Abstract

Large-scale genomic rearrangements including inversions, deletions, and duplications are significant in bacterial evolution. The recently completed Brucella melitensis 16M and Brucella suis 1330 genomes have facilitated the investigation of such events in the Brucella spp. Suppressive subtractive hybridization (SSH) was employed in identifying genomic differences between B. melitensis 16M and Brucella abortus 2308. Analysis of 45 SSH clones revealed several deletions on chromosomes of B. abortus and B. melitensis that encoded proteins of various metabolic pathways. A 640-kb inversion on chromosome II of B. abortus has been reported previously (S. Michaux Charachon, G. Bourg, E. Jumas Bilak, P. Guigue Talet, A. Allardet Servent, D. O'Callaghan, and M. Ramuz, J. Bacteriol. 179:3244-3249, 1997) and is further described in this study. One end of the inverted region is located on a deleted TATGC site between open reading frames BMEII0292 and BMEII0293. The other end inserted at a GTGTC site of the cyclic-di-GMP phosphodiesterase A (PDEA) gene (BMEII1009), dividing PDEA into two unequal DNA segments of 160 and 977 bp. As a consequence of inversion, the 160-bp segment that encodes the N-terminal region of PDEA was relocated at the opposite end of the inverted chromosomal region. The splitting of the PDEA gene most likely inactivated the function of this enzyme. A recombination mechanism responsible for this inversion is proposed.

Brucella species often infect a wide range of hosts (2). Brucella melitensis causes abortion in sheep and goats, whereas Brucella abortus does so in cattle. Both species are responsible for human brucellosis, a multisystemic disease characterized by fever, endocarditis, arthritis, and osteomyelitis (1). Recently, the genomes of B. melitensis (6) and Brucella suis (26) have been completely sequenced and annotated, while that of B. abortus is at the later stages of completion. Genome comparison may elucidate the molecular basis of host specificity among the different Brucella strains and will certainly elucidate phylogenetic and evolutionary relationships.

Evolution of pathogenic variants from nonpathogenic or less virulent strains is well documented in many bacterial species (32). Similarly, distinct disease-causing mechanisms are inherent in several bacterial species, and their presence depends on the ability of commensal strains to acquire virulence genes (3, 10). Thus, comparative genomics of closely related species of pathogens may associate specific genes with particular diseases. Elucidation of genomic similarities and differences, along with proteomic approaches, may ultimately determine host specificity, virulence, and other phenotypic traits. Comparison of genomic sequence data among bacterial strains using suppressive subtractive hybridization (SSH) is one of the most effective methods for identifying genes and their regulatory regions.

In the present study, reciprocal SSH was accomplished by hybridizing AluI genomic DNA digests of B. melitensis 16M and B. abortus 2308 to compare their genomes. For brevity, B. melitensis 16 M and B. abortus 2308 will be referred to as 16M and 2308, respectively. Complementary sequences, common to both tester and driver DNA, formed hybrids. Those fragments unique to the tester DNA were cloned and further analyzed. Using SSH and differential DNA hybridization analysis that utilize a high-throughput library screening, we selectively amplified and identified DNA sequences that are unique to the B. melitensis or B. abortus genome. An adaptor-linked PCR method was developed to determine genomic differences in the flanking regions of a tester-specific SSH clone. This inversion split the cyclic-di-GMP phosphodiesterase A (PDEA) gene into two unequal fragments, possibly affecting several downstream metabolic pathways. This study provides molecular evidence for the exact location of the 640-kb chromosome II inversion and recombinational events in B. abortus strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

A total of 174 Brucella isolates selected according to species were screened in this study: 36 B. melitensis isolates, 54 B. abortus isolates, 41 B. suis isolates, 12 Brucella canis isolates, 1 Brucella neotomae isolate, and 21 Brucella ovis isolate. Nine unclassified marine mammal Brucella isolates (six from seals and three from dolphins) were also analyzed (supplementary Table A, available at http://www.proteome.scranton.edu/).

DNA isolation.

Chloroform-killed cells of Brucella were washed three times by suspending cells in 1 ml of 10 mM MgCl2 followed by centrifugation at 2,130 × g for 10 min. The bacterial pellet was resuspended in 500 μl of TE buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl, 1 mM EDTA), frozen in liquid nitrogen for 30 s, and placed in boiling water for 2 min. Addition of 10 μl of lysozyme (10 mg/ml) at 37°C for 30 min, 10 μl of RNase A (10 mg/ml) at 37°C for 30 min, 30 μl of 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate with 3 μl of proteinase K (20 mg/ml) at 37°C for 1 h, and polysaccharide degradation (100 μl of 5 M NaCl and 80 μl of hexadecyltrimethyl ammonium bromide-NaCl solution [24]) at 65°C for 10 min were carried out in that order. An equal volume of 1:1 phenol-chloroform (∼750 μl) was added, and the mixture was centrifuged at 3,330 × g for 15 min. The upper aqueous layer containing the DNA was collected and reextracted with equal volumes of chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1) in order to purify the DNA from phenol residues. The DNA was precipitated by the addition of a 0.6 volume of isopropanol at room temperature for 30 min, with centrifugation at 16,100 × g. The pellet was then washed with 70% ethanol, air dried at 37°C for 15 min, resuspended in deionized water, quantified, dispensed into aliquots, and maintained at −20°C. Plasmid DNA was prepared using a Bio Robot 9600 station (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. All other chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.).

Suppressive subtractive hybridization.

