Introduction

Drug addictions are characterized by compulsive seeking and self-administration behaviors1. These behaviors have been established both in humans and in animal models2,3. Pavlovian conditioning to environmental cues that predict drug effects appears to play a significant role in the acquisition and maintenance of drug addictions4-7. For example, environmental cues repeatedly paired with drug administrations have been shown to produce drug-related behavior in the absence of that drug8,9. The phenomena of anticipatory responses, drug tolerance, withdrawal effects, and relapse behavior all appear to be related to conditioned responses to drug-paired cues8,10,11.

Circadian rhythms also appear to play a role in drug addiction. For example, both circadian and circannual rhythms have been observed in emergency room admissions for drug overdoses12. Studies with genetically altered mice have shown that the circadian clock gene Per has an important role in regulating behavioral responses to cocaine13 and ethanol14-16, and the effects of these drugs vary when administered at different times of the day17,18. Further, several addictive drugs also have been shown to affect the patterns of endogenous circadian rhythms. For example, a single dose of MDMA can cause long-term changes in sleep and motor activity patterns19, and ethanol17, morphine20, and phenobarbital21 alter daily patterns of body temperature and activity.

Injections of methamphetamine and cocaine create circadian anticipatory behavior when administered on schedules with either circadian (24 hour) or infradian (>24 hour) periods22-24. This circadian drug anticipatory behavior is typically characterized by an increase in locomotor activity beginning approximately 22 hours after administration, and effect that resembles circadian food anticipatory activity25. For both methamphetamine and food, these circadian anticipatory patterns appear to be independent of the light/dark cycle and the influence of the suprachiasmatic nucleus26,27.

The present study examined behavior produced by injections of nicotine, a highly addictive psychomotor stimulant28. A number of studies have shown that environmental cues associated with nicotine administration are an important component of nicotine addiction in animal models29-32. These conditioned cues contribute to the reinstatement of extinguished self-administration and drug seeking in both humans and rats33-35.

There is also evidence that circadian activity rhythms contribute to nicotine addiction. Several nicotine effects can be enhanced or attenuated depending on the time of administration36,37, and nicotine clearance in humans shows circadian variation38. Nicotine intake also affects several endogenous circadian rhythms, including meal patterns39,40, sleeping patterns41, body temperature42, heart rate43, blood pressure44, stress45, and mood46-49. Additionally, daily nicotine injections induce the expression of the immediate early gene c-fos in the suprachiasmatic nucleus50, which is a common index of circadian entrainment.

The present study asks whether (1) daily nicotine injections can entrain circadian activity rhythms and (2) the presence of a conditioned environmental cue will affect the expression of these rhythms. Based on the results of previous studies with methamphetamine and cocaine, we expected to see both pre-injection anticipatory activity (wheel running and drinking) and a post-injection activity spike persisting for at least two days when injections were withheld22-24 in the Circadian Effects Test (Test 1) and the Probe Test (Test 3). We also expected the nicotine-paired tone, when presented without the nicotine injections in the Stimulus Effects Test (Test 2), to elicit activity increases comparable to post-injection activity spikes7.

Rats show circadian rhythmicity in feeding, drinking, and locomotor activity, and these rhythms are entrained by two anatomically separable oscillators: a food-entrainable oscillator and a light-entrainable oscillator51-56. We used conditions of constant dim light and rate-limited feeding57 to isolate circadian activity rhythms associated with nicotine and to negate the influences of the zeitgebers of light/dark cycles and large meals. Under constant light, circadian activity rhythms typically free run with periods greater than 24 hours58,59, and in most female rats the estrous cycle is suspended 60. We used female rats instead of males because of the length of the study, as wheel running in males tends to decrease with age over the time period of this study61,62. However, a study of cocaine-induced circadian rhythms in male rats found entrainment similar to that found in our previous studies of methamphetamine-induced rhythms in female rats24. We used daily saline injections at a time different than the nicotine injections to clarify locomotor effects related to handling, the injection procedure, the presence of the experimenter in the room, and the tone paired with the nicotine injections.

Methods

Sixteen adult female Sprague-Dawley rats were obtained from the rodent colony in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, Indiana University Bloomington. Rats were approximately 90 days old at the beginning of the experiment. For the duration of the study, all rats were housed in Wahmann wheel boxes in constant light with continuous access to two water bottles. Water bottles were filled and cage liners were changed as necessary, usually every 4-6 days. Feeding was rate-limited, with access limited to no more than two 97 mg pellets (NOYES Rodent Food Pellet, Research Diets, Inc.) every 5 minutes. Data collected included water bottle licks, food pellets consumed, and wheel turns. The data were recorded continuously in five-minute bins using the Med-PC IV program (MedAssociates, Inc.). The rats were randomly assigned to one of two experimental groups (Unpaired and Paired) so that each group consisted of eight rats. All experimental procedures were approved by the Bloomington Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

A solution of 0.9% NaCl (VWR Pharmaceuticals) was used for all saline injections. A 1.0 mg/ml (free base weight) nicotine solution was used for all nicotine injections and was administered at a volume of 1.0 mg/kg. The dosage level for this study was chosen based on a conditioned place preference study63, in which this amount of nicotine conditioned place preference, but not place aversion. Nicotine hydrogen tartrate powder (Sigma Pharmaceuticals, St. Louis, MO) was mixed with 0.9% NaCl solution and dilute NaOH solution and brought to a pH of approximately 7.0. Nicotine and saline solutions were refrigerated at approximately 4°C when not in use.

The rats were housed in the wheel boxes for a total of 56 days that included a 14-day acclimation period, 40 experimental days, and a 4 day post-injection period (Table 1). The acclimation period was used to adapt the rats to the wheel boxes and handling by experimenters, and to establish baseline activity levels. During the first 6 days of acclimation, rats were handled only to record daily body weight data. For the last 8 days of the acclimation period, each rat received a subcutaneous injection of saline at 1100 and 1900. For the duration of the study, body weights were recorded at the first daily injection time (1100). On days when injections were not scheduled (including test days), the rats were briefly handled at approximately 1500 to record body weights.

Table 1.

Schedule of study activities

| Unpaired Group Injections | Paired Group Injections | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Phase | No.of Days | 11:00 | 19:00 | 11:00 | 19:00 | Stimulus Presented |

| Acclimation | 6 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Acclimation Injections | 8 | Saline | Saline | Saline | Saline | - |

|

| ||||||

| Nicotine Phase 1 | 14 | Nicotine | Saline | Saline | Nicotine | 19:05-19:25 |

| Test 1: Circadian Effects | 3 | - | - | - | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| Nicotine Phase 2 | 7 | Nicotine | Saline | Saline | Nicotine | 19:05-19:25 |

| Test 2: Stimulus Effects | ||||||

| Normal Time | 2 | - | - | - | - | 19:05-19:25 |

| Novel Time | 2 | - | - | - | - | 11:05-11:25 |

|

| ||||||

| Nicotine Phase 3 | 7 | Nicotine | Saline | Saline | Nicotine | 19:05-19:25 |

| Test 3: Probe Test | ||||||

| Novel Time | 1 | Saline | Nicotine | Nicotine | Saline | - |

| Circadian Effects | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Normal Time | 1 | Nicotine | Saline | Saline | Nicotine | - |

| Circadian Effects | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| Final Baseline | 4 | - | - | - | - | - |

The experimental period consisted of three nicotine injection phases (NIPs), each followed by a short test phase. The first nicotine injection phase (NIP1) followed the acclimation phase, and lasted 14 days. During this phase, Group Unpaired rats received daily injections of nicotine at 1100 and daily saline injections at 1900. Group Paired rats received nicotine injections at 1900 and saline injections at 1100. For the duration of this phase, an auditory stimulus (sonalert tone, approximately 80 db) was presented from 1905 to 1925. Injections for Group Paired began promptly at 1900 and finished by 1905 so that the onset of the tone was 0-5 minutes after the injection. This is the optimal interstimulus interval for nicotine-induced locomotor conditioning, as reported by Bevins, Eurek and Besheer64. Presentation of the cue immediately after the injection presumably allows it to pair with the effects of the drug, and not with the aversive injection procedure. The first test phase (Circadian Effects) examined circadian oscillations in the PRE and POST periods of the nicotine and saline injections over a three day period. During this test phase the tone was not presented and no injections were administered.

