Abstract

Shigella and Salmonella use similar type III secretion systems for delivering effector proteins into host cells. This secretion system consists of a base anchored in both bacterial membranes and an extracellular “needle” that forms a rod-like structure exposed on the pathogen surface. The needle is composed of multiple subunits of a single protein and makes direct contact with host cells to facilitate protein delivery. The proteins that make up the needle of Shigella and Salmonella are MxiH and PrgI, respectively. These proteins are attractive vaccine candidates because of their essential role in virulence and surface exposure. We therefore isolated, purified, and characterized the monomeric forms of MxiH and PrgI. Their far-UV circular dichroism spectra show structural similarities with hints of subtle differences in their secondary structure. Both proteins are highly helical and thermally unstable, with PrgI having a midpoint of thermal unfolding (Tm) near 37°C and MxiH having a value near 42°C. The two proteins also have comparable intrinsic stabilities as measured by chemically induced (urea) unfolding. MxiH, however, with a free energy of unfolding (ΔG°0,un) of 1.6 kcal/mol, is slightly more stable than PrgI (1.2 kcal/mol). The relatively low m-values obtained for the urea-induced unfolding of the proteins suggest that they undergo only a small change in solvent-accessible surface area. This argues that when MxiH and PrgI are incorporated into the needle complex, they obtain a more stable structural state through the introduction of protein–protein interactions.

Keywords: type III secretion, MxiH, Shigella, needle protein, protein stability, protein structure/folding, stability and mutagenesis, structure/function studies, other spectroscopies, circular dichroism, fluorescence

Shigella flexneri is a bacterial pathogen that causes human bacillary dysentery, a disease characterized by pathogen invasion of the colonic epithelium (Niyogi 2005). As an integral part of its virulence arsenal, S. flexneri possesses a complex cell surface apparatus required for the delivery of bacterial proteins into human cells to promote uptake (Mota and Cornelis 2005). This “type III secretion system” (TTSS) is composed of 25–30 proteins that form a tripartite structure composed of a bulb located in the bacterial cytoplasm, which controls export via the apparatus, a basal structure that spans both bacterial membranes and provides a conduit for protein secretion to the bacterial surface, and an external needle structure that extends ~60 nm from the bacterial outer membrane (Blocker et al. 2003). This needle possesses a 2.5- to 3.0-nm channel, which connects the secretion channel with the host cell’s membrane (Tamano et al. 2000; Blocker et al. 2001).

The needle of S. flexneri is composed of multiple copies of a single protein called MxiH (Allaoui et al. 1992; Hueck 1998; Blocker et al. 2001; Jouihri et al. 2003). The related gastrointestinal pathogen Salmonella typhimurium possesses a similar TTSS, which has an external needle composed of multiple copies of the protein PrgI (Kimbrough and Miller 2000; Kubori et al. 2000). The exposed portion of the TTSS of Shigella and Salmonella is possibly involved in sensing the approach of the pathogen to a target cell and triggering the secretion of the effector proteins that subvert normal cell processes (Kenjale et al. 2005). Thus, these needles and their component proteins are attractive candidates for antigens that might induce a protective immune response against these important pathogens. It is therefore important to fully understand the physical, biochemical, and biological properties of these potential vaccine candidates.

Recently, Blocker et al. (2003; Cordes et al. 2003) described the helical packing of the Shigella needle and found it to be similar to that of the Gram-negative bacterial flagellar filament, despite the fact that, at 83 amino acids, it is much smaller than flagellin. Like the polymerizing core of flagellin, MxiH is predicted to have a secondary structure composed largely of α-helix with a minor β-strand component and extensive turns (Kenjale et al. 2005). Furthermore, if the flagellin analogy is appropriate, it is likely that deleting a portion of the C terminus of the needle proteins from various TTSSs should allow them to be purified in monomeric form for biophysical and biochemical study (Yonekura et al. 2003).

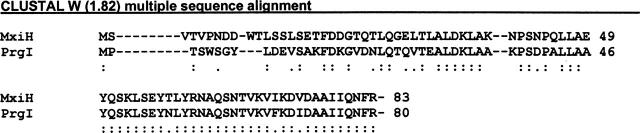

The Shigella and Salmonella needle proteins have a high degree of sequence similarity (Fig. 1) and are predicted to have similar secondary structures. In this study, we describe the purification of monomeric forms of these proteins after removal of their five C-terminal amino acid residues. In contrast, the full-length proteins appear to polymerize and aggregate when expressed in Escherichia coli (data not shown). The soluble Δ5 variants provide excellent candidates for structural studies. Thus, we provide the first biophysical characterization of the structure and stability of needle protein monomers from Shigella and Salmonella in this work. The reversibility of the folding/unfolding of the two proteins allowed us to use spectroscopic and calorimetric methods to also thermodynamically characterize their stability properties. In this form, they are also strong candidates for high-resolution structure determination.

Figure 1.

MxiH and PrgI primary sequence alignment. Below the sequences, : designates identity and . indicates similarity.

