Abstract

Objective

To describe the prevalence and associations of xerostomia among adults in their early thirties, with particular attention to medication exposure as a putative risk factor.

Material and Methods

The prevalence and associations of xerostomia were investigated among 32-year-old participants in a long-standing prospective cohort study. Some 950 individuals were assessed at ages 26 and 32 years, with medications being recorded on both occasions.

Results

The prevalence of xerostomia was 10.0% (with no apparent gender difference), and was significantly higher among those taking antidepressants (odds ratio =4.7), iron supplements (OR =4.1) or narcotic analgesics (OR =2.4). Those taking antidepressants at both ages 26 and 32 years had 22 times the odds of reporting xerostomia.

Conclusion

Xerostomia may be a problem for a sizeable minority of young adults.

Keywords: Longitudinal studies, medications, Xerostomia

Introduction

Xerostomia is the subjective sensation of dry mouth [1], assessed by directly questioning individuals about their experience of the condition. Salivary gland hypofunction (SGH) results in a salivary output (flow rate) which is lower than normal; it can therefore be determined by sialometry, and those with a salivary flow rate below a designated clinical threshold are categorized as having SGH. The degree of concordance between xerostomia and SGH has yet to be satisfactorily established: many of those with symptoms do not have detectably reduced flow rates, while many with SGH are symptomless.

Xerostomia has recently been shown to affect the oral health-related quality of life [2] of those affected. It is likely that this occurs through its effects on important aspects of life such as speaking, the enjoyment and ingestion of food, and the wearing of dental prostheses [3]. The impact on those people’s daily lives lends support to the assertion that dry mouth is an important condition that merits concerted research attention in order to further understanding of how best to treat and prevent it.

Considerable research effort has been focused on the prevalence and associations of xerostomia among older people, of whom approximately one in five report the condition [4]. However, little is known about the condition among younger adults, other than recent Swedish estimates of 19.3% (95% CI 14.3%, 21.1%) and 17.7% (95% CI 15.6%, 23.0%) among 20- and 30-year-olds, respectively [5]. An understanding of the natural history of xerostomia would be enhanced by information on its occurrence among those who have yet to reach old age, because important research questions remain unanswered. For example, the typical age of onset for xerostomia is presently unknown, as is the nature of any antecedent exposures or conditions which are characteristically associated with that onset. Particular medications (termed “xerogenic”) have long been recognized as risk factors for xerostomia among older people [6], but whether this holds among younger adults is currently not clear. Recent US work has suggested that, while aging per se has only a small effect on the diminution of parotid salivary flow rate over time because of the secretory reserve capacity of the salivary system [7], the adverse effect of xerogenic medications over time is much more substantial [8].

At present, the only information on xerostomia among younger people comes from descriptions of clinical samples [9–11], which have the disadvantages of being (i) unrepresentative (and therefore unable to be generalized to the population at large) and (ii) likely to comprise the more severe, less tractable cases [12]. There is a need for information from studies of dry mouth among representative samples of younger adults.

The aim of this study was to describe the prevalence and associations of xerostomia among adults in their early thirties, with particular attention to medication exposure as a putative risk factor.

Material and methods

Participants in the study were members of the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study, a longitudinal study of health and behavior in a complete birth cohort. The Study members were born at the Queen Mary Hospital in Dunedin (New Zealand) between 1 April 1972 and 31 March 1973 [13]. The sample that formed the basis for the longitudinal study was 1,037 children, and they were assessed within a month of their third birthdays. Follow-ups were conducted at ages 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 18, 21, 26, and, most recently, at age 32 years, when we assessed 972 (96%) of the 1,015 study members who were still alive. Participants attended the research unit within 60 days of their birthday for a full day of individual data collection. In order to remove all barriers to participation (such as travel, lost wages, child care), the unit reimbursed the study members’ costs. The various assessments were presented as standardized modules in counterbalanced order, each administered by a different examiner who was not apprised of the responses given in other assessments. Over 90% of the cohort self-identified as being of European origin. Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the Otago Ethics Committee. The current study uses data collected from dental examinations at ages 26 and 32.

