Abstract

Activation of T lymphocytes in the absence of a costimulatory signal can result in anergy or apoptotic cell death. Two molecules capable of providing a costimulatory signal, B7-1 (CD80) and B7-2 (CD86), have been shown to augment the immunogenicity of whole-tumor cell vaccines. To explore a potential role for costimulation in the design of recombinant anticancer vaccines, we used lacZ-transduced CT26 as an experimental tumor and β-galactosidase (β-gal) as the model tumor antigen. Attempts to augment the function of a recombinant vaccinia virus (rVV) expressing β-gal by admixture with rVV expressing murine B7-1 were unsuccessful. However, a double recombinant vaccinia virus engineered to express both B7-1 and the model antigen β-gal was capable of significantly reducing the number of pulmonary metastases when administered to mice bearing tumors established for 3 or 6 days. Most important, the double recombinant vaccinia virus prolonged the survival of tumor-bearing mice. These effects were antigen specific. The related costimulatory molecule B7-2 was found to have a similar, although less impressive enhancing effect on the function of a rVV expressing β-gal. Thus, the addition of B7-1 and, to a lesser extent, B7-2 to a rVV encoding a model antigen significantly enhanced the therapeutic antitumor effects of these poxvirus-based, therapeutic anticancer vaccines.

INTRODUCTION

Engagement of the T-cell receptor is the sine qua non for T-cell activation, but it is only the first of two signals required for an optimal T-cell response (1). Specialized APCs,2 such as dendritic cells, possess costimulatory molecules which can enhance the activation and clonal proliferation of T lymphocytes. Anergy or apoptotic cell death can result when signaling occurs through the T-cell receptor in the absence of this “second signal.” Two molecules capable of providing a costimulatory signal have been designated B7-1 (CD80) and B7-2 (CD86) (2, 3). These molecules interact with T-lymphocyte ligands, CD28 and CTLA-4, and initiate a cascade of effects mediated, in part, by up-regulation of interleukin 2 production (4). Although neither molecule is expressed on most carcinomas or sarcomas (5), transfection of tumors with B7-1 or B7-2 results in increased tumor immunogenicity, leading to the generation of primary tumor-specific CTLs, protection against subsequent challenge with the wild-type tumor, and active treatment of established disease (6).

The cloning of Ags recognized by therapeutic antitumor T lymphocytes (TAA) has made it possible to construct recombinant anticancer vaccines. Recent attempts to exploit rVVs as immunogens have included the use of rVV encoding B7-1 or B7-2 to infect tumor cells ex vivo. Cells infected with rVV expressing a costimulatory molecule were not lethal, whereas cells infected with wild-type vaccinia virus resulted in progressive tumor growth and the death of the host (7). Another study by the same group of investigators showed that simultaneous vaccination of mice via tail scarification with a 3:1 admixture of two rVVs encoding either a model TAA, human CEA (rV-CEA), or B7-1 (rV-B7), respectively, elicited an enhanced CEA-specific lymphoproliferative response and protected mice against tumor development upon challenge with human CEA-expressing tumor cells (8). In this report, we explore the potential use of rVV expressing costimulatory molecules along with TAA in the treatment of established tumor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and Cell Lines

Female BALB/c (H-2d) mice were obtained from the Frederick Cancer Research Center (Frederick, MD). Unirradiated 6–8-week-old mice were immunized with a total of 107 PFUs of the indicated rVV, unless otherwise stated. CT26 is an N-nitroso-N-methylurethrane-induced BALB/c (H-2d) undifferentiated colon carcinoma. The cloning of this tumor cell line to produce CT26.WT and the subsequent transduction with lacZ and subcloning to generate CT26.CL25, which stably expresses β-gal, has been described previously (9). Cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640, 10% heat-inactivated FCS (Biofluids, Rockville, MD), 0.03% l-glutamine, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 100 μg/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml gentamicin sulfate (NIH Media Center). CT26.CL25 was maintained in media containing 400 or 800 μg/ml G418 (Life Technologies, Inc., Grand Island, NY).

