Abstract

Decreased renal neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) is present in various chronic kidney diseases although there is relatively little known in CAN. Female sex increases the risk of acute rejection and calcineurin-inhibitor toxicity but decreases the risk of chronic allograft nephropathy (CAN). Rapamycin (RAPA) is an alternative immunosuppress although there is no information whether it is effective in females. We therefore investigated the efficacy of RAPA in both sexes and the impact of RAPA on renal cortex structure and nNOS expression. Male (M) and female (F) F344 kidneys were transplanted into same sex Lewis (ALLO) or F344 (ISO) recipients and treated with 1.6 mg/kg/day of RAPA for 10 days. Grafts were removed for renal histology and endothelial (e)NOS and neuronal (n)NOS protein measurements at 22 weeks. All ALLO rats survived without acute rejection. ALLO F survived with mild proteinuria and CAN at 22 weeks similar to ALLO M, while ISO F had better outcome than ISO M. Cortical nNOSα was undetectable in all RAPA groups; however, nNOSβ transcript and protein were compensatory increased. Both ALLO and ISO F showed higher medullary nNOSα but lower cortical eNOS abundance than M groups. In male ALLO RAPA decreased renal cortical nNOSα but increased nNOSβ expression. This may represent compensatory upregulation of nNOSβ when nNOSα-derived NO is deficient.

Keywords: chronic allograft nephropathy, immunosuppression, kidney transplant, neuronal nitric oxide synthase

Introduction

Women have a higher risk of acute rejection following renal transplantation (Tx) but a lower risk of graft loss secondary to chronic allograft nephropathy (CAN) [1]. Although calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) have improved 1-year survival rates for kidney grafts, the long-term graft outcome is not improved [2], perhaps reflecting ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury and CNI-related nephropathy. Female recipients are resistant to I/R injury but vulnerable to CNI-related nephropathy [3], and we have observed that female rats require a higher dose of CNI to suppress acute rejection (unpublished data). Thus, it is possible that in women the long-term graft outcome may be improved when alternative immunosuppression is used that is sufficient to prevent acute rejection but without nephrotoxicity.

Rapamycin (RAPA), a mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor, is used as a substitute for, or given in combination with CNIs to prevent rejection and reduce nephrotoxicity. In male rats, a wide therapeutic dosage of RAPA between 0.3–6 mg/kg/day was effective for prolongation of allograft survival [4] although RAPA at 6.5mg/kg/day resulted in acute nephrotoxicity in a male rat isograft model with I/R [5]. There is no data on the impact of sex differences in terms of graft outcome using RAPA for immunosuppression.

Nitric oxide (NO) derived from inducible (i)NOS has been implicated in Tx rejection, while NO derived from constitutive NOS might protect the allograft [6]. In the CAN model, little attention has been paid to the constitutive NOS. We previously reported that decreased renal neuronal (n)NOS abundance was associated with renal injury in a wide variety of chronic kidney disease (CKD) models [7] and that preserved renal nNOS in aging females was associated with protection from age-dependent CKD [8].

In the present study we therefore investigated the long-term (22w) graft outcome of renal Tx and renal nNOS expression with short-term (10d) moderate dose of rapamycin (1.6mg/kg/day). In order to separate primary immunological influences from I/R injury, studies were performed in RAPA-treated allografts (ALLO) and isografts (ISO) of both sexes.

Materials and Methods

Orthotopic renal Tx was performed as described previously with the exception that full sterile technique was employed [9]. Briefly, rats were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of a mixture of pentobarbital sodium (32.5 mg/kg BW, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and methohexital sodium (Brevital sodium, 25 mg/kg BW, Eli Lilly and Co, Indianapolis, IN). After median laparatomy left renal vessels and ureter of the recipient were isolated, clamped and the native kidney removed. The left donor kidney was perfused with cold (4°C) lactated Ringer solution, removed and positioned orthotopically into the recipient. Donor and recipient renal artery, vein and ureter were end-to-end anastomized with 10-0 prolene sutures. Cold ischemic time was 10 minutes and the warm ischemic time was 20 minutes.

Inbred female and male Fisher 344 (F344, RT1v1, from Harlan Indianapolis, USA) served as donors. Lewis (LEW, RT1, from Harlan, Indianapolis, USA) female and male rats were used as recipients in the RAPA ALLO groups (F=6, M=7), while F344 female and male rats were used in the RAPA ISO groups (F=6, M=7). Donors and recipients were always of the same sex in every Tx performed. All rats were aged 9–14 weeks and maintained with free access to standard rat chow and water ad libitum.

