Abstract

The Mre11 complex functions in double-strand break (DSB) repair, meiotic recombination, and DNA damage checkpoint pathways. Sae2 deficiency has opposing effects on the Mre11 complex. On one hand, it appears to impair Mre11 nuclease function in DNA repair and meiotic DSB processing, and on the other, Sae2 deficiency activates Mre11-complex-dependent DNA-damage-signaling via the Tel1–Mre11 complex (TM) pathway. We demonstrate that SAE2 overexpression blocks the TM pathway, suggesting that Sae2 antagonizes Mre11-complex checkpoint functions. To understand how Sae2 regulates the Mre11 complex, we screened for sae2 alleles that behaved as the null with respect to Mre11-complex checkpoint functions, but left nuclease function intact. Phenotypic characterization of these sae2 alleles suggests that Sae2 functions as a multimer and influences the substrate specificity of the Mre11 nuclease. We show that Sae2 oligomerizes independently of DNA damage and that oligomerization is required for its regulatory influence on the Mre11 nuclease and checkpoint functions.

THE DNA damage response is a highly conserved process that prevents genome instability. In budding yeast, checkpoint signaling is initiated by the yeast ataxia-telangiectasia mutated/ataxia-telangiectasia and Rad3-related (ATM/ATR) homologs, Mec1/Tel1, and is propagated via the effector kinases Chk1 and Rad53 (the Chk2 homolog). DNA damage sites are recognized by two different types of sensors, specific for single-strand DNA (ssDNA) or double-strand breaks (DSBs). RPA (a eukaryotic ssDNA-binding protein) recognizes ssDNA damage sites in cooperation with replication factor C (RFC)-like and PCNA-like (the 9-1-1) complexes. The Mre11 complex consists of three highly conserved members—MRE11, RAD50, and XRS2 (NBS1 in mammals)—and appears to be primarily required for signaling the presence of DSBs (reviewed in Zhou and Elledge 2000; D'Amours and Jackson 2002; Petrini and Stracker 2003; Stracker et al. 2004).

Spo11 catalyzes the formation of DSBs to initiate meiotic recombination. In rad50S mutants, Spo11 remains covalently attached at the DSB ends that it forms (Keeney et al. 1997). Sae2Δ cells exhibit the same retention of Spo11 at meiotic DSBs, consistent with the view that, in both mutants, Mre11 nuclease function is impaired (Keeney and Kleckner 1995; McKee and Kleckner 1997; Prinz et al. 1997). This view is supported by the fact that Spo11 retention is also seen in nuclease-deficient alleles of MRE11 (Nairz and Klein 1997; Moreau et al. 1999).

In vitro, Mre11 has both endo- and exonuclease activity (D'Amours and Jackson 2002). Mutations of conserved histidine residues (e.g., H125N) in the phsophoesterase domain eliminate both activities; however, in vivo Mre11-H125N has apparently normal exonuclease activity in degrading an HO-endonuclease-generated DSB (Moreau et al. 2001; Lee et al. 2002). These data, and the fact that it is a 3′-5′ exonuclease, support the interpretation that the Mre11 complex is not directly involved in the 5′-3′ resection of DSB ends. Spo11 removal from meiotic DSBs and DNA hairpin cleavage in mitotic cells, both presumably requiring endonuclease activity, are abrogated by Mre11 nuclease deficiency (Lobachev et al. 2002; Yu et al. 2004).

rad50S and sae2Δ also affect Mre11 nuclease functions in mitotic cells (Rattray et al. 2001). Both mutations impair the processing of hairpin DNA structures (Lobachev et al. 2002; Yu et al. 2004) and camptothecin (CPT)-induced Top1 cleavage complexes (Vance and Wilson 2002; Deng et al. 2005). These phenotypes are also exhibited by nuclease-deficient mre11 mutants. In addition, rad50S and sae2Δ mutants exhibit synthetic lethality with rad27Δ (FEN1 in human), another flap endonuclease that is required for Okazaki fragment maturation (Debrauwere et al. 2001; Moreau et al. 2001). It has recently been shown that Sae2 itself possesses endonuclease activity, suggesting the possibility that Sae2 may play dual roles: as a regulator of Mre11 nuclease function and/or as a nuclease (Lengsfeld et al. 2007).

Previously, we demonstrated that both rad50S and sae2Δ suppress the checkpoint phenotype of Mec1 deficiency via a conserved pathway dependent on the Mre11 complex and Tel1 (referred to as the TM pathway) (Usui et al. 2001, 2006; Morales et al. 2005). sae2Δ also prevents the normal turning off of the DNA damage checkpoint once a DSB is repaired (Clerici et al. 2006). In contrast, overexpression of SAE2 suppresses both MEC1 and TEL1 kinase activity modifying Rad53 and also prevents the damage-induced phosphorylation of Mre11. These observations suggest that Sae2 may be an inhibitory factor for the Mre11-complex checkpoint function.

Supporting this possibility, we report here that SAE2 overexpression enhances the methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) sensitivity of mec1Δ rad50S cells, suggesting inhibition of the TM pathway. We have isolated sae2 alleles that fail to enhance this MMS sensitivity and recovered among them sae2 alleles that alter the Mre11 effect on specific types of substrates. For example, the N terminus of Sae2 appears to be required specifically for the Mre11 nuclease to open hairpin DNA structures, but not for Spo11 cleavage. Further, Sae2 appears to function as an oligomer, and self-interaction is correlated with Sae2 influence on the Mre11 complex's nuclease and checkpoint functions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains:

The following strains are of W303 background (MATa, -α or a/α trp1-1 ura3-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 ade2-1 can1-100 RAD5+, originally from R. Rothstein): JPY2252 (MATa sae2Δ), JPY2253 (MATa FLAG-SAE2), JPY2254 (MATa FLAG-sae2-12), JPY2255 (MATa FLAG-sae2-58), JPY2256 (MATa FLAG-sae2-1), JPY2258 (MATα sae2Δ), JPY2259 (MATα FLAG-SAE2), JPY2261 (MATα FLAG-sae2-1), JPY2262 (MATα FLAG-sae2-12), JPY2264 (MATα FLAG-sae2-58), JPY2290 (MATα FLAG-sae2-51), JPY2308 (MATa/α sae2Δ/sae2Δ), JPY2309 (MATa/α FLAG-SAE2/FLAG-SAE2), JPY2310 (MATa/α FLAG-sae2-1/FLAG-sae2-1), JPY2311 (MATa/α FLAG-sae2-12/FLAG-sae2-12), JPY2312 (MATa/α FLAG-sae2-58/FLAG-sae2-58), JPY2318 (MATa/α sae2Δ/FLAG-sae2-51), JPY2335 (MATa/α rad27Δ/RAD27 sae2Δ/SAE2), JPY2338 (MATa/α rad27Δ/RAD27 FLAG-SAE2∷LEU2/SAE2), JPY2339 (MATa/α rad27Δ/RAD27 FLAG-sae2-1∷LEU2/SAE2), JPY2340 (MATa/α rad27Δ/RAD27 FLAG-sae2-12∷LEU2/SAE2), JPY2344 (MATa/α rad27Δ/RAD27 FLAG-sae2-51∷LEU2/SAE2), JPY2345 (MATa/α rad27Δ/RAD27 FLAG-sae2-58∷LEU2/SAE2), JPY2518 (MATa FLAG-SAE2∷LEU2 mec1Δ sml1Δ), JPY2540 (MATa FLAG-sae2-1∷LEU2 mec1Δ sml1Δ), JPY2557 (MATa FLAG-sae2-12∷LEU2 mec1Δ sml1Δ), JPY2589 (MATa FLAG-sae2-51∷LEU2 mec1Δ sml1Δ), JPY2606 (MATa FLAG-sae2-58∷LEU2 mec1Δ sml1Δ), JPY2666 (MATa sae2Δ mec1Δ sml1Δ), JPY2247 (MATa SAE2-HA∷URA3, YLL1103 from Longhese; Baroni et al. 2004), JPY2248 (MATa SAE2-HA∷URA3 mec1Δ sml1Δ, DMP380 from Longhese; Baroni et al. 2004). The following strains are of A364a background: JPY319 (MATa WT), JPY321 (MATa mec1-1 sml1), JPY326 (MATa rad50S mec1-1 rad53 sml1), JPY352 (MATa rad50S mec1-1 sml1), JPY847 (MATa rad50S mec1-1 tel1Δ sml1), JPY848 (MATa rad50S sae2Δ mec1-1 sml1), JPY851 (MATa sae2Δ mec1-1 sml1), JPY3009 (MATa mec1-1 sml1 FLAG-SAE2), JPY3010 (MATa mec1-1 sml1 FLAG-sae2-1), and JPY3011 (MATa mec1-1 sml1 FLAG-sae2-12). The following strains are of SK1 background: JPY839 (MATa rad50S sae2ΔTRP1) and JPY840 (MATa sae2). The following strains were used for chromatin immunoprecipitation: JPY1475 (MATa WT hoΔ hmlΔ∷ADE1 hmrΔ∷ADE1 ade1 leu2-3,112 lys5 trp1∷hisG ura3-52 ade3∷GAL∷HO bar1∷ADE3∷bar1, H1072 from Lichten; Shroff et al. 2004) and JPY2319 (MATa sae2Δ).