SSH was performed using a PCR-Select bacterial genome subtraction kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.). The protocol was modified by replacing RsaI with AluI (Promega, San Louis Obispo, Calif.) to digest genomic DNA, followed by column DNA purification (Qiagen, Chatsworth, Calif.). AluI-generated DNA fragments of 0.3 to 1.5 kb were used for DNA cloning and SSH analysis.

Construction and analysis of clones from the subtracted libraries.

Amplified PCR tester-specific DNA sequences were cloned into a pCR2.1 vector (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, Calif.) and transformed into Escherichia coli Top10 competent cells. The cells were plated onto semisolid Luria-Bertani medium (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) supplemented with kanamycin, 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-d-galactoside, and isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (Sigma Chemical Co.) and grown overnight at 37°C. A library composed of 2,592 positive clones was constructed for each SSH reaction.

Arrays for differential plasmid DNA hybridization were performed in duplicate, using a 96-pin metal spotting device (VP Scientific, San Diego, Calif.) to deliver 1 μl of plasmid DNA from the above-described clones onto a Nytran Supercharge nylon membrane (Schleicher & Schuell Inc., Keene, N.H.) according to the method of Liang et al. (20). DNA was denatured by placing the membrane on 3MM Whatman paper saturated with a solution of 0.5 M NaOH containing 1.5 M NaCl for 15 min. The membrane was washed with 1 M Tris HCl (pH 7.4) containing 1.5 M NaCl and rinsed with 2× standard saline citrate (0.3 M sodium citrate, 3 M NaCl [pH 7.0]; Sigma Chemical Co.). The membranes were exposed to 120 mJ of UV radiation using a UV Stratalinker2400 (Stratagene, Cedar Creek, Tex.). Chromosomal DNA of 16M and 2308 was digested with AluI, followed by column DNA purification, and then biotinylated (KPL, Gaithersburg, Md.). The membranes were prehybridized for 4 h and hybridized overnight with equal amounts of the above-described biotinylated probes. Washing of the membranes and visualization of hybridization signals with streptavidin-luminol-peroxide conjugate on Kodak X-ray film were accomplished using the North2South chemiluminescent nucleic acid hybridization and detection kit (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.). All experiments were performed in duplicate, and each clone was arrayed in triplicate.

Southern hybridization.

AluI digests of 2 μg of genomic DNA from each Brucella strain were electrophoresed in a 0.7% (wt/vol) agarose gel containing TBE buffer (89 mM Tris borate, 2 mM EDTA [pH 8.3]). DNA was blotted onto a nylon membrane using the VacuGene XL (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.). Membranes were prehybridized and hybridized as described previously. Probes were prepared by first digesting plasmid DNA with EcoRI that cleaved the cloned insert from the plasmid vector. The digests were run in a 0.8% (wt/vol) agarose gel containing TAE buffer (40 mM Tris-acetate and 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.3]). The inserts were isolated and purified using gel extraction purification columns (Qiagen) and were biotinylated prior to hybridization.

Generation of DNA adaptor-linked digests.

The cohesive-end generating restriction endonuclease enzymes (REE) NsiI, SphI, or FseI (New England Biolabs) were used to digest 2308 genomic DNA in 50 μl containing 5 μl of 10× REE buffer, 1,200 ng of DNA, 5 U of REE, and 0.5 μl of 10-μg/ml bovine serum albumin (for FseI digestions only) for 4 h at 37°C and then purified by a nucleotide column (Qiagen). Each DNA digest was ligated to the adaptors at room temperature for 5 min in a reaction mixture of 100 μl containing (e.g., for NsiI digests) 50 μl of Quick ligation buffer, 3.5 μl of primer PAOK-NsiI-12 (20 pM/μl), 7 μl of primer PAOKARA-24 (20 pM/μl) (supplementary Table B), and 5 μl of Quick T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs). Prior to the addition of the Quick T4 DNA ligase, annealing of the 12-mer and 24-mer oligonucleotide primers to form the adaptor was achieved by heating at 50°C for 1 min and then cooling to 10°C at 1°C per min. Inactivation of the Quick T4 DNA ligase was accomplished by heating the mixture at 65°C for 10 min.

Oligonucleotide primers.

The oligonucleotides used in this study (supplementary Table B [see the above URL]) were purchased from MWG Biotech Inc. (High Point, N.C.). All 12-mer primers were designed to complement the universal 24-mer in order to ensure the correct polarity of ligation with the cohesive-ended genomic DNA fragments. The recessed ends of the ligated DNA fragments were filled in during the first round of PCR amplification. Primers for PCR amplification were designed to anneal at 68°C according to the method of Wallace et al. (34).

PCR amplification.

PCR was performed using 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 s and annealing and extension at 68°C for 2 to 15 min. All thermocycling and amplification reactions were carried out by utilizing the Perkin-Elmer 9700 DNA thermal cycler. The 50-μl amplification mixture contained 2.5 U of MasterAmp Extra-Long DNA polymerase (Epicentre, Madison, Wis.), 25 μl of MasterAmp Extra-Long PCR 2× Premix 4, 1 μl (50 pM/μl) of each oligonucleotide primer, and 10 ng of REE DNA adaptor-linked digest. An initial 2-min adaptor extension at 68°C, 2-min denaturation at 95°C, and a final 10-min extension at 68°C were included in the program.

Detection of the B. abortus chromosome II inversion by PCR.

