Abstract

The effects of chain cleavage and circular permutation on the structure, stability, and activity of dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) from Escherichia coli were investigated by various spectroscopic and biochemical methods. Cleavage of the backbone after position 86 resulted in two fragments, {1–86} and {87–159}, each of which are poorly structured and enzymatically inactive. When combined in a 1 : 1 molar ratio, however, the fragments formed a high-affinity (Ka = 2.6 × 107 M−1) complex that displays a weakly cooperative urea-induced unfolding transition at micromolar concentrations. The retention of about 15% of the enzymatic activity of full-length DHFR is surprising, considering that the secondary structure in the complex is substantially reduced from its wild-type counterpart. In contrast, a circularly permuted form with its N-terminus at position 86 has similar overall stability to full-length DHFR, about 50% of its activity, substantial secondary structure, altered side-chain packing in the adenosine binding domain, and unfolds via an equilibrium intermediate not observed in the wild-type protein. After addition of ligand or the tight-binding inhibitor methotrexate, both the fragment complex and the circular permutant adopt more native-like secondary and tertiary structures. These results show that changes in the backbone connectivity can produce alternatively folded forms and highlight the importance of protein-ligand interactions in stabilizing the active site architecture of DHFR.

Keywords: Fluorescence spectroscopy, circular dichroism spectroscopy, urea denaturation, thermal denaturation, multi-state unfolding

Implicit in the Anfinsen hypothesis, that the amino acid sequence of a protein determines its three-dimensional fold (Anfinsen et al. 1961), is the role of chain connectivity in the complex conformational transition. Changes in connectivity could alter the stability of a localized element of structure, thereby favoring an alternative conformation. Thus, it is perhaps surprising that cleaving or permuting the sequences of a number of globular proteins leaves the folded state nearly unchanged from that adopted by the wild-type protein. For example, the structures of noncovalent complexes formed between pairs of fragments from barnase (Kippen and Fersht 1995), tuna cytochrome c (Yokota et al. 1998), and thioredoxin (Chaffotte et al. 1997) resemble their corresponding full-length forms and retain a significant fraction of the biological activity of the full-length protein. Similarly, circular permutants, proteins in which an internal peptide bond is broken and a peptide linker connects the natural N- and C-termini, tend to retain their structure (Viguera et al. 1996; Ay et al. 1998), activity (Ritco-Vonsovici et al. 1995; Ay et al. 1998; Feng et al. 1999), oligomeric state (Vignais et al. 1995; Wieligmann et al. 1998), stability (Zhang et al. 1993; Vignais et al. 1995), and in some cases even their kinetic and equilibrium (Otzen and Fersht 1998) folding properties. Therefore, the folding reactions for a number of proteins are sufficiently robust that variations in connectivity do not alter the outcomes.

To test the generality of these observations, dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR1) from Escherichia coli was subjected to cleavage and permutation. This small (159 amino acids; MW = 18 kD) monomeric α/β protein contains a discontinuous loop domain and an adenosine-binding domain (ABD).

An early crystal structure of the apoenzyme led to the assignment of the loop domain to residues {1–37} and {89–159} (Bystroff and Kraut 1991) and the intervening ABD to residues {38–88}. A recent examination of a series of DHFR/ligand complexes has led to an alternative assignment, namely, {1–37} and {107–159} for the loop domain and {38–106} for the ABD (Sawaya and Kraut 1997).

Pertinent to the connectivity issue, DHFR has several properties that make it an interesting candidate for a test of the relationship between sequence and structure. First, kinetic folding studies (Touchette et al. 1986; Jennings et al. 1993) have revealed that DHFR refolds through parallel channels that lead to multiple intermediate and native conformers. The two major native conformers differ in their ability to bind cofactor (Jennings et al. 1993) and have distinct spectroscopic features (Falzone et al. 1991; Ionescu et al. 2000). Second, the thermal unfolding reaction of DHFR involves a stable, partially folded form (Luo et al. 1995; Ohmae et al. 1996; Ionescu et al. 2000). Third, a crystallographic study (Sawaya and Kraut 1997) revealed that DHFR undergoes significant changes in the relative positions of the two domains during its catalytic cycle. Finally, an earlier fragmentation study on DHFR (Gegg et al. 1997) identified a cooperatively folded fragment, {37–159}, that possesses nonnative secondary and tertiary structural features. The existence of these alternative conformations for DHFR offers a more stringent test of the role of connectivity on structure than was possible for several of the above examples.

Results

Relevant structural features of DHFR and selection of cleavage site

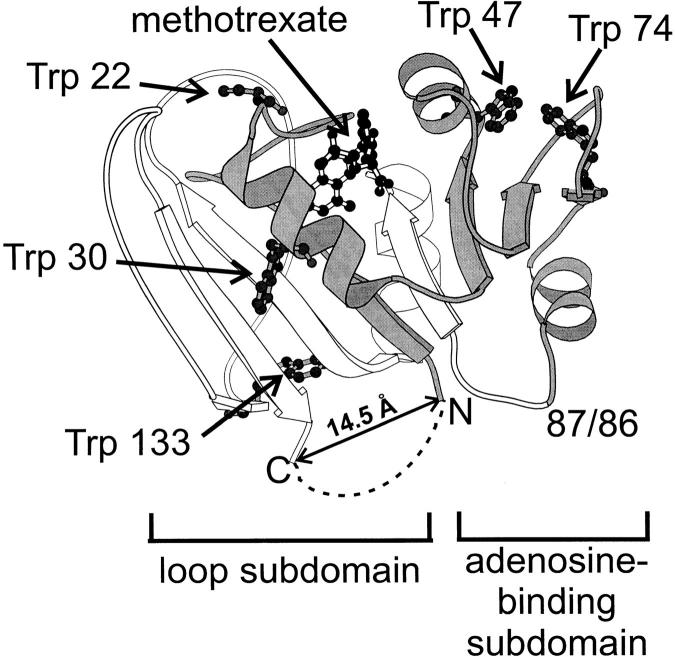

The three-dimensional structure of E. coli dihydrofolate reductase is shown in Figure 1 ▶. The eight mostly parallel beta strands form a sheet that defines the hydrophobic core of the protein, whereas the four amphipathic helices dock on its surface. Both the loop and adenosine-binding domains have hydrogen-bonding and van der Waals contacts with the ligand, dihydrofolate, and/or cofactor, NADPH. There are five tryptophans in the full-length protein that act as intrinsic fluorescence probes for the folding and association reactions: W22, W30, W47, W74, and W133. It is noteworthy that the loop domain is comprised of discontinuous segments at the N- and C-termini of DHFR.

Fig. 1.

Ribbon diagram of E. coli dihydrofolate reductase. The residues corresponding to fragment {1–86} are shown in gray and fragment {87–159} is in white. The ligand methotrexate and the sidechains of the tryptophans are shown in ball-and-stick notation. The loop and adenosine-binding subdomains are indicated. A dashed line is drawn to represent the penta-glycine linker connecting the natural N- and C-termini in the permutant cpG86. This figure was prepared using Molscript (Kraulis 1991), based on PDB file 1rg7.

Although an X-ray crystal structure provides essential information on the three-dimensional organization of a protein, it is nonetheless a static representation. For E. coli DHFR, a series of structures from the Kraut laboratory (Sawaya and Kraut 1997) have made it apparent that the catalytic cycle involves the relative displacement of the two domains. Because neither domain acts as an autonomous folding unit (Gegg et al. 1997), this set of structures implies that the structural integrity of each domain depends on the presence of the other domain and ligands.

To test the role of chain connectivity on the structure and stability of DHFR, the cleavage site for the permutation was chosen both to make the ABD discontinuous and to match as closely as possible the cleavage site that produces a pair of unstructured fragments, {1–86} and {87–159}. These fragments also have the advantage that they are soluble in monomeric form at concentrations that permit spectroscopic analysis (Gegg et al. 1997). Because the N- and C-termini of DHFR are relatively close in space (Cα to Cα distance of 14.5 Å) (Fig. 1 ▶) (Bystroff and Kraut 1991), it was possible to construct a circular permutant of DHFR by connecting the termini with a pentaglycine linker and creating new termini within the ABD and adjacent to the cleavage site for the fragments (Iwakura and Nakamura 1998; Iwakura 2000). The circular permutant beginning at Gly 86 (cpG86) was selected instead of the permutant starting at residue 87 (cpD87) because the low stability of cpD87 (Iwakura et al. 2000) prevented extensive characterization. However, the two permutants have nearly identical far-UV CD spectra (data not shown), indicating structural similarity. Selecting a cleavage site distal from the active site makes it possible to use enzyme activity as a measure of native-like structure. The cysteine-free variant, AS-DHFR, which has stability and activity similar to wild-type protein (Iwakura et al. 1995), was used as the full-length control because it is the parent species from which the fragments were derived.

