Abstract

The growth of a poorly immunogenic methylcholanthrene (MCA)-induced murine (m) sarcoma genetically engineered to secrete human (h) TNF-α (MCA-102-hTNF) was studied. MCA-102-hTNF tumor cells were implanted in animals bearing three- or 7-day pulmonary metastases established with the parental line MCA-102-WT (wild type). This model approximates the clinical situation in which patients with metastatic cancer would be vaccinated with autologous tumor genetically modified to stimulate the host immune response. Reduction in the number of pulmonary metastases was occasionally seen but was not consistently reproducible. Other cytokine-producing tumors had either no effect on distant pulmonary metastases (mIL-4, IFN-γ) or a mild, inconclusive effect similar to hTNF-α (mTNF-α). Significant growth inhibition of MCA-102-hTNF was noted in animals bearing pulmonary metastases. This inhibition was: 1) tumor specific (regression occurred only in animals bearing pulmonary metastases from the same parental line), 2) TNF specific (it was inhibited by in vivo administration of anti hTNF mAbs), 3) dependent on cellular immunity (immune-depletion with anti-CD4 or CD8 mAbs permitted growth). Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) could not be grown from MCA-102-WT or MCA-102-hTNF tumors nor from MCA-102-WT subcutaneous implants in mice bearing MCA-102-WT pulmonary metastases. However, TIL could be grown from hTNF-secreting tumors implanted in mice bearing MCA-102-WT metastases. These TIL were therapeutic against established lung metastases from the parental tumor in adoptive immunotherapy models. These studies suggest a strategy for using gene modified tumors for the therapy of established cancer.

The TNF-α is a cytokine with multiple effects (summarized in Ref. 1) that includes direct antitumor activity in mice in vivo (1), limited by the severe toxicity accompanying effective doses (2). Furthermore, TNF-α can induce T cell proliferation (3) and stimulation of CTL activity (4) while secretion of TNF-α by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL)2 has been correlated with in vivo therapeutic efficacy (5).

Because of the limited clinical usefulness of TNF-α due to its severe toxicity, novel strategies have been considered aimed at exploiting the antitumor potential of this cytokine bypassing the systemic toxicity. TIL have been genetically modified to produce TNF with the intent of delivering high doses of the cytokine at the tumor site (6); tumors have been genetically adapted to produce TNF with the intent of making them more immunogenic (7, 8).

The methylcholanthrene (MCA)-induced murine sarcoma lines MCA-102 and MCA 205 have been shown previously to be very poorly immunogenic (MCA-102) or weakly immunogenic (MCA-205), respectively, when injected into syngeneic C57BL/6 mice (9). Insertion of the hTNF-α gene into the weakly immunogenic MCA-205 line (denoted MCA-205-hTNF) results in spontaneous regression of the tumor when it is injected into syngeneic C57BL/6 mice (7). This regression is dependent on the amount of hTNF secreted (10) and is T cell mediated (6). After regression of MCA-205-hTNF tumor, animals become immune to a challenge with the same tumor as well as to the parental, nongene-modified MCA-205-WT. In contrast, when the poorly-immunogenic MCA-102-hTNF line is tested in the same model, no tumor regression is seen (11).

With the purpose of establishing a model closer to the clinical situation, we decided to test the growth in vivo of MCA-205-hTNF and MCA-102-hTNF (secondary tumors) in animals already bearing tumors established with the parental nongene-modified line (MCA-205-WT or MCA-102-WT) (primary tumors). This model approximates the hypothetical clinical situation in which patients with advanced metastatic cancer would be vaccinated with an autologous cancer cell line genetically modified to stimulate the host immune response.

Two therapeutic strategies were addressed with this model by evaluating: 1) the effect of the secondary hTNF-α producing tumor on the growth of the primary tumors and 2) by assessing the ability to isolate tumor-reactive lymphocytes from hTNF-α-producing tumors in a classic concomitant immunity setting (12).

Materials and Methods

Animals

Female C57BL/6 mice (B6), 10- to 14-wk-old, were obtained from the Animal Production Colonies, Frederick Cancer Research Facility, National Institutes of Health (NIH), Frederick, MD. For adoptive immunotherapy studies animals received 450 rads of total body irradiation before establishment of tumor implants.

Tumor lines

The poorly immunogenic MCA-102 and the weakly immunogenic MCA-205 sarcomas, syngeneic to B6 mice, were generated in our laboratories by i.m. injection of 0.1 ml of 0.1% MCA in sesame seed oil as described previously (13) and maintained in vivo by serial passage. A clonal population from both original tumors was then established by limiting dilution at 0.3 cells/well concentration in 96-well flat bottom tissue culture plates (Costar, Cambridge, MA). Both clones (referred to in this paper, respectively, as MCA-102-WT and MCA-205-WT) were maintained as a monolayer culture in complete medium (CM) containing RPMI 1640 (Biofluids, Rockville, MD), 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids (Biofluids), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Biofluids), 5 × 105 M 2-ME (Aldrich Chemical Co., Milwaukee, WI), 0.03% glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin (both from NIH media unit), 0.5 μg/ml amphotericin B (Flow Laboratories, McLean, VA) and 10% heat-inactivated FCS (Biofluids). Gene-modified subclones were obtained from these clones as described in the following section.

Gene transfer

Gene transfer was conducted by microinjection or transduction in the presence of polybrene (8 mg/ml) for 8 h at 37°C or by calcium phosphate transfection. The retroviral vector contained the NeoR gene under transcriptional control of the SV-40 early region promoter and enhancer (14) plus a cytokine cDNA or genomic DNA as described for each cell line. Transductions and transfections were also performed using the retroviral vector without the cytokine gene to prepare neomycin-resistant subclones as controls. The transduced cells were selected for NeoR gene expression by exposure to the neomycin analogue G418 (GIBCO BRL, Grand Island, NY) at a concentration of 500 to 600 mg/ml for 12 to 15 days beginning 2 days after transduction or transfection. G418-resistant cells were sub-cloned by limiting dilution to subselect a clone with high or low expression of a specific cytokine. Table I gives a summary of the gene modified tumor cell lines used and the range of production of each cytokine at the time of the experiments. The following cytokine genes were used: h and mTNF-α and mIFN-γ cDNA under the transcriptional control of LTR from the Molony murine leukemia virus were transduced using the NeoR gene as previously described (3, 15). As a control, an identical linearized plasmid was used but without cytokine cDNA, this was called LXSN. Murine genomic DNA was used for IL-4 transfection, using a modified construct of pLT-IL-4 kindly supplied by Dr. R. Tepper (Harvard University, Boston). This is a fusion gene that, when expressed in nonsyngeneic murine tumors, can cause their rejection in nude mice (16). This plasmid was inserted into pBJ-1 vector (17) containing the NeoR gene. This plasmid was called EM-IL-4. With these genes, the following clones were selected to be used for this study (Table I): MCA-102-hTNF (expressing high amounts of hTNF-α), MCA-102-hTNF.4 and MCA-102-hTNF.25 (expressing low amounts of hTNF-α), MCA-102-mTNF (expressing low amounts of mTNF-α), MCA-102-mTNF.15 (expressing high amounts of mTNF-α) MCA-102-mIFN (expressing mIFN-γ), MCA-102-mIL4 (expressing mIL-4), MCA-102-NeoR (carrying only the neomycin-resistance gene), MCA-205-hTNF (expressing hTNF-α) and MCA-205-NeoR (carrying only the neomycin-resistance gene).

Table I.

List of secondary tumors used and respective cytokine production

| Gene Producta |

Cell Line |

Amount of Cytokine Secreted (per 1.106 cells/ml/24 h) |

Method of DNA Transfer | Name of Vector |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hTNF-α | 102-TNF | 12–20 ng | Microinjection | LTSN |

| hTNF-α | 102-TNF.4a | 1.5 ng | Microinjection | LTSN |

| hTNF-α | 102-TNF.25a | 0.5 ng | Microinjection | LTSN |

| hTNF-α | 205-TNF | 4–5 ng | Transduction | LTSN |

| mTNF-α | 102-mTNF | 1–2 ng | Transfection | LmTSN |

| mTNF-α | 102-mTNF.15b | 10–20 ng | Transfection | LmTSN |

| mIFN-γ | 102-IFN | 5 ng | Transduction | LIfnSN |

| mIL-4 | 102-IL4 | 1–2 ng | Transfection | EM.IL-4 |

| Neo | 102-NeoR | 0 ngc | Transfection | LXSN |

| Neo | 205-NeoR | 0 ng | Transductjon | LXSN |

Gene product refers to the cytokine produced plus a neomycin-resistance gene (NeoR). “h” refers to human, and “m” to murine origin of the DNA fragment.

Subclone of MCA-102-hTNF producing low amounts of hTNF.

Subclone of MCA-102-mTNF producing higher amounts of mTNF.

At the beginning of the experiment, each sarcoma line was expanded in vitro under the appropriate selection conditions for four to six passages and then, after being tested for cytokine release (when applicable), frozen in aliquots of 5 × 106 cells/vial at − 120°C. For each experiment, a new vial was thawed from the freezer and expanded in vitro for a maximum of three passages before being used in vivo to keep culture passage as consistent as possible throughout the experiment.

