Abstract

We have identified a rare HIV-1 protease (PR) mutation, I47A, associated with a high level of resistance to the protease inhibitor lopinavir (LPV) and with hypersusceptibility to the protease inhibitor saquinavir (SQV). The I47A mutation was found in 99 of 112,198 clinical specimens genotyped after LPV became available in late 2000, but in none of 24,426 clinical samples genotyped from 1998 to October 2000. Phenotypic data obtained for five I47A mutants showed unexpected resistance to LPV (86- to >110-fold) and hypersusceptibility to SQV (0.1- to 0.7-fold). Molecular modeling and energy calculations for these mutants using our structural phenotyping methodology showed an increase in the binding energy of LPV by 1.9–3.1 kcal/mol with respect to the wild type complex, corresponding to a 20- to >100-fold decrease in binding affinity, consistent with the observed high levels of LPV resistance. In the WT PR–LPV complex, the Ile 47 side chain is positioned close to the phenoxyacetyl moiety of LPV and its van der Waals interactions contribute significantly to the ligand binding. These interactions are lost for the smaller Ala 47 residue. Calculated binding energy changes for SQV ranged from −0.4 to −1.2 kcal/mol. In the mutant I47A PR–SQV complexes, the PR flaps are packed more tightly around SQV than in the WT complex, resulting in the formation of additional hydrogen bonds that increase binding affinity of SQV consistent with phenotypic hypersusceptibility. The emergence of mutations at PR residue 47 strongly correlates with increasing prescriptions of LPV (Spearman correlation rs=0.96, P<.0001).

Keywords: HIV protease inhibitors, lopinavir, saquinavir, drug resistance, molecular modeling, binding energy, structure-based phenotyping

HIV-1 protease is essential for the cleavage of the viral polyprotein precursor of the gag and pol viral proteins (Kohl et al. 1988; Peng et al. 1989). Anti-viral drugs targeting the active site of HIV-1 protease (PR) are potent inhibitors of viral replication in infected individuals (Deeks et al. 1997; Palella et al. 1998). However, an incomplete suppression of viral replication can lead to the mutation of one or more PR amino acid residues resulting in protease inhibitor resistance. Such mutations have been identified in the HIV-1 patient population for seven commercially available protease inhibitors (PIs) (D’Aquila et al. 2003; Hirsch et al. 2003). The PI lopinavir (coadministered with ritonavir, LPV/r) introduced into clinical use in late 2000 has significant anti-retroviral potency in therapy for drug-naïve and in single-PI experienced patients, (Murphy et al. 2001; Benson et al. 2002; Kempf et al. 2004). Mutations occurring at 11 PR codons (positions 10, 20, 24, 46, 53, 54, 63, 71, 82, 84, and 90) are associated with lopinavir resistance. An increase in the number of mutations accumulated at these positions correlates with increasing resistance to LPV, which is measured as a fold change in phenotypic 50% inhibitory concentration of the drug, IC50 (Kempf et al. 2001, 2002; Voigt et al. 2004). However, individual mutations resulting in LPV resistance are very rare. The PR mutation I47A has been selected in in vitro experiments with increasing concentrations of lopinavir and conferred high-level resistance (Carrillo et al. 1998). Two other clinical variants with high level of lopinavir resistance were also found to have the I47A mutation (Parkin et al. 2003), and a recent case report highlighted the emergence of I47A mutation associated with high-level lopinavir resistance during LPV/r therapy (Friend et al. 2004). In this study, we found five additional clinical PR variants containing the I47A mutation that were highly resistant to LPV and hypersensitive to another PI, saquinavir (SQV).

A number of structure-based or sequence-based computational methods for the prediction of drug resistance have been developed (Cao et al. 2005). Recently we have developed a computational methodology for molecular modeling of PI complexes with mutant PR variants, and for prediction of PR resistance to six commercially available PIs based on changes of binging energy of a PI in the mutant versus WT complexes. In this work, we applied this structure-based phenotyping methodology to develop three-dimensional (3D) models of the mutant I47A PR variants in complex with LPV and SQV. We present structural models for I47A-mediated LPV resistance and for SQV hypersusceptibility, and show that the phenotypic changes can be attributed to changes in free energy of binding of these inhibitors to the mutant I47A PR variants.

Results

Recently we found five clinical HIV-1 PR variants (see Table 1) with a high degree of phenotypic resistance to lopinavir (Fig. 1 ▶) and amprenavir, which was unexpected by genotypic rules-based resistance analysis. These variants were also hypersusceptible to saquinavir (Fig. 1 ▶), showing a fold change in IC50 from 0.1 to 0.7, even though four of the five variants contained the saquinavir resistance PR mutation L90M. The rare I47A mutation was present in the PR sequence of all five variants and we investigated its possible involvement in this unusual phenotype.

Table 1.

Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of five 147A HIV-1 protease variants

| Fold change in phenotypic susceptibilitya | |||||||

| HIV Sample ID | APV | IDV | LPV | NFV | RTV | SQV | PR mutations detected |

| Biological cutoffb | 2.5 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 4.0 | 3.5 | 2.5 | |

| 166701 | 26.4 | 15.1 | >91.5 | 31.0 | 10.9 | 0.3 | K20R, V32I, E35D, M36I, N37D, I47A, I62V, L63P, A71T/A, L90M, I93L |

| 164917 | 13.3 | NA | >102.5 | 5.7 | 0.5 | 0.3 | L10F, T12P, K14R, I15V, G16E, K20T, V32I, E34Q, I47A, I62V, L63H, A71T, V77I, L90M, I93L |

| 165220 | 21.2 | 1.0 | 86.2 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 0.2 | T12P, I13V, N37D, M46L, I47A, R57K, L63P, A71T, V82I |

| 175236 | 7.7 | 2.3 | >109.6 | 7.2 | 5.7 | 0.1 | I13V, V32I, L33F, R41K, K43R, K45R, I47A, L63P, A71T, G73A, V77I, L90M, I93L |

| 175848 | >47.3 | >95.0 | >95.8 | >45.3 | 14.0 | 0.7 | T4A, L10F, I13V, K20T, V32I, L33V, M46I, I47A, I62V, L63P, H69Y, A71V, L89V, L90M, I93L |

a The Antivirogram assay was used to determine phenotypic susceptibility (see Materials and Methods). The results are expressed as a fold change in the mean 50% inhibitory concentration IC50 of each drug relative to a wild-type reference isolate included in each experiment. A HIV-1 PR variant is considered as resistant to a PI if the phenotypic susceptibility ratio exceeds the biological cutoff for the drug. (NA) Not available.

b The biological cutoff is set at two standard deviations above the normal susceptible range for 1000 phenotypic assays performed on viruses from untreated individuals (Harrigan et al. 2001).