The PCR mixtures (50 μl) contained 0.8 μl of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (5 mM; Q-Biogene, Inc., Carlsbad, Calif.), 5 μl of 10× reaction buffer [16 mM (NH4)2SO4, 70 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.8], 0.1% Tween 20], 0.5 μl of TaqDNA polymerase (isolated from Thermus aquaticus, Biolase, 5 U/μl; Bioline USA Inc., Springfield, N.J.), 2 mM MgCl2, 1 μl of template genomic DNA (∼300 ng) and 1 μl (35 pM/μl) of each oligonucleotide primer (1997+F, 195M1F, 1996+R, and 195M2R), (Tables 1 and 2). The amplification protocol consisted of 2 min of denaturation at 95°C followed by 20 cycles of 15 s at 95°C (denaturation), 10 s at 68°C (annealing), 30 s at 72°C (extension), with a final 10-min extension at 72°C.

TABLE 1.

SSH clones representing various deletions in B. melitensis 16M and B. abortus 2308

| Clone no.a | Size (bp) | Chromo- some | ORFb | Chromosomal positionc

|

Accession no.d | Functione | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | End | ||||||

| c15 | 438 | I | BMEI0888 | 919647 | 920084 | AAL52069 | Peptidyl-prodyl cis-trans isomerase A (EC 5.2, 1.8) |

| d5, d52 | 506 | I | BMEI0929 | 961350 | 961855 | AAL52110 | Diguanylate cylase/phosphodiesterase domain 1 (GGDEF) |

| p38 | 278 | I | BMEI0943 | 975996 | 976273 | AAL52124 | Vitamin B-12-dependent ribonucleotide reductase |

| g9 | 552 | I | BMEI0971 | 1012220 | 1012771 | AAL52152 | Phospho-2-dehydro-3-deoxyheptonate aldolase |

| h3 | 717 | I | BMEI1055 | 1097186 | 1097902 | AAL52236 | Penicillin-binding protein 1A |

| k49 | 330 | I | BMEI1125 | 1168696 | 1169025 | AAL52306 | Maleypyruate isomerase |

| m47 | 344 | I | BMEI1331 | 1386637 | 1386980 | AAL52512 | Cytochrome C-type biogenes is protein CYCL precursor |

| n10 | 293 | I | BMEI1380 | 1433213 | 1433505 | AAL52561 | Choline dehydrogenase |

| i29 | 135 | I | BMEI1661 | 1713277 | 1713411 | AAL52842 | Recombinase |

| i35, i55 | 827 | I | BMEI1661 | 1713416 | 1714242 | AAL52842 | Recombinase |

| r1 | 250 | I | BMEI1919 | 1976138 | 1976387 | AAL53100 | Acyltransferase |

| r14 | 424 | I | BMEI1921 | 1977166 | 1977589 | AAL53102 | Acetoacetyl-CoA synthetase |

| r37 | 702 | I | BMEI1921 | 1976888 | 1977589 | AAL53102 | Acetoacetyl-CoA synthetase |

| f44 | 496 | II | BMEII0292 | 305523 | 306018 | AAL53534 | Response regulator protein |

| e8, e26, e32 | 681 | II | BMEII0717 | 756361 | 757041 | AAL53959 | Hemagglutinin |

| e41 | 492 | II | BMEII0722 | 759646 | 760137 | AAL53964 | Hypothetical protein |

| a18, a24 | 775 | II | BMEII0827 | 860610 | 861384 | AAL54069 | Glucose-1-phosphate cytidylyltransferase |

| a17, a22, a33 | 677 | II | BMEII0828 | 861389 | 862065 | AAL54070 | Possible S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferase |

| a28 | 119 | II | BMEII0829 | 862869 | 862987 | AAL54071 | Possible S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferase |

| a16, a25 | 360 | II | BMEII0832 | 865327 | 865686 | AAL53972 | UDP-glucose 4-epimerase (EC 5,1.3.2) |

| a63 | 701 | II | BMEII0840 | 869539 | 870239 | AAL54082 | Glycosyltransferase involved in cell wall biogenesis |

| a23 | 668 | II | BMEII0840 | 871848 | 872515 | AAL54082 | Glycosyltransferase involved in cell wall biogenesis |

| a65, a34 | 464 | II | BMEII0843 | 878906 | 879369 | AAL54085 | Putative colanic acid biosynthesis acetyltransferase WCAF |

| a30, a36 | 256 | II | BMEII0845 | 880064 | 880319 | AAL54087 | Lipopolysaccharide N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase |

| a45, a48, a42 | 566 | II | BMEII0845 | 880324 | 880889 | AAL54087 | Lipopolysaccharide N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase |

| a6, a13 | 362 | II | BMEII0848 | 884572 | 884933 | AAL54090 | GDP-mannose 4,6-dehydratase (EC 4.2.1.47) |

| a27, a31, a64 | 560 | II | BMEII0848 | 884938 | 885497 | AAL54090 | GDP-mannose 4,6-dehydratase (EC 4.2.1.47) |

| o17 | 857 | I | BR1852 | 1782925 | 1783781 | AAN30747 | Transcriptional regulator, Cro/CI family |

| o2, o8 | 343 | I | BR1853 | 1784537 | 1784879 | AAN30748 | AzlC family protein |

ORFs designated as BME and BR are from B. melitensis 16M and B. abortus 2308, respectively.

Clones appearing in a single row that are designated by the same letter but different numbers were sequenced independently but later found to be identical. Clone names were arbitrarily assigned.

