Abstract

In vitro translation systems are used to investigate translational mechanisms and to synthesize proteins for characterization. Most available mammalian cell-free systems have reduced efficiency due to decreased translation initiation caused by phosphorylation of the initiation factor eIF2α on Ser51. We describe here a novel cell-free protein synthesis system using extracts from cultured mouse embryonic fibroblasts that are homozygous for the Ser51 to- Ala mutation in eIF2α (A/A cells). The translation efficiency of a capped and polyadenylated firefly luciferase mRNA in A/A cell extracts was 30-fold higher than in wild-type extracts. Protein synthesis in extracts from A/A cells was active for at least 2 h and generated up to 20 μg/mL of luciferase protein. Additionally, the A/A cell-free system faithfully recapitulated the selectivity of in vivo translation for mRNA features; translation was stimulated by a 5′-end cap (m7GpppN) and a 3′-end poly(A) tail in a synergistic manner. The system also showed similar efficiencies of cap-dependent and IRES-mediated translation (EMCV IRES). Significantly, the A/A cell-free system supported the post-translational modification of proteins, as shown by glycosylation of the HIV type-1 gp120 and cleavage of the signal peptide from β-lactamase. We propose that cell-free systems from A/A cells can be a useful tool for investigating mechanisms of mammalian mRNA translation and for the production of recombinant proteins for molecular studies. In addition, cell-free systems from differentiated cells with the Ser51Ala mutation should provide a means for investigating cell type-specific features of protein synthesis.

Keywords: protein synthesis, in vitro translation, cell-free systems, eIF2 phosphorylation

INTRODUCTION

In vitro translation systems are commonly used for the synthesis of biologically important proteins and to investigate mechanisms of protein synthesis. Moreover, cell-free translation systems are becoming increasingly important for the production of recombinant proteins that are either toxic or difficult to express in high yields in mammalian cells (for review, see Spirin 2004; Endo and Sawasaki 2006). However, many mammalian cell-free systems have limited yield or do not reproduce the properties of translation in vivo. Although translation initiation of 5′-m7G-capped mRNAs is more efficient than uncapped mRNAs in vivo, the cap structure has a relatively small effect on the efficiency of in vitro translation initiation in rabbit reticulocyte lysate (RRL), the most widely used in vitro translation system (Svitkin et al. 1996; Endo and Sawasaki 2006).

In vivo translation studies have shown that the mRNA cap structure and poly(A) tail act synergistically to stimulate translation (Gallie 1991). The stimulation of translation by the 5′-m7G cap and 3′-poly(A) tail in nuclease-treated RRL is additive and not synergistic (Munroe and Jacobson 1990). In contrast, cell-free translation extracts from HeLa cells show synergy between the 5′-cap structure and 3′-poly(A) for efficient translation (Svitkin et al. 1996, 2001; Bergamini et al. 2000), but the efficiency of utilization of exogenous mRNAs is very low (Spirin 2004). One major mechanism that limits translation rates in vivo and in vitro is phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 (eIF2) on the α-subunit at Ser51 (eIF2α) (for review, see Hershey and Merrick 2000; Kaufman 2004). During translation initiation, eIF2, GTP, and Met-tRNAi form a ternary complex that interacts with the 40S ribosomal subunit and the translation initiation complex (Hershey and Merrick 2000; Sudhakar et al. 2000). The anticodon of the Met-tRNAi in the ternary complex base-pairs with the mRNA initiation codon, which triggers hydrolysis of the GTP and release of eIF2 in the GDP-bound form. Release of GDP from eIF2 and regeneration of eIF2-GTP is promoted by the guanine nucleotide exchange factor eIF2B. Phosphorylation of the α-subunit of eIF2 increases its affinity for GDP by 100-fold so that eIF2B cannot catalyze nucleotide exchange and remains bound to eIF2-GDP. Since the eIF2B is generally 10 times less abundant than eIF2, small increases in the level of eIF2α phosphorylation can completely inhibit polypeptide chain initiation because eIF2B becomes sequestered in an inactive form, which prevents eIF2 recycling.

In mammalian cells, four protein kinases that are activated by different cellular stress conditions are known to phosphorylate eIF2α on Ser51 (for review, see Kaufman 2004; Wek et al. 2006): GCN2 is activated by amino acid deficiency, PKR is activated by double-stranded RNA produced during viral infection, PERK is activated by the accumulation of unfolded proteins in the ER, and HRI is activated by hemin deficiency in erythroid cells. Two proteins involved in eIF2α dephosphorylation have also been described (Ron and Harding 2007). The stress-inducible GADD34 and the constitutive CRep (or PPP1R115B) proteins interact with the catalytic subunit of the PP1 phosphatase complex, enhancing the dephosphorylation of phospho-eIF2. The effects of eIF2α phosphorylation/dephosphorylation in gene expression and translation initiation in vivo have been studied extensively (Ron and Harding 2007). Phosphorylation of eIF2α has also been described as a factor that limits efficient translation in cell-free systems because this protein is phosphorylated during the translation of endogenous or added mRNAs in vitro (Mikami et al. 2006a). This phosphorylation has been explained by the activation of the eIF2α kinases in the cell-free systems. In an attempt to overcome this limitation, Imataka's group showed that protein synthesis in a hybridoma extract was increased by three- to fourfold by addition of GADD34, which stimulated eIF2α dephosphorylation (Mikami et al. 2006a). Similar results were obtained by supplementation of cell extracts with the vaccinia virus K3L protein, which can also be phosphorylated by the eIF2 kinases due to its structural resemblance to eIF2α (Nonato et al. 2002; Ramelot et al. 2002). The limiting effect of eIF2 phosphorylation on the translational efficiency of the HeLa cell-free system was shown by the increased efficiency of translation in extracts supplemented with either eIF2 or eIF2B (Mikami et al. 2006b).

