Abstract

The Abl and Src tyrosine kinases are key signaling proteins that are of considerable interest as drug targets in cancer and many other diseases. The regulatory mechanisms that control the activity of these proteins are complex, and involve large-scale conformational changes in response to phosphorylation and other modulatory signals. The success of the Abl inhibitor imatinib in the treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia has shown the potential of kinase inhibitors, but the rise of drug resistance in patients has also shown that drugs with alternative modes of binding to the kinase are needed. The detailed understanding of mechanisms of protein–drug interaction and drug resistance through biophysical methods demands a method for the production of active protein on the milligram scale. We have developed a bacterial expression system for the kinase domains of c-Abl and c-Src, which allows for the quick expression and purification of active wild-type and mutant kinase domains by coexpression with the YopH tyrosine phosphatase. This method makes practical the use of isotopic labeling of c-Abl and c-Src for NMR studies, and is also applicable for constructs containing the SH2 and SH3 domains of the kinases.

Keywords: Src, Abl, imatinib, tyrosine kinases, biophysical methods, bacterial expression, NMR

Protein tyrosine kinases play a central role in cellular signaling. The disruption of the regulatory mechanisms that control protein tyrosine kinase activity is associated with many diseases, particularly cancer. c-Src and c-Abl are closely related nonreceptor tyrosine kinases that contain SH2 and SH3 domains in addition to the catalytic tyrosine kinase domain (Thomas and Brugge 1997; Pendergast 2002). Due to the success of the Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib (Gleevec, Glivec, STI-571, [Novartis]) in the treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia, protein kinase inhibitors have now been established as excellent therapeutic agents in the clinic (Noble et al. 2004; Krause and Van Etten 2005). The high degree of conservation in the sequences of protein kinases and the fact that most if not all kinase inhibitors are competitors of ATP, which is the common substrate of protein kinases, makes it difficult to achieve specificity for individual kinases (Capdeville et al. 2002). Considerable effort is therefore being invested in understanding the nuanced differences in conformation and dynamics that distinguish one kinase from the other. Moreover, a substantial fraction of patients undergoing treatment with imatinib develop resistance mutations in the Abl kinase domain, which render the kinase resistant to imatinib, and understanding the molecular basis of resistance is also an important issue (Shah et al. 2002; Deininger et al. 2005).

The development of new drugs targeted at protein kinases requires a better understanding of kinase regulation in general as well as the effects of resistance mutations on drug binding and kinase activity in order to be effective in the long term. Insights from in vivo studies need to be complemented by biochemical, biophysical, and structural studies. Such studies are at a surprisingly poor state of development for the tyrosine kinases. Whereas biochemical studies might require only minute amounts of protein, biophysical and structural studies demand milligram amounts of homogenous protein of exceptional stability and purity. Currently, the most often used method for the expression of the active forms of the Abl and Src kinases in the literature is by insect cell culture (Sicheri et al. 1997; Nagar et al. 2003) or with minuscule yields in bacteria (Garcia et al. 1993). Whereas insect cell culture can provide milligram amounts of protein, it is very demanding on time and cost, with the generation of a mutant protein typically in the range of 3–4 weeks. Furthermore, homogeneous isotopic labeling in cell culture is limited to 15N and 13C isotopes, and is prohibitively expensive (Strauss et al. 2003).

Previously published protocols for bacterial expression of Abl and Src have yielded microgram amounts of active glutathione S-transferase (GST) tagged proteins (Garcia et al. 1993), or have utilized inactive forms of the kinase (Williams et al. 2000). The low yields of soluble and active Src and Abl kinases using bacterial expression makes it difficult to produce sufficient amounts of protein for biophysical and structural studies. In cases where a GST tag is used to increase solubility, the heterogenous autophosphorylation of the kinase domains is another problem. Weijland et al. (1996) have previously described a yeast expression system for the catalytic domain of Src, which utilizes the coexpression of the phosphatase, PEST-PTPase, but due to proteolysis and time requirements yeast expression is not the most convenient procedure in practice. Nevertheless, the beneficial effect of protein phosphatase co-expression on the expression of protein kinases might generally be adaptable and help overcome toxic effects of protein tyrosine kinase activity in bacteria.

Here we present a method for bacterial expression of the Abl and Src kinase domains, which allows for the rapid generation, expression, and purification of wild-type and mutant protein. The method also works for producing longer constructs of these kinases.

