Abstract

The matrix (MA) protein of the simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIVs) is encoded by the amino-terminal region of the Gag precursor and is the component of the viral capsid that lines the inner surface of the virus envelope. Previously, we identified domains in the SIV MA that are involved in the transport of Gag to the plasma membrane and in particle assembly. In this study, we characterized the role in the SIV life cycle of highly conserved residues within the SIV MA region spanning the two N-terminal α-helices H1 and H2. Our analyses identified two classes of MA mutants: (i) viruses encoding amino acid substitutions within α-helices H1 or H2 that were defective in envelope (Env) glycoprotein incorporation and exhibited impaired infectivity and (ii) viruses harboring mutations in the β-turn connecting helices H1 and H2 that were more infectious than the wild-type virus and displayed an enhanced ability to incorporate the Env glycoprotein. Remarkably, among the latter group of MA mutants, the R22L/G24L double amino acid substitution increased virus infectivity eightfold relative to the wild-type virus in single-cycle infectivity assays, an effect that correlated with a similar increase in Env incorporation. Furthermore, the R22L/G24L MA mutation partially or fully complemented single-point MA mutations that severely impair or block Env incorporation and virus infectivity. Our finding that the incorporation of the Env glycoprotein into virions can be upregulated by specific mutations within the SIV MA amino terminus strongly supports the notion that the SIV MA domain mediates Gag-Env association during particle formation.

Simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIVs), as well as the closely related human immunodeficiency viruses (HIVs), assemble their capsids from the viral Gag protein at the plasma membrane of the infected cells (for reviews, see references 10 and 22). The Gag protein of HIV type 1 (HIV-1) and SIV is synthesized as a polyprotein precursor which, subsequent to virus budding, is proteolytically processed by the viral protease into the mature proteins: matrix (MA), capsid (CA), nucleocapsid, and p6 proteins, as well as the spacer peptides p2 and p1 (21). In the mature virion, the MA protein forms the outer shell that is directly associated with the lipid envelope (15). During virus assembly, the MA domain provides the primary determinants for the membrane targeting and association of the Gag precursor with the plasma membrane. It is well established that the cotranslational addition of myristic acid to the N-terminal glycine residue of MA is necessary for the proper targeting of the Gag precursor to the plasma membrane and virus particle formation (1, 5, 13, 20). Furthermore, the stable plasma membrane association of the HIV-1 and SIV Gag precursor is dependent on the presence in the MA protein of a membrane-binding competent domain composed of the N-myristate group, its neighboring hydrophobic residues, Val7 and Leu8, and a highly basic sequence located between MA residues 26 and 32 (17, 18, 30, 32, 38, 39). In addition to its role in Gag membrane binding, the MA protein appears to be involved in the incorporation of the viral envelope (Env) glycoprotein into virions during assembly. The Env glycoprotein spikes are present on the virion surface as trimeric complexes of a heterodimer formed by the surface glycoprotein (SU; gp120) and the transmembrane (TM) glycoprotein (gp41). It has been reported that small missense or deletion mutations within the N-terminal 100 amino acids (7, 36), and certain amino acid substitutions in the N-terminal 35 residues (12, 31) of the HIV-1 MA protein block Env incorporation into virions. Likewise, certain truncations or in-frame deletions in the cytoplasmic domain of the HIV-1 (8, 12, 29, 37) and SIV (2, 27) TM glycoprotein gp41 inhibit Env incorporation into virions. These results, together with the demonstration for HIV-1 and SIV that the Env incorporation block imposed by mutations in the MA domain can be reversed by expression of an Env protein with a short cytoplasmic tail (11, 12, 19, 26), support the notion that an interaction between the TM cytoplasmic tail and the MA domain mediates the process of Env incorporation into virions.

We have previously performed site-directed mutagenesis studies of the SIV MA in order to map functional domains within this protein and assess its role in SIV morphogenesis (16-19). However, the molecular determinants in the SIV MA that are necessary for Env packaging into virions remained to be fully characterized. Since a major part of our structure-function analyses of the SIV MA have focused on the C-terminal two thirds of the molecule, in the present study we characterized the role that the MA region spanning the two N-terminal α-helices H1 and H2 plays in the SIV life cycle. We show here that mutations within this SIV MA region confer a differential ability to the Gag polyprotein to associate with the Env glycoprotein by modulating, either negatively or positively, the levels at which Env is incorporated into virions. Of note, the double substitution of leucine for the SIV MA residues Arg22 and Gly24 resulted in a dramatic enhancement of Env incorporation into virions and virus infectivity. Moreover, this mutation could even reverse the defects in Env incorporation and infectivity caused by single amino acid substitutions in the SIV MA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines. 293T and MAGI-CCR5 (HeLa-CD4-CCR5/LTR-β-gal) cells were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco). MAGI-CCR5 cells were additionally maintained in medium containing 0.2 mg of G418 (Geneticin) per ml, 0.1 mg of hygromycin B per ml, and 1 μg of puromycin per ml. The MAGI-CCR5 cell line was obtained through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program and was originally contributed by J. Overbaugh (3). CEMx174 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics.

Construction of mutated proviral DNA constructs.

