Abstract

The ability to culture functional adult mammalian spinal-cord neurons represents an important step in the understanding and treatment of a spectrum of neurological disorders including spinal cord injury. Previously, the limited functional recovery of these cells, as characterized by a diminished ability to initiate action potentials and to exhibit repetitive firing patterns, has arisen as a major impediment to their physiological relevance. In this report we demonstrate that single temporal doses of the neurotransmitters serotonin, glutamate (N-acetyl-DL-glutamic acid) and acetylcholine-chloride leads to the full electrophysiological functional recovery of adult mammalian spinal-cord neurons, when they are cultured under defined serum-free conditions. Approximately 60% of the neurons treated regained their electrophysiological signature, often firing single, double and, most importantly, multiple action potentials.

Keywords: Adult Rat Spinal Cord Neurons, Acetylcholine-Chloride, Electrophysiology, Glutamate (N-acetyl-DL-glutamic acid), Motoneuron, Neurotransmitters, Regeneration, Serotonin, Serum-free Medium, Silane Substrate

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) and disease are debilitating conditions that have seen limited progress in the full repair of damaged neurons in the CNS (Dumont et al., 2001; Schwab, 2002). Therefore, much effort has been undertaken to develop in vivo models of SCI and study the cellular and molecular mechanisms of synaptic connections and information processing in the spinal cord. However, in vitro models of SCI using dissociated adult cells have not been as extensively investigated due to the difficulties associated with culturing adult CNS neurons. Fully functional in vitro model systems could be useful not only in spinal cord injury studies but possibly also for models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), multiple sclerosis (MS) and neuropathic pain. Recent advancements in the culture of adult mammalian spinal cord (Das et al., 2005; Das et al., 2007) and brain neurons (Brewer, 1999; Fedoroff and Richardson, 2001; Brewer, 1997) in a completely defined serum-free medium, suggest outstanding potential for answering questions that relate to maturation, aging, neurodegeneration and injury, as well as the ability to screen different novel and putative drug candidates for CNS repair and degenerative diseases of the CNS. Prominent features of the survival of adult CNS neurons in these culture systems have been ascribed to a permissive growth promoting substrate and defined culture medium (Das et al., 2005; Das et al., 2007; Brewer, 1999; Fedoroff and Richardson, 2001; Brewer, 1997).

However, there are few reports on the evaluation of the electrical functionality and regeneration of adult CNS neurons in long-term culture (Das et al., 2005; Das et al., 2007; Brewer, 1997; Evans et al., 1998). Recent electrophysiological studies on adult spinal cord neurons in a defined culture indicated that only approximately 30% of the total surviving neurons were electrically active (Das et al., 2005; Das et al., 2007). In all cases, the neurons showed a very weak inward and outward current in voltage clamp studies and only fired single action potentials with limited culture duration (Das et al., 2005; Das et al., 2007).

We report here on the development of a robust and long-term culture model of adult rat spinal-cord neurons by the addition of four more growth factors (i.e. VEGF (Azzouz et al., 2004; Lambrechts et al., 2003), G5 supplement (Bottenstein, 1985), NT-4 (Bregman et al., 1997; Friedman et al., 1995) and CNTF (Kato and Lindsay, 1994; Masu et al., 1993; Oppenheim et al., 1991)) to a previously developed model (Das et al., 2005; Das et al., 2007). In addition, it was discovered that the electrical functionality of 60% of the neurons could be re-established by long-term temporal incubation of the cultures with serotonin + glutamate (N-acetyl-DL-glutamic acid) followed by acetylcholine-chloride, providing in vitro evidence to support the hypothesis that extracellular neurotransmitters may be involved in shaping synaptic circuits in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Surface modification of the coverslips

Glass coverslips (Thomas Scientific 6661F52, 22 × 22 mm2 no. 1) were cleaned using an O2 plasma cleaner (Harrick PDC-32G) for 20 min at 100 mTorr. The DETA (United Chemical Technologies Inc., Bristol, PA, T2910KG) films were formed by the reaction of the cleaned surface with a 0.1% (v/v) mixture of the organosilane in freshly distilled toluene (Fisher T2904), according to Ravenscroft et al. (1998) (Ravenscroft et al., 1998). The DETA-coated coverslips were heated to just below the boiling point of toluene, rinsed with toluene, reheated to just below the boiling temperature, and then oven dried (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Outline of the defined culture system to study the regeneration of adult mammalian spinal cord neurons.

Surface characterization of the coverslips after coating with DETA

Surfaces were characterized by contact angle measurements using an optical contact angle goniometer (KSV Instruments, Monroe, CT, Cam 200) and by X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) (FISONS ESCALab 220i-XL). The XPS survey scans, as well as high-resolution N 1s and C 1s scans, using monochromatic Al Kα excitation, were obtained similar to the previously reported results (Das et al., 2005; Das et al., 2007; Ravenscroft et al., 1998; Das et al., 2006; Das et al., 2003; Das et al., 2007).