In this study, we describe a cell-free translation system using extracts from mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) that have a homozygous knockin mutation (Ser51 to Ala) in the eIF2α gene (A/A). This mutant eIF2α is not a substrate for the eIF2 kinases in vivo and in vitro (Ramaiah et al. 1994; Scheuner et al. 2001). We show that extracts from A/A cells have a translational efficiency that is 30-fold greater than that of wild-type (S/S) extracts. In addition, the A/A cell-free system can recapitulate the minimum requirements for efficient mammalian translation, which are a poly(A) tail at the 3′-end and an m7G cap structure at the 5′-end of the mRNA (Sachs et al. 1997).

The synthesis of secreted and membrane proteins is accompanied by co- and post-translational modifications such as signal sequence cleavage and asparagine (N)-linked glycosylation that occur upon translocation into the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Apweiler et al. 1999; Helenius and Aebi 2004). The RRL cell-free system cannot perform these post-translational modifications because it lacks microsomes. Typically, addition of canine pancreas microsomes is used to study events of protein translocation into and post-translational modification within the ER. Although cell-free systems from hybridoma cells and insect cells have been described that can glycosylate proteins at low efficiency (Katzen and Kudlicki 2006; Mikami et al. 2006a), there is a need to develop cell-free translation and translocation extracts from the species and tissues in which a protein is normally expressed. We demonstrate that the MEF A/A cell-free system is capable of supporting both signal sequence cleavage and N-linked glycosylation. These findings establish the MEF A/A system as a prototype for cell-free systems that can be used in industrial settings and produce proteins of medical importance.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

mRNA translation is more efficient in A/A cell-free extracts than in S/S extracts

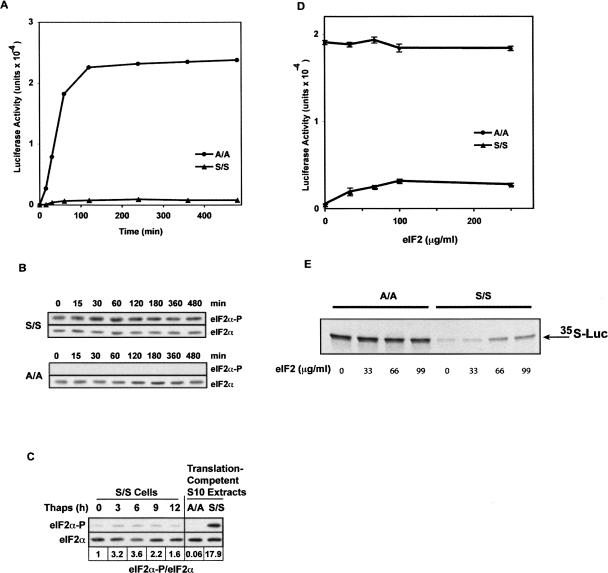

We tested the hypothesis that eIF2 phosphorylation limits translation in cell-free systems by comparing cell-free extracts from A/A MEFs, which contain an eIF2α that cannot be phosphorylated, and from wild-type (S/S) MEFs. We first examined the translation of a capped and polyadenylated reporter mRNA. In vitro reactions contained nuclease-treated S10 extract (10 mg protein/mL) and 40 μg/mL of a capped and polyadenylated mRNA that contains the firefly luciferase (LUC) open reading frame; translation was monitored by following the accumulation of LUC activity (Fig. 1A). A/A cell extracts were ∼30-fold more productive than S/S extracts, accumulating LUC activity for nearly 2 h (Fig. 1A). Moreover, LUC activity was stable during prolonged incubations, suggesting that the protein was not degraded. The observation that protein synthesis ceased after 2 h agrees with observations in all other cell-free translation systems and is probably due to the generation of inhibitory products that influence eIF2 activity. In fact, it was shown that addition of sugars delayed cessation of translation and restored linear rates of protein synthesis in RRL (Jagus and Safer 1981a).

FIGURE 1.

Protein synthesis by MEF S/S and A/A cell-free translation systems and the role of phosphorylated eIF2α. (A) Time course of protein synthesis in MEF S/S and A/A cell-free translation systems. Protein synthesis by S10 extracts was carried out under optimal conditions (as described in Materials and Methods and Table 1) using an m7G-capped, polyadenylated LUC mRNA (40 μg/mL). At the indicated times, aliquots were assayed for luciferase activity. (B,C) The levels of eIF2α and eIF2α phosphorylated on Ser51 (eIF2α-P) were assayed on Western blots using specific antibodies. (B) In vitro translation reactions lacking mRNA were incubated for the indicated times and analyzed. (C) Total cell lysates from cultured S/S cells treated with 400 nM Thaps for the indicated times and translation-competent S10 extracts from S/S and A/A cells were compared on the same gel. The ratio of band intensities is shown beneath the figure. (D,E) In vitro translation reactions containing either A/A or S/S extracts were supplemented with the indicated concentrations of eIF2 and analyzed for (D) LUC activity or (E) 35S-LUC synthesized from 35S-Met.

The low efficiency of translation in the S/S extract was probably due to the phosphorylation status of eIF2α, suggesting that functional eIF2 was limiting. To assess the phosphorylation status of eIF2α in MEF cell extracts, total eIF2α and eIF2α phosphorylated on Ser51 (eIF2α-P) were quantified on Western blots. As expected, eIF2α-P was only detected in S/S extracts, but not in A/A extracts throughout an in vitro translation reaction (Fig. 1B).

To assess the extent of eIF2α phosphorylation, we compared the eIF2α-P/eIF2α ratio in A/A and S/S cell extracts and in S/S cells treated with thapsigargin in vivo. This compound triggers the unfolded protein response in the ER, which increases eIF2α phosphorylation by activating PERK, causing a decrease in the rate of protein synthesis (Fernandez et al. 2002; Kaufman 2004). Thapsigargin treatment of S/S cells caused a transient increase in the eIF2α-P/eIF2α ratio, which peaked at 3.6-fold over control after 6 h of treatment (Fig. 1C). The eIF2α-P/eIF2α ratio in translation-competent cytoplasmic extracts from S/S cells was ∼18-fold and fivefold higher than in total extracts from untreated and stressed S/S cells, respectively. Because the elevated phosphorylation in thapsigargin-treated cells is sufficient to inhibit protein synthesis, it is likely that the very high level of phosphorylation in S/S extracts has a major inhibitory effect on translation in vitro. The increased phosphorylation of eIF2 in translation-competent extracts agrees with previous reports (Endo and Sawasaki 2006). As expected, eIF2α-P was undetectable in A/A cell extracts.

