Abstract

Folding and stability of proteins containing ankyrin repeats (ARs) is of great interest because they mediate numerous protein–protein interactions involved in a wide range of regulatory cellular processes. Notch, an ankyrin domain containing protein, signals by converting a transcriptional repression complex into an activation complex. The Notch ANK domain is essential for Notch function and contains seven ARs. Here, we present the 2.2 Å crystal structure of ARs 4–7 from mouse Notch 1 (m1ANK). These C-terminal repeats were resistant to degradation during crystallization, and their secondary and tertiary structures are maintained in the absence of repeats 1–3. The crystallized fragment adopts a typical ankyrin fold including the poorly conserved seventh AR, as seen in the Drosophila Notch ANK domain (dANK). The structural preservation and stability of the C-terminal repeats shed a new light onto the mechanism of hetero-oligomeric assembly during Notch-mediated transcriptional activation.

Keywords: ankyrin repeats, Notch, crystal structure

The conserved Notch signaling pathway mediates cell-fate decisions during multiple stages of development in multicellular eukaryotes. In adult organisms, Notch signaling is involved in tissue regeneration, and disruptions in this pathway contribute to several diseases including cancer, stroke, and multiple sclerosis (for review, see Bray 1998; Artavanis-Tsakonas et al. 1999; Gridley 2003; Radtke and Raj 2003). Notch receptors are single pass transmembrane proteins activated by ligand binding which trigger two consecutive proteolytic events. These result in the release of the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) that translocates to the nucleus where it interacts with the DNA binding protein CSL (CBP/RBPjk in Mus musculus, Su(H) in Drosophila, Lag-1 in Caenorhabditis elegans) (for review, see Lubman et al. 2004; Schweisguth 2004) (Fig. 1A ▶). Formation of the NICD/CSL complex is a prerequisite for binding Mastermind (MAM)/Lag-3 protein (Petcherski and Kimble 2000). The resulting complex recruits histone acetyltransferases (HAT) to assemble the active transcription complex. NICD is comprised of N-terminal RAM domain (RBPjk associated molecule), followed by seven ARs and a C-terminal PEST and OPA domains (Fig. 1A ▶). NICD/CSL interaction is mediated mainly through the unstructured RAM domain (Tamura et al. 1995; Nam et al. 2003). The ANK domain also contributes to this interaction (Tamura et al. 1995; Tani et al. 2001) and is absolutely essential for MAM recruitment into the NICD/CSL complex (Fryer et al. 2002; Nam et al. 2003). ANK was also proposed to interact with the HAT complex (Kao et al. 1998; Oswald et al. 2001; Fryer et al. 2002). Destabilization of the ANK domain with mutations or deletions abrogates Notch signaling, indicating its key role in Notch function (for review, see Lubman et al. 2004; Schweisguth 2004).

Figure 1.

(A) Simplified schematic diagram of the Notch-mediated transcriptional “switch.” NICD is composed of a membrane proximal RAM domain (yellow), seven ARs (red), and C-terminal PEST, OPA domains (navy). Binding of NICD to CSL displaces transcriptional repressors (SMRT, HDAC, CIR) and leads to recruitment of transcriptional activators MAM and HAT. (B) A 2.2 Å crystal structure of mouse Notch1 ARs 3β–7. There are two molecules in the asymmetric unit of the crystal. Repeats 3β–7 of molecule A are colored red, yellow, green, brown, and cyan, respectively. Repeats of molecule B are colored gray. (C) Structural overlay of partial ANK domain of mouse Notch-1 with ARs is color coded as in B and the dANK domain of the Drosophila Notch receptor is shown in a gray transparent worm representation.

At least four Notch homologs exist in vertebrate species. They all are activated in a similar manner (Mizutani et al. 2001; Saxena et al. 2001) and interact with the CSL protein (Kato et al. 1996), but they differ in their ability to activate target genes. For example, Notch 1 and Notch 2 act as activators of HES transcription (Hairy-Enhancer of split encoding genes) among which HES-1, HES-5, and HES-7 are known targets of the Notch receptor. In contrast, Notch 3 is a poor HES activator and, when overexpressed, is able to compete-out Notch 1, thus abrogating HES-1 activation (Beatus et al. 1999). These differences between Notch 1 and Notch 3 were mapped to their respective ANK domains (Beatus et al. 2001).

Precisely how NICD modulates nuclear processes and how its ANK domain contributes to this activity has been one of the most challenging problems in Notch biology, and is now just beginning to be addressed through initial structural and biophysical studies. The proteins containing AR modules have been found in organisms ranging from viruses to humans (Bork 1993), performing a variety of biological functions. Generally, they mediate protein–protein interactions in very diverse families of proteins, and were also found in heat and mechanosensitive receptors (Liedtke et al. 2000). AR is composed of 33 residues that form two anti-parallel α-helices followed by a β-hairpin. The repeats stack against each other and form an extended, elongated structure. Fourteen structures of AR domains from naturally occurring proteins with different cellular functions or artificially designed have been solved to date (for review, see Mosavi et al. 2004). All structures, whether alone or in complex with protein partners, are remarkably similar in the conformation of individual repeats and in the packing of repeats against each other. Functionally diverse yet structurally similar, AR-containing proteins present a challenge in understanding the molecular mechanism of their interactions. Structural studies identified a common binding interface mapped to either the tips of β-hairpin loops or the baseball glove–like concave inner surface formed by the β-hairpins and inner helices (Fig. 1B ▶) (for review, see Mosavi et al. 2004). At the same time, analysis of numerous cancer-related mutations of human p16, four ARs containing protein, revealed that the residues located far away from the interaction interface can alter AR binding by affecting their thermodynamic stability and folding properties (Zhang and Peng 1996).