Isolation and culture of rat spinal cord

Spinal cords were isolated from adult rats (4–6 months old), and the meninges were removed from the spinal cord. The spinal cord was then cut into small pieces and collected in cold Hibernate A (http://www.brainbitsllc.com), glutamine (0.5 mM), and B27 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Next, the tissue was enzymatically digested for 30 min in papain (2 mg/ml). The tissue was triturated in 6 ml of fresh Hibernate A, glutamine (0.5 mM), and B27. The 6 ml cell suspension was layered over a 4 ml step gradient (Optipep diluted 0.505:0.495 [v/v] with Hibernate A–glutamine 0.5 mM–B27) and then made to 15, 20, 25, and 35% (v/v) in Hibernate A–glutamine 0.5 mM–B27 followed by centrifugation for 15 min, using 800 × g, at 4° C. The top 7 ml of the supernatant was aspirated. The next 2.75 ml from the major band and below was collected and diluted in 5 ml Hibernate A–B27 and centrifuged at 600 × g for 2 min (Fig. 1). The pellet was resuspended in Hibernate A–B27, and after a second centrifugation, the pellet was resuspended in the culture medium (Table 1 shows the specific composition). Complete culture medium change occurred after the first 2–3 d in culture, and thereafter half of the medium was changed after every 5–6 d (Das et al., 2005; Das et al., 2007). Half of the media was changed on the following days after plating the cells: day 6, 11, 16, 21, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 55, 60. Neurotransmitter treatments were started on day 30. Throughout the study individual neurotransmitters were added only one time. The details of the neurotransmitter treatments are described in the following paragraphs.

Table 1.

Composition of the serum-free medium.

| Component | Amount/Concentration | Company | Catalogue Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurobasal A | 500 ml | Gibco | 10888 |

| Glutamax | 5 ml | Invitrogen | 35050–061 |

| Antibiotic-Antimycotic | 5 ml | Invitrogen | 15240–062 |

| B27 Supplement | 10 ml | Gibco | 17504–044 |

| G5 (100x) | 5 ml | Invitrogen | 17503–012 |

| VEGF 165 | 10 μg | Invitrogen | P2654 |

| Acidic-FGF | 10 μg | Invitrogen | 13241–013 |

| Human BDNF | 10 μg | Cell Sciences | CRB 600B |

| Human GDNF | 10 μg | Cell Sciences | CRG 400B |

| Rat CNTF | 25 μg | Cell Sciences | CRC 401B |

| Human CT-1 | 10 μg | Cell Sciences | CRC 400B |

| NT-3 | 10 μg | Cell Sciences | CRN 500B |

| NT-4 | 10 μg | Cell Sciences | CRN 501B |

| Vitronectin | 50 μg | Sigma | V0132 |

| De-N-sulphated N-acetylated Heparin sulphate | 40 μg | Sigma | D9809 |

Neurotransmitter application

The three excitatory neurotransmitters glutamate (A8875, Sigma), serotonin (H9523, Sigma) and acetylcholine chloride (A2661, Sigma) were used for the study. N-acetyl-DL-glutamic acid was used as a source for glutamate in the culture because it is naturally occurring in the brain (Auditore et al., 1966). It is also more stable (Hashimoto and Naito, 1998) and we have found that it improved the cell density of the culture.

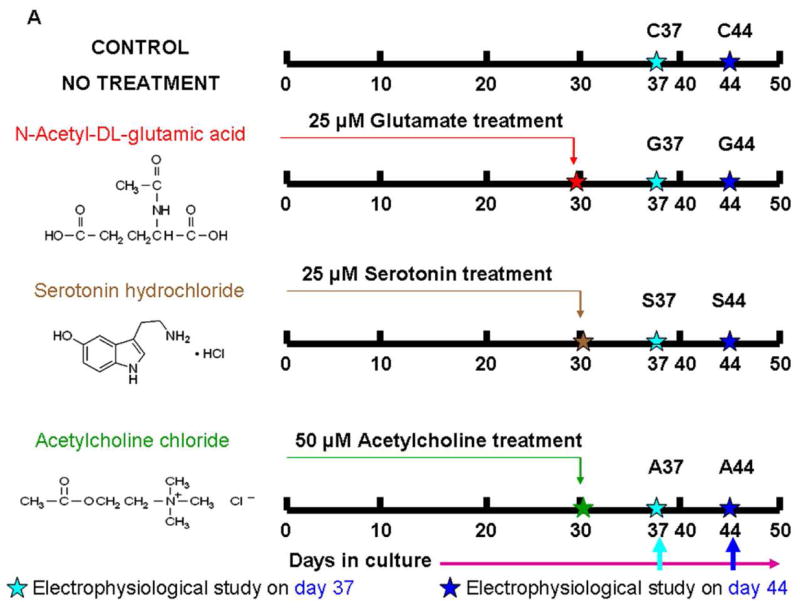

In the first series of experiments to study the effect of the individual neurotransmitters, 30 days old cultures were treated one time with either 25 μM N-acetyl-DL-glutamic acid, 25 μM serotonin or 50 μM acetylcholine chloride. The electrophysiological evaluations were done after 7 and 14 days of incubation in the neurotransmitters. In the second series of experiments, the combined effect of serotonin (25 μM) + N-acetyl-DL-glutamic acid (25 μM) was evaluated. The N-acetyl-DL-glutamic acid + serotonin combination was applied at day 30 and the electrophysiological properties of the cells were evaluated after 7 and 14 days of incubation. In the final part of the experiment, the N-acetyl-DL-glutamic acid (25 μM) + serotonin (25 μM) combination was applied at day 30 and followed by the addition of acetylcholine chloride (50 μM) after 5 additional days. The neuron’s electrophysiological properties were evaluated 14 days after the initial treatment of N-acetyl-DL-glutamic acid +serotonin. During each experiment neurotransmitter solutions were freshly prepared.