To test the hypothesis that active eIF2 is limiting in S/S cell extracts but not in A/A extracts, we supplemented the in vitro translation reactions with purified rabbit eIF2 (Benne et al. 1979). Addition of eIF2 to S/S extracts stimulated the production of LUC in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1D,E), in agreement with an earlier report (Jagus and Safer 1981b). We observed a sixfold increase in LUC activity at an eIF2 concentration of 99 μg/mL. This stimulation was not observed in A/A extracts. Even though added eIF2 stimulated translation in S/S extracts, the level remained lower than in A/A extracts. This could be due to phosphorylation of eIF2 in S/S extracts; as a consequence, each added eIF2 could only induce a single round of translation because phosphorylation would prevent recycling (Jagus and Safer 1981b). Additionally, the increase in protein synthesis reached a plateau for eIF2 amounts larger than 100 μg/mL. This is in agreement with inhibitory effects on translation by the addition of large amounts of exogenous protein (W.C. Merrick, unpubl.). As a control, addition of purified eEF1A (Merrick and Nyborg 2000) showed no apparent change in the productivity of the S/S system and a ∼20% decrease in the productivity of the A/A system (data not shown). Thus, we conclude that higher levels of active, unphosphorylated eIF2 can account for the increased productivity of the A/A system.

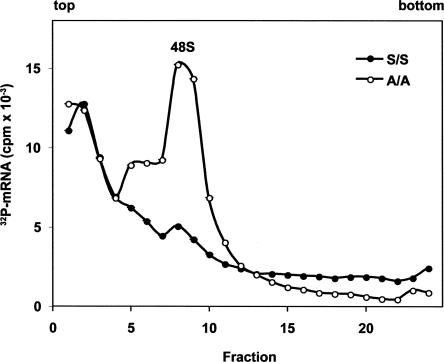

Association of a LUC mRNA with 40S and 80S ribosomes is enhanced in extracts from A/A cells

To further assess the mechanism for the increased productivity observed in the A/A extracts, we measured the formation of 48S initiation complexes that contain the 40S ribosomal subunit, mRNA, initiation factors, and Met-tRNAi Met. A 32P-labeled LUC mRNA with an m7G cap and a poly(A) tail was incubated in the S/S or A/A cell-free systems in the presence of the nonhydrolyzable GTP analog GMPPNP, which blocks translation initiation at the 48S stage (Merrick 1979). Complexes were analyzed by sedimentation on sucrose gradients. As expected, significant amounts of 32P-labeled RNA were associated with the 48S peak in the A/A extract, and barely detectable amounts were found in the S/S extract (Fig. 2). These results are consistent with our hypothesis that the lack of phosphorylated eIF2 in A/A extracts enhances the formation of 48S initiation complexes.

FIGURE 2.

Characterization by sucrose gradient centrifugation of ribosomal complexes that assembled in MEF S/S and A/A extracts. In vitro translation reactions using S10 extracts were programmed with 15 μg/mL 32P-labeled m7G-capped, polyadenylated LUC mRNA and incubated for 15 min at 37°C in the presence of 2 mM GMP-PNP. Samples were fractionated on 7%–25% sucrose gradients as described under Materials and Methods. The figure shows radioactivity (-•- S/S and -○- A/A extracts, respectively).

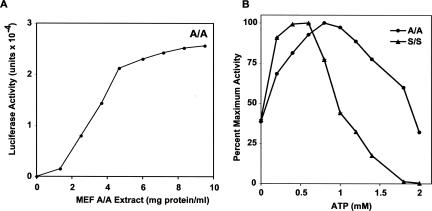

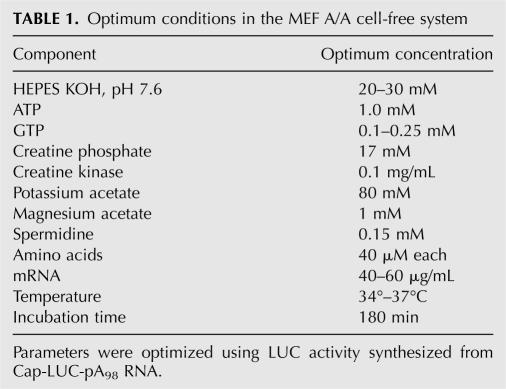

Optimum conditions in the A/A system

First we determined the optimum amount of cell extract in the A/A system. The yield of LUC activity increased rapidly up to ∼5 mg extract protein/mL and then increased more slowly at higher concentrations (Fig. 3A). We next characterized the optimum concentrations of components in the A/A system. The concentrations of ATP, Mg2+, and K+ are crucial factors that affect translational efficiency and productivity of in vitro translation (Clemens 1983); optimum concentrations in most in vitro translation systems are ∼1 mM ATP, 0.5–1.2 mM Mg2+, and 50–150 mM K+ (Clemens 1983). For the MEF extracts, we found that the maximum yield of LUC activity was obtained at ∼1 mM ATP for the A/A system and ∼0.5 mM for the S/S system (Fig. 3B). Magnesium ion at 0.8–1 mM and potassium ion at 60–80 mM gave the highest yields of LUC activity in A/A extracts (data not shown). Similar experiments were performed for all the other components of the translation reaction in A/A extracts; the optimum concentrations are listed in Table 1.

FIGURE 3.

