Abstract

Multiple herpes simplex virus type 1 functions control translation by regulating phosphorylation of the initiation factor eIF2 on its alpha subunit. Both of the two known regulators, the γ134.5 and Us11 gene products, are produced late in the viral life cycle, although the γ134.5 gene is expressed prior to the γ2 Us11 gene, as γ2 genes require viral DNA replication for their expression while γ1 genes do not. The γ134.5 protein, through a GADD34-related domain, binds a cellular phosphatase (PP1α), maintaining pools of active, unphosphorylated eIF2. Infection of a variety of cultured cells with a γ134.5 mutant virus results in the accumulation of phosphorylated eIF2α and the inhibition of translation prior to the completion of the viral lytic program. Ectopic, immediate-early Us11 expression prevents eIF2α phosphorylation and the inhibition of translation observed in cells infected with a γ134.5 mutant by inhibiting activation of the cellular kinase PKR and the subsequent phosphorylation of eIF2α; however, a requirement for the Us11 protein, produced in its natural context as a γ2 polypeptide, remains to be demonstrated. To determine if Us11 regulates late translation, we generated two Us11 null viruses. In cells infected with a Us11 mutant, elevated levels of activated PKR and phosphorylated eIF2α were detected, viral translation rates were reduced 6- to 7-fold, and viral replication was reduced 13-fold compared to replication in cells infected with either wild-type virus or a virus in which the Us11 mutation was repaired. This establishes that the Us11 protein is critical for proper late translation rates. Moreover, it demonstrates that the shutoff of protein synthesis observed in cells infected with a γ134.5 mutant virus, previously ascribed solely to the γ134.5 mutation, actually results from the combined loss of γ134.5 and Us11 functions, as the γ2 Us11 mRNA is not translated in cells infected with a γ134.5 mutant.

In addition to seizing control of the cellular translational apparatus, many viruses must overcome a cellular response that triggers the inhibition of protein synthesis, limiting their replication and spread within the host (reviewed in reference 27). This innate antiviral strategy is thought to proceed through the detection of copious quantities of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) produced from viral genomes in infected cells (reviewed in reference 21). Following its activation by dsRNA, the cellular kinase PKR subsequently phosphorylates the alpha subunit of eIF2, resulting in the inactivation of this critical translation initiation factor and the cessation of protein synthesis prior to the completion of the viral life cycle. To circumvent the potentially serious attempts by the host to incapacitate eIF2, thus disabling the protein synthesis machinery, viruses encode an array of diverse functions that act to preserve the activity of this initiation factor (reviewed in reference 27).

At least 2 of the over 80 open reading frames (ORFs) contained in the large herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) DNA genome can specify polypeptides with the capability to regulate eIF2α phosphorylation (reviewed in references 24 and 27). The γ134.5 gene product has homology with the cellular GADD34 protein at its carboxyl terminus (8), and both proteins can function as regulatory subunits for the cellular protein phosphatase 1α (PP1α), targeting the activity of the holoenzyme to phosphorylated eIF2α (10, 11). In addition to exhibiting markedly reduced neurovirulence following intracranial administration to mice (3, 6, 16), γ134.5 mutant viruses are unable to complete their life cycle in many cultured cell lines due to the accumulation of phosphorylated eIF2α and the subsequent inhibition of translation (7). The viral replicative program arrests some time after the onset of DNA synthesis, as γ2 or “true-late” mRNAs, whose expression is dependent on DNA replication, accumulate in cells infected with a γ134.5-deficient virus although they are not translated (7). Therefore, γ134.5 mutants are not only deficient in γ134.5 functions but also fail to synthesize the gene products specified by viral γ2 genes, one of which is Us11, whose product is a dsRNA binding (14), ribosome-associated protein (26). The Us11 protein physically associates with PKR (5, 22, 23) and can prevent PKR activation in response to dsRNA and PACT, a cellular protein that can activate PKR in an RNA-independent manner (22). Furthermore, the Us11 protein can preclude the premature cessation of protein synthesis observed in cells infected with a γ134.5 mutant when it is expressed at immediate-early (IE), as opposed to late, times postinfection (17, 19).

The function of Us11 in its natural wild-type (WT) context as a true-late or γ2 gene remains unknown. Viruses deficient for Us11 function have been described previously (4, 15, 29). Despite the fact that these viruses contained extremely large deletions that eliminated several genes in addition to Us11, their ability to replicate in several standard cell lines commonly used in laboratories investigating HSV-1 was unaffected. These established cell lines, however, are permissive for the growth of γ134.5 mutant viruses (6, 16) and therefore support the replication of viruses that cannot overcome host defenses. This raises the very real possibility that these same cell lines, for analogous reasons, may not be appropriate to assess the phenotype of Us11 mutants.

To evaluate the role(s) of Us11 expressed in its natural context as a γ2 gene, we generated a panel of mutant viruses deficient for either Us11, γ134.5, or both Us11 and γ134.5 along with corresponding viruses in which the mutant alleles were repaired. Viral growth, PKR activation, and eIF2α phosphorylation, along with rates of viral protein synthesis, were measured through the course of an infection in human cells competent to mount a robust antiviral response following infection with a γ134.5 mutant virus. The results of this study demonstrate that the γ134.5 gene product, but not the true-late γ2 Us11 protein, is required to maintain wild-type rates of protein synthesis from the onset of viral DNA replication through the initial segment of the late phase of infection. However, late in the infectious program, HSV-1 relies more heavily on Us11 to counter host defenses and sustain viral translation. Thus, the drastic inhibition of protein synthesis observed in cells infected with a γ134.5 mutant virus actually results from the loss of not only the γ134.5 function but also the failure to translate the Us11 polypeptide. Moreover, it illustrates that eIF2α phosphorylation is controlled through different mechanisms at discrete phases of the viral life cycle.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

All cells were propagated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 50 U of penicillin/ml, and 50 μg of streptomycin/ml. To this medium, 5% calf serum was added for Vero cells, 10% fetal bovine serum was added for PKR0/0 cells (immortalized mouse embryo fibroblasts in which both PKR alleles were disrupted [30]), and a mixture of 5% calf serum and 5% fetal bovine serum was added for U373 cells. When phosphonoacetic acid (PAA; Sigma) was utilized, cells were pretreated for 1 h with PAA (300 μg/ml) and then infected in the presence of PAA (300 μg/ml).

Construction of recombinant viruses.

The Δ34.5 virus (SPBg5e) has been described previously (17). The Δ34.5-(IE)Us11 virus, SUP1, has also been described (17).

The HSV-1 Patton strain was used throughout this study. Nucleotide coordinates refer to the published strain 17 sequence (GenBank accession no. X14112). Derivatives of the plasmid pSXZY contain the Us10-to-Us12 region along with flanking sequences (nucleotides 143481 to 147040) and serve to target the Us11 alleles to the homologous region in the viral genome. To construct the Us11 mutant targeting plasmids, a double-stranded oligonucleotide containing BstEII sticky ends was inserted into the BstEII site of pSXZY, creating pSXZY-st12-Xb/Ml. The double-stranded oligonucleotide contains the final two codons specified by the Us12 ORF followed by a stop codon, along with XbaI and MluI sites inserted 3′ to the Us12 stop codon. pSXZY-st12-Xb/Ml was then digested with XbaI and MluI and an NheI-MluI fragment from pEGFP-C2 (Clontech), which contains the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) ORF and simian virus 40 (SV40) polyadenylation signal, was inserted. This plasmid, named pSXZY-GFP, inserts the EGFP ORF and SV40 polyadenylation signal downstream of the Us12 stop codon under the transcriptional control of the Us11 promoter but 5′ to the Us11 ATG and serves as the pAUs11 targeting construct. To create the ΔUs11 targeting construct which inserts the EGFP ORF and SV40 polyadenylation signal in place of the Us11 ORF, pSXZY-GFP was digested with MluI and PflMI and the overhanging ends were filled in with Klenow polymerase. The large-fragment-containing vector and HSV-1 sequences was then recircularized with T4 DNA ligase.

