Abstract

Calerythrin, a four-EF-hand calcium-binding protein from Saccharopolyspora erythraea, exists in an equilibrium between ordered and less ordered states with slow exchange kinetics when deprived of Ca2+ and at low temperatures, as observed by NMR. As the temperature is raised, signal dispersion in NMR spectra reduces, and intensity of near-UV CD bands decreases. Yet far-UV CD spectra indicate only a small decrease in the amount of secondary structure, and SAXS data show that no significant change occurs in the overall size and shape of the protein. Thus, at elevated temperatures, the equilibrium is shifted toward a state with characteristics of a molten globule. The fully structured state is reached by Ca2+-titration. Calcium first binds cooperatively to the C-terminal sites 3 and 4 and then to the N-terminal site 1, which is paired with an atypical, nonbinding site 2. EF-hand 2 still folds together with the C-terminal half of the protein, as deduced from the order of appearance of backbone amide cross peaks in the NMR spectra of partially Ca2+-saturated states.

Keywords: Calcium-binding protein, calerythrin, CD, EF-hand, molten globule, NMR, SAXS

Calerythrin is a 20-kDa Ca2+-binding protein isolated from the gram-positive bacterium Saccharopolyspora erythraea (Bylsma et al. 1992). The secondary structure and global fold of Ca2+-saturated calerythrin have recently been determined (Aitio et al. 1999). It is a compact protein consisting of four EF-hand motifs with characteristic helix–loop–helix patterns. Three of these are typical Ca2+-binding EF-hands, whereas site 2 is an atypical nonbinding site. In this site, two of the Ca2+-coordinating side-chains are exchanged to noncoordinating ones, causing the loss of affinity for Ca2+ ion. Calerythrin is homologous in sequence and fold (Aitio et al. 1999; Annila et al. 1999) to the sarcoplasmic Ca2+-binding proteins (SCPs; Hermann and Cox 1995), which are abundant in invertebrate muscle and neurons and function as intracellular Ca2+ buffers. Structures of Ca2+-saturated forms of Nereis diversicolor SCP (NSCP; Vijay-Cumar and Cook 1992) and Branchiostoma lanceolatum SCP (BSCP; Cook et al. 1993) have been elucidated by X-ray crystallography. Both have compact structures with a pronounced hydrophobic core composed of aromatic residues from both halves of the molecule, in contrast to calmodulin, which has two individually folded domains (Babu et al. 1988). Ca2+-binding loops are located on opposite sides of the SCP structure. Also in contrast to calmodulin, NSCP has been reported to be unstructured (Prêcheur et al. 1996) and later defined as a molten globule (Christova et al. 2000) when devoid of calcium. The molten globule state, which is a compact state containing a considerable amount of native-like secondary structure but a disordered tertiary structure, has been recognized as an intermediate in the folding process for a variety of globular proteins (Arai and Kuwajima 2000). Two other EF-hand proteins, parvalbumin (Williams et al. 1986; Sudhakar et al. 1995) and the C-terminal fragment of calcium vector protein (C-CaVP; Théret et al. 2000), have been reported to have characteristics of a molten globule in the Ca2+-free apo state. The A-state of α-lactalbumin, the paradigm of the molten globule state, can also be reached by removal of the bound calcium at low salt concentration (Kuwajima 1996). α-Lactalbumin is not an EF-hand protein, and the molten globule state is also observed in moderate concentration of a strong denaturant and at low pH, the common experimental conditions to produce the molten globule states of globular proteins.

The fluctuating nature of these partially folded states has hampered a comprehensive structural characterization. The lack of a unique structure obviously prevents crystallization, and detailed structural investigations by NMR are impaired because of poor spectral dispersion and/or line broadening resulting from conformational exchange. We present here the characterization of the Ca2+-deprived form of S. erythraea calerythrin by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR), optical spectroscopy, and small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS). Partially saturated states are assessed by inspection of heteronuclear 1H, 15N correlation NMR spectra. Our data imply that when deprived of its natural ligand, calerythrin adopts a molten globule–like state. Thus, the structural similarity found for Ca2+-saturated forms of calerythrin and NSCP extends to the apo forms of the two proteins.

