Abstract

Objective To develop and validate practical prognostic models for death at 14 days and for death or severe disability six months after traumatic brain injury.

Design Multivariable logistic regression to select variables that were independently associated with two patient outcomes. Two models designed: “basic” model (demographic and clinical variables only) and “CT” model (basic model plus results of computed tomography). The models were subsequently developed for high and low-middle income countries separately.

Setting Medical Research Council (MRC) CRASH Trial.

Subjects 10 008 patients with traumatic brain injury. Models externally validated in a cohort of 8509.

Results The basic model included four predictors: age, Glasgow coma scale, pupil reactivity, and the presence of major extracranial injury. The CT model also included the presence of petechial haemorrhages, obliteration of the third ventricle or basal cisterns, subarachnoid bleeding, midline shift, and non-evacuated haematoma. In the derivation sample the models showed excellent discrimination (C statistic above 0.80). The models showed good calibration graphically. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test also indicated good calibration, except for the CT model in low-middle income countries. External validation for unfavourable outcome at six months in high income countries showed that basic and CT models had good discrimination (C statistic 0.77 for both models) but poorer calibration.

Conclusion Simple prognostic models can be used to obtain valid predictions of relevant outcomes in patients with traumatic brain injury.

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury is a leading cause of death and disability worldwide. Every year, about 1.5 million affected people die and several millions receive emergency treatment.1 2 Most of the burden (90%) is in low and middle income countries.3

Clinicians treating patients often make therapeutic decisions based on their assessment of prognosis. According to a 2005 survey, 80% of doctors believed that an accurate assessment of prognosis was important when they made decisions about the use of specific methods of treatment such as hyperventilation, barbiturates, or mannitol.4 A similar proportion considered that this was important in deciding whether or not to withdraw treatment. Assessment of prognosis was also deemed important for counselling patients and relatives. Only a third of doctors, however, thought that they accurately assessed prognosis.4

Prognostic models are statistical models that combine data from patients to predict outcome and are likely to be more accurate than simple clinical predictions.5 The use of computer based prediction of outcome in patients with traumatic brain injury increases the use of certain therapeutic interventions in those predicted to have a good outcome and reduces their use in those predicted to have a poor outcome.6

Many prognostic models have been reported but none are widely used. A recent systematic review offers possible explanations.7 Most models were developed on small samples, most were methodologically flawed, and few were validated in external populations. Few were presented in a clinically practical way, nor were they developed in populations from low and middle income countries, where most trauma occurs.

The Medical Research Council (MRC) CRASH (corticosteroid randomisation after significant head injury) trial is the largest clinical trial conducted in patients with traumatic brain injury and presents a unique opportunity to develop a prognostic model.8 9 The trial prospectively included patients within eight hours of the injury, used standardised definitions of variables, and achieved almost complete follow-up at six months. Furthermore, the large sample size guarantees precise and valid predictions. The high recruitment of patients from low and middle income countries means that models developed with these data are relevant to these settings.

We have developed and validated prognostic models for death at 14 days and death and disability at six months in patients with traumatic brain injury.

Methods

Patients—The study cohort was all 10 008 patients enrolled in the trial. Adults with traumatic brain injury, who had a score on the Glasgow coma scale of 14 or less, and who were within eight hours of injury, were eligible for inclusion in the trial.

Outcomes—Death of a patient was recorded on an early outcome form that was completed at hospital discharge, death, or 14 days after randomisation (whichever occurred first). Unfavourable outcome (death or severe disability) at six months was defined with the Glasgow outcome scale (see box). The scale comprises five categories: death, vegetative state, severe disability, moderate disability, and good recovery. For the purpose of this analysis, we dichotomised outcomes into favourable (moderate disability or good recovery) and unfavourable (dead, vegetative state, or severe disability).10

Category and definition on Glasgow outcome scale

Good recovery: able to return to work or school

Moderate disability: able to live independently; unable to return to work or school

Severe disability: able to follow commands/unable to live independently

Persistent vegetative state: unable to interact with environment; unresponsive

Dead

Prognostic variables—For the prognostic model we considered age, sex, cause of injury, time from injury to randomisation, Glasgow coma score at randomisation, pupil reactivity, results of computed tomography, whether the patient had sustained a major extracranial injury, and level of income in country (high or low-middle income countries, as defined by the World Bank) (see table A on bmj.com).11 We adjusted analyses for treatment within the trial as this was related to outcome, and we did not find interaction between treatment and the potential predictors.8 9

Analysis—Most of the variables collected in the CRASH trial have been previously associated with prognosis in traumatic brain injury, so we included all of them in a first multivariable logistic regression analysis.12 We excluded variables that were not significant at 5% level. We quantified each variable’s predictive contribution by its z score (the model coefficient divided by its standard error). We explored linearity between age and mortality at 14 days and Glasgow coma score and mortality at 14 days. Interactions between country income level and all the other predictors were evaluated with a likelihood ratio test. Because there were few data missing, we performed a complete case analysis.

Prognostic models—We developed different models for each of the two outcomes: a basic model, which included only clinical and demographic variables, and a CT model, which also included results of computed tomography.

Performance of the model—We assessed performance of the models in terms of calibration and discrimination. Calibration was assessed graphically and with the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. Discrimination was assessed with the C statistic (an equivalent concept to area under the receiver operator characteristic curve).13

Internal validation—The internal validity of the final model was assessed by the bootstrap re-sampling technique. Regression models were estimated in 100 models. For each of 100 bootstrap samples we refitted and tested the model on the original sample to obtain an estimate of predictive accuracy corrected for bias. This showed no overoptimism in any of the final model’s predictive C statistics.

External validation—A good prognostic model should be generalisable to populations different to those in which it was derived.14 We externally validated the models in an external cohort of 8509 patients with moderate and severe traumatic brain injury from 11 studies conducted in high income countries (the IMPACT (international mission for prognosis and clinical trial) dataset).15

Score development—We developed a clinical score based on regression coefficients. A web based version of the model was developed to be accessible to clinicians internationally.

Results

General characteristics

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the patients. More of the patients were men (81%) and more came from low-middle income countries (75%). More than half (58%) of participants were included within three hours of injury. Road traffic crashes were the most common cause of injury (65%) and 79% of the participants underwent computed tomography. A total of 1948 patients (19%) died in the first two weeks, 2323 patients (24%) were dead at six months, and 3556 patients (37%) were dead or severely dependent at six months.

Table 1.

