Abstract

Anticancer vaccine strategies can now target intracellular antigens that are involved in the process of malignant transformation, such as oncogene products or mutated tumor suppressor genes. Fragments of these antigens, generally 8–10 amino acids in length and complexed with MHC class I molecules, can be recognized by CD8+ T lymphocytes (TCD8+). To explore the possibility of using a genetically encoded, minimally sized fragment of an intracellular antigen as an immunogen, we constructed a recombinant vaccinia virus encoding an 8-residue peptide derived from chicken ovalbumin that is known to associate with the mouse H-2Kb molecule. Compared to standard methods of immunization, recombinant vaccinia virus expressing the minimal determinant as well as full length ovalbumin were the only approaches that elicited specific primary lytic responses in C57BL/6 mice against E.G7OVA, a transfectant of the murine thymoma EL4 containing the ovalbumin gene. Stimulating these effectors in vitro with OVA257–264 peptide induced H-2Kb-restricted TCD8+ that not only lysed but also specifically secreted IFN-γ in response to an antigen. Furthermore, when transferred adoptively, these anti-OVA257–264 TCD8+ cells significantly reduced the growth of established ovalbumin-transfected tumors in a pulmonary metastasis model system. Synthetic oligonucleotides encoding minimal antigenic determinants within expression constructs may be a useful approach for treatment of neoplastic disease, thus avoiding the potential hazards of immunizing with full-length cDNAs that are potentially oncogenic.

INTRODUCTION

Elements of the cellular immune system clearly play a role in antitumor immunity (1-3). In particular, TCD8+3 found within the tumor mass has been shown to specifically recognize and eliminate autologous tumor in vitro and in vivo (4-7). Recently, several genes coding for tumor-associated antigens recognized by TCD8+ have been identified and cloned (8-16). Several groups have taken an alternative approach of eliciting TCD8+ that recognize antigens involved in the process of malignant transformation such as oncogenes and mutated tumor suppressor gene products (17-21). These findings allow for the development of improved vaccine strategies targeted at inducing specific TCD8+ responses.

TCD8+ recognize fragments of intracellular proteins in the form of 8–10 amino acid minimal peptides complexed with MHC class I molecules (22, 23). Specific motifs for peptide binding to MHC class I molecules have been demonstrated, and several minimal peptides corresponding to intracellular antigens have been characterized (24, 25). Antigenic proteins cleaved into peptides in the cytosol by the proteolytic activity of the proteosome are generally transported into the ER by a protein heterodimer called TAP (for transporter associated with antigen processing). The peptides then associate with class I α-chain and β2 microglobulin in a trimolecular complex which is then transported to the cell surface for presentation to TCD8+ cells (26).

As the details of antigen processing and presentation have been elucidated, there has been increasing interest in the use of minimal antigenic determinants as immunogens. TCD8+ have been elicited through immunization with minimal antigenic peptides corresponding to both viral and tumor epitopes (27-32). However, little is known about the in vivo significance of these TCD8+ in the treatment of tumors or viral diseases.

In this study, a murine fibrosarcoma (MCA 207) transfected with the gene for chicken ovalbumin was used to test the in vivo antitumor potential of recombinant vaccinia viruses containing the synthetic oligonucleotide encoding a minimal antigenic determinant. Previous studies have reported that TCD8+ against ovalbumin can be raised through immunization with either E.G7OVA tumor (an EL4 murine thymoma clone that expresses ovalbumin), full-length ovalbumin in liposomes, or OVA257–264 peptide with β2 microglobulin as an adjuvant (33-36). TCD8+ recognize an octomer of ovalbumin (amino acid sequence 257–264) presented in the context of murine H-2Kb MHC (37, 38).

Recombinant vaccinia virus produces large quantities of the foreign gene products within the cytoplasm of host cells (39). Immunization with recombinant vaccinia viruses have been shown in murine tumor model systems to prevent (40, 41) and to actively treat (41) murine tumors expressing human tumor antigens. We demonstrate here that the production of minimal peptides by the recombinant vaccinia virus elicited powerful antitumor TCD8+ without an in vitro sensitization step. Furthermore, the antitumor cells display specific therapeutic activity against tumors expressing ovalbumin. Thus, the use of synthetic oligonucleotides encoding minimal antigenic determinants as immunogens may have utility in the treatment of cancer, while avoiding the potential hazards associated with the expression of whole proteins with possible transforming functions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tumors and Animals

EL4, a thymoma cell line of H-2b haplotype, and E.G7OVA tumor, an EL4 cell line transfected with the full-length ovalbumin cDNA, were donated by M. Bevan (University of Washington, Seattle, WA) (33). WP6 (H-2b) is a clone of the MCA 205 fibrosarcoma which was derived by s.c. injection of 3′-MCA into C57BL/6 mice (42). Clone 10 (OVA+) and clone 11 (OVA−) were derived by transfecting a limiting-dilution clone of MCA 207 (another H-2b MCA-induced fibrosarcoma) with the pCDNAIII vector containing the cDNA for ovalbumin kindly provided by K. Rock (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA) (42). The RMA-S cell line was obtained from J. Bennink and J. Yewdell (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH, Bethesda, MD). All tumor cell lines were cultured in CM containing RPMI 1640, 10% heat-inactivated FCS (Biofluids, Rockville, MD), 0.03% fresh glutamine, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 100 units/ml penicillin (all from NIH media unit), and 50 μg/ml gentamicin sulfate (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY). All splenocyte preparations were cultured in CM with 0.1 mm nonessential amino acids, 1.0 mm sodium pyruvate, 5 × 10−5 2-mercaptoethanol (Aldrich Chemical Co., Milwaukee, WI). E.G7OVA and clones 10 and 11 were also maintained in the presence of G418 (400 μg/ml; GIBCO). Female C57B1/6 mice, 8–12 weeks old, were obtained from the Frederick Cancer Research Facility, NIH (Frederick, MD).

