Abstract

One of the most vexing problems facing structural genomics efforts and the biotechnology enterprise in general is the inability to efficiently produce functional proteins due to poor folding and insolubility. Additionally, protein misfolding and aggregation has been linked to a number of human diseases, such as Alzheimer’s. Thus, a robust cellular assay that allows for direct monitoring, manipulation, and improvement of protein folding could have a profound impact. We report the development and characterization of a genetic selection for protein folding and solubility in living bacterial cells. The basis for this assay is the observation that protein transport through the bacterial twin-arginine translocation (Tat) pathway depends on correct folding of the protein prior to transport. In this system, a test protein is expressed as a tripartite fusion between an N-terminal Tat signal peptide and a C-terminal TEM1 β-lactamase reporter protein. We demonstrate that survival of Escherichia coli cells on selective medium expressing a Tat-targeted test protein/β-lactamase fusion correlates with the solubility of the test protein. Using this assay, we isolated solubility-enhanced variants of the Alzheimer’s Aβ42 peptide from a large combinatorial library of Aβ42 sequences, thereby confirming that our assay is a highly effective selection tool for soluble proteins. By allowing the bacterial Tat pathway to exert folding quality control on expressed target protein sequences, we have generated a powerful tool for monitoring protein folding and solubility in living cells, for molecular engineering of solubility-enhanced proteins or for the isolation of factors and/or cellular conditions that stabilize aggregation-prone proteins.

Keywords: protein structure/folding, stability and mutagenesis, protein trafficking/sorting, peptide/fragment isolation, cDNA, cloning, synthesis of peptides and proteins

The expression of heterologous proteins represents a cornerstone of the biotechnology enterprise. A major challenge stems from the fact that protein folding and solubility can be problematic in the crowded cellular milieu, where the macromolecular concentration can reach 300–400 mg/mL (Lorimer 1996; Ellis and Minton 2003). As a result, many commercially important proteins misfold and aggregate when expressed in a heterologous host (Georgiou and Valax 1996; Makrides 1996; Baneyx and Mujacic 2004). Similarly, protein misfolding and aggregation is the pathological hallmark of more than a dozen diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease (Radford and Dobson 1999; Ross and Poirier 2004). Thus, a genetic selection for protein solubility, where the term “solubility” is used here to denote both the chemical solubility related to folding and the absence of aggregation or degradation, could have a number of important consequences. First, it could be used to rapidly improve the soluble yield of a protein by optimizing its primary sequence (Roodveldt et al. 2005) or its cellular folding environment (Wall and Pluckthun 1995). For this purpose, a selection is advantageous because analyzing large numbers of mutant sequences without automation can become time- and cost-prohibitive. Second, it could be used to assay for cofactors and small molecules that promote correct folding or inhibit the aggregation of heterologously expressed proteins or proteins associated with human disease (e.g., Alzheimer’s Aβ42 peptide) (Williams et al. 2005).

Development of a robust in vivo selection for stably expressed proteins has been challenging because of limitations associated with detecting and reporting intra-cellular solubility. Nonetheless, a handful of cellular protein folding assays have been reported to date. Most of these systems have capitalized on the observation that a misfolded target protein will often induce improper folding of a C-terminally fused reporter protein or protein fragment (Maxwell et al. 1999; Waldo et al. 1999; Wigley et al. 2001; Cabantous et al. 2005) or will induce a specific gene response (Lesley et al. 2002). A drawback of these approaches is that solubility is reported indirectly, i.e., reporter protein activity must correlate with the folding of the fusion partner. An undesired outcome is that certain reporter proteins can remain active even when the target protein to which they are fused is insoluble (Philibert and Martineau 2004) or aggregated (Tsumoto et al. 2003). Our goal was to engineer a genetic selection for protein solubility that does not require coupling between the folding behavior of a target protein and reporter activity but rather relies on authentic cellular quality control.

In bacterial cells, specific targeting and transport mechanisms are required to move proteins along transport pathways from their site of synthesis in the cytoplasm to extra-cytoplasmic destinations. One such pathway, the twin-arginine translocation (Tat) pathway, is capable of delivering folded proteins across biological membranes via translocation machinery comprised of the Tat (A/E)BC proteins (Berks 1996; Settles et al. 1997; Weiner et al. 1998). Recent in vivo studies demonstrate a clear ability of the Tat pathway to selectively discriminate between properly folded and misfolded proteins in vivo and suggest the existence of a folding quality control mechanism intrinsic to the process (Sanders et al. 2001; DeLisa et al. 2003). Here we have exploited this natural quality control feature to report protein solubility directly in bacterial cells by engineering a tripartite fusion of a Tat signal peptide, a target protein, and mature β-lactamase (Bla). Since Bla only confers antibiotic resistance on Gram-negative bacteria when present in the periplasmic space, it minimally acts to report the cellular localization of the fusion protein and not its solubility per se. A similar tripartite construct was recently employed by Benkovic and coworkers to select for correct nucleic acid reading frame (Lutz et al. 2002). It was hypothesized by these authors and later demonstrated (Gerth et al. 2004) that the Tat quality control mechanism unavoidably biased the reading frame selection toward folded structures. While this was not a desirable characteristic for reading frame selection, it appeared to hold great promise for a genetic reporter of protein solubility. Accordingly, in the present study, we confirm that the inherent folding quality control of the Tat pathway, in concert with other intrinsic mechanisms of in vivo quality control (e.g., protease degradation, insoluble aggregation), can be harnessed to reveal the genuine solubility of a wide array of prokaryotic and eukaryotic proteins targeted for Tat transport.

