Abstract

Understanding relationships between sequence, structure, and evolution is important for functional characterization of proteins. Here, we define a novel DOM-fold as a consensus structure of the domains in DmpA (L-aminopeptidase D-Ala-esterase/amidase), OAT (ornithine acetyltransferase), and MocoBD (molybdenum cofactor-binding domain), and discuss possible evolutionary scenarios of its origin. As shown by a comprehensive structure similarity search, DOM-fold distinguished by a two-layered β/α architecture of a particular topology with unusual crossing loops is unique to those three protein families. DmpA and OAT are evolutionarily related as indicated by their sequence, structural, and functional similarities. Structural similarity between the DmpA/OAT superfamily and the MocoBD domains has not been reported before. Contrary to previous reports, we conclude that functional similarities between DmpA/OAT proteins and N-terminal nucleophile (Ntn) hydrolases are convergent and are unlikely to be inherited from a common ancestor.

Keywords: DmpA, NylC, OAT, Ntn hydrolases, molybdenum cofactor-binding domain, convergent evolution, divergent evolution, duplication and fusion, domain swapping

Proteins share the same fold if they have the same set of major secondary structure elements orientated and connected in the same way (Murzin et al. 1995; Grishin 2001). Fold similarity does not necessarily imply common evolutionary origin. Divergent evolution, or homology, explains fold similarity in terms of inheritance from a common ancestor, while in convergent evolution, or analogy, the common fold is arrived at independently due to the limited possibilities in structural space (Orengo et al. 2001; Krishna and Grishin 2004). Given a specific case, the choice between these two scenarios is important yet sometimes difficult, and requires integration of our knowledge about the proteins in question (Murzin 1998). Here, we analyze evolutionary relationships between three protein families that we found to share a common fold: DmpA (L-aminopeptidaseD- Ala-esterase/amidase), OAT (ornithine acetyltransferase), and MocoBD (molybdenum cofactor-binding domain).

DmpA is a unique enzyme, since it not only releases N-terminal L-amino acids from peptide substrates but also acts on amide or ester derivatives of D-Ala (Fanuel et al. 1999). The other experimentally characterized DmpA family member is NylC, an amidohydrolase degrading the by-products of nylon manufacture (Negoro et al. 1992; Negoro 2000). The mature forms of both DmpA and NylC undergo cleavage in front of a nucleophile (Ser250 in DmpA and Thr267 in NylC). Since this cleavage happens in recombinant DmpA or NylC produced by Escherichia coli, as well as in native proteins purified from the original hosts, it is likely to be self-catalyzed (Kakudo et al. 1993, 1995; Fanuel et al. 1999). Ser250 in DmpA is indicated by mutagenesis studies to be crucial for both precursor cleavage and enzymatic activity, and is speculated to be the catalytic nucleophile (Fanuel et al. 1999). The only available structure for the DmpA family is that of Ochrobactrum anthropi DmpA (PDB 1b65), which exhibits a four-layered αββα architecture with Ser250 positioned at the N terminus of a β-strand (Bompard-Gilles et al. 2000) (Fig. 1A ▶).

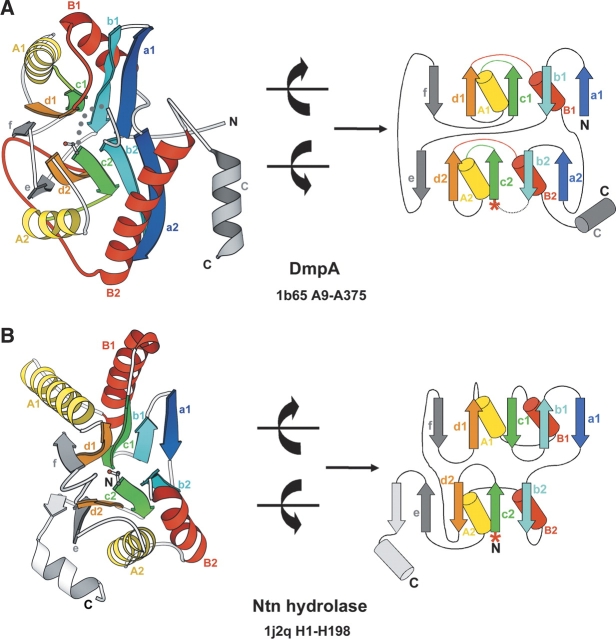

Figure 1.

Structural and topological comparisons of DmpA and Ntn hydrolase. MOLSCRIPT (Kraulis 1991) and topology diagrams of DmpA (A) and archaeal proteasome β subunit (Groll et al. 2003) as an example of Ntn hydrolases (B). In DmpA diagrams, α-helices and β-strands constituting the two structural domains, DmpA_1 and DmpA_2, are colored from blue (N terminus) to red (C terminus). The remaining secondary structure elements are shown in gray. α-Helices and β-strands are labeled with upper- or lowercase letters, respectively, followed by the domain number (e.g., strand a in DmpA_1 is labeled a1 while strand a in DmpA_2 is labeled a2). Labels are in the same color as the secondary structure elements they represent. Except for the crossing loops highlighted in green and red, loop regions are shown in gray. Dotted lines indicate the autocleavage site. In Ntn hydrolase diagrams, the secondary structure elements are colored and labeled according to their spatial equivalents in DmpA. The last α-helix and β-strand are colored white since they do not have structural equivalents in DmpA. For all structures, N and C termini are labeled and the PDB code, the chain ID, and the starting and ending residue numbers are indicated. Catalytic nucleophiles (Ser250 in DmpA and Thr1 in Ntn hydrolase) are shown in ball-and-stick representation or as asterisks in MOLSCRIPT or topology diagrams, respectively. To make the topology diagrams, each structure is separated between the two β-sheets and rotated roughly 90° as indicated by the curved arrows (“open book”).