The second nicotine injection phase (NIP2) lasted 7 days. The injections and the tone occurred at the same times as in NIP1. The second test phase (Stimulus Effects) was four days long, and was designed to test for the effects of the tone without the injections at the normal presentation time and at a novel time. For the first two days of this phase, the tone was presented at its normal time from 1905 to 1925. For the last two days, the tone was presented at a novel time from 1105 to 1125.

The third nicotine injection phase (NIP3) also lasted 7 days and was identical in procedure to the prior injection phases. The final test phase (Probe Test) lasted four days, and examined the effects of the injections without the tone at normal and novel times. On the first day, the nicotine and saline injection times were switched for each group. On the third day, all rats received injections at the normal times. No injections were administered on the second and fourth days of this test phase.

Activity during the two hour period prior to an injection time was designated as pre-injection anticipatory activity (PRE). Activity during the three hour period immediately after an injection was designated as post-injection evoked activity (POST). Drinking and wheel running activity data were analyzed in the form of the original counts and as the percentage of total daily activity, which was calculated by dividing hourly activity by the total activity in that 24 hour period. A square root transformation was performed on the wheel counts to normalize the data.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 13.0. Multivariate repeated measures tests were performed for the wheel running and drinking data. Group assignment and substance administered (nicotine or saline) were treated as between-subjects factors. Simple planned comparisons were performed to compare baseline data with subsequent days and/or phases. Pre-injection and post-injection activities were tested both as total counts and as the percentage of total daily activity. We compared data averaged over the last four days of the acclimation injection phase with data from the last four days of the three nicotine injection phases. For each nicotine injection phase, data averaged over the last four days were compared with data from each of the test days immediately following.

Results and Discussion

This section summarizes the effects of nicotine versus saline injections on wheel running and drinking during three successive injection phases (1, 2, and 3), and during the subsequent Tests 1, 2, and 3). For all statistical tests performed, similar results were obtained for all measures of entrainment (wheel counts, percentage of total daily wheel running, and drinking). Due to these similarities, only the results of the wheel count data analyses are included, except where noted.

Acclimation and Nicotine Injection Phases 1, 2, and 3

Results

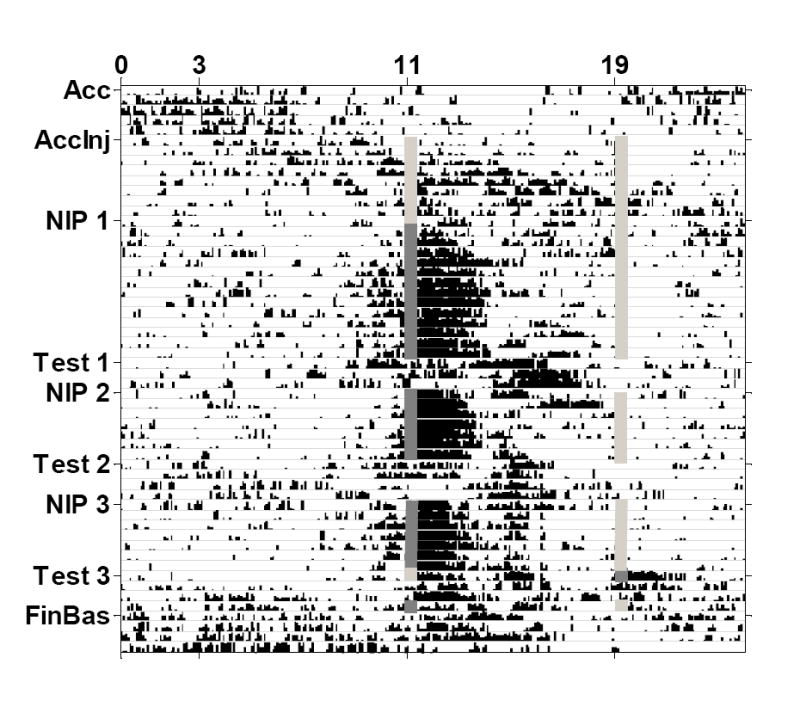

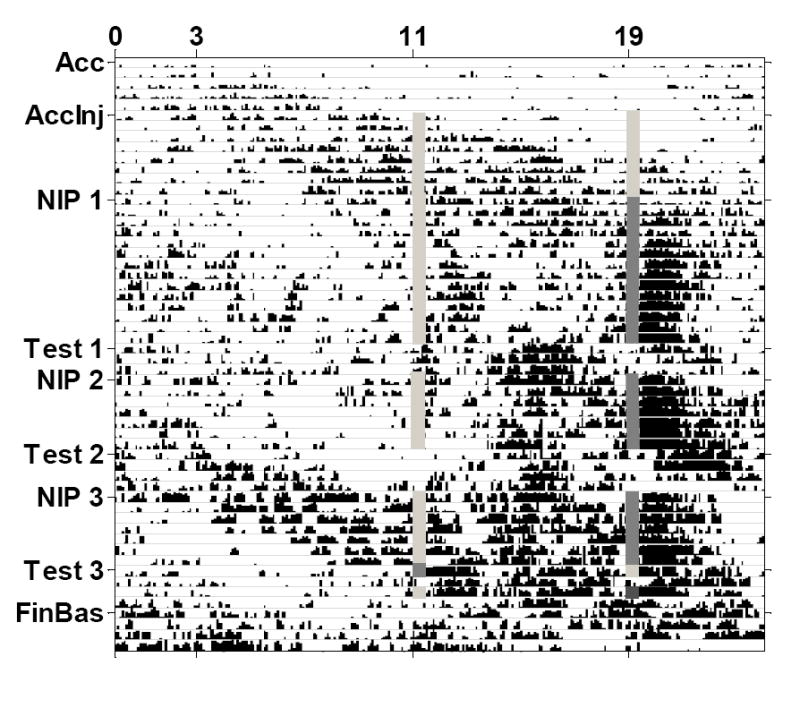

Actograms of mean wheel running activity for the 8 rats in Group Unpaired are displayed in Figure 1, and for Group Paired in Figure 2. Table 2 shows the period length of the activity cycles (τ values) for the feeding, drinking, and wheel running rhythms for each phase of the study. During acclimation, rats in both groups had τ values greater than 24 hours for all measured rhythms, indicating the presence of free-running rhythms. During the nicotine injection phases, τ values for both groups were slightly less than or equal to 24, which provides further evidence of circadian entrainment.

Figure 1.

Actogram of mean wheel running activity for Group Unpaired. Free-running activity occurred throughout the acclimation and acclimation injection phases (Acc and AccInj). During the nicotine injection phases (NIP), wheel running entrained to the nicotine injection time (dark gray lines), but not to the saline injection time (light gray lines). Pre-injection anticipatory activity increases began approximately 2 hours prior to the nicotine injection time. Post-injection activity spikes persisted for approximately 3 hours after the nicotine injection. Both the pre-and post-injection activity increases persisted on the test days (Test) when injections were withheld.

Figure 2.

Actogram of mean wheel running activity for Group Paired. Free-running activity occurred throughout the acclimation and acclimation injection phases (Acc and AccInj). During the nicotine injection phases (NIP), wheel running entrained to the nicotine injection time (dark gray lines; saline injections are indicated with light gray lines), but free-running rhythms persisted throughout the entire study. The post-nicotine activity peak was slightly delayed in this group, but was similar in magnitude and duration to Group Unpaired, and persisted when nicotine injections were withheld on the test days (Test). For this group, pre-nicotine activity was not greater than wheel running at other times of day.

Table 2.