Viruses

rVV stocks derived from the WR strain were produced using the thymidine kinase-deficient human osteosarcoma 143/B cell line (ATCC CRL 8303; American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD). A rVV producing the H-2Kb-restricted epitope of the chicken ovalbumin protein (rVV-OVAM257–264) was constructed with the following synthetic double-stranded oligonucleotide (CC ACC ATG TCG ATC ATC AAT TTG GAG AAA CTG TGA TAG GTA CCG) and (GG TGG TAC AGC TAG TAG TTA AAG CTC TTT GAC ACT ATC CAT GGC) into the vaccinia virus genome also using the pSC11 plasmid in a manner described for the other recombinants (43, 44). A rVV containing the full-length cDNA encoding ovalbumin (rVV-OVAFL) was developed by inserting a NotI/SalI fragment from pBSOVA19 (from K. Rock) into NotI/SalI linearized pSC11. A rVV expressing a H-2Db-restricted epitope of influenza A/PR/8/34 (PR8) nucleoprotein (rVV-NPM366–374) was constructed as described previously (44). As an additional control virus, in some cases, a wild-type virus of the WR strain (VV-WT) was utilized. In the viruses producing minimal determinants, synthetic oligonucleotides were generated with Kozak's consensus sequence (CCACC) preceding the ATG initiation codon for efficient translation (45). Oligonucleotides were synthesized on a 392 DNA synthesizer and purified over an oligonucleotide purification cartridge (both from Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Peptides

The synthetic peptide corresponding to residues 257–264 of the ovalbumin protein (SIINFEKL) and 366–374 of the nucleoprotein from PR8 influenza virus (ASNENMETM) were synthesized and HPLC purified (>99%) by Peptide Technologies (Washington DC).

Effector Cells

Primary polyclonal TCD8+ populations were generated from C57BL/6 mice (2 mice/group) by i.v. injection of 5 × 106 PFUs of recombinant vaccinia virus as described (46). For comparison of different methods of immunization, C57BL/6 mice were immunized with a total volume of 100 μl of either 100 μg OVA257–264 peptide emulsified in complete Freund's adjuvant, 100 μg OVA257–264 peptide emulsified in PBS, 2 × 106 irradiated (20,000 cGy) E.G7OVA cells in PBS, or 2 × 106 live E.G7OVA cells mixed in 100 μg Corynebacterium parvum (Burroughs Wellcome, Raleigh, NC), each administered s.c. at the base of the tail. Six days following immunization, splenocytes were dispersed into single cell suspensions and tested directly in a 51Cr release assay.

To assay for secondary in vivo responses, C57BL/6 mice (2 mice/group) were immunized i.v. with 5 × 106 PFUs rVV; 10 days later, they were boosted with the identical dose of the same rVV. Four days later, splenocytes were harvested and tested directly in a 51Cr release assay. Secondary in vitro anti-ovalbumin effector cells were generated by first immunizing C57BL/6 mice with 5 × 106 PFUs of rVV. At least 3 weeks later, spleen cells were dispersed into single cell suspensions and cultured at a final concentration of 3 × 106 splenocytes/ml in T-75 flasks (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) in CM with 1 μg/ml synthetic OVA257–264 peptide. Six days later, splenocytes were washed three times in CM before use in a 51Cr release assay. For adoptive immunotherapy treatments, RBC were lysed with ACK hypotonic lysing buffer (NIH media unit, Bethesda, MD), and the splenocytes were washed extensively with HBSS.

51Cr Release Assays

Six-h 51Cr release assays were performed as described previously (47). Briefly, 2 × 106 tumor targets in 0.3 ml of CM were labeled with 200 μCi Na51CrO4 for 90 min. In some cases, EL4, RMA-S, or clone 11 cells were incubated with 1 μm synthetic peptide OVA257–264 during labeling to load this peptide onto surface-exposed class I H-2Kb molecules. For infection of targets with rVV, WP6 cells were infected for 2 h at 37°C with rVV at 10 PFUs/cell at a final concentration of 107 cells/ml diluted in HBSS containing 0.1% BSA. Target cells were then mixed with effector cells for 6 h at 37°C at the E:T ratio indicated. The amount of 51Cr released was determined by γ counting, and the percentage of specific lysis was calculated as follows:

In antibody-blocking assays, ascites from the anti-H-2Kb hybridoma B8-24-3 and the control, anti-H-2Db mAb 28-14-8, were diluted 1:50 and incubated with targets for 1 h before the addition of effectors. Total lysis of the anti-OVA effector cells against RMA-S cells pulsed with OVA257–264 peptide was 89% and anti-NP effector cells against NP366–374-pulsed RMA-S cells was 48%.

Quantitation of IFN-γ

Microtiter plates were coated overnight at 4°C with 100 ng/well of purified mAb specifically recognizing IFN-γ (PharMingen, San Diego, CA). Ten % FCS in PBS was utilized to prevent nonspecific binding, followed by a 1-h incubation with 100 μl of test supernatants or with a standard curve of 2-fold dilutions of purified IFN-γ (starting at 10,000 pg/ml). After washing with 0.05% Tween 20 in PBS, biotinylated anti-IFN-γ antibody (1 μg/ml; 100 μl/well) was added for 45 min at room temperature, washed three times, and incubated for 30 min with 100 μl of avidin-peroxidase (2.5 μg/ml). 2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenz-thiazolinesulfonic acid) substrate (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) at 300 μg/ml in 0.1 m citric acid (pH 4.35)-0.1% H2O2 was added for 10–80 min, and absorbance was read on a Titertek Multiskan Plus reader (Flow Laboratories, McLean, VA) using a 405-nm filter.

Adoptive Immunotherapy

C57BL/6 mice were irradiated (500 rads) and injected i.v. with 5 × 105 clone 10 (OVA+)- or clone 11 (OVA−)-cultured tumor cells in 0.5 ml of HBSS to induce pulmonary metastases. On day 3, tumor-bearing mice were treated with an i.v. injection of various effector cells at 2 × 107 cells/dose. Specifically, for the generation of effector cells, mice were immunized with 5 × 106 PFUs of either rVV-OVAM257–264, rVV-OVAFL, or rVV-NPM366–374. Three weeks later, splenocytes were harvested and cultured for 6 days with 1 μg/ml of OVA257–264. peptide. Following adoptive transfer of effector lymphocytes, all groups of mice received 90,000 IU of recombinant human IL-2 (Chiron Corp., Emeryville, CA) i.p. twice daily for 3 consecutive days. For these experiments, all mice were ear tagged and randomized. On day 14 after tumor injection, mice were sacrificed and pulmonary metastases were enumerated in a coded, blinded fashion as described previously (48). If pulmonary metastases exceeded 250, they were deemed too numerous to count.

