Abstract

In spite of its broad host range, adenovirus type 5 (Ad5) transduces a number of clinically relevant tissues and cell types inefficiently, mostly because of low expression of the coxsackievirus-adenovirus receptor (CAR). To improve gene transfer to such cells, we modified the Ad5 fiber knob to recognize novel receptors. We expressed a functional Ad5 fiber knob domain on the capsid of phage λ and employed this display system to construct a large collection of ligands in the HI loop of the Ad5 knob. Panning this library on the CAR-negative mouse fibroblast cell line NIH 3T3 resulted in the identification of three clones with increased binding to these cells. Adenoviruses incorporating these ligands in the fiber gene transduced NIH 3T3 cells 2 or 3 orders of magnitude better than the parent vector. The same nonnative tropism was revealed in other cell types, independently of CAR expression. These Ad5 derivatives proved capable of transducing mouse and human primary immature dendritic cells with up to 100-fold increased efficiency.

Replication-deficient adenovirus type 5 (Ad5) is an efficient and versatile gene delivery vector that has been widely used for a variety of gene therapy applications in vitro and in vivo (33). Ad5 efficiently infects a broad range of target cells, including dividing and quiescent cells. However, several cell types and tissues which represent important targets for gene therapy are refractory to Ad5 infection, mainly because of low coxsackievirus-adenovirus receptor (CAR) expression levels. These include endothelium, smooth and adult skeletal muscle, brain tissue, differentiated airway epithelial tissue, primary tumors, and hematopoietic cells (5, 7, 22, 26, 30, 36, 41, 45). In particular, inefficient gene transfer has been documented for dendritic cells (DC) (46). Thus, considerable effort has been directed at increasing the efficiency of adenovirus delivery to these therapeutically relevant human cells and tissues.

The Ad5 cellular entry mechanism is composed of two separate and uncoupled events. First, the virus binds to the host cell through a high-affinity interaction between the trimeric carboxy-terminal knob domain of the viral fiber proteins and CAR displayed on the cell surface (39). This primary interaction, which dictates the infectivity of the virus, is followed by the association of RGD sequences in the penton base with αVβ3 and αVβ5 integrins on the cell surface, thereby activating internalization of the virus (40). Strategies to alter Ad5 tropism mainly focus on the first step of this cellular transduction process by genetically modifying the viral fiber knob domain to permit the recognition of novel receptors on target cells (20). Many laboratories have shown that it is possible to partially or completely replace the Ad5 fiber gene with that of a different Ad serotype, generating a tropism derived from the donor serotype (31). Indeed, some of the Ad5 chimeras that have been created exhibit enhanced tropism for defined cell types. However, the flexibility of this “fiber-swapping” approach is hampered by the number of serotypes available and their limited tropism. For example, it is unlikely that an adenovirus that binds tumor cells has evolved naturally. In addition, impaired viability and reduced yield of the viral chimeras have held back wide exploitation of this strategy (16).

Curiel and coworkers have shown that the HI loop, the region connecting the β strands H and I, which protrudes from the Ad5 fiber knob, structurally and functionally tolerates the insertion of various peptide sequences up to 83 amino acids (20). These findings prompted the screening of phage-displayed peptide libraries to identify ligands with the desired binding specificity. However, these ligands often do not retain their binding properties when grafted into a different protein location, i.e., the HI loop of the Ad5 knob (28). Furthermore, insertion of specific peptide sequences can affect fiber trimerization, CAR binding function, and virus assembly (42).

To overcome these limitations, we expressed a functional Ad5 fiber knob domain on the surface of phage λ. This phage display system was used to create a library in which ligands were surveyed in the knob context. Screening this library identified clones that bound to CAR-negative NIH 3T3 cells, and Ad5 derivatives incorporating these ligands showed markedly enhanced infectivity for the same cells. We demonstrated that the receptor targeted by these mutants is expressed in different cell types irrespective of CAR expression. Prompted by this observation, we began assessing these vectors for efficacy in infecting clinically relevant cell types. Here we show that the selected fiber mutations dramatically increased the uptake of Ad5 by both mouse and human primary immature DC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria and cells.

Escherichia coli strains BB4 and Y1090 were used for phage plating and amplification (34). Human embryonic retinoblast 911 cells were obtained from Invitrogen (Rijswijk, The Netherlands). Mouse fibroblast NIH 3T3, Chinese hamster ovary (CHO), and mouse liver NMuLi cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, Md.). Per.C6 cells were obtained from Crucell (Leiden, The Netherlands). 911, NIH 3T3, and NMuLi cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM). CHO were cultured in minimal essential medium (MEM) alpha medium. Per.C6 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10 mM MgCl2. All media were supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal calf serum.

Primary murine DC (kindly provided by Valentina Salucci, IRBM) were obtained from BALB/c female bone marrow as described previously (23). Briefly, total bone marrow leukocytes were plated in bacteriological petri dishes in RPMI with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (2 ng/ml). The medium was changed every 2 to 3 days. On day 7 of in vitro culture, the cells were used. Human DC cells (kindly provided by Barbara Cipriani, IRBM) were obtained as described previously (10). Briefly, human blood monocytes were isolated from buffy coats from a healthy donor by affinity purification with anti-CD14 (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, Calif.). Immature DCs were generated by culturing monocytes in RPMI 1640-10% fetal bovine serum in the presence of interleukin-4 (100 ng/ml; Duotech, Rocky Hill, N.J.) and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (800 U/ml; Duotech, Rocky Hill, N.J.). The medium was changed every 3 days, and on day 7 the cells were used.

Antibodies.

Phage λ particles were amplified and purified as described previously (34). Recombinant Ad5 fiber knob and λ D protein were obtained from plasmids pHis.knob (see below) and pNS3785 (37), respectively. Both proteins were expressed in E. coli and purified by fast protein liquid chromatography on a Hi Trap chelating HP column (APB, Uppsala, Sweden), exploiting their N-terminal six-His purification tag. Anti-λ, anti-knob, and anti-D serum samples were obtained by immunizing New Zealand rabbits with λ phage particles, purified recombinant Ad5 knob, or λ D protein, respectively, according to standard protocols (8). By screening a panel of human serum samples, samples that reacted with both the monomeric and trimeric (serum N92) or only with the trimeric (serum N93) form of the bacterially expressed Ad5 fiber knob protein were identified.

In the experiments described, antibodies purified on protein-A Sepharose (Amersham-Pharmacia, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) according to the manufacturer's instructions from serum R330 (antibody R330), anti-λ (antibody anti-λ), N92 (antibody N92), and (antibody N93) were used. Mouse monoclonal antibody 12D6, which selectively recognize Ad5 knob trimer, was derived from mice immunized with Ad5 viral particles according to standard protocols (43).

Construction of plasmid pD, its derivatives, and the corresponding λ clones.

An XbaI restriction site was introduced into plasmid pNS3785 to allow cloning of the entire plasmid into the unique XbaI site of λDam15imm21nin5 (37). Plasmid pNS3785 was amplified by inverse PCR with primers XbaI-NS.for (5′-TTTATCTAGACCCAGCCCTAGGAAGCTTCTCCTGAGTAGGACAAATCC-3′) and XbaI-NS.rev (5′-GGGTCTAGATAAAACGAAAGGCCCAGTCTTTC-3′; the XbaI site is underlined). The reaction was performed with a mixture of Taq and Pfu DNA polymerases to increase the fidelity of DNA synthesis (95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 20 min for 25 amplification cycles). The PCR amplification product thus generated was digested with XbaI endonucleases and ligated to generate plasmid pD.

Plasmid pD was transformed into pD-knob by modifying the 3′ end of the λ D gene as indicated in Fig. 1A. A 65-bp double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) fragment containing a ribosome-binding site and a KpnI site (underlined) was obtained by annealing the oligonucleotides link-SD.s (5′-GACCGCGTTTGCCGGAACGGCAATCAGCATCGTTGGTTCCGGCTCTGGTAAGGAGGTACCGTAGG-3′) and link-SD.as (5′-AATTCCTACGGTACCTCCTTACCAGAGCCGGAACCAACGATGCTGATTGCCGTT-3′). This DNA fragment was cloned into plasmid pD at the 3′ end of the lambda D gene, between the RsrII and EcoRI restriction sites, generating plasmid pD-linker.

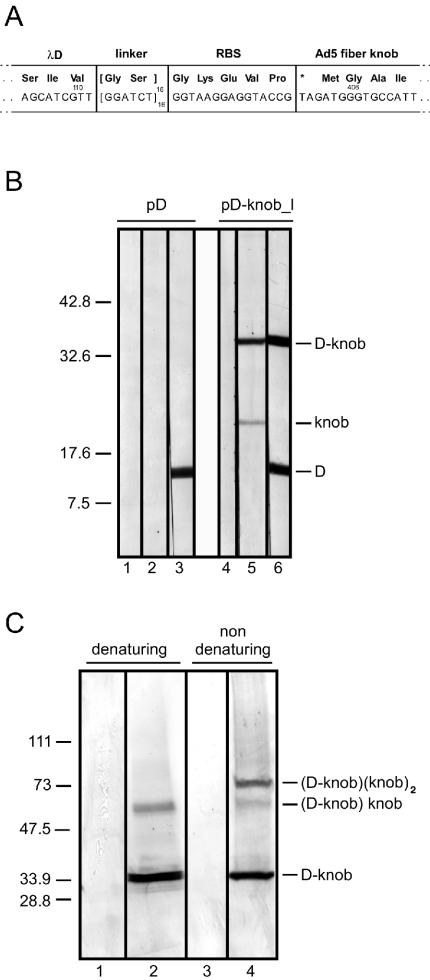

FIG. 1.

