Abstract

rRNA synthesis is the rate-limiting step in ribosome synthesis in Escherichia coli. Its regulation has been described in terms of a negative-feedback control loop in which rRNA promoter activity responds to the amount of translation. The feedback nature of this control system was demonstrated previously by artificially changing ribosome synthesis rates and observing responses of rRNA promoters. However, it has not been demonstrated previously that the initiating nucleoside triphosphate (iNTP) and guanosine 5′-diphosphate 3′-diphosphate (ppGpp), the molecular effectors responsible for controlling rRNA promoters in response to changes in the nutritional environment, are responsible for altering rRNA promoter activities under these feedback conditions. Here, we show that most feedback situations result in changes in the concentrations of both the iNTP and ppGpp and that the directions of these changes are consistent with a role for these two small-molecule regulators in feedback control of rRNA synthesis. In contrast, we observed no change in the level of DNA supercoiling under the feedback conditions examined.

In all cells examined, from prokaryotes to humans, expression of the products that make up the translation apparatus (rRNA, tRNA, ribosomal proteins, and associated factors) is tightly regulated. In Escherichia coli, several potentially overlapping regulatory systems have been identified as contributors to the control of rRNA and tRNA expression. Together, these regulatory systems match the protein synthetic potential to the demand for protein synthesis, no matter how the demand is altered (e.g., by nutritional shifts or starvations, by changes in growth phase, or by inhibitors of translation). Dissecting the roles of individual regulatory factors in this complex network has long posed a major experimental challenge (17, 25, 37).

E. coli has seven rRNA operons (rrn), each of which contains two promoters, rrn P1 and rrn P2. During moderate to rapid growth, the rrn P1 promoters provide the majority of rRNA transcription in the cell. Sequences upstream of the −35 hexamer of rrn P1 promoters account for much of the strength of these promoters.

Fis (factor for inversion stimulation) was originally identified for its role in site-specific inversion (23); however, it was shown subsequently to participate in other cellular processes as well, including activation of rrn P1 promoters (34). Each of the seven rrn P1 promoters has binding sites for Fis upstream of the core promoter element (three to five sites, depending on the operon), and activation by Fis increases promoter activity four- to eightfold (19). Between the Fis sites and the −35 hexamer of the core promoter is an A+T-rich sequence called the UP element. The C-terminal domain of the alpha subunit (αCTD) of RNA polymerase binds specifically to the UP element (33), increasing rrn P1 promoter activity 20- to 50-fold, depending on the operon (19). While these upstream promoter elements are essential for the strength of rrn P1 promoters, promoter constructs that lack the binding sites for Fis and αCTD (core promoters; −41 to + 1 with respect to the transcription start site) retain their characteristic regulatory properties (6, 24).

At least two small molecules regulate rrn P1 core promoter activity. Guanosine 5′-diphosphate 3′-diphosphate (ppGpp) was originally identified in cells that were starved for amino acids (7, 8), and subsequent experiments have shown that ppGpp also regulates rRNA transcription under other growth conditions (e.g., nutrient shifts, entry into stationary phase, response to translation inhibitors) (26, 30, 36). ppGpp is a direct negative regulator that decreases the half-life of the open complexes formed at all promoters (3). Since this kinetic step is rate limiting for transcription initiation at rrn P1 promoters, changes in ppGpp concentration affect rRNA expression.

In addition to being regulated by ppGpp, rrn P1 promoters are controlled by changes in the concentration of their initiating nucleoside triphosphate (iNTP). In vitro, rrn P1 promoters require unusually high concentrations of their respective iNTP for maximal transcription (4, 13, 36). In vivo, changes in iNTP concentrations directly control rrn P1 activity during progression through stationary phase, outgrowth from stationary phase, when translation is inhibited, and when the iNTP concentration is altered by mutations in NTP synthesis pathways (30, 36). As with ppGpp, direct effects of iNTP concentration on transcription initiation are limited to promoters that make short-lived open complexes. Thus, the unusual intrinsic kinetic characteristics of rrn P1 promoters result in their specific control by changes in the concentrations of small molecules (2, 3).

In bacteria, operons that are not being translated actively are normally subject to premature transcriptional termination. In addition to being subject to the mechanisms described above, the long, untranslated rRNA operons escape these polarity effects as a result of an antitermination system (10). This antitermination system uses host factors originally identified for their roles as N-utilization substances in λ phage antitermination (Nus factors) (9, 39, 42).

Artificial manipulation of ribosome synthesis rates was used previously to demonstrate that a feedback mechanism(s) plays a role in the control of rRNA transcription. For example, when the rRNA gene dose was increased (21) or decreased (9, 43), when rRNA was overexpressed from inducible promoters (18), when the fis gene was deleted or the rpoA gene was mutated (4, 33, 34), or when the rRNA antitermination system was disrupted (39), corresponding changes in rRNA core promoter activities always restored overall rRNA synthesis rates—and therefore ribosome synthesis rates—to the level appropriate for the nutrient condition. Thus, feedback mechanisms balance rRNA promoter activities with the need for protein synthesis.