Nucleotide positions in either chromosome I or II indicating the start and end sites of deleted region.

GenBank protein accession numbers.

CoA, coenzyme A.

TABLE 2.

Sequence analysis of PCR products from PCR-amplified regions of B. abortus 2308a

| PCR product | Accession no.b | Size (bp) | Oligonucleotide primerc

|

Corresponded sequences located on B. melitensis 16M genomed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | ||||

| A1 | AF542417 | 7,368 | 1997+F | PAOK-SphI-R | Chr. 306858-306970 plus 1047279-1039998 |

| A2 | AF537297 | 1,453 | 1998A2F | PAOK-NsiI-R | Chr. 305088-305240 plus 306078-306970 plus 1047279-1046873 |

| B1 | AF537298 | 1,062 | 195F | PAOK-SphI-R | Chr. 1047344-1047275 plus 306976-307967 |

| B2 | AF537299 | 1,481 | 195F | PAOK-FseI-R | Chr. 1047344-1047275 plus 306976-308385 |

| E | AE009733 | 488 | 195M1F | 195M2R | Chr. 1047436-1046949 |

| F | AE009667 | 250 | 1997+F | 1996+R | Chr. 306858-307107 |

| G | AE009733 | 440 | 1997+F | 195M2R | Chr. 306858-306970 plus 1047275-1046949 |

| AE009667 | |||||

| H | AE009733 | 293 | 195M1F | 1996+R | Chr. 1047436-1047275 plus 306976-307107 |

| AE009667 | |||||

The PCR products A1 to H correspond to the electrophoresed DNA fragments shown in Fig. 1 and supplementary Fig. D.

GenBank nucleotide accession numbers.

See supplementary Table B for nucleotide sequence.

Chr., chromosomal position.

Sequence analysis.

DNA sequencing of PCR products and inserts of plasmids were conducted by MWG Biotech Inc. Sequence data were analyzed using the MapDraw, EditSeq, SeqMan, and MegAlign programs from the DNA-Star nucleotide sequence analysis package and were searched against the B. melitensis 16 M genome available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (http://www.ncbi.n/m.nih.gov).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The accession numbers for the sequences determined in this study are given in Tables 1 and 2.

RESULTS

Deletions in B. abortus and B. melitensis genomes.

Reciprocal SSH was used to identify genomic DNA differences between 16M and 2308. Tester-specific sequences were cloned, and a DNA library consisting of 2,592 clones was constructed. Dot blot hybridization of the clones was performed to test the specificity of the DNA fragments, using the AluI-digested and biotinylated 16M and 2308 chromosomal DNAs as probe. The end sequences of these clones were determined, blasted against the 16M genome, and then used as biotinylated probes for Southern hybridization of the AluI-digested genomic DNA of 16M and 2308. A total of 45 SSH clones were analyzed by Southern hybridization, 42 of which were specific to 16M and three of which were specific to 2308 (Table 1). Deletions on both chromosomes were detected following analysis of all 45 clones. Fifteen clones indicated deletions in 10 different locations on chromosome I, whereas 30 clones indicated deletions in four distinct regions of chromosome II, 27 of which specified deletions in 2308 and 3 of which specified deletions in 16M. Clone designations were thus assigned in an arbitrary fashion to distinguish them according to location in a specific region.

(i) Chromosome I deletions.

Two “d” clones (d5 and d52) revealed a 1.2-kb deletion (supplementary Fig. A) that disrupted BMEI0929, which encodes diguanylate cyclase, which is metabolically associated with PDEA. The 13 other SSH clones identified deletions in nine different locations on chromosome I of 2308. These deletions affected the following proteins: peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase, diguanylate cyclase-phosphodiesterase domain, Vit B12-dependent ribonucleotide reductase, aldolase, penicillin-binding protein 1A, maleylpyruvate isomerase, cytochrome C-type protein precursor, choline dehydrogenase, recombinase, acyltransferase, and acetoacetyl-coenzyme A synthetase. Future analysis of the flanking regions will estimate the exact sizes of the deleted regions in the 2308 genome.

(ii) Chromosome II deletions.

Analysis of 22 “a” clones revealed various deletions between BMEII0821 and BMEII0854 of 2308 representing the following proteins: glucose-1-phosphate cytidylyltransferase, S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferase, epimerase, glycosyl transferase, acetyltransferase WCAF, N-acetylglucosamine transferase, and GDP-mannose 4,6-dehydratase (Table 1). A 25-kb deletion was previously reported in this region (33). Four “e” clones showed deletions in a highly plastic region of the genome that includes the hemagglutinin gene (BMEII0717) surrounded by two IS elements and seven transposases. An e41 clone identified the deletion of BMEII0722 encoding a hypothetical protein. All SSH clones found in the 2308 chromosome II indicated deletions only in the 640-kb inverted genomic region. Of the 45 SSH clones, only three “o” clones revealed deletions in 16M. These deletions represented a transcriptional regulator of the Cro/Cl family and a protein from the AzlC family.

Localization of the 837-bp deletion on chromosome II of B. abortus.