General characteristics of study population

| Total (n=10 008) | Low-middle income countries (n=7 526) | High income countries (n=2 482) | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years): | ||||

| <20 | 12.3 | 12.5 | 11.8 | |

| 20-24 | 17.0 | 17.8 | 14.4 | |

| 25-29 | 13.0 | 13.5 | 11.2 | |

| 30-34 | 10.7 | 10.9 | 10.1 | |

| 35-44 | 17.9 | 18.5 | 15.9 | |

| 45-54 | 12.5 | 12.3 | 13.3 | |

| ≥55 | 16.7 | 14.5 | 23.4 | |

| Mean (SD) | 37 (17.1) | 35.8 (16) | 40.6 (19.4) | <0.001 |

| Sex: | ||||

| Female | 19.0 | 18.3 | 21.1 | 0.002 |

| Male | 81.0 | 81.7 | 78.9 | |

| Hours since injury : | ||||

| <1 | 26.8 | 24.0 | 35.2 | |

| 1-3 | 31.0 | 30.1 | 33.7 | |

| >3 | 42.3 | 45.9 | 31.1 | |

| Mean (SD) | 3.4 (2.7) | 3.6 (2.8) | 2.8 (2.0) | <0.001 |

| Cause of head injury: | ||||

| Road traffic crash | 65.1 | 69.9 | 50.2 | <0.001 |

| Fall >2 meters | 13.3 | 11.1 | 20.0 | |

| Other | 21.7 | 19.0 | 29.8 | |

| Total Glasgow coma score: | ||||

| Mild (13-14) | 30.2 | 29.4 | 32.6 | <0.001 |

| Moderate (9-12) | 30.4 | 32.6 | 23.6 | |

| Severe (3-8) | 39.5 | 38.0 | 43.8 | |

| Pupil reactivity: | ||||

| Both reactive | 82.8 | 83.5 | 80.7 | <0.001 |

| One reactive | 6.3 | 6.2 | 6.3 | |

| None reactive | 8.2 | 8.0 | 9.1 | |

| Unable to assess | 2.7 | 2.3 | 3.9 | |

| Major extracranial injury: | ||||

| No | 77.3 | 77.3 | 77.5 | 0.801 |

| Yes | 22.7 | 22.7 | 22.5 | |

| Computed tomography: | ||||

| No scan | 21.1 | 24.0 | 12.0 | <0.001 |

| Normal scan | 22.8 | 20.0 | 30.2 | <0.001 |

| Petechial haemorrhages | 28.7 | 28.7 | 28.7 | 0.970 |

| Obliteration of 3rd ventricle or basal cisterns | 23.4 | 28.6 | 9.6 | <0.001 |

| Subarachnoid bleed | 31.6 | 33.5 | 26.4 | <0.001 |

| Midline shift | 14.6 | 15.9 | 11.1 | <0.001 |

| Non-evacuated haematoma | 27.1 | 27.3 | 26.5 | 0.475 |

| Evacuated haematoma | 12.7 | 14.4 | 7.9 | <0.001 |

| Outcomes: | ||||

| Mortality at 14 days | 19.5 | 20.7 | 16.0 | <0.001 |

| Death or severe disability at 6 months | 37.2 | 36.8 | 38.5 | 0.150 |

*P value for comparison between low-middle income countries and high income countries.

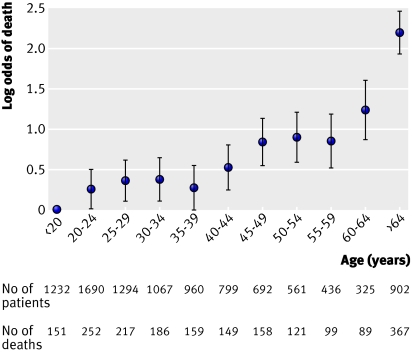

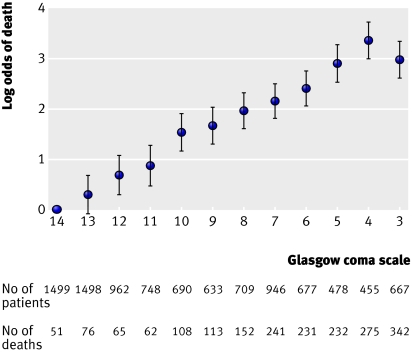

The relation between age and the log odds of death within 14 days showed no association until the age of 40 and a linear increase afterwards. The relation between Glasgow coma score and mortality at 14 days was reasonably linear and we therefore included the coma score as a continuous variable (figs 1 and 2) . The relation with unfavourable outcome at six months showed similar patterns.

Fig 1 Relation between age and mortality at 14 days

Fig 2 Relation between Glasgow coma scale and mortality at 14 days

Low-middle v high income countries

In comparison with patients from high income countries, those from low-middle income countries were younger, more likely to be male, were recruited later, had less severe traumatic brain injury (as defined by Glasgow coma score and pupil reactivity), and more often had abnormal results on computed tomography. Road traffic crashes were a more common cause of traumatic brain injury. Although patients from low-middle income countries experienced higher mortality at 14 days (odds ratio 1.94, 95% confidence interval 1.64 to 2.30), there was no significant difference in unfavourable outcome at six months.

There were significant interactions between the country’s income level and several predictors and so we developed two models, one for low-middle income countries and another for high income countries. Older age was a stronger predictor of 14 day mortality in high income countries (interaction P<0.001), and lower Glasgow coma score was a stronger predictor in low-middle income countries (interaction P=0.003). Obliteration of the third ventricle and a non-evacuated haematoma were both associated with a higher risk in high income countries (interaction P<0.001 and P=0.03, respectively).

Multivariable predictive models

We developed eight models altogether: basic and CT models for predicting two outcomes in two settings (low-middle and high income countries).

Basic models—We included four predictors in the basic model: age, Glasgow coma score, pupil reactivity, and the presence of major extracranial injury (table 2). Glasgow coma score was the strongest predictor of outcome in low-middle income countries and age was the strongest predictor in high income countries, while the absence of pupil reactivity was the third strongest predictor in both regions.

Table 2.

Multivariable basic predictive models (excluding data from computed tomography*). Figures are odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) with z scores

| Prognostic variables | Mortality at 14 days | Death or severe disability at 6 months | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High income countries (n=2294) | Low-middle income countries (n=7412) | High income countries (n=2185) | Low-middle income countries (n=7119) | ||||

| Age† | 1.72 (1.62 to 1.83), 14.08 | 1.47 (1.40 to 1.54), 14.10 | 1.73 (1.64 to 1.82), 15.99 | 1.70 (1.63 to 1.77), 18.58 | |||

| GCS‡ | 1.24 (1.19 to 1.29), 10.22 | 1.39 (1.35 to 1.42), 25.60 | 1.22 (1.18 to 1.25), 12.84 | 1.42 (1.39 to 1.45), 30.64 | |||

| Pupil reactivity: | |||||||

| Both | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.00 | |||

| One | 2.57 (1.65 to 4.00), 4.17 | 1.91 (1.53 to 2.39), 5.69 | 2.43 (1.62 to 3.66), 4.26 | 2.01 (1.59 to 2.56), 5.81 | |||

| None | 5.49 (3.70 to 8.15), 8.45 | 3.92 (3.14 to 4.90), 12.07 | 3.28 (2.20 to 4.89), 5.85 | 4.54 (3.38 to 6.11), 10.03 | |||

| Major extracranial injury: | |||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 1.53 (1.11 to 2.09), 2.62 | 1.15 (0.99 to 1.34), 1.78 | 1.62 (1.26 to 2.07), 3.82 | 1.73 (1.51 to 1.99), 7.76 | |||

| C statistic | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.81 | 0.84 | |||

GCS=Glasgow coma scale.