Display of Ad5 knob domain on λ surface. (A) Structure of D-knob expression cassette. Nucleotide and amino acid (in the three-letter code) sequences of the region between the λ D and Ad5 fiber knob genes are shown, as well as linker, ribosome-binding site (RBS), and amber codon sequences. Numbers indicate the position of D and fiber gene residues. (B) Proteins expressed by plasmid pD-knob_l in bacterial cells. Lysates from bacterial cells transformed with plasmid pD or pD-knob_l were analyzed by SDS-12.5% PAGE and probed with prebleed (pre-R330; lanes 1 and 4) or second-bleed (antibody R330; lanes 2 and 5) serum from rabbit R330 or with anti-D serum (lanes 3 and 6). (C) Assembly of protein complexes on the λ capsid. Purified wild-type λ (lanes 1 and 3) and wild-type λ knob (lanes 2 and 4) particles (3 × 1010 PFU) were added to denaturing or nondenaturing sample buffer and separated by SDS-PAGE with a 4 to 20% Tris-HCl gradient gel (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.). Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and probed with rabbit anti-D serum. Proteins smaller than 20 kDa (i.e., D protein) were not included in this analysis. The identity of the complexes detected is proposed.

The DNA sequence coding for the Ad5 fiber knob domain was PCR amplified from plasmid pAB26 (4) with D-fbr.for (5′-TAGGGTACCGTAGATGGGTGCCATTACAGTAGGAAACAAAA-3′; the KpnI site is underlined) and D-fbr.rev (5′-AAAGAATTCTTTATTCTTGGGCAATGTATG-3′; the EcoRI site is underlined) primers. The resulting 600-bp fragment was digested with KpnI and EcoRI restriction enzymes and inserted in plasmid pD-linker at the 3′ end of the lambda D gene between the corresponding sites, generating plasmid pD-knob_linker (indicated as pD-knob_1 in Fig. 1B).

A dsDNA fragment coding for two Gly-Ser (GS) repeats and containing a BamHI site was obtained by annealing the oligonucleotides BamHI_(GS)2.s (5′-GACCGCGTTTGCCGGAACGGCAATCAGCATCGTTGGATCCGGTTCTGGTAAGGAGGTAC-3′; BamHI site underlined) and BamHI_(GS)2.as (5′-CTCCTTACCAGAACCGGATCCAACGATGCTGATTGCCGTTCCGGCAAACGCG-3′). This 59-bp DNA fragment was inserted between the RsrII and KpnI sites of plasmid pD-knob_linker to create plasmid pD-knob_(GS)2. Multiple Gly-Ser (GS) repeats were then inserted between the D and the knob genes in this plasmid.

dsDNAs of different lengths were generated by annealing the oligonucleotides GS-link.s (5′-GATCTGGTTCCGGTTCTGGCTCCGGCTCTGGTTCTGGTTCCG-3′) and GS-link.as (5′-GATCCGGAACCAGAACCAGAGCCGGAGCCAGAACCGGAACCA-3′), promoting the formation of polymeric products. By cloning this mixture of dsDNAs in the BamHI site of plasmid pD-knob_(GS)2, plasmids containing one [pD-knob_(GS)9] or two [pD-knob_(GS)16] inserts were identified. The latter was used in the experiments described and is referred to as pD-knob.

Plasmid pD-knobΔ, containing the 489TAYT492 deletion in the fiber knob gene which abolishes binding to CAR (32), was generated by replacing the BglII/EcoRI fragment in plasmid pD-knob with a BglII- and EcoRI-digested PCR product. The latter was amplified from the same pD-knob plasmid with primers knobΔ.for (5′-GGAGATCTTACTGAAGGCAACGCTGTTGGATTTATG-3′; BglII site underlined) and D-fbr.rev (5′-AAAGAATTCTTTATTCTTGGGCAATGTATG-3′; EcoRI site underlined). Phage λwild-type knob was generated by inserting the XbaI-linearized plasmid pD-knob into the unique XbaI site of phage λDam15imm21nin5. After overnight incubation at 4°C, the ligation mixture was packaged in vitro with the lambda packaging kit (APB, Uppsala, Sweden) and plated with top agar on NZY-agar plates. Positive clones were identified by PCR, amplified, and purified ((34).

Gel electrophoresis and Western immunoblots.

Immunoblots were performed on lysates from plasmid-transformed bacterial cells, purified lambda phage particles, or purified knob proteins by standard techniques (15). Briefly, samples were added to denaturing sample buffer containing 0.175 M Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 20% glycerol, 4.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 10% 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.002% bromophenol blue, and 6 M urea or added to nondenaturing sample buffer, which lacked urea and contained only 0.2% SDS (24). Samples were heated for 10 min at 95°C (denaturing conditions) or at 37°C (nondenaturing conditions) before being loaded onto an SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Samples were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and transferred by electroblotting onto nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher & Schuell GmbH, Dassel, Germany). Nonspecific binding was blocked by incubating membranes with 5% nonfat dry milk in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST). The membrane was divided into several vertical stripes, which were probed separately with antibodies N92 and N93 and with pre- and second-bleed serum samples from rabbit R330. Serum samples were incubated with bacterial extract diluted in PBST. Alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-human or anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) was used as the secondary antibody, and the blot was developed with nitroblue tetrazolium and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.).

In experiments assessing the specificity of the anti-knob antibodies, equal amounts (7 μg) of purified knob and NS3hel proteins were loaded onto a 12.5% polyacrylamide gel. HCV-NS3hel, the helicase domain from NS3 protein of hepatitis C virus (amino acids 1201 to 1647 of the viral polypeptide, as predicted from the nucleotide sequence of the viral genome subtype 1b [38]) was kindly provided by P. Gallinari (IRBM) and used as an internal negative control.

Phage ELISA.

Multiwell plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated overnight at 4°C with goat anti-human immunoglobulin G Fc-specific (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) or with anti-mouse immunoglobulin G-specific (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) antibodies at a concentration of 2.2 μg/ml or 5 μg/ml, respectively, in 50 mM NaHCO3 (pH 9.6). After the coating solution was discarded, the plates were incubated at 37°C for 60 min with PBST. The blocking solution was discarded, and antibody N92, antibody N93, or monoclonal antibody 12D6 in blocking buffer was added and allowed to bind for 2 h at room temperature. Plates were washed with PBST, and about 109 PFU of phage lysate in binding buffer (5% nonfat dry milk in PBS) was incubated for 4 h at room temperature. The plates were then washed with PBS, and captured phage particles were detected with anti-lambda polyclonal antibody in binding buffer for 2 h at room temperature. After washing with PBS, an anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G-alkaline phosphatase conjugate (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) in binding buffer was incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The plates were then washed, and alkaline phosphatase activity was detected by incubation with Sigma 104 phosphatase substrate (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) in diethanolamine. Plates were read with an automated enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reader (Multiskan Bichromatic; Lab Systems, Helsinki, Finland).

FACS analysis.

Binding of phage λ knob derivatives to 911 and NIH 3T3 cells was analyzed with fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)-based assays. For 911 cells, a suspension of 2 × 106 cells/ml was incubated with 6 × 1011 PFU of phage per ml for 60 min at room temperature in binding buffer composed of 3% bovine serum albumin, 10 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM CaCl2 in PBS. For NIH 3T3 cells, a suspension of 2 × 106 cells/ml was incubated with 1010 PFU phage/ml for 60 min at 37°C in binding buffer. Cells bound to phage particles were detected with rabbit anti-λ purified IgG and goat anti-rabbit IgG which was conjugated to either fluorescein isothiocyanate (for 911 cells) or R-phycoerythrin (RPE, for NIH 3T3 cells; Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) and analyzed with a FACSCalibre flow cytometer and CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson, Oxford, United Kingdom). The differential labeling for the two cell lines was dictated by the availability of reagents. In competition experiments, cells were incubated with 200 μl of binding buffer containing 10 μg of a His-tagged knob protein (or a His-tagged unrelated protein) per ml for 60 min at room temperature. To this mixture were added 6 × 1010 PFU of phage without removing the unbound protein and incubated for additional 60 min at room temperature.

Construction of the λknobΔ-14aa.cys library.

Plasmid pD-knobΔ-L0 was generated by introducing unique SpeI and NotI sites in the HI loop in pD-knobΔ. DNA fragments of 326 bp and 93 bp were obtained by PCR amplifying plasmid pD-knob with the primers knob.for2 (5′-AGGCAGTTTGGCTCCAATATCTG-3′) and knobHI-Spe/Not.rev (5′-GCGGCCGCACCACTAGTTGTGTCTCCTGTTTCCTGTGTA-3′) or primers knobHI-Spe/Not.for (5′-ACTAGTGGTGCGGCCGCTCCAAGTGCATACTCTATGTCATTT-3′) and knob.rev3 (5′-GGATGTGGCAAATATTTCATTAAT-3′), respectively. These DNA fragments were PCR ligated, BglII and MscI restricted, and inserted between the corresponding sites in pD-knobΔ to generate plasmid pD-knobΔ-L0 (the sequence is shown in Fig. 3A). This plasmid was linearized by XbaI digestion and cloned in the unique XbaI site of λDam15imm21nin5 (37). The phage λknobΔ-L0 thus generated was amplified and CsCl purified as described previously (34). DNA was extracted from lambda particles and used for library construction.