Period length of activity cycle (tau value) for measured activities during study phases. Standard deviations are indicated in parentheses.

| Unpaired Group | Paired Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Phase | Wheel | Water | Food | Wheel | Water | Food |

| Acclimation | 27.08 (2.71) | 24.42 (1.03) | 26.83 (2.76) | 24.75 (0.69) | 24.08 (1.39) | 24.08 (2.57) |

| Acclimation Injections | 24.08 (3.04) | 26.83 (1.38) | 26.33 (1.35) | 24.50 (3.39) | 25.33 (2.51) | 26.08 (3.13) |

|

| ||||||

| Nicotine Phase1 | 24.00 (2.85) | 24.00 (2.63) | 24.00 (3.28) | 24.00 (2.77) | 24.00 (3.64) | 24.00 (3.09) |

| Test 1: Circadian Effects | 24.92 (2.07) | 24.25 (1.42) | 24.00 (3.03) | 24.33 (1.01) | 24.58 (1.55) | 24.67 (2.30) |

|

| ||||||

| Nicotine Phase 2 | 24.00 (0.38) | 24.00 (2.62) | 24.00 (3.37) | 24.00 (0.05) | 24.00 (1.78) | 24.00 (3.13) |

| Test 2: Stimulus Effects | 24.17 (3.85) | 27.25 (1.41) | 24.00 (3.85) | 24.50 (3.19) | 24.75 (0.04) | 24.75 (2.40) |

|

| ||||||

| Nicotine Phase 3 | 24.00 (0.18) | 24.00 (1.90) | 23.92 (1.59) | 24.00 (1.62) | 24.00 (1.41) | 24.00 (2.21) |

| Test 3: Probe Test | 24.17 (3.57) | 24.08 (2.83) | 24.42 (4.16) | 24.08 (3.26) | 25.42 (0.95) | 24.33 (3.70) |

|

| ||||||

| Final Baseline | 24.00 (1.39) | 28.92 (2.29) | 25.00 (1.96) | 27.17 (2.41) | 26.83 (1.54) | 24.08 (1.31) |

For the three-hour POST periods (following injections), activity levels associated with the saline injection times in both groups were significantly less than activity levels associated with the nicotine injection times (study phase: F(3, 26)=8.159, p=0.001; substance: F(1, 28)=12.267, p=0.002; phase-substance interaction: F(3, 26)=14.264, p<0.001). A large spike in activity occupied the first three hours after the nicotine injection in both groups, although Group Paired showed a locomotor response delay of approximately 20 minutes.

During the PRE period, both Group Unpaired and Group Paired showed an increase in activity that started approximately two hours prior to the nicotine injection time. However, while Group Unpaired had little activity outside of the PRE- and POST-nicotine periods, Group Paired showed a considerable amount of activity outside of the PRE- and POST-nicotine periods (see Figure 2). Additionally, in the POST-saline period, Group Paired showed a significantly greater percentage of total daily wheel running than Group Unpaired (group-substance: F(1, 28)=31.191, p<0.001). A significant phase-substance interaction was also found for the PRE period (F(3, 26)=6.324, p=0.002).

Discussion

The results of this study showed a clear circadian activity rhythm during all nicotine injection phases. Both wheel running and drinking rhythms became entrained to the nicotine injection time for all rats. Activity in the PRE- and POST-saline periods was significantly lower than in the PRE-and POST-nicotine periods. A post-injection activity bout (POST) occurred after the nicotine injection in both Groups Paired and Unpaired throughout the study, and this bout generally lasted for 2 to 3 hours.

While the two groups did not differ significantly in post-injection activity, pre-injection activity differed considerably. Group Unpaired, with no tone paired with their nicotine injections, consistently showed anticipatory wheel running and drinking prior to the nicotine injection time (PRE-nicotine). However, in Group Paired, activity in the PRE-nicotine period was not notably greater than in periods throughout the rest of the day.

Test 1: Circadian Effects

Results

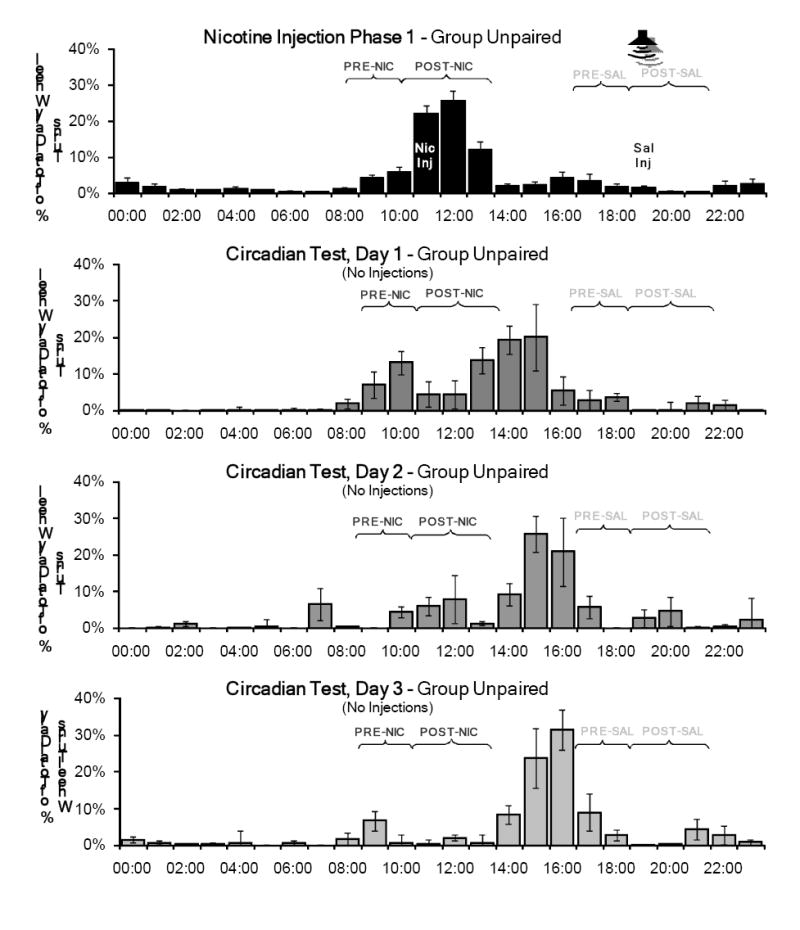

For all test phases and the final baseline phase, τ values (period length) for both groups were greater than or equal to 24 hours, indicating that, in the absence of injections, activity rhythms began to free-run (see Table 2). The percentage of total daily wheel running in the PRE and POST periods for nicotine injection phase 1 and the three days of the Circadian Effects Test are shown in Figure 3 for Group Unpaired and in Figure 4 for Group Paired.

Figure 3.

Mean percentage of total daily wheel running across the 14 days of the first nicotine injection phase compared to the three days of the Circadian Effects test for Group Unpaired. During the test phase, no injections were administered and the tone was not presented, but the rats were handled briefly at 1500 to record body weights. Activity in the PRE-and POST-nicotine injection periods (PRE-NIC and POST-NIC) persisted for two days in this test. No significant activity was associated with the saline injection time (PRE-SAL and POST-SAL).

Figure 4.

Mean percentage of total daily wheel running across the 14 days of the first nicotine injection phase compared to the three days of the Circadian Effects Test for Group Paired. No injections were administered during this test phase and the tone was not presented, but the rats were handled briefly at 1500 to record body weights. Activity in the POST-nicotine injection period (POST-NIC) persisted for two days in this test. No significant activity was associated with the saline injection time (PRE-SAL and POST-SAL) or prior to the nicotine injection time (PRE-NIC).

The greatest amount of activity recorded on each day during Test 1 occurred at 1500, the time the rats were handled to record body weights. However, a considerable amount of activity was also recorded during the POST-nicotine periods in both groups that was greater than the activity recorded in the POST-saline periods (day: F(3, 26)=6.254, p=0.002; substance: F(1, 28)=5.205, p=0.030; day-substance interaction: F(3, 26)=4.518, p=0.011). Group Unpaired showed persistent activity during both the PRE- and POST-nicotine periods for all measures on days 1 and 2, but not day 3. Unlike Group Unpaired, Group Paired had little activity during the PRE-nicotine period on all three test days, but showed persistent activity during the POST-nicotine period on test days 1 and 2. Comparison of the two groups found significant differences only in the PRE-nicotine period (day-group: F(3, 26)=4.644, p=0.010) in this test phase.

Discussion

During the first test phase, both the injections and the tone were withheld for three days to reveal circadian activity patterns. When nicotine was withheld, nicotine-entrained wheel running and drinking activity persisted for 2 days in the POST-nicotine period for Groups Paired and Unpaired. However, entrained activity in the PRE-nicotine period persisted only for Group Unpaired during this test phase. Group Paired did not show a notable rise in activity in the PRE-nicotine period during the injection phase, so this absence of activity is consistent with the previous pattern. Since the activity response to the nicotine injections in Groups Paired and Unpaired differed in the presence of a paired cue, this lack of anticipation in Group Paired appears to be due to a tone-induced interference with nicotine anticipatory activity.

It should be noted that the greatest amount of activity recorded on the days of Test 1 (and on most test days throughout the study) occurred when the rats were handled to record body weights at a time that was not in close proximity to the nicotine and saline injection times. On test days, this handling was clearly an arousing stimulus for the rats. It is possible that the handling may have served as a predictive cue for the nicotine effects, but this is unlikely due to the lack of activity observed after handling for the saline injections throughout the study. The absence of an injection at 1100 on the test days may have had an activating effect for the rats, causing the effects of the handling at 1500 to be amplified. In future studies, it appears best that the rats not be handled at all for at least the first two non-injection days.

