Abstract

We investigated the relative importance of sociodemographic factors and psychiatric disorders for smoking among 453 pregnant women in the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Women with less than a high school education and those with current-year nicotine dependence had the highest risk of smoking (90.5%), compared with women with a college degree and without nicotine dependence (3.9%). More effective and accessible interventions for nicotine dependence among pregnant smokers are needed.

Maternal smoking during pregnancy increases the risk of birth complications1–3 and has long-term developmental consequences for child development, including deficits in general intelligence, academic skills, and cognitive functioning.4–7 As social inequalities in smoking have increased over time,8,9 maternal smoking during pregnancy has become concentrated among women with lower levels of education (e.g., more than 20% among women without a high school degree).10–14 In part, the relationship between education and continued smoking is attributable to nicotine dependence, which remains the most prominent obstacle to smoking cessation15–19 and is associated with lower education.20

Smoking during pregnancy may also be related to worse maternal mental health.21–25 However, this evidence is not entirely consistent26–28 and is based predominantly on clinical samples with above-average rates of psychopathology. In the general population, mood, anxiety, and substance-use disorders predict smoking initiation and persistence,29,30 which suggests that treatment of maternal mental disorders (e.g., antidepressant pharmacotherapy or cognitive behavioral mood management) may promote smoking cessation and reduce fetal exposure to tobacco.24,25,31 However, whether the focus of treatment should be on aspects of smoking behavior; symptoms of nicotine dependence32–34; symptoms of concomitant mood, anxiety, or substance disorders; or a combination of these remains unresolved. We examined the independent associations of educational attainment, nicotine dependence, and common psychiatric disorders with maternal smoking during pregnancy.

METHODS

We used data from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC; available at http://niaaa.census.gov), a representative household survey of the US population fielded in 2001 and 2002 by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.35 The final response rate was 81.2%, which resulted in a sample size of 43 093 participants. Sampling weights adjusted for selection and response probabilities.35,36 Our study included 453 female NESARC participants aged 18 to 50 years who were pregnant at the time of interview.

Smoking during pregnancy was coded positive if participants reported having smoked cigarettes during the 24 hours that preceded the interview. Socioeconomic and demographic factors included in the analyses were tertiles of age, self-reported race/ethnicity, educational attainment, marital status, employment status, and family income. Psychiatric disorders were assessed with the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV,37 a structured interview that yields Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Revised Fourth Edition, diagnoses of psychopathology.38–40 We analyzed 2 classes of psychopathology: current-year mood or anxiety disorders (major depression, dysthymia, bipolar disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, specific phobia, generalized anxiety disorder) and current-year substance-use disorders (alcohol or drug abuse and dependence). We also investigated 2 aspects of smoking history that have previously been associated with maternal smoking during pregnancy: onset of daily smoking by age 14 years41 and heavy smoking, defined as smoking at least 1 pack of cigarettes per day in the year preceding the interview.42

We used Poisson regression with robust error variance to obtain prevalence ratios for smoking during pregnancy, which indicated the relative increase or decrease in the probability of smoking compared with the reference level of each covariate.43,44 We estimated 4 models: 1 for socioeconomic and demographic covariates, 1 that added indicators of psychiatric disorders, and 2 models that added nicotine dependence and participants’ smoking history. The third model was estimated among participants who reported a lifetime history of daily smoking, and the fourth model was estimated among participants who smoked in the 12 months prior to the interview. Analyses were conducted with the LOGLINK procedure in SUDAAN (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC). Unweighted sample sizes are presented along with corresponding weighted percentages.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the 453 pregnant women in the NESARC are presented in the first column of Table 1 ▶; 12.3% (n = 50) reported smoking within the previous 24 hours. The second column in Table 1 ▶ shows the prevalence of smoking for each category of risk factors. Smoking was more prevalent among participants with a less than high-school education, Whites and Blacks compared with other racial/ethnic groups, and those who were unmarried, unemployed, and had lower household income. Smoking was also more likely among women who met diagnostic criteria for a current-year mood or anxiety disorder, current-year alcohol or substance use disorder, and current-year nicotine dependence. Among lifetime daily smokers, the prevalence of smoking during pregnancy was markedly higher among individuals with current-year nicotine dependence, early smoking onset, and heavy cigarette consumption.