Results

Far-UV CD spectra and secondary structure analysis

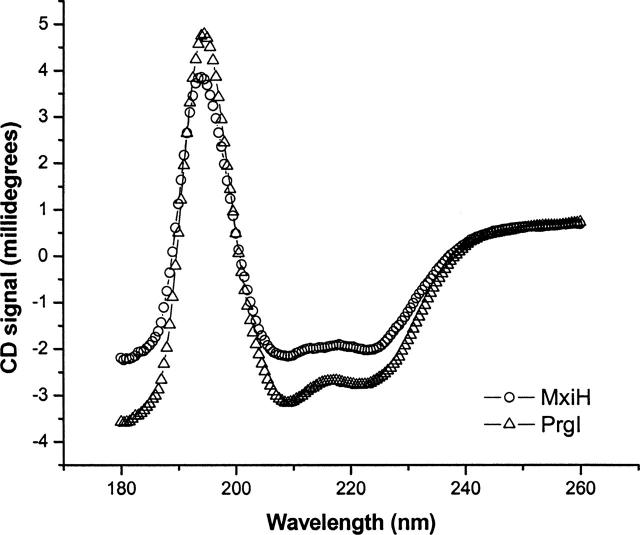

Far-UV CD spectra of MixH and PrgI (Fig. 2) show that they have a similar secondary structure with high helical content. Deconvolution and analysis of the spectra using Dichroweb (Whitmore and Wallace 2004) suggests that that PrgI contains more helix than MxiH (Table 1). At 10°C, the recombinantly expressed MxiH has a little >50% α-helical content and ~20% β-sheet, whereas PrgI has almost 70%α-helix and ~10%β-sheet. Additionally, MxiH appears to have more random and turn structure than its Salmonella homolog. At temperatures as low as 25°C, both proteins seem to lose a significant amount of secondary structure, especially with respect to helical content (Table 1). This indicates that both proteins may be relatively unstable (see below).

Figure 2.

Far-UV CD spectra for MxiH and PrgI at 10°C at a protein concentration of 50 μM using a 0.01-cmpath-length cell. The circles show the spectrum for MxiH, and the triangles show the spectrum of PrgI. The data shown are an average of greater than or equal to two trials.

Table 1.

Summary of results from the deconvoluted far-UV CD spectra into various components of secondary structure in MxiH and PrgI

| 10°C | 25°C | |||||||

| Protein | Helix | Strands | Turns | Random | Helix | Strands | Turns | Random |

| MxiH | 53 | 18 | 14 | 15 | 50 | 19 | 11 | 20 |

| PrgI | 69 | 10 | 9 | 11 | 59 | 13 | 13 | 12 |

Reported values are percentages of the total structure with an estimated uncertainty of 2.3%.

Thermally induced unfolding as monitored by CD and second-derivative UV absorbance spectroscopy

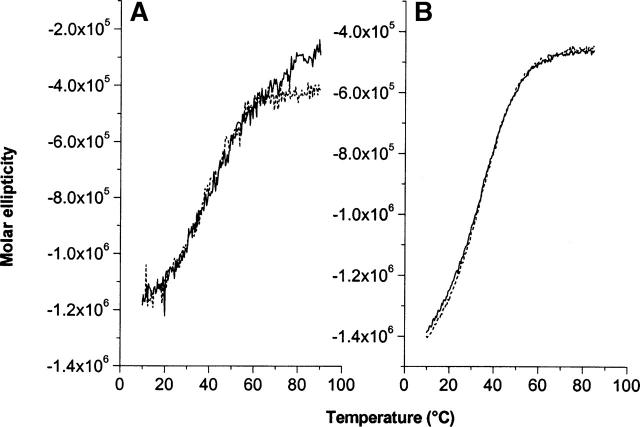

To examine the relative stability of MxiH and PrgI, both proteins were examined as a function of temperature. Each demonstrates >90% thermal unfolding reversibility after heating to 90°C as monitored by CD (Fig. 3) and UV absorbance spectroscopy (Figs. 4, 5). Analysis of the CD unfolding curves in Figure 3 yield an approximate Tm of 42°C and 37.5°C for MxiH and PrgI, respectively. Correspondingly, nearly indistinguishable ΔH values of 22.3 and 23.9 kcal/mol are seen.

Figure 3.

Thermal unfolding of MxiH (A) and PrgI (B) as monitored by CD. The solid black traces represent unfolding, and the dashed lines, the unfolding of proteins previously heated to >90°C and then cooled.

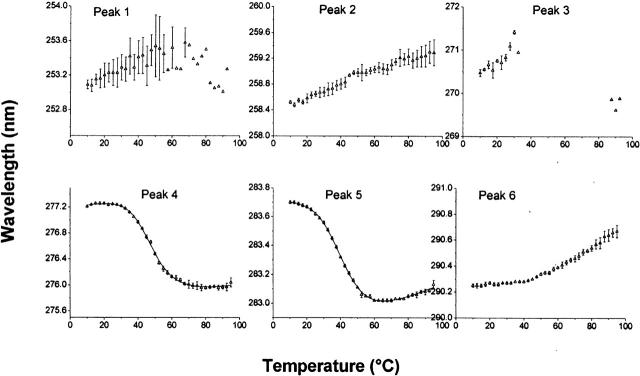

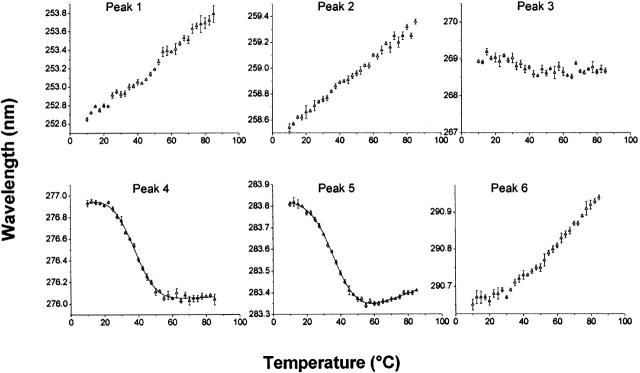

Figure 4.