RESULTS

Immunogenicity of rVV Expressing the OVA257–264 Peptide

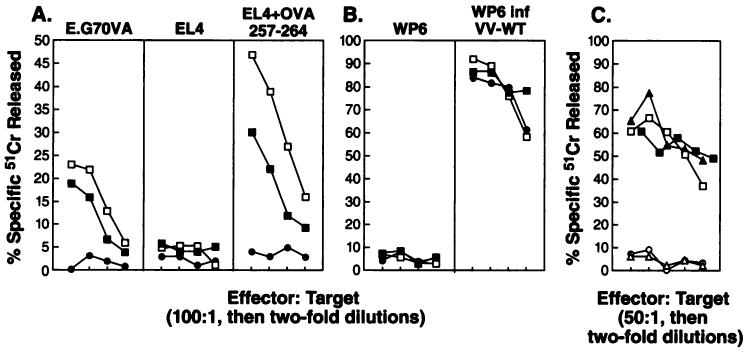

To explore the use of recombinant vaccinia viruses encoding a synthetic oligonucleotide minigene as an immunogen, we constructed a rVV expressing the H-2Kb-restricted epitope of chicken egg ovalbumin preceded by an initiation methionine. Studies were conducted to characterize the ability of the rVV to induce antigen-specific lytic responses. Primary lytic responses of mouse splenocytes primed with rVV-OVAM257–264 were compared to those induced with rVV-OVAFL. C57BL/6 mice were given injections i.v. once with 5 × 106 PFUs of live rVV. Six days later splenocytes were harvested and tested in a 51Cr release assay against the ovalbumin transfectant cell line (E.G7OVA), EL4 (the parental cell line), and EL4 exogenously pulsed with the synthetic peptide OVA257–264. Day 6 has been shown previously to represent the peak of detectable primary anti-vaccinia virus lytic response.4 As shown in Fig. 1A, fresh splenocytes from mice that received rVV-OVAM257–264 and rVV-OVAFL lysed only targets that presented the OVA257–264 peptide, either endogenously by E.G7OVA or exogenously by EL4 pulsed with OVA257–264, yet they failed to lyse EL4 alone. In contrast, there was no background recognition of OVA257–264 by splenocytes elicited through priming with rVV-NPM366–374, a virus shown previously to elicit 6-day primary responses against H-2b tumor cells pulsed with NP366–374 peptide (Ref. 49; data not shown).

Fig. 1.

A, lysis of OVA-expressing tumor by fresh splenocytes from mice immunized with rVV-OVAM257–264. Lytic activity of pooled fresh splenocytes obtained from C57BL/6 mice (2 mice/group) 6 days after i.v. immunization with 5 × 106 PFU of rVV-OVAM257–264 (□), rVV-OVAFL (■), or rVV-NPM366–374 (●) was assayed by a 51Cr release assay using E.G7OVA cells, EL4 cells, or EL4 cells pulsed with OVA257–264 synthetic peptide as targets. B, the same effectors were also tested against WP6 cells and vaccinia-infected WP6 cells. C, secondary anti-OVA257–264 effector cells were generated by immunization with rVV-OVAFL followed by in vitro stimulation of harvested splenocytes for 6 days with OVA257–264 peptide failing to restimulate the anti-vaccinia virus responses. These specific anti-OVA257–264 effector cells were assayed against WP-6 cells infected with rVV-OVAM257–264 (□), WP-6 cells infected with rVV-OVAFL (■), WP-6 cells infected with VV-WT (○), or WP-6 cells pulsed with OVA257–264 peptide (▲) or WP-6 alone (△). All of the experiments were repeated at least twice.

As a control for the efficacy of immunization, anti-vaccinia responses in the 3 groups of immunized mice were determined (Fig. 1B). The splenocytes used in Fig. 1A showed equal lysis of VV-WT-infected WP-6 tumor but did not lyse control WP-6, suggesting that the mice were primed equivalently. Therefore, rVV-OVAM257–264 and rVV-OVAFL induced similar anti-OVA257–264 primary in vivo responses without in vitro stimulation or IL-2 administration.

The ability of the rVV to efficiently infect and produce OVA257–264 peptide was measured using specific anti-OVA257–264 secondary effector cells in an in vitro 51Cr release assay. The secondary effector cells were generated by priming C57B1/6 mice with rVV-OVAFL, followed 3 weeks later by 6 days of an in vitro stimulation step with OVA257–264 peptide, thus failing to restimulate anti-vaccinia viral lytic responses. As shown in Fig. 1C, WP-6 cells infected with rVV-OVAM257–264, WP-6 cells infected with rVV-OVAFL, and WP-6 cells exogenously pulsed with OVA257–264 peptide were all lysed equivalently by the anti-OVA257–264 effectors cells, while WP-6 infected with VV-WT or WP-6 alone were not lysed. Therefore, infection with both rVV-OVAM257–264 and rVV-OVAFL leads to the presentation of the OVA257–264 peptide on the surface of target cells for recognition by TCD8+.

Responses to Ovalbumin following an in Vivo Boost

Studies were undertaken to determine whether the specific primary response to OVA elicited by rVV-OVAM257–264 could be boosted through a second immunization. C57BL/6 mice were immunized i.v. with rVV-OVAM257–264, rVV-OVAFL, or rVV-NPM366–374. Ten days later, mice were boosted with the same dose of rVV. Four days following the boost, fresh splenocytes were assayed by 51Cr release assay. As shown in Table 1, the lytic response against E.G7OVA was enhanced following the boost in comparison to the 6-day primary response assayed in the same experiment. In two experiments, both initial and boosted anti-OVA lytic responses induced by immunization with rVV-OVAM257–264 were greater than those elicited by rVV-OVAFL, but this has not been a consistent finding. Therefore, enhancement of specific lytic responses using rVV-OVAM257–264 and rVV-OVAFL was observed with a repeat immunization.

Table 1.

Enhancement of the activity of fresh splenocytes following boosta

| % specific 51Cr released by splenocytes from mice immunized with rVVb |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target | E:T | OVAM257–264 ×1 |

OVAFL ×1 |

NPM366–374 ×1 |

OVAM257–264 ×2 |

OVAFL ×2 |

NPM366–374 ×2 |

| E.G7OVA | 100:1 | 43 | 14 | 5 | 76 | 22 | 5 |

| 50:1 | 43 | 13 | 6 | 64 | 26 | 5 | |

| 25:1 | 37 | 9 | 4 | 48 | 21 | 6 | |

| 12.5:1 | 20 | 3 | 4 | 31 | 14 | 3 | |

| EL4 | 100:1 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 7 | −3 | −3 |

| 50:1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 | −4 | −1 | |

| 25:1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 4 | −5 | −1 | |

| 12.5:1 | 2 | −1 | 0 | 3 | −3 | −3 | |

C57BL/6 mice were immunized i.v. with 5 × 106 PFU of the rVV indicated either once (×1) 6 days prior to the assay or twice (×2), once 15 days prior to the assay and then boosted 10 days later (5 days prior to the assay) with 5 × 106 PFU of the same rVV. TCD8+ activity of fresh splenocytes was then assayed by a 51Cr release assay with E.G7OVA or EL4. All splenocytes showed specific lysis of VV-WT infected WP6 target cells of >75% at E:T = 50:1 (data not shown).

Values, means of triplicates obtained at E:T ratios indicated.