Stability and folding properties of Drosophila Notch ANK domain (dANK) were studied to further understand the mechanism of ANK binding in general and NICD transcriptional activation in particular (Zweifel and Barrick 2001a,b). It was shown that folding of dANK follows a two-state folding pathway similar to globular proteins, where each part of the structure contributes to the overall stability. Equilibrium folding experiments and the crystal structure of dANK showed that a region previously shown to be critical for mediating transcriptional activation is, in fact, the seventh ankyrin repeat of the NICD, deletion of which reduced ANK’s folding free energy by 3.5 kcal/mol (Zweifel and Barrick 2001a; Zweifel et al. 2003). Studies on folding properties of dANK mutants led Bradley and Barrick (2002) to propose a model that divides dANK into two thermodynamically distinguishable N-terminal (repeats 2–5) and C-terminal (repeats 6 and 7) subdomains. Unequal contribution of individual repeats to the overall stability of the Notch ANK domain may have direct implications for Notch-mediated transcription activation.

In the context of our efforts directed at understanding Notch-mediated transcriptional control, we attempted to crystallize a truncated form of mouse Notch1 NICD, composed of the RAM and ANK domains. Here, we present a 2.2 Å crystal structure of a stable proteolytic fragment encompassing a β-hairpin of the AR 3 (referred to hereafter as 3β) and ARs 4–7. The structure confirms that the seventh AR adapts an ankyrin fold in mouse Notch 1, and demonstrates that C-terminal repeats are more resistant to degradation than the RAM domain and the N-terminal ARs. Repeats 4–7 alone form a stable soluble fragment with a fully preserved ankyrin repeat fold including the 3β. A sequence comparison of the ANK domains from the four vertebrate Notch orthologs led to the observation that, in addition to the canonical ankyrin protein–binding interface, the Notch ANK domain may have a paralog-specific site for protein binding. Highly conserved “signature” residues that define the shape and stability of ARs also vary among the four Notch homologs. Thus, we suggest that the stability of Notch ANK domains and/or individual repeats is likely to contribute in their functional diversity.

Results

Proteolytic degradation and stability of mouse Notch 1 partial ANK domain (m1ANK)