While it was demonstrated previously that changes in the concentrations of iNTPs and ppGpp control transcription from rrn P1 promoters in response to changes in nutritional conditions (30), it has not been demonstrated that the concentrations of these same molecules change under the conditions described above that were used previously to show that rRNA synthesis is feedback regulated. We show here that in all but one of these conditions, both the ppGpp and iNTP concentrations change, and in the remaining situation, the iNTP concentration alone changes. In all cases, changes in iNTP and ppGpp concentrations are in the direction consistent with a role for these small molecules in feedback regulation of rRNA expression. Thus, the results suggest that both ppGpp and iNTP concentrations serve as feedback regulators, linking protein synthesis and rrn P1 promoter activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

Promoter-lacZ fusions were constructed in strain VH1000 (MG1655 lacZ lacI pyrE+ [13]). Promoter fragments were generated by PCR using oligonucleotides containing EcoRI sites upstream and HindIII sites downstream of the promoter sequence. Restriction fragments were then fused to lacZ on plasmids and recombined into bacteriophage λ, and the phage was lysogenized in single copy at the λ attachment site (λ system II) (32, 40). Strains and plasmids are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids

| Name | Genotype and promoter endpoints in lacZ fusion | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| RLG4755 | VH1000/λ rrn P1 −41 to +50 | This work |

| RLG4998 | VH1000/λ lacUV5 −59 to +36 | 3 |

| RLG6228 | VH1000/λ rrn P1(dis) −41 to +50 | This work |

| RLG6241 | VH1000 nusB5/λ rrn P1 −41 to +50 | This work |

| RLG6243 | VH1000 nusB5/λ lacUV5 −59 to +36 | This work |

| RLG6245 | VH1000 nusB5/λ rrn P1(dis) −41 to +50 | This work |

| RLG6247 | VH1000 Δfis/λ rrn P1 −41 to +50 | This work |

| RLG6249 | VH1000 Δfis/λ lacUV5 −59 to +36 | This work |

| RLG6251 | VH1000 Δfis/λ rrn P1(dis) −41 to +50 | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pRLG770 | pBR322 derivative | 34 |

| pHTf1-αwt | 2- to 3-fold overexpression of wild-type rpoA | 15 |

| pHTf1-αR265A | 2- to 3-fold overexpression of R265A rpoA | 15 |

| pNO1301 | pBR322 containing intact rrn operon | 21 |

| pNO1302 | pBR322 containing disrupted rrn operon | 21 |

Mutations were introduced into lysogens by standard methods. The Δfis insertion-deletion (fis-767) (22) was introduced by P1 transduction (29) with selection for kanamycin resistance. The nusB5 allele was introduced by P1 transduction with selection for tetracycline resistance from a linked Tn10 (12, 39). Tetr colonies were screened for slow growth at 25°C (nus mutants are cold sensitive) (41). pHTf1α derivatives expressing either wild-type rpoA or rpoA-R265A were introduced by transformation (15). The rrn gene dose was increased by introduction of a multicopy plasmid containing a copy of the rrnB operon (plasmid pNO1301). Effects of increased gene dose on expression from promoter-lacZ fusions were quantified by comparison with expression from the same fusion in a strain containing a control plasmid, pNO1302, that codes for nonfunctional 16S and 23S rRNAs (pNO1302 carries rRNA genes containing large deletions) (21). Strains were grown at 37°C with aeration in the media as indicated in the figure legends. At least two fresh independent transductants or transformants were used for each experiment to reduce the chance of selecting for suppressor mutants.

NTP and ppGpp measurements.

Cultures were grown in media described in the figure legends to mid-log phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of ∼0.3). Promoter activities (see below) and nucleotide concentrations were determined from identical cultures, except that the cultures used for NTP measurements contained 20 μCi of KH232PO4/ml (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences). ATP and ppGpp were measured by thin-layer chromatography following formic acid extraction (20). Reported values represent the averages of extracts from at least three different cultures.

Promoter activity in vivo.

λ monolysogens containing promoter-lacZ fusions were grown in the media described in the figure legends for three to four generations to an OD600 of ∼0.3. Cultures were placed on ice for >30 min and lysed by sonication, and β-galactosidase activity was measured (5). In order to focus on the transcription initiation-specific effects of the following feedback situations, we express the rrnB P1-specific effect as the ratio of the observed change in rrnB P1 activity divided by the observed change in the activity of the unregulated control promoter, rrnB P1(dis) (see Fig. 1 and Results). The rrnB P1 and rrnB P1(dis) promoter constructs lacked binding sites for Fis in order to eliminate confounding effects from potential changes in Fis concentration. Reported values are the averages of two separate assays from each of at least two independent cultures.

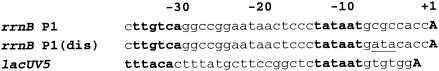

FIG. 1.

Sequences of core promoters used in this study. −10 and −35 hexamer sequences are in bold. The +1 NTP is in bold capital letters. Sequence endpoints of DNA fragments used to construct promoter-lacZ fusions are indicated in Table 1. The rrnB P1(dis) promoter (24) is identical to rrnB P1 except for a 3-bp substitution (underlined) that causes the promoter to form a longer-lived open complex, resulting in a loss of regulation (3). This promoter makes the same transcript as rrnB P1.

Measurement of plasmid supercoiling.