TABLE 1—

Risk Factors for Maternal Smoking During Pregnancy: National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, 2001–2002

| Regression Analyses of Smoking During Pregnancya | ||||||

| Sample Distribution,b % (No.)c | Prevalence of Smoking DuringPregnancy, % (No.)c | Model 1, PR (95% CI) | Model 2, PR (95% CI) | Model 3,d PR (95% CI) | Model 4,e PR (95% CI) | |

| Demographic factors | ||||||

| Age, y | ||||||

| 18–23 | 28.1 (131) | 16.7 (20) | 0.86 (0.31, 2.38) | 0.80 (0.28, 2.30) | 1.16 (0.63, 2.16) | 1.14 (0.62, 2.11) |

| 24–30 | 39.6 (172) | 15.1 (20) | 1.64 (0.74, 3.66) | 1.47 (0.66, 3.30) | 1.64 (0.98, 2.75) | 1.54 (0.92, 2.57) |

| ≥ 31 (Reference) | 32.2 (150) | 5.2 (10) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Black | 14.3 (93) | 15.6 (13) | 0.52 (0.28, 0.96) | 0.58 (0.32, 1.05) | 1.26 (0.82, 1.95) | 1.27 (0.86, 1.89) |

| Other | 26.3 (154) | 2.4 (4) | 0.11 (0.03, 0.38) | 0.12 (0.03, 0.42) | 0.46 (0.14, 1.52) | 0.48 (0.15, 1.55) |

| White (Reference) | 59.4 (206) | 16.0 (33) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Educational attainment | ||||||

| Less than high school | 15.4 (82) | 36.0 (18) | 7.87 (3.20, 19.38) | 8.67 (3.45, 21.81) | 2.16 (1.25, 3.73) | 1.99 (1.22, 3.25) |

| GED or high school degree | 29.1 (139) | 15.2 (22) | 2.80 (1.07, 7.36) | 2.93 (1.14, 7.52) | 1.17 (0.69, 1.96) | 1.13 (0.68, 1.90) |

| Some college or more (Reference) | 55.5 (232) | 4.3 (10) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Not married | 18.8 (117) | 29.8 (27) | 2.52 (1.43, 4.45) | 2.28 (1.32, 3.95) | 1.46 (0.95, 2.24) | 1.36 (0.94, 1.96) |

| Married (Reference) | 81.2 (336) | 8.3 (23) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Employment status | ||||||

| Unemployed, student, not in labor force | 5.1 (22) | 39.3 (7) | 0.95 (0.55, 1.65) | 0.93 (0.52, 1.67) | 0.77 (0.51, 1.16) | 0.79 (0.54, 1.15) |

| Employed (Reference) | 94.9 (431) | 10.9 (43) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Household income | ||||||

| < 150% of the US poverty level | 31.6 (153) | 18.7 (28) | 1.91 (0.92, 3.93) | 1.84 (0.93, 3.65) | 1.28 (0.90, 1.83) | 1.27 (0.92, 1.76) |

| < Median income ($40 000) | 23.3 (117) | 13.4 (12) | 1.45 (0.61, 3.42) | 1.27 (0.52, 3.11) | 1.11 (0.66, 1.87) | 1.11 (0.67, 1.85) |

| ≥ Median income ($40 000) (Reference) | 45.2 (183) | 7.4 (10) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Psychiatric and substance disorders | ||||||

| Mood or anxiety disorder (current year) | ||||||

| Yes | 18.0 (89) | 22.1 (16) | 1.18 (0.67, 2.06) | 0.67 (0.41, 1.07) | 0.69 (0.43, 1.10) | |

| No (Reference) | 82.0 (364) | 10.2 (34) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Alcohol or substance disorder (current year) | ||||||

| Yes | 3.7 (17) | 42.1 (7) | 2.74 (1.32, 5.69) | 0.98 (0.65, 1.47) | 0.98 (0.66, 1.46) | |

