Abstract

Skeletal muscle is composed of muscle fibers and an extracellular matrix (ECM). The collagen fiber network of the ECM is a major contributor to the passive force of skeletal muscles at high strain. We investigated the effect of aging on the biomechanical and structural properties of epimysium of the tibialis anterior muscles (TBA) of rats to understand the mechanisms responsible for the age-related changes. The biomechanical properties were tested directly in vitro by uniaxial extension of epimysium. The presence of age-related changes in the arrangement and size of the collagen fibrils in the epimysium was examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). A mathematical model was subsequently developed based on the structure-function relationships that predicted the compliance of the epimysium. Biomechanically the epimysium from old rats was much stiffer than that of the young rats. No differences were found in the ultrastructure and thickness of the epimysium or size of the collagen fibrils between young and old rats. The changes in the arrangement and size of the collagen fibrils do not appear to be the principal cause of the increased stiffness of the epimysium from the old rats. Other changes in the structural composition of the epimysium from old rats likely has a strong effect on the increased stiffness. The age-related increase in the stiffness of the epimysium could play an important role in the impaired lateral force transmission in the muscles of the elderly.

Keywords: scanning electron microscopy (SEM), collagen fibrils, epimysium, mechanical properties, mathematical modeling, tibialis anterior muscle (TBA)

Introduction

Skeletal muscle is composed of muscle fibers and an extracellular matrix (ECM). The overall mechanical properties of the entire skeletal muscle are determined by the properties of muscle fibers, the surrounding ECM and the interactions between these two components (Purslow 2002). Despite the lack of direct measurements, many indirect observations support the premise that the ECM is an essential element for the lateral transmission of force during skeletal muscle contractions, when tension is transmitted within the intramuscular connective tissues laterally to the epimysium and then to the tendon (Bloch and Gonzalez-Serratos 2003).

McMahon (1984) has suggested that the passive mechanical properties depend on the collagen content. Both the intermolecular cross-links of the collagen and the arrangement and the size of the collagen fibers play an important role in the determination of biomechanical properties of the ECM (Rowe, 1981; Kjaer et al., 2006). The aging process may increase stiffness of the connective tissues and change physical and biological characteristics of the collagens (Galeski et al. 1977; Kjaer et al., 2004) by increasing the amount of cross-linking between and within the collagen fibrils (Rodrigues et al. 1996). The purpose of the present study was to investigate the mechanisms responsible for the age-related changes in the biomechanical properties of ECM. Based on the experimental data, a mathematical model was developed that predicted the compliance of the ECM in skeletal muscle.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Two groups of male Lewis rats were used in the experiments: young (n=7; 4 months of age) and old (n=11; 28−30 months of age). Animal housing, operations and subsequent animal care were carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Unit for the Laboratory Animal Medicine at the University of Michigan.

Scanning Electron Microscopy

For three young rats and five old rats, a small section of the epimysium was dissected from TBA muscles, fixed, processed (Provenzano and Vanderby, 2006) and viewed on an Amray 1910 FE field emission scanning electron microscope.

Measurement of the Mechanics of Epimysium in vitro

Each end of a sample was attached to small flat piece of the plastic holders with cyanoacrylate glue (Vetbond tissue adhesive, St. Paul, MN). The specimen was mounted horizontally in chamber between the servomotor lever arm and a steel hook attached to a force transducer (Lynch et al. 2001).

The initial length of the sample (L0) was adjusted before stretching (Viidik 1979). The velocity of the stretch was 10mm/s. The ratio between the current length (L) and the initial length (L0) was defined as the ‘stretch ratio’ λ (λ = L/L0).

Mathematical Modeling

The work presented is based on the potential energy model for isotropic materials proposed by Veronda and Westmann (1970). A function α(λ) was introduced to simulate the effect of the breakage of the cross-linking between the collagen fibers. Then we have

where

and A <0. λcr is the critical stretch ratio, and defined as the end point of the linear region. We called this model a modified V-W model.

Statistical Analysis

To determine the size of the collagen fibers and the thickness of the epimysiums, images were obtained by SEM and analyzed by Image J software (Abramoff et al. 2004). Thickness of the epimysiums was measured in ten different locations. Differences were considered significant when t≤0.05. The values R2 and r2 were calculated to quantify the goodness of fit of mathematical modeling (Barclay 1991). R2 indicated the proportion of total variation that was explained by the model; r2 was the squared correction between the data observed during experiment and the data predicted by the model.