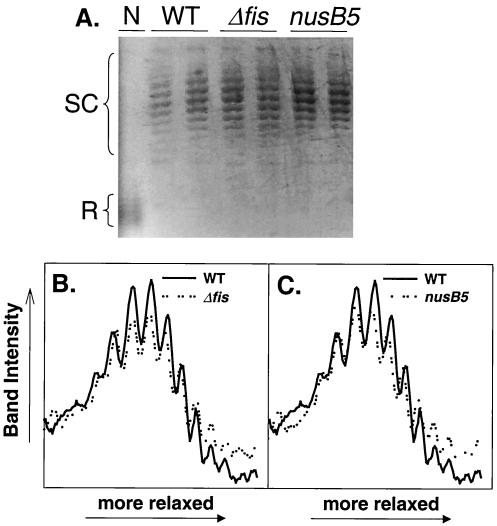

λ monolysogens were transformed with a pBR322 derivative, pRLG770 (34). Wild-type, nusB5, and Δfis cultures were grown as described in the figure legends for Fig. 2 and 4A, with the addition of ampicillin (100 μg/ml). At an OD600 of ∼0.5, plasmids were extracted using a Qiaprep spin miniprep kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.). Approximately 400 ng of plasmid DNA was loaded onto a 1% agarose 1× Tris-boric acid-EDTA-buffered gel containing 25 μg of chloroquine/ml (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.), and electrophoresis was at 30 V for 20 h in 1× Tris-boric acid-EDTA containing 25 μg of chloroquine/ml. Under these conditions, supercoiled plasmids migrate slower than relaxed plasmids (11). The locations of supercoiled and relaxed plasmids were confirmed by comparison with plasmids extracted from cells treated with (10 μg/ml for 30 min) and without the gyrase inhibitor norfloxacin (Sigma Chemical Co.) (27). Gels were washed three times for 10 min each time in distilled water to remove chloroquine, stained in 5 μg of ethidium bromide/ml, and visualized using UV light. Fresh transformants of independent transductants were used in each experiment.

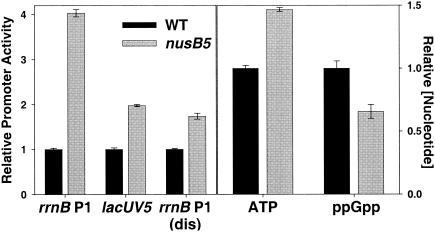

FIG. 2.

Feedback derepression in a nusB5 strain. Promoter activities in wild-type and nusB5 strains were measured from single-copy promoter-lacZ fusions using β-galactosidase assays. Promoter activities are expressed relative to the average activity measured in a wild-type strain. Absolute promoter activities in the wild-type strain were as follows: rrnB P1, 96 Miller units (MU); lacUV5, 1,519 MU; rrnB P1(dis), 1,295 MU. Strains were grown at 37°C in morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS) minimal medium supplemented with 0.4% glucose, 10 μg of thiamine/ml, and 1 mM KH2PO4. ATP and ppGpp were extracted from identical cultures grown in the presence of 20 μCi of KH232PO4/ml. Nucleotide concentrations are expressed relative to the concentration in the wild-type strain. Error between measurements from independent cultures is indicated. The growth rates of the wild-type and mutant strains were 1.20 and 0.73 doublings/hour, respectively.

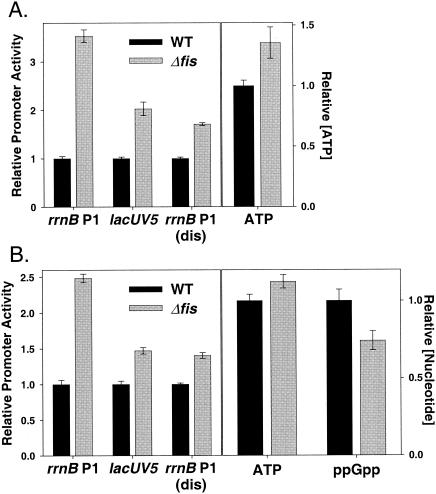

FIG. 4.

Feedback derepression in a Δfis strain. (A) Promoter activities and ATP and ppGpp concentrations in wild-type and Δfis strains grown in MOPS medium supplemented with 0.4% glucose, 20 amino acids (80 μg/ml), 10 μg of thiamine/ml, and 1 mM KH2PO4 were measured as described in the legends for Fig. 2 and 3. (B) Cultures were grown as described in the legend for panel A but in the absence of amino acids. The growth rates of the wild-type and mutant strains were 1.71 and 1.58 doublings/hour, respectively, in panel A and 1.15 and 0.98 doublings/hour, respectively, in panel B.

RESULTS

Rationale.

Homeostatic control systems function by continually monitoring specific signals and making corresponding small regulatory adjustments. Since these small fluctuations are too subtle to detect under normal steady-state growth conditions, larger perturbations to the system must be introduced in order to identify the regulatory mechanisms that participate in the control circuit. Previous studies demonstrated that disturbances in rRNA expression induce feedback control mechanisms that restore normal ribosome synthesis by altering rrn P1 core promoter activities (16, 18, 21, 33, 34, 39). However, the molecular signals responsible for this feedback have remained unclear.