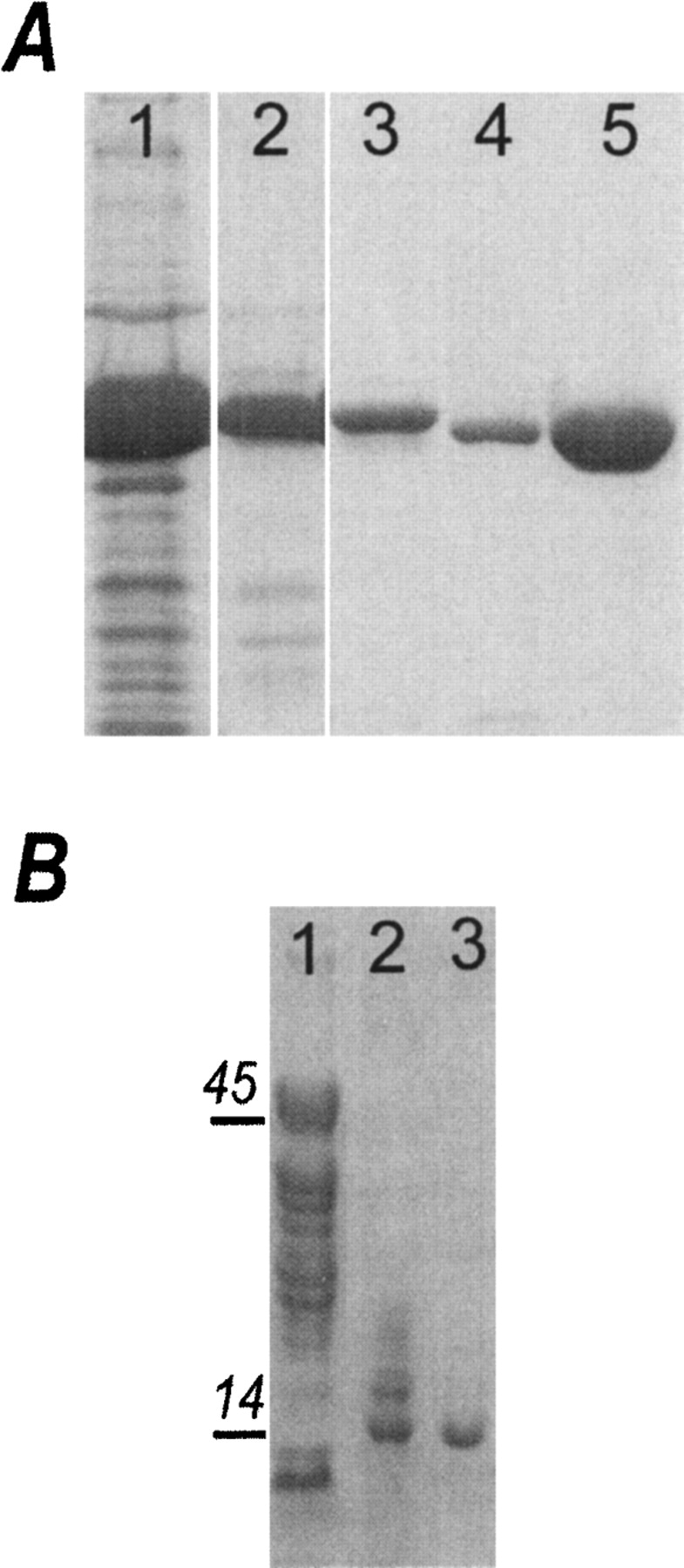

We have attempted to crystallize a truncated form of the Notch-1 intracellular domain that had both RAM and ANK domains (RAM-ANK). A four-step purification procedure yielded a 98% pure RAM-ANK based on SDS PAGE analysis (Fig. 2A ▶). Crystals of the protein appeared reproducibly in 7 to 10 d. Unit cell parameters of crystals were in obvious discrepancy with the molecular weight of the expressed fragment. SDS PAGE analysis of a dissolved crystal revealed a 14 kDa fragment, much smaller than the predicted size of the cloned protein (Fig. 2B ▶). N-terminal sequencing identified the residues NRATD, which map to the beginning of a β-turn region within the third ankyrin repeat from mouse Notch 1. Coupled with mass spectrometry analysis, we determined that the crystallized fragment contains ARs 4–7. SDS PAGE analysis of samples removed from the crystallization drop after 2 d and 7 d revealed that proteolysis started gradually, producing numerous intermediates (Fig. 2B ▶, lane 1). The crystallized fragment did not appear among the initial proteolytic intermediates. After 7 d (at the time the first crystals appear), only two cleavage products remained, with the smaller one forming crystals (Fig. 2B ▶, lanes 2,3). Moreover, after 6 mo at room temperature, this fragment was the only one found in crystallization drops, even though crystals were not viable for such extended periods of time. We have not noticed proteolysis during storage of the purified RAM-ANK fragment kept at the concentration of 1 mg/mL at 4°C for more than a month. While the origin of degradation is unknown, a subdomain containing ARs 4–7 was stable while the N terminus was not.

Figure 2.

SDS PAGE analysis of RAMANK during purification and crystallization. (A) Four-step chromatography purification of the RAMANK protein: lane 1, Talon column; lane 2, Q Sepharose; lane 3, gel filtration; lane 4, TEV cleavage; lane 5, second Talon column. (B) Samples taken from crystallization drop on the second day of crystallization (lane 1), and after 7 d in the crystallization drop (lane 2). Dissolved crystals contained only a 14.4 kDa band (lane 3).

Partial m1ANK—overall fold

There are two molecules in the asymmetric unit of the crystal. The individual ARs form an elongated array of anti-parallel α-helices, and the overall fold of this partial m1ANK domain is that of a typical AR-containing protein (Fig. 1B ▶). Furthermore, the seventh AR of the mouse Notch adapts an ankyrin fold as does its Drosophila counterpart. Surprisingly, the conformation of the β-hairpin loop that connects repeats 3 and 4 (3β) is not perturbed by proteolysis and preserves a β-turn fold. Both molecules are very similar and superimpose with an average pairwise root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of 0.16 Å over 133 Cα atoms. No electron density was observed for the side chains of Glu 131, His141, Leu 170, Tyr 197, Ile 232, and Arg 234 of both molecules. Residues 107–114, corresponding to the most N-terminal region of each molecule, showed less structural similarity.

Comparison of the dANK structure with that of m1ANK indicates that ARs 4–7 superimpose with the average RMSD of 0.5 Å, over 128 Cα atoms of the three molecules of dANK in the asymmetric unit (Zweifel et al. 2003; PDB code 1OT8) (Fig. 1C ▶). The most substantial differences are in the conformation of repeat 4, which may be a consequence of the involvement of this repeat in dimerization (see below). Other differences between the dANK and m1ANK structures correlate with regions of low sequence homology, predominantly β-hairpin loops that connect adjacent ARs and the loops that connect two helices of the same repeat.

Two molecules in the asymmetric unit are related to each other by a noncrystallographic two-fold axis that runs perpendicular to the long axes of each polypeptide. As a result, the N termini of both molecules are facing each other, generating a rod-shaped structure reminiscent of one multire-peat ankyrin polypeptide. This interface buries 1239 Å2 of total surface area and includes water-mediated hydrogen bonds and extensive hydrophobic interactions. Water-mediated main-chain hydrogen bond interactions are localized to the dimer interface, mediated by 3β. Another area of contact is the loop region connecting the helices of AR 4. Importantly, the hydrophobic core of the dimer interface forms an extension of the central hydrophobic core formed by the conserved residues at the α-helices/β-hairpin junctions that extends through all repeats.