*Includes age, GCS, sex, hours since injury, cause of injury, pupil reactivity, and presence of major extracranial injury.

†Per 10 year increase after 40 years.

‡Per decrease of each value of GCS.

CT models—The following characteristics on computed tomography were strongly associated with the outcomes in addition to the predictors included in the basic models: presence of petechial haemorrhages, obliteration of the third ventricle or basal cisterns, subarachnoid bleeding, midline shift, and non-evacuated haematoma (table 3). Obliteration of the third ventricle and midline shift were the strongest predictors of mortality at 14 days, and non-evacuated haematoma was the strongest predictor of unfavourable outcome at six months.

Table 3.

Multivariable predictive models with computed tomography*. Figures are odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) with z scores

| Prognostic variables | Mortality at 14 days | Death or severe disability at 6 months | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High income countries (n=2030) | Low-middle income countries (n=5635) | High income countries (n=1955) | Low-middle income countries (n=5 394) | ||||

| Age† | 1.73 (1.62 to 1.84), 13.33 | 1.46 (1.39 to 1.54), 12.54 | 1.73 (1.63 to 1.83), 14.94 | 1.72 (1.64 to 1.81), 17.74 | |||

| GCS‡ | 1.18 (1.12 to 1.23), 6.87 | 1.27 (1.24 to 1.31), 16.68 | 1.18 (1.14 to 1.22), 9.83 | 1.34 (1.30 to 1.37), 22.32 | |||

| Pupil reactivity: | |||||||

| Both | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.00 | |||

| One | 2.00 (1.25 to 3.20), 2.88 | 1.45 (1.14 to 1.86), 2.97 | 2.12 (1.39 to 3.24), 3.47 | 1.54 (1.20 to 1.99), 3.35 | |||

| None | 4.00 (2.58 to 6.20), 6.21 | 3.12 (2.46 to 3.97), 9.31 | 2.83 (1.84 to 4.35), 4.73 | 3.56 (2.60 to 4.87), 7.92 | |||

| Major extracranial injury: | |||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 1.53 (1.10 to 2.13), 2.53 | 1.08 (0.91 to 1.28), 0.89 | 1.55 (1.20 to 1.99), 3.37 | 1.61 (1.38 to 1.88), 6.03 | |||

| Findings on computed tomography: | |||||||

| Petechial haemorrhages | 1.15 (0.83 to 1.59), 0.84 | 1.26 (1.07 to 1.47), 2.82 | 1.21 (0.95 to 1.55), 1.56 | 1.49 (1.29 to 1.73), 5.33 | |||

| Obliteration of 3rd ventricle or basal cisterns | 4.46 (2.97 to 6.68), 7.23 | 1.99 (1.69 to 2.35), 8.25 | 2.21 (1.49 to 3.30), 3.95 | 1.53 (1.31 to 1.79), 5.30 | |||

| Subarachnoid bleed | 1.48 (1.09 to 2.02), 2.51 | 1.33 (1.14 to 1.55), 3.60 | 1.62 (1.26 to 2.08), 3.79 | 1.20 (1.04 to 1.39), 2.49 | |||

| Midline shift | 2.77 (1.82 to 4.21), 4.77 | 1.78 (1.44 to 2.21), 5.35 | 1.93 (1.30 to 2.87), 3.24 | 1.86 (1.48 to 2.32), 5.42 | |||

| Non-evacuated haematoma | 2.06 (1.49 to 2.84), 4.40 | 1.48 (1.24 to 1.76), 4.43 | 1.72 (1.33 to 2.22), 4.15 | 1.68 (1.43 to 1.97), 6.34 | |||

| C statistic | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.84 | |||

GCS=Glasgow coma scale.

*Includes age, GCS, pupil reactivity, presence of major extra cranial injury, and all findings on computed tomography.

†Per 10 year increase after 40 years.

‡Per decrease of each value of GCS.

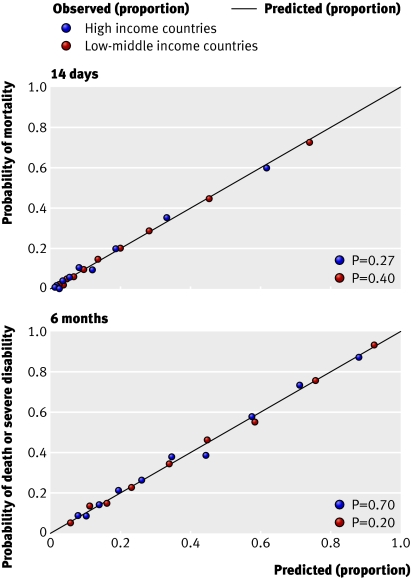

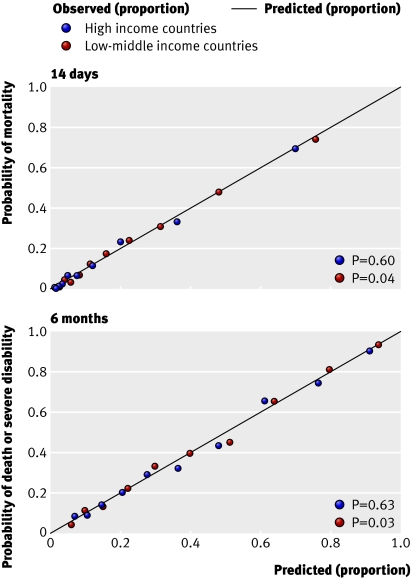

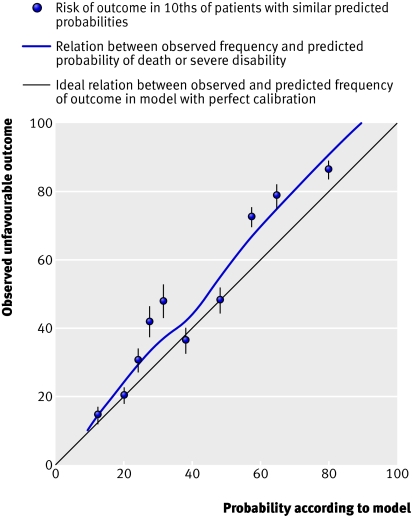

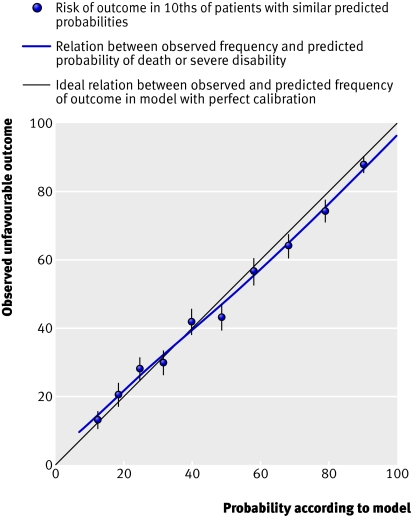

Performance of models—All models showed excellent discrimination, with C statistics over 0.80 (tables 2 and 3). Calibration in all models was adequate and six out of the eight models had good calibration when evaluated with the Hosmer-Lemeshow test (figs 3 and 4) .