Additionally, AS-DHFR serves as a good control for thermal denaturation studies of cpG86 because it is resistant to oxidative damage at high temperatures (Iwakura et al. 1995; Iwakura and Honda 1996).

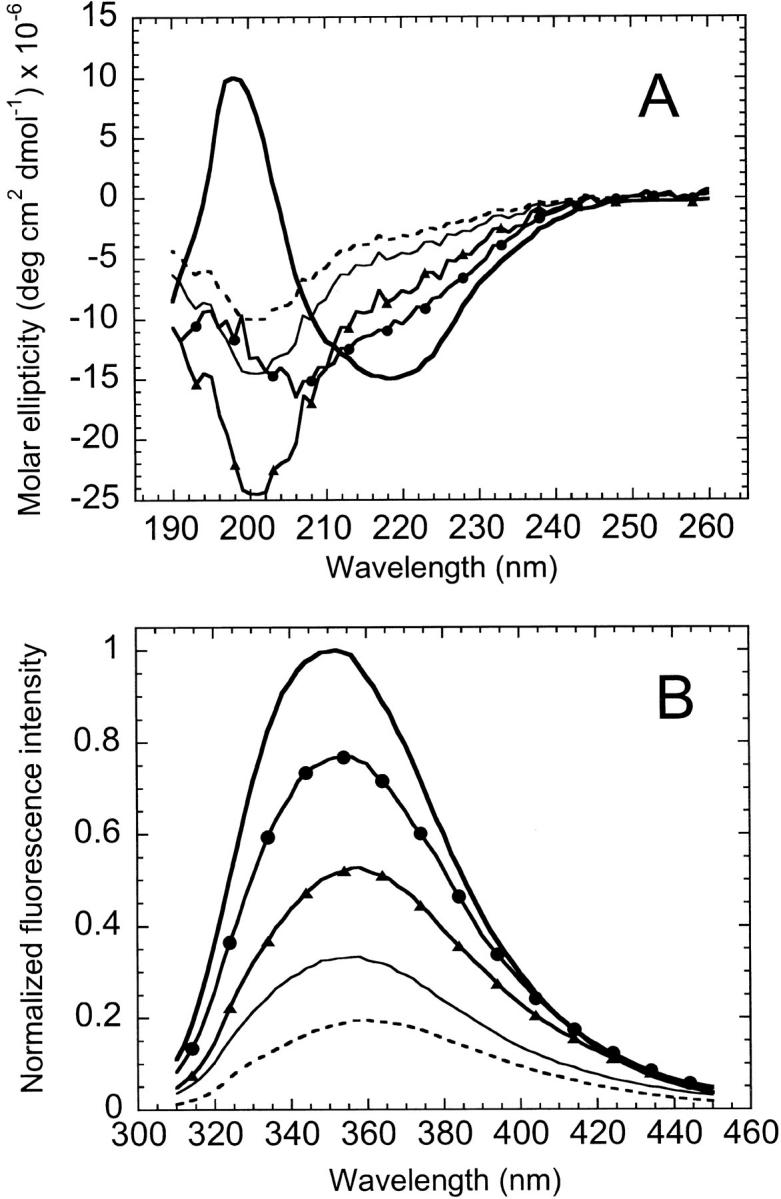

Characterization of individual fragments

As reported previously (Gegg et al. 1997), spectroscopic analyses of the individual fragments revealed that they are largely unstructured under conditions that favor the native conformation of AS-DHFR. Based on the minimum in ellipticity at 198 nm (Fig. 2A ▶), far-UV CD spectroscopy indicates that the fragments lack significant secondary structure. The observation that the fluorescence (Fig. 2B ▶) maximum emission is red-shifted from 350 nm in full length to 356 nm and 358 nm for fragments {1–86} and {87–159}, respectively, implies that the tertiary structure is disrupted as well. Equilibrium urea titrations of the individual fragments show the absence of cooperative structural changes as a function of denaturant concentration (data not shown). Taken together, these results are consistent with a lack of significant residual native-like structure in the isolated fragments.

Fig. 2.

Far-UV CD (A) and fluorescence spectra (B) of AS-DHFR and complementary fragments. In each plot, spectra are shown for AS-DHFR (heavy solid line), the 1 : 1 complex (solid line with circles), fragments {1–86} (thin solid line), {87–159} (dashed line) and the sum of the fragment spectra (solid line with triangles). Samples were in 10 mM KPi, 0.2 mM K2EDTA, pH 7.8 at 15° C. Sample concentrations were 6 to 10 μM for CD and 2 μM for fluorescence. The CD intensities are expressed in terms of molar ellipticity and the fluorescence spectra were normalized to the intensity of AS-DHFR at its λmax.

The noncovalent complex of fragments and the permutant have altered folded states relative to wild-type DHFR

When mixed in equimolar amounts under native conditions, the fragments {1–86} and {87–159} form a complex with secondary and tertiary structural features that are distinct from the sum of the individual fragments and from full-length DHFR. The far-UV CD spectrum of the complex has a substantially reduced negative ellipticity at 200 nm, indicative of less random-coil structure, than the sum of the individual fragments (Fig. 2A ▶). However, the spectrum of the complex still lacks the strong negative ellipticity at 222 nm and the positive ellipticity at 198 nm that are characteristic of full-length DHFR. The fluorescence emission spectrum of the complex (Fig. 2B ▶) has a greater intensity than the sum of the fragment intensities but less than that of the full-length protein. Finally, the complex has a λmax (354 nm) that is intermediate between the full-length (350 nm) and the summed fragments (357 nm). The nonadditive effects on both the CD and fluorescence spectra show that the two fragments associate spontaneously in solution. However, the distinct differences between the spectra of the complex and those for the full-length protein show that the complex is less well structured.

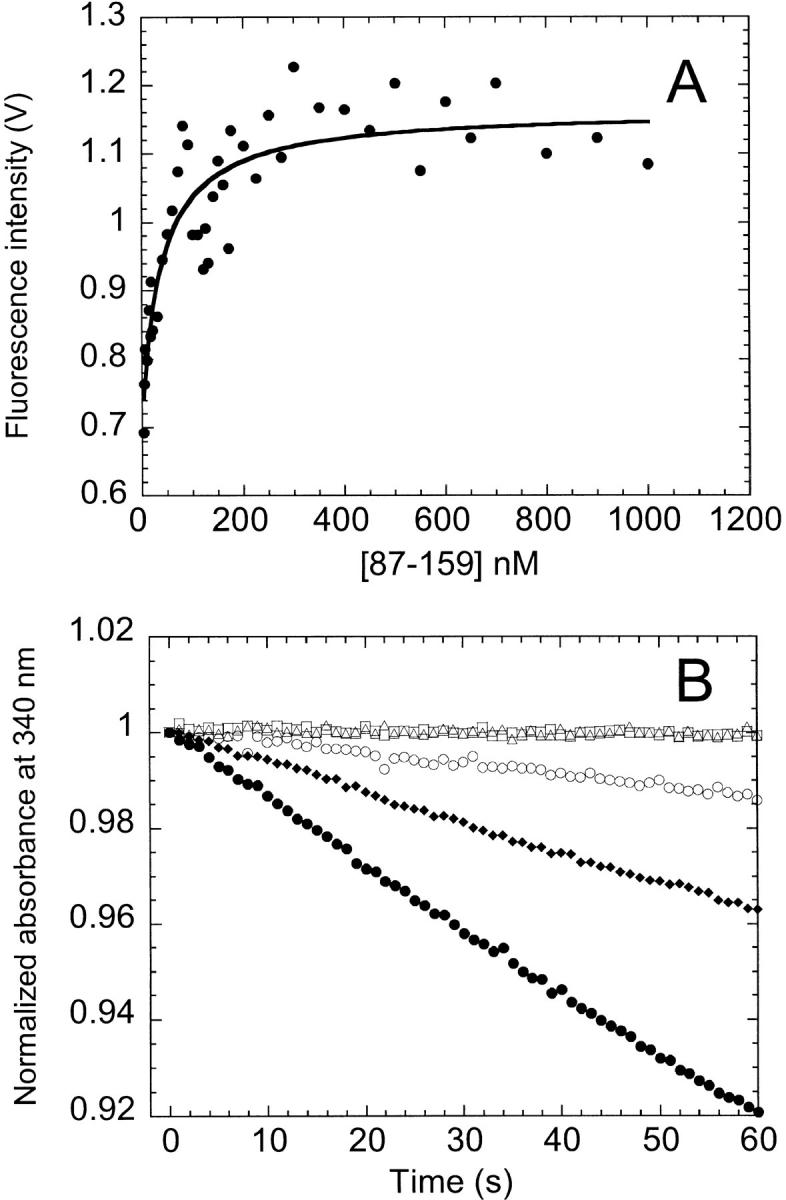

The enhanced fluorescence emission intensity of the complex relative to the sum of the individual fragments made it possible to determine the association constant for complex formation (Kippen and Fersht 1995). By titrating a fixed amount of {1–86} with increasing amounts of {87–159} and fitting the resulting isotherm to a stoichiometric binding model (Fig. 3A ▶), an association constant of 2.6 ± 0.9 × 107 M−1 was obtained. An association constant of this magnitude implies that ∼98% of the fragments are involved in the complex at a fragment concentration of 1 μM.