Concomitant immunity model

Establishment of pulmonary metastases

C57BL/6 female mice were given 106 MCA-102-WT or MCA-205-WT tumor cells administered by tail vein injection to establish pulmonary metastases.

Establishment of s.c. tumors

Three to seven days after establishment of pulmonary metastases 5 to 10 × 106 gene-modified tumor cells or their respective controls were injected s.c. in the flank. Criss-cross experiments between MCA-102 and MCA-205 lineage were done, injecting as a primary tumor a parental line different from the secondary tumor producing the cytokine; in this fashion the effect of specific immunity rather than a general effect due to the secretion of the cytokine could be tested. The subcutaneous tumor measurements were done weekly and quantitated as the product of two perpendicular measurements (tumor area). Animals were killed 21 to 28 days after the injection of the secondary tumors for enumeration of pulmonary metastases in a coded blinded fashion.

In vivo administration of anti-hTNF Ab

A murine mAb, TNF-E, which blocks the activity of hTNF-α was kindly provided by Dr. Brian Fendly (Genentech Corporation, San Francisco, CA). One hundred milligrams of TNF-E were injected i.p. every 3 to 4 days into mice bearing hTNF-α-modified tumors. The ability of this mAb to effectively block the activity of hTNF-α in vitro and in vivo has been described (3). An isotype-matched murine mAb (Genentech, Palo Alto, CA), which was raised to hamster tissue plasminogen activator was used as a negative control.

In vivo depletion of T cell subsets

Two hybridomas producing rat IgG2b mAbs against the CD4 (GK1.5) and the CD8 (2.43) T cell Ag were obtained from the American Type Tissue Collection (Rockville, MD). The 2.43 mAb was harvested as ascites from pristane nu/nu mice. The GK1.5 mAb was prepared from concentrated culture supernatants using ammonium sulfate. For in vivo depletion, each mouse received weekly i.v. injections of 1 ml diluted mAb, in which 0.0125 ml of 2.43 monoclonal ascitic fluid or 300 mg of GK1.5 mAb was mixed with HBSS. This procedure previously has been shown to be effective in producing long-term (7 to 10 days) depletion of T cell sub populations in vivo (9, 18).

Generation of splenocytes

Spleens were removed aseptically and crushed with the hub of a syringe in CM. The cell suspension was passed through 100-gauge nylon mesh and the erythrocytes were lysed by hypotonic shock with buffered ammonium chloride solution at room temperature for 2 min. The cells were then centrifuged and washed twice in CM.

Generation of TIL

TIL were generated as previously described (19,20). Seven days after i.v. injection of MCA-102-WT, 107 cells from MCA-102-hTNF, or MCA-102-WT, or MCA-102-NeoR were injected s.c.; as a further control, attempts were made to generate TIL from MCA-102-hTNF in nontumor-bearing animals. Seven days after the s.c. injection, before regression of the MCA-102-hTNF tumors in MCA-102-WT-bearing animals, the mice were killed and the subcutaneous tumors were minced and digested with constant stirring in 50 ml of HBSS containing 4 mg of DNase, 40 mg of collagenase and 100 U of hyaluronidase (Sigma, St Louis, MO) for 2 h at room temperature. The digested product was filtered through a double Nytex mesh, washed three times, and then resuspended in ice-cold HBSS. TIL were then immnunoselected using anti-Thy 1.2 mAb-coated magnetic beads as previously described (19) and plated at a concentration of 2 × 105 cells/ml in a 24-well plate in 2 ml of CM containing 10 U/ml of IL-2. On the following day, TIL were stimulated with irradiated (40,000 rads) MCA-102-WT tumor cell lines and irradiated lymphocytes (3000 rads) at a concentration of 3 × 105 cells/well. Medium containing fresh IL-2 was replaced every 3 days, stimulation with autologous tumor and splenocytes was repeated every 10 days. Cells were split, counted, and replated at a concentration of 4 × 105 cells/well when they reached approximately 70% confluence. Tumors from three donor mice were used to generate TIL from MCA-102-hTNF due to the small size of these regressing tumors.

Generation of LAK cells

LAK cells were generated by placing 5 × 106 normal splenocytes into 175-cm2 (750-ml) flasks (Falcon Plastics, Oxnard, CA) in 100 ml of CM with 1000 U/ml of RIL-2 (21) and incubated in standard culture conditions. The LAK cells were then harvested into sterile 250-ml centrifuge tubes (Corning Glass Works, Corning, NY), and washed three times in HBSS before suspending them either in HBSS for i.v. injection or in CM for cytotoxicity testing.

Adoptive immunotherapy using TIL

To establish pulmonary metastases, irradiated animals (450 rads) received 1 × 106 cancer cells i.v. Three days after establishment of pulmonary metastases, animals received TIL grown from MCA-102-hTNF followed by 10,000 U of RIL-2 i.v. every 8 h for 3 days. Controls consisted of animals receiving either RIL-2 alone at the same dose or HBSS. In two experiments, extra groups of animals bearing MCA-102-WT metastases were treated with the i.v. injection of 107 LAK cells. After 2 wk from the adoptive transfer of TIL, the animals were killed and metastases counted in a blinded fashion.

51Cr release assay

Effector cells were prepared by harvesting TIL cultures and LAK cells, resuspending them in CM, and plating at E:T ratio of 50:1, 10:1, 2:1, and 0.4:1 in 96-well U-bottomed plates (Costar). Fresh tumor targets were added after triple enzyme digestion of s.c. tumors as described above. Erythrocytes were lysed with buffered ammonium chloride-potassium, tumor cells were washed twice, and suspended in CM at 107 cells/ml. Three hundred mCu of 51Cr were added per milliliter of target/cell suspension; the mixture was incubated for 2 h at 37°C then washed three times in HBSS, suspended in CM, and 104 cells were added to each well. Targets and effectors were centrifuged at 500 rpm for 5 min, then incubated for 4 h at 37°C. The supernatant samples were harvested by using the Skatron apparatus (Skatron, Sterling, VA) and were counted in a gamma counter. The percentage of lysis was calculated as follows: (experimental cpm − spontaneous cpm) / (maximal cpm − spontaneous cpm) × 100.

Cytokine assays

All cytokine assays were performed testing supernatants after 24 h of culture. Cells were cocultured at a concentration of one million cells in 2 ml of CM in 24-well plates (Costar). hTNF-α concentration were tested using a quantitative ELISA (R&D, Minneapolis, MN), mTNF-α, mGM-CSF and mIL-4 were tested by using the respective murine ELISA kit (Endogen, Boston, MA). hIFN-γ was tested with Centecor Gamma Interferon RIA (Centecor Inc., Malvern, PA). mIFN- was tested with ELISA test kit from GIBCO BRL (Gaithersburg, MD).

Flow cytometric analysis

To examine MHC protein expression by TNF producing tumors (205-TNF and 102-TNF), tumor cells were tested by flow cytometry on a FACScan 440 (Becton Dickinson). Cultured tumor cell lines were harvested with 0.02% EDTA, washed, and stained for 45 min with culture supernatant from the appropriate mAb. For recognition of class I expression an anti-H-2 KkDk mAb (ATCC HB50) IgG2ak (22) was used or the appropriate isotype-matched control Ab (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) followed by the addition of goat anti-mouse IgG2a FITC-conjugated Ab. For recognition of class II expression, direct staining was obtained by using mouse anti-I FITC-conjugated mAb. Nonviable cells were gated with propidium iodide. Depletion of lymphocyte subsets in mice was assessed by preparing fresh splenocytes 7 days after i.v. injection of the respective Ab and tested by flow cytometry using commercially available FITC-conjugated anti-mouse Ly-2 and L3T4 Abs (PharMingen, San Diego, CA).

Histology

The subcutaneous tumors were harvested 10 days after implantation at a time (when they start to regress) that was arbitrarily chosen for tumor harvest with the intent of growing TIL. Tissues were dipped in OCT compound (Tissue-Teck, Elkhart, IN) and frozen in 2-methybutane (J.T. Baker, Phillisburg, N.J.). Eight-micron sections were then fixed in acetone and stained with standard hematoxylin & eosin. Interpretation was done blindly by a pathologist by scoring lymphocytic infiltration arbitrarily from 0 to 4.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses of in vivo experiments were performed by the Wilcoxon rank sum test for comparison of number of pulmonary metastases and the Student's t-test for the size of subcutaneous tumors. Histologic analysis of lymphocytic infiltrate was analyzed between two experimental groups at the time using the normalized Kruskal-Wallis test. Two sided p values are presented in all experiments. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Results

Effect of the presence of subcutaneous cytokine-secreting tumors on the number of established pulmonary metastases or established subcutaneous implants

Sixteen experiments (6 to 10 animals per group in each experiment) were performed in which mice bearing 7-day MCA-102-WT pulmonary metastases were treated by a single s.c. injection of 5 to 10 × 106MCA-102-hTNF tumor cells, and the number of lung metastases was evaluated 21 to 28 days later. In six experiments, the injected MCA-102-hTNF significantly decreased the number of MCA-102-WT pulmonary metastases, and in the remaining experiments no impact was seen (data not shown). Similar experiments using animals with 3-day-old pulmonary implants from MCA-102-WT were also inconclusive. Treatment with other cytokine-producing tumors was even more negligible with no impact on the number of pulmonary metastases (these experiments included use of mTNF, mIL4, and mIFN-γ). In four experiments, the effect of the presence of cytokine-producing MCA-205 tumors on MCA-205-WT was tested again, yielding inconclusive results (data not shown). We concluded that the cytokine-secreting tumors tested in the experiments do not exert a therapeutic effect against established pulmonary metastases in this model model. Similarly, MCA-102-hTNF tumor implants had no effect on 3- or 7-day-old distant subcutaneous implants from MCA-102-WT in four consecutive experiments with six animals in each group. Finally, when a combination of hTNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-2-secreting tumors were implanted together in equal amounts (5 × 106 each), no additional benefit was noted either on the number of distant pulmonary metastases or the subcutaneous growth of these mixed tumor implants. Data not shown but available upon request.