Comparison of ANK domains from four mouse Notch paralogs

We conducted a sequence comparison of the four vertebrate Notch paralogs to get further insight into the role of individual ARs in Notch signaling. Individual Notch orthologs are highly conserved among vertebrate species (more than 95% sequence identity between mouse and human ANK domains). Sequence homology between the ANK domains of Notch paralogs is significantly lower. For example, mouse Notch-1 ANK (m1ANK) shows 77%, 76%, and 52% of sequence identity when compared to Notch-2 ANK (m2ANK), Notch-3 (m3ANK), and Notch-4 (m4ANK), respectively (Fig. 3A ▶). Variable residues between the Notch paralogs can be divided into two groups: buried residues, which belong to highly conserved “signature” motifs (TPLH motifs located in the beginning of the inner helix of each AR), and residues with predominantly surface-exposed side chains. Substitutions of buried residues, such as Pro to Ala substitution in the TPLH motif, are predicted to retain a secondary structure but affect stability of the entire ANK domain and individual repeats (Fig. 3A ▶, outlined in the red box). An example of such substitution is found in the AR 4 of m3ANK, and a reverse substitution is found in the second AR of m4ANK (Fig. 3A ▶). Changes in stability may alter selectively the affinity of Notch paralogs toward common protein partners or affect their turnover rate, which is higher for less stable proteins.

Figure 3.

Sequence conservation among four Notch homologs in the mouse. (A) Structure-based sequence alignment of ARs 2–7 of mouse Notch1, Notch2, Notch3, and Notch4. Conserved, semiconserved, and nonconserved residues are colored green, yellow, and white, respectively. Secondary structure elements corresponding to inner and outer helices of each AR are colored red and blue, respectively. The figure was generated using the program ALSCRIPT (Barton 1993). (B) Sequence conservation mapped onto the molecular surface of the mouse Notch-1 ANK domain. Repeats 2 and 3 were modeled from the crystal structure of the dANK domain (Zweifel et al. 2003). The color scheme is identical to A. Orientation of panel 1 is illustrated by a ribbon diagram of the individual AR where the tips of the β-hairpin loops and inner helices are looking at the reader. Panel 2 is a 180° rotation along the Y axis, representing the molecular surface of the outer helices of ARs. The figure was generated using the program GRASP (Nicholls et al. 1991).

Analysis of surface-exposed residues showed low variability of side chains in a shallow grove formed by the inner helices and the β-hairpins, reflecting the fact that this region interacts with the common interaction partner CSL (Fig. 3A,B ▶: conserved residues of inner helices are in green while the variable residues are in yellow and white). Variable residues are clustered in two regions: one formed by the tip of the β-hairpin (Fig. 3A ▶, outlined in the black box) and another formed by the outer helices (Fig. 3A,B ▶). The molecular surface formed by the ANK domain β-hairpin residues represents a previously documented protein-binding interface for AR-containing proteins. However, residues in the outer helices vary among the four Notch paralogs but are conserved among orthologs. For example, all Notch 2 proteins have alanine (Ala 135) (Fig. 3A ▶, black arrow) in the outer helix of the AR 4, while Notch 1, Notch 3, and Notch 4, as well as Notch proteins from D. melanogaster, Xenopus laevis, and C. elegans all have glutamic acid at that position. Other paralog-specific substitutions reverse the charge of polar side chains. For example, aspartic acid (position 165) at the beginning of outer helix 5 of Notch 1 is changed to arginine in Notch 4 (Fig. 3A ▶, black arrow). The surface formed by the outer helices is located on the opposite side of the β-hairpin tips and baseball glove-like concave interface. Conserved in Notch orthologs, but variable in paralogs, this surface may represent a novel AR protein binding interface, potentially explaining interactions of Notch ANK domain with more than one protein partner.

Discussion

Through extensive biophysical analysis, molecular recognition by AR-containing proteins has been intimately linked to their intrinsic stabilities and folding mechanism. Individual ARs stack against each other via short-range intra-repeat interactions and form a domain. Despite different stabilities among individual repeats, the ANK domain (a multirepeat assembly) behaves like a globular protein and follows a two-state folding pathway (Tang et al. 1999; Zweifel and Barrick 2001b; Mosavi et al. 2002). Therefore, the modular architecture of the ANK domain does not preclude long-range communication among spatially distant repeats. Such unique structural arrangement permits different repeats within the ANK domain to perform distinct functions. For example, limited proteolysis coupled with deletion studies of the human cell cycle inhibitor p16, a four Ars-containing protein, showed that while the C-terminal repeats 3 and 4 could fold independently, the N-terminal repeats 1 and 2 were less stable and could only fold in the presence of repeats 3 and 4 (Zhang and Peng 2002). Importantly, direct interactions with protein partners were mapped to the less stable N-terminal repeats 1 and 2. Therefore, within the ANK domain of p16, two distinct roles for ARs were suggested: The inherent flexibility of N terminal ARs may be beneficial for optimal protein–protein interactions, while the inherent rigidity of C-terminal ARs is important for structural integrity of the entire p16 ANK domain (Zhang and Peng 2002; Tang et al. 2003). In support of this hypothesis, a number of cancer-related mutants were localized to the C-terminal repeats of p16 (Yarbrough et al. 1999); instead of directly interfering with the ability of p16 to interact with its binding partners, these mutants reduced the overall stability of the p16 ANK domain (Zhang and Peng 1996, 2002; Tang et al. 1999; Cammett et al. 2003). These mutants are also characterized by a propensity to form higher order oligomers and greater susceptibility to proteolysis (Tevelev et al. 1996; Zhang and Peng 2002). The crystal structure of another ARs-containing protein, IκB, in complex with its binding partner, transcription factor NF-κB, shows that the six ARs of IκB do not form a continuous binding interface for NF-κB, but rather, interact with different domains of NF-κB (Jacobs and Harrison 1998). Biophysical studies on ANK domain of IκB confirmed that stability properties among six ARs of IκB are also different (Croy et al. 2004). Differences in stability of individual ARs of IκB were correlated with distinct functional roles of the IκB ANK domain during NF-κB recognition. Here, the more stable ARs of IκB interact with the flexible NLS domain of NF-κB, while the less stable ARs of IκB interact with the well-ordered dimerization domain of NF-κB (Huxford et al. 1998; Jacobs and Harrison 1998).

