Abstract

The process of rural-to-urban migration in China is accelerating with increased modernization and industrialization. To address the issues of health outcomes and geographic mobility among this population, data from 4,208 rural-to-urban migrants in two major metropolitans of China were analyzed. Results indicate that average duration of migration was 4.3 years, with younger migrants being more mobile than their older counterparts. After controlling for possible confounders, increases in mobility were associated with unstable living arrangements, substandard employment conditions, suboptimal health status, inferior health-seeking behavior, elevated level of substance use, depressive symptoms, and expression of dissatisfaction with life and work. The findings in the present study underscore the need for improved living and employment conditions and increased health care services available to rural-to-urban migratory population.

Keywords: China, general health, health-seeking, migration, mobility

Introduction

A substantial global literature suggests that migration is associated with an increased risk for poor health (McKay, Macintyre, & Ellaway, 2003). This increased risk may be related to such contextual and psychosocial factors as adopting a new socio-cultural environment, coping with changes in traditions and lifestyles, dealing with economic transitions, and overcoming barriers to gain access to local community services including heath care delivery. Previous research has documented that stigmatization causes anxiety which may contribute to mental and physical illnesses (Darmon & Khlat, 2001; Pudaric, Sundquist, & Johanson, 2000). The existing literature on the relationship between migration and health has largely been limited to migrants within the United States and European countries, and those seeking permanent resettlements, such as trans-culture or trans-country immigrants and war refugees (Darmon & Khlat, 2001; Diaz, Ayla, Bein, Henne, & Marin, 2001; Pernice & Brook, 1996; Pudaric et al., 2000). In contrast, there is limited data available regarding the relationship between migration and health status among temporary, rural-to-urban migrants in many developing countries, including China, which houses one-fifth of the world’s population.

Migration from rural to urban areas was restricted in China through the official household registration (“hukou”) system for almost a quarter century until economic reform took place in the late 1970’s (Zhang L, 2001). Under the “hukou” system, each individual is officially registered as either a rural or an urban resident. Rural residents could not freely move to or settle in urban areas in order to become urban residents. With the introduction in 1979 of the Rural Household Contract Responsibility System, a form of rural economic reform, China experienced rapid growth in agricultural productivity (e.g., agriculture GDP increased from 2.7% in 1970–1978 to 7.1% in 1979–1984) (Anderson, Huang, & Ianchovichina, 2003) and a subsequent surplus of rural labor (e.g., agriculture labors decreased from 81% in 1970 to 49% in 2000) (Anderson et al., 2003). Concurrently, rapid economic growth in urban China widened the income gap between the urban and rural areas to a historically high level in the 1990s (Anderson et al., 2003). This increasing income gap has provided a strong incentive for rural residents to migrate to urban areas in search of employment opportunities and better lives. Consequently, millions of Chinese farmers have left their villages to cities, forming the rural-to urban migration, one of the largest internal migrations in China’s recent history (Zhang L, 2001).

According to the recent Chinese governmental statistics, there are approximately 114 million rural-to-urban migrants in China, accounting for 23.2% of total rural labor and 9% of the total population in China (CNBS, 2003). The rural-to-urban migrants were individuals who moved from rural areas to urban areas for jobs. These migrants work or live in urban areas without official urban household registration (i.e., urban “hukou”). Most of these migrants come from the poor rural areas in interior provinces, to form a general geographic pattern of migration from the middle and western parts of China to the eastern and costal regions, where economic development was more advanced. Because of existing legal restrictions on employment and housing in urban areas, approximately 80% of the migrants do not permanently relocate (e.g., obtaining official urban “hukou”) (Zhang L, 2001).

While the current magnitude of the rural-to-urban migration is already substantial, China is facing an anticipated increase of rural-to-urban migration in the coming years because of several salient socioeconomic factors. Both the rural-urban income disparity and the rural labor surplus have continued to rise in China in recent years. Approximately 70% of the Chinese population live in rural areas. One-quarter of rural Chinese households lived on less than one US dollar a day in 1999, compared to only one percent of urban households in the same economic condition (Anderson et al., 2003). When China became a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2002, part of China’s obligation to the WTO was to decrease the duties on imported farm produce from 22% in 2001 to less than 15% after the phase-in period and to permanently eliminate some quotas of agriculture product imports (Anderson et al., 2003). As a result, Chinese agriculture production will decrease and the surplus of rural labor will increase. With a simultaneous increase of labor needs of urban industries, more rural-to-urban will be expected to migrate to urban areas.

In addition, the Chinese government has gradually been relaxing its control on rural to urban population-movement. Until recently, there had been strong government control over rural-to-urban migration. For example, there have been several institutionalized barriers for migrants in seeking legitimate employment in urban areas, including the government’s restriction on specified industries and corporations to employ migrants. For example, the Beijing municipal government published annual guidelines permitting or restricting certain occupations to employ migrants. In 1999, the list contained at least 36 “restricting” occupations that include telephone operators, store salesclerks, bus drivers and conductors, box-office clerks, warehouse clerks, and hotel attendants (Li, Stanton, Fang, & Lin, 2005). The cumbersome and costly administrative procedures required of migrants rendered it difficult to obtain the necessary permits for legitimate employment in cities. Rural migrants were required to pay as many as 12 different fees to local government and obtain up to six governmental registrations or permits for employment (Li et al., 2005). It normally took migrants at least three months and costs them from 500 to 1,000 Yuan (about one month salary) to obtain all of the required registration and permits for employment (most of which need to be renewed annually). Failing to obtain these registrations and permits had significant consequences. Migrants without the temporary residency permit were considered to be “illegal migrants” and subjected to incarceration and/or deportation by the urban public security agencies. Because of the increasing societal concern about the welfare of the migrants and increasing social tension between migrants and urban residents, both central and local governments have started to relax some regulations on rural-to-urban migration. For example, the Beijing government abolished the employment restriction in 2001 and waived some mandatory fees in 2002. The deportation law was abolished nationwide in June 2003 in response to the brutal death of a young college graduate arrested and placed in custody by local police as an “illegal migrant”. While it is too early to evaluate the actual impact of these regulatory changes on the well-being of migrants in cities, the changes certainly will encourage new waves of rural-to-urban migration.