MxiH thermal unfolding as monitored by UV absorbance spectroscopy. Data are derived from second derivatives of the UV spectra as a function of temperature. Peaks 1, 2, and 3 represent contributions from Phe; peaks 3, 4, and 5 from Tyr; and peaks 5 and 6 from Trp. (Peaks 3 and 5 are combination peaks.) The line in the data for peaks 4 and 5 is the fit of a two-state unfolding model to the data.

Figure 5.

PrgI thermal unfolding as monitored by UV absorbance. Data are derived from second derivatives of the UV spectra at various temperatures as described in the legend to Figure 4.

To examine the effects of thermal stress on the tertiary structure, high-resolution second-derivative UV absorption spectroscopy was employed. This technique has the advantage that the three different types of aromatic residues tend to be dispersed nonuniformly throughout most protein structures, thereby providing a somewhat different view of protein behavior than intrinsic fluorescence spectroscopy, which in this case relies upon changes in a single Trp residue (see below). The high-resolution second-derivative spectra of the needle proteins consist of six peaks (not illustrated). Peaks 1, 2, and 3 represent contributions from Phe; 4 and 5, from Tyr; and 5 and 6, from Trp (peak 5 is a combination peak) (Figs. 4, 5). The three Phe and the highest wavelength of the Trp peaks show little evidence for well-defined thermal transitions for both proteins. In contrast, Tyr peaks manifest typical thermal unfolding curves. Assuming a two-state unfolding model, the Tyr profiles yielded Tm and corresponding ΔH values that are similar, within error limits, to those observed in the CD studies (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of the thermodynamic parameters extracted from the analysis of the thermal induced unfolding curves as monitored by CD and second-derivative UV absorbance spectroscopy

| UV | ||||||

| CD | Tm | ΔH | ||||

| Protein | Tm | ΔH | Peak4 | Peak5 | Peak4 | Peak5 |

| MxiH | 42 ± 0.1 | 22.3 ± 2.1 | 48.0 ± 2.3 | 42.7 ± 2.3 | 28.8 ± 3.0 | 24.9 ± 1.9 |

| PrgI | 37.5 ± 0.5 | 23.9 ± 0.4 | 36.0 ± 3.4 | 35.7 ± 4.8 | 22.0 ± 7.6 | 26.0 ± 1.1 |

All Tm values reported are in units of °C, and the enthalpy values, in kcal/mol. The values shown are ± standard error with n = 2 or 3.

The optical density of the solution was also monitored at 350 nm as a function of temperature to search for macroscopic aggregation. No detectable increase in the optical density was seen as the temperature was increased (not shown). Thus, the thermal transitions observed do not result in detectable aggregation, consistent with their reversibility.

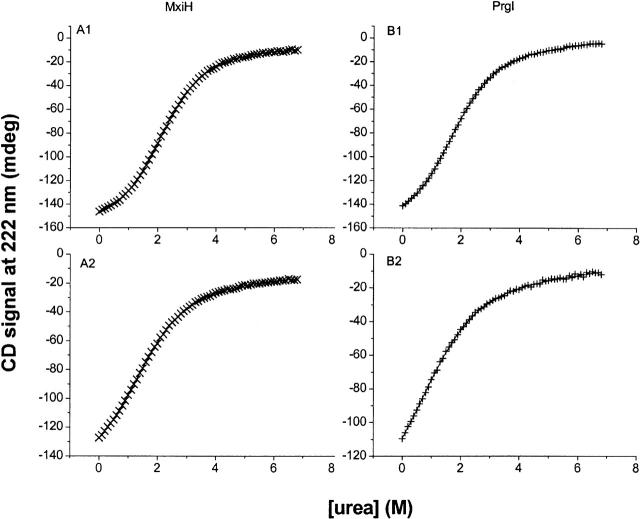

Urea-induced unfolding as monitored by CD

To further access the stability of these proteins, urea unfolding studies were performed using the intrinsic CD signal of the proteins at 222 nm to monitor changes in secondary structure as a function of urea concentration. The unfolding curves, as seen in Figure 6, show some degree of cooperativity (10°C) (Fig. 6A1,A2), which diminishes with increasing temperature (25°C) (Fig. 6B1,B2). The hyperbolic nature of the unfolding curves at 25°C, as opposed to the more sigmoidal curve observed in the lower temperature experiments, indicates a loss in cooperativity. From the urea unfolding data, the intrinsic free energy of unfolding (ΔG°0,un) and their dependence on denaturant concentration (m-values) of the proteins were calculated using a nonlinear least-square analyses for a two-state unfolding transition. These results are reported in Table 3. The results show that MxiH is slightly more stable than PrgI and also has a higher m-value, indicating that more surface area of MxiH is exposed during unfolding than during PrgI unfolding.

Figure 6.

Urea-induced unfolding of MxiH and PrgI as monitored by CD at 222 nm. Panels A1 and A2 show MxiH, and panels B1 and B2 show PrgI. The upper panels (A1,B1) show data acquired at 10°C, and the lower panels (A2,B2) show data acquired at 25°C.

Table 3.

Summary of results from a two-state analysis of the urea-induced unfolding of MxiH and PrgI at 10°C and 25°C

| 10°C | 25°C | |||

| Protein | ΔG°0,un (kcal/mol1−) | m (kcal/mol−1 M−1) | ΔG°0,un (kcal/mol−1) | m (kcal/mol−1 M−1) |

| MxiH | 1.62 ± 0.01 | 0.82 ± 0.02 | 0.89 ± 0.16 | 0.69 ± 0.00 |

| PrgI | 1.19 ± 0.03 | 0.77 ± 0.01 | 0.44 ± 0.02 | 0.62 ± 0.02 |

The errors reported are standard errors (with n=2). The free energy of unfolding (ΔG°0,un) is the extrapolated free energy of unfolding back to zero denaturant concentration.