Immunocytochemistry

In preparation for staining with anti-neurofilament 150, anti-synaptophysin, anti-nestin protein and the MAP2 a and b antibodies, the coverslips were rinsed free of medium with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed for 20 min at room temperature with 10% glacial acetic acid and 90% ethanol. The staining of the coverslips with anti MO-1 and anti-Islet antibody 39.4D5 and ChAT were similarly rinsed free of medium with PBS, but fixed using a different protocol. We added 80 μl of paraformaldehyde (prepared in PBS) in 2 ml of medium for 5 min. This reaction is done by keeping the 6 well plate on top of ice. After 5 minutes, the coverslips were rinsed free of medium with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed for 20 min at room temperature with cold fixative (11.1 ml of Formalin+ 89.9 ml of PBS+ 200 μl of Glutaraldehyde+ 4g of Glucose). The rest of the steps for staining remain the same. After 20 minutes of fixing, cells were permeabilized for 5 minutes with permebilizing solution (50 mM Lysine+ 0.5% Triton X-100+ 100 ml of PBS). After rinsing with PBS, the nonspecific sites were blocked with 5% normal donkey serum and 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS. The cells were blocked for 2 hours and then the cells are incubated with the primary antibodies for 12 h at 4°C.

Cells were incubated overnight at 4° C with either rabbit antineurofilament M polyclonal antibody, 150 kDa (Chemicon, AB1981, diluted 1:1000), anti-nestin (MAB5326, Chemicon, diluted 1:1000), anti-synaptophysin (MAB368, Chemicon, diluted 1:1000), anti-MAP 2 A and B (MAB364, Chemicon, diluted 1:1000), anti-Choline Acetyltransferase (ChAT, AB143, diluted 1:250), anti-Islet antibody 39.4D5 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA, diluted 1:50), or MO-1 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA, diluted 1:50), in the blocking solution. After incubating overnight, the coverslips were rinsed four times with PBS and then incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies for 2 h. After rinsing four times in PBS, the cover slips were mounted with Vectashield mounting medium (H1000, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) onto slides. The coverslips were observed and photographed using a Ultra VIEW™ LCI confocal imaging system (Perkin Elmer). Controls without primary antibody were negative (Das et al., 2005; Das et al., 2007).

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell patch clamp recordings were performed in a recording chamber that was placed on the stage of a Zeiss Axioscope 2 FS Plus upright microscope in Neurobasal culture medium (pH was adjusted to 7.3 with N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethane-sulfonic acid [HEPES]) at room temperature. Patch pipettes (6–8 Mohm) were filled with intracellular solution (K-gluconate 140 mM, ethylene glycol-bis[aminoethylether]-tetraacetic acid 1 mM, MgCl2 2 mM, Na2ATP 5 mM, HEPES 10 mM; pH = 7.2). Voltage clamp and current clamp experiments were performed with a Multiclamp 700A (Axon, Union City, CA) amplifier. Signals were filtered at 3 kHz and digitized at 20 kHz with an Axon Digidata 1322A interface. Data recording and analysis was performed with pClamp 8 (Axon) software. Sodium and potassium currents were measured in voltage clamp mode using voltage steps of 10 mV from a −70 mV holding potential. Whole-cell capacitance and series resistance was compensated and a p/6 protocol was used. The access resistance was less than 22 Mohm. Action potentials were measured with 1 s depolarizing current injections from the −70 mV holding potential (Das et al., 2005; Das et al., 2007; Das et al., 2006; Das et al., 2003; Das et al., 2007).

Statistics

Chi-squared test

Any significant differences (p = 0.05) between treatments as compared to the control were quantified using the double classification Chi-squared test (Table 2). ANOVA: For pairwise comparisons of the means, we used a one-way ANOVA and statistical tests assuming unequal variance (Tamhame’s test) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Comparison of the total number of cells patched and the number of cells which exhibited APs in control (C37, C44), glutamate treated (G37, G44), serotonin treated (S37, S44), acetylcholine chloride treated (A37, A44), glutamate+serotonin treated (GS37, GS44), and glutamate+serotonin→ acetylcholine chloride treated (GSA44). 37 and 44 indicates 7 and 14 days after culturing the cells in the presence of neurotransmitters respectively. Percentages are indicated in parentheses.

| Total number of cells patched | Number of cells which did not fire any action potential (NP) | Number of cells which fired single action potentials (SAP) | Number of cells which fired double action potentials (DAP) | Number of cells which fired multiple action potentials (MAP) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C37 | 24 | 17 | 7 (29.1%) | - | - |

| C44 | 49 | 35 | 14 (28.5%) | - | - |

| G37 | 42 | 28 | 14 (33.3%) | - | - |

| G44 | 14 | 8 | 6 (42.2%) | - | - |

| S37 | 17 | 10 | 7 (41.1%) | - | - |

| S44 | 25 | 14 | 11 (44.0%) | - | - |

| A37 | 30 | 25 | 5 (16.6%) | - | - |

| A44 | 31 | 25 | 6 (19.3%) | - | - |

| GS37 | 20 | 10 | 10 (50.0%) | - | - |

| GS44 | 27 | 11 | 14 (56.0%) | 2 (12.5%)** | - |

| GSA44* | 107 | 42 | 57 (60.7%) | 5 (7.6%)** | 3 (4.6%)*** |

A double classification Chi-squared test was used to test for multiple categories of data. We compare the X2 value with a tabulated χ2 with one degree of freedom. Our calculated X2 exceeds the tabulated χ2 value (3.84) for p = 0.05. We conclude that multiple neurotransmitter applications show significantly more electrically active cells as compared to the control.