Dependent variable

At age 32 years, study members were asked the question “How often does your mouth feel dry?” (response options “Always”, “Frequently”, “Occasionally”, or “Never”). At the analysis stage, those who had responded with “Always” or “Frequently” were designated as “xerostomic” [14]. Salivary flow was not measured because of the lack of time in the busy assessment schedule undertaken by the participants.

Medications

At ages 26 and 32 years, medication data were collected at the time of the general medical examination undergone by Study members. All participants were asked to bring the containers for all medications that they had taken in the previous two weeks, and the details (name of drug, prescription source, and length of duration of exposure) were systematically recorded. Where an individual had forgotten to bring his/her medication, either a follow-up phone call was made, or the person’s recall was relied upon. Specific prompts were not used, and no effort was made to distinguish illicit use from conventional use.

Medical conditions

As part of a general health questionnaire, participants reported whether they had any of the following chronic medical problems at age 32: anemia, hypertension, high cholesterol, cancer, arthritis, diabetes, a heart condition, or epilepsy. The number of medical conditions reported was summed and then grouped for comparison purposes, whereby those who reported no medical conditions were compared with those who reported one or more.

Data analysis

For each of ages 26 and 32, each medication was allocated a 5-digit numeric code using a previously developed medication capture and analysis system [15]. Using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 13.0), count procedures were used to compute the prevalence of medication use by therapeutic category. Exploratory data analysis (automatic interaction detection, using the exhaustive CHAID procedure in the SPSS Answer Tree) was used to identify associations between medication exposure and the prevalence of xerostomia. Differences among mean numbers of medications taken were tested for statistical significance using the Mann-Whitney U-test, while chi-square tests were used for categorical variables. Associations between xerostomia and medications were then examined by using logistic regression to derive ORs adjusted by gender and the reported number of medical conditions. Nagelkerke’s R2 was used to estimate the amount of variance explained by each model.

Results

Dry mouth and medication data were available for 950 (98%) of the 972 study members assessed at age 32. Almost half were female (Table I). There were no gender differences in the responses to the dry-mouth question, for which approximately two-thirds reported dry mouth “occasionally”. One in 10 individuals met the criterion for xerostomia, with no significant gender difference. One or more medications were taken by nearly two-thirds, with more females than males taking one or more medications (most of that difference was accounted for by hormonal contraceptive use). The prevalence of xerostomia was greater among the 308 who were taking two or more medications than the 302 who were taking one only, or the 340 not taking any (14.6%, 10.9% and 5.0%, respectively; χ2 =17.01, df, p <0.0001).

Table I.

Responses to dry-mouth question, prevalence of xerostomia and medication use at age 32 years by gender

| Gender

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| All study members | Males | Females | |

| Total number of participants | 950 | 484 | 466 |

| How often does your mouth feel dry? | |||

| Never (%) | 207 (21.8) | 101 (20.9) | 106 (22.7) |

| Occasionally(%) | 648 (68.2) | 336 (69.4) | 312 (67.0) |

| Frequently (%) | 85 (8.9) | 42 (8.7) | 43 (9.2) |

| Always (%) | 10 (1.0) | 5 (1.0) | 5 (1.1) |

| Xerostomia | |||

| No (%) | 855 (90.0) | 437 (90.3) | 418 (89.7) |

| Yes (%) | 95 (10.0) | 47 (9.7) | 48 (10.3) |

| Medication prevalence | |||

| Number taking none (%) | 340 (35.8) | 224 (46.3) | 116 (24.9)a |

| Number taking one (%) | 302 (31.8) | 147 (30.4) | 155 (33.3) |

| Number taking two or more (%) | 308 (32.4) | 113 (23.3) | 195 (41.8) |

| Number taking any (%) | 610 (64.2) | 260 (53.7) | 350 (75.1) |

| Mean no. taken among medicated sample only (SD) | 1.91 (1.20) | 1.74 (1.09) | 2.04 (1.27)a |

| Median and range | 2 (1–7) | 1 (1–7) | 1 (1–37) |

p <0.05.