In the RAPA series Tx recipients were treated for the first 10 days after surgery with rapamycin derivative sirolimus (1.6 mg/kg/day; Rapamune, Wyeth Laboratories, Philadelphia, PA) by gavage. Rats also received the antibiotic ceftriaxone sodium, 10 mg/kg/day (Rocephin, Roche, Nutley, NJ) i.m. for 10 days. In addition, other ALLO male (n=5) and female (n=4) were administered with 3 mg/kg/day cyclosporin s.c. (CsA, Sandimmune, Novartis, Basle, Switzerland) instead of RAPA for acute immunosupression but were otherwise identical. In additional to ALLO rats, 2-kidney age-matched male rats (n=5) were also used as age control.

Following 24 hours on low NOx (= NO2 + NO3) diet (ICN, AIN 76), 24-hour urine samples were collected in metabolic cages at 22 wks after Tx for determination of urinary NOx and total protein excretion. Just prior to sacrifice, blood pressure (BP) was measured, under general anesthesia (as used for Tx) and a blood sample taken for analysis of plasma creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN). All analyses were performed as described previously [10]. Kidneys were then perfused until blood-free, decapsulated, removed and weighed. A thin section of kidney including cortex and medulla was fixed for histology and the remaining cortex and medulla was separated, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for later analysis.

Kidney sections were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, blocked in paraffin and 5 µm sections were stained with periodic acid-Schiff and slides were examined in a blinded manner by one author (AS). Glomerular sclerosis, interstitial, tubular, and vascular lesions were graded according the Banff classification.

Renal nNOS and eNOS abundance were determined by Western blot as described previously [10]. Briefly, measurement was conducted on kidney cortex (200 µg total protein) and kidney medulla (100 µg total protein) for nNOS and eNOS. In addition, cerebellum (5 µg) and skeletal muscle (150 µg) were used for detection of nNOS. For nNOSα we used an N-terminal rabbit polyclonal antibody kindly provided by Dr Kim Lau (1:5000 dilution, one hour incubation at room temperature). For nNOSβ detection we used a C-terminal rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:250 dilution, overnight incubation, Affinity BioReagents, Golden, CO). A goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP secondary antibody (1:3000 dilution, one hour incubation, Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA) was used for nNOS detection. Membranes were stripped and reprobed for eNOS (mouse monoclonal antibody, 1:250 dilution, one hour incubation; secondary antibody goat, anti-mouse IgG-HRP, 1:2000 dilution, one hour incubation, Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY).

NOS protein abundance was calculated as integrated optical density (IOD) of nNOS or eNOS factored for Ponceau red stain (total protein loaded) and for an internal standard (endothelial cell lysate for eNOS and rat cerebellum for nNOS) and expressed as a percent change from the respective control value. This allowed quantitative comparisons between different membranes. The protein abundance was represented as IOD/Int Std/Ponc.

End-point RT-PCR was used for semi-quantitative analysis of mRNA as previously published [11]. Briefly, RNA was isolated from tissue using TRI Reagent (Sigma, St.Louis, MO, USA) and treated with DNase I (Ambion, Austin TX, USA). RNA (1 µg) was reversed transcribed (RT; SuperScriptTM II RNase H-Reverse Transcriptase, Invitrogen, Bethesda, MD, USA) with random primers (Invitrogen, Bethesda, MD, USA) in a total volume of 20 µl. Primers were designed using GeneTool Software (Biotools Incorporated, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada) with annealing temperatures at 58–61°C. Ribosomal 18S (r18S; Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) was used as an internal reference since r18S expression remained constant throughout. For nNOSα and nNOSβ, a forward primer targeting Exon 1a, a 5’ untranslated region (5’UTR), was made according to Lee et al. [12] and reverse primers targeting exon 2 (R2:5′ tccgcagcacctcctcgaatc 3′) and exon 6 (R6: 5′ gcgccatagatgagctcggtg 3′) were designed from rat-specific sequences (NM_052799). For each primer set, the cDNA from all samples was amplified simultaneously using aliquots from the same PCR mixture. PCR was carried out using 1-0.5 µg of cDNA, 50ng of each primer, 250 µM deoxyribonucleotide triphosphates, 1 × PCR Buffer, and 2 units Taq DNA Polymerase (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) in a 50 µl final volume. Following amplification, 20 µl of each reaction was electrophoresed on 1.7% agarose gels. Gels were stained with ethidium bromide, images were captured and the signals were quantified in arbitrary units (AU) as optical density × band area using a VersaDoc Image Analysis System and Quantity One, v.4.6 software (Bio-rad, Hercules, CA, USA). PCR signals were normalized to the r18S signal of the corresponding RT product to provide a semi-quantitative estimate of gene expression.