Percentage of neurons as compared to the total number of electrically active neurons which fired double APs.

Percentage of neurons as compared to the total number of electrically active neurons which fired multiple APs.

Table 3.

Comparison of the electrical properties of the neurons which exhibited APs in control (C37, C44), glutamate treated (G37, G44), serotonin treated (S37, S44), acetylcholine chloride treated (A37, A44), glutamate+serotonin treated (GS37, GS44), and glutamate+serotonin→ acetylcholine chloride treated (GSA44). Since the neurotransmitters were added on day 30 after the cells were plated, the numbers 37 and 44 indicate 7 and 14 days respectively after culturing the cells in the presence of neurotransmitters. The values are expressed as Mean ± SE.

| C37 | C44 | G37 | G44 | S37 | S44 | A37 | A44 | GS37 | GS44 | GSA44 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days in vitro | 37 | 44 | 37 | 44 | 37 | 44 | 37 | 44 | 37 | 44 | 44 | |

| Number of neurons (n) | 7 | 14 | 14 | 6 | 7 | 11 | 5 | 6 | 10 | 16 | 65 | |

| Resting potential (Mv) | 51.7±3.1 | 48.2±2.9 | 48.9±3.2 | 50.4±4.4 | 50.3±1.5 | 48.9±1.3 | 52.4±2.1 | 52.5±1.7 | 52.8±2.8 | 46.2±3.3 | 44.2±1.3 | NS |

| Input resistance (mΩ) | 163.3±12.1 | 169.1±11.1 | 124.1±16.6 | 110.3±16.5 | 130.9±9.2 | 136.9±12.9 | 128.2±7.1 | 131.7±10.7 | 144.5±8.9 | 278.9±74.0 | 237.9±23.1 | NS |

| Capacitance (pF) | 18.3±1.9 | 17.0±1.9 | 15.8±1.1 | 14.8±1.2 | 15.71±1.5 | 15.4±1.5 | 15.4±1.6 | 18.5±1.9 | 17.2±2.8 | 18.9±1.4 | 17.7±0.9 | NS |

| Peak inward current (pA) | 657.1±39.9 | 681.4±134.6 | 674.8±127.9 | 737.2±69.4 | 402.1±43.7 | 359.1±33.6 | 450.0±44.7 | 525.0±70.4 | 713.9±95.2 | 1376.4±105.2 | 1090.4±79.9 | = 0.01 |

| Peak outward current (pA) | 770.7±43.1 | 833.53±110.3 | 883.6±166.2 | 855.0±77.3 | 829.3±70.2 | 745.5±67.5 | 605.0±37.4 | 625.0±61.6 | 768.6±83.2 | 1219.8±117.7 | 930.1±41.9 | NS |

| Action potential height (mV) | 26.4±2.4 | 16.6±1.3 | 18.1±2.3 | 20.2±3.4 | 20.7±1.5 | 16.9±1.3 | 18.8±2.6 | 20.2±2.4 | 18.4±1.8 | 25.6±2.4 | 23.84±1.1 | NS |

| Action potential width (ms) | 3.9±0.2 | 4.4±0.2 | 5.3±0.7 | 3.7±0.2 | 4.2±0.3 | 4.6±0.3 | 4.7±0.4 | 4.7±0.4 | 5.4±0.5 | 5.3±0.3 | 5.80±0.2 | NS |

p is calculated using a one-way analysis of variance. NS indicates not statistically significant.

Results and Discussion

Adult spinal-cord neuron regeneration experiments were carried out in a defined culture system which consisted of an empirically derived serum-free medium, synthetic cell growth promoting silane substrate and a well defined culture technique (Fig 1). The detailed composition of the serum-free medium is presented in (Table 1). The culture system was initiated by plating the dissociated adult rat spinal-cord cells on a synthetic, patternable (Ravenscroft et al., 1998), cell growth promoting organosilane substrate, N-1[3-(trimethoxysilyl)propyl]-diethylenetriamine (DETA) (Das et al., 2005; Das et al., 2007; Das et al., 2006; Das et al., 2003; Das et al., 2007; Das et al., 2007). Detailed protocols for the surface chemical modification of the substrate, characterization of the substrate, rat dissection, cell isolation and cell culture are discussed elsewhere (Das et al., 2005; Das et al., 2007) and described in detail in the methods section.

The advantages of a synthetic silane substrate are its reproducibility and suitability for high resolution patterning to allow the development of engineered networks (Ravenscroft et al., 1998),(Das et al., 2005; Das et al., 2007; Das et al., 2006; Das et al., 2003; Das et al., 2007) as well as the ability to couple specific extracellular matrix molecules and different contact signaling molecules to systematically study the specific role of such molecules in remyelination, neurodegeneration, and axonal growth inhibition during spinal cord injury. The ability to create functional in vitro networks of different types of neurons as well as neurons and muscle will allow detailed study of how these networks can be created or regenerated without having to observe the processes in vivo. Now the potential to recreate circuits in a defined system with adult cells extends this capability enormously. These results reported here, now allow the recreation of this active network in vitro.