Fig 3 Calibration of basic models using expected and observed probabilities of mortality at 14 days (top) and death or severe disability at six months (bottom) in patient with traumatic brain injury according to income level of country. P value is for Hosmer-Lemeshow test

Fig 4 Calibration of computed tomography models using expected and observed probabilities of mortality at 14 days (top) and death or severe disability at six months (bottom) in patient with traumatic brain injury according to income level of country. P value is for Hosmer-Lemeshow test

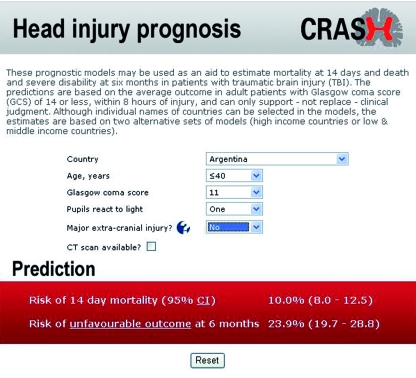

Clinical score—Individual scores and their respective probability of outcome can be obtained from our web based calculator (www.crash2.lshtm.ac.uk/). By entering the values of the predictors, we can obtain the expected risk of death at 14 days and of death or severe disability at six months. Figure 5 shows a sample screenshot of the predictions for a 26 year old patient from a low and middle income country (Argentina), with a Glasgow coma score of 11, one pupil reactive, and absence of a major extra cranial injury. According to the basic model this patient has a probability of death at 14 days of 10% and a 23.9% risk of death or severe disability at six months. A good agreement is evident between observed and predicted outcome by the web calculator (figs 3 and 4).

Fig 5 Screenshot of web based calculator available at www.crash2.lshtm.ac.uk/. If CT scan available box is ticked, calculator displays additional CT variables

External validation—Because an external cohort of patients from low-middle income countries was not available, we validated the models in patients from high income countries only. The IMPACT dataset used for the validation did not include mortality at 14 days and so we could validate only models for unfavourable outcome at six months. We validated the basic model with the variables age, Glasgow coma score, and pupil reactivity. We did not include the variable “major extracranial injury” as it was not available in the validation sample. For the CT models, we added obliteration of the third ventricle or basal cisterns, subarachnoid bleeding, midline shift, and non-evacuated haematoma to the basic model. Similarly, we excluded the variable “petechial haemorrhages” as this was not available in the validation sample. For the validation process we first ran these models in the CRASH trial cohort and we then applied the corresponding coefficients in the validation sample. Although discrimination was, as expected, lower than in the original data, it was still quite good for both the basic and CT models (C statistic 0.77 for both models). The calibration was excellent for the CT model but poorer for the basic model (figs 6 and 7).

Fig 6 External validation of basic model for death or severe disability at six months in IMPACT database

Fig 7 External validation of CT model for death or severe disability at six months in IMPACT database

Discussion

We have developed web based prognostic models for predicting two clinically relevant outcomes in patients with traumatic brain injury using variables that are available at the bedside. The models have excellent discrimination and good fit with both internal and external validation. We have reported on differences in outcomes and on the strength of predictors of outcomes, according to whether patients are from high or low-middle income countries.

Older age, low Glasgow coma score, absent pupil reactivity, and the presence of major extracranial injury predict poor prognosis. All of these variables have been previously identified as prognostic factors for poor outcome in traumatic brain injury.12 Glasgow coma score showed a clear linear relation with mortality. Our finding that mortality in patients with Glasgow coma score of 3 was lower than in patients with a score of 4 may be because scores of sedated patients are reported as 3. Increasing age was associated with worse outcomes but this association was apparent only after age 40. A similar threshold has been reported elsewhere.16 17 Plausible explanations for this include extracranial comorbidities, changes in brain plasticity, or differences in clinical management associated with increasing age. The presence of “obliteration of third ventricle or basal cisterns” on computed tomography was associated with the worst prognosis at 14 days. This is supported by recent findings that absence of basal cisterns is the strongest predictor of six month mortality.18 We also found—as previously reported—the independent prognostic value of traumatic subarachnoid haemorrhage.19

Patients from low-middle income countries had worse early prognosis than those from high income countries. Regional differences in outcome after traumatic brain injury have previously been reported between Europe and North America, but the difference in mortality between low-middle and high income countries has not been explored.20

The strength of association between some predictors and outcomes differed by region. A low Glasgow coma score had an even worse prognosis in patients from low-middle income countries compared with patients from high income countries. This might relate to quality of care or it could be that low Glasgow coma score in high income countries is associated with greater use of sedation, rather than to severity of traumatic brain injury. Increasing age had a worse prognosis in high income countries compared with low-middle income countries. This is because of even lower risks at younger ages in high income countries, while both have similar risks at older ages. Regarding computed tomography, some abnormal findings were stronger predictors in high income countries. This could be because of better technology and therefore more accurate diagnosis with computed tomography.

A systematic review identified over 100 prognostic models for patients with traumatic brain injury, but methodological quality was adequate in only a few.7 As with our models, two of the more methodologically robust models showed similarly good discrimination but worse calibration.17 21 They too included Glasgow coma score, age, pupil reactivity, and results of computed tomography as predictors, but, unlike our models, they did not include the presence of major extracranial injury, and none of them included patients from low-middle income countries.

Strengths and weakness of the study

Our study’s strengths are the use of a well described cohort of patients, prospective and standardised collection of data on prognostic factors, low loss to follow-up, and the use of a validated outcome measure at a fixed time after the injury. All of these factors provide reassurance about the internal validity of our models. The large sample size in relation to the number of prognostic variables examined is another particular strength. In relation to its external validity, only a few prognostic models have been developed from patients in low-middle income countries, and to the best of our knowledge the models we developed are the first with a large sample size and adequate methods.7 The external validation confirmed the discriminatory ability of the models in patients from high income countries and showed good calibration for the computed tomography model. Unlike most published prognostic models, we included the complete spectrum of patients with traumatic brain injury, ranging from mild to severe. Finally, the data required to make predictions with the model are easily available to clinicians, and we have developed a web based risk calculator.

There are some limitations. The data from which the models were developed come from a clinical trial and this could therefore limit external validity. For example, patients were recruited within eight hours of injury and we cannot estimate the accuracy of the models for patients evaluated beyond this time. Nevertheless, the CRASH trial was a pragmatic trial that did not require any additional tests and therefore included a diversity of “real life” patients. Another limitation was that for the validation we were forced to exclude the variables major extracranial injury and petechial haemorrhages because they were not available in the IMPACT sample. Neither of these variables, however, was among the stronger predictors. The external validation showed good discriminatory ability, but this was somewhat lower than in the original data. This may be explained by a more homogeneous selected case mix in these other trials, which included only patients with moderate and severe Glasgow coma score.