Materials and methods

Bacterial expression of Abl and Src kinases

The kinase domains of human c-Abl (residues 229–511), human Abl 1a numbering (Oppi et al. 1987), and chicken c-Src (residues 251–533) (Takeya and Hanafusa 1983) were subcloned using NdeI and XhoI restriction sites into a pET-28a vector (Novagen) modified to yield a tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease cleavable N-terminal hexahistidine tag. We reasoned that the low yields of soluble protein with bacterial expression might be due to the uncontrolled activity of these kinases, resulting in toxicity, so we coexpressed full-length YopH phosphatase from Yersinia (Bliska et al. 1991) with the kinases in order to maintain the kinases in the dephosphorylated state. The coexpression of a tyrosine phosphatase has been shown to rescue the lethality of unregulated Src expression in yeast (Weijland et al. 1996).

The gene for YopH phosphatase was amplified by PCR and cloned into pCDFDuet-1 (Novagen) using NcoI/AvrII restriction sites, deleting the NcoI site in the final construct to yield an unambiguous start codon. The two plasmids containing the kinase (pET-28) and the phosphatase (pCDFDuet) were cotransformed into Escherichia coli BL21DE3 cells and plated on LB agar with kanamycin (50 μg/mL)/streptomycin (50 μg/mL) and grown overnight at 37° C. The next day, the colonies from the plates were resuspended in the expression media (TB kanamycin, 50 μg/mL/streptomycin, 50 μg/mL). Cultures were grown to an OD600nm of 1.2 at 37° C, cooled for 1 h with shaking at 18° C prior to induction for 16 h at 18° C with 0.2 mM IPTG. Cells were harvested by 10 min centrifugation at 7000g at 4° C and stored at −80° C or resuspended in 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 25 mM imidazole (buffer A) for immediate purification by immobilized metal affinity chromatography (Porath et al. 1975). Cells were lysed by four cycles of homogenization at 15,000 psi at 4° C. Insoluble protein and cell debris was sedimented through a 40-min centrifugation at 40,000g at 4° C.

The supernatant was filtered through a 0.22-μm filter and loaded onto an Ni affinity column (HisTrap FF, GE Lifescience), equilibrated with buffer A. The loaded column was washed with five column volumes of buffer A, and protein was eluted with a linear gradient of 0–50% of buffer B (buffer A plus 0.5 M imidazole). The peak fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and fractions containing the kinase were pooled and cleaved with 1 mg of TEV per 25 mg of crude kinase at 4° C for 16 h while dialyzing against 20 volumes of 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 1 mM DTT with a 13-kDa molecular weight cutoff membrane. The main impurity at this stage was Yop phosphatase, which tends to bind to the Ni affinity resin despite the lack of a histidine tag. Higher saturation of the resin with the higher affinity His-tagged protein decreased the nonspecific binding of phosphatase.

Subsequent anion exchange chromatography was used to remove protease and phosphatase contaminants. The dialyzed and cleaved protein was diluted twofold and loaded onto an anion exchange column (HiTrap Q FF, GE Lifescience), equilibrated with 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 5% glycerol, 1 mM DTT (buffer QA). Proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of 0–35% buffer QB (buffer QA plus 1 M NaCl), and peak fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Fractions containing the cleaved kinase were pooled, concentrated if needed, and loaded onto a size-exclusion column (S75, GE Lifescience) equilibrated with 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 1 mM DTT. Kinase domains eluted at the volume expected for monomeric protein and virtually no aggregation was detected in the void volume of the column.