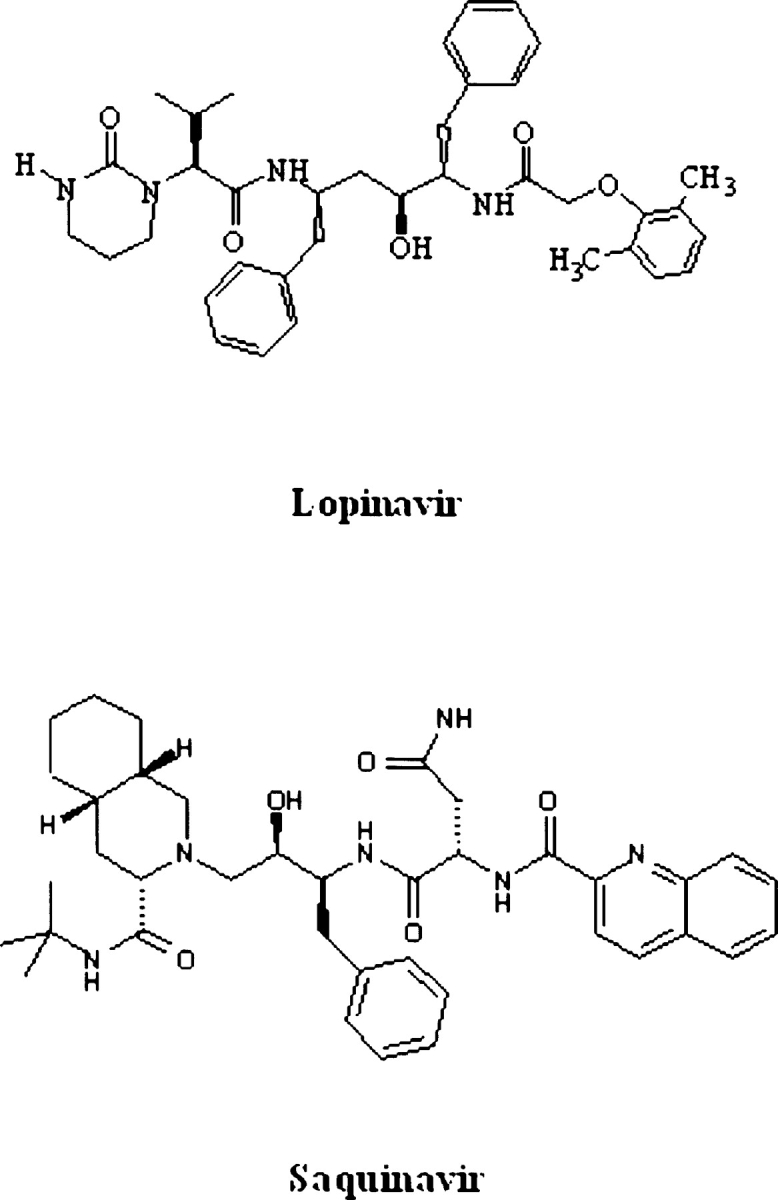

Figure 1.

Structure of HIV-1 protease inhibitors saquinavir (SQV) and lopinavir (LPV).

In the database of HIV-1 PR sequences collected at Quest Diagnostics since 1998, none of 24,427 samples genotyped prior to the fourth quarter of 2000 had the I47A mutation (χ2=20.4, P<7 × 10−6). The first I47A variant appeared in the Quest Diagnostics database in July 2001, nine months after the approval of lopinavir for clinical use. Ninety-nine of 112,198 clinical samples (0.09%) sequenced between the fourth quarter of 2000 and the last quarter of 2004 had the I47A mutation.

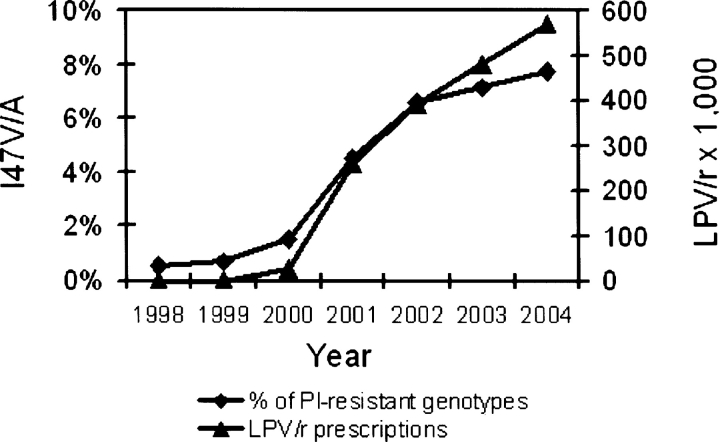

The occurrence of the I47V and I47A mutations (V: n=2021, A: n=99) in viruses with predicted resistance to at least one PI was positively correlated with LPV/r utilization (Fig. 2 ▶), i.e., with the number of the drug doses prescribed in a given period (Spearman correlation rs=0.96, P<9 × 10−8, see Materials and Methods). In contrast, the occurrence of I47V/A mutations was negatively correlated with utilization of other PIs (IDV, NFV, and SQV; rs=−0.95 –−0.97), for which the number of prescriptions has been declining since 1999 (data not shown). Although the I47V mutation has been associated with APV resistance (Maguire et al. 2002; Wu et al. 2003), no correlation was observed between APV utilization and the frequency of I47V/A mutations. Amino acid substitution frequencies at other PI resistance associated positions (10, 20, 24, 30, 32, 48, 71, 82, 84, and 90) did not differ significantly between PR variants containing I47A and I47V mutations. Mutations at position 54, commonly found in PI resistant viruses, were found in 68.3% of the I47V variants but only in 2.7% of the I47A variants.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the percentage of protease resistant viruses containing Val or Ala substitutions in position 47 among the clinical HIV-1 variants submitted for testing between 1998 and 2004 (♦) with the number of LPV/r prescriptions issued for the given period (▴). Only PR variants that were predicted to be resistant at least to one protease inhibitor were included in this analysis.