Given the size of this mobile population movement and the likelihood that this process will accelerate as modernization and industrialization proceeds, the health status and access to health care of this migratory population has become a significant public health issue in China. In moving from the rural to the urban context, migrants also encounter a rapid change of working and living conditions, a weakening of family supports, and a fragmentation of their social support network that may negatively impact their well-being and health status (Diaz et al., 2001; Gao, Tang, Tolhurst, & Rao, 2001; Huang, 2000; Pernice & Brook, 1996; Stafford, 1986; Tie, 1999; Ying, 2003,). In addition, the health care infrastructure in China may not be sufficient to provide adequate health care to migrants. Along with extreme expansions of economic opportunities for the country, China’s health care system has undergone substantial reconstruction since 1978, when the country began moving from a planned economy to a market economy.

The primary objective of the medical reform in the 1980s was cost recovery for the hospitals and other health care providers (Bogg, Dong, Wang, Cai, & Winod, 1996). Parallel to its residence registration system, there have been separate health service systems for rural and urban residents. About 80% of the country’s total health budget is relocated to funding hospital-based treatment in the urban areas, although the urban residents account for just 30% of the country’s population (Zhang, W, 2001). For the rural population, the affordable and generally effective cooperative health insurance reached a peak in the middle 1970s when nearly 90% of the rural population was covered. In the 1980s, rural cooperative health insurance collapsed and the coverage fell to only 5% in 1989 (Bogg et al., 1996; Grogan, 1995). Virtually all rural residents must now pay for their health care out of their own pockets, at the point of service. The urban population, which used to be protected by governmental health insurance, has been covered primarily by employment-based health financing since 1980s (Grogan, 1995). The Chinese government’s efforts to commercialize and privatize many health services have stressed the capabilities of many rural and urban health institutions, causing substantial and frequently unaffordable increase in the direct cost to patients. In both the rural and urban areas, health care is becoming a fee-for-service commodity which is more available to the rich than the poor. As a result, access to health care is declining in many sectors of the population (Lampton, 2003; Smith, 1998). A recent study in China found that among those in the lowest income bracket who reported illness, 70% did not obtain treatment because of financial difficulty (Gao et al., 2001). Because of the temporary and informal nature of their employment, most migrants who arrive in cities without any health care insurance, are not entitled to many of the privileges and benefits available to their urban counterparts, including health care coverage (Li et al., 2005; Zhang L, 2001). For example, only 22.5% of female migrants in Beijing received any maternal health or family planning education, compared to almost 100% of urban residents (Zheng et al., 2002).

Even though the proportion of the rural-to-urban migrants is substantial (about 9% of the total Chinese population and 13% of the population aged 15 to 64 years), little attention has been paid to the health risk and health-seeking behaviors of these Chinese migrants. Therefore, the current study, utilizing cross-sectional data from 4,208 migrants residing in two large metropolitan areas in China, was designed to explore the association of increased geographic mobility with indices of health status and health-seeking behaviors among rural-to-urban migrants. An increasing geographic mobility is defined as a more frequent movement in relation to the duration of migration. We hypothesized that the mobility of rural-to-urban migrants would be positively associated with (1) substandard living (e.g., unstable dwelling arrangement, poor living condition); (2) worsened employment (e.g., less pay, long working hours, more working days, and high frequency of changing job); (3) suboptimal health condition; (4) reduced health-seeking behaviors; (5) elevated substance use behaviors (e.g., tobacco use and alcohol consumption); and (6) increased mental health symptoms (e.g., depressive symptoms, life dissatisfaction).

Methods

Survey Sites and Participants

Data were collected from migrants residing in Beijing and Nanjing, China in 2002. Beijing and Nanjing are two cities 1,200 kilometers apart. According to the China 2000 Census Data, Beijing (the capital of China) has a population of 13.82 million urban residents and 3 million (22%) rural-to-urban migrants. Nanjing (the provincial capital of Jiangsu), has a population of 6.2 million urban residents and 800,000 (13%) rural-to-urban migrants.

The study sample was comprised of respondents who participated in a HIV/STD prevention feasibility study among rural-to-urban migrants in China. The details regarding sampling methodology and outreach procedures are described elsewhere (Li et al., 2004). Briefly, ten occupational clusters and job markets (for migrant job seekers) were selected as the sampling frame for participant recruitment. The occupational clusters that employed more than 90% of the migrants include restaurants, barbershops/beauty salons, bath houses, dance halls/bars, construction companies, street venders, small retail shops, hotels, domestic services, and factories. Participants were recruited from their workplaces or job markets using a “quota-sampling” procedure such that the number of participants recruited in each occupational cluster was approximately proportional to the overall estimated distribution of migrants in the cluster.

Survey Procedures

Data were collected employing the “Migrant Health Behavior Survey”, a self-administered questionnaire developed through the joint efforts of investigators both in China and the Unites States. The questionnaire was pilot-tested for comprehension among young migrants in China and was considered to be a culturally appropriate assessment tool (Li et al., 2004). Over the course of a 45-minute session, participants completed the survey individually or in a small group (3–5 people) at worksites or public locations appropriate for survey administration. Trained data collectors provided assistance to a small number of participants (approximately 20) with limited literacy by reading survey items to them. Respondents were provided with small monetary compensation for their participation. The Institutional Review Boards at West Virginia University and Wayne State University in the United States as well as Beijing Normal University and Nanjing University in China approved the study protocol.

Measures

Demographic measures

Variables used for measuring demographic characteristics included age, gender, and education attainment (no formal education, grades 1–6, grades 7–9, grades 10–12, and post-secondary education). Ethnicity (Han, Hui, Man, Mongolian, and others) was also assessed, but since respondents with an ethnic background other than Han (the nation’s ethnic majority) consisted of only 3% of the survey sample, they were grouped into a single category as non-Han for data analysis in the current study.

Mobility

Participants were queried about the entire duration of migration (in years) and the number of cities to which they had ever migrated. The correlation between these two variables was 0.41 (p<.01). A ratio of the number of migratory cities to the total migration years was used as an index of mobility for each respondent. The mobility index ranged from 0.06 to 12.5 with a greater number indicating a higher level of geographic mobility (e.g., more frequent movement in relation to the duration of migration).