Construction of yeast strains:

Yeast strains carrying the SAE2 or RAD27 deletion were obtained by PCR disruptions using pFA vectors containing KAN (G418 resistant), HYG (hygromycin resistant), or TRP1 markers. For the integration of sae2 mutants, the SAE2 open reading frame (ORF) was swapped with either a KAN or a HYG marker and FLAG-SAE2 or FLAG-sae2 mutants were integrated at this locus. Deletions and integrations of these genes were verified by PCR. All primers and plasmids used for the mutant constructions and genotyping are available upon request.

sae2 mutant screen:

JPY352 (rad50S mec1) strains were cotransformed with PCR random-mutagenized FLAG-sae2 fragments and pRS425 vector digested with SacII and KpnI. Transformants were replica plated on media containing 0.007% MMS. rad50S mec1 transformed with empty vector and FLAG-SAE2/2μ were used as controls. The sae2 mutants were screened for the inability to increase MMS sensitivity of rad50S mec1 cells. Approximately 20,000 colonies were screened for this phenotype. To eliminate the mutants that do not express Flag-sae2 proteins, trichloroacetic acid (TCA)-extracted whole proteins were prepared and expression of sae2 mutants was analyzed by Western blot using a monoclonal Flag-antibody. FLAG-sae2 mutant plasmids were then rescued from these cells. The MMS sensitivity and protein expression of these clones were reverified. A total of 15 sae2 mutants were isolated and sequenced. To compensate for the bias in screening, due to the N-terminal tagging of Sae2, Sae2 was tagged at the C terminus with HA. Three N-terminal truncation alleles, sae2-82, sae2-139, and sae2-146, were isolated by the C-terminal HA tagging. These were N-terminal 120-amino-acid truncation mutants (referred to as a sae2-ΔN120). In addition, two N-terminal truncations, sae2-ΔN170 and -ΔN225, were also generated.

Analysis of MMS, UV, and CPT sensitivity:

Fresh growing cells were serially diluted and spotted onto solid media containing different concentrations of indicated drugs or irradiated with indicated UV doses. Plates were photographed after 3 days of incubation at 30°. For the transient treatment, exponentially growing cells were untreated or treated with the indicated concentrations of drugs and the same number of cells was spotted onto a YPD plate. The percentage of viability was determined by counting colonies after 3 days of incubation.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis:

About 5 × 108 cells were lysed in lysis buffer [25 mm Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mm EDTA, 0.5% NP-40, 10% glycerol, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 1× complete and 150 mm NaCl] using FASTprep (Q-BIOgene). Extracts were immunoprecipitated with HA or Flag antibody. Coprecipitated proteins were analyzed by Western blot.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation and real-time PCR:

Cell extracts were prepared as described (Shroff et al. 2004) and immunoprecipitated with anti-Mre11 serum. The precipitated DNA was quantitated by real-time PCR using the 7900HT (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and Light Cycler 480 sequence detection system (Roche). Amplified double-stranded DNA product during 40 cycles was detected by SYBR Green I. All measurement of PCR product was quadruplicated and compared with 1000-fold linear range standard DNA controls prepared from the wild-type strain. Efficiency of Mre11 association with a HO break, 0.05 and 66 kb from the break, was obtained by normalizing the chromatin-immunoprecipitated DNA to input DNA. The sequences of primers used for the real-time PCR are available upon request.

Checkpoint, adaptation, and recovery assays:

For G2/M checkpoint assays, cells were arrested in G1 with α-factor and released into 0.02% or 0.03% MMS. Cells were collected at the indicated time points and stained with DAPI. The percentage of nuclear division was assessed as described (Usui et al. 2001).

YMV80 sae2Δ cells transformed with the sae2 plasmids (CEN) were assayed for repair and recovery after a single HO–DSB induction. To assay G2/M arrest and recovery, cells were grown overnight either in YEP–lactate media or in synthetic media plus raffinose at 30°. Galactose was added to the liquid culture to a final concentration of 2% and the culture was incubated at 30° for a further 6 hr. Cells were then spread onto YEP–galactose plates and incubated at 30° overnight. At 24 hr the plates were examined for the percentage of cells that were still arrested as G2/M dumbbells, as an indication of failed repair or delayed recovery. In parallel, samples were plated directly from preinduction media onto YEPD and YEP–galactose plates to determine the percentage of viability.

Telomere Southern blot:

XhoI-digested genomic DNA was analyzed for telomere length by Southern blot hybridizing 32P-labeled telomere oligo probes.

Analysis of meiotic DSB processing:

Following 4.5 and 9 hr in sporulation media, EcoRI-digested genomic DNA was assayed for meiotic DSB processing at the THR4 locus by Southern blot.

RESULTS

Sae2 blocks the TM pathway:

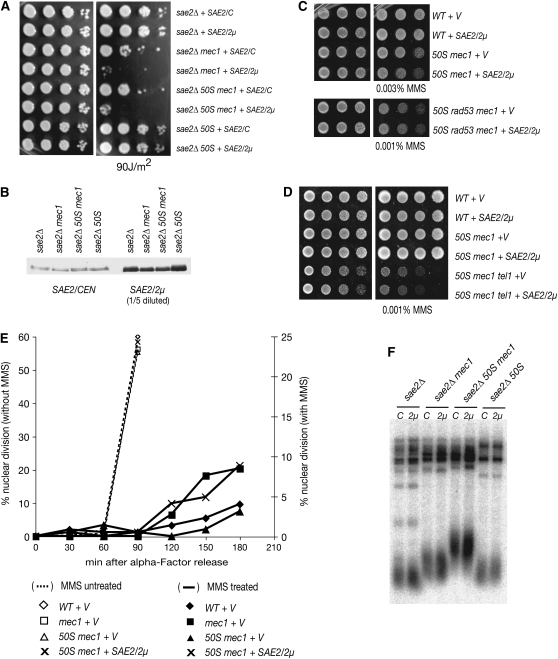

We showed previously that Sae2 deficiency suppresses the MMS sensitivity of mec1 mutants (Usui et al. 2001) through the TM pathway, which suggests that Sae2 may antagonize Mre11-complex checkpoint or DNA repair functions. This view predicts that SAE2 overexpression would increase the sensitivity of mec1 and rad50S mec1 cells to genotoxic stress. To test this idea, Flag-epitope-tagged SAE2 in a high-copy (2μ) or in a low-copy (CEN) plasmid was introduced into sae2Δ strains that were otherwise wild type, rad50S, mec1, or rad50S mec1. High-copy plasmid produced at least five times more Flag-Sae2 proteins compared to SAE2/CEN (Figure 1B). SAE2 overexpression increased sensitivity to UV-induced damage (Figure 1A) in mec1 and rad50S mec1 cells, whereas it did not affect wild type or rad50S. Serially diluted cells carrying SAE2 plasmids were transferred onto solid media containing MMS, and SAE2 overexpression again showed increased MMS sensitivity only in the absence of mec1 (Figure 1C)