Characterization of Notch ARs is essential for understanding how the Notch ANK domain interacts with multiple protein partners to mediate transcriptional activation. The contributions of individual AR to dANK folding and stability were studied through the effect of ALA to GLY substitutions in each AR (Bradley and Barrick 2002). Mutations in repeat 2–5 did not alter the cooperative unfolding of dANK; however, similar mutation in AR 6 caused multistep unfolding. These observations prompted Bradley and Barrick to propose that, like p16 and IκB, two subdomain divisions exist in dANK: One subdomain is formed by repeats 2–5, and another, by repeats 6 and 7 (Bradley and Barrick 2002). However, the ability of each subdomain to maintain tertiary structure was not evaluated.

The crystal structure presented here provides direct evidence that mNotch ARs 4–7 can form a stable structure and preserve ankyrin fold in the absence of ARs 1–3. With the exception of artificially designed ANK domains, secondary and tertiary structures of partial ANK domains (N- or C-terminal deletions) were indirectly inferred from solution studies using far-UV CD spectroscopy (Mello and Barrick 2004) and resistance to proteolysis (Tevelev et al. 1996; Zhang and Peng 2002; Mello and Barrick 2004). Our structure presents the first example of a partial ANK domain, whose structural integrity was confirmed by X-ray crystallography. Moreover, this domain was resistant to degradation, while RAM and the N-terminal ARs were not.

Initially, the possibility that the seventh AR of Notch would assume an ankyrin fold was dismissed due to the lack of TPLH motif in its primary sequence. Structural studies unambiguously demonstrated that the seventh AR in dANK indeed assumes an ankyrin fold, and biophysical studies, carried out by the same group, demonstrated that its deletion increased the equilibrium constant for folding of dANK by 1000-fold (Zweifel and Barrick 2001b; Zweifel et al. 2003). In contrast, the first AR (which contains the TPLH motif) did not adopt an ankyrin fold in the dANK structure, undermining the power of sequence-based structure prediction of terminal ARs. Our structure confirms the existence of the seventh AR in mNotch1, suggesting that Notch proteins across the species are likely to share seven and not six ARs as previously identified.

Deletion mutagenesis studies have mapped the interaction of CSL with NICD to the most membrane proximal, the unstructured RAM domain, with the ANK domain being the secondary binding site (Tamura et al. 1995; Tani et al. 2001). The region of the ANK domain likely to be contributing to CSL interaction is in the N-terminal ARs, as they are in spatial proximity to RAM. Thus, the sensitivity to proteolysis of the RAM and N-terminal ARs may diminish upon CSL binding. Following NICD/CSL interaction, recruitment of the transcriptional activator MAM was shown to require the fourth and the seventh AR of Notch (Petcherski and Kimble 2000; Jeffries et al. 2002). The C-terminal ARs may thus form an additional stable structural element necessary for MAM binding to the CSL/NICD complex. Indeed, MAM may be unstructured in solution (Nam et al. 2003), but adapt an ordered stable conformation upon binding the rigid CSL/NICD scaffold, similarly to cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk) inhibitor p21Waf1/Cip1/Sdi1 binding to Cdk2 (Kriwacki et al. 1996).

The importance of stability is further supported by the sequence comparison of four mammalian Notch paralogs. Mutations in the conserved ANK signature residues identified in the four paralogs could indicate that the stability of their respective ANK domains differs. For example, the “TPLH” motif in AR4 of m3ANK is replaced by the “TALI” sequence, while the AR4 of m1ANK has preserved the second Pro (TPLI) at that position. These subtle differences in signature motifs might be responsible for the inability of Notch3 to activate the HES-1 promoter (Beatus et al. 2001). This, in turn, may impact the affinity of Notch (1–4) toward CSL or MAM and contribute to their functional differences. Sequence alignment suggests the presence of an additional putative binding interface formed by the variable residues of the outer helices. It is located opposite to the tips of β-hairpin and inner helices, providing a possible explanation of how Notch can make simultaneous interactions with numerous protein partners (CSL, MAM, HAT, SKIP) (Tamura et al. 1995; Zhou et al. 2000; Oswald et al. 2001; Zhou and Hayward 2001; Fryer et al. 2002). The differences in these variable regions may account either for different affinity toward the same protein partners, or the ability to interact with different proteins. The ARs of the Notch receptor stand at the core of a multiprotein assembly is required for Notch-mediated transcriptional activation. Multidomain organization of ARs, together with several putative binding sites identified through structure-based sequence analysis of four Notch paralogs, help explain the mechanism of ANK domain-mediated interactions with different protein partners. Known stability and structural properties of Notch ARs should be taken into account when discerning their biological function through mutagenesis and deletion analysis.