Results

Folding quality control of the Tat pathway

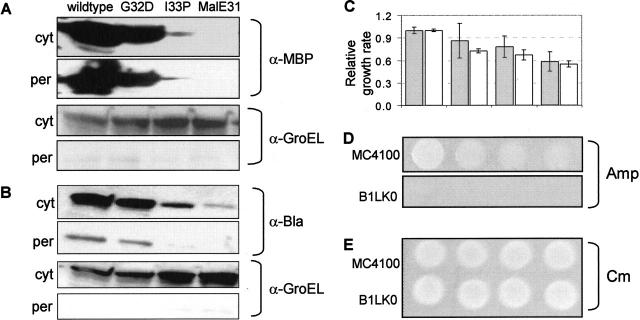

Previous data indicated that the Tat system possesses an innate quality control mechanism; however, this was limited to proteins that required disulfide bonds, cofactor insertion, or subunit interactions to stabilize their native structure (Rodrigue et al. 1999; Sanders et al. 2001; DeLisa et al. 2003; Jack et al. 2004). It was not clear from these studies the extent to which the Tat quality control feature extended to other proteins that form off-pathway intermediates for reasons unrelated to disulfide bond formation or cofactor insertion. This is important because early events during protein biogenesis that lead to thermodynamically or kinetically trapped intermediates often precede disulfide bond formation, which is typically a later step in folding. Therefore, we evaluated Tat transport of Escherichia coli maltose binding protein (MBP) and three well-characterized MBP mutants prone to increasing levels of off-pathway folding intermediates, in order: MBP-G32D, MBP-I33P, and MalE31 (G32D/I33P) (Betton and Hofnung 1996). The difference between wild-type MBP and MalE31 is >100-fold in their in vivo solubility which corresponds to in vitro stability measurements (−5.5 kcal/mol to −9.5 kcal/mol) (Betton and Hofnung 1996). The coding region for the Tat-specific E. coli TMAO reductase (TorA) signal peptide plus the first four residues of mature TorA (ssTorA, amino acid residues 1–46) (DeLisa et al. 2002) was fused upstream of the gene encoding the mature form of each MBP (residues 26–396), creating four ssTorA-MBP chimeras in pTrc99A. The ssTorA signal was selected based on its noted fidelity for the Tat pathway (DeLisa et al. 2003). Cell fractionation of wild type MC4100 E. coli was performed to track subcellular localization and revealed that the periplasmic yield of each MBP mutant was consistent with its level of soluble expression in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2A, below). Notably, the insoluble fractions were largely devoid of any of the ssTorA-MBP fusion proteins (data not shown), which was particularly surprising for the I33P and MalE31 constructs. While little is known about the mechanistic details of the Tat quality control mechanism, this can best be explained by the observation that transport-incompetent Tat substrates are efficiently degraded as part of a poorly characterized “housecleaning” mechanism associated with the Tat system (Santini et al. 1998; DeLisa et al. 2003). Importantly, no transport of any MBP was ever observed in a ΔtatC mutant strain (B1LK0) that is incapable of Tat transport (Bogsch et al. 1998; data not shown), confirming that this phenomenon was Tat-specific. The simple fact that the quantity of soluble protein in the cytoplasm reflected the quantity of that protein transported to the periplasm suggested that the Tat pathway could serve as a useful framework for assessing recombinant protein solubility.

Figure 2.

Proofreading of misfolded proteins by the Tat system. An equivalent number of cells were harvested 6 h after induction and fractionated into cytoplasmic (cyt) and periplasmic (per) fractions using the method of ice-cold osmotic shock described in the Materials and Methods section. (A) Subcellular distribution of MBP (wt), MBP-G32D, MBP-I33P, and MalE31 (MBP-G32D/I33P) expressed via the Tat pathway (ssTorA) and probed by anti-MBP serum. For these experiments, E. coli strain HS3018 (Shuman 1982) lacking a chromosomal copy of malE was used. GroEL was used simply as a fractionation marker by probing with anti-GroEL serum. Increased GroEL expression in the presence of misfolded MalE31 is documented. Cytoplasmic lanes were overloaded until MBP-I33P bands were clearly visible. An equivalent number of cells were harvested 6 h after induction and fractionated into cytoplasmic (cyt) and periplasmic (per) fractions. Cells expressing ssTorA-MBP(wt)-Bla, ssTorA-MBP(G32D)-Bla, ssTorA-MBP(I33P)-Bla, and ssTorA-MalE31-Bla were assayed for subcellular distribution of the fusion protein (B) by probing with Bla anti-serum. GroEL was used as a fractionation marker by probing with GroEL antiserum. (C) Relative periplasmic Bla activity as determined by the rate of nitrocefin hydrolysis (gray bars) and relative growth rate as determined by 96-well plate liquid growth assays (white bars). All data were normalized to the activity (0.146 abs units/ sec) and the growth rate (0.387 h−1) of cells expressing ssTorA-MBP(wt)-Bla. Lastly, growth on solid medium by spot plating 5 μL of an equivalent number of cells on LB agar supplemented with 100 μg/mL Amp (D) or 25 μg/mL Cm (E).

A Tat-based solubility reporter

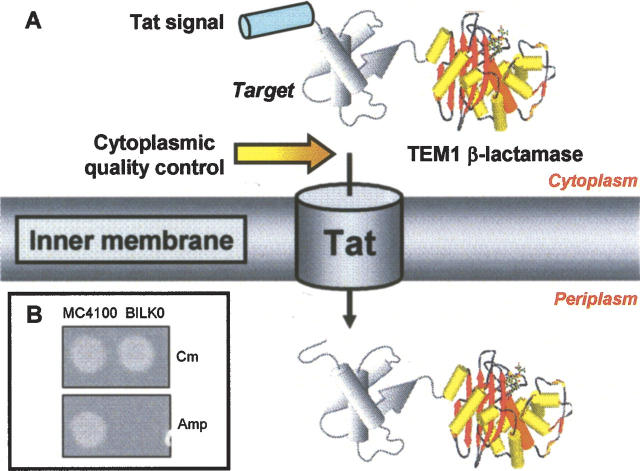

To exploit the quality control feature of the Tat pathway for the development of a broad-spectrum protein folding assay, we engineered a genetic selection that employed a tripartite fusion of ssTorA, a “target” protein, and mature TEM1 β-lactamase (Bla) (Fig. 1A). The premise for this assay is as follows: A stable target protein is exported to the periplasm via Tat and, by virtue of the Bla fusion, confers Amp resistance to E. coli cells expressing the ssTorA-target-Bla chimera. To verify that Bla is indeed capable of reporting Tat-dependent transport, we constructed vector pTMB with no gene in the target position that expresses ssTorA-Bla. Upon expression of ssTorA-Bla in MC4100 and B1LK0, we only observed an Amp-resistant phenotype in MC4100 cells (Fig. 1B) indicating that Bla was specifically transported by the Tat pathway.

Figure 1.

