Abstract

Gene expression late during the process of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis is governed by a multistep, signal transduction pathway involving the transcription factor σK, which is derived by regulated proteolysis from the inactive proprotein pro-σK. Processing of pro-σK is triggered by a signaling protein known as SpoIVB, a serine protease that contains a region with similarity to the PDZ family of protein-protein interaction domains. Here we report the discovery of a second PDZ-containing serine protease called CtpB that contributes to the activation of the pro-σK processing pathway. CtpB is a sporulation-specific, carboxyl-terminal processing protease and shares several features with SpoIVB. We propose that CtpB acts to fine-tune the regulation of pro-σK processing, and we discuss possible models by which CtpB influences the σK activation pathway.

Sporulation by the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis is a highly coordinated process, involving multiple pathways of intercellular signaling (for recent reviews, see references 19 and 27). Upon commitment to sporulate, the developing cell (the sporangium) divides asymmetrically to generate compartments of unequal size. The larger compartment is known as the mother cell, and the smaller one is referred to as the forespore (the prospective spore). Initially the mother cell and the forespore lie adjacent to each other, but as sporulation progresses the mother cell engulfs the forespore in a phagocytosis-like process, generating a free protoplast within the mother cell. As a result of engulfment, the forespore is surrounded by two membranes, the inner forespore membrane and the mother-cell membrane that surrounds the forespore, which is known as the outer forespore membrane. Throughout the course of development the forespore and the mother cell communicate with each other to ensure that gene expression in one compartment is coordinated with gene expression in the other. Four sporulation-specific RNA polymerase sigma factors are activated in a spatially and temporally restricted fashion. Shortly after asymmetric division the transcription factor σF is activated selectively in the forespore. The σF factor is then responsible for the activation of σE in the mother cell. At a later stage, σE is required for the activation of σG in the engulfed forespore. Finally, σG sets in motion a chain of events that triggers the activation of σK in the mother cell. While the overall pathway of these intercompartmental signal transduction pathways has been elucidated (at least in the cases of the pathways governing the activation of σE and σK), many of the mechanistic details concerning how σ factor activation is achieved are unknown.

The late-appearing, mother-cell-specific transcription factor σK is synthesized as an inactive precursor protein known as pro-σK, with a 20-residue inhibitory extension at its N terminus (5, 18). A signaling protein (SpoIVB) synthesized in the forespore under the control of σG triggers the proteolytic activation of σK (see Fig. 1B) (4). The pro-σK processing enzyme is likely to be the membrane-embedded metalloprotease SpoIVFB (not to be confused with the similarly named signaling protein SpoIVB), which is synthesized in the mother cell and localizes to the outer forespore membrane. SpoIVFB is held inactive in a multimeric membrane complex by two other proteins that are synthesized in the mother cell, SpoIVFA and BofA. SpoIVFA anchors the pro-σK processing complex in the outer forespore membrane and is thought to serve as a platform for bringing the processing enzyme SpoIVFB into proximity with the inhibitor protein BofA (6, 10, 20, 22, 29-34, 42). Inhibition imposed on SpoIVFB by BofA and SpoIVFA is relieved by the SpoIVB signaling protein, which is believed to be secreted from the forespore into the space between the inner and outer forespore membranes (9, 38).

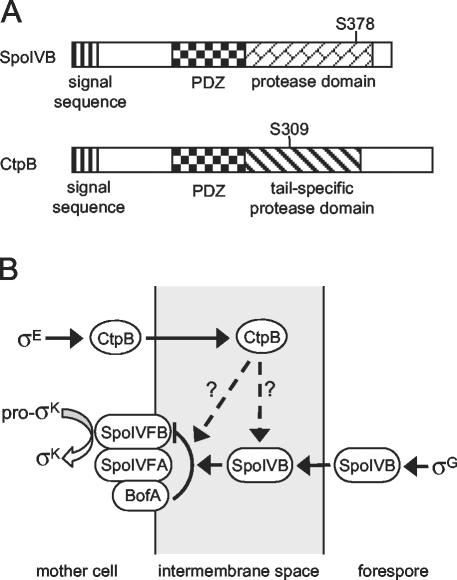

FIG. 1.