We examined four situations that were shown previously to alter rrn P1 core promoter activity (feedback conditions), presumably because they generated an imbalance between ribosome synthesis and the demand for protein synthesis. Three of these feedback conditions were caused by mutations in genes coding for factors involved in rRNA synthesis, nusB (39), rpoA, (33), or fis (3, 34). The fourth condition was caused by an increase in the rrn gene dose (21). We measured changes in the concentrations of ppGpp and iNTPs, the small molecules known to regulate rrn P1 core promoter activities in response to changes in the nutritional environment, during each of the situations that induced feedback.

The effects of each of these situations on promoter activity were detected using promoter-lacZ fusions as reporters (see Materials and Methods). We used three promoter constructs: rrnB P1, a well-characterized representative of the rrn P1 promoters, and two control promoters, rrnB P1(dis) and lacUV5 (Fig. 1). The control promoters are relatively insensitive to changes in ppGpp and iNTP concentrations in vivo and in vitro, because they make long-lived open complexes (3).

Feedback control of rrn P1 promoters in a nusB5 strain.

Since rRNA transcripts are not translated, they would be subject to premature termination of transcription (polarity) if it were not for an antitermination system (see above). We observed fourfold more rrnB P1 promoter activity in a strain where rRNA antitermination was partially disrupted (nusB5) than in a wild-type strain (Fig. 2), whereas the activities of the two control promoters increased only ∼twofold. Correlating with the twofold specific effect on rrnB P1 transcription initiation, there was a 45% increase in ATP concentration and a 40% decrease in ppGpp concentration (Fig. 2) (see also reference 39). These data are consistent with the model that increases in the iNTP concentration and decreases in the ppGpp concentration contribute to feedback derepression of rrn P1 promoters when rRNA transcription elongation is disrupted.

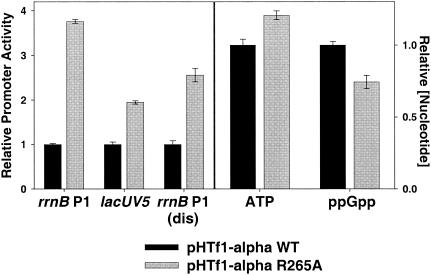

Feedback control of rrn P1 promoters in strains expressing variants of αCTD.

Previous work showed that when UP element function was disrupted by overexpression of α variants defective in DNA binding, core rrnB P1 promoter activity increased (33). Overexpression of a DNA binding-defective α subunit (R265A) resulted in a 3.8-fold increase in rrnB P1 activity (Fig. 3), while the activities of the lacUV5 and rrnB P1(dis) promoters increased only 2 and 2.5-fold, respectively, yielding an rrnB P1-specific increase of ∼1.5-fold. A 20% increase in ATP concentration and a 25% decrease in ppGpp concentration accompanied this increase in rrnB P1 transcription initiation. These data are consistent with the model that changes in both iNTPs and ppGpp concentrations contribute to feedback control of rRNA expression induced by defects in UP element function.

FIG. 3.

Feedback derepression in a strain overexpressing rpoA-R265A. Promoter activities in strains overexpressing rpoA-R265A (from pHTf1-αR265A) were compared to activities in strains overexpressing wild-type α (pHTf1-αWT) using promoter-lacZ fusions described in Fig. 1 and 2. Promoter activity is expressed relative to the average activity measured in strains overexpressing wild-type α. Promoter activities in strains overexpressing wild-type α were as follows: rrnB P1, 60 MU; lacUV5, 808 MU; and rrnB P1(dis), 762 MU. Strains were grown as described in the legend to Fig. 2, with the addition of 100 μg of ampicillin/ml. ATP and ppGpp concentrations were measured as described in the legend for Fig. 2. Nucleotide concentrations are expressed relative to the concentration in the strain overexpressing wild-type α. The growth rates of the strains expressing the wild-type and mutant α were 0.84 and 0.65 doublings/hour, respectively.

Feedback control of rrn P1 promoters in a Δfis strain.

The Fis protein binds to sites upstream of rrn P1 promoters and activates transcription four- to eightfold when cells are growing logarithmically at moderate to high growth rates (19, 34). When the fis gene is deleted, full-length rrn P1 promoters lose this activation, and feedback derepression of core rrn P1 promoters restores rRNA synthesis to normal levels (3, 34).

At a high growth rate (∼1.7 doublings per hour), when Fis makes a relatively large contribution to rrn P1 promoter activity, we observed 3.5-fold more core rrnB P1 activity in the Δfis strain than in the wild-type strain (Fig. 4A), whereas the control promoters, lacUV5 and rrnB P1(dis), increased only 2 and 1.7-fold, respectively. This approximately twofold rrnB P1-specific feedback derepression in the Δfis strain was accompanied by a 35% increase in the cellular ATP concentration (Fig. 4A).

Since the ppGpp concentration was not measurable with confidence under these high growth rates using our detection methods, we also measured the effects of the Δfis mutation on rrnB P1 activity in cells grown at a lower growth rate (in minimal medium supplemented with glucose but not amino acids), a situation where the ppGpp concentration was higher. Fis concentrations are lower at this more modest growth rate (∼1 generation per hour), reducing the occupancy of Fis sites and thus the effect of Fis on rrn P1 promoter activity (1). Deletion of the fis gene increased rrnB P1 activity 2.5-fold under these conditions, whereas the control promoters increased only 50% (Fig. 4B). This ∼1.6-fold rrnB P1-specific derepression was accompanied by a small but reproducible increase in ATP concentration (∼12%) and a small but reproducible decrease in the ppGpp concentration (∼25%) (Fig. 4B). These data are consistent with the conclusion that changes in the concentrations of both iNTPs and ppGpp contribute to the restoration of rrn P1 promoter activity in a Δfis strain.