Exploiting the Tat pathway’s folding quality control feature for monitoring protein solubility. (A) A tripartite fusion protein is created between a Tat signal peptide (e.g., ssTorA), a target protein, and the TEM1 β-lactamase protein (Bla). Discrimination between folded and misfolded target sequences is accomplished by the Tat machinery such that only correctly folded, soluble proteins are localized to the periplasm. Concomitant delivery of Bla to the E. coli periplasm confers an Amp resistant phenotype to cells. (B) The growth of MC4100/pTMB and B1LK0/pTMB cells on LB agar plates supplemented with either 25 μg/mL Cm (control) or 100 μg/mL Amp, indicating unambiguously that Bla can be used as a Tat-specific reporter.

Next, we inserted the gene encoding mature MBP or one of the three destabilized mutants into the target position of pTMB. Upon expression in MC4100, it was found that the amount of soluble ssTorA-MBP-Bla in the cytoplasm correlated both to the periplasmic yield of the fusion protein and the cellular growth rate in Amp (Fig. 2B,C). In the case of poorly folded ssTorA-MBP sequences (I33P and MalE31), the low cytoplasmic levels are best explained by increased degradation as a result of incompatibility with the Tat pathway (Santini et al. 1998; DeLisa et al. 2003). The differences in MBP solubility reported by our assay were in agreement with previous reports of wild type and variant MBP solubility in the cytoplasm of E. coli (Betton and Hofnung 1996; Wigley et al. 2001) and confirm that we can effectively report intermediate changes in target protein solubility. Furthermore, relative growth levels on solid medium containing Amp could be used to discriminate between cells expressing stable and unstable versions of MBP (Fig. 2D). As no growth was observed for B1LK0 cells on Amp expressing any of the ssTorA-MBP-Bla fusions, we conclude that the fusions are exclusively routed via the Tat pathway. Importantly, B1LK0 cells carrying reporter plasmids grew equally well as MC4100 in the absence of Amp (Fig. 2E), confirming that B1LK0’s inability to grow on Amp was due to a blockage in transport and not due to a general growth defect.

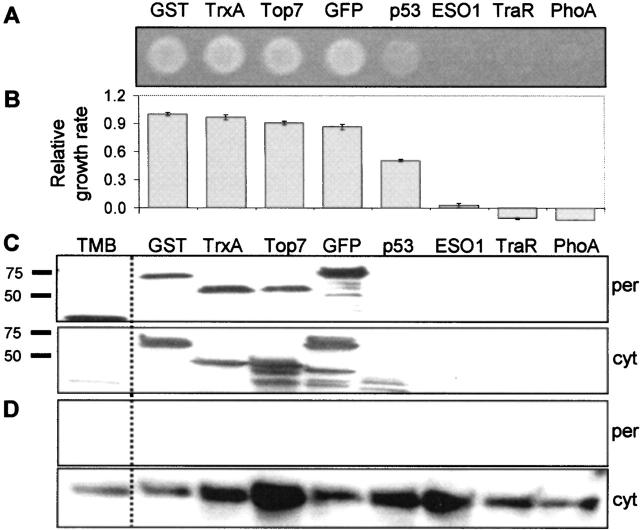

To explore the generality of this assay, eight additional proteins of prokaryotic and eukaryotic origin were tested using our folding reporter. These target proteins ranged from the highly stable E. coli proteins glutathione S-transferase (GST) and thioredoxin (TrxA) to E. coli alkaline phosphatase (PhoA), a periplasmic enzyme that is unstable in the cytoplasm where its two disulfide bonds are incapable of forming (Sone et al. 1997), and TraR, a transcriptional activator from Agrobacterium tumefaciens that is highly unstable in the E. coli cytoplasm in the absence of its cognate ligand (Zhu and Winans 2001). Expression of all target proteins known to be stable in the cytoplasm, namely TrxA, GST, green fluorescent protein (GFP), Top7 (Kuhlman et al. 2003), and human tumor suppressor protein p53 core domain (residues 94–312) (Friedler et al. 2003) resulted in localization to the periplasm and conferred Amp resistance to MC4100 (Fig. 3, lanes 1–5). On the contrary, those known to be highly unstable, namely PhoA, TraR, and the human testicular cancer antigen NY-ESO1 (Chen et al. 1997; Murphy et al. 2005) were virtually undetectable in the soluble cytoplasmic fraction and did not confer Amp resistance to MC4100 (Fig. 3, lanes 6–8). Though there was no visible periplasmic band for ssTorA-p53-Bla, it conferred significant Amp resistance to cells and the corresponding periplasmic Bla activity was threefold above ssTorA-PhoA-Bla negative controls, suggesting that the level of this fusion protein in the periplasmic fraction was below the threshold of immunodetection. Interestingly, the extremely stable de novo-designed Top7 protein, exhibiting an α/β protein structure not previously observed in nature (Kuhlman et al. 2003), conferred significant Amp resistance to cells.

Figure 3.

The Tat-specific genetic selection correctly reports the solubility of a broad spectrum of target proteins. (A) Growth of MC4100 cells on LB agar supplemented with 100 μg/mL Amp expressing GST (23 kDa), TrxA (14 kDa), Top7 (11 kDa), GFP (23 kDa), p53 (25 kDa), NY-ESO1 (14 kDa), TraR (27 kDa), or PhoA (49 kDa) in the target position of pTMB (molecular weights in kDa reflect the test protein alone). Each spot represents 5 μL of an equivalent number of overnight grown cells. (B) Relative growth rate of MC4100 cells as determined by 96-well plate liquid growth assays. All data were normalized to the growth rate of cells expressing ssTorA-GST-Bla (0.399 h−1). (C) Subcellular localization of each tripartite fusion expressed in MC4100. All samples were probed with anti-Bla serum. Cells expressing pTMB with no insert are shown in lane 1 for comparison. (D) Localization of cytoplasmic marker GroEL probed with anti-GroEL serum.

An unanswered question was whether these stably expressed target proteins were truly folded and, if so, whether their folding was completed in the cytoplasm prior to export. To address this issue we examined the subcellular fractions generated from wild-type cells expressing the ssTorA-GFP-Bla fusion. GFP is a heterologous protein known to fold into its native fluorescent conformation in the cytoplasm but is incapable of folding into an active conformation in the periplasm (Feilmeier et al. 2000). Thus, the presence of fluorescent GFP in the periplasm is a strong indicator of cytoplasmic folding prior to transport (Santini et al. 2001; Thomas et al. 2001; DeLisa et al. 2002). We observed that the GFP-Bla fusion protein in the periplasmic fraction of MC4100 cells was strongly fluorescent (>15-fold above the signal from the periplasmic fraction of B1LK0; data not shown). Since active periplasmic GFP can only arise from folding prior to transport (Santini et al. 2001; Thomas et al. 2001; DeLisa et al. 2002), we conclude that the kinetics of Tat transport allow complete folding prior to translocation.