Optimal reaction conditions for in vitro protein synthesis by S/S and A/A S10 cell extracts. Translation reactions programmed with m7G-capped, polyadenylated LUC mRNA were incubated for 4 h at 37°C and assayed for LUC activity. In each experiment, standard conditions (Table 1) were used for all the components except for MEF A/A cell extract (A) or ATP (B). In panel B LUC activity has been normalized to the maximum value for each sample. These values are 1.54 × 103 for the S/S extract and 1.66 × 104 for the A/A extract.

TABLE 1.

Optimum conditions in the MEF A/A cell-free system

mRNA translation in extracts from A/A system is enhanced by a 5′-mRNA cap and a 3′-poly(A) tail

Eukaryotic mRNA translation in vivo is dramatically enhanced by the presence of an m7G 5′-cap structure and a 3′-poly(A) tail (Imataka et al. 1998; Bergamini et al. 2000). However, the combined effects of the 5′-cap and poly(A) tail in the widely used RRL system are marginal (Michel et al. 2000). Therefore, it was of interest to check the effect of these features on mRNA utilization by the A/A extract. We prepared mRNAs with the 5′-m7G cap structure (Gcap)or ApppG (Acap) and tested their translation in the A/A MEF extracts by monitoring luciferase activity. mRNAs with or without the 3′-poly(A) tail were also tested. We found that extracts from A/A MEFs recapitulate the requirements for mammalian mRNA translation in vivo by showing highest translation efficiency for mRNAs with the Gcap and the 3′-poly(A) tail. At low mRNA concentrations, Gcap and polyadenylated mRNAs were threefold to 100-fold more efficient than an mRNA without these features, whereas the differences were less pronounced at higher mRNA concentrations (Fig. 4A,C). Moreover, there was synergy between the 5′-m7G cap and the poly(A) tail, because translation from the mRNA with both features showed a stimulation that was greater than the sum of the effects of each feature alone (Fig. 4A). These findings were confirmed by analyzing 35S-labeled LUC protein produced from the mRNAs used in Figure 4, A and C (Fig. 4B). The synergy between the 5′- and 3′-ends of the mRNA is similar to that observed in HeLa cell-free extracts (Bergamini et al. 2000). However, the A/A system was 30- to 50-fold more efficient than the HeLa system, whose activity was similar to of S/S extracts (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

The mRNA 5′ m7G cap and 3′ poly(A) tail show synergistic stimulation of translation by MEF A/A S10 extracts. (A) Time course of translation. In vitro translation assays were programmed with LUC mRNAs (20 μg/mL) with different ends and assayed for LUC activity. The mRNAs had the m7GpppG cap (Gcap) or an ApppG cap analog (Acap). The mRNAs also had a 30-residue poly(A) tail (pA30) or no tail. (B) Reactions programmed with the indicated mRNAs (20 μg/mL) were incubated for 4 h at 37°C in the presence of 35S-Met, and labeled LUC was assessed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. (C) Dependence on mRNA concentration. Reactions were programmed with the indicated mRNA concentrations, incubated for 4 h at 37°C, and assayed for LUC activity.

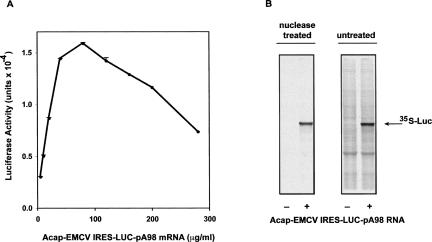

The EMCV IRES mediates efficient protein synthesis in the A/A system

We next asked whether extracts from A/A MEFs could support translation driven by the EMCV IRES. IRES-mediated translation could provide a cost-effective way of in vitro protein synthesis because the mRNA templates do not require the 5′-cap structure for efficient translation. This was assessed by studying a LUC mRNA that had the EMCV IRES in the 5′-UTR and an ApppG cap that blocks cap-dependent initiation. The mRNA with the EMCV IRES was translated efficiently, giving yields of luciferase activity that were similar to those obtained with capped and polyadenylated mRNA (cf. Figs. 5A and 4C). We next addressed if the EMCV IRES-containing mRNA was efficiently translated in extracts that were not treated with nuclease. Figure 5B shows that protein synthesis from this mRNA was equally efficient in micrococcal nuclease-treated and untreated A/A extracts. This was also observed for translation of a message with an m7G cap (see below).

FIGURE 5.

Efficient translation from the EMCV IRES by MEF A/A S10 extract. Reactions were programmed with EMCV 5′UTR-LUC-pA98 mRNA using standard conditions (Table 1) and incubated for 4 h. (A) Dependence of LUC activity expression on mRNA concentration. (B) Extracts were incubated 4 h at 37°C in the presence of 35S-Met, and the products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

We also optimized incubation conditions for EMCV IRES-mediated translation. The optimal magnesium ion concentration for the EMCV IRES was ∼1.3 mM (data not shown), which is slightly higher than for cap-dependent mRNAs. The optimal potassium ion concentration was 80 mM (data not shown), which is similar to that found for cap-dependent mRNAs. Experiments with other mRNAs revealed that optimal translation conditions show some variations (data not shown). The reasons for these differences were not investigated further.

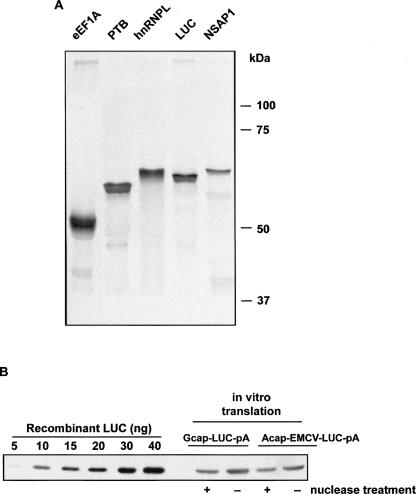

Extracts from A/A MEFs synthesize diverse proteins in large amounts

The ability to synthesize various proteins, including proteins of large size, is an important factor for the broad use of in vitro translation systems in biology. In order to test the capacity of the A/A system, we tested its ability to synthesize several proteins, including eEF1A, PTB, hnRNPL, and NSAP1, using m7G-capped, polyadenylated mRNAs. All proteins were synthesized in amounts similar to LUC (Fig. 6A), suggesting that the A/A system can be used to synthesize a wide array of proteins. The synthesis of the 163-kDa glutamyl-prolyl-tRNA synthetase (Sampath et al. 2004) was also examined. Although we observed synthesis of the full-length protein, smaller products were also observed (data not shown). Further optimization of the A/A system may be required for synthesis of large proteins.