Results are presented as mean±SEM. Parametric data was analysed by t-test and ANOVA. Nonparametric data was analysed by the Mann-Whitney test. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

All RAPA ALLO and ISO rats survived to 22 weeks post TX. As shown in Table 1 both body weight and Tx kidney weights were higher in males vs. females. BP was lower in ALLO vs. ISO groups possibly reflecting a lower BP in the Lew ALLO recipients. With the exception of the ISO females, the other 3 Tx groups developed proteinuria. The ISO females had lower plasma Cr than ISO males and ALLO females and males, while BUN levels were lower in both ISO males and females compared to respective ALLO groups.

Table 1.

Functional parameters in 4 groups 22 weeks after transplantation

| BW (g) | TX kidney weight (g) | BP (mmHg) | UprotV (mg/day) | UNOxV (µM/day/100g BW) | PCr (mg/dl) | BUN (mg/dl) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISO F n=6 | 220±1# | 1.24±0.11# | 91±3 | 6.7±2.4# | 1.31±0.08 | 0.33±0.03*# | 21±1* |

| ISO M n=7 | 435±4 | 2.38±0.11 | 98±2* | 69.7±12.7 | 1.06±0.02* | 0.42±0.02 | 21±1* |

| ALLO F n=6 | 224±7# | 1.29±0.05# | 81±9 | 26.2±17.7 | 1.28±0.06 | 0.42±0.02 | 26±1 |

| ALLO M n=7 | 436±9 | 2.21±0.12 | 79±5 | 37.4±16.6 | 1.45±0.17 | 0.49±0.03 | 26±1 |

p<0.05 vs. respective ALLO group

p<0.05 vs. respective M group.

TX weight= transplanted kidney weight.

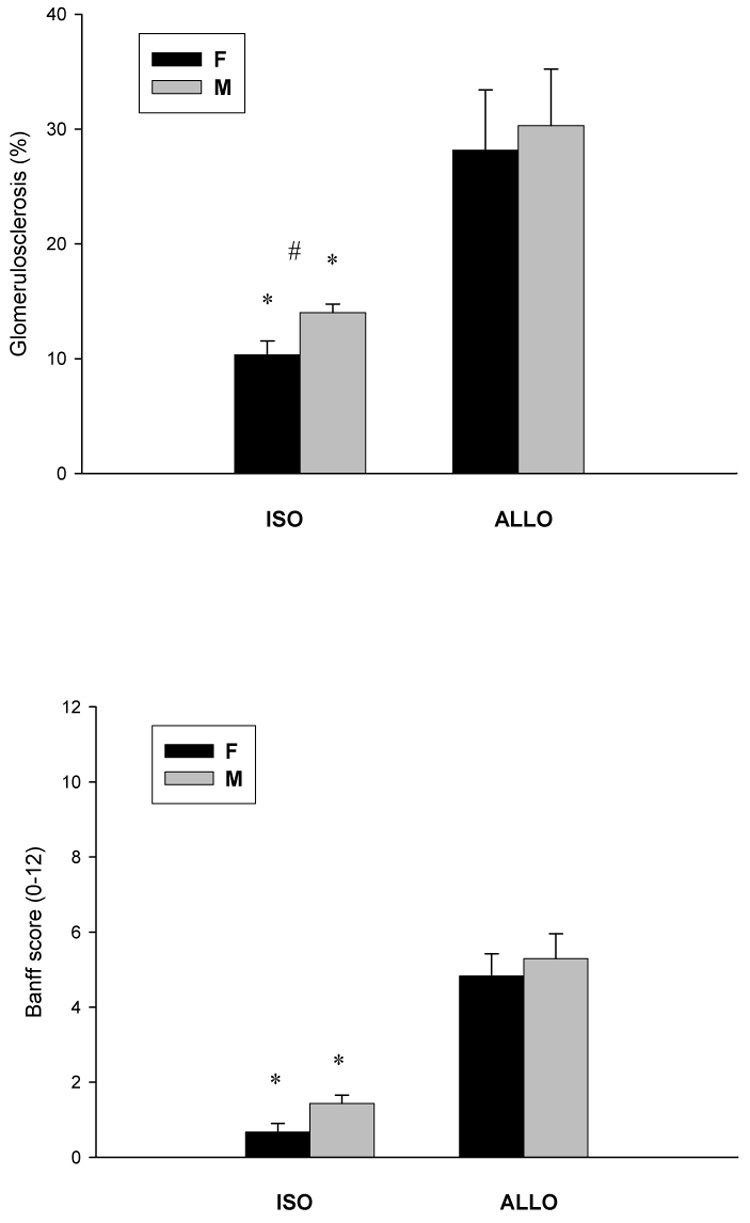

ALLO males and females exhibited significantly more sclerotic glomeruli than their respective ISO groups (Figure 1). Banff score summarizing glomerular, tubular, interstitial and vascular changes demonstrated more severe injury in ALLO groups compared to those in ISO groups. The ISO females had significantly less glomerulosclerosis vs. ISO males.