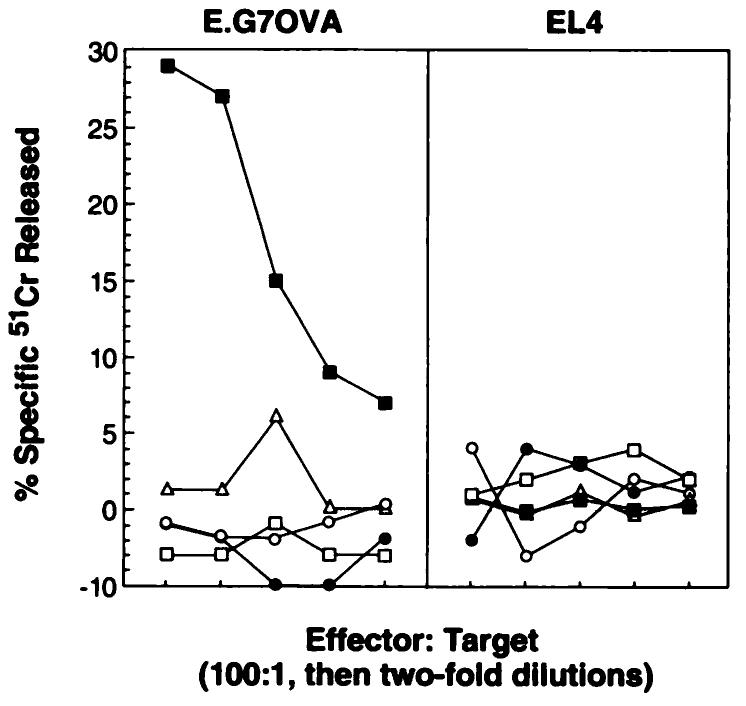

Comparison of rVV to Commonly Used Methods of Immunization

Injection with rVV-OVAM257–264 was compared to commonly utilized methods of peptide and tumor immunization. C57BL/6 mice were given injections with either rVV-OVAM257–264, synthetic OVA257–264 peptide emulsified in CFA, OVA257–264 peptide in PBS, C. parvum with E.G7OVA, or irradiated E.G7OVA cells. These are methods that have been reported previously to reliably induce secondary TCD8+ but not primary cytolytic responses (17-19, 28, 29, 33, 34) in mice. Six days later, splenocytes were obtained and tested in a 51Cr release assay with E.G7OVA or EL4. Fig. 2 shows one representative experiment of three performed in which only fresh splenocytes from mice primed with with rVV-OVAM257–264 demonstrated a specific primary in vivo lytic response against OVA. Fresh splenocytes from mice that received control immunogen, CFA alone, PBS alone, and C. parvum alone failed to lyse E.G7OVA or EL4 (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of rVV-OVAM257–264 to other commonly used methods of immunization. Lytic activity of pooled fresh splenocytes obtained from C57BL/6 mice (2 mice/group) 6 days after either i.v. immunization with rVV-OVAM257–264 (■) or s.c. administration of OVA257–264 peptide emulsified in complete Freund's adjuvant ((□), OVA257–264 peptide in PBS (△), E.G7OVA tumor in C. parvum (●), and irradiated E.G7OVA (○) were tested in a 51Cr release assay against E.G7OVA and EL4. These experiments were repeated twice with the same findings.

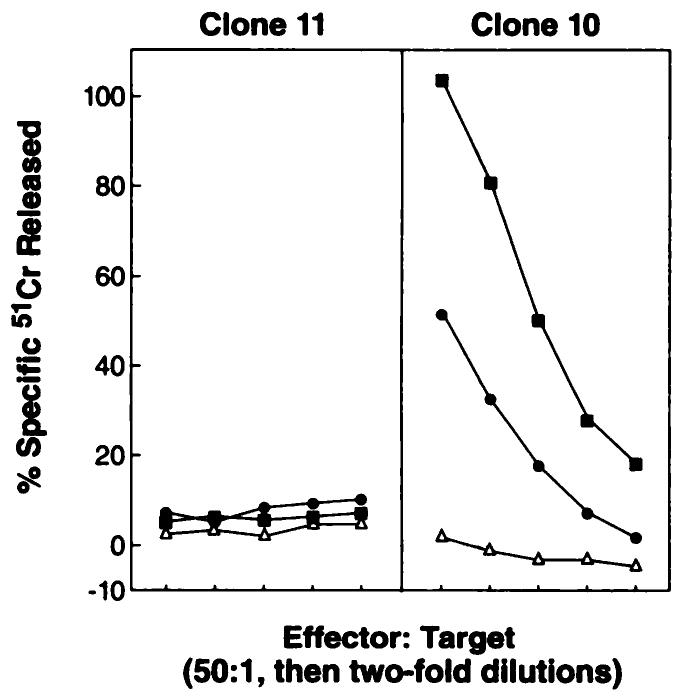

Recognition of MCA 207 Clone 10 (OVA+) by Anti-OVA257–264 Effector Cells

The ability of MCA 207 clone 10 to process and present OVA257–264 was determined using secondary anti-OVA257–264 effector cells generated by immunization with rVV-OVA257–264 or rVV-OVAFL, followed by an in vitro stimulation step with OVA257–264 peptide. Splenocytes from mice immunized with rVV-OVAM257–264, as well as with rVV-OVAFL, both lysed the MCA 207 clone 10(OVA+) but not the MCA 207 clone 11 (OVA−) (Fig. 3). The same effector cells also recognized and lysed clone 11 pulsed with OVA257–264 peptide and E.G7OVA but not EL4 (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Secondary in vitro TCD8+ induced by immunization with rVV-OVAM257–264. C57BL/6 mice were immunized with 5 × 106 PFU of either rVV-OVAM257–264 (■), rVV-OVAFL (●), or rVV-NPM366–374 (△). Three weeks later, pooled splenocytes (2 mice/group) were restimulated in vitro with 1 μg/ml OVA257–264 synthetic peptide for 6 days and then assayed for specific lytic activity in a 51Cr release assay against clone 10 (OVA+) and clone 11 (OVA−) target cells. These experiments have been repeated four times with the same findings.

