Abstract

We describe in molecular detail how disruption of an intermonomer salt bridge (Arg337–Asp352) leads to partial destabilization of the p53 tetramerization domain and a dramatically increased propensity to form amyloid fibrils. At pH 4.0 and 37°C, a p53 tetramerization domain mutant (p53tet-R337H), associated with adrenocortical carcinoma in children, readily formed amyloid fibrils, while the wild-type (p53tet-wt) did not. We characterized these proteins by equilibrium denaturation, 13Cα secondary chemical shifts, {1H}-15N heteronuclear NOEs, and H/D exchange. Although p53tet-R337H was thermodynamically less stable, NMR data indicated that the two proteins had similar secondary structure and molecular dynamics. NMR derived pKa values indicated that at low pH the R337H mutation partially disrupted an intermonomer salt bridge. Backbone H/D exchange results showed that for at least a small population of p53tet-R337H molecules disruption of this salt bridge resulted in partial destabilization of the protein. It is proposed that this decrease in p53tet-R337H stability resulted in an increased propensity to form amyloid fibrils.

Keywords: p53 tetramerization domain, amyloid fibrils, salt bridge, pKa, hydrogen exchange

Human amyloid diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, are characterized by the deposition and accumulation of specific proteins in the form of amyloid fibrils and plaques (Xing and Higuchi 2002; Stefani and Dobson 2003; Uversky and Fink 2004). There is also increasing evidence that amyloid fibril formation may represent an alternative, aberrant folding pathway for most if not all proteins (Stefani and Dobson 2003). Many proteins with no sequence or structural similarity can be induced to convert into the common cross-β polymer structure characteristic of amyloid fibrils (Sunde and Blake 1997; Sunde et al. 1997). It is well established that partial or complete unfolding of a protein is required prior to amyloid fibril formation (Booth et al. 1997; Kelly 1997; Ramirez-Alvarado et al. 2000; Rochet and Lansbury 2000; Fandrich et al. 2003; Uversky and Fink 2004). Destabilization of the native fold of a protein may result from introduction of a missense mutation (Conaway et al. 1998), proteolytic cleavage (Selkoe 1994; Ratnaswamy et al. 1999; Roher et al. 2000), or variation of solvent conditions by changing pH or adding organic solvents (Chiti et al. 1999).

We have recently reported that the tetramerization domain of wild-type p53 (p53tet-wt) and a p53 mutant (53tet-R337H) associated with adrenocortical carcinoma in children (Ribeiro et al. 2001) can be converted to amyloid-like fibrils at pH 4.0 (Lee et al. 2003). The R337H p53 mutant is of particular interest since, unlike most inherited p53-associated cancers that lead to a broad spectrum of cancer types, it is only associated with a specific cancer (adrenocortical carcinoma) in children. Interestingly, the cancer-associated mutant protein, p53tet-R337H, had a significantly increased propensity to form fibrils compared to the wild type (Lee et al. 2003). It is worth noting that although fibril formation occurred at relatively low pH many disease-associated amyloidogenic proteins require nonphysiological conditions (e.g., low pH, high temperature, etc.) to be readily converted to fibrils in vitro (Uversky and Fink 2004). In addition, more recent studies have shown that the p53 core DNA-binding domain can also be converted to amyloid fibrils in vitro (Ishimaru et al. 2003). We have previously proposed that conversion of mutant p53 to highly stable, protease-resistant amyloid fibrils may contribute to the observed nuclear accumulation of mutant p53 in adrenocortical carcinoma cells and possibly other cancer cells. Besides its potential role in cancer, the p53tet domain is relatively small (6 kDa) and has been well characterized (Stürzbecher et al. 1992; Clubb et al. 1995; Johnson et al. 1995; McCoy et al. 1997; Davison et al. 1998, 2001; Lomax et al. 1998; Mateu and Fersht 1998 Mateu and Fersht 1999; Mateu et al. 1999; Noolandi et al. 2000; Chene 2001; Neira and Mateu 2001; DiGiammarino et al. 2002; Lee et al. 2003). For these reasons this domain represents an ideal model system for studying amyloid fibril formation.

The structure of the p53 tetramerization domain has been determined by solution NMR spectroscopy (Lee et al. 1994; Clore et al. 1995) and X-ray crystallography (Jeffrey et al. 1995). Each monomer is comprised of a β-strand (residues 326–333), a tight turn, and an α-helix (residues 335–353 or to 355, depending on the model). The tetramer is composed of a dimer of dimers, with each dimer formed by an anti-parallel β-sheet and two anti-parallel α-helices. The two dimers are arranged in an approximately orthogonal manner and are stabilized by many energetically favorable forces, including hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds, and, in particular, an intermonomer salt bridge between residues Arg337 and Asp352 (Lee et al. 1994).

In these studies we have shown that p53tet-R337H readily formed fibrils at pH 4.0 and 37°C, while p53tet-wt did not. This provides the opportunity to use various equilibrium methods to identify differences in the structure and/or dynamics of the fibril-prone p53tet domain, and the fibril-resistant wild-type domain, that account for the mutant domain’s heightened propensity to form fibrils.

Chemical denaturation, H/D exchange, and direct NMR measurements of secondary structure and conformational dynamics were used to define the structural determinants responsible for this difference in propensity to form amyloid fibrils. Although there was little difference in structure and dynamics between these proteins, chemical denaturation studies demonstrated significant differences in their stabilities. One possible explanation for this was that under the conditions of the NMR experiments (pH 4.0, 20°C), only a small population of the mutant protein may be partially unfolded at any time. This was further supported by H/D exchange studies that showed significant differences in the solvent accessibilities of backbone amide protons for at least a fraction of the mutant protein molecules. NMR was used to estimate pKa values of acidic residues that, to differing extents, stabilize the tetramerization domain through the formation of salt bridges. These studies revealed that the salt bridge between residues 337 and 352 was significantly weakened by substitution of Arg337 with His. The weakening of this salt bridge and the unfavorable substitution of Arg337 by a shorter His residue resulted in partial unfolding of the tetramerization domain and an increased tendency to form amyloid fibrils. Overall, this work provides detailed molecular insights into the structural differences between p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H, which lead to the latter having a heightened propensity to form amyloid fibrils.

