Abstract

Background

Sepsis remains a substantial risk after surgery or other trauma. Macrophage dysfunction, as a component of immune suppression seen during trauma and sepsis, appears to be one of the contributing factors to morbidity and mortality. However, whereas it is known that the ability of macrophages to present antigen and express major histocompatibility complex MHC class II molecules is decreased during sepsis, it is not known to what extent this is associated with the loss of co-stimulatory receptor expression. Our objectives in this study were, therefore, to determine if the expression of co-stimulatory molecules, such as CD40, CD80, or CD86, on peritoneal/splenic/liver macrophages were altered by sepsis (cecal ligation [CL] and puncture [CLP] or necrotic tissue injury (CL) alone; and to establish the contribution of such changes to the response to septic challenge using mice that are deficient in these receptors.

Methods

To address our first objective, male C3H/HeN mice were subjected to CLP, CL, or sham (n = four to six mice/group), and the adherent macrophages were isolated from the peritoneum, spleen, or liver at 24 h post-insult. The macrophages were then analyzed by flow cytometry for their ex vivo expression of CD40, CD80, CD86, and/or MHC II.

Results

The expression of CD86 and MHC II, but not CD40 or CD80, were significantly decreased on peritoneal macrophages after the onset of sepsis or CL alone. In addition, CD40 expression was significantly increased in Kupffer cells after sepsis. Alternatively, splenic macrophages from septic or CL mice did not show changes in the expression of CD80, CD86, or CD40. To the degree that the loss of CD86 expression might contribute to the changes reported in macrophage function in septic mice, we subsequently examined the effects of CLP on CD86 -/- mice. Interestingly, we found that, unlike the background controls, neither the serum IL-10 concentrations nor the IL-10 release capacity of peritoneal macrophages from septic CD86 -/- mice were increased.

Conclusion

Together, these data suggest a potential role for the co-stimulatory receptor CD86/B7-2 beyond that of simply promoting competent antigen presentation to T-cells, but also as a regulator of the anti-inflammatory IL-10 response. Such a role may implicate the latter response in the development of sepsis-induced immune dysfunction.

Despite the best clinical care, optimal nutrition, and the application of numerous anti-inflammatory therapies (with the recent exceptions of activated protein C and low-dose steroid therapy), sepsis remains a substantial risk for trauma patients in the intensive care unit. Overall, sepsis is the tenth most common cause of death in the United States, and it has a mortality rate of about 29% [1,2]. Reasons for this high mortality rate include the complexity of the disease state, the incomplete understanding of the pathobiology characteristics of the syndrome, and the heterogeneous presentation of the infection, which leads to many cases being recognized late [2]. For these reasons, it is crucial that more research be done in the field.

With respect to the host response to infection, macrophages are important sentinels/coordinators of the innate and adaptive immune systems. Their functions include phagocytosis of bacteria, propagation of innate immunity through the presentation of foreign antigen to T cells (sometimes referred to as signal one), provision of co-stimulation (signal 2) to T cells, which augments adaptive immunity during antigen presentation, and release of appropriate pro- or anti-inflammatory cytokines. To be able to carry out these functions, macrophage membranes are outfitted with an array of receptors. Antigen is presented (signal one of antigen presentation) to T cells by MHC class II receptors. Co-stimulatory receptors that can present signal two, which are required during antigen presentation to T cells, include CD40, CD80 (B7-1), and CD86 (B7-2). Changes in the expression of these surface molecules can indicate either a deficiency in the capacity of the macrophage to present antigen to T cells or a protective response.

The surface receptors of the macrophage direct T cells to release cytokines. Therefore, up- or down-regulation of these macrophage receptors affects not only the individual macrophage but also the other cells of the immune system with which it comes in contact. It is crucial that T cells receive both signals from the macrophage when foreign antigen is presented; otherwise, T cell anergy or death will result.

Co-stimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 have similar but sometimes distinct functions. Early in the immune response, CD86 is expressed on cells in primary lymphoid tissue. On the other hand, CD80 is seen later, at the site of inflammation [3]. It is known that CD86 is expressed constitutively on antigen presenting cells and that it is upregulated quickly in response to infection; therefore it has been implicated in the early phases of the immune response [4,5]. In addition, CD86 is important for the Th2 response, and CD80 cannot compensate for the absence of CD86 in providing signal 2 in all cases [6,7]. Another important co-stimulatory receptor that is expressed on macrophages is CD40. Interactions between CD40 and CD40L, its ligand, result in a thymus-dependent humoral response, priming and expansion of CD4+ T cells, and activation of the signaling macrophage to upregulate co-stimulatory molecules and cytokine production [8].