Fig. 3.

Presence of complex determined by equilibrium titration (A) and enzymatic activity (B). (A) The fluorescence emission intensity at 340 nm obtained from equilibrium titration of {87–159} into 0.5 μM {1–86} at 15° C is shown. The data have been corrected for background fluorescence from {87–159}. The solid line indicates the fit to a stoichiometric binding model. (B) Steady-state enzymatic activity was monitored by the time dependence of the absorbance at 340 nm at 15° C for fragments {1–86} (□) and {87–159} (▵), the 1 : 1 complex (○), cpG86 (♦), and AS-DHFR (·). Protein concentration was 20 nM. The buffer for both experiments is the same as described in Figure 2 ▶.

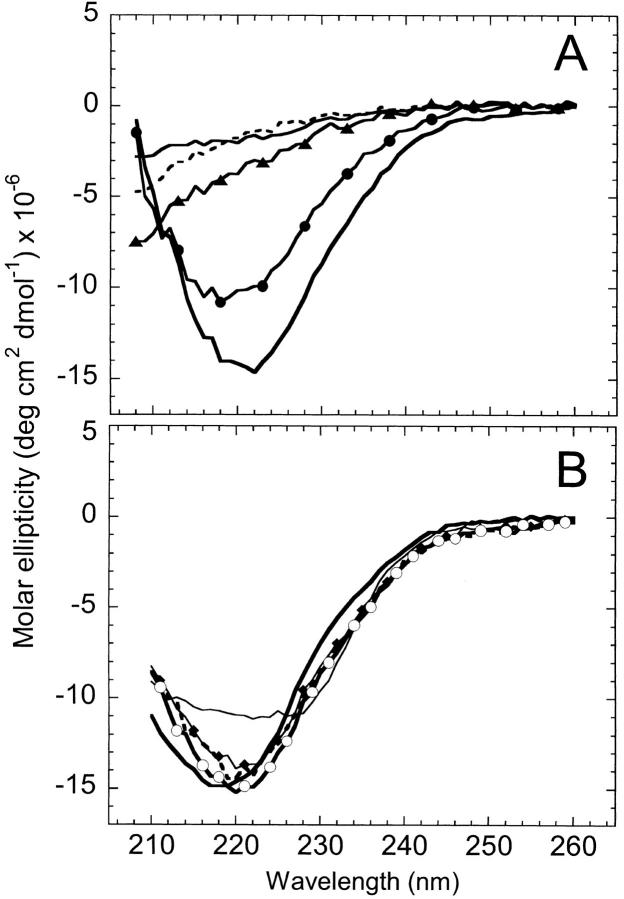

Analysis of cpG86 by far-UV CD revealed that the permuted protein has an altered spectrum relative to AS-DHFR (Fig. 4A ▶). Specifically, there is a shoulder at ∼230 nm and reduced intensity of both the negative ellipticity between 210 and 225 nm and the positive ellipticity at 200 nm. A difference spectrum taken by subtracting the cpG86 signal from WT-DHFR produces a symmetrical pattern (Fig. 4A ▶, inset) between 215 and 235 nm that is characteristic of exciton coupling (Keiderling et al. 1994). It is known from mutagenesis studies on wild-type DHFR (Kuwajima et al. 1991) that Trp 47 and Trp 74 are packed together in an orientation that produces an exciton coupling whose spectrum is very similar to the difference spectrum shown in Figure 4A ▶. Therefore, the far-UV CD data for cpG86 imply an alternative packing arrangement of these two tryptophans. Because the fluorescence spectrum of cpG86 (Fig. 4B ▶) has an identical λmax and only slightly lower intensity than AS-DHFR, the change in the orientation of these two buried tryptophans must not result in significantly different solvent exposure.

Fig. 4.

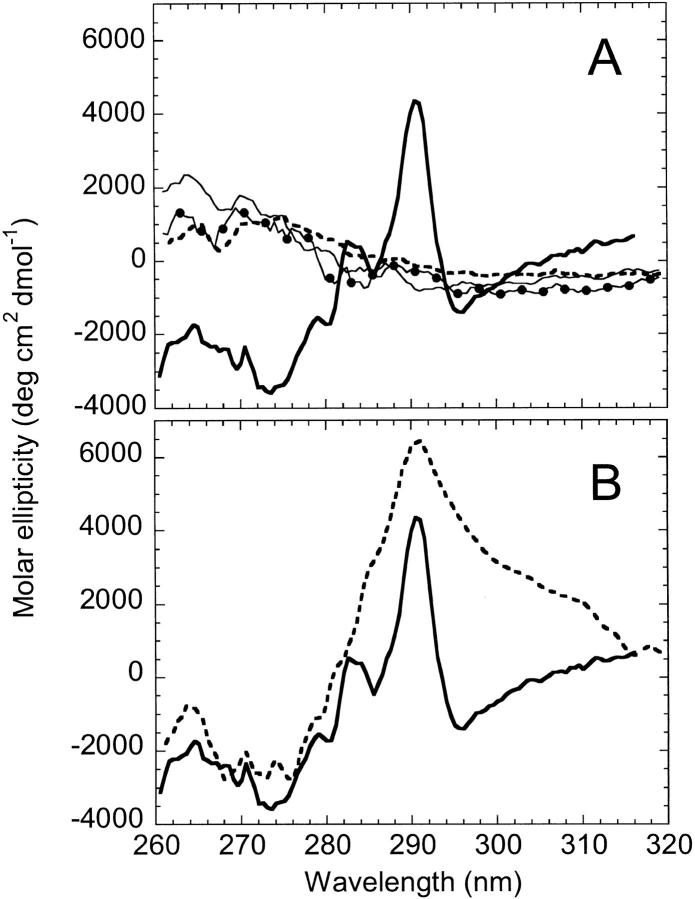

Far-UV CD (A) and fluorescence (B) spectra for cpG86 (dashed line) and AS-DHFR (solid line). The inset in panel A is the difference spectrum obtained by subtracting the cpG86 signal from AS-DHFR. The CD spectral intensities are expressed in mean residue ellipticity; the fluorescence intensities were normalized to the AS-DHFR spectrum as in Figure 2 ▶. Sample concentrations were 10 μM for far-UV CD and 2 μM for fluorescence. Buffer conditions were as in Figure 2 ▶.

Near-UV CD spectroscopy was used to determine if the aromatic side chains of the isolated fragments, the 1 : 1 complex and cpG86 have unique tertiary packing environments. The CD spectra of the individual fragments and the complex between 260 and 320 nm are relatively flat and featureless (Fig. 5A ▶), consistent with an absence of specific tertiary packing of the chromophores. In particular, the prominent peak observed for AS-DHFR at 290 nm is not observed in the individual fragments and the 1 : 1 complex. Combined with the presence of secondary structure observed in the far-UV CD region (Fig. 2A ▶), this result suggests that the 1 : 1 complex has structural features consistent with a molten globule-like species (Kuwajima 1989; Ptitsyn 1995). In contrast, cpG86 exhibits a strong maximum at 290 nm (Fig. 5B ▶) but is lacking most of the spectroscopic fine structure observed for AS-DHFR in the region between 270 and 300 nm. The implied differences in the packing of the aromatic side chains might be related, in part, to the disruption of the exciton coupling between tryptophans 47 and 74 detected by far-UV CD spectroscopy (Fig. 4A ▶).

Fig. 5.

Near-UV CD spectra of AS-DHFR, complementary fragments (A) and cpG86 (B). (A) Spectra are shown for AS-DHFR (heavy solid line), the 1 : 1 complex (solid line with circles), and fragments {1–86} (thin solid line) and {87–159} (dashed line). (B) Spectra are shown for AS-DHFR (solid line) and cpG86 (dashed line). Protein concentration was 5 μM for all samples. Intensity is expressed in molar ellipticity. Buffer conditions were as in Figure 2 ▶.

Complex and permutant retain substantial enzymatic activity

Despite having nonnative spectroscopic features, the complex possesses about 15% of the activity of full-length AS-DHFR at 15° C (Fig. 3B ▶). Equally surprising is the observation that the complex retained activity at a concentration of 2 nM (data not shown), well below the ∼40 nM dissociation constant determined by fragment titration (Fig. 3A ▶). Further, the activity of the complex was constant within 20% between 2 nM and 400 nM, the dynamic range of the assay (data not shown). The lack of activity in the individual fragments (Fig. 3B ▶) shows that the activity observed for the complex was not due to contamination by full-length AS-DHFR. The permutant has ∼50% the activity of wild-type DHFR at 15° C at a concentration of 20 nM (Fig. 3B ▶).