SIVSMM PBj1.9, the parental SIV proviral clone used, has been described previously (6). Mutagenesis of the MA-coding region was performed on a SalI-DraIII fragment (PBj1.9 nucleotides 1 to 1214) by using the asymmetric PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis method that we have previously described (2, 18). The SalI-DraIII fragments carrying the desired mutations were substituted for the wild-type counterpart in the parental DNA construct. To generate MA mutants carrying the CD44 mutation in the env gene, the PshAI-NotI fragment (nucleotides 8170 to 9996) in each molecular clone was replaced by the corresponding fragment from PBj-CD44 (27) which harbors a premature stop codon mutation at nucleotide positions 8673 to 8675 in place of codon 770 of the env gene. Introduction of the double amino acid substitution R22L/G24L into the SIV molecular clones bearing mutations at MA residues 31 (L31E) or 34 (I34T) was performed by site-directed mutagenesis of the 1.2-kb SalI-DraIII fragment from either the L31E or I34T MA mutant. The presence of all of the mutations was confirmed by direct sequencing.

Transfections.

For the generation of virus stocks, 293T cells (60-mm-diameter petri dishes) were transfected with 10 μg of wild-type or mutant SIV proviral DNAs by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Virus stocks pseudotyped with the vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein (VSV-G) were obtained by cotransfecting 293T cells with each proviral DNA and the pCMV-VSVG plasmid (kindly provided by O. Podhajcer, Instituto Leloir, Buenos Aires, Argentina). At 48 h posttransfection, cell culture supernatants were harvested, filtered (0.45-μm pore size), normalized for reverse transcriptase (RT) activity, and used in the infections as described below.

Viral protein analysis and Western blotting.

SIV proviral DNA clones were transfected into 293T cells as described above. At 48 h posttransfection, cells were washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed at 4°C in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 10 μg of aprotinin per ml). The culture supernatants from the transfected cells were filtered through 0.45-μm-pore-size syringe filters, and virions were pelleted from the clarified supernatants by ultracentrifugation (100,000 × g, 90 min, 4°C) through a 20% (wt/vol) sucrose cushion and then resuspended in Laemmli buffer (25). Cell- and virion-associated proteins were resolved on a sodium dodecyl sulfate-10% polyacrylamide gel, blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes, and analyzed by Western blotting coupled with an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) assay (Amersham Biosciences), as previously described (2, 27). For the quantitative analysis of virion-associated proteins, Western blots were developed with the ECL Plus reagent (Amersham Biosciences), and the resulting chemifluorescent signal was scanned with the Storm 840 Imager (Amersham Biosciences) and analyzed with ImageQuant 5.1 software (Molecular Dynamics). Monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) used to detect SIV gp41 (MAb KK41) (23) and SIV Gag-related proteins (MAb KK60) were obtained from J. Stott and K. Kent through the MRC AIDS Directed Programme. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antimouse immunoglobulin (Amersham Biosciences) was used as secondary antibody.

RT assays.

Quantitation of virion-associated RT in cell-free culture supernatants from transfected or infected cells was performed by using a commercial colorimetric RT assay (Roche Diagnostics). Briefly, Triton X-100-lysed samples were mixed with incubation buffer containing digoxigenin-labeled nucleotides and a poly(rA)oligo(dT)15 template-primer hybrid and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Newly synthesized DNA was detected by a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated sheep immunoglobulin G fraction specific for digoxigenin and ABTS [2,2′azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazolinesulfonic acid)] substrate. The resulting colored reaction signal was assessed on a microtiter plate (ELISA) reader at 405 nm (reference wavelength of 490 nm). The absorbance of the samples was then correlated to the calibration curve obtained with the recombinant HIV-1 RT enzyme provided in the kit. All assays were performed in duplicate and repeated a minimum of two times.

Single-cycle infectivity assays.

Virus stocks obtained by transfection of 293T cells were normalized for RT activity and used to infect in duplicate 4 × 104 MAGI-CCR5 cells in 24-well dishes as previously described (24, 27). At 2 days postinfection, cells were fixed with PBS containing 1% formaldehyde and 0.2% glutaraldehyde at room temperature for 5 min and then scored for blue foci formation after being stained with X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside). Virus entry was quantitated as the total number of blue cells per well by first counting the number of blue cells in at least 20 nonoverlapping fields in each of the two wells. The average number of blue cells per field was multiplied by the total number of fields per well, and the result was referred to the number of blue cells obtained with wild-type SIVSMMPBj 1.9.

Virus replication in CEMx174 cells.

Proviral DNA constructs were transfected into 293T cells for virus production. Supernatants were filtered and assayed for RT activity at 48 h posttransfection. For the analysis of spreading infections, CEMx174 cells were infected with volume-adjusted supernatants containing equivalent RT activity and incubated for 2 to 4 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. Infected cells were then washed twice with PBS to remove residual virus and incubated with fresh medium. Cell cultures were split at a 1:2 ratio every 2 days with fresh medium, and aliquots of culture supernatants were frozen at −80°C for RT determination at the conclusion of the experiment.

RESULTS

Mutagenesis of the SIV MA region spanning the N-terminal α-helices H1 and H2.

We have previously shown that the N-terminal region of the SIV MA bears domains that mediate the proper targeting and association of the Gag precursor with the plasma membrane (17, 18). To further examine the role of this MA region in virus morphogenesis and infectivity, we introduced a number of single, double, or triple amino acid substitutions within the SIV MA region spanning the N-terminal α-helix H1, the stretch of amino acids connecting helices H1 and H2, and the first four residues of α-helix H2 (Fig. 1). According to the SIV MA crystal structure (33), the region targeted for mutagenesis lies on the side of the MA trimers that has been proposed to face the lipid bilayer and may therefore be proximal to the Env cytoplasmic domain within the virion. This prompted us to speculate that, apart from the well-characterized role of the SIV MA N terminus in plasma membrane binding, the domain spanning α-helices H1 and H2 may exhibit molecular determinants that are involved in the incorporation of the Env glycoprotein into virions. To test this hypothesis, we introduced the MA mutations into the infectious proviral clone SIVSMMPBj1.9 and analyzed the phenotype of the resulting mutant viruses.