Both CD80 and CD86 can interact with different receptors, resulting in opposite effects; binding to CD28 promotes T cell activation, whereas binding to cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4; CD152) down-regulates T cell function, a crucial step for turning off the immune response after an infection is cleared [9].

That said, with respect to experimental sepsis, studies indicate that the macrophage antigen presenting capacity appears to become dysfunctional by 24 h after sepsis is induced [10]. Some aspects of this peritoneal macrophage dysfunction are, however, apparent as early as 1-4 h after the onset of sepsis [10]. If the animal survives, the defect in peritoneal macrophage antigen presentation capability remains at sub-normal levels up to 14 days after the onset of sepsis [11]. Declines in macrophage capacity to release cytokines are also evident in these septic animals [12,13].

This decrease in responsiveness may be due partially to the decreased adenosine triphosphate (ATP) stores and increased intracellular Ca2+ found in splenocytes after sepsis [14]. A decrease in MHC class II expression (HLA-DR in humans) has been observed in septic patients within one day of the onset of severe sepsis. Interestingly, a correlation between HLA-DR expression and mortality has only been observed for those patients whose HLA-DR expression dips again after day seven of sepsis [15]. Gallinaro et al. found that MHC II expression is decreased on peritoneal macrophages after sepsis [11]. Nonetheless, our current knowledge of what contributes to this decrease in macrophage responsiveness and antigen presentation capability remains incomplete [16].

With the above information in mind, we hypothesized that a decrease in expression of macrophage co-receptors contributes to the dysfunction seen in the macrophage during late sepsis. Our objectives in this study are twofold. First, we sought to determine if the expression of co-stimulatory molecules such as CD40, CD80, or CD86 is deficient during sepsis. Second, we sought to define the impact of such a deficiency on the immune response of septic mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

For the majority of this study, we used male C3H/HeN mice between six and eight weeks old (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA). Age-matched CD86 knockout, C57BL/6-CD86tm1Shr (CD86 -/-) or background control C57BL/6 mice (+/+) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). These animals were cared for in accordance with the Animal Welfare Act and National Institutes of Health guidelines, and the project was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Rhode Island Hospital, Providence, RI.

The sepsis model

Cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) was performed to model sepsis in the mouse, as described previously [17]. This model produces a source of necrotic tissue injury in the peritoneum, and releases gram-negative and -positive bacteria and other microbes.

Following isoflurane anesthesia, an incision was made through the skin and abdominal muscles. The cecum was exteriorized, the lateral third was ligated, and the cecum was punctured twice using a 22-gauge needle. Following an expression of a small amount of fecal material, the cecum was returned to the body cavity, the incision was closed, and ∼0.6 mL of Ringer’s solution was given subcutaneously on the dorsal side to facilitate resuscitation.

Collection of samples

Animals were sacrificed 24 h after CLP or sham operations by methoxyflurane overdose, as we have previously shown this to be within a period of marked immune suppression, but prior to substantial mortality [12,18]. Peritoneal macrophages were harvested [19] via lavage of the peritoneal cavity with 2 × 5 mL of cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The cells were centrifuged (800 × g at 4°C for 15 min) and washed in fresh PBS.

Splenic macrophages were obtained as described previously [20]. The spleens were removed and gently glass-ground, and erythrocytes were lysed using hypotonic buffers; isolated splenocytes were then washed, counted, and plated at 1 × 107 cells/mL in plastic tissue culture plates, and incubated at 37°C for 2 h. The adherent splenic macrophages were then washed with PBS.

Kupffer cells were harvested as described previously [21]. In brief, the liver was antero-grade perfused with 25 mL of ice-cold Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS, Gibco, Grand Island, NY) through the portal vein and immediately followed by perfusion with 10 mL of pre-warmed 0.05% collagenase IV (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in HBSS. The liver was then removed, minced finely in a Petri dish containing 5 mL of warm collagenase and incubated at 37°C for 20 min. The cell suspension was passed through a steel screen, centrifuged, resuspended in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle medium (DMEM, Sigma), layered onto 16% Metrizamide (Accurate Chemical, Westbury, NJ) in HBSS, and centrifuged at 3,000 × g, 4°C for 45 min. The cells from the interface were collected and resuspended in PBS.

Blood was collected in a syringe containing 2 units of heparin then transferred to a microtube, and centrifuged immediately at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Plasma samples were stored at -70°C until analyzed.