Results

Measurement of the epimysium mechanics

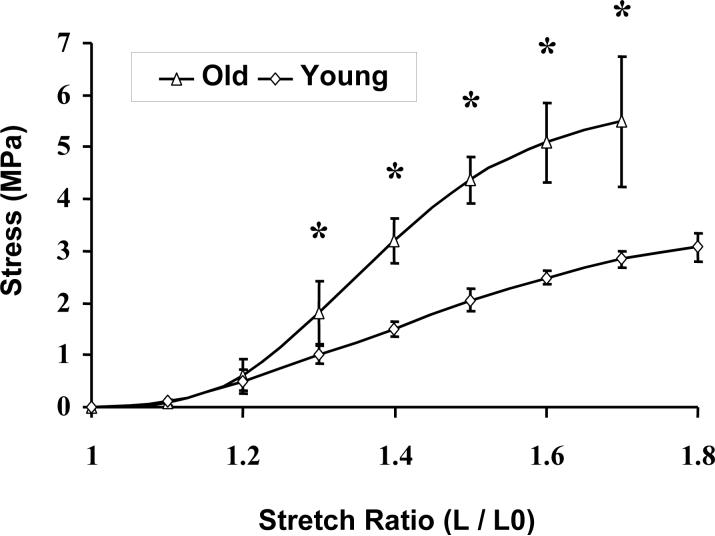

As for many other soft tissues, the stress-strain relationships for the epimysiums of the skeletal muscles from both the young and old rats were nonlinear (Figure 1). Four separate regions could be identified: low-modulus toe region, linear region, post yield region, and ‘failure’ region. For the epimysiums from skeletal muscles of both young and old rats, no difference was observed for the low-modulus toe region with a value of 0 <λ<1.2. In contrast, for the linear region, the value for the ‘old’ epimysium region was λ∊(1.2,1.4), while that for the ‘young’ epimysium region was λ∊(1.2,1.5). In this region the stiffness of the epimysium of old rats (MPa) was increased by 98% when compared with that of young rats. For the post yield region the values for the ultimate strain of the epimysium of old rats were lower by about 12%, while the ultimate stress was approximately two times higher (Figure 1), when compared with that of the young rats.

Figure 1.

The stress-strain relationship of the epimysium. The stress is engineering stress, which is the force per original area. MPa = Newton/mm2. Strain is expressed as stretch ratio, which is λ = L/L0. Mean values with SEM are presented. Old: epimysium from 28-moth-old rats, n = 11. Young: epimysium from 4-moth-old rats, n = 7. * indicates p≤0.05. The data measured beyond the maximal stretch ratio were unstable and are not reported here.

Ultrastructure of the epimysium

Arrangement of the collagen fibers

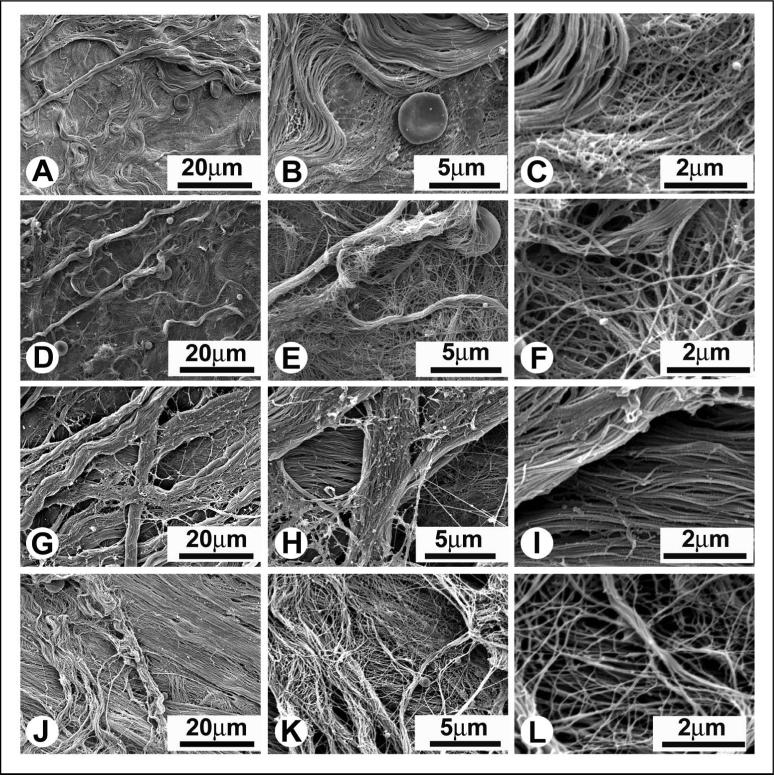

The structural appearances of the inner and outer surfaces of the epimysium differed from one another (Figures 2A, 2D and 2G, 2J). Regardless of the age of rats, the differences in appearance and arrangement of collagen fibrils at the inner and outer surfaces were highly reproducible. When comparing the epimysiums obtained from young (Figures 2A-C and 2G-I) and old (Figures 2D-F and 2J-L) rats, no differences were detected in the arrangement of the collagen fibrils.