The most prevalent categories of medication at age 32 were analgesics, nutrient supplements, hormonal contraceptives, anti-asthma drugs and antidepressants (Table II). While examining the prevalence estimates for each age suggests that the only substantial prevalence changes in any particular category between age 26 and 32 years were for analgesics and antidepressants (both of which increased), the estimates for medications taken at both ages indicate that there had been a considerable change: for example, while the prevalence of nutrient supplements was approximately 16% at each of ages 26 and 32, only about one-third of that group were taking a nutrient supplement at both ages. The prevalence of xerostomia was greater among those taking an iron supplement, a cyclic antidepressant, or an antihypertensive (either a beta-blocker or an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor).

Table II.

Prevalence of the most common medication categories at ages 26 and 32 years (1.0% prevalence or greater at age 32)

| Therapeutic categorya | Number taking at age 26 (%) | Number taking at age 32 (%) | Number taking at both ages (%) | Number reporting xerostomia among those taking it at 32 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analgesics (N02) | 220 (23.2) | 309 (32.5) | 101 (10.6) | 38 (12.3) |

| Hormonal contraceptives (G03A) | 207 (21.8) | 111 (11.7) | 71 (7.5) | 10 (10.5) |

| Nutrient supplements (A11, A12) | 156 (16.4) | 155 (16.3) | 44 (4.6) | 26 (16.8)b,c |

| Anti-asthma drugs (R03) | 106 (11.2) | 85 (8.9) | 55 (5.8) | 11 (12.9) |

| Antihistamines (systemic; R06) | 33 (3.5) | 40 (4.2) | 4 (0.4) | 3 (7.5) |

| Antidepressants (N06A) | 16 (1.7) | 50 (5.3) | 6 (0.6) | 16 (32.0)b,d |

| Antibiotics | 32 (3.4) | 36 (3.8) | 3 (0.3) | 5 (13.9) |

| Antiulcer drugs (A02B) | 5 (0.5) | 16 (1.7) | 1 (0.1) | 3 (18.8) |

| Psychotherapeutics (N05) | 9 (0.9) | 14 (1.5) | 2 (0.2) | 2 (14.3) |

| Anticonvulsants (N03) | 14 (1.5) | 11 (1.2) | 8 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Topical preparations | 45 (4.7) | 17 (1.8) | 4 (0.4) | 1 (5.9) |

| Antihypertensives (C02, C07) | 6 (0.6) | 13 (1.4) | 1 (0.1) | 4 (30.8)b,e |

In parentheses: WHO anatomical therapeutic chemical classification system codes indicating therapeutic subgroup level; where codes are not specified, the category is too diverse to be represented by a single code;

p <0.05;

subcategories responsible: iron supplements (taken by 21, of whom 33.3% reported xerostomia);

subcategories responsible: cyclic antidepressants (taken by 12, of whom 33.3% reported xerostomia);

subcategories responsible: ACE inhibitors (taken by 6, of whom 33.3% reported xerostomia) and beta-blockers (taken by 5, of whom 40.0% reported xerostomia).

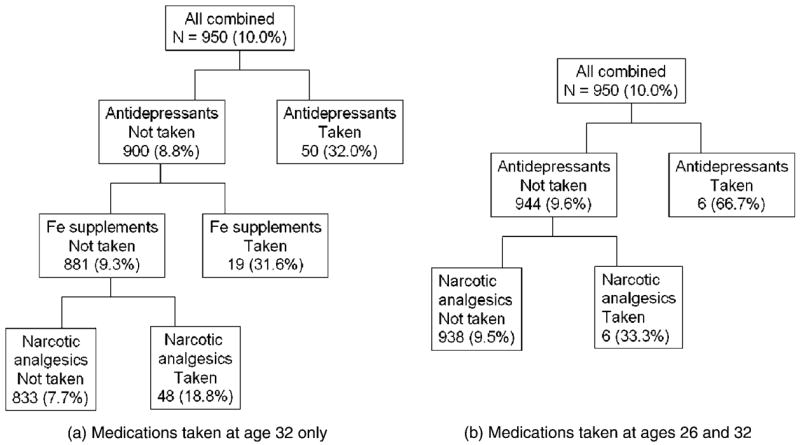

The CHAID analysis revealed that, of the medications taken at age 32 only (Figure 1a), antidepressants accounted for the greatest difference in xerostomia; among those who were not taking antidepressants, taking nutritional iron supplements was the next split, with narcotic analgesics accounting for the greatest difference among those taking neither of the other two. When medications taken at both ages were considered (Figure 1b), antidepressants again explained the greatest difference in xerostomia, with narcotic analgesics accounting for the greatest difference among those not taking them. No splits were found on any of the right-side nodes in either analysis, indicating that medications did not interact in any detectable manner.