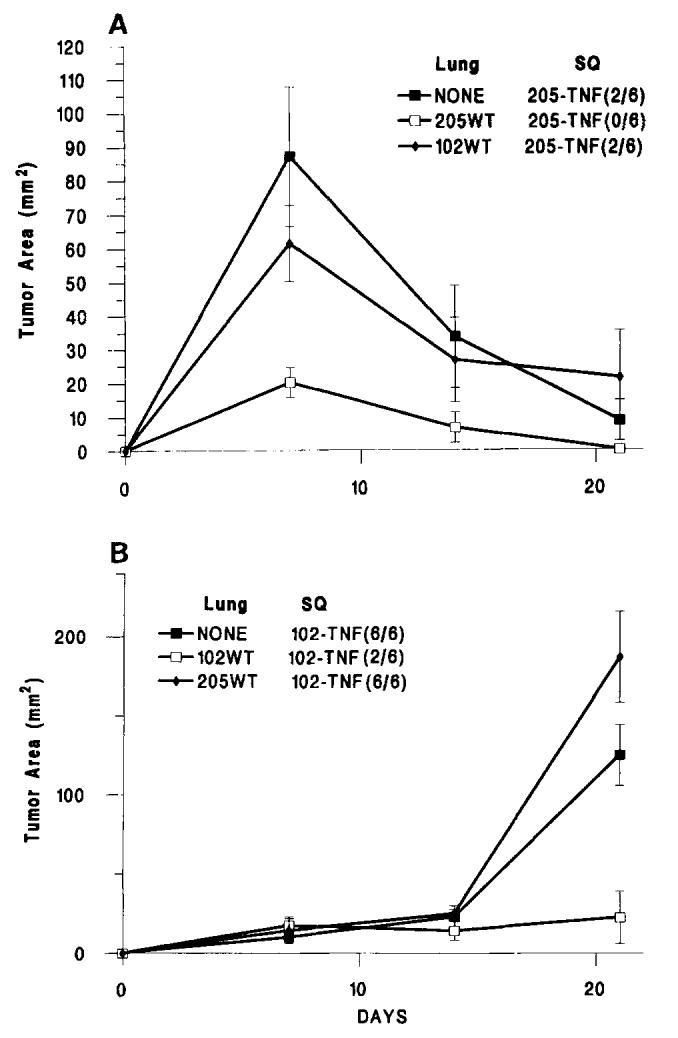

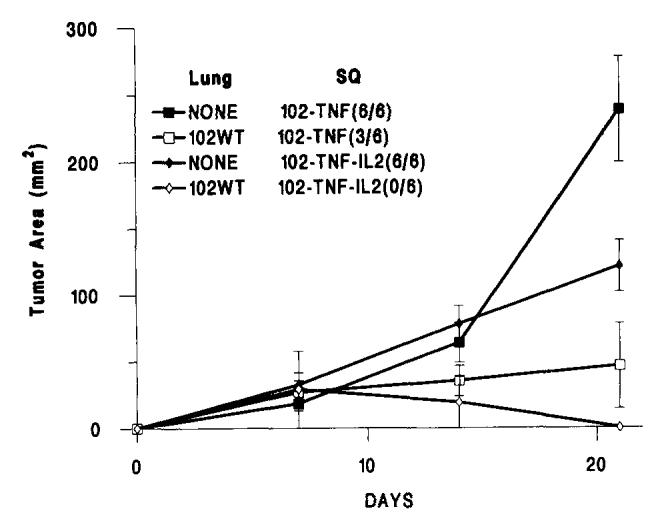

Effect of the presence of the pulmonary metastases on the growth of subcutaneous cytokine-producing tumors

As previously reported (3), MCA-205-hTNF (Fig. 1a) grew and then spontaneously regressed when injected into naive animals. In animals bearing pulmonary metastases of the same tumor line, the growth of subcutaneous tumor appeared slower than in naive mice during the first week, and this difference was statistically significant. Eventually all the MCA-205-hTNF tumor regressed in six consecutive experiments. A different phenomenon was noted when the poorly immunogenic MCA-102-hTNF tumor line was used. As previously reported (11), MCA-102-hTNF grew rapidly when injected in naive animals. However, in animals bearing 7-day primary tumors, MCA-102-hTNF grew at a significantly slower rate and in many occasions regressed totally (Table II). This suppression of growth appeared to be tumor specific, as animals previously inoculated with a different tumor (MCA-205-WT) did not show significant inhibition of growth of the MCA-102-hTNF line (Fig. 1b) compared with animals previously inoculated with MCA-102-WT s.c. (188.0 + 28.8 vs 22.7 + 16.5, p value < 0.001). In two experiments, the expression of MHC class I was tested in MCA-102-hTNF and MCA-205-hTNF and compared with the expression of the same molecules in the respective WT and NeoR-modified tumors: all tumors expressed MHC class I molecules, and no difference was associated with the endogenous production of hTNF-α in the hTNF-modified lines (data not shown). Evidently, in these tumors, the escape from immune recognition was not mediated by loss of MHC class I expression as for MCA-101 (15).

FIGURE 1.

The subcutaneous growth of MCA-induced sarcoma genes modified to produce hTNF. (A), subcutaneous growth of MCA-205-hTNF (5 × 106 cells/animal) and (B) subcutaneous growth of MCA-102-hTNF in the absence of other tumor (NONE) or in the presence of 7-day-old pulmonary metastases generated by i.v. injection of 106MCA-205-WT or MCA-102-WT tumor cells. In brackets is the ratio of animals with detectable tumors at the end of the experiment over the number of animals used in that experiment. (Values for animals without tumors were considered equal to 0). Graph lines represent the mean ± SEM of the tumor area of the subcutaneous implants at 7-day intervals calculated by multiplying the two largest diameters. Lung = presence and type of pulmonary implant; SO = type of subcutaneous implant (see also Table II).

Table II.

Growth of MCA-102-hTNF in mice bearing the same WT tumor

| Lung Tumora |

s.c. Tumorb |

Number of Experiments |

Number of Tumorsc |

Tumor Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NONE | 102-WT | 2 | 15/15 (100) | 348.8 ± 32.2 |

| 102-WT | 102-WT | 6 | 44/44 (100) | 343.5 ± 50.4 |

| NONE | 102-NeoR | 3 | 24/24 (100) | 408.4 ± 34.0 |

| 102-WT | 102-NeoR | 4 | 31/31 (100) | 435.2 ± 24.1 |

| NONE | 102-hTNF | 12 | 92/93 (99) | 184.3 ± 25.0 |

| NONE | 102-hTNF + IL-2 | 2 | 11/12 (92) | 107.5 ± 25.9d |

| 102-WT | 102-hTNF | 16 | 57/114 (50) | 37.9 ± 17.7e |

| 102-WT | 102-hTNF + IL-2 | 3 | 2/18 (11) | 0.6 ± 0.6f |

Pulmonary metastases induced by i.v. injection of 106MCA-102-WT cells.

The s.c. implanted tumor cells (5 to 10 × 106) implanted 7 days after establishment of lung tumors.

Number of animals with detectable tumors at the end of the experiment over number of animals injected (percentage values in parentheses). p values refer to significance of differences compared with the experimental group None 102-hTNF.

p value < 0.05 in both experiments.

p value not applicable in four experiments, <0.05 in four experiments, and <0.01 in the other eight experiments.

p value < 0.01 in all three experiments.