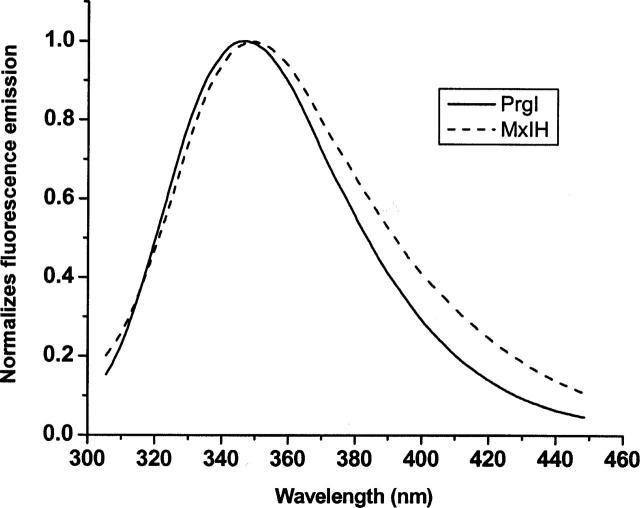

Intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence

The fluorescence emission spectra of MxiH and PrgI (Fig. 7) show only very subtle differences with λmax values of 349.5 and 347.5 nm, respectively. These values indicate extensive exposure of the proteins’s single Trp residue to the solvent. This is consistent with the position of the 290 nm absorption peak (peak 6 in Figs. 4, 5). Both techniques suggest that the MxiH indole is slightly more exposed than the corresponding residue in PrgI.

Figure 7.

Typical normalized fluorescence emission spectra of MxiH and PrgI (50 μM) in PBS at pH 7.0. Samples were excited at 295 nm and the emission monitored from 302 nm to 450 nm. PrgI is shown with the solid and MxiH is shown with a dashed line.

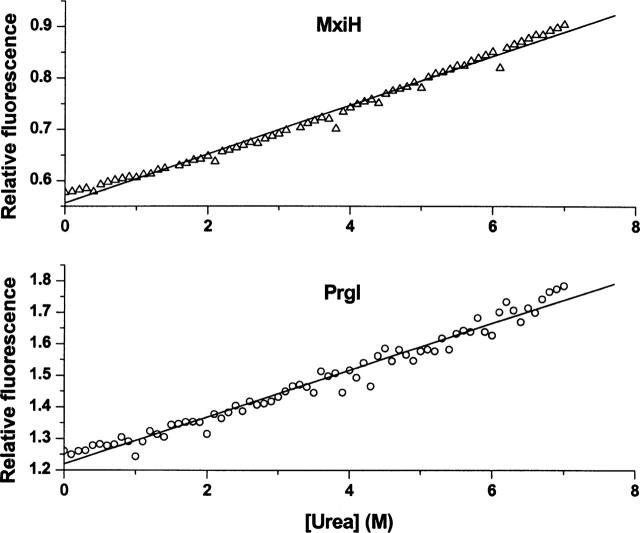

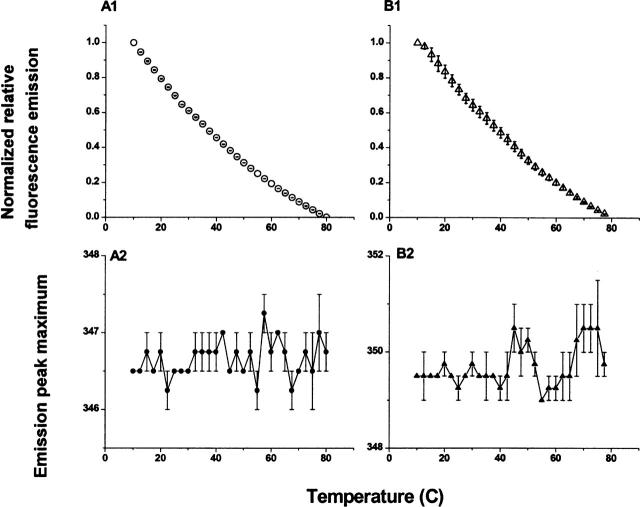

Urea-induced unfolding monitored by Trp fluorescence (Fig. 8) shows a linear change in Trp fluorescence with increased urea concentration, with the slope of the curves at 0.04 and 0.07 M−1 for MxiH and PrgI, respectively. Model studies with the tryptophan derivative, N-acetyltryptophanamide (NATA), find that there is a linear dependence of indole fluorescence on urea concentration with a slope of 0.07M−1 (Eftink 1994). Thus, our results suggest that the urea-induced changes seen here are simply due to direct effects of urea on the MxiH and the PrgI indole side chains. Fluorescence based thermal unfolding studies show a curvilinear dependence of Trp fluorescence on temperature (Fig. 9). Furthermore, the emission peak position does not change with temperature, supporting the conclusion that the Trp environment does not significantly change.

Figure 8.

Urea-induced unfolding of MxiH and PrgI at 10°C as monitored by Trp fluorescence with excitation at 295 nm. The proteins were examined at 50 μM. Panels A and B represent MxiH and PrgI with slopes 0.05 and 0.07 M−1, respectively.

Figure 9.

Thermal unfolding curves of MxiH and PrgI as monitored by Trp fluorescence. Panels A1 and A2 represent PrgI, while panels B1 and B2 represent MxiH. The upper panels (A1,B1) show the intensity of the fluorescence emission at 340 nm as a function of temperature. The lower panels (A2,B2) show the wavelength of the emission maximum as function of temperature.