Figure 1.—

Sae2 blocks the TM pathway. (A) SAE2 overexpression increases the UV sensitivity of mec1 and rad50S mec1. Yeast strains carrying FLAG-SAE2/CEN (low copy) or FLAG-SAE2/2μ (high copy) were 1/10 serially diluted, spotted onto plates, and left untreated (left) or irradiated with UV (right). (B) Whole-cell extracts were prepared from the strains listed in A by TCA preicipitation and were Western blotted with anti-Flag antibody. Extracts from high-copy transformants were diluted to 1/5. (C and D) SAE2 overexpression influences TEL1- and RAD53- dependent pathways. MMS sensitivity of rad50S mec1 tel1 or rad50S mec1 rad53 cells carrying empty vector or FLAG-SAE2/2μ was determined by spotting experiments (1/5 serial dilution). (E) SAE2 overexpression blocks G2/M checkpoint. G1-arrested cells were released into 0.02% MMS and the percentage of binucleated cells was determined. Solid symbols with straight lines indicate MMS-treated samples; wild type with 2μ vector (♦), mec1 with 2μ (▪), rad50S mec1 with 2μ (▴), and rad50S mec1 with SAE2/2μ (×). Open symbols with dashed lines indicate MMS-untreated samples. (F) Telomere length control is not a primary target of Sae2 in regulation of the TM pathway. The strains with either SAE2/CEN or SAE2/2μ were analyzed for telomere length by Southern blot.

The effect of SAE2 overexpression on mec1 and rad50S mec1 cells reflected an effect on the TM pathway. SAE2 overexpression was carried out in rad50S mec1 rad53Δ and rad50S mec1 tel1Δ mutants; both Rad53 and Tel1 deficiency block the TM pathway (Usui et al. 2001). SAE2 overexpression did not further increase the MMS sensitivity of rad50S mec1 cells lacking either RAD53 or TEL1 (Figure 1, C and D). The effect of SAE2 overexpression on the G2/M checkpoint was assessed by releasing G1-arrested cells into 0.02% MMS and scoring nuclear division by counting binucleated cells (Figure 1E). Wild-type cells were arrested in G2/M, whereas binucleated cells accumulated in mec1 cells. The mec1 arrest defect was suppressed by rad50S as shown previously; however, in rad50S mec1 cells overexpressing SAE2, binucleated cells were again increased, similar to the mec1 mutant. These data argue that SAE2 overexpression impairs the TM pathway, supporting the interpretation that Sae2 and the Mre11 complex functionally interact.

Both the Mre11 complex and Tel1 influence telomere maintenance (Ritchie and Petes 2000; D'Amours and Jackson 2002; Lundblad 2002; Pandita 2002; d'Adda di Fagagna et al. 2003). sae2Δ cells exhibited slightly elongated telomeres and caused further telomere elongation in combination with a mec1 mutation, similar to observations of rad50S cells (Kironmai and Muniyappa 1997; data not shown). This telomere lengthening was dependent on TEL1, again suggesting a dependence on the TM pathway (data not shown). Thus, we examined whether SAE2 overexpression inhibited telomere lengthening, but found that SAE2 overexpression did not affect telomere length, regardless of the genotypes (Figure 1F). UV sensitivity of mec1 rad50S cells was not affected by extremely shortened or elongated telomeres caused by tlc1Δ, a RNA component of the telomerase complex, or by rif1Δ, a negative regulator of telomerase (data not shown). These data suggest that controlling telomere length is not a primary target of Sae2 in regulation of the TM pathway.

Sae2 influences DNA repair events that require the Mre11 nuclease:

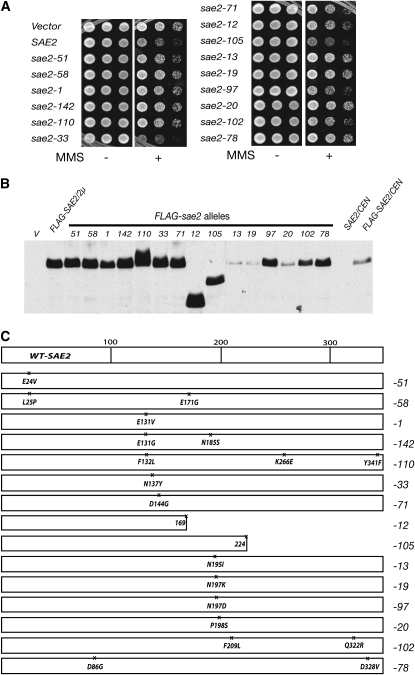

To gain mechanistic insight regarding the functional interaction between Sae2 and the Mre11 complex, we mutagenized SAE2 and screened for alleles that failed to sensitize rad50S mec1 cells to MMS. Approximately 20,000 colonies of rad50S mec1 strains transformed with randomly mutagenized FLAG-sae2 fragments were tested on solid media containing 0.007% MMS. Fifteen alleles were isolated (Figure 2C). sae2-13, -19, and -20 appeared to encode unstable sae2 proteins and behaved similarly to the empty vector control. These mutations are clustered between amino acids (aa) 195–198 (Figure 2C), indicating that this region is important for protein stability. Unexpectedly, overexpression of sae2-33 or sae2-105 further sensitized rad50S mec1 to MMS compared to wild-type SAE2 overexpression.

Figure 2.—

Isolation of sae2 alleles that fail to sensitize rad50S mec1 to MMS. (A) rad50S mec1 (JPY352) cells carrying sae2 mutants isolated from the screen were reverified for the MMS sensitivity by spotting experiments (1/5 serial dilution, 0.006% MMS). (B) Protein expression level of sae2 mutants. The TCA-extracted whole proteins were prepared from sae2Δ mec1 (JPY851) carrying sae2 mutant plasmid (2μ) and Western blotted with anti-Flag antibody. (C) Schematic of sae2 alleles and the location of mutation sites.

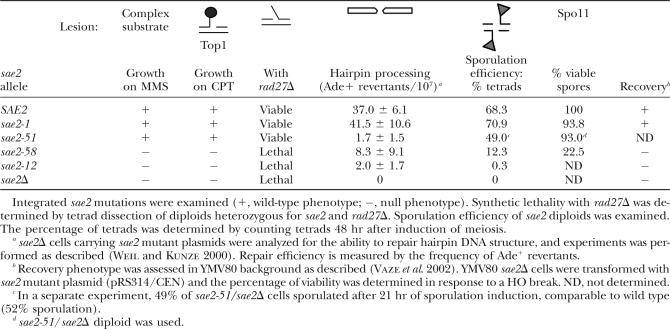

sae2Δ phenocopies Mre11 nuclease deficiency in the repair of CPT-induced DNA damage, the metabolism of DNA hairpins, the processing of meiotic DSBs, and synergism with rad27Δ (Cao et al. 1990; Keeney and Kleckner 1995; Nairz and Klein 1997; Prinz et al. 1997; Debrauwere et al. 2001; Moreau et al. 2001; Lobachev et al. 2002; Vance and Wilson 2002; Yu et al. 2004; Deng et al. 2005). As each of these contexts are likely to require the metabolism of distinct DNA lesions, we asked whether any of the sae2 alleles obtained were separation-of-function mutants that affected some Mre11-dependent processes while leaving others intact.

sae2 alleles were integrated at the SAE2 locus and analyzed as described below. The data obtained are summarized in Table 1. sae2-12 and sae2-58 strains exhibited MMS and CPT sensitivity comparable to sae2Δ, whereas sae2-1 and sae2-51 were indistinguishable from wild type in this regard (Figure 3A). Accordingly, sae2-12 and -58 behaved as sae2Δ and suppressed the MMS sensitivity of mec1Δ (Figure 3B). Although sae2-1 did not exhibit MMS or CPT sensitivity (Figure 3A), as with sae2-12 and sae2-58, this allele behaved as a hypomorphic mutation with respect to the suppression of mec1Δ MMS sensitivity. As expected, sae2-51 behaved as wild type and did not affect the MMS sensitivity of mec1Δ.