FIGURE 6.

(A) A/A cell S10 extracts were incubated with m7GpppG-capped polyadenylated mRNAs encoding the indicated proteins in the presence of 35S-Met, and the products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. (B) To estimate the yield of LUC, A/A cell extracts prepared with or without nuclease treatment were programmed with the indicated mRNAs. Optimal magnesium acetate concentrations were used for each mRNA. The products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting along with standards of recombinant LUC.

We next quantified the yield of protein synthesized by the A/A system. LUC synthesized in vitro was detected on Western blots and quantified using standards of purified recombinant LUC (Fig. 6B). We compared the products of reactions programmed with mRNAs with a 5′-m7G cap and with the EMCV IRES. Yields from extracts that were prepared with and without nuclease treatment were also compared. These reactions synthesized 10–20 μg/mL LUC. Similar amounts of protein were obtained from mRNAs with the 5′-cap structure and the EMCV IRES. Surprisingly, ∼50% more protein was synthesized in untreated extracts than in nuclease-treated extracts. This finding is in contrast to other cell-free systems, which require nuclease treatment for efficient translation (Pelham and Jackson 1976; Clemens 1983). The reasons for efficient translation and relatively low background from endogenous mRNAs (Fig. 5B) in untreated A/A extracts are not clear. It could be due to the presence of positive factors or the absence of negative regulators whose activity depends on eIF2 phosphorylation. We also compared the yields of LUC from the A/A and RRL systems using LUC activity. The production of LUC by RRL was ∼50% that of the A/A system (data not shown). Because the RRL system contains 75–100 mg/mL of extract protein, compared to 10 mg/mL in the A/A system, the latter system is significantly more efficient when yield is normalized to the amount of extract protein. The major weakness of the RRL system is that it does not recapitulate the synergism of the 5′-cap and the 3′-poly(A) mRNA tail seen in vivo. Although capped mRNAs are efficiently translated in RRL, the poly(A) tail gives only marginal improvement to mRNA translation (Michel et al. 2000). In contrast, synergism can be achieved in other systems, but the efficiency of translation in these systems is lower than in RRL (Bergamini et al. 2000). We show here that the A/A system offers both efficient translation and synergism between the important 5′- and 3′-mRNA features.

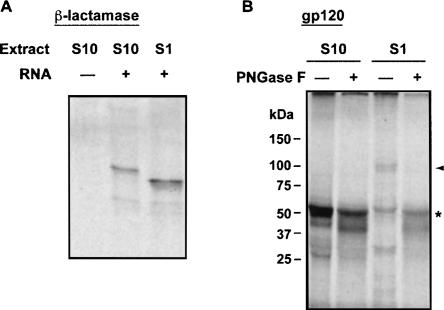

The A/A system supports post-translational modifications of secretory proteins

Approximately 30% of protein species that are translated in eukaryotic cells are translocated into the ER lumen during their synthesis (Apweiler et al. 1999; Helenius and Aebi 2004; Zhang and Kaufman 2006). These proteins undergo extensive post-translational modification, the most common being removal of the signal peptide and N-glycosylation. Currently there are only a limited number of in vitro translation systems that can carry out these modifications (Mikami et al. 2006a). Most of them are from specialized cells and are technically difficult to prepare. We therefore tested if the A/A system can support these two modifications. We compared the ability of our standard A/A extract (S10) and an S1 extract prepared by low-speed centrifugation to cleave the 23-amino-acid signal peptide from β-lactamase, a soluble protein that is secreted into the periplasmic space of Gram-negative bacteria. The S1 extract is expected to contain membranes derived from the ER. Figure 7A shows that the protein synthesized by the A/A S1 extract had faster mobility on SDS gels than the protein made in the S10 extract. Supplementing the S10 extract with canine pancreas microsomes yielded a peptide that comigrated with the S1 product (data not shown). These results suggest that the β-lactamase signal peptide was efficiently cleaved in the S1 extract (Fig. 7A).

FIGURE 7.

Post-translational modification by low-speed supernatants of MEF A/A extracts. In vitro translation reactions were supplemented with 35S-Met, and the samples were treated as indicated and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. (A) S1 and S10 extracts from MEF A/A cells were programmed with β-lactamase mRNA. The precursor (31.5 kDa) and processed protein (28.9 kDa) are seen in the second and third lanes. (B) S1 and S10 extracts were programmed with HIV gp120 mRNA, and the indicated samples were treated with PNGase F before SDS-PAGE analysis. The glycosylated (arrowhead) and unglycosylated forms (*) are noted.

Protein glycosylation was tested by studying the synthesis of the human immunodeficiency virus type-1 envelope protein 120 (gp120), which is glycosylated at multiple sites and migrates on SDS-PAGE gels at 120 kDa in its mature form. N-linked carbohydrates on the envelope HIV protein play an important role in viral replication (Balzarini 2007). S10 A/A extracts programmed with gp120 mRNA synthesized a single band that migrated at 60 kDa (Fig. 7B). When the gp120 mRNA was translated by S1 A/A extracts, a major slowly migrating form (∼100 kDa) was seen, indicating that S1 extracts contain microsomes that are capable of protein translocation into the ER and glycosylation.