(A) Anatomy of SpoIVB and CtpB. Conserved domains are represented by shaded boxes, and the putative catalytic serine residue in each protein is indicated. (B) Model for the regulation of pro-σK processing. The forespore signaling molecule SpoIVB is secreted into the intermembrane space, where it relieves inhibition imposed on the putative pro-σK processing enzyme SpoIVFB by BofA and SpoIVFA. We hypothesize that the mother-cell-synthesized CtpB protein is also secreted into the intermembrane space, where it regulates pro-σK processing. CtpB could act directly on the pro-σK processing complex to enhance the relief of inhibition, or it could affect pro-σK processing indirectly by positively regulating SpoIVB activity. The two possible models are indicated by the dashed arrows. We have previously suggested that integral membrane proteins in the mother cell are not inserted into the engulfing septal membrane. Rather, according to our model, they are inserted into the cytoplasmic membrane and then reach the engulfing membrane by diffusion (34). We do not know whether this would be true for secreted proteins, but for purposes of simplicity we have depicted CtpB as being secreted directly across the engulfing septal membrane.

The SpoIVB signaling protein has three distinct domains (Fig. 1A). Near the extreme N terminus is a hydrophobic sequence that probably facilitates secretion of SpoIVB across the inner forespore membrane (38). The middle region of SpoIVB contains a PDZ domain, a modular protein-protein interaction domain implicated in protein targeting and complex assembly (14, 15). Near its C terminus SpoIVB contains a serine protease domain of the PA(S) clan (13, 28). It has recently been shown that SpoIVB has serine peptidase activity and that the protease activity is necessary for its signaling function in vivo (13). SpoIVB undergoes self-cleavage (and may also be cleaved by additional unidentified proteases) at sites close to its N terminus to produce multiple proteolytic products. Autoproteolysis of SpoIVB may facilitate its release from the inner forespore membrane into the intermembrane space, and it has also been proposed that the signaling-active form is among the cleavage products (38).

Interestingly, the overall domain organization of the SpoIVB signaling molecule is very similar to that of the carboxyl-terminal processing proteases (or tail-specific proteases), which are conserved in many gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria and in chloroplasts and mitochondria from eukaryotes (25, 35, 36). Members of the Ctp protease family contain an N-terminal secretion signal, followed by a PDZ domain and a tail-specific serine protease domain (Fig. 1A) (21). It has been demonstrated that one of the Ctp family members, Escherichia coli Tsp, utilizes its PDZ domain to selectively bind to the nonpolar C termini of its substrates (3).

In this study, we describe a sporulation-specific carboxyl-terminal processing protease in B. subtilis named CtpB. We show that CtpB is synthesized in the mother-cell compartment under the control of σE and probably functions to fine-tune the signal transduction pathway that controls pro-σK processing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General methods.

All B. subtilis strains (Table 1) are derived from the prototrophic strain PY79 (41). The E. coli strain used was DH5α. B. subtilis cells were induced to sporulate by resuspension in Sterlini-Mandelstam medium for β-galactosidase activity assays and immunoblot analysis as described previously (33). Sporulation efficiency was determined by heat resistance (80°C for 20 min) from 27-h cultures sporulated by exhaustion in Difco sporulation medium (12).

TABLE 1.