Results

p53tet-R337H readily forms fibrils at pH 4.0 and 37°C while p53tet-wt does not

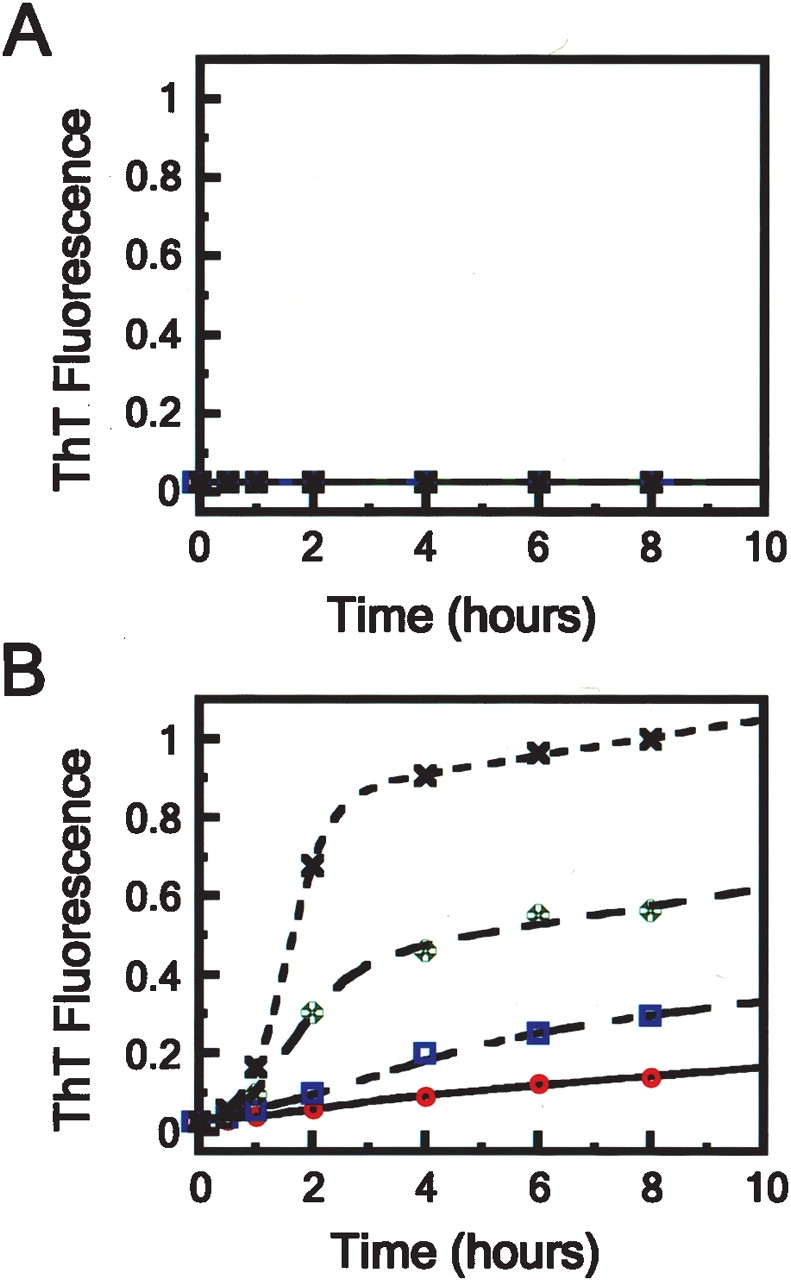

The time-dependence of fibril formation for p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H was monitored at pH 4.0 and 37°C using the fluorescent dye Thioflavin T (ThT). Under these conditions, p53tet-wt did not form detectable levels of fibrils over an 8-h period (Fig. 1A ▶). However, p53tet-R337H readily formed fibrils in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1B ▶; Supplementary Fig. 1). Fibril formation occurred via a nucleation-dependent elongation mechanism (Nielsen et al. 2001) in which fibril assembly progresses through an initial lag phase, a growth phase, and finally an equilibrium phase. These results showed that substitution of Arg337 by His in the p53tet domain lead to a dramatic increase in propensity to form fibrils at pH 4.0 and 37°C.

Figure 1.

Influence of protein concentration upon the formation of amyloid fibrils by (A) p53tet-wt and (B) p53tet-R337H monitored by ThT fluorescence at pH 4.0 and 37°C. Protein concentrations were 1.0 (×), 0.5 (✠), 0.25 (□), and 0.13 (°) mM. Data were fitted to sigmoidal curves according to equation 8.

Conformational stability of p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H

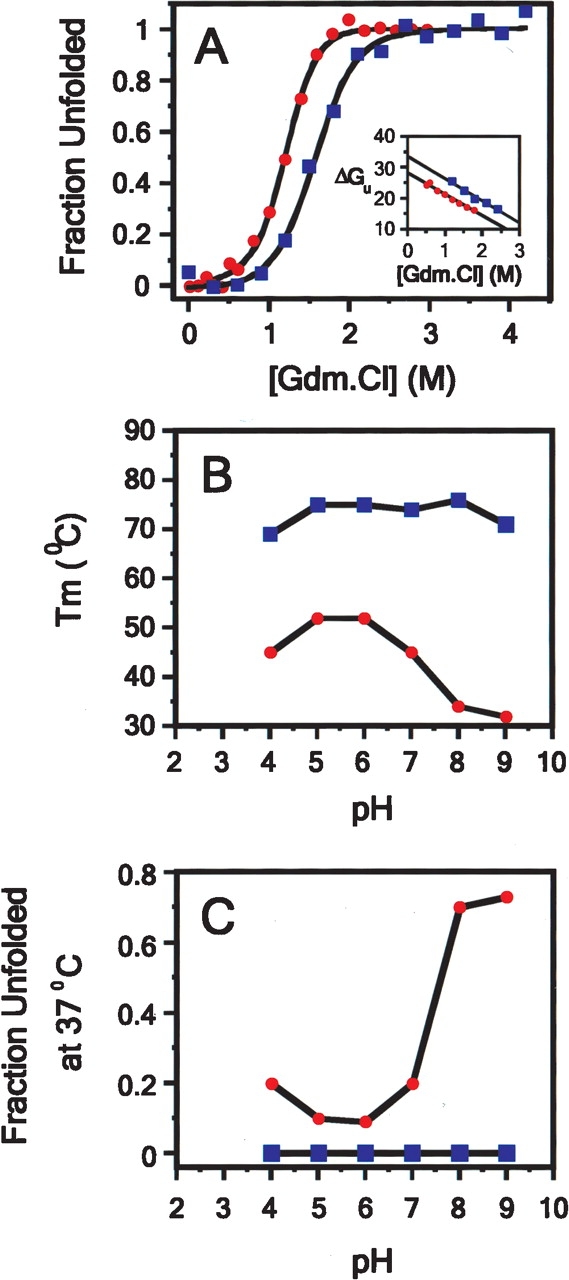

Various biophysical studies were undertaken to determine the effect(s) of the R337H mutation upon the p53tet domain structure. First, the stabilities of p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H were determined by chemical denaturation with guanidine hydrochloride at pH 4.0 and 25°C (Fig. 2A ▶). Data were fit to a two-state model and gave similar m values for p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H (7.26 ± 0.67 and 6.92 ± 0.43 kcal mol−1 M−1, respectively). The free energy of denaturation (ΔGuH2O) for p53tet-wt under these conditions (pH 4.0, 25°C) was 33.7 ± 0.6 kcal mol−1, which is similar to that reported previously by Mateu and coworkers (32.5 ± 0.5 kcal mol−1) at pH 7.0 and 25°C. The ΔGuH2O value for p53tet-R337H was 28.2 ± 0.5 kcal mol−1 and the calculated free energy on mutation, ΔΔGu[D]50%, was 4.6 ± 0.6 kcal mol−1 (ΔΔGuH2O was 5.50 ± 0.8 kcal mol−1), indicating that p53tet-R337H was thermodynamically less stable than the wild-type domain. Interestingly, Mateu and coworkers (Mateu et al. 1999) had previously reported values of 23.1 ± 0.4 kcal mol−1 (10.0 ± 0.3 kcal mol−1 for Δ ΔGu[D] 50% and 9.3 ± 0.6 kcal mol−1 for Δ ΔGuH2O) and 30.3 ± 0.5 kcal mol−1 (2.7 ± 0.1 kcal mol−1 for Δ ΔGu[D] 50% and 2.2 ± 0.7 kcal mol−1 for Δ ΔGuH2O) for the p53tet mutants R337A and D352A, respectively, at pH 7.0 and 25°C (Mateu and Fersht 1998; Mateu et al. 1999). It was argued that the Arg337–Asp352 salt bridge did not contribute significantly to protein stability, while substitution of Arg337, which is partially buried, leaves a thermodynamically unfavorable cavity in the protein. Another possible explanation for the results reported by Mateu and coworkers (Mateu et al. 1999) may be that another acidic group may substitute for Asp352 in the D352A mutant (D. Bashford, pers. comm.). On the other hand, the lower value obtained for the p53tet-R337H mutant could be due to a decrease in stability of the mutant as a consequence of substitution of Arg by the shorter and bulkier His residue.

Figure 2.