Staining for flow cytometry

Cell staining was performed as described previously [31]. Cells (1 × 106) were washed in PBS, resuspended in 0.1 mL of Fc-blocker (1 μg/100 μL) (2.4 GZ, BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) for 15 min on ice and then incubated with appropriate antibodies (anti-CD40, anti-CD80, anti-CD86, or anti-I-A/I-E [MHC II] in combination with anti-F4/80, a macrophage marker, from BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) for another 45 min on ice in the dark. The cells were washed, fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS, read on a BD FACSort (BD Biosciences) for two-color flow cytometry, and the results were analyzed by a PC-lysis software (BD Biosciences).

Cell culture and ELISA

Non-adherent splenocytes were cultured at a density of 1 × 106cells/mL in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) media containing 10% fetal bovine serum, stimulated on anti-CD3e-coated plastic tissue culture dishes (15 μg/mL; NA/LE, BD Biosciences) for 48 h at 37°C. The supernatant was collected and stored at -70°C until analyzed. Adherent macrophage monolayers were stimulated with 10 μg/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (E. coli serotype 055:B5; Sigma) of DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum for 24 h (37°C, 5% CO2). At the end of the incubation period, the cultured supernatants were collected for analysis. Concentrations of IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, and IL-10 in the plasma samples or in the splenocytes cultured supernatants were measured by ELISA as described previously [22].

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean values ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Cytokine concentrations were compared by t-test or one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Differences were considered significant if p < 0.05. There were samples from four to six separate animals in each group.

RESULTS

Differential expression of co-stimulatory receptors or MHC II in macrophages after CL or sepsis (CLP)

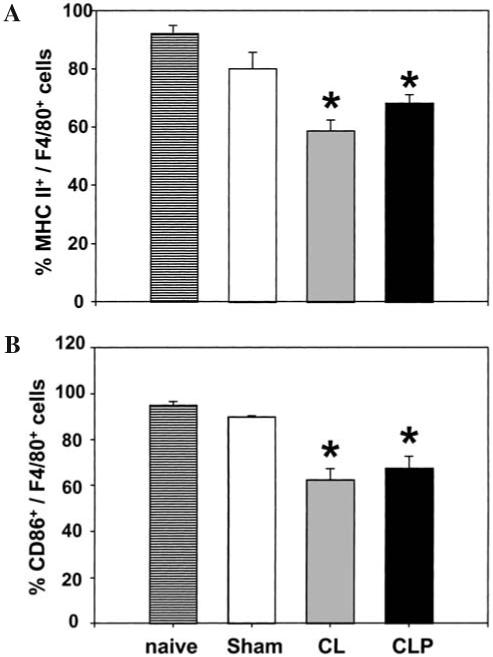

Peritoneal macrophages isolated 24 h after CL or CLP showed a significant decrease in expression of CD86 and MHC II (Fig. 1). Alternatively, a non-significant increase in expression of CD40 and CD80 was seen (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Expression of MHC II and CD86 on peritoneal macrophages 24 h post-CLP or CL. Peritoneal macrophages were isolated from C3H/HeN mice 24 h after surgery (CL, CLP or Sham-CLP [Sham]). For co-stimulatory molecule expression, peritoneal macrophages were stained with MHC II (A) and CD86 (B) with F4/80 Abs. The results are presented as percentage positively stained with Abs. *Significant difference at p < 0.05 versus sham, ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, mean ± SEM; n = four to six animals/group.

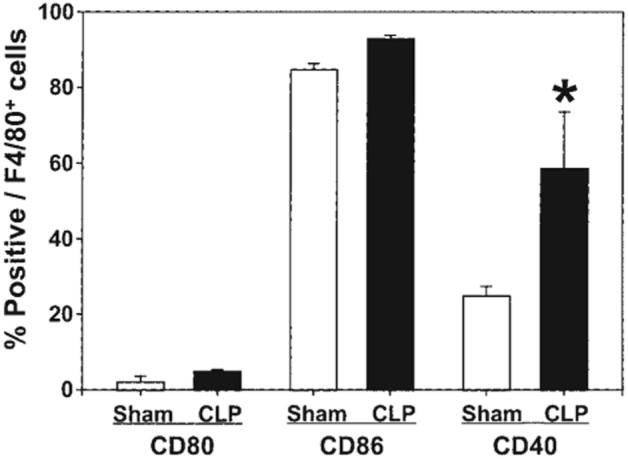

Whereas we have reported previously the decreased function of mouse Kupffer cell MHC II following shock [21], we found here that Kupffer cells isolated 24 h after sepsis were increased in expression of CD40, but no such change in CD80 or CD86 expression was observed (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Expression of CD80, CD86 and CD40 on Kupffer cells 24 h post-CLP. Liver macrophage (Kupffer cells, F4/80+ cells) were isolated from C3H/HeN mice 24 h after surgery (CLP or Sham-CLP [Sham]). For co-stimulatory molecule expression, Kupffer cells were stained with CD80, CD86, or CD40 with F4/80 Abs. The results are presented as percentage positively stained with Abs. *Significant difference at p < 0.05 versus sham, ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, mean ± SEM; n = four to six animals/group.