Materials and methods

Cloning

A fragment of the mouse Notch-1 protein encoding the RAM domain and seven putative ankyrin repeats was amplified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from a plasmid containing cloned full-length mouse Notch-1 cDNA. Primers were designed to amplify DNA encoding residues 1781–2221 (RAMANK). PCR product was digested with BamH1 and HindIII restriction enzymes, gel purified and ligated into Invitrogen pProEX HTc prokaryotic plasmid, and expressed as N-terminal, with TEV protease cleavage site His-tagged protein under control of T7 promoter.

Expression and purification of Notch 1(RAM-ANK)

The Escherichia coli strain BL21*(DE3) was transformed with a pPro-RAMANK construct and a single colony was used to inoculate 100 mL of starter culture supplemented with 0.1 mg/mL of ampicillin. Ten milliliters of overnight culture was used to inoculate 1 L of LB. Cells were grown to OD600 ~ 0.7–0.8 and induced with 1 mM IPTG for 4 h at 37°C. Bacteria were collected by centrifugation and cell pellets were resuspended in 50 mL of lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 10% Glycerol, 5 mM BME, EDTA-free protease inhibitor tablet (Roche Biosciences). Cell lysate was placed at −80°C for at least an hour or until next purification. PMSF (1 mM) was added to the thawed cell lysate, followed by extensive sonication on ice. Lysed cells were centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 30 min and the supernatant was loaded onto a Talon column (Invitrogen) pre-equilibrated with lysis buffer. Protein was eluted with step gradient 0–0.5 M of imidazole. The fractions containing Notch RAMANK were pooled and loaded onto a Hi-Trep Q column (Amersham) and eluted with linear gradient of 150 mM to 1 M NaCl. Material was pooled, digested with TEV protease for 4 h at room temperature, and dialyzed extensively against buffer containing 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, and 5 mM βME. The His-tag, along with TEV protease, were removed by passing the digested material over Talon column and collecting the flow through fraction. Gel filtration chromatography was performed as a final purification step, and protein purity was analyzed using SDS-PAGE gel (Fig. 2 ▶). The final yield from 1 L of culture was 13–15 mg of protein.

Crystallization and data collection

Initial crystallization trials were performed with 20 mg/mL solution of purified RAMANK. However, in the conditions studied, the drops remained clear for more than 2 wk. Due to such high solubility, protein was further concentrated and crystallization trials repeated. Rod-like shaped crystals were grown by hanging drop method with ~ 60 mg/mL solution of RAMANK equilibrated against a reservoir containing 15% PEG 10K, 0.1 M Na Cacodylate (pH 6.25). Crystals appeared within 7 d and grew to their maximum size (0.6 × 0.4 × 0.1 mm) in 7–10 d. To confirm its content, crystals were extensively washed in mother liquor, dissolved, and subjected to SDS PAGE gel electrophoresis. To our surprise, a 46 kDa band corresponding to residues 1781–2221 of the mouse Notch-1 was no longer present; instead, the crystal contained a 14 kDa proteolytic fragment. The 14 kDa band was N-terminally sequenced. The first five residues were NRATD, which mapped the N terminus to the middle of the third ankyrin repeat of mouse Notch 1. The identity of the crystallized fragment was further confirmed by MALDI mass spec analysis (PNACL, Washington University School of Medicine).

Data were collected at an LN temperature at beamline 19BM at Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratories. Data were processed with the program HKL2000 and scaled with SCALEPACK (Otwinowski and Minor 1997). Under initial inspection crystals belonged to space group P3121 with unit cell dimensions a = b = 75.89 Å, c = 45.87 Å.

Molecular replacement and initial refinement

Molecular replacement was performed with CNS (Brünger et al. 1998). The search was created with the coordinates of the dANK domain (RCSB PDB code 1OT8). The rotation search with space group P3121 yielded one top solution of 11 σ corresponding to one molecule in the asymmetric unit, with the next highest peak having a height of 7.7 σ. With one molecule in the asymmetric unit, the correlation coefficient was 52.6% and R-factor, 42.5%. Although the MR replacement solution was readily obtained, subsequent refinement did not improve the quality of the electron density maps nor did it decrease the crystallographic R-factors. A careful look at the data indicated that the crystals were merohedrally twinned with the true space group P31.

The twin fraction was estimated to be around 50% (http://www.doe-mbi.ucla.edu/Services/Twinning/), indicating perfect merohedral twinning. Data from more than 18 different crystals were collected in the hope of finding untwinned crystals. For all of them, the twin fraction was close to 50%.