Figure 1.

(A) Glomerulosclerois and (B) Banff score in ISO and ALLO grafts 22 weeks after Tx. *p<0.05 vs. respective ALLO group, #p<0.05 vs. respective M group.

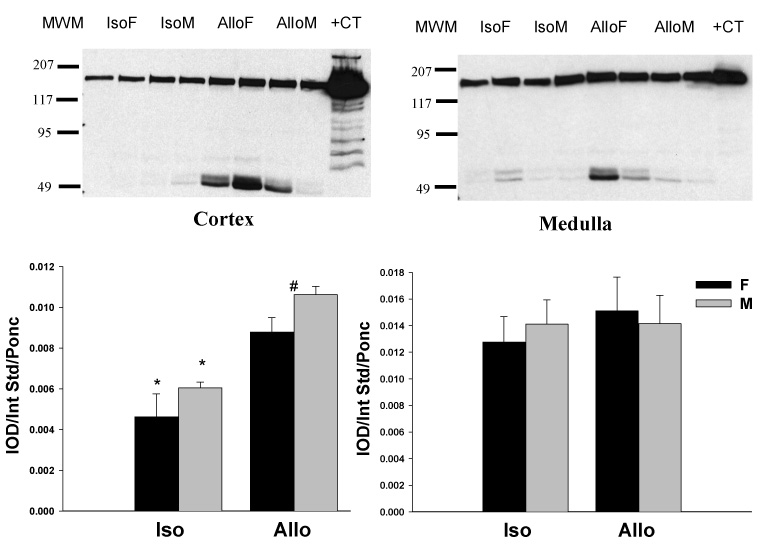

Total NO production, reflected by 24h urinary NOx excretion, was slightly reduced in ISO males compared to the other 3 RAPA-treated groups. In renal cortex, eNOS protein abundance was higher in both ALLO males and females vs. their respective ISO groups (Figure 2, left panel). ALLO males also had higher eNOS expression than ALLO females. In kidney medulla, there was no difference in eNOS expression among the 4 groups (Figure 2, right panel).

Figure 2.

Renal cortical (left panel) and medullary (right panel) eNOS protein abundance in ISO and ALLO grafts 22 weeks after Tx. Representative western blot whole membranes show eNOS bands (~155kDa). The molecular weight marker is in the first line. +CT represents positive control. *p<0.05 vs. respective ISO group, #p<0.05 vs. respective M group.