Test 2: Stimulus Effects

Results

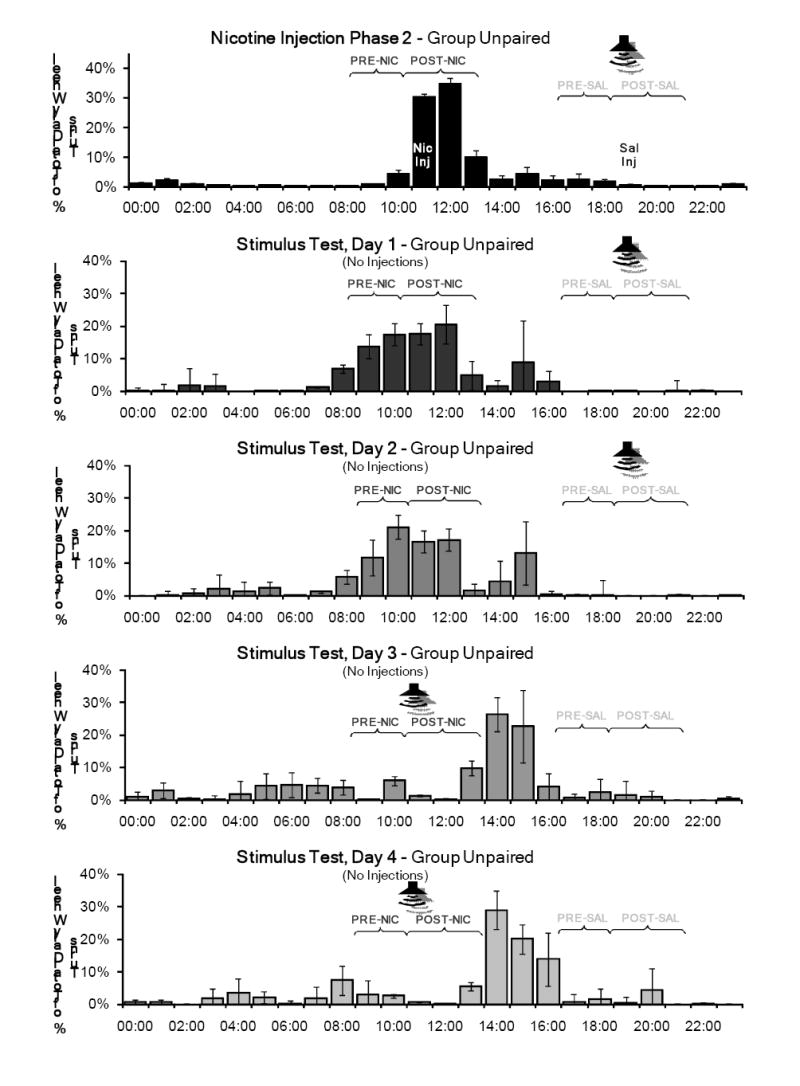

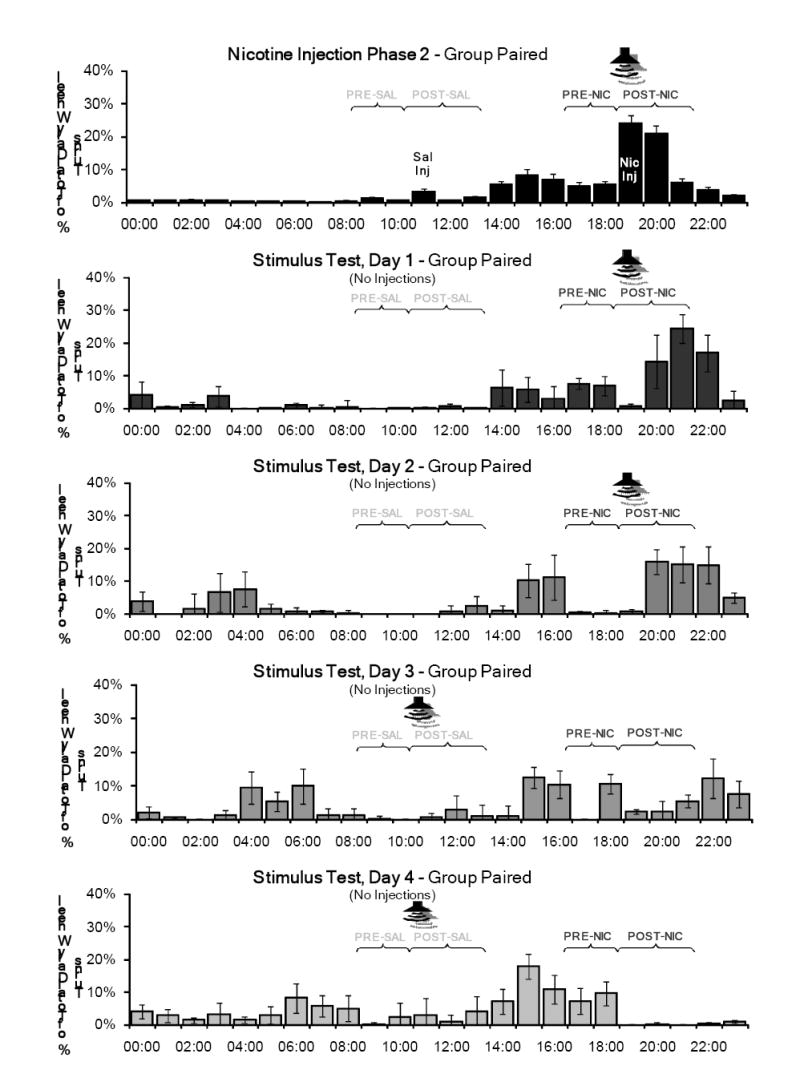

The percentage of total daily wheel running in the PRE and POST periods for nicotine injection phase 2 and the four days of Test 2 is shown in Figure 5 for Group Unpaired and in Figure 6 for Group Paired. Group Unpaired showed persistent activity in the PRE- and POST-nicotine periods on days 1 and 2, but no activity at these times on days 3 and 4. In the POST-nicotine period, Group Paired showed a locomotor response delayed approximately 20 minutes on the first three test days. No significant locomotor response was observed when the tone was presented at the novel time (the beginning of the POST-saline period) on days 3 and 4. In both the PRE and POST periods, nicotine produced significantly greater activity than saline (PRE: F(1, 28)=6.243, p=0.019; POST: F(1, 28)=7.001, p=0.013), and a significant day-substance interactions (PRE: F(4, 25)=5.430, p=0.003; POST: F(4, 25)=7.637, p<0.001).

Figure 5.

Mean percentage of total daily wheel running across the 7 days of the second nicotine injection phase and the four days of the Stimulus Effects Test for Group Unpaired. The tone was presented at its normal time (1905 - 1925) on the first two days and at a novel time (1105 – 1125) on the third and fourth days. No injections were administered during this test phase, and as in the previous test phase, the rats were handled briefly at 1500 to record body weights. Activity in the PRE-and POST-nicotine periods (PRE-NIC and POST-NIC) persisted for two days. No noticeable activity was recorded in these periods when the tone was played on the last two days.

Figure 6.

Mean percentage of total daily wheel running across the 7 days of the second nicotine injection phase and the four days of the Stimulus Effects Test for Group Paired. The tone was presented at its normal time (1905 - 1925) on the first two days and at a novel time (1105 – 1125) on the third and fourth days. No injections were administered during this test phase, but the rats were handled briefly at 1500 to record body weights. Significant activity was evoked when the stimulus was played at the normal time, but not at the novel time.

Discussion

Test 2 was designed to investigate the conditioned effects of the auditory cue. The tone was presented at its normal time for two days, then at a novel time (the earlier injection time) for an additional two days. No injections were administered during this phase.

Activity patterns in the pre- and post-injection periods in both groups were very similar to the activity patterns observed in the first test phase, although this second test phase showed a greater peak of activity around the nicotine injection times. Group Unpaired showed persistent activity in the PRE- and POST-nicotine periods on the first two test days, and little activity at these times on the last two test days. Group Paired showed activity in the POST-nicotine period on the first two days, and also showed little activity during the PRE-nicotine period. This was consistent with the absence of activity in PRE-nicotine period in the first test phase and the second nicotine injection phase.