OAT functions in the arginine biosynthetic pathway by transferring an acetyl group from N-acetylornithine to glutamate. The OAT precursor is activated by an autocleavage before an invariant Thr that is shown to be critical for both precursor processing and catalytic activity (Abadjieva et al. 2000; Marc et al. 2001). The recently solved OAT structure (PDB 1vz6) reveals that OAT domain 1 has the same fold as DmpA and that their putative catalytic nucleophiles occupy structurally equivalent positions (Elkins et al. 2005).

MocoBD is found in a group of molybdenum hydroxylases, such as xanthine dehydrogenase/oxidase, aldehyde oxidoreductase, and carbon monoxide dehydrogenase (Hille 1996; Kisker et al. 1998). Several MocoBD structures have been solved, and they all share a butterfly-shaped architecture (Fig. 2B ▶) with the molybdenum co-factor bound in the center (Rebelo et al. 2001; Dobbek et al. 2002; Truglio et al. 2002; Bonin et al. 2004).

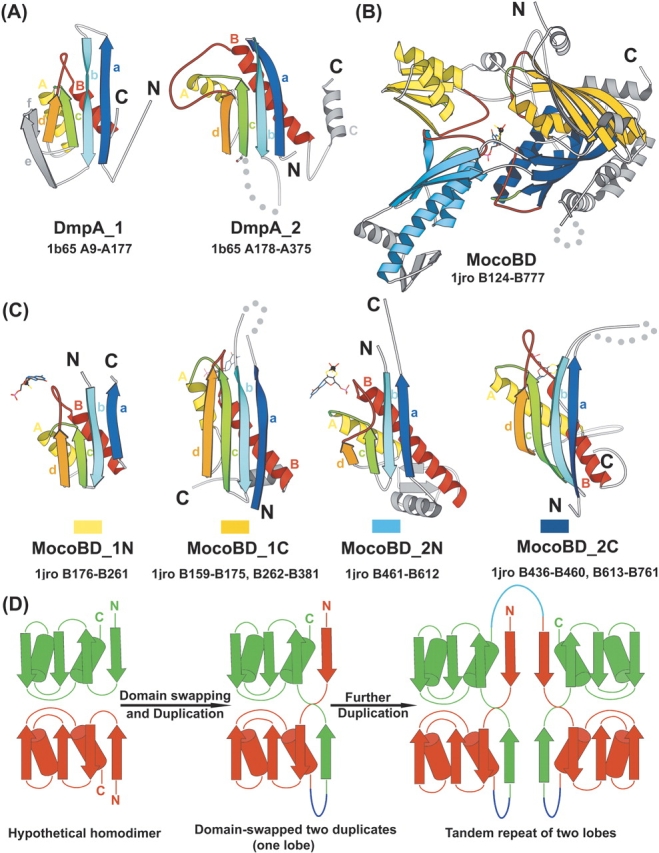

Figure 2.

Structural comparison of DmpA and MocoBD domains. (A) The two structural domains of DmpA. (B) The structure of MocoBD. (C) The four domains of MocoBD. In A and C, spatially equivalent secondary structure elements are colored and labeled correspondingly in the same way as in Figure 1A ▶. In B, the four structural domains are shown in different colors: 1N, light yellow; 1C, dark yellow; 2N, light blue; 2C, dark blue. The two lobes are colored in yellow and blue, respectively. The molybdenum cofactor in B and C is shown in bonds representation with the molybdenum atom highlighted as a black ball. In C, the rectangular bar below each structure shows the color in which that domain is represented in B. For all structures, the crossing loops are highlighted in green and red; secondary structure elements that do not belong to the consensus fold of DmpA and MocoBD domains are shown in gray; dotted lines represent disordered regions or long insertions; N and C termini are labeled and the PDB code, the chain ID, and the starting and ending residue numbers are shown. Diagrams are drawn with MOLSCRIPT (Kraulis 1991). (D) A proposed model for MocoBD to evolve from a single-domain ancestor. The single-domain ancestor may form a homodimer (or a homotetramer). Duplication, fusion, and domain swapping created one lobe in which the two duplicates exchange their first strand. The linker region between the two domains is colored in blue. The lower, mainly red domain corresponding to 1N/2N seems to be circularly permuted and inserted into the upper, mainly green domain corresponding to 1C/2C. Further duplication of this lobe resulted in the four domains in MocoBD. The linker between the two lobes is colored in cyan.