B. subtilis strains

| Strain | Relevant genotype |

|---|---|

| PY79 | Prototrophic |

| RL813 | amyE::spoIID-lacZ cat |

| RL832 | spoIIIGΔ1 spoIIIG-lacZ cat |

| QPB159 | ΔctpA::tet |

| QPB160 | ΔctpA::tet spoIIIGΔ1 spoIIIG-lacZ cat |

| QPB161 | ΔctpB::tet |

| QPB162 | ΔctpB::tet spoIIIGΔ1 spoIIIG-lacZ cat |

| QPB170 | ΔctpA::cat ΔctpB::tet |

| QPB179 | ΔctpA::tet ΔctpB::erm spoIIIGΔ1 spoIIIG-lacZ cat |

| QPB203 | ΔctpA::cat ΔctpB::tet thrC::cotD-lacZ erm |

| QPB209 | ΔctpA::tet thrC::cotD-lacZ erm |

| QPB210 | ΔctpB::tet thrC::cotD-lacZ erm |

| QPB211 | thrC::cotD-lacZ erm |

| QPB212 | ΔctpA::tet amyE::sspB-lacZ cat |

| QPB213 | ΔctpB::tet amyE::sspB-lacZ cat |

| QPB214 | amyE::sspB-lacZ cat |

| QPB228 | ΔctpA::tet ΔctpB::erm amyE::sspB-lacZ cat |

| QPB613 | ΔbofA::neo thrC::cotD-lacZ erm |

| QPB615 | ΔbofA::neo ΔctpA::cat ΔctpB::tet thrC::cotD-lacZ erm |

| QPB675 | amyE::PctpA-lacZ cat |

| QPB679 | amyE::PctpB-lacZ cat |

| QPB680 | spoIIIGΔ1 amyE::PctpB-lacZ cat |

| QPB682 | spoIIAC::kan amyE::PctpB-lacZ cat |

| QPB683 | spoIIGB::erm amyE::PctpB-lacZ cat |

| QPB749 | ΔctpB::tet amyE::ctpB spec thrC::cotD-lacZ erm |

| QPB750 | ΔctpB::tet amyE::ctpB-S309A spec thrC::cotD-lacZ erm |

| QPB776 | ΔctpA::tet amyE::spoIID-lacZ cat |

| QPB777 | ΔctpB::tet amyE::spoIID-lacZ cat |

| QPB778 | ΔctpA::tet ΔctpB::erm amyE::spoIID-lacZ cat |

Strain and plasmid construction.

To construct ctpA and ctpB transcriptional lacZ fusions, QPO275 (ggcAAGCTTcagcttcgataccaatcagca; uppercase letters indicate the restriction; endonuclease site) and QPO276 (aatcGGATCCtcttcttacattattatcatggacg) were used to amplify the promoter region of ctpA by PCR, and QPO278 (atgGAATTCgtttaaagtggtcggcgtttc) and QPO279 (aatcGGATCCgtatgccagactgtctttacc) were used for the amplification of the promoter region of ctpB. PctpA and PctpB were digested with HindIII/BamHI and EcoRI/BamHI, respectively, and cloned into pDG1661 (11) to generate pQP116 and pQP117. The resulting plasmids were linearized and transformed into PY79 to create QPB675 and QPB679. To construct the ctpB complementation plasmid, ctpB and its promoter region were amplified with QPO278 and QPO376 (atcGGATCCgcacaaagaaacaggagatgaa). The PCR product was digested with EcoRI/BamHI and cloned into pDG1730 (11) to produce pQP169. To construct the S309A missense mutation in ctpB, QPO377 (ggataaaggaagtgccgctgcatcagaaattcttg), QPO378 (caagaatttctgatgcagcggcacttcctttatcc), and pQP169 were used for site-directed mutagenesis (26) to generate pQP169-S309A. pQP169 and pQP169-S309A were linearized and transformed into QPB210 to produce QPB749 and QPB750, respectively. The ctpA and ctpB deletion mutants were created by the long flanking homology PCR method as described previously (26). The sequences of the oligonucleotide primers used to generate the deletions are available upon request.

RESULTS

ctpB encodes a protein homologous to carboxyl-terminal processing proteases.

In the course of our search for the protease responsible for the degradation of the anti-σF factor SpoIIAB (26), we discovered that a deletion mutation in the yvjB gene caused a mild but reproducible reduction in sporulation efficiency (46% ± 6% compared to wild type; also see Table 2). Sequence alignment shows that the yvjB gene encodes a protein of 480 amino acids that shares extensive sequence similarity with members of the carboxyl-terminal processing protease family, including E. coli Tsp (29% identity, 46% similarity) and Synechocystis CtpA (33% identity, 57% similarity) (35, 36). yvjB is one of two genes in B. subtilis predicted to encode a carboxyl-terminal processing protease. One has been described previously and is called ctpA (23). Therefore, we have renamed yvjB as ctpB. B. subtilis CtpA and CtpB share 42% identity and 64% similarity in their amino acid sequences. Interestingly, a ctpA deletion mutant did not affect sporulation significantly (Table 2), suggesting that CtpA and CtpB perform separate functions in B. subtilis.

TABLE 2.

Sporulation efficiencya

| Strain | CFU (108)

|

Sporesd (108) | Sporulation efficiencye (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0b | T24c | |||

| wtf | 7.6 | 6 | 5.6 | |

| ΔctpA | 7.4 | 6.6 | 4.4 | 79 ± 15 |

| ΔctpB | 7.4 | 3.9 | 2.6 | 46 ± 6 |

| ΔctpA ΔctpB | 8 | 3.1 | 2 | 36 ± 6 |

The averages of three independent sporulation assays are shown. Strains used were PY79, QPB159, QPB161, and QPB170. See Table 1 for a description of the strains used in this study.

The number of CFU at 0 h of sporulation (T0).

The number of CFU at 24 h of sporulation (T24). The reduction in CFU of the ΔctpB and ΔctpA ΔctpB mutants is likely due to the lysis of cells that failed to form spores.

Heat-resistant (80°C for 20 min) CFU.

The number of spores compared to the number of wild-type spores.

wt, wild type.

Expression of ctpB depends on the mother-cell-specific σE factor.