To confirm that the slowly migrating gp120 species were glycosylated, samples were treated with peptide N-glycosidase F (PNGase F), which removes N-linked glycans (Fig. 7B). The mobility of the 60-kDa product from S10 extract was not affected by PNGase treatment, indicating that it is not N-glycosylated. In contrast, the mobility of slowly migrating species synthesized by S1 extracts was shifted by PNGase F treatment, so that it migrated with the S10 product, indicating that the S1 system can add N-linked glycans to translated products. Similar migration patterns for gp120 were observed by other investigators in cell-free extracts prepared from insect and hybridoma cells (Tarui et al. 2001; Mikami et al. 2006a). Our findings suggest that A/A cell extracts can perform post-translational protein modifications. It is expected that the development of A/A systems from secretory cells can further enhance the efficiency of post-translational modifications.

In conclusion, we have developed a novel cell-free translation system for the synthesis and post-translational modification of proteins. In contrast to other systems, such as HeLa extracts, the A/A system can efficiently translate exogenous mRNAs in the presence of endogenous messages. Similar to other systems, such as the ones from Drosophila and HeLa cells, the A/A system shows synergism between the 5′-cap and 3′-poly(A) tail. Even though A/A cells are not highly active secretory cells, the ability of A/A extracts to carry out post-translational processing speaks for the potential of this system in the synthesis of secretory proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids

pPQ-LUC-pA30 (Wang and Sachs 1997) and pT3-LUC-pA98 (Bergamini et al. 2000) plasmids were kindly provided by Matthew Sachs (Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR) and Matthias Hentze (EMBL, Heidelberg, Germany), respectively. pET-19b-hnRNPL, pET19b-PTB, and pTandem1-hnNASAP plasmids were kindly provided by Tom Cooper (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX) and Paul Fox (Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH). pTM-DHgp120H encoding the HIV gp120 under the control of the T7 promoter (Lee et al. 2000) was provided by Michael Cho (Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH). The pT3-EMCV 5′UTR-LUC-p(A)98 plasmid bearing the EMCV IRES fused to firefly luciferase was constructed as follows: the EMCV IRES (corresponding to nucleotides 265–828 of genomic RNA) was amplified by PCR from an EMCV IRES-containing plasmid (Drew and Belsham 1994), using 5′-ACGCGTCGACCCCCCTAACGTTACTGGCCG-3′ as upstream and 5′- CATGCCATGGATCGTGTTTTTCAAAGGAAAACCACGT-3′ as downstream primers. The PCR fragment was digested with XbaI and SalI and inserted into pT3-LUC-pA98 digested with same enzymes. The nucleotide sequence of the plasmid was verified by DNA sequencing.

mRNA preparation

mRNA transcripts were produced in vitro using bacteriophage T3 or T7 RNA polymerases and the Ambion Megascript kit in the presence of either m7GpppG or ApppG cap analogs (NEB) as described by the manufacturer. To produce polyadenylated mRNAs, plasmids were linearized with either EcoRI (pPQ-LUC-A30) or NotI (pT3-LUC-A98 and pT3-EMCV-LUC-A98). Non-polyadenylated capped and uncapped luciferase mRNAs were produced from the pPQ-LUC-A30 vector linearized with XbaI. Capped mRNAs for mouse eEF1A, human hnRNPI/PTB, human hnRNPL, and human NASAP1 were transcribed from the corresponding plasmids after digestion with XhoI, DraIII, DraIII, and NheI, respectively. The gp120 mRNA was produced using pTM-DHgp120H plasmid linearized with XhoI. Typical in vitro transcription reactions, were carried out for 2.5 h at 37°C. After DNase I treatment, the transcripts were purified by phenol/chloroform extraction and LiCl precipitation, and quantified using UV spectroscopy. Integrity of the mRNAs was confirmed by denaturing gel electrophoresis in 1.5% formaldehyde-agarose gels.

Preparation of S1 and S10 extracts from mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs)

Previously described mouse embryo fibroblast (MEF) cell lines (Scheuner et al. 2001) [wild-type (S/S) and the mutant (A/A) with the Ser51Ala mutation in eIF2α] were cultured in Dulbecco's modified essential medium with high glucose (Invitrogen) with the addition of 10% fetal bovine serum [Invitrogen (Gibco BRL)], 2 mM glutamine, penicillin/streptomycin, and essential and nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen). Cells were grown on plates (12 × 150 mm) to 90% confluency, and the culture medium was removed. Cells were washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), harvested by scraping into 10–20 mL of PBS containing 11 mM glucose (PBS-glucose), and collected by centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C.

To prepare S10 extract, the cell pellet was washed twice with PBS-glucose and suspended in an equal volume of ice-cold hypotonic extraction buffer, containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 10 mM potassium acetate, 1 mM magnesium acetate, 4 mM dithiothreitol, and Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (EDTA-free; Roche). After 5 min on ice, cells were transferred to a Dounce homogenizer and broken with 20–25 strokes. The homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000g for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was collected with a sterile pipette, avoiding both the pellet and the fatty upper layer, divided into aliquots, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. The final protein concentration of the extract was typically 18–20 mg/mL.

To prepare the S1 extract, the MEF cell pellet (after the PBS wash step) was suspended in an equal volume of ice-cold 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 100 mM potassium acetate, 1 mM magnesium acetate, 2 mM dithiothreitol, and 100 μg/mL lysolecithin (L-α-lysophosphatidylcholine; Sigma-Aldrich). After 1 min on ice, the cells were pelleted (10 sec, 10,000g), and the supernatant was quickly removed. The pellet was suspended in an equal volume of ice-cold hypotonic extraction buffer. After 5 min on ice, the cells were disrupted by passing 10 times through a 26-gauge needle attached to a 1-mL syringe. The cell homogenate was centrifuged at 1000g for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected, and aliquots were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Where indicated, extracts were treated with micrococcal nuclease (0.01 U/μL; Sigma-Aldrich) in the presence of 1 mM CaCl2 for 8 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by addition of EGTA to a final concentration of 2 mM. The mixture was kept on ice for 5 min, and the supernatant was used for in vitro translation.