In this culture model we have added four additional growth factors (i.e. VEGF, G5 supplement, NT-4 and CNTF) to a previously developed model (Das et al., 2005; Das et al., 2007). The present culture model, with four additional growth factors, promoted long-term survival (8–10 weeks) of the adult spinal cord cells (Table 1). Previously these individual factors (i.e. VEGF (Azzouz et al., 2004; Lambrechts et al., 2003), G5 supplement (Bottenstein, 1985), NT-4 (Bregman et al., 1997; Friedman et al., 1995) and CNTF (Kato and Lindsay, 1994; Masu et al., 1993; Oppenheim et al., 1991) had been shown to improve the survival of spinal cord neurons and glial cells either or both in vivo and in vitro. Possibly, these growth factors play a synergistic role in promoting the long-term survival of the regenerating adult spinal cord neurons in culture.

The neurons began their regeneration process within 24 h of plating the cells (Fig 2, upper panel) and this was characterized by the co-expression of nestin and neurofilament-150 proteins by the majority of the neurons between day 1–3. By day 4, the neurons only expressed neurofilament-150 and other neuron specific markers, with nestin expression lost by day 4 (Fig 2 lower panel). Co-expression of nestin and neurofilament-150 during the early stages of cell growth suggests that these cells may undergo an embryonic ‘reprogramming’ to allow for the regeneration of axonal and dendritic processes.

Figure 2.

Immunocytochemical evidence of the early events during the initiation of the regeneration process utilizing nestin and neurofilament-150. Upper panel. The regeneration process was initiated during the first 24 hours of cell plating and the live/dead assay indicates the majority of the plated cells are alive. Lower panel. Early regeneration events are characterized by co-expression of the nestin and neurofilament 150 proteins by most neurons between day 1–3. By day 4, the neurons only express neurofilament-150 and other neuron specific markers, as the nestin expression was lost by day 4.

Specific areas of the spinal cord were not selected for isolation and culture, suggesting that the culture contains a mixture of ventral horn motoneurons, dorsal horn neurons and interneurons. In addition, the culture contained 30–40% of GFAP positive cells although the proliferative potential of these cells was limited by the composition of the defined culture conditions used. The cultures were immunocytochemically characterized for the different cell types present at two different time intervals, day 35 and day 45 in culture. We used 6 different neuron specific antibodies (Islet-1, ChAT, MO-1, NF-150, MAP-2 and synpatophysin) for the immunocytochemistry. The results are presented in Fig 3, upper and lower panels. At day 35, most of the neurons exhibiting a smooth-appearing large soma, a multi-polar dendritic tree and a long axon, were later found to be electrically active. These neurons stained positive for Islet-1, MO-1 and ChAT (Fig 3 A, B, C, D), the three ventral horn spinal-cord motoneuron markers. In addition, the neurons expressed MAP-2 a and b, NF-150 proteins and synaptophysin (Fig 3 E, F, G, H).

Figure 3.

Immunostained cultures at day 35 utilizing different neuron specific antibodies. A. Phase coupled with fluroscence micrograph showing neurons stained with ISLET-1 antibody (a putative motoneuron marker). B. Fluroscent staining of the ISLET-1 positive cells shown in figure A. C. Neurons stained with MO-1 antibody (a putative motoneuron marker). D. Neurons stained with ChAT antibody (a putative motoneuron marker). E. Neurons double-stained with MAP 2a and b and NF 150 antibodies. F. Neurons double-stained with synaptophysin and NF 150 antibodies. G. Neurons stained with NF 150 antibody. H. Neurons stained with MAP 2, a and b antibody.

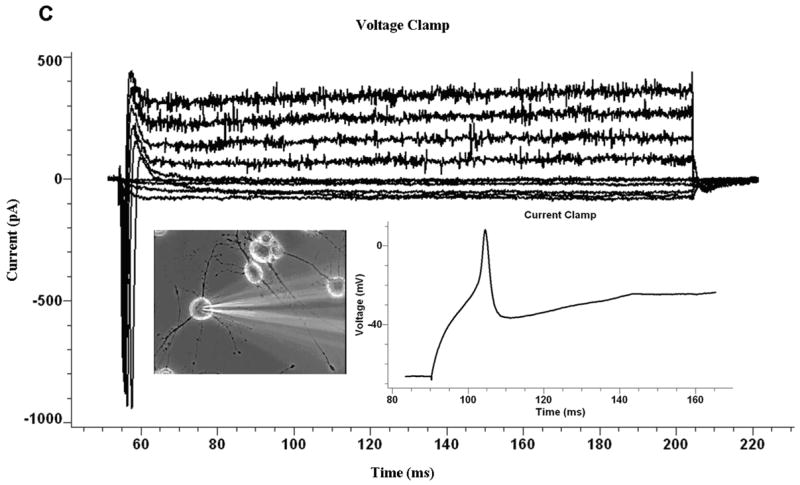

Whole cell patch clamp experiments were used to evaluate the electrical activity of the neurons. The duration of the regeneration process was approximately 25–30 days and led to a reticular network formation by day 35–40. Hence, we specifically choose two time points past this time period to study the electrical properties, day 37 and 44. In order to minimize electrophysiological heterogeneity, cells which were morphologically identical to cells previously characterized by immunocytochemistry were studied. Fig 4 shows representative pictures of the neurons selected for the study. Morphologically, the neurons selected resembled ventral horn motoneurons. For comparison, the properties of several large cells with radial symmetry, which most resembled astrocytes, oligodendroglia or ameboid microglia, were studied.