| No (Reference) | 96.3 (436) | 11.2 (43) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Nicotine dependence (current year) | ||||||

| Yes | 4.68 (1.96, 11.16) | 2.63 (1.25, 5.54) | ||||

| No (Reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Smoking history (among lifetime daily smokers) | ||||||

| Onset of daily smoking by age 14 years | ||||||

| Yes | NA | 71.0 (17) | 1.51 (0.99, 2.30) | 1.62 (1.06, 2.46) | ||

| No (Reference) | NA | 40.0 (32) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Smoke ≥ 1 pack/day (current year) | ||||||

| Yes | NA | 64.3 (21) | 1.00 (0.65, 1.52) | 0.93 (0.63, 1.37) | ||

| No (Reference) | NA | 32.2 (28) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

Notes. PR =prevalence ratio; CI = confidence interval; GED = general equivalency diploma; NA = not applicable.

aResults from Poisson regression models. Regression coefficients, when exponentiated, are interpreted as prevalence ratios.

bSample of 453 pregnant women; number who smoked today = 50 (weighted percent = 12.3).

cWeighted percentages and actual sample sizes are given.

dEstimated among the sample of 122 lifetime daily smokers.

eEstimated among the sample of 92 current-year smokers.

When analyzed together, only race/ethnicity, a less than high school education, and marital status were significantly associated with smoking (model 1). The strongest effect was for educational attainment: compared with those who had some college education or more, the risk of smoking was 7.87 times higher (95% confidence interval [CI] = 3.20, 19.38) among women with a less than high school education and 2.80 times higher (95% CI = 1.07, 7.36) among women with a general equivalency diploma or high school degree.

When psychiatric and substance-use disorders were added to the model (model 2), the following risk factors were significantly associated with smoking during pregnancy: education (less than high school and general equivalency diploma or high school compared with some college), race/ethnicity (other compared with White), marital status (unmarried), and a current-year alcohol or substance disorder. Notably, there was no significant association between mood or anxiety disorders and smoking during pregnancy. The next regression model was estimated among the 122 NESARC participants who were or had been daily smokers (model 3). In this analysis, less than high school education, current-year nicotine dependence, and a history of early onset smoking were associated with elevated risks of smoking during pregnancy. In the final regression model (model 4), the sample was further restricted to participants who smoked in the 12 months prior to interview (n = 92); this restriction was done to isolate the risk of continued smoking into pregnancy. Prevalence ratios were 1.99 for less than high school education, 2.63 for nicotine dependence, and 1.62 for early onset smoking.

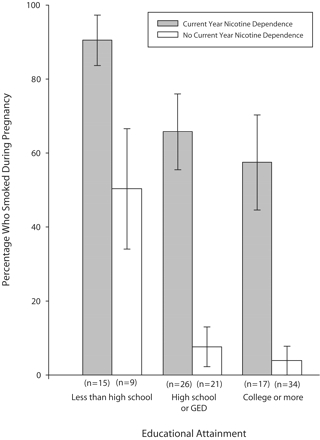

The combined influences of education and nicotine dependence on maternal smoking during pregnancy among lifetime daily smokers are illustrated in Figure 1 ▶. Despite the relatively small number of participants in each category, the graph demonstrates a marked gradient in risk for smoking during pregnancy among those with less than a high school education as well as nicotine dependence in the current year (90.5%) compared with individuals with some college education and without nicotine dependence (3.9%).

FIGURE 1—

Women who smoked during pregnancy, by nicotine dependence and educational attainment: National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, 2001–2002.

Note. Among 122 lifetime daily smokers.