Figure 1.

CHAID tree patterns for xerostomia (in each cell, the percentage who were xerostomic is given in parentheses).

No current chronic medical conditions were reported by 841 study members (88.5%), while 93 (9.8%) reported one, 15 (1.6%) reported two, and 1 (0.1%) reported three. Data are presented in Table III on the most prevalent chronic medical conditions, the medications being taken for them, and xerostomia prevalence among individuals with those conditions. The most prevalent medical condition reported was arthritis, followed by high cholesterol and hypertension. The other data enable some determination of whether xerostomia is due to the medication or the underlying condition being treated, because xerostomia prevalence estimates are presented not only for those with the condition and taking the appropriate medication, but also for those without the condition but who were also taking that particular type of medication. There was an apparent association between the medical condition and xerostomia for anemia and arthritis (and possibly for hypertension and heart problems) while there was also an apparent association between the medication and xerostomia for iron supplements, antihypertensive drugs, antineoplastic drugs, and analgesics (and possibly for cardiac drugs).

Table III.

Prevalence of reported medical conditions, specific medications and xerostomia at age 32 years (percentages in parentheses)

| Number | Number of those with xerostomia | Number with the condition taking specific medicationa | Number of those with xerostomia | Number not reporting the condition but taking that medication | Number of those with xerostomia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical condition | ||||||

| Anaemia [9 missing responses] | 17 (1.8) | 4 (23.5) | 5 (29.4) | 3 (60.0) | 16 (1.7) | 4 (25.0) |

| Hypertension [13] | 19 (2.0) | 4 (21.1) | 6 (31.6) | 3 (50.0) | 7 (0.7) | 1 (14.3) |

| High cholesterol [14] | 24 (2.5) | 5 (20.8) | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Cancer [3] | 1 (0.1) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (0.7) | 2 (28.6) |

| Arthritis [0] | 35 (3.7) | 7 (20.0) | 16 (45.7)b | 2 (12.5) | 293 (30.8) | 36 (12.3) |

| Diabetes [0] | 5 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.3) | 1 (33.3) |

| Heart condition [1] | 18 (1.9) | 6 (33.3) | 1 (5.6) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Epilepsy [0] | 7 (0.7) | 1 (14.3) | 4 (57.1) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) |

Medication specific to the condition; for example, 17 individuals reported having anemia, and 4 of those had xerostomia; of the 5 with anemia who were taking medication (an iron supplement) for this condition, 60.0% had xerostomia. Interestingly, 16 individuals were taking an iron supplement but did not report having anemia; of those, 25.0% reported xerostomia (which is still considerably higher than the 10.0% overall prevalence of xerostomia).

Analgesics.

The logistic regression model (Table IV) shows that, after controlling for gender and the number of reported medical conditions, those taking an antidepressant or iron supplement at age 32 had more than 4 times the odds of having xerostomia, while those taking narcotic analgesics had more than twice the odds. The second model indicated that those who were taking antidepressants at both 26 and 32 had 22 times the odds of reporting xerostomia at age 32. Neither model explained much of the variance in xerostomia (11% and 7%, respectively; Table IV).

Table IV.

Logistic regression models for xerostomia prevalence

| Model 1. Medications taken at age 32 onlya Odds ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| Female | 0.83 (0.53, 1.31) |

| Taking antidepressants | 4.72 (2.40, 9.26) |

| Taking iron supplements | 4.09 (1.46, 11.49) |

| Taking narcotic analgesics | 2.36 (1.17, 4.75) |

| Number of medical conditions | 2.27 (1.49, 3.44) |

| Model 2. Medications taken at ages 26 and 32b | |

| Female | 0.92 (0.63, 1.51) |

| Taking antidepressants | 22.37 (3.52, 142.11) |

| Taking narcotic analgesics | 0.99 (0.12, 7.99) |

| Number of medical conditions | 2.37 (1.58, 3.55) |

Nagelkerke R2 =0.10;

Nagelkerke R2 =0.06.