Implications of the study

Most of the burden of traumatic brain injury is in low-middle income countries, where case fatality is higher and resources are limited. We found that several predictors differed in their strength of association with outcome according to income level of country, suggesting that it may be inappropriate to extrapolate from models for high income countries to poorer settings. We have developed a methodologically valid, simple, and accurate model that may help decisions about health care for individual patients. It is important to emphasise, however, that while prognostic models may complement clinical decision making they cannot and should not replace clinical judgment. This is particularly important in the context of judgments about the withdrawal of care or clinical triage. These prognostic models can also help in the design and analysis of clinical trials, through prognostic stratification, and can be used in clinical audit by allowing adjustment for case mix.22

Future research

The differences found between the prognostic models for low-middle and high income countries are important. Although most of the burden of trauma occurs in low-middle income countries, most research takes place in high income countries.3 A recent systematic review found that few prognostic models for traumatic brain injury were developed in low-middle income countries.7 More research is therefore needed to obtain reliable data from these settings. An improved understanding of the differences between these regions might also clarify the mechanisms of predictors that are not immediately obvious when we analyse a homogeneous population. Because our models were developed with data from a clinical trial, and validated only in patients from high income countries, further prospective validation in independent cohorts is needed to strengthen the generalisability of the models. Future research could also evaluate different ways, or formats, for presenting the models to physicians; their use in clinical practice; and whether ultimately they have any impact on the management and outcomes of patients with traumatic brain injury.

What is already known on this topic

Traumatic brain injury is a leading cause of death and disability worldwide with most cases occurring in low-middle income countries

Prognostic models may improve predictions of outcome and help in clinical research

Many prognostic models have been published but methodological quality is generally poor, sample sizes small, and only a few models have included patients from low-middle income countries

What this study adds

In a basic model prognostic indicators included age, Glasgow coma scale, pupil reactivity, and the presence of major extracranial injury

In a CT model additional indicators were the presence of petechial haemorrhages, obliteration of the third ventricle or basal cisterns, subarachnoid bleeding, mid-line shift, and non-evacuated haematoma

The strength of predictors of outcomes varies according to whether patients are from high or low-middle income countries

These prognostic models, that include simple variables, are available on the internet (www.crash2.lshtm.ac.uk/)

Supplementary Material

CRASH trial collaborators by country (number of patients randomised)

Albania (41 patients): Fatos Olldashi (national coordinator), Itan Muzha (Central Military University Hospital National Trauma Centre, 35); Nikolin Filipi ( University Hospital “Mother Teresa” Tirana, 6).

Argentina (359 patients): Roberto Lede, Pablo Copertari, Carolina Traverso, Alejandro Copertari (IAMBE—national and regional coordinators for southern Latin America); Enrique Alfredo Vergara, Carolina Montenegro, Roberto Ruiz de Huidobro, Pantaleón Saladino (Hospital San Bernardo, 106); Karina Surt, José Cialzeta, Silvio Lazzeri (Hospital Escuela Jose de San Martin, 52); Gustavo Piñero, Fabiana Ciccioli (Hospital Municipal “Dr Leonidas Lucero,” 37); Walter Videtta, María Fernanda Barboza (Hospital Dr Ramón Carrillo, 35); Silvana Svampa, Victor Sciuto (Hospital Castro Rendon, 28); Gustavo Domeniconi, Marcelo Bustamante (Hospital Zonal General De Agudos “Heroes de Malvinas,” 27); Maximiliano Waschbusch (Policlinico Sofia T de Santamarina. 20); María Paula Gullo (Hospital Municipal Dr Hector J D’Agnillo, 17); Daniel Alberto Drago (Hospital Nacional Profesor Alejandro Posadas, 11); Juan Carlos Arjona Linares (Hospital Español de Mendoza, 10); Luis Camputaro (Hospital Italiano, 10); Gustavo Tróccoli (Hospital “Dr José Penna,” 5); Hernán Galimberti (Hospital Aleman, 1).

Australia (13 patients): Mandy Tallott (Gold Coast Hospital, 13).

Austria (21 patients): Christian Eybner, Walter Buchinger (Waldviertelklinikum Standort Horn, 17); Sylvia Fitzal (Wilhelminenspital der Stadt Wien, 4).

Belgium (403 patients): Guy Mazairac (national coordinator), Véronique Oleffe, Thierry Grollinger, Philippe Delvaux, Laurent Carlier (Centre Hospitalier Regional de Namur, 356); Veronique Braet (AZ Klina Hospital, 34); Jean-Marie Jacques (Hospital of Jolimont, 11); Danielle de Knoop (Clinique Saint-Luc, 2).

Brazil (119 patients): Luiz Nasi (national coordinator), Humberto Kukhuyn Choi, Mara Schmitt (Hospital de Pronto Socorro de Porto Alegre, 113); André Gentil (Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, 5); Flavio Nacul (Clínica São Vicente, 1).

Chile (3 patients): Pedro Bedoya Barrios (Hospital Regional Copiapo, 3).

China (87 patients): Chen Xinkang, Lin Shao Hua, Huang Han Tian (Zhongshan City People’s Hospital, 79); Cai Xiaodong (Sheng Zheng Second People’s Hospital, 8).

Colombia (832 patients): Wilson Gualteros, Alvaro Ardila Otero (Hospital Universitario San Jorge, 216); Miguel Arango (national coordinator, regional coordinator for northern Latin America and Caribbean), Juan Ciro, Hector Jaramillo (Gloria GarciaClinica Las Americas, 199); Ignacio Gonzalez, Carolina Gomez (Hospital General de Medellin, 119); Arturo Arias, Marco Fonseca, Carlos Mora (Hospital Erasmo Meoz, 90); Edgar Giovanni Luna Cabrera, José Luis Betancurth, Porfirio Muñoz (Hospital Departamental de Nariño, 51); Jesus Alberto Quiñónez, Maria Esther Gonzalez Castillo (Hospital San Andres, 37); Orlando Lopez (Hospital Federico Lleras, 31); Rafael Perez Yepes, Diana Leon Cuellar, Gerson Paez (Hospital El Tunal, 24); Hernán Delgado Chaves, Pablo Emilio Ordoñez (Hospital Civil de Ipiales, 21); Ricardo Plata, Martha Pineda (Hospital Universitario del Valle, 15); Libardo Enrique Pulido (Hospital Regional de Duitama, 12); John Sergio Velez Jaramillo (Hospital Timothy Britton, 12); Carlos Rebolledo (Organización Clinica General del Norte, 5).

Costa Rica (20 patients): Oscar Palma (Hospital México, 20).