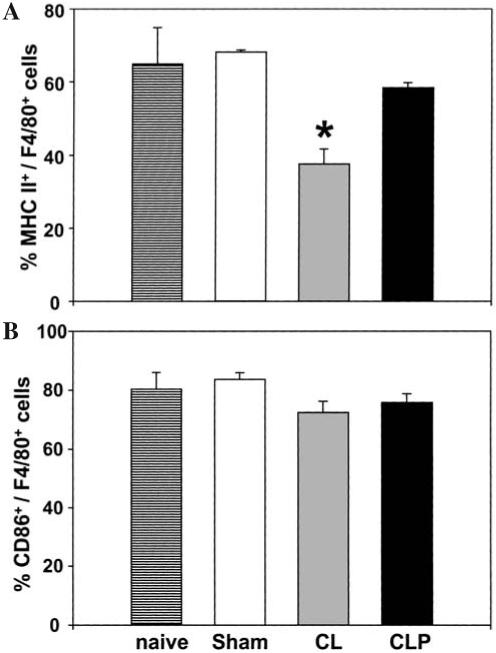

Macrophages isolated from the spleen 24 h after sepsis showed no change in percent of cells expressing CD40, CD80, CD86, or MHC II. Interestingly, a reduction in expression of MHC II was observed in splenic macrophages from CL animals (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Expression of MHC II and CD86 on splenic macrophages 24 h post-CLP or CL. Splenic macrophages (F4/80+ cells) were isolated from C3H/HeN mice 24 h after surgery (CL, CLP or Sham-CLP [Sham]). For co-stimulatory molecule expression, splenocytes were stained with MHC II (A) and CD86 (B) with F4/80 Abs. The results are presented as percentage positively stained with Abs. *Significant difference at p < 0.05 versus sham, ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, mean ± SEM; n = four to six animals/group.

Effect of deficiency of CD86 gene expression on cytokine concentrations release

Since the data above implied that splenic adherent cells, Kupffer cells, and peritoneal macrophage CD86 were differentially affected by CLP, we carried out studies to examine the role of this gene in the cytokine response of the septic mouse. Both CD86 -/- and wild-type mice were subjected to CLP or sham operations. Splenocyte or peritoneal macrophage cultured supernatants and plasma samples were collected for cytokine measurement. The results are displayed in Figures 4-6.

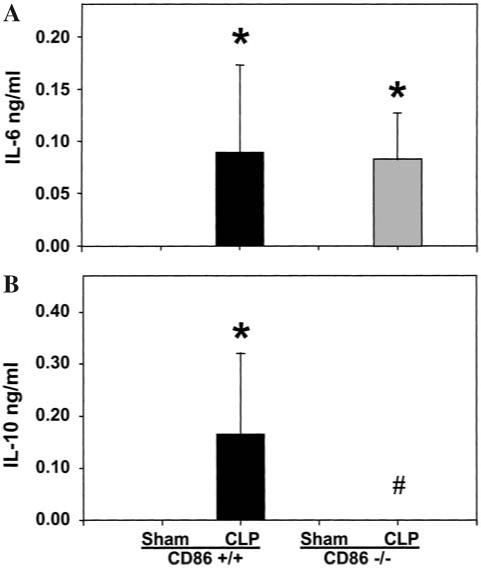

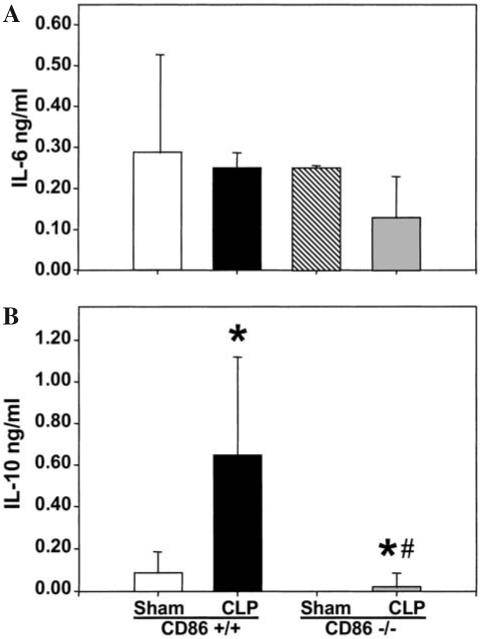

FIG. 4.