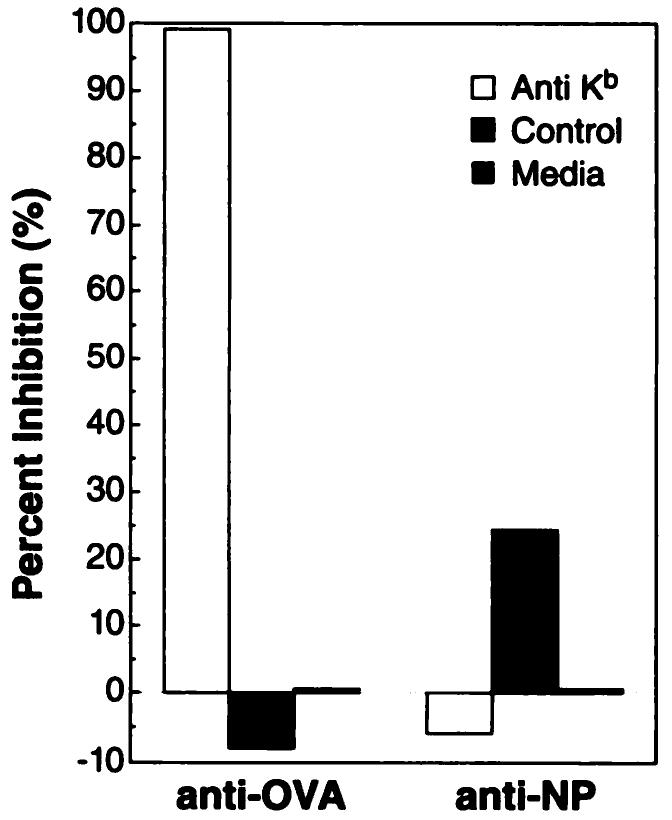

Anti-OVA257–264 TCD8+ Response Elicited by rVV-OVAM257–264 Is H-2Kb Restricted

In order to determine whether the rVV-induced lytic response was directed against OVA257–264 peptide in the context of MHC H-2Kb, a 51Cr release assay was performed with anti-H-2Kb-blocking mAb. The in vitro stimulated anti-OVA257–264 effector cells generated with the use of rVV-OVAM257–264 as immunogen were assayed against 51Cr-labeled RMA-S cells pulsed with OVA257–264 peptide and incubated with or without the anti-H-2Kb mAb. The anti-H-2Kb mAb specifically inhibited the lytic activity between the anti-OVA TCD8+ and the RMA-S cells pulsed with OVA257–264 peptide (Fig. 4). Anti-H-2Kb mAb did not block the interaction between the H-2Db-restricted anti-NP366–374 lytic reaction against RMA-S pulsed with NP366–374 minimal determinant peptide. A control antibody did not interfere with the anti-OVA257–264 TCD8+ lysis of the OVA257–264 pulsed RMA-S cells. The control antibody 28-14-8, an anti-H-2Db MHC mAb and an inefficient blocker of H-2Db/peptide/T-cell receptor interactions, partially inhibited the anti-NP effector lysis of RMA-S cells pulsed with NP366–374 peptide. Together these results support that the rVV-OVAM257–264 elicited a TCD8+ recognition of a peptide complexed with MHC class I H-2Kb.

Fig. 4.

The anti-OVA257–264 lytic response elicited by rVV-OVAM257–264 is presented in the context of H-2Kb. C57BL/6 mice were immunized with 5 × 106 PFU of either rVV-OVAM257–264 or rVV-NPM366–374. Three weeks later, pooled splenocytes (2 mice/group) were stimulated for 6 days in vitro with either OVA257–264 or NP366–374 synthetic peptide, respectively. The anti-OVA257–264 or anti-NP366–374 effector cells were then assayed for lysis of RMA-S cells (H-2Kb) pulsed with either OVA257–264 or NP366–374 peptides in the presence of anti-H-2Kb (B8-24-3), a control mAb ascites, or media alone.

Specific Cytokine Secretion by Effector Cells Induced by rVV-OVAM257–264

In these experiments, effector cells generated by immunization of mice with rVV-OVAM257–264, rVV-OVAFL, and rVV-NPM366–374, followed by an in vitro stimulation for 6 days with OVA257–264 peptide, were tested for the specific secretion of IFN-γ. As shown in Table 2, rVV-OVAM257–264 and rVV-OVAFL anti-OVA effector cells specifically secreted IFN-γ when cocultured with tumor MCA 207 clone 10 (OVA+) (136 and 74 units/ml, respectively) and MCA 207 clone 11 (OVA−) pulsed exogenously with excess OVA257–264 peptide (250 and 277 units/ml, respectively). The same effector cells secreted background levels of IFN-γ when cultured with clone 11 (OVA−) (both 0 units/ml) or without tumor (both 0 units/ml). In addition, control effector cells induced by rVV-NPM366–374 cultured with tumors or wells containing tumor alone demonstrated little to no IFN-γ secretion. Thus, the anti-OVA TCD8+ induced by rVV-OVAM257–264 specifically release IFN-γ in response to antigen processed and presented on the tumor surface.

Table 2.

Specific IFN-γ secretion by effector lymphocytes induced by rVV-ovalbumin constructsa

| IFN-γ secretion (units/ml)b |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immmunogen | Clone 10 (+)c | Clone 11 (−)c | Clone 11c + OVA257–264 |

Nonec |

| rVV-OVAFL | 74 | 0 | 277 | 0 |

| rVV-OVAM257–264 | 136 | 0 | 250 | 0 |

| rVV-NPM366-374 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| No effections | 9 | 6 | 9 | 0 |

C57BL/6 mice were immunized i.v. with 5 × 106 PFU of the recombinant vaccinia viruses. One month later, effector splenocytes were harvested and stimulated for 6 days with OVA257–264 minimal peptide (1 μg/ml). Effector cells were then plated in 24-well plates with tumor targets at 5:1 E:T ratio (2.5 × 106 effector cells: 5 × 105 targets) for 24 h.

Supernatants were harvested and subsequently tested for the presence of IFN-γ by cytokine capture ELISA.

Tumor targets (ovalbumin expression +/−).