Unlike the fragments, which precipitate from solution at room temperature, cpG86 was soluble and remained 50% active when measured at 25° C (data not shown). An assay temperature of 15° C was chosen because it has previously been determined to provide maximum stability to wild type (Jennings et al. 1993) and AS-DHFR (Ionescu et al. 2000).

Native-like features partially restored by inhibitor

The observation that the complex is enzymatically active at nanomolar concentrations, despite having nonnative spectroscopic features, suggests that the substrate, dihydrofolate, and reducing cofactor, NADPH, might be inducing native-like structure in the complex. To test this hypothesis, the far-UV CD and fluorescence emission spectra were collected in the presence of the tight-binding, active site inhibitor methotrexate (MTX). MTX binds in the cleft between the two domains (Sawaya and Kraut 1997) (Fig. 1 ▶) and greatly stabilizes full-length protein against denaturation (Protasova et al. 1994).

The far-UV CD spectrum of the complex in the presence of a 20-fold excess of MTX is shown in Figure 6A ▶. The spectrum of the MTX-bound complex resembles that of full-length AS-DHFR bound to MTX. However, the minimum in the ellipticity is blue-shifted and reduced in intensity. The absence of a shoulder at 230 nm shows that Trp 47 and Trp 74 regain their native-like packing. MTX induced only minor changes in ellipticity for {1–86} and none for {87–159}, demonstrating that the signal enhancement requires both partners in the complex. Thus, the observation of enzymatic activity for the complex at nanomolar concentrations must reflect the induction of native-like structure by the binding of substrate and cofactor. Far-UV CD spectra of the fragments and complex in the presence of 100 μM folate and NADP+ (data not shown) are similar to those obtained in MTX, thus supporting this conclusion.

Fig. 6.

Far-UV CD spectra in the presence of MTX. (A) Spectra are shown for AS-DHFR (heavy solid line), the 1 : 1 complex (solid line with circles), fragments {1–86} (thin solid line) and {87–159} (dashed line), and the sum of the fragment spectra (solid line with triangles). Protein concentrations were between 6 and 10 μM. (B) cpG86 is shown in the presence of 0 μM (thin solid line), 5 μM (dashed line), and 20 μM (solid line with diamonds) MTX. AS-DHFR is shown in the presence (solid line with white circles) and absence (heavy solid line) of 20 μM MTX. Protein concentrations were 5 μM. Buffer conditions for all samples were as in Figure 2 ▶. Because of the high absorbance of MTX, it was not possible to obtain spectral data below ∼210 nm, precluding comparison with the full spectra.

cpG86 also adopted a secondary structure resembling wild-type DHFR in the presence of both stoichiometric and excess MTX (Fig. 6B ▶), consistent with previous studies on circularly permuted mouse enzyme (Buchwalder et al. 1992) and a version of E. coli DHFR with a less than optimal linker (Protasova et al. 1994). The shoulder at 230 nm disappeared and some of the negative ellipticity at 220 nm was restored, implying that the structural changes induced by ligand are sufficient to restore the wild-type packing of Trp 47 and Trp 74.

Urea denaturation of complex and permutant

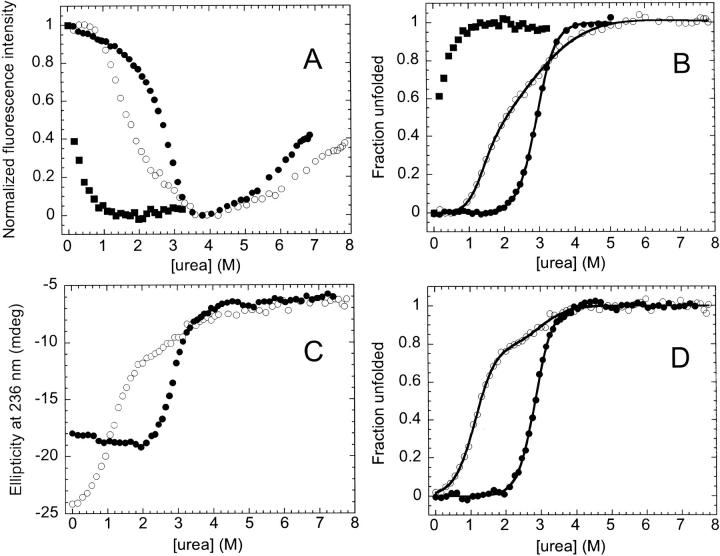

Attempts to measure the stability of the fragment complex by urea titration were hindered by the fact that, at micromolar concentrations, the complex is poised to dissociate and unfold even at the very lowest urea concentrations (Fig. 7A ▶). Unfortunately, the limited solubility of the complex precluded denaturation studies above 10 μM, whereby the shift in the equilibrium to favor complex might permit this type of stability analysis. The absence of structure in the isolated fragments, however, means that the stability of the complex can be estimated from the association constant, ΔG° = −RTln Ka. Although the stability at standard state, 10.1 kcal mol−1, is at the low end of the range in stabilities of other naturally occurring dimeric proteins (Neet and Timm 1994; Wallace et al. 1998), it is comparable to that of small systems such as the Arc repressor (Bowie and Sauer 1989) and the GCN4-p1 leucine zipper (Zitzewitz et al. 1995). Comparison of the stability of the complex with that of the full-length DHFR, 6.0 kcal mol−1, is ambiguous because the standard state conditions, 1 M, are far removed from those obtainable with biological materials.

Fig. 7.

Urea titration of cpG86, the 1 : 1 complex and AS-DHFR monitored by fluorescence (A,B) and far-UV CD (excluding 1 : 1 complex) (C,D). (A) Fluorescence intensity at 330 nm is shown for the 1 : 1 complex (▪), cpG86 (○) and AS-DHFR (·) as a function of urea concentration. In each case, the fluorescence intensity was normalized to the total difference in fluorescence signal observed for the native and unfolded forms at 330 nm. Sample concentration was 1 μM for the 1 : 1 complex, and 3 μM for cpG86 and AS-DHFR. (B) The fraction unfolded obtained from the fluorescence data in panel A is shown. The solid lines indicate a fit to a three-state (cpG86) or two-state (AS-DHFR) unfolding model. The absence of a native baseline precluded a fit of the 1 : 1 complex titration curve. (C) The ellipticity in millidegrees at 236 nm is shown for cpG86 (○) and AS-DHFR (•) as a function of urea concentration. Sample concentration was 5 μM. (D) The fraction unfolded obtained from the far-UV CD data in panel C is shown with the fits to either a three-state (cpG86) or two-state (AS-DHFR) model. Buffer conditions were as described in Figure 2 ▶. The fraction unfolded and the fits were obtained as described in Materials and Methods.

Equilibrium urea titrations were performed on cpG86 and monitored by tryptophan fluorescence emission and far-UV CD (Fig. 7 ▶). The observation of inflections in both the CD and fluorescence titration curves at ∼2 M urea implies that the unfolding of cpG86 involves an equilibrium intermediate. The titrations were completely reversible and could be fit to a three-state unfolding model as described in Materials and Methods. The difference in free energy, as determined by global fitting of CD and fluorescence urea titration data, between the native and unfolded states of cpG86, 6.3 kcal mol−1 (Table 1), is similar to that for AS-DHFR, 6.0 kcal mol−1. The intermediate has a stability of 2.2 kcal mol−1 relative to the native state and represents 85% of the population at 2.0 M urea. Surprisingly, the sum of the m values for the N⇌I and I⇌U transitions was 3.3 kcal mol−1 M−1, ∼60% greater than the m value for the two-state transition for AS-DHFR, 2.0 kcal mol−1 M−1. The correlation between m values and changes in buried surface area on unfolding (Myers et al. 1995) suggests that the permutant is either more compact than AS-DHFR under native conditions or unfolded to a greater extent in high denaturant than AS-DHFR.

Table 1.