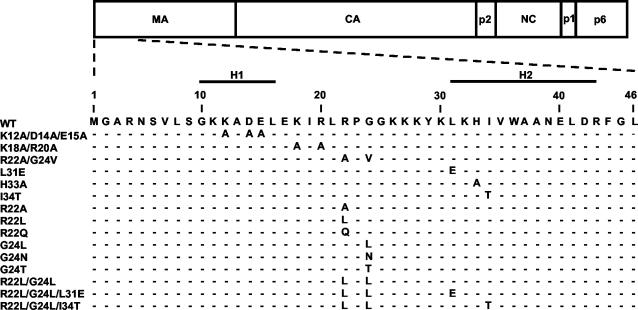

FIG. 1.

Mutagenesis of the N-terminal domain of the SIV MA protein. At the top of the figure, the organization of the SIV Gag precursor is represented as open boxes. The amino acid sequence of the SIVSMMPBj1.9 MA is shown with amino acid positions indicated above the sequence. The single, double, and triple amino acid substitutions that were introduced into the SIV MA region spanning the N-terminal α-helices H1 and H2 are shown, with the name of the mutation listed below wild-type (wt) PBj1.9. Dashes denote amino acid sequence identity with wtPBj1.9 MA.

Effect of the SIV MA mutations on Env incorporation and virus infectivity.

In a first set of experiments, we analyzed the phenotype of MA mutants encoding amino acid substitutions in either α-helix H1 (mutation K12A/D14A/E15A), α-helix H2 (mutations L31E, H33A, and I34T), or the residues connecting both α-helices (mutations K18A/R20A and R22A/G24V) (Fig. 1). 293T cells were transfected in parallel with wild-type PBj1.9 or the mutant proviral DNAs, and both the cell and virion lysates were assayed for the presence of the SIV TM and p27 CA proteins by Western blotting as described under Materials and Methods. The degree of Env incorporation into virions was evaluated by assessing the levels of virion-associated TM instead of the SIV gp120 SU subunit, because the latter can be spontaneously shed from the surface of the transfected cells and may therefore contaminate the virion fraction. As shown in Fig. 2A, the results indicated that all of the MA mutants were assembly competent, as evidenced by the detection of wild-type levels of SIV CA in purified MA mutant virions. When we analyzed the effect of the MA mutations on Env packaging into virions, we found that the K18A/R20A and R22A/G24V MA mutants incorporated Env with an efficiency similar to or, in the case of the R22A/G24V mutant, greater than wild-type PBj1.9 (Fig. 2A). In contrast, the K12A/D14A/E15A, L31E, H33A, and I34T MA mutations caused a drastic defect in Env incorporation compared to wild-type virions (Fig. 2A).

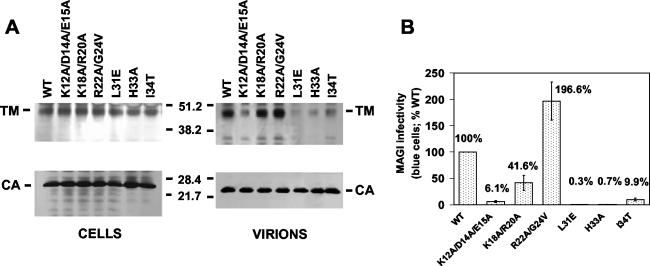

FIG. 2.

Effect of SIV MA mutations on Env glycoprotein incorporation and virus infectivity. 293T cells were transfected with wild-type (wt) PBj1.9, or the MA mutant proviral clones. (A) At 48 h posttransfection, viral proteins from cell lysates (CELLS) or virions (VIRIONS) were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and detected by Western blotting with an anti-SIV gp41 MAb (upper panels) and anti-SIV p27 MAb (lower panels). The mobilities of the viral TM and p27 CA proteins are shown, as are the positions of the molecular weight standards. (B) The virus stocks obtained by transfection of 293T cells with wtPBj1.9 or the MA mutant molecular clones were normalized for RT activity and used to infect the MAGI-CCR5 cell line. Cells were stained in situ at 48 h postinfection, and the numbers of blue foci were quantitated microscopically. Virus entry was quantitated as the total number of blue foci obtained by infection with each mutant virus and referred to that obtained on infection with wtPBj1.9 (considered as 100%). The data presented are the mean values and standard deviations of three independent assays.