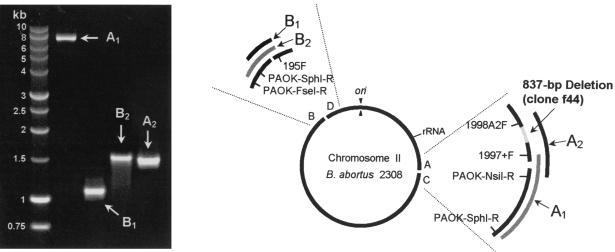

Analysis of the f44 clone indicated an 837-bp deletion and the endpoint of the 640-kb inversion previously described for B. abortus (22). The 837-bp deletion is located 950 bp downstream of the f44 sequence and disrupted BMEII0291 and BMEII0292, encoding an aminobutyraldehyde dehydrogenase and a response regulator protein, respectively. To determine the exact location of the deletion that was detected in clone f44 within the 2308 genome (supplementary Fig. B), an adaptor-linked PCR method was developed. NsiI-, SphI-, or FseI-cleaved genomic 2308 DNA were ligated to site-specific oligonucleotide adaptors (supplementary Table B). The REEs cleaved the 2308 genomic DNA into average fragments of 7 to 10 kb long. Long-range DNA polymerase together with forward oligonucleotide primers were used in targeting upstream and downstream sequences of clone f44 that are similar to the 16M genome sequences. Reverse primers were designed for each of the restriction endonuclease sites (Table 2 and Fig. 1). PCR amplification generated a 7,368-bp DNA fragment (A1) from SphI digests and a 1,453-bp DNA fragment (A2) from NsiI digests (Table 2 and Fig. 1). Sequence analysis of the A2 PCR product localized the full 837-bp deletion in region A.

FIG. 1.

Agarose gel electrophoresis analysis and schematic illustration of PCR-amplified regions of B. abortus 2308 using adaptor-linked PCR. Direct sequencing of these DNA fragments revealed an 837-bp deletion (A2) and detected the two endpoints of the 640-kb inversion (A1, B1, and B2) (see also Tables 1 and 2).

Molecular analysis of the 640-kb inversion.

DNA sequence analysis of the A2 PCR products revealed the presence of a 160-bp DNA segment located downstream of BMEII0292 (Fig. 1, region A). This 160-bp segment corresponds to the 5′ region of BMEII1009, encoding the N-terminal portion of the protein PDEA in 16M. A similar observation was noted when the A1 PCR products were analyzed, confirming the presence of a portion of the PDEA gene downstream of region A (Fig. 1 and 2). The above results were unexpected, since for B. melitensis, the location of the PDEA gene is approximately 640 kb downstream of region A. To investigate the possibility that the PDEA gene was split in B. abortus, the region where BMEII1009 was suspected to be present was sequenced. The predicted site was based on the location of BMEII1009 in the annotated 16M genome (6). A forward oligonucleotide primer (195F) was designed that targeted the upstream region of the BMEII1009 gene in 2308 (Fig. 1). Sequence analysis of B1 and B2 PCR products established that the truncated 3′ region of the gene encoding the C-terminal portion of PDEA in 2308 is indeed present upstream of BMEII0293 (Fig. 2, region B).

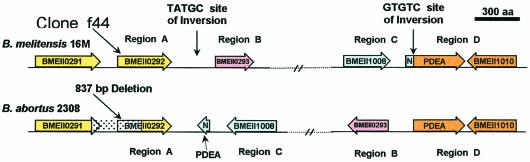

FIG. 2.

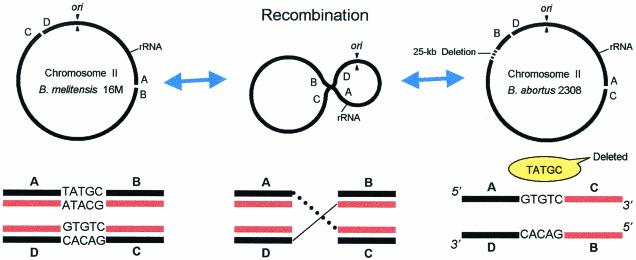

Schematic model showing the proposed mechanism of recombination on chromosome II based on the detailed analysis of the inverted sequence endpoints in B. melitensis 16M and B. abortus 2308.

This indicated that whereas the sequence of the PDEA gene is intact on chromosome II of B. melitensis (open reading frame [ORF] BMEII1009), the gene was split into two unequal and separate regions of 160 and 977 bp in 2308. A schematic diagram of the gene organization and the molecular events that could have led to the separation of the PDEA gene due to the large 640-kb chromosomal inversion and recombination is illustrated in Fig. 2 and 3. The first endpoint of the inversion (Fig. 3, A and B) was located on a deleted TATGC site between BMEII0292, which encoded a response regulator protein, and BMEII0293, which encoded a hypothetical protein. The second endpoint (Fig. 3, C and D) was located inside BMEII1009, which encoded the PDEA gene at the GTGTC site. This site was maintained on both endpoints. After inversion, the truncated PDEA genes are distantly located on the opposite sides of chromosome II and are most likely inactive.

FIG. 3.

Scaled diagram of the ORFs located upstream and downstream of the PDEA gene, indicating two inversions sites (TATGC and GTGTC) on chromosome II of B. melitensis. The intact PDEA gene, flanked by BMEII1008 and BMEII1010, is present in B. melitensis. In B. abortus, the 640-kb inversion splits the PDEA gene into two unequal segments that resulted in the relocation of the smaller 160-bp segment that encodes the N terminus of PDEA. The truncated and relocated PDEA gene (N) is flanked by BMEII0292 and BMEII1008 in B. abortus. The 837-bp deleted segment of BMEII0292 in B. abortus was detected using SSH clone f44. Regions A, B, C, and D represent segments of DNA that include the intergenic regions between the various ORFs.