Guanidium and thermal denaturation studies of p53tet-wt (□) and p53tet-R337H (•) in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 4.0, containing 50 mM NaCl at 25°C. (A) Guanidium denaturation curves for p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H. The fraction of unfolded protein was determined using equation 2, and data were fitted according to equation 3. (Inset) Free energy of unfolding (ΔGu) in units of kcal mol−1 calculated using equation 4 plotted against denaturant concentration. (B) Variation of melting temperature (Tm) and (C) fraction unfolded protein (37°C) with pH for p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H (DiGiammarino et al. 2002; Lee et al. 2003).

Previous thermal denaturation studies (DiGiammarino et al. 2002; Lee et al. 2003) had also shown that p53tet-R337H is less stable than p53tet-wt (summarized in Fig. 2B,C ▶). The melting temperature (Tm) for the mutant was ~20°C less than that for the wild type at pH 5.0 and 6.0 (Fig. 2B ▶). This difference in Tm values was even more pronounced at higher pH (31°C vs. 70°C for p53tet-R337H and p53tet-wt, respectively, at pH 9.0). On the other hand, Tm values for both the mutant and wild type decreased slightly (~5°C) upon lowering the pH from 5.0 to 4.0.

These differences in Tm values between p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H were also reflected in the fraction of unfolded protein present at 37°C (Fig. 2C ▶). Significantly more of the mutant protein was unfolded at higher and lower pH values (80% at pH 9.0 and 20% at pH 4.0).

Structural and dynamic properties of p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H

NMR is particularly useful for gaining residue-specific information about the denatured and partially folded states of proteins (Wüthrich 1994; Shortle 1996). Therefore, we utilized a number of NMR techniques to gain more detailed insight into the structural and/or dynamic properties of these proteins that may contribute to their difference in propensity to form amyloid fibrils.

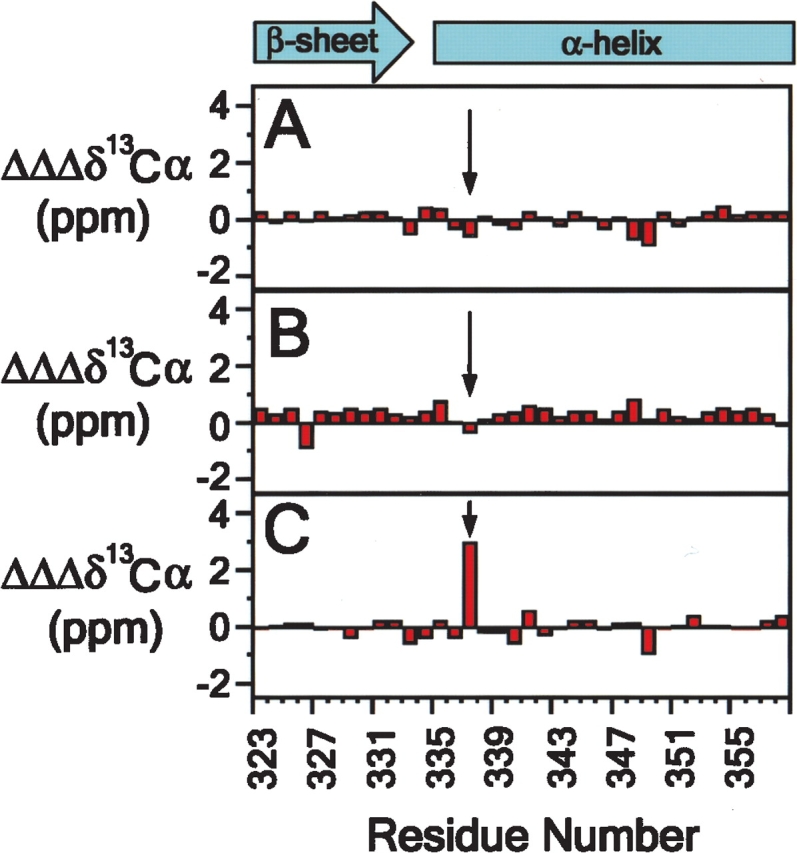

Backbone amide resonance assignments were determined for p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H at pH 4.0 and 6.0 (Supplementary Fig. 2). 13Cα secondary chemical shift data showed no apparent change in the secondary structure of p53tet-wt or p53tet-R337H upon decreasing the pH from 6.0 to 4.0 (Fig. 3A,B ▶; Supplementary Fig. 3). In contrast, the secondary 13Cα chemical shift values for the mutated residue at position 337 differ significantly between p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H at pH 4.0 (Fig. 3C ▶; Supplementary Fig. 3). This may reflect a minor kink in the helix at this position. These data indicate that, on average, over large ensembles of molecules and at a temperature that does not favor rapid fibril formation (20°C), the secondary structures of p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H are similar and do not vary between pH 6.0 and 4.0.

Figure 3.

p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H possess similar secondary structure over a range of pH values. Differences in secondary 13Cα chemical shift values for p53tet-wt (A) and p53tet-R337H (B) at pH 4.0 and 6.0 (pH 4.0 data minus pH 6.0 data) and secondary 13Cα chemical shift differences between p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H (C) at pH 4.0 (p53tet-wt data minus p53tet-R337H data).

{1H}-15N heteronuclear NOE data showed that backbone amides for residues comprising the β-strands and α-helices of the p53tet domain are relatively rigid at pH 4.0 and 20°C (Supplementary Fig. 4). Comparison of {1H}-15N heteronuclear NOE data for p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H revealed that the backbone dynamics of these proteins were very similar. The most significant divergence in {1H}-15N heteronuclear NOE values was observed for Glu339; however, the reason for this difference was not apparent. Overall, the {1H}-15N heteronuclear NOE data showed that there was very little difference in the backbone dynamics of p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H on the low nanosecond to high picosecond timescale.

Overall, the secondary structure and backbone dynamics data do not reflect the decreased stability observed for p53tet-R337H by equilibrium chemical denaturation experiments. One possible explanation for this is that protein unfolding may occur on a timescale that is not probed by the {1H}-15N heteronuclear NOE experiment; for example, timescales longer than tens of nanoseconds. Another possibility is that, under the conditions of the NMR experiments (pH 4.0 and 20°C), only a small population of the mutant protein may be partially unfolded at any time. In fact, raising the temperature to >30°C resulted in rapid fibril formation, suggesting that at higher temperatures the population of partially unfolded molecules was sufficiently high to nucleate conversion to fibrils.

Native state hydrogen (H/D) exchange studies of p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H at pH 4.0 and 20°C

Native state H/D exchange is ideal for monitoring local and global fluctuations in protein structure which may occur over extended periods of time and for detecting rare (partial) unfolding events which may occur in only a small fraction of molecules at any given time (Bai et al. 1995). Therefore, H/D exchange was used to probe for differences in the structure and dynamics of p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H, which may account for the mutant having an increased propensity to form amyloid fibrils.