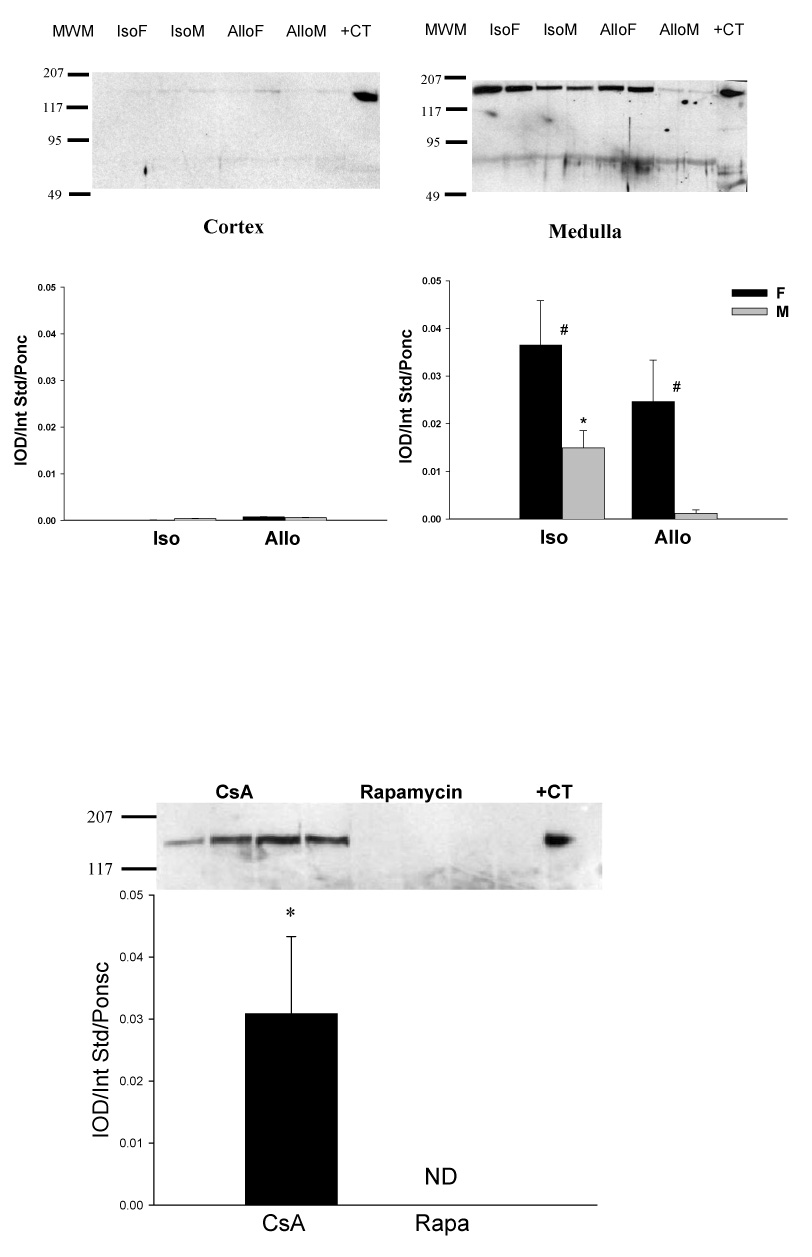

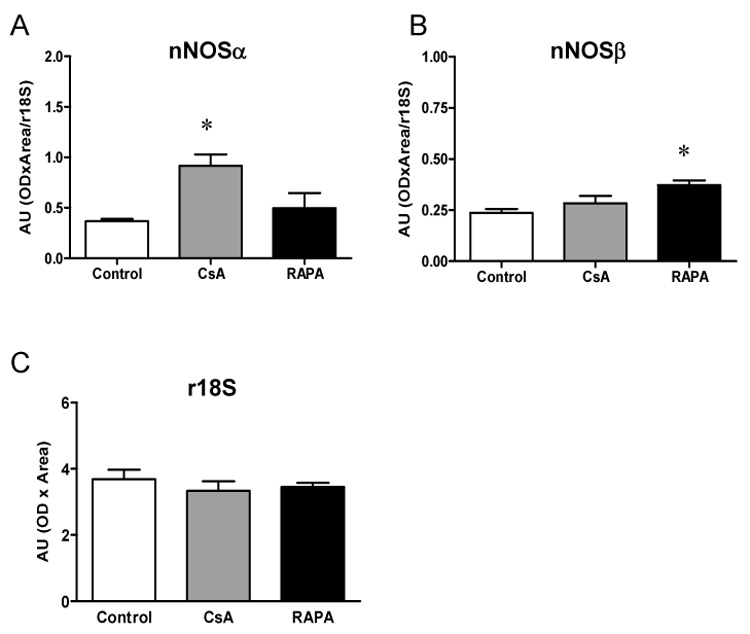

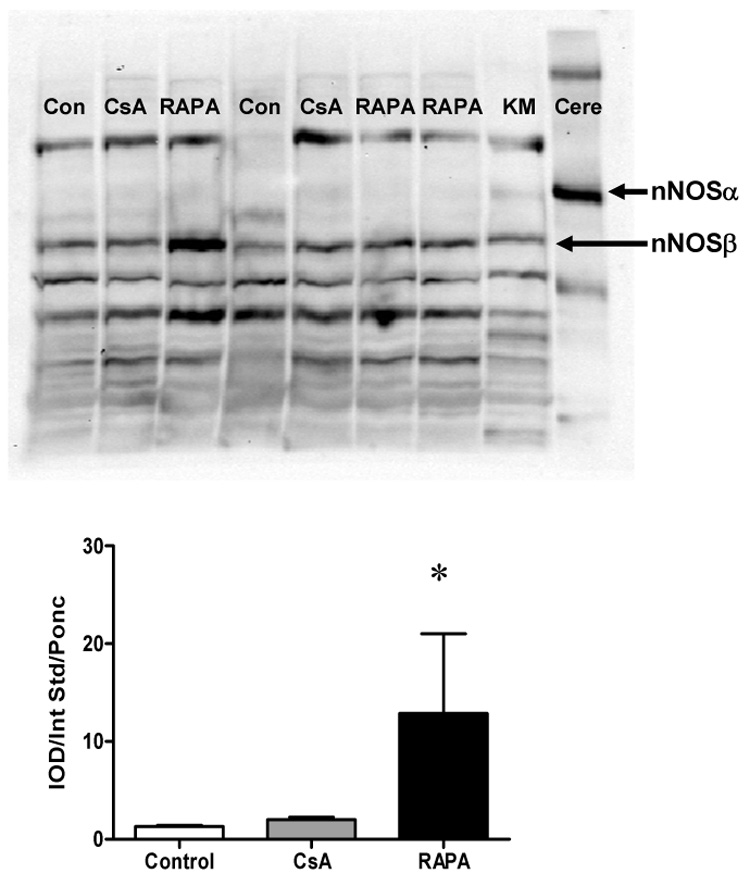

Using the N-terminal antibody, cortical nNOSα protein was nearly undetectable in all RAPA groups (Figure 3A, left panel). We re-ran ALLO female kidneys treated with CsA (N=4) and those treated with RAPA (N=4) on the same membrane (Figure 3B), and confirmed that nNOSα was absent in the RAPA treated kidney cortex. In contrast, there was no difference in nNOSα abundance in skeletal muscle (0.0076 ± 0.0005 vs. 0.0084 ± 0.0005 IOD/Int Std/Ponc) and cerebellum (0.0064 ± 0.0024 vs. 0.0088 ± 0.0006 IOD/Int Std/Ponc) between CsA and RAPA female rats. In renal medulla, a lower nNOSα abundance was observed in both ISO and ALLO males vs. respective females and nNOSα protein was nearly undetectable in the ALLO male group. As shown in Fig 4, nNOSα mRNA significantly increased in ALLO males treated with CsA compared to controls (Fig 4A), whereas nNOSβ mRNA significantly increased in ALLO males treated with RAPA (Fig 4B). Using the C-terminal nNOS antibody, nNOSβ protein (~140kDa) was detected in the cortex of controls, ALLO-CsA and ALLO-RAPA males and was significantly elevated compared to controls (Fig 5). We did not probe the ISO or female kidneys for nNOSβ protein due to lack of available tissue.

Figure 3.

(A) Renal cortical (left panel) and medullary (right panel) nNOSα protein abundance in ISO and ALLO grafts 22 weeks after Tx. Representative western blot whole membranes show nNOSα bands (~160 kDa). The molecular weight marker is in the first line.+CT represents positive control. ND represents not detectable. *p<0.05 vs. respective ISO group, #p<0.05 vs. respective M group. (B) Renal cortical nNOSα protein abundance in CsA and RAPA treated female rats. *p<0.05 CsA vs. RAPA.

Figure 4.

