MTSET was reported to access much deeper positions (36;37), but this could be attributed to the ability of MTSET to enter deeper into the bilayer (see above). These findings support the existence of an aqueous crevice lined by one face of S3b. In the avidin capture assay, which was designed to avoid residues in aqueous crevices, positions deeper than 109 were inaccessible (16).

Membrane-aqueous boundaries of S4

S4 is the key component of the VSD and its exposure to extracellular solvent during channel activation has been confirmed by different technical approaches (16;19;38-41). Fig. 4A shows that at the extracellular end, a stretch of several consecutive S4 residues are accessible to AMS up to position 120. Since this position was reported to be accessible only in the activated state (19), it seems reasonable to assume that under the conditions of our experiment S4 is in its ‘up’ state. In support of this, we see no accessibility for nine consecutive positions (124 to 132) at the intracellular end of S4 for KvAP; the corresponding region in Shaker is inaccessible only in the ‘up’ state (41). Thus S4 appears to remain mostly in its ‘up’ state during the course of incubation with AMS.

There are two accessible positions, 123 and 133 that fall within a stretch that is largely inaccessible. These results, however, require cautious interpretation because these mutations most likely affect the structural integrity of the channel: R123 is engaged in an important salt-bridge with a negatively charged residue in the VSD (9) and the equivalent of R133 in Shaker, R377, is critical for channel maturation and function (42).

At the intracellular end, accessibility is seen for residues 139 to 148. This region includes the C-terminal end of the S4-S5 helix and the linker that connects it to the bottom of S5. The border residues of the S4-S5 helix are not clearly defined in the KvAP crystal structures, but based on a homology model built on the Kv1.2 structure, residues 135-143 are thought to comprise the S4-S5 linker (10). Five residues of this helix and following linker residues are accessible to AMS/chloroform. Compared with the EPR study (25), we found more positions in the S4-S5 helix accessible to intracellular water. Another noticeable difference was the complete accessibility of residues (144-148) linking the S4-S5 helix to S5 compared with one residue in the EPR study.

The S4 accessibility data suggest that the expressed channel is predominantly in its activated state. Consistent with this is the observation that heterologous expression of KvAP is toxic to E. coli and that the toxicity could be prevented with Ba2+, a blocker of Kv channels in their open state (28). The membrane potential of the inner membrane of E. coli is thought to very negative, in the region of −100 mV. In lipid bilayer experiments, KvAP does not begin to activate until −60 mV. If the properties of KvAP in the native membrane were similar to that recorded from artificial bilayers (28), then one would expect the expressed channels to be closed in E. coli. The finding that this is not the case suggests that in the native environment, KvAP is activated at a far more negative potential than in the artificial bilayers. Such an explanation would be consistent with the recent evidence that the voltage dependence of KvAP activation is greatly influenced by the lipid composition of the cell membrane (26).

Conclusions

By systematically examining the accessibility of each position, we have deduced the contour of the membrane-aqueous border of the VSD of KvAP in its activated conformation. The results demonstrate that water-inaccessible regions of S1 and S2 correspond to the standard width of the membrane bilayer (∼28 Å), but those of S3 and S4 are considerably shorter (≥ 40 %; Fig. 5B). When the accessibility data are mapped on to the structure of the isolated VSD, the results reveal the location of aqueous crevices at both the extracellular and intracellular ends of the VSD, separated by a well-defined membrane buried region (see supplemental movie). It is likely that the crevices run much deeper into the interior of the VSD than revealed in our experiments, because the size of our probe is larger than water. The high degree of water accessibility can explain the proton-conducting properties of mutated VSDs of voltage-gated potassium (12) and sodium (14) channels and the Hv1 channel (7).

Thus the VSD of KvAP appears to be similar to that of eukaryotic K channels where functional studies predicted such aqueous crevices. The current consensus is that these crevices reduce the thickness of the bilayer largely near the vicinity of S4. Our data, however, reveal that the bilayer compression is greater around S3 than S4. One face of S3b and the entire S3a were water accessible, reducing the inaccessible region of S3 to just 10 residues. The structural basis for how S3 and S4 contribute to the formation of crevices is unclear, but S4 charges may play a primary role: in an attempt to form salt bridges with the lipid phosphates at the membrane-aqueous interface, the S4 arginines are thought to cause the bilayer to incurvate (to produce a biconcave effect) and produce hydrated crevices (11;23;24;26). S4 has arginines in the outer and inner leaflets that may contribute to the formation of extracellular and intracellular water crevices respectively. The S4-induced compression of the bilayer may cause S3 to adopt a conformation that would support the aqueous crevices. The structure of S3 appears to be well suited for this purpose since it is inherently flexible: positions of S3a, S3b and the S2-S3 linker are different in different crystal structures of KvAP. Molecular dynamics simulations also support the inherent flexibility of the S3, supporting the important role that it could play in voltage-sensing (43).

The absence of crevices surrounding S1 and S2 indicates that they do not line the walls of the crevices and they probably do not move much during voltage sensing. On the other hand, the extensive exposure of S3 to water, together with the finding that S3a is the most dynamic region of the VSD (25), indicates that S3 helices likely undergo large movements in concert with S4 during gating. We propose that co-ordinated movements of S3 could modulate the configuration of crevices during gating, thereby reducing the energy barrier for translocation of significant number of S4 gating charges (∼13e) across the membrane electric field.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Prof. R. MacKinnon for the KvAP clone and the co-ordinates of the KvAP model. This work is supported by the Wellcome Trust (Grant 076280/Z/04/Z).