We then examined the effect of these MA mutations on virus infectivity by the MAGI assay. The supernatants from transfected 293T cells were normalized for RT activity and used to infect MAGI-CCR5 cells. The number of infected cells, as indicated by staining with β-galactosidase, was determined and referred to that of wild-type PBj1.9 (Fig. 2B). As expected, MA mutants that were found to be Env incorporation defective exhibited infectivities that were <10% of the wild-type value. The most drastic effect on infectivity was observed for the L31E and H33A MA mutants. Indeed, the relative infectivities of the L31E and H33A mutants were 0.30% ± 0.10% and 0.66% ± 0.12%, respectively, compared to that of wild-type virions. Unexpectedly, the K18A/R20A MA mutation reduced virus infectivity by ca. 60% without causing any apparent effect on Env incorporation (Fig. 2). This MA mutation may likely affect postentry steps in the virus life cycle. In this regard, evidence supporting a function for the HIV-1 MA N terminus in an early step postinfection has been presented (see references in reference 10). A completely different phenotype to those described above was observed for the R22A/G24V mutant. This MA mutant was ∼2-fold more infectious than wild-type PBj1.9 in the MAGI assay (Fig. 2B), which is in agreement with the increase in Env incorporation levels conferred by this MA mutation with respect to wild-type virions (Fig. 2A). Based on the phenotype observed for the R22A/G24V MA mutant, we introduced additional amino acid substitutions at these SIV MA residues and analyzed their effect on Env incorporation and virus infectivity (see below).

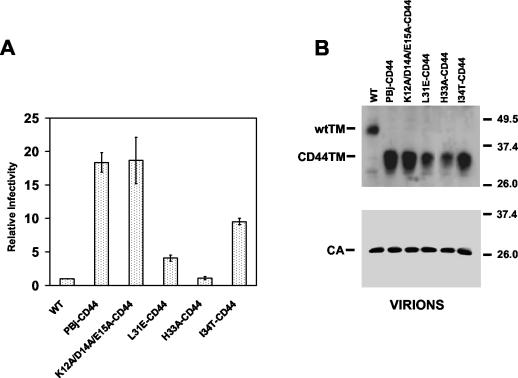

As described above, the K12A/D14A/E15A, L31E, H33A, and I34T MA mutations drastically reduced Env incorporation and virus infectivity. To confirm that the loss in infectivity evidenced by these MA mutant viruses in the MAGI assay was the consequence of their inability to efficiently incorporate the Env glycoprotein, we examined whether truncation of the SIV Env cytoplasmic domain could restore Env packaging into virions and thus render these MA mutants infectious. We have recently shown that the introduction of a stop codon mutation (CD44) into the env gene of SIVSMMPBj1.9, which results in the synthesis of an Env glycoprotein with a 44-amino-acid cytoplasmic domain, significantly increases Env packaging into virions and enhances virus infectivity by 13-fold (27). We therefore introduced the CD44 Env mutation into the proviral DNA clones encoding the K12A/D14A/E15A, L31E, H33A or I34T MA mutations. The resulting molecular clones were used to transfect 293T cells and 48 h after transfection, virus-containing supernatants were harvested, normalized for RT activity and used to infect MAGI-CCR5 cells. Virus stocks of wild-type PBj1.9 (encoding wild-type MA and Env proteins) or PBj-CD44 (encoding wild-type MA and the CD44 Env mutation) were also included in the MAGI assay. While viruses encoding wild-type Env and the K12A/D14A/E15A, L31E, H33A or I34T MA mutations exhibited infectivities corresponding to 6.12, 0.30, 0.66, and 9.90%, respectively, of that of wild-type virions (Fig. 2B), introduction of the CD44 Env mutation into these MA mutants caused a dramatic increase in virus infectivity (Fig. 3A). Indeed, the infectivity of K12A/D14A/E15A-CD44, L31E-CD44, and I34T-CD44 was 18-, 4-, and 9.5-fold higher than that of wild-type virions, whereas the infectivity of H33A-CD44 was similar to that of virions encoding wild-type MA and Env proteins (Fig. 3A). Comparison of the infectivity exhibited by each MA mutant encoding the CD44 Env mutation with that of its wild-type Env-encoding counterpart revealed that virus infectivity was increased by 300-fold (for the K12A/D14A/E15A mutant), 1,356-fold (for the L31E mutant), 164-fold (for the H33A mutant), and 96-fold (for the I34T mutant) as a consequence of the expression of the mutant CD44 Env glycoprotein (compare Fig. 2B and Fig. 3A). Moreover, the differences in the MAGI titers of the MA mutants encoding the CD44 Env mutation correlated with their differential ability to incorporate the mutant Env glycoprotein CD44 (Fig. 3B). Analysis of cell-associated proteins showed that all MA-CD44 mutants exhibited similar levels of mutant Env expression (data not shown). These results indicate that truncation of the Env cytoplasmic domain to 44 amino acids in the K12A/D14A/E15A, L31E, H33A, and I34T MA mutants compensates for the infectivity defect imposed by the MA mutations. Interestingly, the extent to which the CD44 Env mutation reestablishes Env incorporation and infectivity in these MA mutant viruses is dependent on the specific amino acid substitutions that were originally introduced into the SIV MA primary sequence. In contrast, K12A/D14A/E15A, L31E, H33A, and I34T MA mutants pseudotyped with the VSV-G protein exhibited MAGI virus titers that were all similar to that of VSV-G-pseudotyped wild-type PBj1.9 (data not shown), which further confirms that the loss of infectivity observed for these MA mutants is solely due to their inability to incorporate the wild-type SIV Env.

FIG. 3.

Reversion of the Env incorporation defect exhibited by SIV MA mutants by expression of the CD44 Env mutation. 293T cells were transfected in parallel with wild-type (WT) PBj1.9, PBj-CD44, or the MA mutant proviral clones encoding the CD44 Env mutation (K12A/D14A/E15A-CD44; L31E-CD44; H33A-CD44; I34T-CD44). (A) Virus-containing supernatants were normalized for RT activity and used to infect the MAGI-CCR5 cell line. Infected MAGI cells were fixed, stained, and scored 2 days postinfection as described in the legend to Fig. 2. The data presented are averages of at least three assays ± the standard deviations. (B) Analysis of Env incorporation into virions. Virion lysates were prepared from transfected cells (see Materials and Methods), and samples were analyzed by Western blotting with an anti-SIV gp41 (TM) MAb and anti-SIV p27 (CA) MAb.