Renal cortical nNOSα (A) and nNOSβ (B) mRNA abundance in CsA and RAPA treated ALLO male rats and controls (n=5 in each group). The r18S (C) was used as an internal standard. *p<0.05 vs. control.

Figure 5.

(A) Renal cortical nNOSβ protein abundance in CsA and RAPA treated male rats and controls. Representative western blot whole membranes show nNOSα band (~160 kDa) and nNOSβ band (~140 kDa). Cere represents cerebellum used as positive control for nNOSα. KM represents kidney medulla used as positive control for nNOSβ. (B) Renal cortical nNOSβ protein abundance in CsA and RAPA treated male ALLO rats and controls (n=5 in each group). *p<0.05 vs. control.

Discussion

The main novel findings of this study is that short-term RAPA treatment (10d) had a long-term (22w) effect to reduce the renal cortical nNOSα protein abundance, but with compensatory increases in the nNOSβ abundance in the ALLO males. This may explain why the almost total loss of nNOSα seen in ALLO males was only associated with relatively mild renal structural damage. In female allograft recipients RAPA monotherapy suppressed acute rejection and led to similar outcomes in male and female RAPA treated ALLO rats. There was significantly better preservation of kidney structure in the ISO females vs. males.

RAPA is an effective immunosuppressant but heavy proteinuria was reported in 31–64% of patients converted from CNI to RAPA [13,14]. Possible mechanisms include the renal hemodynamic effects of CNI withdrawal [15], reduced tubular protein reabsorption and/or increased glomerular permeability [16,17]. In our study all RAPA treated rats developed some proteinuria except for the striking protection seen in ISO females. Another important finding in this study is that in the isografts, RAPA produced less glomerulosclerosis in females than males. Thus, in the absence of an immunological challenge, female sex protects vs the RAPA –induced proteinuria and glomerular damage seen in males.