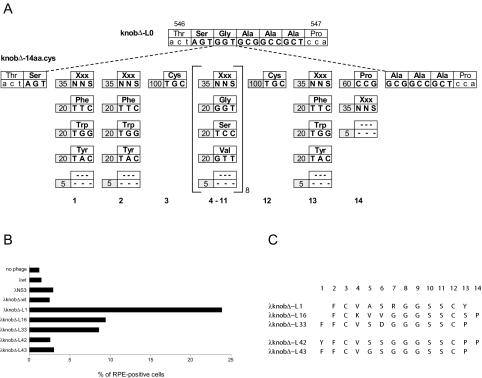

FIG. 3.

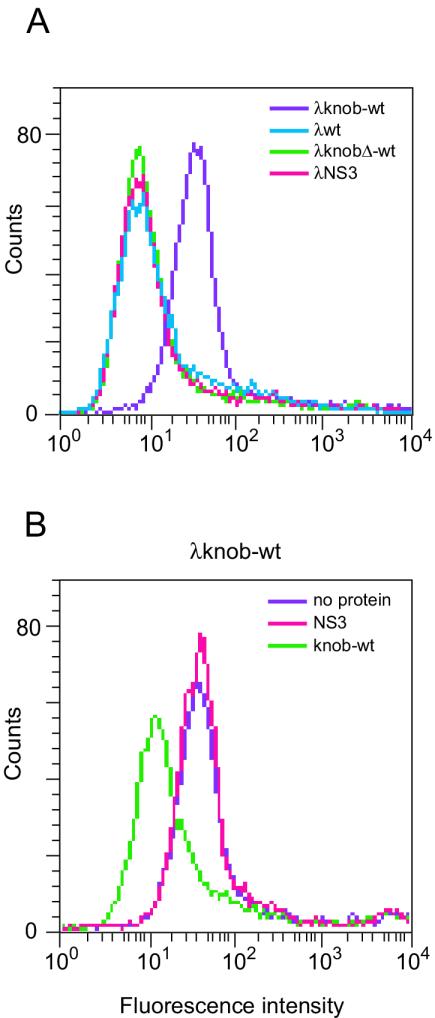

FACS analysis of binding of λ-displayed Ad5 knob to CAR-positive 911 cells. (A) Binding of phage-borne Ad5wt-knob and Ad5knobΔ-wt to 911 cells. Negative controls (wild-type λ and λNS3) were included. (B) Binding of λwt-knob to 911 cells in the presence of wild-type knob protein. Control reactions in the absence of protein and in the presence of λNS3 are also reported.

The library oligonucleotide was synthesized according to the splitting synthesis protocol, converted into dsDNA by primer elongation, SpeI and NotI digested, and ligated into the corresponding sites of λknobΔ-L0. The ligation mixture was packaged in vitro (APB, Uppsala, Sweden) and plated on NZY-agar plates (14). After overnight incubation, phage was eluted from the plates with SM buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 0.01% gelatin, 10 mM MgSO4, 100 mM NaCl), purified, concentrated, and stored at −80°C in SM buffer with 7% dimethyl sulfoxide. The complexity of the λknob-14aa.cys library was 1.6 × 105, as estimated from the number of individual plaques obtained by plating the packaging mixture. Sequence analysis of 20 clones chosen at random confirmed the presence of the expected nucleotide in all the clones. By improving the quality of the reagents, we managed to obtain libraries composed of more than 107 independent clones.

Panning library on cells.

NIH 3T3 cells were seeded at 2 × 106 cells in a 60-mm-diameter petri dish and incubated in culture medium at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 48 h. Confluent cells were then incubated with 5 ml of blocking buffer (3% bovine serum albumin, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2 in PBS) for 1 h at 37°C on a rocking platform. The solution was then discarded, and 5 × 109 PFU of phage library in 1 ml of blocking buffer were added and incubated for 3 h at 37°C on a rocking platform. Unbound phage were removed and titrated, and the cells were washed extensively with blocking buffer at 4°C. Bound phage were amplified by adding 1.2 ml of E. coli Y1090 cells in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium containing 0.2% maltose and incubated for 20 min at room temperature. Phage were titrated as PFU by diluting the infection mixture and plating it onto LB-agar plates. The phage pool derived from this first round of selection was amplified and purified as described previously (2). Phage thus prepared were panned a second time on NIH 3T3 cells with the same protocol.

Immunological screening of recombinant λ clones.

Phage plaques were generated as described above and transferred onto nitrocellulose filters (Schleicher & Schuell GmbH, Dassel, Germany) (2). The filters were saturated with blocking buffer (5% nonfat dry milk in PBS, 0.01% Triton) for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated with human N93 or R330 anti-knob antibodies diluted in blocking buffer for 2 h at room temperature. After being washed several times with PBST, alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibody (anti-human IgG or anti-rabbit IgG) was diluted in blocking buffer and incubated with the filters for 60 min at room temperature. Positive phage plaques were visualized by developing the filters with chromogenic substrates (nitroblue tetrazolium and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate substrates; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.).

Cell ELISA.

Cells were seeded at about 80,000 cells/well in 500 μl of culture medium in 24-well plates and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 48 h. Confluent cells were incubated with medium without serum for 1 h at 37°C, washed once with cold PBS, and then fixed by incubating with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at 4°C. Cells were washed extensively with cold PBS and blocked by incubating with PBBS++ buffer (1% bovine serum albumin, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2 in PBS) for 30 min at 4°C. The blocking solution was discarded, and about 109 PFU of phage lysate in PBBS++ buffer were incubated for 4 h at room temperature. The plates were then washed with PBBS++, and captured phage particles were detected by antilambda polyclonal antibody in binding buffer. The plates were then washed and incubated at room temperature with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin polyclonal antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). Finally, alkaline phosphatase activity was detected by incubation with Sigma 104 phosphatase substrate (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) in diethanolamine. Plates were read with an automated ELISA reader (Multiskan Bichromatic; Lab Systems, Helsinki, Finland), and the results were expressed as A = A540 − A620.

Expression of recombinant Ad5 fiber knob.

The DNA sequence of the Ad5 fiber knob was PCR amplified from plasmid pAB26 with the Nhe-fbr.for (5′-GTTTTGACGCTAGCGGTGCCATTACAGTAGGAAAC-3′; NheI site underlined) and D-fbr.rev (5′-AAAGAATTCTTTATTCTTGGGCAATGTATG-3′; EcoRI site underlined) primers. The resulting 600-bp fragment was digested with NheI and EcoRI restriction enzymes and cloned into the corresponding sites of plasmid pTRCHisB (Invitrogen, Groningen, The Netherlands), generating plasmid vector pHis.knob. Plasmid pD-knobΔ.SN-Cterm was obtained by cloning an MscI- and EcoRI-restricted PCR fragment obtained from pD-knob between the MscI and EcoRI sites of plasmid pD-knob with primers knob-for3 (5′-CCAAGTGCATACTCTATGTCATTTT-3′) and knobC-Spe/Not.rev (5′-TCGAATTCTTTAAGCGGCCGCACCACTAGTTTCTTGGGCAATGTATGAAAA-3′; SpeI and NotI sites underlined).

A PCR product was obtained by amplifying plasmid pD-knobΔ.SN-Cterm with primers knobΔ (5′-GGAGATCTTACTGAAGGCAACGCTGTTGGATTTATG-3′; BglII site underlined) and pD.rev (5′-TCTGATTTAATCTGTATCAGGCTG-3′). This PCR product was BglII and MscI restricted and inserted between the corresponding sites of pHis.knob to generate plasmid pHis.knobΔ, containing the coding sequence of the fiber knob deleted of the codons for amino acids 489TAYT492.

Plasmid pD-knobΔ-L0 was PCR amplified with primers knobΔ (5′-GGAGATCTTACTGAAGGCAACGCTGTTGGATTTATG-3′; BglII site underlined) and pD.rev (5′-TCTGATTTAATCTGTATCAGGCTG-3′). The resulting PCR product was digested with BglII and EcoRI restriction enzymes and cloned into the corresponding sites of the pHis.knob vector. This plasmid was the recipient of ligand sequences through unique SpeI and NotI sites inserted in the knob HI loop, generating plasmid pHis.knobΔ-LX. The resulting pHis.knobΔ.SN-HI loop vector was digested with SpeI and NotI enzymes and used for cloning fragments containing the selected epitopes, which were obtained by PCR amplification of lambda DNA of the L derivatives with the primers bioSN.for (5′-ACAGGAAACAGGAGACACAACTAGT-3′) and bioSN.rev (5′-TAGAGTATGCACTTGGAGCGGCCGC-3′), digested with SpeI and NotI enzymes, and purified on streptavidin-coated magnetic microbeads (Dynal A.S., Oslo, Norway).