Construction and Characterization of rVV

Construction and characterization of rVV containing murine B7-1 gene (B7-1 rVV), B7-2 gene (B7-2 rVV), B7-1 gene and B7-2 gene (B7-1B7-2 rVV), and the MHA gene (MHA rVV) will be described in more detail elsewhere.3 Briefly, the B7-1 gene (a gift from Dr. R. Germain, NIH) and the MHA gene (a gift from Dr. S. Rozenblatt, Tel Aviv University, Israel) were cloned into the transfer plasmid pRB21 under control of the VV synthetic early/late promoter (10). The gene of interest was inserted into the HindIII F region of VV. The production and selection of rVV, in which the VV thymidine kinase gene was utilized as an insertion site, were similar to those described previously, unless otherwise stated (11). The B7-1β-gal rVV, B7-2β-gal rVV, and MHAβ-gal rVV were constructed by homologous recombination of the plasmid pSC65Δ (a modification of pSC65)4 with B7-1 rVV, B7-2 rVV, and MHA rVV, respectively. The B7-1B7-2β-gal rVV was constructed by homologous recombination of the transfer plasmid pSC11 containing the B7-1 gene, such that B7-1 (VV synthetic early/late promoter) was in the HindIII F region of VV, while both the B7-2 (VV 7.5K promoter) and Escherichia coli lacZ gene (VV, 11K promoter) remained in the thymidine kinase region of VV. Transfer plasmid pGS69 (12) containing the NP gene was recombined with B7-1 rVV to yield B7-1NP rVV (Table 1). rVV names have been truncated to facilitate understanding; investigator designation for the viruses constructed are as follows in parentheses; B7-1β-gal rVV (vMCB7-1β-gal), MHAβ-gal rVV (vMCMHAβ-gal), B7-2β-gal rVV (vMCB7-2β-gal), B7-1B7-2β-gal rVV (vMCB7-1β-gal), MHAB7-2β-gal rVV (vMCMHAB7-2β-gal), and B7-1/NP rVV (vMCB7-1NP). Preparation of the rVV expressing the influenza A/PR/8/34 NP, V69NP rVV (NP-VAC), has been described previously (12). Viral B7-1 expression was confirmed by cell surface staining, an in vitro functional assay, and Western blotting.3

Table 1.

Construction of rVVs

| VP37 |

Thymidine Kinase |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rVV Code | Promoter | Gene | Promoter | Gene |

| B7-1β-gal rVV | S.E/La | B7-1 | 7.5b | β-gal |

| MHAβ-gal rVV | S.E/L | MHA | 7.5b | β-gal |

| B7-1NP rVV | S.E/L | B7-1 | 7.5b | NP |

| B7-2β-gal rVV | S.E/L | B7-2 | 7.5b | β-gal |

| B7-1B7-2β-gal rVV | S.E/L | B7-1 | 7.5b | B7-2 |

| 11c | β-gal | |||

| MHAB7-2B-gal rVV | S.E/L | MHA | 7.5b | B7-2 |

| 11c | β-gal | |||

S.E/L, vaccinia synthetic early late promoter.

Early/late VV 7.5K promoter.

Late VV 11K promoter.

In Vivo Experiments

In vivo protection (9) and primary adoptive transfer methodology has been described previously (13). In vivo active treatment studies involved BALB/c mice inoculated i.v. with 5 × 105 tumor cells of either CT26.WT or CT26.CL25. Mice were subsequently vaccinated 3 or 6 days later with either HBSS or 107 PFUs of the designated rVV. Mice were randomized and sacrificed on day 12, and lung metastases were enumerated in a blinded fashion. Identically treated groups of mice bearing 3-day-old tumor burdens were also followed long term to assess the effect of vaccination on survival. A similar protocol was followed for the rVV admixture studies in which two rVV were administered simultaneously at a 1:1 ratio of 107 PFUs of each virus or in ratios of 3:1, 1:1, and 1:3 with a total of 107 PFUs.