Results

Apo calerythrin

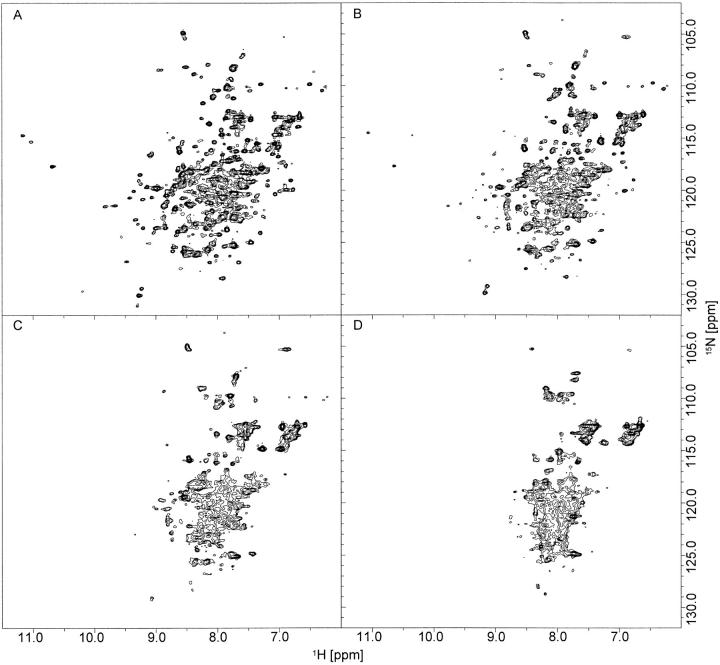

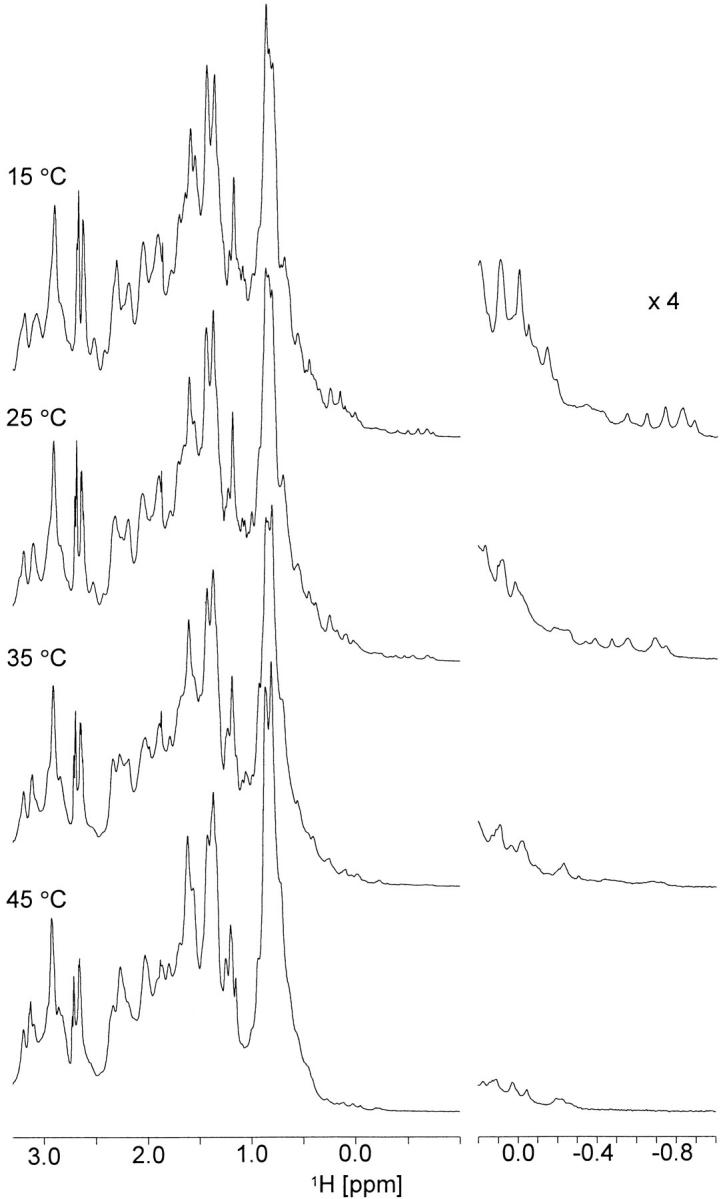

Heteronuclear 1H, 15N correlation (HSQC) NMR spectra of apo calerythrin (Fig. 1 ▶) measured at temperatures below 35°C show two sets of signals: one set of sharp peaks with good dispersion accompanied by broad signals in the middle region of the spectrum (Fig. 1A ▶). There are more peaks than expected for a 176-residue protein (>300 in the spectrum measured at 15°C), suggesting that there are two or more conformations in slow exchange. For a comparison, (Ca2+)3-calerythrin contains ∼200 1H-15N correlations at temperatures ranging from 15°C to 55°C, arising from both main- and side-chain amides. As the temperature is raised from 15°C, the intensities of all sharp well-shifted peaks, indicative of an ordered structure, gradually decrease without any noticeable broadening (Fig. 1B,C ▶). At 45°C, the temperature at which spectra for the structure determination of (Ca2+)3-calerythrin were acquired (Aitio et al. 1999), no sharp signals remain; only a set of broad lines with little dispersion can be seen (Fig. 1D ▶). The HN chemical shifts observed at 35°C (Fig. 1C ▶) and above are still more dispersed than those found for random coil (8.09–8.75 ppm; Wüthrich 1986). The 15N chemical shift dispersion is large also in denatured proteins because the shifts are influenced by residue type and large sequence-dependent effects (Braun et al. 1994). Lowering the temperature of the apo calerythrin sample does not influence the appearance of the 1H, 15N HSQC spectrum; at 5°C and 10°C, spectra are very similar to that acquired at 15°C. Also, the aliphatic region of 1H NMR spectra of apo calerythrin shows marked line broadening and reduction in signal dispersion at elevated temperatures; however, as in the 1H, 15N HSQC spectra, there is a set of sharp peaks at low temperatures, as well (Fig. 2 ▶).

Fig. 1.