Monitoring multimeric proteins

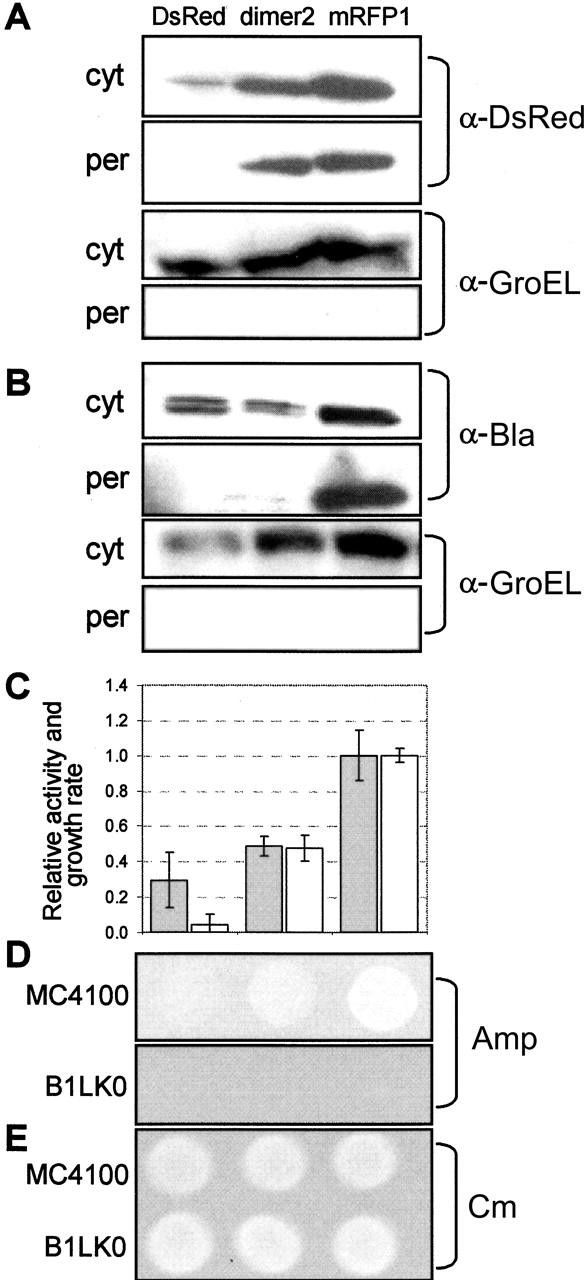

Based on the observation that the dimeric E. coli GST protein was transported to the periplasm (Fig. 3) and that the Tat system is known to translocate pre-assembled heterodimers (Rodrigue et al. 1999; DeLisa et al. 2003), we next explored the extent to which our reporter was able to process stable multimeric proteins. Specifically, we examined transport of Discosoma coral DsRed (version T1) and two mutants derived from DsRed, namely dimer2 and mRFP1 (Campbell et al. 2002). Whereas DsRed.T1 forms obligate tetramers which tend to aggregate, Tsien and coworkers evolved a useful monomeric variant (mRFP1) that does not aggregate in vivo. We reasoned that as the evolved proteins become smaller (tetramer, dimer, monomer) and more soluble they would be more efficiently processed by the Tat machinery. To test this notion, we constructed three ssTorA-DsRed chimeras and tracked their subcellular localization. The periplasmic yield of each fusion protein in MC4100 was consistent with its level of soluble expression in the cytoplasm (Fig. 4A). That is, mRFP accumulated at a high level in the periplasm; dimer2, at an intermediate level; and DsRed was undetectable in the periplasmic space. Importantly, the observed transport for mRFP and dimer2 was Tat-specific as neither of these fusion proteins localized in the periplasm of B1LK0 (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Monitoring the aggregation properties of DsRed and its variants. An equivalent number of cells were harvested 6 h after induction and fractionated into cytoplasmic (cyt) and periplasmic (per) fractions. (A) Subcellular distribution of DsRed.T1, dimer2, and mRFP1 expressed via the Tat pathway (ssTorA) and probed by anti-DsRed serum. Cells expressing ssTorA-DsRed.T1-Bla, ssTorA-dimer2-Bla, and ssTorA-mRFP1-Bla were assayed for subcellular distribution of the fusion protein (B) by probing with Bla anti-serum. GroEL was used as a fractionation marker by probing with GroEL anti-serum. (C) Relative periplasmic Bla activity as determined by the rate of nitrocefin hydrolysis (gray bars) and relative growth rate as determined by 96-well plate liquid growth assays (white bars). All data were normalized to the activity (0.152 abs units/sec) and the growth rate (0.390 h−1) of cells expressing ssTorA-mRFP1-Bla. Lastly, growth on solid medium by spot plating 5 μL of an equivalent number of cells on LB agar supplemented with 100 μg/mL Amp (D) or 25 μg/mL Cm (E).

Similar results were observed when the DsRed.T1, dimer2, and mRFP1 sequences were inserted into pTMB. That is, cells expressing ssTorA-DsRed.T1-Bla did not localize the fusion protein to the periplasm and were incapable of growth on Amp (Fig. 4B), consistent with our observation that ssTorA-DsRed.T1 alone is not transported via the Tat mechanism. On the contrary, cells expressing ssTorA-mRFP1-Bla showed significant periplasmic accumulation of the fusion and were resistant to Amp, in accord with the increased solubility of mRFP1 relative to DsRed.T1. There was a low but detectable level of ssTorA-dimer2-Bla in the periplasm. The reduced quantity of ssTorA-dimer2-Bla relative to the unfused ssTorA-dimer2 (Fig. 4A) is likely due to its increased molecular mass as a result of the fusion to Bla. Nonetheless, cells expressing this fusion displayed intermediate levels of periplasmic Bla activity and growth on Amp which were significantly above the levels seen for cells expressing ssTorA-DsRed.T1-Bla and indicated that this engineered dimer could be detected by our assay (Fig. 4B,C). Finally, no growth was observed for B1LK0 expressing any of the ssTorA-DsRed-Bla fusions indicating that transport was Tat-specific. These data suggest that monomeric or even dimeric proteins are preferentially transported by the Tat pathway, as opposed to larger multimers.