Statistical Analysis

Data involving lung metastases does not follow a normal distribution because all lungs that contain >250 metastases were deemed too numerous to count. Data from in vivo protection, adoptive transfer, and active treatment studies were analyzed using the nonparametric two-tailed Kruskal-Wallis test. Survival was analyzed with standard Kaplan-Meier survival curves. All P values presented are two sided.

RESULTS

Treatment of Tumor-bearing Mice with rVV Expressing B7-1

We hypothesized that aberrant B7 expression on tumor cells may result in immune-mediated tumor destruction or autoimmunity upon infection of normal cells. Previous studies have used rVV expressing B7-1 administered to tumor cells either ex vivo or to mice scarification (8). In the present study, the rVV was given i.v. Despite the potential for the elicitation of autoimmune phenomenon, mice given 107 PFUs of a rVV expressing B7-1, designated here as B7-1NP rVV, displayed no evidence of enhanced systemic illness or toxicity, weight loss, or increased death in mice (data not shown).

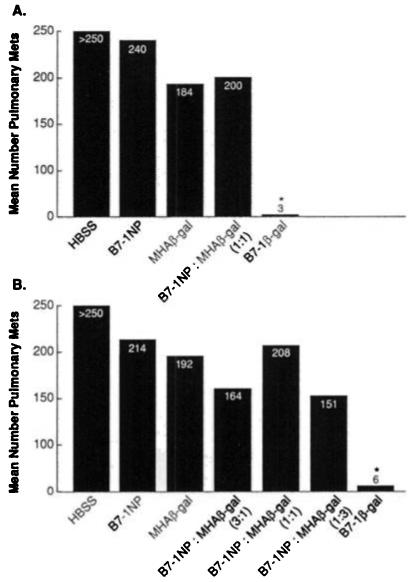

To explore the potential augmentation of therapeutic immune responses in tumor-bearing mice, B7-1NP rVVs were given alone or in combination with a rVV expressing the model TAA β-gal, called MHAβ-gal rVV. Neither virus alone nor an admixture was found to have any statistically significant therapeutic effects. Representative experiments are shown in Fig. 1. However, in seven separate experiments, a significant decrease in the number of pulmonary metastases in MHAβ-gal rVV-vaccinated mice was seen once. Thus, the immune response against β-gal elicited by MHAβ-gal rVV was not sufficient to mediate tumor regression. Furthermore, the addition of B7-1NP rVV did not enhance the therapeutic effectiveness of the recombinant vaccine.

Fig. 1.

An admixture of rVV fails to elicit antitumor immune responses. BALB/c mice (five per group) were given i.v. injections of 5 × 105 CT26.CL25 tumor cells. A, 3 days later, mice were vaccinated i.v. with 107 PFUs B7-1β-gal rVV (B7-1β-gal), MHAβ-gal rVV (MHAβ-gal), B7-1NP rVV (B7-1NP), an admixture of both B7-1NP rVV and MHAβ-gal rVV (107 PFUs each), or HBSS. Mice were randomized and then sacrificed 12 days after tumor injection (A and B). P value reflects comparison between designated group and HBSS; *, P < 0.0001. B, in addition to the experimental groups in A, an admixture of B7-1NP rVV and MHAβ-gal rVV was given in ratios of 3:1, 1:1, and 1:3 (107 PFUs total). P value reflects comparison between designated group and HBSS: *, P < 0.0001.