TABLE 1.

Summary of mutant sae2 phenotypes

Figure 3.—

Sae2 influences DNA repair events that require the Mre11 nuclease activity. Integrated sae2 alleles were examined for their phenotypes. (A) MMS and CPT sensitivity of sae2 single mutants (1/5 serial dilution). (B) MMS and CPT sensitivity of sae2 mutants in the absence of MEC1 (1/5 serial dilution). (C) The ability to remove Spo11-DNA intermediates. Accumulation of unprocessed DSBs in sae2 mutant diploids was determined by Southern blot. Cells were collected at 4.5 and 9 hr after meiosis induction. EcoRI-digested genomic DNA prepared from these cells was examined for accumulation of unprocessed DSB at the THR4 locus by Southern blot. The unprocessed DSBs were detected as a discrete 5.7-kb fragment band. (D) Sporulation efficiency. Cells were collected at 48 hr after meiosis induction and stained with DAPI. The percentage of tetrads was plotted.

sae2Δ did not suppress the mec1 growth defect in response to CPT, in contrast to MMS treatment (Figure 3B). However, a sae2-1 mec1Δ double mutant grew about five times better than mec1Δ or sae2Δ mec1Δ strains on a CPT-containing plate. These data indicate that Mec1 influences the regulation of Mre11-complex nuclease function by Sae2.

To examine whether the sae2 mutants were proficient in Spo11 removal from meiotic DSBs, diploid W303 cells homozygous for each of the sae2 alleles were examined for DSB processing (Figure 3C). Genomic DNA prepared from the sae2 mutant cells at 4.5 and 9 hr after meiosis induction was examined for accumulation of unprocessed DSBs at the THR4 meiotic hotspot by Southern blot. Unprocessed DSBs in sae2Δ cells were detected as a discrete 5.7-kb fragment band (Figure 3C). The unprocessed DSBs in sae2Δ, sae2-12, and sae2-58 homozygotes were two to three times more abundant than in wild type at 4.5 and 9 hr, while sae2-1 was similar to wild type. Since unprocessed DSBs block spore formation, we also tested sporulation efficiency in the sae2 mutants. The trend observed in DSB accumulation was recapitulated in spore viability. sae2-1 cells (70.9%) sporulated and 93.8% of the spores were viable, comparable to wild type. In contrast, only 12.3 and 0.3% of cells formed tetrads in sae2-58 and sae2-12 diploids (Figure 3D and Table 1).

The Mre11 nuclease and Sae2 are required to open DNA hairpin structures (Lobachev et al. 2002; Yu et al. 2004). To examine the ability of the sae2 mutants to process hairpin structures, we took advantage of a transposition assay system in budding yeast. In this assay strain (Weil and Kunze 2000), a maize Ds transposon is inserted in the middle of the ADE2 ORF. Expression of the maize Ac transposase excises the Ds element and leaves a hairpin at the ends of the adjacent chromosomal DNA. These hairpins have to open to be repaired by DSB repair pathways. Repair efficiency can be estimated by the frequency of Ade+ revertants. sae2Δ strains carrying sae2 mutant plasmids (2μ) were examined for the frequency of Ade+ revertants (Table 1 and supplemental Table S1 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/). SAE2 gave ∼37.0 revertants/107 cells whereas sae2-12, sae2-58, or empty vector transformants gave 2.0, 8.3, or 0 revertants, respectively. sae2-1 (41.5/107) was similar to wild type. Although sae2-51 behaved as wild type with respect to checkpoint regulation and to MMS and CPT sensitivity as well as meiotic progression (Table 1; supplemental Table S1 and Figure S2 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/), this allele exhibited a severe hairpin repair defect (1.7/107). sae2-51 contains a E24V mutation, indicating that the N-terminal end of Sae2 may be specifically required for the Mre11 nuclease to open hairpin DNA. We note that another N-terminal mutant, sae2-58, also cannot process hairpin ends.

Mutations that impair Mre11 nuclease function in vivo, such as sae2Δ and mre11-H125N, are synthetically lethal with Rad27 deficiency (Debrauwere et al. 2001; Moreau et al. 2001). Synthetic lethality between rad27Δ and sae2 mutants was analyzed by tetrad dissection. sae2-12 and sae2-58 were each lethal with rad27Δ, but sae2-1 rad27Δ and sae2-51 rad27Δ double mutants were viable (Table 1).

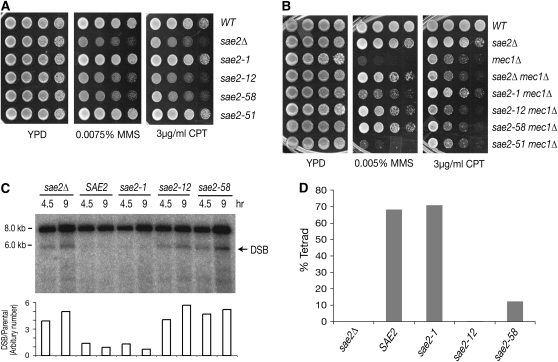

Role of Sae2 in checkpoint activation and inactivation:

Upon MMS treatment, wild-type cells arrest in G2/M, whereas checkpoint-deficient mec1 mutants fail to arrest and undergo nuclear division accompanied by loss of viability. We showed that sae2Δ suppresses the checkpoint defects associated with Mec1 deficiency (Usui et al. 2001). Integrated sae2-1, sae2-12, and sae2-58 were assayed for the rescue of the G2/M checkpoint defect of mec1 cells. G1-arrested cells were released into MMS and binucleated cells were counted every 30 min. As shown in Figure 4A, wild-type cells were arrested in G2/M while binucleated cells accumulated over time in mec1 mutants. Approximately 25–29% of mec1 cells underwent mitosis at 150 min after MMS treatment. This mec1 defect was rescued in sae2-12 (Figure 4A, a) or sae2-58 (Figure 4A, b), indicating that these two alleles behaved as sae2Δ and thus were able to rescue the mec1 checkpoint defect. On the other hand, ∼16% of sae2-1 mec1 cells were similar to mec1 and went through mitosis 120 and 150 min after MMS treatment (Figure 4A, a). Hence, as in other determinations, this allele's behavior is similar to wild type with respect to TM pathway regulation.

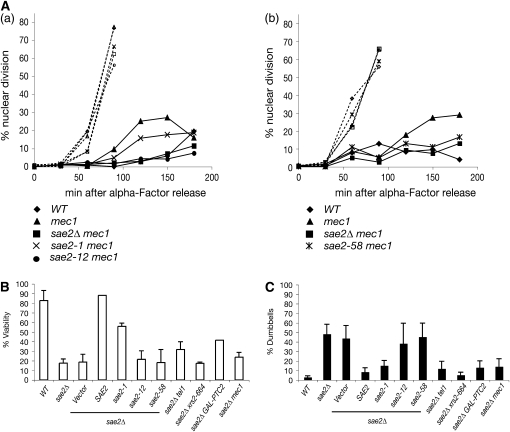

Figure 4.—

Role of Sae2 in checkpoint activation and inactivation. (A) The rescue of the G2/M checkpoint defect of mec1. G1-arrrested cells were released into 0.02% (a) or 0.03% (b) MMS and the percentage of nuclear division was analyzed by counting binucleated cells. Open symbols with dashed lines indicate MMS-untreated samples. Closed symbols with straight lines indicate MMS-treated samples. Wild type (♦), mec1 (▴), sae2Δ mec1 (▪), sae2-1 mec1 (x), sae2-12 mec1 (•), and sae2-58 mec1 ( ). (B and C) Recovery and viability in response to an HO break. The percentage of viability (B) and of G2-arrested cells (C) were determined in YMV80 sae2Δ cells carrying SAE2 or sae2 mutant plasmids (CEN) and in sae2Δ tel1, sae2Δ xrs2-664, sae2Δ GAL-PTC2, and sae2Δ mec1 mutant cells.