Substitution mutagenesis of the SIV MA residues Arg22 and Gly24.

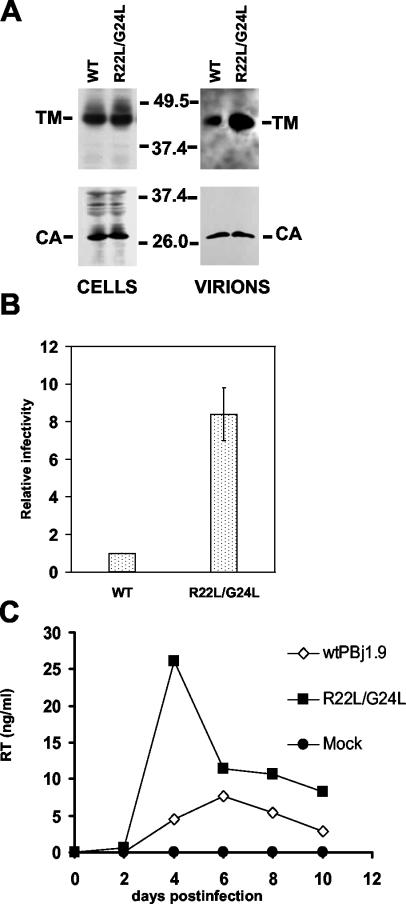

Our experiments to this point indicated that the simultaneous replacement in the SIV MA of Arg22 and Gly24 by alanine and valine, respectively, enhanced Env incorporation into virions and caused a twofold increase in virus infectivity with respect to the wild-type values (Fig. 2). This result prompted us to speculate that hydrophobic amino acid substitutions at MA residues 22 and 24 might cause an upregulation of the incorporation of Env into virions and of virus infectivity. To investigate this possibility, we introduced a number of additional single amino acid substitutions at these MA positions. We found that hydrophobic substitution mutations, such as R22A, R22L, and G24L increased virus MAGI titers by 1.29-, 3.6-, and 2-fold, respectively, relative to the wild-type value. This effect correlated with an upregulation of the levels of virion-associated Env glycoprotein: quantitation of wild-type and mutant virion proteins in four independent experiments gave a TM to p27 ratio of 1.4 ± 0.1 (R22A mutant); 3.0 ± 0.3 (R22L mutant); and 2.08 ± 0.02 (G24L mutant) relative to that of wild-type virions. In contrast, polar substitutions at these MA positions, such as, R22Q, G24N, and G24T were detrimental to virus infectivity (data not shown). Remarkably, introduction of the R22L/G24L double amino acid substitution into the PBj1.9 MA-coding region resulted in a dramatic enhancement of both Env packaging into virions and virus infectivity (Fig. 4A and B). Indeed, the levels of TM protein relative to p27 in the R22L/G24L mutant virions were (5.8 ± 0.7)-fold higher than those in wild-type virions (average of three independent experiments ± the standard deviation). Moreover, the single-cycle infectivity of the R22L/G24L mutant was eightfold higher than that of wild-type PBj1.9 (Fig. 4B). To investigate whether the R22L/G24L double mutation had an effect on virus replication, CEMx174 cells were infected with supernatants from cells transfected with wild-type PBj1.9 or the R22L/G24L molecular clones. Virus replication was monitored over time by measuring RT levels in the cell-free culture supernatants. As shown in Fig. 4C, we found that virus production peaked earlier with the R22L/G24L double mutant than with the wild-type virus: the R22L/G24L mutant virus peaked on day 4 postinfection (26.14 ng of RT/ml), whereas peak virus production in wild-type PBj1.9-infected CEMx174 cells occurred 2 days later (7.64 ng of RT/ml). Moreover, the RT levels in the R22L/G24L mutant-infected cultures remained higher than in those infected with the wild-type virus over the time period examined. The replication data therefore demonstrate that the R22L/G24L double amino acid substitution in MA confers to SIV a replication advantage in susceptible cells relative to the kinetics displayed by the wild-type virus.

FIG. 4.

Characterization of the R22L/G24L MA mutant. (A) 293T cells were transfected in parallel with wild-type (WT) PBj1.9 or the R22L/G24L mutant proviral clone. Cell- and virion-associated proteins were detected by Western blotting with an anti-SIV gp41 MAb and anti-SIV p27 MAb. (B) MAGI infectivities of virus stocks produced by transfection of 293T cells. Virus-containing supernatants were normalized for RT activity and used to infect MAGI-CCR5 cells. Virus entry was quantitated as described in the legend to Fig. 2. The data presented are averages of at least three assays ± the standard deviations. (C) Replication kinetics of the R22L/G24L MA mutant. Virus stocks, obtained by transfection of 293T cells, were normalized for RT activity and used to infect the CEMx174 cell line. Virus replication was assessed by measuring RT activity at 2-day intervals postinfection. Mock, mock-infected cells.

Rescue of the Env incorporation defective phenotype of the L31E and I34T MA mutants by the R22L/G24L double amino acid substitution.