Here, we unify DmpA and OAT domain 1 in the DmpA/OAT superfamily. Homology between DmpA and OAT is implied by their sequence, structural, and functional similarities. We demonstrate that structural domains of DmpA/OAT and MocoBD share the same fold, which is not present in any other proteins of known structure. We name this fold the DOM-fold after DmpA, OAT, and MocoBD. The evolutionary relationships between the structural domains in the DOM-fold are discussed.

Results and Discussion

DmpA and OAT domain 1 are homologs, since they share not only the same fold, but also sequence and functional similarities. Although DmpA/OAT was suggested in literature to be evolutionarily related to the Ntn hydrolases, we stress and illustrate SCOP’s (Structural Classification of Proteins database) notion that similarities between these proteins resulted from convergent instead of divergent evolution. The two structural domains in DmpA (or in OAT) that adopt the DOM-fold are likely to have arisen from gene duplication and fusion. Similarly, four structural domains in MocoBD that share the DOM-fold are probably homologs; however, in this case, domain swapping has to be added to duplication and fusion to account for the seemingly complex domain arrangement. Although DmpA/OAT domains and MocoBD domains share the same DOMfold, the lack of other evidence for homology makes their evolutionary relationship unclear. In addition, we discuss the register problem in superimposing the structural domains in the DOM-fold.

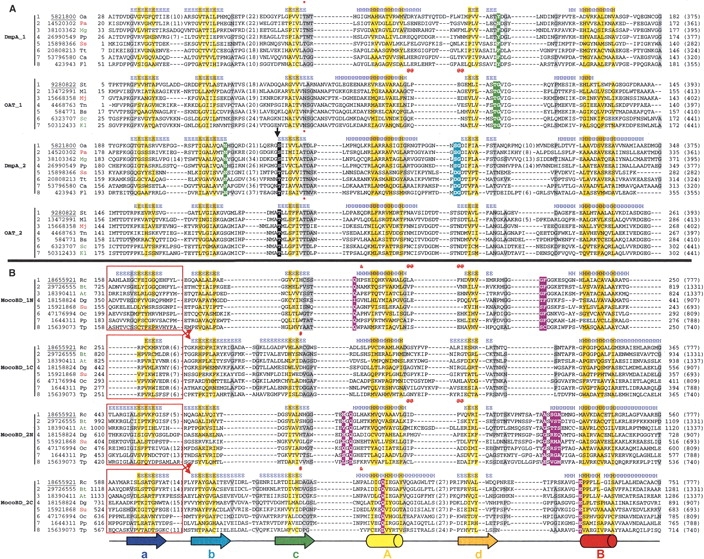

DmpA and OAT: Divergent evolution

The similarity between DmpA and OAT remained unreported prior to the determination of the OAT structure (Elkins et al. 2005). DALI (Holm and Sander 1993) aligns 213 out of 261 residues in OAT domain 1 to DmpA with a Z-score of 13.4 and RMSD of 3.7Å. It has been hypothesized (Dokholyan et al. 2002) that DALI Z-scores greater than 9 correspond to homologs. In addition to the common fold, DmpA family and OAT family show detectable sequence similarity. For instance, an OAT family member (gi|50312433) appeared in the output of a PSI-BLAST search (Altschul et al. 1997), initiated with a DmpA family member (gi|53796580), at the fourth iteration with an E-value of 0.018 and the putative catalytic nucleophiles aligned correctly (NCBI nonredundant database with 2,204,172 sequences, December 8, 2004). In the multiple sequence alignment in Figure 3A ▶, the DmpA and OAT family members exhibit similar hydrophobicity (yellow shading) and small residue (gray shading) patterns. Furthermore, apparent functional similarities exist between the DmpA and OAT families. First, they both break amide bonds during catalysis, although DmpA and NylC are hydrolases, while OAT is an acyl-transferase. Second, their precursors are both activated by an autocleavage in front of the putative catalytic nucleophile positioned at the N terminus of a β-strand (Fanuel et al. 1999; Bompard-Gilles et al. 2000; Elkins et al. 2005). In Figure 3A ▶, the activation cleavage site is marked by an arrow, and the putative catalytic nucleophiles are boxed in black. Pronounced structural similarity between DmpA and OAT is enhanced by sequence and functional similarities to make a convincing argument that these two families are homologous. Thus, we unify them into the DmpA/OAT superfamily.

Figure 3.