References

- 1.Sigworth FJ. Q.Rev.Biophys. 1994;27:1–40. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500002894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bezanilla F. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:555–592. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.2.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swartz KJ. Nat.Rev.Neurosci. 2004;5:905–916. doi: 10.1038/nrn1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tombola F, Pathak MM, Isacoff EY. Annu.Rev.Cell Dev.Biol. 2006;22:23–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.020404.145837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hille B. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes. Third Ed. Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates,Inc.; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murata Y, Iwasaki H, Sasaki M, Inaba K, Okamura Y. Nature. 2005;435:1239–1243. doi: 10.1038/nature03650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramsey IS, Moran MM, Chong JA, Clapham DE. Nature. 2006;440:1213–1216. doi: 10.1038/nature04700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sasaki M, Takagi M, Okamura Y. Science. 2006;312:589–592. doi: 10.1126/science.1122352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang Y, Lee A, Chen J, Ruta V, Cadene M, Chait BT, MacKinnon R. Nature. 2003;423:33–41. doi: 10.1038/nature01580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Long SB, Campbell EB, MacKinnon R. Science. 2005;309:897–903. doi: 10.1126/science.1116269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee SY, Lee A, Chen J, MacKinnon R. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2005;102:15441–15446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507651102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Starace DM, Bezanilla F. Nature. 2004;427:548–553. doi: 10.1038/nature02270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tombola F, Pathak MM, Gorostiza P, Isacoff EY. Nature. 2007;445:546–549. doi: 10.1038/nature05396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sokolov S, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Neuron. 2005;47:183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sokolov S, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Nature. 2007;446:76–78. doi: 10.1038/nature05598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruta V, Chen J, MacKinnon R. Cell. 2005;123:463–475. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahern CA, Horn R. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:303–307. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elliott DJ, Neale EJ, Aziz Q, Dunham JP, Munsey TS, Hunter M, Sivaprasadarao A. EMBO J. 2004;23:4717–4726. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang Y, Ruta V, Chen J, Lee A, MacKinnon R. Nature. 2003;423:42–48. doi: 10.1038/nature01581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahern CA, Horn R. Neuron. 2005;48:25–29. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phillips LR, Milescu M, Li-Smerin Y, Mindell JA, Kim JI, Swartz KJ. Nature. 2005;436:857–860. doi: 10.1038/nature03873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chanda B, Asamoah OK, Blunck R, Roux B, Bezanilla F. Nature. 2005;436:852–856. doi: 10.1038/nature03888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freites JA, Tobias DJ, von Heijne G, White SH. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2005;102:15059–15064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507618102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bond PJ, Sansom MS. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2007;104:2631–2636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606822104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cuello LG, Cortes DM, Perozo E. Science. 2004;306:491–495. doi: 10.1126/science.1101373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmidt D, Jiang QX, MacKinnon R. Nature. 2006;444:775–779. doi: 10.1038/nature05416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones PC, Sivaprasadarao A, Wray D, Findlay JB. Mol.Membr.Biol. 1996;13:53–60. doi: 10.3109/09687689609160575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruta V, Jiang Y, Lee A, Chen J, MacKinnon R. Nature. 2003;422:180–185. doi: 10.1038/nature01473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bogdanov M, Heacock PN, Dowhan W. EMBO J. 2002;21:2107–2116. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.9.2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loo TW, Clarke DM. J.Biol.Chem. 1995;270:843–848. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.2.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu J, Deutsch C. Biochemistry. 2001;40:13288–13301. doi: 10.1021/bi0107647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Gier JW, Luirink J. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40:314–322. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grisshammer R, White JF, Trinh LB, Shiloach J. J.Struct.Funct.Genomics. 2005;6:159–163. doi: 10.1007/s10969-005-1917-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krylov AV, Pohl P, Zeidel ML, Hill WG. J.Gen.Physiol. 2001;118:333–340. doi: 10.1085/jgp.118.4.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Islas LD, Sigworth FJ. J.Gen.Physiol. 2001;117:69–89. doi: 10.1085/jgp.117.1.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gandhi CS, Clark E, Loots E, Pralle A, Isacoff EY. Neuron. 2003;40:515–525. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00646-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gonzalez C, Morera FJ, Rosenmann E, Alvarez O, Latorre R. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2005;102:5020–5025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501051102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Larsson HP, Baker OS, Dhillon DS, Isacoff EY. Neuron. 1996;16:387–397. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang N, George AL, Jr., Horn R. Neuron. 1996;16:113–122. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yusaf SP, Wray D, Sivaprasadarao A. Pflugers Arch. 1996;433:91–97. doi: 10.1007/s004240050253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baker OS, Larsson HP, Mannuzzu LM, Isacoff EY. Neuron. 1998;20:1283–1294. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80507-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tiwari-Woodruff SK, Schulteis CT, Mock AF, Papazian DM. Biophys.J. 1997;72:1489–1500. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78797-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sands ZA, Sansom MS. Structure. 2007;15:235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.