The inversion was detected by Southern hybridization (supplementary Fig. C) using PCR-amplified DNA sequence of BMEII1009 as a biotinylated probe. This assay discriminated Brucella isolates that have inversion from those without the inversion (supplementary Fig. E). In addition, a multiplex PCR was developed to detect rapidly this inversion among all Brucella species (supplementary Fig. D). A total of 174 Brucella isolates (supplementary Table A) were screened by both methods, and inversion was confirmed in 54 B. abortus field isolates (biotypes 1 and 4) from infected cattle, bison, and elks. The other 120 Brucella field isolates, representing B. melitensis, B. suis, B. canis, B. neotomae, B. ovis, and those from sea mammals, have no inversion (supplementary Fig. E).

DISCUSSION

SSH has proven to be a powerful tool in the identification of disease-related, tissue-specific, and differentially expressed genes in higher organisms (7). It is also valuable in comparative genomics studies of microorganisms due to its high efficiency and sensitivity in identifying species- and strain-specific DNA sequences. However, SSH does not detect rearrangements such as inversions, duplications, or DNA transfer from one location of the genome to another. Since the DNA sequences involved in these chromosomal differences do not overlap, it is impossible to know whether they are part of a large deletion or if they come from the same genomic region. Therefore, an adaptor-linked PCR method was developed, based on the modified protocol of representational difference analysis of cDNA (12), to pinpoint genomic rearrangements 15 to 20 kb upstream or downstream of a tester-specific SSH clone. Since the 16M genome is now completely annotated (6), it has greatly facilitated the analysis of SSH clones that were specific to 16M but were absent in 2308.

The number of deletions detected on chromosome II of 2308 is extensive and most likely altered its overall metabolism. This can be inferred from a comparative global proteome analysis of laboratory-grown 16M and 2308 (V. G. DelVecchio et al., unpublished data). At the proteome level, significant differences in both the number of protein spots and their qualitative and quantitative expression patterns were found between 16M and 2308. Thus, at the protein level, it is possible to distinguish 2308 from 16M just by looking at their proteomes. Such metabolic differences were also described by Paulsen et al. (26) from their in silico comparison of chromosomal deletions between B. melitensis and B. suis. It was suggested that such metabolic differences may in part be the basis for differential biotyping of the different Brucella spp (26).

Michaux-Charachon et al. (22) first reported the 640-kb inversion on chromosome II of B. abortus using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Although they were able to identify its location on chromosome II, no further molecular analysis of the inversion was reported. To our knowledge, this is the first report to determine precisely the ORFs and the DNA sequences at the two endpoints of the inverted region. Based on our SSH data and sequence analysis, the inverted region in 16M was exactly 740,310 bp, or about 100.3 kb greater than the 640 kb previously estimated by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (22). Similar to what we have found in this study, Vizcaino et al. (33) also reported that one of these deletions is a 25-kb segment located between BMEII0821 and BMEII0854, which included the Omp31 gene. Verification of the exact size of inversion (640 or 740 kb) and the detailed location of several deletions within the two chromosomes will come from a completely sequenced and annotated B. abortus genome. The inversion and homologous recombination on chromosome II of B. abortus did not take place at the rrn loci (22), as described previously for other bacteria (11, 21). Rather, the DNA sequence at the junctions of the 740-kb inversion showed double-stranded breaks (DSBs) with a cleaved TATGC site at the AB junction (between BMEII0292 and BMEII0293) and a cohesive GTGTC cleavage at the CD junction (between BMEII1008 and BMEII1010) (Fig. 3).

The 640-kb inversion on chromosome II of 2308 and the splitting of the PDEA gene with the subsequent inactivation of its product may have affected several downstream biochemical pathways. PDEA is one of two enzymes that regulates the level of free cyclic-di-GMP in the cell by catalyzing its degradation to the inactive pGpG (28). For Gluconacetobacter xylinus, cyclic-di-GMP is an allosteric activator of cellulose synthase, a key enzyme in the cellulose-synthesizing complex (29). Although ORFs encoding cellulose synthase catalytic subunits are present in 16M (ORF 1606 and 4528) and B. abortus (ORF 1078), we are not certain if the cellulose pathway is operative in these organisms. There are two copies of the PDEA gene in 16M. Since the B. abortus genome is not completely annotated, the number of PDEA genes in this organism is not known. For G. xylinus, three distinct operons, each containing a PDEA-diguanylate cyclase pair, contribute to different levels of cyclic-di-GMP turnover (31).

Inversions of various lengths are well documented for several closely related species of bacteria. An inversion encompassing about 50% of the genome was reported for strains NCDO763 and MG1363 of Lactococcus lactis (5). One of the five isolates of Mycoplasma hominis has a 300-kb inversion (18). It is also interesting that a small inversion of 720 bp affected the host range specificity of the phytopathogenic Erwinia carotovora (25).