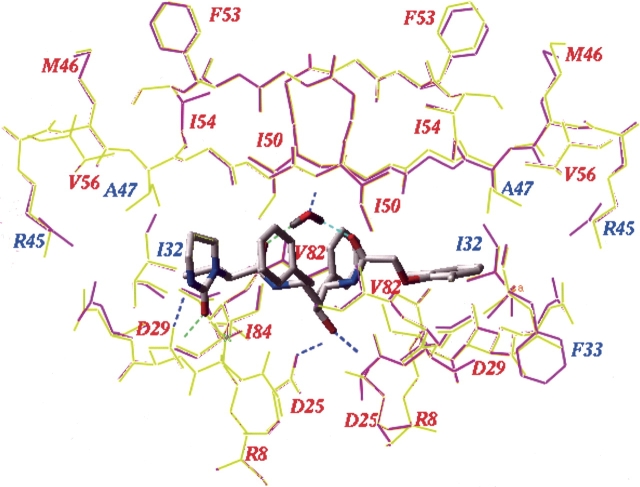

To investigate the role of the I47A mutation in PI resistance at a molecular level, we generated molecular models of all five I47A mutant PR variants (Table 1) in complex with LPV and SQV, and in complex with APV and IDV for two variants, and calculated the changes in binding energy upon mutation (Shenderovich et al. 2001, 2003). The changes in binding energy and its components, as well as experimentally measured and computationally predicted resistances for the I47A variants are given in Table 2. The 3D model of the mutant I47A PR–LPV complexes showed little variation with respect to a refined crystal structure of the wild type PR–lopinavir complex (Fig. 3 ▶). In particular, the RMS deviation of the LPV heavy atoms in the wild type and mutant complexes was <0.1 Å. However, a large increase in the binding energy of LPV was predicted for the I47A variants under study (average ΔEbind= 2.7 ± 0.5 kcal/mol), consistent with a significant loss of binding affinity and high levels of lopinavir resistance (Table 2). In order to estimate specific contributions of the I47A mutation to the changes in binding energy, we also modeled the LPV complexes for the same PR sequences with the native Ile and with a Val mutation at position 47. When Val 47 was substituted for Ala 47 in these models, the binding energy changes from the WT complex for LPV were significantly smaller (average ΔEbind=1.3 ± 0.75 kcal/mol), with a mean difference of −1.4 kcal/mol relative to the respective I47A variants (Table 2). This is consistent with the phenotypic resistance of I47V variants to LPV reported in in vitro selection experiments (Carillo et al. 1998). The changes in binding energy of LPV to the I47A mutants were principally due to the loss of van der Waals interactions (ΔEvw) between the phenoxyacetyl moiety of lopinavir and the side chain of residue 47 in the PR S2′ site (Fig. 3 ▶). Changes in the electrostatic (ΔEel), hydrogen bonding (ΔEhb) or side chain entropy components (ΔEs) of the binding energy function were insignificant (Table 2). Smaller binding energy changes were also predicted for APV and IDV in complex with two I47V variants as compared to the I47A variants (Table 2), which was consistent with a lower median fold change in resistance for V32I+I47V variants compared to V32I+I47A variants observed in a large phenotypic database (Parkin et al. 2004).

Table 2.

Calculated changes in binding energies and experimental and predicted phenotypic ratios of HIV PR variants with substitutions in position 47

| PR inhibitor | Sample ID | Cell-based phenotype (fold)a | ΔEel (kcal/mol) | ΔEvw (kcal/mol) | ΔEhb (kcal/mol) | ΔEs (kcal/mol) | ΔEbind (kcal/mol) | Structural phenotype (fold)b |

| LPV | 164917_1 (47I) | NA | 0.2 | −0.7 | 0.4 | 0.1 | −0.1 | 1 |

| 164917_2(I47V) | NA | 0 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.9 | 6 | |

| 164917_3 (I47A) | >102.5 | 0.3 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 0 | 2.8 | 160 | |

| 165220_1 (I47) | NA | −0.3 | 2.2 | 0.3 | 0 | 2.1 | 44 | |

| 165220s_2 (I47V) | NA | −0.1 | 2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 2.0 | 36 | |

| 165220_3 (I47A) | 86.2 | 0 | 3 | 0.1 | 0 | 3.0 | 224 | |

| 166701_1 (I47) | NA | 0.1 | −0.2 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.2 | 2 | |

| 166701_2 (I47V) | NA | 0.2 | 1.5 | 0.2 | 0 | 1.9 | 31 | |

| 166701_3 (I47A) | >91.5 | 0.2 | 2.7 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 3.1 | 244 | |

| 175236_1 (I47) | NA | 0.2 | −1.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | −0.9 | 0.3 | |

| 175236_2 (I47V) | NA | 0.2 | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.2 | 2 | |

| 175236_3 (I47A) | >109.6 | 0.3 | 1.6 | 0 | 0 | 1.9 | 34 | |

| 175848_1 (I47) | NA | −0.1 | −0.6 | 0.2 | 0.1 | −0.4 | 0.7 | |

| 175848_2 (I47V) | NA | 0.1 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 0 | 1.6 | 21 | |

| 175848_3 (I47A) | >95.8 | 0.2 | 2.3 | 0.3 | 0 | 2.7 | 121 | |

| SQV | 164917_3 (I47A) | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.1 | −1.2 | 0 | −0.6 | 0.5 |

| 165220_3 (I47A) | 0.2 | 0 | −0.3 | −0.2 | 0.1 | −0.4 | 0.6 | |

| 166701_3 (I47A) | 0.3 | 0.5 | −0.1 | −0.9 | 0 | −0.5 | 0.6 | |

| 175236_3 (I47A) | 0.1 | 0.3 | −0.2 | −1.4 | 0.1 | −1.2 | 0.2 | |

| 175848_3 (I47A) | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0 | −1 | 0 | −0.8 | 0.4 | |

| APV | 175236_1 (I47) | NA | −0.1 | 0.2 | −0.1 | 0 | −0.1 | 0.8 |

| 175236_2 (I47V) | NA | 0 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.7 | 2 | |

| 175236_3 (I47A) | 7.7 | −0.1 | 1.1 | 0 | −0.1 | 0.9 | 2 | |

| 175848_1 (I47) | NA | 0.1 | −0.6 | −0.2 | 0 | −0.8 | 0.4 | |

| 175848_2 (I47V) | NA | 0.1 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.1 | 1.3 | 3 | |

| 175848_3 (I47A) | >47.3 | 0.2 | 2.2 | −0.3 | 0 | 2.1 | 8 | |

| IDV | 175236_1 (I47) | NA | −0.2 | 0.3 | −0.2 | 0.1 | 0 | 1 |

| 175236_2 (I47V) | NA | 0.2 | 1.2 | −0.1 | 0 | 1.3 | 4 | |

| 175236_3 (I47A) | 2.3 | −0.2 | 2.8 | −0.1 | 0 | 2.5 | 14 | |

| 175848_1 (I47) | NA | −0.1 | 0.1 | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 175848_2 (I47V) | NA | 0.3 | 1.6 | 0 | 0 | 1.8 | 8 | |

| 175848_3 (I47A) | >95 | 0.4 | 2.5 | −0.1 | 0 | 2.7 | 18 |

Clinical I47A HIV-1 PR variants and their I47- and V47-substituted analogs were modeled in complex with the inhibitors lopinavir (LPV), saquinavir (SQV), amprenavir (APV), and indinavir (IDV).