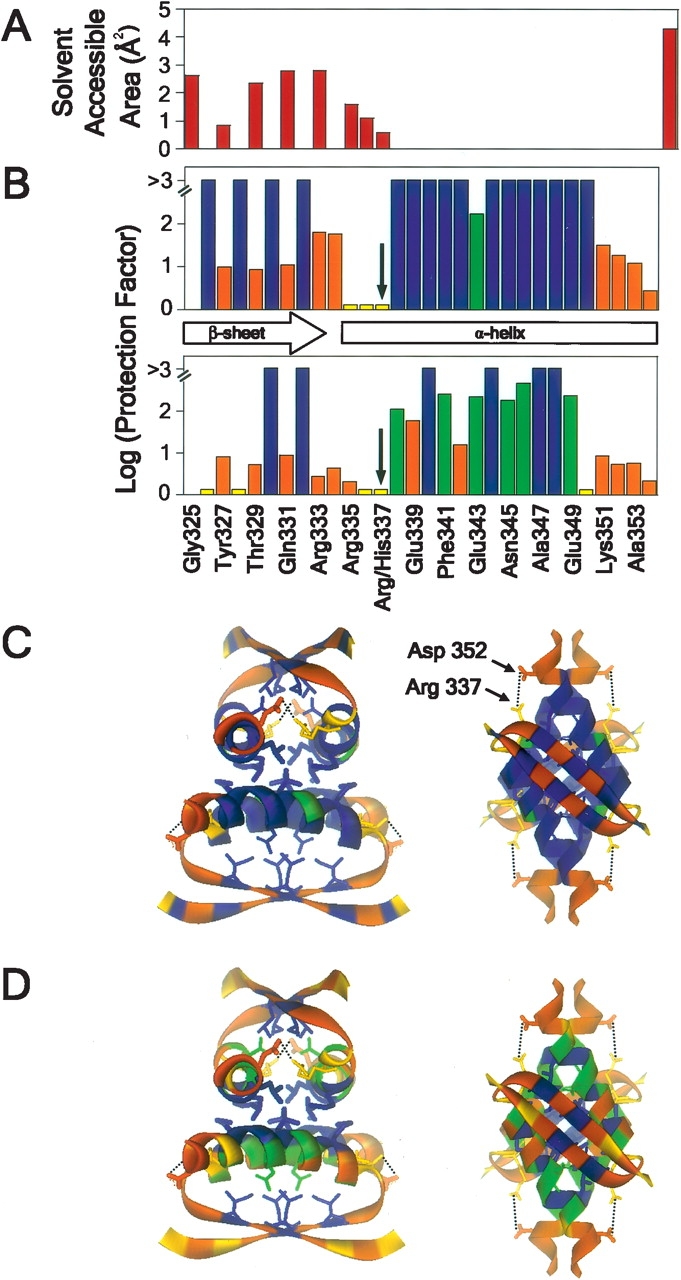

H/D exchange rates were measured for p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H at pH 4.0 and 20°C and plotted as log protection factor for each residue (Fig. 4B–D ▶). These data correlated well with the measured solvent exposed area for backbone amide nitrogen atoms based on the p53tet X-ray crystal structure (Fig. 4A ▶). However, H/D exchange was observed for the backbone amides of several residues at the C terminus of the α-helix. This is probably due to fraying of the α-helix in this region in solution; in crystals, this was not observed, probably due to the influence of crystal packing forces.

Figure 4.

Difference in extent of backbone amide hydrogen exchange for p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H at pH 4.0 and 20°C. (A) Surface-accessible area for backbone amide nitrogen atoms determined using the program GETAREA 1.1 (Fraczkiewicz and Braun 1998). (B) Log protection factor for residues in p53tet-wt (top) and p53tet-R337H (bottom). Ribbon diagram representation of the NMR solution structure of p53tet-wt (1PES; Lee et al. 1994) was used to illustrate the extent of hydrogen exchange for residues of (C) p53tet-wt and (D) p53tet-R337H using the program WebLab Viewer. Log protection factors >3 are shown in blue, between 0.1 and 3 are in green, and fast exchangers are in orange.

The H/D exchange data obtained for p53tet-wt were in good agreement with those obtained previously by Neira and Mateu (2001) at pH 7.0 and 25°C. Amide moieties that were involved in hydrogen bonds in elements of secondary structure and/or buried and inaccessible to solvent exchange, exhibited negligible H/D exchange (protection factors > 103) (Fig. 4B ▶). Overall, the H/D exchange profile for p53tet-wt indicated that this domain was stable, and that its structure and dynamics at pH 4.0 and 20°C were very similar to those observed at pH 7.0.

In contrast, for at least a small population of p53tet-R337H molecules, many backbone amide protons exhibited only limited protection from H/D exchange. While backbone amide protons for Leu330 and Ile332 remained highly protected, those for Glu326 and Phe-328 exhibited high rates of exchange, suggesting that the β-sheets were less stable than in the wild type (Fig. 4B,D ▶). Furthermore, many helical backbone amide protons that were highly protected in p53tet-wt exhibited H/D exchange in p53tet-R337H due to a decreased stability of the α-helices. Interestingly, the side chains for backbone amide protons that remained highly protected in the β-sheet and α-helical regions of p53tet-R337H (Leu330, Ile332, Met340, Leu344, Ala347, and Leu-348), were involved in hydrophobic packing interactions within the core of each dimer and the tetramer interface (Fig. 4D ▶). Overall, the H/D exchange data indicated that at pH 4.0 and 20°C p53tet-wt had a rigid structure, whereas a portion of the p53tet-R337H molecules had a significantly “looser” structure characterized by lower thermodynamic stability.

pH Titration of acidic and basic residues of p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H

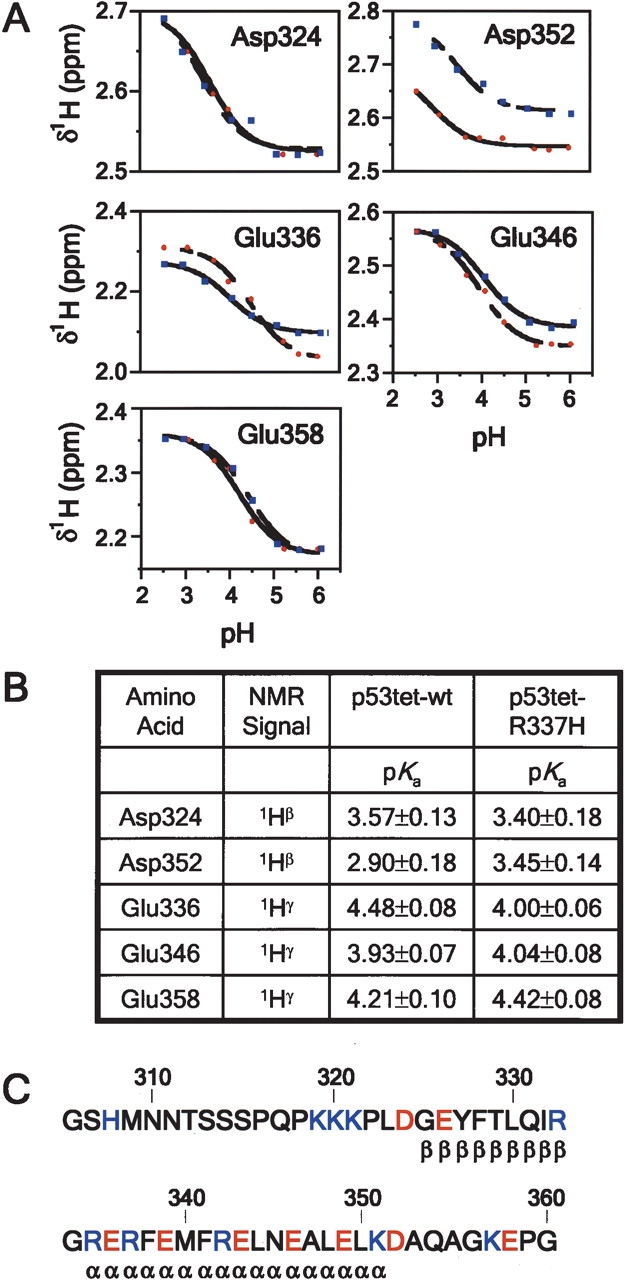

We surmised that disruption of the salt bridge between residues 337 and 352 may contribute to the difference in stability between p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H at pH 4.0. To investigate this possibility we used NMR to determine the residue-specific pKa values for Asp324, Asp352, Glu336, Glu346, and Glu358 of p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H (Fig. 5 ▶). pKa values for other acidic residues (i.e., Glu326, Glu339, Glu343, and Glu349) could not be determined due to resonance overlap.