1H,15N HSQC spectra of apo calerythrin. Apo calerythrin at (A) 15°C, (B) 25°C, (C) 35°C, and (D) 45°C. Spectra were acquired at a 1H frequency of 600 MHz.

Fig. 2.

Aliphatic region (from 3.3 to −1.0 ppm) of 1H spectra of apo calerythrin measured at different temperatures. Scaled (×4) expansions of the upfield methyl signals are shown on the right. Spectra were acquired at a 1H frequency of 800 MHz.

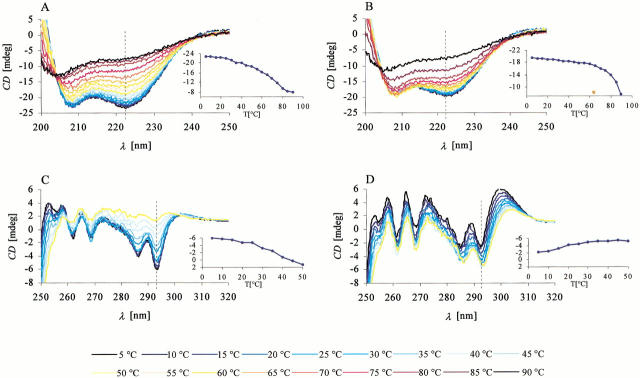

Far-UV CD spectra (Fig. 3A,B ▶) sensitive to protein secondary structure (Woody 1995) show that apo calerythrin displays a continuous decrease in helical content, whereas (Ca2+)3-calerythrin is subject to a cooperative thermal unfolding: at 60°C, ellipticity at 222 nm of apo calerythrin has decreased by 43%, whereas a 17% decrease is observed for (Ca2+)3-calerythrin and a sharp drop above 70°C (insets of Fig. 3A,B ▶). Although the NMR spectra of apo calerythrin exhibit major changes between 15° and 45°C, only a 24% decrease in ellipticity at 222 nm takes place.

Fig. 3.

CD spectra of calerythrin as a function of temperature. Far-UV spectra of (A) apo calerythrin and (B) (Ca2+)3-calerythrin show at low temperatures negative bands at 208 and 222 nm, typical of α-helical proteins. Insets in A and B show the ellipticity at 222 nm (dashed line) as function of temperature. Near-UV spectra of (C) apo calerythrin and (D) (Ca2+)3-calerythrin. Insets in C and D show the ellipticity at 293 nm (dashed line) as function of temperature.

Near-UV CD spectra of apo and (Ca2+)3-calerythrin (Fig. 3C,D ▶) are both composed of five bands, two from Trp residues at 286 and 293 nm and three from Phe residues at 255, 262, and 269 nm (Strickland 1974; Kahn 1979). For apo calerythrin (Fig. 3C ▶), all aromatic bands decrease in intensity when the sample is heated above 25°C, as can be seen most clearly in the Trp bands. At 50°C, the Trp bands can still be discerned but have diminished to approximately one-tenth of the intensity observed at 5°C. The intensities of the Phe bands decrease more slowly; approximately one-half and one-third of the intensities of the bands at 262 and 269 nm, respectively, are present at 50°C. In contrast to apo calerythrin, signal intensities of (Ca2+)3-calerythrin increase as the temperature is raised (Fig. 3D ▶).