After digestion with PvuII to release the viral sequences from the plasmid backbone, 10 μg of digested plasmid DNA was cotransfected along with purified Δ34.5 viral DNA into Vero cells to create recombinant viruses that were deficient in both γ134.5 and Us11 function. Infectious virus obtained from these transfections was subsequently used to infect PKR0/0 cells, facilitating the isolation of recombinants that lacked all known viral functions capable of antagonizing this cellular enzyme. Plaques that exhibited EGFP fluorescence were subjected to several (4-6) further rounds of plaque purification. Southern analysis was performed to verify the physical structure of the plaque-purified recombinants.

To create recombinant viruses deficient only in Us11 function, infectious viral DNA was isolated from the γ134.5-Us11 double-mutant viruses and cotransfected into Vero cells with the WT BamHI SP fragment. This fragment contains the γ134.5 ORF and serves to repair the γ134.5 mutation introduced into the Δ34.5 virus. Infectious virus obtained from these transfections was passaged twice in U373 cells, which are nonpermissive for the growth of γ134.5 mutant viruses (18). γ134.5-positive Us11 mutant viruses were then isolated through two rounds of plaque purification. The presence of two WT copies of γ134.5 was then verified by Southern analysis as described previously (19).

Repair of the Us11 mutations was accomplished by cotransfecting PvuII-digested pSXZY along with purified viral DNA isolated from a Us11 mutant into Vero cells. Infectious virus obtained from these transfections was then passaged four times in U373 cells to enrich for recombinants in which the Us11 gene was restored. At this juncture, the repair viruses constituted approximately one-half of the viral population by Southern analysis. To isolate the repair viruses, several plaques were picked at random and used to prepare stocks. Vero cells were subsequently infected with these stocks to screen for the presence of Us11 expression and the absence of GFP expression by immunoblotting. Plaques that expressed Us11 but did not express GFP were then subjected to a second round of plaque purification, and their genetic structure was verified by Southern analysis as described previously (19).

35S labeling of newly synthesized proteins.

[35S]cysteine and [35S]methionine labeling of proteins was performed as described previously (17). To quantify rates of protein synthesis, triplicate samples of total protein lysates were adjusted to 24% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and allowed to precipitate on ice for 15 to 30 min. The precipitate was collected onto glass fiber filters (GF-C; Whatman) and washed with TCA followed by 95% ethanol, and the dried filters were counted in liquid scintillant.

PKR kinase assay.

The PKR kinase assay was performed as described previously (19).

Antibodies.

The Us11 monoclonal antibody has been described (26). The GFP antibody was from Molecular Probes (catalog no. A11120). The eIF2α phospho-Ser 51-specific antibody was from Research Genetics (catalog no. RG0001), and the monoclonal antibody that detects both phosphorylated and unphosphorylated eIF2α has been described (28). Polyclonal antisera against the amino-terminal 69 residues of the γ134.5 protein (Patton strain) was raised in rabbits with a glutathione S-transferase fusion protein as the antigen.

Multicycle growth curves.

U373 cells were seeded onto 60-mm-diameter dishes at 106 cells per dish. Twenty-four hours later the medium was replaced with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium-2% fetal bovine serum, and approximately 103 PFU of virus were added to triplicate plates. At 2, 3, 4, and 5 days postinfection, cell-free lysates were prepared and titered (in duplicate) in Vero cells.

RESULTS

Construction of Us11 mutant viruses.

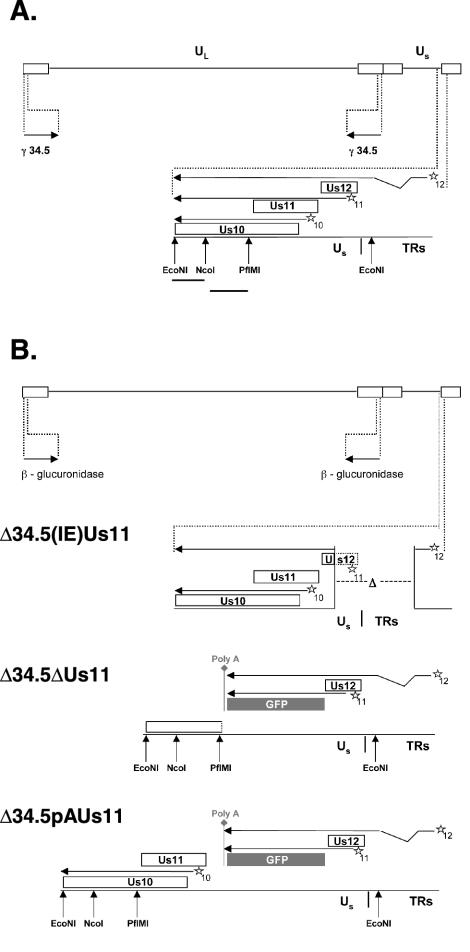

To investigate the role(s) of the Us11 protein expressed in its native context as a late viral protein, a panel of mutant viruses deficient for Us11, γ134.5, or both genes was created (Fig. 1B). The γ134.5 deletion mutant virus (Δ34.5), in which both copies of the γ134.5 gene were replaced by sequences encoding β-glucuronidase, and the Δ34.5(IE)Us11 virus have been previously described (17). The latter virus was isolated by selecting Δ34.5 suppressor variants capable of replicating in cells that failed to support the growth of the parental Δ34.5 mutant. In addition to the γ134.5 mutation, Δ34.5(IE)Us11 contains a 583-bp deletion that removes most of the Us12 ORF, including the initiator AUG codon, and that spans the adjoining Us-TRs junction. As the Us11 γ2 promoter is contained within the deleted segment of the Us12 ORF, the deletion also results in the translation of the Us11 protein from an mRNA that initiates from the Us12 IE promoter (Fig. 1B). Indeed, the IE expression of Us11 was shown to be sufficient to overcome the block to the replication of Δ34.5 mutants in nonpermissive cells (19).

FIG. 1.

Structure of the HSV-1 recombinants and the strategy for repairing mutant alleles. (A) The wild-type HSV-1 genome. Boxed regions, inverted terminal repeat (TR) regions that flank the unique short (US) and unique long (UL) components (solid lines). The location and orientation of both copies of the γ134.5 gene are indicated. The US-TR junction region containing the Us10, Us11, and Us12 ORFs (open rectangles; stars, respective cis-acting promoter elements) appears expanded beneath the genome. Arrows above boxes extending from the promoter element, mRNA transcripts that encode gene products. All of these mRNAs are polyadenylated at a common polyadenylation signal (not depicted) downstream from the Us10 ORF. The Us12 mRNA is spliced, and joining two noncontiguous regions to form the mRNA indicates this. Solid lines below the restriction enzyme sites, probes used to detect the Us10-to-US12 region. (B) Genomic structure of recombinant HSV-1 mutants. The genomes represented are all those of γ134.5 deletion mutants that contain the β-glucuronidase gene at both γ134.5 loci. Δ34.5-(IE)Us11 virus contains an additional 583-bp deletion spanning the US-TR junction, removing the Us11 promoter along with most of the Us12 ORF, including the initiation codon, andresulting in the production of an IE mRNA that initiates from the Us12 promoter and that encodes the Us11 polypeptide. The ΔUs11 and pAUs11 mutations both insert the EGFP ORF and SV40 polyadenylation signal downstream of the Us11 promoter and Us12 stop codon, such that the Us12 ORF remains intact and the EGFP ORF is expressed from the Us11 promoter. The ΔUs11 mutation inserts the EGFP ORF and SV40 polyadenylation signal in place of the Us11 ORF, resulting in the complete removal of Us11 coding sequences from the virus and the disruption of the Us10 ORF, whereas the pAUs11 mutation, which places the EGFP ORF and SV40 polyadenylation signal upstream of the Us11 ORF, creates a Us11 null allele by polyadenylating transcripts before they reach the Us11 ORF. This eliminates the production of an mRNA capable of encoding the Us11 protein and preserves the integrity of the Us10 ORF and its promoter.