Living conditions

Three items were employed to assess current living conditions: (1) type of residence in the city (apartment building, flat house, underground storage space, and work shed); (2) frequency of changing residence (never, once every 2–3 years, once per year, at least 2–3 times per year); and (3) availability of basic utilities in the dwelling (e.g., toilet, kitchen, city water, gas/cylinder, telephone, TV set, shower or bath tub). To quantify living conditions, a composite score was created by indexing respondents who lived in a substandard residence (e.g., lived in an underground storage space or a work shed), lacked basic utilities in the dwelling (e.g., having no more than half of the eight utilities identified), and changed residence at least 2–3 times a year. The resultant living condition composite score consisted of values of 0, 1, 2 and 3 and was reversely coded, so that greater numbers indicated better living conditions.

Employment conditions

Five items were employed to assess general employment conditions. Participants were first asked two general questions: (1) How many different jobs have you had since you migrated to cities? (2) Where are you working now (e.g., restaurant, beauty saloon/barber, bathhouse/sauna center/massage, dance hall/karaoke/bar, construction, street vender, small store/shop, hotel, domestic service, factory, or no job)? Respondents who identified themselves as being currently employed (or self-employed) were queried further about average hours worked per day, average monthly income (in Chinese currency Yuan), and days off per month. A composite score of employment condition was created by indexing respondents who had worked more than 3 different jobs in the past, had unstable employment or were self-employed (e.g., street vender, small store/shop, domestic service), had monthly income below the 25 percentile of the sample (e.g., 500 Yuan), worked at least 10 hours per day, and had less than 4 days off per month. The final employment score consisted of values 0 through 5 and was reversely coded so that a higher score indicated a better employment condition.

General Health Condition

Nine items were employed to measure the general health condition of the study population. These items were developed by modeling items from the SF-12 Health Survey (Ware, Kosinski, & Keller, 1996) in the Chinese setting. The items assessed participants’ general health conditions (from poor to excellent), limitations and effects of their health conditions (both physical and emotional) on their daily work and social life in the past month. The Cronbach alpha for the nine items was 0.66. A composite health score was created by indexing those participants who reported poor health and severe limitations in their work productivities and daily life because of physical and emotional problems. The composite index was reversely coded and ranged from 1 to 9 with a higher score indicating a better health condition.

Health-seeking behaviors

Following a general question about how often the participant became ill in cities on a 5-point scale (e.g., 1=never, 5=always), participants were asked additional questions assessing health-seeking behaviors in the event of an illness (e.g., do nothing, self-treatment, go to hospital, go to regular clinics, or go to underground clinics). Participants were also asked whether they ever had a physical checkup and if they had access to health care facilities near their workplaces or residence in cities. A composite score was created by indexing respondents who did nothing or self-treated for illness; never received any physical checkup; or had no knowledge about a health care facility nearby. Again, the composite score was reversely coded so that a higher score indicated a greater tendency of health-seeking behavior. In addition, the participants were queried about the possible reasons for not seeing a doctor when they became ill.

Substance use

Data on substance use were comprised of information on cigarette and alcohol consumption. Participants were asked how many cigarettes they had smoked each day during the previous month (did not smoke, 1–5 cigarettes, 6–10 cigarettes, 11–15 cigarettes, 16–20 cigarettes, and more than a pack). In addition, participants were asked how many times they were intoxicated with alcoholic beverage during the previous month (none, once, twice, three times, and at least 4 times). A composite score was created by indexing respondents who smoked at least half a pack a day during the previous month and were intoxicated at least once in the previous month. The composite score consisted of values 0 through 2, with a higher score indicating a higher level of substance use.

Depression

Depressive symptoms were measured using the Center of Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977). The 20-item CES-D was introduced into China in the early 1990s (Wang, 1993). The existing Chinese version of the CES-D was modified by the investigators to ensure the accuracy of the translation. The modified scale was found to have high reliability for the current study sample (Cronbach’s alpha= 0.85). The scale scores ranged from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating higher frequency of depressive symptoms.

Life satisfaction

A scale comprised of two questions was used to assess participants’ general satisfaction with their current life or employment on a 5-point scale (1=very dissatisfied, 5=very satisfied). The scale was found to have adequate reliability for the current study (Cronbach’s alpha=0.75). The mean score of the two items was retained as an overall life satisfaction index. For those respondents who were unemployed, only the life satisfaction score was employed as the index in the analysis.

Statistical analysis

Overall distributions of all measures by gender were assessed using Chi-square test for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables. Associations between mobility index and health-related measures were examined using multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA). The mobility index was used as the main between-subjects factor. To categorize the mobility index into a between-subjects factor in the MANCOVA model, the sample was divided into five groups using the 20th, 40th, 60th, 80th percentiles of the mobility index as thresholds. Because mobility can be potentially confounded by age, gender, marital status, and level of education attainment, these factors were included in the MANCOVA model either as additional between-subjects factors (e.g., gender, marital status) or covariates (e.g., age, education attainment). Pillais F test (Stevens, 1996) was used for evaluating multivariate significance. The conventional F test was used for univariate testing. The t statistic was used to assess the significance of covariates.

Results

Sample Characteristics

A total of 4,301 migrants were approached for the survey, of whom 24 (0.6%) refused to participate (10 from Beijing and 14 from Nanjing). Sixty-nine additional respondents were excluded from the database either because of substantial missing data (e.g., more than half of the variables were missing) or missing data on key variables (e.g., gender). The final sample consisted of 4,208 respondents (Table 1), with 53% being from Beijing and 47% from Nanjing. Of the total sample, 40% were female, 60% were male, and the mean age was 23.5 years (SD=3.8). The majority of the respondents were of Han ethnicity (97%), single (72%), and had at least some elementary school level education (94%). Male respondents were 1.12 years older than female respondents (p<.01) and significantly more females than males (77% versus 68%, p<.01) were single.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and living condition of 4,208 rural-to-urban migrants in China

| Overall | Female | Male | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N(%) | 4208(100%) | 1699(40%) | 2509(60%) |