Cuba (404 patients): Caridad Soler (national coordinator); Irene Pastrana, Raul Falero (Hospital Abel Santamaria Cuadrado, 77); Mario Domínguez Perera, Agustín Arocha García, Raydel Oliva (Hospital Universitario “Arnaldo Milián Castro,” 55); Hubiel López Delgado (Hospital Provincial Docente “Manuel Ascunce Domenech,” 43); Aida Madrazo Carnero, Boris Leyva López (Hospital VI Lenin, 42); Angel Lacerda Gallardo, Amarilys Ortega Morales (Hospital General de Morón, 40); Humberto Lezcano (Hospital General Universitario “Carlos Manuel de Cèspedes,” 38); Marcos Iraola Ferrer (Hospital Universitario “Dr Gustavo Aldereguia Lima,” 37); Irene Zamalea Bess, Gladys Rivas Canino (Hospital Miguel Enriquez, 36); Ernesto Miguel Piferrer Ruiz (Hospital Clínico-Quirúrgico Docente “Saturnino Lora,” 32); Orlando Garcia Cruz (Centro de Investigaciones Médico-Quirúrgicas, 4).

Czech Republic (961 patients): Petr Svoboda (national coordinator), Ilona Kantorová, Jiřĺ Ochmann, Peter Scheer, Ladislav Kozumplík, Jitka Maršová (Research Institute for Special Surgery and Trauma, 852); Karel Edelmann (Masaryk Hospital, 41); Ivan Chytra, Roman Bosman (Charles University Hospital, Plzen, 35); Hana Andrejsová (University Hospital Hradec Kralove, 15); Jan Pachl (Hospital Kralovske Vinohgrady, 9); Jan Bürger (Hospital Pribram, 7); Filip Kramar (Univerzity Karlovy Neurochirurgicka Klinika, 2).

Ecuador (258 patients): Mario Izurieta Ulloa (national coordinator), Luis Gonzalez, Alberto Daccach, Antonio Ortega, Stenio Cevallos (Hospital Luis Vernaza, 202); Boris Zurita Cueva (Hospital de la Policia Guayaquil, 16); Marcelo Ochoa (Hospital Jose Carrasco Arteaga, 11); Jaime Velásquez Tapia (Hospital Naval, 11); Jimmy Hurtado (Clínica Central, 8); Miguel Chung Sang Wong (Hospital Militar de Guayaquil, 5); Roberto Santos (Hospital Regional del IESS “Dr Teodoro Maldonado Carbo,” 5).

Egypt (775 patients): Hussein Khamis (national coordinator), Abdul Hamid Abaza, Abdalla Fekry, Salah El Kordy, Tarek Shawky (Mataria Teaching Hospital, 364); Hesham El-Sayed (national coordinator), Nabil Khalil, Nader Negm, Salem Fisal (Suez Canal University, 180); Mamdouh Alamin, Hany Shokry (Aswan Teaching Hospital, 160); Ahmed Yahia Elhusseny, Atif Radwan, Magdi Rashid (Zagazig University Hospital, 71).

Georgia (56 patients): Tamar Gogichaisvili (national coordinator), George Ingorokva, Nikoloz Gongadze (Neurosurgery Department of Tbilisi State Medical University, 55); Alexander Otarashvili (Tbilisi 4th Hospital, 1).

Germany (27 patients): Waltraud Kleist (Ernst Moritz Arndt University, 14); Mathias Kalkum (Kreiskrankenhaus Tirschenreuth, 8); Peter Ulrich (Klinikum Offenbach, 5).

Ghana (7 patients): Nii Andrews (Narh-Bita Hospital, 7).

Greece (20 patients): George Nakos (University Hospital of Ioannina, 8); Antonios Karavelis (University General Hospital of Larissa, 5); George Archontakis (Chania General Hospital “St George,” 4); Pavlos Myrianthefs (KAT Hospital of Athens, 3).

India (973 patients): Yadram Yadav, Sharda Yadav, R Khatri, Arvind Baghel (NSCB Medical College, 177); Mazhar Husain (national coordinator for north India), Deepak Jha (King George Medical College, 105); Wu Hoong Chhang, Manohar Dhandhania, Choden Fonning (North Bengal Neuro Research Centre, 65); S N Iyengar, Sanjay Gupta (G R Medical College, 51); R R Ravi, K S Bopiah, Ajay Herur (Medical Trust Hospital Kochi, 51); N K Venkataramana (national coordinator for south India), A Satish (Manipal Hospital, 50); K Bhavadasan, Raymond Morris, Ramesh S (Medical College Hospital Trivandrum, 50); A Satish (Abhaya Hospital, 42); Yashbir Dewan, Yashpal Singh (Christian Medical College, 36); Rajesh Bhagchandani, Sanjana Bhagchandani (Apex Hospital Bhopal, 32); Vijaya Ushanath Sethurayar (Meenakshi Mission Hospital and Research Centre, 32); Sojan Ipe, G Sreekumar (MOSC Medical College Hospital, 32); Manas Panigrahi, Agasti Reddy (Nizam’s Institute of Medical Sciences, 28); Varinder Khosla, Sunil Gupta (Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, 28); Haroon Pillay, Nisha Thomas (Baby Memorial Hospital, 25); Krishnamurthy Sridhar, Bobby Jose (V H S Hospital, 22); Nadakkavvkakan Kurian (Jubilee Mission Hospital, 20); Shanti Praharaj, Shibu Pillai (National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, 17); Ramana (Care Hospital (16); Sanjay Gupta, Smita Gupta (Sri Sai Hospital, 16); Dilip Kiyawat (Hirabi Cowasji Jehangir Medical Research Institute, 15); Kishor Maheshwari (Maheshwari Orthopaedic Hospital, 13); Dilip Panikar (Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences, 11); Jayant Chawla (Hartej Maternity and Nursing Home, 7); Satyanarayana Shenoy, Annaswamy Raja (Kasturba Medical College and Hospital, 7); Yeshomati Rupayana (Choitram Hospital and Research Centre, 6); Suryanarayan Reddy (Gowri Gopal Superspeciality Hospital, 6); Nelanuthala Mohan (Apex Hospital Visakhapatnam, 3); Shailesh Kelkar (Central India Institute of Medical Sciences, 3); Yadram Yadav (Marble City Hospital and Research Centre, 3); Jayant Chawla (Government Medical College Amritsar, 1); Mukesh Johri (Johri Hospital, 1); Yadram Yadav (National Hospital Jabalpur, 1).

Indonesia (238 patients): Nyoman Golden (national coordinator), Sri Maliawan (Sanglah General Hospital, 222); Achmad Fauzi, Umar Farouk (Sidoarjo General Hospital, 14).

Iran (233 patients): Esmaeel Fakharian, Amir Aramesh (Naghavi University Hospital, 110); Maasoumeh Eghtedari, Farhad Ahmadzadeh, Alireza Gholami (Fatemeh Zahra Hospital, 85); Maasoumeh Eghtedari, Farhad Ahmadzadeh (Social Security Hospital, 38).

Ireland (113 patients): Patrick Plunkett, Catherine Redican, Geraldine McMahon (St James’s Hospital, 113).

Italy (9 patients): Maria Giuseppina Annetta (Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, 4); Homère Mouchaty (Università di Firenze, 3); Eros Bruzzone (Ospedale San Martino, 2).

Ivory Coast (3 patients): Béatrice Harding (CHU de Cocody, 3).

Kenya (2 patients): Mahmood Qureshi (Aga Khan Hospital, 2).