Discussion

It is not known how typical the xerostomia prevalence estimate of 1 in 10 in this study actually is, because there has been only one previous report from a population-based sample of young adults. The 17.7% (95% CI 15.6%, 23.0%) estimate reported for Swedish 30-year-olds in 1997 is higher, but the question used in that study [5] differed not only in content (“Does your mouth usually feel dry?”) but also in using a dichotomous response option, making direct comparison difficult. Interestingly, our estimate is approximately half that typically reported from epidemiological studies of older adults [4], suggesting that – assuming no resolution of cases – the other 10% characteristically observed among the latter accrues some time in the following three decades or so. Whether it does so incrementally or in sizeable quanta can only be resolved by long-term prospective studies such as the current one and that reported by Ghezzi et al. [8].

Another important difference from the findings of studies of older people is that no appreciable gender difference was observed in the current study. It may be that xerostomia develops incrementally at different rates among males and females (perhaps as a result of persistent, life-long gender differences in exposure to xerogenic medications), or that a major life change (perhaps the female menopause) is responsible for a large increase among females once they reach middle age. The Dunedin study members had a clear gender difference in medication exposure at age 26 [16] which was still apparent at age 32, yet there was no concomitant gender difference in xerostomia. It may be that they are not yet taking enough xerogenic medications (particularly in view of the gender difference in medication prevalence at this age being largely due to the use of hormonal contraceptives, which are not known to be xerogenic), or that their exposure to those has not yet been long enough. Future phases of this study will assist in clarifying this issue.

Before discussing the association between medications and xerostomia prevalence, it is appropriate to justify the analytical approach. We attempted to allow for polypharmacy by using an analytical strategy which has been previously reported only twice in this field [17,18]. Automatic Interaction Detection (AID) is one of a number of techniques that fall under the rubric of exploratory data analysis, an approach which has been advocated as a sound exploratory complement to classical multivariate procedures, particularly for data sets (such as that used in the current study) which may be large, complicated systems of numerous inter-related variables [19]. There is no doubt that a medication data set meets that particular criterion. Considering that the literature on medications and dry mouth is not very informative [4], the hierarchical approach and systematic, exploratory nature of AID analysis appeared to be useful as a preliminary analytical step towards identifying potential predictor medications (and combinations thereof) because it precluded the need for a priori formulation of hypotheses.

The association of xerostomia prevalence with medications was a largely predictable one, with the well-known anticholinergic effects of antidepressants and narcotic analgesics being manifest. However, the strong association with the taking of pharmacological-dose iron supplements was unexpected and more difficult to account for. The symptoms of hypogeusia and burning mouth have been reported to be associated with iron deficiency [20,21]; these have also been related to xerostomia [22], and it may be that the association observed in this study was a manifestation of the condition being treated rather than of the therapy itself. This, of course, may also apply to the other observed associations: for example, was the xerostomia observed among those on antidepressants caused by the medication or the condition? It is not possible to answer this question in the current analysis, but future assessments of the Dunedin study participants as they grow older may help in this respect.

It is also noteworthy that polypharmacy did not appear to be detectable as a determinant of xerostomia prevalence in the current study (as witnessed by the absence of splits on the right-hand side of Figures 2a or 2b) other than at the level of the overall number of medications being taken, but was observed in a population of older South Australians [18]. This is most likely due to differences between the two populations with respect to overall medication usage.

The data in Table III were presented in order to allow consideration of the question of whether the observed xerostomia was due to the medication, the underlying condition for which medication has been given, or some combination of these. While there was an apparent association between the medical condition and xerostomia for a small number of conditions, an apparently direct association was also observed between the medication and xerostomia for a number of types. It therefore seems that the issue is not readily resolved, and that the association may be due to either mechanism (or both), depending on the medication and the condition being treated.