The results of this test showed that the effects of the tone were dependent on its relation to the nicotine administration time. Group Paired showed a robust locomotor response to the tone when it was presented at the normal nicotine injection time (POST-nicotine in Figure 6). However, when the tone was presented at a novel time (beginning of the POST-saline period), no evoked locomotor response was observed. Despite the earlier tone presentation, Group Paired also continued to show activity in the normal POST-nicotine period on day 3 of this test. This result indicates that the conditioned activity response to the paired tone was coupled to the time of administration, and cannot be evoked simply by presenting the tone at a different time of the day.

For Group Unpaired, the tone may have acted as a “negative” cue, signaling the absence of nicotine. During the nicotine injection phases, the tone always was paired with the saline injections (at the beginning of the POST-saline period) for this group. The complete lack of activity shown in response to the novel tone presentation (at the beginning of the POST-nicotine period) was indistinguishable from the amount shown in the PRE-saline and POST-saline periods. This occurred even though the time of the novel stimulus presentation was the normal nicotine injection time for this group. This may indicate that the cue was a negative predictor of nicotine and perhaps produced a conditioned inhibitory response not coupled to a specific time of day. However, all that we can say definitively is that it did not appear completely neutral for these rats.

Test 3: Probe Test

Results

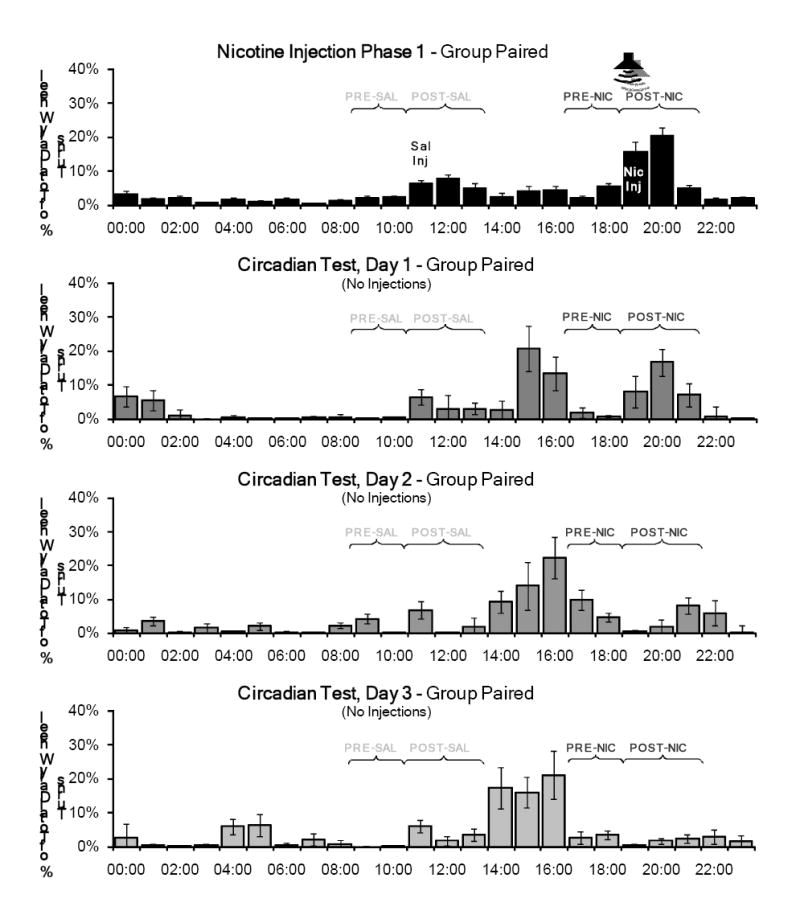

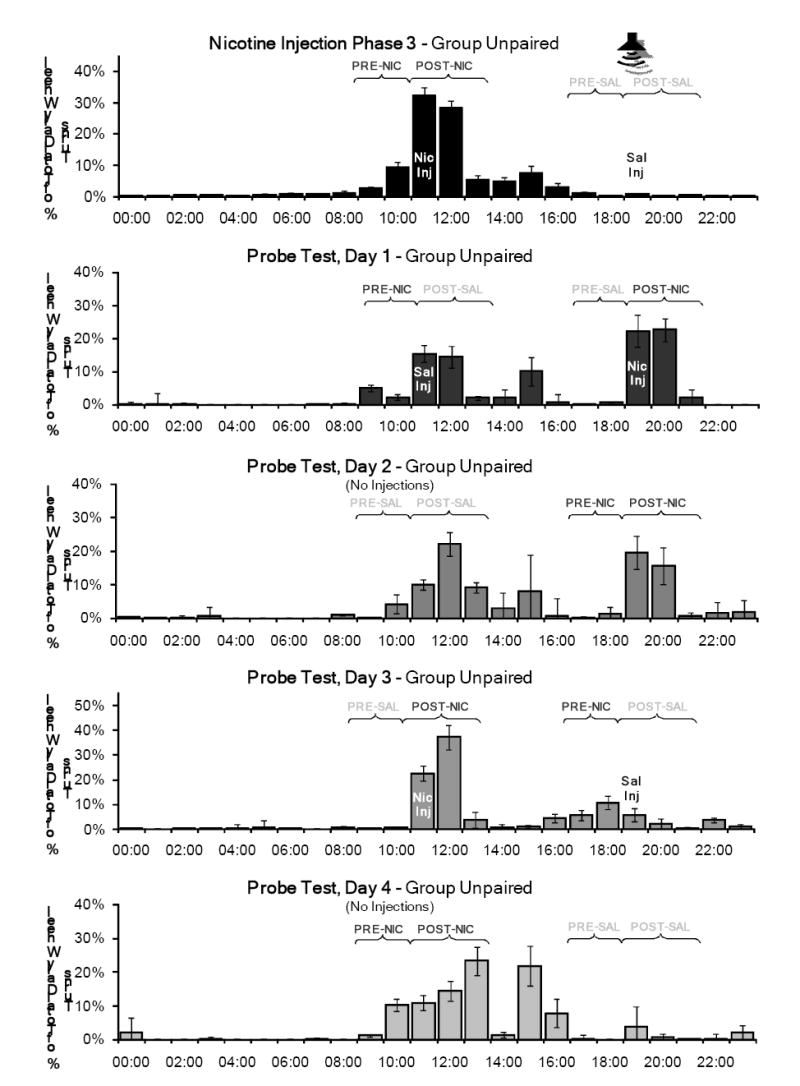

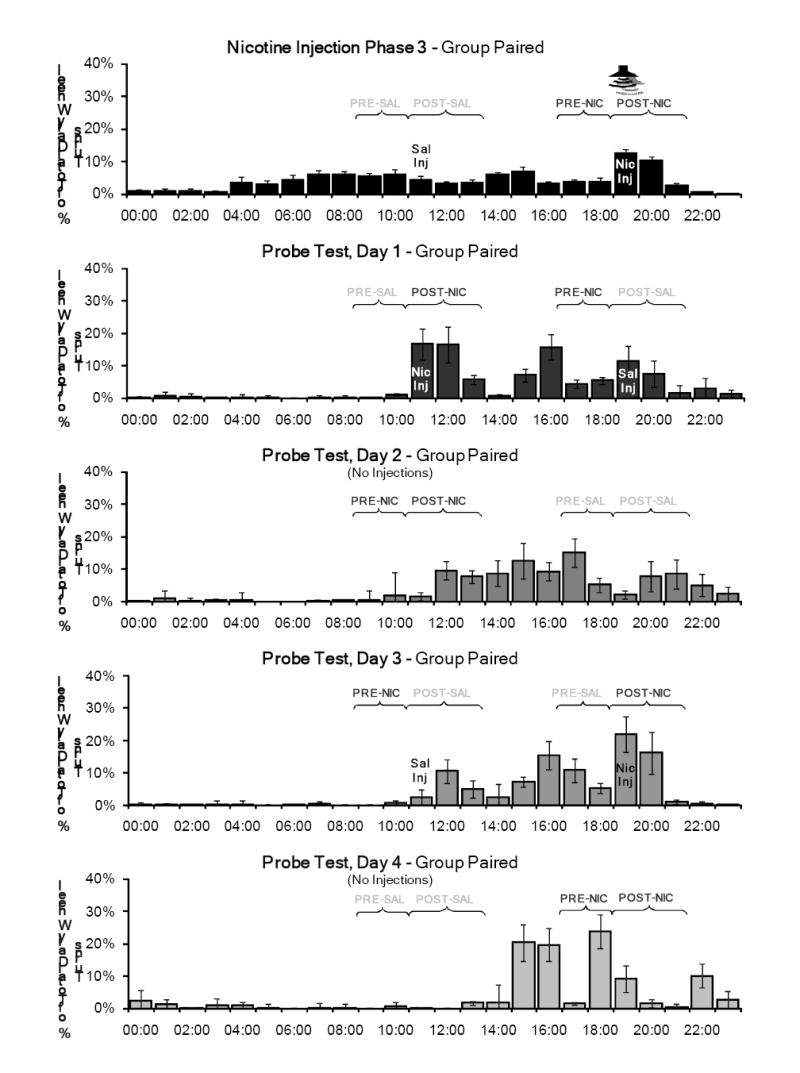

Figure 7 shows the percentage of total daily wheel running in the PRE and POST periods during the third nicotine injection phase and the Probe Test for Group Unpaired, and Figure 8 shows these data for Group Paired. For the PRE periods, a significant day-substance interaction was found (F(4, 25)=3.575, p=0.019), but this interaction was not significant for the POST periods (F(4, 25)=2.316, p=0.085).