Monitoring protein folding related to human disease

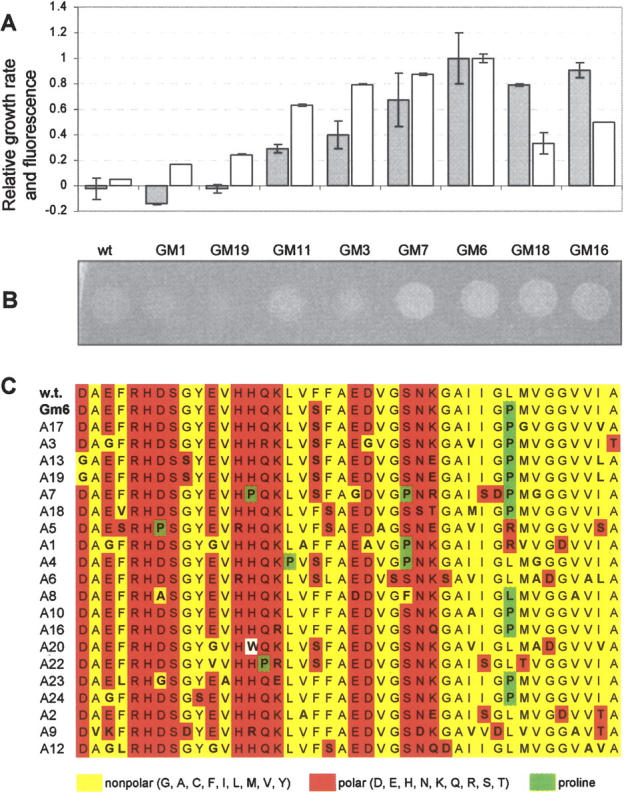

To test the extent to which the assay was effective in reporting solubility in the context of protein aggregation in human disease, the Alzheimer’s amyloid β-peptide (Aβ42), which is the primary component of amyloid fibrils found in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients (Selkoe 2001), was analyzed using our reporter. The relative growth rates in Amp of MC4100 expressing wild-type Aβ42 and a collection of Aβ42 mutants were measured. In agreement with previous data (Wigley et al. 2001), Aβ42(wt) did not confer growth to MC4100 (Fig. 5A,B). We next screened a panel of solubility-enhanced Aβ42 variants, which were previously isolated using a directed evolution strategy in combination with a GFP-based folding assay (Wurth et al. 2002). In all but two instances, our growth rate results (Fig. 5A, gray bars) were in agreement with solubility data reported previously for these sequences by Hecht and coworkers (Wurth et al. 2002) using Aβ42-GFP fusions (Fig. 5A, white bars). Interestingly, for GM16 and GM18, which each contained the critical L34P mutation (Fig. 5A), there was notable disagreement between the two assays, which could indicate a folding reporter bias imparted by a C-terminal GFP fusion versus our Tat quality control-based assay. Overall, we found that amino acid substitutions that decrease the propensity of Aβ42 to aggregate rendered the fusion protein competent for transport and conferred an Amp-resistant phenotype to cells (Fig. 5A,B).

Figure 5.

Analysis of amyloid-β peptide (Aβ42) and its derivatives. Growth of MC4100 cells as determined by (A) 96-well plate liquid growth assays (gray bars) and (B) spot plating 5 μL of an equivalent number of cells on LB agar supplemented with 100 μg/mL Amp for the following target sequences (from left to right): (wt) wild type Aβ42, (GM1) Aβ42 I32S, (GM19) Aβ42 F19S, (GM11) Aβ42 H6Q/V12A/ V24A/I32M/V36G, (GM3) Aβ42 V12E/V18E/M35T/I41N, (GM7) Aβ42 V12A/I32T/L34P, (GM6) Aβ42 F19S/L34P, (GM18) Aβ42 L34P, and (GM16) Aβ42 F4I/S8P/V24A/L34P. All data were normalized to the growth rate of cells expressing ssTorA-Aβ42(GM6)-Bla (0.240 h−1). Relative fluorescence of Aβ42-GFP fusions (white bars) was calculated by normalizing cell fluorescence for each fusion to that emitted from Aβ42 F19S/L34P (GM6). (C) The sequence of wt, GM6, and the entire collection of Aβ42 sequences isolated using the Tat folding assay. This collection, including clone A17, was isolated from a high-rate mutagenesis of the Aβ42 peptide, followed by selection on Amp-containing growth medium.

Selection of solubility-enhanced variants from large combinatorial libraries

To demonstrate the efficacy of our selection assay, we first performed selection experiments in which cells expressing a well-folded model protein, GFP, and a poorly folded model protein, PhoA, were mixed and subsequently plated on selective media. When GFP:PhoA-expressing cells were mixed at a ratio of 1:106, we only recovered GFP expressing cells on Amp plates at a ratio of 1 GFP expressing (and fluorescent) colony for every 0.9 ± 0.1 × 106 cells that were plated, (determined by plating mixture on Cm plates; data not shown). Encouraged by these results, we performed a second selection experiment by subjecting the Aβ42 sequence to high-rate mutagenesis (determined to be 15% error at the amino acid level in the naïve library) followed by selection of Amp-resistant clones representing solubility-enhanced variants of the Aβ42 peptide. From a cell library of ~1.5 × 106 members, we selected 2.8 × 103 cells on Amp-containing plates. Plasmids from 20 randomly chosen positive clones were isolated and sequenced. Notably, in residues F19 and L34 alone there were a total of 22 mutations in our collection of 20 clones. These sites are identical to those found in the stable variant GM6 (F19S, L34P) and in previous mutagenesis studies of Aβ42 (Wood et al. 1995; Wurth et al. 2002). In fact, 17 of the 20 clones carried mutations in one or both of these two residues. It is noteworthy that only two of 17 clones from the naïve library selected at random contained a mutation in either F19 or L34, suggesting that the 17 positive clones were indeed selected and not artificially biased in the naïve library. Serendipitously, in just these 20 clones we isolated a variant, A17 (F19S, L34P, M35G, I41V), which differed by only two amino acids from clone GM6 (F19S, L34P) isolated by Hecht and colleagues (Wurth et al. 2002; Fig. 5C). Sequencing results revealed that of 124 total mutations present in the 20 positive clones, 15 came from the central hydrophobic cluster (residues 17–21) and 34 came from the hydrophobic cluster located at residues 30–36. These regions represent only 29% of the primary structure but account for 40% of the total mutations and 47% of the nonconservative mutations uncovered by our selection. Collectively, these results support the use of our genetic selection for the isolation of solubility-enhancing mutations from a highly mutated library.