Both experimental and clinical data supports the hypothesis that progressive CKD is associated with decreased NO synthesis and animal studies have implicated a specific association with reduced renal nNOSα and development of injury [7]. In the renal mass reduction model there is a linear inverse relationship between increasing glomerular injury and decreasing renal cortical nNOSα abundance, once glomerular injury exceeds ~20 % [18]. With regard to renal Tx, experimental NOS inhibition worsens injury, while L-arginine supplementation decreases renal damage suggesting that NO plays a protective role [19,20]. In the RAPA treated kidneys there was marked reduction (near zero) in nNOSα in renal cortex in all 4 RAPA treated groups despite only ~10% and ~30% of glomerular injury in ISO and ALLO rats, respectively. To confirm this unexpected finding we ran 4 kidney cortices of ALLO female rats given RAPA on the same membrane as 4 CsA-treated ALLO females and the results were identical, ie. Minimal nNOSα was detected in RAPA vs. CsA-treated kidney cortices. This was in contrast to the renal medulla where significant nNOSα was detected in 3 out of 4 RAPA treated groups. Further, there was no difference in abundance of nNOSα in either skeletal muscle or cerebellum in RAPA compared to CsA treated rats.

Why RAPA specifically inhibits nNOSα protein expression only in renal cortex but not other nNOS abundant tissues is unclear. One possibility is that tubular reabsorption and concentration of RAPA leads to elevated tissue concentrations compared to e.g. skeletal muscle [21] and that the nNOSα isoform may be particularly sensitive to RAPA. There is no data available on the impact of RAPA on nNOS expression although RAPA induced increases in aortic eNOS protein expression have been reported in Apo E knock out mice [22]. Most of our studies in CKD have used a polyclonal antibody recognizing N-terminal aa #1-231 of nNOS, thus specifically detecting nNOSα in kidney. We have recently identified another nNOS isoform, the nNOS β protein, in the rat kidney [23]. The nNOSβ has an N-terminal deletion and consists of aa #236-1433 of nNOSα. Using an nNOS antibody targeted to the C-terminal, we have observed bands at both the nNOSα and −β molecular weights. We have also detected both the nNOSα and nNOSβ mRNA and find that ALLO male rats given RAPA showed increases in both nNOSβ mRNA and protein abundance vs. CsA treated male rats. Since NOSβ has ~80% the activity of nNOSα in vitro [24], this suggests that the increased nNOSβ compensates for the decreased nNOSα activity in response to RAPA. Thus the total nNOS abundance is only slightly reduced which accords with the relatively mild renal injury. We were only able to analyze nNOSβ expression in ALLO male rats in this study (because of size limitations of the female kidneys), and therefore possible sex differences need to be evaluated in future studies. We found that both ALLO and ISO F showed higher medullary nNOSα but lower cortical eNOS abundance than M groups; however, these changes are not correlated to graft outcomes.

In summary, RAPA monotherapy effectively suppressed initial post-Tx immune reactions and prevent acute rejection in female rats as well as in males. RAPA resulted in profound decreases in cortical nNOSα in all 4 groups. Both nNOSβ mRNA and protein were increased in RAPA-ALLO males compared to CsA-ALLO males, suggesting nNOSβ might compensate for decreased nNOSα activity. These RAPA Tx observations are part of an ongoing body of work in different CKD models in which we find a correlation between increasing renal cortical damage and declining nNOS abundance. This does not demonstrate causality, although the association is strong and the rise in nNOSβ protein in the ALLO male suggests a compensatory mechanism to limit injury. Nevertheless, it remains to be seen whether nNOS depletion is causally associated with progression of CKD.