Figure 2.

The representative SEM micrographs of the inner (Figures A-F) and outer (Figures G-L) surfaces of the epimysium of TBA muscles of young (Figures A-C and G-E) and old (Figures D-F and J-L) rats. Note differences in the structural appearance of the inner and outer surfaces of the epimysium. Coarse sheets of collagen made from large fibril bundles were located on the inner (facing the muscle) and outer (facing epimysium of the adjacent muscle) planes of the epimysium, while the middle portion of the epimysium consisted of finer sheets of collagen. At the inner surface wavy bundles of collagen fibrils were randomly oriented in multiple directions (Figures A-F). At the outer surface bundles of collagen fibrils were aligned in parallel with one another and displayed a noticeable dominant direction (Figures G-L).

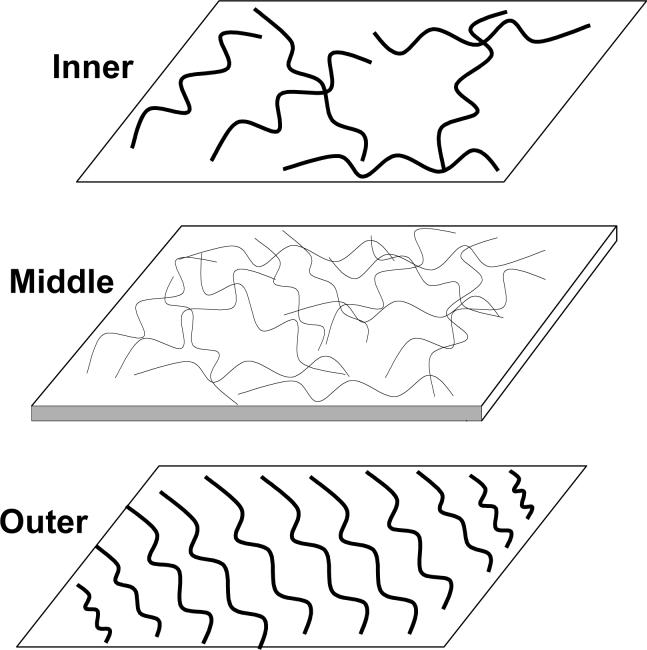

To describe the gradation from the coarse external collagen sheets down to a very delicate middle one, a schematic figure of the epimysium structure was developed in Figure 3. The thickness of the epimysium varied: from 20.1 to 34.4 μm for the young rats and from 19.6 to 40.1 μm for the old rats. This variation resulted from the high degree of variation in the thickness of the epimysium along the length of individual samples. As a result, even the epimysium samples taken from the adjacent regions of the muscle showed some variations in thickness. No significant differences (t = 0.59) were observed in the thickness of the epimysiums from old (29.7±8.6 μm) compared with young (34.6±14.6 μm) rats.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the ultrastructure of the epimysium in rat TBA muscle. The top graph is the inner layer composed of randomly distributed coarse fibril bundles, and the bottom graph is the outer layer composed of fibril bundles with highly noticeable dominant fiber direction. On the surfaces of either inner or outer layers individual collagen fibril are arranged in tightly packed bundles. Located between the inner and the outer layers middle collagen layer consists of several sheets of very fine intertwined collagen fibrils. In the middle collagen layer individual collagen fibrils can be easily identified. The wavy pattern was observed for all collagen fibrils that were studied.

For each sample, the collagen fibrils located in the coarse outer layers had larger diameters than those located on the finer inner layer of the epimysium (Table 1). The thicknesses of collagen fibrils from young and old rats were not different.

Table 1.

Diameters of the individual collagen fibrils in the epimysium of tibialis anterior muscles from young and old rats.

| Age |

Inner Side |

Outer Side |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Layer1 | Layer2 | Layer1 | Layer2 | |

|

Young |

49.02 ± 3.76 |

29.76 ± 6.67 |

48.98 ± 1.04 |

40.75 ± 2.37 |

|

Old |

51.53 ± 0.81 |

36.89 ± 4.46 |

60.82 ± 8.82 |

43.53 ± 6.72 |

| T-Test | 0.32 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.54 |

Unit size: nm. Data are expressed as Value ± SD.