Thermodynamic parameters obtained from equilibrium urea denaturation of cpG86

| ΔG° (kcal mol−1) | m (kcal mol−1 M−1) | Cma (M) | ||

| N ⇌ I | Far-UV CDb | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 1.1 |

| Fluorescencec | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.4 | |

| Globald | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 1.2 | |

| I ⇌ U | Far-UV CD | 4.1 ± 1.7 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 2.9 |

| Fluorescence | 3.8 ± 0.8 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 2.9 | |

| Global | 4.1 ± 1.3 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 2.9 | |

| N ⇌ U | (Global AS-DHFR)e | 6.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 |

a Errors in Cm are estimated to be ± 0.10 M urea.

b Thermodynamic parameters were derived from far-UV CD data by fitting to the baseline-corrected ellipticity at 236 nm.

c Thermodynamic parameters were derived from tryptophan emission fluorescence data by fitting to the fluorescence intensity at 330 nm.

d Global values represent a simultaneous fit of data derived from far-UV CD and fluorescence spectroscopy.

e Values shown for AS–DHFR are from Ionescu et al. (2000).

cpG86 is less stable to thermal denaturation than AS-DHFR

Equilibrium thermal denaturation was performed on cpG86 and monitored by tryptophan fluorescence emission and far-UV CD. Thermal denaturation was about 90% reversible in each case, based on comparison of spectra taken of the same sample before and after it was subjected to heating (data not shown). Because of their tendency to precipitate at and above room temperature, it was not possible to perform similar studies on the fragments and the 1 : 1 complex. Similar to AS-DHFR, the fluorescence melting profile of the permutant featured steeply sloping native and unfolded baselines (data not shown). The steep slopes in the baseline regions made it impossible to obtain reliable fits of the fluorescence thermal unfolding data. The profile obtained by monitoring the far-UV CD, however, featured relatively flat baselines (Fig. 8A ▶), making it possible to fit the data to an equilibrium model. In contrast to wild-type DHFR and AS-DHFR, which unfold by way of equilibrium thermal intermediates (Ohmae et al. 1996; Ionescu et al. 2000), the thermal unfolding data for the permutant were well-described by a two-state unfolding model (Fig. 8B ▶). Comparison of the Fapp plots at 226 nm, which monitors global secondary structure, and 236 nm, which monitors the tertiary packing of the exciton pair in the ABD, is especially revealing. For AS-DHFR, the Fapp plots at these two wavelengths are significantly different in both temperature midpoint, Tm, and slope, reflecting the presence of an equilibrium intermediate. For cpG86, however, these two plots coincide, consistent with a cooperative two-state unfolding reaction in which secondary and tertiary structure melt in a coordinated fashion. The Tm for the permutant was 32° C, significantly lower than either of the Tms reported for AS-DHFR (46° and 59° C) (Ionescu et al. 2000). Interestingly, the nonzero Fapp values at low temperatures show that the permutant undergoes a cold denaturation reaction that overlaps with the high-temperature denaturation process being studied. The fact that wild type and AS-DHFR do not exhibit cold denaturation suggests that the thermodynamic properties that make cpG86 unstable to high temperatures may also be responsible for its denaturation at low temperatures.

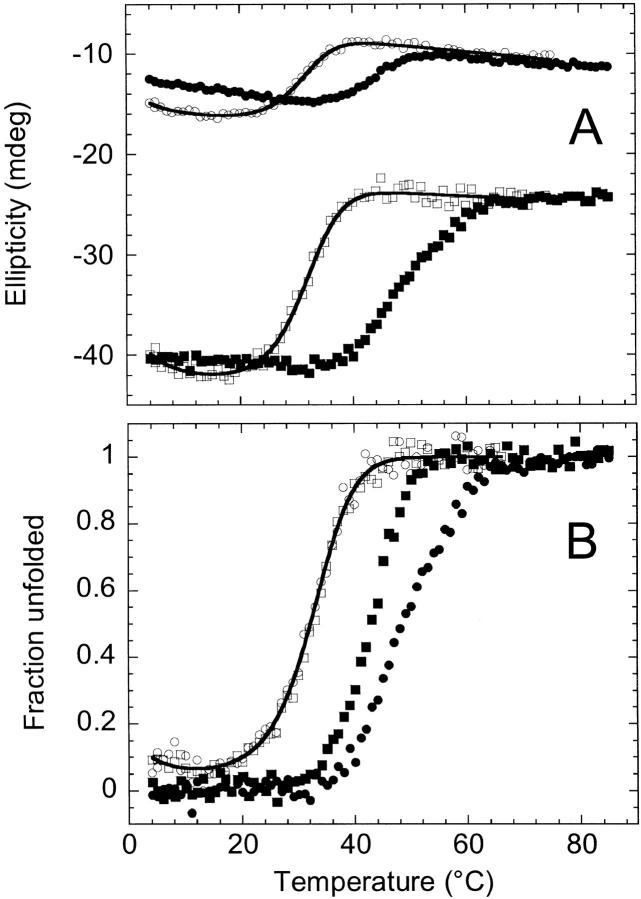

Fig. 8.

Equilibrium thermal denaturation of cpG86 and AS-DHFR monitored by far-UV CD. (A) The ellipticity in millidegrees at 236 nm (○,·) and 226 nm (□,▪) is plotted as a function of temperature for cpG86 (open symbols) and AS-DHFR (closed symbols). (B) The apparent fraction unfolded, calculated from the raw data in panel A, is plotted as a function of temperature. The cpG86 raw data and Fapp are shown with two-state fits. Although the AS-DHFR data may be fit to a two-state unfolding model when the wavelengths are analyzed individually, global fitting indicates that the thermal unfolding of AS-DHFR is best described by a three-state mechanism (Ionescu et al. 2000). Protein concentration was 5 μM. Buffer conditions were as described in Figure 2 ▶, except for temperature.

Methotrexate stabilizes cpG86 to urea denaturation

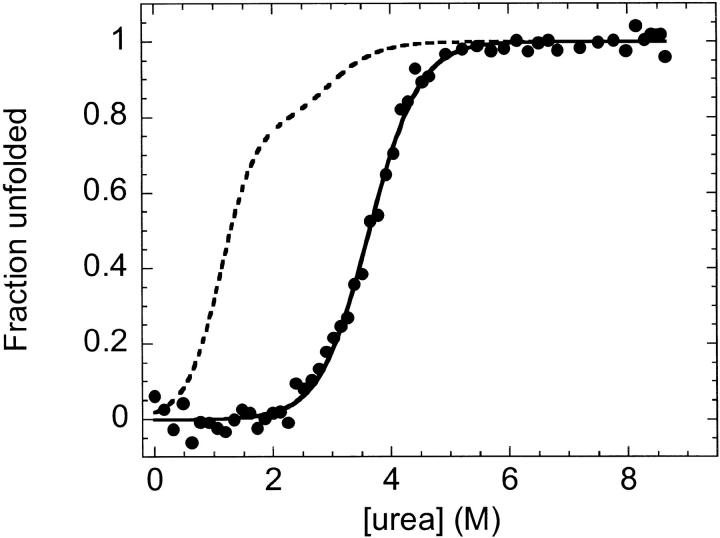

To test the effects of ligand binding on the unfolding reaction of cpG86, equilibrium urea denaturation was performed in the presence of excess MTX (Fig. 9 ▶) and monitored by far-UV CD. The MTX stabilized cpG86 dramatically, as reflected by an increased Cm, the transition midpoint, and converted the unfolding reaction from a three-state to an apparent two-state process. The absence of the equilibrium intermediate in the presence of MTX implies that only the folded form of cpG86 can bind MTX. The data were fit as described in Materials and Methods to obtain a stability of 11.2 kcal mol−1 for cpG86, which is comparable to the stability of 13.8 kcal mol−1 reported for wild-type E. coli DHFR in the presence of excess MTX and NADP+ (Protasova et al. 1994).

Fig. 9.

Equilibrium urea titration of cpG86 in the presence of MTX. The apparent fraction unfolded based on measurement of the far-UV CD signal at 236 nm (·) is shown as a function of urea concentration. The fit to a two-state unfolding model is indicated by the solid line. A dashed line indicating the three-state fit of the urea-induced unfolding in the absence of MTX (from Fig. 7D ▶) is shown for comparison. Protein concentration was 5 μM; MTX concentration was 20 μM. Buffer conditions were as described in Figure 2 ▶.

Discussion

The role of chain connectivity on stability and structure in DHFR

The observation that fragments {1–86} and {87–159} can spontaneously associate at micromolar concentrations implies that the formation of the complex has sufficient driving force to overcome the translational/rotational entropy penalty. Surprisingly, the cleavage of the backbone between residues 86 and 87, and/or the introduction of positive and negative charges at the new termini, destabilizes the fully folded form sufficiently to favor a poorly structured species. Tethering these two fragments with a penta-glycine linker between the natural amino- and carboxyl-termini enables the permutant to adopt a more well-structured form than the fragment complex.

However, the fully-folded permutant still differs from AS-DHFR with regard to the packing of two neighboring tryptophans in the ABD. The observation of partial enzymatic activity and the recovery of native-like optical properties after the addition of a tight-binding ligand to both fragment complex and permutant show that structures rather similar to AS-DHFR are accessible if sufficient driving force is applied. Therefore, the unique relationship between sequence and structure in a protein includes implicitly an important role for the connectivity of the chain of amino acids. This conclusion implies that the products of de novo protein design may depend on the placement of the termini.

Why is DHFR so sensitive to alteration of backbone connectivity?