Subsequently, CNS scripts for refinement of the perfect twin were used. The refinement proceeded with NCS and harmonic restraints. These approach resulted in substantial improvement of the geometry and electron density maps. The R-factors converged to R = 22.6% and Rfree = 30.6%, with 80% of the residues in the most favored regions (PROCHECK; Laskowski et al. 1993). The final model contained two molecules (with 130 residues each) and 161 waters. Data collection and refinement statistics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Data collection | |

| Resolution (Å) | 50–2.2 |

| R-factora | 0.04 (0.20) |

| Completenessa | 86 (53) |

| Wavelength (A) | 0.9 |

| Refinement | |

| No. of protein non-H atoms | 2101 |

| No. of water molecules | 161 |

| No. of reflections | 11,012 |

| No. of refl. test set (5%) | 549 |

| R (%)a | 21.5 (31.2) |

| Free R (%)a | 30.6 (36.9) |

| RMSD bonds (Å) | 0.012 |

| Angles | 1.7 |

| Overall B factor (Å2) | 46 |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| Most favored (%) | 80 |

| Allowed (%) | 19.6 |

| Generously allowed (%) | 0.4 |

| Disallowed | 0 |

a Values for the highest resolution shell 2.2–2.3 Å are shown in parentheses.

Coordinates were deposited into the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, under the accession code 1YMP.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Tom Bredt and members of the Fremont lab for help with the data collection, and Dr. Zwei Cheng and Professor Scott Mathews for useful discussions on crystal twinning and structure refinement. O.L was supported by Keck postdoctoral fellowship; G.W. by NIH Grants RO1GM54033, RO1GM60231, and RO1AI49950; R.K. by NIH Grant GM55479-09; and S.K. by the E.A. Doisy Trust Fund.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.041184105.