For the epimysiums from each of the rats, diameters of twenty collagen fibrils were measured. In total, for the old rats, n = 100, and for the young rats, n = 60.

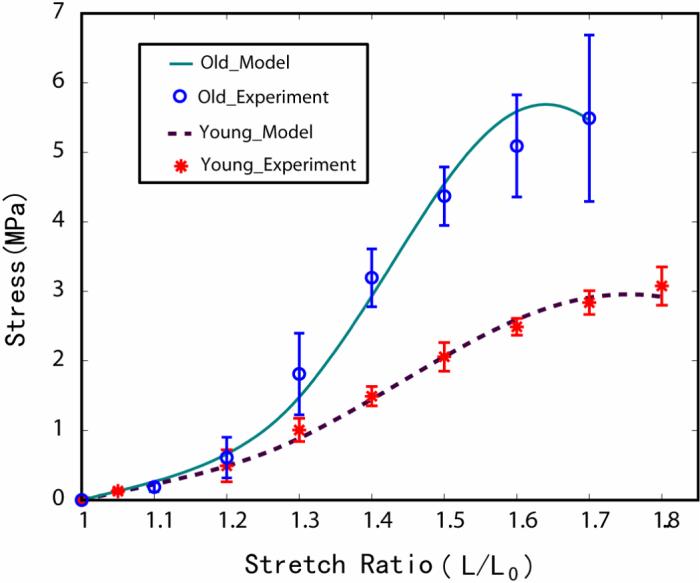

Mathematical modeling

Figure 4 shows the comparison between the experimental data and the mathematical expression. The statistical analysis showed that for the epimysium of young rats the values are R2 = 0.9994 and r2 = 0.997. The analysis implies that 99% of the data observed from the experiment is predicted by the model developed. The data for analyzing the goodness of fit using R-square and r-square are R2 = 0.9986 and r2 = 0.9941.

Figure 4.

The comparison between the experimental data and the mathematical expression. The stress is the engineering stress, which is the force per original area. Strain is expressed as stretch ratio, which is λ = L/L0. The experimental data were plotted as mean ± SD. The data from the modified V-W model with the uniaxial stresses calculated for the epimysium of young and old rats were plotted as solid lines. For both young and old rats, the solid lines were within the envelope of the experimental data. At the lower stretch ratio region, the experimental data and the data predicted by the modified V-W model closely coincided.

Discussion

The main goal of the study was to compare functional/structural differences in the epimysium from young and old rats. As reported for other soft tissues (Viidik 1979; Woo et al. 1993; Wagner et al., 2006), the measurements of tensile properties of the epimysium in the current study showed that the stress-strain relationship is nonlinear. At low strains, elastin and ground substance are the main contributors of the tensile strength of epimysium (Viidik 1979). At high strains, collagen fibers assume a straight configuration and become the main contributors to the tensile strength (Belkoff and Haut 1991).

The shape of stress-strain curve of the epimysium observed in the present study is very similar to that reported previously for the endomysium (Purslow and Trotter 1994). Purslow and Duance (1990) reported that at high extension, the collagen fibers in the endomysium make a significant contribution to the passive properties of the individual muscle fibers. Our experiments showed no differences for the low-modulus toe region. In contrast, for the linear region, the epimysium from old rats was stiffer than that from young rats. The collagen fibers are likely the main contributors of the increased stiffness of the epimysium in the linear region.

The mathematical model presented here successfully predicts the response of epimysiums to uniaxial extension. The response is due mainly to the substantial effect that collagen network has on any large deformation response of the epimysium. The stress-strain relationship illustrates the exponential stiffening character of epimysium from old rats followed by the weakening of the material. Based on our SEM observations, the age-related increase in the stiffness of the epimysium does not likely result from the differences in the arrangement and/or sizes of the collagen fibrils. Similarly Lavagnino and colleagues (2005) reported differences in ultimate tensile strength between control and stress-deprived tendons, but found no difference in the number, mean diameter, mean density, or size of collagen fibrils. Most probably increased stiffness of epimysium is associated with an increase in the amount of collagen cross-linking (Rodrigues et al. 1996) and the age-related reduction in solubility and turnover of collagen (Kjaer et al., 2004). The increased stiffness of epimysium may also be a result of the qualitative changes in the structure of collagen fibrils (Bruel and Oxlund 1996), as well as with age-related changes in elastins and proteoglycans.

In conclusion, we report here for the first time age-related stiffening of the epimysium in rats. In the elderly, stiffening of the epimysium could have a substantial effect on the impairment in force generated by the contracting muscle fibers, transmitted laterally to the epimysium and eventually to the muscle tendon (Grounds et al., 2005).