Figure 4.

Representative phase-contrast pictures of the cells which were used to quantify the electrical properties. A and B. Phase pictures of the neurons in control culture at day 44. C. Phase pictures of the neurons after glutamate treatment at day 37 (G37). D. Phase pictures of the neurons after glutamate treatment at day 44 (G44). E. Phase pictures of the neurons after serotonin treatment at day 37 (S37). F. Phase pictures of the neurons after serotonin treatment at day 44 (S44). G. Phase pictures of the neurons after acetylcholine chloride treatment at day 37 (A37). H. Phase pictures of the neurons after acetylcholine chloride treatment at day 44 (A44). I. Phase pictures of the neurons after glutamate+serotonin treatment at day 37 (GS37). J and K. Phase pictures of the neurons after glutamate+serotonin treatment at day 44 (GS44). L, M, N and O. Phase pictures of the neurons after glutamate+serotonin followed by acetylcholine chloride treatment at day 44 (GSA44).

Initially, the electrical properties of the neurons in long-term culture were evaluated as controls. Similar to what has been reported previously, at day 37 (C37) and 44 (C44), 29% and 28% of the cells exhibited single action potentials (AP), respectively (Table 2). Research during last two decades have indicated that during the neural circuit development in the spinal cord, retina, and hippocampus, the electrical stimulation originates due to spontaneous network activity and paracrine neurotransmitter signaling involved in sculpturing the network activity (Gonzalez-Islas and Wenner, 2006; Katz and Shatz, 1996; Manent and Represa, 2007). Based on this, we speculated that administration of neurotransmitters could mimic the similar developmental condition and could further improve the functional characteristics of the regenerating adult spinal cord cells.

We selected three excitatory neurotransmitters, serotonin, glutamate and acetylcholine-chloride for study. The rational for selecting these three neurotransmitters was to test the hypothesis of whether the application of extracellular neurotransmitters improve the electrical properties of the regenerating adult spinal cord neurons. The detailed protocol, dosages and timing of the neurotransmitter application has been described in the methods section and is outlined in Fig 5 A, B. The first set of electrophysiological experiments was completed by incubating the cultures separately in three different neurotransmitters: glutamate, serotonin, and acetylcholine-chloride (Table 2). The neurotransmitter treatments were performed on 30 day old cultures. The electrical properties were evaluated at two different time intervals, 7 and 14 days after neurotransmitter incubation. 33% of the cells fired single AP’s following 7 days of glutamate incubation (G37). There was a 10% increase in the number of cells firing AP’s following 14 days of glutamate incubation (G44). 41% and 44% of the total cells exhibited single AP’s after 7 (S37) and 14 (S44) days of serotonin treatment, respectively. Compared to the control, there was a decrease in the number of cells exhibiting AP’s after 7 (16% for A37) and 14 (19% for A44) days of acetylcholine chloride incubation.

Figure 5.

Electrophysiological recordings from glutamate+serotonin→ acetylcholine chloride (GSA44) treated cultures. A. Scheme for single neurotransmitters application. B. Scheme for multiple neurotransmitters application. C. Representative trace for voltage and current clamp of a neuron firing a single action potential after multiple neurotransmitter applications at day 44. D. Representative trace for voltage and current clamp recordings of a double action potential firing neuron after multiple neurotransmitter applications at day 44. E. Representative trace for voltage and current clamp recordings of a neuron firing multiple action potentials after multiple neurotransmitter applications at day 44.

In the second set of experiments, the cultures were incubated with multiple neurotransmitters. 50% of the cells fired single AP’s when co-administered glutamate+serotonin (GS37) and then incubated in culture for 7 days. Whereas, after 14 days of incubation (GS44), 56% of the cells fired a single AP, and 2 out of 16 neurons fired double AP’s. To determine if the addition of acetylcholine-chloride after co-administration of glutamate+serotonin could influence the electrical properties of the recovering neurons, acetylcholine-chloride was added after 5 days. The electrical properties were then evaluated at day 14 after the initial co-administration of glutamate+serotonin. We observed a significant improvement (p = 0.05) in the electrical properties of the regenerating neurons using this treatment regime. 60% of the neurons that followed this temporal application of the three neurotransmitter treatments (GSA44) fired either single, double or multiple action-potentials (Fig 5 C, D, E). The results are summarized in Table 2 and a double classification Chi-squared test was used to quantify any significant difference (p = 0.05) between different treatments as compared to the control.

Interestingly, the inward current was the only parameter that differed significantly (p = 0.01) between the different groups of neurons (Table 3). As compared to the neurons in the control culture (C37), the serotonin (S44), glutamate+serotonin (GS44), and glutamate+serotonin→ acetylcholine chloride (GSA44) treated neurons expressed significantly more inward current. We also observed more inward current from the neurons which were incubated in glutamate+serotonin→ acetylcholine chloride for 14 days (GSA44) as compared to those cultures which were incubated in either serotonin (S37), serotonin (S44), acetylcholine chloride (A37) or acetylcholine chloride (A44).