To determine whether ctpB is under sporulation control, we monitored the expression of ctpB by using a ctpB-lacZ transcriptional fusion. ctpB was not expressed during vegetative growth (data not shown) but was induced 2 h after the initiation of sporulation, with maximal expression at 3 h (Fig. 2, upper panel). For comparison, we also examined the expression of ctpA with a ctpA-lacZ transcriptional fusion. ctpA was expressed in vegetatively growing cells and appeared to be shut off upon entry into sporulation (Fig. 2, upper panel, and data not shown).

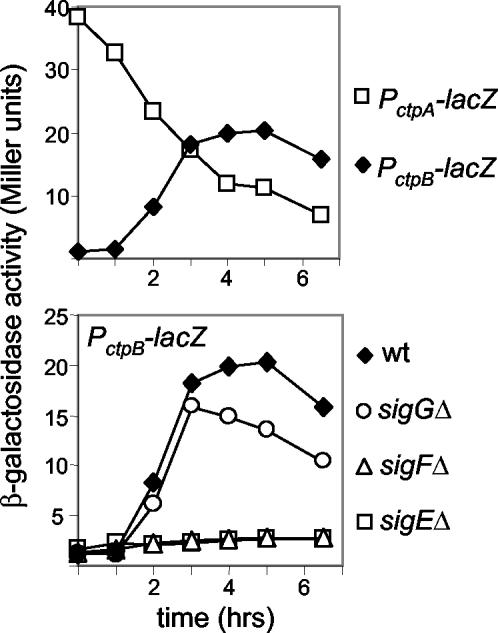

FIG. 2.

Analysis of ctpB expression during sporulation. Cells containing transcriptional lacZ fusions to the promoters of ctpA or ctpB were induced to sporulate, and samples were analyzed for β-galactosidase activity at the indicated times after the initiation of sporulation. Strains used were QPB675 and QPB679 (top panel) and QPB679, QPB680, QPB682, and QPB683 (bottom panel). wt, wild type.

To investigate which sporulation-specific sigma factor was required for ctpB transcription, we examined ctpB-lacZ expression in mutants of different sigma factors. ctpB-lacZ expression required both the early-acting, forespore-specific transcription factor σF and the early-acting, mother-cell-specific factor σE (Fig. 2, lower panel). A mutation in the late-appearing forespore-specific factor σG did not affect ctpB expression. Because σF is required for the activation of σE, these results suggest that ctpB is under σE control in the mother cell and that the effect of the σF mutant is indirect. To investigate whether ctpB is indeed expressed in the mother cell, we visualized ctpB expression by fluorescence microscopy by using a transcriptional fusion of the gene (gfp) for the green fluorescent protein to the promoter of ctpB. The results showed that fluorescence was confined to the mother cell (data not shown). Taken together, these results indicate that ctpB expression is under the control of σE. Consistent with our observations, ctpB was found to be in the σE regulon by DNA microarray analysis (the ratio of ctpB mRNA levels in the presence and absence of σE was ∼2.7) (8). Moreover, an examination of the ctpB promoter region identified a sequence [acatgaa(n)14catatact] which is similar to the consensus promoter sequence recognized by σE [nnatnnn(n)14catannnt] (8).

CtpB is required for efficient activation of the mother-cell transcription factor σK.

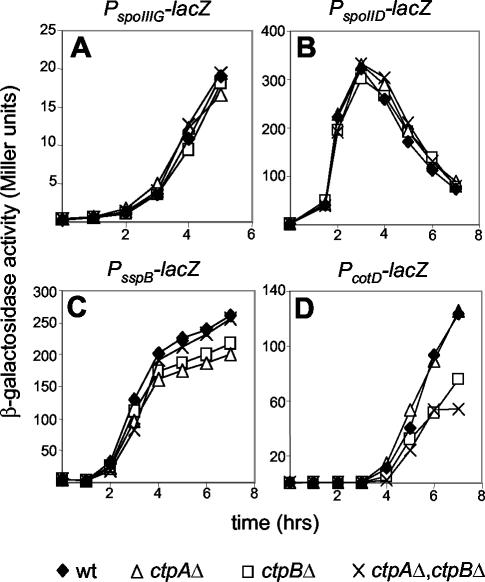

To determine at what stage CtpB activity was influencing sporulation, we examined the activities of the four compartment-specific sigma factors in a ΔctpB mutant. The expression levels of a σF-dependent (spoIIIG), a σE-dependent (spoIID), and a σG-dependent (sspB) promoter fused to lacZ were all unaffected by the ΔctpB mutation (or by ΔctpA or ΔctpA ΔctpB) (Fig. 3A to C). However, the expression of a σK-dependent (cotD) promoter fused to lacZ was delayed by about 1 h in the ΔctpB mutant (Fig. 3D and 4B). Although the onset of cotD-lacZ expression was delayed in the ΔctpB mutant, at later times the transcriptional fusion reached similar expression levels as those observed in the wild type (Fig. 4B). Thus, these results indicate that CtpB is required for efficient activation of the mother-cell transcription factor σK.