Two types of Us11 mutations were introduced into the HSV-1 genome (Fig. 1B). The first allele, referred to as ΔUs11, replaces the Us11 coding sequences, as well as portions of the 5′ and 3′ noncoding regions, with the EGFP ORF and SV40 polyadenylation signal. Unfortunately, deletion of Us11 also results in a loss-of-function mutation in the overlapping Us10 ORF. To engineer a Us11 null allele without affecting Us10 coding sequences, we inserted the EGFP ORF fused to the SV40 polyadenylation signal between the Us11 transcriptional start site and AUG codon, downstream of the Us12 stop codon. This design, which produces pAUs11, creates a Us11 null virus because mRNA that initiates from the Us11 promoter expresses GFP and is polyadenylated before it reaches the Us11 coding sequences. Thus, although Us11 coding sequences are present in the viral genome, they are not transcribed. Furthermore, expression of both the Us12 and Us10 genes is unaffected, although the Us12 mRNA is polyadenylated at the poly(A+) signal introduced downstream of the EGFP ORF.

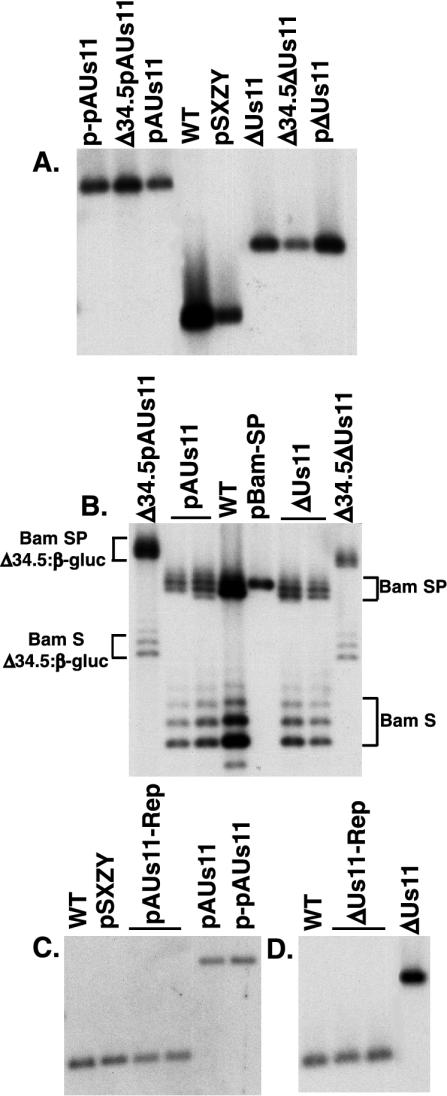

The mutant Us11 targeting constructs were cotransfected into Vero cells along with infectious Δ34.5 viral DNA to create, by homologous recombination, viruses deficient for both γ134.5 and Us11 function (Δ34.5pAUs11 and Δ34.5ΔUs11; Table 1). Following multiple rounds of plaque purification to isolate GFP-positive recombinants, the genomic structure of the viruses was evaluated by Southern analysis. Viral DNA from Δ34.5pAUs11 and Δ34.5ΔUs11 was isolated, digested with EcoNI, fractionated by agarose gel electrophoresis, blotted onto a nylon membrane, and hybridized to a labeled NcoI-EcoNI probe from the Us10 ORF (Fig. 1A). EcoNI fragments in Δ34.5pAUs11 and Δ34.5ΔUs11 viral DNA that hybridize to the probe comigrate with their respective fragments contained within the targeting plasmids p-pAUs11 and pΔUs11, indicating that the plasmid-borne Us11 mutations were introduced into both recombinant viruses (Fig. 2A). To verify that both recombinants retained the original Δ34.5 allele in which β-glucuronidase coding sequences replaced the γ134.5 gene, viral DNA from Δ34.5pAUs11 and Δ34.5ΔUs11 was isolated, digested with BamHI, fractionated by agarose gel electrophoresis, blotted onto a nylon membrane, and hybridized to a labeled BamHI-BstXI probe from pBamSP. This probe does not contain any γ134.5 gene sequences but hybridizes to the BamHI S and SP fragments, which each contain a copy of the γ134.5 gene in the WT virus. The BamHI S and SP fragments in Δ34.5pAUs11 and Δ34.5ΔUs11 migrate slower than those of the WT (Fig. 2B), as they contain the larger β-glucoronidase coding sequences in place of the γ134.5 gene and have therefore retained the original Δ34.5 allele. The characteristic laddering appearance of BamHI S and SP fragments following fractionation by agarose gel electrophoresis is due to natural variation in the number of internal, short, repetitive DNA sequences.

TABLE 1.

Genetic lineage of recombinant viruses used in this studya

| Viral genotype | Progenitor | Construction strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Δ34.5 | WT | Both γ134.5 alleles replaced with β-glucuronidase gene |

| Δ34.5-(IE)Us11 | Δ34.5 | Spontaneous mutation resulting in the expression of Us11 from the Us12 IE promoter |

| Δ34.5ΔUs11 | Δ34.5 | Replace Us11 ORF with GFP ORF |

| Δ34.5pAUs11 | Δ34.5 | Insert the GFP ORF, fused to a poly (A+) site, immediately downstream of the Us11 late promoter |

| ΔUs11 | Δ34.5ΔUs11 | Repair γ134.5 gene |

| pAUs11 | Δ34.5pAUs11 | Repair γ134.5 gene |

| ΔUs11-Rep | ΔUs11 | Repair the Us11 mutation |

| pAUs11-Rep | pAUs11 | Repair the Us11 mutation |

After first introducing the Us11 mutant alleles into a γ134.5 mutant background and isolating the resulting viral double mutants (as depicted in Fig. 1B), the γ134.5 mutation was repaired to WT and viruses containing only the ΔUs11 mutation or the pAUs11 mutation were isolated. The Us11 mutations were subsequently repaired to generate gentoypically WT viruses. The isolation of viruses in which the introduced mutations were repaired to their WT state ensures that any phenotypes observed are due to the introduced mutations rather than secondary, cryptic mutations.

FIG. 2.

Physical structure of mutant loci in HSV-1 recombinants. (A) EcoNI-digested viral and plasmid DNAs were fractionated by electrophoresis in agarose gels, transferred to nylon membranes, and incubated with a 32P-labeled EcoNI-NcoI DNA probe that detects the Us10-to-Us12 region. The washed membrane was subsequently exposed to Kodak XAR film. (B) Viral and plasmid DNAs were digested with BamHI, fractionated by agarose gel electrophoresis, transferred to nylon membranes, and incubated with a 32P-labeled BamHI-BstXI probe derived from the BamHI SP fragment DNA probe. The washed filter was exposed to Kodak XAR film. This probe hybridizes to a segment adjacent to the γ134.5 ORF in the BamHI S and SP fragments, and therefore each fragment contains either one copy of the γ134.5 gene or, for the γ134.5 deletion mutants, one copy of the β-glucuronidase (β-gluc) gene. Heterogeneity in the mobility of the BamHI S and SP fragments is due to natural variations in the length of a repetitive sequence element. (C and D) EcoNI-digested viral and plasmid DNAs were separated in agarose gels, transferred to nylon membranes, and incubated with a 32P-labeled NcoI-PflMI DNA probe that detects the Us10-to-Us12 region. After being washed, the filter was exposed to Kodak XAR film.

To create viruses deficient in only Us11 function, the γ134.5 genes in Δ34.5pAUs11 and Δ34.5ΔUs11 were repaired (Table 1). These viruses were termed pAUs11 and ΔUs11. The recombinants were enriched by two rounds of growth selection in U373 cells, which are nonpermissive for the growth of γ134.5 mutant viruses (18). Therefore, viruses that have properly recombined the γ134.5 coding sequences have a growth advantage in U373 cells. Viral DNA from pools of pAUs11 and ΔUs11 viruses selected in U373 cells was isolated, digested with BamHI, fractionated by agarose gel electrophoresis, transferred to a nylon membrane, and hybridized to a BamHI-BstXI probe from pBamSP. The BamHI S and SP fragments from pAUs11 and ΔUs11 mutants comigrated with those derived from WT virus (Fig. 2B), indicating that the γ134.5 gene was properly restored at both loci. Both pAUs11 and ΔUs11 still contained the proper Us11 mutations because EcoNI fragments that hybridize to a labeled NcoI-EcoNI probe from the Us10 ORF exhibited an electrophoretic mobility indistinguishable from that of fragments derived from the targeting plasmids p-pAUs11 and pΔUs11 (Fig. 2A). Southern blots of DNA isolated from plaque-purified pAUs11 and ΔUs11 viruses exhibited similar results (data not shown).