Construction of recombinant Ad plasmids.

First-generation adenoviruses containing a luciferase-expressing cassette in place of the E1 region of the Ad5 genome and the selected peptide ligands in the HI loop of fiber were constructed by homologous recombination in E. coli (6).

The XbaI/EcoRV fragment (Ad5 bp 25219 to 27018), including the entire Ad5 fiber gene, was cloned into the corresponding sites of vector pLITMUS28 (New England Biologicals, Beverly, Mass.) generating plasmid pLITfbr. Self-annealing the MfeI-SwaI oligonucleotide (5′-AATTCCCATTTAAATGGG-3′) generated an 18-bp dsDNA fragment containing a SwaI restriction site (underlined). Thanks to its MfeI-compatible ends, this fragment was cloned into the MfeI site of pLITfbr, creating a unique SwaI site immediately downstream of the fiber gene. The resulting plasmid, pLITfbrSwaI, was used to introduce the SwaI site in the pAd5-H10 backbone (35) by bacterial homologous recombination, generating pAd5-H10SwaI (the acceptor plasmid was linearized by NdeI partial digestion). Ad5luc and Ad5luc-SwaI derivatives harboring a luciferase expression cassette that replaces the E1 region of the Ad5 genome were constructed as follows. Digesting plasmid pGGluc (Gene Therapy Systems, Inc., San Diego, Calif.) with McsI and KpnI restriction enzymes isolated a 3.5-kb fragment containing the cytomegalovirus-luciferase expression cassette. This DNA fragment was blunt ended by T4 polymerase and cloned into the ClaI and EcoRV sites of the shuttle vector pΔE1sp1A (3) to generate plasmid pΔE1CMVLuc.

A 6.4-kb DNA fragment containing the luciferase expression cassette flanked by Ad5 genome sequences was excised from pΔE1CMVLuc by SspI and BstZ17 digestion and inserted by homologous recombination in E. coli cells into ClaI-linearized plasmid pBHG10 (6). An 8.8-kb AvrII/BstZ17 DNA fragment was obtained from this last clone and inserted into the PacI site of pAd5-H10 or pAd5-H10SwaI backbone (35) to generate pAd5luc-wt or pAd5luc-SwaI, respectively.

Ad5 fiber shuttle plasmid pLITfbr-L0 was constructed by engineering unique SpeI and NotI sites in the knob HI loop region in pLITfbr as shown in Fig. 4A. First, two PCR fragments were obtained with pLITfbr as the template and the primer knob-for2/knobHI.rev (5′-GAGTATGCGGAAGGGTTTCCTGTGTACCGTTTAGTG-3′) or knobHI.for (5′-CAGGAAACCCTTCCGCATACTCTATGTCATTTTCATGGG)) and knob-rev2 (5′-GCTATGTGGTGGTGGGGCTATACTA-3′). These PCR products were PCR ligated, digested with MfeI and BglII, and cloned into the corresponding sites of pLITfbr, generating plasmid pLITfbr-XmnI-HIloop. Then, the SpeI site in the polylinker was destroyed by digestion with SpeI, followed by blunting with Klenow and religation. Finally, a fragment created by annealing the oligonucleotides SN-adapter.s (5′-AGGAGACACAACTAGTGGTGCGGCCGCT-3′, SpeI site underlined) and SN-adapter.as (5′-AGCGGCCGCACCACTAGTTGTGTCTCCT-3′; NotI site underlined) was inserted into the XmnI-digested pLITfbr-ΔSpe-XmnI-HIloop vector, generating plasmid pLITfbr-L0. Ligand sequences were PCR amplified from the λ DNA template with the primers bioS/N.for and bioS/N.rev. The PCR products were SpeI and NotI digested and cloned into the corresponding sites of pLITfbr-L0 to generate plasmid pLITfbr-LX. Mutated fiber sequences from pLITfbr-LX plasmids were incorporated into pAd5luc-SwaI by bacterial homologous recombination, generating plasmid pAd5luc-LX.

FIG. 4.

Selection and characterization of λknobΔ clones binding to NIH 3T3 cells. (A) Structure of λknobΔ-14aa.cys library. The upper part of the figure refers to the sequence of the knob-L0 mutant between positions 546 and 547 of the fiber gene. Amino acid residues are indicated with the three-letter code. Additional sequences are indicated in capital letters. The lower part of the figure details the composition of the oligonucleotide mixture used to generate the knobΔ-14aa.cys library. Numbers at the bottom indicate library positions. Bars at each position indicate the percentage and codon sequence of the corresponding amino acid. S refers to an equimolar frequency of C and G residues. (B) λknobΔ-L mutants bind NIH 3T3 cells. Binding of phage λ clones to NIH 3T3 cells was assayed by flow cytometric analysis. Data are reported as the percentage of RPE-labeled cells. (C) Amino acid sequences of λ knob mutants. Clones L1, L16, and L33 bound NIH 3T3 cells and were derived from the screening of the λknobΔ-14aa.cys library. Clones L42 and L43, which did not bind NIH 3T3 cells, were generated by site-directed mutagenesis of a mixture of the L1, L16, and L33 ligand sequences. For each clone, the amino acid sequence of the foreign peptide inserted in the HI loop is reported in the single-letter code. Numbers at the top refer to the position of the residues in the library. Knob sequences flanking the foreign epitope are 542TGDTTS[foreign epitope]AAAPSAYS551. Underlined residues were engineered to create restriction sites. Numbers refer to the positions of wild-type residues.

Viruses.

The recombinant adenoviruses were propagated on PerC.6 cells and purified by centrifugation in CsCl gradients according to standard protocols (11). Virus particle titers were determined spectrophotometrically, assuming that 1 U of optical density at 260 nm corresponds to 1.1 × 1012 particles/ml (17). Because the attachment molecule(s) for Ad5 derivatives is unknown, vectors need to be compared with equal amounts of virus particles per cell. The consistent results from several experiments with different batches of Ad5 mutants and the comparable infectivity measured for all viruses on CAR-positive cells exclude the possibility that the quality of virus preparations contributed to the variations observed in transduction efficiency. Restriction analysis of the viral genome and sequencing of the fiber knob region confirmed the identity of virus preparations. All Ad5luc derivatives showed times from transfection to cytopathic effect, amplification rates, and virus yields indistinguishable from those of Ad5luc-wt virus. Viruses were named Ad5luc-LX, where X indicates the knob mutation incorporated in the viral genome.

Transduction of cells.

NIH 3T3 and NMuLi cells were seeded at about 50,000 cells/well in 500 μl of culture medium in 24-well plates and incubated for 48 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. Confluent cells were washed with DF buffer (2% fetal bovine serum in DMEM) and infected with CsCl-purified adenovirus in DF buffer for 30 min at room temperature. Unbound virus was removed, and the cells washed with DF buffer. For CHO cells, α-MEM was used. Fresh complete medium was added, and cells were incubated for 48 h for protein expression. Cell extract and luciferase assays were performed with the luciferase assay system (Promega, Madison, Wis.), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Luciferase activity is expressed as relative light units (RLU) per milligram of protein. Each point in display items represents the mean of triplicate determinations, and the standard deviation for each value is reported.

In competition experiments, cells were incubated with 5 μg of recombinant protein or 4 mg of RGD or control RGE peptide per ml in DF buffer for 60 min at room temperature. Virus was then added (50 vp/cell) without removing the protein or the peptide, and infection was allowed to proceed as above. Results are expressed as the percentage of luciferase activity of cells in the presence of control protein (knobΔ-L16 for Ad5luc-wt and wild-type knob for Ad5luc-L16) or RGE peptide, respectively. Synthetic peptides were obtained from Bio Synthesis (Lewisville, Tex.).

Mouse and human DC were seeded at about 200,000 cells/well in 500 μl of culture medium in 24-well plates and incubated for 24 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. Confluent cells were washed with RF buffer (2% fetal bovine serum in RPMI) and infected with CsCl-purified adenovirus in RF buffer for 40 min at room temperature. Unbound virus was removed, and the cells were washed with RF buffer and incubated with complete medium for 48 h for protein expression.

RESULTS

Display of Ad5 trimeric knob domain on the capsid of phage λ.

We engineered a bacterial expression plasmid to direct the synthesis of a bicistronic system composed of the gene coding for the major head D protein of bacteriophage λ upstream of the gene encoding for the Ad5 fiber knob domain. The vector was designed to add a Gly-Ser peptide linker at the C terminus of D protein, followed by a ribosome-binding site, a D gene amber translation codon, TAG, and the Ad5 knob gene methionine initiator codon (Fig. 1A). Following transformation in a suppressor bacterial host, the resulting plasmid pD-knob expressed (i) the recombinant wild-type D protein encoded by the plasmid D gene; (ii) the D-knob fusion, as a result of bacterial suppression; and (iii) the knob protein, by translational reinitiation (Fig. 1B).