Multiple sequence alignment of representative sequences in DmpA/OAT superfamily (A) and MocoBD superfamily (B). Each group of sequences corresponds to a structural domain specified to the left of the group. Different sequences within the same group were aligned by the PCMA program (Pei et al. 2003). For each sequence, the NCBI gene identification (gi) number follows the serial number; the first and last residue numbers are indicated before and after the sequence, respectively, and the full length of the protein is shown in parentheses at the end. The species name abbreviations follow the gi numbers and are colored in red, black, and green for archaea, bacteria, and eukaryota, respectively. The eight groups were aligned together according to a structural superposition of the eight domains in the three reference structures (PDB 1b65 chain A for DmpA, PDB 1vz6 chain A for OAT, and PDB 1jro chain B for MocoBD). The structural features used for selecting the registers are marked by various symbols (*, @, #, &). The first gi number in each group is underlined to indicate that it corresponds to the reference structure. Secondary structure elements (E for β-strands and H for α-helices) are labeled above each group according to the reference structure. Note that MocoBD_1N and MocoBD_1C or MocoBD_2N and MocoBD_2C as shown in Figure 2C ▶ swapped their first strands in this multiple alignment to make the sequences continuous, as indicated by the red boxes and arrows. The secondary structure diagram (cylinders for α-helices and arrows for β-strands) at the bottom of this figure is colored and labeled in the same way as in Figure 2, A and C ▶. Uncharged residues (any residue except K, R, E, D) at positions in the interface between the α-helix layer and the β-strand layer in each domain are shaded in yellow. Small residues (G, A, C, P, T, S, V, D, N) at positions containing mainly small residues are shaded in gray. Long insertions between the aligned secondary structure elements are omitted for clarity, and the numbers of omitted residues are indicated in parentheses. In A, the autocleavage site is indicated by a black arrow. The functional residues of DmpA and OAT are identified according to Bompard-Gilles et al. (2000) and Elkins et al. (2005), respectively, and are highlighted in different colors: nucleophile, black; nucleophile stabilization, cyan; and oxyanion hole, green. In B, the residues participating in molybdenum cofactor-binding are identified according to Figure 6 in Truglio et al. (2002) and are highlighted in purple. Species name abbreviations are At, Arabidopsis thaliana; Bs, Bacillus stearothermophilus; Bt, Bos taurus; Ca, Chloroflexus aurantiacus; Dg, Desulfovibrio gigas; Fl, Flavobacterium sp.; Kl, Kluyveromyces lactis NRRL Y-1140; Mg, Magnaporthe grisea 70-15; Mj, Methanocaldococcus jannaschii DSM 2661; Ml, Mesorhizobium loti MAFF303099; Oa, Ochrobactrum anthropi; Oc, Oligotropha carboxidovorans; Pa, Pyrococcus abyssi GE5; Pp, Pseudomonas putida; Rc, Rhodobacter capsulatus; Sc, Saccharomyces cerevisiae; Ss, Sulfolobus solfataricus P2; St, Streptomyces clavuligerus; Su, Sulfolobus tokodaii str. 7; Tn, Thermotoga neapolitana; Tp, Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum str. Nichols; Tt, Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis.

DmpA/OAT and Ntn hydrolases: Convergent evolution

Ntn hydrolases (Ntn for N-terminal nucleophile) are a diverse superfamily of amidohydrolases. Enzymes in this superfamily share a four-layered αββα architecture with the catalytic nucleophile (Cys, Ser, or Thr) positioned at the N terminus of a β-strand. The α-amino group of the nucleophile is freed in a self-catalyzed activation cleavage and is involved in catalysis as the general base (Oinonen and Rouvinen 2000). DmpA/OAT resembles Ntn hydrolases in function and structural architecture, but differs in directionality and connectivity of secondary structure elements (Bompard-Gilles et al. 2000; Elkins et al. 2005). Similarities between DmpA/OAT and Ntn hydrolases include breakage of amide bonds during catalysis, an autocleavage before the putative catalytic nucleophile as the activation mechanism, a position of the putative catalytic nucleophile at the N terminus of a β-strand, and a four-layered αββα overall architecture. The differences between these two groups of enzymes are illustrated in Figure 1 ▶. Using the nucleophile residues (Ser250 in DmpA and Thr1 in Ntn hydrolase) as reference, the structures of DmpA and Ntn hydrolase can be superimposed. The secondary structure elements of the Ntn hydrolase are colored and labeled according to their spatial equivalents in DmpA. Out of 13 pairs of equivalent secondary structure elements, seven are in opposite main-chain directions. A comparison of the topology diagrams readily reveals the extensive differences in the connectivity of secondary structure elements between DmpA and Ntn hydrolase (Fig. 1A, B ▶). Clearly, DmpA/ OAT superfamily has a distinct fold from the Ntn hydrolase superfamily, as stated in SCOP (Murzin et al. 1995) and CATH (Class, Architecture, Topology, and Homologous superfamily) protein structure classification (Orengo et al. 1997).

To rationalize the observed functional and architectural similarities, DmpA/OAT and Ntn hydrolases were previously suggested to be evolutionarily related (Bompard-Gilles et al. 2000; Elkins et al. 2005). Considering the fundamental topology differences in their folds, we agree with SCOP that the functional and architectural similarities between DmpA/OAT and Ntn hydrolases are the result of convergent evolution, rather than a reflection of common evolutionary origin. However, compared to other functional convergence examples like chymotrypsin and subtilisin (Russell 1998; Branden and Tooze 1999), DmpA/OAT and Ntn hydrolases are interesting in that they exhibit not only local, functional similarities but also overall, architectural resemblance with many superimposable secondary structure elements, albeit often in reverse chain direction. We are aware of only two other reported examples of this kind of structure–functional convergence (Makarova and Grishin 1999; Gladyshev 2002).