FIG. 3.

Compartment-specific sigma factor activity in the absence of CtpB. Cells containing transcriptional lacZ fusions to the indicated promoters were induced to sporulate, and samples were analyzed for β-galactosidase activity at the indicated times after the initiation of sporulation. (A) Strains (RL832, QPB160, QPB162, and QPB179) containing the σF activity reporter PspoIIIG-lacZ. (B) Strains (RL813, QPB776, QPB777, and QPB778) containing the σE activity reporter PspoIID-lacZ. (C) Strains (QPB214, QPB212, QPB213, and QPB228) containing the σG activity reporter PsspB-lacZ. (D) Strains (QPB211, QPB209, QPB210, and QPB203) containing the σK activity reporter PcotD-lacZ. wt, wild type.

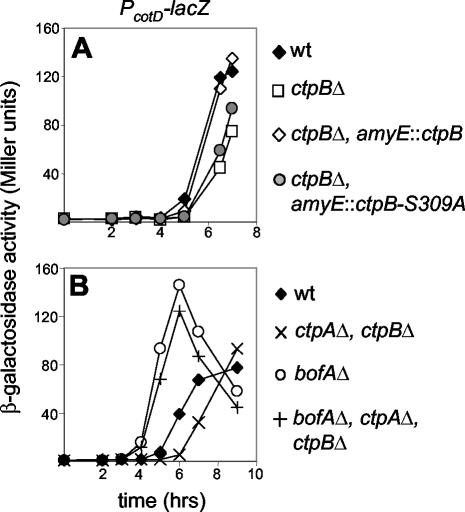

FIG. 4.

Requirement for CtpB in σK activation. Cells containing the σK activity reporter PcotD-lacZ were induced to sporulate, and samples were analyzed for β-galactosidase activity at the indicated times after the initiation of sporulation. (A) The putative catalytic serine residue in CtpB is required for efficient activation of σK. Strains used were QPB211, QPB210, QPB749, and QPB750. (B) The delay in σK activation caused by ΔctpB can be suppressed by a ΔbofA mutant. Strains used were QPB211, QPB203, QPB613, and QPB615. wt, wild type.

The active-site serine is required for the proper function of CtpB.

Carboxyl-terminal processing proteases are members of the SM clan of serine peptidases (28) that exhibit a serine-lysine catalytic dyad (17, 21). Serine 309 of B. subtilis CtpB corresponds to the active-site serine 430 of E. coli Tsp. To test whether serine protease activity is required for CtpB function during sporulation, we generated a ctpB mutant in which the putative catalytic-site serine residue was replaced with an alanine. We introduced either a wild-type ctpB gene or the ctpB-S309A gene into B. subtilis at a nonessential locus in the ΔctpB mutant. The wild-type ctpB gene, but not ctpB-S309A, was able to restore efficient PcotD-lacZ expression and sporulation to the ΔctpB mutant (Fig. 4A and data not shown). These results indicate that the proteolytic activity of CtpB is required for efficient activation of σK during sporulation.

CtpB is required for efficient signaling in the pro-σK processing pathway.

σK activity is controlled at the level of proteolytic cleavage of an inactive precursor (pro-σK). The putative pro-σK processing enzyme SpoIVFB is held inactive by BofA and SpoIVFA until a signal is received from the forespore (33). The forespore signaling protein SpoIVB is predicted to be secreted into the intermembrane space between the mother cell and forespore where it somehow relieves inhibition imposed on SpoIVFB by BofA (38). Since the CtpB mutant delayed the timing of σK activity (Fig. 4B) and the overall organization of the CtpB protein is very similar to that of SpoIVB (Fig. 1A), we hypothesized that CtpB might play a role in this signal transduction pathway. To test this, we analyzed whether a ΔbofA mutant could bypass the delay in σK activity observed in the ΔctpB mutant. Consistent with the idea that CtpB acts in this signaling pathway to promote efficient pro-σK processing, premature σK activity was observed in the ΔctpB mutant when bofA was mutated (Fig. 4B).