ΔEbind is the total change in binding energy for a mutant versus WT complex. ΔEel, ΔEvw, ΔEhb, and ΔEs are changes in electrostatic, van der Waals, hydrogen bonding and side-chain entropy components of binding energy (see Equation 2 in Materials and Methods).

a Fold changes in IC50 values in the Antivirogram assay described in Materials and Methods.

b Phenotypic resistance predicted from the PR-drug binding energy changes ΔEbind (Shenderovich et al. 2003).

Figure 3.

Lopinavir complexes with the wild-type HIV-1 PR (a model derived from the crystal structure 1mui) (yellow) and with the 175236 I47A mutant PR variant (magenta). The ligand and the flap water molecule are shown as stick models colored by atom type. Mutated residues are labeled in blue; other important PR residues are labeled in red. Ligand–protein hydrogen bonds are shown as dashed lines, colored by donor–acceptor distance from blue for the shortest H-bonds to green to red for the longer ones.

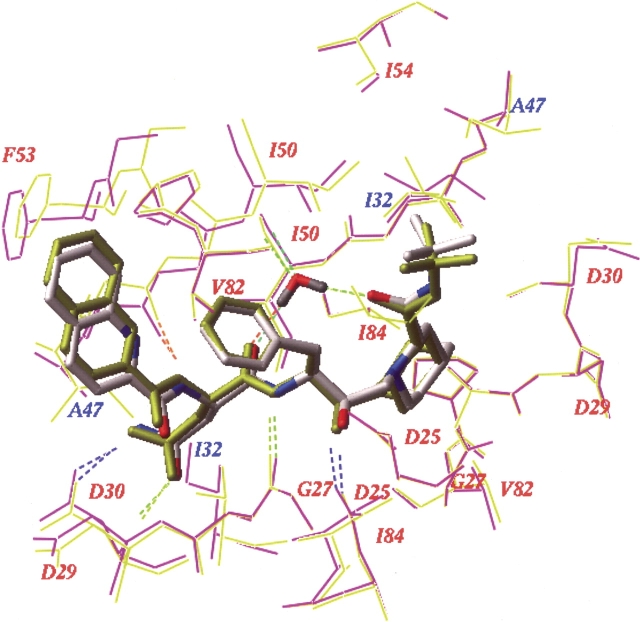

Binding energy changes calculated for the mutant PR–SQV complexes compared with the WT complex were negative, consistent with the apparent phenotypic hypersusceptibility to saquinavir shown by these variants. The greatest change, ΔEbind=−1.2 kcal/mol, was observed for variant 175236; Table 2). Interestingly, the same mutant PR sequence with Ile in position 47 gave ΔEbind=+0.9 kcal/mol (data not shown), which suggests that the net SQV binding energy gain of I47A mutation was about −2.0 kcal/mol. A superposition of the 3D model of mutant I47A PR–SQV complex (variant 175236) with the wild type PR–SQV complex in Figure 5 ▶ (below) shows that substitution of the bulky I47 side chain results in a tighter packing between the PR flap residues 47–50 and saquinavir in the mutant than in the WT complex. The A47 PR variant formed two additional hydrogen bonds with the SQV ligand: between the central hydroxyl (donor) of SQV and the backbone carbonyl (acceptor) of the G27 residue, and between the backbone amide (donor) of the residue D29 and the carbonyl (acceptor) adjacent to the SQV quinoline moiety (Fig. 5 ▶, below).

Figure 5.

Saquinavir complexes with the wild-type HIV-1 PR (model based on the crystal structure 1hxb) (yellow) and with the mutant I47A PR variant 175236 (magenta). The ligands and flap water molecules are shown as stick models, colored by atom type for the mutant complex and in yellow for the WT complex. Mutated residues located close to the ligand are labeled in blue; other important PR residues are labeled in red. Ligand–protein hydrogen bonds are shown colored by donor–acceptor distance from blue for the shortest H-bonds to green to red for the longer ones.

Moderate increases in binding energy obtained for two I47A mutants in complex with APV (Table 2) are consistent with the observed (8- to 47-fold) resistance of these variants. Significant increases in binding energy (ΔEbind ≥ 2.0 kcal/mol) were also predicted for IDV complexes with I47A mutant variants 175236 and 175848 (Table 2). These changes, which are due mainly to the loss of van der Waals interactions of I47, may have contributed to the unusually high level (>95-fold) resistance of variant 175236 to IDV, which is also the only variant in this study with the IDV-resistance mutation M46I (Table 1). However, for all I47A mutant PR variants under study, both calculated changes in binding energy and experimental fold changes in IC50 are higher for LPV than for other PIs.

In order to reveal a possible structural explanation for the absence of mutations at position 54 in most I47A PR variants, we modeled an additional I54 mutation to Val, Leu, or Met in the LPV complexes with PR I47A variants 175236 and 175848 (data not shown). In both variants, I54V/M did not result in a significant change of LPV binding energy, whereas I54L increased the binding energy by about 1.0 kcal/mol mainly due to small conformational changes caused by accommodation of the additional Cγ methyl of L54 in the densely packed flap area (data not shown). Therefore, the presence of I54L/V/M mutations in conjunction with I47A is expected to result in the same or even a moderately increased level of resistance to LPV.

Discussion

It was shown recently that the occurrence of PI resistance correlates with the number of PI prescriptions issued for indinavir, nelfinavir, and saquinavir but not for LPV/r (Kagan et al. 2004). Many of the HIV-1 PR mutations associated with lopinavir resistance may be selected by one or more other PIs in clinical use (Paulsen et al. 2002; Schnell et al. 2003), which complicates identification of the mutations specifically selected by LPV/r in patients with prior PI experience. In this study, we have shown a strong correlation between the emergence of PR mutations at position 47 and the increasing clinical utilization of LPV/r. The alanine substitution in position 47, which confers very high phenotypic levels of LPV resistance, is extremely rare, whereas the valine substitution in the same position is much more common. Although the I47V mutation has been associated with resistance to the PI amprenavir (APV), no correlation was observed between APV prescription utilization and frequency of I47V/A mutations. In HIV-1 subtype B protease, the wild type isoleucine in position 47 is encoded by the codon AUA. A single nucleotide substitution (AUA→GUA) is required for the I47V mutation, whereas two nucleotide substitutions (AUA→GCA) are required for the alanine mutation, which imposes a higher genetic barrier for the emergence of I47A mutants. LPV resistance more commonly requires the accumulation of mutations at multiple PR positions and incremental emergence of resistance (Mo et al. 2005). Such LPV resistance is more likely to arise in PI-experienced patients with existing PR mutations and a lower genetic barrier to LPV resistance (Mo et al. 2005). The I47A variant may also have a high barrier of emergence due to the poor replicative ability of I47A-containing viruses. As was reported in a recent clinical case study, the replicative capacity of the mutant I47A+V32I variant was only 2.9% of WT (Friend et al. 2004), making this a very deleterious mutation that is unlikely to be selected when alternate pathways to resistance exist. Thus, a high genetic barrier and poor replicative capacity may account for the very low prevalence of the I47A mutation in clinical samples. Although the I47A mutation may contribute to IDV and APV resistance, multiple other mutational pathways to the emergence of resistance to these drugs exist that may impose a lower fitness cost than the I47A mutation. The rare I47A mutation was first observed clinically nine months after the introduction of LPV/r into clinical use and its increasing prevalence correlated with the number of LPV/r prescriptions issued. Therefore, these variants may have emerged from pre-existing I47V mutants under positive selective pressure from LPV/r treatment. The emergence of the I47A mutant from an I47V baseline virus in one subject was noted in a recent study (Mo et al. 2005) consistent with this proposed explanation.