We hypothesized that the β-gal and B7-1 expressing viruses were simply infecting different cells when administered i.v. To test a scenario in which both viruses were expressed in the same cell, we used a rVV capable of expressing both B7-1 and β-gal, designated B7-1β-gal rVV. Of importance, mice bearing the CT26.CL25 tumor established for 3 days could be effectively treated with B7-1β-gal rVV as measured by the enumeration of pulmonary metastases 12 days later (P < 0.0001; Fig. 1). No significant tumor regression was seen following rVV vaccination in mice bearing CT26.WT tumors (data not shown). These studies, repeated in seven independent but identically performed experiments, demonstrated the requirement that the Ag and costimulatory molecule be expressed by the same infected cell.

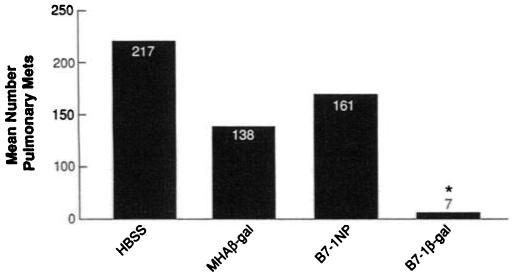

rVV Coexpressing B7-1 and β-gal as Active Immunotherapy in Mice with Tumors Established for Six Days

To explore whether the active immunotherapy results obtained following B7-1 β-gal rVV vaccination were tumor burden dependent, similar experiments were performed in mice bearing tumor established for 6 days. Pulmonary metastases established for 6 days were macroscopically visible with individual metastases measuring up to 1.5 mm. In this stringent assay for the efficacy of recombinant anticancer vaccines, B7-1β-gal rVV vaccination again mediated a significant reduction in the number of pulmonary metastases (P < 0.008; Fig. 2). Mice vaccinated with either MHAβ-gal rVV or B7-1NP rVV achieved no therapeutic benefit compared to HBSS controls (P < 0.19 and P < 0.23, respectively). No significant tumor regression was seen following rVV vaccination in mice bearing CT26.WT tumors. These results indicated that vaccination with a rVV coexpressing both a costimulatory molecule, B7-1, and a TAA was capable of mediating the regression of both large and small tumor burdens in this model system.

Fig. 2.

Vaccination with B7-1β-gal rVV treats tumor established for 6 days. BALB/c mice (five per group) were given i.v. injections of 5 × 105 CT26.WT or CT26.CL25 tumor cells. Three days later, mice were vaccinated i.v. with 107 PFUs B7-1β-gal rVV (B7-1β-gal), MHAβ-gal rVV (MHAβ-gal), B7-1NP rVV (B7-1NP), or HBSS. Mice were randomized and then sacrificed 12 days after tumor injection. All mice inoculated with CT26.WT had large tumor burdens (data not shown). Vaccination with B7-1β-gal rVV mediated a significant reduction in tumor burden compared to all other treatment groups (*, B7-1β-gal rVV versus HBSS, P < 0.008). Duplicate experiments confirmed these results.