Similarly, an increase in inward current was also exhibited by neurons which were incubated in glutamate+serotonin for 14 days (GS44) as compared to those cultures which were incubated in either S37, S44, G44, A37, or A44. There was also a significant improvement in the electrical properties of the neurons which were incubated for 14 days in glutamate+serotonin (GS44) as compared to those which were only incubated for 7 days (GS37) (Table 3). These results illustrate that full functional recovery was achieved after 14 days following treatment of the cultures with the multiple neurotransmitter protocol.

The cultures were also analyzed for differences in resting potential, membrane resistance, membrane capacitance, inward current, outward current, AP height and AP width. These results are summarized in Table 3 and expressed as mean ± SE. One-way ANOVA and statistical tests, assuming unequal variance (Tamhane’s test), were used for pairwise comparisons of the mean. There were no significant differences (p = 0.01) in resting potential, membrane resistance, membrane capacitance, outward current, AP height and AP width between the different experimental groups of the cultured neurons.

The three neurotransmitters which were used for this study are all excitatory neurotransmitters and depolarize the cell membrane. Synaptically released glutamate, serotonin, acetylcholine and other neurotransmitters have been studied in detail (Webster, 2001). However, very little in vivo information has been available about the origin and function of the pool of glutamate (Baker et al., 2002; Timmerman and Westerink, 1997), serotonin (Adell et al., 2002), acetylcholine (David and Pitman, 1982; Descarries et al., 1997; Guo et al., 2005) and other neurotransmitters which appear to be present in micromolar concentrations in the extracellular space outside the synaptic cleft (Nyitrai et al., 2006). Our results support one hypothesis in that extracellular neurotransmitters may be involved in shaping synaptic activity in vivo (Baker et al., 2002; Timmerman and Westerink, 1997; Coggan et al., 2005). Thus, these results raise the distinct possibility that this strategy could also be exploited to differentiate stem cells to form neurons as well as be applied to establish functional recovery of damaged neurons in vivo.

Our results now provide one of the missing components that enable full adult CNS neuron regeneration and demonstrate that the adult CNS neurons can re-establish their electrophysiological functionality in a fashion similar to that found during embryonic development. In addition, we have demonstrated for the first time that it is necessary to have an application of neurotransmitters, as well as growth factors, to enable the injured adult CNS neurons to regain their full electrical functionality. This new ability to culture functional adult CNS neurons will be of importance in unlocking molecular pathologies to neurological disorders such as SCI, ALS, Parkinsons and Alzhiemers which are specific to adult differentiated neurons.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) at NIH, grant #5RO1NS050452-03. We wish to thank the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB), Iowa City, IA for providing the ISLET-1 and MO-1 antibodies. We would also like to thank Steve Lambert and Dalton Dietrich for their helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Dumont RJ, Okonkwo DO, Verma RS, Hurlbert RJ, Boulos PT, Ellegala DB, Dumont AS. Acute spinal cord injury, part I: Pathophysiologic mechanisms. Clinical Neuropharmacology. 2001;24:254–264. doi: 10.1097/00002826-200109000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab ME. Repairing the injured spinal cord. Science. 2002;295:10291031. doi: 10.1126/science.1067840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das M, Bhargava N, Gregory C, Riedel L, Molnar P, Hickman JJ. Adult rat spinal cord culture on an organosilane surface in a novel serum-free medium. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2005;41:343–348. doi: 10.1007/s11626-005-0006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das M, Patil S, Bhargava N, Kang JF, Riedel LM, Seal S, Hickman JJ. Auto-catalytic ceria nanoparticles offer neuroprotection to adult rat spinal cord neurons. Biomaterials. 2007;28:1918–1925. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer GJ. Regeneration and proliferation of embryonic and adult rat hippocampal neurons in culture. Exp Neurol. 1999;159:237–247. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedoroff S, Richardson A, editors. Protocols for neural cell culture:Serum-free media for neural cell cultures Adult and embryonic. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer GJ. Isolation and culture of adult rat hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci Methods. 1997;71:143–155. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(96)00136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans MS, Collings MA, Brewer GJ. Electrophysiology of embryonic, adult and aged rat hippocampal neurons in serum-free culture. J Neurosci Methods. 1998;79:37–46. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(97)00159-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzouz M, Ralph GS, Storkebaum E, Walmsley LE, Mitrophanous KA, Kingsman SM, Carmeliet P, Mazarakis ND. VEGF delivery with retrogradely transported lentivector prolongs survival in a mouse ALS model. Nature. 2004;429:413–417. doi: 10.1038/nature02544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambrechts D, Storkebaum E, Morimoto M, Del-Favero J, Desmet F, Marklund SL, Wyns S, Thijs V, Andersson J, van Marion I, Al-Chalabi A, Bornes S, Musson R, Hansen V, Beckman L, Adolfsson R, Pall HS, Prats H, Vermeire S, Rutgeerts P, Katayama S, Awata T, Leigh N, Lang-Lazdunski L, Dewerchin M, Shaw C, Moons L, Vlietinck R, Morrison KE, Robberecht W, Van Broeckhoven C, Collen D, Andersen PM, Carmeliet P. VEGF is a modifier of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in mice and humans and protects motoneurons against ischemic death. Nat Genet. 2003;34:383–394. doi: 10.1038/ng1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottenstein JEaHAL., editor. Cell Culture in the Neurosciences. Plenum Press; New York and London: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bregman BS, McAtee M, Dai HN, Kuhn PL. Neurotrophic factors increase axonal growth after spinal cord injury and transplantation in the adult rat. Exp Neurol. 1997;148:475–494. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman B, Kleinfeld D, Ip NY, Verge VM, Moulton R, Boland P, Zlotchenko E, Lindsay RM, Liu L. BDNF and NT-4/5 exert neurotrophic influences on injured adult spinal motor neurons. J Neurosci. 1995;15:1044–1056. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-02-01044.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato AC, Lindsay RM. Overlapping and additive effects of neurotrophins and CNTF on cultured human spinal cord neurons. Exp Neurol. 1994;130:196–201. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1994.1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masu Y, Wolf E, Holtmann B, Sendtner M, Brem G, Thoenen H. Disruption of the CNTF gene results in motor neuron degeneration. Nature. 1993;365:27–32. doi: 10.1038/365027a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim RW, Prevette D, Yin QW, Collins F, MacDonald J. Control of embryonic motoneuron survival in vivo by ciliary neurotrophic factor. Science. 1991;251:1616–1618. doi: 10.1126/science.2011743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravenscroft MS, Bateman KE, Shaffer KM, Schessler HM, Jung DR, Schneider TW, Montgomery CB, Custer TL, Schaffner AE, Liu QY, Li YX, Barker JL, Hickman JJ. Developmental neurobiology implications from fabrication and analysis of hippocampal neuronal networks on patterned silane- modified surfaces. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1998;120:12169–12177. [Google Scholar]