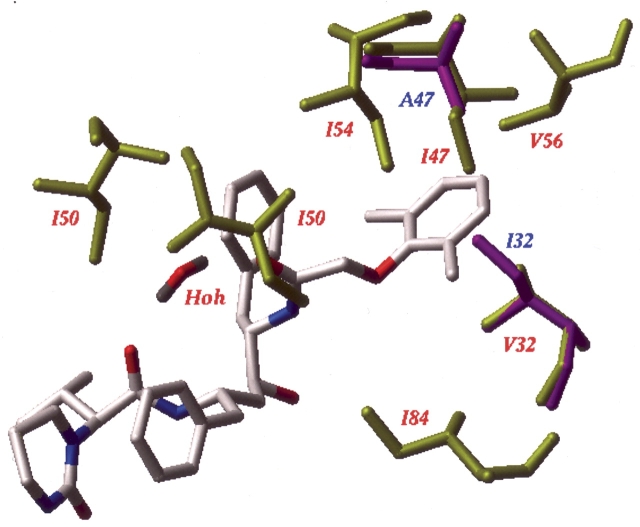

The five mutant I47A variants described here showed large decreases in phenotypic susceptibility to LPV. Results of molecular modeling and binding energy calculations performed in this study suggest that the observed resistance was caused by a decreased binding affinity of LPV to the mutant I47A PR variants due to the loss of specific van der Waals interactions of the Cγ and Cδ atoms of the I47 residue located in the protease S2′ subsite with ring atoms of the phenoxyacetyl moiety of lopinavir (Fig. 4 ▶). This caused an average 2.7 ± 0.5 kcal/mol increase in binding energy of LPV to I47A mutants. Molecular modeling and binding energy calculations showed also that the observed phenotypic hypersusceptibility of the I47A variant to saquinavir was attributable to tighter packing and additional hydrogen bonding between SQV and the backbone of G27 and D29 residues in the mutant PR variant (Fig. 5 ▶). Previously (Shenderovich et al. 2003), we found good correlations between calculated changes in binding energy and experimental estimates from IC50 ratios observed both for LPV and for SQV with standard errors in predicted binding energies of about 0.5 kcal/mol for both PIs. ΔEbind values calculated in this study for LPV complexes with five mutant I47A PR variants were well above the confidence level of two standard errors required for reliable resistance predictions. Although moderate decreases in binding energy were calculated for SQV complexes with all PR mutants under study, only variant 175236 gave ΔEbind value −1.2 kcal/mol sufficient for a reliable prediction of hypersensitivity. It is noteworthy that the same PR variant had shown the highest susceptibility to SQV in the phenotypic assay. SQV is the only PI in this study that shows a unique interaction pattern with PR flaps. The quinoline moiety of SQV interacts strongly with the backbone of flap residues 47–49 and with the I50 side chain (Shenderovich et al. 2003), but it does not interact directly with the side chain in position 47. Mutation G48V produces strong resistance to SQV but has a rather small affect on the other PIs (Maschera et al. 1996). This study reveals another mutation, I47A that has opposite effect on PR sensitivity to SQV and to other PIs. In contrast to G48V mutants, mutation in position 47 affects SQV binding indirectly via conformational changes that enhance the ligand interactions elsewhere in the PR binding site.

Figure 4.

Interaction of the Lopinavir phenoxyacetyl moiety with the S2′ site of wild-type PR and of the I47A mutant PR variant 175236. The ligand and the flap water molecule are shown as stick models colored by atom type. Wild-type PR residues surrounding the phenoxyacetyl moiety are shown as yellow sticks and labeled in red. V32 and A47 residues of the mutant PR are shown as magenta sticks and labeled in blue.

Molecular modeling and cell-based phenotypic assay data show that PR binding affinity and sensitivity to inhibitors other than LPV also may be affected by the I47A mutation. However, for all HIV-1 PR variants under study, both predicted changes in binding energy and observed phenotypic resistance were higher for LPV than for any other PR inhibitor.

The I47A PR variants show resistance to APV, which is consistent with the increase in calculated binding energies (Table 2). The model of WT PR–APV complex used in this study shows close van der Waals contacts of the Cδ methyl group of I47 in PR chain A with aromatic meta and para carbons of the benzene ring in APV position P2′. Loss of these interactions upon I47V mutation accounts for about 1.0 kcal/mol increase in binding energy, which is consistent with known phenotypic resistance of I47V PR variants to APV (Maguire et al. 2002). In addition, the Cγ2 methyl of I47 in PR chain B interacts with carbons of the tetrahydrofuran ring in APV position P2. This interaction is lost in I47A mutants, which accounts for the additional increase in calculated binding energy, and possibly increases resistance of I47A mutants to APV. An even higher increase in binding energy upon mutation at position 47 was predicted for IDV (Table 2). In the model of WT PR–IDV complex, the Cγ and Cδ carbons of I47 in the PR chain A strongly interact with the aromatic ring of the IDV indanyl moiety, and a Cδ methyl of I47 in PR chain B contacts the IDV t-butyl group. These interactions, which account for about 2.0 kcal/mol increase in binding energy, are diminished in I47V mutants, and they are completely lost in I47A PR variants. Indeed, some of the mutant I47A PR variants under study show amoderate (variant 166701) or even strong (variant 175848) resistance to IDV.

The I47 side chain is an important element of the HIV-1 PR S2/S2′ substrate binding subsites that also include the V32, I50, and I54 residues which form continuous hydrophobic patches. I47 is directly involved in interaction with PR substrates (Prabu-Jeyabalan et al. 2000). The loss of six carbon atoms on the substitution of alanine for isoleucine at position 47 in both PR chains significantly decreases the substrate binding affinity that may explain the significant reduction in the replicative capacity of I47A viruses. This effect may be compensated in part by the V32I mutation, which does not affect LPV binding but may provide additional favorable interactions with substrates.