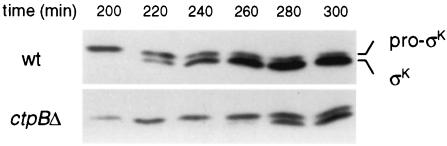

Next we examined pro-σK processing directly in the ΔctpB mutant. Wild-type and ΔctpB cells were induced to sporulate and pro-σK processing was assessed by immunoblot analysis. In wild-type cells, mature σK appeared at 220 min after the start of sporulation, and >80% of pro-σK had been processed by 280 min (Fig. 5). In the ΔctpB mutant, the appearance of mature σK was delayed by about 1 h. These data indicate that the CtpB is required for timely and efficient processing of pro-σK.

FIG. 5.

Pro-σK processing is delayed in a ΔctpB mutant. The figure shows results of immunoblot analysis of unprocessed and mature σK in wild-type (wt; PY79) and ΔctpB (QPB161) sporulating cells at indicated times after the initiation of sporulation.

DISCUSSION

Activation of the mother-cell-specific transcription factor σK is controlled by an intricate signal transduction pathway that operates at the level of proteolytic processing of an inactive precursor protein. The pro-σK processing enzyme is held inactive in a multimeric complex in the outer forespore membrane until a signal is received from the forespore compartment. This signal triggers relief of inhibition imposed on the processing enzyme, resulting in proteolytic activation of σK. In this study, we present evidence that the carboxyl-terminal processing protease CtpB acts in this signaling pathway to fine-tune the timing of σK activation.

The forespore signaling protein SpoIVB probably acts directly on the multimeric membrane complex. However, the mechanism by which it triggers pro-σK processing remains unknown. An attractive model is that, upon secretion into the intermembrane space, SpoIVB binds to BofA or SpoIVFA through its PDZ domain and then utilizes its serine protease domain to cleave one or both of these proteins to relieve the inhibition imposed on the processing enzyme SpoIVFB (13, 14).

The newly discovered CtpB protein shares several intriguing similarities with the SpoIVB signaling protein. They have similar domain structures, are both predicted to be secreted into the intermembrane space, and both regulate pro-σK processing (Fig. 1). Unlike the SpoIVB protein, which is secreted from the forespore chamber and is essential for intercompartmental signaling, CtpB, if it is secreted, comes from the mother-cell compartment and modulates the signaling back to the mother cell. CtpB could act directly on the pro-σK processing complex by enhancing relief of inhibition. For example, CtpB could cleave SpoIVFA or BofA after the SpoIVB signal has been received. Alternatively, CtpB could regulate the pro-σK processing indirectly by enhancing the activity of SpoIVB. SpoIVB exists as multiple proteolytic products derived from autoproteolysis and perhaps cleavage by other proteases. The signaling-active form of SpoIVB has been proposed to be among these cleavage products (38). Consistent with the idea that CtpB might act through SpoIVB by generating one of the signaling-active forms, the appearance of some of the SpoIVB proteolytic products was delayed in a CtpB mutant (data not shown). There is precedent for fine-tuning the pro-σK processing pathway through the regulation of SpoIVB. The forespore protein BofC has been shown to delay σK activation, probably by binding to SpoIVB and inhibiting its activity (37). Our data suggest that CtpB acts in the opposite direction, enhancing σK activation perhaps by facilitating the generation of one or more of the signaling-active forms of SpoIVB.