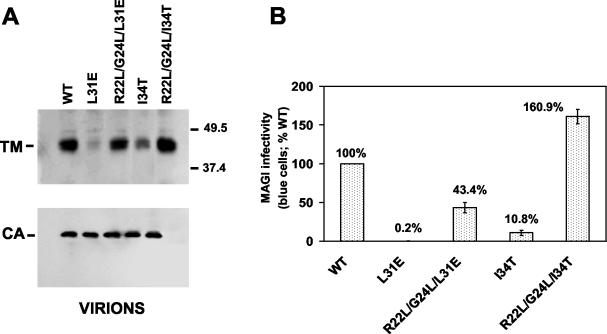

To determine whether the R22L/G24L double amino acid substitution could compensate for the Env incorporation and infectivity defects imposed by single point mutations in the SIV MA, we introduced the R22L/G24L mutation into the L31E and I34T molecular clones. These MA mutations were chosen because they differ in the extent to which they impair virus infectivity: the L31E mutation resulted in essentially a complete loss of virus infectivity, whereas the I34T mutant viruses were slightly infectious, exhibiting a virus titer that represented ca. 10% of the wild-type value (Fig. 2B). Proviral DNA clones encoding the R22L/G24L/L31E or R22L/G24L/I34T triple mutation were transfected into 293T cells and 48 h after transfection, viruses were purified by ultracentrifugation of the clarified supernatants through a sucrose cushion. Viral proteins were detected by immunoblotting with MAbs directed against SIV gp41 or p27. For comparison, the wild-type PBj1.9 and the parental L31E and I34T MA mutants were included in these experiments. Analysis of cell-associated viral proteins indicated that all MA mutants showed wild-type levels of Gag and Env expression (data not shown). When we analyzed the virion fractions, we found that the amount of virion gp41 was significantly increased by the introduction of the R22L/G24L mutation in the context of the L31E or I34T MA mutant clones (Fig. 5A), which demonstrates that the R22L/G24L double amino acid substitution can compensate for the Env incorporation defect imposed by the L31E or the I34T MA mutation. To examine whether the increase in Env incorporation observed with the R22L/G24L/L31E and R22L/G24L/I34T triple mutants relative to that of the L31E and I34T single mutants, respectively, was accompanied by improved virus infectivity, virus-containing supernatants from 293T cells transfected with the triple or the single mutant clones were normalized for RT activity and used to infect MAGI-CCR5 cells. Interestingly, the R22L/G24L mutation increased infectivity of the L31E virions by 197-fold, corresponding to 43.4% of the wild-type PBj1.9 virus titer (Fig. 5B). In the case of the I34T MA mutant, introduction of the R22L/G24L substitution enhanced virus infectivity by 16-fold, representing 160% of the wild-type values. These results clearly indicate that the R22L/G24L mutation can substantially or even completely reverse the impairment in Env incorporation and virus infectivity imposed by MA mutations.

FIG. 5.

The R22L/G24L MA mutation restores Env protein incorporation into the L31E and I34T MA mutant virions. (A) 293T cells were transfected in parallel with wild-type (WT) PBj1.9, or the mutant molecular clones L31E, I34T, R22L/G24L/L31E, and R22L/G24L/I34T. At 48 h posttransfection, viral proteins from virion lysates were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and probed with anti-SIV gp41 (TM) and anti-SIV p27 (CA) MAbs. (B) MAGI infectivities of virus stocks produced by transfection of 293T cells. Virus-containing supernatants were normalized for RT activity and used to infect the MAGI-CCR5 cell line. Two days postinfection, the cells were fixed, stained in situ for β-galactosidase as an indicator of infection, and the blue cells were counted. The data presented are averages of at least three assays ± the standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

The incorporation of the HIV/SIV Env glycoproteins into virions is a key step in the viral replication cycle. Increasing evidence for HIV-1 and SIV suggests that specific interactions between the MA protein and the TM cytoplasmic domain mediate Env incorporation into virions (4, 7, 11, 12, 18, 19, 26, 29, 35). However, the specific residues in the SIV MA that are involved in the incorporation of the Env glycoprotein into virions remained to be identified. We therefore performed a mutational analysis to determine whether highly conserved residues within the SIV MA N terminus play any critical roles in virus infectivity and Env glycoprotein incorporation. Our results demonstrate that mutations in α-helix H1 (K12A/D14A/E15A) or α-helix H2 (L31E, H33A and I34T) drastically reduce both Env incorporation and virus infectivity without affecting virus assembly and release. These results are in line with previous work with HIV-1 that showed that charged substitutions at MA residues Leu13 (α-helix H1), Leu31 (α-helix H2), and Val35 (α-helix H2) inhibit Env incorporation into virions (11, 12). In addition, our data establish that hydrophobic amino acid substitutions at SIV MA residues 22 and 24 (R22A/G24V, R22L, G24L, and R22L/G24L) increase the levels at which the Env glycoprotein is incorporated into virions and enhance virus infectivity relative to the wild-type virus. Of note, residues 22 and 24 map to a β-turn within the region connecting the two N-terminal α-helices of the SIV MA (Brookhaven Protein Data Bank accession number 1ecw). Remarkably, the R22L/G24L MA mutation augments single-cycle virus infectivity eightfold with respect to wild-type MA-encoding virions, and this effect correlates with a similar increase in the levels of virion-associated TM protein. In addition, the R22L/G24L MA mutant replicates with faster kinetics in CEMx174 cells and attains higher titers than the wild-type virus. To our knowledge, this is the first study reporting that in lentiviruses the processes of Env incorporation and virus infectivity can be upregulated by specific mutations in the MA domain of the Gag precursor. This finding strongly supports the notion that the SIV MA plays an active role in the recruitment of Env into virions. An interesting outcome of our studies is that the R22L/G24L MA mutation is sufficient to reverse the Env incorporation and infectivity defects imposed by single-point mutations in the SIV MA. In this regard, Freed and Martin (12) have reported that long-term passage of the Env incorporation-defective L13E HIV-1 MA mutant resulted in the emergence of second-site revertants bearing a V35I MA change that compensated for the defect imposed by the original MA mutation. However, the V35I mutation alone had no significant effect on HIV-1 Env incorporation. This phenotype differs from that of the R22L/G24L SIV MA mutant characterized in our study, which per se enhances Env incorporation and virus infectivity.