). (B and C) Recovery and viability in response to an HO break. The percentage of viability (B) and of G2-arrested cells (C) were determined in YMV80 sae2Δ cells carrying SAE2 or sae2 mutant plasmids (CEN) and in sae2Δ tel1, sae2Δ xrs2-664, sae2Δ GAL-PTC2, and sae2Δ mec1 mutant cells.

When DNA damage is repaired, cells must inactivate checkpoint pathways to resume the cell cycle; this is defined as recovery from checkpoint arrest (Lee et al. 1998; Pellicioli et al. 2001; Vaze et al. 2002; Leroy et al. 2003). It has recently been shown that sae2Δ cells are defective for recovery from arrest induced by a long-lived HO-endonuclease-mediated DNA break (Clerici et al. 2006). Accordingly, we examined the panel of sae2 mutants for their ability to recover from checkpoint arrest. In strain YMV80, DSBs induced by HO endonuclease are repaired by single-strand annealing (SSA) ∼6 hr after HO induction (Vaze et al. 2002). The DNA damage checkpoint is fully activated in 2 hr after the HO-DSB formation but is turned off for cells to resume cell cycle progression when SSA is completed. YMV80 sae2Δ cells were transformed with the sae2 plasmids (CEN) and then assayed for recovery after HO induction by determining the percentage of cells with dumbbell shape, indicative of cells that are permanently arrested in G2. sae2Δ cells carrying a SAE2 plasmid maintained 88% viability (Figure 4B) and only 8.3% cells were still arrested in G2 at 24 hr after HO induction (Figure 4C). In contrast, the sae2Δ cells showed 18.7% viability and 43.8% cells arrested in G2, consistent with previous findings (Clerici et al. 2006). sae2-1 was proficient in recovery similar to wild type (55.8% viability, 15.1% arrest), and sae2-12 and sae2-58 behaved as null mutants.

In contrast to results reported by Clerici et al. (2006), the recovery defect of sae2Δ was rescued by tel1Δ. Recovery was also rescued by C-terminal mutation of Xrs2 that fails to associate the Mre11 complex with Tel1, xrs2-664 (Shima et al. 2005). Finally, the recovery defect of sae2Δ was suppressed by PTC2 overexpression (a regulator subunit of phosphatase) and mec1Δ, both of which prevent maintenance of Rad53 phosphorylation (Figure 4C). However, the viability was not significantly suppressed by these mutations or PTC2 overexpression (Figure 4B). These data indicate that compromising the checkpoint or the untimely turning off of it can rescue DNA damage arrest without fully complementing the viability.

Influence of Sae2 on Mre11–DSB association:

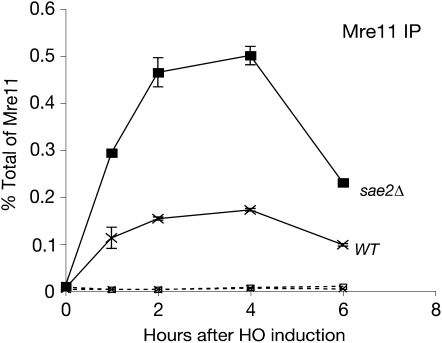

Physical association of the Mre11 complex with DSBs is vital for its function in checkpoint activation as well as in meiosis (Usui et al. 2001; Petrini and Stracker 2003; Borde et al. 2004; Lisby et al. 2004; Shroff et al. 2004). Therefore, we hypothesized that the inhibition of the TM pathway by SAE2 overexpression limits Mre11 association with DSBs. Indirect evidence for this possibility comes from the apparent requirement for Sae2 in the formation of Mre11 “repair” foci (Lisby et al. 2004; Clerici et al. 2006). To test this hypothesis, we carried out chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments to assess Mre11-complex association at an HO break in a hmrΔ hmlΔ strain to prevent repair by gene conversion (Shroff et al. 2004). Wild-type and sae2Δ cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-Mre11 serum, and Mre11 association at 0.05 kb from the HO break was determined by quantitative PCR. As previously reported (Lisby et al. 2004; Clerici et al. 2006), Mre11 associated with a HO break two to three times more efficiently in sae2Δ cells, compared to wild type, although Sae2 deficiency did not change the association and dissociation kinetics (Figure 5). Overexpression did not affect Mre11 association (supplemental Figure S5 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/). These data suggest that regulation of Mre11–DSB association is not the basis of Sae2's influence on Mre11-complex-mediated checkpoint functions.

Figure 5.—

Influence of Sae2 on Mre11–DSB association. Absence of Sae2 increases Mre11 association with DSB. Efficiency of Mre11–DSB association was determined by ChIP and real-time PCR. Mre11 association at 0.05 kb from the break in wild type (x) and in sae2Δ (▪). The dashed lines indicate Mre11 association at the 66-kb site.

Sae2 self-interaction via two domains is critical for its cellular functions:

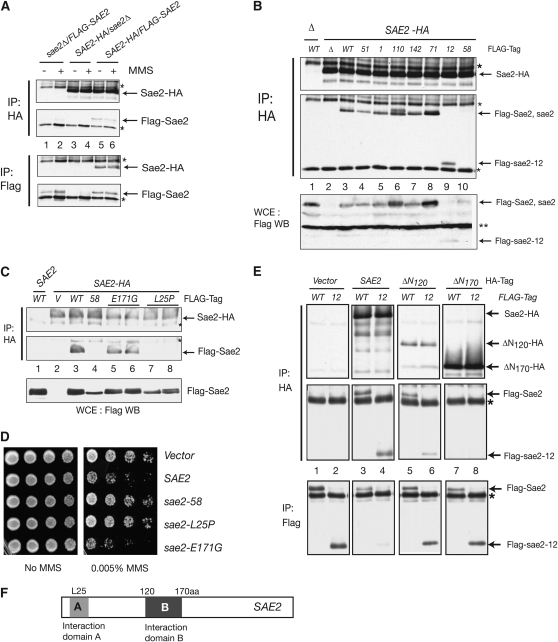

Sae2–Sae2 interaction was observed in a global analysis of two-hybrid interactions (Ito et al. 2001). To determine whether the phenotypes of our sae2 mutant panel could be associated with compromised self-association, we constructed diploid strains carrying integrated FLAG-SAE2 and SAE2-HA and examined their interaction by co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiments. Cells were either untreated or treated with 0.03% MMS for 2 hr and extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA or anti-Flag antibody. As shown in Figure 6A, Flag-Sae2 coprecipitated with Sae2-HA, and Sae2-HA also coprecipitated with Flag-Sae2 (lanes 5 and 6) regardless of MMS treatment, indicating that Sae2 interacts with Sae2 independently of DNA damage.

Figure 6.—

Sae2 self-interaction via two domains is critical for its cellular functions. (A) Sae2 self-interacts regardless of DNA damage. Interaction between Sae2-HA and Flag-Sae2 was examined in diploid strains carrying integrated SAE2-HA and FLAG-SAE2 by co-IP and Western blot. Cells were either untreated or treated with 0.03% MMS for 2 hr. (B) Sae2 self-interaction is required for its cellular functions. The interaction was examined in diploid strains carrying integrated SAE2-HA and FLAG-sae2 mutants by co-IP and Western blot. (C) Residue L25 is required for the Sae2 self-interaction. The interaction was examined in SAE2-HA strains carrying Flag-sae2 mutant plasmids (2μ). Two independent clones were analyzed for sae2-E171G and sae2-L25P mutants. (D) Residue L25 is required for the inhibition of the TM pathway. rad50S mec1 cells were transformed with either sae2-L25P or sae2-E171G and examined for MMS sensitivity (1/5 dilution). (E) The additional region between 120 and 170 aa is required for the Sae2 interaction. The interaction was examined in FLAG-SAE2 or FLAG-sae2-12 strains carrying the N-terminal truncation sae2 mutant plasmids (2μ). (F) Summary of Sae2 self-interaction domains. Two separate regions are required for the interaction between Sae2, a region containing L25 (domain A, light shading), and a region between 120 and 170 aa (domain B, dark shading). Asterisks (*) indicate antibody heavy and light chains. Double asterisks (**) indicate nonspecific signal.