Two structural domains in DmpA/OAT are homologous

The overall architecture of DmpA or OAT domain 1 consists of four layers: αββα (Fig. 1A ▶). However, as indicated in SCOP, this four-layered architecture can be divided into two similar structural domains named DmpA_1 and DmpA_2 or OAT_1 and OAT_2 here. DALI aligns DmpA_1 and DmpA_2 with a Z score of 4.2 and a RMSD of 3.9Å over 94 equivalent residue pairs. In Figure 1A ▶, equivalent secondary structure elements in these two domains are shown in the same color and labeled accordingly. Figure 2A ▶ is a diagram of isolated DmpA_1 and DmpA_2 with the same coloring and labeling theme as in Figure 1A ▶. The consensus fold of these two structural domains consists of four mixed β-strands (a, b, c, and d) forming one layer and two parallel α-helices (A and B) forming a second layer, and the connectivity of these secondary structure elements is a-b-c-A-d-B. Strands e, f, and helix C are considered to be insertions and shaded in gray. Both DmpA_1 and DmpA_2 (or OAT_1 and OAT_2) contain a pair of crossing loops, namely, the loop connecting strand c and helix A highlighted in green and the loop connecting strand d and helix B highlighted in red. Such crossing loops are believed to be energetically unfavorable and are rarely observed in protein structures (Finkelstein and Ptitsyn 1987; Finkelstein et al. 1993). Thus, it is an unusual and distinctive characteristic of the DmpA/OAT structural domains.

The structural similarity between DmpA_1 and DmpA_2 (or OAT_1 and OAT_2) can be rationalized through homology as a gene duplication and fusion event or, alternatively, as chance convergence. Since the common fold of these two domains is reasonably complex and the crossing loops are rare, the convergence scenario is highly unlikely. On the contrary, since duplication is a frequently observed phenomenon in molecular evolution (Heringa and Taylor 1997; Heringa 1998), the two structural domains in DmpA/OAT are likely to be homologous.

Four structural domains in MocoBD are homologous

Figure 2B ▶ shows a diagram of the MocoBD in Rhodobacter capsulatus xanthine dehydrogenase (Truglio et al. 2002). According to SCOP, MocoBD consists of four similar structural domains named MocoBD_1N (light yellow), MocoBD_1C (dark yellow), MocoBD_2N (light blue), and MocoBD_2C (dark blue) here. 1N and 1C make up lobe 1 (yellow), and 2N and 2C make up lobe 2 (blue). The DALI Z-scores for these four domains are 1N&2N, 8.4; 1C&2C, 6.9; 1N&1C, 3.2; 1N&2C, 3.8; 2N&1C, 3.3; 2N&2C, 3.6. Apparently, 1N and 2N are more similar to each other, while 1C and 2C are more similar to each other. Figure 2C ▶ illustrates similarities and differences between these four domains of MocoBD. Their consensus structure consists of two parallel α-helices (A and B) packed against four mixed β-strands (a, b, c, and d). The sequential order of these secondary structure elements in 1N and 2N is b-c- A-d-B-a, while in 1C and 2C it is a-b-c-A-d-B. Thus, 1N/ 2N can be viewed as a circularly permuted form (Lindqvist and Schneider 1997) of 1C/2C, i.e., linking the N and C termini of 1N/2N, and cutting between helix B and strand a would transform it into the topology of 1C/2C. Note that 1N/2N has a rare left-handed β-α-β connection (Richardson 1976; Sternberg and Thornton 1977) comprised of d, B, and a. Additionally, as indicated by the residue numbers below each domain in Figure 2C ▶, 1N ▶ and 2N ▶ can be considered as insertions in 1C and 2C, respectively.

Since lobe 1 and lobe 2 have the same complex domain arrangements, namely, 1N/2N is circularly permuted and inserted into 1C/2C, it appears that these two lobes arose from a duplication and fusion event. Such a tandem duplication and fusion scenario can also be applied to explain the structural similarity between the two domains within the same lobe, if we assume that the two domains swapped their first strand (strand a). Domain swapping (“domain” here may be a single secondary structure element) is believed to be an important mechanism for oligomer formation and is observed in many proteins (Bennett et al. 1995; Liu and Eisenberg 2002). In particular, swapping between two duplicates is also reported in some proteins, such as two PLP-independent amino acid racemases (Cirilli et al. 1998; Liu et al. 2002). In those racemases, swapping causes the same complex domain arrangement as in the two lobes of MocoBD. Since both duplication and domain swapping are fairly common phenomena in protein evolution, we propose that the four MocoBD domains evolved from a single-domain ancestor by domain swapping and two sequential duplications, and that they are thus homologous. Our model is shown in Figure 2D ▶. This model suggests that the ancestral domain had the same topology as 1C/2C, or as DmpA/OAT domains (see below), and that the unusual left-handed β-α-β connection in 1N/2N is a natural consequence of swapping, duplication, and fusion. Previously, domain swapping between duplicates has been suggested to cause another structural irregularity: knots (Taylor et al. 2001).