Malaysia (176 patients): Zamzuri Idris, Jafri Abdullah NC, Ghazaime Ghazali, Abdul Rahman Izaini Ghani (Hospital University Science Malaysia, 162); Fadzli Cheah (Ipoh Specialist Hospital, 14).

Mexico (17 patients): Alfredo Cabrera (national coordinator); José Luis Mejía González (Hospital General Regional No 1, 12); José Luis Mejía González (Hospital General de Queretaro, 4); Jorge Loría-Castellanos (Hospital General Regional No 25, 1).

New Zealand (43 patients): Suzanne Jackson, Robyn Hutchinson (Dunedin Hospital, 43).

Nigeria (180 patients): Edward Komolafe (national coordinator), Augustine Adeolu, Morenikeji Komolafe (Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospitals, 77); Olusanya Adeyemi-Doro, Femi Bankole (Lagos University Teaching Hospital, 43); Bello Shehu, Victoria Danlami (Usmanu Danfodiyo University Teaching Hospital, 36); Olugbenga Odebode (University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital, 15); Kehinde Oluwadiya (Lautech Teaching Hospital, 7); Ahmed Sanni (Lagos State University Teaching Hospital, 1); Herb Giebel (Seventh Day Adventist Hospital, 1); Sushil Kumar (St Stephen’s Hospital, 1).

Pakistan (17 patients): Rashid Jooma (Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Centre, 17).

Panama (7 patients): Jose Edmundo Mezquita (Complejo Hospitalario M A Guerrero, 7).

Paraguay (10 patients): Carlos Ortiz Ovelar (Instituto de Prevision Social, 10).

Peru (8 patients): Marco Gonzales Portillo (Hospital Nacional “Dos de Mayo,” 6); Diana Rodriguez (national coordinator) (Hospital Nacional Arzobispo Loayza, 2).

Romania (319 patients): Laura Balica (national coordinator), Bogdan Oprita, Mircea Sklerniacof, Luiza Steflea, Laura Bandut (Spitalul Clinic de Urgenötùa Bucuresö ti, 282); Adam Danil, Remus Iliescu (Sfantum Pantelimon Hospital, 28); Jean Ciurea (Prof Dr D Bagdasar Clinical Emergency Hospital, 9).

Saudi Arabia (32 patients): Abdelazeem El-Dawlatly, Sherif Alwatidy (King Khalid University Hospital, 24); Walid Al-Yafi, Megahid El-Dawlatly (King Khalid National Guard Hospital, 8).

Serbia (23 patients): Ranka Krunic-Protic, Vesna Janosevic (Klinicki Centar Srbije, 23).

Singapore (23 patients): James Tan (national coordinator) (National Neuroscience Institute, 21); Charles Seah (Changi General Hospital, 2).

Slovakia (179 patients): Štefan Trenkler (national coordinator), Matuš Humenansky, Tatiana Stajančová (Reiman Hospital, 71); Ivan Schwendt, Anton Laincz (NsP Poprad, 39); Zeman Julius, Stano Maros (Nemocnica Bojnice, 25); Jozef Firment (FNsp Kosice, 12); Maria Cifraničova (NsP Trebisov, 11); Beata Sániová (Faculty Hospital in Martin, 10); Karol Kalig (NsP Ruzinov, 4); Soňa Medekova (NsP Nové Zámky, 3); Radovan Wiszt (NsP Liptovsky Mikulas, 2); NsP F D Roosevelt, 1); Ivan Mačuga (NsP Zilina, 1).

South Africa (366 patients): Bennie Hartzenberg (national coordinator), Grant du Plessis, Zelda Houlie (Tygerberg Academic Hospital, 307); Narendra Nathoo, Sipho Khumalo (Wentworth Hospital, 57); Ralph Tracey (Curamed Kloof Hospital, 1).

Spain (259 patients): Angeles Muñoz-Sánchez (national coordinator), Francisco Murillo-Cabezas NC, Juan Flores-Cordero, Dolores Rincón-Ferrari (Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocio, 133); Martin Rubi, Lopez Caler (Hospital Torrecárdenas, 37); Maite Misis del Campo, Luisa Bordejé Laguna (Hospital Universitario Germans Trias i Pujol, 32); Juan Manuel Nava (Hospital Mútua de Terrassa, 20); Miguel Arruego Minguillón (Hospital Universitario de Girona Dr Josep Trueta, 12); Alfonso Muñoz Lopez (Hospital Carlos Haya, 10); Luis Ramos-Gómez (Hospital General de La Palma, 6); Victoria de la Torre-Prados (Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria, 5); Romero Pellejero (Hospital General Yagüe, 4).

Sri Lanka (132 patients): Véronique Laloë (national coordinator), Bernhard Mandrella, Suganthan (Batticaloa General Hospital-Médecins Sans Frontières, 84); Sunil Perera (National Hospital of Sri Lanka, 39); Véronique Laloë, Kanapathipillai Mahendran (Point-Pedro Base Hospital, 9).

Switzerland (160 patients): Reto Stocker (national coordinator), Silke Ludwig (national coordinator) (University Hospital of Zurich, 133); Heinz Zimmermann (University Hospital Bern, 15); Urs Denzler (Kantonsspital Schaffhausen, 12).

Thailand (579 patients): Surakrant Yutthakasemsunt (national coordinator), Warawut Kittiwattanagul, Parnumas Piyavechvirat, Pojana Tapsai, Ajchara Namuang-jan (Khon Kaen Regional Hospital, 535); Upapat Chantapimpa (Chiangrai Prachanuko Hospital, 12); Chanothai Watanachai, Pusit Subsompon (Rayong Hospital, 11); Wipurat Pussanakawatin, Pensri Khunjan (Krabi Hospital, 10); Sakchai Tangchitvittaya, Somsak Nilapong (Suratthani Hospital, 8); Tanagorn Klangsang, Wibul Taechakosol (Roi Et Hospital, 2); Atirat Srinat (Lampang Hospital, 1).

Tunisia (63 patients): Zouheir Jerbi (national coordinator), Nebiha Borsali-Falfoul, Monia Rezgui (Hospital Habib Thameur, 63).

Turkey (2 patients): Nahit Cakar (Istanbul Medical Faculty, 2).

Uganda (43 patients): Hussein Ssenyonjo, Olive Kobusingye (Makerere Medical School, 43).