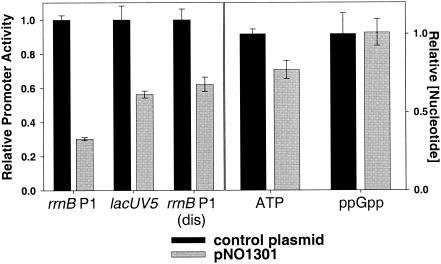

Feedback control of rrn P1 promoters in strains with altered rrn gene dose.

Previous studies have shown that feedback mechanisms decrease rrn P1 promoter activity when cells are transformed with multicopy plasmids encoding rRNA operons, keeping overall rRNA synthesis rates constant independent of the rRNA gene dose. We observed a 3.3-fold decrease in rrnB P1 core promoter activity in the presence of extra intact rrn operons (Fig. 5), consistent with results from previous studies (21). In contrast, lacUV5 and rrnB P1(dis) activity decreased by only 1.8- and 1.6-fold, respectively. Thus, there was an approximately twofold rrnB P1-specific feedback response to the increase in rRNA gene dose. We observed a small but reproducible decrease in ATP concentration (20%) in response to the increased rrn gene dose, but we did not observe an increase in the ppGpp concentration (Fig. 5). Although it is likely that the changes in the iNTP concentration contribute to the decrease in rrnB P1 promoter activity, this is probably insufficient to account for the entire effect on transcription initiation. Thus, it is possible that all means of inducing feedback control do not utilize the identical set of regulatory mechanisms (see also references 9 and 43 and Discussion, below).

FIG. 5.

Feedback derepression in a strain with increased rrn gene dose. By using β-galactosidase assays, promoter activities (from single-copy promoter-lacZ fusions) in strains carrying extra rRNA operons (plasmid pNO1301) (21) were compared to activities in strains containing a control plasmid (pNO1302) that does not make functional 16S or 23S rRNAs (21). Promoter activity is expressed relative to the average activity measured in strains containing the control plasmid. Growth and ATP and ppGpp extraction were performed as described in the legend for Fig. 3. Nucleotide concentrations are expressed relative to the concentration in the strain containing the control plasmid. Promoter activities in strains containing the control plasmid were as follows: rrnB P1, 137 MU; lacUV5, 1,789 MU; and rrnB P1(dis), 1,469 MU. The growth rate of the strain containing pNO1301 was 0.86 doublings/hour, and that of the strain containing pNO1302 was 1.11 doublings/hour.

Changes in DNA supercoiling are not responsible for feedback control of rrn P1 promoters in Δfis or nusB5 strains.

In the figures above, we correlated changes in the concentrations of two regulators of rrn P1 core promoters, iNTPs and ppGpp, with changes in the activity of rrnB P1 in a variety of experimental situations, suggesting that these regulatory factors contribute to feedback control of rRNA expression. However, we cannot rule out that other mechanisms also make contributions to either the rrn P1-specific or the general effects on transcription observed in these situations. For example, changes in DNA supercoiling could theoretically contribute to the observed changes in promoter activity in the feedback situations discussed above, since the activities of many promoters (including rrn P1 promoters) increase with increases in negative supercoiling (44). To determine if the level of DNA supercoiling is different in Δfis and nusB5 strains compared to wild-type strains, we extracted plasmids from these strains during log phase and examined their mobilities on chloroquine gels. Cells were grown in minimal glucose medium (Fig. 6A) and in minimal glucose medium supplemented with amino acids (data not shown). We observed no significant difference in the degree of plasmid supercoiling between the Δfis mutant and the wild-type strain or between the nusB5 and the wild-type strain (Fig. 6B and C). We conclude that changes in supercoiling do not contribute significantly to the observed increases in rrn P1 promoter activities observed in these feedback situations (assuming that plasmid topology is reflective of the chromosomal topology near the rRNA operons). Our result with the Δfis strain conflicts with that reported by another group who concluded that supercoiling levels increased in a Δfis strain relative to a wild-type strain (38) (see Discussion).

FIG. 6.

Plasmid topology is not affected by the Δfis or nusB5 mutations. (A) pBR322-derivative pRLG770 (34) was extracted from wild-type (WT), Δfis, and nusB5 strains grown as described in the legend for Fig. 3. The samples in the two lanes shown for each strain derived from duplicate cultures. The DNA in lane N was isolated from a wild-type strain treated with the gyrase inhibitor norfloxacin (10 μg/ml for 30 min) prior to plasmid extraction and electrophoresis on chloroquine gels (see Materials and Methods). In these gels, more relaxed plasmids (R) migrate faster than supercoiled plasmids (SC), as reported previously (11). Topoisomers were quantified using ImageQuant 5.1 (Molecular Dynamics). Representative traces comparing plasmid DNA from Δfis versus wild-type strains (B) and nusB5 versus wild-type strains (C) are shown.