Cell-free protein synthesis

In vitro translation reactions using MEF cell extracts were typically performed in reaction volumes of 12 μL. Standard reaction conditions were as follows, unless otherwise indicated: MEF extract (final protein concentration 9–10 mg/mL), 40 μg/mL mRNA, 20 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.6), 80 mM potassium acetate, 1 mM magnesium acetate, 1 mM ATP, 0.12 mM GTP, 17 mM creatine phosphate, 0.1 mg/mL creatine phosphokinase (Sigma-Aldrich), 2 mM dithiothreitol, 40 μM of each of the 20 amino acids, 0.15 mM spermidine, and 400 U/mL RNAsin (Promega). Incubations were carried out for 3 h at 37°C, unless otherwise indicated. Translations in a nuclease-treated rabbit reticulocyte lysate (RRL) system (Promega) were carried out according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Signal sequence processing and N-linked glycosylation

Escherichia coli β-lactamase and HIV gp120 proteins were synthesized under optimal reaction conditions using S1 or S10 MEF extracts in the presence of 1.2 μCi of 35S-methionine (1200 Ci/mmol; GE Healthcare) for 3 h at 37°C. Where indicated, MEF S10 reactions were supplemented with 1 μL of Canine Pancreatic Microsomal Membranes (Promega). In deglycosylation experiments, samples of cell-free translation reactions (5 μL) were treated with PNGase F (NEB) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Samples were analyzed on SDS gels.

Luciferase assay

The Luciferase Assay System with Reporter Lysis Buffer (Promega) was used. Aliquots (1–2 μL) of the translation reactions were diluted in 50 μL of Passive Lysis Buffer and mixed with 50 μL of the standard luciferase assay reagent in 96-well assay plates, and the luminescence was measured for 5 sec in a Turner Designs Model 20/20 luminometer. Luciferase activity is expressed as counts per microliter.

SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis and autoradiography

SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis was performed according to Laemmli (1970). To label the translation products, the translation reactions (12 μL) were supplemented with 1.2 μCi of 35S-methionine. Typically, 5 μL of the reaction mixture was resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE gels, and the radiolabeled translation products were visualized by autoradiography.

Sedimentation analysis of ribosomal complexes

This was performed essentially as described previously (Komar et al. 2005). 32P-labeled mRNA was produced in transcription reactions containing [α-32P]UTP (800 Ci/mmol; MP Biomedicals). Transcripts were purified using NucAway Spin columns (Ambion). In vitro translation reactions (70 μL) containing 1 μg of 32P-labeled mRNA (3 × 106 cpm/μg) were incubated for 15 min at 37°C in the presence of 2 mM GMP-PNP and then layered over 7%–25% sucrose gradients containing 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 20 mM HEPES•KOH (pH 7.4), and 2 mM dithiothreitol, and centrifuged in a Beckman SW32.1 rotor for 19 h at 20,000 rpm at 4°C. Gradients were collected using the ISCO Programmable Density Gradient System with continuous monitoring of absorbance at 254 nm. The radioactivity of gradient fractions was determined by Cerenkov counting.

Western blot analysis

Western blotting was performed following standard procedures (Towbin et al. 1979). Anti-eIF2α and anti-phospho(Ser-51)-eIF2α antibodies were obtained from BioSource International/Invitrogen and Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., respectively. Antibodies against firefly luciferase were from Promega. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.. Typically, 4 μL aliquots from the translation reactions were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE gel, and proteins were transferred to Hybond-P membranes (GE Healthcare). HRP was detected with a SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate Kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc.). Films were scanned, and band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants DK060596 and RO1-DK053307 (to M.H.) and DK042394 and HL052173 (to R.J.K.) from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.825008.

REFERENCES

- Apweiler, R., Hermjakob, H., Sharon, N. On the frequency of protein glycosylation, as deduced from analysis of the SWISS-PROT database. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1473:4–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(99)00165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzarini, J. Targeting the glycans of glycoproteins: A novel paradigm for antiviral therapy. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007;5:583–597. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benne, R., Brown-Luedi, M.L., Hershey, J.W. Protein synthesis initiation factors from rabbit reticulocytes: Purification, characterization, and radiochemical labeling. Methods Enzymol. 1979;60:15–35. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(79)60005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergamini, G., Preiss, T., Hentze, M.W. Picornavirus IRESes and the poly(A) tail jointly promote cap-independent translation in a mammalian cell-free system. RNA. 2000;6:1781–1790. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200001679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens, M.J. Translation of eukaryotic messenger RNA in cell-free extracts. In: Hames B.D., Higgins S.J., editors. Transcription and translation: A practical approach. IRL Press; Oxford, UK: 1983. pp. 231–270. [Google Scholar]

- Drew, J., Belsham, G.J. trans complementation by RNA of defective foot-and-mouth disease virus internal ribosome entry site elements. J. Virol. 1994;68:697–703. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.2.697-703.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo, Y., Sawasaki, T. Cell-free expression systems for eukaryotic protein production. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2006;17:373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, J.M., Yaman, I., Sarnow, P., Snider, M.D., Hatzoglou, M. Regulation of internal ribosomal entry site-mediated translation by phosphorylation of the translation initiation factor eIF2α. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:19198–19205. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201052200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallie, D.R. The cap and poly(A) tail function synergistically to regulate mRNA translational efficiency. Genes & Dev. 1991;5:2108–2116. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.11.2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helenius, A., Aebi, M. Roles of N-linked glycans in the endoplasmic reticulum. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2004;73:1019–1049. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershey, J., Merrick, W. The pathway and mechanism of initiation of protein synthesis. In: Sonenberg N., et al., editors. Translational control of gene expression. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 2000. pp. 33–88. [Google Scholar]