The pathway controlling pro-σK processing has features in common with the pathway governing the activation of σE of E. coli (not to be confused with the unrelated B. subtilis sigma factor of the same name), a member of the ECF family of sigma factors (24, 40). E. coli σE is a stress-response transcription factor that directs the expression of genes under its control in response to the accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins in the periplasm (7). In unstressed cells, σE is held inactive by an integral membrane protein, the anti-sigma factor RseA, which presumably tethers σE to the cytoplasmic membrane and prevents it from associating with core RNA polymerase. The σE factor is released from the membrane through inactivation of RseA by means of two sequential proteolytic cleavage events (1, 2, 16). The first cleavage occurs in the region of RseA that projects into the periplasm and is mediated by a serine protease, DegS, which senses unfolded periplasmic proteins through its PDZ domain (39). The DegS-mediated cleavage renders RseA susceptible to a second intramembrane cleavage that is mediated by a putative membrane-embedded metalloprotease that is significantly similar to the SpoIVFB protease of the pro-σK processing pathway. Thus, activation of both σE in E. coli and σK in B. subtilis involves PDZ-containing serine proteases (two in the case of σK as we have seen) and related membrane-embedded proteases. Nonetheless, and interestingly, the logic of the two regulatory systems is different. In the case of σE, proteolysis leads to the destruction of an anti-sigma factor, whereas in the case of σK the serine proteases act (presumably) on components of the signal transduction pathway and the membrane-embedded protease activates σK directly by separating it from an inhibitory extension at its N terminus. It will be interesting to compare and contrast both systems as further mechanistic insights emerge into the activation of the stress-response regulatory protein σE and the developmental transcription factor σK.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jonathan Dworkin for drawing our attention to carboxyl-terminal processing proteases and Patrick Eichenberger for helpful discussions on σE regulon and σE-dependent promoters in B. subtilis.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM18568 to R.L.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ades, S. E., L. E. Connolly, B. M. Alba, and C. A. Gross. 1999. The Escherichia coli σE-dependent extracytoplasmic stress response is controlled by the regulated proteolysis of an anti-sigma factor. Genes Dev. 13:2449-2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alba, B. M., J. A. Leeds, C. Onufryk, C. Z. Lu, and C. A. Gross. 2002. DegS and YaeL participate sequentially in the cleavage of RseA to activate the σE-dependent extracytoplasmic stress response. Genes Dev. 16:2156-2168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beebe, K. D., J. Shin, J. Peng, C. Chaudhury, J. Khera, and D. Pei. 2000. Substrate recognition through a PDZ domain in tail-specific protease. Biochemistry 39:3149-3155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cutting, S., A. Driks, R. Schmidt, B. Kunkel, and R. Losick. 1991. Forespore-specific transcription of a gene in the signal transduction pathway that governs pro-σK processing in Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 5:456-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cutting, S., V. Oke, A. Driks, R. Losick, S. Lu, and L. Kroos. 1990. A forespore checkpoint for mother cell gene expression during development in B. subtilis. Cell 62:239-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cutting, S., S. Roels, and R. Losick. 1991. Sporulation operon spoIVF and the characterization of mutations that uncouple mother-cell from forespore gene expression in Bacillus subtilis. J. Mol. Biol. 221:1237-1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dartigalongue, C., D. Missiakas, and S. Raina. 2001. Characterization of the Escherichia coli σE regulon. J. Biol. Chem. 276:20866-20875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eichenberger, P., S. T. Jensen, E. M. Conlon, C. van Ooij, J. Silvaggi, J. E. Gonzalez-Pastor, M. Fujita, S. Ben-Yehuda, P. Stragier, J. S. Liu, and R. Losick. 2003. The σE regulon and the identification of additional sporulation genes in Bacillus subtilis. J. Mol. Biol. 327:945-972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gomez, M., S. Cutting, and P. Stragier. 1995. Transcription of spoIVB is the only role of σG that is essential for pro-σK processing during spore formation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 177:4825-4827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green, D. H., and S. M. Cutting. 2000. Membrane topology of the Bacillus subtilis pro-σK processing complex. J. Bacteriol. 182:278-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guerout-Fleury, A. M., K. Shazand, N. Frandsen, and P. Stragier. 1995. Antibiotic-resistance cassettes for Bacillus subtilis. Gene 167:335-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harwood, C. R., and S. M. Cutting. 1990. Molecular biology methods for Bacillus. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 13.Hoa, N. T., J. A. Brannigan, and S. M. Cutting. 2002. The Bacillus subtilis signaling protein SpoIVB defines a new family of serine peptidases. J. Bacteriol. 184:191-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoa, N. T., J. A. Brannigan, and S. M. Cutting. 2001. The PDZ domain of the SpoIVB serine peptidase facilitates multiple functions. J. Bacteriol. 183:4364-4373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hung, A. Y., and M. Sheng. 2002. PDZ domains: structural modules for protein complex assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 277:5699-5702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanehara, K., K. Ito, and Y. Akiyama. 2002. YaeL (EcfE) activates the σE pathway of stress response through a site-2 cleavage of anti-sigma(E), RseA. Genes Dev. 16:2147-2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keiler, K. C., and R. T. Sauer. 1995. Identification of active site residues of the Tsp protease. J. Biol. Chem. 270:28864-28868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroos, L., B. Kunkel, and R. Losick. 