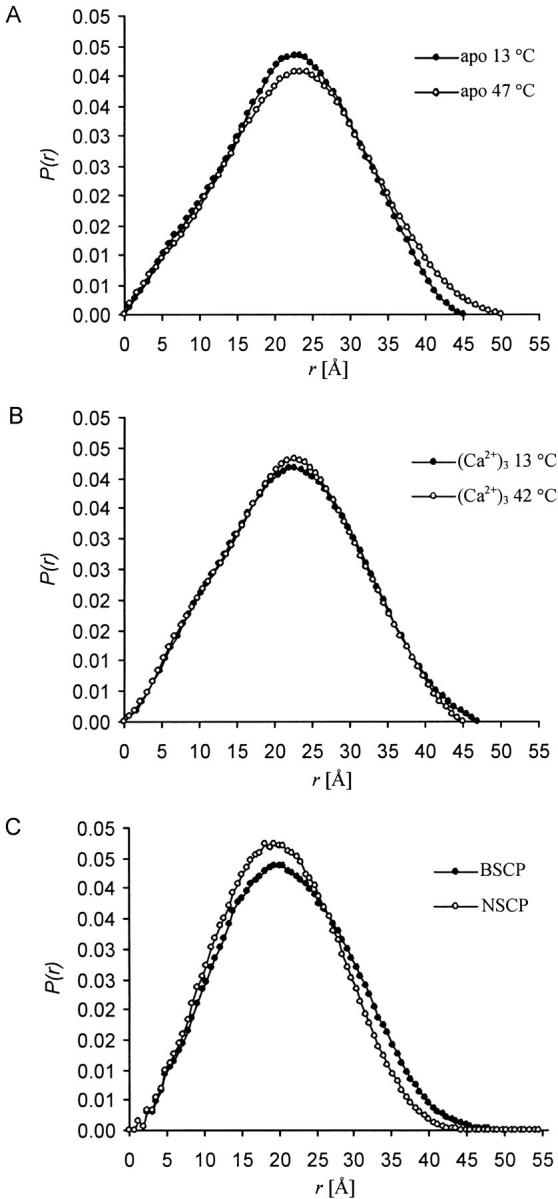

Small-angle X-ray scattering data were measured from apo and (Ca2+)3-calerythrin at two different temperatures. Similar distance distribution functions, P(r), are observed for apo protein at low and elevated temperature (Fig. 4A ▶). Only a small increase in the maximum dimension is found, from 45 Å to 50 Å. No significant change in the radius of gyration, Rg, was observed. For (Ca2+)3-calerythrin, there is no significant change either in the P(r) function or in Rg (Fig. 4B ▶). Apo and (Ca2+)3-calerythrin also have very similar dimensions; the apo form is only marginally larger. Both apo and (Ca2+)3-calerythrin are comparable in size with NSCP or BSCP, as deduced from the P(r) functions calculated from their crystal structures (Fig. 4C ▶).

Fig. 4.

Distance distribution functions, P(r), from small-angle X-ray scattering. (A) Apo calerythrin at 13°C (filled circles) and at 47°C (open circles). Only a very small change in the radius of gyration of apo calerythrin is observed, Rg is 16.9 Å at 13°C and 17.6 Å at 47°C. (B) (Ca2+)3-calerythrin at 13°C (filled circles) and at 42°C (open circles). Rg of (Ca2+)3-calerythrin has very similar values at both temperatures: 17.0 Å at 13°C and 16.8 Å at 42°C. The error in Rg is ± 0.5 Å. (C) Data calculated from the coordinates of Nereis diversicolor SCP (PDB ID 2scp, open circles) and Branchiostoma lanceolatum SCP (PDB ID 2sas, filled circles).

Ca2+-titration

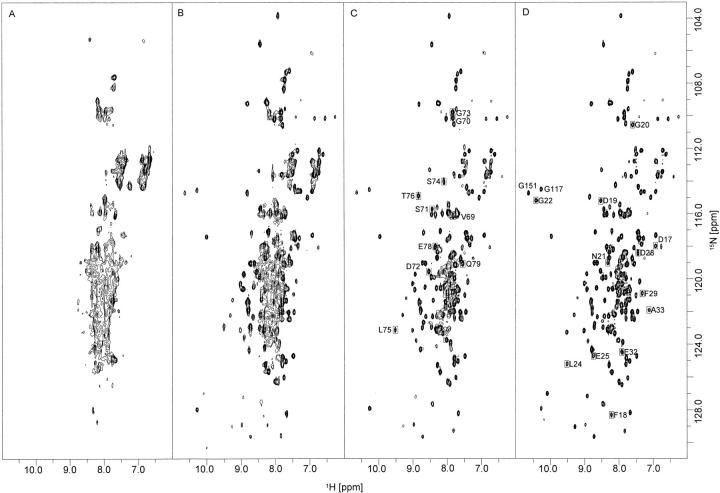

Ca2+-titration experiments were performed at 45°C (Fig. 5 ▶). Addition of the first equivalent of Ca2+ ion to calerythrin (Fig. 5B ▶) gives a spectrum that is approximately the sum of the apo spectrum (Fig. 5A ▶) and that of two equivalents of Ca2+ added (Fig. 5C ▶). Although broad lines, indicative of a still-remaining conformational exchange, are observed, frequencies of the well-resolved cross peaks are restored to the positions found for (Ca2+)3-calerythrin. Several peaks from the first Ca2+-binding loop and from the B helix following the loop are missing (D17-G22, L24-E25, D28-F29, E32-A33; shown with boxes in Fig. 5D ▶). Notably, signals from the second, atypical EF-hand are present already at this saturation state (marked with boxes in Fig. 5C ▶). Addition of a second equivalent of Ca2+ sharpens the signals (Fig. 5C ▶), but some broad features, not present in the spectrum of Ca2+-saturated calerythrin, still remain. No additional peaks appear at this level of saturation. All peaks are restored when excess of calcium (4 Ca2+: 1 calerythrin) is added (Fig. 5D ▶). Similar results were obtained from a titration at 27°C (not shown).

Fig. 5.

Ca2+-titration of apo calerythrin. (A) 1H,15N HSQC spectrum of apo calerythrin, as reproduced from Figure 1D ▶ for sake of clarity, 1H,15N HSQC spectra of (B) 1 : 1, (C) 1 : 2 and (D) 1 : 4 calerythrin : Ca2+. In C, boxes show cross peaks arising from residues in the atypical nonbinding loop and in (D) boxes show cross peaks arising from the first unpaired EF-hand loop appearing only when protein is fully Ca2+-saturated. Low-field shifted G22, G117, and G151 are the glycines at position 6 in the Ca2+-binding loops 1, 3, and 4, respectively. Spectra B–D were recorded at 45°C at a 500 MHz 1H frequency.