Figure 7.

Mean percentage of total daily wheel running across the 7 days of the third nicotine injection phase and the Probe Test for Group Unpaired. The nicotine and saline injection times were switched on day 1, and returned to the normal times on day 3. No injections were administered on days 2 and 4, and the tone was not presented throughout this test. On days 2 and 4, the rats were handled briefly at 1500 to record body weights. Notable activity was observed in the PRE-and POST-nicotine periods at the normal time, which was consistent with the rest of the study.

Figure 8.

Mean percentage of total daily wheel running across the 7 days of the third nicotine injection phase and the Probe Test for Group Paired. The nicotine and saline injection times were switched on day 1, and returned to the normal times on day 3. No injections were administered on days 2 and 4, and the tone was not presented throughout this test. On days 2 and 4, the rats were handled briefly at 1500 to record body weights. Activity was consistently observed in the PRE-and POST-nicotine periods at the normal time. Significant activity in this PRE period was not observed in this group during the nicotine injection phases when the tone was paired with the nicotine injection.

On day 1, the nicotine and saline injection times were switched for all rats. Group Paired and Group Unpaired both showed a marked increase in wheel running activity in the new POST-nicotine period. A considerable amount of activity was also observed in the new POST-saline period, but was not as large as the amount of activity normally associated with this time of day. Both groups also showed increased activity in the PRE-nicotine period, which preceded the saline injection on this test day. The results of the planned comparisons showed that activity in all periods on this test day were not significantly different from activity during the previous injection phase (nicotine injection phase 3).

On day 2, when no injections were administered, little activity occurred in the PRE-saline and PRE-nicotine periods established on test day 1. However, considerable activity was observed in the novel saline and nicotine injection POST periods. The response to nicotine and saline in the PRE and POST periods differed significantly from the response to these substances in the previous injection phase, indicating that the pre-injection anticipation takes more than one day to reset to a new time. This was confirmed by planned comparisons (PRE (F(1,28)=6.170, p=0.019) and POST periods (F(1, 28)=4.506, p=0.043)).

On day 3, injections were administered again at the normal times, but without the paired tone. For both groups, activity was observed in the POST period for both nicotine and saline, but a larger amount of activity occurred after the nicotine injections. Some activity also occurred in the PRE period prior to the evening injections in both groups (the novel nicotine time for Group Unpaired, and the novel saline time for Group Paired). For the PRE period on this test day, compared to nicotine injection phase 3, planned comparisons showed a significant day-substance interaction (F(1, 28)=5.085, p=0.032) and day-group-substance interaction (F(1, 28)=5.287, p=0.029).

On day 4, when no injections were administered, Groups Paired and Unpaired showed little activity before or after the saline injection time, indicating again that saline does not entrain circadian activity. For both groups, significant activity was associated with the nicotine injection time in both the PRE and POST periods. Planned comparisons showed that activity in both POST periods on this test day were significantly different when compared to nicotine injection phase 3, illustrating that the circadian responses to the injections differed when the stimulus was not presented (day: F(1, 28)=23.011, p<0.001; day-group: F(1, 28)=5.030, p=0.033; day-substance: F(1, 28)=6.862, p=0.014). Activity in the PRE periods for both groups on this test day also differed significantly from the nicotine injection phase for the percentage of total daily wheel running (F(1, 28)=5.558, p=0.026) and for drinking (F(1, 28)=4.930, p=0.035).

Discussion

The third test phase examined the effects of the time of administration and the different substances without the tone. The nicotine and saline injection times were switched on day 1. No injections were administered on day 2. On day 3, both substances were administered at the original times, and no injections were administered on day 4.

In contrast to the previous study phases, Groups Paired and Unpaired here showed similar results throughout this test phase in the absence of the tone. When the injections were administered at novel times on day 1, both groups showed activity in each POST period and in the PRE period prior to the saline injection (administered at the normal nicotine injection time). Group Paired also increased activity three hours prior to the novel saline injection time, so the activity in this period may not have been directly related to the normal nicotine injection time.

When both injections were withheld on day 2, a considerable amount of activity was recorded during the POST periods for both the nicotine and saline injections. There was little activity recorded in the PRE periods for either injection. Since the saline injections did not entrain activity throughout the study, the activity in the POST-saline period is likely due to the circadian effects of the nicotine injections two days prior. It could also possibly be coupled with the conditioning of handling cues related to the injection procedure. The lack of pre-injection anticipation for the novel nicotine injection time suggests that it takes more than one drug administration to develop an obvious level of circadian anticipatory activity at a new time. However, given the large amount of activity observed in the POST-nicotine period, it follows that the post-injection activity rhythm needs only one administration to reset to a novel time.

Both groups showed similar responses when the two substances were administered again at the normal times on day 3. Small amounts of activity were recorded in the PRE-saline and POST-saline periods, and little activity was recorded in the PRE-nicotine period (which had previously been the novel saline injection time). As in the nicotine injection phases, the largest amount of activity was recorded in the POST-nicotine period.

On day 4, all injections were withheld again. Very little activity was recorded in the PRE-saline and POST-saline periods. Surprisingly, in both groups, a large amount of activity was recorded in both the PRE-nicotine and POST-nicotine periods. For Group Paired, this was the largest amount of pre-injection anticipatory activity observed throughout the study. The previous day (Test 3, day 3) was the only day in the study in which this group received a nicotine injection at the normal time without the paired tone. This accounts for the fact that on day 4 there was no statistically significant difference in activity between the two groups for the PRE-nicotine period. Until this point in the study, the two groups showed consistent differences in PRE-nicotine activity. The similarity in pre-nicotine activity levels shown here after a single unpredicted delivery of nicotine strongly supports our interpretation that the presence of the tone at the nicotine administration time interfered with the expression of pre-injection anticipatory activity.

General Discussion and Conclusions

In summary, these data indicate that the circadian locomotor activity pattern induced by a daily nicotine injection is actually divided into two parts based on two oscillator-like components: a pre-injection anticipatory activity bout and a post-injection evoked activity response, both of which persist on a circadian interval for at least 2 days when nicotine is withheld. The conditioned response to the tone is also coupled to the nicotine administration time, but the tone cannot reset the post-injection activity rhythm to a new time when presented without an injection.

Although it might seem simplest to hypothesize that the pre- and post-injection rhythms are controlled by the same circadian oscillator, the data from Group Paired (in which the injection is followed by a 20-minute tone) clearly argue that a separate oscillator controls each rhythm. In Group Paired, the post-injection evoked response appeared unchanged by the presence of the tone relative to the response shown by Group Unpaired. However, the pre-injection anticipatory bout was essentially eliminated by the reliable presence of the tone. The critical role of the tone in producing this pre-injection interference in Group Paired was confirmed in the Probe Test (Test 3, day 3) in which nicotine was administered in the absence of the tone at the normal nicotine injection time. On the following day, Group Paired showed a marked increase in pre-injection activity – a pre-injection activity level never previously shown by this group.

Although these data appear to demonstrate that nicotine injections entrain two (at least partly independent) circadian oscillator-circuits, it is not clear whether the circadian pre-injection anticipatory timing circuit and the circadian post-injection evoked circuit are separable from the two currently acknowledged circadian oscillators: the light entrainable oscillator (controlled by the suprachiasmatic nucleus)65,66, and the food entrainable oscillator (at least partly controlled by the dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus)52,67. Previous studies have shown that a conditioned cue can reset the light-entrainable oscillator68,69, although independent replication of this result has proven difficult70.