Discussion

The bacterial Tat pathway is known for its ability to transport folded proteins from their site of synthesis in the cytoplasm to the periplasmic space. This feat is accomplished by an inner membrane pore complex minimally comprised of the membrane proteins TatA/E, TatB and TatC (Berks etal. 2000). The Tat(A/E)BC pore exhibits a variable diameter as large as ~50–70 Å (Sargent et al. 2001), which helps to explain how the Tat system can accommodate a wide range of folded proteins with molecular weights as large as 120kDa (Berks et al. 2000; Sargent et al. 2001; Gohlke et al. 2005). In nature, proteins are thought to use the Tat rather than the traditional general secretory (Sec) pathway if they require cofactor binding (Santini et al. 1998) or subunit assembly (Rodrigue et al. 1999), or simply fold too rapidly to be Sec export competent (Berks 1996). Earlier genetic studies (Sanders et al. 2001; DeLisa et al. 2003), along with data presented here, demonstrate a clear ability of the Tat pathway to selectively translocate proteins that are correctly folded and soluble and suggest that a folding quality control mechanism governs this process. While a number of possible mechanisms have been proposed (Berks et al. 2000; Fisher and DeLisa 2004), to date there is little to no evidence detailing how this process operates in bacteria. Sargent and coworkers (Jack etal. 2004) have recently demonstrated that, for endogenous cofactor-containing Tat substrates, proofreading is performed by a cytoplasmic chaperone. However, the extent to which this mechanism relates to the overall quality control of the Tat pathway remains an open question. In addition, bacteria have other elegant mechanisms of quality control, such as protease degradation and chaperonin activity, that likely work in concert with the Tat quality control mechanism to provide an authentic in vivo quality control that constitutes the underlying framework for our reporter assay. We showed that a facile genetic selection for protein solubility that capitalizes on this quality control feature was possible by fusing an N-terminal Tat signal peptide and a C-terminal Bla reporter protein to a desired test protein. The practical utility of this assay is its ability to survey the folding status of the test protein. Indeed, the assay reported the folding behavior of 26 proteins of prokaryotic and eukaryotic origin, a feat that could be accomplished in <8 h by monitoring bacterial growth in a 96-well plate format. Assays were held to <8 h because over longer times, ΔtatC cells occasionally exhibited a low level of Amp resistance in liquid cultures, particularly for the highly-expressed TrxA fusion. This could arise from release of soluble Bla into the medium following cell lysis or from a proteolytic cleavage event between the two protein domains creating an accumulation of mature Bla that can be translocated into the periplasmic space, albeit with a low efficiency (Bowden et al. 1992). This reinforces the fact that when performing Tat-based assays, positive results are only relevant when tested against a ΔtatC control.

One shortcoming of many existing in vivo folding assays (Maxwell et al. 1999; Waldo et al. 1999; Wigley et al. 2001; Cabantous et al. 2005) is the possibility that the fusions might incorrectly bias the folding behavior of the test protein. Although stable association between Tat signal peptides and the protein to which they are fused is disfavored (Nurizzo et al. 2001; Kipping et al. 2003), we cannot rule out the possibility that Tat signals may influence the folding of target proteins or shield them from degradation. It is also possible that C-terminal β-lactamase may impact folding of the target protein in some unforeseen way. However, any effect these fusions may have was not manifested in any of the 26 proteins tested here, as correct folding behavior of virtually every target protein was reported. We suspect that the success of our assay arises from the fact that an authentic quality control mechanism is used to screen folding as opposed to reliance upon cotranslational misfolding of the reporter. It is noteworthy that our reporter assay compares favorably to previous in vivo assays based on cotranslational folding (e.g., GFP fusions [Waldo et al. 1999; Wurth et al. 2002, see Fig. 6]). One constraint on our assay is that transport might be inaccessible to fusions whose size exceeds the upper limit handled by the Tat pore (~120 kDa is the largest known protein reported to transit the Tat pathway). Nonetheless, fusions as large as 70 kDa (ssTorA-MBP-Bla) were efficiently translocated. If necessary, larger target proteins or protein dimers might be screened by employing a fragment complementation approach (Wigley et al. 2001; Cabantous et al. 2005) to reduce the size of the Bla reporter.

A clear advantage of our assay is the easy potential to perform a phenotypic selection. That is, this genetic system could be used to screen combinatorial libraries for genes expressing proteins with enhanced folding properties and decreased tendencies toward aggregation, i.e., “supersoluble” proteins (Lansbury 2001). This selection could also be employed in a wide array of bacterial strains to isolate genetic backgrounds that support efficient expression and folding of target proteins. Furthermore, since Tat-targeted proteins have a significant residence time in the cytoplasm prior to transport, this assay is amenable to studying slow misfolding or aggregation events that may escape detection by cotranslational folding schemes. Finally, since all correctly folded proteins in our selection localize in the periplasm, we envision that two-dimensional genetic assays can be performed for identifying proteins that exhibit not only robust folding properties but also activities that can easily be probed by substrates permeable to the outer membrane. In essence, isolating proteins based on structure and function.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and plasmids

Wild-type E. coli strain MC4100 and a ΔtatC derivative of MC4100, strain B1LK0 (Bogsch et al. 1998), were used for all folding assay experiments. Strain HS3018 (Shuman 1982) was used for expression of MBP. All plasmids generated in this study were derivatives of pTrc99A (Amersham Pharmacia) unless otherwise noted. For all folding reporter plasmids, pTrc99A was modified as follows: The β-lactamase (Bla) gene was replaced with a Cmr cassette to generate pTrc99A-Cm (kindly provided by M. Zhao and G. Georgiou), followed by sequential insertion of the DNA encoding the ssTorA signal peptide (DeLisa et al. 2002) and the β-lactamase protein. The resulting plasmid, hereafter pTMB, contained three additional restriction sites (XbaI, SalI, and BamHI) immediately after the ssTorA sequence to allow facile insertion of target DNA sequences between ssTorA and Bla (Fig. 1). For all plate-based selection experiments, the vector pSALect was used since conditions for recovering ampicillin (Amp) resistant colonies has already been documented (Lutz et al. 2002). The Aβ42 target sequence was cloned into pSALect between the DNA encoding ssTorA and Bla. Combinatorial libraries of Aβ42 were synthesized by mutagenesis of the Aβ42 gene sequence using the nucleotide analog method of Zaccolo et al. (1996) and the resulting gene library was inserted into pSALect. All plasmids constructed in this study were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Cell growth assays