| Mean age (yr) | 23.49(3.80) | 22.82(3.55) | 23.94(3.90)**** |

| Total yrs of migration | 4.29(3.05) | 3.48(2.42) | 4.84(3.30)**** |

| Han Ethnicity | 4053(97%) | 1623(96%) | 2430(97%)* |

| Single | 2921(72%) | 1275(77%) | 1646(68%)**** |

| Education attainment1 | |||

| ≤6 | 252(6%) | 131(8%) | 121(5%) |

| 7–9 | 2313(56%) | 849(51%) | 1464(59%) |

| 10–12 | 1372(33%) | 598(36%) | 774(31%) |

| >12 | 231(6%) | 103(6%) | 128(5%) |

| # of cities migrated1 | |||

| One | 1725(42%) | 911(54%) | 814(33%) |

| Two | 1152(28%) | 489(29%) | 663(27%) |

| Three | 668(16%) | 178(11%) | 490(20%) |

| Four | 295(7%) | 59(4%) | 236(10%) |

| ≥Five | 309(7%) | 42(2%) | 267(11%) |

| Site of residence1 | |||

| Building | 1349(32%) | 702(42%) | 647(26%) |

| Flat | 1855(44%) | 672(40%) | 1183(47%) |

| Underground | 515(12%) | 239(14%) | 276(11%) |

| Shelter | 348(8%) | 29(2%) | 319(13%) |

| Other | 126(3%) | 50(3%) | 76(3%) |

| Utilities in dwelling | |||

| Toilet | 2434(58%) | 1112(66%) | 1322(53%)**** |

| Kitchen | 1896(45%) | 779(46%) | 1117(45%) |

| Running water | 3617(86%) | 1521(90%) | 2096(84%)**** |

| Gas | 1767(42%) | 769(46%) | 998(40%)**** |

| Telephone | 1400(33%) | 638(38%) | 762(31%)**** |

| TV set | 2290(55%) | 960(57%) | 1330(53%)* |

| Shower/bathtub | 1710(41%) | 733(43%) | 977(39%)** |

| None of the above | 347(8%) | 90(5%) | 257(10%)**** |

| Frequency of changing site of residence1 | |||

| Never | 1906(44%) | 852(51%) | 954(39%) |

| once 2–3 years | 551(13%) | 222(13%) | 329(13%) |

| once per year | 776(19%) | 295(18%) | 481(20%) |

| ≥2–3 times per year | 996(24%) | 298(18%) | 698(28%) |

Note: Responses were significantly differ by gender (p<.0001).

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.0001

Mobility

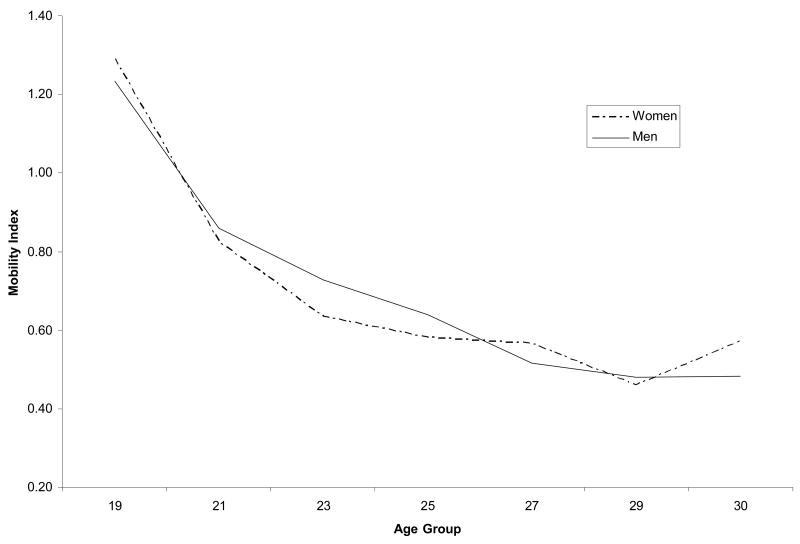

As shown in Table 1, respondents had an average migration history of 4.29 years (SD=3.05). More than half (58%) had migrated to two or more cities and 30% had migrated to three or more cities. There was no gender difference in the mobility index between genders (mobility index =0.76 for women versus 0.72 for men). While men tended to move more frequently than women from one city to another (e.g., 67% men versus 46% women had migrated to two or more cities, p<.01), men also had a longer migratory history than women (4.84 years versus 3.48 years, p<.01). As shown in Figure 1, the mobility index significantly differed by age with younger migrants being more mobile. In addition, the mobility index differed by marital status with those migrants who had never been married being more mobile than those who were married (0.83 versus 0.52, p<.0001). The association between mobility index and marital status was consistent across gender (e.g., the mobility index was 0.83 for unmarried women and 0.53 for married women; 0.83 for unmarried men and 0.51 for married men).

Figure 1.

Association between age and mobility among Chinese rural-to-urban migrants

Description of health indicators

Living arrangement

As shown in Table 1, 76% of the respondents reported living in apartment buildings or flat houses, 12% in underground storage spaces, and 8% in work sheds/shelters. Eighty-six percent reported that their dwellings were equipped with tap water; 58% with a toilet; 45% with a kitchen; 42% with gas line or cylinder; 33% with a telephone; 55% with a TV set; and 41% with a shower or bath tub. Eight percent reported that they had none of the seven basic utilities/equipments listed above in their residence. Approximately one-quarter of the respondents reported changing their residence at least 2–3 times a year.

More women than men lived in apartment buildings (42% versus 26%), and more men than women lived in work sheds (13% versus 2%, p<.01). More women than men had access to telephones, city water, gas, and shower/bathtub, and women in general tended to stay longer than men in the same residence (51% versus 39% never moved, p<.01).

Employment conditions

Nearly all of the respondents (96%) were currently working (or “earning money”). Whereas 67% had worked two or more jobs since migrating to the city, only 2% reported having never been employed. Distribution of the migrants who were currently working by job location is presented in Table 2. Approximately half of the respondents worked in three occupation sectors (18% in construction companies, 17% in restaurants, and 13% in barbershop or beauty salon) and less than one-tenth worked in domestic services (4%) or retail (2%). The average monthly income for all respondents was 878 Yuan (equivalent to $110 with the current exchange rate) ranging from zero to 12,000 Yuan per month. On average, migrants worked 10 hours per day, and received approximately 3 days off per month.

Table 2.