It has been proposed that the SIV MA trimerization results in the formation of a lattice-like structure that presents holes which can potentially accommodate the cytoplasmic tails of the Env glycoprotein trimers (9, 33). Interestingly, the region comprised within α-helix H1 and the beginning of α-helix H2 lies at the perimeter of the holes formed by the SIV MA network, with the β-turn structure (residues 22 to 25) protruding into these holes. This spatial arrangement makes this region a likely candidate to interact with the Env glycoprotein. It could then be speculated that the SIV MA amino acid substitutions characterized here may impair or favor specific interactions between the MA and the TM cytoplasmic domain. Alternatively, in the absence of specific intermolecular interactions, these mutations may modify the MA trimer-derived structure, thereby inhibiting or enhancing the ability of the MA trimers to accommodate the long cytoplasmic domains of the SIV Env glycoprotein complexes. Although the oligomerization of the SIV MA into trimers help explain the process of Env incorporation into virions, the relevance of this structure in SIV particle formation requires further investigation. However, studies performed with HIV-1 have provided evidence that trimerization of the MA domain accompanies Gag oligomerization during virus assembly: (i) cryoelectron microscopy of immature HIV-1 particles revealed that the Gag protein organizes into repeating units of dimers of trimers, which were interpreted as the result of dimer interactions of the CA domain and trimer ones of the MA domain (14); (ii) analysis of the multimeric state of the HIV-1 Gag protein expressed in insect cells by means of velocity sedimentation assays suggested that the MA domain contributes to the oligomerization of Gag to the level of trimer and that these Gag trimers are one of the assembly intermediates in the process of particle formation (28); and (iii) the nuclear magnetic resonance structure of the MA domain of a 283-residue N-terminal fragment of HIV-1 Gag is similar to the X-ray structure of the mature MA trimer (34).