Acknowledgements

Funding for these studies was provided by NIH grants R01 DK56843, DK45517, and OTKA (Hungarian Research Fund F 042563). The authors are grateful to Kevin Engels and Lennie Samsell for expert technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Meier-Kriesche HU, Ojo AO, Leavey SF, Hanson JA, Leichtman AB, Magee JC, Cibrik DM, Kaplan B. Gender differences in the risk for chronic renal allograft failure. Transplantation. 2001;71:429–432. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200102150-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meier-Kriesche HU, Schold JD, Kaplan B. Long-term renal allograft survival: have we made significant progress or is it time to rethink our analytic and therapeutic strategies. Am. J. Transplant. 2004;4:1289–1295. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neugarten J, Srinivas T, Tellis V, Silbiger S, Greenstein S. The effect of donor gender on renal allograft survival. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 1996;7:318–324. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V72318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DiJoseph JF, Fluhler E, Armstrong J, Sharr M, Sehgal SN. Therapeutic blood levels of sirolimus (rapamycin) in the allografted rat. Transplantation. 1996;62:1109–1112. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199610270-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ninova D, Covarrubias M, Rea DJ, Park WD, Grande JP, Stegall MD. Acute nephrotoxicity of tacrolimus and sirolimus in renal isografts: differential intragraft expression of transforming growth factor-beta1 and alpha-smooth muscle actin. Transplantation. 2004;78:338–344. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000128837.07640.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vos IH, Joles JA, Rabelink TJ. The role of nitric oxide in renal transplantation. Semin. Nephrol. 2004;24:379–388. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baylis C. Arginine, arginine analogs and nitric oxide production in chronic kidney disease. Nat. Clin. Pract. Nephrol. 2006;2:209–220. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erdely A, Greenfeld Z, Wagner L, Baylis C. Sexual dimorphism in the aging kidney: Effects on injury and nitric oxide system. Kidney Int. 2003;63:1021–1026. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00830.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muller V, Szabo A, Viklicky O, Gaul I, Portl S, Philipp T, Heemann UW. Sex hormones and gender-related differences: their influence on chronic renal allograft rejection. Kidney Int. 1999;55:2011–2020. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tain YL, Muller V, Szabo A, Dikalova A, Griendling K, Baylis C. Lack of long-term protective effect of antioxidant/anti-inflammatory therapy in transplant-induced ischemia/reperfusion injury. Am. J. Nephrol. 2006;26:213–217. doi: 10.1159/000093587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alway SE, Lowe DA, Chen KD. The effects of age and hindlimb supension on the levels of expression of the myogenic regulatory factors MyoD and myogenin in rat fast and slow skeletal muscles. Exp. Physiol. 2001;86:509–517. doi: 10.1113/eph8602235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee MA, Cai L, Hubner N, Lee YA, Lindpaintner K. Tissue- and development-specific expression of multiple alternatively spliced transcripts of rat neuronal nitric oxide synthase. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;100:1507–1512. doi: 10.1172/JCI119673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morelon E, Kreis H. Sirolimus therapy without calcineurin inhibitors: Necker Hospital 8-year experience. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:52S–57S. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(03)00244-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merkel S, Mogilevskaja N, Mengel M, Haller H, Schwarz A. Side effects of sirolimus. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:714–715. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saurina A, Campistol JM, Piera C, Diekmann F, Campos B, Campos N, de las Cuevas X, Oppenheimer F. Conversion from calcineurin inhibitors to sirolimus in chronic allograft dysfunction: changes in glomerular haemodynamics and proteinuria. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2006;21:488–493. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfi266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Straathof-Galema L, Wetzels JF, Dijkman HB, Steenbergen EJ, Hilbrands LB. Sirolimus-associated heavy proteinuria in a renal transplant recipient: evidence for a tubular mechanism. Am. J. Transplant. 2006;6:429–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Izzedine H, Brocheriou I, Frances C. Post-transplantation proteinuria and sirolimus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353:2088–2089. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200511103531922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szabo AJ, Wagner L, Erdely A, Lau K, Baylis C. Renal neuronal nitric oxide synthase protein expression as a marker of renal injury. Kidney Int. 2003;64:1765–1771. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stojanovic T, Grone HJ, Gieseler RK, Klanke B, Schlemminger R, Tsikas D, Grone EF. Enhanced renal allograft rejection by inhibitors of nitric oxide synthase: a nonimmunologic influence on alloreactivity. Lab. Invest. 1996;74:496–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Albrecht EW, van Goor H, Smit-van Oosten A, Stegeman CA. Long-term dietary L-arginine supplementation attenuates proteinuria and focal glomerulosclerosis in experimental chronic renal transplant failure. Nitric Oxide. 2003;8:53–58. doi: 10.1016/s1089-8603(02)00132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Napoli KL, Wang ME, Stepkowski SM, Kahan BD. Distribution of sirolimus in rat tissue. Clin. Biochem. 1997;30:135–142. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(96)00157-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naoum JJ, Woodside KJ, Zhang S, Rychahou PG, Hunter GC. Effects of rapamycin on the arterial inflammatory response in atherosclerotic plaques in Apo-E knockout mice. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:1880–1884. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.02.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith CA, Merchant ML, Tain YL, Klein J, Baylis C. Identification of neuronal nitric oxide synthase isoforms in the rat kidney, Abstract; J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. Meeting; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brenman JE, Chao DS, Gee SH, McGee AW, Craven SE, Santillano DR, Wu Z, Huang F, Xia H, Peters MF, Froehner SC, Bredt DS. Interaction of nitric oxide synthase with the postsynaptic density protein PSD-95 and alpha1-syntrophin mediated by PDZ domains. Cell. 1996;(84):757–767. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]