The Us11 mutations were then repaired to create the viruses pAUs11-Rep and ΔUs11-Rep, each of which is genotypically WT (Table 1). Provided that the Us11-Rep viruses behave similarly to the WT, this repair strategy verifies that any phenotypes associated with the loss of either γ134.5, Us11, or both are due to the introduced mutations rather than secondary, cryptic mutations. Infectious viral DNA prepared from plaque-purified pAUs11 and ΔUs11 mutant viruses was cotransfected into Vero cells with the plasmid pSXZY, which contains a WT Us11 gene, to create the pAUs11-Rep and ΔUs11-Rep viruses. Experiments involving competition in U373 cells coinfected with a Us11 null virus and a comparably small amount of WT virus revealed that the WT virus could, after several passages, constitute approximately one-half of the overall viral population (M. Mulvey and I. Mohr, unpublished observations). The growth advantage exhibited by WT HSV-1 relative to the Us11 null mutant suggested that cell-free lysates prepared from Vero cells transfected with pAUs11 or ΔUs11 viral DNA along with the pSXZY plasmid could be passaged in U373 cells to enrich for recombinant viruses in which the Us11 mutations were repaired. After enrichment for recombinants, plaques were randomly picked and assayed for Us11 expression. Positive isolates were subjected to a second round of plaque purification, and viral DNA was isolated, digested with EcoNI, fractionated by agarose gel electrophoresis, transferred to a nylon membrane, and hybridized to a labeled NcoI-PflMI fragment from the Us10 ORF (Fig. 1A). Figure 2C demonstrates that the hybridizing EcoNI fragment from pAUs11-Rep comigrates with the equivalent fragment derived from WT virus and the WT gene in the targeting plasmid pSXZY. It does not, however, comigrate with the corresponding fragment from the pAUs11 mutant virus, indicating that the mutation was indeed successfully repaired. Likewise, repair of the mutant Us11 allele in the ΔUs11 virus was also successful, as the hybridizing EcoNI fragment in ΔUs11-Rep comigrates with the equivalent fragment in WT virus but does not comigrate with the corresponding fragment in the ΔUs11 mutant virus (Fig. 2D).

Maintenance of WT translation rates from the onset of DNA synthesis into the initial segment of the late phase requires the γ134.5, but not the Us11, gene product.

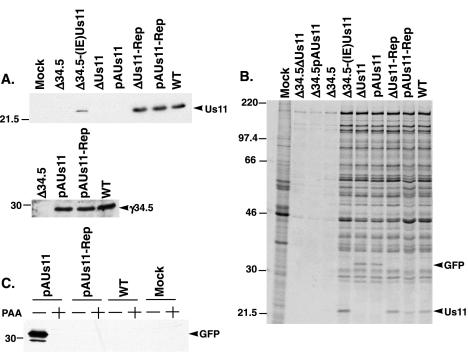

Because cells infected with γ134.5 mutant viruses prematurely arrest viral protein synthesis before γ2 mRNAs can be translated, they are effectively deficient for not only γ134.5 function but also that of all γ2 gene products. For this reason, the contribution of γ134.5 to the rates of viral protein synthesis at late times of infection may be overestimated. Figures 3 and 4 provide a direct comparison of the individual contributions of the γ134.5 and Us11 proteins to the rates of viral translation at various stages of the viral life cycle. Although the Δ34.5-(IE)Us11 virus is deficient for γ134.5 protein function, it expresses the Us11 protein as an IE protein, presumably before PKR activation (Fig. 3A). Because this virus expresses the Us11 protein as the sole known viral regulator of the PKR-eIF2α signaling pathway, the contribution of the Us11 protein to the rates of viral protein synthesis, growth, PKR activation, and eIF2α phosphorylation can be directly assessed. Furthermore, the pAUs11 and ΔUs11 viruses provide a direct measure of the contribution of the γ134.5 gene product to rates of translation, PKR activation, eIF2α phosphorylation, and viral growth because they cannot produce the Us11 protein. Instead, cells infected with pAUs11 or ΔUs11 synthesize the γ134.5 protein and it accumulates to WT levels (Fig. 3A). Therefore, by comparing the rates of translation of the Δ34.5-(IE)Us11 and the Us11 null viruses, the relative abilities of the Us11 and γ134.5 proteins to regulate the PKR-eIF2α signaling pathway can be evaluated directly.

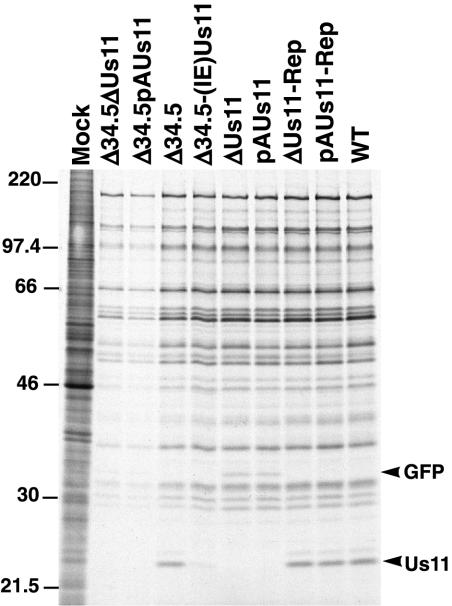

FIG. 3.

The γ134.5 protein, rather than the Us11 polypeptide, perpetuates the translation of viral proteins through the initial segment of the late phase. (A) U373 cells were either mock infected or infected at an MOI of 5, and the cells were lysed in SDS-containing buffer at 19 h postinfection. The abundances of the Us11 and γ134.5 gene products were determined by immunoblotting. (B) U373 cells were either mock infected or infected at an MOI of 5 and incubated for 1 h with [35S]cysteine and [35S]methionine beginning at 6 h postinfection, at which time whole-cell SDS lysates were prepared. The lysates were fractionated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, fixed, dried, and exposed to Kodak XAR film. (C) Untreated or PAA-treated U373 cells were either mock infected or infected at an MOI of 5, and whole-cell SDS lysates were prepared at 14 h postinfection. The amount of GFP in the lysates was evaluated by immunoblotting.

FIG. 4.

The Us11 protein is required for WT translation rates late in the viral life cycle. (A) U373 cells were either mock infected or infected at an MOI of 5, incubated with [35S]cysteine and [35S]methionine for 1 h beginning at 18 h postinfection, and then solubilized in SDS-containing buffer. The lysates were fractionated by electrophoresis in SDS-polyacrylamide gels, fixed, dried, and exposed to Kodak XAR film. (B) Translation rates observed in panel A were quantified by precipitating the protein samples with TCA. Acid-insoluble radioactivity was collected on GF-C filters, and the counts incorporated were determined by liquid scintillation counting. The results of three independent experiments are presented. (C) Untreated or PAA-treated U373 cells were either mock infected or infected, labeled, and analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis as described for panel A except that the labeling was performed at 13 h postinfection.

To examine the rates of protein synthesis at an early point in the viral life cycle, U373 cells were mock infected or infected at high multiplicity with either a γ134.5-Us11 double mutant, a γ134.5 mutant, a Us11 mutant, or WT virus. At 6 h postinfection, newly synthesized proteins were labeled for 1 h with 35S-labeled amino acids and total protein was isolated and fractionated in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gels. Additionally, translation rates were quantified by liquid scintillation counting of TCA-insoluble material in each sample. In U373 cells infected with one of the Us11 and γ134.5 double-mutant viruses (Δ34.5ΔUs11 and Δ34.5pAUs11) or the Δ34.5 virus, which does not synthesize any Us11 protein due to the translational block, protein synthesis was completely shut off at 6 h postinfection (Fig. 3B). However, viruses that expressed Us11 (Δ34.5-[IE]Us11) or γ134.5 (pAUs11 and ΔUs11) synthesized proteins at rates equivalent to WT, demonstrating that either the Us11 protein, produced as an IE protein, or the γ134.5 polypeptide is individually capable of completely inhibiting the cellular signal to arrest translation at this time of infection (Fig. 3B).