Employment situation of rural-to-urban migrants in China

| Gender | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Female | Male | |

| How many jobs you have had1 | |||

| None | 75(2%) | 31(2%) | 44(2%) |

| One | 1309(31%) | 584(35%) | 725(29%) |

| Two | 1263(30%) | 539(32%) | 724(29%) |

| Three | 907(22%) | 354(21%) | 553(22%) |

| Four | 312(8%) | 102(6%) | 210(8%) |

| ≥Five | 310(7%) | 78(5%) | 232(9%) |

| Place of current employment1 | |||

| No job | 149(4%) | 54(3%) | 95(4%) |

| Restaurant | 709(17%) | 345(20%) | 364(15%) |

| Beauty Parlor | 548(13%) | 337(20%) | 211(9%) |

| Bath house/message parlor | 350(8%) | 210(12%) | 140(7%) |

| Dance Hall/Bars | 234(6%) | 210(6%) | 136(6%) |

| Construction | 744(18%) | 18(1%) | 726(29%) |

| Street Venders | 307(7%) | 102(6%) | 205(8%) |

| Small retail shop | 73(2%) | 46(3%) | 27(1%) |

| Hotel | 229(6%) | 129(8%) | 100(4%) |

| Domestic service | 159(4%) | 142(8%) | 17(1%) |

| Factory | 340(8%) | 116(7%) | 224(9%) |

| Other | 346(8%) | 96(6%) | 250(10%) |

| Monthly income (Yuan) | 877.97(727.35) | 835.58(741.73) | 906.92(716.09)** |

| Daily working hours | 10.16(3.30) | 10.09(3.51) | 10.20(3.15) |

| Days off per month | 2.88(2.25) | 3.04(2.22) | 2.77(2.27)**** |

Note: Responses were significantly differ by gender (p<.0001).

Significant gender differences in type of employment were observed (p<.01). For example, more women than men reported working in restaurants (20% versus 15%), barbershops or beauty salons (20% versus 9%), hotels (8% versus 4%), and domestic services (8% versus 1%). In contrast, more men than women reported working in construction (29% versus 1%). Men made slightly more money than women (907 Yuan versus 836 Yuan, p<.01) and had fewer days off each month (2.77 versus 3.04, p<.01).

General health conditions

As shown in Table 3, about one-quarter of the respondents reported fair or poor health. One fourth to one third of the respondents said that their health conditions had prevented them from performing activities that require moderate strength (such as moving a table, climbing stairs to 5th or 6th floor). One-quarter and one-tenth of the respondents reported that physical problems had reduced or prevented their work performance and accomplishment in the previous month, respectively. About half of the sample reported that emotional problems had prevented them from achieving their goals or that they suffered emotional unrest. About 5% of the respondents reported that physical pain had prevented their normal work most or all the time in last the month and a similar number of respondents reported that their health problems (either physical or psychological) had limited their social activities most or all the time. There were some gender differences, with more females reporting poor or fair health (25% versus 21%, p<.0001) and being affected or disturbed by their physical and emotional problems (mean health composite index was 7.55 for females and 7.65 for males, p<.05).

Table 3.

Health-related outcomes among rural-to-urban migrants in China

| Gender | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Female | Male | |

| General health condition | |||

| Poor or fair health | 946(23%) | 426(25%) | 520(21%)**** |

| Health prevented activities require moderate strength | 1584(38%) | 885(53%) | 699(28%)**** |

| Health prevented climbing 5–6 floors | 977(24%) | 475(29%) | 502(20%)**** |

| Accomplished less because of physical problem | 1127(27%) | 441(26%) | 686(28%) |

| Could not do much because of physical problem | 448(11%) | 161(10%) | 287(12%)* |

| Accomplished less because of emotional | 1613(39%) | 670(40%) | 943(38%) |

| Not very careful because of emotional problem | 2037(49%) | 852(51%) | 1185(48%)* |

| Pain prevented normal work most or all time | 167(4%) | 61(4%) | 106(4%) |

| Health limited social activities most/all the time | 195(5%) | 65(4%) | 130(5%)** |

| What did you do when you got sick1 | |||

| Did nothing | 241(7%) | 103(7%) | 138(7%) |

| Self-treated | 1860(51%) | 784(51%) | 1076(51%) |

| Went to big hospital | 1797(49%) | 796(52%) | 1001(47%)** |

| Went to formal clinic | 711(19%) | 246(16%) | 465(22%)**** |

| Saw unlicensed doctor | 74(2%) | 19(1%) | 55(3%)** |

| Top 6 reasons for not seeing a doctor | |||

| Illness was not serious | 2798(67%) | 1180(71%) | 1618(65%)**** |

| Had medicine handy | 1342(32%) | 610(36%) | 732(30%)**** |

| Too expensive to see a doctor | 1334(32%) | 513(31%) | 821(33%) |

| No time | 756(18%) | 321(19%) | 435(18%) |

| Afraid affecting job | 633(15%) | 278(17%) | 355(14%)* |

| Inconvenience | 466(11%) | 173(10%) | 293(12%) |

| Did you ever do a physical exam?2 | |||

| Yes, I did it on my own will | 1168(28%) | 457(27%) | 711(29%) |

| Yes, I did it because I was required to do so | 1777(42%) | 849(50%) | 928(37%) |

| No, I never did it | 1243(30%) | 383(23%) | 860(34%) |

| Substance Use | |||

| Smoked more than half pack daily last month | 479(11%) | 30(2%) | 449(18%)**** |

| Got drank ≥ once last month | 1184(28%) | 275(16%) | 909(36%)**** |

| Depression (CESD) | 11.52(9.45) | 11.55(9.83) | 11.50(9.18) |

| Dissatisfied with | |||

| Current life | 1114(27%) | 388(23%) | 726(29%)**** |

| Current work | 1184(28%) | 434(26%) | 750(30%)**** |

Note: Data were available only from those who had ever become ill;

Responses significantly differ by gender (p<.0001).