Plasmid pD-knob was inserted into the XbaI site of the λDam15imm21nin5 genome (37), which contains a genomic copy of the D gene with an amber mutation at the N terminus. In a suppressor bacterial host, the resulting phage particle λwild-type knob displayed a chimeric array of D and fusion D-knob protein on its capsid (Fig. 1C). In addition, on samples run under nondenaturing conditions, anti-D antibodies revealed the presence of high-molecular-weight complexes (Fig. 1C). D proteins are assembled as trimers protruding on the capsid surface (9). Mikawa et al. (25) demonstrated that fusing polypeptides at either terminus of the D protein does not disrupt this trimer interaction and is compatible with the assembly of the phage particle. The size of the complexes detected, the conditional fusion between D and knob, and the ability of the knob protein to trimerize are consistent with the assembly of the (D-knob)(knob)2 complex on the λ capsid.

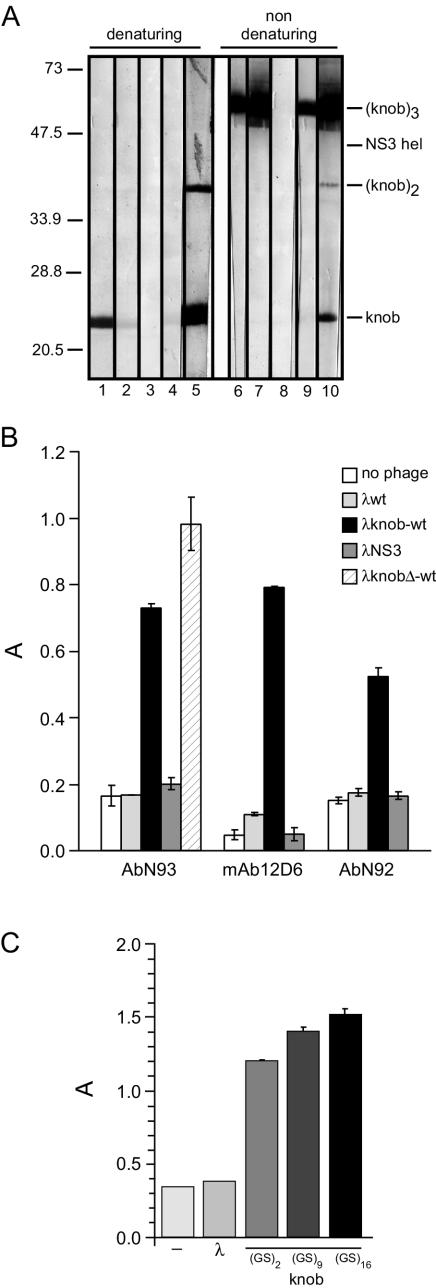

We generated a monoclonal antibody (12D6) and identified a human serum (N93) that selectively recognized the Ad5 homotrimeric knob structure (Fig. 2A). These reagents specifically reacted with the λwild-type knob lysate in a phage enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), indicating that knob trimers are efficiently displayed on the capsid of the phage particle (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Display of trimeric Ad5 knob domain on λ capsid. (A) Antibodies specifically recognizing the homotrimeric Ad5knob domain complex. Purified knob protein was added to denaturing or nondenaturing sample buffer and separated by SDS-12.5% PAGE. An equal amount of NS3hel protein was loaded on the same gel as an internal negative control. Samples were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and probed with human antibody N92 (lanes 1 and 6), antibody N93 (lanes 2 and 7), no serum (lanes 3 and 8), prebleed antibody (pre-R330; lanes 4 and 9), or second-bleed antibody (antibody R330; lanes 5 and 10) from rabbit antiserum R330. (B) Detecting Ad5 knob trimeric complex on the lambda surface. Binding of mouse monoclonal antibody 12D6 and human antibody N93 (both specific for the trimeric form of Ad5 knob) and antibody N92 antibodies (which detect both the monomeric and the trimeric structure) was assessed by phage ELISA. Results are expressed as A = A405 − A620. Each point represents the mean of triplicate determinations. The standard deviation for each value is reported. (C) Display of knob trimer on λ capsid with spacer sequences of different lengths between the D and knob proteins. The wild-type λ knob phage were generated, in which the D and knob genes were separated by a linker formed by 2, 9, or 16 repeated Gly-Ser units. Purified wild-type λ, λ-wt-knob(GS)2, λ-wt-knob(GS)9 or λwt-knob(GS)16 particles (2 × 108 PFU) were incubated with immobilized antibody N93 antibodies, which specifically bind the knob trimeric complex. Captured phage particles were detected by ELISA with anti-λ antibodies. Results are expressed as A = A405 − A620. Each point represents the mean of triplicate determinations. The standard deviation for each value is reported.

The deletion of Ad5 fiber TAYT residues (included between positions 489 and 492 in the knob DG loop) completely abolished the high-affinity binding of Ad5 fiber to CAR (32). The corresponding λknobΔ-wt derivative reacted specifically with anti-homotrimeric knob antibodies, indicating that this knob mutant is still displayed as a homotrimer on the phage capsid (Fig. 2B). Finally, either wild-type λ or λNS3 (a negative-control clone expressing the 80 amino acids from the NS3 protein of hepatitis C virus on its surface) showed background levels of binding.

We compared Gly-Ser linker peptides of different lengths for their ability to promote the independent folding of the D and knob proteins. The (Gly-Ser)16 linker peptide was found to provide the most efficient expression of the knob trimer on the lambda capsid and was adopted for further studies (Fig. 2C).

λ-borne Ad5 knob specifically binds human CAR on 911 cells.

To demonstrate the functionality of the phage-displayed knob, λwild-type knob virions were incubated with human embryonic retinoblast 911 cells, which express high levels of CAR on their surface (12). CAR-specific binding was assayed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis. λwild-type knob phage particles bound to 911 cells, as indicated by the variation in distribution of fluorescently labeled cells (Fig. 3A). Increasing phage titers linearly increased the amount of bound phage, as measured by the median fluorescence of cells (data not shown). In contrast, neither wild-type λ, λNS3, nor λknobΔ-wt showed detectable levels of binding. Binding of λwild-type knob to 911 cells was inhibited by incubation with an excess of wild-type knob protein, whereas incubation with the unrelated protein NS3 had no effect (Fig. 3B).

Generating a library of Ad5 knob mutants displayed on λ.

We employed the λknob display system to generate and screen a large collection of mutants created by inserting ligand sequences within the knob domain. To eliminate the interference of CAR binding in screening for nonnative tropism, we built this library in the λknobΔ-wt vector. We chose the HI loop of the knob domain as the site for inserting foreign peptide sequences and introduced unique SpeI and NotI restriction sequences at the same position originally used by Curiel and coworkers (19) (Fig. 4A). As a result of these manipulations, the derivative λknobΔ-L0 incorporated the extrapeptidic sequence SGAAA between T546 and P547.

Oligonucleotides were synthesized by a resin-splitting methodology to encode 14 amino acid residues flanked by SpeI and NotI restriction sites (14) (Fig. 4A). The peptide sequence was constrained by incorporating two fixed Cys residues at positions 3 and 12. Positions 1, 2, and 13 were biased for the presence of aromatic amino acids to favor interaction with hydrophobic receptor structures (L. Fontana, unpublished observation). Proline, which tends to adopt an extended structure, was favored at position 14 to increase the accessibility of the inserted peptide (18). The remaining 4 to 11 positions were designed to preferentially encode amino acids with small lateral chains (glycine, serine, or valine) to increase the loop flexibility. Finally, further variation in loop length was introduced by deleting 5% of the codons at each position except those coding for the fixed cysteines.

Elongation of a primer that annealed to these oligonucleotides' constant 3′ end converted them to dsDNA fragments which were SpeI and NotI restricted and cloned into the corresponding sites of the vector λknobΔ-L0. In vitro packaging and plating of the ligation mixture generated the library λknobΔ-14aa.cys, comprising 2 × 105 independent clones.

Screening the λknobΔ-14aa.cys library for mutants binding to NIH 3T3 cells.

We screened the library of knob mutants to select clones binding to a cell surface receptor other than CAR. Mouse embryo fibroblast NIH 3T3 cells, which display undetectable levels of CAR on their surface and are poorly transduced by adenovirus, were chosen as the target cells (39). About 5 × 109 PFU of the λknobΔ-14aa.cys library was applied to plated NIH 3T3 cells. Following incubation, unbound phage were removed, cells were washed extensively, and bound phages were propagated by infecting bacteria. About 105 clones were rescued, amplified, and panned again on NIH 3T3 cells.

On screening with anti-knob antibodies, 26% of the clones in the input library and 20% or 9% of the phage recovered after the first and second panning round, respectively, scored positive. Among these anti-knob-positive clones, the relative frequency of clones displaying the trimeric complex increased from 75% in the input library to 100% in the phage recovered after either panning round. Thus, panning on cells enriches for phage which display a functional knob homotrimer. At the same time, knob expression is accompanied by a reduced growth rate which markedly favors clones that do not express the foreign protein during amplification.

To reduce the impact of this biological bias, we randomly choose 30 clones among the knob-positive ones from the pool of phage derived from a single panning round. Minilysates from each of these clones were prepared, and binding to NIH 3T3 cells was assessed by cell ELISA (data not shown). Through this preliminary screening, we selected a few clones which displayed the highest binding activity, measured as the difference between the binding of the clone and that of negative control phage (λ-wt, λ-NS3, or λknobD-wt). Binding of these clones to NIH 3T3 cells was further monitored by flow cytometry (Fig. 4B). Three clones (λknobΔ-L1, λknobΔ-L16, and λknobΔ-L33) showed a shift in the distribution median of fluorescently labeled cells compared to the parental λknobΔ-wt vector, indicating increased binding to NIH 3T3 cells. Control phage λNS3 bound NIH 3T3 cells with an efficiency comparable to that of λknobΔ-wt. Sequence analysis of these three clones revealed a high degree of similarity (Fig. 4C).