Importantly, labeled, newly synthesized Us11 protein was clearly present in cells infected with either pAUs11-Rep, ΔUs11-Rep, or WT virus at 6 h postinfection (Fig. 3B). Because transcription from the Us11 γ2 promoter requires the prior initiation of viral DNA replication, the appearance of newly synthesized Us11 protein indicates that the viral life cycle had advanced into the late phase in a significant number of infected cells. Moreover, labeled, newly synthesized GFP was similarly discernible in cells infected with either pAUs11 or ΔUs11 mutant viruses at 6 h postinfection. The GFP-encoding mRNA initiates from the natural Us11 late promoter, and GFP did not accumulate in infected cells treated with PAA (Fig. 3C), demonstrating that GFP expressed from the Us11 promoter behaves as a γ2 polypeptide. The synthesis of GFP in cells infected with either ΔUs11 or pAUs11 suggests that some cells in each population entered into the late phase of the infectious program as well. If Us11 were required to regulate the rates of protein synthesis during viral DNA replication and into the initial stages of the late phase, then we would not see significant labeling of GFP in cells infected with pAUs11 or ΔUs11. Therefore, the production of GFP as a true late protein at 6 h postinfection in these infected cells indicates that the γ134.5 protein, as opposed to the Us11 polypeptide, functions to promote WT rates of protein synthesis from the onset of viral DNA replication into the initial stages of the late phase.

Us11 is required for wild-type translation rates at late times in the viral life cycle.

Examination of translation rates at 18 h postinfection reveals that cells infected with the Us11 mutant pAUs11 or ΔUs11, both of which express the γ134.5 polypeptide, synthesized proteins at rates six- to sevenfold lower than cells infected with a virus that expressed both γ134.5 and Us11 (WT, pAUs11-Rep, or ΔUs11-Rep). Some of the plaques picked after enriching for ΔUs11-Rep and pAUs11-Rep recombinants remained Us11 negative and continued to translate late proteins at reduced rates in infected cells, suggesting that repairing the mutant Us11 allele, as opposed to the enrichment step in and of itself, was responsible for the restored late translation rates observed in cells infected with either of the repaired viruses (M. Mulvey and I. Mohr, unpublished observations). In addition, cells infected with either of the two Us11 mutants synthesized proteins at rates approximately twofold lower than cells infected with Δ34.5-(IE)Us11, a virus that lacks the γ134.5 gene but instead expresses Us11 at IE times (Fig. 4A and B). Comparison of translation rates in cells infected with either Δ34.5ΔUs11, ΔUs11, or ΔUs11-Rep revealed that repairing the γ134.5 gene in the Δ34.5ΔUs11 mutant increased translation rates by a factor of approximately 5, while the repair of the Us11 mutation in ΔUs11 yielded a sixfold increase in translation rates. As rates of translation in cells infected with the double-mutant Δ34.5ΔUs11 were reduced 30-fold relative to those in cells infected with the repaired virus ΔUs11-Rep, the Us11 and γ134.5 gene products act synergistically to regulate late translation in HSV-1-infected cells. Similar results have been obtained in other transformed human cell lines as well as in primary human foreskin fibroblasts (M. Mulvey and I. Mohr, unpublished observations). Importantly, we did not observe any reduction in translation rates in Vero cells infected with Us11 mutants (Fig. 5), consistent with earlier reports which state that loss of Us11 function did not impact viral replication in this cell line (15, 29). A modest reduction in translation rates, however, was observed in Vero cells infected with viruses deficient for both γ134.5 and Us11 functions. Presumably, this is due to a low level of activated PKR that is normally efficiently counteracted by either the γ134.5 or Us11 gene products.

FIG. 5.

Vero cells support the replication of γ134.5 mutant viruses and do not require either the Us11 or γ134.5 products for WT translation rates. Vero cells were either mock infected or infected at an MOI of 5. The cells were subsequently labeled and analyzed as described in the legend to Fig. 4A.

To evaluate the contribution Us11 present in the tegument makes toward viral translation rates and to define more precisely the phase of the viral life cycle at which the Us11 protein is required to achieve proper translation rates, cells were infected in the presence of PAA, a viral DNA polymerase inhibitor, to prevent the expression of γ2 mRNAs and arrest the viral life cycle. Cells infected with pAUs11 or ΔUs11 and treated with PAA synthesized proteins at WT rates (Fig. 4C), demonstrating that the delivery of Us11 into the cytosol as a tegument protein, at times which precede viral gene expression, appears not to be required to maintain WT translation rates prior to the onset of DNA synthesis. This implicates either DNA replication or a closely linked event, such as the accumulation of γ2 mRNAs, in the reduction in translation rates observed in cells infected with Us11 mutant viruses. Thus, while the γ134.5 protein appears to play a critical role in preserving rates of protein synthesis during the early-to-late transition, the Us11 gene product emerges as a significant regulator of translation as the infection proceeds further into the late stage.

Prevention of PKR activation and inhibition of eIF2α phosphorylation late in the viral life cycle by the Us11 polypeptide.

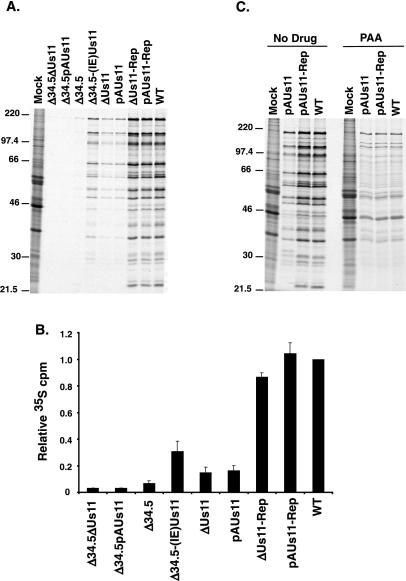

Although Us11 has been previously shown to inhibit PKR activation during viral infection, all of these studies were performed using γ134.5 mutants that expressed Us11 as an IE protein, such as Δ34.5(IE)Us11 (19). Up to this point, there have been no efforts to assess the capacity of Us11, expressed in its natural context as a true-late gene, to preclude PKR activation, as a translational-control phenotype for Us11 loss-of-function mutants was never reported. Having now established a requirement for the Us11 protein in preserving WT translation rates at late times postinfection, we sought to ascertain if it functions to mitigate PKR activation when expressed in its biological context as a true-late or γ2 polypeptide. Cell extracts were prepared from U373 cells that were mock infected or infected with either Δ34.5, a Us11 mutant, a γ134.5-Us11 double mutant, or WT virus at 18 h postinfection. Following incubation with [γ-32P]ATP for 30 min at 30°C, PKR was immunoprecipitated, the immune complexes were fractionated by electrophoresis in SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and the amount of activated, phosphorylated PKR was visualized by autoradiography. Significantly, viruses that encoded a wild-type γ134.5 gene product, yet were incapable of producing the Us11 protein, activated PKR to a similar extent as any γ134.5 mutant examined in Fig. 6A (Δ34.5, Δ34.5ΔUs11, or Δ34.5pAUs11). However, viruses in which the Us11 mutation was repaired (pAUs11-Rep and ΔUs11-Rep), allowing expression in its native context as a late gene, appeared not to activate PKR. The WT Patton strain along with a Δ34.5 mutant that expresses the Us11 protein as an IE protein were likewise able to prevent PKR activation. Us11, therefore, is required to prevent PKR activation when it is expressed in its biological context late in the viral productive-replication program.

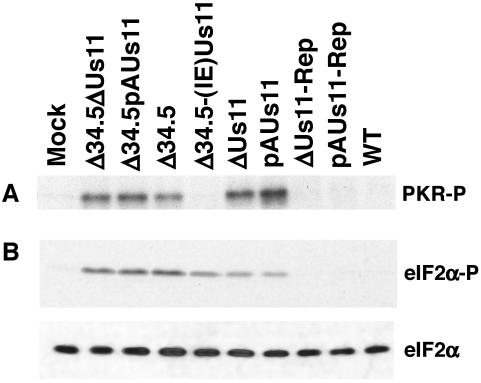

FIG. 6.