DISCUSSION

Changes in iNTP and ppGpp concentrations contribute to feedback control of rRNA synthesis.

We propose that changes in the concentrations of two small-molecule effectors, iNTPs and ppGpp, contribute to compensatory increases in the activities of rrn P1 promoters following treatments that would be expected to decrease rRNA output. In nusB5, rpoA-R265A, and Δfis mutant strains, ATP concentrations increased and ppGpp concentrations decreased relative to the wild-type strain, apparently compensating (at least in part) for the decrease that would have been expected otherwise in the rRNA synthesis rate. We note that the degree of compensation in the mutant strains was not always sufficient to restore the level of promoter activity that would have been expected at the growth rate of the wild-type strain. In some cases, growth was significantly slower than in the wild-type strain (see figure legends). It is well established that rRNA core promoter activity correlates with cell growth rate (growth rate-dependent regulation) (6, 17), and in no case did a mutant strain grow faster than the wild-type strain (see figure legends). Therefore, the observed increases in rrnB P1 core promoter activity in the mutant strains cannot be attributed to an increase in growth rate.

A role for iNTPs and ppGpp under feedback conditions is consistent with the previous conclusion that the increase in rrn P1 promoter activity following inhibition of translation (from spectinomycin or chloramphenicol treatment) results from an increase in ATP concentration and a decrease in ppGpp concentration (36). Furthermore, the level of feedback derepression by variant rrnB P1 promoters in Δfis strains correlated with the promoters' iNTP requirements in vitro (4). Taken together, these data suggest that both ppGpp and iNTP concentrations play roles in feedback control of rRNA transcription.

We have always observed that the activities of control promoters (as measured by promoter-lacZ fusions) change in parallel with rrnB P1, but to a lesser extent, under feedback conditions. Thus, the specific effect on rRNA transcription is superimposed on a more general effect on gene expression in these situations. Either the changes in iNTP and ppGpp concentrations have a smaller effect on the activities of these promoters that is superimposed on the specific effects on rRNA and rRNA-like promoters or feedback directly or indirectly introduces a general effect on some other step in reporter gene expression (e.g., transcription elongation, mRNA decay, or translation). We emphasize that rrnB P1 and rrnB P1(dis) make exactly the same transcript (Fig. 1), indicating that the specific effect of feedback conditions on reporter gene expression is on transcription initiation, not some later step in gene expression. These results are consistent with the model that the kinetic step in reporter gene expression responsible for the specific effect of feedback conditions on these promoters is open complex lifetime, the step affected by the concentration of the iNTP and ppGpp.

Additional factors might contribute to feedback control of rRNA synthesis.

When feedback inhibition of rrn P1 core promoter activity was induced by increasing the rrn gene dose, ATP concentration decreased, but ppGpp concentration stayed the same. It was also reported previously that depletion of rRNA operons resulted in an increase in rrn expression (at the level of both transcription initiation and elongation) without a corresponding decrease in ppGpp levels (9). There are at least two possible explanations for the lack of a change in ppGpp concentration under one or both of these conditions. First, it is possible that other regulatory factors play a role in the feedback response induced by a change in rrn gene dose, working in conjunction with the small change in iNTP concentration. Alternatively, it is possible that the change in iNTP concentration is the only regulatory signal responsible for the specific change in rrn P1 activity under these conditions but that the small change in iNTP concentration is sufficient to cause a greater relative change in rrnB P1 promoter activity. For example, if rrnB P1 were almost completely unoccupied by RNA polymerase, one might expect that a relatively small increase in ATP concentration could cause a relatively large fold increase in promoter activity, a situation that occurs during outgrowth of cells from stationary phase (30). However, this is probably not the case in exponential phase (36). Therefore, we favor the explanation that there may be additional mediators of feedback control of rRNA synthesis in E. coli. This conclusion is in agreement with that reached by Condon et al. and Voulgaris et al., who reported that the ppGpp concentration did not decrease (9) and the ATP concentration did not increase (43) in strains with a reduced number of rRNA operons. Furthermore, these investigators noted that the activities of certain rrn P1 promoter variants that were relatively insensitive to the iNTP concentration were still subject to feedback control in strains with a reduced rrn gene dose. Thus, there might be additional regulatory signals that are induced by certain feedback conditions.

Δfis and nusB mutants do not display altered DNA supercoiling.

We did not observe a difference in the degree of negative supercoiling displayed by the same plasmid in the Δfis mutant, the nusB5 mutant, and the wild-type strain. Johnson and colleagues also did not observe altered levels of supercoiling in strains lacking fis (28; R. Johnson, personal communication). These results conflict with results in a previous report in which it was concluded that plasmids are hypersupercoiled in Δfis strains (38). We do not know the basis for this discrepancy. Since the altered concentrations of ppGpp and ATP induced in fis and nusB mutants are likely to be deleterious to cell growth in the long term, it is possible that mutations might ultimately arise in these strains that compensate for defects in rRNA synthesis by other means. One such class of mutations might increase the overall level of supercoiling in the cell. To decrease the likelihood of obtaining such second-site suppressors, we used several fresh independent transductants of the fis::kan and nusB5 alleles in each experiment.

ppGpp and iNTPs are regulatory signals linking rRNA transcription to the overall amount of translation.