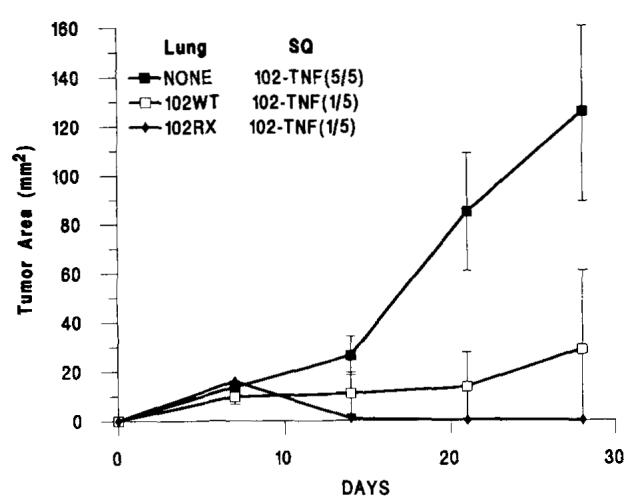

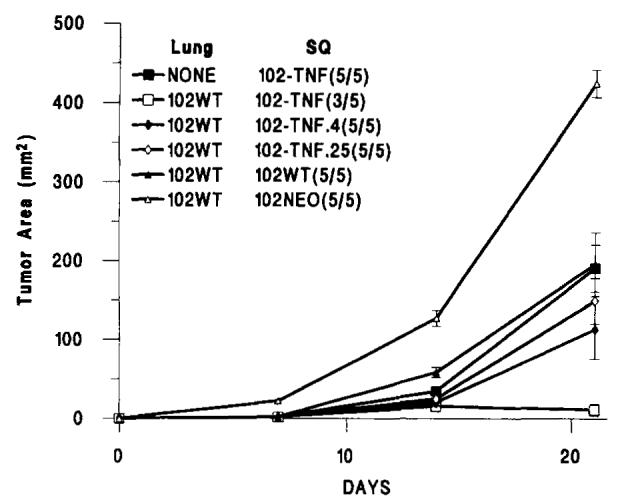

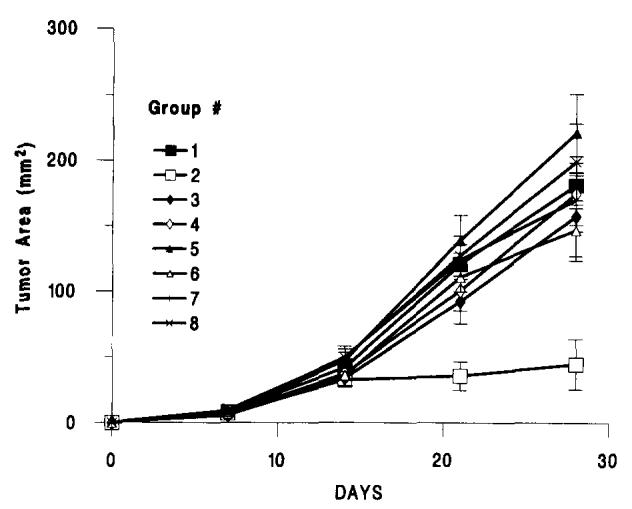

To assess whether the growth retardation or tumor regression of MCA-102-hTNF implants was due to the tumor-bearing stage, we also tested in two consecutive experiments tumor growth in animals that received the injection of irradiated MCA-102-WT cells (30,000 rads). The same retardation of growth was noted even though at autopsy animals were found to be free of pulmonary nodules (Fig. 2) (mean tumor area of MCA-102-hTNF in the presence of i.v. injection of irradiated MCA-102-WT vs no i.v. injection was 31.2.5 ± 23.7 vs 125.3 ± 19.5, respectively, n = 10 animals in each group; p-value < 0.01); no difference was noted comparing subcutaneous growth in these animals with the growth in animals receiving non-irradiated MCA-102-WT i.v. These experiments suggests that the regression of MCA-102-hTNF tumors is due to exposure of the animals specifically to the parental tumor rather than to possible chachexia caused by the presence of pulmonary implants. In four animals bearing MCA-102-WT pulmonary implants, MCA-102-hTNF tumors that failed to regress were harvested and grown in vitro in the presence of G418 selection. In all four cases, tumor cells grew in G418; after the first passage in vitro, the supernatants from these cultures were tested for hTNF-α secretion, and, in no case, were they found to secrete the cytokine. This suggested that a subpopulation of nonsecreting gene-modified cells was present in our cloned population of MCA-102-hTNF tumor cells that expressed the NeoR gene but not the TNF gene and were, perhaps, selected in vivo in those instances in which the MCA-102-hTNF tumor failed to regress. These data suggested that there was heterogeneity of hTNF-α secretion. We, therefore, subcloned MCA-102-hTNF and generated two low producers of hTNF called MCA-102-hTNF.4 and MCA-102-hTNF.25 (see Table I). These clones did not show, in two consecutive experiments (Fig. 3), the same amount of growth retardation shown by MCA-102-hTNF (p value < 0.01 and < 0.001, respectively), thus suggesting that the amount of hTNF secreted was related to tumor regression.

FIGURE 2.

The subcutaneous growth of MCA-102-hTNF in the absence of other tumor (NONE) or in the presence of 7-day-old pulmonary metastases generated by i.v. injection of 1O6MCA-102-WT or lethally irradiated (40,000 rads) MCA-102-WT (MCA-102-RX). In brackets is the ratio of animals with detectable tumors at the end of the experiment over the number of animals used in that experiment. (Values for animals without tumors were considered = to 0). Graph lines represent the mean ± SEM of the tumor area of the subcutaneous implants at 7-day intervals calculated by multiplying the two largest diameters. Lung = presence and type of pulmonary implant; SQ = type of subcutaneous implant; p value < 0.01 for 102WT/102-TNF and 1-2RX/102-TNF compared with NONE/102-TNF.

FIGURE 3.

The subcutaneous growth of MCA-102-hTNF, MCA-102-hTNF.4 and MCA-102-hTNF.25 (both subclones of MCA-102-hTNF secreting low amounts of hTNF-α), MCA-102-WT and MCA-102-NeoR in the absence of other tumor (NONE) or in the presence of 7-day-old pulmonary metastases generated by i.v. injection of 106MCA-102-WT. In brackets is the ratio of animals with detectable tumors at the end of the experiment over the number of animals used in that experiment. (Values for animals without tumors were considered equal to 0). Graph lines represent the mean ± SEM of the tumor area of the subcutaneous implants at 7-day intervals calculated by multiplying the two largest diameters. Lung = presence and type of pulmonary implant; SQ = type of subcutaneous implant; p value < 0.01 for 102WT/102-TNF vs all other experimental groups (see also Table II).

We then tested, in the same model gene, modified lines derived from MCA-102 producing different cytokines. In animals bearing MCA-102-WT lung tumors, subcutaneous tumors expressing IL-4 grew at approximately the same rate as those of the wild type MCA-102-WT line as well as MCA-102-ILA established in naive animals (data not shown). In contrast, similarly to tumors producing hTNF-α, MCA-102-mTNF.15 (a high producer of mTNF) and MCA-102-IFN showed significant growth inhibition in the presence of MCA-102 pulmonary implants (p value < 0.05 for both tumors). MCA-102-mTNF (a low producer of mTNF) did not regress in animals bearing MCA-102-WT pulmonary implants. MCA-102-NeoR grew in vivo at a rate higher than MCA-102-WT and other tumors lines: we believe that this difference is due to clonal variation rather than caused by transduction with LXSN, because, in our experience, we have not noticed such an effect in other cell lines. This phenomenon, however, points out the fact that these type of studies are subject to significant clonal variability and direct comparisons among different cell clones cannot be easily made. On the other hand, MCA-102-NeoR and MCA-205-NeoR failed to show growth retardation in the presence of pulmonary metastases established with MCA-102-WT compared with their growth in native animals thus, behaving similarly to MCA-102-WT (Table II and Fig. 3).

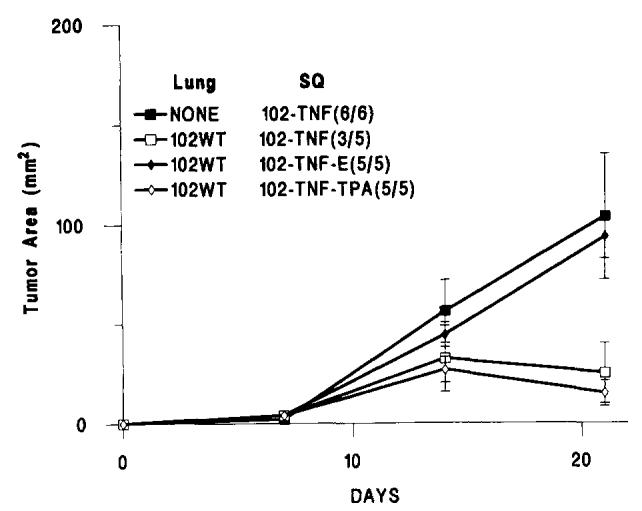

Effect of systemic administration of anti-TNF mAb on the growth of hTNF-α producing tumors

In two experiments, the systemic administration of anti-TNF-α Ab (Fig. 4) inhibited MCA-102-hTNF tumor regression in mice bearing MCA-102-WT tumors, suggesting that hTNF was the important mediator of this phenomenon (p value < 0.0001 in both experiments). An irrelevant isotype-matched Ab had no significant effect on the growth of these tumors (analysis of significance between tumor growth in animals treated with irrelevant Ab and anti-TNF-α Ab: p value = 0.07, and < 0.0.01 in two consecutive experiments, with a cumulative p value < 0.01).

FIGURE 4.