Cells carrying a folding reporter plasmid were grown overnight in LB medium containing chloramphenicol (Cm; 25 μg/mL). Screening of cells on solid plates was performed by spotting 5 μL of 10×-diluted overnight cells directly onto LB agar plates supplemented with Amp (100 μg/mL) or Cm (25 μg/mL) and growing overnight at room temperature. Library selections were performed by electroporating plasmid DNA libraries into E. coli cells followed by direct plating on LB agar plates supplemented with 100 μg/mL Amp according to Lutz et al. (2002). Screening of cells in liquid culture was performed by diluting overnight cells 100-fold into fresh LB plus 100 μg/mL Amp in 96-well plates. Cells were grown aerobically at 30°C for ~6 h and growth rates were calculated as from the absorbance change at 600 nm using a plate reader. All growth rate data is the average of three cultures grown in parallel. Error is reported as plus or minus the standard deviation of these data.

Protein analysis

Subcellular fractionation was performed using the ice-cold osmotic shock procedure (Sargent et al. 1998; DeLisa et al. 2003). Western blotting of these fractions was performed as previously described (DeLisa et al. 2003). The quality of all fractionations was determined by immunodetection of the cytoplasmic GroEL protein (DeLisa et al. 2003). Finally, osmotic shockate (i.e., periplasmic fractions) was assayed for β-lactamase activity based on nitrocefin hydrolysis in 96-well format as described (Galarneau et al. 2002).

Acknowledgments

We thank David Baker, Carl Batt, Jean-Michel Betton, Alan Fersht, Michael Hecht, Philip Thomas, Roger Tsien, Steve Winans, and Stefan Lutz for plasmid DNA used in this study, and Tracy Palmer and Howard Shuman for strains B1LK0 and HS3018, respectively. We thank Michael Hecht and Philip Bronstein for helpful discussions of the manuscript. Funding was provided by an NSF CAREER Award (BES no. 0449080) and a NYSTAR James D. Watson Award (both to M.P.D).

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.051902606.