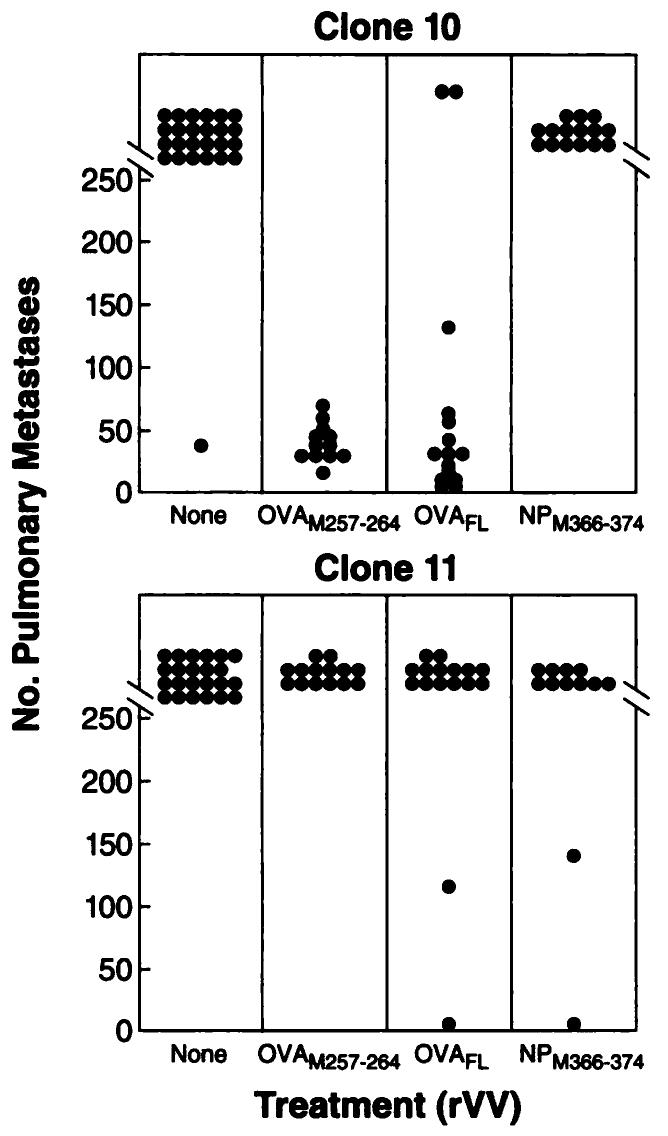

In Vivo Antitumor Activity of Anti-OVA257–264 TCD8+ Generated from rVV-OVAM257–264

To ascertain whether the effector cells induced by immunization with rVV-OVAM257–264 were active in an in vivo adoptive immunotherapy model against clone 10, we used a 3-day lung metastases model (48). In these experiments, C57BL/6 mice were given injections i.v. with either clone 10 (OVA+) or clone 11 (OVA−) tumor cells. On day 3, mice were treated with either IL-2 (90,000 IU) in saline twice daily for 3 days or the same dosage of IL-2 plus TCD8+ from mice that had received rVV-OVAM257–264, rVV-OVAFL, or rVV-NPM366–374. Mice were sacrificed on day 14 when their lungs were harvested and metastases were counted in a blind fashion.

As shown in Fig. 5, TCD8+ generated from mice that were immunized with either rVV-OVAM257–264 or rVV-OVAFL reduced pulmonary metastases from clone 10 (OVA+) tumor. The average number of metastases was significantly reduced from >250/mouse in the groups that received IL-2 alone or IL-2 with anti-NP366–374 effectors to an average of 36.5 ± 14.1 (SD; P < 0.001) and 55.5 ± 71.0 metastases (P < 0.001)/mouse for rVV-OVAM257–264 and rVV-OVAFL TCD8+, respectively. In contrast, the TCD8+ induced by rVV-OVAM257–264 and rVV-OVAFL were not effective at eliminating metastases in mice bearing clone 11 tumor (OVA−; average nodules, >226 ± 67 and >250, respectively), demonstrating in vivo specificity for the ovalbumin antigen. Thus, anti-OVA-specific TCD8+ induced by rVV-OVAM257–264 were therapeutically effective against tumors expressing the model tumor antigen ovalbumin.

Fig. 5.

Adoptive treatment of mice bearing tumors expressing OVA with anti-OVA TCD8+ induced by rVV-OVAM257–264. MCA 207 clone 10 (OVA+), (top) and clone 11 (OVA−), (bottom) were each injected i.v. on day 0 into irradiated mice (500 rads) to create lung metastases. On day 3, mice received one of the effector cell treatments listed. Subsequently, all groups of mice were treated i.p. with 90,000 IU IL-2 twice daily for 3 days. On day 14, the number of pulmonary metastases were enumerated in a coded, blinded fashion. These data represent a summary of two independent experiments each with 6–10 mice/group.

DISCUSSION

In this study, specific antitumor TCD8+ lymphocyte responses were generated with the use of recombinant vaccinia viruses expressing a synthetic oligonucleotide encoding a minimal determinant peptide of only eight amino acids. Immunization specifically directed at a TCD8+ epitope raises the question of the source of TCD4+ help thought to be essential in the recruitment of the cellular immune response. It is possible that the induction of TCD8+ demonstrated in the fresh splenocytes in this study was assisted by nonspecific TCD4+ responses to the vaccinia virus infection. Class II-presented OVA determinants did not appear to be important because there seemed to be no advantage to immunization with rVV expressing the full-length OVA protein versus the minimal determinant in terms of eliciting TCD8+. Alternatively, studies in our laboratory on immunization with peptides preceded by an ER insertion leader sequence have suggested that TCD4+ cells may not be required for the generation of a TCD8+ response (50).

Our results show that a recombinant vaccinia virus vaccine can induce specific lytic TCD8+ in polyclonal populations of fresh splenocytes. Induction of TCD8+ generally requires in vivo immunization followed by in vitro stimulation with antigen and sometimes the presence of exogenous IL-2 (33-36). One other rVV system described also demonstrated that immunization with a rVV expressing a minimal antigenic peptide from the influenza nucleoprotein elicited primary in vivo TCD8+ responses, but these TCD8+ did not protect animals against viral challenge (51).

This paper also indicates that immunization with rVV expressing a minimal peptide as well as a full-length antigen was superior to immunization with the use of several other traditional methods as assessed by the induction of primary TCD8+ cells in fresh splenocytes 6 days after immunization (Fig. 2). This suggests that the intensity of the immunization is enhanced through the delivery of the minimal determinant peptide with vaccinia virus as opposed to immunizing with peptide in combination with other adjuvants. However, it remains to be established whether the enhanced immunogenicity results from increased loading of class I molecules in the ER or to nonspecific help induced by anti-vaccinia virus responses.

The TCD8+ induced by rVV-OVAM257–264 became specifically lytic and secreted IFN-γ in response to cells expressing the minimal determinant epitope. It is not known at this time which effector function is responsible for the observed in vivo antitumor effects. Specific cytokine release (even in nonlytic cells) has been correlated with the induction of antitumor effects in murine tumor systems (52). The release of cytokines such as IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor α, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor by human tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes specifically in response to coculture with autologous tumor has also been reported recently, indicating specific recognition of tumor-associated antigens (53).

It is important to point out that ovalbumin is a foreign antigen in a mouse, and the responses elicited by the ovalbumin constructs may not be the same as those responses induced by a tumor associated or self-antigen epitope. Indeed, issues of tolerance are likely to be critical in the generation of antitumor immune responses, since most tumor associated antigens described thus far are unmutated “self” proteins (8, 9). In addition, recent studies using minimal determinants from the P815 tumor antigen P815A (10) and the nucleoprotein from the influenza virus indicate that different antigens have unpredictable immunogenic characteristics (49, 54).

The use of minimal determinants as immunogens may be particularly advantageous in that peptides are produced rather than full-length proteins that may have potentially dangerous functions when overexpressed, i.e., those that may be involved in malignant transformation (17-21). In addition, this approach allows one to target particular epitopes, thus eliminating the induction of cross-reactive autoimmune responses against other epitopes within that protein. This is particularly advantageous when immunizing against proteins such as the carcinoembryonic antigen that has significant homology to a large number of proteins found on a variety of normal tissues (55).