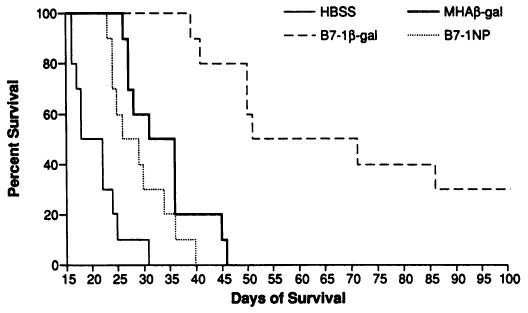

Active Immunotherapy Using rVV Coexpressing B7-1 and β-gal: Survival Studies

To assess whether the reduction in tumor burden observed in mice vaccinated with B7-1β-gal rVV correlated with prolonged survival of tumor-bearing animals, mice given 5 × 105 CT26.WT or CT26.CL25 tumor cells i.v. 3 days earlier were treated with rVV expressing B7-1, β-gal, or both. Regardless of the treatment regimen, all mice inoculated with CT26.WT were dead by day 43 (data not shown). The survival of vaccinated groups of mice bearing CT26.CL25 tumors is shown in Fig. 3. Mice vaccinated with HBSS and those immunized with B7-1NP rVV died by day 39. Mice vaccinated with MHAβ-gal rVV showed a statistically significant prolongation of survival compared to the HBSS group, with 50% of the mice alive at day 27 and the last mouse dying at day 46 (P < 0.0002). A much more pronounced effect was seen in the mice treated with B7-1β-gal rVV: 50% were alive at 70 days and 30% continue to be long-term survivors at over 120 days (B7-1βgal rVV versus HBSS; P < 0.0001). These results demonstrated that the regression of pulmonary metastases following immunization with the B7-1β-gal rVV correlated with increased survival in tumor-bearing animals.

Fig. 3.

Vaccination with B7-1β-gal rVV prolongs the survival of tumor-bearing animals. BALB/c mice (10/group) were given i.v. injections of 5 × 105 CT26.WT or CT26.CL25 tumor cells. Three days later, mice were vaccinated i.v. with 107 PFUs B7-1β-gal rVV (B7-1β-gal), MHAβ-gal rVV (MHAβ-gal), B7-1NP rVV (B7-1NP), or HBSS. Survival was monitored on a daily basis. Vaccination with B7-1β-gal rVV significantly prolonged the survival of mice versus other treatment groups (B7-1β-gal versus HBSS, P < 0.0001). All mice inoculated with CT26.WT were dead by day 43 after tumor injection (data not shown). Duplicate experiments confirmed these results.

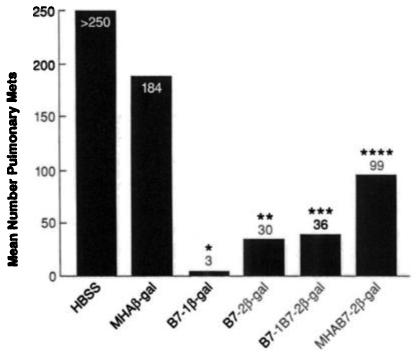

Effects of B7-2 Costimulation on the Function of a rVV Immunogen

Recent evidence indicates that B7-1 and B7-2 costimulatory signals may be functionally distinct (14). However, like B7-1, B7-2 has been shown to evoke enhanced antitumor responses when transfected into immunogenic murine tumors (15). To explore the effects of B7-2 in our model system, rVV encoding B7-2 alone or in combination with β-gal and B7-1 were given to mice bearing tumors established for 3 days.

No significant tumor regression was observed following rVV vaccination in mice bearing CT26.WT tumors. In mice bearing CT26.CL25, treatment with HBSS or MHAβ-gal rVV again had minimal or no therapeutic effect (Fig. 4). As in previous experiments, the B7-1β-gal rVV vaccination resulted in a significant reduction in the number of pulmonary metastases (P < 0.001; Fig. 4). Interestingly, treatment with rVV expressing B7-2 in combination with β-gal (B7-2β-gal rVV, MHAB7-2β-gal rVV, and B7-1B7-2β-gal rVV) resulted in a significant reduction in the number of pulmonary metastases when compared to the HBSS control group (P < 0.0018 for all three groups). B7-1β-gal rVV vaccination elicited a more significant therapeutic response than either B7-2β-gal rVV, B7-1B7-2β-gal rVV, or MHAB7-2β-gal rVV (P < 0.02, P < 0.014, and P < 0.0001, respectively; Fig. 4). In addition, B7-1B7-2β-gal rVV vaccination mediated a significantly greater reduction in pulmonary metastases than MHAB7-2β-gal rVV (P < 0.008), but was not significantly different from the group receiving B7-2β-gal rVV. These studies demonstrated that vaccination with a rVV expressing B7-1 and/or B7-2 with a model TAA was capable of mediating the regression of established tumor and suggests a more potent immune activating role for B7-1.

Fig. 4.