IL-6 and IL-10 levels in plasma of CD86 +/+ (background control) or CD86 -/- mice 24 h post-CLP. Plasma was collected from each animal 24 h after surgery. IL-6 (A) or IL-10 (B) levels were measured by ELISA. n = 4 animals/group. Significance indicated by *p < 0.05 versus sham, #p < 0.05 versus CD86 +/+ CLP, ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

FIG. 6.

Levels of IL-6 (A) and IL-10 (B) in conditioned medium of cultured peritoneal macrophages, isolated 24 h post CLP or Sham-CLP [Sham] from CD86 +/+ and CD86 -/- mice, stimulated for 24 h with LPS. Triplets of equal number (106) of cells/mL were cultured for 24 h (37°C, 5% CO2). The supernatants were collected and IL-2 measurement was made by ELISA. n = 4 independent repeat experiments. Significance indicated by *p < 0.05 versus sham, #p < 0.05 versus CD86 +/+ CLP, ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

As expected from prior studies [18], neither IL-2, IL-4, nor IFN-γ was observed in the blood of septic mice at 24 h. Although not detectable in the sham animals, IL-6 was found in the plasma of both the wild-type and knockout mice at very similar levels (Fig. 4). Alternatively, as IL-10 was observed to be significantly increased in the plasma of the wild-type CLP compared to sham animals, it was not detectable in the septic knockout animals’ blood.

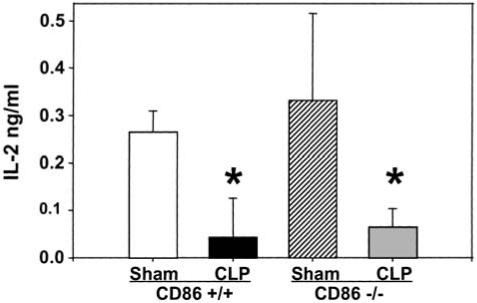

The level of IL-2 release by splenocytes in response to anti-CD3 stimulation was markedly decreased after CLP in wild-type animals. However, this was not affected by the lack of CD86, as no difference was seen in IL-2 release following the induction of sepsis in the CD86 -/- mice (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Levels of IL-2 in conditioned medium of cultured splenocyte isolated 24 h post CLP or Sham-CLP [Sham] from CD86 +/+ and CD86 -/- mice, stimulated for 24 h with plate-bound anti-CD3. Triplets of equal number (106) of cells/mL were cultured for 24 h (37°C, 5% CO2). The supernatants were collected and IL-2 measurement was made by ELISA. n = 4 independent repeat experiments. *Significant difference at p < 0.05 versus sham, ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

In LPS-stimulated peritoneal macrophages, IL-6 release capacity was typically lower in cells obtained from CLP than sham mice, irrespective of whether or not they were derived from CD86 -/- or wild-type mice (Fig. 6). Alternatively, IL-10 release was observed to increase in cells obtained from wild-type CLP animals; however, no such potentiation was seen in the CD86 -/- mouse cells (Fig. 6).

DISCUSSION

The objective in this study was to investigate the role of macrophage co-stimulatory receptor expression in the immune suppression seen after CLP. Our results confirm prior studies that a decrease in peritoneal macrophage MHC II expression was observed after sepsis [11]. With respect to peritoneal and splenic MHC II expression, we also found that tissue injury, in the form of CL, was sufficient to induce a decrease in MHC II expression. This is in keeping with prior findings indicating that Th1 cytokine release in the spleen and peritoneum can be suppressed by tissue injury alone [22]. However, we also show that CD86 expression is decreased on peritoneal macrophages after sepsis, while CD40 and CD80 expression is unaltered. Interestingly, none of these co-receptors showed a decline in expression on splenic macrophages or Kupffer cells following the onset of sepsis. In this respect, as the loss of MHC II expression has already been examined extensively [16,23-25], we chose to investigate further the contribution of changing CD86 expression to the development of immune dysfunction seen in septic mice. To address this, we chose to examine the effect of CD86 gene deficiency on septic mice response. However, because of the lack of change seen in both Kupffer cells and splenic macrophages co-stimulatory molecule expression, we focused primarily on the peritoneal macrophage population (which was altered here), as well as changes in plasma and splenic lymphoid responses. The results indicate that CD86 -/- mice express similar levels of IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, and IFN-γ to their wild-type (CD86 +/+) counterparts, but they differ most dramatically in IL-10 production.