In the crystal structure of wild type PR–LPV complex, the Cγ1-Cδ1 branch of the I54 side chain is tightly packed between the Cγ atoms of I47 and V56 in the same PR polypeptide chain and of I50 in the second chain of the PR homodimer (Fig. 4 ▶) making six favorable contacts with carbon–carbon distances less than 4.0 Å. These interactions of the I54 side chain contribute to stabilization of a closed conformation of the protease flap loops that may be important for PR enzymatic activity. The I47V mutation should not influence stability of the protein, as the missing Cδ methyl does not contribute much to the above interactions. Indeed, the median replicative capacity of I47V+V32I viruses was observed to be 90% of that for WT PR (Parkin et al. 2004). However, the I47A mutant loses the favorable interactions with I54, thereby reducing both the ligand affinity and the conformational stability of the flap region. Mutation V32I that frequently accompanies I47A may compensate for the loss in protein stability by creating additional interaction between the Cδ methyls of I32 and I54. An additional I54V mutation may further decrease the conformational stability of the flaps by elimination of favorable contacts with I32 and I50. As was shown by thermodynamic measurements on mutant proteins, removal of one methylene group from the protein interior may destabilize a protein by 1.2 kcal/mol (Pace et al. 1996; Loladze et al. 2002). A cumulative effect of elimination of six carbons in position 47 and two carbons in position 54 on stability of the PR flap region may be especially significant. On the other hand, the longer L54 or M54 side chains may not fit well into the space available between the I32, A47, and I50 side chains. Therefore, mutations in position 54 are expected to be unfavorable in an I47A PR background. These considerations may explain why mutations in position 54 that are common in PI resistant viruses rarely appear in combination with I47A mutations.

Conclusions

We have recently developed a computational protocol for molecular modeling and binding energy evaluation of mutant PR–inhibitor complexes, and a structure-based approach for predicting changes in susceptibility of clinical HIV-1 PR variants to protease inhibitors (Shenderovich et al. 2003). In this study, data mining of the Quest Diagnostics HIV sequence database uncovered the rare protease mutation I47A, which is associated with high-level resistance to the protease inhibitor lopinavir. This mutation has not been detected before LPV/r became clinically available, and the prevalence of I47A, together with its likely precursor, I47V, strongly correlates with LPV/r utilization. We have applied our computational methodology to show that the primary reason for the mutant I47A PR loss of susceptibility to LPV is a significant decrease in the mutant PR–LPV binding energy. We have also explained the observed hypersusceptibility of the I47A mutants to the PI saquinavir by a tighter packing and additional hydrogen bonding of the ligand to the mutant PR.

Resistance to lopinavir and hypersusceptibility to saquinavir in a clinical HIV-1 sample with an I47A PR variant was recently reported (Friend et al. 2004). Replacement of LPV with SQV in the regimen of this patient resulted in a complete restoration of virologic response with plasma HIV-1 RNA levels dropping to an undetectable level six months after the switch (Parkin et al. 2004). Such clinical data help to establish the validity of our computational approach for characterizing emerging PR mutations. Continued surveillance of large clinical mutation databases may facilitate the identification of new mutational patterns specifically associated with the utilization of particular HIV protease inhibitors, while the structure-based resistance prediction may help to identify the protease inhibitors that would retain anti-viral activity against the emerging HIV mutants.

Materials and methods

Sequence analysis and phenotyping

HIV-1 RNA was extracted from plasma samples submitted for RT and PR genotype determination by Quest Diagnostics Nichols Institute. A 2.2-Kb amplicon encompassing codons 1–99 of the PR gene and 1–400 of the RT gene were amplified by reverse transcription PCR followed by nested PCR using primers described in a previous publication (Hertogs et al. 1998). BigDye (Applied Biosystems) dye terminator sequencing reactions were resolved on an ABI 3700 capillary sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Sequence data was assembled and compared to the subtype B consensus sequence (Los Alamos database) using Sequencher software (Genecodes Corp.). Anti-virogram HIV-1 phenotype assays were carried out by Virco BVBA as described previously (Hertogs et al. 1998, with modifications described by Pauwels et al. 1998). Briefly, a patient-derived viral RNA-derived amplicon encompassing protease codons 1–99 and RT codons 1–400 was homologously recombined into a PR–RT deleted proviral clone. The viruses were used for in vitro susceptibility testing and the results are expressed as a fold change in the mean IC50 (μM) of each drug relative to a wild-type reference isolate included in each experiment.

Genotypic resistance interpretation

Predicted drug resistances were determined according to the Quest-Stanford rules-based interpretive system (Quest Diagnostics Inc.), an updated version of the GART study algorithm (Baxter et al. 2000; T.C. Merigan and M. Winters, pers. comm.). The interpretive rules used in this laboratory-developed algorithm are based on mutations the laboratory considered to be associated with resistance to anti-retroviral drugs based on current clinical or laboratory-based studies.

Data analysis

De-identified clinical mutation data were stored in a relational database (Sybase Adaptive Server 11.5, Sybase). Anti-retroviral drug utilization data was obtained from Scott Levin Source Prescription Audit. Spearman correlations and chi-square tests were performed with Analyse-it for Microsoft Excel (Analyse-it Software Ltd.).

Molecular modeling and binding energy calculations

Chemical structure of protease inhibitors LPV and SQV are shown in Figure 1 ▶. Molecular models of the wild-type HIV- 1 PR–inhibitor complexes were built, starting from the crystal structures 1hxb for SQV, 1mui for LPV, 1hsg for IDV, and 1hpv for APV. Molecular modeling and simulations were performed using the ICM program (Abagyan et al. 1994), version 2.8 (MolSoft LLC). Modeling of WT and mutant HIV PR–inhibitor complexes and binding energy calculations for PR–inhibitor complexes was performed as previously described (Shenderovich et al. 2001, 2003). Briefly, crystal structures of WT complexes were regularized with the ECEPP/3 force field and amino acid geometry (Némethy et al. 1992), and positions of the ligands and the PR binding site side chains were optimized by Monte Carlo simulations with Minimization (Abagyan and Totrov 1994). Amino acid mutations were individually introduced into refined structures of WT complexes in the order of increasing distance of the mutated residues from the ligand. Each mutant side chain was locally optimized by a systematic search procedure (MolSoft LLC) applied to χ torsion angles not common for the WT and the mutant side chains, which generated all combinations of three rotamers (±60° and 180°) for the torsion angles involved, minimized energy of each combination, and selected the lowest-energy conformation. The minimization involved all χ angles of the side chains located in a 5.0 Å shell around the mutant residue. Then, energy minimization was performed for a substructure including the ligand, PR residues, and water molecules in a 7.0 Å shell around the ligand. The minimized energy function included ECEPP/3 van der Waals, hydrogen bonding, and torsion potentials (Némethy et al. 1992), electrostatic potentials with a distance- dependent dielectric ɛ = 4.0rij, side chain entropy and atomic solvation energy (Abagyan and Totrov 1994). Molecular variables of the mutant complex included translation and rotation variables of the ligand and water molecules, torsion angles of the ligand, and backbone and side chain torsion angles of PR residues located in a 7.0 Å shell around the ligand. Minimization was performed by a combination of conjugated gradient and quasi-Newton methods for a maximum of 5000 iterations. It was terminated when RMS of the energy gradient was less than 0.05.