Perturbation of one part of the machinery that controls rRNA transcription results in responses by other parts of the machinery to compensate for the original perturbation. Thus, the control of rRNA synthesis by small molecules demonstrates how the cell has evolved robust complex regulatory networks for control of essential biosynthetic processes.

We suggest that both ppGpp and iNTP concentrations continually fluctuate in response to slight variations in the availability of nutrients or in the activity of translating ribosomes and that rrn P1 promoters are poised to respond to these small changes, fine-tuning rRNA expression to the demand for protein synthesis in order to maintain homeostasis. However, these transient small changes in both the concentrations of small molecules and rRNA promoter activity are too small to detect with available methods. These homeostatic responses are detectable experimentally only when larger disruptions of ribosome synthesis are induced (see also references 30 and 36).

The synthesis of rRNA varies proportionally to the steady- state growth rate (growth rate-dependent control) (35). However, growth rate-dependent control of rRNA transcription is not lost in cells that cannot make ppGpp (14), and iNTP concentrations remain relatively constant at all growth rates (31; D. A. Schneider and R. L. Gourse, submitted for publication). Thus, although changing concentrations of ppGpp and iNTPs control the rapid responses of rrn P1 promoters to changes in growth phase, upshifts, and downshifts (30), they are not essential for growth rate-dependent control. Therefore, in steady-state situations, other regulators exist that are capable of conferring growth rate-dependent control of rRNA expression on bacterial cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tamas Gaal, Heath Murray, Brian Paul, and Steven Rutherford for helpful comments and Reid Johnson for discussions and unpublished information.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1 GM37048 to R.L.G. and by predoctoral fellowships from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation and a Molecular Biosciences Training Grant (N.I.H.) to D.A.S.

REFERENCES

- 1.Appleman, J. A., W. Ross, J. Salomon, and R. L. Gourse. 1998. Activation of Escherichia coli rRNA transcription by FIS during a growth cycle. J. Bacteriol. 180:1525-1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barker, M. M. 2001. Ph.D. thesis. University of Wisconsin—Madison, Madison, Wis.

- 3.Barker, M. M., T. Gaal, C. A. Josaitis, and R. L. Gourse. 2001. Mechanism of regulation of transcription initiation by ppGpp. I. Effects of ppGpp on transcription initiation in vivo and in vitro. J. Mol. Biol. 305:673-688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barker, M. M., and R. L. Gourse. 2001. Regulation of rRNA transcription correlates with nucleoside triphosphate sensing. J. Bacteriol. 183:6315-6323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartlett, M. S., T. Gaal, W. Ross, and R. L. Gourse. 1998. RNA polymerase mutants that destabilize RNA polymerase-promoter complexes alter NTP-sensing by rrn P1 promoters. J. Mol. Biol. 279:331-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartlett, M. S., and R. L. Gourse. 1994. Growth rate-dependent control of the rrnB P1 core promoter in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 176:5560-5564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cashel, M. 1969. The control of ribonucleic acid synthesis in Escherichia coli. IV. Relevance of unusual phosphorylated compounds from amino acid-starved stringent strains. J. Biol. Chem. 244:3133-3141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cashel, M., D. R. Gentry, V. H. Hernandez, and D. Vinella. 1996. The stringent response, p. 1458-1496. In F. C. Neidhardt et al. (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed., vol. 1. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 9.Condon, C., S. French, C. Squires, and C. L. Squires. 1993. Depletion of functional ribosomal RNA operons in Escherichia coli causes increased expression of the remaining intact copies. EMBO J. 12:4305-4315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Condon, C., C. Squires, and C. L. Squires. 1995. Control of rRNA transcription in Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Rev. 59:623-645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dorman, C. J., G. C. Barr, N. N. Bhriain, and C. F. Higgins. 1988. DNA supercoiling and the anaerobic and growth phase regulation of tonB gene expression. J. Bacteriol. 170:2816-2826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedman, D. I., M. Baumann, and L. S. Baron. 1976. Cooperative effects of bacterial mutations affecting lambda N gene expression. I. Isolation and characterization of a nusB mutant. Virology 73:119-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaal, T., M. S. Bartlett, W. Ross, C. L. Turnbough, Jr., and R. L. Gourse. 1997. Transcription regulation by initiating NTP concentration: rRNA synthesis in bacteria. Science 278:2092-2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaal, T., and R. L. Gourse. 1990. Guanosine 3′-diphosphate 5′-diphosphate is not required for growth rate-dependent control of rRNA synthesis in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:5533-5537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaal, T., W. Ross, E. E. Blatter, H. Tang, X. Jia, V. V. Krishnan, N. Assa-Munt, R. H. Ebright, and R. L. Gourse. 1996. DNA-binding determinants of the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase: novel DNA-binding domain architecture. Genes Dev. 10:16-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gourse, R. L., H. A. de Boer, and M. Nomura. 1986. DNA determinants of rRNA synthesis in E. coli: growth rate dependent regulation, feedback inhibition, upstream activation, antitermination. Cell 44:197-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gourse, R. L., T. Gaal, M. S. Bartlett, J. A. Appleman, and W. Ross. 1996. rRNA transcription and growth rate-dependent regulation of ribosome synthesis in Escherichia coli. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 50:645-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gourse, R. L., Y. Takebe, R. A. Sharrock, and M. Nomura. 1985. Feedback regulation of rRNA and tRNA synthesis and accumulation of free ribosomes after conditional expression of rRNA genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82:1069-1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirvonen, C. A., W. Ross, C. E. Wozniak, E. Marasco, J. R. Anthony, S. E. Aiyar, V. Newburn, and R. L. Gourse. 2001. Contributions of UP elements and the transcription factor FIS to expression from the seven rrn P1 promoters in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:6305-6314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jensen, K. F., U. Houlberg, and P. Nygaard. 1979. Thin-layer chromatographic methods to isolate 32P-labeled 5-phosphoribosyl-alpha-1-pyrophosphate (PRPP): determination of cellular PRPP pools and assay of PRPP synthetase activity. Anal. Biochem. 98:254-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jinks-Robertson, S., R. L. Gourse, and M. Nomura. 1983. Expression of rRNA and tRNA genes in Escherichia coli: evidence for feedback regulation by products of rRNA operons. Cell 33:865-876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson, R. C., C. A. Ball, D. Pfeffer, and M. I. Simon. 1988. Isolation of the gene encoding the Hin recombinational enhancer binding protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:3484-3488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson, R. C., and M. I. Simon. 1985. Hin-mediated site-specific recombination requires two 26 bp recombination sites and a 60 bp recombinational enhancer. Cell 41:781-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Josaitis, C. A., T. Gaal, and R. L. Gourse. 1995. Stringent control and growth-rate-dependent control have nonidentical promoter sequence requirements. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:1117-1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keener, J., and M. Nomura. 1996. Regulation of ribosome biosynthesis, p. 1417-1431. In F. C. Neidhardt et al. (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed., vol. 1. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 26.Lund, E., and N. O. Kjeldgaard. 1972. Metabolism of guanosine tetraphosphate in Escherichia coli. Eur. J. Biochem. 28:316-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsuo, M., Y. Ohtsuka, K. Kataoka, T. Mizushima, and K. Sekimizu. 1996. Transient relaxation of plasmid DNA in Escherichia coli by fluoroquinolones. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 48:985-987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCleod, S. 2001. Ph.D. thesis. University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, Calif.