To identify residues critical for binding, we generated a number of mutants by site-directed mutagenesis. Among these, clones λknobΔ-L42 and λknobΔ-L43, which displayed a trimeric knob but no longer bound NIH 3T3 cells (data not shown and Fig. 4B and C), were included in this study as negative controls.

The Ad5 knobΔ-L1, knobΔ-L16, and knobΔ-L33 mutants were expressed in bacteria as recombinant proteins with a histidine tail added at their N termini to facilitate purification and detection. These recombinant knob proteins assembled as homotrimeric complexes and exhibited a higher degree of binding to NIH 3T3 cells than knobΔ-wt protein (data not shown).

Adenovirus vectors with mutated knob efficiently transduce NIH 3T3 cells.

We generated Ad5 derivatives incorporating the fiber knob mutations which conferred enhanced binding to NIH 3T3 cells and investigated their tropism. To simplify the downstream gene transfer assay, we inserted a firefly luciferase gene under the transcriptional control of the cytomegalovirus promoter in place of the E1 region of an Ad5 backbone (Ad5luc-wt). Adenovirus derivatives Ad5luc-L0, -L1, -L16, -L33, -L42, and -L43 were generated, in which the mutations in the knob HI loop listed in Fig. 4C were engineered in the corresponding region of the viral genome by homologous recombination in bacteria (6). Of note, to preserve CAR binding and allow amplification of the virus, we did not transfer the TAYT deletion but instead incorporated the LX mutations into the Ad5luc-wt fiber gene.

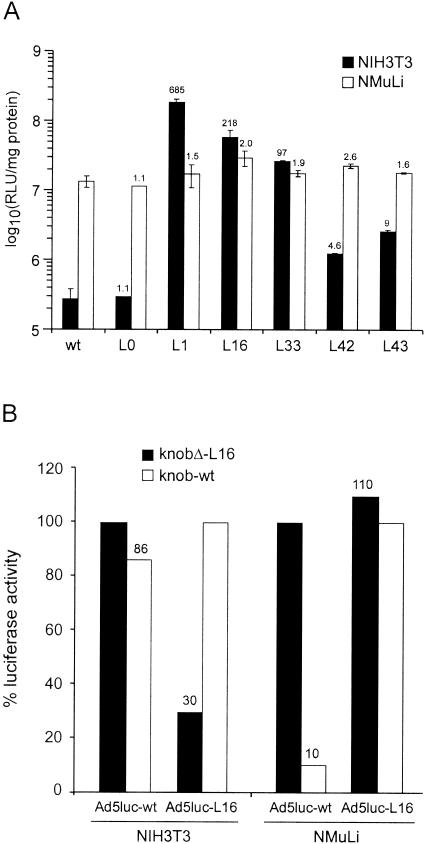

No significant differences were detected between the Ad5luc derivatives and the Ad5luc-wt virus with respect to amplification rate and virus yield in PerC.6 cells, measured as viral particles per cell. These Ad5luc derivatives were tested for their gene transfer efficiency into NIH 3T3 cells, taking Ad5luc-wt as a reference. The Ad5luc-L1, Ad5luc-L16, and Ad5luc-L33 mutants exhibited a dramatically improved transduction rate (from 100- up to 700-fold) on NIH 3T3 cells compared to Ad5luc-wt (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 5.

Gene transfer efficiency of Ad5luc-L mutants in NIH 3T3 and NMuLi cells. (A) NIH 3T3 or NMuLi cells were infected with the indicated virus at a multiplicity of infection of 50. Luciferase activity is expressed as relative light units (RLU) per milligram of protein. Each point in display items represents the mean of triplicate determinations, and the standard deviation for each value is reported. Values above the histograms refer to the ratio between the activity of the virus and that of the parent, Ad5luc-wt. (B) Competition of Ad5luc-L16 infection with knob proteins in NIH 3T3 and NMuLi cells. Results are reported above the histograms and expressed as the percentage of luciferase activity of cells in the presence of control protein (knobΔ-L16 for Ad5luc-wt and wild-type knob for Ad5luc-L16).

The Ad5luc-L0 control virus behaved indistinguishably from Ad5luc-wt, indicating that inserting the SGAAA sequence immediately after T546 in the fiber's HI loop did not affect virus tropism. The infectivity of Ad5luc-L42 and Ad5luc-L43 viruses was instead drastically reduced compared to their parent vectors. Increasing the multiplicity of infection increased the efficiency of gene delivery (data not shown).

To analyze the infectious pathway of the Ad5 derivatives, we performed competition assays by infecting NIH 3T3 cells in the presence of knob proteins. The gene transfer efficiency of Ad5luc-L16 in NIH 3T3 cells was reduced 70% by incubation with the homologous knobΔ-L16 protein compared to control wild-type knob protein (Fig. 5B). Since CAR is not expressed on NIH 3T3 cells, these findings demonstrate that our knob mutation activated a CAR-independent infectious pathway, mediated by binding to an unknown cell surface receptor. In contrast, the homologous wild-type knob protein had little effect on the already low levels of luciferase expression mediated by Ad5luc-wt compared to control knobΔ-L16 protein (Fig. 5B), indicating that its low transduction activity in NIH 3T3 is not mediated by CAR. Finally, we did not detect any reduction of transduction efficiency with the knobD-L16 protein used to compete with infection by Ad5luc-L1 or -L33 virus (data not shown).

Gene transfer efficiency of Ad5 knob mutants in CAR-positive cells.

We explored whether the receptor targeted by knob mutants was also expressed in CAR-positive cells by infecting mouse liver NMuLi cells, which express high CAR and αv integrin levels and are efficiently transduced by Ad5 (data not shown and Fig. 5A). All three Ad5 derivatives infected NMuLi cells with efficiency comparable to if not higher than that of Ad5luc-wt. An excess of wild-type knob protein lowered the infectivity of Ad5luc-wt virus to 10%, whereas the same conditions did not affect the transduction efficiency of knob mutants (Fig. 5B). These results indicate that Ad5luc-wt infects NMuLi cells through a CAR-dependent mechanism. In addition to this route, Ad5luc-L16 also transduces NMuLi cells by exploiting a CAR-independent cell entry pathway.

Cell entry of Ad5 knob mutants is mediated by αv integrins.

NIH 3T3 cells do not express CAR but have high levels of αvβ3 and αvβ5 integrins on their surface (39). We therefore assessed the role of integrin-penton interaction in the cell entry of Ad5 derivatives by measuring their transduction efficiency in the presence of an RGD (GRGDSP) compared to an RGE (GRGESP) control peptide. The RGD peptide blocks the interaction between the RGD motifs of the Ad5 penton base with cell αv integrins, thereby inhibiting viral entry (21). Incubation of NIH 3T3 cells with the RGD peptide reduced the transduction of Ad5luc-L1, Ad5luc-L16, and Ad5luc-L33 by 40, 60, and 61%, respectively, compared to control RGE peptide. Thus, following their primary interaction with an unknown cellular receptor, the Ad5 derivatives are internalized through binding to αv integrins. The same experiments with Ad5luc-wt showed a marked reduction of its already low transduction efficiency, indicating that the low infectivity of the virus in NIH 3T3 cells relies mainly on direct interaction with αv integrins (data not shown).

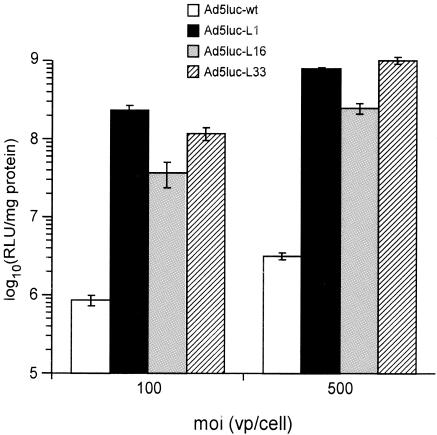

Gene transfer efficiency of Ad5 knob mutants in additional CAR-negative cells.

We investigated whether the nonnative infection route used by the Ad5 mutants also supported improved transduction in cells other than NIH 3T3 and NMuLi. Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were chosen because they express undetectable levels of CAR and αvβ3 integrin on their surface and low levels of αvβ5 (44). Not surprisingly, CHO cells were poorly transduced by Ad5luc-wt (Fig. 6). However, all three Ad5 derivatives infected these cells with efficiencies much higher than that of Ad5luc-wt. Ad5luc-L1 and Ad5luc-L33 proved the most efficient, with up to 270- and 320-fold increases over the control wild-type virus, respectively. The infectivity of Ad5luc-L42 and Ad5luc-L43 was comparable to that of Ad5luc-wt (data not shown). Thus, CHO cells also display the receptor targeted by knob mutants on their surface. In the absence of CAR and presence of low levels of αvβ5 integrin, this interaction mediates effective transduction of CHO cells.

FIG. 6.