Discussion

To differentiate between structured, molten globule, and denatured states, we employed several methods. The SAXS data show that apo calerythrin remains remarkably compact even at elevated temperatures. However, there is no fixed tertiary structure. Loss of signal intensity in near-UV CD is associated with loss of chiral environment of the absorbing side-chain (Strickland 1974; Kahn 1979). The Trp bands that originate from both calerythrin's tryptophan side-chains (Trp16 and Trp127) are amenable to a detailed interpretation. These two tryptophans correspond to Ile15 and Phe119 of NSCP, assuming that the amino acid sequences (identity of 27%) are aligned in such a way that the short β-strands of the Ca2+-binding loops are matched. Comparison of experimental residual dipolar couplings and those calculated from the crystal structure of NSCP has shown that this alignment implies similar folds for (Ca2+)3-calerythrin and NSCP (Aitio et al. 1999; Annila et al. 1999). Both Ile15 and Phe119 in Ca2+-saturated NSCP are in the hydrophobic core of the molecule. On the basis of this structural similarity, there appears to be an unordered hydrophobic core in apo calerythrin at elevated temperatures. The secondary structures are, however, present to a significant degree, as the far-UV data show considerable amounts of helical structures. Apparently, the secondary structures possess a sufficient dynamic character to average the magnetic environment of backbone amides; however, this averaging is not extremely fast because the NMR signals are broadened in the HSQC spectra. NMR spectra of molten globule intermediates have been reported to resemble those of unfolded proteins but to differ by having some dispersion (Baum et al. 1989; Matthews et al. 2000). Reduction of dispersion and broad lines in the aliphatic region of the 1H spectra can be interpreted as movement of secondary structures relative to each other. NMR signals are subject to significant line broadening when the exchange between two or more conformations with considerably different chemical shifts occurs at a rate comparable to the chemical shift difference. Fluctuation of tertiary structure but persisting secondary structure and compactness are all characteristics of a molten globule (Arai and Kuwajima 2000). At low temperatures, equilibrium between molten globule-like conformers and a structurally well-defined conformer exists (Fig. 1A ▶). The low-temperature conformer that is more structured appears to have some spectral characteristics similar to Ca2+-free skeletal troponin C, a member of the calmodulin family; for instance, well-shifted amide proton resonances, particularly from the Gly residues at position 6 in the Ca2+-binding loops (Gagné et al. 1998). At higher temperatures, the equilibrium is shifted in favor of the molten globule.

It is possible that other solvent properties not used in this study may stabilize the more well-defined apo form observed at lower temperatures. Several examples where ionic strength affects the stability of a particular state have been reported; for example, at higher ionic strength the melting temperature of the molten globule state of apo NSCP raises (Christova et al. 2000) and the A-state of apo-α-lactalbumin stabilizes to the native structure (Kuwajima 1989).

Previous Ca2+-binding studies of calerythrin (Bylsma et al. 1992) have shown the presence of three high-affinity sites; one pair of cooperative sites, presumably sites 3 and 4, and one isolated site, site 1. This is in very good agreement with our NMR data, which in fact, prove that the C-terminal Ca2+-binding sites are filled first and that the third site, site 1, starts to be filled only when the other two are almost fully saturated. This is most easily monitored from low-field shifted glycines at position 6 in the Ca2+-binding loops (Gly22, Gly117, and Gly151 in loops 1, 3, and 4, respectively). It is also interesting to note that the nonbinding site, site 2, appears to fold together with sites 3 and 4 and not, as expected, with site 1. This can be concluded from the fact that most of the signals from this part of the protein have already, at the addition of two equivalents of Ca2+, obtained the same shifts as in the fully Ca2+-saturated protein (Fig. 5B ▶). The observation that, for example, Gly117 and Gly151, after the first Ca2+ addition, already appear at the same position as in the fully Ca2+-saturated protein is most easily interpreted as having been caused by a positive cooperative binding to sites 3 and 4. Prêcheur et al. (1996) have reported that the proton NMR spectra of NSCP showed a marked improvement in spectral distribution and resolution after the binding of the first Ca2+ ion and only minor changes thereafter. Their interpretation of the data was that the first Ca2+ ion binds to site 1 and that this made the whole protein fold into a form that is close to native (Ca2+)3-form. This is in contrast to our finding that the first Ca2+ ions bind to the C-terminal half of calerythrin and that EF-hand 1 is folded after binding of a third Ca2+ ion. This is an interesting difference between two otherwise very similar proteins.