UK (1391 patients): Gabrielle Lomas, David Yates, Fiona Lecky (Hope Hospital, 209); Anthony Bleetman, Alan Baldwin, Emma Jenkinson, Shiela Pantrini (Birmingham Heartlands Hospital, 123); James Stewart, Nasreen Contractor, Trudy Roberts, Jim Butler (North Manchester General Hospital, 85); Alan Pinto, Diane Lee (Royal Albert Edward Infirmary, 83); Nigel Brayley, Karly Robbshaw, Clare Dix (Colchester General Hospital, 79); Sarah Graham, Sue Pye (Whiston Hospital, 69); Marcus Green, Annie Kellins (Selly Oak Hospital, 61); Chris Moulton, Barbara Fogg (Royal Bolton Hospital, 51); Rowland Cottingham, Sam Funnell, Utham Shanker (Eastbourne District General Hospital, 50); Claire Summers, Louise Malek (Trafford General Hospital, 41); Rowland Cottingham (national coordinator), Christopher Ashcroft, Jacky Powell (Royal Sussex County Hospital, 38); Steve Moore, Stephanie Buckley (Countess of Chester Hospital, 36); Mandy Grocutt, Steve Chambers (Worthing Hospital, 34); Amanda Morrice, Helen Marshall (Medway Maritime Hospital, 29); Julia Harris, Wendy Matthews, Jane Tippet (Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, 28); Simon Mardell, Fiona MacMillan, Anita Shaw (Furness General Hospital, 27); Pramod Luthra, Gill Dixon (Royal Oldham Hospital, 26); Mohammed Ahmed, John Butler, Mike Young (Stepping Hill Hospital, 26); Sue Mason, Ian Loveday (Northern General Hospital, 25); Christine Clark, Sam Taylor (Blackburn Royal Infirmary, 23); Paul Wilson (Cheltenham General Hospital, 23); Kassim Ali, Stuart Greenwood (Fairfield General Hospital, 23); Martin White, Rosa Perez (Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother Hospital, 21); Sam Eljamel (Ninewells Hospital and Medical School, 19); Jonathan Wasserberg, Helen Shale (Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham, 18); Colin Read, John McCarron (Russell’s Hall Hospital, 18); Aaron Pennell (Princess Alexandra Hospital, 16); Gautam Ray (Princess Royal Hospital, 14); John Thurston, Emma Brown (Darent Valley Hospital, 13); Lawrence Jaffey, Michael Graves (Royal Liverpool University Hospital, 12); Richard Bailey, Nancy Loveridge (Chesterfield and North Derbyshire Royal Hospital, 10); Geraint Evans, Shirleen Hughes, Major Kafeel Ahmed (Withybush General Hospital, 10); Jeremy Richardson, Claire Gallagher (Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, 8); Titus Odedun, Karen Lees (Ormskirk and District General Hospital, 8); David Foley, Nick Payne (Queen Mary’s Hospital, 8); Alan Pennycook, Carl Griffiths (Arrowe Park Hospital, 6); David Moore, Denise Byrne (City Hospital Birmingham, 5); Sunil Dasan (St Helier Hospital, 4); Ashis Banerjee, Steve McGuinness (Whittington Hospital, 4); Claude Chikhani (Doncaster Royal Infirmary, 2); Nigel Zoltie, Ian Barlow (Leeds General Infirmary, 2); Ian Stell (Bromley Hospital, 1); William Hulse, Jacqueline Crossley (Harrogate District Hospital, 1); Laurence Watkins (Institute of Neurology, 1); Balu Dorani (Queen Elizabeth Hospital Gateshead, 1).

Vietnam (2 patients)—Truong Van Viet (Cho Ray Hospital, 2).

Contributors: The writing committee comprised Pablo Perel (Chair), Miguel Arango, Tim Clayton, Phil Edwards, Edward Komolafe, Stuart Poccock, Ian Roberts, Haleema Shakur, Ewout Steyerberg, and Surakrant Yutthakasemsunt

Funding: The MRC CRASH trial was funded by the UK Medical Research Council.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: All MRC CRASH collaborators obtained local ethics or research committee approval.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Bruns J Jr, Hauser WA. The epidemiology of traumatic brain injury: a review. Epilepsia 2003;44(suppl 10):2-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleminger S, Ponsford J. Long term outcome after traumatic brain injury. BMJ 2005;331:1419-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hofman K, Primack A, Keusch G, Hrynkow S. Addressing the growing burden of trauma and injury in low- and middle-income countries. Am J Public Health 2005;95:13-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perel P, Wasserberg J, Ravi RR, Shakur H, Edwards P, Roberts I. Prognosis following head injury: a survey of doctors from developing and developed countries. J Eval Clin Pract 2007;13:464-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee KL, Pryor DB, Harrell FE Jr, Califf RM, Behar VS, Floyd WL, et al. Predicting outcome in coronary disease. Statistical models versus expert clinicians. Am J Med 1986;80:553-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murray LS, Teasdale GM, Murray GD, Jennett B, Miller JD, Pickard JD, et al. Does prediction of outcome alter patient management? Lancet 1993;341:1487-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perel P, Edwards P, Wentz R, Roberts I. Systematic review of prognostic models in traumatic brain injury. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2006;6:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.CRASH Trial Collaborators. Effect of intravenous corticosteroids on death within 14 days in 10 008 adults with clinically significant head injury (MRC CRASH trial): randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2004;364:1321-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.CRASH Trial Collaborators. Final results of MRC CRASH, a randomised placebo-controlled trial of intravenous corticosteroid in adults with head injury-outcomes at 6 months. Lancet 2005;365:1957-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jennett B, Bond M. Assessment of outcome after severe brain damage. Lancet 1975;i:480-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.World Bank. World development indicators Washington, DC: World Bank, 2006

- 12.Brain Trauma Foundation (US) AAoNS. Management and prognosis of severe traumatic brain injury New York: 2000. www.braintrauma.org/site/DocServer/Prognosis_Guidelines_for_web.pdf?docID=241

- 13.Harrell FE Jr, Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med 1996;15:361-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Justice AC, Covinsky KE, Berlin JA. Assessing the generalizability of prognostic information. Ann Intern Med 1999;130:515-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maas AI, Marmarou A, Murray GD, Teasdale SG, Steyerberg EW. Prognosis and clinical trial design in traumatic brain injury: the IMPACT study. J Neurotrauma 2007;24:232-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hukkelhoven CW, Steyerberg EW, Rampen AJ, Farace E, Habbema JD, Marshall AF, et al. Patient age and outcome following severe traumatic brain injury: an analysis of 5600 patients. J Neurosurg 2003;99:666-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Signorini DF, Andrews PJD, Jones PA, Wardlaw JM, Miller JD. Predicting survival using simple clinical variables: a case study in traumatic brain injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1999;66:20-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maas AI, Hukkelhoven CW, Marshall LF, Steyerberg EW. Prediction of outcome in traumatic brain injury with computed tomographic characteristics: a comparison between the computed tomographic classification and combinations of computed tomographic predictors. Neurosurgery 2005;57:1173-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wardlaw JM, Easton VJ, Statham P. Which CT features help predict outcome after head injury? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002;72:188-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hukkelhoven CW, Steyerberg EW, Farace E, Habbema JD, Marshall LF, Maas AI. Regional differences in patient characteristics, case management, and outcomes in traumatic brain injury: experience from the tirilazad trials. J Neurosurg 2002;97:549-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hukkelhoven CW, Steyerberg EW, Habbema JD, Farace E, Marmarou A, Murray GD, et al. Predicting outcome after traumatic brain injury: development and validation of a prognostic score based on admission characteristics. J Neurotrauma 2005;22:1025-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Altman DG. Systematic reviews in health care: Systematic reviews of evaluations of prognostic variables. BMJ 2001;323:224-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.