The subcutaneous growth of MCA-induced sarcoma genes modified to produce hTNF-α in animals treated with an anti-TNF mAb (TNF-E) in the presence of 7-day-old pulmonary metastases generated by i.v. injection of 106 MCA-102-WT. Experimental groups included nontreated animals (MCA-102-hTNF) bearing and not bearing established pulmonary metastases, animals treated with TNF-E (MCA-102-hTNF-E), and animals treated with an irrelevant mouse antimurine tissue plasminogen activator (MCA-102-hTNF-TPA). In brackets is the ratio of animals with detectable tumors at the end of the experiment over the number of animals used in that experiment. (Values for animals without tumors were considered equal to 0). Graph lines represent the mean ± SEM of the tumor area of the s.c. implants at 7-day intervals calculated by multiplying the two largest diameters. Lung = presence and type of pulmonary implant; SQ = type of treatment group. Analysis of significance between tumor growth in animals treated with irrelevant Ab and anti-TNF-α Ab: p value < 0.005; difference of growth between animals not treated and animals not treated with anti-TNF-α Ab: p value < 0.001.

Effect of the systemic administration of high dose IL-2 on the growth of TNF-α producing secondary tumors

In two experiments, the systemic administration of high dose IL-2 (300,000 IU i.p. every 8 h for 5 days) caused a weak reduction in the rate of growth of the subcutaneous tumors in naive control animals that did not receive the pulmonary tumor implants. However, in animals primed with the same tumor line (MCA-102-WT) i.v. 7 days earlier, MCA-102-hTNF regressed totally in 100% of the animals tested, therefore suggesting a potentiation of the concomitant immunity phenomenon by IL-2 (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 5.

The subcutaneous growth of MCA-102-hTNF in the absence of other tumor (NONE) or in the presence of 7-day-old pulmonary metastases generated by i.v. injection of 106 MCA-102-WT. Experimental groups included animals treated with MCA-102-hTNF alone and animals treated with MCA-102-hTNF and i.p. administration of IL-2 (50,000 U every 8 h for 5 days starting at the time of tumor implantation) (MCA-102-hTNF-IL-2). In brackets is the ratio of animals with detectable tumors at the end of the experiment over the number of animals used in that experiment. (Values for animals without tumors were considered equal to 0). Graph lines represent the mean ± SEM of the tumor area of the subcutaneous implants at 7-day intervals calculated by multiplying the two largest diameters. Lung = presence and type of pulmonary implant; SQ = type of treatment group (see also Table II).

Effect of depletion of T cells (CD4+ and CD8+) on the growth of TNF-α-producing secondary tumors

Because the presence of the lung tumors appeared to be essential for the regression of hTNF-α secreting tumors, two experiments were done in which we tested the growth of subcutaneous MCA-102-hTNF subcutaneous tumors in MCA-102-WT-bearing animals after depletion of different T cell subsets to assess the involvement of T cell-mediated immunity. Ten mice per group received 1 × 106 MCA-102-WT tumor cell challenge i.v. followed 5 days later by the s.c. injection of 1 × 107 MCA-102-TNF cells. Three groups of mice were depleted of CD4+, CD4+, and CD8+ or CD8+ T cells with one single i.v. injection of the appropriate Ab the day before establishment of pulmonary metastases. Another three groups of mice were depleted in the same fashion, but immune depletion was done by weekly injection of the appropriate Ab starting 5 days after i.v. injection of MCA-102-WT concomitant with the s.c. injection of MCA-102-hTNF tumor cells. These i.v. injections of Ab were sufficient to deplete the spleens of these animals of the relative cell population for a week to 10 days as tested in control experiments by immunostaining of fresh splenocytes using FACS analysis. By 10 days from the i.v. injection of Ab, T cells of the depleted phenotype started to reappear in the spleen of control animals (data not shown). Figure 6 shows that tumors in all immune-depleted animals grew at a significantly faster pace than in animals not treated with antilymphocyte Abs. Depletion of CD8+ cells was not significantly more effective in abolishing concomitant immunity than depletion of CD4+ cells, and one injection of anti-CD8 Ab done before establishment of pulmonary metastases was at least as effective as multiple subsequent injections started 5 days after establishment of pulmonary metastases. Interestingly, the delayed depletion of CD4+ cells started a week after implantation of pulmonary metastases was still effective in permitting tumor growth, as if helper function was necessary during whole duration of the immune-mediated tumor rejection. These data showed that rejection of MCA-102-hTNF in the context of concomitant immunity is a T cell-dependent phenomenon.

FIGURE 6.

The subcutaneous growth of MCA-102-hTNF in the absence of other tumor (Group 1) or in the presence of 7-day-old pulmonary metastases generated by i.v. injection of 106 MCA-102-WT (Groups 2 to 8). Experimental groups included nontreated animals (MCA-102-hTNF) (Groups 1 and 2), animals treated with anti-CD4 T cell determinant GK5.1 mAb either with a single i.v. administration 24 h before implantation of pulmonary metastases (Group 3) or with weekly administrations throughout the experimental period, starting at the time of subcutaneous tumor implantation (Group 6). Similarly, other animal groups were treated with a-CD8 T cell determinant 2.43 mAb either with a single i.v. administration 24 h before implantation of pulmonary metastases (Group 5) or with weekly administrations throughout the experimental period, starting at the time of subcutaneous tumor implantation (Group 8) or a combination of GK1.5 and 2.43 mAbs (Groups 4 and 7). All animals had tumors at the end of the experiment except for those in the 102-WT-102-TNF group (nondepleted animals); for simplicity, in brackets ratio of animals with detectable tumors over the number of animals used in that experiment is shown only for this group (Group 2). Graph lines represent the mean ± SEM of the tumor area of the subcutaneous implants at 7-day intervals calculated by multiplying the two largest diameters. (Values for animals without tumors were considered equal to 0). p value < 0.01 for group 2 vs all other groups.

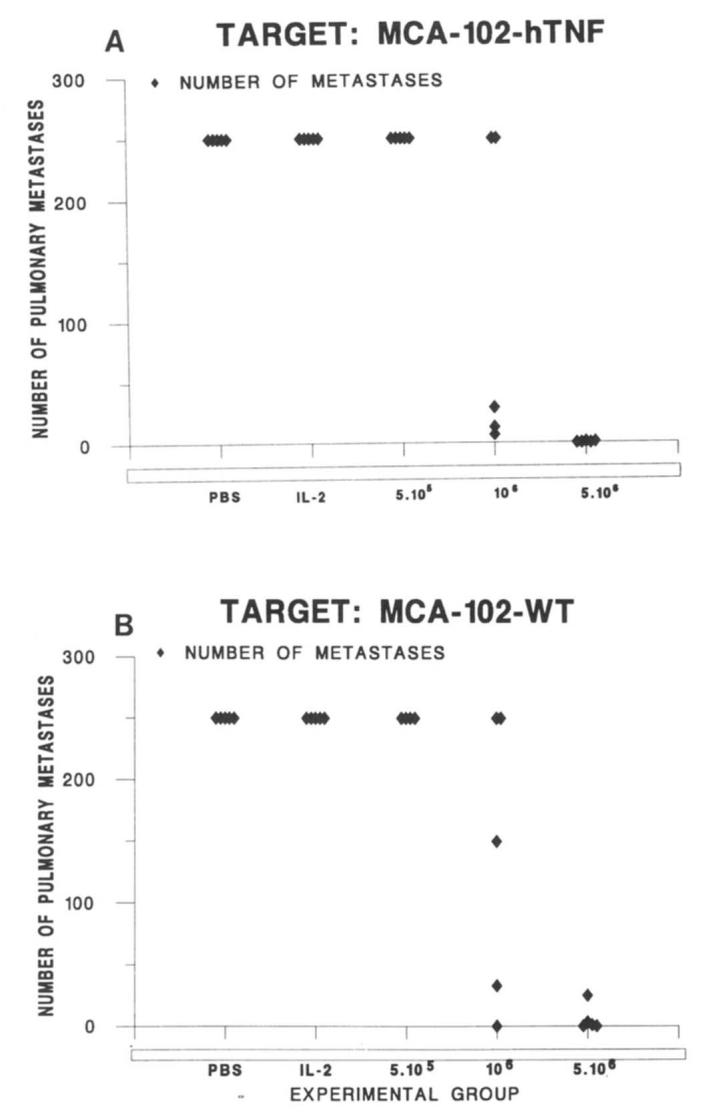

Growth of TIL from MCA-102-TNF tumors in the presence of pulmonary metastases established with MCA-102-WT and their in vivo effect

Nine attempts were made to grow TIL from MCA-102-hTNF tumors before their regression in animals bearing MCA-102-WT; as controls, TIL growth was attempted from MCA-102-WT and MCA-102-NeoR s.c. tumors grown in the same conditions. In nine out of nine cases, tumor overgrowth was noted in TIL cultures from MCA-102-WT and MCA-102-NeoR and no lymphocyte growth was achieved. Four attempts were also made to grow TIL from MCA-102-hTNF tumors in nonpulmonary tumor-bearing animals; in all cases, the growth of TIL was unsuccessful. In no case was tumor overgrowth noted from MCA-102-hTNF TIL cultures, and attempts to grow TIL from MCA-102-hTNF harvested from animals bearing MCA-102-WT pulmonary metastases were successful in four out of nine attempts made. In the other cases, blastic degeneration and poor lymphocyte growth were the cause of culture failure (Table III). TIL generated from MCA-102-hTNF had no lytic activity against the parental as well as the gene-modified tumor cell line in a 51Cr-release assay (tested in two of the TIL lines established) but in four out of four cases they were able to secrete cytokines (mTNF-α, mIFN-γ and mMG-CSF) specifically when cocultured with tumor (Table IV). The TIL were tested in vivo and found to have a therapeutic antitumor effect against established MCA-102-WT and MCA-102-hTNF pulmonary metastases (Table V, Fig. 7). FACS analysis of these TIL generated from MCA-102-hTNF tumors showed them to be predominantly CD8+ (data not shown).