- 29.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 30.Murray, H. D., D. A. Schneider, and R. L. Gourse. 2003. Control of rRNA expression by small molecules is dynamic and non-redundant. Mol. Cell 12:125-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petersen, C., and L. B. Moller. 2000. Invariance of the nucleoside triphosphate pools of Escherichia coli with growth rate. J. Biol. Chem. 275:3931-3935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rao, L., W. Ross, J. A. Appleman, T. Gaal, S. Leirmo, P. J. Schlax, M. T. Record, Jr., and R. L. Gourse. 1994. Factor independent activation of rrnB P1. An “extended” promoter with an upstream element that dramatically increases promoter strength. J. Mol. Biol. 235:1421-1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ross, W., K. K. Gosink, J. Salomon, K. Igarashi, C. Zou, A. Ishihama, K. Severinov, and R. L. Gourse. 1993. A third recognition element in bacterial promoters: DNA binding by the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase. Science 262:1407-1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ross, W., J. F. Thompson, J. T. Newlands, and R. L. Gourse. 1990. E. coli Fis protein activates ribosomal RNA transcription in vitro and in vivo. EMBO J. 9:3733-3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schaechter, M., O. Maaloe, and N. O. Kjeldgaard. 1958. Dependency on medium and temperature of cell size and chemical composition during balanced growth of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Gen. Microbiol. 19:592-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneider, D. A., T. Gaal, and R. L. Gourse. 2002. NTP-sensing by rRNA promoters in Escherichia coli is direct. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:8602-8607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneider, D. A., W. Ross, and R. L. Gourse. 2003. Control of rRNA expression in Escherichia coli. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6:151-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schneider, R., A. Travers, and G. Muskhelishvili. 1997. FIS modulates growth phase-dependent topological transitions of DNA in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 26:519-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharrock, R. A., R. L. Gourse, and M. Nomura. 1985. Defective antitermination of rRNA transcription and derepression of rRNA and tRNA synthesis in the nusB5 mutant of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82:5275-5279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simons, R. W., F. Houman, and N. Kleckner. 1987. Improved single and multicopy lac-based cloning vectors for protein and operon fusions. Gene 53:85-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taura, T., C. Ueguchi, K. Shiba, and K. Ito. 1992. Insertional disruption of the nusB (ssyB) gene leads to cold-sensitive growth of Escherichia coli and suppression of the secY24 mutation. Mol. Gen. Genet. 234:429-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Torres, M., C. Condon, J. M. Balada, C. Squires, and C. L. Squires. 2001. Ribosomal protein S4 is a transcription factor with properties remarkably similar to NusA, a protein involved in both non-ribosomal and ribosomal RNA antitermination. EMBO J. 20:3811-3820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Voulgaris, J., D. Pokholok, W. M. Holmes, C. Squires, and C. L. Squires. 2000. The feedback response of Escherichia coli rRNA synthesis is not identical to the mechanism of growth rate-dependent control. J. Bacteriol. 182:536-539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang, J. C., and A. S. Lynch. 1993. Transcription and DNA supercoiling. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 3:764-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]