Structures of several EF-hand Ca2+-binding proteins have been determined both in Ca2+-saturated and Ca2+-free forms. The degree of conformational change they undergo on Ca2+ binding extends from minor changes observed, for example, for members of the S100 protein family (Sastry et al. 1998) to large conformational changes invoking a reorientation of helices found in, for example, calmodulin (Zhang et al. 1995) and skeletal troponin C (Gagné et al. 1995). According to this degree of conformational change, EF-hand proteins have been commonly divided in two groups (Ikura 1996). The sensors, including calmodulin, are involved in transducing Ca2+ signals. The buffers, for example, calbindin D9k, are involved in Ca2+ uptake, transport, and buffering. In contrast to these proteins, a few members of the EF-hand protein family, namely, parvalbumin, NSCP, and very recently C-CaVP, have been reported to have a highly structured Ca2+-saturated state but lack a stable apo form. Ca2+-free cod parvalbumin has been shown to retain ∼50% of the helical content at 5°C compared to that of the Ca2+-saturated form, as deduced from far-UV spectra (Laberge et al. 1997). Apo cod parvalbumin also shows short Trp phosphorescence lifetime and blue shift in fluorescence (Sudhakar et al. 1995), both indicative of loss of tertiary structure. The apo form of rat muscle β-parvalbumin has been shown to exist in two conformations at 25°C, and lose its tertiary structure on heating, as evidenced by broad signals in aromatic and aliphatic regions of 1H NMR spectra and loss of intensity in near-UV spectra (Williams et al. 1986). NSCP has been reported to be unstructured in the apo state (Prêcheur et al. 1996) and was later deduced to be a molten globule (Christova et al. 2000). 1H NMR spectra of apo and partially saturated states of NSCP at 15°C are very similar to those of calerythrin at 45°C. For apo NSCP, the intensity at 222 nm in far-UV CD was observed to be 16% smaller than that of Ca2+-saturated NSCP. Ca2+-binding studies of tryptic fragments of NSCP suggest that the C-terminal domain is mostly responsible for changes observed on binding, as the N-terminal domain appears to be more structured in its apo form (Durussel et al. 1993). The apo form of C-CaVP shows a twofold lower α-helical content than the Ca2+-saturated form, a considerably lower melting temperature, but a cooperative unfolding indicating a relatively compact fold. 1D and 2D NMR spectra of C-CaVP show poorly dispersed resonances, and binding of one equivalent of Ca2+ leads to a state with a highly fluctuating Ca2+-free site and an ordered Ca2+-bound site (Théret et al. 2000).

It would be interesting to understand why one EF-hand protein is stable without Ca2+ while another is not. The tertiary structure of calmodulin or troponin C, for example, is stabilized by hydrophobic interactions within a domain, and hydrogen bonds in the short β-sheet between the two EF-hands contribute as well. In these sensor proteins, direct interactions between the domains are few. In this sense, there is no distinct quaternary structure. Ligands that usually bind to Ca2+-saturated forms may bridge from one domain to the other and create a rigid and well-defined quaternary structure. Aequorin and recoverin are examples of multidomain EF-hand sensor proteins that have a compact array of four EF-hands and, yet, structured apo states. Aequorin (Head et al. 2000) is a four-EF-hand photoprotein from jellyfish, homologous to NSCP and calerythrin. Its apo conformation is similar to those of Ca2+-bound SCPs. Aequorin has a binding pocket in the center of the protein, where a chromophoric coelenterazine group is bound. Coelenterazine in aequorin might bring additional stability to the apo state, as each of the EF-hands participates in making the hydrophobic binding pocket. Recoverin, which also contains four EF-hands, functions as a Ca2+ sensor in rod cells of retina (Flaherty et al. 1993; Tanaka et al. 1995; Ames et al. 1997). It is analogous to aequorin in the way that in the apo state, a hydrophobic group, which is an N-terminally bound myristoyl group, is buried deep in the hydrophobic core. Just like coelenterazine in aequorin, the myristoyl group might bring a stabilizing effect to the structure. These factors may have a profound effect on Ca2+-dependent stabilization of the global fold. Because apo NSCP has been found to be a molten globule (Christova et al. 2000) and we find that apo calerythrin exists in an equilibrium between a molten globule and a structured form, we are curious if in general, a multidomain buffer EF-hand protein is more prone to lack a definite tertiary structure in the ligand-free apo state than are the sensor EF-hand proteins.

However, as the recent structural work on C-CaVP shows, sensor proteins might also undergo similar extensive structural rearrangements on Ca2+ binding (Théret et al. 2000). At present, too few apo structures have been characterized to judge if there are any general principles. Once more apo states of EF-hand proteins are characterized, there will be better possibilities to understand if molten globule–like states have a functional role in the biology of Ca2+-binding proteins.

Materials and methods

Sample preparation

The details of the protein production and purification have been described elsewhere (Aitio et al. 1999). Ca2+ was removed from the Ca2+-saturated protein by dissolving the lyophilized protein in 2 mL 0.1 M EDTA at pH 8 and desalting on a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75 column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) equilibrated in H2O. Before the protein was applied to the column, it was flushed with 12 mL of Chelex 100-treated saturated NaCl. The recovered protein was lyophilized, and the purification process was repeated. The use of glassware was avoided.

Small-angle X-ray scattering

SAXS experiments were made by using a fine-focus Cu X-ray tube in the line-focusing mode. CuKα radiation was selected by using a Ni-filter and a totally reflecting glass block monochromator (Huber small-angle chamber 701). The intensity curves were measured using a linear one-dimensional position-sensitive proportional counter (MBraun OED50M). For apo calerythrin, the distance between the sample and the detector was 158 mm, and the k-range was from 0.032 to 0.68 Å−1. For (Ca2+)3-calerythrin, the distance between the sample and the detector was 153 mm and the k-range was from 0.035 to 0.68 Å−1. The magnitude of the scattering vector k is defined as k = 4πsinθ/λ, where λ is the wavelength and 2θ is the scattering angle. The instrumental function had a full width at half maximum of 0.35 Å−1 and 0.005 Å−1 in vertical and horizontal directions, respectively. A modified Linkam TP 93 microscope hot stage was used for heating the sample.