Efficiency of costimulation with B7-1 versus B7-2. BALB/c mice (10/group) were given i.v. injections of 5 × 105 CT26.WT or CT26.CL25 tumor cells. Three days, later, mice were immunized i.v. with either 107 PFU B7-1β-gal rVV (B7-1β-gal), B7-2 β-gal rVV (B7-2β-gal). B7-1B-2β-gal rVV (B7-1B7-2β-gal), MHAB7-2β-gal rVV (MHAB7-2β-gal), MHAβ-gal rVV (MHAβ-gal), B7-1NP rVV (B7-1NP). HBSS. Mice were randomized and then sacrificed 12 days after tumor injection. Lungs were harvested and stained, and pulmonary metastases were enumerated in a blinded fashion. All mice inoculated with CT26.WT had large tumor burdens (data not shown). Mice treated with HBSS alone or B7-1NP rVV showed no therapeutic effect (data not shown). P values reflect comparison between the designated group and the HBSS group; *, P < 0.0014; **, P < 0.0018; ***, P < 0.0018, and ****, P < 0.0018). This figure represents data pooled from two distinct, but identically performed experiments.

DISCUSSION

We have found that the addition of cDNA encoding B7-1 or B7-2 to a recombinant poxvirus encoding the model Ag β-gal significantly enhances its function as an immunogen as measured by reduction in the number of pulmonary metastases or, more important, by the prolongation of survival of tumor-bearing mice. These effects were Ag specific. One explanation for the enhanced in vivo activation of anti-β-gal responses following treatment with rVV expressing co-stimulatory molecules is that infected cells may function as a transient set of “professional” APCs. Since most normal cells express class I molecules, expression of B7-1 or B7-2 could transiently play a role in activating T cells specific for β-gal. Direct infection of tumor cells is an unlikely explanation for these results, since vaccination with B7-1NP rVV did not mediate successful active immunotherapy.

An alternative explanation for the enhancement of the function of the recombinant vaccines expressing Ag and costimulatory molecules is that the rVV may directly infect professional APCs, accelerating the temporal expression of B7 family molecules, generally known to express B7-1 after 48–72 hr and B7-2 after 6 hr after stimulus of the APCs (16). Furthermore, the production of costimulatory molecules that are under the control of powerful viral promoters may also result in increased surface levels on these activating APCs. A number of molecular mechanisms by which B7-1 and B7-2 enhance T-cell activation or function have now been elucidated. Costimulatory signals provided by the B7/CD28 interaction have been shown to prolong T-cell survival by inducing increased expression of the Bcl-xL gene which provides T cells with inherent resistance to apoptotic death (17). In addition, increased interleukin 2 production by these same costimulated T cells provides an additional factor promoting T-cell survival. Prolonged survival of Ag-activated T cells is a potential explanation for the ability of B7-1β-gal rVV-primed lymphocytes to mediate tumor regression on primary adoptive transfer, while MHAβ-gal rVV-primed lymphocytes could not (13). Prolonged survival of TAA-specific T cells would also be of obvious benefit in an active treatment model in which complete regression of tumor burden would depend on the persistence of a large numbers of tumor-reactive lymphocytes.

Current efforts in the laboratory are aimed at exploring the mechanisms of action of these viruses. In one study in which CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subsets were depleted, both lymphocyte subsets were found to be required for the enhanced antitumor reactivity of the rVV. These results confirmed that the regression of established tumor following B7-1β-gal rVV vaccination was T cell mediated, and demonstrated that both CD8+ and CD4+ T lymphocytes were required to mediate maximal therapeutic effect (13).

We acknowledge that the model Ag β-gal is “non-self,” whereas most, but not all, of the human melanoma TAA cloned thus far are nonmutated “self” proteins. Therefore, a fundamental issue facing a vaccine-based immunotherapy of cancer may be the breaking of immunological tolerance against self-Ags. Results obtained in the present set of experiments using β-gal as a model TAA may or may not be reproduced when the TAA is a nonmutated, self-protein, which will presumably induce tolerance. However, the principles drawn from the β-gal model are relevant to other human tumor situations in which TAA can be targeted, which originate from viruses, fusion proteins resulting from translocations, and genetic events that result in totally foreign protein expression such as mutations resulting in frameshifts, translation of intronic information, and the loss of stop codons (18).