At first glance, the reasons for the structural mutability of DHFR in response to fragmentation and permutation are not obvious. DHFR appears to have many structural features in common with proteins that are tolerant to changes in backbone connectivity. At 159 residues, it is larger than proteins such as barnase (110 residues) (Kippen et al. 1994), barley chymotrypsin inhibitor 2 (CI2) (83 residues) (Otzen and Fersht 1998), and thioredoxin (108 residues) (Chaffotte et al. 1997), but smaller than proteins such as ATCase (310 residues) (Graf and Schachman 1996), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (333 residues) (Vignais et al. 1995), and 1,3–1,4 β-glucanase (214 residues) (Ay et al. 1998), all of which withstand permutation and/or recombine from fragments into a native-like conformation. Like many of the complemented and permuted proteins studied, DHFR is a monomer with mixed α/β structure. It has two structural subdomains, one of which is discontinuous and similar to the subdomain structure of T4 lysozyme, another protein that is not greatly affected by changes to backbone connectivity (Llinas and Marqusee 1998). Furthermore, DHFR does not contain any disulfide bonds, covalently attached cofactors, coordinated metal ions, or cis-prolines that might complicate refolding. Clearly, one must look beyond native structural features to understand the sources of this structural variability.

One possible source of the variability is the low stability of DHFR, only ∼6 kcal mol−1 (Touchette et al. 1986; Iwakura et al. 1995; Ionescu et al. 2000). Supporting this argument is the greater stability of lysozyme (14 kcal mol−1) (Llinas and Marqusee 1998), barnase (8.8 to 9 kcal mol–1) (Pace et al. 1992; Clarke and Fersht 1993), thioredoxin (8–9.5 kcal mol−1) (Santoro and Bolen 1992; Georgescu et al. 1999), and CI2 (7.2 kcal mol−1) (Jackson and Fersht 1991), all of which produce native-like fragment complexes or well-folded permutants. The observation that tuna cytochrome c, the only protein in the set with a lower stability (ΔG° = 4.3 kcal mol−1) than AS-DHFR, also forms a non-native fragment complex (Yokota et al. 1998) implies that marginally stable proteins may offer more ready access to alternatively-folded states of low stability. The greater free energy gap between the native conformation of more stable proteins and alternative, partially-folded states may preclude the population of these alternative forms in response to changes in chain connectivity.

Another likely source of structural variability in DHFR may be related to its complex folding mechanism. Unlike most proteins used in fragmentation and permutation studies, DHFR has both equilibrium and kinetic folding intermediates. Although the equilibrium folding mechanism of DHFR is two-state by urea denaturation (Touchette et al. 1986; Iwakura et al. 1995), thermal unfolding studies have revealed intermediates in wild-type E. coli DHFR (Ohmae et al. 1996) and two cysteine-free variants, C85S/C152E (SE-DHFR) (Luo et al. 1995) and C85A/C152S (AS-DHFR) (Ionescu et al. 2000). Furthermore, the kinetic folding mechanism of DHFR includes burst-phase (Kuwajima et al. 1991) and hyperfluorescent intermediates that fold through four parallel refolding channels to multiple native conformations (Jennings et al. 1993). These intermediate states, combined with the low stability of the native state, may offer accessible, alternatively folded forms that could be related to those revealed by fragmentation and permutation.

What is the role of ligand in stabilizing the native structure of DHFR?

The ability of the natural ligands and the tight-binding inhibitor MTX to stabilize the native form of DHFR is well documented. For example, DHFR with MTX bound to it has been used as a molecular ``knot'' to study membrane translocation, because the binary complex is so stable that it does not unfold sufficiently to cross a membrane bilayer (Pfanner et al. 1987; Wienhues et al. 1991). Similarly, when MTX is bound to DHFR it becomes resistant to ubiquitin-based proteolytic degradation (Johnston et al. 1995). The fact that the intracellular concentration of the natural ligands, dihydrofolate and NADPH, is such that DHFR always has ligand bound (Fierke et al. 1987) suggests that the determinants of DHFR structure and stability may have evolved with a dependence on ligand. Consistent with this idea, human DHFR is weakly stable in the absence of ligands and has only been crystallized in the ligand-bound form (Davies et al. 1990).

Therefore, it is not surprising that ligand binding plays a crucial role in restoring native-like structure to the noncovalent complex formed between fragments {1–86} and {87–159}. Although MTX and the natural ligands do not induce structure in the individual fragments in isolation, they do bind to the noncovalent complex and induce native-like structure. The ligands bind sufficiently well to restore ∼15% of wild-type activity and ∼70% of the secondary structure, as determined by far-UV CD. Because the ligands bind in or across the cleft between the subdomains, they make contact with residues on both fragments that undoubtedly help to structure the ABD and the active site M20 loop.

In the case of the permutant cpG86, MTX induces native-like structure in the ABD as reflected by the far-UV CD spectrum and the restoration of the Trp47-Trp74 exciton pair. This finding is consistent with results on circularly permuted mouse DHFR (Buchwalder et al. 1992) that was found to have an altered secondary structure and lowered stability relative to wild type. One construct of circularly permuted DHFR from E. coli was found to resemble a molten globule (Protasova et al. 1994; Uversky et al. 1996). However, optimization of the linker sequence produces more native-like structures (Iwakura and Nakamura 1998). In both cases where the circular permutant had non-native features, it was discovered that the addition of natural ligands or inhibitors restored structure and enhanced stability.

Implications for evolution of protein structure and function

In their exon microgene theory, proposed to explain how introns evolved, Knowles and coworkers (Seidel et al. 1992) suggested that independently translated peptides might combine to form catalytic multichain assemblies even if the individual components lacked structural stability. Advantageous combinations would be favored by evolution and, eventually, could be more efficiently expressed by fusing their genes into a single entity. Based on the present results for AS-DHFR, this hypothesis could be extended to include the possibility that fragments could form stable complexes that are transformed to an alternative, functional conformation by ligand binding. The reduction in the entropy penalty by the prior formation of a complex between two essential peptide segments would enhance the binding of other potential partners, including biologically relevant ligands. The competitive advantages of this new function would eventually lead to the fusion of the two genes. The genes could be fused in either of two orientations, with natural selection favoring what would become the wild-type sequence over the permuted sequence based on enhanced activity and stability.

Recent studies on murine DHFR fragments fused to GCN4 leucine-zipper domains revealed that the fragments complement in vivo to form an enzymatically active complex (Pelletier et al. 1998). Pertinent to the present study, the murine DHFR fragments, {1–107} and {108–187}, correspond to E. coli fragments {1–86} and {87–159}. Interestingly, the results of site-directed mutagenesis of the fragments suggest that the folding and assembly of the fragments differ from that of full-length DHFR, consistent with our discovery of an alternatively folded form for these fragments. When considered with the results of the present study, it appears that changes in connectivity can expand the conformational space accessible to an amino acid sequence.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Ultra-pure urea (ICN Biomedical) was treated with AG-501X mixed-bed resin (BioRad) before addition of buffers to remove free cyanates. The concentration of urea was determined by refractive index measurements according to Pace and coworkers (1990). All other chemicals were of reagent grade and were used without further purification.

Protein purification

Fragments {1–86} and {87–159} were obtained according to methods described by Gegg and coworkers (1996). The cysteine-free mutant C85A/C152S DHFR (AS-DHFR), which served as a pseudo wild-type protein, and cpG86 were purified according to methods described by Iwakura and coworkers (1995).

The concentration of each protein was determined by absorbance at 280 nm using molar extinction coefficients of 22760 M−1 cm−1, 10810 M−1 cm−1, and 31100 M−1 cm−1 for {1–86}, {87–159}, and cpG86 and AS-DHFR, respectively (Gegg et al. 1996). Purity of fragments was judged to be >95% by SDS-gel electrophoresis. The identity of each fragment was confirmed by MALDI mass spectrometry.

Enzyme assay

Enzyme activity was determined at 15° C or 25° C using the method previously described by Iwakura (Iwakura et al. 1995). Enzyme assay conditions were chosen to match the buffer conditions used in fluorescence and CD spectroscopy. Activity was determined by monitoring the disappearance of NADPH and dihydrofolate by measuring the absorbance at 340 nm on an Aviv 14DS UV-visible spectrophotometer for 60 or 120 s in a thermostatted sample compartment. Background activity was recorded for each sample before the addition of protein and was subtracted from the final rate.

Spectroscopy

Far- and near-ultraviolet circular dichroism spectroscopy were performed on an Aviv 60-DS spectrometer. Far-UV spectra were collected using a 2 mm or 1 cm quartz cuvette maintained at 15° C by a thermoelectric temperature control system. Near-UV spectra were collected using a 10 cm cylindrical cuvette maintained at 15° C by a thermostatted circulating water-bath. A three-point smoothing algorithm was applied to the near-UV CD spectra because of their lower signal-to-noise ratio. For both near- and far-UV measurements, the stepsize was 1 nm with a 2 nm bandwidth and a 4 s averaging time. Each spectrum shown represents an average of 3–5 runs. All spectra were corrected for the background buffer contribution.