References

- Artavanis-Tsakonas, S., Rand, M.D., and Lake, R.J. 1999. Notch signaling: Cell fate control and signal integration in development. Science 284 770–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton, G.J. 1993. ALSCRIPT: A tool to format multiple sequence alignments. Protein Eng. 6 37–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatus, P., Lundkvist, J., Oberg, C., and Lendahl, U. 1999. The notch 3 intra-cellular domain represses notch 1-mediated activation through Hairy/Enhancer of split (HES) promoters. Development 126 3925–3935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatus, P., Lundkvist, J., Oberg, C., Pedersen, K., and Lendahl, U. 2001. The origin of the ankyrin repeat region in Notch intracellular domains is critical for regulation of HES promoter activity. Mech. Dev. 104 3–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bork, P. 1993. Hundreds of ankyrin-like repeats in functionally diverse proteins: Mobile modules that cross phyla horizontally? Proteins 17 363–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, C.M. and Barrick, D. 2002. Limits of cooperativity in a structurally modular protein: Response of the Notch ankyrin domain to analogous alanine substitutions in each repeat. J. Mol. Biol. 324 373–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray, S. 1998. A Notch affair. Cell 93 499–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünger, A.T., Adams, P.D., Clore, G.M., DeLano, W.L., Gros, P., Grosse-Kunstleve, R.W., Jiang, J.S., Kuszewski, J., Nilges, M., Pannu, N.S., et al. 1998. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macro-molecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cammett, T.J., Luo, L., and Peng, Z.Y. 2003. Design and characterization of a hyperstable p16INK4a that restores Cdk4 binding activity when combined with oncogenic mutations. J. Mol. Biol. 327 285–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croy, C.H., Bergqvist, S., Huxford, T., Ghosh, G., and Komives, E.A. 2004. Biophysical characterization of the free IκBα ankyrin repeat domain in solution. Protein Sci. 13 1767–1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer, C.J., Lamar, E., Turbachova, I., Kintner, C., and Jones, K.A. 2002. Mastermind mediates chromatin-specific transcription and turnover of the Notch enhancer complex. Genes & Dev. 16 1397–1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gridley, T. 2003. Notch signaling and inherited disease syndromes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12(Suppl. 1): R9–R13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxford, T., Huang, D.B., Malek, S., and Ghosh, G. 1998. The crystal structure of the IκBα/NF-κB complex reveals mechanisms of NF-κB inactivation. Cell 95 759–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, M.D. and Harrison, S.C. 1998. Structure of an IκBα/NF-κB complex. Cell 95 749–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffries, S., Robbins, D.J., and Capobianco, A.J. 2002. Characterization of a high-molecular-weight Notch complex in the nucleus of Notch(ic)-transformed RKE cells and in a human T-cell leukemia cell line. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22 3927–3941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao, H.Y., Ordentlich, P., Koyano-Nakagawa, N., Tang, Z., Downes, M., Kintner, C.R., Evans, R.M., and Kadesch, T. 1998. A histone deacetylase corepressor complex regulates the Notch signal transduction pathway. Genes & Dev. 12 2269–2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato, H., Sakai, T., Tamura, K., Minoguchi, S., Shirayoshi, Y., Hamada, Y., Tsujimoto, Y., and Honjo, T. 1996. Functional conservation of mouse Notch receptor family members. FEBS Lett. 395 221–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriwacki, R.W., Hengst, L., Tennant, L., Reed, S.I., and Wright, P.E. 1996. Structural studies of p21Waf1/Cip1/Sdi1 in the free and Cdk2-bound state: Conformational disorder mediates binding diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 93 11504–11509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski, R.A., MacArthur, M.W., Moss, D.S., and Thornton, J.M. 1993. PROCHECK: A program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26 283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Liedtke, W., Choe, Y., Marti-Renom, M.A., Bell, A.M., Denis, C.S., Sali, A., Hudspeth, A.J., Friedman, J.M., and Heller, S. 2000. Vanilloid receptor-related osmotically activated channel (VR-OAC), a candidate vertebrate osmoreceptor. Cell 103 525–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubman, O.Y., Korolev, S.V., and Kopan, R. 2004. Anchoring notch genetics and biochemistry; structural analysis of the ankyrin domain sheds light on existing data. Mol. Cell 13 619–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello, C.C. and Barrick, D. 2004. An experimentally determined protein folding energy landscape. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 101 14102–14107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizutani, T., Taniguchi, Y., Aoki, T., Hashimoto, N., and Honjo, T. 2001. Conservation of the biochemical mechanisms of signal transduction among mammalian Notch family members. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98 9026–9031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosavi, L.K., Williams, S., and Peng Zy, Z.Y. 2002. Equilibrium folding and stability of myotrophin: A model ankyrin repeat protein. J. Mol. Biol. 320 165–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosavi, L.K., Cammett, T.J., Desrosiers, D.C., and Peng, Z.Y. 2004. The ankyrin repeat as molecular architecture for protein recognition. Protein Sci. 13 1435–1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam, Y., Weng, A.P., Aster, J.C., and Blacklow, S.C. 2003. Structural requirements for assembly of the CSL.intracellular Notch1.Mastermind-like 1 transcriptional activation complex. J. Biol. Chem. 278 21232–21239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald, F., Tauber, B., Dobner, T., Bourteele, S., Kostezka, U., Adler, G., Liptay, S., and Schmid, R.M. 2001. p300 acts as a transcriptional coactivator for mammalian Notch-1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21 7761–7774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski, Z. and Minor, W. 1997. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petcherski, A.G. and Kimble, J. 2000. LAG-3 is a putative transcriptional activator in the C. elegans Notch pathway. Nature 405 364–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radtke, F. and Raj, K. 2003. The role of Notch in tumorigenesis: Oncogene or tumour suppressor? Nat. Rev. Cancer 3 756–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, M.T., Schroeter, E.H., Mumm, J.S., and Kopan, R. 2001. Murine notch homologs (N1–4) undergo presenilin-dependent proteolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 276 40268–40273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweisguth, F. 2004. Notch signaling activity. Curr. Biol. 14 R129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, K., Taniguchi, Y., Minoguchi, S., Sakai, T., Tun, T., Furukawa, T., and Honjo, T. 1995. Physical interaction between a novel domain of the receptor Notch and the transcription factor RBP-J κ/Su(H). Curr. Biol. 5 1416–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, K.S., Guralnick, B.J., Wang, W.K., Fersht, A.R., and Itzhaki, L.S. 1999. Stability and folding of the tumour suppressor protein p16. J. Mol. Biol. 285 1869–1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, K.S., Fersht, A.R., and Itzhaki, L.S. 2003. Sequential unfolding of ankyrin repeats in tumor suppressor p16. Structure (Camb.) 11 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tani, S., Kurooka, H., Aoki, T., Hashimoto, N., and Honjo, T. 2001. The N- and C-terminal regions of RBP-J interact with the ankyrin repeats of Notch1 RAMIC to activate transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 29 1373–1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tevelev, A., Byeon, I.J., Selby, T., Ericson, K., Kim, H.J., Kraynov, V., and Tsai, M.D. 1996. Tumor suppressor p16INK4A: Structural characterization of wild-type and mutant proteins by NMR and circular dichroism. Biochemistry 35 9475–9487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarbrough, W.G., Buckmire, R.A., Bessho, M., and Liu, E.T. 1999. Biologic and biochemical analyses of p16(INK4a) mutations from primary tumors. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 91 1569–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B. and Peng, Z. 1996. Defective folding of mutant p16(INK4) proteins encoded by tumor-derived alleles. J. Biol. Chem. 271 28734–28737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2002. Structural consequences of tumor-derived mutations in p16INK4a probed by limited proteolysis. Biochemistry 41 6293–6302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S. and Hayward, S.D. 2001. Nuclear localization of CBF1 is regulated by interactions with the SMRT corepressor complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21 6222–6232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S., Fujimuro, M., Hsieh, J.J., Chen, L., Miyamoto, A., Weinmaster, G., and Hayward, S.D. 2000. SKIP, a CBF1-associated protein, interacts with the ankyrin repeat domain of NotchIC To facilitate NotchIC function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20 2400–2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweifel, M.E. and Barrick, D. 2001a. Studies of the ankyrin repeats of the Drosophila melanogaster Notch receptor. 1. Solution conformational and hydrodynamic properties. Biochemistry 40 14344–14356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2001b. Studies of the ankyrin repeats of the Drosophila melanogaster Notch receptor. 2. Solution stability and cooperativity of unfolding. Biochemistry 40 14357–14367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweifel, M.E., Leahy, D.J., Hughson, F.M., and Barrick, D. 2003. Structure and stability of the ankyrin domain of the Drosophila Notch receptor. Protein Sci. 12 2622–2632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]