Binding energies of PR–inhibitor complexes were estimated (Schapira et al. 1999; Shenderovich et al. 2003) as

|

(1) |

where E0 is a constant proportional to the number of rotatable bonds in the ligand, Ecompl is the energy of the complex, and Eligand and Eprot are the energies of the ligand and protein when separated. The components of the binding energy were calculated using the energy function with an electrostatic term different from that used for the complex optimization

|

(2) |

where Eel is the exact-boundary electrostatics (Totrov and Abagyan 2001) that accounts both for the Coulomb interactions and for Poisson desolvation energy calculated with a protein internal dielectric constant ɛ = 8.0 (Schapira et al. 1999), Es is the side-chain entropy (Abagyan and Totrov 1994), and Evw and Ehb are the ECEPP/3 van der Waals and hydrogen-bonding terms. As the main aim of these calculations was to estimate differences in binding energy of the same ligand in complex with WT and mutant PR, the proteins and ligands were not minimized separately.

The changes in binding energy of PR inhibitors upon PR mutations calculated as ΔEbind(calc)=Ebind(wt) − Ebind(mut) were shown to correlate with experimentally measured changes in binding energy ΔEbind(exptl)=RTln(IC50mut/IC50wt) for six PR inhibitors (Shenderovich et al. 2001, 2003). For experimental IC50 ratios obtained from the PhenoSense resistance assay (ViroLogic Inc.), the correlation coefficients R2 were 0.81 and 0.83 for LPV and SQV, respectively, with a standard error of about 0.5 kcal/mol for both PR inhibitors.

Abbreviations

3D, three-dimensional

HIV-1, human immunodeficiency virus type 1

ARV, anti-retroviral

APV, amprenavir

IDV, indinavir

LPV, lopinavir

LPV/r, lopinavir coadministered with ritonavir

NFV, nelfinavir

SQV, saquinavir

PI, protease inhibitor

PR, protease

WT, wild type.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.051347405.

References

- Abagyan, R. and Totrov, M. 1994. Biased probability Monte Carlo conformational searches and electrostatic calculations for peptides and proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 235 983–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abagyan, R., Totrov, M., and Kuznetsov, D. 1994. ICM A new method for protein modeling and design: Applications to docking and structure prediction from the disorded red native conformation. J. Comput. Chem. 15 488–506. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, J.D., Mayers, D.L., Wentworth, D.N., Neaton, J.D., Hoover, M.L., Winters, M.A., Mannheimer, S.B., Thompson, M.A., Abrams, D.I., Brizz, B.J., et al. 2000. A randomized study of antiretroviral management based on plasma genotypic antiretroviral resistance testing in patients failing therapy. CPCRA 046 Study Team for the Terry Beirn Community Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS. AIDS 14 F83–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson, C.A., Deeks, S.G., Brun, S.C., Gulick, R.M., Eron, J.J., Kessler, H.A., Murphy, R.L., Hicks, C., King, M., Wheeler, D., et al. 2002. Safety and antiviral activity at 48 weeks of lopinavir/ritonavir plus nevirapine and 2 nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected protease inhibitor-experienced patients. J. Infect. Dis. 185 599–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z.H., Han, L.Y., Zheng, C.J., Lang, Z., Chen, J.X., Lin, H.H., and Chen, Y.Z. 2005. Computer prediction of drug resistance mutations in proteins. Drug Discov. Today 10 521–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo, A., Stewart, K.D., Sham, H.L., Norbeck, D.W., Kohlbrenner, W.E., Leonard, J.M., Kempf, D.J., and Molla, A. 1998. In vitro selection and characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants with increased resistance to ABT-378, a novel protease inhibitor. J. Virol. 72 7532–7541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Aquila, R.T., Schapiro, J.M., Brun-Vézinet, F., Clotet, B., Conway, B., Demeter, L.M., Grant, R.M., Johnson, V.A., Kuritzkes, D.R., Loveday, C., et al. 2003. Drug resistance mutations in HIV-1. Top. HIV. Med. 11 92–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeks, S.G., Smith, M., Holodniy, M., and Kahn, J.O. 1997. HIV-1 protease inhibitors. A review for clinicians. JAMA 277 145–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friend, J., Parkin, N., Liegler, T., Martin, J.M., and Deeks, S.G. 2004. Isolated lopinavir resistance after virologic rebound of a ritonavir/lopinavir-based regimen. AIDS 18 1965–1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrigan, P.R., Montaner, J.S., Wegner, S.A., Verbiest, W., Miller, V., Wood, R., and Larder, B.A. 2001. World-wide variation in HIV-1 phenotypic susceptibility in untreated individuals: Biologically relevant values for resistance testing. AIDS 15 1671–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertogs, K., de Bethune, M.P., Miller, V., Ivens, T., Schel, P., Van Cauwenberge, A., Van Den Eynde, C., Van Gerwen, V., Azijn, H., Van Houtte, M., et al. 1998. A rapid method for simultaneous detection of phenotypic resistance to inhibitors of protease and reverse transcriptase in recombinant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates from patients treated with antiretroviral drugs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42 269–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, M.S., Brun-Vezinet, F., Clotet, B., Conway, B., Kuritzkes, D.R., D’Aquila, R.T., Demeter, L.M., Hammer, S.M., Johnson, V.A., Loveday, C., et al. 2003. Antiretroviral drug resistance testing in adults infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1: 2003 recommendations of an International AIDS Society-USA Panel. Clin. Infect. Dis. 37 113–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan, R., Winters, M., Merigan, T., and Heseltine, P. 2004. HIV type 1 genotypic resistance in a clinical database correlates with antiretroviral utilization. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 20 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempf, D.J., Isaacson, J.D., King, M.S., Brun, S.C., Xu, Y., Real, K., Bernstein, B.M., Japour, A.J., Sun, E., and Rode, R.A. 2001. Identification of genotypic changes in human immunodeficiency virus protease that correlate with reduced susceptibility to the protease inhibitor lopinavir among viral isolates from protease inhibitor-experienced patients. J. Virol. 75 7462–7469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempf, D.J., Isaacson, J.D., King, M.S., Brun, S.C., Sylte, J., Richards, B., Bernstein, B., Rode, R., and Sun, E. 2002. Analysis of the virological response with respect to baseline viral phenotype and genotype in protease inhibitor-experienced HIV-1-infected patients receiving lopinavir/ritonavir therapy. Antivir. Ther. 7 165–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempf, D.J., King, M.S., Bernstein, B., Cernohous, P., Bauer, E., Moseley, J., Gu, K., Hsu, A., Brun, S., and Sun, E. 2004. Incidence of resistance in a double-blind study comparing lopinavir/ritonavir plus stavudine and lamivudine to nelfinavir plus stavudine and lamivudine. J. Infect. Dis. 189 51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl, N.E., Emini, E.A., Schleif, W.A., Davis, L.J., Heimbach, J.C., Dixon, R.A., Scolnick, E.M., and Sigal, I.S. 1988. Active human immunodeficiency virus protease is required for viral infectivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 85 4686–4690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loladze, V.V., Ermolenko, D.N., and Makhatadze, G.I. 2002. Thermodynamic consequences of burial of polar and non-polar amino acid residues in the protein interior. J. Mol. Biol. 320 343–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, M., Shortino, D., Klein, A., Harris, W., Manohitharajah, V., Tisdale, M., Elston, R., Yeo, J., Randall, S., Xu, F., et al. 2002. Emergence of resistance to protease inhibitor amprenavir in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected patients: Selection of four alternative viral protease genotypes and influence of viral susceptibility to coadministered reverse transcriptase nucleoside inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46 731–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maschera, B., Darby, G., Palu, G., Wright, L.L., Tisdale, M., Myers, R., Blair, E.D., and Furfine, E.S. 1996. Human immunodeficiency virus. Mutations in the viral protease that confer resistance to saquinavir increase the dissociation rate constant of the protease-saquinavir complex. J. Biol. Chem. 271 33231–33235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo, H., King, M.S., King, K., Molla, A., Brun, S., and Kempf, D.J. 2005. Selection of resistance in protease-experienced, Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1-infected subjects failing lopinavir- and ritonavir-based therapy: Mutation patterns and baseline correlates. J. Virol. 79 3329–3338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, R.L., Brun, S., Hicks, C., Eron, J.J., Gulick, R., King, M., White Jr., A.C., Benson, C., Thompson, M., Kessler, H.A., et al. 2001. ABT-378/ritonavir plus stavudine and lamivudine for the treatment of antiretroviral-naive adults with HIV-1 infection: 48-week results. AIDS 15 F1–F9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Némethy, G., Gibson, K.D., Palmer, K.A., Yoong, C.N, Paterlini, G., Zagari, A., Rumsey, S., and Scheraga, H.A. 1992. Energy parameters in polypeptides. 10. Improved geometrical parameters and nonbonded interactions for use in the ECEPP/3 algorithm, with application to proline-containing peptides. J. Phys. Chem. 96 6472–6484. [Google Scholar]