Homologous recombination is a system that requires DNA replication when either the template DNA is damaged or the replication machinery malfunctions (9, 17). In E. coli, the model proposed by Smith (30) can be applied to transduction, transformation, and repair of DSBs. Based on current knowledge of DNA replication and recombination, a mechanism is proposed to elucidate the possible molecular events associated with the 640-kb inversion on chromosome II of B. abortus. During replication of chromosome II, the clockwise replication fork (RF) possibly collapsed or was broken at the AB junction (Fig. 2 and 3) due to DSB and deletion of the TATGC site. The counterclockwise RF also collapsed or broke at the CD junction (Fig. 2 and 3), possibly through the action of an unknown endonuclease (denoted by ellipses) that cleaved a 5′-…NNN↓GTGTC↑NNN…-3′ target site. Both DSB ends unwound the duplex strands to yield recombinogenic single-stranded-DNA tails. Consequently, DSBs triggered DNA replication, leading to DSB repair. RF progress appears to depend on the presence of negative supercoiling in the DNA segment to be replicated, which is characteristic of intrachromosomal recombination (17, 19). Because of the nicks or DSBs on the junctions described above, negative supercoiling results in front of the RF. Loss of supercoiling might inhibit RF progress. Collapsed or broken RFs are repaired via homology-guided invasion of the double-strand end into the intact sister duplex, reassembling the fork structure (Fig. 2 and 3). The model is based on the recombination dependence of cells that experience replication-induced chromosomal fragmentation and on the apparent ability of homologous recombination to generate new RFs (15-17, 23).

Nonhomologous end joining of DNA is another system of DSB repair in eukaryotic cells that requires a DNA end-binding component, called Ku (8). Bacterial Ku homologs have been described recently for Bacillus subtilis. The homologs retain the biochemical characteristic of the eukaryotic Ku heterodimer, which specifically recruits DNA ligase to DNA ends for DSB repair. This characteristic suggests that the DNA repair pathway arose before the divergence of the prokaryotic-eukaryotic lineages (35). Recombination enzymes also play a vital role in the repair of DNA strand nicks or DSBs. The enzymes function via different pathways that mediate break repair, as well as restoration of damaged RFs (27). The enzymatic reactions associated with recombination that resulted in the 640-kb inversion may be studied experimentally by in vitro chromosome surgery (13, 14). However, the mechanisms associated with recombination in relation to cellular function and DNA metabolism are still poorly understood (4).

Conclusions.

The 640-kb inversion and the large number of deletions observed on chromosome II of B. abortus raise an important question as to the degree of genome plasticity in this organism and other Brucella species. Although the inversion most likely inactivated the PDEA gene and possibly altered the overall metabolism of B. abortus, the chromosomal mutation was tolerated from an evolutionary viewpoint. It is tempting to speculate that this large inversion coupled with various deletions resulted in the adaptation of the ancestral Brucella to a new host. The question still remains as to what signal triggered this event, i.e., is it random or host induced? Large chromosomal changes including inversions and deletions may cause an organism to evolve and find another niche in a new environment or host. Such changes would allow the organism to adapt to a new set of circumstances and thereby ensure the successful survival of the species.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by research grant no. DE-FG02-00ER62773 from the U.S. Department of Energy.