Prevention of PKR activation late in the viral life cycle requires the Us11 gene product. (A) S10 extracts from infected or mock-infected U373 cells were prepared at 18 h postinfection. After the extracts were incubated in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP, PKR activation was assessed by immunoprecipitating PKR. Immune complexes were fractionated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and the fixed, dried gel was exposed to Kodak XAR film. (B) U373 cells were infected and processed as described in the legend to Fig. 3A. The abundances of total eIF2α (bottom) and eIF2α phosphorylated on Ser 51 (top) were evaluated by immunoblotting.

To investigate the levels of phosphorylated eIF2α in cells infected with each of the Us11 mutant viruses in our panel, total protein isolated from mock-infected or infected cells was fractionated in an SDS-polyacrylamide gel, transferred to a membrane support, and incubated with antibodies directed against either phosphorylated eIF2α (Fig. 6B, top) or total eIF2α (Fig. 6B, bottom). Extracts prepared from cells infected with the Δ34.5pAUs11, Δ34.5ΔUs11, or Δ34.5 virus had high levels of PKR activity (Fig. 6A) and phosphorylated eIF2α (Fig. 6B). This reflects the inability of these mutants to produce both the γ134.5 and Us11 gene products. Reduced quantities of phosphorylated eIF2α were observed in cells infected with either ΔUs11 or pAUs11 despite amounts of activated PKR comparable to those induced by Δ34.5, Δ34.5pAUs11, or Δ34.5ΔUs11. The former mutants contain a WT γ134.5 allele and can recruit PP1α to dephosphorylate eIF2α, while the latter set of mutants is deficient for the γ134.5 gene. Repairing the Us11 mutations in pAUs11 and ΔUs11 abolished PKR activation (Fig. 6A) and reduced eIF2α phosphorylation (Fig. 6B) to undetectable levels. Finally, the increased accumulation of phosphorylated eIF2α in cells infected with certain viral mutants correlates well with the observed reductions in overall translation rates. Together, these findings indicate that the Us11 gene product is a major regulator of viral protein synthesis late in the viral life cycle, as it prevents PKR activation and cooperates in a synergistic manner with the γ134.5 gene product to inhibit the accumulation of phosphorylated eIF2α. Furthermore, the elevated levels of phosphorylated eIF2α in cells infected with a Us11 mutant virus and the subsequent reduction in eIF2α phosphorylation observed in cells infected with viruses in which the Us11 mutation was repaired indicate that the γ134.5 gene product, in and of itself, is not capable of processing all of the phosphorylated eIF2α generated by activated PKR.

The data presented in Fig. 6 might also suggest that the γ134.5 protein continues to have an impact on translation rates as the late phase progresses. While activated PKR was not observed in extracts prepared from cells infected with Δ34.5(IE)Us11 at late times postinfection (Fig. 6A), the virus did not synthesize proteins at WT rates (Fig. 4B), and relatively high levels of phosphorylated eIF2α, in comparison to those seen in cells infected with WT virus, were present (Fig. 6B). In the absence of the γ134.5 protein, the virus cannot harness the PP1α phosphatase (11), and it is possible that eIF2α kinases other than PKR catalyze these phosphorylation events.

Both Us11 and γ134.5 are required for WT rates of growth on U373 cells.

To investigate the impact of removing Us11 function in viral growth in cells that possess the capacity to launch an antiviral response, thus inhibiting translation, U373 cells were infected at low multiplicity of infection (MOI; 10−3) with WT virus or each of the individual mutants. Figure 7A illustrates that the γ134.5-Us11 double mutants (Δ34.5pAUs11 and Δ34.5ΔUs11) were the most impaired, achieving titers that were between 10- and 100-fold reduced compared to those for the Δ34.5 mutant, which multiplied to titers 104- to 105-fold less than those attained by WT virus. It is interesting that the incorporation of the Us11 mutant allele into the Δ34.5 genetic background further reduced replication, since the Us11 γ2 mRNA was not translated in Δ34.5-infected cells. The further reduction in viral replication might possibly reflect the loss of the Us11 protein from the viral tegument.

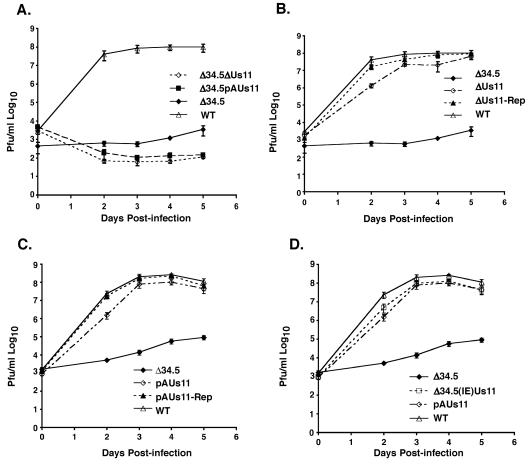

FIG. 7.

WT growth rates in U373 cells require both the Us11 and γ134.5 gene products, although either function on its own supports equivalent levels of viral replication. U373 cells were infected in triplicate at an MOI of 10−3. At 2, 3, 4, and 5 days postinfection lysates were prepared by freeze-thawing and titered in permissive Vero cells. (A) Comparison of Δ34.5ΔUs11, Δ34.5pAUs11, Δ34.5, and WT. (B) Comparison of Δ34.5, ΔUs11, ΔUs11-Rep, and WT. (C) Comparison of Δ34.5, pAUs11, pAUs11-Rep, and WT. (D) Comparison of Δ34.5, Δ34.5-(IE)Us11, pAUs11, and WT. Δ34.5-(IE)Us11 lacks the γ134.5 gene but expresses the Us11 protein as an IE protein. pAUs11 does not produce the Us11 protein but contains a WT γ134.5 gene. Thus, the Us11 and γ134.5 gene products are equally capable of fostering viral replication in cultured cells.

The Us11 single-mutant viruses, ΔUs11 and pAUs11, grew at slower rates than their counterparts with repaired Us11 alleles or WT virus. In Fig. 7B, ΔUs11 and ΔUs11-Rep begin at equivalent titers on day 0, yet by day 2 the titer of ΔUs11 was reduced approximately 13-fold relative to that of ΔUs11-Rep. In fact, ΔUs11 required an extra day to reach titers analogous to those of a corresponding virus (ΔUs11-Rep) in which the Us11 mutant allele was repaired (Fig. 7B). Likewise, pAUs11 also requires a longer time to achieve titers comparable to those of pAUs11-Rep (Fig. 7C), indicating that the Us10 mutation in ΔUs11 does not contribute to this phenotype. The reduced late translation rates measured in cells infected with Us11 mutant viruses therefore correlate with the observed decrease in viral growth. Despite the fact that both the Us11 and γ134.5 gene products were both required to maintain viral translation rates at WT levels, the loss of the γ134.5 gene was associated with a larger reduction in viral replication. It is likely that this difference is accounted for by the ability of cells infected with a Us11 null mutant to synthesize limited quantities of γ2 polypeptides while cells infected with a γ134.5 mutant virus failed to produce γ2 proteins, one of which is the Us11 gene product.

Finally, although both Us11 and γ134.5 are clearly required at discrete times to sustain WT rates of protein synthesis and achieve WT levels of replication in cultured cells, it is possible to engineer viruses that contain only one of these functions and that suffer only a modest reduction in growth. The Δ34.5(IE)Us11 mutant, which lacks the γ134.5 gene but instead overexpresses Us11 as an IE gene, multiplied at rates similar to a those for a Us11 mutant virus (pAUs11) that expresses the γ134.5 protein (Fig. 7D). Thus, despite the fact that each function is designed to act at a particular point in the viral life cycle to preserve WT translation rates, each is capable of independently fostering viral replication in cultured cells. For Us11, this requires altering its time of expression from very late in the replicative cycle to extremely early. Moreover, since the Us11 protein produced at IE times accumulates to levels far below those observed when it is expressed in its natural context as a viral late protein, our results may in fact underrepresent the potential of Us11 to foster viral replication.