The finding that IL-10 expression is essentially lost in the knockout mice is intriguing. On its face, it suggests that these rodents should exhibit an overzealous pro-inflammatory response to infectious challenge [26-29]; however, this was not observed in our septic mice (evidenced by no change in the circulating IL-6 levels in CD86 -/- vs. CD86 +/+). That said, it could be suggested that since IL-6 has both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory effects, this agent might not be the ideal index of inflammatory changes [30,31]. We chose IL-6 as a surrogate for inflammation for two reasons. First, whereas classic pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF and IL-1β, are readily detected in this model during the initial period (0-6 h) post-CLP, they are typically difficult to detect at 24 h post-CLP (a time point of marked immune suppression [18], which we are examining here). Second, whereas IL-6 has pleiotropic effects, it is still the most consistently upregulated cytokine seen in animals or critically ill patients with systemic inflammation [32]. Similarly, we and others [28,33,34] have suggested that the augmented IL-10 release encountered in traumatized, shocked, or septic mice contributes to the development of immune suppression, that is, reduced Th1 responsiveness. Here again, the CD86 -/- exhibited no improvement in their splenocyte capacity to release IL-2 following CLP when compared to CD86 +/+. We speculate that other anti-inflammatory stimuli (soluble, e.g., increased TGF-β, PGE2; or membrane-bound, e.g., altered CD152, KLRG-1) may be more meaningful surrogates for IL-10 as an immune suppressant. Thus, the significance of this change in IL-10 production/expression remains to be elucidated.

The decline in IL-10 release/expression also suggests a direct/indirect effect of CD86 expression on signaling for the release of IL-10. Several studies have indicated a link between lack of CD86 signaling and a decrease of IL-10 production. Ullrich et al. showed that anti-CD86 blocked secretion of IL-10 [35]. Furthermore, Woodward et al. showed that anti-CD86 suppressed IL-10 mRNA expression [36].

IL-10 is known to inhibit macrophage activation and proliferation [28,37]. This effect is direct and is not the result of increased apoptosis [37]. Because of its immunosuppressive properties, the downregulation of IL-10 could be seen as protective to the survival of the septic animal. On the other hand, IL-10 has been shown to be necessary for survival in response to endotoxic shock or acute lethal septic shock. For example, a study of critically ill patients showed that increased mortality from sepsis was associated with lower IL-10 release in response to stimulus [38].

Overall, IL-10 has a multifaceted role in sepsis. Although it causes suppression of the immune system, it also appears to be necessary for survival of septic insult. The complex role of IL-10 in sepsis was further discussed by Oberholzer et al. [39]. They retrospectively examined prior research, which had measured IL-10 concentrations in the blood of septic patients, and they observed that higher IL-10 concentrations in the blood were associated with increased severity of illness. They also found that existing IL-10 allows tolerance to higher levels of LPS exposure. They summarized a study by Walley et al. [40] in which pretreatment with IL-10 improved outcome after CLP, but treatment with anti-IL-10 worsened outcome. Nevertheless, previous studies from our laboratory demonstrated that treatment of septic mice with anti-IL-10 at 12 h, but not 0 h, after the onset of sepsis improves survival [28].

Constitutively expressed on antigen presenting cells, CD86 is upregulated quickly in response to infection, and has therefore been implicated in the early phases of the immune response [4,6]. It has also been shown that CD86 is important for the Th2 response, and that CD80 cannot compensate in providing signal 2 in all cases [6,7]. This latter observation supports a role for the loss of CD86 in the direct/indirect induction of IL-10 seen here with CLP in the CD86 -/- mice. Although we are not able to link CD86 deficiency with decreased antigen presentation capabilities, upregulation of CD86 in macrophages increases ability to present antigen [41]. Most importantly, a clinical study of septic critically ill patients associated decreased CD86 with HLA-DR expression [42]. Furthermore, these changes (while not linked causally) were associated with a marked decline in the capacity of blood monocytes from septic patients to present recall antigen and the potentiation of IL-10 release.