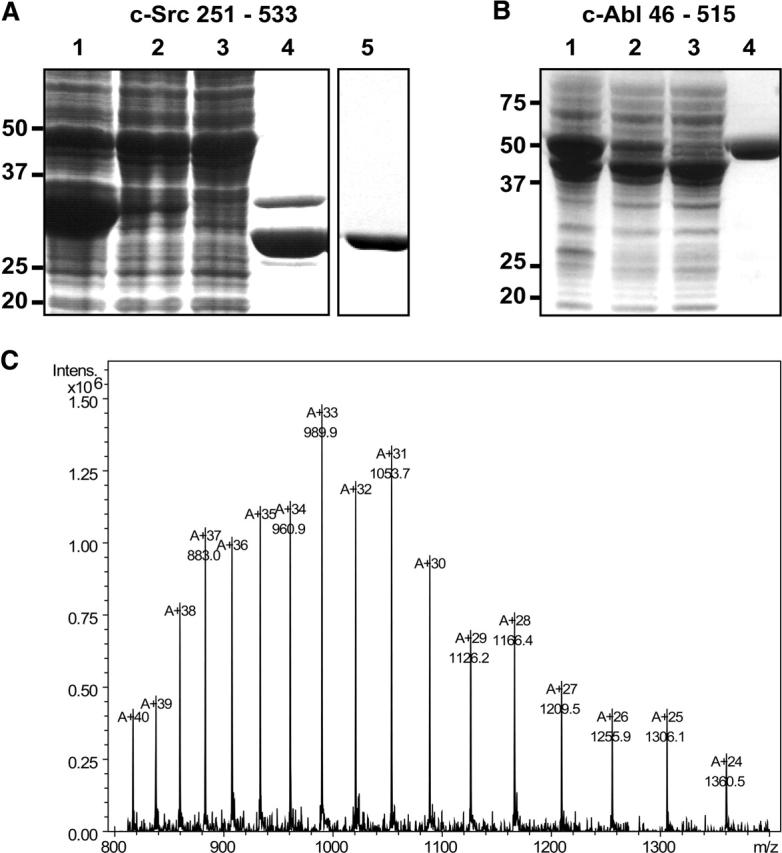

Proteins were concentrated to 10 mg/mL, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80° C. Concentration of the proteins was determined by absorbance spectroscopy at 280 nm using calculated extinction coefficients of 51,140 M−1 cm−1 for Src and 60,550 M−1cm−1 for Abl kinase domain. The protocol yields about 5–15 mg of purified and active kinase domain per liter of bacterial culture. Similar yields were obtained for longer Abl and Src constructs (Fig. 1 ▶). The identities of the proteins were confirmed by mass spectrometry, and showed no evidence for phosphorylation or other post-translational modification.

Figure 1.

Expression and purification of c-Src kinase domain and c-Abl SH3-SH2 kinase domain in bacteria. (A) Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE of c-Src kinase domain. (Lane 1) Whole-cell lysates; (lane 2) soluble protein; (lane 3) flow-through of Ni-affinity resin; (lane 4) elution from Ni-affinity resin after overnight TEV digest; (lane 5) elution from anion exchange resin. Src kinase domain expresses in high levels in bacteria but only a small fraction of the total expressed protein is soluble, as indicated by the small fraction of protein in lane 2. The His-tagged kinase binds to the Ni-affinity resin, and no kinase is found in the flow-through. After overnight dialysis and TEV digest, the major impurity is undigested kinase, still containing the His tag. Anion exchange chromatography yields homogenous and pure kinase protein. (B) Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE of c-Abl three-domain construct (SH3-SH2-kinase; residues 46 to 515). (Lane 1) Whole-cell lysates; (lane 2) soluble protein; (lane 3) flow-through Ni-affinity resin; (lane 4) elution Ni-affinity resin. Larger Abl and Src kinase domain constructs express with high yield in bacteria but are only fractionally soluble. The His-tagged kinase binds to the Ni-affinity resin and elutes with high purity from it. (C) Representative mass spectrum (electrospray–ion trap) of a Src kinase domain preparation. The calculated mass from the DNA sequence is 32,633.5 Da, the experimental mass is 32,633 Da (standard deviation 1 Da), indicating that the protein is not posttranslationally modified.

For isotopic labeling, proteins were expressed in M9 minimal media with 15N NH4Cl as the sole source of nitrogen and purified as described above. Mass spectrometry demonstrated the incorporation of the label and HSQC NMR spectra showed that the kinases were folded (data not shown).

Kinase assay

Kinase activity was monitored using a continuous spectrophotometric assay as described before (Barker et al. 1995). In brief, the consumption of ATP is coupled via the pyruvate kinase/lactate dehydrogenase enzyme pair to the oxidation of NADH, which can be monitored through the decrease in absorption at 340 nm. Reactions contained 100 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 10 mM MgCl2, 2.2 mM ATP, 1 mM phosphoenolpyruvate, 0.6 mg/mL NADH, 75 U/mL pyruvate kinase, 105 U/mL lactate dehydrogenase, and 0.5 mM substrate peptide (sequence: EAIYAAPFAKKK). Reactions (75 μL) were started through the addition of kinase at a final concentration of 30 nM, and the decrease in absorbance was monitored over 30 min at 30° C in a microtiter plate spectrophotometer (SpectraMax). The background activity of the proteins at different drug concentration was determined in experiments without the substrate peptide and subtracted from the kinase assays with the substrate peptide. Inhibitory constants were obtained through addition of 3.75 μL of imatinib in 100% DMSO or DMSO alone.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

Thermodynamic binding parameters for the binding of inhibitors to the enzymes were obtained through isothermal titration calorimetry in a VP-ITC instrument (Micro-cal) at 30° C. Proteins were exchanged into 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM TCEP, 5% DMSO on PD-10 buffer exchange columns (GE Life-science), and diluted to 10–50 μM. Imatinib stocks (purified from clinically available capsules, Novartis) in 100% DMSO were diluted 20-fold with buffer to a final concentration of 1–500 μM. The heat of binding was measured over the injection of 295 μL of drug in 12-μL steps spaced 300 sec apart. Data were fitted to a one binding site model using the Origin software package (Microcal).