The structural domains in DmpA/OAT and in MocoBD share the same fold

SCOP treats both DmpA and MocoBD as integral multi-domain functional units and appropriately classifies them in two different folds. However, inspection of the structural neighbors of DmpA in the FSSP (fold classification based on structure–structure alignment of proteins) database (Holm and Sander 1996) revealed that the DmpA domains and the MocoBD domains are structurally similar. For instance, DALI aligns MocoBD_1N and DmpA_2 with a Z-score of 4.4 and a RMSD of 2.6 Å over 70 equivalent residues. As shown in Figure 2 ▶, A and C, the two DmpA domains and the four MocoBD domains all have four mixed β-strands (a, b, c, and d) packed against two parallel α-helices (A and B) in the sequential order of a-b-c-A-d-B (if 1N and 2N were circularly permuted). Therefore, individual domains in DmpA and MocoBD share the same fold. We name this fold the DOM-fold after the three families in which it is found: DmpA, OAT, and MocoBD. An unusual characteristic of this fold is a pair of crossing loops at the ends of the third and the fourth strands (highlighted in green and in red in Fig. 2 ▶). Additionally, a circularly permuted form of this fold as observed in 1N and 2N has a rare left-handed β-αβ connection. In search for other proteins possessing this fold, we used several structure similarity search programs including DALI (Holm and Sander 1996), MSD fold (Krissinel and Henrick 2004), fold miner (Shapiro and Brutlag 2004a, b), and a structural motif search program under development in our group. Careful inspection of the found structural similarities revealed no other proteins with all six secondary structure elements present in the same arrangement and with the same topology, even allowing for all possible circular permutations. The closest DALI hit belongs to the “ribosomal protein S5 domain 2-like” fold in SCOP. This fold differs from the DOM-fold in the mutual positions of the third and the fourth strands, i.e., if strand c and strand d in Figure 2 ▶ switch their positions, DOM-fold can be converted into the “ribosomal protein S5 domain 2-like” fold.

The evolutionary meaning of the structural similarity between DmpA/OAT domains and MocoBD domains remains unclear. Extensive PSI-BLAST searches (Altschul et al. 1997; Walker and Koonin 1997) failed to link DmpA/OAT with MocoBD. DmpA/OAT and MocoBD perform different functions: DmpA/OAT is an amidohydrolase/acyl-transferase, while MocoBD is part of an oxidoreductase, and they exhibit different functional residues at different positions (Fig. 3 ▶). Although the structural domains in DmpA/OAT and in MocoBD share the same DOM-fold, they are assembled into functional units differently. DmpA_1 and DmpA_2 (or OAT_1 and OAT_2) pack together in a head-to-tail fashion through their β-strand layers (Fig. 1A ▶), whileMocoBDdomains all point their crossing-loop ends at the molybdenum cofactor, and 1C and 2C interact with each other mainly through their α-helix layers (Fig. 2B ▶). Since DmpA/OAT and MocoBD lack statistically supported sequence similarity and differ in functional residues andmutual positioning of domains, we do not have enough evidence to infer homology between them. However, considering the fact that their common fold with the unusual crossing loops is so far unique among known protein structures, we tend to believe that a divergent scenario is more likely for them. The increase in available sequence and structure data may provide relevant connections between these two superfamilies in the future.

Structural alignment difficulties: Register and small structural features

When structural similarity between proteins is relatively low, it is problematic to obtain meaningful residue-to- residue alignment of their structures. One of such problems is mutual register of the two structures. Due to the intrinsic periodicity of α-helices and β-strands, several plausible alignments may exist that differ from one another by a shift of one structure on the other. For instance, since β-strands are repeats of two-residue units, one can superimpose two β-strands in several registers by shifting one strand relative to the other by two residues at a time. Sometimes, different registers show comparable structural statistics. For instance, the two best registers for MocoBD_1C and MocoBD_2C have Cα-Cα RMSD 2.58 Å over 90 equivalent residues and RMSD 2.61 Å over 92 equivalent residues, respectively, and there is a two-residue shift in the superposition of the β-sheets between these two registers.

Since the four DmpA/OAT domains (or the four MocoBD domains) are probably homologs, we attempted to find the registers that reflect their evolutionary history. For this purpose, we not only considered overall structural similarity measures such as aligned residue numbers and RMSD, but also looked for small conserved structural features that might be traces of their common ancestor (Murzin 1998). Being aware that taken individually these small features may have arisen due to some functional and structural constraints, or just random chance, we considered many such features as well as their consistency with each other and with other criteria, such as overall RMSD.

The following structural features were used to produce the resulting alignment (Fig. 3 ▶). DmpA_1, DmpA_2, and OAT_2 all have a conserved Thr at the end of strand c (marked with * above the sequences in Fig. 3A ▶). Side chains of these threonines can be superimposed closely in structure, and they all use Oγ to form a hydrogen bond with a backbone CO group on strand b. In the MocoBD domains (Fig. 3B ▶), the superposition of 1N and 2N was anchored by the tightly aligned loops (including a single-turn helix) between helix A and strand d (marked with @). In 1C and 2C, there is a conserved Asp at the end of strand c (marked with #) that uses its side chain Oδ to form a hydrogen bond with the backbone NH group of the residue two positions after it. In 1C, this Asp is substituted by an Arg in the first reference structure but can be found in other structures, e.g., PDB 1n5w, the sixth sequence. In 1N and 2C, there is a largely conserved Pro at the beginning of helix A that can be superimposed very well (marked with &). Interestingly, the loop used for selecting the register betweenMocoBD_1N and 2N has the same conformation in OAT_1 (marked with@in Fig. 3A ▶). This feature helped us align DmpA/OAT domains (Fig. 3A ▶) with MocoBD domains (Fig. 3B ▶). While it is obvious that a strong similarity in just one short loop is not enough to infer homology between these domains, it may contribute to the evidence for homology.