In summary, we describe a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing a synthetic oligonucleotide encoding a minimal determinant that induces antigen-specific, therapeutic TCD8+ cells. With the identification of minimal peptides derived from tumor-associated antigens (8-13, 15, 16, 51) as well as point-mutated fragments from oncogenes that bind to MHC class I molecules (17-21), approaches utilizing immunization with synthetic oligonucleotides encoding different antigens become feasible. This study provides a model for the development of more effective and specific vaccines for the treatment of cancer.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jon Yewdell and Jack Bennink for critically important ideas and for valuable reagents. We also thank Igor Bacik for the creation of the rVV, Dave Jones for help with animal experiments, Donna Perry-Lalley for helping with the transfections, and Beth Palmer and Judy Stevens for technical assistance.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: TCD8+, CD8+ T lymphocytes; OVA, ovalbumin; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; rVV, recombinant vaccinia viruses; PFU, plaque-forming unit; MCA, methylcholanthrene; CM, complete medium; IL-2, interleukin 2; NP, nucleoprotein.

N. P. Restifo, unpublished data.

REFERENCES

- 1.Prehn RT, Main JM. Immunity to methylcholanthrene-induced sarcomas. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1957;18:769–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein G, Sjögren HO, Klein E, Hellström KE. Demonstration of resistance against methylcholanthrene-induced sarcomas in the primary autochthonous host. Cancer Res. 1960;20:1561–1572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenberg PD, Cheever MA, Fefer A. H-2 restriction of adoptive immunotherapy of advanced tumors. J. Immunol. 1981;126:2100–2103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Itoh K, Platsoucas DC, Balch CM. Autologous tumor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in the infiltrate of human metastatic melanomas: activation by interleukin 2 and autologous tumor cells and involvement of the T cell receptor. J. Exp. Med. 1988;168:1419–1441. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.4.1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muul LM, Spiess PJ, Director EP, Rosenberg SA. Identification of specific cytolytic immune responses against autologous tumor in humans bearing malignant melanoma. J. Immunol. 1987;138:989–995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenberg PD. Adoptive T cell therapy of tumors: mechanisms operative in the recognition and elimination of tumor cells. Adv. Immunol. 1991;49:281–355. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60778-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenberg SA, Packard BS, Aebersold PM, Solomon D, Topalian SL, Toy ST, Simon P, Lotze MT, Yang JC, Seipp CA, Simpson C, Carter C, Bock S, Schwartzentruber D, Wei JP, White DE. Use of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes and interleukin-2 in the immunotherapy of patients with metastatic melanoma. Preliminary report. N. Engl. J. Med. 1988;319:1676–1680. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198812223192527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pardoll DM. Tumour antigens. A new look for the 1990s. Nature (Lond.) 1994;369:357–359. doi: 10.1038/369357a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Houghton AN. Cancer antigens: immune recognition of self and altered self. J. Exp. Med. 1994;180:1–4. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van den Eynde B, Lethe B, Van Pel A, De Plaen E, Boon T. The gene coding for a major tumor rejection antigen of tumor P815 is identical to the normal gene of syngeneic DBA/2 mice. J. Exp. Med. 1991;173:1373–1384. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.6.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van der Bruggen P, Traversari C, Chomez P, Lurquin C, De Plaen E, Van den Eynde B, Knuth A, Boon T. A gene encoding an antigen recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes on a human melanoma. Science (Washington DC) 1991;254:1643–1647. doi: 10.1126/science.1840703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brichard V, Van Pel A, Wolfel T, Wolfel C, De Plaen E, Lethe B, Coulie P, Boon T. The tyrosinase gene codes for an antigen recognized by autologous cytolytic T lymphocytes on HLA-A2 melanomas. J. Exp. Med. 1993;178:489–495. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.2.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawakami Y, Eliyahu S, Delgado CH, Robbins PF, Rivoltini L, Topalian SL, Miki T, Rosenberg SA. Cloning of the gene coding for a shared human melanoma antigen recognized by autologous T cells infiltrating into tumor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:3515–3519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawakami Y, Eliyahu S, Delgado SH, Robbins PF, Sakaguchi K, Appella E, Yannelli JR, Adema GJ, Miki T, Rosenberg SA. Identification of a human melanoma antigen recognized by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes associated with in vivo tumor rejection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:6458–6462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robbins PF, El-Gamil M, Kawakami Y, Rosenberg SA. Recognition of tyrosinase by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes from a patient responding to immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3124–3126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cox AL, Skipper J, Chen Y, Henderson RA, Darrow TL, Shabanowitz J, Engelhard VH, Hunt DF, Slingluff CL., Jr. Identification of a peptide recognized by five melanoma-specific human cytotoxic T cell lines. Science (Washington DC) 1994;264:716–719. doi: 10.1126/science.7513441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Disis ML, Smith JW, Murphy AE, Chen W, Cheever MA. In vitro generation of human cytolytic T-cells specific for peptides derived from the HER-2/neu protooncogene protein. Cancer Res. 1994;54:1071–1076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peace DJ, Smith JW, Chen W, You SG, Cosand WL, Blake J, Cheever MA. Lysis of ras oncogene-transformed cells by specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes elicited by primary in vitro immunization with mutated ras peptide. J. Exp. Med. 1994;179:473–479. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Houbiers JG, Nijman HW, van der Burg SH, Drijfhout JW, Kenemans P, van de Velde CJ, Brand A, Momburg F, Kast WM, Melief CJ. In vitro induction of human cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses against peptides of mutant and wild-type p53. Eur. J. Immunol. 1993;23:2072–2077. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melief CJ, Kast WM. Potential immunogenicity of oncogene and tumor suppressor gene products. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1993;5:709–713. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(93)90125-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jung S, Schluesener HJ. Human T lymphocytes recognize a peptide of single point-mutated, oncogenic ras proteins. J. Exp. Med. 1991;173:273–276. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.1.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Townsend AM, Rothbard J, Gotch FM, Bahdur G, Wraith D, McMichael AJ. The epitopes of influenza nucleoprotein recognized by cytotoxic T lymphocytes can be defined with short synthetic peptides. Cell. 1986;44:959–968. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Townsend A, Bodmer H. Antigen recognition of class I restricted T lymphocytes. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1989;7:601–624. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.003125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Falk K, Rötzschke O, Stevanovic S, Jung G, Rammensee H-G. Allele-specific motifs revealed by sequencing of self-peptides eluted from MHC molecules. Nature (Lond.) 1991;351:290–296. doi: 10.1038/351290a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Falk K, Rötzschke O, Deres K, Metzger J, Jung G, Rammensee H-G. Identification of naturally processed viral nonapeptides allows their quantification in infected cells and suggests an allele-specific T cell epitope forecast. J. Exp. Med. 1991;174:425–434. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.2.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yewdell JW, Bennink JR. Cell biology of antigen processing and presentation to major histocompatibility complex class I molecule-restricted T lymphocytes. Adv. Immunol. 