Table III.

Generation of TIL from s.c. tumors in MCA-102-WT bearing mice

| TIL Source | Lung Tumor MCA-102-WTa |

Successful Growth of TIL Growth/Attemptsb |

|---|---|---|

| MCA-102-WT | + | 0/9 |

| MCA-102-NeoR | + | 0/9 |

| MCA-102-hTNF | + | 4/9c |

| MCA-102-hTNF | − | 014 |

+, means that primary tumors were established, −, means that no primary implantation was performed (naive animals).

Growth/Attempts is the ratio of successful TIL cultures over the number of attempts made.

p value <0.05 comparing growth of TIL from MCA-102-hTNF vs MCA-102-WT and MCA-102-Neo in the presence of established pulmonary metastases (+).

Table IV.

Cytokine secretion by MCA-102-hTNF generated TIL

| Stimulator Tumor |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiments | MCA-102-WT | MCA-102-hTNF | MCA-205-WT | NONE |

| Experiment 1 | ||||

| mTNF-αa | 1522 | 1451 | 214 | 0 |

| mIFN-γ2b | 7108 | 6891 | 146 | 146 |

| mGM-CSFa | 75 | 102 | 0 | 7 |

| Experiment 2 | ||||

| mTNF-α | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| mIFN-γ | 5860 | 6348 | 109 | 0 |

| GM-CSF | 12 | 28 | 0 | 24 |

| Experiment 3 | ||||

| mTNF-α | 1786 | 616 | 0 | 0 |

| mIFN-γ | 6620 | >7000 | 0 | 9 |

| mGM-CSF | 220 | 198 | 0 | 2 |

| Experiment 4 | ||||

| mTNF-α | 0 | 0 | 0 | 631 |

| mIFN-γ | 3168 | 6403 | 109 | 109 |

| GM-CSF | 23 | 74 | 8 | 14 |

Endogen (pg/ml).

GIBCO BRL (pg/ml). Values are given after subtracting the spontaneous release of cytokine by the relevant tumor in the same assay.

Table V.

Adoptive immunotherapy with MCA-102-hTNF TIL

| Number of Lung Metastases |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effector | Experiment 1a | Experiment 2 | Experiment 3 | Experiment 4 |

| PBS | 250.0 ± 0 | 250.0 ± 0 | 250.0 ± 0 | 250.0 ± 0 |

| IL-2 | 250.0 ± 0 | 250.0 ± 0 | 250.0 ± 0 | 250.0 ± 0 |

| LAK | ND | ND | 172.8 ± 54 | 144.8 ± 52 |

| (1 × 107) | ||||

| TIL | 250.0 ± 0 | 250.0 ± 0 | 219.6 ± 34 | 250.0 ± 0 |

| (5 × 105) | ||||

| TIL | 136.6 ± 59 | 164.4 ± 58 | 250.0 ± 0 | 189.0 ± 51 |

| (1 × 106) | ||||

| TIL | 5.8 ± 5b | 3.6 ± 3b | 64.4 ± 53c | 77.6 ± 50c |

| (5 × 106) | ||||

Five animals per group were used in each experiment. All animals received effector cells i.v. 3 days after establishment of the pulmonary metastases and then received 10,000 U of IL-2 i.p. every 8 h for 3 days.

p value < 0.01.

p value < 0.05.

FIGURE 7.

Number of pulmonary metastases generated by i.v. injection of 106MCA-102-WT (B) or MCA-102-hTNF (A) after adoptive immunotherapy with incremental doses of TIL generated from MCA-102-hTNF. Control groups include PBS (animals receiving sham injections with PBS) and IL-2 (animals receiving only IL-2 at the dose of 10,000 i.p. every 8 h for 3 days. Five animals per group were used in each experiment, all animals received effector cells i.v. 3 days after establishment of the pulmonary metastases and then received 10,000 U of IL-2 intraperitoneally every 8 h for 3 days. Mean ± SEM number of pulmonary metastases for four consecutive experiments are presented on Table VI.

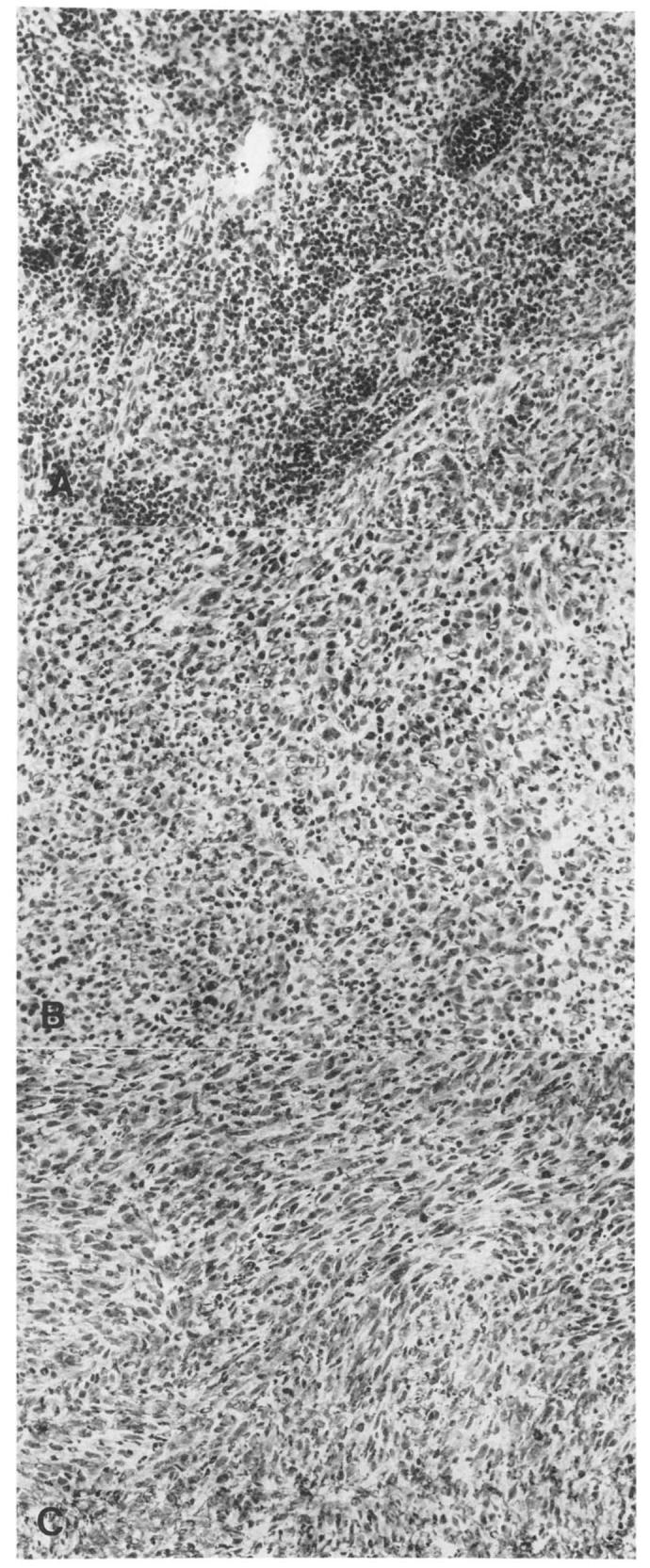

Histologic analysis of the subcutaneous implants

Histologic study of tumor obtained at day 10 after subcutaneous implantation revealed that the tumors were composed of large, spindle-shaped neoplastic cells arranged in interlacing cords and bundles. The nuclei were large, hyperchromatic, and pleomorphic. There were numerous mitoses and areas of focal necrosis in all tumors. An intense peritumoral as well as intratumoral lymphocytic infiltrate was seen in MCA-102-hTNF tumors implanted in MCA-102-WT-bearing animals (Fig. 8). The infiltrate was much less pronounced in the non-MCA-102-WT-bearing animals and was almost totally absent in animals injected with MCA-102-WT. Table VI show the specific characteristics for each animal tested.

FIGURE 8.

Lymphocytic infiltrate in animals injected with MCA-102-hTNF in the presence (A) or absence (B) of established pulmonary metastases with MCA-102-WT. The subcutaneous tumor implants from MCA-102-WT are also shown (C) (H & E).

Table VI.