An admixture of a rVV expressing B7-1 and the model TAA, respectively, was unable to mediate the regression of established tumor, although such an admixture has been previously reported capable of generating a memory response (8). Differences in the immunogenicity and antigenicity of human CEA and β-gal may provide a partial explanation, although both represent xenogeneic Ags and strain differences (BALB/c versus C57BL/6) may also play a role. Furthermore, while Hodge et al. (8) vaccinated via tail scarification, we administered our recombinants i.v. since far greater Ag-specific T-cell responses are elicited following the i.v. rather than the tail scarification route of administration (19). Furthermore, the antitumor activities of recombinant poxvirus-based vaccines, including the non-replicating recombinant fowlpox, is enhanced by the i.v. route.5 However, since B7-1 and the model TAA need to be expressed in close proximity, i.v. immunization may limit the potential that both rVVs would infect the same or neighboring cells.

We observed that treatment with the double recombinant express ing B7-1 was superior to the function of the virus expressing B7-2 in mediating the regression of established tumor. A deeper understanding of the differential effects of B7-1 and B7-2 could shed light on the cellular and molecular mechanisms involved with tumor rejection. Other workers have found that B7-1 costimulatory pathways play a significant role in the induction and maintenance of CDS+ T-cell responses, whereas CD4+ T-cell responses appear more affected by B7-2 costimulatory pathways (14). Differences in the relative strength of the viral promoter driving β-gal production in B7-1B7-2β-gal rVV (VV 11K) compared to B7-1β-gal rVV and B7-2β-gal rVV (VV 7.5K) does not allow for a direct analysis of the combinations of these two molecules. However, the coexpression of B7-1 and B7-2 (B7-1B7-2β-gal rVV) resulted in enhanced therapeutic effectiveness when compared to a similarly constructed rVV expressing B7-2 alone (MHAB7-2β-gal rVV; Table 1).

Thus, coexpression of a costimulatory molecule, B7-1, and to a lesser extent, B7-2, with the model Ag β-gal significantly enhances the therapeutic efficacy of recombinant poxviruses in the treatment of established tumor. The reagents used in these studies constitute valuable tools for the further exploration of the roles for B7-1 and B7-2 in immune activation. The principles demonstrated in this report and elsewhere point the way to the design of rVV expressing immunostimulatory molecules in combination with TAA for their use in clinical trials (20).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to K. Hathcock, J. Yewdell, and J. Bennink for helpful discussions. We are grateful to D. Jones and P. Spiess for extensive help with the animal experiments, and M. Blalock for expert graphical assistance.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: APC, antigen-presenting cell: rVV, recombinant vaccinia virus; TAA, tumor-associated antigen; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; β-gal, β-galactosidase; PFU, plaque-forming unit; MHA, measles hemagglutinin; VV, vaccinia virus; NP, nucleoprotein; Ag, antigen.