DISCUSSION

Our major findings were that less than high school educational attainment and current-year nicotine dependence were significant predictors of smoking during pregnancy. Mood, anxiety, and other substance-use disorders were not related to maternal smoking during pregnancy when education and nicotine dependence were accounted for, nor were other aspects of socioeconomic status. Consistent with prior studies, we found that early onset of daily smoking was also related to smoking during pregnancy.41 The higher likelihood of smoking among individuals with lower education compared with those with higher levels of education is consistent with a large body of evidence on inequalities in smoking as well as with research showing that women with lower educational attainment are less likely to quit when they become pregnant than women with higher levels of education.12,28,45,46 Women with lower levels of education may have limited access to smoking cessation programs, and the programs available to them may be less effective.47,48 Lower educational attainment is also associated with younger age at smoking initiation49,50; cessation may therefore be more difficult to achieve because of a longer duration of smoking history and more severe nicotine dependence.51–53

Our results suggest that nicotine dependence may be the most important mental health barrier to smoking cessation among pregnant women. The association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and mental health problems was attributable entirely to nicotine dependence. The absence of a significant association between mood or anxiety disorders and smoking during pregnancy would appear to contradict prior studies that reported such an association, particularly with depression.22–24,54–57 However, few of these prior studies included a measure of nicotine dependence. The findings of those that did26,27 are consistent with our findings. Nicotine dependence is highly correlated with depression in epidemiological samples, including the NESARC29 and National Comorbidity Survey,30 and may explain the depression–smoking relationship found in prior studies. However, because our study was cross-sectional, the temporal relationships among depression, nicotine dependence, and smoking could not be established.

Limitations of this study include the absence of data on number of weeks gestation and the 24-hour definition of smoking during pregnancy as opposed to an assessment that covered the entire period of gestation. However, results were identical when smoking in the month prior to the interview was used as the definition (data not shown); this time period likely precedes knowledge of pregnancy status for some women. The use of self-reports of smoking may have led to an underestimation of smoking. However, the rate of maternal smoking during pregnancy in the NESARC was comparable to that observed in other national studies.10,11,13,58,59 In addition, self-reported smoking is highly concordant with smoking status determined by salivary cotinine among pregnant women.60

Smoking cessation programs that target nicotine dependence have demonstrated efficacy among pregnant women.61,62 In addition to intensive psychosocial interventions, nicotine replacement therapy is advocated for use among pregnant smokers,63 as are other pharmacologic therapies.33,64 Pharmacotherapy that uses the lowest effective doses possible (especially for nicotine-replacement therapy) should be considered for pregnant women unable to quit through intensive psychosocial interventions, particularly if the benefits of potential quitting outweigh the risks of pharmacotherapy.18 Improvement in access to and effectiveness of cessation treatments for pregnant smokers may bring about reductions in in-utero exposure to cigarettes among infants of low socioeconomic status. More broadly, efforts to prevent the development of nicotine dependence, particularly among individuals with lower levels of education, are needed to reduce inequalities in tobacco-related diseases.49

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant RO3 DA080887 and career development awards K01 MH66057, K08 MH070627, K25 HL081275, and K08 DA017145).

Human Participant Protection This study was based on publicly available data without any information that identified individuals and was determined to be exempt from human subjects review by the Harvard School of Public Health institutional review board.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors All of the authors participated in the origination of the study, statistical analysis, interpretation of results, and preparation of the article.