Conclusion

DOM-fold is defined as a four-stranded β-sheet packed against two parallel α-helices with the sequential order βββαβα, the second β-strand being anti-parallel to the rest. An unusual characteristic of this fold is the crossing loops preceding the two α-helices. Currently, DOM-fold contains two superfamilies: DmpA/OAT and MocoBD. The two structural domains inDmpA/OAT that adopt the DOM-fold are likely to be the product of a gene duplication and are thus homologs. The four DOM-domains in MocoBD are suggested to originate by duplication, and domain swapping explains the apparent circular permutation in two of the four domains. Although DOM-domains in DmpA/OAT and MocoBD possess unusual crossing loops and are structurally similar to each other, they exhibit distinct mutual positioning of domains and different locations of functional sites, and lack statistically supported sequence similarity.

Electronic supplemental material

Images of the structural features used to choose the alignment register in Figure 3 ▶ are available at ftp://iole.swmed.edu/pub/cheng/DOM-fold.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to S. Sri Krishna and Lisa Kinch for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful discussions. This work was supported by NIH grant GM67165 to N.V.G.

Abbreviations

PDB, Protein Data Bank

DmpA, L-aminopeptidase D-Ala-esterase/amidase

OAT, ornithine acetyltransferase

MocoBD, molybdenum cofactor-binding domain

Ntn, N-terminal nucleophile

PSI-BLAST, Position-Specific Iterated Basic Local Alignment Search Tool

RMSD, root mean square deviation.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.051364905.

Supplemental material: see www.proteinscience.org

References

- Abadjieva, A., Hilven, P., Pauwels, K., and Crabeel, M. 2000. The yeast ARG7 gene product is autoproteolyzed to two subunit peptides, yielding active ornithine acetyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 275 11361–11367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul, S.F., Madden, T.L., Schaffer, A.A., Zhang, J., Zhang, Z., Miller, W., and Lipman, D.J. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSIBLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, M.J., Schlunegger, M.P., and Eisenberg, D. 1995. 3D domain swapping: A mechanism for oligomer assembly. Protein Sci. 4 2455–2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bompard-Gilles, C., Villeret, V., Davies, G.J., Fanuel, L., Joris, B., Frere, J.M., and Van Beeumen, J. 2000. A new variant of the Ntn hydrolase fold revealed by the crystal structure of L-aminopeptidase D-ala-esterase/amidase from Ochrobactrum anthropi. Struct. Fold Des. 8 153–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonin, I., Martins, B.M., Purvanov, V., Fetzner, S., Huber, R., and Dobbek, H. 2004. Active site geometry and substrate recognition of the molybdenum hydroxylase quinoline 2-oxidoreductase. Structure (Camb.) 12 1425–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branden, C. and Tooze, J. 1999. Introduction to protein structure, 2d ed., pp. 210–217. Garland Publishing, New York.

- Cirilli, M., Zheng, R., Scapin, G., and Blanchard, J.S. 1998. Structural symmetry: The three-dimensional structure of Haemophilus influenzae diaminopimelate epimerase. Biochemistry 37 16452–16458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbek, H., Gremer, L., Kiefersauer, R., Huber, R., and Meyer, O. 2002. Catalysis at a dinuclear [CuSMo(==O)OH] cluster in a CO dehydrogenase resolved at 1.1-A¢ª resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99 15971–15976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dokholyan, N.V., Shakhnovich, B., and Shakhnovich, E.I. 2002. Expanding protein universe and its origin from the biological Big Bang. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99 14132–14136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins, J.M., Kershaw, N.J., and Schofield, C.J. 2005. X-ray crystal structure of ornithine acetyltransferase from the clavulanic acid biosynthesis gene cluster. Biochem. J. 385 565–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanuel, L., Goffin, C., Cheggour, A., Devreese, B., Van Driessche, G., Joris, B., Van Beeumen, J., and Frere, J.M. 1999. The DmpA aminopeptidase from Ochrobactrum anthropi LMG7991 is the prototype of a new terminal nucleophile hydrolase family. Biochem. J. 341 147–155. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, A.V. and Ptitsyn, O.B. 1987. Why do globular proteins fit the limited set of folding patterns? Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 50 171–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, A.V., Gutun, A.M., and Badretdinov, A. 1993. Why are the same protein folds used to perform different functions? FEBS Lett. 325 23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladyshev, V.N. 2002. Thioredoxin and peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase: Convergence of similar structure and function in distinct structural folds. Proteins 46 149–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grishin, N.V. 2001. Fold change in evolution of protein structures. J. Struct. Biol. 134 167–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groll, M., Brandstetter, H., Bartunik, H., Bourenkow, G., and Huber, R. 2003. Investigations on the maturation and regulation of archaebacterial proteasomes. J. Mol. Biol. 327 75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heringa, J. 1998. Detection of internal repeats: How common are they? Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 8 338–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heringa, J. and Taylor, W.R. 1997. Three-dimensional domain duplication, swapping and stealing. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 7 416–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille, R. 1996. The mononuclear molybdenum enzymes. Chem. Rev. 96 2757–2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm, L. and Sander, C. 1993. Protein structure comparison by alignment of distance matrices. J. Mol. Biol. 233 123–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1996. Mapping the protein universe. Science 273 595–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakudo, S., Negoro, S., Urabe, I., and Okada, H. 1993. Nylon oligomer degradation gene, nylC, on plasmid pOAD2 from a Flavobacterium strain encodes endo-type 6-aminohexanoate oligomer hydrolase: Purification and characterization of the nylC gene product. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59 3978–3980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1995. Characterization of endo-type 6-aminohexanoate-oligomer hydrolase from Flavobacterium sp. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 80 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kisker, C., Schindelin, H., Baas, D., Retey, J., Meckenstock, R.U., and Kroneck, P.M. 1998. A structural comparison of molybdenum cofactor-containing enzymes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 22 503–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraulis, P.J. 1991. MOLSCRIPT: A program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Cryst. 24 946–950. [Google Scholar]