REFERENCES

- 1.June CH, Bluestone JA, Nadler LM, Thompson CB. The B7 and CD28 receptor families. Immunol. Today. 1994;15:321–331. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeman GJ, Gray GS, Gimmi CD, Lombard DB, Zhou LJ, White M, Fingeroth JD, Gribben JG, Nadler LM. Structure, expression, and T cell costimulatory activity of the murine homologue of the human B lymphocyte activation antigen B7. J. Exp. Med. 1991;174:625–631. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.3.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azuma M, Ito D, Vagita H, Okumura K, Phillips JH, Lanier LL, Somoza C. B70 antigen is a second ligand for CTLA-4 and CD28. Nature (Lond.) 1993;366:76–79. doi: 10.1038/366076a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linsley PS, Brady W, Grosmaire L, Aruffo A, Damle NK, Ledbetter JA. Binding of the B cell activation antigen B7 to CD28 costimulates T cell proliferation and interleukin 2 mRNA accumulation. J. Exp. Med. 1991;173:721–730. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.3.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen L, McGowan P, Ashe S, Johnston J, Li Y, Hellstrom I, Hellstrom KE. Tumor immunogenicity determines the effect of B7 costimulation on T cell-mediated tumor immunity. J. Exp. Med. 1994;179:523–532. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Townsend SE, Allison JP. Tumor rejection after direct costimulation of CD8+ T cells by B7-transfected melanoma cells. Science (Washington DC) 1993;259:368–370. doi: 10.1126/science.7678351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hodge JW, Abrams S, Schlom J, Kantor JA. Induction of antitumor immunity by recombinant vaccinia viruses expressing B7-1 or B7-2 costimulatory molecules. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5552–5555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hodge JW, McLaughlin JP, Abrams SI, Shupert WL, Schlom J, Kantor JA. Admixture of a recombinant vaccinia virus containing the gene for the costimulatory molecule B7 and a recombinant vaccinia virus containing a tumor-associated antigen gene results in enhanced specific T-cell responses and antitumor immunity. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3598–3603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang M, Bronte V, Chen PW, Gritz L, Panicali D, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Active immunotherapy of cancer with a non-replicating recombinant fowlpox virus encoding a model tumor-associated antigen. J. Immunol. 1995;154:4685–4692. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blasco R, Moss B. Selection of recombinant vaccinia viruses on the basis of plaque formation. Gene. 1995;158:157–162. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00149-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Earl PL, Moss B. Generation of recombinant vaccinia viruses and their products. In: Ausubel FM, Kinston R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K, editors. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Greene Publishing Associates and Wiley Interscience; New York: 1991. pp. 16.18.1–16.18.10. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith GL, Levin JZ, Palese P, Moss B. Synthesis and cellular location of the ten influenza polypeptides individually expressed by recombinant vaccinia viruses. Virology. 1987;160:336–345. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rao JB, Chamberlain RS, Bronte V, Carroll MW, Irvine KR, Moss B, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. IL-12 is an effective adjuvant to recombinant vaccinia virus-based tumor vaccines. J. Immunol. 1996;156:3357–3365. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gajewski TF. B7-1 but not B7-2 efficiently costimulates CDS+ T lymphocytes in the P815 tumor system in vitro. J. Immunol. 1996;156:465–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang G, Hellstrom KE, Hellstrom I, Chen L. Antitumor immunity elicited by tumor cells transfected with B7-2, a second ligand for CD28/CTLA-4 costimulalory molecules. J. Immunol. 1995;154:2794–2800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lenschow DJ, Su GH, Zuckerman LA, Nabavi N, Jellis CL, Gray GS, Miller J, Bluestone JA. Expression and functional significance of an additional ligand for CTLA-4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:11054–11058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boise LH, Minn AJ, Noel PJ, June CH, Accavitti MA, Lindsten T, Thompson CB. CD28 costimulation can promote T cell survival by enhancing the expression of Bcl-xL. Immunity. 1995;3:87–98. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90161-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boon T, Cerottini J, Van den Eynde B, van der Bruggen P, Van Pel A. Tumor antigens recognized by T lymphocytes. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1994;12:337–365. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.002005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andrew ME, Coupar BE, Boyle DB. Humoral and cell-mediated immune responses to recombinant vaccinia viruses in mice. Immunol. Cell Biol. 1989;67:331–337. doi: 10.1038/icb.1989.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bronte V, Tsung K, Rao JB, Chen PW, Wang M, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. IL-2 enhances the function of recombinant poxvirus-based vaccines in the treatment of established pulmonary metastases. J. Immunol. 1995;154:5282–5292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]