References

- 1.Floyd RL, Rimer BK, Giovino GA, Mullen PD, Sullivan SE. A review of smoking in pregnancy: effects on pregnancy outcomes and cessation efforts. Annu Rev Public Health. 1993;14:379–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ernst M, Moolchan ET, Robinson ML. Behavioral and neural consequences of prenatal exposure to nicotine. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40: 630–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cnattingius S. The epidemiology of smoking during pregnancy: smoking prevalence, maternal characteristics, and pregnancy outcomes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6 (suppl 2):S125–S140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olds DL, Henderson CR Jr, Tatelbaum R. Intellectual impairment in children of women who smoke cigarettes during pregnancy. Pediatrics. 1994;93:221–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mortensen EL, Michaelsen KF, Sanders SA, Reinisch JM. A dose-response relationship between maternal smoking during late pregnancy and adult intelligence in male offspring. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2005;19:4–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin RP, Dombrowski SC, Mullis C, Wisenbaker J, Huttunen MO. Smoking during pregnancy: association with childhood temperament, behavior, and academic performance. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;31:490–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cornelius MD, Ryan CM, Day NL, Goldschmidt L, Willford JA. Prenatal tobacco effects on neuropsychological outcomes among preadolescents. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2001;22:217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Escobedo LG, Peddicord JP. Smoking prevalence in US birth cohorts: the influence of gender and education. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:231–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagenknecht LE, Perkins LL, Cutter GR, et al. Cigarette smoking behavior is strongly related to educational status: the CARDIA study. Prev Med. 1990;19: 158–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ventura SJ, Hamilton BE, Mathews TJ, Chandra A. Trends and variations in smoking during pregnancy and low birth weight: evidence from the birth certificate, 1990–2000. Pediatrics. 2003;111(5 pt 2): 1176–1180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mathews TJ. Smoking during pregnancy in the 1990s. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2001;49:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colman GJ, Joyce T. Trends in smoking before, during, and after pregnancy in ten states. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24:29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ebrahim SH, Floyd RL, Merritt RK II, Decoufle P, Holtzman D. Trends in pregnancy-related smoking rates in the United States, 1987–1996. JAMA. 2000; 283:361–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spencer N. Explaining the social gradient in smoking in pregnancy: early life course accumulation and cross-sectional clustering of social risk exposures in the 1958 British national cohort. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62: 1250–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Breslau N, Peterson EL. Smoking cessation in young adults: age at initiation of cigarette smoking and other suspected influences. Am J Public Health. 1996; 86:214–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hymowitz N, Cummings KM, Hyland A, Lynn WR, Pechacek TF, Hartwell TD. Predictors of smoking cessation in a cohort of adult smokers followed for five years. Tob Control. 1997;6(suppl 1):S57–S62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinto RP, Abrams DB, Monti PM, Jacobus SI. Nicotine dependence and likelihood of quitting smoking. Addict Behav. 1987;12:371–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, Md: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2000.

- 19.Breslau N, Johnson EO, Hiripi E, Kessler R. Nicotine dependence in the United States: prevalence, trends, and smoking persistence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:810–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu MC, Davies M, Kandel DB. Epidemiology and correlates of daily smoking and nicotine dependence among young adults in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:299–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCormick MC, Brooks-Gunn J, Shorter T, Holmes JH, Wallace CY, Heagarty MC. Factors associated with smoking in low-income pregnant women: relationship to birth weight, stressful life events, social support, health behaviors and mental distress. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43:441–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu SH, Valbo A. Depression and smoking during pregnancy. Addict Behav. 2002;27:649–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pritchard CW. Depression and smoking in pregnancy in Scotland. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1994;48:377–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanna EZ, Faden VB, Dufour MC. The motivational correlates of drinking, smoking, and illicit drug use during pregnancy. J Subst Abuse. 1994;6:155–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stewart DE, Streiner DL. Cigarette smoking during pregnancy. Can J Psychiatry. 1995;40:603–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ludman EJ, McBride CM, Nelson JC, et al. Stress, depressive symptoms, and smoking cessation among pregnant women. Health Psychol. 2000;19:21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vander Weg MW, Ward KD, Scarinci IC, Read MC, Evans CB. Smoking-related correlates of depressive symptoms in low-income pregnant women. Am J Health Behav. 2004;28:510–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kahn RS, Certain L, Whitaker RC. A reexamination of smoking before, during, and after pregnancy. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1801–1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grant BF, Hasin DS, Chou SP, Stinson FS, Dawson DA. Nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1107–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Breslau N, Novak SP, Kessler RC. Psychiatric disorders and stages of smoking. Biol Psychiatry. 2004; 55:69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elizabeth Jesse D, Graham M, Swanson M. Psychosocial and spiritual factors associated with smoking and substance use during pregnancy in African American and White low-income women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35:68–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Melvin C, Gaffney C. Treating nicotine use and dependence of pregnant and parenting smokers: an update. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(suppl 2):S107–S124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oncken CA, Kranzler HR. Pharmacotherapies to enhance smoking cessation during pregnancy. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2003;22:191–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hegaard HK, Kjaergaard H, Moller LF, Wachmann H, Ottesen B. Multimodal intervention raises smoking cessation rate during pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82:813–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grant BF, Kaplan K, Shepard J, Moore T. Source and accuracy statement for Wave 1 of the 2001–2002 National Epidemiology Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Bethesda, Md: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2003.