Figure 5.

pKa values for acidic residues of p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H. (A) Proton chemical shift titration curves for aspartate (1Hβ) and glutamate (1Hγ) residues of p53tet-wt (blue squares) and p53tet-R337H (red circles). Data were fit to the Henderson-Hasselbach equation as outlined under Materials and Methods. (B) Measured pKa values for acidic residues of p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H. (C) Amino acid sequence of the wild-type p53 tetramerization domain. Acidic residues are shown in red and basic residues are shown in blue.

The solvent-exposed residues, Asp324 and Glu358, which lie within the flexible N- and C-terminal regions of the p53tet domain, exhibited similar pH titration curves and pKa values in p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H (Fig. 5A–C ▶). The pKa values for Glu358 (4.21 ± 0.10 and 4.42 ± 0.08 for p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H, respectively) were close to standard values determined for model compounds (4.3–4.5) (Tanford 1962). Conversely, pKa values for Asp324 (3.57 ± 0.13 and 3.40 ± 0.18 for p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H, respectively) were slightly perturbed from standard values (3.9–4.0) possibly due to the close proximity of a cluster of positively charged lysine residues (Lys319, Lys320, and Lys321) (Fig. 5C ▶).

We observed a difference in the pKa value for Glu336 (4.48 ± 0.08 and 4.00 ± 0.06 for p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H, respectively), which may be due to the difference in sequence between the two proteins at position 337 (Arg vs. His). In addition, the pKa value for Glu346 (3.93 ± 0.07 and 4.04 ± 0.08 for p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H, respectively) was slightly lower than standard values, implying that this residue may interact with another residue in the p53tet domain.

Importantly, a significant difference was observed for the pH titration curves and pKa values for Asp352 (2.90 ± 0.18 and 3.45± 0.14 for p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H, respectively). The pKa for Asp352 of p53tet-wt (2.90 ± 0.18) was significantly lower than standard values (3.9–4.0). This difference in pKa values is most likely due to the strongly stabilizing effect of the positively charged Arg337 on the negative charge of Asp-352. On the other hand, Asp352 of p53tet-R337H (3.45 ± 0.14) had a higher pKa but it was still lower than that reported for model compounds. This suggested that the R337H mutation resulted in a significantly weaker salt bridge in p53tet-R337H than in p53tet-wt.

Discussion

In previous studies we have reported that a p53tet domain mutant, p53tet-R337H, exhibited an increased propensity to form amyloid fibrils compared to the wild type (DiGiammarino et al. 2002; Lee et al. 2003). Although it is well established that partial destabilization of a protein is required for conversion to amyloid fibrils, it was unclear how mutation of Arg337, which is involved in an intermonomer salt bridge, resulted in a partial destabilization of the tetramerization domain and an increased propensity to form amyloid fibrils.

13Cα secondary chemical shift and heteronuclear {1H}-15N NOE data showed that there was little difference in the secondary structure or backbone dynamics of p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H at pH 4.0 and 20°C. However, NMR-based native state H/D exchange showed a dramatic difference in H/D exchange rates between these proteins. These results indicated that a small population of p53tet-R337H molecules are partially destabilized under these conditions, leading to an increased rate of solvent exchange with buried backbone amides. Increased rates of H/D exchange were observed at the ends of the β-sheets and throughout the α-helices of the tetramerization domain. This “loosening” of the mutant domain structure would account for its lower thermodynamic stability compared to the wild type, and presumably its increased propensity to form amyloid fibrils.

In fact, thermal denaturation studies had previously shown that the melting temperature for p53tet-R337H was ~20°C lower than that for p53tet-wt between pH 4.0 and 6.0 (DiGiammarino et al. 2002; Lee et al. 2003). This indicated that the mutant protein was significantly less thermodynamically stable than the wild type. This difference in stability could be due to unfavorable steric effects which occur upon substitution of Arg337 by the shorter and bulkier side chain of the His residue. The structure of the mutant molecule may need to be slightly rearranged in order to accommodate the bulkier side chain of the His residue. This would account for the increase in backbone solvent accessibility observed for p53tet-R337H by H/D exchange, but it did not explain our previously reported observation that fibril formation by p53tet-R337H was pH-dependent (Lee et al. 2003). The mutant readily formed fibrils at pH 4.0 but not at higher pH. These earlier results suggested that fibril formation was dependent upon the protonation of acidic residues (Asp or Glu) at low pH. However, since all acidic residues (except Asp352, which forms a salt bridge with Arg337) are solvent exposed, it is unlikely that protonation of these residues would affect the stability of the p53tet domain (Kumar and Nussinov 2002a; Bosshard et al. 2004). Alternately, it is possible that protonation of Asp352 may result in a partial disruption of the intermolecular salt bridge between adjacent monomers in p53tet-R337H.

We had previously shown that diminished stability of p53tet-R337H at high pH (pH 8.0 and above) was due to deprotonation and neutralization of the positive charge on His337 (pKa = 7.7), leading to disruption of the His337–Asp352 intermonomer salt bridge (DiGiammarino et al. 2002; Fig. 4C,D ▶). Though at pH 4.0 His337 is positively charged, this could not account for the observed loss in stability at this pH. However, measured pKa values for Asp352 in the wild-type and mutant p53tet domains indicated that it formed a significantly weaker salt bridge with His337 in p53tet-R337H than with Arg337 in p53tet-wt. There are several factors that may contribute to the disruption of this salt bridge. Firstly, substitution of Arg337 by a shorter His residue would result in an increased distance between the residues forming this salt bridge. Since the charged carboxylate and imidazolium moieties of these residues are exposed to solvent, there would be a substantial reduction in the electrostatic interaction between these groups due to the high dielectric constant of water. Secondly, His may not adopt a favorable geometry for the formation of a strong electrostatic interaction with Asp352 (Kumar and Nussinov 2002b). However, although distance and geometry are likely to play a role in the weakening of this salt bridge, these effects would be similar at pH 4.0 and 6.0. Thirdly, the measured pKa values for Asp352 indicate that at pH 4.0 a significant proportion of Asp352 in p53tet-R337H would be protonated, leaving a positively charged His residue at the N terminus of each helix that was no longer neutralized by interaction with Asp352. It is likely that the resulting destabilizing electrostatic repulsion between the positive charge on His337 and the N-terminal helix macrodipole (Armstrong and Baldwin 1993; Cochran and Doig 2001; Cochran et al. 2001; Iqbalsyah and Doig 2004) contribute to the loss in stability and increase in backbone H/D exchange within the helical region of p53tet-R337H at pH 4.0.

It is evident from our results that the combined effects of a sterically unfavorable substitution of Arg337 by a His residue and protonation of Asp352 at pH 4.0 lead to partial loss of the intermonomer salt bridge. These unfavorable steric effects, along with loss of the salt bridge, lead to a destabilization of the p53tet domain in at least a small population of p53tet-R337H molecules, giving rise to an increased propensity to form amyloid fibrils.

These findings not only provide detailed molecular insights into how disruption of an intermonomer salt bridge in the p53tet domain contributes to an increased propensity to form amyloid fibrils, but may also have relevance to p53-related cancers. We have previously proposed that conversion of mutant p53 to highly stable, protease-resistant amyloid fibrils may contribute to the observed inactivation and accumulation of mutant p53 in adrenocortical carcinoma cells and possibly other cancer cells (Lee et al. 2003). In fact, it has been recently reported that the p53 core DNA-binding domain can also be converted to amyloid fibrils in vitro (Ishimaru et al. 2003). However, at this time, the possible connection between p53 amyloid formation and cancer remains highly speculative.

More importantly, however, the detailed structural and dynamic studies reported in these studies provide insight into the mechanism of inactivation of a p53 mutant, which, unlike most inherited p53-associated cancers that lead to a broad spectrum of cancer types, is only associated with a specific cancer (adrenocortical carcinoma) in children.