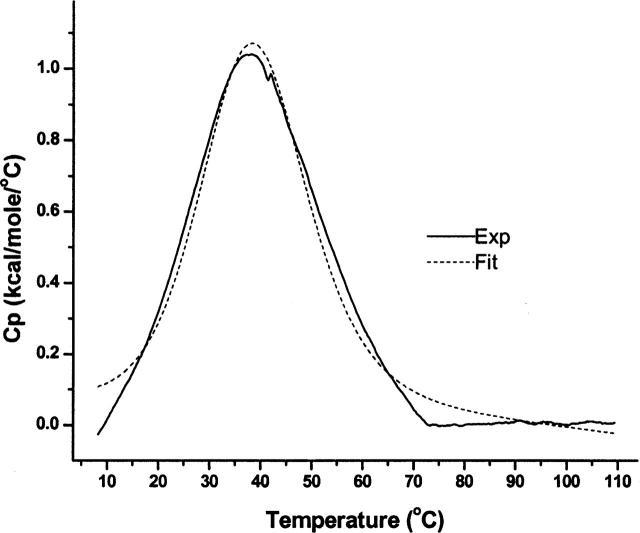

Differential scanning calorimetry of PrgI

PrgI produces a distinct DSC endotherm with a Tm of 38°C and a ΔH of 27.9 kcal/mol, in excellent agreement with the CD and absorbance results (Fig. 10). Surprisingly, for reasons that are unknown at this time, we were unable to obtain a well-defined DSC endotherm for MxiH, even at high protein concentrations.

Figure 10.

PrgI DSC endotherm with buffer subtraction and baseline correction at a protein concentration of 1.82 mg/mL. A two-state unfolding model was used to fit the data and the values of Tm=38.1°C ± 0.3 and ΔH=27.9 kcal/mol ± 0.1 were found. The solid line is from a representative experiment with the dashed line showing a best fit analysis.

Discussion

These results represent the first structural data for the MxiH and PrgI needle proteins of Shigella and Salmonella, and thus provide a starting point for more detailed structural and functional characterization of these proteins. Both purified needle proteins were highly soluble in contrast to the needle complexes. Thus, the C-terminal deletion mutants of MxiH and PrgI provided suitable targets for initial structural and stability studies of the needle proteins. The far-UV CD spectra of MxiH and PrgI reveal a strong similarity in structure between the two proteins. They are both rich in α-helix (>50%) with less than a quarter of the structure in β-sheet (see Table 1), which is consistent with their predicted secondary structure. Thermally induced unfolding studies demonstrate that both proteins are rather unstable as monomeric proteins with comparable thermodynamic parameters. The thermally induced unfolding monitored by CD shows that both proteins reversibly unfold without aggregating. The midpoints of the thermal transitions of 42°C and 37.5°C for MxiH and PrgI, respectively, are relatively low for globular proteins with such an important function as involvement in the invasive process of the bacteria. Several considerations temper the significance of these observations. The transitions actually begin at much lower temperatures than the Tms with evidence for the initiation of the thermally induced changes at the lowest temperatures examined (i.e., 10°C). Furthermore, urea appears to induce the change at relatively low concentrations of the chaotrope.

Two non–mutually exclusive explanations seem most consistent with the obtained results. First, the C-terminal truncations that permit soluble, monomeric forms of the proteins to be produced may cause their destabilization, as could the presence of the C-terminal His tag. Second, the assembly of the proteins into their native helically packed complexes (Blocker et al. 2003) may result in much more stable structures. It should be noted that when full-length MxiH is generated in E. coli BL21(DE3) with the short His6 tag, it is sequestered into inclusion bodies. These inclusions can, however, be solubilized with 6 M urea, and the full-length MxiH-His6 purified by nickel-chelation chromatography. When the urea is then removed by dialysis, the portion of the protein remaining soluble can be subjected to gel filtration to give two forms of MxiH-His6. One is a very high molecular weight form that is composed of unfolded aggregates (based on CD spectroscopy and light scattering), and the other is fully folded, monomeric MxiH-His6. This monomeric form of MxiH also has a relatively low Tm (42.16° ± 1.6°C), indicating that the low Tm of MxiHΔ5 is an intrinsic property of the MxiH monomer. Also, unfolding of the full-length MxiH-His6 was not completely reversible, indicating that it is not a particularly attractive candidate for vaccine use. Unfortunately, the studies described here cannot yet be done using intact needles. Although we can purify small amounts of needles, they are prepared from intact bacteria with intact type III secretion apparatuses and are thus contaminated with other proteins. Furthermore, these needles, once sheared from the bacterial surface, appear to be somewhat labile and tend to depolymerize into smaller forms (including monomers) within a relatively short period of time at low concentrations. It is important to note, however, that work by Jouihri et al. (2003) shows that the presence of a His6 on MxiH does not negatively impact its ability to form fully functional needles in Shigella flexneri, suggesting that the His tag does not greatly impact these studies on MxiH structure and stability.

MxiH and PrgI both have their Phe and Trp peaks located toward either their N or C terminus. In contrast, the Tyr residues are somewhat more dispersed throughout the proteins’s sequences (Fig. 1). The second derivative UV absorbance studies, as well as the intrinsic fluorescence results, are consistent, with neither the Phe nor the Trp side chains significantly changing their environments when the structure is perturbed by either temperature (Kueltzo et al. 2003a) or urea (Eftink 1994). The changes that are seen are entirely explicable in terms of the intrinsic effects of temperature and urea on their spectral properties. When combined with the observation that the changes in environment of Tyr residues give evidence of a distinct transition (also supported by the DSC results, at least in the case of PrgI), this suggests a model in which this analog of the fiber protein contains a structural core with less stable N and C termini. This would be consistent with the N and C termini being involved in polymerization of MxiH and PrgI into needle structures.