References

- Baneyx, F. and Mujacic, M. 2004. Recombinant protein folding and misfolding in Escherichia coli. Nat. Biotechnol. 22: 1399–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berks, B.C. 1996. A common export pathway for proteins binding complex redox cofactors? Mol. Microbiol. 22: 393–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berks, B.C., Sargent, F., and Palmer, T. 2000. The Tat protein export pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 35: 260–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betton, J. and Hofnung, M. 1996. Folding of a mutant maltose-binding protein of Escherichia coli which forms inclusion bodies. J. Biol. Chem. 271: 8046–8052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogsch, E.G., Sargent, F., Stanley, N.R., Berks, B.C., Robinson, C., and Palmer, T. 1998. An essential component of a novel bacterial protein export system with homologues in plastids and mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 18003–18006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden, G.A., Baneyx, F., and Georgiou, G. 1992. Abnormal fractionation of β-lactamase in Escherichia coli: Evidence for an interaction with the inner membrane in the absence of a leader peptide. J. Bacteriol. 174: 3407–3410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabantous, S., Terwilliger, T.C., and Waldo, G.S. 2005. Protein tagging and detection with engineered self-assembling fragments of green fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 23: 102–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, R.E., Tour, O., Palmer, A.E., Steinbach, P.A., Baird, G.S., Zacharias, D.A., and Tsien, R.Y. 2002. A monomeric red fluorescent protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99: 7877–7882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.T., Scanlan, M.J., Sahin, U., Tureci, O., Gure, A.O., Tsang, S., Williamson, B., Stockert, E., Pfreundschuh, M., and Old, L.J. 1997. A testicular antigen aberrantly expressed in human cancers detected by autologous antibody screening. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 94: 1914–1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLisa, M.P., Samuelson, P., Palmer, T., and Georgiou, G. 2002. Genetic analysis of the twin arginine translocator secretion pathway in bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 29825–29831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLisa, M.P., Tullman, D., and Georgiou, G. 2003. Folding quality control in the export of proteins by the bacterial twin-arginine translocation pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100: 6115–6120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, R.J. and Minton, A.P. 2003. Cell biology: Join the crowd. Nature 425: 27–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feilmeier, B.J., Iseminger, G., Schroeder, D., Webber, H., and Phillips, G.J. 2000. Green fluorescent protein functions as a reporter for protein localization in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 182: 4068–4076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, A.C. and DeLisa, M.P. 2004. A little help from my friends: Quality control of presecretory proteins in bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 186: 7467–7473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedler, A., Veprintsev, D.B., Hansson, L.O., and Fersht, A.R. 2003. Kinetic instability of p53 core domain mutants: Implications for rescue by small molecules. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 24108–24112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galarneau, A., Primeau, M., Trudeau, L.E., and Michnick, S.W. 2002. β-lactamase protein fragment complementation assays as in vivo and in vitro sensors of protein protein interactions. Nat. Biotechnol. 20: 619–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiou, G. and Valax, P. 1996. Expression of correctly folded proteins in Escherichia coli. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 7: 190–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerth, M.L., Patrick, W.M., and Lutz, S. 2004. A second-generation system for unbiased reading frame selection. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 17: 595–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohlke, U., Pullan, L., McDevitt, C.A., Porcelli, I., de Leeuw, E., Palmer, T., Saibil, H.R., and Berks, B.C. 2005. The TatA component of the twin-arginine protein transport system forms channel complexes of variable diameter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 102: 10482–10486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack, R.L., Buchanan, G., Dubini, A., Hatzixanthis, K., Palmer, T., and Sargent, F. 2004. Coordinating assembly and export of complex bacterial proteins. EMBO J. 23: 3962–3972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipping, M., Lilie, H., Lindenstrauss, U., Andreesen, J.R., Griesinger, C., Carlomagno, T., and Bruser, T. 2003. Structural studies on a twin-arginine signal sequence. FEBS Lett. 550: 18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlman, B., Dantas, G., Ireton, G.C., Varani, G., Stoddard, B.L., and Baker, D. 2003. Design of a novel globular protein fold with atomic-level accuracy. Science 302: 1364–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansbury Jr., P.T. 2001. Following nature’s anti-amyloid strategy. Nat. Biotechnol. 19: 112–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesley, S.A., Graziano, J., Cho, C.Y., Knuth, M.W., and Klock, H.E. 2002. Gene expression response to misfolded protein as a screen for soluble recombinant protein. Protein Eng. 15: 153–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorimer, G.H. 1996. A quantitative assessment of the role of the chaperonin proteins in protein folding in vivo. FASEB J. 10: 5–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, S., Fast, W., and Benkovic, S.J. 2002. A universal, vector-based system for nucleic acid reading-frame selection. Protein Eng. 15: 1025–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makrides, S.C. 1996. Strategies for achieving high-level expression of genes in Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Rev. 60: 512–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, K.L., Mittermaier, A.K., Forman-Kay, J.D., and Davidson, A.R. 1999. A simple in vivo assay for increased protein solubility. Protein Sci. 8: 1908–1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, R., Green, S., Ritter, G., Cohen, L., Ryan, D., Woods, W., Rubira, M., Cebon, J., Davis, I.D., Sjolander, A., et al. 2005. Recombinant NY-ESO-1 cancer antigen: Production and purification under cGMP conditions. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 35: 119–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurizzo, D., Halbig, D., Sprenger, G.A., and Baker, E.N. 2001. Crystal structures of the precursor form of glucose-fructose oxidoreductase from Zymomonas mobilis and its complexes with bound ligands. Biochemistry 40: 13857–13867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philibert, P. and Martineau, P. 2004. Directed evolution of single-chain Fv for cytoplasmic expression using the β-galactosidase complementation assay results in proteins highly susceptible to protease degradation and aggregation. Microb. Cell. Fact. 3: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radford, S.E. and Dobson, C.M. 1999. From computer simulations to human disease: Emerging themes in protein folding. Cell 97: 291–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigue, A., Chanal, A., Beck, K., Muller, M., and Wu, L.F. 1999. Cotranslocation of a periplasmic enzyme complex by a hitchhiker mechanism through the bacterial tat pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 13223–13228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roodveldt, C., Aharoni, A., and Tawfik, D.S. 2005. Directed evolution of proteins for heterologous expression and solubility. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 15: 50–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross, C.A. and Poirier, M.A. 2004. Protein aggregation and neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Med. 10 (Suppl.): S10–S17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, C., Wethkamp, N., and Lill, H. 2001. Transport of cytochrome c derivatives by the bacterial Tat protein translocation system. Mol. Microbiol. 41: 241–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santini, C.L., Ize, B., Chanal, A., Muller, M., Giordano, G., and Wu, L.F. 1998. A novel Sec-independent periplasmic protein translocation pathway in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 17: 101–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santini, C.L., Bernadac, A., Zhang, M., Chanal, A., Ize, B., Blanco, C., and Wu, L.F. 2001. Translocation of jellyfish green fluorescent protein via the Tat system of Escherichia coli and change of its periplasmic localization in response to osmotic up-shock. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 8159–8164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent, F., Bogsch, E.G., Stanley, N.R., Wexler, M., Robinson, C., Berks, B.C., and Palmer, T. 1998. Overlapping functions of components of a bacterial Sec-independent protein export pathway. EMBO J. 17: 3640–3650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent, F., Gohlke, U., De Leeuw, E., Stanley, N.R., Palmer, T., Saibil, H.R., and Berks, B.C. 2001. Purified components of the Escherichia coli Tat protein transport system form a double-layered ring structure. Eur. J. Biochem. 268: 3361–3367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe, D.J. 2001. Alzheimer’s disease: Genes, proteins, and therapy. Physiol. Rev. 81: 741–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settles, A.M., Yonetani, A., Baron, A., Bush, D.R., Cline, K., and Martienssen, R. 1997. Sec-independent protein translocation by the maize Hcf106 protein. Science 278: 1467–1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuman, H.A. 1982. Active transport of maltose in Escherichia coli K12. Role of the periplasmic maltose-binding protein and evidence for a substrate recognition site in the cytoplasmic membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 257: 5455–5461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sone, M., Kishigami, S., Yoshihisa, T., and Ito, K. 1997. Roles of disulfide bonds in bacterial alkaline phosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 6174–6178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J.D., Daniel, R.A., Errington, J., and Robinson, C. 2001. Export of active green fluorescent protein to the periplasm by the twin-arginine translocase (Tat) pathway in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 39: 47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsumoto, K., Umetsu, M., Kumagai, I., Ejima, D., and Arakawa, T. 2003. Solubilization of active green fluorescent protein from insoluble particles by guanidine and arginine. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 312: 1383–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldo, G.S., Standish, B.M., Berendzen, J., and Terwilliger, T.C. 1999. Rapid protein-folding assay using green fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 17: 691–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall, J.G. and Pluckthun, A. 1995. Effects of overexpressing folding modulators on the in vivo folding of heterologous proteins in Escherichia coli. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 6: 507–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, J.H., Bilous, P.T., Shaw, G.M., Lubitz, S.P., Frost, L., Thomas, G.H., Cole, J.A., and Turner, R.J. 1998. A novel and ubiquitous system for membrane targeting and secretion of cofactor-containing proteins. Cell 93: 93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigley, W.C., Stidham, R.D., Smith, N.M., Hunt, J.F., and Thomas, P.J. 2001. Protein solubility and folding monitored in vivo by structural complementation of a genetic marker protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 19: 131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, A.D., Sega, M., Chen, M., Kheterpal, I., Geva, M., Berthelier, V., Kaleta, D.T., Cook, K.D., and Wetzel, R. 2005. Structural properties of Aβ protofibrils stabilized by a small molecule. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 102: 7115–7120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood, S.J., Wetzel, R., Martin, J.D., and Hurle, M.R. 1995. Prolines and amyloidogenicity in fragments of the Alzheimer’s peptide β/A4. Biochemistry 34: 724–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurth, C., Guimard, N.K., and Hecht, M.H. 2002. Mutations that reduce aggregation of the Alzheimer’s Aβ42 peptide: An unbiased search for the sequence determinants of Aβ amyloidogenesis. J. Mol. Biol. 319: 1279–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaccolo, M., Williams, D.M., Brown, D.M., and Gherardi, E. 1996. An approach to random mutagenesis of DNA using mixtures of triphosphate derivatives of nucleoside analogues. J. Mol. Biol. 255: 589–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J. and Winans, S.C. 2001. The quorum-sensing transcriptional regulator TraR requires its cognate signaling ligand for protein folding, protease resistance, and dimerization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98: 1507–1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]