1992;52:1–123. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60875-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deres K, Schild H, Wiesmüller K-H, Jung G, Rammensee H-G. In vivo priming of virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes with synthetic lipopeptide vaccine. Nature (Lond.) 1989;342:561–564. doi: 10.1038/342561a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romero P, Eberl G, Casanova JL, Cordey AS, Widmann C, Luescher IF, Corradin G, Maryanski JL. Immunization with synthetic peptides containing a defined malaria epitope induces a highly diverse cytotoxic T lymphocyte response. Evidence that two peptide residues are buried in the MHC molecule. J. Immunol. 1992;148:1871–1878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schulz M, Zinkernagel RM, Hengartner H. Peptide-induced antiviral protection by cytotoxic T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:991–993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.3.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skipper J, Stauss HJ. Identification of two cytotoxic T lymphocyte-recognized epitopes in the ras protein. J. Exp. Med. 1993;177:1493–1498. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.5.1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schild H, Norda M, Deres K, Falk K, Rötzschke O, Wiesmuller KH, Jung G, Rammensee HG. Fine specificity of cytotoxic T lymphocytes primed in vivo either with virus or synthetic lipopeptide vaccine or primed in vitro with peptide. J. Exp. Med. 1991;174:1665–1668. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.6.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berzofsky JA. Epitope selection and design of synthetic vaccines. Molecular approaches to enhancing immunogenicity and cross-reactivity of engineered vaccines. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1993;690:256–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb44014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore MW, Carbone FR, Bevan MJ. Introduction of soluble protein into the class I pathway of antigen processing and presentation. Cell. 1988;54:777–785. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)91043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lipford GB, Hoffman M, Wagner H, Heeg K. Primary in vivo responses to ovalbumin. Probing the predictive value of the Kb binding motif. J. Immunol. 1993;150:1212–1222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reddy R, Zhou F, Nair S, Huang L, Rouse BT. In vivo cytotoxic T lymphocyte induction with soluble proteins administered in liposomes. J. Immunol. 1992;148:1585–1589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou F, Rouse BT, Huang L. Prolonged survival of thymoma-bearing mice after vaccination with a soluble protein antigen entrapped in liposomes: a model study. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6287–6291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rotzschke O, Falk K, Stevanovic S, Jung G, Walden P, Rammensee HG. Exact prediction of a natural T cell epitope. Eur. J. Immunol. 1991;21:2891–2894. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830211136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shastri N, Gonzalez F. Endogenous generation and presentation of the ovalbumin peptide/Kb complex to T cells. J. Immunol. 1993;150:2724–2736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moss B. Vaccinia virus: a tool for research and vaccine development. Science (Washington DC) 1991;252:1662–1667. doi: 10.1126/science.2047875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Estin CD, Stevenson US, Plowman GD, Hu SL, Sriddar P, Hellstrom I, Brown JP, Hellstrom KE. Recombinant vaccinia virus vaccine against human melanoma antigen p97 for use in immunotherapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:1052–1056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.4.1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kantor J, Irvine K, Abrams S, Kaufman H, DiPietro J, Schlom J. Anti-tumor activity and immune responses induced by a recombinant carcinoembryonic antigen-vaccinia virus vaccine. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1992;84:1084–1091. doi: 10.1093/jnci/84.14.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Restifo NP, Esquivel F, Asher AL, Stötter H, Barth RJ, Bennink JR, Mulé JJ, Yewdell JW, Rosenberg SA. Defective presentation of endogenous antigens by a murine sarcoma: implications for the failure of an anti-tumor immune response. J. Immunol. 1991;147:1453–1459. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Michalek MT, Grant EP, Gramm C, Goldberg AL, Rock KL. A role for the ubiquitin-dependent proteolytic pathway in MHC class I-restricted antigen presentation. Nature (Lond.) 1993;363:552–554. doi: 10.1038/363552a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eisenlohr LC, Bacik I, Bennink JR, Bernstein K, Yewdell JW. Expression of a membrane protease enhances presentation of endogenous antigens to MHC class I-restricted T lymphocytes. Cell. 1992;71:963–972. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90392-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kozak M. Structural features in eukaryotic mRNAs that modulate the initiation of translation. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:19867–19870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bennink JR, Yewdell JW. Recombinant vaccinia viruses as vectors for studying T lymphocyte specificity and function. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 1990;163:153–184. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-75605-4_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barth RJ, Bock SN, Mule JJ, Rosenberg SA. Unique murine tumor associated antigens identified by tumor infiltrating lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 1990;144:1531–1537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mule JJ, Yang JC, Lafreniere R, Shu S, Rosenberg SA. Identification of cellular mechanisms operational in vivo during the regression of established pulmonary metastases by the systemic administration of high-dose recombinant interleukin-2. J. Immunol. 1987;139:285–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Restifo NP, Bacik I, Irvine KR, Yewdell JW, McCabe BJ, Anderson RW, Eisenlohr LC, Rosenberg SA, Bennink JR. Antigen processing in vivo and the elicitation of primary cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses. J. Immunol. 1995 in press. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Minev BR, McFarland BJ, Spiess PJ, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Insertion signal sequence fused to minimal peptides elicits specific CD8+ T-cell responses and prolongs survival of thymoma-bearing mice. Cancer Res. 1994;54:4155–4164. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lawson CM, Bennink JR, Restifo NP, Yewdell JW, Murphy BR. Primary pulmonary cytotoxic T lymphocytes induced by immunization with a vaccinia virus recombinant expressing influenza A virus nucleoprotein peptide do not protect mice against challenge. J. Virol. 1994;68:3505–3511. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.6.3505-3511.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barth RJ, Mule JJ, Spiess PJ, Rosenberg SA. Interferon γ and tumor necrosis factor have a role in tumor regressions mediated by murine CD8+ tumor infiltrating lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1991;173:647–658. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.3.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schwartzentruber DJ, Topalian SL, Mancini MJ, Rosenberg SA. Specific release of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, tumor necrosis factor-α, and IFN-γ by human tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes after autologous tumor stimulation. J. Immunol. 1991;146:3674–3681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Irvine KR, McCabe BJ, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Synthetic oligonucleotide expressed by a recombinant vaccinia virus elicits therapeutic cytolytic T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 1995 in press. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shively J, Beatty J. CEA-related antigens: molecular biology and significance. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 1985;2:355–399. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(85)80008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]