Because the anatomical location of the putative food-entrainable oscillator was only recently established52,67, the neurophysiological basis of the conditioning of drug entrained rhythms has not been explicitly related to food anticipation. However, it is worth noting that a study by de Groot and Rusak71 showed a suppressive effect of a conditioned stimulus on circadian food anticipatory activity, and effect that appears similar to the suppressive effect of the tone on nicotine anticipation we reported in this study. This similarity raises the possibility, but in no way confirms that the pre-nicotine activity rhythm is mediated by the food entrainable oscillator. Note that the circadian food entrainable timing circuitry was available in this study because our use of a rate-limited feeding schedule prevented sufficient food intake at one time to entrain the food-related circadian timing circuitry57.

Finally, it should be noted that repeated administrations of both higher and lower doses of nicotine than the one used in this study are known to produce sensitization and/or tolerance in a variety of physiological and behavioral responses, including locomotor activity72-77. Considering these data, it is very likely that sensitization and tolerance contributed to the circadian entrainment effects observed in the present study. However, despite considerable individual differences in total wheel running, the overall circadian entrainment patterns in this study were similar within each experimental group. Based on this consistency, we would expect similar entrainment patterns in experiments using other doses, sexes, and strains.

In particular, given typical assumptions about sensitization and tolerance, it would be expected that circadian anticipatory activity would be enhanced by the presence of a tone that predicts the effects of nicotine. Therefore, it is difficult to explain our finding that the presence of a tone paired with nicotine effects on one day suppressed circadian drug anticipatory activity on the following day. However, our data could be used to argue that sensitization and tolerance effects are also influenced by circadian timing cues, rather than controlled exclusively by environmental cues, as is commonly assumed.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIDA R01DA017692 to Ann Kosobud (PI) and William Timberlake (Co-PI). The authors would like to thank Joe Leffel, Scott Barton, George Rebec, Larime Wilson, Doug Toms, and Mike Bailey.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Robinson TE, Berridge KC. Addiction. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54:25–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deroche-Gamonet V, Belin D, Piazza PV. Evidence for addiction-like behavior in the rat. Science. 2004 Aug;305:1014–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1099020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vanderschuren LJ, Everitt BJ. Drug seeking becomes compulsive after prolonged cocaine self-administration. Science. 2004 Aug;305(5686):1017–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1098975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Badiani A, Camp DM, Robinson TE. Enduring enhancement of amphetamine sensitization by drug-associated environmental stimuli. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1997 Aug;282(2):787–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Everitt BJ, Dickinson A, Robbins TW. The neuropsychological basis of addictive behaviour. Brain Reseach Reviews. 2001 Oct;36(23):129–38. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00088-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hinson RE, Poulos CX. Sensitization to the behavioral effects of cocaine: modification by Pavlovian conditioning. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1981 Oct;15(4):559–62. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(81)90208-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lynch JJ, Fertziger AP, Teitelbaum HA, Cullen JW, Gantt WH. Pavlovian conditioning of drug reactions: some implications for problems of drug addiction. Conditional Reflex. 1973 Oct;8(4):211–23. doi: 10.1007/BF03000677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siegel S. Drug anticipation and drug addiction. The 1998 H. David Archibald Lecture. Addiction. 1999;94(8):1113–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94811132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siegel S, Ramos BM. Applying laboratory research: drug anticipation and the treatment of drug addiction. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2002 Aug;10(3):162–83. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.10.3.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramos BM, Siegel S, Bueno JL. Occasion setting and drug tolerance. Integrative Physiological and Behavioral Science. 2002 Jul;37(3):165–77. doi: 10.1007/BF02734179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siegel S, Allan LG. Learning and homeostasis: drug addiction and the McCollough effect. Psychological Bulletin. 1998;124(2):230–9. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.124.2.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morris RW. Circadian and circannual rhythms of emergency room drug-overdose admissions. Progress in Clinical and Biological Research. 1987;227B:451–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abarca C, Albrecht U, Spanagel R. Cocaine sensitization and reward are under the influence of circadian genes and rhythm. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002 Jun;99(13):9026–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142039099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spanagel R, Rosenwasser AM, Schumann G, Sarkar DK. Alcohol consumption and the body’s biological clock. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005 Aug;29(8):1550–7. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000175074.70807.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yuferov V, Butelman ER, Kreek MJ. Biological clock: biological clocks may modulate drug addiction. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2005 Oct;13(10):1101–3. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yuferov V, Bart G, Kreek MJ. Clock reset for alcoholism. Nature Medicine. 2005 Jan;11(1):23–4. doi: 10.1038/nm0105-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baird TJ, Briscoe RJ, Vallett M, Vanecek SA, Holloway FA, Gauvin DV. Phase-response curve for ethanol: Alterations in circadian rhythms of temperature and activity in rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1998 Nov;61(3):303–15. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(98)00111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baird TJ, Gauvin DV. Characterization of cocaine self-administration and pharmacokinetics as a function of time of day in the rat. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2000 Feb;65(2):289–99. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00207-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balogh B, Molnar E, Jakus R, Quante L, Olverman HJ, Kelly PAT, Kantor S, Bagdy G. Effects of a single dose of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine on circadian patterms, motor activity and sleep in drug-naive rats and rats previously exposed to MDMA. Psychopharmacology. 2004;173:296–309. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1787-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marchant EG, Mistlberger RE. Morphine phase-shifts circadian rhythms in mice: Role of behavioural activation. Neuroreport. 1995 Dec;7(1):209–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Groh KR, Ehret CF, Peraino C, Meinert JC, Readey MA. Circadian manifestations of barbiturate habituation, addiction and withdrawal in the rat. Chronobiol Int. 1988;5(2):153–66. doi: 10.3109/07420528809079556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kosobud AEK, Pecoraro NC, Rebec GV, Timberlake W. Circadian activity precedes daily methamphetamine injections in the rat. Neuroscience Letters. 1998 Jul;250(2):99–102. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00439-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pecoraro NC, Kosobud AEK, Rebec GV, Timberlake W. Long T methamphetamine schedules produce circadian ensuing drug activity in rats. Physiology & Behavior. 2000;71:95–106. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(00)00306-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White W, Feldon J, Heidbreder CA, White IM. Effects of administering cocaine at the same versus varying times of day on circadian activity patterns and sensitization in rats. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2000;114(5):972–82. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.114.5.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davidson AJ, Tataroglu O, Menaker M. Circadian effects of timed meals (and other rewards) Circadian Rhythms. 2005;393:509–23. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)93026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Honma K, Honma S, Hiroshige T. Activity rhythms in the circadian domain appear in suprachiasmatic nuclei lesioned rats given methamphetamine. Physiology & Behavior. 1987;40(6):767–74. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(87)90281-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moriya T, Fukushima T, Shimazoe T, Shibata S, Watanabe S. Chronic administration of methamphetamine does not affect the suprachiasmatic nucleus-operated circadian pacemaker in rats. Neuroscience Letters. 1996 Apr;208(2):129–32. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12565-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dougherty J, Miller D, Todd G, Kostenbauder HB. Reinforcing and other behavioral effects of nicotine. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 1981;5:487–95. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(81)90019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bevins RA, Palmatier MI. Extending the role of associative learning processes in nicotine addiction. Behav Cogn Neurosci Rev. 2004 Sep;3(3):143–58. doi: 10.1177/1534582304272005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caggiula AR, Donny EC, Chaudhri N, Perkins KA, Evans-Martin FF, Sved AF. Importance of nonpharmacological factors in nicotine self-administration. Physiol Behav. 2002 Dec;77(45):683–7. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00918-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caggiula AR, Donny EC, White AR, Chaudhri N, Booth S, Gharib MA, Hoffman A, Perkins KA, Sved AF. Environmental stimuli promote the acquisition of nicotine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002 Sep;163(2):230–7. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1156-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chaudhri N, Caggiula AR, Donny EC, Palmatier MI, Liu X, Sved AF. Complex interactions between nicotine and nonpharmacological stimuli reveal multiple roles for nicotine in reinforcement. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006 Mar;184(34):353–66. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0178-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dols M, Willems B, van den HM, Bittoun R. Smokers can learn to influence their urge to smoke. Addict Behav. 2000 Jan;25(1):103–8. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Le Foll B, Goldberg SR. Control of the reinforcing effects of nicotine by associated environmental stimuli in animals and humans. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2005 Jun;26(6):287–93. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le Sage MG, Burroughs D, Dufek M, Keyler DE, Pentel PR. Reinstatement of nicotine self-administration in rats by presentation of nicotine-paired stimuli, but not nicotine priming. Pharmacology, Biochemistry & Behavior. 2004;79:507–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ague C. Smoking patterns, nicotine intake at different times of day and changes in two cardiovascular variables while smoking cigarettes. Psychopharmacologia. 1973 May;30(2):135–44. doi: 10.1007/BF00421428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kita T, Nakashima T, Kurogochi Y. Circadian variation of nicotine-induced ambulatory activity in rats. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1986 May;41(1):55–60. doi: 10.1254/jjp.41.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gries JM, Benowitz N, Verotta D. Chronopharmacokinetics of nicotine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1996 Oct;60(4):385–95. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(96)90195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bellinger LL, Wellman PJ, Cepeda-Benito A, Kramer PR, Guan G, Tillberg CM, Gillaspie PR, Hill EG. Meal patterns in female rats during and after intermittent nicotine administration. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005 Mar;80(3):437–44. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blaha V, Yang ZJ, Meguid M, Chai JK, Zadak Z. Systemic nicotine administration suppresses food intake via reduced meal sizes in both male and female rats. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove) 1998;41(4):167–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gillin JC, Lardon M, Ruiz C, Golshan S, Salin-Pascual R. Dose-dependent effects of transdermal nicotine on early morning awakening and rapid eye movement sleep time in nonsmoking normal volunteers. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1994 Aug;14(4):264–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pelissier AL, Gantenbein M, Bruguerolle B. Nicotine-induced perturbations on heart rate, body temperature and locomotor activity daily rhythms in rats. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 1998 Aug;50(8):929–34. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1998.tb04010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacober A, Hasenfratz M, Battig K. Circadian and ultradian rhythms in heart rate and motor activity of smokers, abstinent smokers, and nonsmokers. Chronobiology International. 1994 Oct;11(5):320–31. doi: 10.3109/07420529409057248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adan A, Sanchez-Turet M. Smoking effects on diurnal variations of cardiovascular parameters. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 1995 Dec;20(3):189–98. doi: 10.1016/0167-8760(95)00037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parrott AC. Stress modulation over the day in cigarette smokers. Addiction. 1995 Feb;90(2):233–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.9022339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adan A, Sanchez-Turet M. Effects of smoking on diurnal variations of subjective activation and mood. Human Psychopharmacology. 2000 Jun;15(4):287–93. doi: 10.1002/1099-1077(200006)15:4<287::AID-HUP175>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adan A, Sanchez-Turet M. Influence of smoking and gender on diurnal variations of heart rate reactivity in humans. Neuroscience Letters. 2001 Jan;297(2):109–12. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01687-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adan A, Prat G, Sanchez-Turet M. Effects of nicotine dependence on diurnal variations of subjective activation and mood. Addiction. 2004;99:1599–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ague C. Nicotine and smoking: effects upon subjective changes in mood. Psychopharmacologia. 1973 Jun;30(4):323–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00429191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferguson SA, Kennaway DJ, Moyer RW. Nicotine phase shifts the 6-sulphatoxymelatonin rhythm and induces c-Fos in the SCN of rats. Brain Res Bull. 1999 Mar;48(5):527–38. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(99)00033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boulos Z, Rosenwasser AM, Terman M. Feeding schedules and the circadian organization of behavior in the rat. Behavioural Brain Research. 1980;1(1):39–65. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(80)90045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mieda M, Williams SC, Richardson JA, Tanaka K, Yanagisawa M. The dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus as a putative food-entrainable circadian pacemaker. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006 Aug;103(32):12150–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604189103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mistlberger RE. Circadian food-anticipatory activity-formal models and physiological mechanisms. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 1994;18(2):171–95. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(94)90023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stephan FK. Interaction between light-entrainable and feeding-entrainable circadian rhythms in the rat. Physiology & Behavior. 1986;38(1):127–33. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90142-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Strubbe JH, Woods SC. The timing of meals. Psychological Review. 2004;111(1):128–41. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.White W, Timberlake W. Two meals promote entrainment of rat food-anticipatory and rest-activity rhythms. Physiology & Behavior. 1995;57(6):1067–74. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(95)00023-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.White W, Schwartz GJ, Moran TH. Meal-synchronized CEA in rats: effects of meal size, intragastric feeding, and subdiaphragmatic vagotomy. Am J Physiol. 1999 May;276(5 Pt 2):R1276–R1288. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.5.R1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eastman C, Rechtschaffen A. Circadian temperature and wake rhythms of rats exposed to prolonged continuous illumination. Physiology & Behavior. 1983;31(4):417–27. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(83)90061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rosenwasser AM, Boulos Z, Terman M. Circadian organization of food intake and meal patterns in the rat. Physiology & Behavior. 1981;27(1):33–9. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(81)90296-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fitzroy Hardy D. The effect of constant light on the estrous cycle and behavior of the female rat. Physiology & Behavior. 1970;5:421–5. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(70)90246-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Peng MT, Jiang MJ, Hsu HK. Changes in running-wheel activity, eating and drinking and their day/night distributions throughout the life span of the rat. J Gerontol. 1980 May;35(3):339–47. doi: 10.1093/geronj/35.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schull J, Walker J, Fitzgerald K, Hiilivirta L, Ruckdeschel J, Schumacher D, Stanger D, McEachron DL. Effects of sex, thyro-parathyroidectomy, and light regime on levels and circadian rhythms of wheel-running in rats. Physiol Behav. 1989 Sep;46(3):341–6. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(89)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Le Foll B, Goldberg SR. Nictotine induces conditioned place preference over a large range of doses in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2005;178:481–92. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bevins RA, Eurek S, Besheer J. Timing of conditioned responding in a nicotine locomotor conditioning preparation: manipulations of the temporal arrangement between contextual cues and drug administration. Behavioural Brain Research. 2005;159:135–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boulos Z, Rosenwasser AM, Terman M. Feeding schedules and the circadian organization of behavior in the rat. Behavioural Brain Research. 1980;1(1):39–65. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(80)90045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Silver R, Schwartz WJ. The suprachiasmatic nucleus is a functionally heterogeneous timekeeping organ. Circadian Rhythms. 2005;393:451–65. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)93022-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gooley JJ, Schomer A, Saper CB. The dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus is critical for the expression of food-entrainable circadian rhythms. Nature Neuroscience. 2006 Mar;9(3):398–407. doi: 10.1038/nn1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Amir S, Stewart J. Resetting of the circadian clock by a conditioned stimulus. Nature. 1996 Feb;379(6565):542–5. doi: 10.1038/379542a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Amir S, Stewart J. Conditioning in the circadian system. Chronobiology International. 1998;15(5):447–56. doi: 10.3109/07420529808998701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.de Groot MHM, Rusak B. Responses of the circadian system of rats to conditioned and unconditioned stimuli. Journal of Biological Rhythms. 2000 Aug;15(4):277–91. doi: 10.1177/074873000129001369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.de Groot MH, Rusak B. Housing conditions influence the expression of food-anticipatory activity in mice. Physiol Behav. 2004 Dec;83(3):447–57. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Booze RM, Welch MA, Wood ML, Billings KA, Apple SR, Mactutus CF. Behavioral sensitization following repeated intravenous nicotine administration: Gender differences and gonadal hormones. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1999 Dec;64(4):827–39. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Collins AC, Romm E, Wehner JM. Nicotine tolerance: an analysis of the time course of its development and loss in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1988;96(1):7–14. doi: 10.1007/BF02431526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Domino EF. Nicotine induced behavioral locomotor sensitization. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2001 Jan;25(1):59–71. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(00)00148-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Faraday MM, O’Donoghue VA, Grunberg NE. Effects of nicotine and stress on locomotion in Sprague-Dawley and Long-Evans male and female rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2003 Jan;74(2):325–33. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00999-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gordon CJ, Rowsey PJ, Yang YL. Effect of repeated nicotine exposure on core temperature and motor activity in male and female rats. Journal of Thermal Biology. 2002 Dec;27(6):485–92. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Morgan MM, Ellison G. Different effects of chronic nicotine treatment regimens on body weight and tolerance in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1987;91(2):236–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00217070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]