Infection of CHO cells with Ad5luc-L mutants. CHO cells were infected with Ad5luc derivatives at different multiplicities of infection (moi). Luciferase activity is expressed as relative light units (RLU). Each point in display items represents the mean of triplicate determinations, and the standard deviation for each value is reported. vp, viral particles.

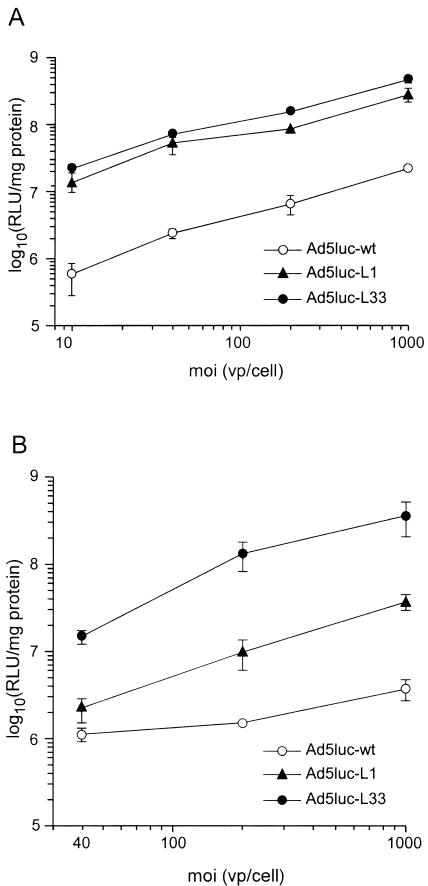

Gene transfer efficiency of DC.

The results obtained suggest that the CAR-independent tropism of the Ad5 derivatives is not restricted to a given cell type or a particular species (murine). We thus set out to assess whether the selected Ad5 mutants could be better suited to infect cells of therapeutic interest.

Mouse immature DC were obtained from bone marrow and amplified in vitro. This cell population, confirmed by FACS analysis to be CD11c+, CD11b+, MHC-I, MHC-II positive, was infected at various multiplicities of infection with Ad5luc-L33 and Ad5luc-L1 mutants. Both viruses transduce mouse immature DC with increased efficiency compared to Ad5luc-wt (Fig. 7A). In particular, Ad5luc-L33 infected mouse DC from 24- to 100-fold better than the parental vector, depending on the multiplicity of infection used.

FIG. 7.

DC transduction efficiency of Ad5luc-L derivatives. (A) Infection of bone marrow-derived mouse immature DC. (B) Infection of monocyte-derived human immature DC. Luciferase activity is expressed as relative light units (RLU). Each point in display items represents the mean of triplicate determinations, and the standard deviation for each value is reported. moi, multiplicity of infection; vp, viral particles.

A similar experiment was performed on immature human DC purified by CD14 affinity chromatography from the peripheral blood of a healthy donor and differentiated in vitro. FACS analysis confirmed that this population was CD1a+, HLA-DR+, CD80+, CD83+, CD86+, and CD14neg. As reported in the literature, Ad5luc-wt poorly transduced immature human DC at the multiplicity of infection tested (Fig. 7B). In contrast, the Ad5luc-L33 and -L1 mutants proved far superior in terms of efficiency of transduction; Ad5luc-L33 uptake by human DC was increased up to 100-fold compared to that of wild-type virus.

DISCUSSION

Ad5 vectors inefficiently transduce several human cells and tissues of therapeutic interest. Higher multiplicities of infection are rarely efficacious and increase the risk of toxicity. Thus, strategies to broaden Ad5 tropism and widen the spectrum of application for Ad5 vectors in clinically relevant targets are actively being pursued.

Virus tropism can be directed towards target cells by incorporating foreign peptide ligands in the capsid proteins. In many cases, however, the incorporated ligands lose specificity and/or affect virion integrity. To address these issues, we expressed a functional Ad5 knob domain on the λ capsid and used it to generate a high-complexity phage-displayed library of ligands in the context of the Ad5 knob. We showed that screening this library identified ligands which maintained their binding properties when incorporated in the Ad5 genome, preserved the structural and biological properties of the knob, and did not alter the CAR-mediated cell entry mechanism. We believe that this Ad5 knob display system can be similarly used for the identification of mutations conferring a desired phenotype to the fiber knob, inhibiting interactions with a receptor, altering in vivo distribution, etc. It must be stressed, however, that expressing the knob homotrimer on the capsid confers a growth reduction on the corresponding phage compared to the wild type. This limits selection to a few panning and amplification rounds before testing the activity of the individual clones.

Pereboev et al. recently reported the display of the Ad5 fiber knob on filamentous phage through a leucine zipper fastener joining the foreign protein to the minor coat protein pIII (29). Here we exploited a λ phage display system to create and survey a library of knob derivatives. This strategy identified mutations capable of dramatically increasing the Ad5 infectivity of various CAR-negative cell types. It is worth emphasizing that in filamentous phage display systems, the fusion protein is transported into and folds in the oxidizing environment of the periplasmic spaces where phage particles assemble before being secreted from the cell. By contrast, in the λ system, fusion protein folding and phage particle assembly take place in the reducing milieu of the cytoplasm, prior to lysis of the bacterial host. These conditions more closely resemble those likely experienced by adenovirus fibers, which assemble in the reducing environment of the mammalian cell nucleus before lysis of the cell; altered redox status might affect the folding and binding properties of the knob mutants.

By screening the phage-displayed knob library, we identified Ad5 knob mutants with an enhanced ability to infect NIH 3T3 cells compared to the parental vector. This nonnative tropism is mediated by the interaction of the virus knob with a still unknown receptor(s) on the target cell. The absence of cross-competition of knobΔL16 protein with the Ad5luc-L1 and -L33 viruses suggests that Ad5luc-L16 targets a receptor different from that used by these two viruses. This conclusion is corroborated by the fact that the ranking of the transduction efficiency of these mutants changes with the target cell.

We showed that this CAR-independent tropism could be activated in different cell types from various species, with no relation to CAR expression. The efficiency achieved by these Ad5 derivatives in transducing various cell types is remarkable. Also relevant is the fact that these Ad5 derivatives retained the full infectivity of the wild-type virus, with amplification rates and virus yields in PerC.6 cells identical to those of the parental vector. Recent data obtained in the laboratory confirm the ability of Adluc-L mutants to efficiently infect a broad range of cell types and also identify cell types which are poorly infected by Ad5luc-L mutants as well as Ad5luc-wt (e.g., human fibroblasts). These results support this strategy as a general methodology for altering Ad5 tropism and widening the therapeutic window of adenoviral vectors for different gene transfer applications.

The same results spurred us to evaluate the efficiency with which the identified Ad5 derivatives transduce DC. DC are key antigen-presenting cells that play a pivotal role in the regulation of antigen-specific immune responses (1). Genetic modification of DC has considerable therapeutic potential as a route to modulate DC function as well as for the treatment of a wide spectrum of diseases, including cancer and persistent viral infection (27). Replication-deficient Ad5 vectors have been exploited as gene transfer vehicles in a variety of DC-based strategies intended to induce active antitumor immunity in both mouse models and clinical trials (13). However, due to the low levels of CAR on DC, high virus doses and prolonged exposure to virus are required for efficient transduction, complicating the broad application of Ad5-infected DC as therapeutic vaccines in the clinic (31). In this report we show that Ad5luc-L33 can transduce human immature DC up to 100-fold better than wild-type virus. Current clinical protocols adopt multiplicities of infection in the range of 104 virus particles per DC (31). According to our data, a 400-fold-lower dose of the Adluc-L33 mutant than of Adluc-wt should be sufficient to achieve the same magnitude of gene expression. Since dose-related cytotoxic effects of adenoviral vectors can compromise potential applications, the Ad5luc-L33 derivative would have definite advantages for the genetic transduction of DC cells. The same Ad5 knob mutant is a promising candidate as a vehicle for vaccination.