We thank Tabbi Miller for critically reading and editing the manuscript and Frank Estock for formatting supporting data. We also thank N. J. Commander, S. J. Cuttler, J. J. Letesson, A. P. MacMillan, and D. O'Callaghan for kindly providing Brucella strains and genomic DNA examined in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bercovich, Z. 1998. Maintenance of Brucella abortus-free herds: a review with emphasis on the epidemiology and the problems in diagnosing brucellosis in areas of low prevalence. Vet. Q. 20:81-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boschiroli, M. L., V. Foulongne, and D. O'Callaghan. 2001. Brucellosis: a worldwide zoonosis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 4:58-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cornelis, G. R., A. Boland, A. P. Boyd, C. Geuijen, M. Iriarte, C. Neyt, M. P. Sory, and I. Stainier. 1998. The virulence plasmid of Yersinia, an antihost genome. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1315-1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox, M. M. 2001. Historical overview: searching for replication help in all of the rec places. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:8173-8180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daveran Mingot, M. L., N. Campo, P. Ritzenthaler, and P. Le Bourgeois. 1998. A natural large chromosomal inversion in Lactococcus lactis is mediated by homologous recombination between two insertion sequences. J. Bacteriol. 180:4834-4842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DelVecchio, V. G., V. Kapatral, R. J. Redkar, G. Patra, C. Mujer, T. Los, N. Ivanova, I. Anderson, A. Bhattacharyya, A. Lykidis, G. Reznik, L. Jablonski, N. Larsen, M. D'Souza, A. Bernal, M. Mazur, E. Goltsman, E. Selkov, P. H. Elzer, S. Hagius, D. O'Callaghan, J. J. Letesson, R. Haselkorn, N. Kyrpides, and R. Overbeek. 2002. The genome sequence of the facultative intracellular pathogen Brucella melitensis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:443-448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diatchenko, L., Y. F. Lau, A. P. Campbell, A. Chenchik, F. Moqadam, B. Huang, S. Lukyanov, K. Lukyanov, N. Gurskaya, E. D. Sverdlov, and P. D. Siebert. 1996. Suppression subtractive hybridization: a method for generating differentially regulated or tissue-specific cDNA probes and libraries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:6025-6030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dynan, W. S., and S. Yoo. 1998. Interaction of Ku protein and DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit with nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:1551-1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gordenin, D. A., and M. A. Resnick. 1998. Yeast ARMs (DNA at-risk motifs) can reveal sources of genome instability. Mutat. Res. 400:45-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hacker, J., G. Blum Oehler, I. Muhldorfer, and H. Tschape. 1997. Pathogenicity islands of virulent bacteria: structure, function and impact on microbial evolution. Mol. Microbiol. 23:1089-1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill, C. W., and B. W. Harnish. 1981. Inversions between ribosomal RNA genes of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 78:7069-7072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hubank, M., and D. G. Schatz. 1999. cDNA representational difference analysis: a sensitive and flexible method for identification of differentially expressed genes. Methods Enzymol. 303:325-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Itaya, M., and T. Tanaka. 1997. Experimental surgery to create subgenomes of Bacillus subtilis 168. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:5378-5382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kolisnychenko, V., G. Plunkett III, C. D. Herring, T. Feher, J. Posfai, F. R. Blattner, and G. Posfai. 2002. Engineering a reduced Escherichia coli genome. Genome Res. 12:640-647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuzminov, A. 1995. Instability of inhibited replication forks in E. coli. Bioessays 17:733-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuzminov, A. 1999. Recombinational repair of DNA damage in Escherichia coli and bacteriophage lambda. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63:751-813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuzminov, A. 2001. Single-strand interruptions in replicating chromosomes cause double-strand breaks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:8241-8246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ladefoged, S. A., and G. Christiansen. 1992. Physical and genetic mapping of the genomes of five Mycoplasma hominis strains by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Bacteriol. 174:2199-2207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levene, S. D., and K. E. Huffman. 2002. Recombination, p. 227-241. In U. N. Streips and R. E. Yasbin (ed.), Modern microbial genetics. John Wiley & Sons Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 20.Liang, X., X. Q. Pham, M. V. Olson, and S. Lory. 2001. Identification of a genomic island present in the majority of pathogenic isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 183:843-853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu, S. L., and K. E. Sanderson. 1995. Rearrangements in the genome of the bacterium Salmonella typhi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:1018-1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michaux Charachon, S., G. Bourg, E. Jumas Bilak, P. Guigue Talet, A. Allardet Servent, D. O'Callaghan, and M. Ramuz. 1997. Genome structure and phylogeny in the genus Brucella. J. Bacteriol. 179:3244-3249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Michel, B., M. J. Flores, E. Viguera, G. Grompone, M. Seigneur, and V. Bidnenko. 2001. Rescue of arrested replication forks by homologous recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:8181-8188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murray, M. G., and W. F. Thompson. 1980. Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 8:4321-4325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nguyen, H. A., T. Tomita, M. Hirota, J. Kaneko, T. Hayashi, and Y. Kamio. 2001. DNA inversion in the tail fiber gene alters the host range specificity of carotovoricin Er, a phage-tail-like bacteriocin of phytopathogenic Erwinia carotovora subsp. Carotovora Er. J. Bacteriol. 183:6274-6281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paulsen, I. T., R. Seshadri, K. E. Nelson, J. A. Eisen, J. F. Heidelberg, T. D. Read, R. J. Dodson, L. Umayam, L. M. Brinkac, M. J. Beanan, S. C. Daugherty, R. T. Deboy, A. S. Durkin, J. F. Kolonay, R. Madupu, W. C. Nelson, B. Ayodeji, M. Kraul, J. Shetty, J. Malek, S. E. Van Aken, S. Riedmuller, H. Tettelin, S. R. Gill, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, D. L. Hoover, L. E. Lindler, S. M. Halling, S. M. Boyle, and C. M. Fraser. 2002. The Brucella suis genome reveals fundamental similarities between animal and plant pathogens and symbionts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:13148-13153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Radding, C. 2001. Colloquium introduction. Links between recombination and replication: vital roles of recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:8172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Römling, U. 2002. Molecular biology of cellulose production in bacteria. Res. Microbiol. 153:205-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ross P, H. Weinhouse, Y. Aloni, D. Michaeli, P. Weinberger-Ohana, R. Mayer, S Braun, E. de Vroom, G. A. van der Marel, J. H. van Boom, and M. Benziman. 1987. Regulation of cellulose synthesis in Acetobacter xylinum by cyclic diguanylic acid. Nature 325:279-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith, G. R. 1991. Conjugational recombination in E. coli: myths and mechanisms. Cell 64:19-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tal R., H. C. Wong, R. Calhoon, D. Gelfand, A. L. Fear, G. Volman, R. Mayer, P. Ross, D. Amikam, H. Weinhouse, A. Cohen, S. Sapir, P. Ohana, and M. Benziman. 1998. Three cdg operons control cellular turnover of cyclic di-GMP in Acetobacter xylinum: genetic organization and occurrence of conserved domains in isoenzymes. J. Bacteriol. 180:4416-4425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vindenes, H., and R. Bjerknes. 1995. Microbial colonization of large wounds. Burns 21:575-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vizcaino, N., A. Cloeckaert, M. S. Zygmunt, and L. Fernandez Lago. 2001. Characterization of a Brucella species 25-kilobase DNA fragment deleted from Brucella abortus reveals a large gene cluster related to the synthesis of a polysaccharide. Infect. Immun. 69:6738-6748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wallace, R. B., J. Shaffer, R. F. Murphy, J. Bonner, T. Hirose, and K. Itakawa. 1979. Hybridization of synthetic oligodeoxyribonucleotides to phi chi 174 DNA: the effect of single base pair mismatch. Nucleic Acids Res. 6:3543-3557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weller, G. R., B. Kysela, R. Roy, L. M. Tonkin, E. Scanlan, M. Della, S. K. Devine, J. P. Day, A. Wilkinson, F. di Fagagna, K. M. Devine, R. P. Bowater, P. A. Jeggo, S. P. Jackson, and A. J. Doherty. 2002. Identification of a DNA nonhomologous end-joining complex in bacteria. Science 297:1686-1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]