Together, these data suggest a potential role for the co-stimulatory receptor CD86/B7-2 beyond that of simply promoting competent antigen presentation to T-cells, but also as a regulator of the anti-inflammatory IL-10 response. Such a role may implicate this latter response in the development of sepsis-induced immune dysfunction.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Sara Spangenberger at Rhode Island Hospital Core Research Laboratories for her help in acquiring flow cytometry data. This study was supported by a grant from NIH R01-GM46354 (to A.A.).

Footnotes

Presented at the 24th Annual Meeting of the Surgical Infection Society, Indianapolis, IN, April 29-May 1, 2004.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, et al. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: Analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1303–1310. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vincent J, Abraham E, Annane D, et al. Reducing mortality in sepsis: New directions. The Critical Care Forum. 2003:6. doi: 10.1186/cc1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salomon B, Bluestone JA. Complexities of CD28/B7: CTLA-4 costimulatory pathways in autoimmunity and transplantation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:225–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furukawa Y, Mandelbrot DA, Libby P, et al. Association of B7-1 co-stimulation with the development of graft arterial disease. Studies using mice lacking B7-1, B7-2, or B7-1/B7-2. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:473–484. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64559-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lanier LL, O’Fallon S, Somoza C, et al. CD80 (B7-1) and CD86 (B7-2) provide similar costimulatory signals for T cell proliferation, cytokine production, and generation of CTL. J Immunol. 1995;154:97–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mbow ML, DeKrey GK, Titus RG. Leishmania major induces differential expression of costimulatory molecules on mouse epidermal cells. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:1400–1409. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200105)31:5<1400::aid-immu1400>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown JA, Greenwald RJ, Scott S, et al. T helper differentiation in resistant and susceptible B7-deficient mice infected with Leishmania major. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:1764–1772. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200206)32:6<1764::AID-IMMU1764>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grewal IS, Flavell RA. CD40 and CD154 in cell-mediated immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:111–135. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee KP, Harlan DM, June CH. Role of co-stimulation in the host response to infection. In: Gallin JI, Snyderman R, editors. Inflammation; Basic principles and clinical correlates. Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins; Philadelphia: 1999. pp. 191–206. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ayala A, Urbanich MA, Herdon CD, Chaudry IH. Is sepsis-induced apoptosis associated with macrophage dysfunction? J Trauma. 1996;40:568–574. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199604000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gallinaro R, Naziri W, McMasters K, et al. Alteration of mononuclear cell immune-associated antigen expression, interleukin-1 expression, and antigen presentation during intra-abdominal infection. Shock. 1994;1:130–134. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199402000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ayala A, Perrin MM, Kisala JM, et al. Polymicrobial sepsis selectively activates peritoneal but not alveolar macrophage to release inflammatory mediators (IL-1, IL-6 and TNF) Circ Shock. 1992;36:191–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ayala A, Chaudry IH. Immune dysfunction in murine polymicrobial sepsis: Mediators, macrophages, lymphocytes and apoptosis. Shock. 1996;6:S27–S38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ayala A, Chung CS, Song GY. Lymphocyte activation, anergy, and apoptosis in polymicrobial sepsis. In: Marshall JC, Cohen J, editors. Immune response in the critically ill. Springer; Berlin: 1999. pp. 227–245. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tschaikowsky K, Hedwig-Geissing M, Schiele A, et al. Coincidence of pro- and anti-inflammatory responses in the early phase of severe sepsis: Longitudinal study of mononuclear histocompatibility leukocyte antigen-DR expression, procalcitonin, C-reactive protein, and changes in T-cell subsets in septic and postoperative patients. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:1015–1023. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200205000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ayala A, Ertel W, Chaudry IH. Trauma-induced suppression of antigen presentation and expression of major histocompatibility class II antigen complex. Shock. 1996;5:79–90. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199602000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang P, Chaudry IH. A single hit model of polymicrobial sepsis: Cecal ligation and puncture. Sepsis. 1998;2:227–233. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ayala A, Deol ZK, Lehman DL, et al. Polymicrobial sepsis but not low-dose endotoxin infusion causes decreased splenocyte IL-2/IFN-gamma release while increasing IL-4/IL-10 production. J Surg Res. 1994;56:579–585. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1994.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ayala A, Perrin MM, Chaudry IH. Defective macrophage antigen presentation following haemorrhage is associated with the loss of MHC class II (Ia) antigens. Immunology. 1990;70:33–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ayala A, Perrin MM, Wang P, et al. Hemorrhage induces enhanced Kupffer cell cytotoxicity while decreasing peritoneal or splenic macrophage capacity: Involvement of cell-associated TNF and reactive nitrogen. J Immunol. 