In summary, our characterization of an SIV MA region whose mutation results in the up- or downregulation of Env incorporation into virions provides further insight into the molecular mechanism involved in the association of the Env glycoprotein with Gag particles and may be useful for the rational design of antiviral strategies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants A-13532/98 and 14116-40 from the Fundación Antorchas (Argentina) to S.A.G. and by AIDS Fogarty International Research Collaboration award AIDS-FIRCA R03 TW00947. J.M.M. and C.C.P.C. are postgraduate fellows of the National Research Council of Argentina (CONICET). J.L.A. and S.A.G. are career investigators of CONICET.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bryant, M., and L. Ratner. 1990. Myristoylation-dependent replication and assembly of human immunodeficiency virus 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:523-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Celma, C. C. P., J. M. Manrique, J. L. Affranchino, E. Hunter, and S. A. González. 2001. Domains in the simian immunodeficiency virus gp41 cytoplasmic tail required for envelope incorporation into particles. Virology 283:253-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chackerian, B., E. M. Long, P. A. Luciw, and J. Overbaugh. 1997. HIV-1 coreceptors participate in post-entry stages of the virus replication cycle and function in SIV infection. J. Virol. 71:3932-3939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cosson, P. 1996. Direct interaction between the envelope and matrix proteins of HIV-1. EMBO J. 15:5783-5788. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delchambre, M., D. Gheysen, D. Thinès, C. Thiriart, C. Jacobs, E. Verdin, M. Horth, A. Burny, and F. Bex. 1989. The Gag precursor of the simian immunodeficiency virus assembles into virus-like particles. EMBO J. 8:2653-2660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dewhurst, S., J. E. Embretson, D. C. Anderson, J. I. Mullins, and P. N. Fultz. 1990. Sequence analysis and acute pathogenicity of molecularly cloned SIVSMM-PBj14. Nature 345:636-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorfman, T., F. Mammano, W. A. Haseltine, and H. G. Göttlinger. 1994. Role of the matrix protein in the virion association of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein. J. Virol. 69:1689-1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dubay, J. W., S. J. Roberts, B. H. Hahn, and E. Hunter. 1992. Truncation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane glycoprotein cytoplasmic domain blocks virus infectivity. J. Virol. 66:6616-6625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forster, M. J., B. Mulloy, and M. V. Nermut. 2000. Molecular modeling study of HIV p17gag (MA) protein shell utilizing data from electron microscopy and X-ray crystallography. J. Mol. Biol. 298:841-857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freed, E. O. 1998. HIV-1 Gag proteins: diverse functions in the virus life cycle. Virology 252:1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freed, E. O., and M. A. Martin. 1995. Virion incorporation of envelope glycoproteins with long but not short cytoplasmic tails is blocked by specific, single amino acid substitutions in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix. J. Virol. 69:1984-1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freed, E. O., and M. A. Martin. 1996. Domains of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix and gp41 cytoplasmic tail required for envelope incorporation into virions. J. Virol. 70:341-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freed, E. O., J. M. Orenstein, A. J. Buckler-White, and M. A. Martin. 1994. Single amino acid changes in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix protein block virus particle production. J. Virol. 68:5311-5320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuller, S. D., T. Wilk, B. E. Gowen, H.-G. Kräusslich, and V. M. Vogt. 1997. Cryo-electron microscopy reveals ordered domains in the immature HIV-1 particle. Curr. Biol. 7:729-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gelderblom, H. R., E. H. S. Hausmann, M. Ozel, G. Pauli, and M. A. Koch. 1987. Fine structure of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and immunolocalization of structural proteins. Virology 156:171-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.González, S. A., and J. L. Affranchino. 1995. Mutational analysis of the conserved cysteine residues in the simian immunodeficiency virus matrix protein. Virology 210:501-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.González, S. A., and J. L. Affranchino. 1998. Substitution of leucine 8 in the simian immunodeficiency virus matrix protein impairs particle formation without affecting N-myristylation of the Gag precursor. Virology 240:27-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.González, S. A., J. L. Affranchino, H. R. Gelderblom, and A. Burny. 1993. Assembly of the matrix protein of simian immunodeficiency virus into virus-like particles. Virology 194:548-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.González, S. A., A. Burny, and J. L. Affranchino. 1996. Identification of domains in the simian immunodeficiency virus matrix protein essential for assembly and envelope glycoprotein incorporation. J. Virol. 70:6384-6389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Göttlinger, H. G., J. G. Sodroski, and W. A. Haseltine. 1989. Role of the capsid precursor processing and myristoylation in morphogenesis and infectivity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:5781-5785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henderson, L. E., M. A. Bowers, R. C. Sowder II, S. A. Serabyn, D. G. Johnson, J. W. Bess, Jr., L. O. Arthur, D. K. Bryant, and C. Fenselau. 1992. Gag proteins of the highly replicative MN strain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: posttranslational modifications, proteolytic processings, and complete amino acid sequences. J. Virol. 66:1856-1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hunter, E. 1994. Macromolecular interactions in the assembly of HIV and other retroviruses. Semin. Virol. 5:71-83. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kent, K. A., E. Rud, T. Corcoran, C. Powell, C. Thiriart, C. Collignon, and E. J. Stott. 1992. Identification of two non-neutralizing epitopes on simian immunodeficiency virus envelope using monoclonal antibodies. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 8:1147-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kimpton, J., and E. Emerman. 1992. Detection of replication-competent and pseudotyped human immunodeficiency virus with a sensitive cell line on the basis of activation of an integrated β-galactosidase gene. J. Virol. 66:2232-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mammano, F., E. Kondo, J. Sodroski, A. Bukovsky, and H. G. Göttlinger. 1995. Rescue of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix protein mutants by envelope glycoproteins with short cytoplasmic domains. J. Virol. 69:3824-3830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manrique, J. M., C. C. P. Celma, J. L. Affranchino, E. Hunter, and S. A. González. 2001. Small variations in the length of the cytoplasmic domain of the simian immunodeficiency virus transmembrane protein drastically affect envelope incorporation and virus entry. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 17:1615-1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morikawa, Y., D. J. Hockley, M. V. Nermut, and I. M. Jones. 2000. Roles of matrix, p2, and N-terminal myristoylation in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag assembly. J. Virol. 74:16-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murakami, T., and E. O. Freed. 2000. Genetic evidence for an interaction between human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix and α-helix 2 of the gp41 cytoplasmic tail. J. Virol. 74:3548-3554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ono, A., and E. O. Freed. 1999. Binding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag to membrane: role of the matrix amino terminus. J. Virol. 73:4136-4144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ono, A., M. Huang, and E. O. Freed. 1997. Characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix revertants: effects on virus assembly, Gag processing, and Env incorporation into virions. J. Virol. 71:4409-4418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paillart, J.-C., and H. G. Göttlinger. 1999. Opposing effects of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix mutations support a myristyl switch model of Gag membrane targeting. J. Virol. 73:2604-2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rao, Z., A. S. Belyaev, E. Fry, P. Roy, I. M. Jones, and D. I. Stuart. 1995. Crystal structure of SIV matrix antigen and implications for virus assembly. Nature 378:743-747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang, C., Y. Ndassa, and M. F. Summers. 2002. Structure of the N-terminal 283-residue fragment of the immature HIV-1 Gag polyprotein. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9:537-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wyma, D. J., A. Kotov, and C. Aiken. 2000. Evidence for a stable interaction of gp41 with Pr55Gag in immature human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particles. J. Virol. 74:9381-9387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu, X., X. Yuan, Z. Matsuda, T.-H. Lee, and M. Essex. 1992. The matrix protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is required for incorporation of viral envelope protein into mature virions. J. Virol. 66:4966-4971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu, X., X. Yuan, M. F. McLane, T.-H. Lee, and M. Essex. 1993. Mutations in the cytoplasmic domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane protein impair the incorporation of Env proteins into mature virions. J. Virol. 67:213-221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yuan, X., X. Yu, T.-H. Lee, and M. Essex. 1993. Mutations in the N-terminal region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix protein block intracellular transport of the Gag precursor. J. Virol. 67:6387-6394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou, W., L. J. Parent, J. W. Wills, and M. D. Resh. 1994. Identification of a membrane-binding domain within the amino-terminal region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein which interacts with acidic phospholipids. J. Virol. 68:2556-2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]