DISCUSSION

Currently, two HSV-1 gene products have the ability to regulate eIF2α phosphorylation (reviewed in reference 27); however, until now it was not known if these functions are simply redundant or if they fulfill unique roles at discrete times in the productive replication cycle. Expressed with the kinetics of a γ1 gene, the γ134.5 protein binds the cellular PP1α and promotes the dephosphorylation of phosphorylated eIF2α (11). γ134.5 mutants cannot complete their life cycle in a variety of cultured cells due to the accumulation of phosphorylated eIF2α, resulting in the premature cessation of protein synthesis (7). Us11, on the other hand, is normally expressed as a γ2 or true-late gene (13), but mutations that cause its product to be expressed as an IE polypeptide allow translation to proceed in the absence of the γ134.5 protein (17, 19), as the Us11 protein prevents PKR activation (5, 19). Significantly, the ability of the Us11 protein to regulate translation when expressed in its natural context as a late viral protein has not been explored previously. Through the use of a panel of viruses containing different combinations of γ134.5 and Us11 mutant alleles, we demonstrate that the translational shutoff observed in cells infected with a γ134.5 mutant virus actually results from the combined loss of γ134.5 and Us11 gene functions. Moreover, the Us11 protein is required for WT rates of protein synthesis late in the viral life cycle, while the γ134.5 protein operates to regulate translation commencing at the onset of DNA synthesis into the initial stages of the late phase. This is the first demonstration that the Us11 protein, expressed in its natural context as a late viral protein, can regulate protein synthesis and the first description of a reduction in viral replication associated with a loss-of-function Us11 allele.

Earlier studies that characterized viruses with Us11 mutations did not report any deleterious effects on viral replication (1, 4, 15, 29). The only phenotype associated with the loss of Us11 protein function was the enhanced accumulation of two viral RNA molecules: the UL13 mRNA (1) and a truncated RNA of unknown function derived from the UL34 gene (25). Our findings demonstrate a role for the Us11 protein, expressed in its natural context, in viral replication as an important regulator of overall viral late translation rates; this role may have gone unnoticed in earlier studies, as some of the cell lines used support the growth of γ134.5 mutants.

A similar reinvestigation into the pathogenesis of Us11 mutant viruses in mice, using a well defined Us11 mutant along with a virus in which the mutant allele has been repaired, is also warranted. While in vivo studies with mice were unable to associate a significant phenotype with a Us11 mutation, they did describe small effects on neurovirulence and neuroinvasiveness (20). Unfortunately, the N38 Us11 mutant virus contained a large deletion affecting several ORFs, and control repair viruses were not generated, making it difficult to appreciate the significance of the small effects reported. In addition, although the N38 Us11 mutant could establish latent infections in mice and reactivate, the efficiency with which latency was established and reactivation occurred was not determined, nor was a dose-response analysis performed, making it premature to conclude that the penetrance of the Us11 mutant phenotype might be discernible only in the human host with which it coevolved.

While Us11 and γ134.5 proteins are equally capable of inhibiting translational arrest by host defenses, our studies suggest that γ134.5 and Us11 do not simply encode redundant functions, each capable of preventing the accumulation of phosphorylated eIF2α. Instead, we establish that the two HSV-1 functions designed to regulate eIF2α phosphorylation appear to act at discrete times in the replication program. As PKR activation results in the premature cessation of protein synthesis in cells infected with a γ134.5 mutant virus, the Us11 mRNA, along with all other γ2 transcripts, is not translated (7). PKR therefore is activated prior to the synthesis of the Us11 polypeptide, suggesting that the γ134.5 protein is required to maintain sufficient levels of unphosphorylated, active eIF2α during the period that precedes the accumulation of the Us11 protein. Indeed, our analysis demonstrates that the γ134.5 protein counteracts the deleterious effects of activated PKR from the onset of viral DNA synthesis through the initial portion of the late phase. It is only once the viral replicative program has progressed further into the late phase that the Us11 protein emerges as a major regulator of PKR signaling and viral translation.

In addition to eliminating the production of Us11 as a viral late polypeptide, Us11 null mutants assemble viral particles that do not contain any Us11 protein. As a tegument component, approximately 600 to 1,000 molecules of the Us11 protein per virion are delivered into the cytosol of the infected cell prior to the expression of viral IE genes (26). However, the quantity of tegument-derived Us11 protein delivered to cells infected with a γ134.5-deficient virus at an MOI of 100 was not sufficient to prevent the premature termination of translation that occurs in the absence of the γ134.5 polypeptide (7), suggesting that Us11 protein released from the tegument upon infection cannot prevent PKR activation. Furthermore, in our study, WT translation rates in PAA-treated cells infected with a Us11 null mutant were observed, suggesting that Us11 protein within the tegument is not required for WT translation rates early in infection. While the precise role of the Us11 protein within the tegument remains to be defined, it is possible that its presence within the viral particle reflects functions unrelated to translational control (2, 9).

The differential requirement for Us11, as opposed to γ134.5, to sustain WT translation rates at late times implies that intracellular conditions resulting in PKR activation late in infection might be fundamentally different from those existing when the onset of DNA synthesis marks entry into the initial segment of the late phase. While IE and early genes are transcribed from predominately nonoverlapping transcription units evenly spaced throughout the genome, late mRNAs are produced from overlapping transcription units on opposite DNA strands and have the potential to generate copious quantities of dsRNA (12). Increasing the dsRNA concentration would in turn accelerate the rate of PKR activation (Fig. 8). Translation of the Us11 protein, a dsRNA binding protein (14), coincides with the accumulation of late mRNA, and might conceivably intercept the dsRNA, averting its detection by PKR (Fig. 8). In the absence of the Us11 protein, the abrupt accrual of dsRNA might result in levels of activated PKR and phosphorylated eIF2α that overwhelm the capabilities of the γ134.5-PP1α complex, accounting for the decrease in rates of late protein synthesis observed in cells infected with Us11 mutant viruses. In addition, the Us11 protein inhibits PKR activation by PACT, a cellular polypeptide that can activate PKR in the absence of dsRNA, and can prevent PACT-induced apoptosis (22). While PACT can activate PKR in response to a diverse array of stress stimuli, its contribution to the level of PKR activation observed in HSV-1-infected cells remains to be evaluated. Nevertheless, it remains formally possible that PACT contributes significantly to PKR activation in HSV-1-infected cells and that the Us11 protein is required to counteract PKR activation by both dsRNA and PACT. Thus, the multiple functions carried by HSV-1 to prevent eIF2α phosphorylation may have arisen in response to specific ligands that activate the cellular antiviral response at discrete points in the replicative cycle.

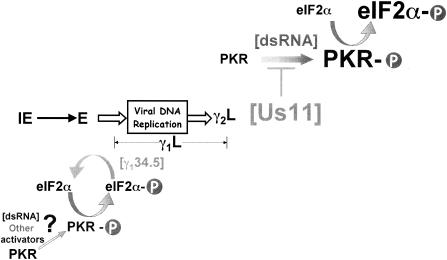

FIG. 8.

Proposed model illustrating that HSV-1 regulates eIF2α phosphorylation by discrete mechanisms at different points in the viral life cycle. Following an encounter with PACT or small quantities of dsRNA or perhaps other effectors that remain to be identified, the normally dormant cellular PKR kinase becomes activated. This entails the assembly of a PKR dimer, whereupon each subunit phosphorylates the other (PKR-P). Since PKR is activated in cells infected with a γ134.5 mutant virus, preventing the translation of γ2 mRNAs, we propose that the γ134.5 gene product, through its interaction with PP1α, is able to adequately dephosphorylate the quantities of phosphorylated eIF2α (eIF2α-P) produced from the period preceding the initiation of viral DNA synthesis and extending into the initial segment of the late phase (designated γ1L). However, late in the viral life cycle, the activation of γ2 genes (γ2L), many of which are transcribed from ORFs located on opposing DNA strands, results in the production of large quantities of viral dsRNA. In the absence of Us11, the increase in dsRNA concentration generates more activated PKR, which in turn phosphorylates eIF2α. The concentration of phosphorylated eIF2α quickly rises to a level beyond that at which the γ134.5-PP1α complex can effectively reverse the reaction, accounting for the observed reduction in viral translation rates in cells infected with a Us11 mutant virus. We suggest that, while the γ134.5 protein acts downstream of phosphorylated eIF2α and therefore has the potential to counter a variety of eIF2α kinases, the Us11 protein acts late in infection to specifically antagonize PKR activation in response to the copious levels of dsRNA produced in virus-infected cells. Relative concentrations of PKR-P, dsRNA, and eIF2α-P at early, compared to later, times in the viral life cycle are represented by character size.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rich Roller, Bernard Roizman, and Michael Clemens for antisera, David Khoo for technical assistance, and both reviewers for their helpful comments on the manuscript.