1991;147:4147–4154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ayala A, Perrin MM, Ertel W, Chaudry IH. Differential effects of haemorrhage on Kupffer cells: Decreased antigen presentation despite increased inflammatory cytokine (IL-1, IL-6 and TNF) release. Cytokine. 1992;4:66–75. doi: 10.1016/1043-4666(92)90039-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ayala A, Song GY, Chung CS, et al. Immune depression in polymicrobial sepsis: The role of necrotic (injured) tissue and endotoxin. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:2949–2955. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200008000-00044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baker CC, Niven-Fairchild AT, Yamada A, et al. Macrophage antigen presentation and interleukin-1 production after cecal ligation and puncture in C3H/HeN and C3H/HeJ mice. Arch Surg. 1991;126:253–258. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1991.01410260143021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kupper TS, Green DR, Durum SK, Baker CC. Defective antigen presentation to a cloned T-helper cell by macrophages from burned mice can be restored with interleukin-1. Surgery. 1985;98:199–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity: Enhancing the efficiency of antigen presentation. Mt Sinai J Med. 2001;68:106–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Standiford TJ, Strieter RM, Lukacs NW, Kunkel SL. Neutralization of IL-10 increases lethality in endotoxemia. J Immunol. 1995;155:2222–2229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tong L, Pav S, White DM, et al. A highly specific inhibitor of human p38 MAP kinase binds in the ATP pocket. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:311–318. doi: 10.1038/nsb0497-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song GY, Chung CS, Chaudry IH, Ayala A. What is IL-10′s role in polymicrobial sepsis: Anti-inflammatory agent or immune suppressant? Surgery. 1999;126:378–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mayumi T, Hayashi S, Takezawa J. Adenoviral-mediated overexpression of IL-10 improves survival of sepsis. Shock. 1999;11(Suppl):24–30. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ayala A, Knotts JB, Ertel W, et al. Role of interleukin-6 and transforming growth factor-beta in the induction of depressed splenocyte responses following sepsis. Arch Surg. 1993;128:89–95. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420130101015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steensberg A, Fischer CP, Keller C, et al. IL-6 enhances plasma IL-1ra, IL-10, and cortisol in humans. Am J Physiol. 2003;285:E433–E437. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00074.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Remick DG, Bolgos GR, Siddiqui J. Six at six: Interleukin-6 measured 6 hours after the initiation of sepsis predicts mortality over 3 days. Shock. 2002;17:463–467. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200206000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steinhauser ML, Hogaboam CM, Kunkel SL. IL-10 is a major mediator of sepsis-induced impairment in lung antibacterial host defense. J Immunol. 1999;162:392–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hasko G, Virag L, Egnaczyk G, et al. The crucial role of IL-10 in the suppression of the immunological response in mice exposed to staphylococcal enterotoxin B. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:1417–1425. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199804)28:04<1417::AID-IMMU1417>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ullrich SE, Pride MW, Moodycliffe AM. Antibodies to the costimulatory molecule CD86 interfere with ultraviolet radiation-induced immune suppression. Immunology. 1998;94:417–423. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00530.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woodward JE, Bayer AL, Chavin KD, et al. T-cell alterations in cardiac allograft recipients after B7 (CD80 and CD86) blockade. Transplantation. 1998;66:14–20. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199807150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Farrell AM, Liu Y, Moore KW, Mui AL. IL-10 inhibits macrophage activation and proliferation by distinct signaling mechanisms: Evidence for Stat3-dependent and -independent pathways. EMBO J. 1998;17:1006–1018. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.4.1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lowe PR, Galley HF, Abdel-Fattah A. Influence of interleukin-10 polymorphisms on interleukin-10 expression and survival in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:34–38. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200301000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oberholzer A, Oberholzer C, Moldawer LL. Interleukin-10: A complex role in the pathogenesis of sepsis syndromes and its potential as an anti-inflammatory drug. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:S58–S63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walley KR, Lukacs NW, Standiford TJ, et al. Balalnce of inflammatory cytokines related to severity and mortality of murine sepsis. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4733–4738. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4733-4738.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fischer HG, Dorfler R, Schade B, Hadding U. Differential CD86/B7-2 expression and cytokine secretion induced by Toxoplasma gondii in macrophages from resistant or susceptible BALB H-2 congenic mice. Int Immunol. 1999;11:341–349. doi: 10.1093/intimm/11.3.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manjuck J, Saha DC, Astiz M, et al. Decreased response to recall antigens is associated with depressed costimulatory receptor in septic critically ill patients. J Lab Clin Med. 2000;135:153–160. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2000.104306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]