CD and absorbance unfolding experiments yield similar results in terms of Tm values. This indicates that both methods detect global unfolding events in the proteins despite the fact that one selectively monitors secondary structure change, whereas the other monitors tertiary structure alterations. Thus, no evidence for molten globule- like intermediates is seen in this case.

The urea unfolding studies support the observation that these recombinant proteins are relatively unstable. Their intrinsic free energy of unfolding is well below what is commonly seen for a globular protein, although these values are not outside the values occasionally encountered for proteins of their size. Nevertheless, the ΔG values of <2 kcal/mol clearly classify them as unstable proteins. The resultant m-values can be correlated to the change in solvent-accessible surface area (ΔASA) as the proteins unfold (Fleming et al. 2005). For a protein of ~80 amino acid residues, the calculated ΔASA is ~6533 Å2, as obtained from Equation 9 below (Myers et al. 1995):

|

(9) |

where #res is the number of amino acid residues that take part in ΔASA. The m-values obtained from our urea-induced unfolding studies, however, predict from Equation 10 ΔASA values of 4109 Å2 and 3655 Å2 for MxiH and PrgI, respectively.

|

(10) |

The calculated ΔASA values summarized in Table 4 correspond to ~54 and 49 amino acid residues undergoing changes in the solvent-accessible surface area. This is compared to the 80 amino acid residues present in each of the proteins. Therefore, the relatively low m-values suggest that the proteins undergo significantly less change in solvent-accessible surface area than expected if complete unfolding were occurring or if the proteins are initially partially unfolded.

Table 4.

Calculated ΔASA values from the experimental m-value of the urea-induced unfolding at 10°C and 25°C

| 10°C | 25°C | |||||

| Protein | m-value | ΔASA | #res | m-value | ΔASA | #res |

| MxiH | 0.82 | 4109 | 54 | 0.69 | 2927 | 41 |

| PrgI | 0.77 | 3655 | 49 | 0.62 | 2291 | 34 |

#res represents the corresponding number of amino acid residues that are calculated to be exposed to the aqueous solvent upon unfolding. The ΔASA and #res are calculated using Equations 9 and 10, respectively.

Overall, these results indicate that N-terminal truncated versions of MxiH and PrgI provide a basis with which to begin to understand their role in the type III secretion apparatus of these important pathogens. We are currently working to enhance their stability through the use of secondary solutes to prepare them for high-resolution structural analysis and as candidates for components of stable vaccine preparations. Because these are the first biochemical studies of these proteins in vitro, it is not yet possible to confidently extrapolate the acquired data to the functional state of needles from Shigella and Salmonella. The secondary structure data, however, provide the first demonstration of the secondary structure content of these proteins, which appears to be in agreement with in silico predictions. Furthermore, these data strengthen arguments that MxiH (and thus PrgI) may resemble the polymerizing core of flagellin, since truncation of the C terminus allows the preparation of monomers for detailed biochemical analysis (Blocker et al. 2003). Therefore, it may be possible to now describe MxiH needle assembly and function in terms of packing (Blocker et al. 2003; Cordes et al. 2003, 2005; Kenjale et al. 2005).

Materials and methods

Preparation of MxiH and PrgI

The mxiH coding sequence was amplified from the Shigella virulence plasmid using PCR with a 5′ primer composed of GAGAGA, a XhoI restriction site, and the first 18 bases of mxiH, and a 3′ primer composed of GAGAGA, a BamHI restriction site, and the last 18 bases of mxiH. The resulting PCR product was digested with XhoI and BamHI and ligated into similarly digested pWPsf4 (Picking et al. 2005) to give pRKmxiH. The same procedure was used to generate pRKprgI. With pRKmxiH or pRKprgI as the template, a five-codon deletion at the 5′ end of each gene was introduced using reverse PCR with a 5′ primer composed of GAGAGA, a BamHI restriction site, and the preceding five terminal codons of mxiH or prgI, respectively. These PCR products were introduced into XhoI-/BamHI-digested pET21b to allow the production of MxiHΔ5 or PrgIΔ5 with a short His6 affinity tag at the C terminus.

The expression plasmids containing MxiHΔ5 or PrgIΔ5 were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) for high-level protein production (Picking et al. 1996). After induction of protein expression, the bacteria were harvested by centrifugation (8000g), resuspended in affinity binding buffer (20 mM Tris at pH 7.9, 0.5 M NaCl, 5 mM imidazole) and the bacteria disrupted by sonication. Insoluble debris was removed by centrifugation (20 min at 20,000g), and the soluble fraction was used for affinity purification via the C-terminal His tag by nickel-chelation chromatography as previously described (Picking et al. 1996) using 20 mM Tris (pH 7.9), 0.5 M NaCl, 1 M imidazole for elution. Purified proteins were dialyzed against 10 mM NaPO4 (pH 7.2), 150 mM NaCl (PBS) with a resultant purity >95% in all cases as determined by SDS-PAGE with Coomassie staining.