- Pace, C.N., Shirley, B.A., McNutt, M., and Gajiwala, K. 1996. Forces contributing to the conformational stability of proteins. FASEB J. 10 75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palella Jr., F.J., Delaney, K.M., Moorman, A.C., Loveless, M.O., Fuhrer, J., Satten, G.A., Aschman, D.J., and Holmberg, S.D. 1998. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 338 853–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkin, N.T., Chappey, C., and Petropoulos, C.J. 2003. Improving lopinavir genotype algorithm through phenotype correlations: Novel mutation patterns and amprenavir cross-resistance. AIDS 17 955–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkin, N.T., Petropoulos, C.J., Chappey, C., Friend, J., Liegler, T., Martin, J.N., and Deeks, S.G. 2004. Isolated lopinavir resistance after virological rebound of a lopinavir/ritonavir-based regimen. Antiviral Therapy 9 S79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen, D., Liao, Q., Fusco, G., St. Clair, M., Shaefer, M., and Ross, L. 2002. Genotypic and phenotypic cross-resistance patterns to lopinavir and amprenavir in protease inhibitor-experienced patients with HIV viremia. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 18 1011–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauwels, R., Hertogs, K., Kemp, S., Bloor, S., Van Ackerk, K., Hansen, J., De Beukeleer, W., Roelant, C., Larder, B., and Stoffels, P. 1998. Comprehensive HIV drug resistance monitoring using rapid, high-throughput phenotypic and genotypic assays with correlative data analysis. In 2nd International Workshop HIV Drug Resistance, Treatment Strategies, June 1998, abstract 51. Lake Maggiore, Italy.

- Peng, C., Ho, B.K., and Chang, N.T. 1989. Role of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific protease in core protein maturation and viral infectivity. J. Virol. 63 2550–2556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabu-Jeyabalan, M., Nalivaika, E., and Schifer, C.A. 2000. How does a symmetric dimmer recognize an asymmetric substrate? A substrate complex of HIV-1 protease. J. Mol. Biol. 301 1207–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnell, T., Schmidt, B., Moschik, G., Thein, C., Paatz, C., Korn, K., and Walter, H. 2003. Distinct cross-resistance profiles of the new protease inhibitors amprenavir, lopinavir, and atazanavir in a panel of clinical samples. AIDS 17 1258–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schapira, M., Totrov, M., and Abagyan, R. 1999. Prediction of the binding energy for small molecules, peptides and proteins. J. Mol. Recognit. 12 177–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenderovich, M., Ramnarayan, K., Kagan, R., and Hess, P. 2001. Structural pharmacogenomic approach to the evaluation of drug resistant mutations in HIV-1 protease. J. Clin. Ligand Assay 24 140–144. [Google Scholar]

- Shenderovich, M.D., Kagan, R.M., Heseltine, P.N.R., and Ramnarayan, K. 2003. Structure-based phenotyping predicts HIV-1 protease inhibitor resistance. Protein Sci. 12 1706–1718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Totrov, M. and Abagyan, R. 2001. Rapid boundary element solvation electrostatics calculations in folding simulations: Successful folding of a 23-residue peptide. Biopolymers (Pept. Sci.) 60 124–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voigt, E., Wasmuth, J.C., Vogel, M., Mauss, S., Schmutz, G., Kaiser, R., and Rockstroh, J.K. 2004. Safety, efficacy, and development of resistance under the new protease inhibitor lopinavir/ritonavir: 48-week results. Infection 32 82–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.D., Schiffer, C.A., Gonzales, M.J., Taylor, J., Kantor, R., Chou, S., Israelski, D., Zolopa, A.R., Fessel, W.J., and Shafer, R.W. 2003. Mutation patterns and structural correlates in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease following different protease inhibitor treatments. J. Virol. 77 4836–4847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]