Concentration of the apo calerythrin sample was 1 mM, dissolved in 5 mM EGTA, 5 mM DTT, and 2 mM NaN3 in H2O at pH 6.0. Data were measured at 13°C and 47°C. Concentration of (Ca2+)3-calerythrin was 2 mM, dissolved in 8 mM CaCl2, 10 mM DTT, and 2mM NaN3 in H2O at pH 6.0. Data were measured at 13°C and 42°C. The protein solution was placed between thin polyimide foils. Measuring times between 3 and 5 h were used. The background scattering caused by solvent was measured separately and subtracted from the intensity curves. The distance distribution function was calculated by the indirect Fourier transform method using the Program Gnom (Svergun et al. 1988).

Circular dichroism

CD spectra were measured with a JASCO J-720 instrument. Far-UV spectra were measured using a 0.1-cm path-length cell for the 190–250 nm region. Step size was 0.2 nm, scan speed 20 nm/min, response 1 sec, band width 2 nm, and number of accumulations one per spectrum. The temperature was raised from 5°C to 90°C in steps of 5°C. The apo calerythrin sample had a concentration of 10 μM in H2O with 50 μM EGTA and 50 μM DTT at pH 6.0. In the (Ca2+)3-calerythrin sample, EGTA was replaced by 40 μM CaCl2. Near-UV spectra were measured using a 0.5-cm path-length cell for the 250–320 nm region. Step size was 0.2 nm, scan speed 50 nm/min, response 1 sec, band width 2 nm, and number of accumulations five per spectrum. The temperature was raised from 5°C to 50°C in steps of 5°C. The concentration of apo calerythrin was 300 μM in H2O with 1.3 mM EGTA and 1.3 mM DTT at pH 6.0. In the (Ca2+)3-calerythrin sample, EGTA was replaced by 1.2 mM CaCl2. Approximate protein concentrations are based on weighed values.

NMR

1H, 15N HSQC spectra of apo calerythrin were acquired with a sample that contained 0.3 mM apo calerythrin dissolved in 1.3 mM EGTA, 1.3 mM DTT, and 2 mM NaN3 in 95% H2O/5% D2O at pH 6.0. Spectra were acquired with a Varian Unity Inova 600-MHz spectrometer, with 1024(1H)×128(15N) points and 32 scans per increment. 1H spectra were measured from the same sample with a Varian Unity Inova 800-MHz spectrometer, using 2048 scans and presaturation of water.

The Ca2+ titration was performed with a sample that initially contained 1.1 mM apo calerythrin dissolved in 5 mM DTT and 2 mM NaN3 in 95% H2O/5% D2O at pH 6.0. Ca2+ was added in 2.5 μL aliquots to protein : Ca2+ ratios of 1 : 1, 1 : 2, 1 : 4. 1H-15N HSQC spectra were acquired at each titration point at 27°C and 45°C. 1024(1H)×128(15N) points were acquired with 16 or 24 scans with a Varian Unity 500-MHz spectrometer.

Acknowledgments

We thank Perttu Permi for useful discussions. The Viikki Graduate School in Biosciences is acknowledged. This work was supported by the Academy of Finland.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked ``advertisement'' in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Abbreviations

BSCP, sarcoplasmic calcium-binding protein from Branchiostoma lanceolatum

C-CaVP, C-terminal fragment of calcium vector protein

CD, circular dichroism

DTT, dithiothreitol

EDTA, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

EGTA, ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N`,N`-tetraacetic acid

HSQC, heteronuclear single quantum coherence

NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance

NSCP, sarcoplasmic calcium-binding protein from Nereis diversicolor

SAXS, small-angle X-ray scattering

SCP, sarcoplasmic calcium-binding protein.

Article and publication are at www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.31201.

References

- Aitio, H., Annila, A., Heikkinen, S., Thulin, E., Drakenberg, T., and Kilpeläinen, I. 1999. NMR assignments, secondary structure and global fold of calerythrin, an EF-hand protein from S. erythraea. Protein Sci. 8 2580–2588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames, J.B., Ishima, R., Tanaka, T., Gordon, J.I., Stryer, L., and Ikura, M. 1997. Molecular mechanics of calcium-myristoyl switches. Nature 389 198–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annila, A., Aitio, H., Thulin, E., and Drakenberg, T. 1999. Recognition of protein folds via dipolar couplings. J. Biomol. NMR 14 223–230. [Google Scholar]

- Arai, M. and Kuwajima, K. 2000. Role of the molten globule state in protein folding. Adv. Prot. Chem. 53 209–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu, Y.S., Bugg, C.E., and Cook, W.J. 1988. Structure of calmodulin refined at 2.2 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 204 191–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum, J., Dobson, C.M., Evans, P.A., and Hanley, C. 1989. Characterization of a partly folded protein by NMR methods: Studies on the molten globule state of guinea pig α-lactalbumin. Biochemistry 28 7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, D., Wider, G., and Wüthrich, K. 1994. Sequence-corrected 15N ``random-coil'' chemical shifts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116 8466–8469. [Google Scholar]