- 36.Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61: 807–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grant BF, Dawson D. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV). Rockville, Md: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2001.

- 38.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV-TR. Rev 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

- 39.Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Kay W, Pickering R. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;71:7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grant BF, Harford TC, Dawson DA, Chou PS, Pickering RP. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview schedule (AUDADIS): reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995;39:37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen X, Stanton B, Shankaran S, Li X. Age of smoking onset as a predictor of smoking cessation during pregnancy. Am J Health Behav. 2006;30:247–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bailey BA. Factors predicting pregnancy smoking in Southern Appalachia. Am J Health Behav. 2006;30: 413–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, Hafner JP. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157: 940–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paterson JM, Neimanis IM, Bain E. Stopping smoking during pregnancy: are we on the right track? Can J Public Health. 2003;94:297–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pickett KE, Wakschlag LS, Dai L, Leventhal BL. Fluctuations of maternal smoking during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:140–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pullon S, Webster M, McLeod D, Benn C, Morgan S. Smoking cessation and nicotine replacement therapy in current primary maternity care. Aust Fam Physician. 2004;33:94–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bonollo DP, Zapka JG, Stoddard AM, Ma Y, Pbert L, Ockene JK. Treating nicotine dependence during pregnancy and postpartum: understanding clinician knowledge and performance. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48:265–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Escobedo LG, Anda RF, Smith PF, Remington PL, Mast EE. Sociodemographic characteristics of cigarette smoking initiation in the United States. Implications for smoking prevention policy. JAMA. 1990;264: 1550–1555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chassin L, Presson CC, Rose JS, Sherman SJ. The natural history of cigarette smoking from adolescence to adulthood: demographic predictors of continuity and change. Health Psychol. 1996;15:478–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lindqvist R, Aberg H. Who stops smoking during pregnancy? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80: 137–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pierce JP, Gilpin E. How long will today’s new adolescent smoker be addicted to cigarettes? Am J Public Health. 1996;86:253–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Siahpush M, Heller G, Singh G. Lower levels of occupation, income and education are strongly associated with a longer smoking duration: multivariate results from the 2001 Australian National Drug Strategy Survey. Public Health. 2005;119:1105–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zuckerman B, Bauchner H, Parker S, Cabral H. Maternal depressive symptoms during pregnancy, and newborn irritability. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1990;11: 190–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blalock JA, Fouladi RT, Wetter DW, Cinciripini PM. Depression in pregnant women seeking smoking cessation treatment. Addict Behav. 2005;30:1195–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blalock JA, Robinson JD, Wetter DW, Cinciripini PM. Relationship of DSM-IV-based depressive disorders to smoking cessation and smoking reduction in pregnant smokers. Am J Addict. 2006;15:268–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kiernan K, Pickett KE. Marital status disparities in maternal smoking during pregnancy, breastfeeding and maternal depression. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:335–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smoking during pregnancy—United States, 1990–2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53: 911–915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ananth CV, Kirby RS, Kinzler WL. Divergent trends in maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy: United States 1990–99. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2005;19:19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Graham H, Owen L. Are there socioeconomic differentials in under-reporting of smoking in pregnancy? Tob Control. 2003;12:434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lumley J, Oliver SS, Chamberlain C, Oakley L. Interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(4): CD001055. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Windsor R. Smoking cessation or reduction in pregnancy treatment methods: a meta-evaluation of the impact of dissemination. Am J Med Sci. 2003;326: 216–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Peters MJ, Morgan LC. The pharmacotherapy of smoking cessation. Med J Aust. 2002;176:486–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chan B, Einarson A, Koren G. Effectiveness of bupropion for smoking cessation during pregnancy. J Addict Dis. 2005;24:19–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]