- Imataka, H., Gradi, A., Sonenberg, N. A newly identified N-terminal amino acid sequence of human eIF4G binds poly(A)-binding protein and functions in poly(A)-dependent translation. EMBO J. 1998;17:7480–7489. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.24.7480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagus, R., Safer, B. Activity of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 is modified by processes distinct from phosphorylation. I. Activities of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 and eukaryotic initiation factor 2 α kinase in lysate gel filtered under different conditions. J. Biol. Chem. 1981a;256:1317–1323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagus, R., Safer, B. Activity of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 is modified by processes distinct from phosphorylation. II. Activity of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 in lysate is modified by oxidation-reduction state of its sulfhydryl groups. J. Biol. Chem. 1981b;256:1324–1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzen, F., Kudlicki, W. Efficient generation of insect-based cell-free translation extracts active in glycosylation and signal sequence processing. J. Biotechnol. 2006;125:194–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, R.J. Regulation of mRNA translation by protein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2004;29:152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komar, A.A., Gross, S.R., Barth-Baus, D., Strachan, R., Hensold, J.O., Goss Kinzy, T., Merrick, W.C. Novel characteristics of the biological properties of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae eukaryotic initiation factor 2A. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:15601–15611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413728200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.K., Martin, M.A., Cho, M.W. Higher Western blot immunoreactivity of glycoprotein 120 from R5 HIV type 1 isolates compared with X4 and X4R5 isolates. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 2000;16:765–775. doi: 10.1089/088922200308765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrick, W.C. Evidence that a single GTP is used in the formation of 80 S initiation complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 1979;254:3708–3711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrick, W., Nyborg, J. The protein biosynthesis elongation cycle. In: Sonenberg N., et al., editors. Translational control of gene expression. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 2000. pp. 89–126. [Google Scholar]

- Michel, Y.M., Poncet, D., Piron, M., Kean, K.M., Borman, A.M. Cap-poly(A) synergy in mammalian cell-free extracts. Investigation of the requirements for poly(A)-mediated stimulation of translation initiation. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:32268–32276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004304200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikami, S., Kobayashi, T., Yokoyama, S., Imataka, H. A hybridoma-based in vitro translation system that efficiently synthesizes glycoproteins. J. Biotechnol. 2006a;127:65–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikami, S., Masutani, M., Sonenberg, N., Yokoyama, S., Imataka, H. An efficient mammalian cell-free translation system supplemented with translation factors. Protein Expr. Purif. 2006b;46:348–357. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munroe, D., Jacobson, A. mRNA poly(A) tail, a 3′ enhancer of translational initiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1990;10:3441–3455. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.7.3441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonato, M.C., Widom, J., Clardy, J. Crystal structure of the N-terminal segment of human eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:17057–17061. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111804200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham, H.R., Jackson, R.J. An efficient mRNA-dependent translation system from reticulocyte lysates. Eur. J. Biochem. 1976;67:247–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1976.tb10656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaiah, K.V., Davies, M.V., Chen, J.J., Kaufman, R.J. Expression of mutant eukaryotic initiation factor 2 α subunit (eIF-2 α) reduces inhibition of guanine nucleotide exchange activity of eIF-2B mediated by eIF-2 α phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;14:4546–4553. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.7.4546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramelot, T.A., Cort, J.R., Yee, A.A., Liu, F., Goshe, M.B., Edwards, A.M., Smith, R.D., Arrowsmith, C.H., Dever, T.E., Kennedy, M.A. Myxoma virus immunomodulatory protein M156R is a structural mimic of eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF2α. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;322:943–954. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00858-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ron, D., Harding, H.P. eIF2a in cellular stress responses and disease. In: Mathews M.B., et al., editors. Translational control in biology and medicine. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 2007. pp. 345–368. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, A.B., Sarnow, P., Hentze, M.W. Starting at the beginning, middle, and end: Translation initiation in eukaryotes. Cell. 1997;89:831–838. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampath, P., Mazumder, B., Seshadri, V., Gerber, C.A., Chavatte, L., Kinter, M., Ting, S.M., Dignam, J.D., Kim, S., Driscoll, D.M., et al. Noncanonical function of glutamyl-prolyl-tRNA synthetase: Gene-specific silencing of translation. Cell. 2004;119:195–208. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuner, D., Song, B., McEwen, E., Liu, C., Laybutt, R., Gillespie, P., Saunders, T., Bonner-Weir, S., Kaufman, R.J. Translational control is required for the unfolded protein response and in vivo glucose homeostasis. Mol. Cell. 2001;7:1165–1176. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00265-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spirin, A.S. High-throughput cell-free systems for synthesis of functionally active proteins. Trends Biotechnol. 2004;22:538–545. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudhakar, A., Ramachandran, A., Ghosh, S., Hasnain, S.E., Kaufman, R.J., Ramaiah, K.V. Phosphorylation of serine 51 in initiation factor 2 α (eIF2 α) promotes complex formation between eIF2 α(P) and eIF2B and causes inhibition in the guanine nucleotide exchange activity of eIF2B. Biochemistry. 2000;39:12929–12938. doi: 10.1021/bi0008682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svitkin, Y.V., Ovchinnikov, L.P., Dreyfuss, G., Sonenberg, N. General RNA binding proteins render translation cap dependent. EMBO J. 1996;15:7147–7155. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svitkin, Y.V., Imataka, H., Khaleghpour, K., Kahvejian, A., Liebig, H.D., Sonenberg, N. Poly(A)-binding protein interaction with elF4G stimulates picornavirus IRES-dependent translation. RNA. 2001;7:1743–1752. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarui, H., Murata, M., Tani, I., Imanishi, S., Nishikawa, S., Hara, T. Establishment and characterization of cell-free translation/glycosylation in insect cell (Spodoptera frugiperda 21) extract prepared with high pressure treatment. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001;55:446–453. doi: 10.1007/s002530000534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin, H., Staehelin, T., Gordon, J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: Procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z., Sachs, M.S. Arginine-specific regulation mediated by the Neurospora crassa arg-2 upstream open reading frame in a homologous, cell-free in vitro translation system. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:255–261. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.1.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wek, R.C., Jiang, H.Y., Anthony, T.G. Coping with stress: eIF2 kinases and translational control. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2006;34:7–11. doi: 10.1042/BST20060007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K., Kaufman, R.J. Protein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum and the unfolded protein response. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2006;172:69–91. doi: 10.1007/3-540-29717-0_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]