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.0001

Health-seeking Behaviors

Approximately one-eighth of the sample (9% females and 15% males) reported no illness during migration. As shown in Table 3, among those who reported ever becoming ill, 7% claimed that they did nothing, approximately 50% reported self-treatment or treatment at hospitals, 19% reported treatment from pubic clinics, and a small number (2%) reported seeking treatment from practitioners not licensed to practice medicine. Although significant gender differences were found among respondents in terms of whom and where medical care was sought, differences were relatively small (Table 3). The top reasons for not seeing a doctor for treatment included excessive cost (32%), limited time (18%), and inconvenience (11%). Seventy percent of the sample (77% women and 63% men) reported having received a physical examination, although only 28% of the sample received a self-initiated physical examination. More women than men received a physical examination because it was required by their employees or others (50% versus 37%).

Substance Use

About one-tenth of the sample reported smoking more than 15 cigarettes daily in the past month and 28% reported intoxication with alcohol at least once during the same time period. Significantly more men than women were heavy cigarette smokers (18% versus 2%, p<.01) and alcohol abusers (36% versus 16%, p<.01).

Depressive Symptom and Life Satisfaction

As shown in Table 3, the mean score of CESD among this sample of rural-to-urban migrants was 11.52 (SD=9.45); the CESD score was relatively similar for males and females. More than one-fourth of the sample reported dissatisfaction with their life situation (27%) or current work (28%), with more men than women reporting dissatisfaction with their life (29% versus 23%, p<.01) or current work (30% versus 26%, p<.01).

Association between health indicators and mobility

As shown in Table 4, the categorized mobility index did not vary appreciably among men and women. In contrast, mobility varied with age and marital status, such that younger single migrants were more mobile (p<.01 for age and marital status). Additionally, migrants who were more mobile earned less money per month than migrants who were not as mobile (range from 694 Yuan to 944 Yuan, p<.01). Mobility was found to be negatively associated with a variety of health indicators examined in this study.

Table 4.

Association between health indicators and mobility among rural-to-urban migrants in China

| Overall | Mobility Index1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| N(%) | 4149 (100%) | 832(20%) | 668(16%) | 1166(28%) | 971(23%) | 512(12%) |

| Demographic Characteristics | ||||||

| Male | 2470(60%) | 494(59%) | 414(62%) | 677(68%) | 578(60%) | 307(60%) |

| Single | 2898(72%) | 399(50%) | 395(61%) | 860(76%) | 85(86%) | 429(86%)**** |

| Age (years) | 23.47(3.78) | 25.83(3.48) | 24.86(3.60) | 23.22(3.44) | 21.83(3.25) | 21.45(3.45)**** |

| Duration of migration (years) | 4.28(3.04) | 7.25(3.10) | 5.78(3.12) | 3.88(2.07) | 2.61(1.61) | 1.48(1.08)**** |

| # of migratory cities | 2.11(1.23) | 1.42(.73) | 2.16(1.23) | 2.15(1.17) | 2.37(1.29) | 2.58(1.43)**** |

| Monthly income (Yuan) | 843(726) | 945(709) | 918(639) | 828(698) | 806(879) | 685(545)**** |

| Health Indicators | ||||||

| Unstable living condition | 2.04(.87) | 2.14(.84) | 2.05(.89) | 2.03(.88) | 2.01(.88) | 1.96(.86)** |

| Worsened employment condition | 2.96(1.13) | 2.99(1.12) | 3.07(1.12) | 2.95(1.12) | 2.87(1.12) | 2.84(1.17)*** |

| General health condition | 7.61(1.29) | 7.68(1.28) | 7.74(1.29) | 7.67(1.27) | 7.47(1.30) | 7.42(1.27)**** |

| Health-seeking | 2.09(.80) | 2.20(.76) | 2.08(.81) | 2.04(.81) | 2.08(.80) | 2.04(.84)**** |

| Substance use | .40(.59) | .35(.57) | .43(.62) | .42(.60) | .41(.60) | .35(.55)* |

| Depression | 11.51(9.43) | 10.40(9.13) | 10.39(8.71) | 11.35(9.31) | 12.53(9.72) | 13.20(10.08)**** |

| Life satisfaction | 3.03(.92) | 3.18(.87) | 3.05(.89) | 3.02(.91) | 2.92(.95) | 2.98(.96)**** |

Note: Fifty-nine participants (20 women 29 men) had missing value on the mobility index.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001,

p<.0001

Table 5 depicts the results of multivariate analysis on associations between mobility and health indicators. The MANCOVA model controlled for possible covariates such as age, gender, marital status, education, income. The model also assessed the interactions among mobility, gender and marital status. The analysis revealed a multivariate significance for mobility, gender, and marital status as well as two of the interactions (i.e., mobility by gender and gender by marital status). Similar to the results from the bivariate analyses, increased mobility was associated with substandard living conditions (p<.05), worsened employment conditions (p<.0001), suboptimal health status (p<.05), low health-seeking behavior (p<.001), higher numbers of depressive symptoms (p<.0001), and decreased life satisfaction (p<.05); gender was significantly associated with living condition (p<.0001), health-seeking behaviors (p<.0001), and substance use (p<.0001) in the multivariate model. In contrast, marital status was significantly associated with employment conditions (p<05), depression (p<.05) and life satisfaction (p<.01). There were no significant interaction terms at the univariate level except the interaction between gender and marital status for living condition (p<.05) and health-seeking behaviors (p<.01).

Table 5.

Results of Multivariate Analysis of Covariance (MANCOVA)

| Main effects | Interaction | Covariate | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobility (M) | Gender (G) | Single (S) | MXG | MXS | GXS | MXGXS | Age | Income | Education | |

| Multivariate test (Pillais F) Univariate test | 3.84**** | 45.07**** | 2.55* | 1.37 | 1.26 | 2.62* | 1.39 | |||

| Living condition | 2.91* | 60.98**** | .09 | .79 | 1.38 | 4.44* | 1.16 | 1.46 | 3.42*** | 8.75**** |

| Employment condition | 7.78**** | 1.68 | 4.71* | 2.43* | .82 | .85 | .52 | −3.31*** | 6.28**** | 11.14**** |

| General health condition | 3.18* | 2.51 | .38 | .35 | .16 | .15 | 1.00 | −1.74 | −.58 | .007 |

| Health-seeking | 4.97*** | 27.24**** | .47 | .98 | 1.16 | 8.55** | 1.83 | −.87 | 1.75 | 6.64**** |

| Substance use | 2.69* | 218.30**** | .12 | 2.17 | 1.28 | .30 | 1.75 | 1.63 | 6.18**** | −.29 |

| Depression | 7.78**** | .00 | 5.66* | 1.29 | 1.50 | 1.89 | 1.32 | −.37 | −.02 | −3.59**** |

| Life satisfaction | 3.12* | 3.48 | 8.67** | .89 | 1.66 | .18 | 1.17 | .92 | 4.90**** | −1.58 |

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001,

p<.0001

Age was a covariate found to be negatively associated with employment conditions (p<.001). Monthly income, in contrast, was a covariate found to be positively associated with living condition, employment condition, substance use, and life satisfaction (p<.0001). Likewise, migrants with higher level of education had better living and employment conditions, more health-seeking behaviors and less depressive symptoms (p<.0001).