1989. Switch protein alters specificity of RNA polymerase containing a compartment-specific sigma factor. Science 243:526-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kroos, L., and Y. T. Yu. 2000. Regulation of sigma factor activity during Bacillus subtilis development. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3:553-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kroos, L., Y. T. Yu, D. Mills, and S. Ferguson-Miller. 2002. Forespore signaling is necessary for pro-σK processing during Bacillus subtilis sporulation despite the loss of SpoIVFA upon translational arrest. J. Bacteriol. 184:5393-5401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liao, D. I., J. Qian, D. A. Chisholm, D. B. Jordan, and B. A. Diner. 2000. Crystal structures of the photosystem II D1 C-terminal processing protease. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7:749-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu, S., S. Cutting, and L. Kroos. 1995. Sporulation protein SpoIVFB from Bacillus subtilis enhances processing of the sigma factor precursor pro-σK in the absence of other sporulation gene products. J. Bacteriol. 177:1082-1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marasco, R., M. Varcamonti, E. Ricca, and M. Sacco. 1996. A new Bacillus subtilis gene with homology to Escherichia coli prc. Gene 183:149-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Missiakas, D., M. P. Mayer, M. Lemaire, C. Georgopoulos, and S. Raina. 1997. Modulation of the Escherichia coli σE (RpoE) heat-shock transcription-factor activity by the RseA, RseB and RseC proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 24:355-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oelmuller, R., R. G. Herrmann, and H. B. Pakrasi. 1996. Molecular studies of CtpA, the carboxyl-terminal processing protease for the D1 protein of the photosystem II reaction center in higher plants. J. Biol. Chem. 271:21848-21852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pan, Q., D. A. Garsin, and R. Losick. 2001. Self-reinforcing activation of a cell-specific transcription factor by proteolysis of an anti-sigma factor in B. subtilis. Mol. Cell 8:873-883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piggot, P. J., and R. Losick. 2002. Sporulation genes and intercompartmental regulation, p. 483-518. In A. L. Sonenshein, J. A. Hoch, and R. Losick (ed.), Bacillus subtilis and its closest relatives: from genes to cells. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 28.Rawlings, N. D., E. O'Brien, and A. J. Barrett. 2002. MEROPS: the protease database. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:343-346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Resnekov, O., S. Alper, and R. Losick. 1996. Subcellular localization of proteins governing the proteolytic activation of a developmental transcription factor in Bacillus subtilis. Genes Cells 1:529-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Resnekov, O., and R. Losick. 1998. Negative regulation of the proteolytic activation of a developmental transcription factor in Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3162-3167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ricca, E., S. Cutting, and R. Losick. 1992. Characterization of bofA, a gene involved in intercompartmental regulation of pro-σK processing during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 174:3177-3184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rudner, D. Z., P. Fawcett, and R. Losick. 1999. A family of membrane-embedded metalloproteases involved in regulated proteolysis of membrane-associated transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:14765-14770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rudner, D. Z., and R. Losick. 2002. A sporulation membrane protein tethers the pro-σK processing enzyme to its inhibitor and dictates its subcellular localization. Genes Dev. 16:1007-1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rudner, D. Z., Q. Pan, and R. M. Losick. 2002. Evidence that subcellular localization of a bacterial membrane protein is achieved by diffusion and capture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:8701-8706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shestakov, S. V., P. R. Anbudurai, G. E. Stanbekova, A. Gadzhiev, L. K. Lind, and H. B. Pakrasi. 1994. Molecular cloning and characterization of the ctpA gene encoding a carboxyl-terminal processing protease. Analysis of a spontaneous photosystem II-deficient mutant strain of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. J. Biol. Chem. 269:19354-19359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silber, K. R., K. C. Keiler, and R. T. Sauer. 1992. Tsp: a tail-specific protease that selectively degrades proteins with nonpolar C termini. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:295-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wakeley, P., N. T. Hoa, and S. Cutting. 2000. BofC negatively regulates SpoIVB-mediated signalling in the Bacillus subtilis σK-checkpoint. Mol. Microbiol. 36:1415-1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wakeley, P. R., R. Dorazi, N. T. Hoa, J. R. Bowyer, and S. M. Cutting. 2000. Proteolysis of SpoIVB is a critical determinant in signalling of pro-σK processing in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 36:1336-1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walsh, N. P., B. M. Alba, B. Bose, C. A. Gross, and R. T. Sauer. 2003. OMP peptide signals initiate the envelope-stress response by activating DegS protease via relief of inhibition mediated by its PDZ domain. Cell 113:61-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Young, J. C., and F. U. Hartl. 2003. A stress sensor for the bacterial periplasm. Cell 113:1-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Youngman, P. J., J. B. Perkins, and R. Losick. 1983. Genetic transposition and insertional mutagenesis in Bacillus subtilis with Streptococcus faecalis transposon Tn917. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 80:2305-2309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu, Y. T., and L. Kroos. 2000. Evidence that SpoIVFB is a novel type of membrane metalloprotease governing intercompartmental communication during Bacillus subtilis sporulation. J. Bacteriol. 182:3305-3309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]