- Krishna, S.S. and Grishin, N.V. 2004. Structurally analogous proteins do exist! Structure (Camb.) 12 1125–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krissinel, E. and Henrick, K. 2004. Secondary-structure matching (SSM), a new tool for fast protein structure alignment in three dimensions. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60 2256–2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindqvist, Y. and Schneider, G. 1997. Circular permutations of natural protein sequences: Structural evidence. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 7 422–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. and Eisenberg, D. 2002. 3D domain swapping: As domains continue to swap. Protein Sci. 11 1285–1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L., Iwata, K., Yohda, M., and Miki, K. 2002. Structural insight into gene duplication, gene fusion and domain swapping in the evolution of PLP-independent amino acid racemases. FEBS Lett. 528 114–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarova, K.S. and Grishin, N.V. 1999. Thermolysin and mitochondrial processing peptidase: How far structure–functional convergence goes. Protein Sci. 8 2537–2540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marc, F., Weigel, P., Legrain, C., Glansdorff, N., and Sakanyan, V. 2001. An invariant threonine is involved in self-catalyzed cleavage of the precursor protein for ornithine acetyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 276 25404–25410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murzin, A.G. 1998. How far divergent evolution goes in proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 8 380–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murzin, A.G., Brenner, S.E., Hubbard, T., and Chothia, C. 1995. SCOP: A structural classification of proteins database for the investigation of sequences and structures. J. Mol. Biol. 247 536–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negoro, S. 2000. Biodegradation of nylon oligomers. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 54 461–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negoro, S., Kakudo, S., Urabe, I., and Okada, H. 1992. A new nylon oligomer degradation gene (nylC) on plasmid pOAD2 from a Flavo-bacterium sp. J. Bacteriol. 174 7948–7953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oinonen, C. and Rouvinen, J. 2000. Structural comparison of Ntn-hydrolases. Protein Sci. 9 2329–2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orengo, C.A., Michie, A.D., Jones, S., Jones, D.T., Swindells, M.B., and Thornton, J.M. 1997. CATH—A hierarchic classification of protein domain structures. Structure 5 1093–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orengo, C.A., Sillitoe, I., Reeves, G., and Pearl, F.M. 2001. Review: What can structural classifications reveal about protein evolution? J. Struct. Biol. 134 145–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei, J., Sadreyev, R., and Grishin, N.V. 2003. PCMA: Fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment based on profile consistency. Bioinformatics 19 427–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebelo, J.M., Dias, J.M., Huber, R., Moura, J.J., and Romao, M.J. 2001. Structure refinement of the aldehyde oxidoreductase from Desulfovibrio gigas (MOP) at 1.28 Å. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 6 791–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, J.S. 1976. Handedness of crossover connections in β sheets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 73 2619–2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell, R.B. 1998. Detection of protein three-dimensional side-chain patterns: New examples of convergent evolution. J. Mol. Biol. 279 1211–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, J., and Brutlag, D. 2004a. FoldMiner and LOCK 2: Protein structure comparison and motif discovery on the web. Nucleic Acids Res. 32 W536–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2004b. FoldMiner: Structural motif discovery using an improved superposition algorithm. Protein Sci. 13 278–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, M.J. and Thornton, J.M. 1977. On the conformation of proteins: The handedness of the connection between parallel β-strands. J. Mol. Biol. 110 269–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, W.R., May, A.C.W., Brown, N.P., and Aszodi, A. 2001. Protein structure: Geometry, topology and classification. Rep. Prog. Phys. 64 517–590. [Google Scholar]

- Truglio, J.J., Theis, K., Leimkuhler, S., Rappa, R., Rajagopalan, K.V., and Kisker, C. 2002. Crystal structures of the active and alloxanthine-inhibited forms of xanthine dehydrogenase from Rhodobacter capsulatus. Structure (Camb.) 10 115–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker, D.R. and Koonin, E.V. 1997. SEALS: A system for easy analysis of lots of sequences. Proc. Int. Conf. Intell. Syst. Mol. Biol. 5 333–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]