Discussion

The process of rural-to-urban migration in China is accelerating with increased modernization and industrialization. The fact that about half of the migrants were between the age of 18 and 29 years old (CNBS, 2002) suggests that the migrant workforce in China is comprised largely of young adults. Migrants are particularly vulnerable to geographic mobility, financial instability, and rapidly changing environments. In this study we report the geographic mobility and its association with a number of health indices among 4,208 rural-to-urban migrants in China. Data from the present study indicate a similar pattern of geographic mobility between migratory women and men. The increasing mobility among the rural-to-urban migrants is associated with being younger and single. Increasing mobility is also associated with low income, unstable living conditions, worsened employment, suboptimal health, low health-seeking, more substance use and depressive symptoms, and less life satisfaction. Although only 4% of the migrants were not employed (or self-employed) at the time of the survey, with most of the migrants with jobs were working in the informal sectors or labor-intensive industry (e.g. entertainment and personal services for women and construction for men).

Results from the current study suggest that rural-to-urban migrants appear to experience many health risk behaviors. Whereas data from previous studies in China indicate that approximately 4% females in the general population consume minimal amounts of alcohol on a monthly basis (Wei et al., 1995), in this study 16% females reported having consumed alcohol to intoxication at least once during the past 30 days. These rates are unusually high in a culture where alcohol consumption is acceptable in social contexts (e.g., celebrations), but is frowned upon when it occurs in isolation (e.g., solitary drinking) (Williams, 1998). Migrants in the present study were also found to smoke more cigarettes than the general Chinese adult population: 18% males and 2% females were heavy smokers among the study sample, compared to 7.5% and 0.2% heavy smokers among male and female adults in China (Yang, 1997). In spite of their high level of health risk, a substantial number of migrants in our sample did not report the utilization of health facilities for health care (e.g., over half self-treating or doing nothing when becoming ill). Although workers are required by the government to have routine physical examination before employment in urban areas (Zhi, Sheng, & Levine, 2000), migrants in the present study appeared reticent to seek routine physical examinations (i.e., approximately one-third never had any routine physical check up).

In the absence of formalized access to education, employment, and health care, any population is vulnerable to health risks (Booysen & Summerton, 2002; Krueger, Wood, Diehr, & Maxwell, 1990). Such a description is applicable to migrants in China. The legal system in China has significantly curtailed entitlement of the migrant population to basic benefits accorded to other segments of the population for almost half a century (Zhang L, 2001). However, at any given point in time, it is difficult to characterize the nature of these restrictions because the government has repeatedly changed relevant regulations, particularly during the past decade. As a result, the migrant population is placed in a vulnerable position in two respects. First, regardless of the exact nature of legislative restrictions, migrants experience significant limitations to their entitlements. For example, migrants have to pay more than local residents for many of their daily essentials such as housing, utilities, education, and transportation (Li et al., 2005; Zhang, L, 2001). Second, the rapid change of legislation and governmental regulations further restrict access of the migrant population to entitlements to which they might have access because local authorities and programs responsible for policy implementation are uncertain as to the current legislative status. For example, in 2002 the Chinese government mandated reduction of the fees imposed by local governmental agencies on migrants for work, residence, and housing permits. However, rather than increasing migrant access to these necessities, the government’s initiatives resulted in the reduction of operations of these respective offices since they could no longer recoup expenses through the fees paid by migrants, thereby rendering it difficult or impossible for migrants to obtain the necessary permits, a situation exposing an increased instability or mobility, as well as leaving the migrant population unable to access legitimate employment and proper housing (Zhang L, 2001).

China faces a substantial challenge in developing a healthcare infrastructure sufficient to cover its 1.3 billion residents. This challenge is even greater considering the emerging population of rural-to-urban migrants. The Chinese government and the Chinese society in general are now starting to recognize the need for healthcare targeted specifically at rural-to-urban migrants (Liu, Zhao, Cai, & Yamada, 2002; Wei, P, 2002; Xinghua News Agency, 2003;Ying, 2003).. The findings in the present study underscore the need for increased medical and health care services available to this population in urban areas, as well as health promotion programs that target these migrants. Furthermore, the lack of basic facilities in their daily life, such as tap water, showers/bathtubs, restrooms, and telephone lines among migrants further strains an already overburdened healthcare system. These findings underscore the importance of improving living and employment conditions in urban areas for this population.

This study has several potential limitations. First, respondents for this study were recruited through convenience sampling and therefore caution should be taken to generalize findings from this study to other migrant populations in China. Second, data used for this analysis are cross-sectional in nature; causality can not be determined between mobility and health indicators. Third, there was no non-migrant comparison group in the current study. The lack of comparison group precludes any conclusion about the relative standing of migrants’ health risk and health seeking behaviors in comparison with other non-migratory populations in China (e.g., rural population, urban poor). Fourth, data on some specific health outcome related to migration such as childhood immunization rates or infectious diseases were not available in this study. Despite these methodological limitations, this study is, to the best of our knowledge, one of the first efforts to examine the relationship of geographic mobility with health indcaitors including health outcomes among rural-to-urban migrants in China. By providing preliminary data on important health indicators among rural-to-urban migrants in China, these findings will be helpful to China as it addresses issues and policies relevant to a vulnerable population with unique cultural, economic, and health needs,.