Fluorescence emission spectroscopic data were collected on an Aviv ATF 105 fluorometer. Except where noted, samples were excited at 295 nm, and emission was monitored from 310 to 450 nm at 1 nm intervals. Sample concentrations were between 0.5 and 5 μM, except for the Ka titration experiments (see below).

Spectra were collected in 1 cm quartz cuvettes maintained at 15° C in a thermostatted sample compartment. In preparation for all spectroscopic analyses, samples were dialyzed extensively against refolding buffer, 10 mM KPi, pH 7.8, and 0.2 mM K2EDTA, which had been degassed by aspiration and sparged with N2, at 4° C.

Circular dichroism data were reported either as raw ellipticity in millidegrees, in mean residue ellipticity (deg cm2 dmol−1)

|

where Θ is ellipticity in mdeg, c is the molar concentration, n is the number of residues in the protein or fragment, and l is the pathlength of the cuvette in cm, or in molar ellipticity (deg cm2 dmol−1)

|

using the same notation.

Ka determination

The association constant of the apo complex was determined by equilibrium titration of {87–159} into {1–86}. A series of samples was prepared containing 0.5 μM {1–86} and {87–159} in concentrations ranging from 1 nM to 500 nM. A parallel set of samples was prepared containing the same concentrations of {87–159}, but lacking {1–86}. Samples were prepared manually or using a Hamilton dispensing syringe and were equilibrated overnight at 4° C. The fluorescence emission spectrum of each sample was collected with excitation at 280 nm to maximize the signal. The difference spectrum was obtained for each titration sample. The emission at 340 nm was plotted for each concentration of {87–159} and fit to the following stoichiometric binding equation:

|

where Fi and Ff are the initial and final fluorescence signals, respectively, [{87–159}] is the molar concentration of fragment {87–159}, and Ka is the association constant in molar units. Because the spectroscopic signal arises almost entirely from fragment {1–86}, and because the concentration of {1–86} greatly exceeds that of {87–159} in the region of greatest signal change (i.e., near Ka−1), it is appropriate to fit the titration data to the hyperbolic equation shown above (Winzor and Sawyer 1995) rather than the quadratic expression that is used when the interacting partners are present in approximately equal amounts and are near Ka−1 (Bloomfield 1998). The value shown represents a simultaneous fit of three separate determinations.

Thermodynamic analysis

The urea dependence of the far-UV CD and fluorescence emission spectroscopic signals was fit according to published methods (Finn et al. 1992) to either a two-state model:

|

or to a 3-state model:

|

where N, I, and U represent the native, intermediate, and unfolded forms, respectively.

For both of the thermodynamic models, the free energy of unfolding in the absence of denaturant was calculated assuming a linear dependence of the apparent free-energy difference on the denaturant concentration (Schellman 1978; Pace 1986; Matthews 1987)

|

where ΔG°xy represents the Gibbs free energy at a given urea concentration, ΔG°xy (H2O) represents the Gibbs free energy in the absence of urea for the transition between states x and y, and m is the sensitivity of the transition to denaturant. Local and global fits of the data were obtained using Savuka version 5.1, an in-house nonlinear least-squares program. Global fitting methods are described elsewhere (Bilsel et al. 1999).

The equilibrium unfolding reaction for cpG86 in the presence of MTX was determined by fitting the far-UV CD data to the following two-state model:

|

where N • MTX is the binary complex between cpG86 and MTX, U is the unfolded protein, and MTX is free methotrexate. The data were fit as previously described for a binary complex (Zhang and Matthews 1998).

The fractional population of the N, I, and U states for cpG86 were determined using the partition function

|

where the individual fractions can be determined from Q as follows:

|

|

|

where fN, fI, and fU are the fractional populations of the native, intermediate, and unfolded states respectively; KNI and KIU represent the equilibrium constants for the N⇌I and I⇌U reactions, respectively.

The fractional populations of complex and fragments at 1 μM fragment concentration were determined from the measured association constant,

|

and the unitary stoichiometry ratios of the fragments and the complex. At 1 μM concentration of each fragment, 98% of the total protein is involved in the complex.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Katherine Bowers for assistance with fragment purification, Ms. Anna-Karin Svensson for performing enzyme activity assays, and Drs. Jill Zitzewitz, Osman Bilsel, and Roxana Ionescu for critical review of the manuscript. We also thank Dr. Masahiro Iwakura for providing the bacterial strain used for the production of cpG86.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked ``advertisement'' in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Abbreviations

ABD, adenosine-binding domain

AS-DHFR, C85A/C152S cysteine-free double mutant of dihydrofolate reductase

CD, circular dichroism

CI2, chymotrypsin inhibitor 2

cpG86, circularly-permuted DHFR that begins at Gly 86

DHFR, dihydrofolate reductase

K2EDTA, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, dipotassium salt

Fapp, apparent fraction of unfolded protein

KPi, potassium phosphate

MTX, methotrexate

NADPH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, reduced form

NADP+, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, oxidized form

Tm, temperature midpoint

UV, ultraviolet

WT, wild-type.

Article and publication are at www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.26601

References

- Anfinsen, C., Haber, E., Sela, M., and White, F. 1961. The kinetics of formation of native ribonuclease during oxidation of the reduced polypeptide chain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 47 1309–1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ay, J., Hahn, M., Decanniere, K., Piotukh, K., Borriss, R., and Heinemann, U. 1998. Crystal structures and properties of de novo circularly permuted 1,3–1,4-beta-glucanases. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 30 155–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilsel, O., Zitzewitz, J.A., Bowers, K.E., and Matthews, C.R. 1999. The folding mechanism of the α/β barrel protein, α-tryptophan synthase: Global analysis highlights the interconversion of multiple native, intermediate and unfolded forms through parallel channels. Biochemistry 38 1018–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield, V. 1998. Thermodynamics. In Principles of chemistry in biology. (ed. E. Theil), pp. 73–114. American Chemical Society, Washington DC.

- Bowie, J.U. and Sauer, R.T. 1989. Equilibrium dissociation and unfolding of the Arc repressor dimer. Biochemistry 28 7139–7143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchwalder, A., Szadkowski, H., and Kirschner, K. 1992. A fully active variant of dihydrofolate reductase with a circularly permuted sequence. Biochemistry 31 1621–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bystroff, C. and Kraut, J. 1991. Crystal structure of unliganded Escherichia coli dihydrofolate reductase. Ligand-induced conformational changes and cooperativity in binding. Biochemistry 30 2227–2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffotte, A.F., Li, J.H., Georgescu, R.E., Goldberg, M.E., and Tasayco, M.L. 1997. Recognition between disordered states: Kinetics of the self-assembly of thioredoxin fragments. Biochemistry 36 16040–16048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, J. and Fersht, A.R. 1993. Engineered disulfide bonds as probes of the folding pathway of barnase: Increasing the stability of proteins against the rate of denaturation. Biochemistry 32 4322–4329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, J., Delcamp, T., Prendergast, N., Ashford, V., Freisheim, J., and Kraut, J. 1990. Crystal structures of recombinant human dihydrofolate reductase complexed with folate and 5-deazafolate. Biochemistry 29 9467–9479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falzone, C., Wright, P., and Benkovic, S. 1991. Evidence for two interconverting protein isomers in the methotrexate complex of dihydrofolate reductase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 30 2184–2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y., Minnerly, J., Zurfluh, L., Joy, W., Hood, W., Abegg, A., Grabbe, E., Shieh, J., Thurman, T., McKearn, J., and McWherter, C.A. 1999. Circular permutation of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Biochemistry 38 4553–4563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fierke, C.A., Johnson, K.A., and Benkovic, S.J. 1987. Construction and evaluation of the kinetic scheme associated with dihydrofolate reductase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 26 4085–4092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn, B.E., Chen, X., Jennings, P.A., Saalau-Bethell, S.M., and Matthews, C.R. 1992. Principles of protein stability. Part 1 - Reversible unfolding of proteins: Kinetic and thermodynamic analysis. In Protein engineering: A practical approach. (ed. A.R. Rees, M.J.E. Sternberg, and R. Wetzel), pp. 167–189. IRL Press, Oxford.

- Gegg, C.V., Bowers, K.E., and Matthews, C.R. 1996. A general approach for the design and isolation of protein fragments: The molecular dissection of dihydrofolate reductase. In Techniques in protein chemistry VII. (ed. D. Marshak), pp. 439–448. Academic Press, San Diego.