To determine whether this interaction remains intact in sae2 mutants, we performed co-IP experiments in diploid strains carrying integrated SAE2-HA and FLAG-sae2 mutants. As shown in Figure 6B, among the full-length sae2 mutants, only sae2-58 did not coprecipitate with Sae2-HA (lane 10). sae2-58 is null for all phenotypes that we examined (Figure 3 and Table 1), indicating that Sae2–Sae2 interaction is required for its function. The sae2-12 protein, a C-terminal truncation mutant, coprecipitated with Sae2-HA (Figure 6B, lane 9), indicating that the interaction domain is located in the N-terminal region. sae2-58 contains two mutations in the N-terminal half, L25P and E171G. As shown in Figure 6C, we found that the region encompassing residue L25 is required for the interaction, since Sae2-HA IP pulled down sae2-E171G (lanes 5 and 6), but not sae2-L25P (lanes 7 and 8). Consistently, overexpression of sae2-L25P behaved as sae2-58, and sae2-E171G as wild type in the MMS sensitivity of rad50S mec1 (Figure 6D).

To further test the N-terminal domain of Sae2 in the self-interaction, we generated three N-terminal truncation mutants with a C-terminal HA tag (sae2-ΔN120, -ΔN170, and -ΔN225). Unexpectedly, sae2-ΔN120, which lost L25, pulled down wild-type Sae2 and sae2-12 (lanes 5 and 6), while sae2-Δ170 did not (lanes 7 and 8), demonstrating that the additional region between residues 120 and 170 is required for the interaction (Figure 6E). sae2-ΔN225 may be misfolded as HA antibody did not pull down this protein. We concluded that Sae2 oligomerization via two domains in the N-terminal half is required for DNA repair, meiosis, and checkpoint functions.

DISCUSSION

The genetic relationship between Sae2 and the Mre11 complex suggests that Sae2 may antagonize checkpoint regulation, while, on the other hand, enhancing Mre11 nuclease functions. In this study, we find evidence that the association of the Mre11 complex with DSB ends may be influenced by Sae2, but this does not appear to be the basis of the Sae2 effect on checkpoint signaling. The sae2 mutant panel confirms the influence on the DNA repair functions of the Mre11 complex and contains separation-of-function alleles that parse the influence on the Mre11 nuclease in substrate-specific manner. Finally, the data demonstrate that Sae2 self-interaction and oligomerization are critical to its function.

Specificity of Sae2 regulation of the Mre11 complex nuclease function:

As summarized in Table 1, we observed a consistent correlation between sae2 phenotypes in CPT sensitivity and the defects in processing of Spo11-DNA intermediates. Both these contexts presumably require the cleavage of DNA with protein covalently attached to it, suggesting that the Mre11-complex-dependent aspects of such cleavage events are strictly dependent upon Sae2. Alleles in this class are also synthetically lethal with Rad27 deficiency, further suggesting that the impairment of Mre11 nuclease function engendered by these sae2 alleles exacerbates the effects of DNA lesions stabilized by the absence of Rad27.

The sae2-51 allele (E24V) suggests that the influence of Sae2 on Mre11-complex-dependent hairpin cleavage may be mechanistically distinct. This allele exhibited severe defects in hairpin DNA repair, whereas it was proficient for other functions and did not exhibit MMS and CPT sensitivity, defects in Spo11 cleavage, or synthetic lethality with rad27Δ (Table 1, Figure 3, and supplemental Figure S2 and Table S1 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/). On the basis of a recent report on biochemical functions of Sae2 (Lengsfeld et al. 2007), endonuclease activity appears to be present at the C terminus. However, it did not rule out the possibility that the N terminus of Sae2 may also have hairpin processing activity, as the N-terminal truncation lost the ability to bind DNA. Therefore, it is possible that the N terminus of Sae2 may directly be required for cleavage of hairpin DNA or may specifically regulate Mre11-complex nuclease activity on hairpins. Further investigation of sae2-51 allele, in particular with respect to the disposition of E24 in the higher-order Sae2 structure and nuclease activity, will provide important insight regarding the biochemical functions of Sae2.

Despite failing to inhibit the TM pathway when overexpressed, the sae2-1 allele appeared to be wild type for most phenotypes (Figure 3 and Table 1). sae2-1 was not sensitive to CPT; however, sae2-1 suppressed the CPT sensitivity of a mec1Δ mutant, while sae2Δ and the remaining sae2 alleles were unable to suppress (Figure 3B). These results suggest that Mec1 influences Sae2 function, consistent with previous data demonstrating that it is a Mec1/Tel1 substrate (Baroni et al. 2004).

The only region of Sae2 that exhibits any conservation is at the C terminus (Figure 7A). This region appears to be required for Spo11 cleavage, as the overexpression of sae2-ΔN120 or sae2-ΔN170 could support sporulation in sae2Δ cells, whereas the overexpression of sae2-12 (ΔC170) could not (supplemental Table S1). In addition, overexpression of sae2-58 could partially suppress MMS sensitivity of sae2Δ, whereas sae2-ΔN170 could not (supplemental Table S1 and Figure S3). These observations indicate that sporulation and DNA repair are mechanically distinctive.

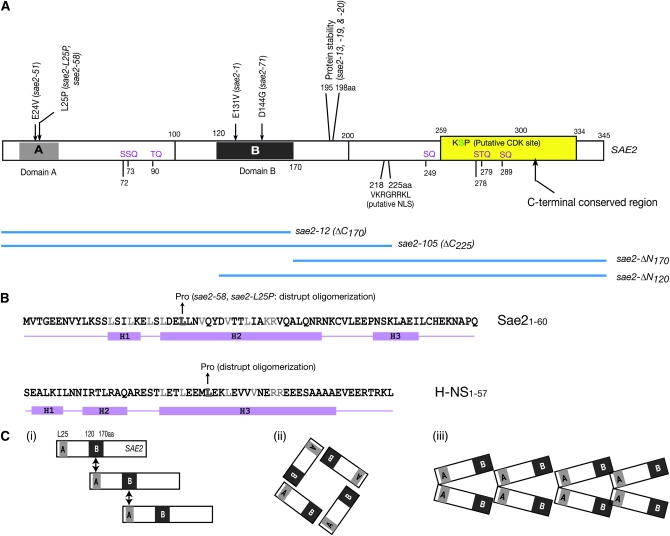

Figure 7.—

(A) Schematic of Sae2 and sae2 mutants. The sites of mutations in sae2 alleles and interaction domains (domains A and B) are illustrated. The yellow box indicates the region conserved among 10 fungal species, including Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Ashbya gossypii, Aspergillus nidulans, Candida glabrata, Debaryomyces hansenii, Fusarium graminearum, Kluyveromyces lactis, Magnaporthe grisea, Neurospora crassa, and Yarrowia lipolytica. Mec1/Tel1-phosphorylaion sites (SQ/TQ motif) are written in purple and the putative CDK phosphorylation (KSP) site in green in the yellow box. Truncation mutants are illustrated with blue bars. Putative nuclear localization signal (NLS). (B) Comparison between the N-terminal regions of Sae2 and H-NS. The N-terminal region of Sae2 is predicted to have three helices and this region may provide an interaction interface via the leucine-zipper structure. The similarity of secondary structure between the N terminus of Sae2 and bacterial protein H-NS is illustrated. Impairment of oligomerization by Leu-to-Pro mutation, together with the predicted secondary structure of the Sae2 N-terminal region, supports a possibility of coiled-coil interaction for Sae2 oligomerization. (C) Three different scenarios of Sae2 higher-order structure formation: (i) Sae2 may form an elongated filament-like structure via the interaction between domains A and B; (ii) Sae2 may form rather defined structure, for example, tetramers; the interaction between domains A and B may determine the shape and size of multimers; and (iii) Sae2 may dimerize first and then assemble to form a filament-like higher-order structure.