In summary, xerostomia was reported by one in ten 32-year-olds (with no gender difference), and was more prevalent among those taking antidepressants, narcotic analgesics, or iron supplements.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant R01 DE-015260-01A1 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA, and a programme grant from the Health Research Council of New Zealand. The study members, their families and their friends are thanked for their continuing support. The Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Research Unit is supported by the Health Research Council of New Zealand.

References

- 1.Fox PC, Busch KA, Baum BJ. Subjective reports of xerostomia and objective measures of salivary gland performance. J Am Dent Assoc. 1987;115:581–4. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8177(87)54012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Locker D. Dental status, xerostomia and the oral health-related quality of life of an elderly institutionalized population. Spec Care Dentist. 2003;23:86–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2003.tb01667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cassolato SF, Turnbull RS. Xerostomia: clinical aspects and treatment. Gerodontology. 2003;20:64–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2003.00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomson WM. Issues in the epidemiological investigation of dry mouth. Gerodontology. 2005;22:65–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2005.00058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nederfors T, Isaksson R, Mörnstad H, Dahlöf C. Prevalence of perceived symptoms of dry mouth in an adult Swedish population: relation to age, sex and pharmacotherapy. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1997;25:211–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1997.tb00928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Porter SR, Scully C, Hegarty AM. An update of the etiology and management of xerostomia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004;97:28–46. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2003.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghezzi EM, Ship JA. Aging and secretory reserve capacity of major salivary glands. J Dent Res. 2003;82:844–8. doi: 10.1177/154405910308201016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghezzi EM, Wagner-Lange LA, Schork MA, Metter EJ, Baum BJ, Streckfus CF, et al. Longitudinal influence of age, menopause, hormone replacement therapy, and other medications on parotid flow rates in healthy women. J Gerontol Series A–Biolog Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M34–42. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.1.m34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Field EA, Fear S, Higham SM, Ireland RS, Rostron J, Willetts RM, et al. Age and medication are significant risk factors for xerostomia in an English population, attending general dental practice. Gerodontology. 2001;18:21–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2001.00021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGrath C, Chan B. Oral health sensations associated with illicit drug abuse. Br Dent J. 2005;198:159–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4812050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore PA, Guggenheimer J, Etzel KR, Weyant RJ, Orchard T. Type 1 diabetes mellitus, xerostomia, and salivary flow rates. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;92:281–91. doi: 10.1067/moe.2001.117815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen P, Cohen J. The clinician’s illusion. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984;41:1178–82. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790230064010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silva PA, Stanton WR. From child to adult: the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study. Auckland: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomson WM, Chalmers JM, Spencer AJ, Ketabi M. The occurrence of xerostomia and salivary gland hypofunction in a population-based sample of older South Australians. Spec Care Dentist. 1999;19:20–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1999.tb01363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomson WM. A medication capture and analysis system for use in epidemiology. Drugs Aging. 1997;10:290–8. doi: 10.2165/00002512-199710040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomson WM, Poulton R. Medications taken by 26-year-olds. Intern Med J. 2002;32:305–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-5994.2002.00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson G, Barenthin I, Westphal P. Mouth dryness among patients in long-term hospitals. Gerodontology. 1984;3:197–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.1984.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomson WM, Chalmers JM, Spencer AJ, Slade GD. Medication and dry mouth: findings from a cohort study of older people. J Public Health Dent. 2000;60:12–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2000.tb03286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stewart PW, Stamm JW. Classification tree prediction models for dental caries from clinical, microbiological, and interview data. J Dent Res. 1991;70:1239–51. doi: 10.1177/00220345910700090301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osaki T, Ohshima M, Tomita Y, Matsugi N, Nomura Y. Clinical and physiological investigations in patients with taste abnormality. J Oral Pathol Med. 1996;25:38–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1996.tb01221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bergdahl J, Anneroth G, Anneroth I. Clinical study of patients with burning mouth. Scand J Dent Res. 1994;102:299–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1994.tb01473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grushka M. Clinical features of burning mouth syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;63:30–6. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(87)90336-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]