Lymphocytic infiltrate in s.c. implants of MCA-102-hTNFa

| Mouse Number |

SQ | IV | Sizeb (mm) |

L.I.c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | hTNF | + | 5 × 5 | +4 |

| 2 | hTNF | + | 7 × 7 | +4 |

| 3 | hTNF | + | 5 × 5 | +4 |

| 4 | hTNF | + | 5 × 8 | +4 |

| 5 | hTNF | − | 11 × 11 | +2 |

| 6 | hTNF | − | 14 × 15 | +2 |

| 7 | hTNF | − | 13 × 13 | +3 |

| 8 | hTNF | − | Early death | |

| 9 | WT | + | 15 × 15 | +1 |

| 10 | WT | + | 12 × 14 | +1 |

| 11 | WT | + | 13 × 13 | +1 |

| 12 | WT | + | 13 × 14 | +1 |

Animals were injected s.c. either with MCA-102-hTNF or WT (SQ, type of s.c. implant) in the presence or absence of pulmonary metastases established by i.v. injection of MCA-102-WT (IV). Beginning with the s.c. implantation (at the time when tumor rejection is usually noted) tumors were harvested and histologically examined for lymphocytic infiltration.

Size refers to the two largest perpendicular diameters (mm) of the subcutaneous tumors at the time of animals termination.

L.I., grading of lymphocytic infiltration according to a blind analysis of the slides done by a pathologist. p value < 0.01 for all groups comparisons (Normalized Kruskal-Wallis test).

Discussion

Immunogenic sarcomas (such as MCA-205) have been shown to regress spontaneously when genetically engineered to secrete cytokines such as IL-2 and hTNF (7, 11); however, this is a phenomenon of limited usefulness as a model for cancer therapy as no effect of these gene-modified tumor implants on distant tumors has been seen. Golumbek et al. (23) described a moderate antineoplastic effect by mIL-4-secreting immunogenic renal cancer cells on distant pulmonary implants. We attempted to evaluate the effect of MCA-102-mIL4 on distant pulmonary metastases established with the parental line, but in spite of a high secretion of mIL-4, we could not detect a significant effect either on the number of the distant metastases or in the rate of growth of the gene-modified tumor itself (data not shown). We attributed this failure to the poor immunogenicity of the MCA-102 tumor line. The MCA-102 tumor, however, appears to be an excellent experimental model for studies of immunotherapy because it is poorly immunogenic, has low but still sufficient expression of MHC class I molecules, is capable of presenting Ag and is partially capable of eliciting specific CTL growth in vitro (9, 24). We thus attempted to evaluate the direct therapeutic effect of other cytokine-producing clones of MCA-102 including IFN-γ, mTNF-α, as well as hTNF-α on established lung metastases of MCA-102-WT. The results of this extensive screening were at best inconclusive.

During the conduct of these experiments, we incidentally noted, however, that some cytokine-producing clones (MCA-102-hTNF, MCA-102-mTNF.15, and MCA-102-IFN) grew poorly if at all in animals bearing the WT parental tumor MCA-102-WT, whereas growths of these clones were normal in naive animals (Fig. 1). This phenomenon (at least for hTNF) seemed to be: 1) tumor specific, as animals bearing MCA-205-WT tumor implants showed no growth inhibition MCA-102-hTNF; 2) specific for the secretion of hTNF-α, as it was reversed by anti-hTNF antibodies; 3) potentiated by the systemic administration of IL-2; and 4) mediated by T cells since immune depletion with GK1.5 and 2.43 mAbs abrogated the tumor growth.

Because the different growth pattern of the different cell lines could be, at least partially, ascribed to clonal variation, comparison of growth among different lines should be done carefully. On the other hand, in these experiments, we refer to growth retardation as paired observation done on the same clones in the presence or absence of pulmonary metastases established with the WT parental line. All cell lines described (except for those producing significant amounts of h or mTNF-α or mIFN-γ) were not affected by the presence of tumor of the WT. We also noted that MCA-102-NeoR had a faster growth rate compared with MCA-102-WT and the other tumors. This is probably not related to a direct effect of transduction of LXSN plasmid, as we have not commonly seen this in many other occasions. This variability is probably a result of clonal variation: a phenomenon unfortunately common in these animal models and one that needs to be considered upon interpretation of the data. We do not believe, however, that the main phenomenon described in this study (that is growth inhibition of MCA-102-hTNF in the presence but not in the absence of MCA-102-WT tumor implants) is caused by clonal variation or other artifact; to support this point is the fact that anti-TNF Abs in two separate experiments inhibited the phenomenon at the <0.001 level.

We were particularly interested in the effects of TNF secretion by tumors because MCA-induced sarcomas have been shown to be sensitive to parenteral administration (50 to 100 mg/Kg i.v. every other day for 6 days) of hTNF. These sarcoma cell lines are resistant in vitro to TNF cytotoxicity (25) and require host-mediated factors for the complete in vivo anti-tumor effect as total tumor regression is not present in nude mice (nu/nu) compared with nu/+ mice (26). Interestingly, the systemic administration of IL-2 after administration of systemic rTNF-a causes complete regression of tumor implants, but the reverse is not true (27, 28). Besides a direct antitumor effect in vivo (1), TNF-α has a broad spectrum of immunomodulatory effects that among others (1), include T cell proliferation (3), activation of CTL (4), and increased expression of endothelial cell-surface molecules such as ELAM-1 (29), ICAM-1 (30, 31), and VCAM-1 (32), which may allow increased migration of lymphocytes into local areas. Participation of other Ag-presenting cells has also been suggested as important for tumor recognition and lysis by TNF (33).

Because of the multiple effects of this cytokine on the immune system and the immune-mediated enhancement of recognition of MCA-102-hTNF by hTNF-α as discussed so far, we decided to evaluate whether this hTNF-α-producing tumor could be used as a “vaccine” for the development of an adoptive immunotherapy model similar to the hypothetical clinical situation in which patients bearing metastatic tumors could donate an easily removable lesion for similar purposes. This tumor could be engineered in the laboratory to secrete cytokines and then replanted in the same patient with the intent of eliciting enhancement of antitumor immune responses.

MCA-102 is a very poorly immunogenic tumor, and attempts to immunize against it by repeated inoculations of irradiated tumor cells alone or in adjuvant have been unsuccessful (9). We have also not been able, with very rare exceptions, to grow TIL from MCA-102-WT or MCA-102-hTNF tumors growing in naive animals. We, therefore, tried to exploit the immune mediate regression of MCA-102-hTNF by growing TIL from these “activated” tumors before their regression, which predictably occurred between 7 and 15 days after tumor implantation. Growth of TIL from these tumors was attempted using standard methods normally used for growth of mTIL (19, 20).

We found, indeed, that it was possible to grow TIL from tumor implants secreting MCA-102-hTNF obtained from animals bearing the WT tumors in four out of nine attempts. In each one of the attempts, three tumors were harvested and used to grow lymphocytes. TIL growth was quite limited in time, and a tendency to blastic degeneration of the growing TIL was noted after a few weeks in culture, in spite of multiple restimulations with autologous irradiated tumor. The lytic activity of two TIL cultures was assessed in a 51Cr-release assay, and in neither experiment did we detect any lytic activity against autologous WT or hTNF-secreting tumor. In all four experiments, we assessed the ability of TIL to secrete cytokines when cultured in the presence or absence of autologous tumor stimulation (MCA-102-WT). In all cases, we noted that these TIL were able to secrete cytokines specifically to the MCA-102 tumor lines: this finding is in agreement with a correlation noted between cytokine secretion and in vivo therapeutic activity of TIL already described in these murine tumor models (5).

It should be emphasized that we were unable to grow TIL from MCA-102-WT or MCA-102-LXSN harvested from tumor-bearing animals. Tumor overgrowth was the cause of culture failure, while in no case was tumor overgrowth noted from TIL cultures from MCA-102-hTNF in tumor bearing mice.

Even though FACS analysis of the TIL derived from MCA-102-hTNF tumors revealed them to be predominantly CD8+ (2/2 occasions), in vivo depletion of CD8+ T cells (by 2.43 mAb) had similar effects to depletion of CD4+ cells (with GK1.5 mAb). Furthermore, a single i.v. administration of 2.43 mAb and/or GK1.5 was as effective as several weekly injections of the same mAbs given during the course of the experiment, showing that the critical moment for immune recognition was during the first week between primary and secondary tumor implantation.

This model has some important similarities to the clinical situation in tumor-bearing humans. In patients, vaccine therapy will of course occur in the presence of established concomitant tumors. In our preliminary study of melanoma patients treated with hTNF-α secreting autologous tumor implants, regression of the gene-modified tumor implants was always seem to be associated with signs of inflammatory reaction in the areas of tumor implantation. Biopsies at tumor implantation site failed to show remaining tumor cells (34). This regression occurred with approximately the same timing noted in the murine model (approximately 2 wk). No attempt has been made as yet to grow TIL from these human tumors before their regression, while attempts to grow CTLs from draining lymph nodes have been unsuccessful (34). If the mechanisms of rejection responsible for regression of the hTNF-secreting implants is shared by the murine model, it is possible that therapeutic TIL could be grown from these tumor implants, and this possibility might be considered in a pilot study.