Role of Sae2 in TM pathway:

The genetic interaction between SAE2 and the Mre11 complex strongly suggests that they may physically interact. We can reproducibly co-immunoprecipitate Sae2 with components of the Mre11 complex, but this apparent interaction requires the presence of DNA (data not shown). Interestingly, upon cell fractionation, the majority of Sae2 was found associated with chromatin; hence, it remains a possibility that Sae2 and the Mre11 complex physically associate on chromatin.

Mre11 associates more efficiently with DSB sites in the absence of Sae2 (Figure 5), perhaps suggesting that the role of Sae2 may be to inhibit Mre11–chromatin association. Although GFP fusions of Sae2 were shown to form foci in response to ionizing radiation (Lisby et al. 2004), we did not detect Sae2–DSB association even when SAE2 was overexpressed (data not shown). In light of these observations, it would seem parsimonious to conclude that Sae2 does not inhibit Mre11-complex-dependent signaling by inhibiting DNA damage recognition; however, our data do not strictly rule out a kinetic effect of Sae2 on Mre11 complex dynamics at DSBs.

Higher-order structure of Sae2:

Sae2 has two interaction domains in the N-terminal half, a region around L25 (domain A) and a region between 120 and 170 amino acids (domain B). Co-immunoprecipitation data (Figure 6) indicates that interaction appears to occur via domain A and B, and A and A, but not B and B, as sae2-L25P lost the ability to associate with wild-type Sae2. This suggests several modes of interaction that could be organized to form oligomeric structures pictured in Figure 7C.

We favor the idea that Sae2 mulitmerizes as opposed to simple dimerization. The affect of overexpressing sae2 mutations in rad50S mec1Δ cells is influenced by the presence of a wild-type SAE2 gene on the chromosome. For example, the rescue of mec1Δ MMS sensitivity by rad50S was not inhibited by sae2-1 overexpression (Figure 2A); hence, even though sae2-1 is present in at least 5- to 10-fold excess, wild-type Sae2 protein exerts a significant effect. In contrast, overexpressing sae2-1 with no wild-type Sae2 present abrogated the suppressive effect of sae2Δ on mec1Δ (supplemental Figure S1), suggesting that overproduced sae2-1 protein may be able to form partially functional homomultimers. Overexpression of seven of the sae2 mutants (sae2-51, -71, -78, -97, -102, -110, and -142) showed similar phenotypes to sae2-1 overexpression (supplemental Table S1 and Figure S1). Five of these alleles (sae2-1, -51, -71, -110, and -142) have mutations in one of the interaction domains. Sae2–Sae2 self-association, however, appears to be intact in all of these sae2 mutants. These features are similar to some of the dominant-negative p53 mutants that interact with wild-type p53, resulting in dysfunctional tetramer formation (Milner and Medcalf 1991; Sun et al. 1993; Wang et al. 1994).

Alternatively, Sae2 may dimerize first and then self-assemble to form higher-order structure (Figure 7C, iii), similar to H-NS, a nucleoid-associated protein in bacteria (Dorman 2004). H-NS contains an N-terminal oligomerization domain (Bloch et al. 2003), and structural- and microscopy-based studies have shown that a coiled-coil interaction between helix H3 (rich in Leu and Val) of two H-NS proteins mediates the dimerization (Ueguchi et al. 1996; Dame et al. 2000; Esposito et al. 2002; Bloch et al. 2003). Head-to-tail assembly of the dimers then forms a filament-like, higher-order structure. The mutation of Leu29 to proline, a helix breaker, results in the inability of H-NS to oligomerize, presumably by preventing formation of the initial dimers (Ueguchi et al. 1997). As illustrated in Figure 7B, residues 1–60 of the Sae2 N terminus are predicted to form three helices. Helix H2 consists of residues 22–45, with every 3–4 residues occupied by leucine or valine. Similar to the situation with H-NS, a Sae2 L25P mutation abolished the oligomerization of Sae2 (Figure 6C); in additon, overexpression of the H-NS oligomerization domain exhibited dominant-negative effects (Williams et al. 1996; Ueguchi et al. 1997), similar to some of our sae2 mutant alleles. Interestingly, however, an E24V mutation did not disrupt the Sae2 self-interaction, further supporting the idea that the N terminus of Sae2 may form a hydrophobic interaction surface, similar to H-NS.

A putative SAE2 homolog, CtIP, has recently been identified in humans, worms, and plants (Penkner et al. 2007; Sartori et al. 2007; Uanschou et al. 2007). CtIP has sequence homology to budding yeast SAE2 at the C-terminal region, a small domain that is conserved in several fungal species. Similar to sae2Δ, CtIP deficiency is associated with defects in processing of meiotic DSBs, and evidence for alteration in the processing of mitotic DSBs has been presented and CtIP appears to be required for recruitment of ATR in human cells (Sartori et al. 2007). The data presented here shed light on Sae2's mechanisms of action and illustrate that its influence on nuclease activities required for DSB metabolism varies according to the substrate, as well as the status of the checkpoint pathway.

Acknowledgments

We thank Maria Pia Longhese for the SAE2-HA strain and Michael Lichten for yeast strains for chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments; Gene Bryant and Daniel Spagna in the Mark Ptashne lab for technical help for real-time PCR; and the members of our labs for insightful discussion over the course of this work. This work was supported by grants GM56888 and GM59413 and the Joel and Joan Smilow Initiative (J.H.J.P.), grant GM61766 (J.E.H.) and National Science Foundation MCB-0344655, and Binational Agriculture Research and Development award IS-372305 (C.W.).