- Bylsma, N., Drakenberg, T., Andersson, I., Leadlay, P.F., and Forsén, S. 1992. Prokaryotic calcium-binding protein of the calmodulin superfamily: Calcium binding to a Saccharopolyspora erythraea 20 kDa protein. FEBS Lett. 299 44–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christova, P., Cox, J.A., and Craescu, C.T. 2000. Ion-induced conformational and stability changes in Nereis sarcoplasmic calcium binding protein: Evidence that the APO state is a molten globule. Proteins 40 177–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook, W.J., Jeffrey, L.C., Cox, J.A., and Vijay-Kumar, S. 1993. Structure of sarcoplasmic calcium-binding protein from amphioxus refined at 2.4 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 229 461–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durussel, I., Luan-Rilliet, Y., Petrova, T., Takagi, T., and Cox, J.A. 1993. Cation binding and conformation of tryptic fragments of Nereis sarcoplasmic calcium-binding protein: Calcium-induced homo- and heterodimerization. Biochemistry 32 2394–2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty, K.M., Zozulya, S., Stryer, L., and McKay, D.B. 1993. Three-dimensional structure of recoverin, a calcium sensor in vision. Cell 75 709–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagné, S.M., Tsuda, S., Li, M.X., Smillie, L.B., and Sykes, B.D. 1995. Structures of the troponin C regulatory domains in the apo and calcium-saturated states. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2 784–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagné, S.M., Tsuda, S., Spyracopoulos L., Kay, L.E., and Sykes, B.D. 1998. Backbone and methyl dynamics of the regulatory domain of troponin C: Anisotropic rotational diffusion and contribution of conformational entropy to calcium affinity. J. Mol. Biol. 278 667–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head, J.F., Inouye, S., Teranishi, K., and Shimomura, O. 2000. The crystal structure of the photoprotein aequorin at 2.3 Å resolution. Nature 405 372–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann, A. and Cox, J.A. 1995. Sarcoplasmic calcium-binding protein. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 111B 337–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikura, M. 1996. Calcium binding and conformational response in EF-hand proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 21 14–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, P.C. 1979. The interpretation of near-ultraviolet circular dichroism. Methods Enzymol. 61 339–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwajima, K. 1989. The molten globule state as a clue for understanding the folding and cooperativity of globular-protein structure. Proteins 6 87–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1996. The molten globule state of α-lactalbumin. FASEB J. 10 102–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laberge, M., Wright, W.W., Sudhakar, K., Liebman, P.A., and Vanderkooi, J.M. 1997. Conformational effects of calcium release from parvalbumin: Comparison of computational simulations with spectroscopic investigations. Biochemistry 36 5363–5371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, J.M., Norton, R.S., Hammacher, A., and Simpson, R.J. 2000. The single mutation Phe173→Ala induces a molten globule–like state in murine interleukin-6. Biochemistry 39 1942–1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prêcheur, B., Cox, J.A., Petrova, T., Mispelter, J., and Craescu, T. 1996. Nereis sarcoplasmic Ca2+-binding protein has a highly unstructured apo state which is switched to the native state upon binding of the first Ca2+ ion. FEBS Lett. 395 89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastry, M., Ketchem, R.R., Crescenzi, O., Weber, C., Lubienski, M.J., Hidaka, H., and Chazin, W.J. 1998. The three-dimensional structure of Ca2+-bound calcyclin: Implications for Ca2+-signal transduction by S100 proteins. Structure 6 223–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland, E.H. 1974. Aromatic contribution to circular dichroism spectra of proteins. CRC Crit. Rev. Biochem. 2 113–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudhakar, K., Phillips, C.M., Owen, C.S., and Vanderkooi, J.M. 1995. Dynamics of parvalbumin studied by fluorescence emission and triplet absorption spectroscopy of tryptophan. Biochemistry 34 1355–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svergun, D.I., Semenyuk, A.V., and Feigin, L.A. 1988. Small-angle-scattering-data treatment by the regularization method. Acta Crystallogr. A44 244–250. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, T., Ames, J.B., Harvey, T.S., Stryer, L., and Ikura, M. 1995. Sequestration of the membrane-targeting myristoyl group of recoverin in the calcium-free state. Nature 376 444–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Théret, I., Baladi, S., Cox, J.A., Sakamoto, H., and Craescu, C.T. 2000. Sequential calcium binding to the regulatory domain of calcium vector protein reveals functional asymmetry and a novel mode of structural rearrangement. Biochemistry 39 7920–7926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijay-Kumar, S. and Cook, W.J. 1992. Structure of sarcoplasmic calcium-binding protein from Nereis diversicolor refined at 2.0 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 224 413–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, T.C., Corson, D.C., Oikawa, K., McCubbin, W.D., Kay, C.M., and Sykes, B.D. 1986. 1H NMR spectroscopic studies of calcium-binding proteins. 3. Solution conformations of rat apo-α-parvalbumin and metal-bound rat α-parvalbumin. Biochemistry 25 1835–1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woody, R.W. 1995. Circular dichroism. Methods Enzymol. 246 34–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wüthrich, K. 1986. NMR of proteins and nucleic acids. Wiley, New York.

- Zhang, M., Tanaka, T., and Ikura, M. 1995. Calcium-induced conformational transition revealed by the solution structure of apo calmodulin. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2 758–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]