Findings in the current study, coupled with others (Grogan, 1995; Li, et al., 2005; Zhang L, 2001; Zhi et al., 2000), suggest the need to systematically provide the rural-to-urban migrants with access to adequate and affordable health care while they are “floating” in the urban areas. Efforts are also needed to eradicate institutionalized and cultural barriers that have prevented migrants from benefiting from their urban life, by providing improved residency, employment and health care opportunities. Health promotion activities, including education and training (to both migrant and urban residents), are needed to improve the health conditions and lifestyles of rural-to-urban migrants and to enable migrants to assimilate themselves into the urban culture and environment.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported by NIMH (grant #R01MH064878). The authors wish to thank our colleagues and graduate students at Beijing Normal University Institute of Developmental Psychology and Nanjing University Institute of Mental Health for their assistance in data collection. The authors also want to thank Dr. Lesley Cottrell, Dr. Ambika Mathur and Ms. Joanne Zwemer for their assistance in preparing the manuscript.

References

- Anderson K, Huang J, Ianchovichina E. Long-run impacts of China WTO accession on farm-non-farm income inequality and rural poverty (World Bank Policy Research Working Paper #3052) Washington DC: World Bank; 2003. May, [Google Scholar]

- Bogg L, Dong H, Wang K, Cai W, Winod D. The cost of coverage: rural health insurance in China. Health Policy Plan. 1996;11(3):238–252. doi: 10.1093/heapol/11.3.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booysen FR, Summerton J. Poverty, risky sexual behavior, and vulnerability to HIV infection: evidence from South Africa. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition. 2002;20(4):285–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- China National Bureau of Statistics (CNBS) Characteristics of Chinese Rural Migrants. Beijing: CNBS; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- China National Bureau of Statistics (CNBS) China’s Rural-to-urban migrants exceed 114 million (Chinese article) News Release 2004. 2003 Available at: http://www.cqna.gov.cn/224055180973309952/20040629/1042012.html (last retrieved 11/25/2005)

- Darmon N, Khlat M. An overview of the health status of migrants in France, in relation to their dietary practices. Public Health Nutrition. 2001;4(2):163–172. doi: 10.1079/phn200064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RM, Ayla G, Bein E, Henne J, Marin BV. The impact of homophobia, poverty, and racism on the mental health of gay and bisexual Latino men: Findings from 3 US cities. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:927–932. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Tang S, Tolhurst R, Rao K. Changing access to health services in urban China: implications for equity. Health Policy Plan. 2001;16(3):302–312. doi: 10.1093/heapol/16.3.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grogan CM. Urban economic reform and access to health care coverage in the People’s Republic of China. Social Science & Medicine. 1995;41(8):1073–1084. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00419-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y. Marital status and attitudes towards marriage among female migrants in Jiangsu. South China Population. 2000;15(2):39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger LE, Wood RW, Diehr PH, Maxwell CL. Poverty and HIV seropositivity: The poor are more likely to be infected. AIDS. 1990;4(8):811–814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampton DM. China’s health care disaster. Asia Wall Street Journal 2003 May; [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Stanton B, Fang X, Lin D. Social stigmatization and mental health among rural-to-urban migrants in China: a conceptual model and some future research needs. doi: 10.12927/whp.2006.18282. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Stanton B, Fang X, Lin D, Mao R, Wang J, et al. HIV/STD risk behaviors and perceptions among rural-to-urban migrants in China. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2004;16(6):538–556. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.6.538.53787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu GG, Zhao Z, Cai R, Yamada T. Equity in health care access to: assessing the urban health insurance reform in China. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;55(10):1779–1794. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00306-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay L, Macintyre S, Ellaway A. Medical Research Council (MRC) Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, Occasional Paper No 12. University of Glasgow; Glasgow, UK: 2003. Jan, Migration and health: A review of the international literature. [Google Scholar]

- Pernice R, Brook J. The mental health pattern of migrants: Is there a euphoric period followed by a mental health crisis? The International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 1996;42:18–27. doi: 10.1177/002076409604200103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pudaric S, Sundquist J, Johansson SE. Major risk factors for cardiovascular disease in elderly migrants in Sweden. Ethnicity & Health. 2000;5(2):137–150. doi: 10.1080/713667448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Smith CJ. Modernization and health care in contemporary China. Health Place. 1998;4(2):125–139. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8292(98)00005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford MC. Stigma deviance and social control: some conceptual issues. The Dilemma of Difference. 1986:77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens J. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences. 3. Hillside, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Tie P. Survey of risk factors among migrants. Disease Monitoring. 1999;14(6):229–230. [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. Rating Scales for Mental Health (Chinese Journal of Mental Health Supplement) Beijing: Chinese Association of Mental Health; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care. 1996;34(3):220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei H, Young D, Lingjiang L, Shuiyuan X, Jian T, Hanshu S, et al. Psychoactive substance use in three sites in China: gender differences and related factors. Addiction. 1995;90(11):1503–1515. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.901115039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei P. Maternal and child care: Equal rights for urban and rural-to-urban migrants. Health News of China. 2002:2002. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DM. Alcohol indulgence in a Mongolian community of China. Bulletin of Concerted Asian Scholars. 1998;30(1):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Xinghua News Agency. Urban and rural income differences urge the needs to raise income in rural population. Chinese News. 2003 March 7; [Google Scholar]

- Yang G. Smoking and Health in China: 1996 National Prevalence Survey on Smoking Pattern. Beijing: China Science and Technology Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ying J. Migrants in urban China: A vulnerable group of population in society transitions of China that needs urgent attention. [Accessed August 2, 2003];Association of Sociology of China. 2003 Available at: http://www.chinasociology.com/rzgd/rzgd029.htm.

- Zhang L. Migration and privatization of space and power in late socialist China. American Ethnologist. 2001;28(1):179–205. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W. Building for future: The social and financial structure needed to provide effective and affordable care. Symposium at the Health Care, East and West, Moving into the 21st Century Conference; Boston, MA. 2001. Jun, [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Z, Zhou Y, Zheng L, Yang Y, Zhao D, Lou C, et al. Sexual behavior and contraceptive use among unmarried, young women migrant workers in five cities in China. Reproductive Health Matters. 2002;9(17):118–127. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(01)90015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhi S, Sheng W, Levine SP. National Occupational Health Service policies and programs for workers in small-scale industries in China. American Industry Hygiene Association Journal. 2000;61(6):842–849. doi: 10.1080/15298660008984596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]