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Dorothy Sorenson from the University of Michigan Microscopy Imaging Laboratory for help with SEM and Ms. Cheryl Hassett for her assistance in animal care. The study was supported by NIA grant PO1-AG20591 (JAF), the Nathan Shock Center Contractility Core [NIA grant P30-AG13283 (JAF)] and by Nathan Shock Center Pilot Grant Award to T. Kostrominova.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abramoff MD, Magelhaes PJ, Ram SJ. Image Processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics International. 2004;11(7):36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Barclay DL. A statistical note on trend factors: the meaning of “R-squared”. Fall 1991 Edition Casualty Actuarial Society Forum.; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Belkoff SM, Haut RC. A structural model used to evaluate the changing microstructure of maturing rat skin. Journal of Biomechanics. 1991;24(8):711–720. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(91)90335-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch RJ, Gonzalez-Serratos H. Lateral force transmission across costameres in skeletal muscle. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews. 2003;31(2):73–78. doi: 10.1097/00003677-200304000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruel A, Oxlund H. Changes in biomechanical properties, composition of collagen and elastin, and advanced glycation endproducts of the rat aorta in relation to age. Atherosclerosis. 1996;127(2):155–165. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(96)05947-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galeski A, Kastelic J, Baer E, Kohn RR. Mechanical and structural changes in rat tail tendon induced by alloxan diabetes and aging. Journal of Biomechanics. 1977;10(1112):775–782. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(77)90091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grounds MD, Sorokin L, White J. Strength at the extracellular matrix-muscle interface. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports. 2005;15:381–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2005.00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjaer M, Magnusson P, Krogsgaard M, Boysen MJ, Olesen J, Heinemeier K, Hansen M, Haraldsson B, Koskinen S, Esmarck B, Langberg H. Extracellular matrix adaptation of tendon and skeletal muscle to exercise. Journal of Anatomy. 2006;208(4):445–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00549.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjaer M. Role of extracellular matrix in adaptation of tendon and skeletal muscle to mechanical loading. Physiological Reviews. 2004;84(2):649–698. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00031.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavagnino M, Arnoczky SP, Frank K, Tian T. Collagen fibril diameter distribution does not reflect changes in the mechanical properties of in vitro stress-deprived tendons. Journal of Biomechanics. 2005;38(1):69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch GS, Hinkle RT, Chamberlain JS, Brooks SV, Faulkner JA. Force and power output of fast and slow skeletal muscles from mdx mice 6−28 months old. The Journal of Physiology. 2001;535(Pt 2):591–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00591.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon TA. Muscles, reflexes, and locomotion. Princeton University Press; Princeton, N.J.: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Provenzano PP, Vanderby R., Jr. Collagen fibril morphology and organization: implications for force transmission in ligament and tendon. Matrix Biology. 2006;25(2):71–84. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purslow PP. The structure and functional significance of variations in the connective tissue within muscle. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology - Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 2002;133(4):947–966. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(02)00141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purslow PP, Duance VC. Structure and function of intramuscular connective tissue. In: Hukins DWL, editor. Connective Tissue Matrix. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 1990. pp. 127–166. [Google Scholar]

- Purslow PP, Trotter JA. The morphology and mechanical properties of endomysium in series-fibred muscles: variations with muscle length. Journal of Muscle Research and Cell Motility. 1994;15(3):299–308. doi: 10.1007/BF00123482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues CJ, A. J, R. J, Bohm GM. Effects of aging on muscle fibers and collagen content of the diaphragm: a comparison with the rectus abdominis muscle. Gerontology. 1996;42(4):18–28. doi: 10.1159/000213796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe RW. Morphology of perimysial and endomysial connective tissue in skeletal muscle. Tissue and Cell. 1981;13(4):681–690. doi: 10.1016/s0040-8166(81)80005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veronda DR, Westmann RA. Mechanical characterization of skin-finite deformations. Journal of Biomechanics. 1970;3(1):111–124. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(70)90055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viidik A. Biomechanical behavior of soft connective tissues. Progress in biomechanics. 1979:75–113. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner DR, Reiser KM, Lotz JC. Glycation increases human annulus fibrosus stiffness in both experimental measurements and theoretical predictions. Journal of Biomechanics. 2006;39(6):1021–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo SL, Johnson GA, Smith BA. Mathematical modeling of ligaments and tendons. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 1993;115(4B):468–473. doi: 10.1115/1.2895526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]