References

- Baroni, E., V. Viscardi, H. Cartagena-Lirola, G. Lucchini and M. P. Longhese, 2004. The functions of budding yeast Sae2 in the DNA damage response require Mec1- and Tel1-dependent phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24 4151–4165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, V., Y. Yang, E. Margeat, A. Chavanieu, M. T. Auge et al., 2003. The H-NS dimerization domain defines a new fold contributing to DNA recognition. Nat. Struct. Biol. 10 212–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borde, V., W. Lin, E. Novikov, J. H. Petrini, M. Lichten et al., 2004. Association of Mre11p with double-strand break sites during yeast meiosis. Mol. Cell 13 389–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, L., E. Alani and N. Kleckner, 1990. A pathway for generation and processing of double-strand breaks during meiotic recombination in S. cerevisiae. Cell 61 1089–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerici, M., D. Mantiero, G. Lucchini and M. P. Longhese, 2006. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Sae2 protein negatively regulates DNA damage checkpoint signalling. EMBO Rep. 7 212–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d'Adda di Fagagna, F., P. M. Reaper, L. Clay-Farrace, H. Fiegler, P. Carr et al., 2003. A DNA damage checkpoint response in telomere-initiated senescence. Nature 426 194–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dame, R. T., C. Wyman and N. Goosen, 2000. H-NS mediated compaction of DNA visualised by atomic force microscopy. Nucleic Acids Res. 28 3504–3510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amours, D., and S. P. Jackson, 2002. The Mre11 complex: at the crossroads of DNA repair and checkpoint signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3 317–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debrauwere, H., S. Loeillet, W. Lin, J. Lopes and A. Nicolas, 2001. Links between replication and recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a hypersensitive requirement for homologous recombination in the absence of Rad27 activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98 8263–8269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng, C., J. A. Brown, D. You and J. M. Brown, 2005. Multiple endonucleases function to repair covalent topoisomerase I complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 170 591–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman, C. J., 2004. H-NS: a universal regulator for a dynamic genome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2 391–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, D., A. Petrovic, R. Harris, S. Ono, J. F. Eccleston et al., 2002. H-NS oligomerization domain structure reveals the mechanism for high order self-association of the intact protein. J. Mol. Biol. 324 841–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito, T., T. Chiba, R. Ozawa, M. Yoshida, M. Hattori et al., 2001. A comprehensive two-hybrid analysis to explore the yeast protein interactome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98 4569–4574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeney, S., and N. Kleckner, 1995. Covalent protein-DNA complexes at the 5′ strand termini of meiosis- specific double-strand breaks in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92 11274–11278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeney, S., C. N. Giroux and N. Kleckner, 1997. Meiosis-specific DNA double-strand breaks are catalyzed by Spo11, a member of a widely conserved protein family. Cell 88 375–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kironmai, K. M., and K. Muniyappa, 1997. Alteration of telomeric sequences and senescence caused by mutations in RAD50 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Cells 2 443–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. E., J. K. Moore, A. Holmes, K. Umezu, R. D. Kolodner et al., 1998. Saccharomyces Ku70, Mre11/Rad50, and RPA proteins regulate adaptation to G2/M arrest after DNA damage. Cell 94 399–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. E., D. A. Bressan, J. H. J. Petrini and J. E. Haber, 2002. Complementation between N-terminal Saccharomyces cerevisiae mre11 alleles in DNA repair and telomere length maintenance. DNA Repair 1 27–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengsfeld, B. M., A. J. Rattray, V. Bhaskara, R. Ghirlando and T. T. Paull, 2007. Sae2 Is an endonuclease that processes hairpin DNA cooperatively with the Mre11/Rad50/Xrs2 complex. Mol. Cell 28 638–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leroy, C., S. E. Lee, M. B. Vaze, F. Ochsenbien, R. Guerois et al., 2003. PP2C phosphatases Ptc2 and Ptc3 are required for DNA checkpoint inactivation after a double-strand break. Mol. Cell 11 827–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisby, M., J. H. Barlow, R. C. Burgess and R. Rothstein, 2004. Choreography of the DNA damage response: spatiotemporal relationships among checkpoint and repair proteins. Cell 118 699–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobachev, K. S., D. A. Gordenin and M. A. Resnick, 2002. The Mre11 complex is required for repair of hairpin-capped double-strand breaks and prevention of chromosome rearrangements. Cell 108 183–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundblad, V., 2002. Telomere maintenance without telomerase. Oncogene 21 522–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee, A. H., and N. Kleckner, 1997. A general method for identifying recessive diploid-specific mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, its application to the isolation of mutants blocked at intermediate stages of meiotic prophase and characterization of a new gene SAE2. Genetics 146 797–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner, J., and E. A. Medcalf, 1991. Cotranslation of activated mutant p53 with wild type drives the wild-type p53 protein into the mutant conformation. Cell 65 765–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales, M., J. W. Theunissen, C. F. Kim, R. Kitagawa, M. B. Kastan et al., 2005. The Rad50S allele promotes ATM-dependent DNA damage responses and suppresses ATM deficiency: implications for the Mre11 complex as a DNA damage sensor. Genes Dev. 19 3043–3054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau, S., J. R. Ferguson and L. S. Symington, 1999. The nuclease activity of Mre11 is required for meiosis but not for mating type switching, end joining, or telomere maintenance. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19 556–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau, S., E. A. Morgan and L. S. Symington, 2001. Overlapping functions of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mre11, Exo1 and Rad27 nucleases in DNA metabolism. Genetics 159 1423–1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nairz, K., and F. Klein, 1997. mre11S: a yeast mutation that blocks double-strand-break processing and permits nonhomologous synapsis in meiosis. Genes Dev. 11 2272–2290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandita, T. K., 2002. ATM function and telomere stability. Oncogene 21 611–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellicioli, A., S. E. Lee, C. Lucca, M. Foiani and J. E. Haber, 2001. Regulation of Saccharomyces Rad53 checkpoint kinase during adaptation from DNA damage-induced G2/M arrest. Mol. Cell 7 293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penkner, A., Z. Portik-Dobos, L. Tang, R. Schnabel, M. Novatchkova et al., 2007. A conserved function for a Caenorhabditis elegans Com1/Sae2/CtIP protein homolog in meiotic recombination. EMBO J. 26 5071–5082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrini, J. H., and T. H. Stracker, 2003. The cellular response to DNA double-strand breaks: defining the sensors and mediators. Trends Cell Biol. 13 458–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz, S., A. Amon and F. Klein, 1997. Isolation of COM1, a new gene required to complete meiotic double- strand break-induced recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 146 781–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattray, A. J., C. B. McGill, B. K. Shafer and J. N. Strathern, 2001. Fidelity of mitotic double-strand-break repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a role for SAE2/COM1. Genetics 158 109–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, K. B., and T. D. Petes, 2000. The Mre11p/Rad50p/Xrs2p complex and the Tel1p function in a single pathway for telomere maintenance in yeast. Genetics 155 475–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartori, A. A., C. Lukas, J. Coates, M. Mistrik, S. Fu et al., 2007. Human CtIP promotes DNA end resection. Nature 450 509–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shima, H., M. Suzuki and M. Shinohara, 2005. Isolation and characterization of novel xrs2 mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 170 71–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shroff, R., A. Arbel-Eden, D. Pilch, G. Ira, W. M. Bonner et al., 2004. Distribution and dynamics of chromatin modification induced by a defined DNA double-strand break. Curr. Biol. 14 1703–1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stracker, T. H., J. W. Theunissen, M. Morales and J. H. Petrini, 2004. The Mre11 complex and the metabolism of chromosome breaks: the importance of communicating and holding things together. DNA Repair (Amst.) 3 845–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y., Z. Dong, K. Nakamura and N. H. Colburn, 1993. Dosage-dependent dominance over wild-type p53 of a mutant p53 isolated from nasopharyngeal carcinoma. FASEB J. 7 944–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uanschou, C., T. Siwiec, A. Pedrosa-Harand, C. Kerzendorfer, E. Sanchez-Moran et al., 2007. A novel plant gene essential for meiosis is related to the human CtIP and the yeast COM1/SAE2 gene. EMBO J. 26 5061–5070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueguchi, C., T. Suzuki, T. Yoshida, K. Tanaka and T. Mizuno, 1996. Systematic mutational analysis revealing the functional domain organization of Escherichia coli nucleoid protein H-NS. J. Mol. Biol. 263 149–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueguchi, C., C. Seto, T. Suzuki and T. Mizuno, 1997. Clarification of the dimerization domain and its functional significance for the Escherichia coli nucleoid protein H-NS. J. Mol. Biol. 274 145–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usui, T., H. Ogawa and J. H. Petrini, 2001. A DNA damage response pathway controlled by Tel1 and the Mre11 complex. Mol. Cell 7 1255–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usui, T., J. H. Petrini and M. Morales, 2006. Rad50S alleles of the Mre11 complex: questions answered and questions raised. Exp. Cell Res. 312 2694–2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance, J. R., and T. E. Wilson, 2002. Yeast Tdp1 and Rad1-Rad10 function as redundant pathways for repairing Top1 replicative damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99 13669–13674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaze, M. B., A. Pellicioli, S. E. Lee, G. Ira, G. Liberi et al., 2002. Recovery from checkpoint-mediated arrest after repair of a double-strand break requires Srs2 helicase. Mol. Cell 10 373–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P., M. Reed, Y. Wang, G. Mayr, J. E. Stenger et al., 1994. p53 domains: structure, oligomerization, and transformation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14 5182–5191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weil, C. F., and R. Kunze, 2000. Transposition of maize Ac/Ds transposable elements in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat. Genet. 26 187–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, R. M., S. Rimsky and H. Buc, 1996. Probing the structure, function, and interactions of the Escherichia coli H-NS and StpA proteins by using dominant negative derivatives. J. Bacteriol. 178 4335–4343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J., K. Marshall, M. Yamaguchi, J. E. Haber and C. F. Weil, 2004. Microhomology-dependent end joining and repair of transposon-induced DNA hairpins by host factors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24 1351–1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B. B., and S. J. Elledge, 2000. The DNA damage response: putting checkpoints in perspective. Nature 408 433–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]