Materials and methods

Materials

Deuterium oxide (99.5% D2O) and sodium 3-trimethylsilyl-(2,2,3,3-2H4) propionate (TSP) were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories; guanidine hydrochloride (GdnHCl) was from Sigma-Aldrich. GdnHCl was dissolved in D2O and lyophilized three times in order to exchange labile protons with deuterium.

Expression and purification of p53tet

Proteins were expressed and purified as previously reported (DiGiammarino et al. 2002). Unlabeled, 15N-labeled, and 13C/15N-labeled p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H were prepared by culturing BL21(DE3) cells in isotope-labeled MOPS-based minimal media (Neidhardt et al. 1974). For 15N labeling, 15N-ammonium chloride was used; for 13C/15N-labeling, 13C-glucose was also used. The proteins were purified as previously reported (DiGiammarino et al. 2002). Protein purity and identity was confirmed using sodium dodecyl sulphate polyacryl-amide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and mass spectrometry, respectively. Protein concentrations were determined using absorbance at 280 nm measured in the presence of 6 M guanidine hydrochloride in 20 mM sodium phosphate at pH 6.5 (Gill and von Hippel 1989). The molar extinction coefficient at 280 nm was 1280 M−1 cm−1 for both p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H, as determined using the ProteinParameters Web site (http://us.expasy.org/tools/protparam.html).

Equilibrium unfolding experiments

Chemical denaturation equilibrium experiments were carried out using circular dichroism (CD) by measuring the ellipicity at 216 nm of a solution comprised of 17.5 μM p53-wt or p53tet-R337H and varying concentrations of GdnHCl in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 4.0, containing 50 mM sodium chloride. The concentration of GdnHCl was determined by refractive index measurements and using the following equation:

|

(1) |

where ΔN is the difference in refractive index between the denaturant solution and buffer at the sodium D line (Pace and Scholtz 1989).

Data for GdnHCl denaturation curves were collected at 25°C in 0.3 and 0.2 M increments for native p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H, respectively. Samples were allowed to equilibrate for 30 min. CD spectra were recorded using an AVIV model 62A DS circular dichroism spectropolarimeter using a 1-mm pathlength quartz cell. The reported spectra are an average of three scans.

Equilibrium data were analyzed as previously described by Mateu and coworkers (Mateu and Fersht 1998). The fraction of unfolded protein fU for any concentration of denaturant [D] was calculated from the corresponding experimental ellipicity value θ using the following equation (Pace 1986):

|

(2) |

where [D] is the concentration of denaturant, and θn0 and θu0 are the ellipicity values corresponding to the native (n) and denatured (u) states extrapolated to [D] = 0, and mn and mu are the slopes of the baselines preceding and following the transition region obtained by linear regression analysis.

Data for the fraction of unfolded protein, fu, were plotted as a function of GdnHCl concentration and fitted to a curve described by the following equation (Privalov 1979) using KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software):

|

(3) |

where m and [D]50% are the slope and the midpoint of the transition region. yn and yu are the intercepts and mn and mu are the slopes of the pre- and post-transition regions, respectively. Finally, R is the gas constant and T is the absolute temperature.

The free energy of unfolding, ΔGu, was calculated using the following equation (Mateu and Fersht 1998):

|

(4) |

where Pt is the total p53tet monomer concentration.

To calculate [D]50%, ΔGuH2O, and m, the ΔGu values obtained for [D] values within the transition region of the denaturation curve were used to fit the following equations:

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

To minimize errors due to extrapolation, the difference in free energy between the tetrameric wild type and mutant, Δ ΔGu, was calculated at a denaturant concentration of [D] = [D]50% for each protein (Jackson et al. 1993) using the following equation:

|

(7) |

where m and m′ are derived from equation 6 for the wild-type and mutant proteins, respectively, and Δ [D]50% is the difference in values between the two proteins.

Thioflavin T (ThT) assay

A solution of ThT was prepared at a concentration of 50 μM in double-distilled water and stored in the dark to prevent photo-reactions. To 200 μL of p53tet-wt or p53tet-R337H in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 6.0 containing 50 mM NaCl was added 50 μL of a solution containing 100 mM citric acid and 400 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 3.78. The pH was adjusted to 4.0 with 0.5 M HCl and the solution was incubated at 37°C in a water bath. Aliquots (20 μL) were taken at given time intervals and added to 0.5 mL of a solution containing 40 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 6.0, equilibrated at 4°C. Fibril content was determined by measuring the change in fluorescence intensity upon the addition of 0.5 mL of 50 μM ThT to a 1-cm pathlength cuvette using a Fluorolog-3 spectrofluorimeter (Jobin Yvon, Horiba). The excitation and emission wavelengths were 440 and 485 nm, respectively.

ThT fluorescence measurements were plotted as a function of time and fitted to a sigmoidal curve described by the following equation (Nielsen et al. 2001) using KaleidaGraph:

|

(8) |

where Y is the fluorescence intensity, x is the time, and x0 is the time to 50% of maximal fluorescence. The apparent rate constant for the growth of fibrils, kapp, is given by 1/τ, and the lag time is given by x0 − 2τ. yi and yf are the intercepts on the Y axis, and mi and mf are the slopes for the pre- and post-transition regions, respectively.

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

Protein samples for NMR spectroscopy consisted of 4.0 mM p53tet monomer in 10 mM sodium phosphate at pH 6.0, containing 50 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) 2H2O, and 0.02% (w/v) sodium azide. Where appropriate, the pH was adjusted from 6.0 to 4.0 with 0.5 M HCl prior to acquiring NMR spectra. 13C/15N-labeled p53tet samples were used to acquire transverse relaxation optimized spectroscopy (TROSY)-based triple resonance HNCA, HN(CO)CA, HNCACB, and CBCA(CO)NH spectra for assignment of backbone NH resonances. 3D 1H-15N TROSY-based NOESY spectra were used to confirm backbone assignments. Supplementary Figure 2 shows the backbone residue assignments for p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H at pH 6.0 and 4.0. The chemical shift values for p53tet-wt and p53tet-R337H at pH 4.0 have been deposited in the BioMagResBank database (http://www.bmrb.wisc.edu) under the accession numbers 6521 (p53tet-wt at pH 4.0 and 6.0) and 6522 (p53tet-R337H at pH 4.0 and 6.0).

15N-labeled p53tet-R337H fibril samples were prepared by incubation of 4.0 mM protein, prepared in 10 mM sodium phosphate at pH 6.0, containing 50 mM NaCl and adjusted to pH 4.0 with 0.5 M HCl, in a constant temperature water bath at 50°C for 3 d. Completion of fibril formation was determined by monitoring changes in 2D 1H-15N TROSY spectra with time until no further changes were apparent.

Steady-state {1H}-15N heteronuclear NOEs were determined from 2D TROSY spectra recorded with and without 1H pre-saturation. Spectra with presaturation were recorded with a prescan delay of 2 sec, followed by 3 sec of presaturation, and spectra without presaturation were recorded with a prescan delay of 5 sec. {1H}-15N heteronuclear NOE experiments were recorded with 64 transients for each t1 value.

All spectra were collected at 20°C on a Varian INOVA 600 spectrometer. Spectra were processed using NMRPipe software (Delaglio et al. 1995) and analyzed using FELIX software (Accelerys, Inc.). The 1H dimensions of spectra were referenced to external TSP and the 13C and 15N dimensions were referenced indirectly using the appropriate ratios of gyromagnetic ratios (Cavanagh et al. 1996). Secondary 13Cα chemical shift values (Δ δ13Cα) were calculated using random coil values compiled by Schwarzinger and coworkers (Schwarzinger et al. 2001).