- ———. Probing minimal independent folding units in dihydrofolate reductase by molecular dissection. Protein Sci. 6 1885–1892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Georgescu, R.E., Braswell, E.H., Zhu, D., and Tasayco, M.L. 1999. Energetics of assembling an artificial heterodimer with an α/β motif: Cleaved versus uncleaved Escherichia coli thioredoxin. Biochemistry 38 13355–13366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf, R. and Schachman, H. 1996. Random circular permutation of genes and expressed polypeptide chains: Application of the method to the catalytic chains of aspartate transcarbamoylase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93 11591–11596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ionescu, R.I., Smith, V.F., O'Neill, J.C., and Matthews, C.R. 2000. Multi-state equilibrium unfolding of E. coli dihydrofolate reductase: Thermodynamic and spectroscopic description of the native, intermediate and unfolded ensembles. Biochemistry 39 9540–9550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwakura, M. and Honda S. 1996. Stability and reversibility of thermal denaturation are greatly improved by limiting terminal flexibility of Escherichia coli dihydrofolate reductase. J. Biochem. 119 414–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwakura, M. and Nakamura, T. 1998. Effects of the length of a glycine linker connecting the N- and C-termini of a circularly permuted dihydrofolate reductase. Protein Eng. 11 707–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwakura, M., Jones, B.E., Luo, J., and Matthews, C.R. 1995. A strategy for testing the suitability of cysteine replacements in dihydrofolate reductase from Escherichia coli. J. Biochem. 117 480–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwakura, M., Nakamura, T., Yamane, C., and Maki, K. 2000. Systematic circular permutation of an entire protein reveals essential folding elements. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7 580–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, S.E. and Fersht, A.R. 1991. Folding of chymotrypsin inhibitor 2. 1. Evidence for a two-state transition. Biochemistry 30 10428–10435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, P.A., Finn, B.E., Jones, B.E., and Matthews, C.R. 1993. A reexamination of the folding mechanism of dihydrofolate reductase from Escherichia coli: Verification and refinement of a four-channel model. Biochemistry 32 3783–3789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, J.A., Johnson, E.S., Waller, P.R.H., and Varshavsky, A. 1995. Methotrexate inhibits proteolysis of dihydrofolate reductase by the N-end rule pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 270 8172–8178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiderling, T.A., Wang, B., Urbanova, M., Pancoska, P., and Dukor, R.K. 1994. Empirical studies of protein secondary structure by vibrational circular dichroism and related techniques. Faraday Discussions 99 263–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kippen, A.D. and Fersht, A.R. 1995. Analysis of the mechanism of assembly of cleaved barnase from two peptide fragments and its relevance to the folding pathway of uncleaved barnase. Biochemistry 34 1464–1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kippen, A.D., Sancho, J., and Fersht, A.R. 1994. Folding of barnase in parts. Biochemistry 33 3778–3786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraulis, P.J. 1991. MOLSCRIPT: A program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 24 946–950. [Google Scholar]

- Kuwajima, K. 1989. The molten globule state as a clue for understanding the folding and cooperativity of globular-protein structure. Proteins 6 87–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwajima, K., Garvey, E.P., Finn, B.E., Matthews, C.R., and Sugai, S. 1991. Transient intermediates in the folding of dihydrofolate reductase as detected by far-ultraviolet circular dichroism spectroscopy. Biochemistry 30 7693–7703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinas, M. and Marqusee, S. 1998. Subdomain interactions as determinants in the folding and stability of T4 lysozyme. Protein Sci. 7 96–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J., Iwakuro, M., and Matthews, C.R. 1995. Detection of a stable intermediate in the thermal unfolding of a cysteine-free form of dihydrofolate reductase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 34 10669–10675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, C.R. 1987. Effect of point mutations on the folding of globular proteins. Methods Enzymol. 154 498–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers, J.K., Pace, C.N, and Scholtz, J.M. 1995. Denaturant m values and heat capacity changes: Relation to changes in accessible surface areas of protein unfolding. Protein Sci. 4 2138–2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neet, K.E. and Timm, D.E. 1994. Conformational stability of dimeric proteins: Quantitative studies by equilibrium denaturation. Protein Sci. 3 2167– 2174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohmae, E., Kurumiya, T., Makino, S., and Gekko, K. 1996. Acid and thermal unfolding of Escherichia coli dihydrofolate reductase. J. Biochem. 120 946– 953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otzen, D. and Fersht, A. 1998. Folding of circular and permuted chymotrypsin inhibitor 2: Retention of the folding nucleus. Biochemistry 37 8139–8146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace, C.N. 1986. Determination and analysis of urea and guanidine hydrochloride denaturation curves. Methods Enzymol. 131 266–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace, C.N., Shirley, B.A., and Thomson, J.A. 1990. Measuring the conformation stability of a protein. In Protein structure: A practical approach. (ed. T.E. Creighton), pp. 311–330. IRL Press, Oxford.

- Pace, C.N., Laurents, D.V., and Ericksen, R.E. 1992. Urea denaturation of barnase: pH dependence and characterization of the unfolded state. Biochemistry 31 2728–2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier, J.N., Campbell-Valois, F.X., and Michnick, S.W. 1998. Oligomerization domain-directed reassembly of active dihydrofolate reductase from rationally designed fragments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95 12141– 12146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfanner, N., Tropschug, M., and Neupert, W. 1987. Mitochondrial protein import: Nucleoside triphosphates are involved in conferring import-competence to precursors. Cell 49 815–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Protasova, N.Y., Kireeva, M.L., Murzina, N.V., Murzin, A.G., Uversky, V.N., Gryaznova, O.I., and Gudkov, A.T. 1994. Circularly permuted dihydrofolate reductase of E. coli has functional activity and a destabilized tertiary structure. Protein Eng. 7 1373–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptitsyn, O.B. 1995. Molten globule and protein folding. Adv. Prot. Chem. 47 83–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritco-Vonsovici, M., Minard, P., Desmadril, M., and Yon, J.M. 1995. Is the continuity of the domains required for the correct folding of a two-domain protein? Biochemistry 34 16543–16551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro, M.M. and Bolen, D.W. 1992. A test of the linear extrapolation of unfolding free energy changes over an extended denaturant range. Biochemistry 31 4901–4907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawaya, M.R. and Kraut, J. 1997. Loop and subdomain movements in the mechanism of Escherichia coli dihydrofolate reductase: Crystallographic evidence. Biochemistry 36 586–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schellman, J.A. 1978. Solvent denaturation. Biopolymers 17 1305–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidel, H.M., Pompliano, D.L., and Knowles, J.R. 1992. Exons as microgenes? Science 257 1489–1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touchette, N.A., Perry, K.M., and Matthews, C.R. 1986. Folding of dihydrofolate reductase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 25 5445–5452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uversky, V.N., Kutyshenko, V.P., Protasova, N.Y., Rogov, V.V., Vassilenko, K.S., and Gudkov, A.T. 1996. Circularly permuted dihydrofolate reductase possesses all the properties of the molten globule state, but can resume functional tertiary structure by interaction with its ligands. Protein Sci. 5 1844–1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignais, M., Corbier, C., Mulliert, G., Branlant, C., and Branlant, G. 1995. Circular permutation within the coenzyme binding domain of the tetrameric glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase from Bacillus stearothermophilus. Protein Sci. 4 994–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viguera, A., Serrano, L., and Wilmanns, M. 1996. Different folding transition states may result in the same native structure. Nature Struct. Biol. 3 874–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, L.A., Sluis-Cremer, N. and Dirr, H.W. 1998. Equilibrium and kinetic unfolding properties of dimeric human glutathione transferase A1–1. Biochemistry 37 5320–5328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieligmann, K., Norledge, B., Jaenicke, R., and Mayr, E. 1998. Eye lens betaB2-crystallin: Circular permutation does not influence the oligomerization state but enhances the conformational stability. J. Mol. Biol. 280 721–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wienhues, U., Becker, K., Schleyer, M., Guiard, B., Tropschug, M., Horwich, A.L., Pfanner, N., and Neupert, W. 1991. Protein folding causes an arrest of preprotein translocation into mitochondria in vivo. J. Cell. Biol. 115 1601–1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winzor, D.J. and Sawyer, W.H. 1995. Quantitative characterization of ligand binding. Wiley-Liss, New York.

- Yokota, A., Takenaka, H., Oh, T., Noda, Y., and Segawa, S. 1998. Thermodynamics of the reconstitution of tuna cytochrome c from two peptide fragments. Protein Sci. 7 1717–1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. and Matthews, C.R. 1998. Ligand binding is the principal determinant of stability for the p21 (H)-ras protein. Biochemistry 37 14881–14890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T., Bertelsen, E., Benvegnu, D., and Alber, T. 1993. Circular permutation of T4 lysozyme. Biochemistry 32 12311–12318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zitzewitz, J.A., Bilsel, O., Luo, J., Jones, B.E., and Matthews, C.R. 1995. Probing the folding mechanism of a leucine zipper peptide by stopped-flow circular dichroism spectroscopy. Biochemistry 34 12812–12819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]