This work was funded by a grant from the NIH to I.M. M.M. was supported, in part, by NIH training grants to the Department of Microbiology, NYU School of Medicine (T32 AI0718021), and a joint institutional training award in virus-host interactions to Mount Sinai School of Medicine and NYU School of Medicine (T32 AI07647).

REFERENCES

- 1.Attrill, H. L., S. A. Cumming, J. B. Clements, and S. V. Graham. 2002. The herpes simplex virus type 1 US11 protein binds the coterminal UL12, UL13, and UL14 RNAs and regulates UL13 expression in vivo. J. Virol. 76:8090-8100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benboudjema, L., M. Mulvey, Y. Gao, S. Pimplikar, and I. Mohr. 2003. Association of the herpes simplex virus type-1 Us11 gene product with the cellular kinesin light-chain related protein PAT1 results in the redistribution of both polypeptides. J. Virol. 77:9192-9203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolovan, C. A., N. M. Sawtell, and R. L. Thompson. 1994. ICP34.5 mutants of herpes simplex virus type 1 strain 17syn+ are attenuated for neurovirulence in mice and for replication in confluent primary mouse embryo cell cultures. J. Virol. 68:48-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown, S. M., and J. Harland. 1987. Three mutants of herpes simplex virus type 2: one lacking the genes US10, US11 and US12 and two in which Rs has been extended by 6 kb to 0.91 map units with loss of Us sequences between 0.94 and the Us/TRs junction. J. Gen. Virol. 68:1-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cassady, K. A., and M. Gross. 2002. The herpes simplex virus type 1 Us11 protein interacts with protein kinase R in infected cells and requires a 30-amino-acid sequence adjacent to a kinase substrate domain. J. Virol. 76:2029-2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chou, J., E. R. Kern, R. J. Whitley, and B. Roizman. 1990. Mapping of herpes simplex virus-1 neurovirulence to gamma (1) 34.5, a gene nonessential for growth in culture. Science 250:1262-1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chou, J., and B. Roizman. 1992. The γ34.5 gene of herpes simplex virus 1 precludes neuroblastoma cells from triggering total shutoff of protein synthesis characteristic of programmed cell death in neuronal cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:3266-3270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chou, J., and B. Roizman. 1994. Herpes simplex virus 1 gamma(1)34.5 gene function, which blocks the host response to infection, maps in the homologous domain of the genes expressed during growth arrest and DNA damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:5247-5251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diefenbach, R. J., M. Miranda-Saksena, E. Diefenbach, D. J. Holland, R. A. Boadle, P. J. Armati, and A. L. Cunningham. 2002. Herpes simplex virus tegument protein US11 interacts with conventional kinesin heavy chain. J. Virol. 76:3282-3291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He, B., M. Gross, and B. Roizman. 1997. The gamma(1)34.5 protein of herpes simplex virus 1 complexes with protein phosphatase 1 alpha to dephosphorylate the alpha subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 and preclude the shutoff of protein synthesis by double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:843-848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He, B., M. Gross, and B. Roizman. 1998. The gamma(1) 34.5 protein of herpes simplex virus 1 has the structural and functional attributes of a protein phosphatase 1 regulatory subunit and is present in a high molecular weight complex with the enzyme in infected cells. J. Biol. Chem. 273:20737-20743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacquemont, B., and B. Roizman. 1975. RNA synthesis in cells infected with herpes simplex virus. X. Properties of viral symmetric transcripts and of double-stranded RNA prepared from them. J. Virol. 15:707-713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson, P. A., C. MacLean, H. S. Marsden, R. G. Dalziel, and R. D. Everett. 1986. The product of gene US11 of herpes simplex virus type 1 is expressed as a true late gene. J. Gen. Virol. 67:871-883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khoo, D., C. Perez, and I. Mohr. 2002. Characterization of RNA determinants recognized by the arginine- and proline-rich region of Us11, a herpes simplex virus type 1-encoded double-stranded RNA binding protein that prevents PKR activation. J. Virol. 76:11971-11981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Longnecker, R., and B. Roizman. 1986. Generation of an inverting herpes simplex virus 1 mutant lacking the L-S junction a sequences, an origin of DNA synthesis, and several genes including those specifying glycoprotein E and the α47 gene. J. Virol. 58:583-591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maclean, A. R., M. Ul-Fareed, L. Robertson, J. Harland, and S. M. Brown. 1991. Herpes simplex virus type 1 deletion variants 1714 and 1716 pinpoint neurovirulence-related sequences in Glasgow strain 17+ between immediate early gene 1 and the "a' sequence. J. Gen. Virol. 72:631-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohr, I., and Y. Gluzman. 1996. A herpesvirus genetic element which affects translation in the absence of the viral GADD34 function. EMBO J. 15:4759-4766. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohr, I., D. Sternberg, S. Ward, D. Leib, M. Mulvey, and Y. Gluzman,. 2001. A herpes simplex virus type 1 γ34.5 second-site suppressor mutant that exhibits enhanced growth in cultured glioblastoma cells is severely attenuated in animals. J. Virol. 75:5189-5196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mulvey, M., J. Poppers, A. Ladd, and I. Mohr. 1999. A herpesvirus ribosome associated, RNA-binding protein confers a growth advantage upon mutants deficient in a GADD34-related function. J. Virol. 73:3375-3385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishiyama, Y., R. Kurachi, T. Daikoku, and K. Umene. 1993. The Us 9, 10, 11, and 12 genes of herpes simplex virus type 1 are of no importance for its neurovirulence and latency in mice. Virology 194:419-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pe'ery, T., and M. B. Mathews. 2000. Viral translational strategies and host defense mechanisms, p. 371-424. In N. Sonenberg, J. W. B. Hershey, and M. B. Mathews (ed.), Translational control. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 22.Peters, G. A., D. Khoo, I. Mohr, and G. C. Sen. 2002. Inhibition of PACT-mediated activation of PKR by the herpes simplex virus type 1 Us11 protein. J. Virol. 76:11054-11064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poppers, J., M. Mulvey, C. Perez, D. Khoo, and I. Mohr. 2003. Identification of a lytic-cycle Epstein-Barr virus gene product that can regulate PKR activation. J. Virol. 77:228-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roizman, B., and D. M. Knipe. 2001. Herpes simplex viruses and their replication, p. 2399-2460. In D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, D. E. Griffin, R. A. Lamb, M. A. Martin, B. Roizman, and S. E. Straus (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed., vol. 2. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 25.Roller, R. J., and B. Roizman. 1991. Herpes simplex virus 1 RNA binding protein US11 negatively regulates the accumulation of a truncated viral mRNA. J. Virol. 65:5873-5879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roller, R. J., and B. Roizman. 1992. The herpes simplex virus 1 RNA binding protein Us11 is a virion component and associates with 60S ribosomal subunits. J. Virol. 66:3624-3632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schneider, R. J., and I. Mohr. 2003. Translation initiation and viral tricks. Trends Biochem. Sci. 28:130-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scorsone, K. A., R. Panniers, A. G. Rowlands, and E. C. Henshaw. 1987. Phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 during physiological stresses which affect protein synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 262:14538-14543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Umene, K. 1986. Conversion of a fraction of the unique sequence to part of the inverted repeats in the S component of the herpes simplex virus type 1 genome. J. Gen. Virol. 67:1035-1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang, Y. L., L. F. Reis, J. Pavlovic, A. Aguzzi, R. Schafer, A. Kumar, B. R. Williams, M. Aguet, and C. Weissmann. 1995. Deficient signaling in mice devoid of double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase. EMBO J. 14:6095-6106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]