H/D exchange experiments

Samples (0.5 mL) containing 4.0 mM p53tet-wt or p53tet-R337H in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 6.0, and 50 mM NaCl were lyophilized and stored in a desiccated container at −80°C. Prior to each H/D exchange experiment the lyophilized samples were dissolved in 500 μL of 10 mM citrate buffer at pH 3.46 containing varying amounts of GdnDCl in D2O at 4°C. The pD was adjusted to 4.0 with 0.5 M DCl (pD = pH* +0.4, where pH* is the uncorrected pH meter reading) and the solution was centrifuged to remove insoluble material before being placed into a 5 mm NMR tube. Initial spectra were recorded ~20–30 min after dissolving the sample in D2O. 2D 1H-15N TROSY spectra were acquired at given time intervals over a period of up to 3 d.

H/D exchange rates were determined by fitting the decay of resonance cross-peak volumes versus time to the single exponential function:

|

(9) |

where V(t) is the volume of the resonance cross-peak at time t and V0 is the amplitude of the exchange curve at zero time, kobs is the observed H/D exchange rate constant, t is the time in minutes, and c is the peak volume at infinite time of exchange.

Protection factors, which are a measure of the resistance of amide protons to exchange, were calculated using the following equation:

|

(10) |

where kintrinsic and kobs are the intrinsic and observed exchange rates, respectively. Intrinsic exchange rates, which are the rates of exchange for amides in an unstructured polypeptide at pH 4.0 and 20°C, were obtained using the program Sphere (Bai et al. 1993; Connelly et al. 1993) at http://www.fccc.edu/research/labs/roder/sphere/.

pH Titration studies

Samples containing 0.4 mM 15N-labeled p53tet-wt or p53tet-R337H were prepared in 10 mM sodium phosphate containing 50 mM NaCl, 10% D2O and 0.02% NaN3. The pH of the solution was adjusted by adding small aliquots of 0.5 M HCl or 0.5 M NaOH to avoid large localized changes in pH. The pH of the sample at room temperature was measured before and after data collection, and the average value was used for data analysis. The variation in these values was generally <0.05 pH unit. Values were not corrected for the isotope effect on the pH electrode because of the consistent cancellation of isotope effects on the pKa values of ionizable groups and on the electrode (Glasoe and Long 1960; Bunton and Shiner 1961).

3D 1H-15N NOESY spectra were collected over the pH range from 2.5 to 6.0 in increments of 0.5 pH unit, with a mixing time of 60 msec. NMR data were collected at a probe temperature of 20°C.

Titration data were fit to the Henderson-Hasselbach equation (Shrager et al. 1972) using KaleidaGraph,

|

(11) |

where δA and δB are the plateau values of proton chemical shifts in the acidic and basic pH limits, respectively.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC), St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (SJCRH) Pediatric Oncology Education Program (P.B.), The Rhodes College/St. Jude Summer Plus Program (P.B., sponsored by the Robert and Ruby Priddy Charitable Trust), National Cancer Institute (5R21CA104568 to R.W.K.), and a Cancer Center (CORE) Support Grant (CA21765, SJCRH). Donald Bashford is acknowledged for insightful discussion regarding p53tet salt bridges. Michael Stewart, Weixing Zhang, and Charles Ross are thanked for assistance with NMR experiments and computer support, respectively.

Abbreviations

H/D exchange, hydrogen-deuterium exchange

p53tet, p53 tetramerization domain

p53tet-wt, wild-type p53 tetramerization domain

p53tet-R337H, p53 tetramerization domain mutant R337H

NOE, nuclear Overhauser effect

NOESY, nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy

TROSY, transverse relaxation optimized spectroscopy

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.051622005.

Supplemental material: see www.proteinscience.org

References

- Armstrong, K.M. and Baldwin, R.L. 1993. Charged histidine affects alpha-helix stability at all positions in the helix by interacting with the backbone charges. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 90 11337–11340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y., Milne, J.S., Mayne, L., and Englander, S.W. 1993. Primary structure effects on peptide group hydrogen exchange. Proteins 17 75–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y., Sosnick, T.R., Mayne, L., and Englander, S.W. 1995. Protein folding intermediates: Native-state hydrogen exchange. Science 269 192–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth, D.R., Sunde, M., Bellotti, V., Robinson, C.V., Hutchinson, W.L., Fraser, P.E., Hawkins, P.N., Dobson, C.M., Radford, S.E., Blake, C.C., et al. 1997. Instability, unfolding and aggregation of human lysozyme variants underlying amyloid fibrillogenesis. Nature 385 787–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosshard, H.R., Marti, D.N., and Jelesarov, I. 2004. Protein stabilization by salt bridges: Concepts, experimental approaches and clarification of some misunderstandings. J. Mol. Recognit. 17 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunton, C.A. and Shiner Jr., V.J. 1961. Isotope effects in deuterium oxide solution. I. Acid-base equilibria. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 83 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh, J., Fairbrother, W.J., Palmer III, A.G., and Skelton, N.J. 1996. Protein NMR spectroscopy. Academic Press, New York.