Discussion

When we initiated a project to establish a bacterial expression system for the Abl and Src kinases, we found that the kinases expressed in very high yields in bacteria (~1000 mg/L of TB), but all of the expressed protein was found only in insoluble precipitates. The protein was solubilized and purified under denaturing conditions and refolded by dilution, yielding active kinase. Unfortunately, this method proved ineffective because the protein aggregated upon concentration, perhaps due to the presence of soluble aggregates, which coprecipitated soluble protein at higher concentration.

In order to increase the yield of active and soluble protein from bacteria we found that it was necessary to coexpress the kinases with a phosphatase. We chose YopH phosphatase because of its high specificity for phosphotyrosine and its lack of discrimination between substrate proteins (Zhang et al. 1992). In our expression procedure >90% of the kinase protein is still found in the insoluble fraction (Fig. 1 ▶). What is significant, however, is that the soluble fraction now contains 10–15 mg of soluble and active kinase per liter of bacterial culture. The kinase protein was characterized and found to behave identically to kinase constructs expressed in insect cell cultures (data not shown). Bacterially expressed kinase is unphosphorylated (Fig. 1C ▶), but can be autophosphorylated at the activation loop tyrosine (Y416 in c-Src and Y393 in c-Abl) upon incubation with ATP and Mg2+. The protein concentrates readily and has been successfully used for crystallization (manuscripts in preparation). The Abl kinase domain has a specific activity of 500 min−1 and a Km for substrate peptide of 70 μM. Abl kinase domain produced in this way is inhibited by imatinib with an IC50 of 0.8 μM (Fig. 2A ▶), whereas Src is insensitive to imatinib (data not shown), as expected (Druker et al. 1996).

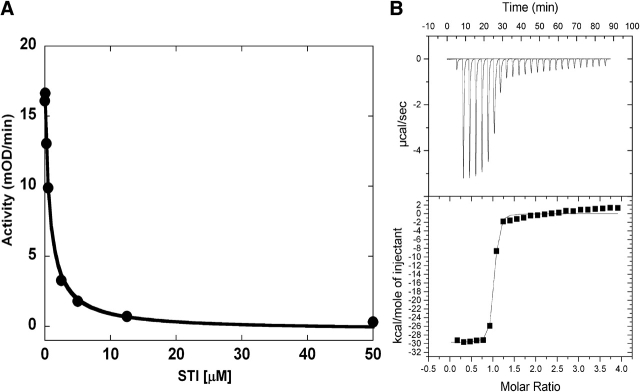

Figure 2.

Characterization of the interaction between Abl kinase domain and imatinib. (A) Kinase activity assay. Kinase activity was monitored in a continuous spectrophotometric assay against a peptide substrate and varying concentrations of imatinib. Imatinib inhibited the activity of the Abl kinase domain with an IC50 of 0.8 μM. (B) Isothermal titration calorimetry of imatinib to Abl kinase domain. Abl kinase domain binds imatinib with an affinity of 50 nM and a 1:1 stoichiometry, indicating that the protein is folded and that the concentration is determined accurately.

Isothermal titration calorimetry shows that the Abl kinase domain binds imatinib with a KD of 50 nM (Fig. 2B ▶) and a stoichiometry of 1:1, indicating that the protein concentration was determined reasonably accurately and that the protein is properly folded. The bacterial expression system enabled us to prepare homogeneously 15N-labeled Abl and Src kinase domain protein, which yield NMR spectra of promising quality and also indicate that the protein is folded (data not shown).

The striking effect of phosphatase coexpression on the bacterial expression of Abl and Src kinases may be adaptable to other kinases in the tyrosine kinase family. Even though this expression system may not solve expression problems for all tyrosine kinases, we are encouraged by the finding that constructs containing the SH3 and SH2 domains as well as the kinase domain can also be expressed in similar yields by a straightforward extension of this method (Fig. 1B ▶).