Turbidity and second derivative UV absorption analysis

Protein concentration determination and second derivative UV spectroscopy were performed with an Agilent 8453 UV-visible spectrophotometer (Kueltzo et al. 2003b). Protein concentrations were determined using an extinction coefficient of 9970 M−1cm−1 and 11,460 M−1cm−1 calculated at 280 nm for MxiH and PrgI, respectively (Gill and von Hippel 1989). In temperature perturbation studies, spectra were acquired over a temperature range of 10°–90°C at 2.5° intervals within a 1-cm path length cell with continuous stirring. Each spectrum was collected with an integration time of 25 sec after a 5-min equilibration time. Using Chemstation software (Agilent), spectra were converted to second derivatives using a nine-point data filter and a fifth-degree Savitzky-Golay polynomial, and subsequently fitted to a cubic function with 99-point data interpolation. The resolution of the final spectra was ±0.01 nm. Data were imported into Microcal Origin from which aromatic peak positions were determined and then plotted as a function of temperature (Kueltzo et al. 2003a) as shown in Figures 8 and 9. The tyrosine peaks in these figures (peaks 4 and 5) were analyzed as discussed below. The optical density of the solution was monitored at 350 nm with respect to temperature to monitor protein aggregation. Protein concentrations ranged from 50 to 80 μM and variations of concentration within this range did not influence thermal stability.

Circular dichroism spectroscopy

Far-UV CD spectra and thermal unfolding monitored at 222 nm were performed using a JASCO J720 spectropolarimeter (JASCO Inc.). Far-UV spectra were recorded from 260 to 190 nm at a scan rate of 15–20 nm/min using a 0.01-cm path length cell. Spectra were acquired in triplicate and averaged. Thermally induced unfolding curves were acquired using a 0.1-cm path length cell with a temperature ramping rate of 15°C/h. The change in secondary structure as a function of temperature was monitored at 222 nm. The protein concentration in all cases was between 20 and 50 μM. The unfolding transitions were analyzed as discussed below.

Urea-induced unfolding

Urea concentration was determined based on the refractive index of the solution using a Bausch & Lomb refractometer and calculated using the method of Pace (1986). Urea titration experiments were conducted with an Aviv spectrophotometer (model 202SF). The sample temperature was controlled by a Peltier device. The protein solution was contained in a quartz cuvette with a 1-cm path length. The titrant was dispensed into the cuvette from a syringe connected to a Hamilton automatic titrator with narrow diameter tubing. The syringe contained both the titrant and a protein concentration identical to that in the cuvette. The concentration of protein in both the syringe and cuvette was kept the same to maintain constant protein concentration throughout the experiment. In addition, a constant volume was maintained in the cuvette. This was accomplished by a program that commands the titrator to withdraw an equal volume of solution from the cuvette that is equal to that added in the next titration step. The urea-induced equilibrium unfolding transitions were monitored at 222 nm at 10°C and 25°C in PBS at pH 7.0. During our titration experiments, 5-min intervals were allowed between the times denaturant was added and the time data acquisition began. We found no change in the CD signal within this period. Moreover, this is a relatively small protein and therefore is not expected to have complex or slow folding/unfolding kinetics.

Differential scanning calorimetry

DSC experiments were performed with a VP-DSC (MicroCal Inc.) , using a heating rate of 1°C/min. About 0.2 mM protein solutions were used with the final protein dialysis buffer (PBS at pH 7.0) used as the reference solution. Before scanning the samples, numerous water and buffer thermograms were obtained to establish a thermal history for the instrument. Between measurement of samples, soap solution was thermally scanned followed by water and then buffer. For each of the proteins, rescanning was performed to measure reversibility. The buffer/buffer thermogram was subtracted from that of the buffer/protein, and the data were normalized for protein concentration before processing. The ΔH and ΔCp values were extracted by fitting to a two-state model using the fitting program supplied with the instrument.

Data analysis for equilibrium unfolding

The following equations describe a two-state unfolding between a native, N, and unfolded, U, state. The relationship between the equilibrium constant, Kun, for the unfolding process, the partition function, Q, and the mole fractions of the native, XN, and the unfolded, XU, protein is given in Equations 3 and 4.

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

The observed signal, S, in either the CD or the fluorescence experiments is given by Equation 5 below:

|

(5) |

where Si is the contribution of species i (with mole fraction Xi) to the signal, and PδSi/δ P is the dependence of the signal on perturbant, P, at temperature, T, in thermal-induced unfolding and urea concentration, [d], in urea-induced unfolding studies. A linear free energy relationship for the urea-induced unfolding transitions is assumed as shown in Equation 6.

|

(6) |

|

(7) |

where ΔG°0,un is the free energy of unfolding in the absence of perturbant, and m is the dependence of the free energy on denaturant concentration. Equations 1–6 were nonlinearly fit to the data using Igor Pro software. Thermally induced unfolding data were analyzed using the Gibbs-Hemholtz equation (Santoro and Bolen 1992) as shown in Equation 8, in combination with Equations 1–5.

|

(8) |

Fluorescence spectroscopy

Fluorescence emission spectra were acquired using a PTI QM-1 spectrofluorometer equipped with Felix software. Samples were excited at 295 nm (>95% Trp emission), and the emission spectra were collected between 305 nm and 400 nm at a scan rate of 30 nm/min using a 1-cm path length cell. In thermal unfolding studies, spectra were obtained at 2.5° intervals, beginning at 10°C up to 80°C. Each spectrum is an average of two scans. Depending upon protein concentration, slit widths were set between 4 nm and 6 nm. Additional fluorescence spectra were obtained using a JASCO FP-6500 spectrofluorometer (Jasco Inc.). Protein concentrations ranged from 50 μM to 80 μM, and within this range there was no concentration-dependent change in protein stability.

Acknowledgments

We are very thankful to Dr. Susan Pedigo at the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry of the University of Mississippi for the use of her spectropolarimeter for conducting the urea unfolding experiments, and Dr. Ariel Blocker for helpful advice on MxiH. This work was supported by NIH grants AI034428 and RR017708 (CoBRE Protein Structure and Function Program), and AI057927.