Acknowledgments

We thank Olga Minenkova for introduction to lambda cloning and Valentina Salucci and Barbara Cipriani for providing us with mouse and human DC, respectively. We also thank Frank Graham and our colleagues at IRBM for critically reading the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Banchereau, J., and R. M. Steinman. 1998. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature 392:245-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beghetto, E., A. Pucci, O. Minenkova, A. Spadoni, L. Bruno, W. Buffolano, D. Soldati, F. Felici, and N. Gargano. 2001. Identification of a human immunodominant B-cell epitope within the GRA1 antigen of Toxoplasma gondii by phage display of cDNA libraries. Int. J. Parasitol. 31:1659-1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bett, A. J., W. Haddara, L. Prevec, and F. L. Graham. 1994. An efficient and flexible system for construction of adenovirus vectors with insertions or deletions in early regions 1 and 3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:8802-8806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bett, A. J., L. Prevec, and F. L. Graham. 1993. Packaging capacity and stability of human adenovirus type 5 vectors. J. Virol. 67:5911-5921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouri, K., W. G. Feero, M. M. Myerburg, T. J. Wickham, I. Kovesdi, E. P. Hoffman, and P. R. Clemens. 1999. Polylysine modification of adenoviral fiber protein enhances muscle cell transduction. Hum. Gene Ther. 10:1633-1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chartier, C., E. Degryse, M. Gantzer, A. Dieterle, A. Pavirani, and M. Mehtali. 1996. Efficient generation of recombinant adenovirus vectors by homologous recombination in Escherichia coli. J. Virol. 70:4805-4810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chillon, M., A. Bosch, J. Zabner, L. Law, D. Armentano, M. J. Welsh, and B. L. Davidson. 1999. Group D adenoviruses infect primary central nervous system cells more efficiently than those from group C. J. Virol. 73:2537-2540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper, H. M., and Y. Paterson. 1995. Production of antibodies. Current protocols in immunology, vol. 1, unit 2.4.1-2.4.9. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 9.Dokland, T., and H. Murialdo. 1993. Structural transitions during maturation of bacteriophage lambda capsids. J. Mol. Biol. 233:682-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engering, A., T. B. Geijtenbeek, S. J. van Vliet, M. Wijers, E. van Liempt, N. Demaurex, A. Lanzavecchia, J. Fransen, C. G. Figdor, V. Piguet, and Y. van Kooyk. 2002. The dendritic cell-specific adhesion receptor DC-SIGN internalizes antigen for presentation to T cells. J. Immunol. 168:2118-2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fallaux, F. J., A. Bout, I. van der Velde, D. J. van den Wollenberg, K. M. Hehir, J. Keegan, C. Auger, S. J. Cramer, H. van Ormondt, A. J. van der Eb, D. Valerio, and R. C. Hoeben. 1998. New helper cells and matched early region 1-deleted adenovirus vectors prevent generation of replication-competent adenoviruses. Hum. Gene Ther. 9:1909-1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fallaux, F. J., O. Kranenburg, S. J. Cramer, A. Houweling, H. Van Ormondt, R. C. Hoeben, and A. J. van der Eb. 1996. Characterization of 911: a new helper cell line for the titration and propagation of early region 1-deleted adenoviral vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 7:215-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fong, L., and E. G. Engleman. 2000. Dendritic cells in cancer immunotherapy. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18:245-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glaser, S. M., D. E. Yelton, and W. D. Huse. 1992. Antibody engineering by codon-based mutagenesis in a filamentous phage vector system. J. Immunol. 149:3903-3913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harlow, E., and D. Lane. 1988. Antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 16.Hidaka, C., E. Milano, P. L. Leopold, J. M. Bergelson, N. R. Hackett, R. W. Finberg, T. J. Wickham, I. Kovesdi, P. Roelvink, and R. G. Crystal. 1999. CAR-dependent and CAR-independent pathways of adenovirus vector-mediated gene transfer and expression in human fibroblasts. J. Clin. Investig. 103:579-587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishibashi, M., and J. V. Maizel, Jr. 1974. The polypeptides of adenovirus. V. Young virions, structural intermediate between top components and aged virions. Virology 57:409-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katchalski, E., A. Berger, and J. Kurz. 1963. Aspects of protein structure. Academic Press, New York, N.Y.

- 19.Krasnykh, V., I. Dmitriev, G. Mikheeva, C. R. Miller, N. Belousova, and D. T. Curiel. 1998. Characterization of an adenovirus vector containing a heterologous peptide epitope in the HI loop of the fiber knob. J. Virol. 72:1844-1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krasnykh, V. N., J. T. Douglas, and V. W. van Beusechem. 2000. Genetic targeting of adenoviral vectors. Mol. Ther. 1:391-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Legrand, V., D. Spehner, Y. Schlesinger, N. Settelen, A. Pavirani, and M. Mehtali. 1999. Fiberless recombinant adenoviruses: virus maturation and infectivity in the absence of fiber. J. Virol. 73:907-919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li, Y., R. C. Pong, J. M. Bergelson, M. C. Hall, A. I. Sagalowsky, C. P. Tseng, Z. Wang, and J. T. Hsieh. 1999. Loss of adenoviral receptor expression in human bladder cancer cells: a potential impact on the efficacy of gene therapy. Cancer Res. 59:325-330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lutz, M. B., N. Kukutsch, A. L. Ogilvie, S. Rossner, F. Koch, N. Romani, and G. Schuler. 1999. An advanced culture method for generating large quantities of highly pure dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow. J. Immunol. Methods 223:77-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michael, S. I., J. S. Hong, D. T. Curiel, and J. A. Engler. 1995. Addition of a short peptide ligand to the adenovirus fiber protein. Gene Ther. 2:660-668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mikawa, Y. G., I. N. Maruyama, and S. Brenner. 1996. Surface display of proteins on bacteriophage lambda heads. J. Mol. Biol. 262:21-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller, C. R., D. J. Buchsbaum, P. N. Reynolds, J. T. Douglas, G. Y. Gillespie, M. S. Mayo, D. Raben, and D. T. Curiel. 1998. Differential susceptibility of primary and established human glioma cells to adenovirus infection: targeting via the epidermal growth factor receptor achieves fiber receptor-independent gene transfer. Cancer Res. 58:5738-5748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nair, S. K. 1998. Immunotherapy of cancer with dendritic cell-based vaccines. Gene Ther. 5:1445-1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicklin, S. A., D. J. Von Seggern, L. M. Work, D. C. Pek, A. F. Dominiczak, G. R. Nemerow, and A. H. Baker. 2001. Ablating adenovirus type 5 fiber-CAR binding and HI loop insertion of the SIGYPLP peptide generate an endothelial cell-selective adenovirus. Mol. Ther. 4:534-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pereboev, A., L. Pereboeva, and D. T. Curiel. 2001. Phage display of adenovirus type 5 fiber knob as a tool for specific ligand selection and validation. J. Virol. 75:7107-7113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pickles, R. J., D. McCarty, H. Matsui, P. J. Hart, S. H. Randell, and R. C. Boucher. 1998. Limited entry of adenovirus vectors into well-differentiated airway epithelium is responsible for inefficient gene transfer. J. Virol. 72:6014-6023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rea, D., M. J. Havenga, M. van Den Assem, R. P. Sutmuller, A. Lemckert, R. C. Hoeben, A. Bout, C. J. Melief, and R. Offringa. 2001. Highly efficient transduction of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells with subgroup B fiber-modified adenovirus vectors enhances transgene-encoded antigen presentation to cytotoxic T cells. J. Immunol. 166:5236-5244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roelvink, P. W., G. Mi Lee, D. A. Einfeld, I. Kovesdi, and T. J. Wickham. 1999. Identification of a conserved receptor-binding site on the fiber proteins of CAR-recognizing adenoviridae. Science 286:1568-1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Russell, W. C. 2000. Update on adenovirus and its vectors. J. Gen. Virol. 81:2573-2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 35.Sandig, V., R. Youil, A. J. Bett, L. L. Franlin, M. Oshima, D. Maione, F. Wang, M. L. Metzker, R. Savino, and C. T. Caskey. 2000. Optimization of the helper-dependent adenovirus system for production and potency in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:1002-1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Segerman, A., Y. F. Mei, and G. Wadell. 2000. adenovirus types 11p and 35p show high binding efficiencies for committed hematopoietic cell lines and are infective to these cell lines. J. Virol. 74:1457-1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sternberg, N., and R. H. Hoess. 1995. Display of peptides and proteins on the surface of bacteriophage lambda. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:1609-1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takamizawa, A., C. Mori, I. Fuke, S. Manabe, S. Murakami, J. Fujita, E. Onishi, T. Andoh, I. Yoshida, and H. Okayama. 1991. Structure and organization of the hepatitis C virus genome isolated from human carriers. J. Virol. 65:1105-1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tomko, R. P., R. Xu, and L. Philipson. 1997. HCAR and MCAR: the human and mouse cellular receptors for subgroup C adenoviruses and group B coxsackieviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:3352-3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wickham, T. J., P. Mathias, D. A. Cheresh, and G. R. Nemerow. 1993. Integrins alpha v beta 3 and alpha v beta 5 promote adenovirus internalization but not virus attachment. Cell 73:309-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wickham, T. J., D. M. Segal, P. W. Roelvink, M. E. Carrion, A. Lizonova, G. M. Lee, and I. Kovesdi. 1996. Targeted adenovirus gene transfer to endothelial and smooth muscle cells by with bispecific antibodies. J. Virol. 70:6831-6838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xia, H., B. Anderson, Q. Mao, and B. L. Davidson. 2000. Recombinant human adenovirus: targeting to the human transferrin receptor improves gene transfer to brain microcapillary endothelium. J. Virol. 74:11359-11366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yokoyama, W. M. 1995. Production of monoclonal antibodies. Current protocols in immunology, vol. 1, unit 2.5.1-2.5.17. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 44.You, Z., D. C. Fischer, X. Tong, A. Hasenburg, E. Aguilar-Cordova, and D. G. Kieback. 2001. Coxsackievirus-adenovirus receptor expression in ovarian cancer cell lines is associated with increased adenovirus transduction efficiency and transgene expression. Cancer Gene Ther. 8:168-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zabner, J., P. Freimuth, A. Puga, A. Fabrega, and M. J. Welsh. 1997. Lack of high affinity fiber receptor activity explains the resistance of ciliated airway epithelia to adenovirus infection. J. Clin. Investig. 100:1144-1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhong, L., A. Granelli-Piperno, Y. Choi, and R. M. Steinman. 1999. Recombinant adenovirus is an efficient and nonperturbing genetic vector for human dendritic cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 29:964-972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]