Acknowledgments

M.A.S. is a Johnson and Johnson Fellow of the Life Science Research Foundation.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.051750905.

References

- Barker, S.C., Kassel, D.B., Weigl, D., Huang, X., Luther, M.A., and Knight, W.B. 1995. Characterization of pp60c-src tyrosine kinase activities using a continuous assay: Autoactivation of the enzyme is an intermolecular autophosphorylation process. Biochemistry 34 14843–14851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliska, J.B., Guan, K.L., Dixon, J.E., and Falkow, S. 1991. Tyrosine phosphate hydrolysis of host proteins by an essential Yersinia virulence determinant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 88 1187–1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capdeville, R., Buchdunger, E., Zimmermann, J., and Matter, A. 2002. Glivec (STI571, imatinib), a rationally developed, targeted anticancer drug. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 1 493–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deininger, M., Buchdunger, E., and Druker, B.J. 2005. The development of imatinib as a therapeutic agent for chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood 105 2640–2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druker, B.J., Tamura, S., Buchdunger, E., Ohno, S., Segal, G.M., Fanning, S., Zimmermann, J., and Lydon, N.B. 1996. Effects of a selective inhibitor of the Abl tyrosine kinase on the growth of Bcr-Abl positive cells. Nat. Med. 2 561–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, P., Shoelson, S.E., George, S.T., Hinds, D.A., Goldberg, A.R., and Miller, W.T. 1993. Phosphorylation of synthetic peptides containing Tyr-Met-X-Met motifs by nonreceptor tyrosine kinases in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 268 25146–25151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause, D.S. and Van Etten, R.A. 2005. Tyrosine kinases as targets for cancer therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 353 172–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagar, B., Hantschel, O., Young, M.A., Scheffzek, K., Veach, D., Bornmann, W., Clarkson, B., Superti-Furga, G., and Kuriyan, J. 2003. Structural basis for the autoinhibition of c-Abl tyrosine kinase. Cell 112 859–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble, M.E., Endicott, J.A., and Johnson, L.N. 2004. Protein kinase inhibitors: Insights into drug design from structure. Science 303 1800–1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppi, C., Shore, S.K., and Reddy, E.P. 1987. Nucleotide sequence of testis-derived c-abl cDNAs: Implications for testis-specific transcription and abl oncogene activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 84 8200–8204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendergast, A.M. 2002. The Abl family kinases: Mechanisms of regulation and signaling. Adv. Cancer Res. 85 51–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porath, J., Carlsson, J., Olsson, I., and Belfrage, G. 1975. Metal chelate affinity chromatography, a new approach to protein fractionation. Nature 258 598–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah, N.P., Nicoll, J.M., Nagar, B., Gorre, M.E., Paquette, R.L., Kuriyan, J., and Sawyers, C.L. 2002. Multiple BCR-ABL kinase domain mutations confer polyclonal resistance to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib (STI571) in chronic phase and blast crisis chronic myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell 2 117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicheri, F., Moarefi, I., and Kuriyan, J. 1997. Crystal structure of the Src family tyrosine kinase Hck. Nature 385 602–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A., Bitsch, F., Cutting, B., Fendrich, G., Graff, P., Liebetanz, J., Zurini, M., and Jahnke, W. 2003. Amino-acid-type selective isotope labeling of proteins expressed in Baculovirus-infected insect cells useful for NMR studies. J. Biomol. NMR 26 367–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeya, T. and Hanafusa, H. 1983. Structure and sequence of the cellular gene homologous to the RSV src gene and the mechanism for generating the transforming virus. Cell 32 881–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, S.M. and Brugge, J.S. 1997. Cellular functions regulated by Src family kinases. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 13 513–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weijland, A., Neubauer, G., Courtneidge, S.A., Mann, M., Wierenga, R.K., and Superti-Furga, G. 1996. The purification and characterization of the catalytic domain of Src expressed in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Comparison of unphosphorylated and tyrosine phosphorylated species. Eur. J. Biochem. 240 756–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.M., Wang, D., and Cole, P.A. 2000. Chemical rescue of a mutant protein-tyrosine kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 275 38127–38130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.Y., Clemens, J.C., Schubert, H.L., Stuckey, J.A., Fischer, M.W., Hume, D.M., Saper, M.A., and Dixon, J.E. 1992. Expression, purification, and physicochemical characterization of a recombinant Yersinia protein tyrosine phosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 267 23759–23766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]