- Das M, Gregory CA, Molnar P, Riedel LM, Wilson K, Hickman JJ. A defined system to allow skeletal muscle differentiation and subsequent integration with silicon microstructures. Biomaterials. 2006;27:4374–4380. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das M, Molnar P, Devaraj H, Poeta M, Hickman JJ. Electrophysiological and morphological characterization of rat embryonic motoneurons in a defined system. Biotechnol Prog. 2003;19:1756–1761. doi: 10.1021/bp034076l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das M, Rumsey JW, Gregory CA, Bhargava N, Kang JF, Molnar P, Riedel LM, Guo X, Hickman JJ. Embryonic Motoneuron-Skeletal Muscle Co-culture in a Defined System. Neuroscience. 2007;146:481–488. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.01.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auditore JV, Wade L, Olson EJ. Occurrence of N-acetyl-L-glutamic acid in the human brain. J Neurochem. 1966;13:1149–1155. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1966.tb04272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto M, Naito T. Patent, US. Patent Storm Eiken Chemical Co., Ltd; USA: 1998. Animal cell culturing media containing N-acetyl-L-glutamic acid. [Google Scholar]

- Das M, Wilson KW, Molnar P, Hickman JJ. Differentiation of skeletal muscle and integration of myotubes with silicon microstructures using serumfree medium and a synthetic silane substrate. Nature Protocols. 2007;2:1795–801. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Islas C, Wenner P. Spontaneous network activity in the embryonic spinal cord regulates AMPAergic and GABAergic synaptic strength. Neuron. 2006;49:563–575. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LC, Shatz CJ. Synaptic activity and the construction of cortical circuits. Science. 1996;274:1133–1138. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manent JB, Represa A. Neurotransmitters and brain maturation: early paracrine actions of GABA and glutamate modulate neuronal migration. Neuroscientist. 2007;13:268–279. doi: 10.1177/1073858406298918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster R, editor. Neurotransmitters, Drugs and Brain Function. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Baker DA, Xi ZX, Shen H, Swanson CJ, Kalivas PW. The origin and neuronal function of in vivo nonsynaptic glutamate. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9134–9141. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-20-09134.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmerman W, Westerink BH. Brain microdialysis of GABA and glutamate: what does it signify? Synapse. 1997;27:242–261. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199711)27:3<242::AID-SYN9>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adell A, Celada P, Abellan MT, Artigas F. Origin and functional role of the extracellular serotonin in the midbrain raphe nuclei. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2002;39:154–180. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00182-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David JA, Pitman RM. The effects of axotomy upon the extrasynaptic acetylcholine sensitivity of an identified motoneurone in the cockroach Periplaneta americana. J Exp Biol. 1982;98:329–341. doi: 10.1242/jeb.98.1.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descarries L, Gisiger V, Steriade M. Diffuse transmission by acetylcholine in the CNS. Prog Neurobiol. 1997;53:603–625. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(97)00050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo JZ, Liu Y, Sorenson EM, Chiappinelli VA. Synaptically released and exogenous ACh activates different nicotinic receptors to enhance evoked glutamatergic transmission in the lateral geniculate nucleus. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:2549–2560. doi: 10.1152/jn.00339.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyitrai G, Kekesi KA, Juhasz G. Extracellular level of GABA and Glu: in vivo microdialysis-HPLC measurements. Curr Top Med Chem. 2006;6:935–940. doi: 10.2174/156802606777323674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coggan JS, Bartol TM, Esquenazi E, Stiles JR, Lamont S, Martone ME, Berg DK, Ellisman MH, Sejnowski TJ. Evidence for ectopic neurotransmission at a neuronal synapse. Science. 2005;309:446–451. doi: 10.1126/science.1108239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]