This study is mainly phenomenologic as it was originally conceived as a preclinical investigation on the effect of cytokine-producing tumors on distant tumors of the WT. The incidental finding of tumor growth retardation of MCA-102-hTNF (and mTNF) tumor only in the presence of pulmonary metastases of the same tumor, lead us to the development of a new strategy for the derivation of TIL from poorly immunogenic tumors. The goal of this study, therefore, is to describe a possible new strategy for the growth of therapeutic lymphocytes from nonimmunogenic tumors that, in our hands, worked best with hTNF-α among the different transfectants tested.

Finally, the possibility should be considered that the regression of the MCA-102-hTNF tumor implants could be related to recognition of a xenogenic hTNF-α molecule on the cell surface. hTNF is present on the surface of gene-modified cells (10) and could represent an antigenic stimulus for the murine immune system; however, animals that were not immunized with MCA-102-WT (not presenting the hTNF molecule) did not reject the tumor implant, MCA-102-mTNF (secreting mTNF) also was slowed in its growth by the same model, and, finally, TIL grown from MCA-102-hTNF were able to recognize in vitro and in vivo not only MCA-102-hTNF but also the parental MCA-102-WT not bearing the hTNF molecule.

In summary, it appears that injection of MCA-102-hTNF in the subcutis of C57/BL6 mice 5 to 10 days after the establishment of MCA-102-WT pulmonary metastases results in a potent immune recognition of this poorly immunogenic tumor which is 1) tumor specific, 2) TNF-α specific, 3) requires the presence of cellular immunity, and 4) allows growth of therapeutically effective TIL from a tumor line generally unable to elicit a significant immune response.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: TIL, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes; MCA, methylcholanthrene; LAK, lymphokine-activated killer cells; WT, wild type; CM, complete medium; h, human; m, murine.

References

- 1.Spriggs DR. Tumor necrosis factor: basic principles and preclinical studies. In: DeVita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, editors. Biologic Therapy of Cancer. J. B. Lippincott; Philadelphia: 1991. pp. 354–77. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asher AL, Mulé JJ, Reichert CM, Shiloni E, Rosenberg SA. Studies on the anti-tumor efficacy of systemically administered recombinant tumor necrosis factor against several murine tumors in vivo. J. Immunol. 1987;138:963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheurich P, Thoma B, Ucer V, Pfizenmaier K. Immunoregulatory activity of recombinant human tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α induction of TNF receptors on human cells and TNF-α-mediated enhancement of T cell responses. J. Immunol. 1987;138:1786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ranges GE, Figari IS, Espevik T, Palladino MA. Inhibition of cytotoxic T cell development by transforming growth factor-β and reversal by recombinant tumor necrosis factor-α. J. Exp. Med. 1987;166:991. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.4.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barth RJ, Jr., Bock SN, Mulé JJ, Rosenberg SA. Unique murine tumor-associated antigens identified by tumor infiltrating lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 1990;144:1531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hwu P, Yannelli J, Kriegler M, Anderson WF, Perez C, Chiang Y, Schwarz S, Cowherd R, Delgado C, Mule' JJ, Rosenberg SA. Functional and molecular characterization of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes transduced with tumor necrosis factor-α cDNA for the gene therapy of cancer in humans. J. Immunol. 1993;150:4104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asher AL, Mulé JJ, Kasid A, Restifo NP, Salo JC, Reichert CM, Jaffe G, Fendly B, Kriegler M, Rosenberg SA. Murine tumor cells transduced with the gene for tumor necrosis factor-α. J. Immunol. 1991;146:3327. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qin Z, Krugen-Krasagakes S, Kunzendorf U, Hock H, Diamantstein T, Blankenstein T. Expression of tumor necrosis factor by different tumor cell lines results in tumor suppression or augmented metastasis. J. Exp. Med. 1993;178:355. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.1.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mulé JJ, Yang CJ, Lafreniere R, Shu S, Rosenberg SA. Identification of cellular mechanisms operational in vivo during the regression of established pulmonary metastases by the systemic administration of high dose recombinant IL-2. J. Immunol. 1987;139:285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karp SE, Hwu P, Farher A, Restifo NP, Kriegler M, Mulé JJ, Rosenberg SA. In vivo activity of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) mutants. Secretory but not membrane bound TNF mediates the regression of retrovirally transduced murine tumor. J. Immunol. 1992;149:2076. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karp SE, Farber A, Salo JC, Hwu P, Jaffe G, Asher AL, Shiloni E, Restifo NP, Mulé JJ, Rosenberg SA. Cytokine secretion by genetically modified nonimmunogenic murine fibrosarcoma. Tumor inhibition by IL-2 but not tumor necrosis factor. J. Immunol. 1993;150:896. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorelik E. Concomitant tumor immunity and the resistance to a second tumor challenge. Adv. Cancer Res. 1983;39:7l. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)61033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wexler H, Rosenberg SA. Pulmonary metastases from autochthonous 3-methylcholanthrene-induced murine tumors. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1979;63:1393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kasid A, Morecky S, Aebersold P, Cornetta K, Culver K, Freeman S, Director E, Lotze MT, Blaise RM, Anderson WF, Rosenberg SA. Human gene transfer: characterization of human tumor infiltrating lymphocytes as vehicles for retroviral-mediated gene transfer in man. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:473. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.1.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Restifo NP, Spiess PJ, Karp SE, Mulé JJ, Rosenberg SA. A nonimmunogenic Sarcoma transduced with the cDNA for interferon-γ elicits CD8+ T cells against the wild type tumor: correlation with antigen presentation capability. J. Exp. Med. 1992;175:1423. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.6.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tepper RI, Pattengale PK, Leder P. Murine interleukin-4 displays potent anti-tumor activity in vivo. Cell. 1989;57:503. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90925-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takebe Y, Seiki M, Fujisawa J, Hoy P, Yokota K, Arai K, Yoshida M, Arai N. SR-α promoter: an efficient and versatile mammalian cDNA expression system composed of the simian virus 40 early promoter and the R-U5 segment of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 long terminal repeat. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1988;8:466. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.1.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cobbold SP, Martin G, Qin S, Waldman H. Monoclonal antibodies to promote marrow engraftment and tissue graft tolerance. Nature. 1986;323:164. doi: 10.1038/323164a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang JC, Perry-Lalley D, Rosenberg SA. An improved method for growing murine tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes with in vivo anti tumor activity. J. Biol. Response Modif. 1990;9:149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barth RJ, Jr., Mulé JJ, Asher AL, Sanda MG, Rosenberg SA. Identification of unique murine tumor-associated antigens by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes using tumor-specific secretion of interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor. J. Immunol. Methods. 1991;140:269. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(91)90380-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mulé JJ, Shu S, Rosenberg SA. The anti-tumor efficacy of lymphokine-activated killer cells and recombinant IL-2 in vivo. J. Immunol. 1985;135:646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ozato K, Sachs DH. Monoclonal antibodies to mouse MHC antigens. J. Immunol. 1981;126:317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Golumbek PT, Lazenby AJ, Levitsky HI, Jaffee LM, Karasuyama H, Baker M, Pardoll DM. Treatment of established renal cancer by tumor cells engineered to secrete interleukin-4. Science. 1991;254:713. doi: 10.1126/science.1948050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Restifo NP, Esquivel F, Asher AL, Stotter S, Barth RJ, Bennink JR, Mulé JJ, Yewdell JW, Rosenberg SA. Defective presentation of endogenous antigens by a murine sarcoma. Implications for the failure of an anti-tumor immune response. J. Immunol. 1991;147:1453. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Creasey AA, Doyle LV, Reynolds MT, Jung T, Lin LS, Vitt CR. Biological effects of recombinant human tumor necrosis factor and its novel muteins on tumor and normal cell lines. Cancer Res. 1987;47:145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haramaka K, Satomi N, Sakura A. Antitumor activity of murine tumor necrosis factor (TNF) against transplanted murine tumors and hetero-transplanted human tumors in nude mice. Int. J. Cancer. 1984;34:263. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910340219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zimmerman RJ, Gauny S, Chan A, Landre P, Winkelhake JL. Sequence dependence of administration of human recombinant tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-2 in murine tumor models. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1989;81:227. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McIntosh JK, Mulé JJ, Merino MJ, Rosenberg SA. Synergistic antitumor effects of immunotherapy with recombinant interleukin-2 and recombinant tumor necrosis factor-α. Cancer Res. 1988;48:4011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bevilacqua MP, Stengelin S, Gimbrone MAJ, Seed B. Endothelial leukocyte adhesion molecule 1: an inducible receptor for neutrophils related to complement regulatory proteins and lectins. Science. 1989;243:1160. doi: 10.1126/science.2466335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marlin SD, Springer TA. Purified intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) is a ligand for lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1) Cell. 1987;51:813. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dustin ML, Springer TA. Lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1) interaction with intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) is one of at least three mechanisms for lymphocyte adhesion to cultured endothelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 1988;107:321. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.1.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Osborn L, Hession C, Tizard R, Vassallo C, Luhowskyj S, Chi-Rosso G, Lobb R. Direct expression cloning of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1, a cytokine-induced endothelial protein that binds to lymphocytes. Cell. 1989;59:1203. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90775-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shaw H. Characteristics and mechanisms of neutrophil-mediated cytostasis induced by tumor necrosis factor. J. Immunol. 1987;139:3676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosenberg SA. Gene therapy for cancer. JAMA. 1992;268:2416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]