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.051733506.

References

- Allaoui, A., Sansonetti, P.J., and Parsot, C. 1992. MxiJ, a lipoprotein involved in secretion of Shigella Ipa invasions, is homologous to YscJ, a secretion factor of the Yersinia Yop proteins. J. Bacteriol. 174: 7661–7669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blocker, A., Jouihri, N., Larquet, E., Gounon, P., Ebel, F., Parsot, C., Sansonetti, P., and Allaoui, A. 2001. Structure and composition of the Shigella flexneri “needle complex,” a part of its type III secretion. Mol. Microbiol. 39: 652–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blocker, A., Komoriya, K., and Aizawa, S. 2003. Type III secretion systems and bacterial flagella: Insights into their function from structural similarities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100: 3027–3030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordes, F.S., Komoriya, K., Larquet, E., Yang, S., Egelman, E.H., Blocker, A., and Lea, S.M. 2003. Helical structure of the needle of the type III secretion system of Shigella flexneri. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 17103–17107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordes, F.S., Daniell, S., Kenjale, R., Saurya, S., Picking, W.L., Picking, W.D., Booy, F., Lea, S.M., and Blocker, A. 2005. Helical packing of needles from functionally altered Shigella type III secretions systems. J. Mol. Biol. 354: 206–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eftink, M.R. 1994. The use of fluorescence methods to monitor unfolding transitions in proteins. Biophys. J. 66: 482–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, P.J., Fitzkee, N.C., Mezei, M., Srinivasan, R., and Rose, G.D. 2005. A novel method reveals that solvent water favors polyproline II over β-strand conformation in peptides and unfolded proteins: Conditional hydrophobic accessible surface area (CHASA). Protein Sci. 14: 111–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill, S.C. and von Hippel, P.H. 1989. Calculation of protein extinction coefficients from amino acid sequence data. Anal. Biochem. 182: 319–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hueck, C.J. 1998. Type III protein secretion systems in bacterial pathogens of animals and plants. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62: 379–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouihri, N., Sory, M.P., Page, A.L., Gounon, P., Parsot, C., and Allaoui, A. 2003. MxiK and MxiN interact with the Spa47 ATPase and are required for transit of the needle components MxiH and MxiI, but not of Ipa proteins, through the type III secretion apparatus of Shigella flexneri. Mol. Microbiol. 49: 755–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenjale, R., Wilson, J., Zenk, S.F., Saurya, S., Picking, W.L., Picking, W.D., and Blocker, A. 2005. The needle component of the type III secretion of Shigella regulates the activity of the secretion apparatus. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 42929–42937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrough, T.G. and Miller, S.I. 2000. Contribution of Salmonella typhimurium type III secretion components to needle complex formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97: 11008–11013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubori, T., Sukhan, A., Aizawa, S.I., and Galan, J.E. 2000. Molecular characterization and assembly of the needle complex of the Salmonella typhimurium type III protein secretion system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97: 10225–10230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kueltzo, L.A., Ersoy, B., Ralston, J.P., and Midduagh, C.R. 2003a. Derivative absorbance spectroscopy and protein phase diagrams as tools for comprehensive protein characterization: A bGCSF case study. J. Pharm. Sci. 92: 1805–1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kueltzo, L.A., Osiecki, J., Barker, J., Picking, W.L., Ersoy, B., Picking, W.D., and Middaugh, C.R. 2003b. Structure–function analysis of invasion plasmid antigen C (IpaC) from Shigella flexneri. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 2792–2798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mota, L.J. and Cornelis, G.R. 2005. The bacterial injection kit: Type III secretion systems. Ann. Med. 37: 234–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers, J.K., Pace, C.N., and Scholtz, J.M. 1995. Denaturant m values and heat capacity changes: Relation to changes in accessible surface areas of protein unfolding. Protein Sci. 4: 2138–2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niyogi, S.K. 2005. Shigellosis. J. Microbiol. 42: 133–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace, C.N. 1986. Determination and analysis of urea and guanidine hydrochloride denaturation curves. Methods Enzymol. 131: 266–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picking, W.L., Mertz, J.A., Marquart, M.E., and Picking, W.D. 1996. Cloning, expression, and affinity purification of recombinant Shigella flexneri invasion plasmid antigens IpaB and IpaC. Protein Expr. Purif. 8: 401–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picking, W.L., Nishioka, H., Hearn, P.D., Baxter, M.A., Harrington, A.T., Blocker, A., and Picking, W.D. 2005. IpaD of Shigella flexneri is independently required for regulation of Ipa protein secretion and efficient insertion of IpaB and IpaC into host membranes. Infect. Immun. 73: 1432–1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro, M.M. and Bolen, D.W. 1992. A test of the linear extrapolation of unfolding free energy changes over an extended denaturant concentration range. Biochemistry 31: 4901–4907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamano, K., Aizawa, S., Katayama, E., Nonaka, T., Imajoh-Ohmi, S., Kuwae, A., Nagai, S., and Sasakawa, C. 2000. Supramolecular structure of the Shigella type III secretion machinery: The needle part is changeable in length and essential for delivery of effectors. EMBO J. 19: 3876–3887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmore, L. and Wallace, B.A. 2004. DICHROWEB, an online server for protein secondary structure analyses from circular dichroism spectroscopic data. Nucleic Acids Res. 32: W668–W673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonekura, K., Maki-Yonekura, S., and Namba, K. 2003. Complete atomic model of the bacterial flagellar filament by electron cryomicroscopy. Nature 424: 643–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]