- Chene, P. 2001. The role of tetramerization in p53 function. Oncogene 20 2611–2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiti, F., Webster, P., Taddei, N., Clark, A., Stefani, M., Ramponi, G., and Dobson, C.M. 1999. Designing conditions for in vitro formation of amyloid protofilaments and fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96 3590–3594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clore, G.M., Ernst, J., Clubb, R., Omichinski, J.G., Kennedy, W.M., Sakaguchi, K., Appella, E., and Gronenborn, A.M. 1995. Refined solution structure of the oligomerization domain of the tumour suppressor p53. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2 321–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clubb, R.T., Omichinski, J.G., Sakaguchi, K., Appella, E., Gronenborn, A.M., and Clore, G.M. 1995. Backbone dynamics of the oligomerization domain of p53 determined from 15N NMR relaxation measurements. Protein Sci. 4 855–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran, D.A. and Doig, A.J. 2001. Effect of the N2 residue on the stability of the α-helix for all 20 amino acids. Protein Sci. 10 1305–1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran, D.A., Penel, S., and Doig, A.J. 2001. Effect of the N1 residue on the stability of the α-helix for all 20 amino acids. Protein Sci. 10 463–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conaway, J.W., Kamura, T., and Conaway, R.C. 1998. The elongin BC complex and the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1377 M46–M54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly, G.P., Bai, Y., Jeng, M.F., and Englander, S.W. 1993. Isotope effects in peptide group hydrogen exchange. Proteins 17 87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison, T.S., Yin, P., Nie, E., Kay, C., and Arrowsmith, C.H. 1998. Characterization of the oligomerization defects of two p53 mutants found in families with Li-Fraumeni and Li-Fraumeni-like syndrome. Oncogene 17 651–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison, T.S., Nie, X., Ma, W., Lin, Y., Kay, C., Benchimol, S., and Arrowsmith, C.H. 2001. Structure and functionality of a designed p53 dimer. J. Mol. Biol. 307 605–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaglio, F., Grzesiek, S., Vuister, G.W., Zhu, G., Pfeifer, J., and Bax, A. 1995. NMRPipe: A multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6 277–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGiammarino, E.L., Lee, A.S., Cadwell, C., Zhang, W., Bothner, B., Ribeiro, R.C., Zambetti, G., and Kriwacki, R.W. 2002. A novel mechanism of tumorigenesis involving pH-dependent destabilization of a mutant p53 tetramer. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9 12–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fandrich, M., Forge, V., Buder, K., Kittler, M., Dobson, C.M., and Diekmann, S. 2003. Myoglobin forms amyloid fibrils by association of unfolded polypeptide segments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100 15463–15468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraczkiewicz, R. and Braun, W. 1998. Exact and efficient analytical calculation of the accessible surface areas and their gradients for macromolecules. J. Comput. Chem. 19 319–333. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, S.C. and von Hippel, P.H. 1989. Calculation of protein extinction coefficients from amino acid sequence data. Anal. Biochem. 182 319–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasoe, P.K. and Long, F.A. 1960. Use of glass electrodes to measure acidities in deuterium oxide. J. Phys. Chem. 64 188–190. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbalsyah, T.M. and Doig, A.J. 2004. Effect of the N3 residue on the stability of the α-helix. Protein Sci. 13 32–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru, D., Andrade, L.R., Teixeira, L.S., Quesado, P.A., Maiolino, L.M., Lopez, P.M., Cordeiro, Y., Costa, L.T., Heckl, W.M., Weissmuller, G., et al. 2003. Fibrillar aggregates of the tumor suppressor p53 core domain. Biochemistry 42 9022–9027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, S.E., Moracci, M., elMasry, N., Johnson, C.M., and Fersht, A.R. 1993. Effect of cavity-creating mutations in the hydrophobic core of chymotrypsin inhibitor 2. Biochemistry 32 11259–11269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey, P.D., Gorina, S., and Pavletich, N.P. 1995. Crystal structure of the tetramerization domain of the p53 tumor suppressor at 1.7 Å. Science 267 1498–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, C.R., Morin, P.E., Arrowsmith, C.H., and Freire, E. 1995. Thermodynamic analysis of the structural stability of the tetrameric oligomerization domain of p53 tumor suppressor. Biochemistry 34 5309–5316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, J.W. 1997. Amyloid fibril formation and protein misassembly: A structural quest for insights into amyloid and prion diseases. Structure 5 595–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S. and Nussinov, R. 2002a. Close-range electrostatic interactions in proteins. Chembiochemistry 3 604–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2002b. Relationship between ion pair geometries and electrostatic strengths in proteins. Biophys. J. 83 1595–1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W., Harvey, T.S., Yin, Y., Yau, P., Litchfield, D., and Arrowsmith, C.H. 1994. Solution structure of the tetrameric minimum transforming domain of p53. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1 877–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, A.S., Galea, C., DiGiammarino, E.L., Jun, B., Murti, G., Ribeiro, R.C., Zambetti, G., Schultz, C.P., and Kriwacki, R.W. 2003. Reversible amyloid formation by the p53 tetramerization domain and a cancer-associated mutant. J. Mol. Biol. 327 699–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomax, M.E., Barnes, D.M., Hupp, T.R., Picksley, S.M., and Camplejohn, R.S. 1998. Characterization of p53 oligomerization domain mutations isolated from Li-Fraumeni and Li-Fraumeni like family members. Oncogene 17 643–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateu, M.G. and Fersht, A.R. 1998. Nine hydrophobic side chains are key determinants of the thermodynamic stability and oligomerization status of tumour suppressor p53 tetramerization domain. EMBO J. 17 2748–2758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1999. Mutually compensatory mutations during evolution of the tetramerization domain of tumor suppressor p53 lead to impaired heterooligomerization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96 3595–3599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateu, M.G., Sanchez Del Pino, M.M., and Fersht, A.R. 1999. Mechanism of folding and assembly of a small tetrameric protein domain from tumor suppressor p53. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6 191–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy, M., Stavridi, E.S., Waterman, J.L.F., Wieczorek, A.M., Opella, S.J., and Halazonetis, T. 1997. Hydrophobic side-chain size is a determinant of the three-dimensional structure of the p53 oligomerization domain. EMBO J. 16 6230–6236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neidhardt, F.C., Bloch, P.L., and Smith, D.F. 1974. Culture medium for enterobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 119 736–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neira, J.L. and Mateu, M.G. 2001. Hydrogen exchange of the tetramerization domain of the human tumour suppressor p53 probed by denaturants and temperature. Eur. J. Biochem. 268 4868–4877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, L., Khurana, R., Coats, A., Frokjaer, S., Brange, J., Vyas, S., Uversky, V.N., and Fink, A.L. 2001. Effect of environmental factors on the kinetics of insulin fibril formation: Elucidation of the molecular mechanism. Biochemistry 40 6036–6046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noolandi, J., Davison, T.S., Volkel, A.R., Nie, X., Kay, C., and Arrow-smith, C.H. 2000. A meanfield approach to the thermodynamics of a protein–solvent system with application to the oligomerization of the tumor suppressor p53. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97 9955–9960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace, C.N. 1986. Determination and analysis of urea and guanidine hydrochloride denaturation curves. Methods Enzymol. 131 266–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace, C.N. and Scholtz, J.M. 1989. Measuring the conformational stability of a protein. In Protein structure: A practical approach, 2nd ed. (ed. T.E. Creighton), pp. 299–321. IRL Press, New York.

- Privalov, P.L. 1979. Stability of proteins: Small globular proteins. Adv. Protein Chem. 33 167–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Alvarado, M., Merkel, J.S., and Regan, L. 2000. A systematic exploration of the influence of the protein stability on amyloid fibril formation in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97 8979–8984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratnaswamy, G., Koepf, E., Bekele, H., Yin, H., and Kelly, J.W. 1999. The amyloidogenicity of gelsolin is controlled by proteolysis and pH. Chem. Biol. 6 293–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, R.C., Sandrini, F., Figueiredo, B., Zambetti, G.P., Michalkiewicz, E., Lafferty, A.R., DeLacerda, L., Rabin, M., Cadwell, C., Sampaio, G., et al. 2001. An inherited p53 mutation that contributes in a tissue-specific manner to pediatric adrenal cortical carcinoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98 9330–9335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochet, J.C. and Lansbury Jr., P.T. 2000. Amyloid fibrillogenesis: Themes and variations. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 10 60–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roher, A.E., Baudry, J., Chaney, M.O., Kuo, Y.M., Stine, W.B., and Emmerling, M.R. 2000. Oligomerizaiton and fibril asssembly of the amyloid-β protein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1502 31–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzinger, S., Kroon, G.J.A., Foss, T.R., Chung, J., Wright, P.E., and Dyson, H.J. 2001. Sequence-dependent correction of random coil NMR chemical shifts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123 2970–2978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe, D.J. 1994. Normal and abnormal biology of the beta-amyloid precursor protein. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 17 489–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortle, D.R. 1996. Structural analysis of non-native states of proteins by NMR methods. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 6 24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrager, R.I., Cohen, J.S., Heller, S.R., Sachs, D.H., and Schechter, A.N. 1972. Mathematical models for interacting groups in nuclear magnetic resonance titration curves. Biochemistry 11 541–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefani, M. and Dobson, C.M. 2003. Protein aggregation and aggregate toxicity: New insights into protein folding, misfolding diseases and biological evolution. J. Mol. Med. 81 678–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stürzbecher, H.W., Brain, R., Addison, C., Rudge, K., Remm, M., Grimaldi, M., Keenan, E., and Jenkins, J.R. 1992. A C-terminal α-helix plus basic region motif is the major structural determinant of p53 tetramerization. Oncogene 7 1513–1523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunde, M. and Blake, C. 1997. The structure of amyloid fibrils by electron microscopy and X-ray diffraction. Adv. Protein Chem. 50 123–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunde, M., Serpell, L.C., Bartlam, M., Fraser, P.E., Pepys, M.B., and Blake, C.C. 1997. Common core structure of amyloid fibrils by synchrotron X-ray diffraction. J. Mol. Biol. 273 729–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanford, C. 1962. The interpretation of hydrogen ion titration curves of proteins. Adv. Protein Chem. 17 69–165. [Google Scholar]

- Uversky, V.N. and Fink, A.L. 2004. Conformational constraints for amyloid fibrillation: The importance of being unfolded. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1698 131–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wüthrich, K. 1994. NMR assignments as a basis for structural characterization of denatured states of globular proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 4 93–99. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Y. and Higuchi, K. 2002. Amyloid fibril proteins. Mech. Ageing Dev. 123 1625–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]